China’s Military Development: Maritime and Aerospace Dimensions

Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Military Development: Maritime and Aerospace Dimensions,” keynote address at Defense Forum Foundation, B-339 Rayburn House Office Building, Capitol Hill, Washington, DC, 17 July 2009.

Summary of Presentation

China is achieving a rapid if uneven revolution in maritime and aerospace capabilities. These capabilities are divided among China’s Second Artillery, Air Force, Navy, General Armaments Department—and even the ground forces, to some extent. Competition may emerge among these services for control of new forces, such as military space capabilities. China has methodically acquired technologies which target limitations in the physics of high technology warfare, or “physics-based limitations.” These can place high-end competitors, potentially the U.S. Navy and other armed services, on the costly end of an asymmetric arms race. In addition to these widespread incremental improvements, China is on the verge of achieving several potentially game-changing breakthroughs; most importantly anti-ship ballistic missiles, but also the capability to launch streaming cruise missile attacks, and anti-satellite attacks, and even the application of satellite navigation to facilitate military operations. These achievements promise to radically improve the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s military’s access denial capabilities by allowing it to hold at risk a wide variety of surface and air-based assets, were they to enter strategically vital zones on China’s contested maritime periphery in the event of conflict.

China does face some ongoing challenges in developing its military. Lagging areas include human capital, realism of training, hardware and operational deficiencies, C4ISR, and target de-confliction with existing systems and strategies. China has many ways to mitigate these limitations for kinetic operations around Taiwan or other areas of its maritime periphery and potentially for non-kinetic peacetime operations or phase-zero operations further afield. Conducting high-intensity wartime operations in contested environments beyond Taiwan at the present would tend to be much more challenging for China, however. And China would need to achieve major qualitative and quantitative improvements, particularly in aerospace, to progress in that area. That, in turn, would give China vulnerabilities, in some ways of the same sort that it is able to target on the part of the U.S. right now. Looking forward, the biggest strategic question for U.S. Navy planners is whether and to what extent China will choose to develop the aerospace capabilities and other capabilities to support major kinetic force projection far beyond Taiwan.

Contents of Presentation

CHINA’S MILITARY DEVELOPMENT:

MARITIME AND AEROSPACE DIMENSIONS

WELCOME AND MODERATOR:

AMBASSADOR J. WILLIAM MIDDENDORF II,

CHAIRMAN, DFF

SPEAKER:

ANDREW S. ERICKSON,

FOUNDING MEMBER, CHINA MARITIME STUDIES INSTITUTE (CMSI),

U.S. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE, STRATEGIC RESEARCH DEPARTMENT

FRIDAY, JULY 17, 2009

12:30 P.M.

B-339 RAYBURN HOUSE OFFICE BUILDING

AMB. WILLIAM MIDDENDORF: Good afternoon. I’m Bill Middendorf, chairman of the Defense Forum Foundation, as I have been for about 30 years. So you’re probably tired of seeing me, but I would like to thank you for joining us today at today’s Congressional Defense and Foreign Policy Forum. I know all of you on the Hill here are very, very busy and we’re going to try to keep the program on schedule.

For those of you who are participating for the first time with us at our forums, we especially want to welcome you and hope that you’ll become a regular participant. Our forums began, as I mentioned, back in the late ’70s, early ’80s and we’ve always enjoyed great bipartisan support and participation and given the congressional staff the opportunity to hear from expert speakers and the others working in their issue areas of defense foreign policy and human rights.

Before I introduce our guest speaker, I would like to acknowledge our special guest and Defense Forum board staff, Martin Jaskula (ph), political officer from the Embassy of Poland. Martin, happy to have you here. (Applause.) … Recently retired from the Naval War College, President Admiral Shuford, Jake Shuford, an old friend of mine from – (inaudible, applause). … … …

Dr. Andrew Erickson is an associate professor of Strategic Research Department of the United States Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, and a founding member of the department’s China Maritime Studies Institute. He’s also an associate researcher at Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, a fellow in the National Committee on the U.S.-China Relation’s Public Intellectuals Program, and a member of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific.

Dr. Erickson previously worked for SAIC as a Chinese translator and technical analyst as well at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. By the way, I was one of the first to get – come in to China in 1945, when we brought our landing crafts up from the Pacific into China and I’ve never seen so much devastation in my life. …

He’s received his – and he’s also – has been with the U.S. Senate and the White House and the U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong. He received his Ph.D. and M.A. in international relations and comparative politics from Princeton, graduated magna cum laude from Amherst with a B.A. in history and political science. … And so he’s a prolific writer on East Asia defense, foreign policy technology issues and we’re grateful to have him speaking on Chinese military development, maritime and aerospace dimensions.

I have to give you an editorial. I’m extremely worried, as a former secretary of the Navy, about the Chinese naval buildup, both their anti-missile program and their own – excuse me – and their intercontinental ballistic missile capabilities. …

So – but it’s – I think, we who served – I served 17 years or so in the State Department and Defense Department, and I can tell you that the most important thing for those of us and those of you – and you have that responsibility now – is to prepare the United States against the capabilities of a potential adversary and not his intentions. State Department – you can analyze intentions one day and tomorrow they change. But capabilities don’t change and they’re permanent. And it’s your job and my job and all of our jobs, Dr. Erickson’s and everyone else’s, to analyze capabilities and know what they have so that our capabilities are equal to it.

When you look at a 10-year lead time on a D-craft (ph) ship or a major weapon system, sometimes 15 years from the first glimmer to its fruition, we have to be planning at all times. It’s far too late when the great nightfall comes to develop weapon systems when you recognize the threat. We have to plan ahead if you believe in your country and believe in preparation. So capabilities are what we focus on – all of us focus on, or we wouldn’t be in this room today, and not intentions. Admiral Shuford, would you tell us the inside story of Dr. Erickson?

ADM. JACOB SHUFORD: I could do that, thank you. Mr. Secretary, thanks very much. And we just came from spending a morning looking through the – about a foot-and-a-half of nominations for a series of leadership awards that the Navy League presents every year. And it’s fairly exhilarating and encouraging to see the absolutely extraordinary young men and women – in this sort of case it’s older men and older women – that are teed up there for us to recognize. I think that most of you in this room – I know that most of the folks up here – I’ve worked here for two years. I ran the – I was the director of the Navy Senate Liaison Office, so I’m fairly familiar with these corridors, including the corridors on what we over there would like[n to] the dark side over here in the House.

But it’s good to be back in a place where we share a similar work ethic. Those of us in the military think that we’re the only folks that work from dawn to dusk and into the evening and work 24-hour schedules, but that’s the one thing that most of the American people don’t know when they’re bring it up there and they have the sort of fantasy world that boy, it’s really cool to be working up on Capitol Hill and be a staffer up here and just have all that fun. And they don’t have any clue as to how hard you all work. And we all feel very comfortable because we share so much between our two cultures.

But – so I was asked to speak for two minutes. Paul Giarra said he knows me better than that. I have never spoken for two minutes in my life. I’m already at one minute and 30 seconds and I know we’ve got me sandwiched between Secretary Middendorf, who certainly has insights that are valuable and built on decades of extensive and profound analysis with folks who themselves are engaged continuously and extensively in the national security debate in this country and around the world. And he stays connected. And organizations like this, discussions like this are very, very important for us to leverage that kind of insight and the insight that you’re going to have in just a few minutes when Andrew comes up here and chats with you.

This is the college that I had the privilege of leading as its president for just about five years and it was a momentous time because you have to have been on the moon not to recognize that there is a strategic rudder on with regards to how we think about the application of military and naval force. We just don’t know where the heading is going to end up. We don’t know when we come amidships and say, ah, this is the right course. But you will hear some of the fundamental thinking that has evolved, and I like to think through some significant impetus from the work done at the War College and the work done specifically by the China Maritime Studies Institute [CMSI] that we established in 2005.

It has now, beside the crosscutting elements from within the other faculty at the college that bring different expertise that is not focused on China or focused on the navy, but from a number of diverse perspectives, into intersection with the very focused work done by now 14 Mandarin Chinese linguists, who are not only linguists, but also understand the naval and military issues. They understand this rudder that’s on. They work side-by-side with folks that are pulling that perspective in as a basis of understanding force employment and technology trends and political trends, so that we can do what the Secretary just said: look out there and find out what the implications are today for investments and force structure for our military and the preoccupation that he has with the Navy.

So Andrew was one of the what we call plank owners. When you build a ship, if you’re on the first ship, when it gets on the way, you were a plank owner. And Andrew is a plank owner for the China Maritime Studies Institute. It has developed over time and Andrew has been in the lead of putting the agenda together for this institution, but it goes back to the original series of workshops that we had. And just a year ago, under Admiral Roughead, when he was out at COMPACFLT, we said, we keep hearing this discussion about a maritime partnership with China. He said, what does that mean? And so we decided, well, before we go much further, we needed to define a maritime partnership with China.

So if you talk to somebody about defining a partnership, you sure as heck better be talking to the partners. So we had a very interesting week with some very senior naval flag officers and other policy and academic elite that came to the Naval War College. Because we’re an academic setting, you can do so much more that you can’t do elsewhere, and we began to explore just what a partnership with China means. And we’ve got a number of follow-on activities that are moving to continue help us to move closer toward a shared idea of that partnership.

And then here this December, we just finished a discussion on the aerospace dimension of where China and their military is headed. And the year before that, it was submarines. And so the person that has put all this together is here with us today. He is – I like to think about Andrew as a colleague, although my academic credentials don’t clearly come up to those that you heard enumerated by the secretary. But I can say that just about every afternoon, we shared some of the weights and running machines in gym – (inaudible). But without further ado, Andrew, please. Thanks. (Applause.)

ANDREW ERICKSON: Admiral Shuford, I thank you very much for that kind introduction. Secretary Middendorf – really appreciated those kind words to get us on track here. And President Scholte, thank you so much for your work and your help bringing me here today. It is a true honor to be here and I think I share a sense of urgency with many of you that a lot of things are going on here and we’d better understand what’s going on. We’d better talk about it.

I have to make the usual disclaimer. In case anyone was confused, which I doubt in this sophisticated audience is an issue, these are all my views, not those of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government. Next slide, please. These are just a couple of the major issues that I want to discuss with you today, just sort of a little run-through here. Next slide, please.

Again, I don’t think I have to convince this audience that it’s important to be following China, but I would just note that most recent National Intelligence Council report states that China will be a leading economic and military power in 2025. So as we look forward and try to anticipate the future world that we have to prepare for, as the Secretary said, I think that’s a useful data point. Next slide, please.

Now, I wish we had all day to talk about this; I recognize we don’t. I want to share with you nine major points. This is my best effort to distill the implications of our conference on China’s aerospace development and the military implications, as well as where China seems to be headed in general militarily. Number one, China’s achieving a rapid if uneven revolution in maritime and aerospace capabilities.

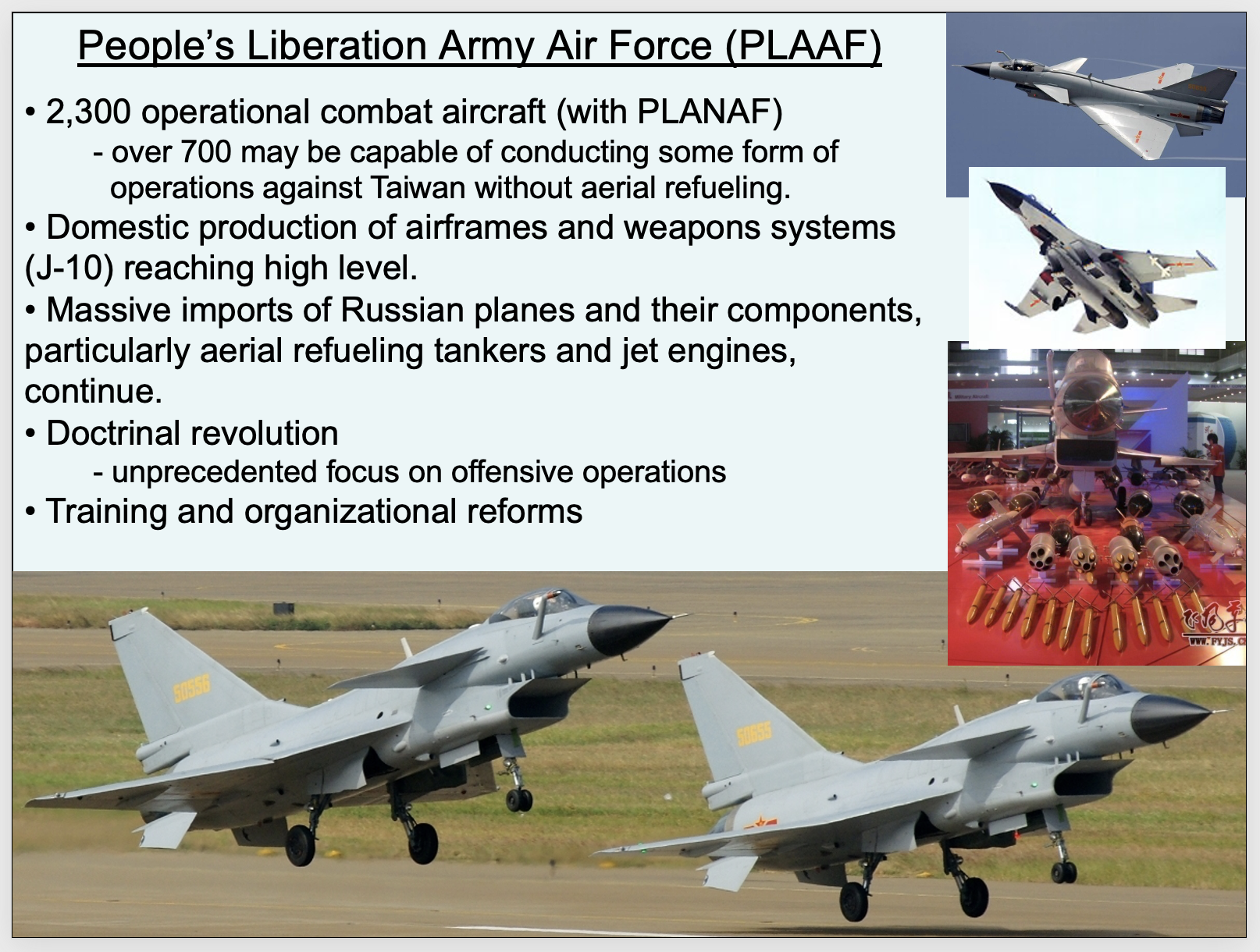

Number two, these capabilities are divided among China’s Second Artillery – that’s their version of the former Soviet Strategic Rocket Forces – Air Force, Navy, even the ground forces, to some extent, although I will not discuss them today for reasons of time. An interesting factor that we may see in the future is competition among these services for control of new forces, such as space forces that China may develop in the future.

