New CRS Report with China Content: “Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress”

Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress R41153 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 4 November 2020).

Click here to download a cached copy.

KEY CHINA-RELATED TEXT:

p. 29

China in the Arctic

China’s Growing Activities in the Arctic

China’s diplomatic, economic, and scientific activities in the Arctic have grown steadily in recent years, and have emerged as a major topic of focus for the Arctic in a context of renewed great power competition. As noted earlier in this report, China was one of six non-Arctic states that were approved for observer status by the Arctic Council in 2013.90 China in recent years has engaged in growing diplomatic activities with the Nordic countries, and has increased the size of its diplomatic presences in some of them. China has also engaged in growing economic discussions with Iceland and also with Greenland, a territory of Denmark that might be moving toward eventual independence.91

China has a Ukrainian-built polar-capable icebreaker, Xue Long (Snow Dragon), that in recent years has made several transits of Arctic waters—operations that China describes as research expeditions. 92 A second polar-capable icebreaker (the first that China has built domestically), named Xue Long 2, entered service in 2019. 93 China in 2018 announced an intention to build a 30,000-ton (or possibly 40,000-ton) nuclear-powered icebreaker,94 which would make China only the second country (following Russia) to operate a nuclear-powered icebreaker. In December 2019, however, it was reported that China’s third polar-capable icebreaker might instead be built as a 26,000-ton, conventionally powered ship.95 (By way of comparison, the new polar icebreakers being built for the U.S. Coast Guard are to displace 22,900 tons each.) Like several other nations, China has established a research station in the Svalbard archipelago. China maintains a second research station in Iceland.

China in January 2018 released a white paper on China’s Arctic policy that refers to China as a “near-Arctic state.” 96 (China’s northernmost territory, northeast of Mongolia, is at about the same

***

90 The other five were India, Italy, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. For the full list of observers and when they were approved for observer status, see Arctic Council, “Observers,” accessed July 20, 2018, at https://arctic-council.org/ index.php/en/about-us/arctic-council/observers.

91 See, for example, Marc Lanteigne, “Greenland’s Widening World,” Over the Circle, March 28, 2020; Marco Volpe, “The Tortuous Path of China’s Win-Win Strategy in Greenland,” Arctic Institute, March 24, 2020; Marc Lanteigne, “Stumbling Block: China-Iceland Oil Exploration Reaches an Impasse,” Over the Circle, January 24, 2018. “Greenland Plans Office in Beijing to Boost Trade Ties with China,” Reuters, July 18, 2018.

92 See, for example, “Icebreaker Sets Sail on China’s 9th Arctic Research Expedition,” Xinhua, July 20, 2018; “China Begins 9th Arctic Expedition to Help Build ‘Polar Silk Road,’” Global Times, July 20, 2018.

93 “China Delivers First Self-Built Icebreaking Research Vessel,” People’s Daily Online, July 12, 2019; Kamaran Malik, “China Launches First Locally-made Icebreaker,” Asia Times, July 11, 2019.

94 See Trym Aleksander Eiterjord, “Checking in on China’s Nuclear Icebreaker,” Diplomat, September 5, 2019; Thomas Nilsen, “Details of China’s Nuclear-Powered Icebreaker Revealed,” Barents Observer, March 21, 2019; Zhao Yusha, “China One Step Closer to Nuke-Powered Aircraft Carrier with Cutting-Edge Icebreaker Comes on Stream,” ChinaMil.com, June 23, 2018; China Daily, “China’s 1st Nuclear-Powered Icebreaker in the Pipeline,” People’s Daily Online, June 25, 2018; Kyle Mizokami, “China Is Planning a Nuclear-Powered Icebreaker,” Popular Mechanics, June 25, 2018; China Military Online, “Why Is China Building a 30,000-Ton Nuclear-Powered Icebreaker?” ChinaMil.com, June 30, 2018.

