The Struggle for Blue Territory: Chinese Maritime Militia Grey-Zone Operations

Conor M. Kennedy, “The Struggle for Blue Territory: Chinese Maritime Militia Grey-Zone Operations,” The RUSI Journal 163.5 (October/November 2018): 8–19.

China employs three sea forces to defend and advance its maritime claims – the People’s Liberation Army Navy, the China Coast Guard and the maritime militia. This third force plays a vital role in protecting China’s maritime rights and interests, performing tasks that fit what observers are increasingly referring to as the ‘grey zone’ between war and peace. In this article, Conor Kennedy addresses Chinese considerations that guide the use of maritime militia and defines a range of operations by reviewing publicly known cases.

China employs three sea forces to defend and advance its maritime claims: the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN); the China Coast Guard (CCG); and the maritime militia. China’s militia was originally a force of armed peasants called up to defend Chinese territory from foreign invaders. Today, China still implements a nationwide militia- building system and preserves the militia’s status as an official component of its armed forces. The maritime militia is a subcomponent of militia which comprises commercial mariners, often fishermen, who can be mobilised as paramilitary personnel to fulfil state functions.1 China’s maritime militia began as an early tool of necessity for warfighting when the PLAN was weak. Today it is a tool of choice for China’s more recent assertive posture and continues to be involved in incidents at sea.

While much is written on the maritime militia’s past and potentially future roles in supporting PLAN warfighting, to date there has been little systematic effort to define the range of operations it performs in the service of China’s maritime disputes. This article fills this gap in two parts. First, it discusses the strategic considerations guiding Beijing’s use of militia in its maritime disputes. Why fund a militia when China could simply rely on its powerful navy and coast guard to pursue its claims? Second, the article examines specific types of militia operations, its functions and tactics, and known cases in which these operations have been performed.

Grey-Zone Advantages for Maritime Militia

In peacetime, the maritime militia serves China’s dispute strategy, which can be divided into three broad categories as described in the Naval War College Review by Peter Dutton: disputes over territorial features; disputes over the shape and extent of zones of jurisdiction; and disputes over coastal state authorities to regulate foreign activities – above all, military activities – in Chinese-claimed jurisdictional waters.