Number three, China has carefully acquired technologies which target limitations in the physics of high technology warfare – physics-based limitations. These can place high-end competitors, potentially the U.S. Navy and other armed services, on the costly end of an asymmetric arms race.

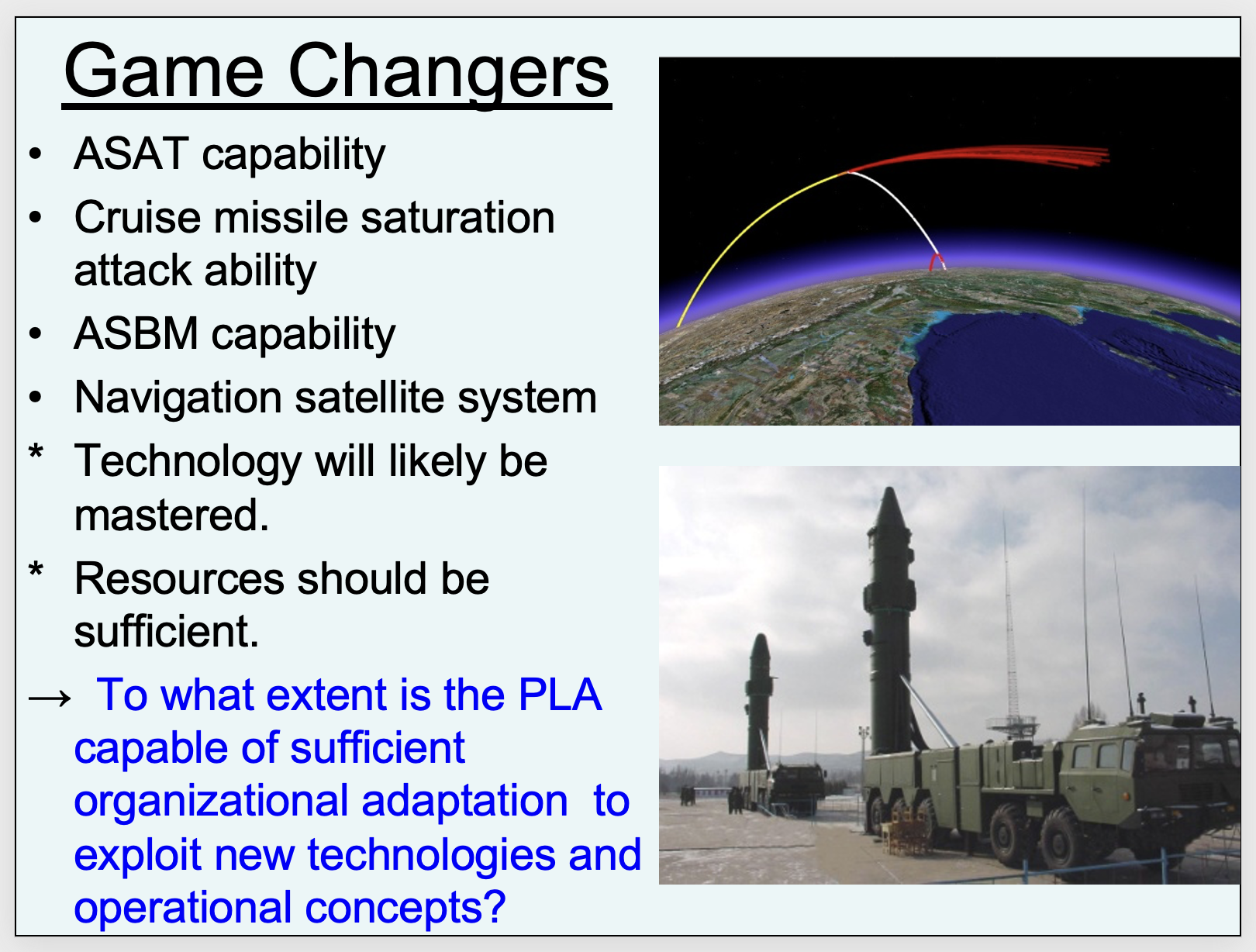

Number four, in addition to these widespread incremental improvements, China, I would argue, is on the verge of achieving several potentially game-changing breakthroughs, particularly anti-ship ballistic missiles, but I would also include in this definition: the capability to launch streaming cruise missile attacks, and anti-satellite attacks; and even the application of satellite navigation to leverage various military systems.

Number five, these achievements promise to radically improve the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s military’s access denial capabilities by allowing it to hold at risk a wide variety of surface and air-based assets, were they to enter strategically vital zones on China’s contested maritime periphery in the event of conflict. Next slide, please.

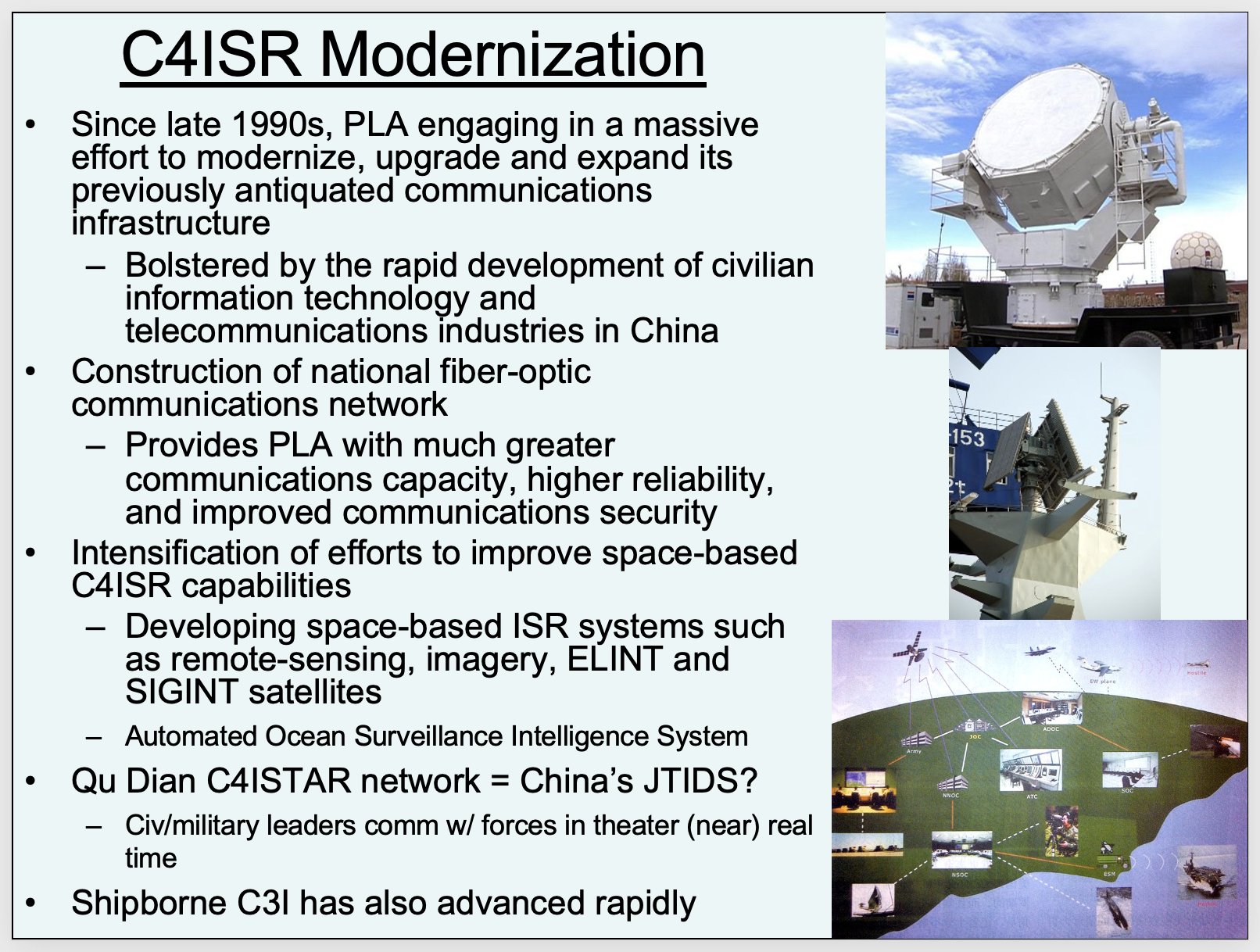

Number six, China does face some ongoing challenges in developing its military and we need to study those carefully, too. Areas I would highlight include human capital, realism of training, hardware and operational deficiencies, and C4ISR – that’s command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance – as well as some uncertainties on China’s part about the extent to which it can achieve some aspects of target de-confliction with existing systems and strategies.

Number seven, China has many ways to mitigate these limitations for kinetic operations around Taiwan or other areas of its maritime periphery and potentially for non-kinetic peacetime operations or phase-zero operations further afield. Number eight: I would argue, however, that conducting high-intensity wartime operations in contested environments beyond Taiwan at the present would tend to be a lot more challenging for China. And China, I think, would need to achieve major qualitative and quantitative improvements, particularly in aerospace, to progress in that area. That, in turn, would give China vulnerabilities, in some ways of the same sort that it’s able to target on the part of the U.S. right now.

And finally, point number nine, the biggest strategic question for U.S. Navy planners is whether and to what extent China will choose to develop the aerospace capabilities and other capabilities to support a major kinetic force projection far beyond Taiwan. I think it’s more uncertain where they’re headed in that regard. Next slide, please. … … …

I think this is a well-educated audience as to what’s at stake here. Clearly, America’s very robust position in the international system to a large extent hinges on its ability to command the global commons by dominating and exploiting the sea, air, and space for military purposes. This has been an argument by MIT scholar Barry Posen, for example. And as you see in the middle line here [points to slide], therefore, any major strategic area to which the U.S. could be denied access or its assets could be held at major risk, could start to undermine that.

That’s why a recent article by Andrew Krepinevich from CSBA in Foreign Affairs really caught my attention, because he said, “East Asian waters are slowly but truly becoming a potential no-go zone for U.S. ships, particularly aircraft carriers.” I’m quite concerned about that. Next slide, please. Now, we could have a semantic discussion and I don’t think that’s necessary for this audience about what exactly constitutes revolutionary versus evolutionary change in military capabilities. I’m going to argue that China is engaged in a revolutionary change in military capabilities.

If we use Krepinevich’s definition, this is when the application of new technologies into a significant number of military systems combines with innovative operational concepts and organizational adaptation in a way that fundamentally alters the character and conduct of conflict.” I think we’re facing nothing less than just such a challenge, at least in the East Asian theater context. And to bring in another great strategist, Eliot Cohen, this type of revolution is something that can change the appearance of combat. It can change the structure of armies. It can lead to the rise of new military elites and alter countries’ power positions.

So the point here is China can create tremendous challenges for the U.S. military, even if it never catches up in terms of overall capabilities as a peer competitor. I think that all too often, at least more in the academic realm, we get too wrapped around the axle and people say, China will never be an exact peer competitor or is not now. China doesn’t have this, China doesn’t have that. The point is that all kinds of capabilities could still combine to create a challenge, even without military parity. Next slide, please. I’ll skip this slide in the interest of time.

Here’s why I’m arguing that China is on the cusp of a military revolution. And I say the cusp because revolutions in military affairs only fully manifest themselves in actual warfare. I think history shows us that all too often there is a considerable surprise. And as the Secretary said, we cannot afford to be surprised in that regard.

Looking through Professor Cohen’s criteria that I just mentioned here, we can see that one criterion is: “a change in the appearance of combat.” I’m sorry this quotation from Secretary Gates in Foreign Affairs is not large enough for you to read, but what Secretary Gates said is that “Beijing’s investments in cyberwarfare, antisatellite warfare, antiaircraft and antiship weaponry, submarines, and ballistic missiles could threaten the United States’ primary means to project its power and help its allies in the Pacific: bases, air and sea assets, and the networks that support them.” To me, that’s changing the appearance of combat.

In terms of changing the structure of armies, I am here as a scholar: I’m not an operator, and I’m not a policymaker. I am not here to say what the U.S. military should do in the future. I’m just trying to raise ideas that I think all of us in this room need to consider seriously. One of the most serious challenges here is to what extent carrier strike groups can survive in their present form. Is there a need to make some adjustments to that? I’m just raising the question because I think it has to be asked and it has to be debated. Are there different types of U.S. force structures, perhaps supported with different types of U.S. capabilities, that the U.S. can deploy that would minimize some of these risks that are approaching us here?

In terms of new military elites, when we look at China’s military developing, we can see the potential for new organizations to be created, such as, perhaps, some sort of space forces in the future. In terms of altering a country’s power position, as I said before, the command of the global commons being very important for the U.S. Navy and for the U.S. military – working with its partners around the world, of course – in the spirt of the new U.S. maritime strategy, for instance. Next slide, please.

So let’s dive in a little deeper and look specifically at what I call Chinese “asymmetric” capabilities; again, “asymmetric” meaning those platforms that match Chinese strengths against U.S. weaknesses, not U.S. weaknesses for a lack of professionalism or a lack of hard work, but based on immutable laws of physics that are just inherently hard to deal with. In the naval dimension, I think submarines and sea mines are two major areas. Here I’m drawing on work done with colleagues at CMSI, including our Director, Dr. Lyle Goldstein, and Professor William Murray. Next slide, please.

