New DIA Report—“Challenges to Security in Space”—Offers Copious China-Related Information

Challenges to Security in Space (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence Agency, January 2019).

Click here to download a cached copy.

p. iii

Executive Summary

Space-based capabilities provide integral support to military, commercial, and civilian applications. Longstanding technological and cost barriers to space are falling, enabling more countries and commercial firms to participate in satellite construction, space launch, space exploration, and human spaceflight. Although these advancements are creating new opportunities, new risks for space-enabled services have emerged. Having seen the benefits of space-enabled operations, some foreign governments are developing capabilities that threaten others’ ability to use space. China and Russia, in particular, have taken steps to challenge the United States:

- Chinese and Russian military doctrines indicate that they view space as important to modern warfare and view counterspace capabilities as a means to reduce U.S. and allied military effectiveness. Both reorganized their militaries in 2015, emphasizing the importance of space operations.

- Both have developed robust and capable space services, including space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Moreover, they are making improvements to existing systems, including space launch vehicles and satellite navigation constellations. These capabilities provide their militaries with the ability to command and control their forces worldwide and also with enhanced situational awareness, enabling them to monitor, track, and target U.S. and allied forces.

- Chinese and Russian space surveillance networks are capable of searching, tracking, and characterizing satellites in all earth orbits. This capability supports both space operations and counterspace systems.

- Both states are developing jamming and cyberspace capabilities, directed energy weapons, on-orbit capabilities, and ground-based antisatellite missiles that can achieve a range of reversible to nonreversible effects.

Iran and North Korea also pose a challenge to militaries using space-enabled services, as each has demonstrated jamming capabilities. Iran and North Korea maintain independent space launch capabilities, which can serve as avenues for testing ballistic missile technologies.

The advantage the United States holds in space—and its perceived dependence on it—will drive actors to improve their abilities to access and operate in and through space. These improvements can pose a threat to space-based services across the military, commercial, and civil space sectors.

p. 13

CHINA

“To explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry, and build China into a space power is a dream we pursue unremittingly.”

—China’s Space White Paper, December 26, 201634

China has devoted significant economic and political resources to growing all aspects of its space program, from improving military space applications to developing human spaceflight and lunar exploration programs. China’s journey toward a space capability began in 1958, less than 9 months after the launch of Sputnik-1. However, China’s aspirations to match the Soviet Union and the United States soon faced self-imposed delays due to internal political dynamics that lasted until the late 1960s. China did not launch its first satellite until April 1970. In the early 1980s, China’s space program began moving with purpose.35

Beijing now has a goal of “[building] China into a space power in all respects.”36 Its rapidly growing space program—China is second only to the United States in the number of operational satellites—is a source of national pride and part of President Xi Jinping’s “China Dream” to establish a powerful and prosperous China. The space program supports both civil and military interests, including strengthening its science and technology sector, international relationships, and military modernization efforts. China seeks to achieve these goals rapidly through advances in the research and development of space systems and space-related technology.37,38,39,40,41

China officially advocates for peaceful use of space, and it is pursuing agreements at the United Nations on the nonweaponization of space.42 Nonetheless, China continues to improve its counterspace weapons capabilities and has enacted military reforms to better integrate cyberspace, space, and EW into joint military operations.

[Caption: China launched the Shenzhou-9 in June 2012, which was the first crewed spacecraft to dock with the Tiangong-1 space laboratory.]

p. 14

Strategy, Doctrine, and Intent

China’s Military Strategy

In 2015, Beijing directed the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to be able to win “informatized local wars” with an emphasis on “maritime military struggle.” Chinese military strategy documents also emphasize the growing importance of offensive air, long-distance mobility, and space and cyberspace operations. China expects that its future wars mostly will be fought outside its borders and will involve conflict in the maritime domain. China promulgated this through its most recent update to its “military strategic guidelines,” the top-level directives that Beijing uses to define concepts, assess threats, and set priorities for planning, force posture, and modernization.