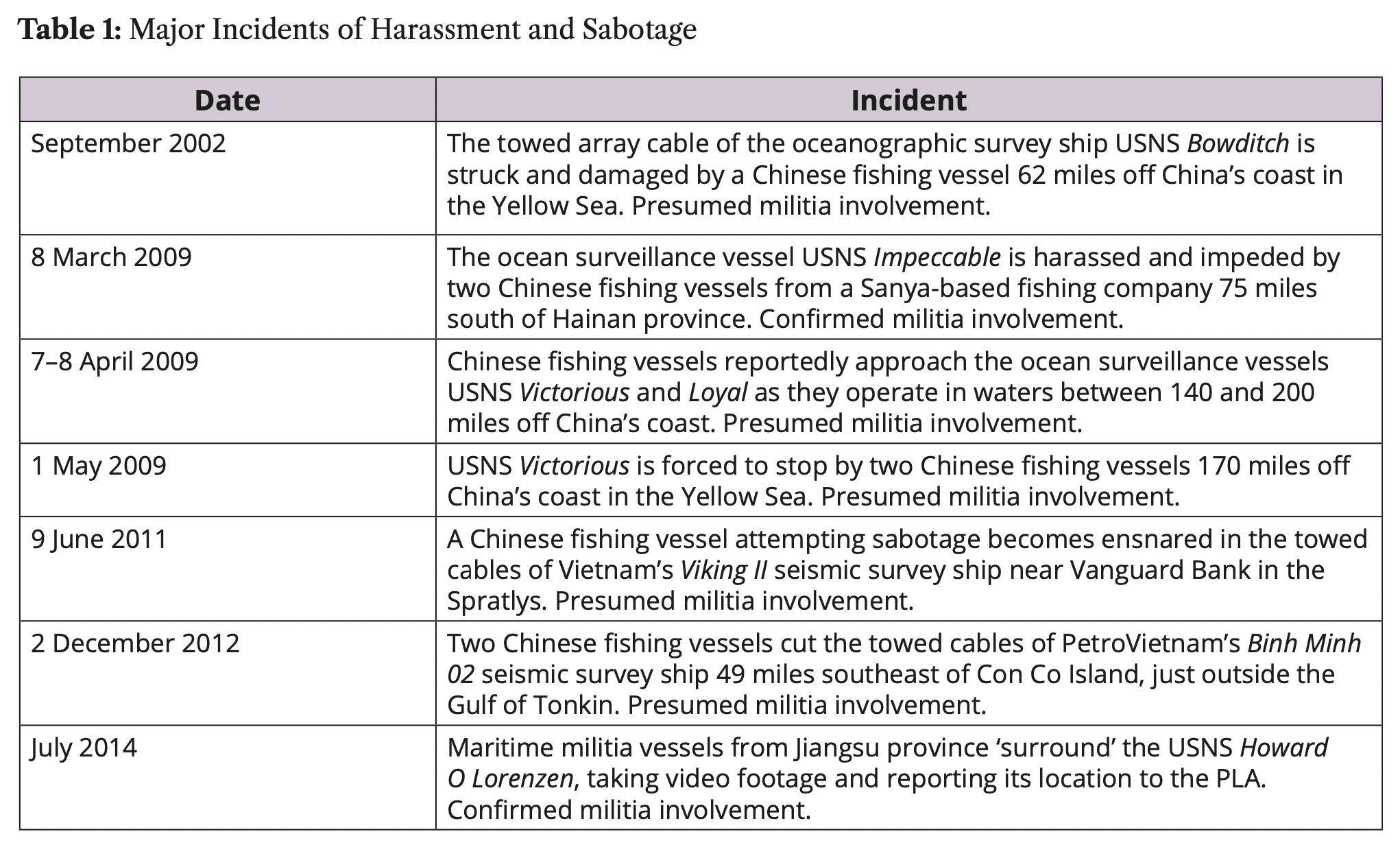

The first two involve China’s neighbours: Japan and Taiwan in the East China Sea; and the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan, Vietnam and Indonesia in the South China Sea. The third primarily involves the US, regarding US freedom of navigation operations meant to challenge excessive Chinese claims in the South China Sea or Chinese attempts to restrict the rights of US Navy Special Mission Ships to conduct operations within its exclusive economic zone.2 The maritime militia plays an important role in defending and advancing China’s position in all three types of dispute. Its actions are often framed as efforts to safeguard China’s maritime rights and interests.3

Despite being a component of China’s armed forces, when conducting rights protection operations the maritime militia is generally unarmed, and its members frequently operate in civilian guise. However, they serve under the command authority of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and sometimes the CCG. This dual identity makes them uniquely suited to serve key functions in China’s dispute strategy. To foreign ships transiting disputed areas, the maritime militia would likely appear simply as civilian fishermen, masking a potentially state-sponsored operation.

Use of militia forces is guided both by political and operational considerations. Politically, militia forces can vigorously pursue China’s claims without opening the country to criticism for ‘gunboat diplomacy’ or justifying foreign escalation (or intervention). When not in uniform, their activities can be framed as private actions. This plausible deniability makes them ideal instruments for pursuing national aims in the ‘grey zone’ between war and peace.4

Indeed, the head of the Zhanjiang City Xiashan District’s People’s Armed Forces Department (PAFD), Chen Qingsong, describes the role of the maritime militia as a means of preventing war: ‘In peace [the maritime militia] not only play a role in declaring sovereignty, fighting harassment by foreign enemies and rights protection security, they also serve as a buffer for war [Zhanzheng Huanchongqi] to create a peaceful, ordered and stable maritime security environment’.5

