Wednesday, 30 April @ Harvard Fairbank Center: “Film Screening, Part 2 – River Elegy (河殇), Episodes 3 – 6 featuring Andrew S. Erickson & Shih-Diing Liu”

This event is sponsored and organized by the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University.

- Harvard University, CGIS South S020, Belfer Case Study Room

- 1730 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, MA 02138

- Wednesday, April 30 @ 1:30 pm – 4:30 pm

Andrew S. Erickson, Professor of Strategy, China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College; Visiting Scholar 2024-25, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University

Shih-Diing Liu, Professor of Communication and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, University of Macau; Visiting Scholar 2024-25, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University

Join us for the second part of our special screening of River Elegy (河殇), the landmark 1988 Chinese documentary series that ignited nationwide debate with its bold critique of China’s historical path and traditional culture. This event will feature commentary from two of our current visiting scholars, Andrew S. Erickson (U.S. Naval War College) and Shih-Diing Liu (University of Macau).

We will present a newly restored digital transfer of the final four episodes of River Elegy: “Aura” (Episode 3), “A New Era” (Episode 4), “Worries” (Episode 5), and “Azure” (Episode 6). All episodes are in Chinese with newly translated, English-language subtitles.

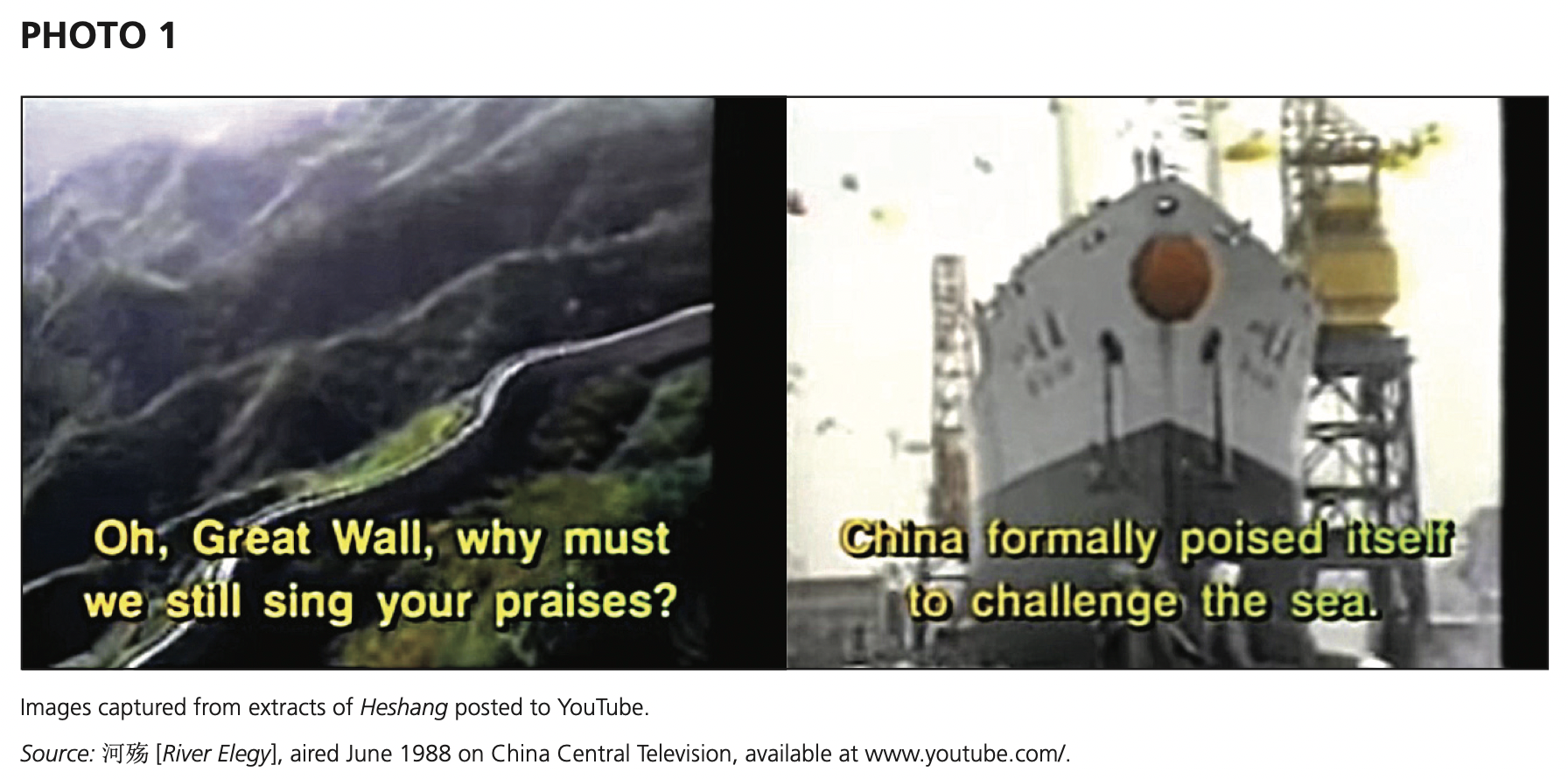

First aired on CCTV1 in June 1988, River Elegy uses the color “yellow” (symbolizing the Yellow River and the Yellow Emperor) as a metaphor for cultural and political stagnation, contrasting it with “blue” (representing the open sea and maritime exploration) as a symbol of modernity and openness. Through poetic narration and a provocative visual collage of archival footage, the series critiques China’s Confucian traditions and historical isolationism, arguing that these forces hindered the country’s progress in the 20th century. It calls instead for reform, global engagement, and celebrates the economic liberalization taking place under Deng Xiaoping.

River Elegy struck a deep chord with a generation navigating the tensions of modernization. Its writer, Su Xiaokang, quickly became one of China’s most prominent public intellectuals. The documentary received high-level endorsement from Party figures including former president Yang Shangkun, Deng Pufang (son of Deng Xiaoping), and premier Zhao Ziyang—each of whom supported and even hosted special screenings of the series. But following the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests—which some scholars argue were partly catalyzed by River Elegy’s widespread influence—the series was banned amid a sweeping political crackdown.

