Latest CRS Report Edition—“China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities”—Projections to 2030 from Office of Naval Intelligence

Ronald O’Rourke, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, RL33153 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 21 May 2020).

Having trouble accessing the website above? Please download a cached copy here!

You can also click here to access the report via the new public CRS website.

In addition to his continuous incremental improvements, Ronald O’Rourke has revised this latest edition of his report on Chinese naval modernization to incorporate new projections and related assessments from the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) that ONI provided to the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC), and SASC provided to the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

The changes include a new table of note (Table 2), and a dozen instances in the text where ONI’s narrative points were incorporated. Given the authoritative analysis supporting these revelations, and the rarity with which they are made publicly available in this manner, they are all worth reading carefully in full!

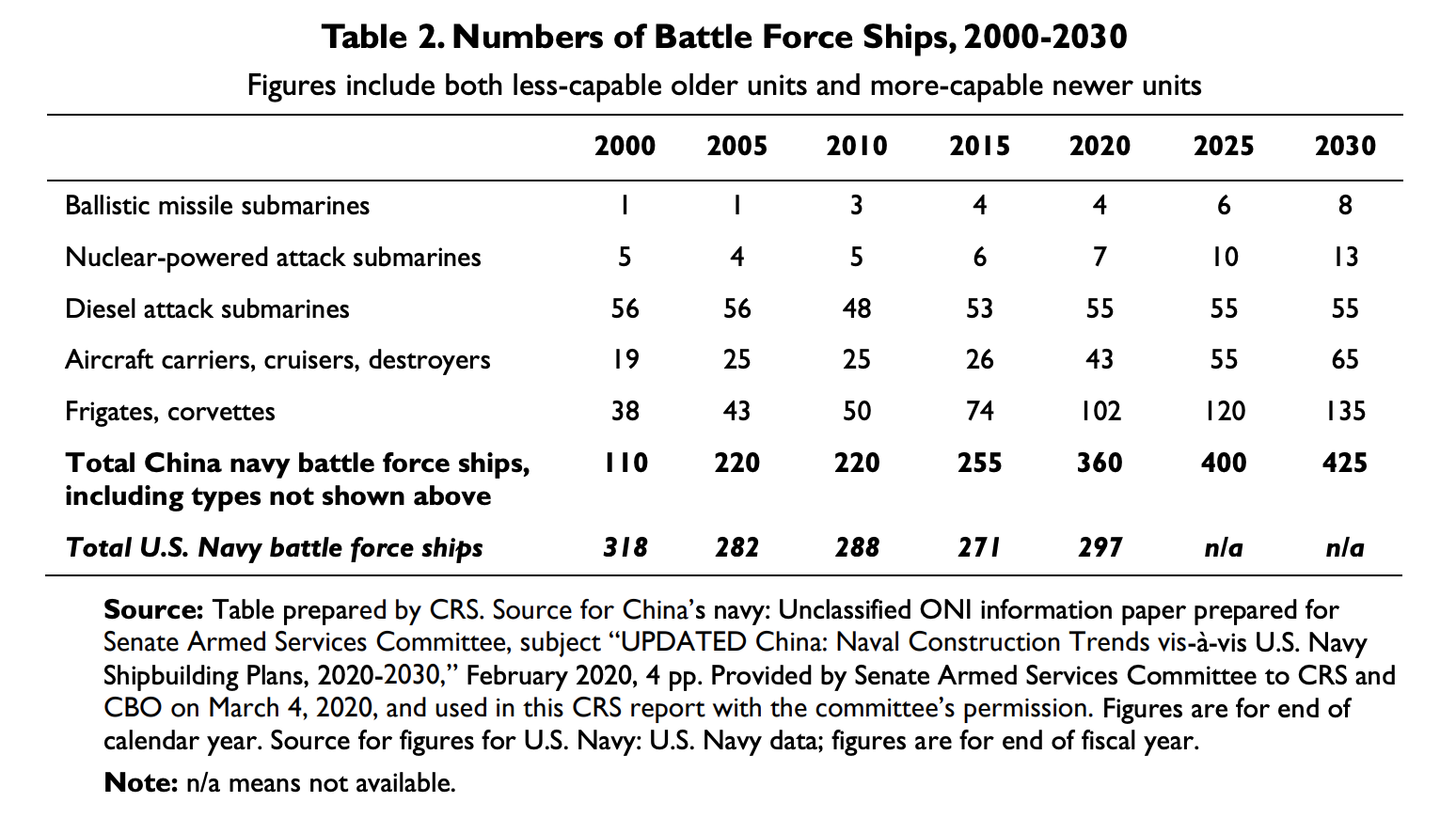

Table 2 (p. 26) has shows ONI estimates/projections regarding numbers of China Navy Battle Force Ships—both by ship type and in aggregate—for 2020, 2025, and 2030, respectively:

SSBN: 4↗6↗8

SSN: 7↗10↗13

SSK: 55→55→55

CV, CG, DDG: 43↗55↗65

FFG, FFL, DDC: 102↗120↗135

TOTAL: 360↗400↗425

Here’s what this all means: China already has its own 355+ ship navy, and within a decade will exceed that benchmark by 70 ships! At the end of 2020, ONI assesses, China will have 360 battle force ships vs. the U.S. Navy’s 297–over 60 more. In 2025, ONI projects, China’s Navy will have 400 ships. In 2030, ONI projects, China’s Navy will have 425 ships. Even if the U.S. Navy reaches its current goal of 355+ by then, China’s Navy could still have 70 more ships. Given the U.S. Navy’s dispersed global responsibilities vs. China’s concentrated focus on being able to fight and win a regional war over disputed sovereignty claims, potentially against the U.S. and one or more of its allies/partners, a sufficiently-sized U.S. Navy is required to preserve American security and vital interests.

***

New Text Reflecting Latest Assessments and Projections from the Office of Naval Intelligence

p. 2

