“Powers Jockey for Pacific Island Chain Influence”—Interview by Christopher P. Cavas in Defense News

Christopher P. Cavas, “Powers Jockey for Pacific Island Chain Influence,” Interview of Andrew S. Erickson, Defense News, 1 February 2016.

Pacific Island Chains Measure Regional Influence

WASHINGTON — The extensive chains of Pacific islands ringing China have been described as a wall, a barrier to be breached by an attacker or strengthened by a defender. They are seen as springboards, potential bases for operations to attack or invade others in the region. In a territorial sense, they are benchmarks marking the extent of a country’s influence.

“It’s truly a case of where you stand. Perspective is shaped by one’s geographic and geostrategic position,” said Andrew Erickson, a professor with the China Maritime Studies Institute at the Naval War College.

“Barriers is a very Chinese perspective,” said Erickson. “It reflects a concern that foreign military facilities based on the islands may impede or threaten China’s efforts or influence.”

The springboard concept can work offensively or defensively.

“Many Chinese writings express concerns that the chains can be used as springboards for projection and forces against China. But some sources imagine future contingencies where China itself might have growing influence and presence, with Taiwan being most relevant in that regard,” Erickson said.

“Benchmarks speak to the idea that as China increasingly engages in blue-water operations and limited forms of power projection, having more ships through the first island chain offers a set of milestones by which the People’s Liberation Army Navy – or PLAN – can measure its growing presence and capabilities.”

Senior officials and analysts in the West frequently refer to the first and second island chains ringing China to describe both the region’s geography and predict Chinese intentions. Erickson, in a new paper co-authored with Joel Wuthnow of the National Defense University and published in The China Quarterly, carried out a comprehensive, five-year examination of Chinese literature to determine how mainland China views the chains. He reported that the idea originated in the west during the Cold War – Chinese sources often credit 1950s US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles as the concept’s progenitor.

But the notion, Erickson pointed out, isn’t new – it derives from the region’s physical characteristics. Still, the chains have risen in political thinking to become benchmarks that in many ways define the field of play as China’s regional maritime power expands.

“You won’t find in a single authoritative source a precise official consensus on what the chains mean,” Erickson said. “But if you look at a variety of Chinese sources you see a larger pattern that speaks to Chinese concerns about foreign sources having influence over the region and over outstanding disputes. This is not a figment of China’s geostrategic imagination.”

Those concepts play out in numerous fashions, from the weapons China develops to the kinds of exercises and operations the military carries out.

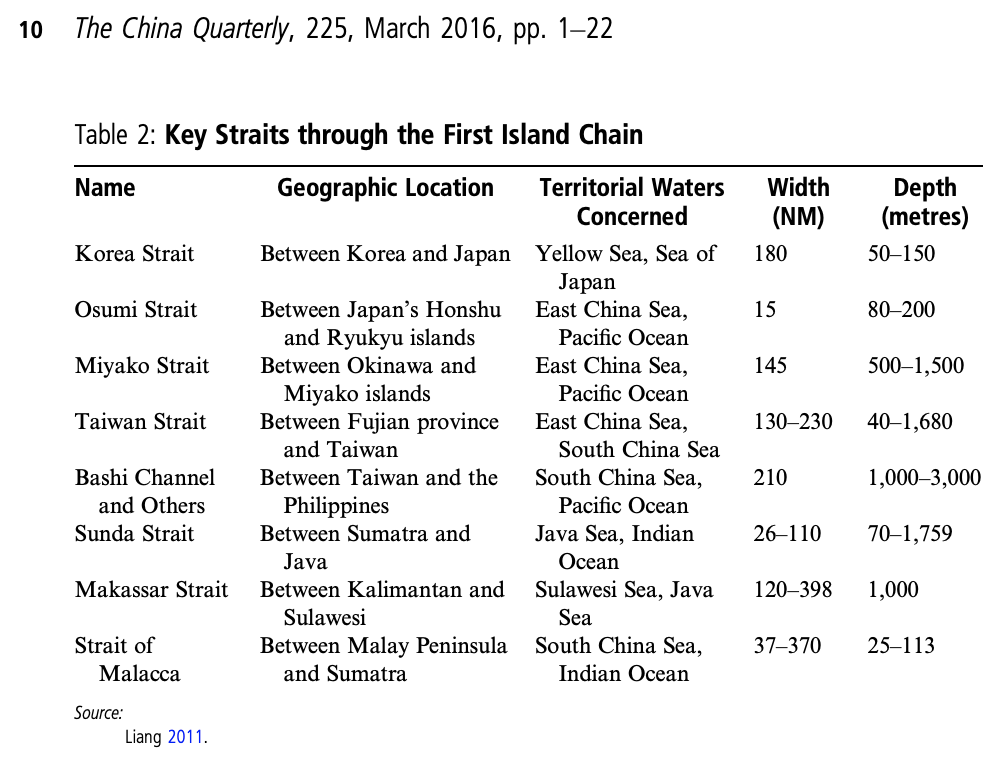

“It looks like we’re seeing a broad-based Chinese effort to become familiar with a variety of different ways to get through the island chains,” Erickson noted. “It’s not hard to imagine that China would want to develop experience with as many different ways as possible to get through the chains.”