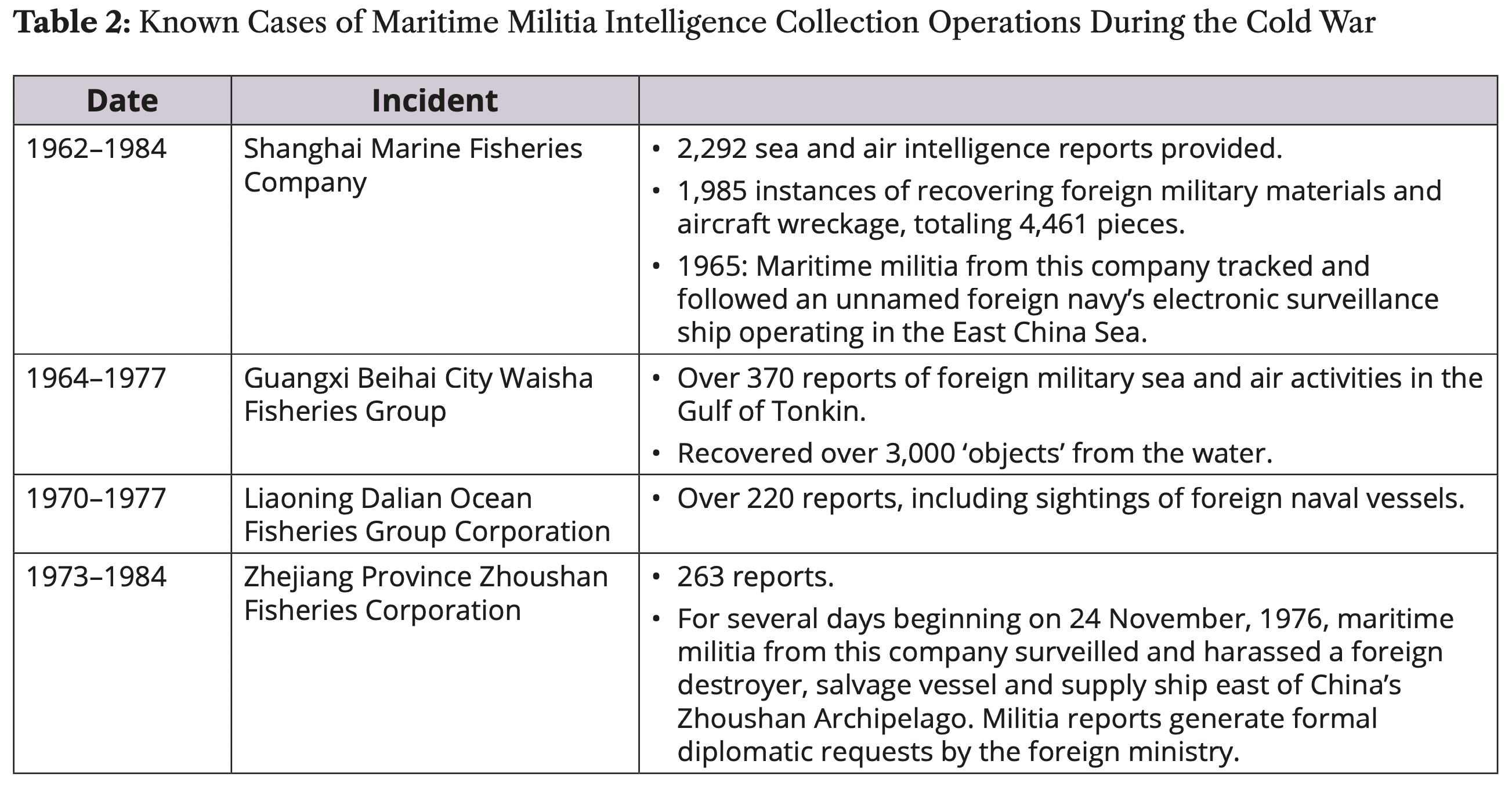

While in many ways inferior to China’s other two sea forces, the navy and coast guard, the maritime militia also offers unique operational capabilities. Militia forces tend to operate smaller and more manoeuvrable vessels, which are better equipped for plying shallow waters and engaging small foreign vessels. Moreover, because they are far more numerous than China’s naval and coast guard assets, militia forces can cover much broader swathes of ocean, enhancing presence and bolstering maritime- domain awareness. … …

Conclusion

The maritime militia allows China to energetically pursue its maritime claims while avoiding many of the escalation, reputational and other risks that would accompany use of traditional instruments of national power, such as the PLAN.

This article has classified four types of operations – presence, harassment and sabotage, escort, and ISR – that the maritime militia conducts to support China’s position in its maritime disputes. In exploring each type of operation, specific examples of events at sea are identified.

One key conclusion is that all these maritime militia ‘grey-zone’ operations have roots in earlier eras. While the disputes have intensified in recent years and material and organisational improvements in the maritime militia continue in step with China’s other maritime services, the basic operations themselves are not new. Increasing operational frequency and capabilities of the maritime militia, and greater coordination with the PLAN and the CCG, appear to be a recent innovation made over the past couple of decades to better serve China’s more assertive behaviour in its maritime disputes. The geographic scope of its operations is also greatly expanding.

In the past, the maritime militia was a tool used out of necessity to support the previously weaker PLAN. Beijing’s contemporary objective to assert control over disputed maritime areas has placed greater emphasis on maritime rights protection missions which in turn have raised the profile and capabilities of the maritime militia. Chosen for its unique role as a buffer for war, the maritime militia is now standing on the front line of disputes, as during the 2009 USNS Impeccable incident, the 2014 Hai Yang Shi You 981 confrontation, or the 2017 attempt to intimidate the Philippines near Thitu Island.

By examining most of the recent publicly known incidents involving China’s maritime militia, this article has sought to define patterns of particular Chinese state behaviour that has played a direct role in incidents at sea. Identifying these activities will prove fundamental to future analyses of China’s maritime militia. Whether these forces are employed against Japan in the Senkaku Diaoyu Islands or to disrupt foreign military operations in waters China claims, the maritime militia will impact each of the disputes that China is party to in the East and South China Seas.