The PLA uses “informatized” warfare to describe the process of acquiring, transmitting, processing, and using information to conduct joint military operations across the domains of land, sea, air, space, cyberspace, and the electromagnetic spectrum during a conflict. PLA writings highlight the benefit of near-real-time shared awareness of the battlefield in enabling quick, unified effort to seize tactical opportunities.43

***

The PLA views space superiority, the ability to control the information sphere, and denying adversaries the same as key components of conducting modern “informatized” wars.44,45,46,47,48,49 Since observing the U.S. military’s performance during the 1991 Gulf War, the PLA embarked on an effort to modernize weapon systems and update doctrine to place the focus on using and countering adversary information-enabled warfare.

Space and counterspace operations will form integral components of PLA campaigns, given China’s perceptions of the importance of space-enabled operations to U.S. and allied forces and the growing importance of space to enable beyond-line-of-sight operations for deployed Chinese forces. The PLA also sees counterspace operations as a means to deter and counter a possible U.S. intervention during a regional military conflict.50,51 PLA analysis of U.S. and allied military operations states that “destroying or capturing satellites and other sensors” would make it difficult to use precision guided weapons.52 Moreover, PLA writings suggest that reconnaissance, communications, navigation, and early warning satellites could be among the targets of attacks designed to “blind and deafen the enemy.”53

Key Space and Counterspace Organizations

China’s space program has a complex structure and comprises organizations in the military, political, defense-industrial, and commercial sectors. The PLA historically has managed China’s space program, and it continues to invest in improving China’s capabilities in space-based ISR, satellite communication, and satellite navigation, as well as human spaceflight and robotic space exploration.54 State-owned enterprises are China’s primary civilian and military space contractors, but China is placing greater emphasis on decentralizing and diversifying its space industry to increase competition.55

As part of the military reforms announced in 2015, China established the Strategic Support Force (SSF) to integrate cyberspace, space, and EW capabilities into joint military operations.56,57,58 The SSF forms the core of China’s information warfare force, supports the entire PLA, and reports directly to the Central Military Commission. The SSF likely is responsible for research and development of certain space and counterspace capabilities. The SSF’s space function is focused primarily on satellite launch and operations to support PLA ISR, navigation, and communication requirements.59

p. 15

Currently, the State Council’s State Administration for Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND) is the primary civil organization that coordinates and manages China’s space activities, including allocating space research and development funds.62 It also maintains a working relationship with the PLA organization that oversees China’s military acquisitions. SASTIND guides and establishes policies for state-owned entities conducting China’s space activities, whereas the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission provides day-to-day management.63,64

The China National Space Administration (CNSA) serves as the public face of China’s civil space efforts.65 China is increasingly using these efforts to bolster relationships with countries around the world, providing opportunities to lead the space community.66,67,68 In April 2018, CNSA stated that China had signed 21 civil space cooperation agreements with 37 countries and four international organizations.69

In the commercial space sector, mixed-ownership enterprises such as Zhuhai Orbita, Expace, and OK-Space offer remote sensing, launch, and communication services.70,71,72 Many of these space technologies can serve a civilian and military purpose and China emphasizes “civil-military integration”—a phrase used, in part, to refer to the leveraging of dual-use technologies, policies, and organizations for military benefit.73