95 Malte Humpert, “China Reveals Details of a Newly Designed Heavy Icebreaker,” Arctic Today, December 17, 2019.

96 “Full Text: China’s Arctic Policy,” Xinhua, January 26, 2018, accessed July 20, 2018, at http://www.xinhuanet.com/ english/2018-01/26/c_136926498.htm. The white paper states that “China is an important stakeholder in Arctic affairs. Geographically, China is a ‘Near-Arctic State’, one of the continental States that are closest to the Arctic Circle. The natural conditions of the Arctic and their changes have a direct impact on China’s climate system and ecological environment, and, in turn, on its economic interests in agriculture, forestry, fishery, marine industry and other sectors. China is also closely involved in the trans-regional and global issues in the Arctic, especially in such areas as climate

p. 30

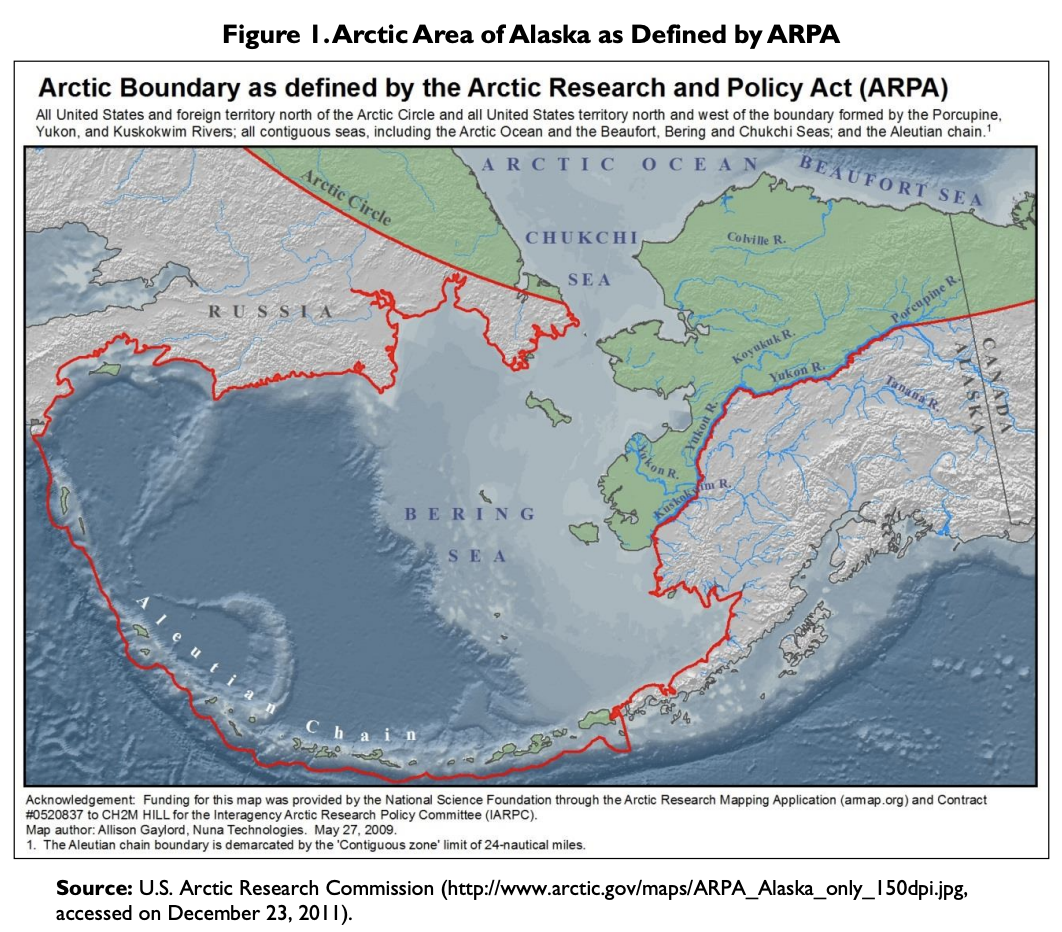

latitude as the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, which, as noted earlier in this report, the United States includes in its definition of the Arctic for purposes of U.S. law.) The white paper refers to transArctic shipping routes as the Polar Silk Road, and identifies these routes as a third major transportation corridor for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s major geopolitical initiative, first announced by China in 2013, to knit Eurasia and other regions together in a Chinese-anchored or Chinese-led infrastructure and economic network.97