China’s navy is, by far, the largest of any country in East Asia, and within the past few years it has surpassed the U.S. Navy in numbers of battle force ships, meaning the types of ships that count toward the quoted size of the U.S. Navy. ONI states that at the end of 2020, China’s will have 360 battle force ships, compared with a projected total of 297 for the U.S. Navy at the end of FY2020. ONI projects that China will have 400 battle force ships by 2025, and 425 by 2030.9

China’s naval ships, aircraft, and weapons are now much more modern and capable than they were at the start of the 1990s, and are now comparable in many respects to those of Western navies. ONI states that “Chinese naval ship design

***

9 Source for China’s number of battle force ships: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 3. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 3

and material quality is in many cases comparable to [that of] USN [U.S. Navy] ships, and China is quickly closing the gap in any areas of deficiency.”10

***

10 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 3. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 4

Although China’s naval modernization effort has substantially improved China’s naval capabilities in recent years, China’s navy currently is assessed as having limitations or weaknesses in certain areas, including joint operations with other parts of China’s military, antisubmarine warfare (ASW), long-range targeting, and a lack of recent combat experience. China is working to reduce or overcome such limitations and weaknesses.13 Although China’s navy has limitations and weaknesses, it may nevertheless be sufficient for performing missions of interest to Chinese leaders. As China’s navy reduces its weaknesses and limitations, it may become sufficient to perform a wider array of potential missions.

***

13 For example, China’s naval shipbuilding programs were previously dependent on foreign suppliers for some ship components. ONI, however, states that “almost all weapons and sensors on Chinese naval ships are produced in-country, and China no longer relies on Russia or other countries for any significant naval ship systems.” (Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, pp. 2-3. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.)

p. 8

ONI states that “China’s submarine force continues to grow at a low rate, though with substantially more-capable submarines replacing older units. Current expansion at submarine production yards could allow higher future production numbers.” ONI projects that China’s submarine force will grow from a total of 66 boats (4 SSBNs, 7 SSNs, and 55 SSs) in 2020 to 76 boats (8 SSBNs, 13 SSNs, and 55 SSs) in 2030.21