Decades later, River Elegy remains a powerful historical document. Its themes continue to resonate, particularly as the liberal values that the series championed—democracy, human rights, the rule of law—appear increasingly embattled, not only in China, but also in the United States and around the world.

Andrew S. Erickson is a Professor of Strategy in the U.S. Naval War College (NWC)’s China Maritime Studies Institute, which he helped establish and has served as Research Director, and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. He testifies periodically before Congress and briefs leading officials, including the Secretary of Defense. Erickson helped to escort the Commander of China’s Navy on a visit to Harvard and subsequently to establish, and to lead the first iteration of, NWC’s first naval officer exchange program with China. He has received the Navy Superior Civilian Service Medal, NWC’s inaugural Civilian Faculty Research Excellence Award, and NBR’s inaugural Ellis Joffe Prize for PLA Studies. His research focuses on Indo-Pacific defense, international relations, technology, and resource issues. Dr. Erickson was a 2019-2022 Visiting Scholar.

Shih-Diing Liu is Professor of Communication and a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, University of Macau. Liu’s research focuses on exploring the emotional dynamics of politics, the formation of popular identity, the expressive and embodied forms of political practices, and the psychology of nationalism in contemporary China. His books include The Politics of People: Protest Cultures in China (SUNY Press, 2019) and Affective Spaces: The Cultural Politics of Emotion in China (Edinburgh University Press, 2024, with Wei Shi). Continuing with a focus on emotion from the Affective Spaces project, his current research explores the intersection of affect and gender in contemporary China. Arguing that Chinese gender has increasingly become an archive of feelings marked by ambivalence toward authorities, this book project uncovers the power of emotion in negotiating the gendered order. Meanwhile, he is also working on a book project that explores the emotional capabilities of Artificial Intelligence.

Schedule:

1:30 pm: Introductory Remarks by Shih-Diing Liu

1:45 pm: Episode 3: “Aura” & Episode 4: “A New Era” (70 min.)

3:00 pm: Comments from Andrew S. Erickson

3:15 pm: Episode 5: “Worries” & Episode 6: “Azure” (63 min.)