China appears to be interested in using the NSR to shorten commercial shipping times between Europe and China98 and perhaps also to reduce China’s dependence on southern sea routes (including those going to the Persian Gulf) that pass through the Strait of Malacca—a maritime choke point that China appears to regard as vulnerable to being closed off by other parties (such as the United States) in time of crisis or conflict.99 China reportedly reached an agreement with Russia on July 4, 2017, to create an “Ice Silk Road,” 100 and in June 2018, China and Russia agreed to a credit agreement between Russia’s Vnesheconombank (VEB) and the China Development Bank that could provide up to $9.5 billion in Chinese funds for the construction of

***

change, environment, scientific research, utilization of shipping routes, resource exploration and exploitation, security, and global governance. These issues are vital to the existence and development of all countries and humanity, and directly affect the interests of non-Arctic States including China.”

Somewhat similarly, France’s June 2016 national roadmap for the Arctic refers to France as a “polar nation.” (Republique Francaise, Ministere des Affaires Etrangeres et du Developpement International, The Great Challenge of the Arctic, National Roadmap for the Arctic, June 2016, 60 pp.) The document states on page 9 that “France has established itself over the last three centuries as a polar nation, with a strong tradition of expeditions and exploration, and permanent research bases at the poles,” and on page 17 that “[b]uilding on its long-standing tradition of exploration and expeditions in high latitudes, France has carved out its place as a polar nation over the last three centuries. France has permanent scientific bases in the Arctic and in Antarctica.” It can also be noted that the northernmost part of mainland France, next to Belgium and across the Strait of Dover from England, is almost as far north as the more southerly parts of the Aleutian Islands.

Also somewhat similarly, a November 2018 UK parliamentary report refers to the UK as a “near-Arctic neighbour.” The report states the following: “While the UK is not an Arctic state, it is a near-Arctic neighbour. The UK’s weather system is profoundly affected by changes in the Arctic’s climate and sea currents. The UK has been an Observer to the Arctic Council since 1998.” (United Kingdom, House of Commons, Environmental Audit Committee, The Changing Arctic, Twelfth Report of Session 2017-19, November 29, 2018, p. 3. [Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report, Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed November 6, 2018]. See also pp. 6, 29, and 32.)

See also Eva Dou, “A New Cold War? China Declares Itself a ‘Near-Arctic State,’ Wall Street Journal, January 26, 2018; Grant Newsham, “China As A ‘Near Arctic State’—Chutzpah Overcoming Geography,” Asia Times, January 30, 2018.

97 See, for example, Nima Khorrami, “Data Hunting in Subzero Temperatures: The Arctic as a New Frontier in Beijing’s Push for Digital Connectivity,” Arctic Institute, August 4, 2020; Marc Lanteigne, “The Twists and Turns of the Polar Silk Road,” Over the Circle, March 15, 2020; Zhang Chun, “China’s ‘Arctic Silk Road,’” Maritime Executive, January 10, 2020; Sabena Siddiqui, “Arctic Ambition: Beijing Eyes the Polar Silk Road,” Asia Times, October 25, 2018. The BRI’s other two main corridors, which were announced at the outset of the BRI, are a land corridor that runs east to west across the middle of Eurasia—the “belt” in BRI—and a sea corridor called the Maritime Silk Road that passes through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean to the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea—the “road” in BRI. For more on the BRI, see CRS In Focus IF10273, China’s “One Belt, One Road”, by Susan V. Lawrence and Gabriel M. Nelson. See also Atle Staalesen, “Chinese Money for Northern Sea Route,” Barents Observer, June 12, 2018. See also Lin Boqiang, “China Can Support Arctic Development as Part of B&R,” Global Times, August 9, 2018.

98 See, for example, Eduardo Baptista, “China ‘More Than Other States’ Looks to Future Sea Route Through ResourceRich Arctic, Study Says,” South China Morning Post, September 22, 2020.