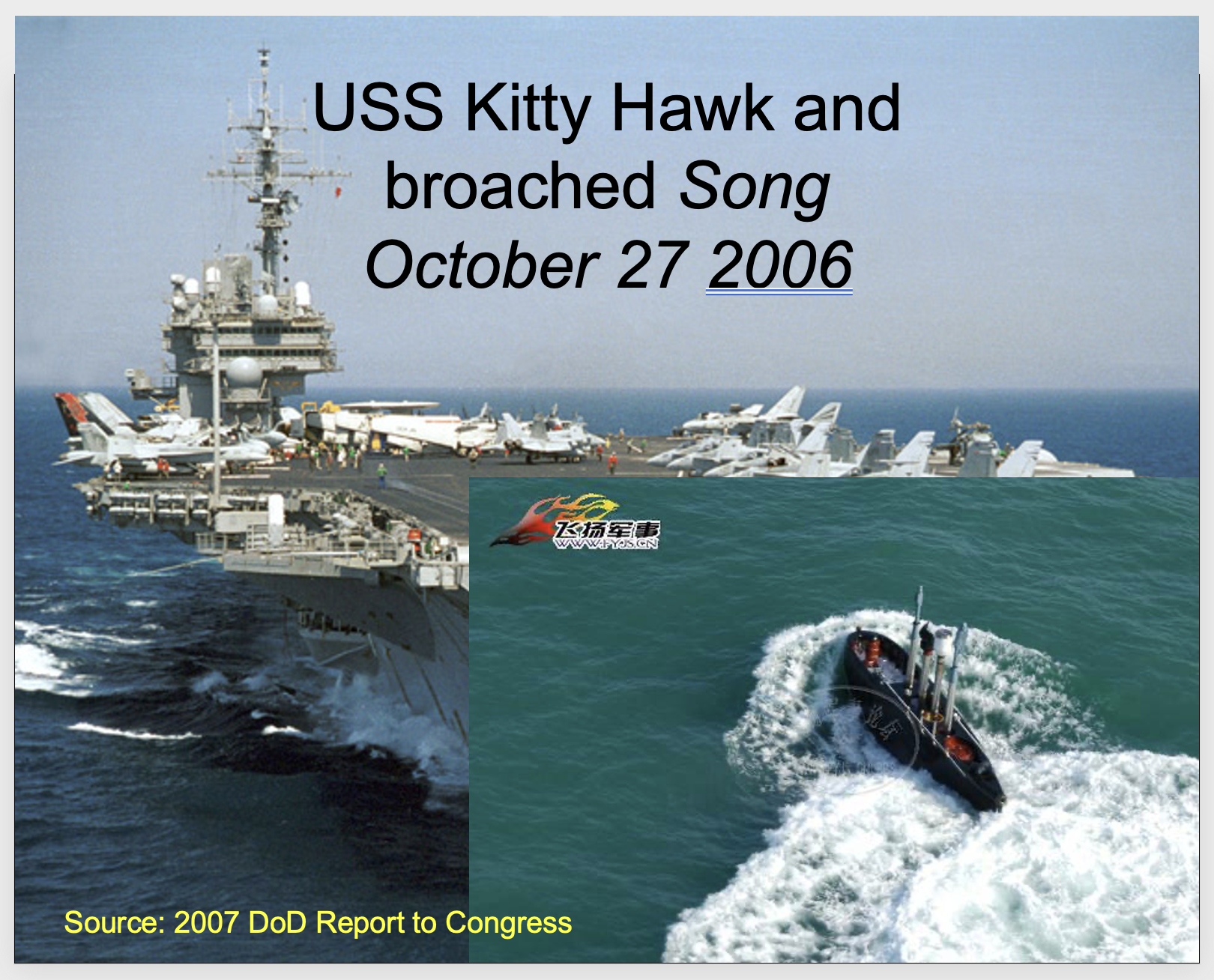

China’s indigenous Song-class submarines, for example, contain a mix of foreign systems that have been substantially improved over time. Next slide, please. According to various media reports, in 2006, and also according to the 2007 Department of Defense report, a Song-class diesel powered submarine broached in close proximity to USS Kitty Hawk. Now, in my personal opinion, this indicates the potential that China figured out where the Kitty Hawk would be and sent its submarine to see what it could learn.

I think that’s of concern and the fact that the submarine operated this closely to the Kitty Hawk raises the troubling possibility, although it doesn’t prove it, that diesel submarines are extremely hard to detect and that the People’s Liberation Army and Navy, in some situations at least, could get within close range to U.S. ships. This is of concern because China’s submarines can deliver devastating weapons, including anti-ship cruise missiles, torpedoes, and mines potentially directed at the only U.S. forces that could quickly aid Taiwan in the event of a PRC military coercion. Next slide, please.

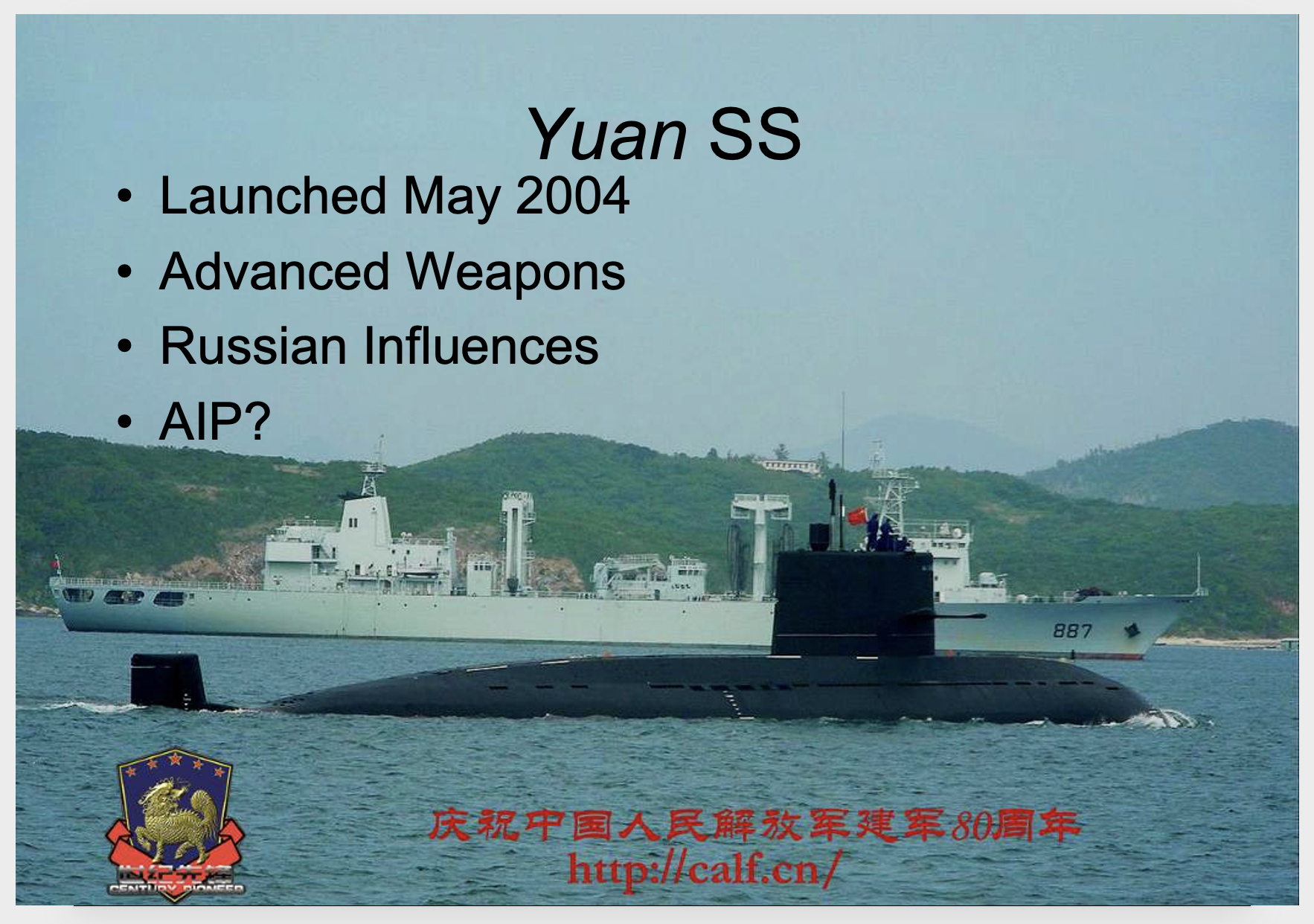

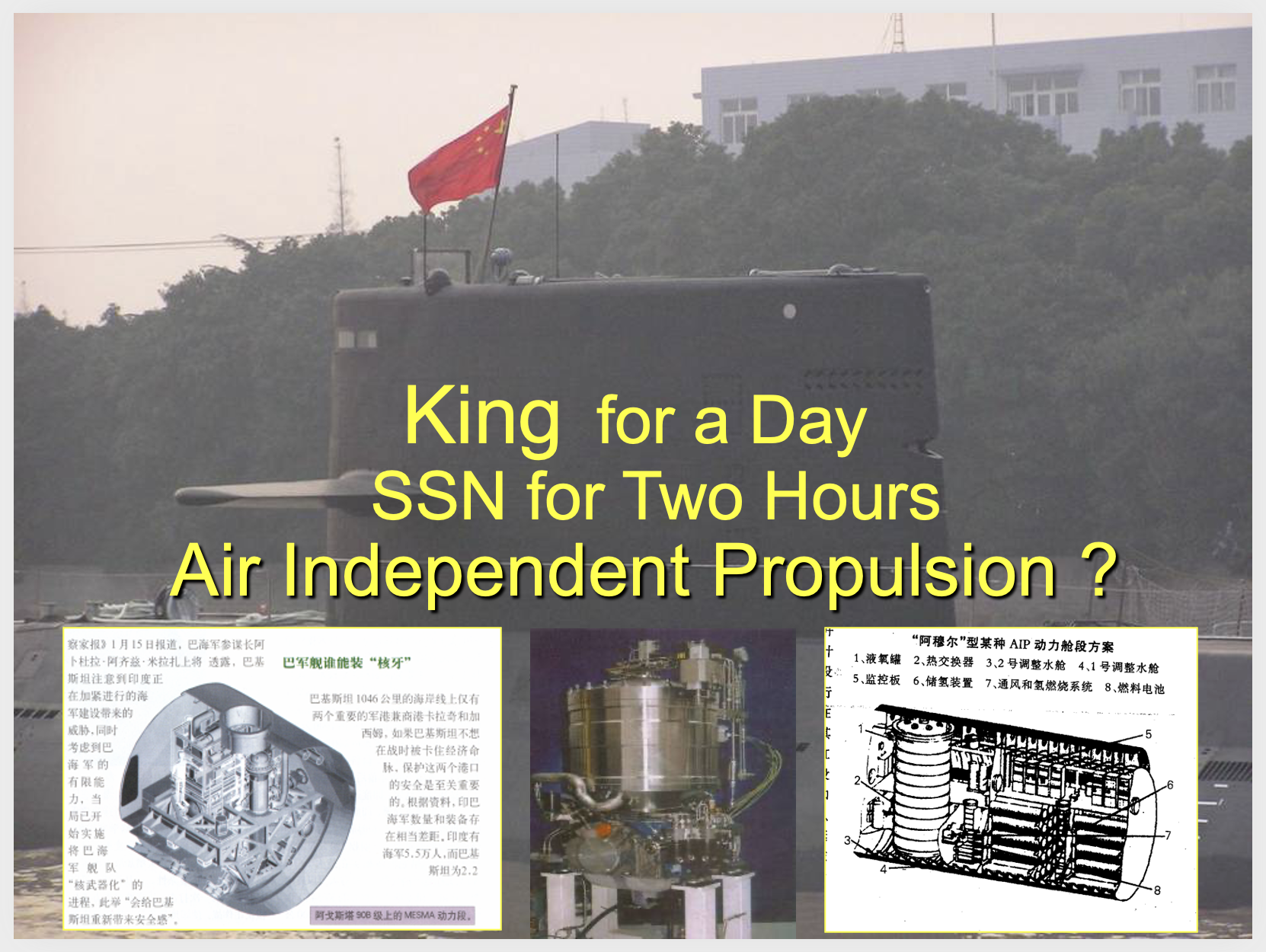

Now, China is modernizing a variety of different types of submarines, including its indigenous Yuan-class diesel-electric submarine, which appears to incorporate both Russian design elements and Chinese characteristics. There’s speculation as to whether it has air-independent propulsion – I have seen no conclusive proof on that. But, what does this air-independent propulsion (AIP) mean? Why should we care about it? Next slide, please. Please click again.

The key here is air-independent propulsion gives the commander of the submarine a choice. It can become, in effect, a nuclear-powered submarine for two hours in terms of propulsion and evasion power. Or it can – please click again – cruise quietly at around three knots without snorkeling for two to three weeks, giving great stealth capabilities. Next slide, please. Please click twice. Perfect.