***

More detailed version:

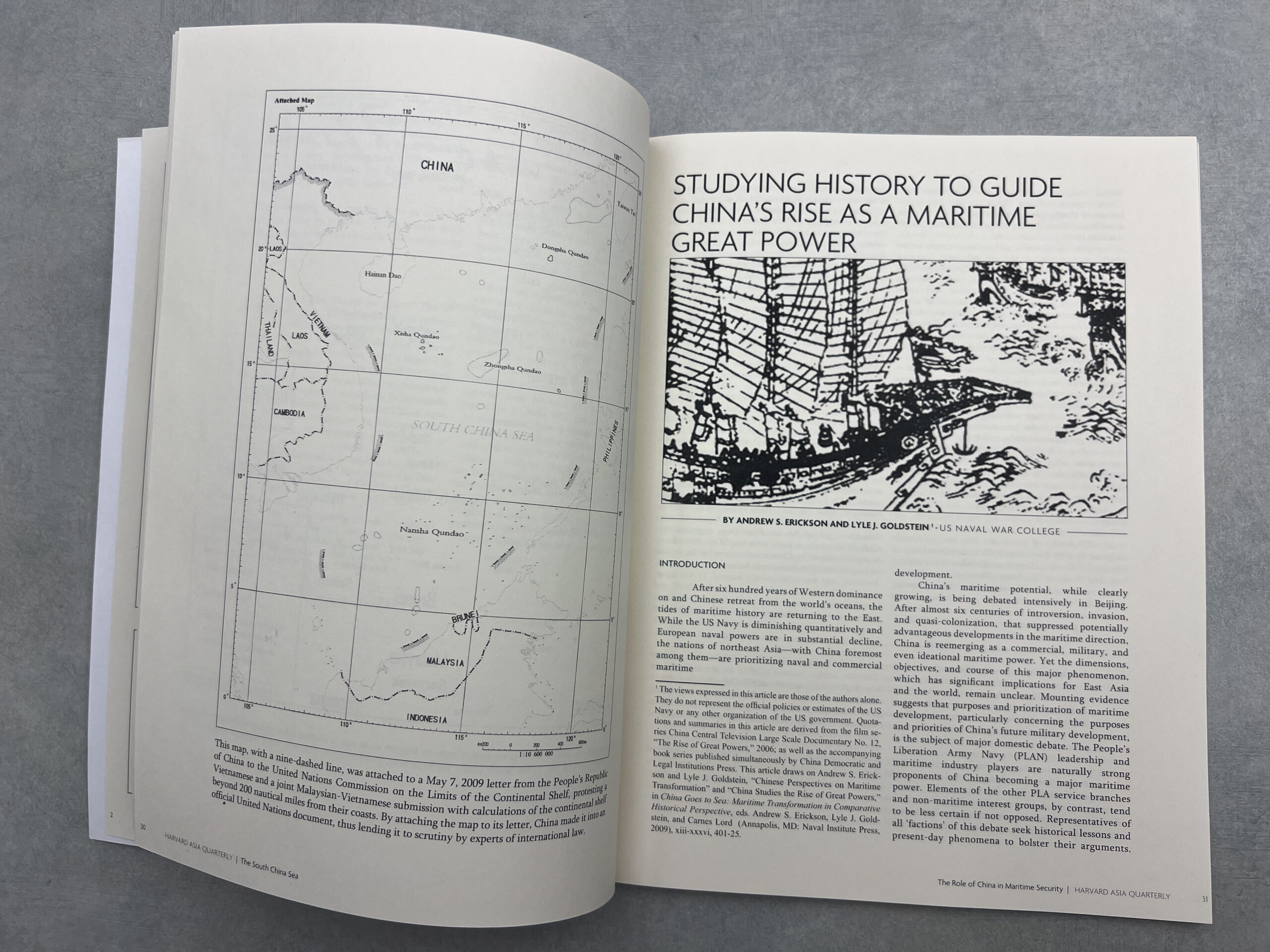

Andrew S. Erickson and Lyle J. Goldstein, “China Studies the Rise of the Great Powers,” in Andrew S. Erickson, Lyle J. Goldstein, and Carnes Lord, eds., China Goes to Sea: Maritime Transformation in Comparative Historical Perspective (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, July 2009; paperback 15 June 2021), 401–25.

***