99 See, for example, Jonathan Hall, “Arctic Enterprise: The China Dream Goes North,” Journal of Political Risk, September 2019. 100 Xinhua, “China, Russia agree to jointly build ‘Ice Silk Road,’” Xinhuanet, July 4, 2017.

p. 31

select infrastructure projects, including in particular projects along the NSR.101 In September 2013, the Yong Shen, a Chinese cargo ship, became the first commercial vessel to complete the voyage from Asia to Rotterdam via the NSR.102

China has made significant investments in Russia’s Arctic oil and gas industry, particularly the Yamal natural gas megaproject located on Russia’s Yamal Peninsula in the Arctic.103 China is also interested in mining opportunities in the Arctic seabed, in Greenland, and in the Canadian Arctic.104 Given Greenland’s very small population, China may view Greenland as an entity that China can seek to engage using an approach similar to ones that China has used for engaging with small Pacific and Indian Ocean island states.105 China may also be interested in Arctic fishing grounds.

China’s growing activities in the Arctic may also reflect a view that as a major world power, China should, like other major world powers, be active in the polar regions for conducting research and other purposes. (Along with its growing activities in the Arctic, China has recently increased the number of research stations in maintains in the Antarctic.)

Particularly since China published its Arctic white paper in January 2018, observers have expressed curiosity or concern about China’s exact mix of motivations for its growing activities in the Arctic, and about what China’s ultimate goals for the Arctic might be.106

101 Atle Staalesen, Chinese Money for Northern Sea Route,” Barents Observer, June 12, 2018. See also Xie Wenwen (Caixin Globus), “For Chinese Companies, Investment I Arctic Infrastructure Offers Both Opportunities and Challenges,” Arctic Today, June 17, 2019.

102 “Chinese Make First Successful North Sea Route Voyage,” The Arctic Journal, September 12, 2013. See also Malte Humpert, “Chinese Shipping Company COSCO To Send Record Number of Ships Through Arctic,” High North News, June 13, 2019; Marex (Maritime Executive), “Russia and China Sign Arctic Deal,” Maritime Executive, June 8, 2019.

103 See, for example, Malte Humpert (High North News), “China Acquires 20 Percent Stake in Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 Project,” Arctic Today, April 30, 2019; Ernesto Gallo and Giovanni Biava, “A New Energy Frontier Called ‘Polar Silk Road,’” China Daily, April 12, 2019.

104 See, for example, Marc Montgomery, “China’s Effort to Buy an Arctic Gold Mine Raises Many Concerns,” Radio Canada International, August 10 (updated August 11), 2020; Vipal Monga, “China’s Move to Buy Arctic Gold Mine Draws Fire in Canada,” Wall Street Journal, July 26, 2020; Mingming Shi and Marc Lanteigne, “A Cold Arena? Greenland as a Focus of Arctic Competition,” Diplomat, June 10, 2019; Nadia Schadlow, “Why Greenland Is Really About China,” The Hill, August 28, 2019; Marc Lanteigne and Mingming Shi, “China Steps up Its Mining Interests in Greenland,” Diplomat, February 12, 2019; John Simpson, “How Greenland Could Become China’s Arctic Base,” BBC, December 18, 2018; Marc Lanteigne, “Do Oil and Water Mix? Emerging China-Greenland Resource Cooperation,” Over the Circle, November 2, 2018; Martin Breum, “China and the US Both Have Strategic Designs for Greenland,” Arctic Today, October 17, 2018; Mia Bennett, “The Controversy over Greenland Airports Shows China Isn’t Fully Welcome in the Arctic—Yet,” Arctic Today, September 13, 2018; Mingming Shi and Marc lanteigne, “The (Many0 Roles of Greenland in china’s Developing Arctic Policy,” Diplomat, March 30, 2018; Miguel Martin, “China in Greenland: Mines, Science, and Nods to Independence,” China Brief, March 12, 2018.

105 For further discussion of China-Greenland relations, see Kevin McGwin, “Greenland Lawmakers Will Consider Opening an East Asia Office,” Arctic Today, April 6, 2020.