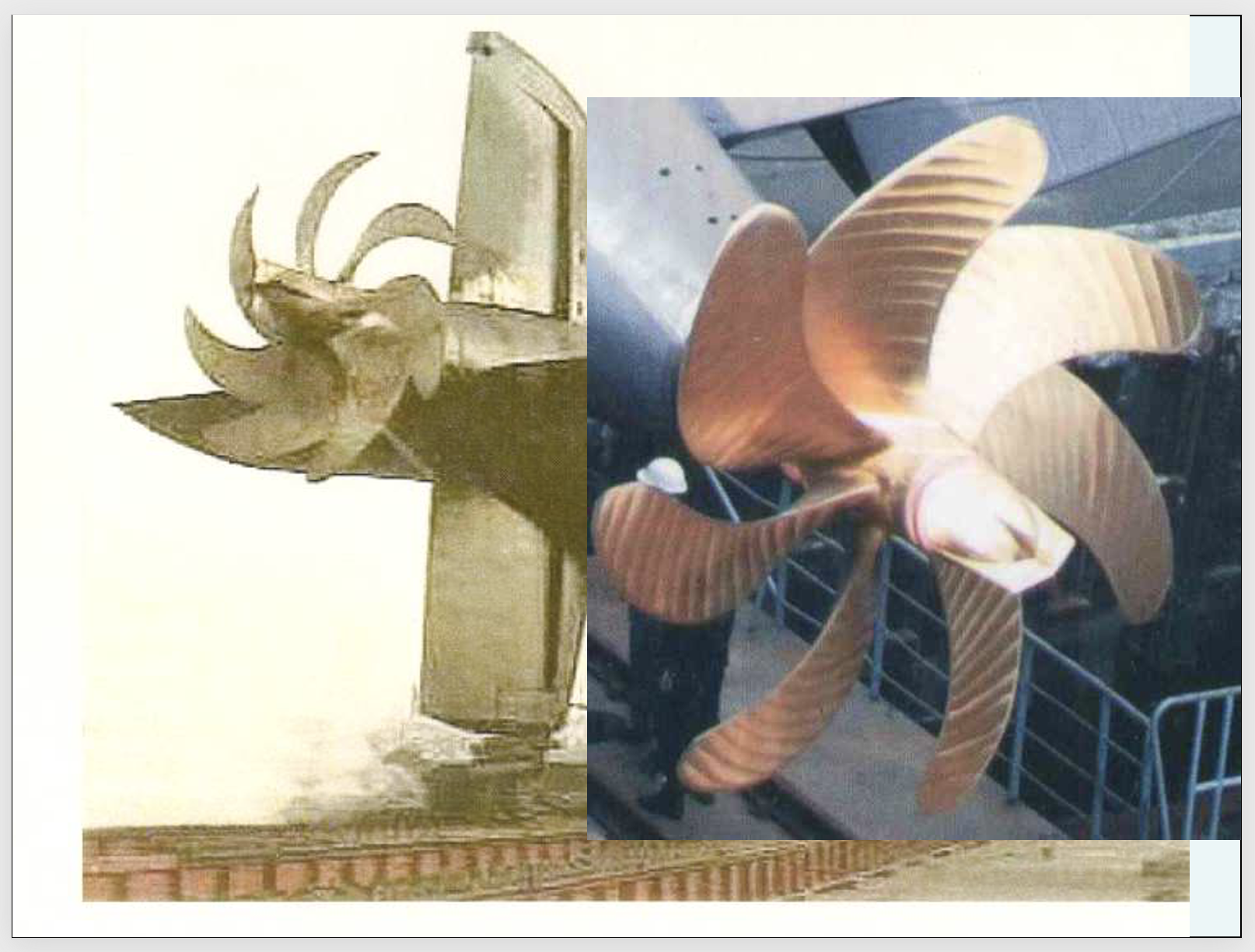

China also has 12 Kilo-class submarines that it’s purchased from Russia. The newest eight include more modern sonar or more quiet engines, as well as more modern fire control systems, which allow the vessels to shoot the formidable Klub anti-ship cruise missile. And as you can see right here, in a picture of Hull 50, these submarines appear to have rather sophisticated propellers. Next slide, please. And now click again.

What’s interesting here, is that on the left we have Song Hull 1 from 1994. On the right, we have the screw of a Kilo built and sold to China in 1996. To my eye and those of some of my colleagues at least, these are strikingly similar screws, both having cruciform vortex dissipators, potentially an advanced quieting technology. So to me, the larger point that you should take away from here is that less than three years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, China was acquiring very sophisticated submarine technology from Russia, which has also supplied China with cruise missiles, torpedoes, sea mines, and who knows what else. Next slide, please.

This is a photo of China’s new Shang-class SSN, pictured – please click again – in the middle here. There has been an unclassified statement from the Office of Naval Intelligence that only two of these nuclear-powered submarines will be built. And given the fact that China has already constructed a base on Hainan Island that appears to be capable of supporting quite a number of submarines, this to me would be would lend credence to the idea that after this version, there may be a follow-ons, including a so-called alleged 095 project.

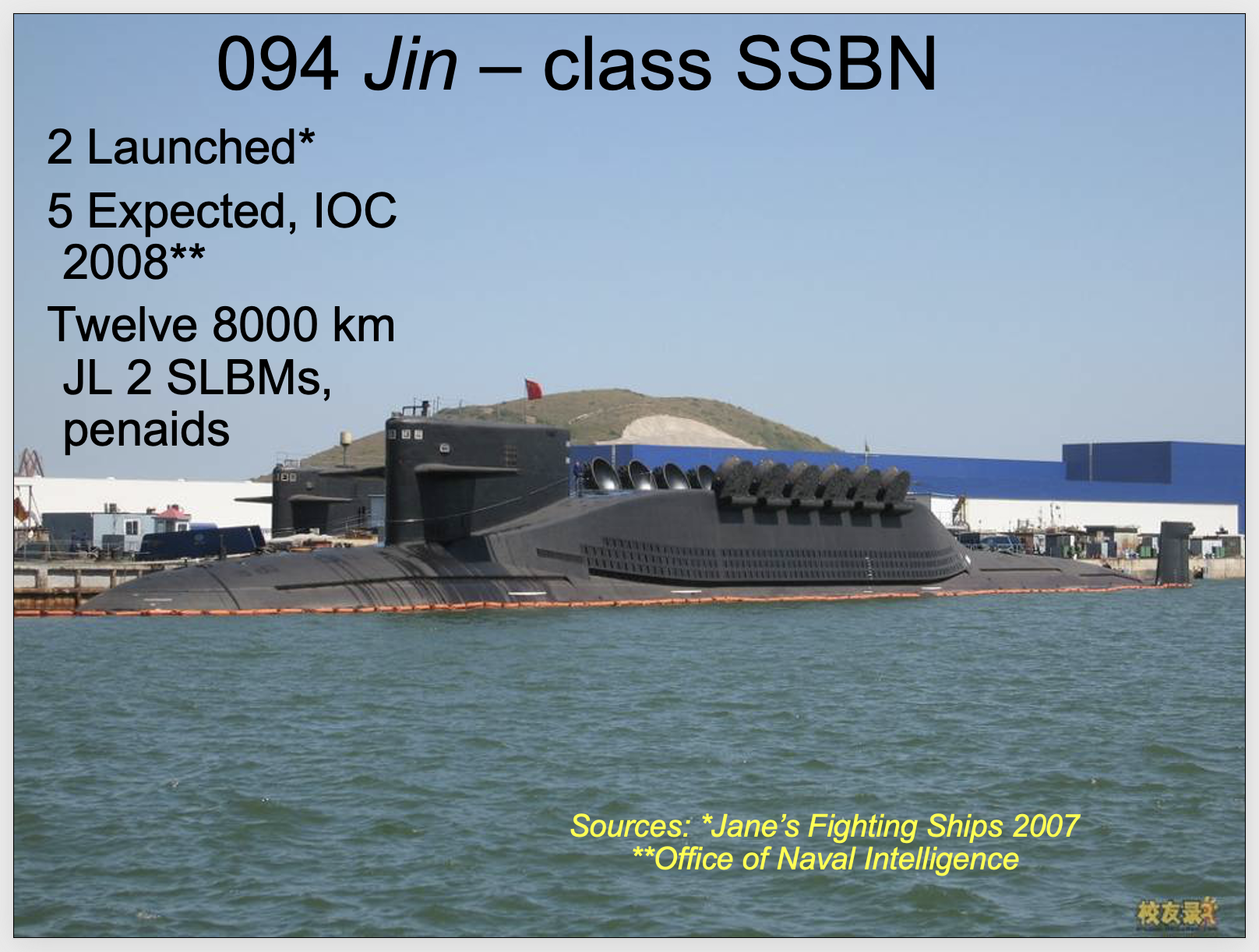

And it’s hard to know at the unclassified level how quiet these submarines are, but we can expect that they would continue to get quieter over time. Next slide, please. In terms of the strategic component here, China’s new SSBN ballistic missile submarine, the 094, has been forecasted by ONI to have five hulls in the future. Next slide, please.

I think this picture’s interesting. I bring it to your attention because it shows what potentially could be a typical load-out of anti-ship cruise missiles, six of them, and torpedoes, two of them, on a Song-class submarine. If this is indeed the case, it seems to be a real emphasis on using anti-ship cruise missiles, potentially for some type of streaming attack. Next slide, please.

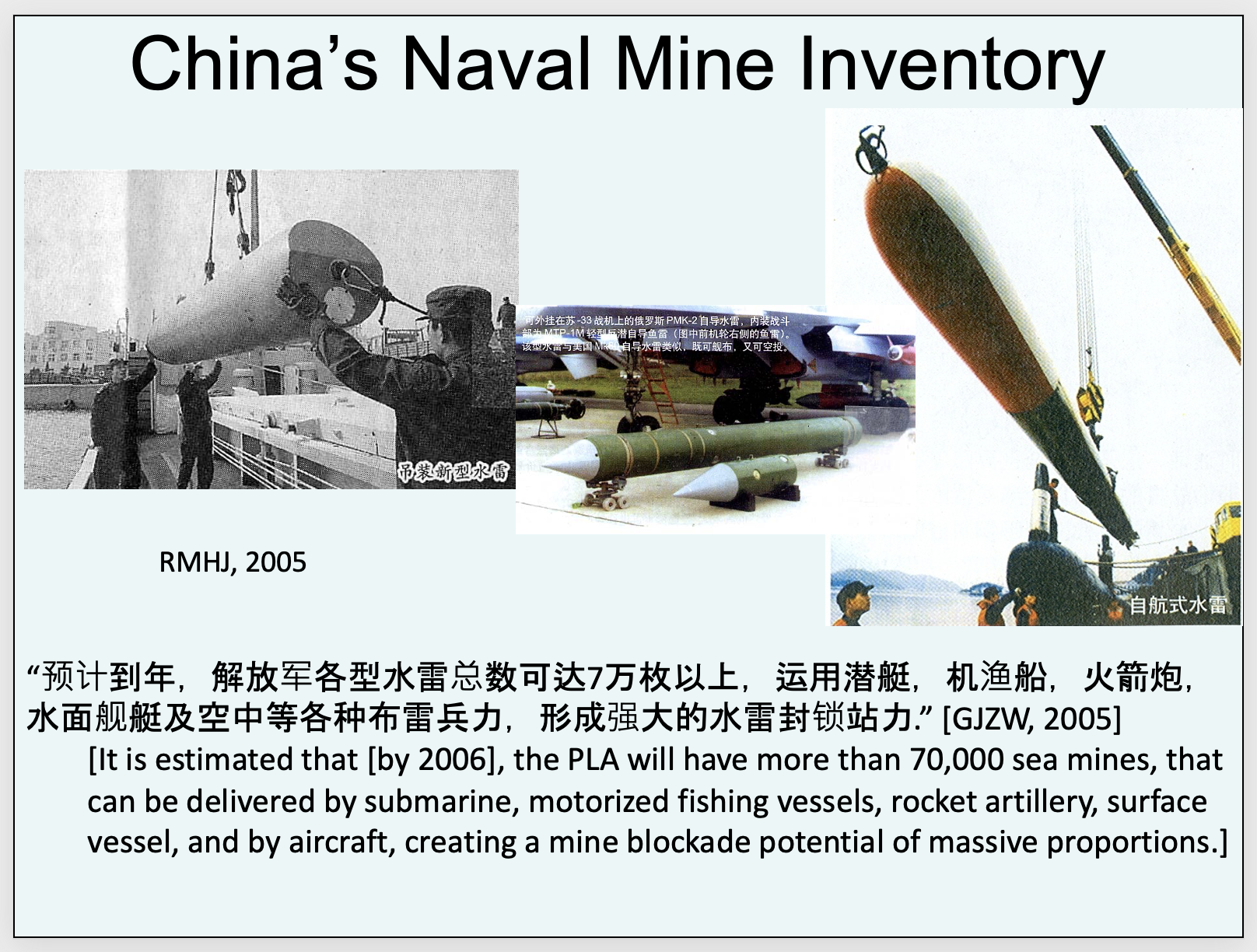

Moving on to naval mine warfare, various sources state that China has between 50,000 and 100,000 sea mines. That’s a large inventory. Next slide, please. Also, if you read the Chinese technical literature, as I do, and know Paul Giarra does and I hope some other people here do, it’s just staggering. Thousands of Chinese technical articles and multiple research institutes – a lot of work is underway to make Chinese capabilities more robust.

One thing I’d call to your attention here is the phrase – (“zhi neng hua,” in Chinese) – or what the Chinese call “intelligizing” the sea mines. This is upgrading the fusing systems in a retrofit akin to the addition of a JDAM Tail Kit, which preserves the operational relevance, potentially, of many of China’s huge inventory of otherwise obsolescent sea mines.

In terms of these highlighted blue phrases down here, on the top right, we can see a picture from a Chinese naval encyclopedia depicting a notional and exotic anti-helicopter sea mine. There’s no proof that China has such a weapon at present, but Chinese experts are clearly looking at the cutting edge. Don’t want to mislead anyone with this quote at the bottom [of the slide] on nuclear-armed sea mines; but we have, in multiple sources – including the PLA navy-published journal Modern Navy – seen discussion of how such weapons could be advantageous to have. Next slide, please.

This is, to the best of my knowledge, a load-out on a Song-class submarine of the PMK-2, a very advanced rocket-rising sea mine that China has acquired from Russia. I think it’s pretty significant that China could have something this advanced and is training and practicing with it. Next slide, please. Also, China holds exercises that involve the Maritime Militia – with civilian fishing vessels – training in the laying of mines; GPS could leverage that considerably. Next slide please.

This is a first cut at a concept of operations for mine warfare, based on phrases that come up again and again in Chinese writings on sea mines. We’ve looked at over 1,000 articles. How do you use naval mines? What are they good for? I don’t have time so I’m just going to unpack one of the terms here: “undersea sentry.” The Chinese sources say repeatedly that the Soviets developed sea mines to use against U.S. nuclear submarines. That’s a good idea, the Chinese sources say; that’s what we’re doing now, too. This is the poor man’s anti-submarine warfare that China may have difficulty doing in other ways. Next slide, please.

Just putting in some depth curves here, in 200 meters of water and shallower – that’s where the majority – and you can put through the next one, too – of sea mines can be laid. But in these deeper waters, China’s rocket-rising – next slide, please – sea mines as well as its alleged drifting sea mines could be used as well. So there are many different angles from which to approach that. Next slide, please.

Now, as I said before, China is developing four potential game-changing capabilities: anti-satellite capabilities, with some form demonstrated on 11 January 2007 – multiple programs reported ongoing, including laser-type programs; cruise missile saturation attack capability – the component capabilities for this are under development; a navigation satellite system, which could offer reliable access to signals in wartime; and finally, I’ll speak a little bit about China’s potentially developing anti-ship ballistic missile capability based on the DF-21 or CSS-5 missile, arguably pictured right there.

