Honored to Contribute “China” Chapter in New Oxford University Press Volume—“Comparative Grand Strategy”

Andrew S. Erickson, “China,” in Thierry Balzacq, Peter Dombrowski, and Simon Reich, eds., Comparative Grand Strategy: A Framework and Cases (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019), 73-98.

Abstract:

Scholars still debate the very notion of a Chinese grand strategy. Nonetheless, recent leadership and policy statements, and their explicit linkage to historical patterns of Chinese behavior, suggest that China may well have the most forthright example of a grand strategy of any major power today. This chapter is composed of five parts in substantiating that claim. First, it surveys Xi’s contemporary grand strategy. Second, it discusses the historical foundations of Xi’s initiatives. Third, it lists the modern factors that shape and complicate China’s grand strategic efforts. Fourth, it examines the two major contemporary prongs that link the global to the national strategy: the external Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aimed at binding Eurasia to China through infrastructure and commercial development; and the internal efforts to consolidate societal stability with a stronger surveillance state. Together, the chapter argues, these initiatives are designed to mitigate the impact of demographic decline, an S-curved slowdown in the growth of China’s economy, with the goal of buttressing other elements of national power.

Key Words:

China, grand strategy, Xi Jinping, Chinese Communist Party, Belt and Road Initiative

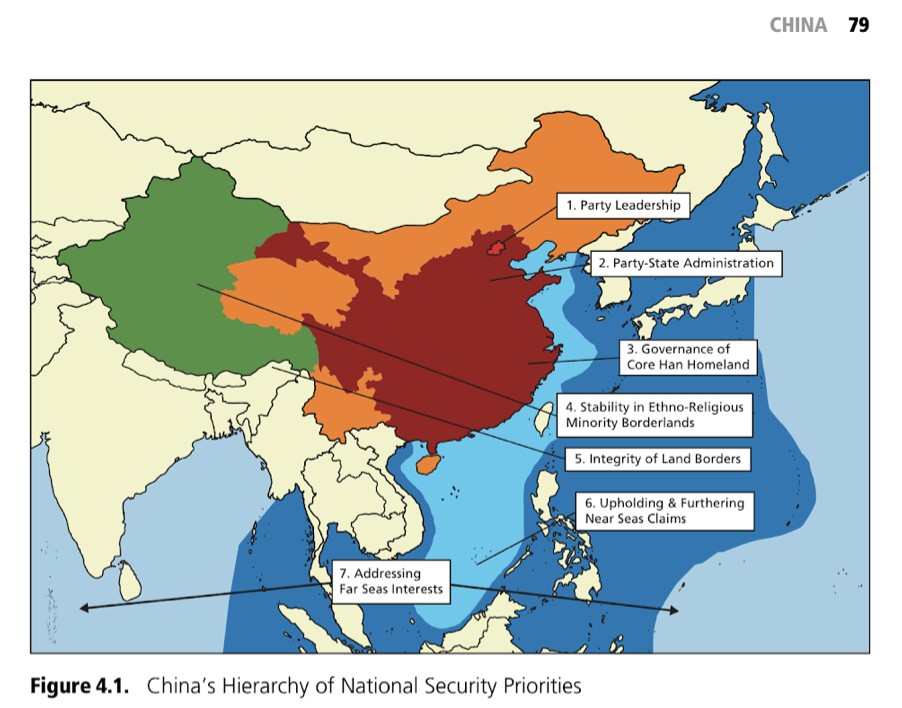

“Figure 4.1: China’s Hierarchy of National Security Priorities,“ in “China,” in Thierry Balzacq, Peter Dombrowski, and Simon Reich, eds., Comparative Grand Strategy: A Framework and Cases (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019), 79.

The very concept of a Chinese grand strategy (大战略) remains surprisingly controversial, with extreme interpretations ranging in recent years from ad-hoc opportunism to century-long plans. The truth is more complex than either extreme, but to the extent that any great power has a grand strategy today, China most certainly does. Under the ambitious reign of Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s goal of achieving a twenty-first century version of the glory and successes of Qing dynasty China at its eighteenth century height at home and abroad has been packaged rhetorically as the “China Dream” of “national rejuvenation.” This quest to make China great again represents an all-encompassing thirty-five-year plan that is the most forthright and ambitious of any major power. The potential specifics, shaped in part by emerging opportunities, may be gleaned deductively from leadership and policy statements and inductively from capabilities and actions. Despite relative strategic clarity, however, gathering challenges suggest that there is no guarantee of ever-rapid outward expansion of China’s geostrategic accomplishments to include Xi’s most ambitious, distant targets. Indeed, both China’s history and current context suggest that its leaders pursue a hierarchy of priorities akin to a Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs for a “re-rising” great power. Given favorable conditions allowing achievements closer to home, CCP leaders will pursue further progress in ever-distant geographic layers and strategic domains; but if they encounter significant difficulties they will likely retrench to protect “core” interests—most importantly, political continuity. A consequential leader, Xi is pursuing objectives towards the top of the “band” (range of possibilities, in ascending level of ambitiousness) in strength and speed that might be expected of a paramount CCP leader of his generation. But even he cannot ensure their realization and would almost certainly fall back on such top priorities as preserving the continuity of CCP rule if circumstances rendered broader ambitions unrealistic. To elucidate these critical dynamics and their implications for China’s grand strategy, its development over time, its prospects for further evolution, and the implications, this chapter (1) survey’s Xi’s grand strategy, (2) discusses its historical continuities, (3) lists the modern factors that shape and complicate it, and then focuses on how it is operationalized (4) internationally through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to bind Eurasia to China through infrastructure and commercial development, and (5) domestically by undergirding societal stability with a stronger surveillance state, the last as part of initiatives designed to mitigate the impact of demographic decline and an S-curved slowdown in the growth of China’s economy and other elements of national power.