106 See, for example, Nengye Liu, “Why China Needs an Arctic Policy 2.0, It Is Time for China to Shed Light on Which Kind of Order It Would Like to Construct in the Arctic Using Its Rising Power,” Diplomat, October 22, 2020; Mary Kay Magistad, “China’s Arctic Ambitions Have Revived US Interest in the Region,” The World, October 12, 2020; Thomas Ayres, “Op-ed | China’s Arctic Gambit a Concern for U.S. Air and Space Forces,” Space News, October 5, 2020; Marco Giannangeli, “China Expanding into Melting Arctic in Major Military Threat to West,” Express (UK), August 2, 2020; Joel Gehrke, “China Aims to Control Ports and Shipping Lanes in Europe and the Arctic,” Washington Examiner, July 1, 2020; Ties Dams, Louise van Schaik, and Adaja Stoetman, Presence Before Power, China’s Strategy in Iceland and Greenland, Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael), June 2020; Trine Jonassen, “Rejects Notion that China is a Threat to the Arctic,” High North News, May 27, 2020 (which reports remarks by State Secretary Audun Halvorsen of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs); Swee Lean Collin Koh, “China’s Strategic Interest in the Arctic Goes Beyond Economics,” Defense News, May 12, 2020; Marc Lanteigne, “Identity and

p. 32

Arctic States’ Response

The renewal of great power competition underscores a question for the Arctic states regarding whether and how to respond to China’s growing activities in the Arctic. China’s growing activities in the Arctic could create new opportunities for cooperation between China and the Arctic states.107 They also, however, have the potential for posing challenges to the Arctic states in terms of defending their own interests in the Arctic.108 For U.S. policymakers, a general question is how to integrate China’s activities in the Arctic into the overall equation of U.S.-China relations, and whether and how, in U.S. policymaking, to link China’s activities in the Arctic to its activities in other parts of the world. Some observers see potential areas for U.S.-Chinese cooperation in the Arctic; 109 others view the Arctic as emerging arena of U.S.-China strategic competition; 110 still others view the Arctic as a mixed situation involving potential elements of cooperation and competition.111

***

Relationship-Building in China’s Arctic Diplomacy,” Arctic Institute, April 28, 2020; Nick Solheim, “Time to Crush China’s Arctic Influence,” Spectator, April 20, 2020; Yun Sun, “Defining the Chinese Threat in the Arctic,” Arctic Institute, April 7, 2020; Sanna Kopra, “China and its Arctic Trajectories: The Arctic Institute’s China Series 2020,” Arctic Institute, March 17, 2020; Atle Staalesen, “China’s Ambassador Brushes Off Allegations His Country Is Threat in Arctic,” Barents Observer, February 16, 2020; Luke Coffey, “China’s Increasing Role in the Arctic,” Heritage Foundation, February 11, 2020; Jacquelyn Chorush, “Is China Really Threatening Conquest in the Arctic?” High North News, January 6, 2020; Mike Green, “China’s Arctic Ambitions Spark Fear Among U.S. Military Leaders,” Washington Times, December 26, 2019; Ryan D. Martinson, “The Role of the Arctic in Chinese Naval Strategy,” China Brief, December 20, 2019; Anne-Marie Brady, “Facing Up to China’s Military Interests in the Arctic,” China Brief, December 10, 2019; Jacquelyn Chorush, “Concerns About China in the Arctic Dominate Canadian Security Forum,” High North News, December 4, 2019; Nikolaj Skydsgaard and Jacob Gronholt-Pedersen, “China Mixing Military and Science in Arctic Push: Denmark,” Reuters, November 29, 2019; Lyle J. Goldstein, “What Does China Want with the Arctic?” National Interest, September 7, 2019; Malte Humpert, Explaining China’s Arctic Interests, the U.S.’ Efforts to Re-Engage, and the Growing Split Between the Two Countries,” High North News, September 6, 2019; Malte Humpert, “China Looking to Expand Satellite Coverage in Arctic, Experts Warn Of Military Purpose,” High North News, September 4, 2019; “Mark Rosen, “Will China Freeze America Out of the Arctic?” National Interest, August 14, 2019; Heljar Havnes and Johan Martin Seland, “The Increasing Security Focus in China’s Arctic Policy,” Arctic Institute, July 16, 2019.

107 See, for example, Atle Staalesen, “As Arctic Talks Move to China, Leaders Downplay Divides,” Barents Observer, May 11, 2019; Thomas Nilsen, “China Seeks a More Active Role in the Arctic,” Barents Observer, May 11, 2019; Nathan Vanderklippe, “Agreeing on the Arctic: Amid Dispute, Canada Sides with China over the U.S. on How to Manage the North,” Globe and Mail, May 10, 2019; “China and Finland: The Ice Road Cometh?” Over the Circle, March 17, 2020; Nong Hong, “Arctic Ambitions of China, Russia—and Now the US—Need Not Spark a Cold War,” South China Morning Post, March 11, 2019.