p. 16

Space and Counter-space Capabilities

Space Launch Capabilities

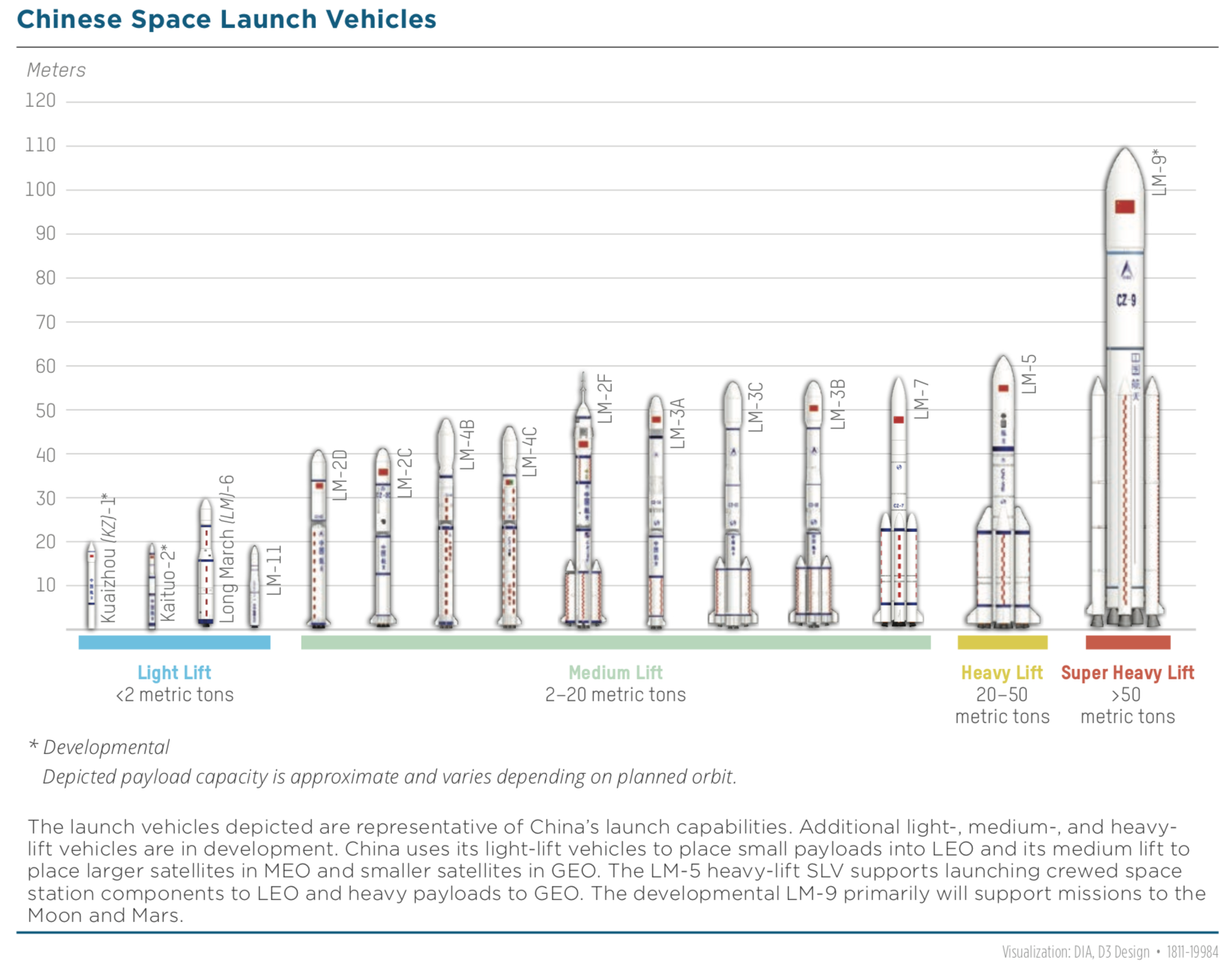

China is improving its space launch capabilities to ensure it has an independent, reliable means to access space and to compete in the international space launch market. Recent improvements reduce launch timelines, increase manufacturing efficiencies, and support human spaceflight and deep-space exploration missions.74 These improvements include new, modular SLVs that allow China to tailor an SLV to the specific configuration required for each customer. Using modular SLVs can lead to increases in manufacturing efficiency, launch vehicle reliability, and overall cost savings for launch campaigns.75 China is also in the early stages of developing a super heavy-lift SLV similar to the U.S. Saturn-V or the newer Space Launch System to support proposed crewed lunar and Mars exploration missions.76

Exhibit: Chinese Space Launch Vehicles

Challenges to Security in Space (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence Agency, January 2019).