China’s newest series-built SS design is the Yuan-class (Type 039) SS (Figure 4), its newest SSN class is the Shang-class (Type 093) SSN (Figure 5), and its newest SSBN class is the Jin (Type 094) class SSBN (Figure 6). ONI states that “nuclear submarines are solely produced at Huludao Shipyard and typically undergo two to four years of outfitting and sea-trials before becoming operational. Since 2006, eight nuclear submarines have reached IOC [initial operational capability], for an average of one every 15 months…. Diesel-Electric submarines are produced at two shipyards and typically undergo approximately one year of outfitting and sea-trials before becoming operational.”22

***

21 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 1. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

22 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 3. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 10

Aircraft Carriers

Overview

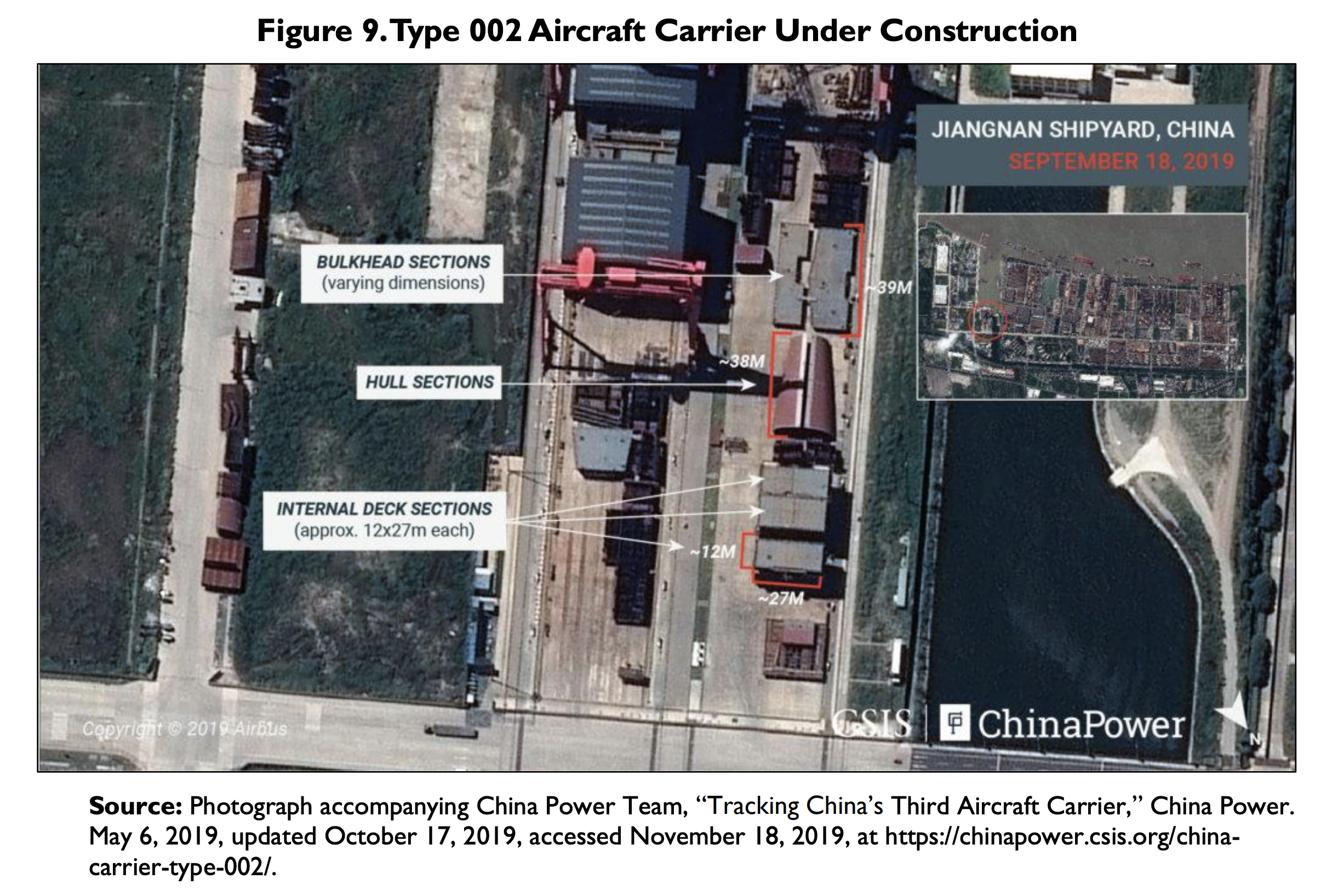

China’s first aircraft carrier, Liaoning (Type 001) (Figure 7), entered service in 2012. China’s second aircraft carrier (and its first fully indigenously built carrier), Shandong (Type 001A) (Figure 8), entered service on December 17, 2019. China’s third carrier, the Type 002 (Figure 9), is under construction; ONI expects it to enter service by 2024.26

Ronald O’Rourke, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, RL33153 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 18 March 2020).

FIGURE 9: TYPE 002 AIRCRAFT CARRIER UNDER CONSTRUCTION

***

26 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 15

ONI states that Type 055 ships are being built by two shipyards, and that multiple ships in the class are currently under construction.41

***

41 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 16