4.1 Xi’s grand strategy for China

While some scholars still contest the very notion of a Chinese grand strategy, recent leadership and policy statements and their explicit linkage to historical patterns suggest that China may well have the most forthright grand strategy of any major power today. To the extent that any nation may be said to have a grand strategy, China certainly has one.

China’s paramount leader, Xi Jinping, has a great decisional power and his vision matters greatly. A consequential leader, he has consolidated his power and clearly eclipsed his immediate predecessors Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin in a way that might well have eluded alternative contenders. The recent overturning of the ten-year term limits on China’s presidency instituted by its last leader of similar consequence—the more unassuming, domestically focused Deng Xiaoping, who reversed Maoist excesses and launched pragmatic reforms—gives Xi both a potentially long time horizon to implement his grand strategy and a staggering degree of ownership for its success or failure. Xi portrays his leadership as crucial for now, and his eighty-million-member party’s leadership as crucial out to any foreseeable time horizon. Chinese grand strategy overall under Xi is not secret. His goal is to make China empowered and respected again, at home and abroad. To facilitate the internal and external implementation of his strategy, Xi is overseeing sweeping bureaucratic, Party, and military reforms.

Xi Jinping’s speech at the 19th CCP National Congress on October 18, 2017 spans sixty-five dense pages in the official English translation, but is readily summarized. A commentary in China’s state media offered a pithy encapsulation of Xi’s speech: “The Chinese nation . . . has stood up, grown rich, and become strong. It will move toward center stage and make greater contributions for mankind.” By this logic, China’s success proves that its form of Leninist authoritarianism works: “It is time to understand China’s path, because it appears it will continue to triumph.” In the new era, Xi emphasizes, China is embarked on a domestically popular, historically redolent mission to realize the dream of national rejuvenation championed by all would-be Chinese leaders since imperial disintegration in the early twentieth century following a “Century of Humiliation” at the hands of foreign powers. Elaboration on these points is offered below. … … …

“China,” in Thierry Balzacq, Peter Dombrowski, and Simon Reich, eds., Comparative Grand Strategy: A Framework and Cases (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019), 73.

INFORMATION ON EDITED VOLUME:

This book develops a new approach in explaining how a nation’s Grand Strategy is constituted, how to assess its merits, and how grand strategies may be comparatively evaluated within a broader framework.

- Provides a new framework for analysis, enabling readers to see how Grand Strategy can be studied effectively within and across countries.

- Provides an unprecedented study of Grand Strategy, with readers able to gain a clear and focused understanding of the Grand Strategies of major, regional, and pivotal powers, and assess their relative merits across ten countries.

- Features contributions from leading scholars in the field.

The volume responds to three key problems common to both academia and policymaking. First, the literature on the concept of grand strategy generally focuses on the United States, offering no framework for comparative analysis. Indeed, many proponents of US grand strategy suggest that the concept can only be applied, at most, to a very few great powers such as China and Russia. Second, characteristically it remains prescriptive rather than explanatory, ignoring the central conundrum of why differing countries respond in contrasting ways to similar pressures. Third, it often understates the significance of domestic politics and policymaking in the formulation of grand strategies – emphasizing mainly systemic pressures. This book addresses these problems. It seeks to analyze and explain grand strategies through the intersection of domestic and international politics in ten countries grouped distinctively as great powers (The G5), regional powers (Brazil and India) and pivotal powers hostile to each other who are able to destabilize the global system (Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia). The book thus employs a comparative framework that describes and explains why and how domestic actors and mechanisms, coupled with external pressures, create specific national strategies. Overall, the book aims to fashion a valid, cross-contextual framework for an emerging research program on grand strategic analysis.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Comparing Grand Strategies in the Modern World, Thierry Balzacq, Peter Dombrowski, and Simon Reich

Part I – Major Powers

2. United States, Peter Dombrowski and Simon Reich

3. Russia, Celine Marange

4. China, Andrew S. Erickson

5. France, Thierry Balzacq

6. Great Britain, Robert Johnson

Part II – Pivotal Powers

7. Brazil, Carlos R. S. Milani and Tiago Nery

8. India, C. Christine Fair

9. Iran, Thierry Balzacq and Wendy Ramadan-Alban

10. Israel, Eitan Shamir

11. Saudi Arabia, Ghaidaa Hetou

12. European Union, Daniel Fiott and Luis Simon

13. Conclusion: The Emerging Sub-field of Comparative Grand Strategy, Norrin Ripsman