China’s development of short-range ballistic missiles is also related to its thinking about the first island chain, Erickson said.

“The vast majority of those weapons appear targeted at Taiwan, which many Chinese authorities see as a key point in the first island chain,” he said. “The vast majority of the missiles I’ve mentioned are designed to target very specific land bases. It’s only very recently that we see a small but growing portion of conventional ballistic missiles developed with the intent of being able to threaten US and perhaps allied naval vessels.”

The Chinese Navy, Erickson pointed out, operates the world’s largest conventional submarine missile force. “The vast majority of those missiles having the right range to appear to be targeted at various US and allied military bases in the region, almost all of which are somewhere along the first island chain.”

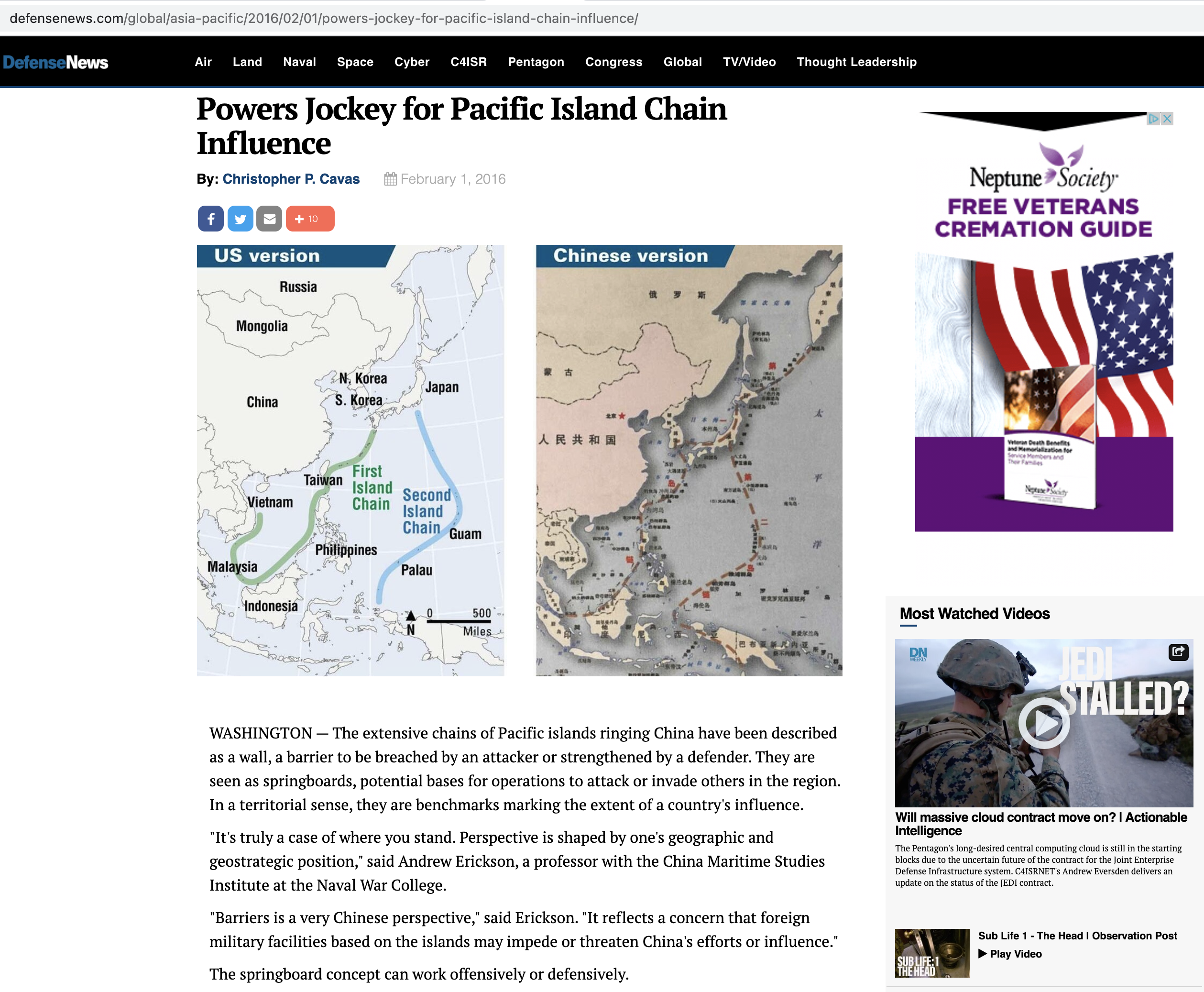

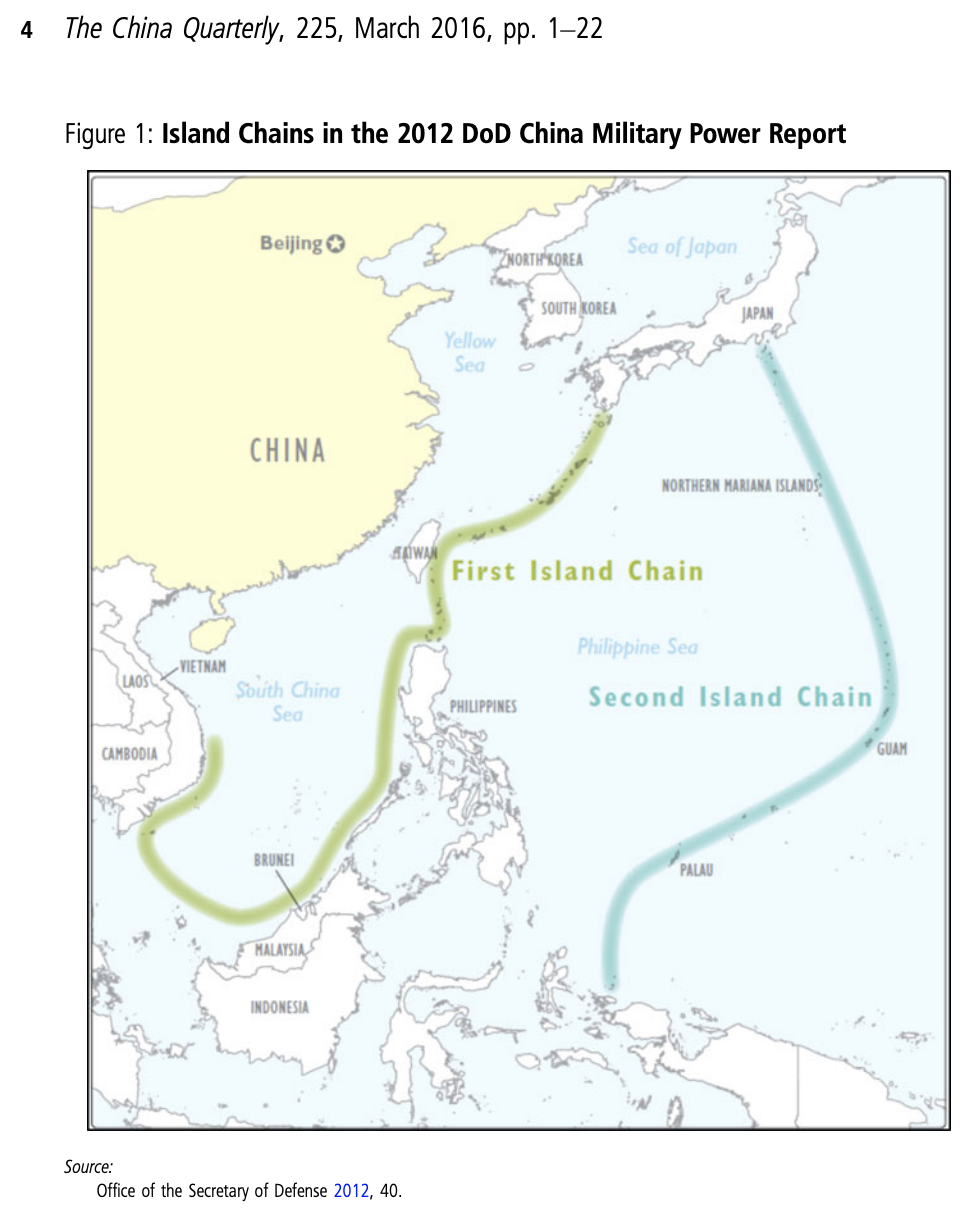

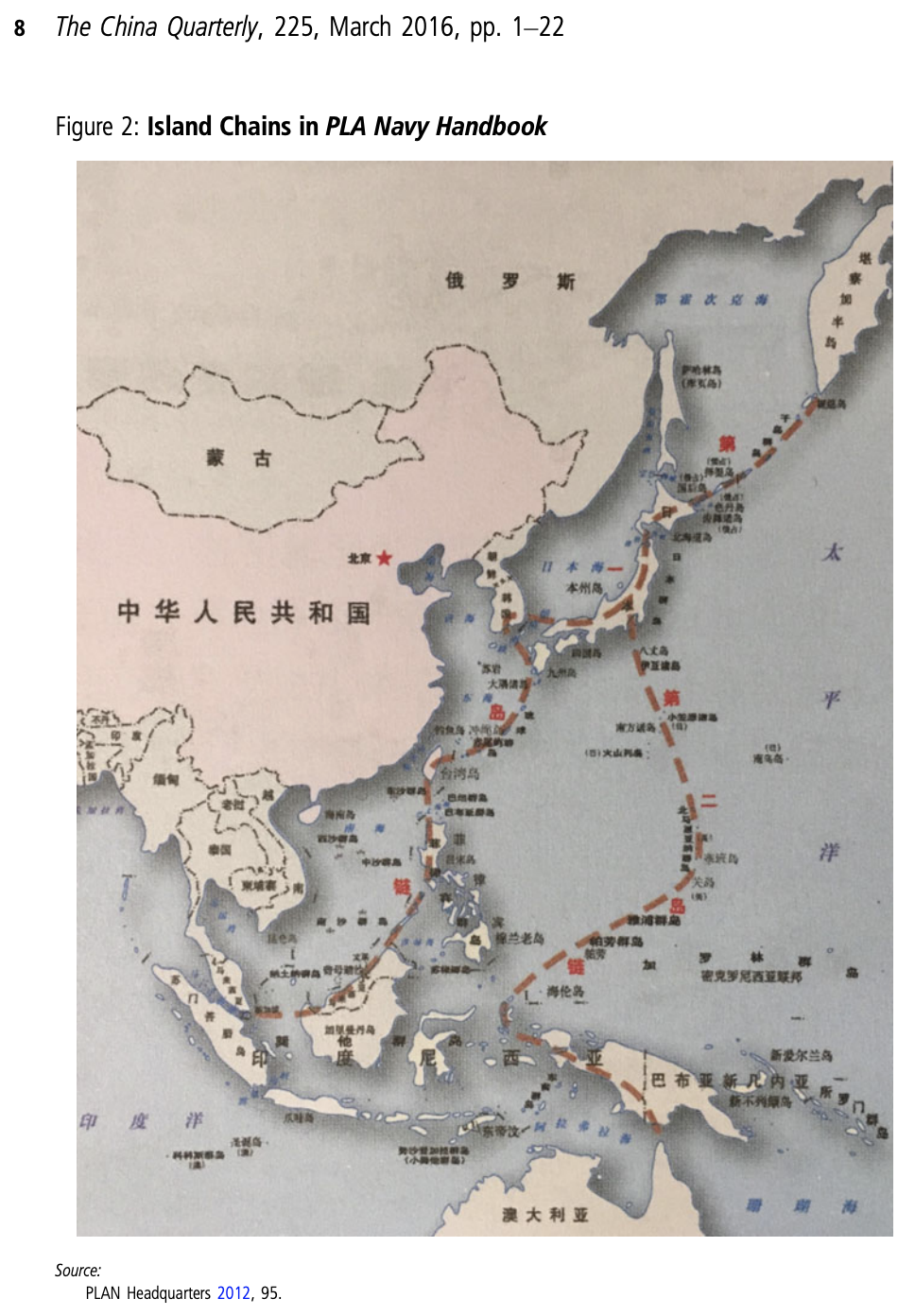

Subtle differences in how the US and China view the chains are evident, Erickson said, in maps produced by the US Defense Department and the Chinese Navy. The Pentagon map, he noted, “doesn’t show South Korea as part of the chain, but the PLAN book very much does show it as belonging to the first island chain.”