China since the early 1990s has also put into service multiple new classes of indigenously built frigates, the most recent of which is the Jiangkai II (Type 054A) class (Figure 13), which displaces about 4,000 tons. ONI states that 30 Type 054As entered service between 2008 and 2019, and that no additional Type 054As are currently under construction.44

***

44 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 17

China is also building a new type of corvette (i.e., a light frigate, or FFL) called the Jiangdao class or Type 056 (Figure 14), which displaces about 1,500 tons. Type 056 ships are being built at a high annual rate in four shipyards. The first was commissioned in 2013. DOD states that “more than 40 of these corvettes entered service by the end of 2018, and more than a dozen more are currently under construction or outfitting.”43 The 42nd and 43rd were reportedly commissioned into service in December 2019.44 ONI states that as of February 2020, more than 50 had entered service and another 15 were under construction.47

***

47 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission

p. 20

On September 25, 2019, China launched (i.e., put into the water for the final stages of its construction) the first of a new type of amphibious assault ship48 called the Type 075 (Figure 16, Figure 17, and Figure 18) that has an estimated displacement of 30,000 to 40,000 tons, compared to 41,000 to 45,000 tons for U.S. Navy LHA/LHD-type amphibious assault ships.49 ONI states that as of February 2020, three Type 075s, including the first one, were under construction.53

***

53 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 22

Numbers of Ships; Comparisons to U.S. Navy

The planned ultimate size and composition of China’s navy is not publicly known. The U.S. Navy makes public its force-level goal and regularly releases a 30-year shipbuilding plan that shows planned procurements of new ships, planned retirements of existing ships, and resulting projected force levels, as well as a five-year shipbuilding plan that shows, in greater detail, the first five