With all of these systems I just mentioned, by the way, I think China has the technology and capabilities to get there in developing it. I think the challenges it may face may be in the organizational and conceptual areas about how it actually uses such systems, puts them in the order of battle. That may be more complex.

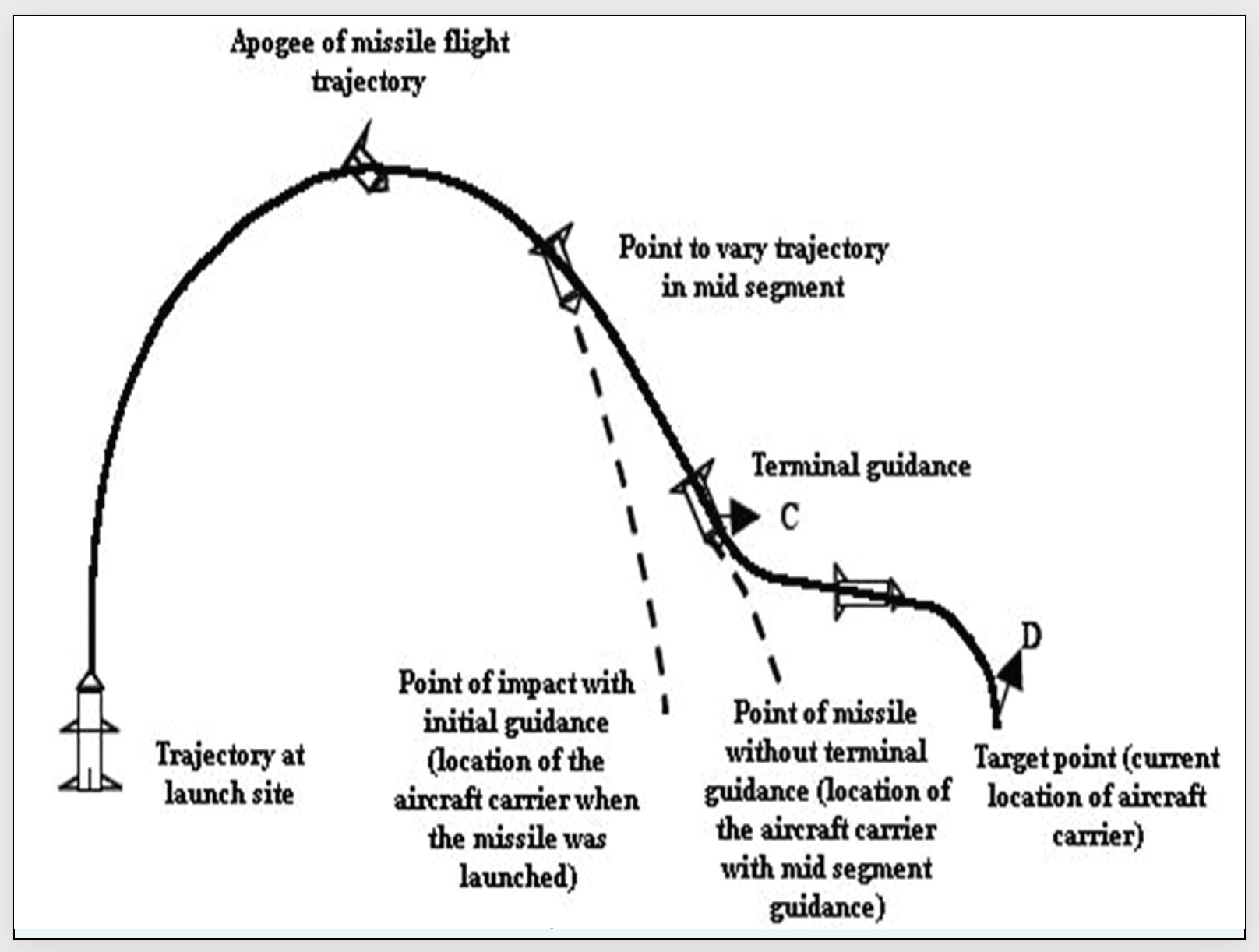

Many of you recognize this diagram from the 2009 Department of Defense report. You can also trace it back to a specific Chinese source which I quote in some of the literature that’s been distributed to the group. I’ve published a couple of articles on Chinese anti-ship ballistic missile development. What I hope you would note in this trajectory diagram here is the midcourse and the terminal guidance aspects, and the depiction of second-stage control fins, which would be critical to steering the anti-ship ballistic missile through terminal maneuvers.

I know many in this room are familiar with this concept. If anyone isn’t, I would argue in a very rough sense that this makes an ASBM different from most ballistic missiles you’re familiar, with which have a fixed trajectory. In some ways, this is more like an advanced cruise missile in that terminal maneuvers to evade countermeasures and to home in on a moving target are possible. And I know that in September, you can look forward to a very detailed discussion from Paul Giarra on this subject. Next slide, please.

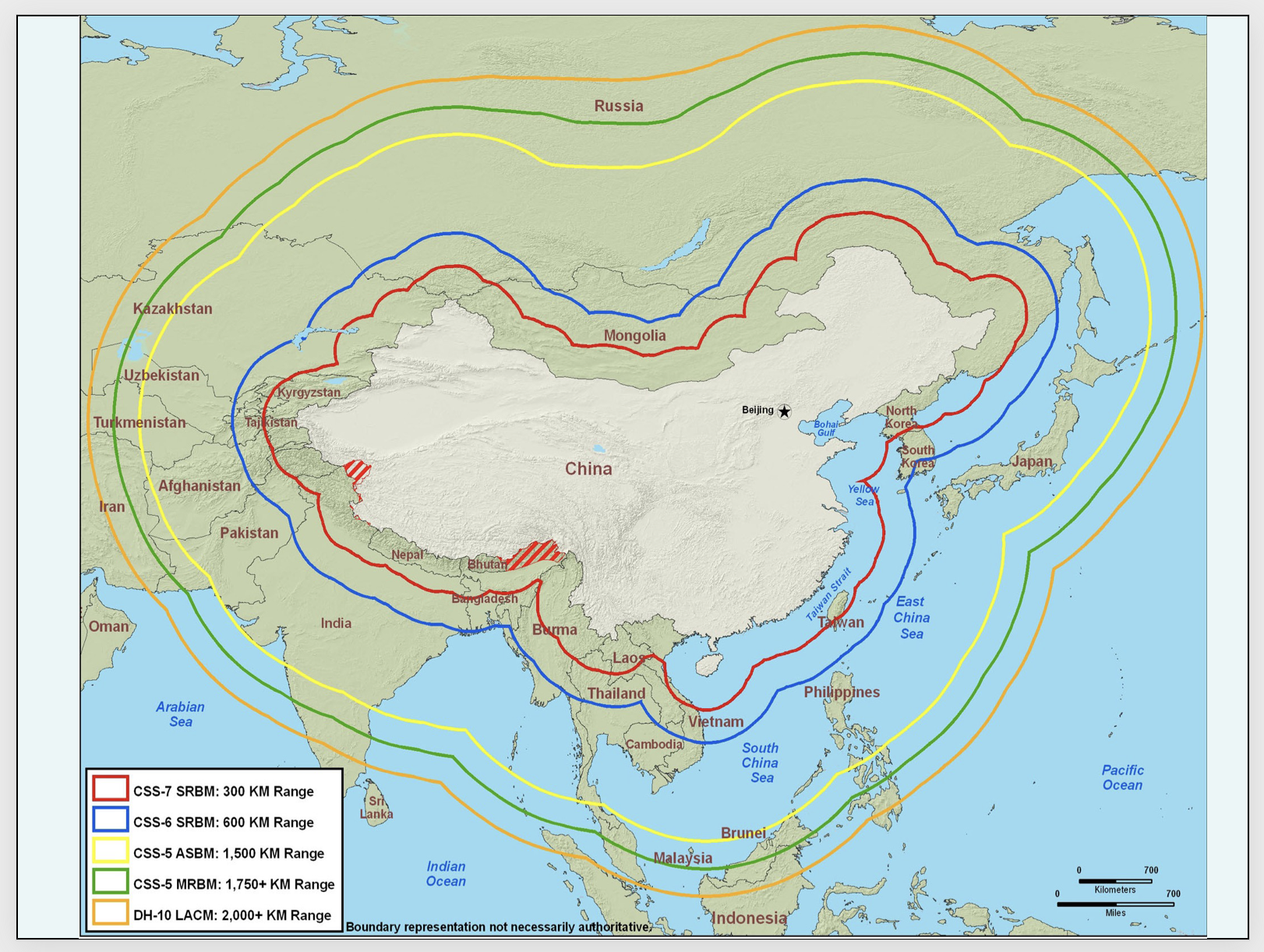

I wanted to throw in some range rings from the DoD report because I think this is where it really hits home. In the 2009 report, we had this chart, with this yellow line here showing the projected range of a CSS-5, DF-21-based anti-ship ballistic missile – a 1,500 kilometer-plus range, which represents the potential to hold ships at risk in a very large maritime area, far beyond Taiwan. I think this is a potential challenge that we really have to take very seriously. Next slide, please.

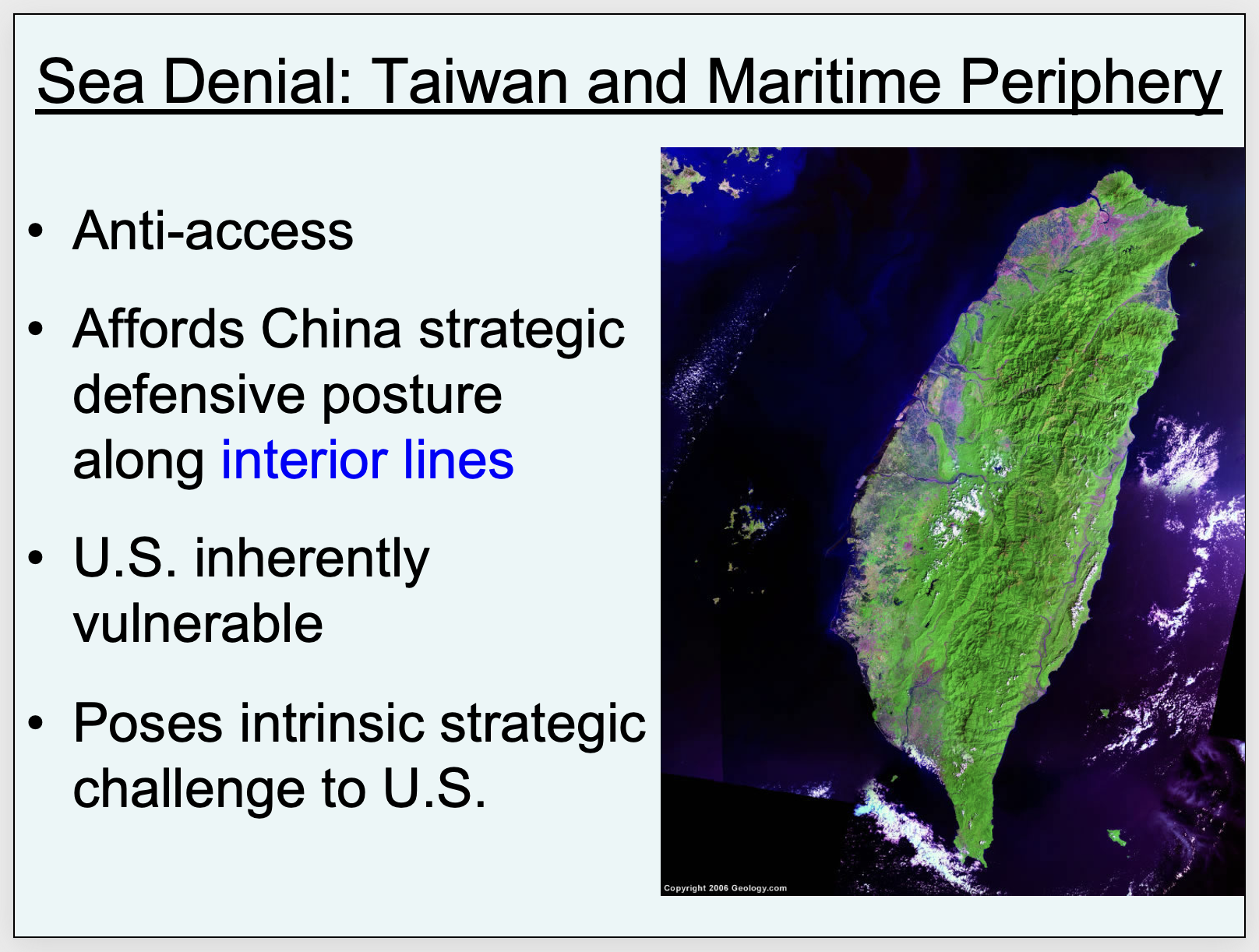

So to sum up the anti-access issue, particularly on China’s maritime periphery, I think this is largely about a potential Taiwan scenario for China, the ability to use some military coercion vis-à-vis Taiwan. Precision strikes can destroy regional bases in both Taiwan and in other places – in places outside of Taiwan where the U.S. has bases such as Japan. Cruise and perhaps ballistic missiles, as time goes on, can target U.S. carrier strike groups. This approach has significant advantages. It affords China a strategic defensive posture along interior lines.

As I’ve said before, China need not keep pace with the U.S. technologically to take advantage of this. It is a red herring to say that China has to match the U.S. exactly technologically before it could pose a challenge in these areas. That’s the whole concept of an asymmetric challenge. So under that concept, incremental developments may have disproportionate impact.

This is very difficult, I think, for the U.S. because it targets inherent vulnerabilities. The U.S. operates offensively on exterior lines, thereby creating a vulnerability, and must struggle to maintain technological superiority to reduce this vulnerability. And as I said before, this poses an intrinsic strategic challenge by potentially denying the U.S. access to portions of the global commons and the freedom of action therein. Next slide, please.