Another key difference is in how the Chinese depict the chains joining up in Japan, stretching across the Sea of Okhotsk to the southern tip of Russia’s Kamchatka peninsula – a feature absent from the US map.

The differences indicate different ways of thinking about the chains, Erickson said.

“I don’t think the DoD map is the best possible expression about how the Chinese Navy thinks about the chains – the PLAN map is,” he noted. “This is a case of differences in nuance, not in fundamental differences. I don’t think DoD has gotten this wrong, it’s just a different focus.”

China’s recently aggressive island-building strategy, Erickson observed, is related to the springboard and barrier concepts.

“The chain traditionally has made use of existing geography, but you could argue that China is now making its own island chain – as a springboard for itself and to create a barrier to others,” Erickson said. “I haven’t yet seen Chinese sources that refer to this artificial island construction development as an island chain type thing, but if we look at it conceptually we’re really talking about similar things. That’s one reason I think there’s so much US, regional and allied concern about Chinese activities in the South China Sea.”

Among countries in the region, Russia and Korea are less involved with island chain concepts. “Russia has bigger geostrategic problems to worry about,” Erickson said, while South Korea “by necessity is so focused on security threats from the north that that is the fundamental factor affecting their nation’s geostrategic orientation.”

Japan, across the seas from Russia and Korea, is in a different position.

“In many ways Japan is as central to island chain thinking as one can get,” Erickson said. “Japan constitutes the largest portion of the first and second chains as any other nation. It is a nation of more than 6,000 islands. It is as close to a natural sea power as a nation can get.”

Before World War II, Japan also described the western Pacific in island chain terms.

“Back when imperial Japan was trying to gain control of the first, second and even a third chain – the Aleutians – there was a concern that if Japan didn’t control the Philippines, Guam and Hawaii the Americans would, to Japan’s geostrategic detriment,” said Erickson. “At the outset of World War II, Japan made an extraordinary effort to use part of the chains as a springboard, and they were indeed benchmarks of Japanese military progress. That was only halted then the US turned island-hopping in the other direction.”