p. 23

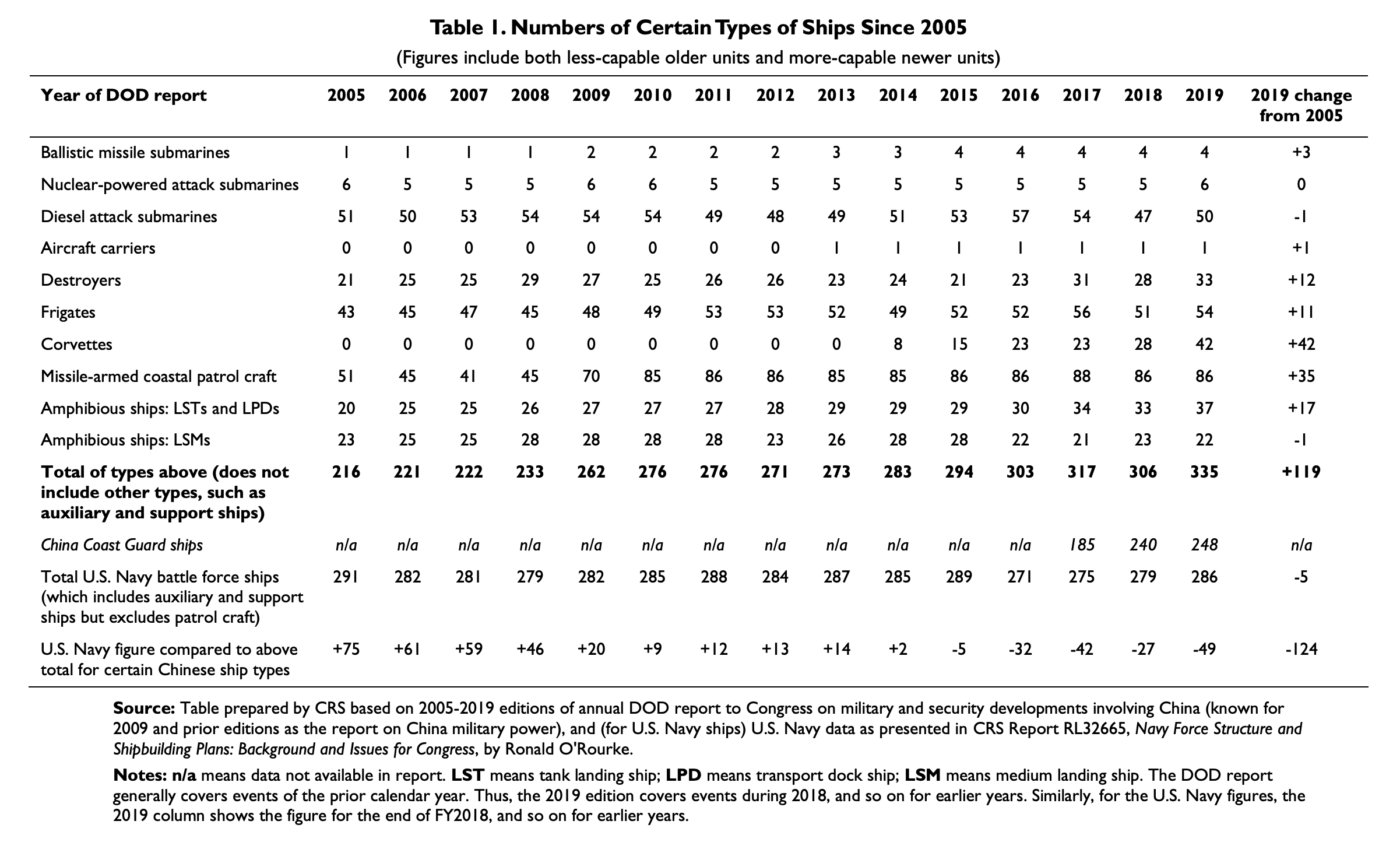

years of the 30-year shipbuilding plan.57 In contrast, China does not release a navy force-level goal or detailed information about planned ship procurement rates, planned total ship procurement quantities, planned ship retirements, and resulting projected force levels. It is possible that the ultimate size and composition of China’s navy is an unsettled and evolving issue even among Chinese military and political leaders. Table 1 shows numbers of certain types of Chinese navy ships from 2005 to the present (and the number of China coast guard ships from 2017 to the present) as presented in DOD’s annual reports on military and security developments involving China. DOD states that China’s navy “is the region’s largest navy, with more than 300 surface combatants, submarines, amphibious ships, patrol craft, and specialized types.”58 DIA states that “although the overall inventory has remained relatively constant, the PLAN is rapidly retiring older, single-mission warships in favor of larger, multimission ships equipped with advanced antiship, antiair, and antisubmarine weapons and sensors and C2 [command and control] facilities.”59

As can be seen in Table 1, about 65% of the increase since 2005 in the number of Chinese navy ships shown in the table (a net increase of 77 ships out of a total net increase of 119 ships) resulted from increases in missile-armed fast patrol craft starting in 2009 (a net increase of 35 ships) and corvettes starting in 2014 (42 ships). These are the smallest surface combatants shown in the table. The net 35-ship increase in missile-armed fast patrol craft was due to the construction between 2004 and 2009 of 60 new Houbei (Type 022) fast attack craft60 and the retirement of 25 older fast attack craft that were replaced by Type 022 craft. The 42-ship increase in corvettes is due to the Jingdao (Type 056) corvette program discussed earlier. ONI states that “a significant portion of China’s Battle Force consists of the large number of new corvettes and guided-missile frigates recently built for the PLAN.”61