China has developed a “quick response” SLV to increase its attractiveness as a commercial small satellite launch provider and to rapidly reconstitute LEO space capabilities, which could support

p. 17

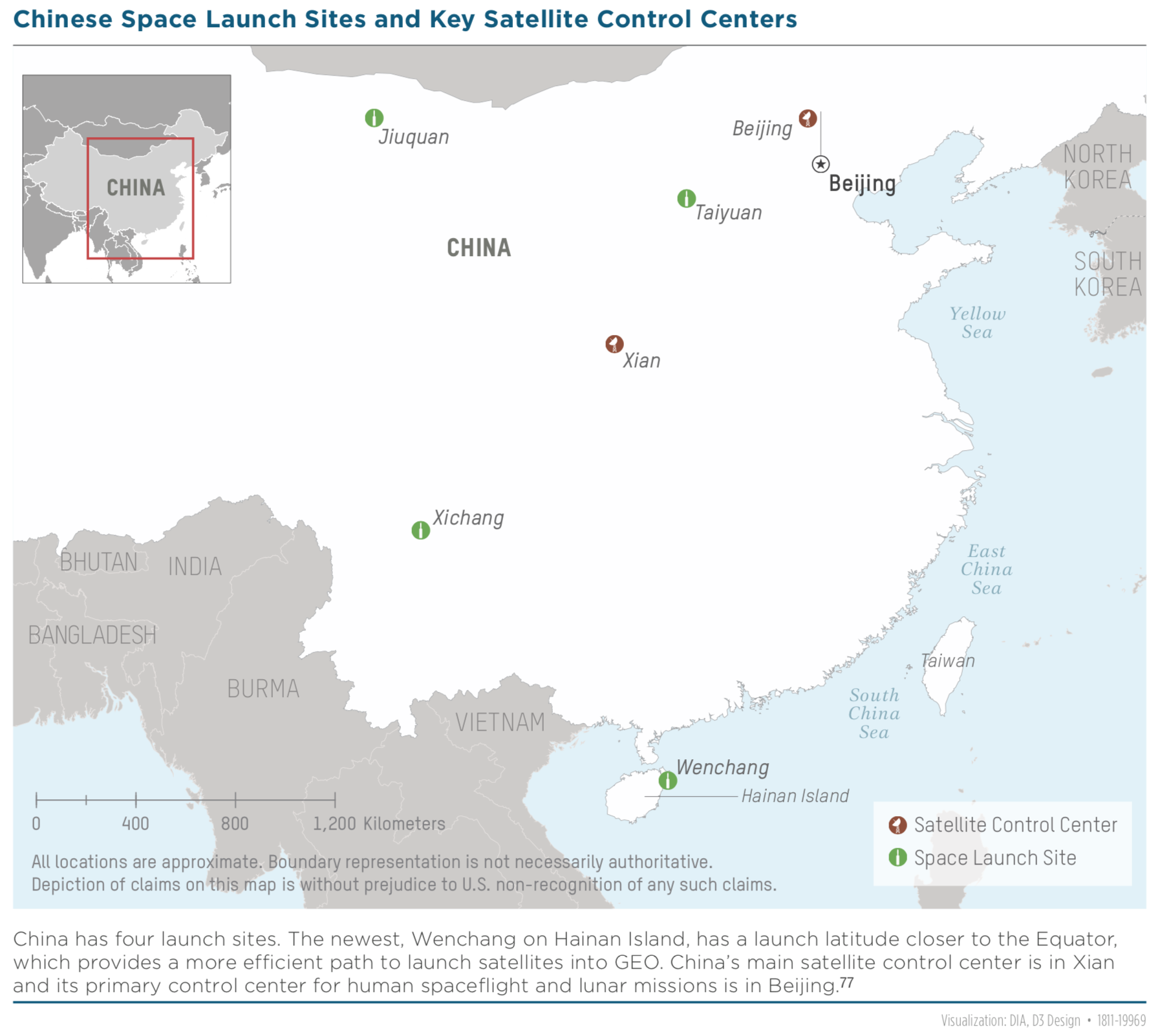

Exhibit: Chinese Space Launch Sites and Key Satellite Control Centers

Challenges to Security in Space (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence Agency, January 2019).