“Today, Japan is concerned about Chinese attempts to influence and control areas and to develop weapon systems vis-a-vis these island chains,” Erickson added. “And there’s a lot of Japanese concern about ongoing Chinese efforts to penetrate the chains using increasingly powerful and complex groups of naval vessels. I think Japan feels very much connected to these island chains. As China looks to the chains and aspires to do things, I think Japan feels very targeted by that, it feels it very acutely.”

Taiwan, unsurprisingly, often stands out in the attention it receives in Chinese writings.

“Many Chinese sources emphasize their view of Taiwan’s status as a key node on the first island chain,” Erickson said. “Some Chinese sources see this not only as a springboard against mainland China, but a number of sources express aspirations of eventually [bringing the island] under mainland control, perhaps in a very robust fashion that would allow for some form of Chinese-controlled military facilities. We see discussion of ports, particularly on the east coast of Taiwan, allowing for China to conclusively break out of the confines of the first island chain once and for all.”

“I see no other part of an island chain that is really in the category of what some Chinese strategists ultimately aspire to control and own themselves,” Erickson said. “That definitely sets Taiwan apart.”

And while most attention is focused on the first island chain running south along the eastern edge of the South China Sea, the significance of the second chain, which includes the US territory of Guam, could grow.

“A number of Chinese sources see this as a rear staging area for US and allied forces,” Erickson said.

“But the second island chain will grow in China’s geostrategic thinking. As China continues to send naval forces afield, it will be a benchmark.”

Over time, he added, “China can do more to hold Guam and other parts of the second island chain at risk.”

HERE IS THE JOURNAL ARTICLE REFERENCED IN THE ABOVE INTERVIEW:

Andrew S. Erickson and Joel Wuthnow, “Barriers, Springboards and Benchmarks: China Conceptualizes the Pacific ‘Island Chains’,” The China Quarterly 225 (March 2016): 1-22.

Barriers, Springboards and Benchmarks: China Conceptualizes the Pacific “Island Chains”

Andrew S. Erickson, US Naval War College, Newport, RI; and Joel Wuthnow, US National Defense University, Washington, DC

Abstract

US government reports describe Chinese-conceived “island chains” in the Western Pacific as narrow demarcations for Chinese “counter-intervention” operations to defeat US and allied forces in altercations over contested territorial claims. The sparse scholarship available does little to contest this excessively myopic assertion. Yet, further examination reveals meaningful differences that can greatly enhance an understanding of Chinese views of the “island chains” concept, and with it important aspects of China’s efforts to develop as a maritime power. Long before China had a navy or naval strategists worthy of the name, the concept had originated and been developed for decades by previous great powers vying for Asia-Pacific influence. Today, China’s own authoritative interpretations are flexible, nuanced and multifaceted – befitting the multiple and sometimes contradictory factors with which Beijing must contend in managing its meteoric maritime rise. These include the growing importance of sea lane security at increasing distances and levels of operational intensity.

摘要

美国政府报告把中国设想的西太平洋 “岛链” 概念描述为中国军队为在有关领土争端的 “反干涉”作战中试图打败美国和盟国部队而设立的狭窄的界线。寥寥无几的相关研究对这个过于短视的看法也没有提出不同意见。然而, 进一步的分析却发现此概念有迥然不同的含义。这些含义能大大增强我们对中国为发展成为一个海洋大国所做出的努力的理解。这个概念是在中国有一个现代的海军或海军战略家之前由其他有影响力的大国为争夺亚太地区的影响力而发展起来的。如今, 中国对此概念的权威解释显示出其灵活性, 微妙性和多面性。这些解释特征恰恰能与北京在管理其海上崛起过程中许多有时是相互矛盾的因素相适应。这些因素包括由于不断增大距离和活动强度所导致的海上通道安全日益增长的重要性。

Keywords

China; island chain; strategy; military; maritime; navy

关键词

中国; 岛链; 战略; 军事; 海事; 海军

Footnotes

* These are the authors’ personal views, and not those of their respective institutions. For comments on earlier drafts, the authors thank Dennis Blasko, M. Taylor Fravel, Ryan D. Martinson, Ivan Rasmussen, Al Willner, and three anonymous reviewers.

***

Outside observers naturally seek to understand the geostrategic basis for China’s rapid maritime development. Accordingly, US scholarship and government documents regularly make assertions about Chinese military views of Western Pacific “island chains” (daolian 岛链). In many cases, the argument is that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) uses the island chains as benchmarks for a potential “counter-intervention” campaign directed against US and allied forces in the region. However, these analyses rarely document evidence from PLA sources. This raises important questions: how do Chinese strategists themselves define “island chains,” and how do they assess them operationally and strategically?