As can also be seen in the table, most of the remaining increase since 2005 in the number of Chinese navy ships shown in the table is accounted for by increases in destroyers (12 ships), frigates (11 ships), and amphibious ships (17 ships). Most of the increase in frigates occurred in the earlier years of the table; the number of frigates has changed little in the later years of the table. Table 1 lumps together less-capable older Chinese ships with more-capable modern Chinese ships. Thus, in examining the numbers in the table, it can be helpful to keep in mind that for many of the types of Chinese ships shown in the table, the percentage of the ships accounted for by more-capable modern designs was growing over time, even if the total number of ships for those types was changing little. For reference, Table 1 also shows the total number of ships in the U.S. Navy (known technically as the total number of battle force ships), and compares it to the total number of Chinese ships shown in the table. The result is an apples-vs.-oranges comparison, because the Chinese figure excludes certain ship types, such as auxiliary and support ships, while the U.S. Navy figure includes auxiliary and support ships but excludes patrol craft.

***

58 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

61 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED

p. 24

As can also be seen in the table, most of the remaining increase since 2005 in the number of Chinese navy ships shown in the table is accounted for by increases in destroyers (12 ships), frigates (11 ships), and amphibious ships (17 ships). Most of the increase in frigates occurred in the earlier years of the table; the number of frigates has changed little in the later years of the table.

Table 1 lumps together less-capable older Chinese ships with more-capable modern Chinese ships. Thus, in examining the numbers in the table, it can be helpful to keep in mind that for many of the types of Chinese ships shown in the table, the percentage of the ships accounted for by more-capable modern designs was growing over time, even if the total number of ships for those types was changing little.

For reference, Table 1 also shows the total number of ships in the U.S. Navy (known technically as the total number of battle force ships), and compares it to the total number of Chinese ships shown in the table. The result is an apples-vs.-oranges comparison, because the Chinese figure excludes certain ship types, such as auxiliary and support ships, while the U.S. Navy figure includes auxiliary and support ships but excludes patrol craft.

***

China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 25

TABLE 1: NUMBERS OF CERTAIN TYPES OF SHIPS SINCE 2005

Ronald O’Rourke, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, RL33153 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 18 March 2020).

p. 26

Table 2 shows comparative numbers of Chinese and U.S. battle force ships. Battle force ship are the types of ships that count toward the quoted size of the Navy. For China, the battle force ships total excludes the missile-armed coastal patrol craft shown in Table 1, but includes auxiliary and support ships that are not shown in Table 1. Compared to the comparison shown in Table 1, the comparison Table 2 is closer to being an apples-to-apples comparison of the two navies’ numbers of ships. Even so, it is important to keep in mind the differences in composition between the two navies. The U.S. Navy, for example, has many more aircraft carriers, nuclear-powered submarines, and cruisers and destroyers, while China’s navy has many more diesel attack submarines, frigates, and corvettes.

TABLE 2: NUMBERS OF BATTLE FORCE SHIPS, 2000-2030

Relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities are sometimes assessed by showing comparative numbers of U.S. and Chinese ships. Although the total number of ships in a navy (or its aggregate tonnage) is relatively easy to calculate, it is a one-dimensional measure that leaves out numerous other factors that bear on a navy’s capabilities and how those capabilities compare to its assigned missions. As a result, as discussed in further detail in Appendix A, comparisons of the total numbers of ships in the PLAN and the U.S. Navy are highly problematic as a means of assessing relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities and how those capabilities compare to the missions assigned to those navies. At the same time however, an examination of the trends over time in the relative numbers of ships can shed some light on how the relative balance of U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities might be changing over time.