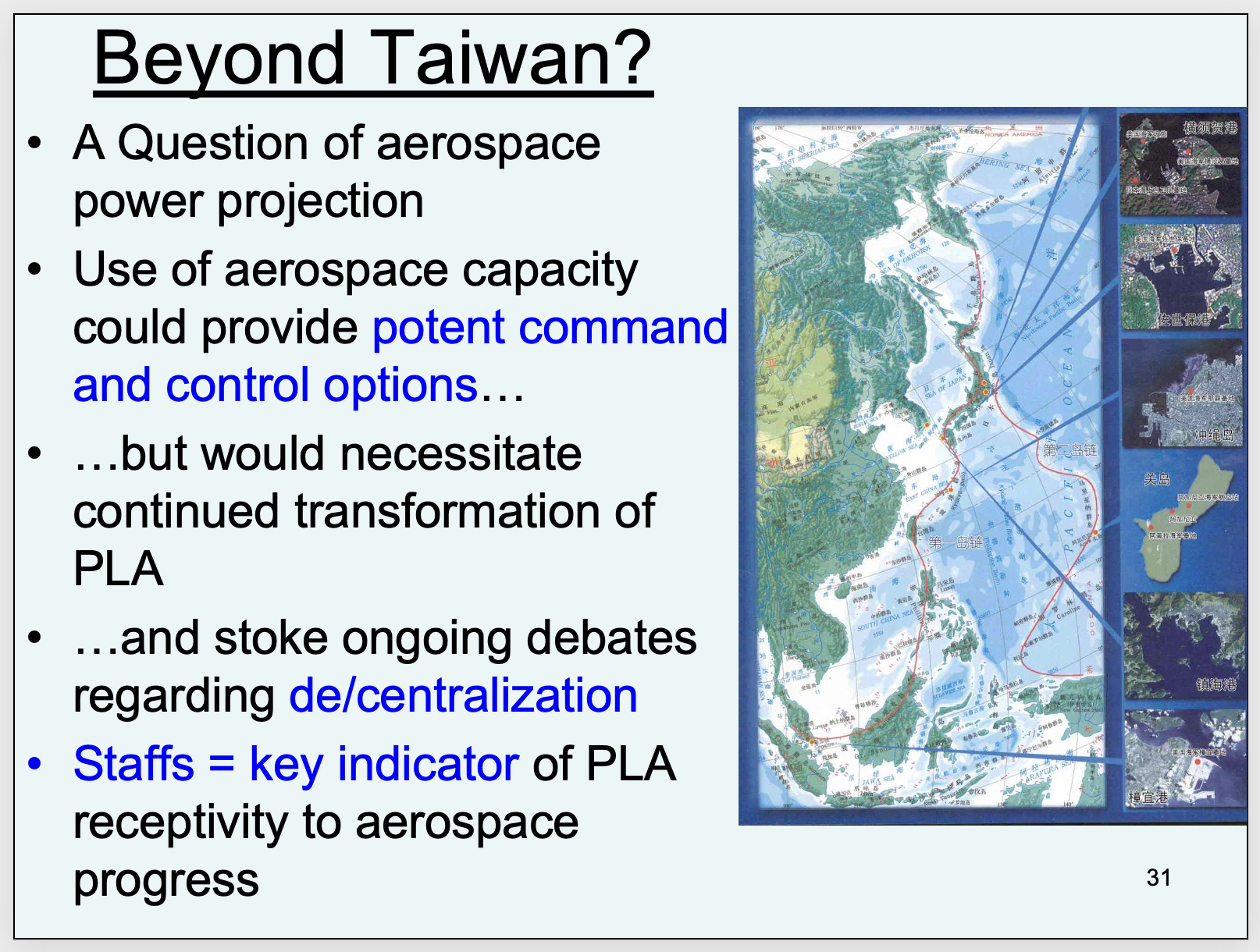

I do want to acknowledge some potential challenges for China in the future, though. I think that beyond Taiwan, things start to get far more complicated. It’s true that the use of aerospace capability could provide potent command and control options. It could give China additional information and decision-making capacity regarding how to use force at the strategic level, more flexible deterrent options, and the ability to fine tune operations.

But a lot of this, I would submit to you, hinges on continued transformation of the PLA, which currently lacks sufficient relevant assets and properly trained personnel to credibly execute necessary ocean surveillance and long-range slot defense missions. I think they’re working on that to some extent, but compared to these very robust anti-access capabilities, I think it’s in a completely different category.

Finally, China has yet to reform fundamentally its government decision-making system, which is particularly unsuited to handling crisis situations. I think we can see this in aspects of their military organization as well, wherein they already have debates regarding the respective merits of centralization and decentralization. I think we’re going to see a lot more, even some echoes of some old Soviet debates, although with new “Chinese characteristics,” as they say.

This raises compelling questions about whether or not the PLA will overcome its centralized, hierarchical command structure and organizational culture to delegate real-time decision-making down to the lower levels or whether it will attempt to leverage new ISR capabilities and growing communications capacity to further strengthen centralized command and control at the higher echelons. I think that’s a definite temptation for them based on their organizational culture.

So the key is look at the staffs. Those are going to be an important indicator of PLA receptivity to technological progress in these areas. Do these staffs remain largely functionaries, or are they capable thinkers with professional expertise who are integrated efficiently and can develop holistic plans for integrated force operations like staffs we have in the U.S. military? Next slide, please.

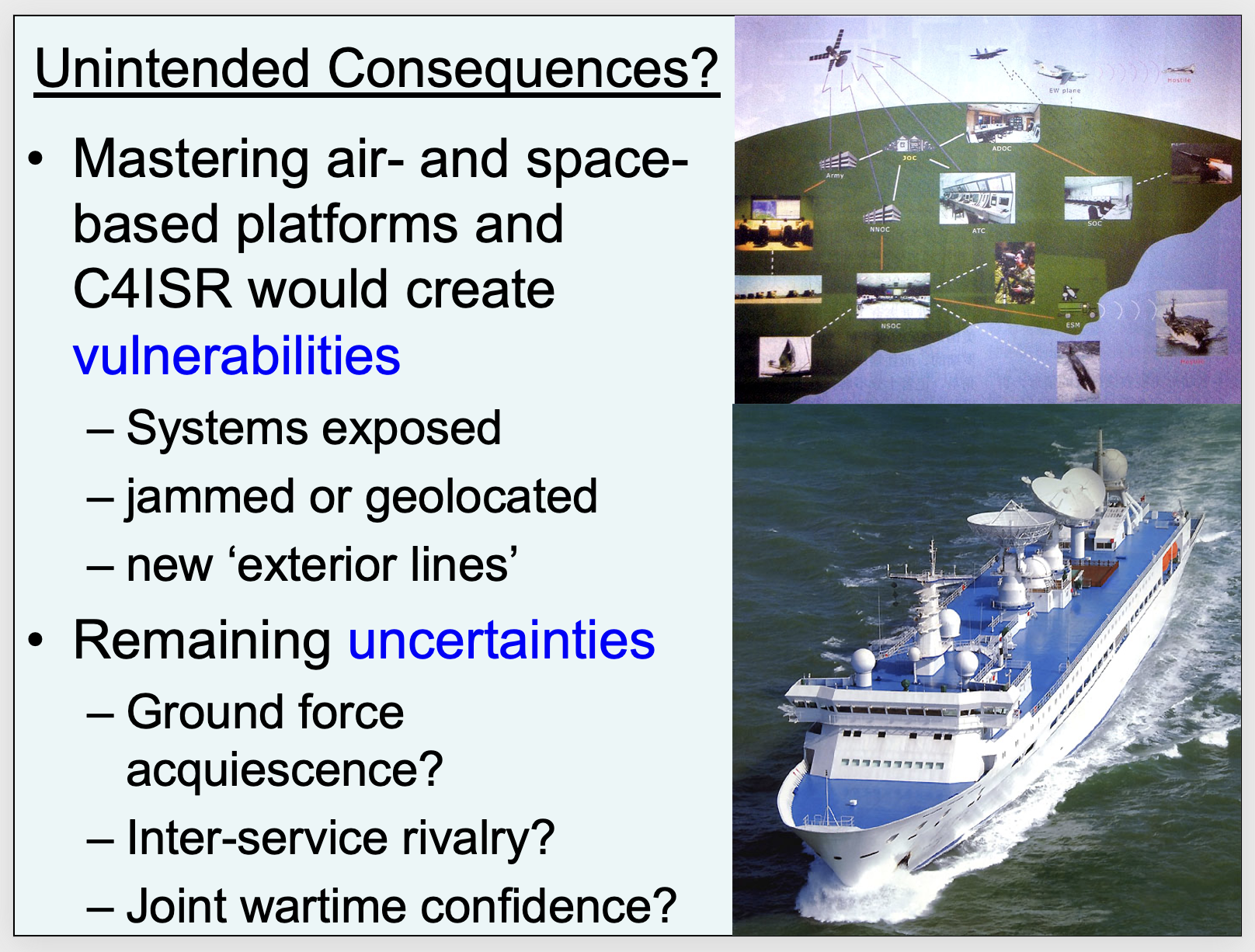

And as I said before, mastering these capabilities, and moving further and further beyond China’s immediate maritime periphery, will create vulnerabilities, I think, for China. As it masters the air and the space-based platforms and the C4ISR, these systems will become more vulnerable to electronic computer network and kinetic attacks. Satellite communications and long-range signals may be jammed or geo-located. In essence, the PLA will acquire its own exterior lines.

So what are some remaining uncertainties here? Will the PLA ground forces acquiesce to the increasing role of the Air Force, the Second Artillery and the Navy, particularly in joint operations? You may see some friction there, particularly as the services maneuver for control of different programs, as I said before. And how good will the PLA get at jointness? They’re working hard on it, but probably they still have some way to go. Next slide, please.

Bringing this all together, though, what are the larger implications? What are the larger takeaways? I would submit to you that it seems clear that the U.S. may face a strong competitor with the ability to contend in all aspects of comprehensive national power, particularly in these asymmetric areas, and at a time when Washington is committed geostrategically in the Middle East and Southwest Asia and faces increasing budgetary challenges at home. So I think it’s a time where we have to be especially vigilant regarding these issues.

I think the focus of much of this potential competition will be East Asia. That’s where a lot of China’s interests are, where Beijing desires a preeminent position. And I would argue, in particular, something we need to pay attention to is that China seems to be focused on developing capabilities like sea mines, for example, which don’t provoke direct military confrontation, yet over time make it increasingly costly for Washington to intervene militarily in the event of a Taiwan crisis – a sort of creeping capability approach.

So questions we need to ask ourselves here are: what would be the consequences for the U.S. role in East Asia, and what should be done to preserve or shape that? Next slide, please. I think I’ve said this in a variety of ways, but in case someone would like me to state it in a different way, I call your attention back to this wonderful article by Andrew Krepinevich. And the bottom line here – I’ll let you read the quotation yourself, but the U.S. cannot afford to be complacent about Chinese anti-access capabilities. I think we have to assume that they could be extremely significant and develop even more broadly and quickly in the future. Next slide, please.

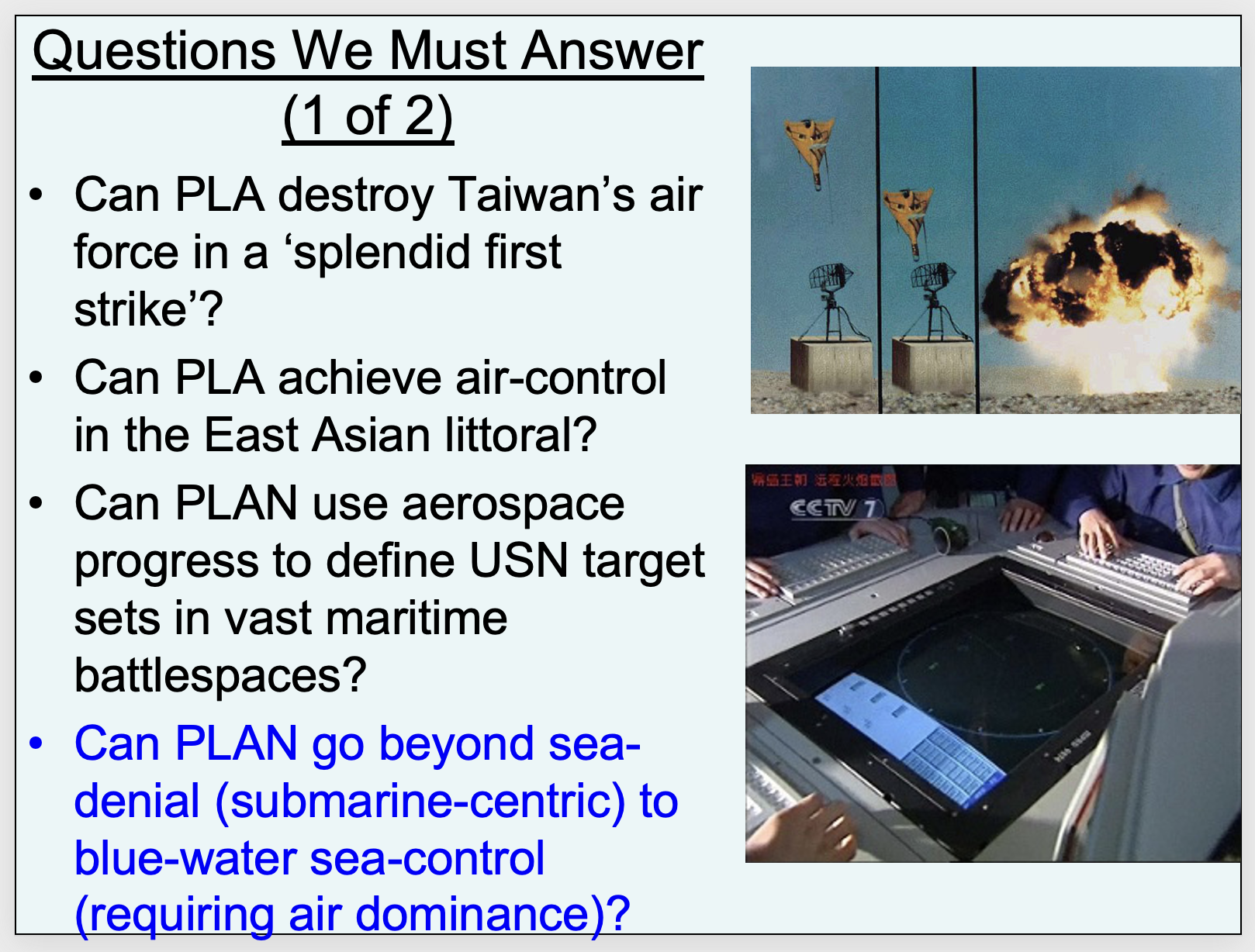

I want to leave a few questions with you that we’re still trying to research at the China Maritime Studies Institute. I can’t pretend to give you complete answers to these today, but I think it’s incumbent upon all of us to keep these in mind and keep an eye on the situation. The most fundamental question to me is whether over time the PLA will be able to master the developments in aerospace platforms and C4ISR necessary to support a true blue-water sea-control capacity moving significantly further out than the immediate maritime periphery in East Asia.