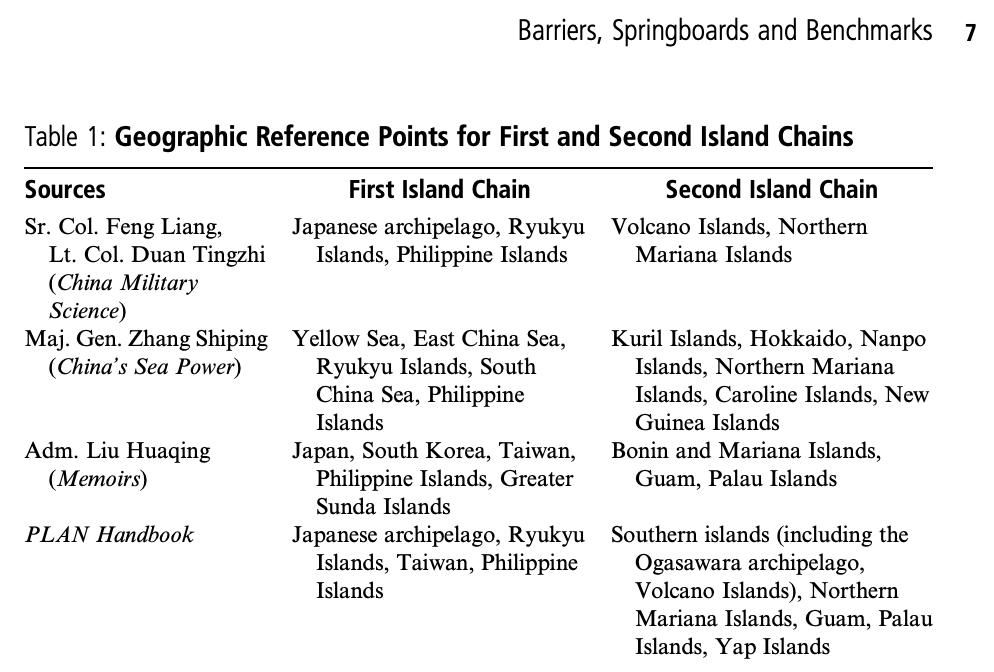

Drawing on manifold underutilized Chinese sources, we contend that the island chains concept is foreign in origin but adopted and reinterpreted in China, and that authoritative Chinese interpretations are flexible, nuanced and multifaceted. Geographically, Chinese writings offer varying definitions of the island chains, with some considerably more expansive than others. More importantly, Chinese sources offer diverse perspectives on the island chains’ operational and strategic significance. In particular, various Chinese authors assert that the island chains are (1) barriers that China must penetrate to achieve freedom of manoeuvre in the maritime domain; (2) springboards for power projection by whomever controls a given island chain; and (3) benchmarks for the advancement of Chinese maritime and air force projection in the Asia-Pacific. In each of these respects, the discourse on the island chains provides valuable insight into how the PLA is thinking about the challenges and opportunities facing China as it seeks to become a maritime power.

This article is organized into five sections. The first discusses foreign analyses of the concept of island chains, and suggests that many of these sources focus rigidly on counter-intervention issues. The following section addresses the origins and historical significance of the island chains concept. The article then examines Chinese views of the geographic attributes of the island chains before considering how Chinese military analysts interpret their operational and strategic significance. The final section discusses the implications for China’s naval development, and for that of the US and its allies. …

References

- Acheson, Dean. 1951. “Remarks by the secretary of state (Acheson) before the National Press Club, Washington, January 12, 1950.” In Dennett, Raymond and Turner, Robert (eds.), Documents on American Foreign Relations, Vol. 12: January 1–December 31, 1950. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 426–433. Google Scholar

- Bai, Yanlin. 2007. “Daolian shang de shijie haijun” (The world navies on the island chains). Dangdai haijun 10(October), 10–20. Google Scholar

- Bi, Xinglin (ed.). 2002. Zhanyi lilun xuexi zhinan (Campaign Theory Study Guide). Beijing: Guofang daxue chubanshe. Google Scholar

- Cheng, Dean. 2011. “Sea power and the Chinese state: China’s maritime ambitions.” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder Report No. 2576, 11 July, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2011/07/sea-power-and-the-chinese-state-chinas-maritime-ambitions. Accessed 21 December 2015. Google Scholar

- Cliff, Roger. 2011. “Anti-access measures in Chinese defense strategy.” Testimony before the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission, Washington, DC, 27 January. Google Scholar

- Cole, Bernard. 2010. The Great Wall at Sea: China’s Navy in the Twenty-First Century (2nd ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. Google Scholar

- Cole, Bernard. 2014. “Island chains and naval classics.” US Naval Institute Proceedings 140(11), 68–73. Google Scholar

- Dan, Jie, and Ju, Lang. 2005. “Fei xiang Zhongguo de ‘ni huo’ he ‘xiong’” ([Russian] “Backfire” and “Bear” [Strategic Bombers] to fly to China). Jianzai wuqi March, 12–16. Google Scholar

- Ding, Zhaolun. 2011. “Qiaokai weilai haizhan zhisheng zhi men” (Knock open the gate of winning future sea battles), Renmin haijun, 11 March. Google Scholar