REPORT SUMMARY

In an international security environment of renewed great power competition, China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, has become the top focus of U.S. defense planning and budgeting. China’s navy, which China has been steadily modernizing for roughly 25 years, since the early to mid-1990s, has become a formidable military force within China’s near-seas region, and it is conducting a growing number of operations in more-distant waters, including the broader waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and waters around Europe. China’s navy is viewed as posing a major challenge to the U.S. Navy’s ability to achieve and maintain wartime control of blue-water ocean areas in the Western Pacific—the first such challenge the U.S. Navy has faced since the end of the Cold War—and forms a key element of a Chinese challenge to the long-standing status of the United States as the leading military power in the Western Pacific.

China’s naval modernization effort encompasses a wide array of platform and weapon acquisition programs, including anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), submarines, surface ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles (UVs), and supporting C4ISR (command and control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems. China’s naval modernization effort also includes improvements in maintenance and logistics, doctrine, personnel quality, education and training, and exercises.

China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, is assessed as being aimed at developing capabilities for addressing the situation with Taiwan militarily, if need be; for achieving a greater degree of control or domination over China’s near-seas region, particularly the South China Sea; for enforcing China’s view that it has the right to regulate foreign military activities in its 200-mile maritime exclusive economic zone (EEZ); for defending China’s commercial sea lines of communication (SLOCs), particularly those linking China to the Persian Gulf; for displacing U.S. influence in the Western Pacific; and for asserting China’s status as the leading regional power and a major world power.

Consistent with these goals, observers believe China wants its navy to be capable of acting as part of a Chinese anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) force—a force that can deter U.S. intervention in a conflict in China’s near-seas region over Taiwan or some other issue, or failing that, delay the arrival or reduce the effectiveness of intervening U.S. forces. Additional missions for China’s navy include conducting maritime security (including antipiracy) operations, evacuating Chinese nationals from foreign countries when necessary, and conducting humanitarian assistance/disaster response (HA/DR) operations.

The U.S. Navy in recent years has taken a number of actions to counter China’s naval modernization effort. Among other things, the U.S. Navy has shifted a greater percentage of its fleet to the Pacific; assigned its most-capable new ships and aircraft and its best personnel to the Pacific; maintained or increased general presence operations, training and developmental exercises, and engagement and cooperation with allied and other navies in the Pacific; increased the planned future size of the Navy; initiated, increased, or accelerated numerous programs for developing new military technologies and acquiring new ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles, and weapons; begun development of new operational concepts (i.e., new ways to employ Navy and Marine Corps forces) for countering Chinese maritime A2/AD forces; and signaled that the Navy in coming years will shift to a more-distributed fleet architecture that will feature a smaller portion of larger ships, a larger portion of smaller ships, and a substantially greater use of unmanned vehicles. The issue for Congress is whether the U.S. Navy is responding appropriately to China’s naval modernization effort.

AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY—RONALD O’ROURKE

Mr. O’Rourke is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the Johns Hopkins University, from which he received his B.A. in international studies, and a valedictorian graduate of the University’s Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, where he received his M.A. in the same field.

Since 1984, Mr. O’Rourke has worked as a naval analyst for the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress. He has written many reports for Congress on various issues relating to the Navy, the Coast Guard, defense acquisition, China’s naval forces and maritime territorial disputes, the Arctic, the international security environment, and the U.S. role in the world. He regularly briefs Members of Congress and Congressional staffers, and has testified before Congressional committees on many occasions.

In 1996, he received a Distinguished Service Award from the Library of Congress for his service to Congress on naval issues.

In 2010, he was honored under the Great Federal Employees Initiative for his work on naval, strategic, and budgetary issues.

In 2012, he received the CRS Director’s Award for his outstanding contributions in support of the Congress and the mission of CRS.

In 2017, he received the Superior Public Service Award from the Navy for service in a variety of roles at CRS while providing invaluable analysis of tremendous benefit to the Navy for a period spanning decades.

Mr. O’Rourke is the author of several journal articles on naval issues, and is a past winner of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Arleigh Burke essay contest. He has given presentations on naval, Coast Guard, and strategy issues to a variety of U.S. and international audiences in government, industry, and academia.