So I had one more slide of questions, and then please click to this final slide. I’m happy to take any questions. And I’m sorry the time is so short here. I can certainly stay after this presentation and talk with anybody as long as they want. I have my contact information available. We can do it over e-mail, the phone. Thank you all very much for your time. I really appreciate it. (Applause.)

AMB. MIDDENDORF: There will be questions now.

DR. ERICKSON: Shall I take them or do you want to take them?

AMB. MIDDENDORF: No. You take them.

DR. ERICKSON: All right. Let’s fire away. Admiral?

ADM. SHUFORD: Just to get the ball rolling. You’re talking here about the problem of our strategy and our force structure when we employ it right now, putting us on the wrong end of the strategic equation –

DR. ERICKSON: Yes.

ADM. SHUFORD: – because we use exterior lines of communications, we have to move forward. You’ve given us a discussion about how, increasingly, those elements at the forward end of our exterior lines of communications are vulnerable. And just to make sure we’ve got the same picture here, those are, relatively speaking, the least vulnerable elements of our force structure; in other words, mobile, relatively stealthy naval platforms are not nearly so vulnerable as fixed-place airstrips and anything that would actually make a footprint on the ground. Okay.

So given all of this, do you see writing in the work that we’re doing up at the CMSI, do you see a lot of open-source discussion about this issue strategically, per se? And – second question – if you do, are the Chinese connecting the dots and questioning whether or not they want to put themselves in the same position downrange, in the exterior lines of communication; in other words, reverse the role? Do they see that as a potential strategic misstep on their part?

DR. ERICKSON: Absolutely. Admiral – thank you for pulling this all together in a nice summation there. Everything that I’m telling to you and the rest of the group today, my colleagues and I have derived from looking at Chinese-language open sources. This is what the Chinese themselves are saying, to grossly oversimplify.

Now, we document very carefully where we get the information and there’s a hierarchy of authoritativeness of the sources and the credibility of the sources and we don’t pretend that they’re all the same and blur them all together. But there’s a major pattern in which, out of necessity, in the past, and now increasingly out of capability, China is attempting to achieve its strategic objectives by targeting vulnerabilities that emerge inherently when the U.S. projects its forces in that way. It’s not anything we’re doing wrong per se. It’s the physics that come with it.

Chinese analysts in general, and I think there’s a debate ongoing here, are quite aware that as China moves forward, becomes a bit more like the U.S. militarily – although it still has a very long way to go in some respects – vulnerabilities will open up correspondingly. And this is a perfect time to bring in the concept of a Chinese aircraft carrier program, which I’ve gone through this whole presentation without even talking about because I think compared to these anti-access weapons, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, sea mines and some of China’s other naval capabilities, an aircraft carrier on China’s part is not what we should be worrying about. That’s on the other side of the spectrum. That’s on the side of vulnerabilities.

People have argued that movement in the direction of aircraft carrier development shows a certain strategic intent and an assertion of Chinese interest. That may well be the case. But it will take China, in my estimation, years to master the complex system of systems of air power that is an aircraft carrier. And indeed, in the Chinese strategic debate, you see a lot of people saying, well, why do we really need to push for this aircraft carrier? People go back to the era of Khrushchev, the mid-Cold War.

They quote with approval Khrushchev and other Soviet thinkers saying that missiles are going to determine everything and surface vessels are completely vulnerable. To sum this all up, there’s even a Chinese term that you see again and again and again, which basically translates to “aircraft carrier coffin theory.” So absolutely, Admiral. Yes, that comes up a lot. They are clearly thinking about it. Sir?

Q: I was struck by the lack of any discussion about cyber capabilities and combat factors in as a basic metric rather than pullout. And we talk about Chinese strengths against U.S. weaknesses and I don’t necessarily need a fighter aircraft or ASBMs if I can shut down the command and control system or basically deny access by basically keeping us on the ground. So I was wondering if you have any thoughts about how this factors into the discussions about capabilities and – (inaudible, off mike)?

DR. ERICKSON: I think you’ve raised a tremendously important issue. Unfortunately, this is not an issue with which I am familiar. I would submit that, in general, it’s a difficult issue to research using open sources, but I know there are people who do it and they do it well – I’m sure you’ve read work by James Mulvenon of CIRA, for example. He’s done some great work on that.

In some ways, this could be one of the ultimate asymmetric capabilities. I should have devoted more attention to it but I don’t have details to give on it. I think what ought to be considered by people who know a lot more about this than I do is the possibility that this is the one capability where asymmetric actions occur even in peacetime – and it’s ongoing, and creating different types of challenges. What is the U.S. response to that? I don’t know. So people need to be thinking about that. Thank you for that excellent point. Please, in the back.

Q: Okay. So China’s economy has obviously been growing immensely and therefore, it’s only ordinary that they would try to develop capabilities to match that of the United States, but obviously, they can’t, so they’ve resorted to an asymmetric buildup. But at the same time, it is critical the U.S. develop a strategic partnership with China. But, as you mentioned earlier in that quote, it’s prohibitively expensive if we do not realize this challenge.

Would you say that China – if you were to address this challenge – I feel like this is an area where there’s a lot of things that we could do that China would perceive as threatening and it might be more disadvantageous to us if we were to build up to match China’s buildup – see what I mean? Do you see a balance that the United States could strike that we would not be perceived a threat China and, vice versa, we can still develop, you know, a more engaging relationship with the PRC?

DR. ERICKSON: These are excellent points. I mean clearly, today I am here to talk about the military component. There are obviously many more dimensions to U.S.-China relations, some where we have tremendous shared interests. And it’s important never to lose sight of that.

In terms of the military-specific aspect, where I think there are some differences in national interests and some resulting strategic challenges, it is an interactive situation, so we have to think very carefully. If we act in a certain way, what effect does it have on China? China needs to think, if they act in a certain way, what effect does it have on us? And that’s why we need to communicate.

My personal view is that we need to be communicating to China that an anti-ship ballistic missile capability, if they’re developing it, is a bad idea. It’s inherently destabilizing. It’s going to provoke a very negative reaction on our part. I think no one should doubt that. That shouldn’t come as a surprise. That should be made very clear, to cite one example.

In terms of deciding how to defend ourselves against unfortunate eventualities and possibilities we hope would never happen, I think we have to try to pursue areas that will not lead to unproductive arms racing. The bottom line is we have to do something that’s effective, whatever that may be.

So maybe there are various things we can do that just make our platforms safer. No one can complain about us making our platforms harder to hit or less vulnerable. When you start talking about a situation in which we’re being opposed with asymmetric means, maybe we have to turn the tables and be able to have the capability to do that to someone else. That gets into a more complex calculus of deterrence. I think we have to think carefully through that, but maybe it’s a mixture of approaches.

One potential approach involves developing better capabilities to deal with sea mines, for example. That’s a capability that you don’t hear much about. It’s not very exciting. Nobody is talking about it, but yet it could have a massive impact if sea mines were deployed. What are our plans for dealing with that?

So I think we need a very sophisticated and nuanced approach. I think we need to talk frequently with the Chinese so we can find as much out as we can about what their approach is so we could communicate to them what our core interests are. We need to make it clear that there are certain things that we would see as very destabilizing, make no mistake about that. Thank you. Paul?

Q: I want to stand up because I want to address this to the group rather than to Andrew, who knows this stuff better than I do. The first is there are very few people in the world who can put this together the way Andrew does. I want you to take very seriously what he says because it’s done very, very well. Can I ask one of the staff to bring up Slide 13, please?

The second is that in the context of what Andrew has said. I think it’s important to consider whether this is about Taiwan or this is about China and the United States. And I would argue that it’s about China and the United States – that about 10 or 12 years ago, China decided that it really wasn’t about Taiwan, that it was about China’s military strategic relationship with the United States. And I think that’s a very important perspective to consider this in because that’s really the bottom line in this. Now, finally, this is 13?

ERICKSON: Is this the range rings, Paul?

Q: No. Finally, a picture is worth 1,000 words. This picture, as presented, is about a Yuan-class submarine. But look what’s in the background there.

DR. ERICKSON: The supply ship. I knew you were going to get to that.

Q: Serious-minded, smart, professional navies build supply ships before they build submarines and this is emblematic of the serious-mindedness of China. China understands that to do this it’s not completely going to sea, but China has to be able to go to sea to do what it’s trying to do. It has to be able to maintain itself at sea; it needs to replenish at sea; it has to be mobile at sea. So this is a serious-minded opponent that is dealing from the strategic perspective of the bilateral, not trilateral, military strategic relationship.

DR. ERICKSON: Thank you, Paul. Do we have any other questions before we wrap this up?

ADM. SHUFORD: Well, we don’t want to wrap up until we talk a little bit about the point that Paul just made here. If you see that supply ship, Paul, then you may – when you talk about aircraft carriers or other elements of power projection, it doesn’t necessarily mean that we intend to project power beyond a fairly constrained region, and in this case, the Asia-Pacific region.

Do you see writing that expresses fairly simply from authoritative sources that the key objective is, we all see the economic center moving toward the Pacific – that that’s an area that the Chinese intend to control in the same sense that today we would not be able to be there and along with that, we lose all the influence and the whole strategic calculus shift. Is there writing along those lines, would you say?

DR. ERICKSON: I think, Admiral, this is where we need to bring energy into the discussion because, almost without exception, there is widespread concern in Chinese sources about maritime energy security. We’ve done some other studies that looked at China’s energy future – this is mainly about oil, of course, because they’ve got a lot of coal. They’ve got a lot of things you can use for power plants. But fuel for transport – oil – is not generally fungible. That’s the hard issue here.

ADM. SHUFORD: You think clearly the objective is energy self-sufficiency as opposed to any other sort of political displacement? That would the primary focus?

DR. ERICKSON: Well, I think almost no nation has energy self-sufficiency these days. The point is China’s maritime oil imports are likely to only rise. They’re building some pipelines. They’re discussing some pipelines. Some are realistic; some are not.

The bottom line is that it’s not enough to reduce this increasing need for maritime energy supply. There’s a great concern that that supply may be unsafe. So I think if there were a relatively simple and affordable way for them to safeguard that militarily, they would be strongly encouraged to move in that direction. We see a few things that look like preliminary steps to doing a bit more there.

I would submit, however, that to do this at a very high level, having the ability to actually safeguard very large crude carriers in a high-intensity military scenario, that’s where I don’t see them having the capability yet. They could well develop it in the future, but there are a number of benchmarks I think they’d have to reach first, many of which they haven’t approached yet.

They don’t have the blue-water training and presence experience at this point. That could change, but at this point they don’t have that to draw on. They do have this supply vessel and a couple others but, for example, in the Gulf of Aden deployment, the counter-piracy, they used the same supply ship for the first two rotations even as they switched the destroyers. So this is still an area where they’re working from a low baseline.

ADM. SHUFORD: That would extend – naturally, that would extend their interest well beyond simply the Pacific – the Western Pacific. It would go down through the Strait of Malacca out of the Indian Ocean and that is a huge ambition. A less ambitious objective would be simply to exclude militarily the United States and then that would undermine coalition relationships and create other options for diplomatic leverage and help surrogates.

DR. ERICKSON: Admiral, I think you’re right and we need to look at concentric circles here. And those concentric circles may expand over time. But at the core – I’ve mainly been talking about the core, the East Asian maritime periphery, that’s where high intensity capabilities, combat level capabilities are getting extremely high.

Going beyond that – China has global interests. At the other extreme, China has global influence. But as for the ability to use military capabilities and high-intensity conflict to do that, in most ways they have not built that balanced force structure. In between, there are regions beyond the immediate maritime periphery on East Asia where they could project some force, but it would be limited.

This is all in motion, but I just think it’s important to disaggregate the different types of capabilities they have and the different types of geographic areas and even to some extent the different technological areas when we talk about electromagnetic and cyber space.

AMB. MIDDENDORF: Andrew, thanks very much.

DR. ERICKSON: Thank you very much. (Applause.)

AMB. MIDDENDORF: Thank you very much, Andrew, and also Admiral Shuford. I’m looking forward on September 18th to having Paul Giarra discuss the implications for security in Asia that stem from China’s anti-ship ballistic missile system and eventually their ability to project power against CONUS itself…. It’s now – as we’re seeing in the financial world, a potential for moving towards being not only a major player in the world but perhaps even – as the Soviets had pretensions to 30 years ago – world domination. … … …

***

FULL POWERPOINT PRESENTATION: SLIDES & NOTES

Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Military Development: Maritime and Aerospace Dimensions,” keynote address at Defense Forum Foundation, B-339 Rayburn House Office Building, Capitol Hill, Washington, DC, 17 July 2009.

SLIDE 1

- Thank you, Suzanne!

- [DISCLAIMER.]

- Shared interests, cooperation, Gulf of Aden.

- But also significant areas of uncertainty, concern.

- These issues are pressing, so that’s what I want to discuss with you today.

SLIDE 2

Here are the major issues that I’ll discuss today.

SLIDE 3

- China merits detailed study, more so today than ever before.

- The National Intelligence Council recently stated that China will be a leading economic and military power in 2025.

SLIDE 4

I want to make 9 major points:

- China is achieving a rapid, if uneven, revolution in maritime and aerospace capabilities.

- These capabilities are divided among China’s Second Artillery (Strategic Rocket Force), Air Force, Navy, and even the ground forces to some extent (e.g., Army Aviation Corps). There is likely to be competition among the services for control of new forces (e.g., space) as they emerge.