108 See, for example, Mingming Shi and Marc Lanteigne, “China’s Central Role in Denmark’s Arctic Security Policies,” Diplomat, December 08, 2019; Humphrey Hawksley, “Nordic Nations Can Stand Up to China in the Arctic,” Nikkei Asian Review, June 13, 2019; Thomas Nilsen, “‘We Must Be Prepared for Clearer Chinese Presence in Our Neighborhood’; Chief of Norway’s Military Intelligence Service, Lieutenant General Morten Haga Lunde, Highlighted Chinese, Russian Arctic Cooperations in His Annual Focus Report,” Barents Observer, February 11, 2019.

109 See, for example, James Stavridis, “Can the U.S. and China Cooperate? Sure,” Bloomberg, July 31, 2020; Stephen Delaney, “The United States Must Work with China to Ensure Freedom of Navigation in the Arctic,” Global Security Review, September 6, 2019; Alison McFarland, “Arctic Options: Why America Should Invest in a Future with China,” National Interest, September 30, 2018.

110 See, for example, Michael Krull, “The Arctic: China Wants It; We Need to Deny Them,” American Military News, September 8, 2020; Simone McCarthy, “Trade, tech … and Now the Arctic? The Next Frontier in the China-US Struggle for Global Control,” South China Morning Post, January 14, 2020 (ellipse as in the article’s title); Chen Zinan, “To Keep Hegemony, US Trying to Obstruct China’s Rights in Arctic,” Global Times, December 25, 2019.

111 See, for example, Laura Zhou, “US Admiral Warns of Risk of ‘Bogus’ Chinese Claims in Arctic,” South China Morning Post, June 28 (updated June 29), 2020.

p. 33

A specific question could be whether to impose punitive costs on China in the Arctic for unwanted actions that China takes elsewhere. As one potential example of such a cost-imposing action, U.S. policymakers could consider moving to suspend China’s observer status on the Arctic Council112 as a punitive cost-imposing measure for unwanted Chinese actions in the South China

***

112 Paragraph 37 of the Arctic Council’s rules of procedure states the following:

Once observer status has been granted, Observers shall be invited to the meetings and other activities of the Arctic Council unless SAOs [Senior Arctic Officials] decide otherwise. Observer status shall continue for such time as consensus exists among Ministers. Any Observer that engages in activities which are at odds with the Council’s [Ottawa] Declaration [of September 19, 1996, establishing the Council] or these Rules of Procedure shall have its status as an Observer suspended.

Paragraph 5 of Annex II of the Arctic Council’s rules of procedure—an annex regarding the accreditation and review of observers—states the following:

Every four years, from the date of being granted Observer status, Observers should state affirmatively their continued interest in Observer status. Not later than 120 days before a Ministerial meeting where Observers will be reviewed, the Chairmanship shall circulate to the Arctic States and Permanent Participants a list of all accredited Observers and up-to-date information on their activities relevant to the work of the Arctic Council. (Arctic Council, Arctic Council Rules of Procedure, p. 9. The document was accessed July 26, 2018, at https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/940.

Paragraph 4.3 of the Arctic Council’s observer manual for subsidiary bodies states in part

Observer status continues for such time as consensus exists among Ministers. Any Observer that engages in activities which are at odds with the Ottawa Declaration or with the Rules of Procedure will have its status as an Observer suspended. (Arctic Council. Observer Manual for Subsidiary Bodies, p. 5. The document was accessed July 26, 2018, at https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/939.)

A 2013 journal article states

The quest of China and other Asian powers for formal representation at the Arctic Council created an issue in its own right for which other sub-regional groups could offer no guidance. It was adjudicated positively at the May 2013 Ministerial meeting only after elaborate measures had been taken to clarify and circumscribe the roles of observers, including a provision for their possible expulsion. (Alyson JK Bailes, “Understanding The Arctic Council: A ‘Sub-Regional’ Perspective,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Vol. 15, Issue 2, 2013: 48. Accessed September 10, 2020, at https://jmss.org/article/view/58094.)