military operations during a conflict or civilian response to disasters. Compared to medium- and heavy-lift SLVs, these quick response SLVs are capable of expedited launch campaigns because they are transportable via road or rail and can be stored launch-ready for longer periods. Cur- rently, due to their limited size, quick response SLVs such as the KZ-1, LM-6, and LM-11 are only capable of launching relatively small payloads into LEO.78,79,80

p. 18

Human Spaceflight and Space Exploration

In 2003, China became the third country to achieve independent human spaceflight, when it successfully orbited the crewed Shenzhou-5 spacecraft, followed by space laboratory Tiangong-1 and -2 launches in 2011 and 2016, respectively. By 2022, China intends to assemble and operate a permanently inhabited, modular space station that can host Chinese and foreign payloads and astronauts.81,82

[Caption: In December 2013, China conducted the first “soft-landing” on the Moon since 1976.83 The lunar rover, Yutu, took this image of the Chang’e-3 lunar lander that month.]

China is also the third country to have landed a rover on the Moon and performed the first-ever landing on the lunar far side with its Chang’e-4 rover and lander in January 2019.84,85 Because it is not possible to communicate directly with objects on the far side of the Moon, China launched a lunar relay satellite in May 2018 to enable communication between the Chang’e-4 and the Earth.86,87

Additionally, China announced plans in March 2018 to assemble a robotic research station on the Moon by 2025 and has started establishing the foundation for a human lunar exploration program to put astronauts on the Moon in the mid-2030s.88,89