- China has carefully acquired technologies which target limitations in the physics of high-technology warfare, placing high-end competitors (e.g., the U.S. Navy) on the costly end of an asymmetric arms race.

- In addition to widespread incremental improvements, China is on the verge of achieving several potentially “game changing” breakthroughs (particularly anti-ship ballistic missiles, but also streaming cruise missile attacks, anti-satellite capabilities, and the application of satellite navigation).

- Such achievements promise to radically improve the PLA’s ‘access denial’ capabilities by allowing it to hold at risk a wide variety of surface- and air-based assets were they to enter strategically vital zones on China’s contested maritime periphery in the event of conflict.

SLIDE 5

- Ongoing challenges for China include human capital, realism of training, hardware and operational deficiencies, and C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance); as well as uncertainties on China’s part about the extent to which it can achieve target de-confliction with existing systems and strategies.

- China has many ways to mitigate these limitations for kinetic operations around Taiwan or other areas of its maritime periphery, and potentially for non-kinetic peacetime operations further afield.

- But conducting high intensity wartime operations in contested environments beyond Taiwan would necessitate major qualitative and quantitative improvements, particularly in aerospace, and corresponding vulnerabilities.

- The biggest strategic question for U.S. Navy planners is whether China will choose to develop the aerospace capabilities to support major kinetic force projection beyond Taiwan, and if so, how.

SLIDE 6

America’s dominant position in the international system hinges on its ability to command the global commons by dominating and exploiting the sea, air and space for military purposes.

— Posen, “Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of U. S. Hegemony,” International Security, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Summer 2003)

- “If the United States does not adapt to these emerging challenges, the military balance in Asia will be fundamentally transformed in Beijing’s favor.”

— Krepinevich, “The Pentagon’s Wasting Assets: The Eroding Foundations of American Power,” Foreign Affairs (July/August 2009)

SLIDE 7

So why do I say we’re witnessing a Chinese maritime and aerospace RMA?

- Let’s consider seminal works by two of America’s great strategic thinkers.

Andrew Krepinevich’s definition of a revolution in military affairs:

- “when the application of new technologies into a significant number of military systems combines with innovative operational concepts and organizational adaptation in a way that fundamentally alters the character and conduct of conflict.”

Eliot Cohen’s criteria: a revolution in military affairs must:

- “change the appearance of combat”

- change “the structure of armies”

- “lead to the rise of new military elites”

- “alter countries’ power position.”

The point is, China can create tremendous challenges for the U.S. military without ever catching up in overall capabilities as a “peer competitor.”

SLIDE 8

- Chinese leaders, armed services, and strategists all see a linkage between maritime and aerospace development.

- We should see this as part a larger military system of systems.

SLIDE 9

Here’s why China is on the cusp of a military revolution.

- I say “on the cusp,” because revolutions in military affairs only fully manifest themselves in actual warfare.

- History shows us that, all too often, there is considerable surprise.

The PLA is developing the potential to meet Cohen’s criteria:

- “change the appearance of combat”

Quote from Secretary Gates (below)

- change “the structure of armies”

Can CSGs survive in their present form?

It is not unthinkable that the U.S. could be forced to complement its current a carrier-centric mid-level conventional warfare fleet with the following bifurcated components:

- a large number of small Coast Guard & HADR-type platforms to engage in presence/intelligence/good-neighbor ‘shaping’ missions in support of the new Maritime Strategy.

- a high-end stealth force consisting of a limited number of surface platforms with reduced radar cross sections as well as a contingent of submarines that emphasized ISR and long-range precision strike.

- “lead to the rise of new military elites”

- Technical specialists (e.g., cyber)

- New organizations (e.g., Space Forces)

- “alter countries’ power position.”

- Is it necessary for the U.S. to “dominate and exploit” the entire global commons?

- If the U.S. is denied military access to certain regions, can it maintain its present position in the international system?

- Can the U.S. maintain its present position and accommodate the rise of another power in this area, and if so how?

As Cohen himself wrote in 1996:

- “A country like… in a few years, China will quickly translate civilian technological power into its military equivalent.”

- Or, as a Chinese interlocutor recently told me, “China’s aerospace revolution is that it now has the ability to actually do things.”

SLIDE 10

Now let’s examine some Chinese asymmetric capabilities… submarines and sea mines

SLIDE 11

- China’s indigenous Song class contains a mix of foreign systems.

SLIDE 12

- In 2006, a Song–class diesel powered submarine broached in close proximity to USS Kitty Hawk.

- In my opinion, China figured out where the Kitty Hawk would be, and sent its submarine to see what it could learn.

- The fact that the submarine operated this closely to the Kitty Hawk supports (but admittedly does not prove) a contention we’ve frequently made, which is that diesel submarines are very hard to detect and that the PLAN CAN get within close range to U.S. ships.

- This is of concern because China’s submarines can deliver devastating weapons, including ASCMs, torpedoes and mines, to the only U.S. forces that could quickly aid Taiwan in the event of PRC military coercion.

SLIDE 13

- China is modernizing its conventional fleet of submarines in parallel with its nuclear fleet.

- The Yuan-class diesel-electric submarine appears to incorporate many Russian Design elements, but retains Chinese characteristics.

- There is speculation about whether or not it has AIP (Air independent Propulsion).

- Proof is lacking.

SLIDE 14

- AIP can give a sub the propulsion and evasion power of an SSN for 2 hours.

- Or cruise quietly at 3 knots without snorkeling for 2-3 weeks.

SLIDE 15

- China now has twelve Kilo-class submarines that have been purchased from Russia.

- The newest 8 include more modern sonar, more quiet engines, and more modern fire control systems which allow the vessels to shoot the Klub 3M54E anti-ship cruise missile.

- Kilos can also shoot sophisticated torpedoes.

- As the photo of Hull 50 here shows, they have sophisticated propellers.

SLIDE 16

- Note the resemblance between the screw on Song Hull 1, from 1994, and the one from the Kilo built and sold in 2006 to China.

- They are virtually identical, with cruciform vortex dissipaters.

- This is a very clear indication that Russia supplied China, less than three years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, with very sophisticated submarine technology.

- Russia has also supplied sophisticated cruise missiles, torpedoes, sea mines, and who knows what else?

SLIDE 17

- Here’s the best photo we’ve yet seen of China’s new Shang-class SSN.

- The Office of Naval Intelligence, in 1997’s Worldwide Submarine Challenges, said it would incorporate technology similar to that of the V-III.

- Many have misconstrued that source, and surmised that the Han-class would look a lot like a V-III, but as you can tell, it does not.

- ONI predicts that only two Shangs will be built.

- This suggests that China has another design ready to be built (allegedly called the Project 095), as it has already constructed a base on Hainan Island capable of supporting a larger fleet.

- There is no need to worry much about Hans, but the Shang and any follow-on submarines could be much quieter, and therefore much more worrisome.

SLIDE 18

- One of the biggest developments in China’s submarine force is the appearance of the 094, or Jin-class, ballistic missile submarine.

- According to ONI, five of these will eventually be built, although the JL-2 missile it will carry has not yet entered service.

- As you can see from the photos, the Jin looks a lot like the Han class.

SLIDE 19

- 6 ASCMs and 2 torpedos.

- Lots of ASCMs for streaming attack.

- Standard Song load-out?

- Submarines as an anti-surface ship weapon platform vice one for ASW weapon?

SLIDE 20

- Large sea mine inventory; 50-100,000.

SLIDE 21

- As part of China’s larger economic/S&T revolution, there has been a profusion of promising indigenous MIW research.

- An important component concerns “intelligizing” mines by upgrading their fusing systems.

- This retrofit can be compared to the addition of a Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) Tail Kit and to the U.S. upgrade of dumb Destructor mines for use in Haiphong.

- Retrofitting preserves the operational relevance of China’s vast reserves of otherwise obsolete mines.

- Multiple sources suggest that PRC is also researching how to develop mines capable of attacking helos and other airborne platforms (top right).

- There are some Chinese writing on merits of nuclear mines, but no proof of actual development.

SLIDE 22

- Russia and the United States both built mines similar to this that were designed to attack nuclear submarines.

- It now appears that China has some similar weapons.

- It would be a simple matter to covertly deploy numbers of these prior to hostilities.

- China figured out where U.S. aircraft carriers operate, and though the challenge is harder, might have obtained or deduced similar information about our submarines.

SLIDE 23

- These two civilian fishing vessels, which are ubiquitous to the seas around China, practice deploying bottom mines as part of a larger “People’s Militia” exercise at the PLAN base in Sanya in December 2004.

- Such exercises occur regularly at various PLAN bases.

- GPS would allow accurate placement of mines in defensive minefields around Chinese ports, even by Maritime Militia forces such as these.

SLIDE 24

- The following 13 points constitute a preliminary outline of China’s apparent mine warfare (MIW) doctrine.

- These points are derived from phrases that appear repeatedly in Chinese MIW writings and are treated as having great strategic & tactical significance.

SLIDE 25

- Depth curves.

- Rocket rising mines (PMK-2) and drifting mines could be used in deep waters to the east of Taiwan.

SLIDE 26

- More Taiwan depth curves.

SLIDE 27

Here are four capabilities China is developing that could significantly alter the ways of war as we now know them:

- ASAT capability

- Some form demonstrated, 11 January 2007.

- Multiple programs reported ongoing.

- Cruise missile saturation attack ability.

- Component capabilities under development

2. ASBM capability

- DF-21 (bottom right) or similar system under development (according to DoD, ONI).

- Navigation Satellite System.

- Could offer reliable signals access in wartime.

3. Beidou/Compass system developing

- I believe that China can overcome the relevant technology and resource challenges.

- The greatest obstacles may be organizational and conceptual.

SLIDE 28

- This is a schematic diagram of an ASBM flight trajectory with mid-course and terminal guidance.

- Note the depiction of second-stage control fins, which would be critical to steering the ASBM through terminal maneuvers.

- This makes an ASBM different from most ballistic missiles, which have a fixed trajectory.

- An ASBM is more like an advanced cruise missile in some respects, with terminal maneuvers to evade countermeasures and to home in on a moving target.

SLIDE 29

- The Department of Defense’s 2009 report on The Military Power of the People’s Republic of China is the most authoritative U.S. unclassified estimate of China’s military capabilities.

- According to this and other official U.S. Government sources, Beijing is pursuing an ASBM based on a variant of its CSS-5 solid propellant medium-range ballistic missile.

- The CSS-5’s 1,500 km+ range could hold ships at risk in a large maritime area, far beyond Taiwan into the Western Pacific–as represented by this YELLOW LINE [INDICATE WITH LASER POINTER].

- For further details, please see my articles available for distribution here and Paul Giarra’s presentation to Defense Forum Foundation in September.

SLIDE 30

On its maritime periphery, then, China already has formidable capabilities.

- The PLA is focused, for now, on anti-access capabilities that would be directly relevant to a Taiwan scenario.

- Precision strikes can destroy Taiwan, U.S. (regional) bases.

- Cruise (and perhaps ballistic) missiles can target U.S. Carrier Strike Groups (CSGs).

This approach affords China a strategic defensive posture along interior lines.

- China need not keep pace with the U.S. technologically.

- Incremental developments may have disproportionate impact.

- The U.S. is inherently vulnerable.

- Operates offensively on exterior lines.

- Must struggle to maintain technological superiority to reduce this vulnerability.

- This poses an intrinsic strategic challenge to United States.

- Potentially denies U.S. access to portions of the global commons (freedom of action).

SLIDE 31

Beyond Taiwan, things get far more complicated.

- Use of aerospace capacity could provide potent command and control options…

- Additional information and decision-making capacity regarding how to use force at the strategic level.

- More flexible deterrent options.

- Ability to fine tune operations

- …but would necessitate continued transformation of the PLA.

- The PLA currently lacks sufficient relevant assets and properly trained personnel to credibly execute necessary ocean surveillance and long-range Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC) defense missions.

China has yet to reform fundamentally its government decision-making system, which is particularly unsuited to crisis situations

- …and stoke ongoing debates regarding de/centralization.

- Will the PLA overcome its centralized, hierarchical command structure and organizational culture to delegate real-time decision-making to lower levels?

- Or attempt to leverage new ISR capabilities and growing communications capacity to further strengthen centralized command and control at higher echelons?

Staffs = key indicator of PLA receptivity to aerospace progress

- Are they merely functionaries?

- Or capable thinkers with professional expertise who are integrated effectively and can develop holistic plans for integrated joint force operations?

SLIDE 32

Mastering air- and space-based platforms and C4ISR would create vulnerabilities.

- Systems might become more vulnerable to electronic, computer network, and kinetic attacks.

- Satellite communications and long-range signals might be jammed or geolocated.

- PLA would acquire its own ‘exterior lines.’

Remaining uncertainties:

- Will the PLA ground forces acquiesce to the increased role of the Air Force, Second Artillery, and Navy, particularly in joint operations?

- How will these services maneuver for control of programs among themselves?

- Can the PLA achieve the confidence to do all these things in the absence of joint wartime operations experience since the small-scale Yijiangshan campaign of 1955?

SLIDE 33

It thus seems clear that:

- The U.S. may face a strong competitor with the ability to contend in all aspects of comprehensive national power, particularly in asymmetric areas.

- At a time when Washington is committed geostrategically in the Middle East and Southwest Asia and faces increasing budgetary challenges at home.

- The focus of competition will be East Asia, where Beijing desires a preeminent position.

- Beijing seems focused on developing capabilities that do not provoke direct military confrontation yet make it increasingly costly for Washington to intervene militarily in the event of a Taiwan crisis.

What will be the consequences for the U.S. role in East Asia?

- What, if anything, should be done to preserve or shape it?

SLIDE 34

- As Andrew Krepinevich just wrote in Foreign Affairs, the U.S. cannot afford to be complacent about Chinese anti-access capabilities.

SLIDE 35

Here are some questions that I’ll leave you with, that we all must try to answer.

- The most fundamental question is whether the PLA will be able to master the developments in air- and space-based platforms & C4ISR needed to support a true blue water sea control capacity.

SLIDE 36

- More questions…

SLIDE 37

- Thank you! I’m now happy to answer your questions.

ADDITIONAL (RESERVE) SLIDES: