Surging Second Sea Force: China’s Maritime Law-Enforcement Forces, Capabilities, and Future in the Gray Zone and Beyond

Andrew S. Erickson, Joshua Hickey, and Henry Holst, “Surging Second Sea Force: China’s Maritime Law-Enforcement Forces, Capabilities, and Future in the Gray Zone and Beyond,” Naval War College Review 72.2 (Spring 2019): 11-25.

Click here to download a cached copy.

As China’s sea services continue to expand, the consolidating China Coast Guard (CCG) has taken the lead as one of the premier sea forces in the region—giving China, in essence, a second navy. With 1,275 hulls and counting, the CCG carries out the maritime law-enforcement activities that dominate the South China Sea as the People’s Republic exerts its claims and postures for dominance.

China’s armed forces are divided into three major organizations, each of which has a maritime subcomponent. The gray-hulled People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) claims a growing portion of the PLA’s personnel and resources; the People’s Armed Police (PAP) leads, and increasingly reflects the paramilitary character of, China’s white-hulled maritime law enforcement (MLE) forces, including the China Coast Guard (CCG); and the militia contains a growing proportion of sea-based units, the blue-hulled, PLA-controlled People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). Each of China’s three sea services is the world’s largest in terms of ship numbers. Unlike America’s military-focused shipbuilding industry, China’s massive commercial shipbuilding industry subsidizes overhead costs for construction of all three sea forces’ vessels. That explains in part how China has been able to build and modernize all three services so expeditiously, none more rapidly than its second sea force, centered on the consolidating CCG. Using a platform-based approach that spans ongoing organizational changes, complexity, and overlap, this article assesses these vessels, their order of battle, and their capabilities, as well as likely future trends and implications.

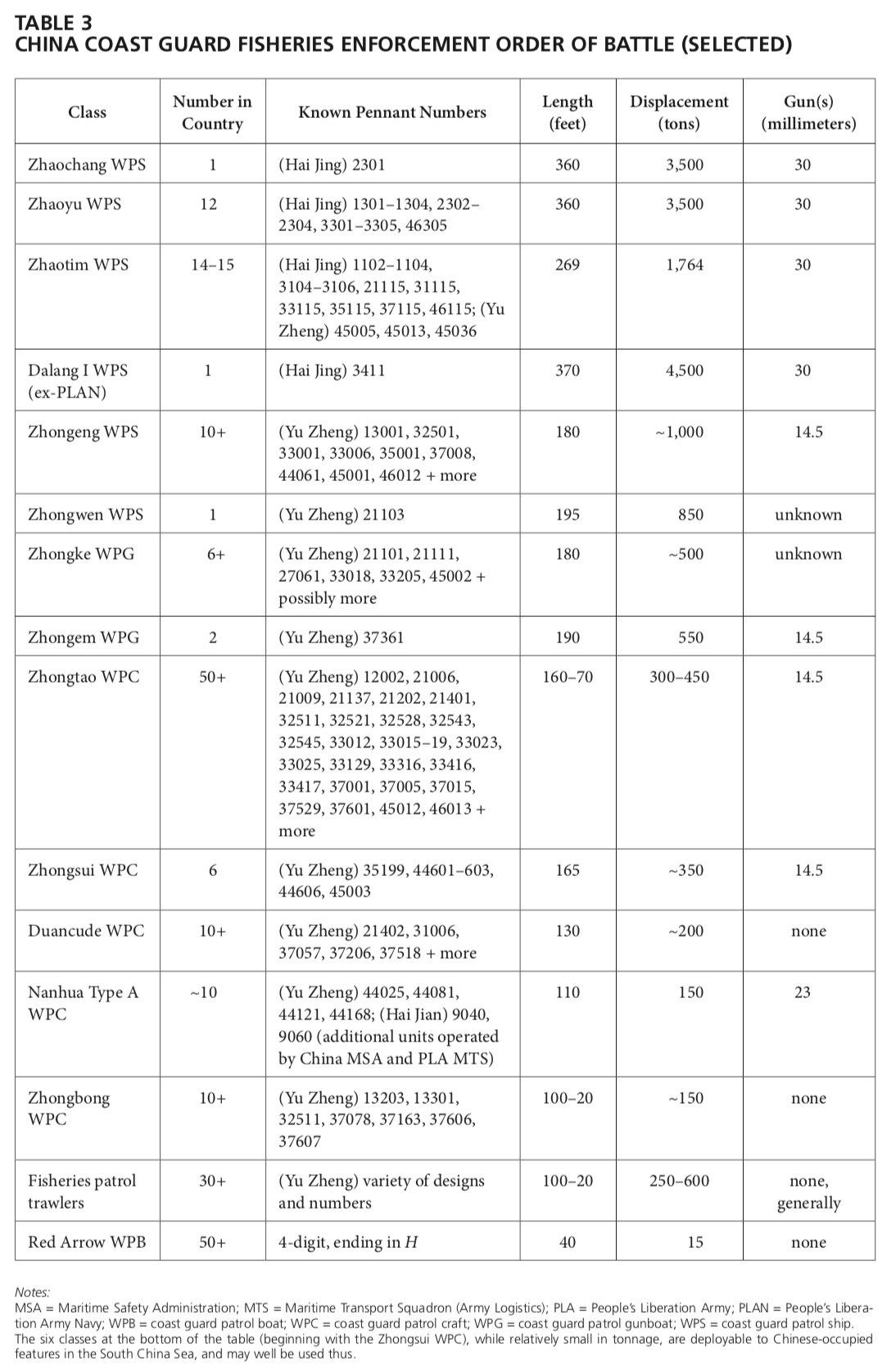

Over the past decade-plus, China has undertaken a massive MLE modernization program that has increased greatly its capability to operate MLE vessels in remote areas. A key contributor to near-seas maritime operations to further disputed sovereignty claims in the “gray zone” between peace and war, these CCG-centered MLE forces afford Beijing increasing influence over the regional maritime situation without the direct use of PLAN warships, demonstrating power while reducing the risk of escalation and allowing the PLAN to focus on other, more “naval” missions farther afield.