ISR, Navigation, and Communications Capabilities

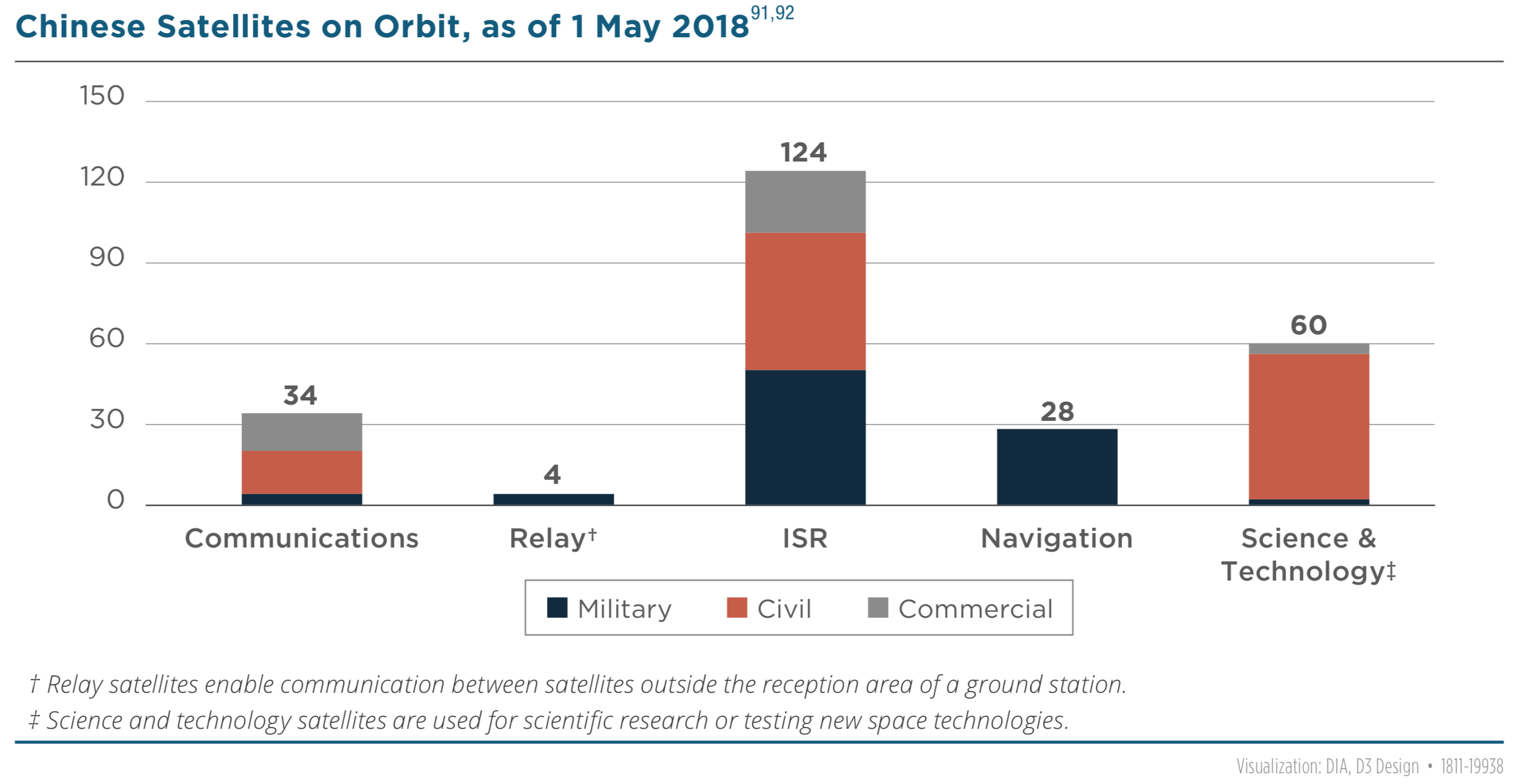

China employs a robust space-based ISR capability designed to enhance its worldwide situational awareness. Used for military and civil remote sensing and mapping, terrestrial and maritime surveillance, and military intelligence collection, China’s ISR satellites are capable of providing electro-optical and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery, as well as electronic intelligence and signals intelligence data.90

Exhibit: Chinese Satellites on Orbit, as of 1 May 2018

Challenges to Security in Space (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence Agency, January 2019).

p. 19

As of May 2018, the Chinese ISR and remote sensing satellite fleet contains more than 120 systems—a quantity second only to the United States.94

The PLA owns and operates about half of these ISR systems, most of which could support monitoring, tracking, and targeting of U.S. and allied forces worldwide, especially throughout the Indo-Pacific region. These satellites also allow the PLA to maintain situational awareness of potential regional flashpoints, including the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, and the South China Sea.95,96,97

China also owns and operates over 30 communications satellites, with 4 dedicated to military use.98 China produces its military-dedicated satellites domestically and its civil communications satellites incorporate off-the-shelf commercially manufactured components.99

Additionally, China has embarked on several ambitious plans to propel itself to the forefront of the global satellite communications (SATCOM) industry.100,101,102 China is testing multiple next-generation capabilities, such as quantum-enabled communications, which could supply the means to field highly secure communications systems.103

China is continuing to improve its indigenous satellite navigation constellation. China offers regional PNT services and achieved initial operating capability of its worldwide, next-generation BeiDou constellation in 2018.104,105 In addition to providing PNT, the BeiDou constellation offers unique capabilities, including text messaging and user tracking through its short messaging service, to enable mass communications between BeiDou users and provide additional C2 capabilities for the PLA.106,107

p. 20

China also exports its satellite technology globally, including its indigenously-developed communications satellites. China intends to provide SAT- COM support to users worldwide and has plans to develop at least three new communications constellations.108,109,110 China also intends to use its BeiDou constellation to offer additional services and incentives to countries taking part in the “Belt and Road Initiative.” BeiDou supports that initiative’s emphasis on building strong economic ties with other countries and shaping their interests to align with China’s.111,112

Counterspace Capabilities

Space Situational Awareness. China has a robust network of space surveillance sensors capable of searching, tracking, and characterizing satellites in all Earth orbits. This network includes a variety of tele- scopes, radars, and other sensors that allow China to support missions including intelligence collection, counterspace targeting, ballistic missile early warning, spaceflight safety, satellite anomaly resolution, and space debris monitoring.113,114

[Caption: This Chinese Yuan Wang space tracking ship, which supports space launch operations from positions in the Pacific, is part of China’s SSA network.115]

Electronic Warfare. The PLA considers EW capabilities key assets for modern warfare and its doctrine emphasizes using EW weapons to suppress or deceive enemy equipment.116 The PLA routinely incorporates jamming and anti-jamming techniques against multiple communication, radar systems, and GPS satellite systems in exercises.117 China continues to develop jammers dedicated to targeting SAR aboard military reconnaissance platforms, including LEO satellites.118,119 Additionally, China is developing jammers to target SATCOM over a range of frequency bands, including military protected extremely high frequency communications.120,121

Directed Energy Weapons. China likely is pursuing laser weapons to disrupt, degrade, or damage satellites and their sensors and possibly already has a limited capability to employ laser systems against satellite sensors. China likely will field a ground-based laser weapon that can counter low-orbit space-based sensors by 2020, and by the mid-to-late 2020s, it may field higher power systems that extend the threat to the structures of non-optical satellites.122,123,124,125,126

Cyberspace Threats. China emphasizes offensive cyberspace capabilities as key assets for integrated warfare and could use its cyberwarfare capabilities to support military operations against space-based assets.127,128 For example, the PLA could employ its cyberattack capabilities to establish information dominance in the early stages of a conflict to constrain an adversary’s actions, or slow its mobilization

Chinese International SSA Cooperation

China leads the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization—a multilateral organization with rotating leadership whose members include emerging spacefaring nations such as Iran—that oversees a space surveillance project known as the Asia-Pacific Ground-Based Optical Space Object Observation System (APOSOS). As part of the project, China provided three 15 cm telescopes to Peru, Pakistan, and Iran that are capable of tracking objects in LEO and GEO. All tasking information and subsequent observation data collected is funneled through the Chinese Academy of Science’s National Astronomical Observatory of China. APOSOS has near full coverage of GEO and LEO. The organization is planning on improving optical system capabilities, coverage, and redundancy.129,130

p. 21

and deployment by targeting network-based command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR), logistics, and commercial activities.

The PLA also plays a role in cyberespionage targeting foreign space entities, consistent with broader state-sponsored industrial and technical espionage to increase the level of technologies and expertise available to support military research and development and acquisition. The PLA unit responsible for conducting signals intelligence has supported cyberespionage against U.S. and European satellite and aerospace industries since at least 2007.131,132

Orbital Threats. China is developing sophisticated on-orbit capabilities, such as satellite inspection and repair, at least some of which could also function as a weapon. China has launched multiple satellites to conduct scientific experiments on space maintenance technologies and it is conducting space debris cleanup research.133,134,135,136

Kinetic Energy Threats. The PLA has an operational ground-based ASAT missile intended to target LEO satellites. China has also formed military units that have begun training with ASAT missiles.137,138,139

Other Counterspace Technology Development.

China probably intends to pursue additional ASAT weapons capable of destroying satellites up to GEO. In 2013, China launched an object into space on a ballistic trajectory with a peak altitude above 30,000 km. No new satellites were released from the object, and the launch profile was inconsistent with traditional SLVs, ballistic missiles, or sounding rocket launches for scientific research.142

[Caption: China’s 2007 test of its ground-based ASAT missile destroyed one of its own defunct satellites in LEO.140,141 The graphic depicts the orbits of trackable debris generated by the test 1 month after the event. The white line represents the International Space Station’s orbit.]