- Du, Jingchen. 2010. “Ba yuanhai dayang dangzuo ‘lian bing chang’” (Regard the distant seas and oceans as training areas), Renmin haijun, 18 May. Google Scholar

- Feng, Liang, and Duan, Tingzhi. 2007. “Zhongguo haiyang diyuan anquan tezheng yu xin shiji haishang anquan zhanlüe” (Characteristics of China’s sea geostrategic security and sea security strategy in the new century). Zhongguo junshi kexue 1, 22–29. Google Scholar

- Flynn, Michael. 2014. “Annual threat assessment.” Statement before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Washington, DC, 11 February. Google Scholar

- Fravel, M. Taylor, and Christopher, Twomey. 2015. “Projecting strategy: the myth of Chinese counter-intervention.” The Washington Quarterly 37(4), 171–187. CrossRef | Google Scholar

- Friedman, B.A. 2015. 21st Century Ellis: Operational Art and Strategic Prophecy for the Modern Era. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. Google Scholar

- Fuell, Lee. 2014. “Broad trends in Chinese air force and missile modernization.” Testimony presented to the US–China Economic Security Review Commission, Washington, DC, 30 January. Google Scholar

- Guoji zhanwang. 2005. “Meiguo yingpai renwu zai fang kuangyan – toushi Meiguo kongzhong daji Zhongguo jihua” (Members of the US “hawk faction” rave again: a perspective on a US plan to attack China from the air). Guoji zhanwang 9, 27–28. Google Scholar

- Hammes, T.X. 2012. “Offshore control: a proposed strategy for an unlikely conflict.” Strategic Forum 278, 1–14. Google Scholar

- Hattendorf, John, Simpson, B. Mitchell and Wadleigh, John R.. 1984. Soldiers and Scholars: The Centennial History of the US Naval War College. Newport, RI: Naval War College Press. Google Scholar

- Holmes, James. 2011. “Integrated Chinese saturation attacks: Mahan’s logic, Mao’s grammar.” In Erickson, Andrew and Goldstein, Lyle (eds.), Chinese Aerospace Power: Evolving Maritime Roles. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 407–422. Google Scholar

- Huang, Alexander. 1994. “The Chinese navy’s offshore active defense strategy: conceptualization and implications.” Naval War College Review 47(3), 7–32. Google Scholar

- Hui, Zhu. 2009. Zhanlüe kongjun lun (Strategic Air Force). Beijing: Lantian chubanshe. Google Scholar

- Kaplan, Robert. 2010. “The geography of Chinese power.” Foreign Affairs 89(3), 22–41. Google Scholar

- Krepinevich, Andrew F. Jr. 2015. “How to deter China: the case for archipelagic defense.” Foreign Affairs 94(2), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2015-02-16/how-deter-china. Google Scholar

- Li, Yihu. 2007. “Cong hailu erfen dao hailu xichou – dui Zhongguo hailu guanxi de zai shenshi” (Sea and land power: from dichotomy to overall planning – a review of the relationship between sea and land power). Xiandai guoji guanxi 8, 1–7. Google Scholar

- Liang, Fang. 2011. Haishang zhanlüe tongdao lun (On Maritime Strategic Access). Beijing: Shishi chubanshe. Google Scholar

- Liu, Huaqing. 2004. Liu Huaqing huiyi lü (Memoirs of Liu Huaqing). Beijing: Jiefangjun chubanshe. Google Scholar

- Lou, Douzi. 2004. “Tizhi bianzhi tiaozheng hou, kan haijun kongjun de bu shi (yi)” (Looking at navy and air force dispositions following establishment restructuring (part 1)), Jiefangjun bao, 14 July. Google Scholar

- Ma, Guangwu. 2011. Zhongguo heping fazhan zhong de qiangjun zhanlüe (The Strong Army Strategy in China’s Peaceful Development). Beijing: Junshi kexue chubanshe. Google Scholar

- MacArthur, Douglas. 1951. “Old soldiers never die…” Typescript speech for address given 19 April, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trm048.html. Accessed 10 December 2015. Google Scholar

- McDevitt, Michael. 2011. “The PLA navy’s antiaccess role in a Taiwan contingency.” In Saunders, Phillip C., Yung, Christopher, Swaine, Michael and Yang, Andrew Nien-dzu (eds.), The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles. Washington, DC: NDU Press, 191–214. Google Scholar

- Miller, Edward. 1991. War Plan Orange: The US Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. Google Scholar

- Muller, David. 1983. China as a Maritime Power. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Google Scholar

- Nathan, Andrew J. 1996. “China’s goals in the Taiwan Strait.” The China Journal 35, 87–93.CrossRef | Google Scholar

- Office of the Secretary of Defense. 2011. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. Washington, DC: DoD. Google Scholar

- Office of the Secretary of Defense. 2012. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. Washington, DC: DoD. Google Scholar

- Office of the Secretary of Defense. 2015. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. Washington, DC: DoD. Google Scholar

- Peattie, Mark. 1988. Nan‘yō: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885–1945. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Google Scholar

- Peng, Guangqian, and Yao, Youzhi (eds.). 2005. The Science of Military Strategy. Beijing: Military Science Press. Google Scholar

- PLAN Headquarters. 2012. Zhongguo haijun junren shouce (Handbook of PLA Navy Personnel). Beijing: Haichao chubanshe. Google Scholar

- Qingnian cankao. 2012. “Zhongguo haijun mouhua pojie ‘daolian fengsuo’” (China’s navy plots to break through the “island chain blockade”), 31 October. Google Scholar

- Run, Jiaqi. 2014. “Zhuanjia cheng Zhongguo junshi liliang poshi Meiguo cong diyi daolian xiang hou shousuo” (Experts say China’s military power has forced the United States to retreat from the First Island Chain), Renmin wang, 8 October. Google Scholar

- Sharman, Christopher H. 2015. “China moves out: stepping stones toward a new maritime strategy.” China Strategic Perspectives 9, 1–60. Google Scholar

- Swenson-Wright, John. 2005. Unequal Allies? United States Security and Alliance Policy toward Japan, 1945–1960. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Google Scholar

- US Department of State. 1948. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Google Scholar

- Vego, Milan. 1992. Soviet Naval Tactics. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. Google Scholar

- Vego, Milan. 2014. Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945. Newport, RI: Naval War College Press. Google Scholar

- Wachman, Alan. 2007. Why Taiwan? Geostrategic Rationales for China’s Territorial Integrity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Google Scholar

- Wang, Jing (ed.). 2004. “Mei hangmu zai Taiwan zhouwei yanxi shenme (er)” (What exercises are the US aircraft carrier conducting around Taiwan? Part 2), CCTV International, 19 June. Google Scholar

- Wang, Weixing, and Teng, Jianqun. 2000. “Air-launched cruise missiles are hanging at Asia’s door,” Jiefangjun bao, 6 September, 12. Google Scholar

- Whitney, Courtney. 1956. MacArthur: His Rendezvous with History. New York: Knopf. Google Scholar

- Willard, Robert. 2011. “Statement of Admiral Robert F. Willard, US Navy.” Statement before the House Armed Services Committee, Washington, DC, 6 April. Google Scholar

- Wu, Qingli, and Xie, Jingsheng. 2004. “Toushi Meijun quanqiu junli da tiaozheng” (Analysis of global force readjustment by the US military), Jiefangjun bao, 1 September, 12. Google Scholar

- Xu, Changyin. 2010. “Zhandou jianting biandui yuanhang zonghe baozhang wenti qietan” (Preliminary discussion on issues in comprehensive support of warship formations during long-distance voyages), Renmin haijun, 6 December. Google Scholar

- Xu, Qi. 2004. “21 shiji chu haishang diyuan zhanlüe yu Zhongguo haijun de fazhan” (Maritime geostrategy and the development of the Chinese navy in the early 21st century). Zhongguo junshi kexue 59(4), 75–81. Google Scholar

- Xu, Xikang. 2011. “Yi Liu Huaqing siling de haijun zhanlüe” (Recalling Commander Liu Huaqing’s naval strategy), Zhongguo shehui kexue bao, 20 June. Google Scholar

- Yu, Yang, and Qi, Xiaodong. 2005. “Meijun jidi da tiaozheng: miaozhun ‘xian fazhi ren’ bai bing bu zhen” (Major realignment of US military bases: deployment aimed at launching “preemptive strikes”), Zhongguo guofang bao, 19 April, 2. Google Scholar

- Zhang, Qingbao, and Lin, Xiaoying. 2013. “Zheili de diqing bu jia yinhao” (Here, the enemy situation is no longer in quotation marks), Renmin haijun, 13 May. Google Scholar

- Zhang, Shiping. 2009. Zhongguo haiquan (China’s Sea Power). Beijing: Renmin ribao chubanshe. Google Scholar

- Zhongguo guoji guanxi yanjiuyuan. 2005. Guoji zhanlüe yu anquan xingshi pinggu 2004–2005 (Review of the International Strategic and Security Situation 2004–2005). Beijing: Shishi chubanshe. Google Scholar

- Zhongguo junshi kexue yuan. 2013. Zhanlüe xue (Science of Strategy). Beijing: Junshi kexue chubanshe. Google Scholar

- Zu, Ming. 2006. “Meiguo zhu xi taiping diqu haijun bingli bushu yu jidi tixi shiyitu” (A schematic diagram of the US naval forces deployed and system of bases in the Western Pacific). Jianchuan zhishi 2(January), 24. Google Scholar

- Zuo, Liping. 2013. “Hangmu biandui chicheng hai zhangchang de daguo de zhong jian” (Carrier battle group gallops to the sea battlefield, is the strong sword of a great nation), Renmin haijun, 3 December. Google Scholar