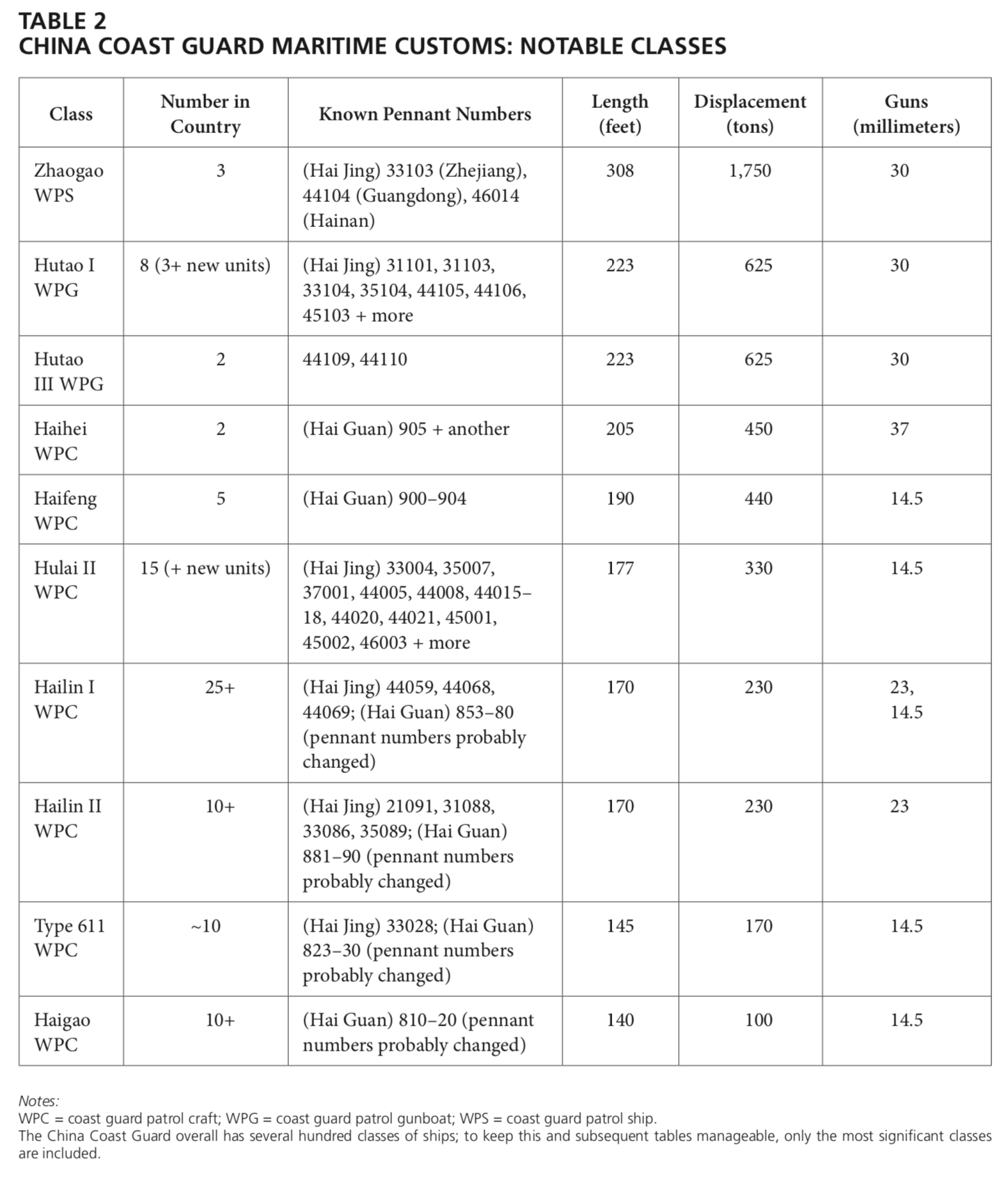

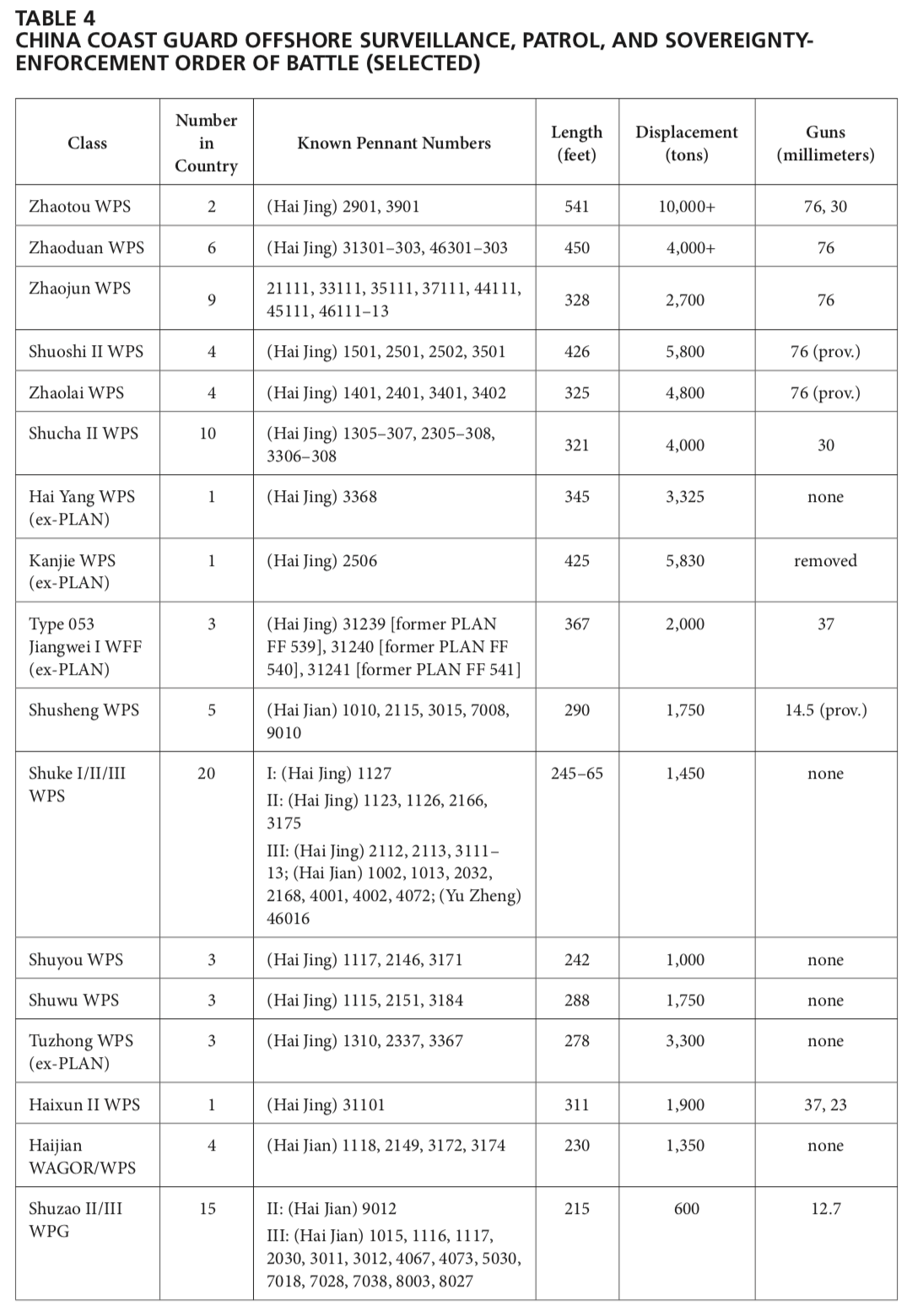

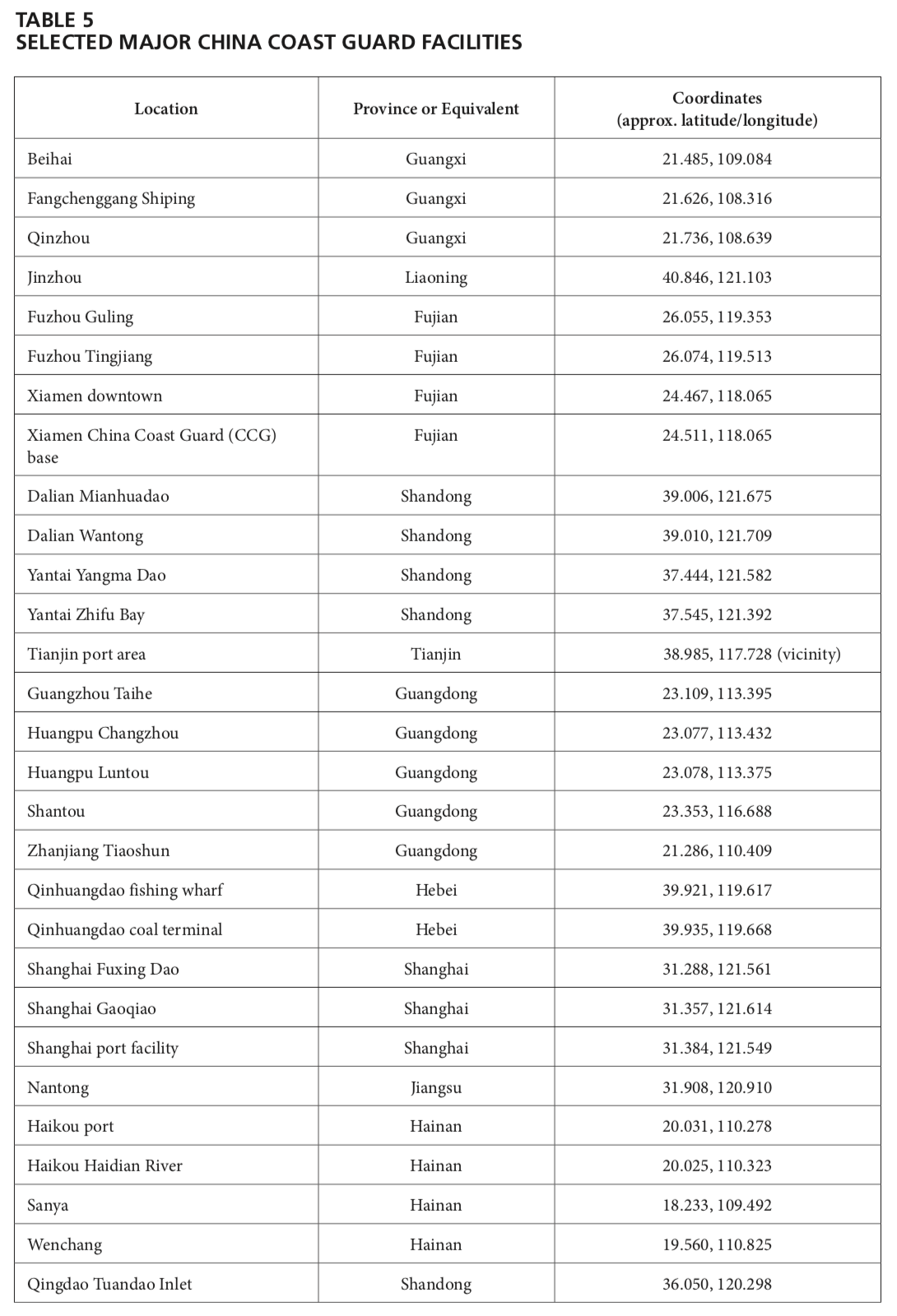

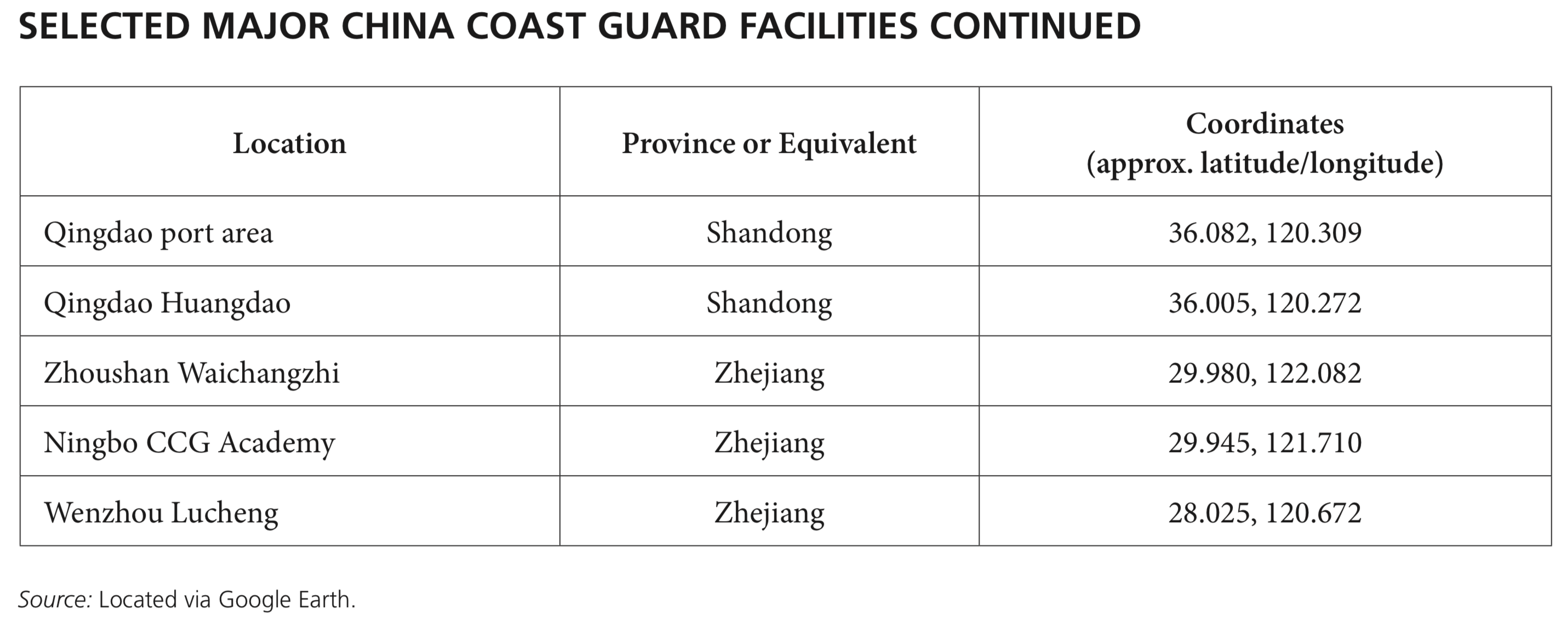

This build-out has yielded Beijing a formidable “second navy.” Today China boasts not only the world’s largest navy but also the world’s largest maritime law-enforcement fleet—by a sizable margin. As of 2017, China’s 17,000-plus CCG personnel crewed 225 ships of over five hundred tons capable of operating offshore, and at least another 1,050 vessels confined to closer waters, for a total of over 1,275—more hulls than the coast guards of all its regional neighbors combined. At more than ten thousand tons full load each, its two Zhaotou-class patrol ships are the world’s largest MLE ships.

China is applying lessons learned from the U.S. and Japanese coast guards as well as indigenous experience, including the incorporation of new ship features such as helicopters, interceptor boats, deck guns, and high-capacity water cannon. Most recently constructed CCG ships now have high-output water cannon mounted high on their superstructures. The 2014 Haiyang Shiyou (HYSY) 981 oil rig standoff demonstrated their ability to inflict damage by breaking pilothouse windows, damaging bridge-mounted equipment, forcing water down exhaust funnels, and breaking bones of crewmembers on Vietnamese vessels. Many new CCG ships have quick-launch boat ramps astern, allowing for rapid deployment of interceptor boats.

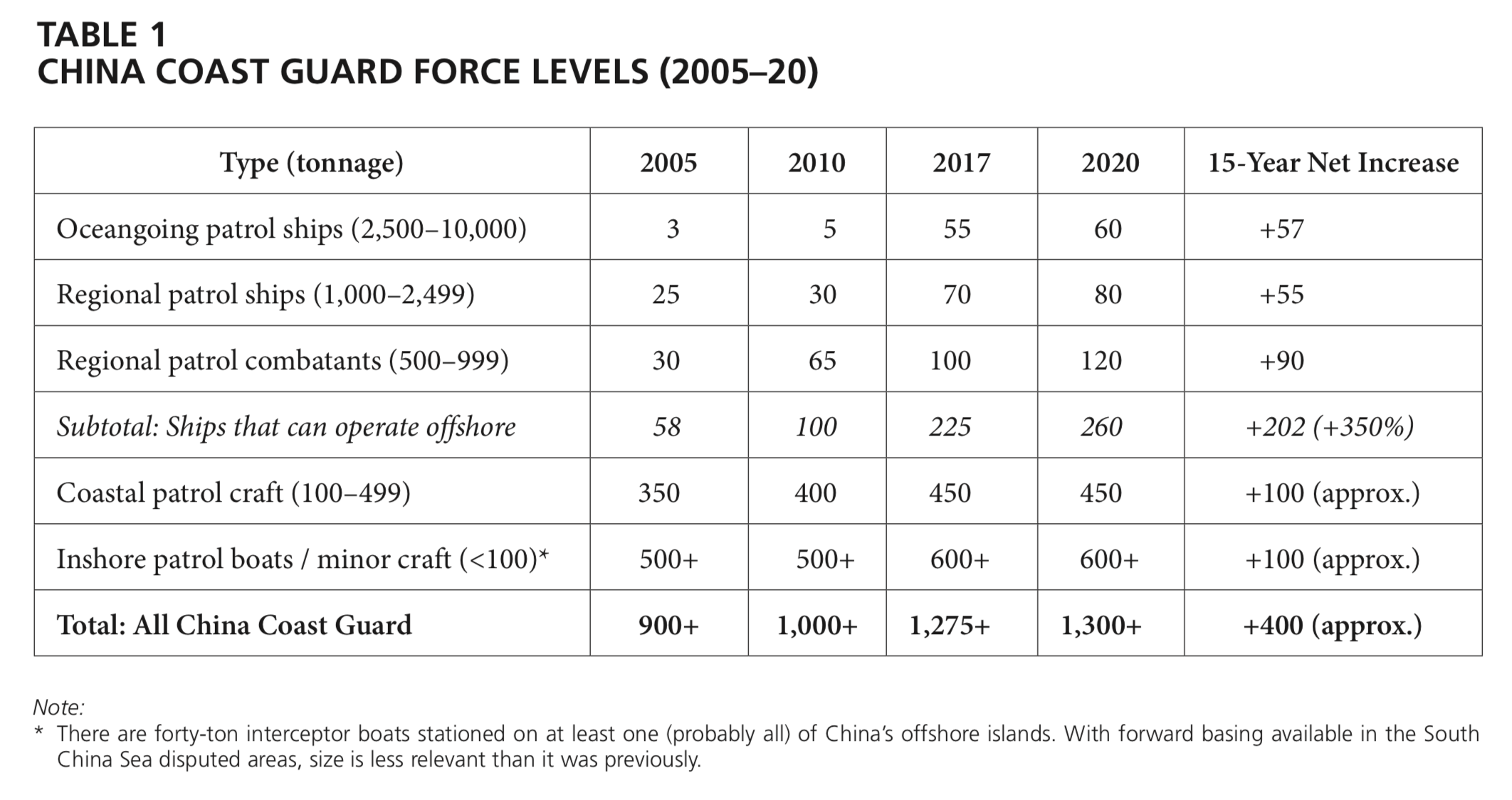

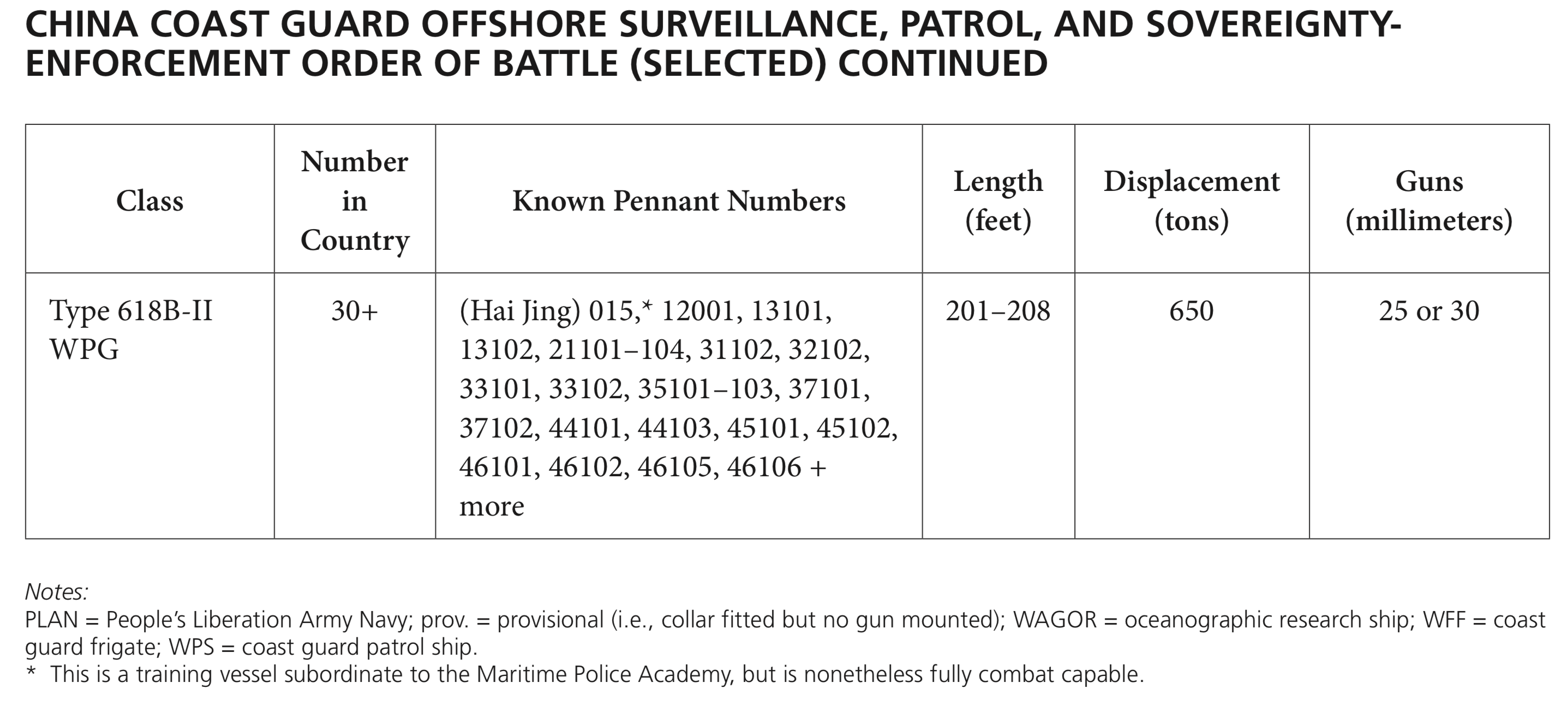

China’s MLE buildup is slowing, but far from over; in 2020, China’s coast guard is expected to have 260 ships capable of operating offshore. Many are capable of operating anywhere in the world. Numbers of small craft are not expected to change significantly; we estimate that the CCG will continue to own at least another 1,050 smaller vessels confined to closer waters, for a total of more than 1,300 hulls. From 2005 to 2020, this represents overall a fifteen-year net increase of four hundred total coast guard ships, among them 202 additional ships capable of operating offshore, representing 350 percent growth in that category. As table 1 indicates, all types of CCG ships have increased in numbers, with the most significant force-level increases, proportionately, occurring in oceangoing patrol ships (those over 2,500 tons). … … …

Open Source Research on China’s Maritime Law Enforcement Force Structure Development: Methodology & References

The following publications regarding the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s rapid development of the world’s largest maritime law enforcement (“Coast Guard”) fleet and key dynamics concerning its force structure are based on far more extensive open source research than can be reflected in the space available for citations within them:

- Andrew S. Erickson, Joshua Hickey, and Henry Holst, “Surging Second Sea Force: China’s Maritime Law-Enforcement Forces, Capabilities, and Future in the Gray Zone and Beyond,” Naval War College Review 72.2 (Spring 2019): 11-25.

- Joshua Hickey, Andrew S. Erickson, and Henry Holst, “China Maritime Law Enforcement Surface Platforms: Order of Battle, Capabilities, and Trends,” chapter in Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019), 108-132.

I therefore offer the following methodological elaboration here, in a medium free from limitations in space and formatting. The information in the abovementioned publications is not heavily based on other finished academic papers or analyses, although several of these are cited within them for context. Instead, the great majority of information noted above is based on the authors’ compilation and original analysis of a vast body of available open-source firsthand information, almost all of which is posted on the Internet. These publications’ construction statistics, order of battle, and technical characteristics are derived from a large body of open-source reporting, including:

- thousands of official shipyard contract launch announcements,

- publicly-disseminated agency reports on operations and procurement,

- compilations of information on web forums and blogs,

- commercial satellite imagery,

- and over 5,000 photographs of PRC maritime law enforcement vessels and facilities acquired online by the authors over the past decade-plus.

The greatest difficulty in accurately determining the capabilities of and order of battle for China’s maritime law enforcement (“Coast Guard”) surface fleet is the massive volume of available information in the public realm, making vetting and organization of such information a particular challenge. Furthermore, the original source of a given element of information and photography is often elusive, as posts and photography are often cross-posted among multifarious forums and blogs. Selected media and academic sources are listed below, although the vast majority of these studies’ information comes directly from tens of thousands of more specific Internet and media sources that cannot possibly be listed individually. This includes:

- Tens of thousands of photographs from official PRC media, unofficial media, foreign media, internet blogs, online image searches, and military hobbyist forums. These photographs have been collected for well over a decade and used to catalog ship pennant numbers, basing locations, physical configuration, and other features.

- Thousands of news articles in a variety of publications, ranging from well-known international publishers such as IHS Jane’s and the U.S. Naval Institute all the way down to local Chinese newspapers, which frequently post articles about maritime law enforcement (“Coast Guard”) and other shipbuilding activities within their respective regions. The great majority of these articles are posted online.

- Press releases posted on official webpages belonging to national and local maritime law-enforcement agencies announcing ceremonial activities (ship launch, contract signing, etc.)

- Press releases posted on websites belonging to shipyards, shipbuilders, ship design organizations, local governments, subcontractors (i.e., engine suppliers), and other related corporate interests, which frequently and regularly post these releases in order to advertise participation in maritime law enforcement (“Coast Guard”) ship programs.

Given the vast numbers of individual articles, photographs, and standalone statements used to compile this information over a decade, it is impossible to cite specific items whose compilation allowed the statistics and analysis within the abovementioned publications to be completed. Instead, the below list cites general sources from which the authors obtained most of the information, as well as the online link to the site, when relevant. It should be noted that much of the information on the forum and blog sites originated from other places on the Internet which are not necessarily listed, so original sources in many cases are not known. This is especially the case regarding photography.

Web Forums and Blogs:

- www.top81.com.cn/

- www.fyjs.cn

- www.wikipedia.org

- www.wikivisually.com

- www.cjdby.com

- www.china-defense.com

- www.sinodefence.com

- www.hobbyshanghai.net

News Organizations and Websites:

- http://mil.news.sina.com.cn

- CCTV (Official)

- Xinhua News

- Guangzhou Zhongchuan Huangpu Zaochuan Youxian Gongsi

- Fujiang Xinwen Wang

- Jiaodong Shuichan

- Wendeng Xinwen Wang

- Wendeng Shi Renmin Zhengfu

- Shandongsheng Haiyang yu Yuyu Xinxi Wang

- Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Shanghai Haishiju

- Tengxun Dachu Wang

- Guojia Haiyangju Beihai Fenju

- Guangxi Hiashiju

- Zhongchuan Zhonggong

- Xinmin Wang

- Xinhua Wang

- Zhuhai Xinwen Wang

- 中国海洋报 [China Ocean News]

- http://www.andrewerickson.com/2019/02/the-ryan-martinson-bookshelf-unique-insights-into-chinas-coast-guard-maritime-policies-and-activities-at-sea-2/

- http://www.andrewerickson.com/2019/02/the-china-maritime-militia-bookshelf-complete-with-latest-recommendations-fact-sheet-2/