A 2014 law review article states that

the main criterion stipulated in the rules regarding admitting observers is that the non-Arctic states or other organizations must be able to contribute to the Council’s work. After looking at China’s efforts and expenditures in the Arctic, it is clear that it can contribute to the Council’s work. If, however, the Council finds any activities at odds with the Council’s Declaration, it can suspend admission.

(Brianna Wodiske, “Preventing the Melting of the Arctic Council: China as a Permanent Observer and What It Means for the Council and the Environment,” Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review, Vol. 315, Issue 2, 2014 (November 1, 2014): 320. Accessed September 10, 2020, at https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol36/iss2/5/.)

An April 2015 article states

Access to the Arctic Council is not of indeterminate duration once observer status has been granted. The status persists only as long as none of the Arctic states objects. Observers themselves further have to renew their interest in maintaining the status every four years, and will have their performance reviewed. Having said that, in its almost twenty-year history, the Arctic Council has to date never revoked an observer status. In the light of ever more interested parties willing to join the Council, it is high time for the Arctic Council to reconsider this practice.

(Sebastian Knecht, “New Observers Queuing Up: Why the Arctic Council Should Expand—And

p. 34

Sea.113 As mentioned earlier, in a May 6, 2019, speech in Finland, Secretary of State Pompeo stated (emphasis added)

The United States is a believer in free markets. We know from experience that free and fair competition, open, by the rule of law, produces the best outcomes.

But all the parties in the marketplace have to play by those same rules. Those who violate those rules should lose their rights to participate in that marketplace. Respect and transparency are the price of admission.

And let’s talk about China for a moment. China has observer status in the Arctic Council, but that status is contingent upon its respect for the sovereign rights of Arctic states. The U.S. wants China to meet that condition and contribute responsibly in the region. But China’s words and actions raise doubts about its intentions.114

In February 2019, it was reported that the United States in 2018 had urged Denmark to finance the construction of airports that China had offered to build in Greenland, so as to counter China’s attempts to increase its presence and influence there.115 In May 2019, the State Department announced plan for establishing a permanent diplomatic presence in Greenland, 116 and on June 2020, the State Department formally announced the reopening of the U.S. consulate in Greenland’s capital of Nuuk.117 In April 2020, the U.S. government announced $12.1 million

***

Expel,” Arctic Institute, April 20, 2015.)

A paper prepared in 1999 (i.e., long before the 2013 Arctic Council deliberations discussed above) and posted at a State Department website states

the rules provide that “[a]ny Observer that engages in activities which are at odds with the Council’s Declaration shall have its status as an Observer suspended.” In practice this means that, since all decisions are taken by consensus, suspension of such an Observer during the period between ministerials would require the concurrence of all the Arctic states that the Observer was engaging in activities “at odds with the Council’s Declaration.”

(Evan Bloom, “Establishment of the Arctic Council,” undated, accessed September 10, 2020, at https://2009-2017.state.gov/e/oes/ocns/opa/arc/ac/establishmentarcticcouncil/index.htm, which states “The following paper was authored by Evan Bloom in July 1999 when serving as an attorney in the Office of the Legal Adviser at the U.S. Department of State. Mr. Bloom is now the Director of the Office of Oceans and Polar Affairs for the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs at the U.S. Department of State.”) See also Kevin McGwin, “After 20 years, the Arctic Council Reconsiders the Role of Observers,” Arctic Today, October 24, 2018.

113 For more on China’s actions in the South China Sea and their potential implications for U.S. interests, see CRS Report R42784, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress.

114 State Department, “Looking North: Sharpening America’s Arctic Focus, Remarks, Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State, Rovaniemi, Finland, May 6, 2019,” accessed August 23, 2019, at https://www.state.gov/looking-northsharpening-americas-arctic-focus/.

115 Drew Hinshaw and Jeremy Page, “How the Pentagon Countered China’s Designs on Greenland; Washington Urged Denmark to Finance Airports that Chinese Aimed to Build on North America’s Doorstep,” Wall Street Journal, February 10, 2019. See also Marc Lanteigne, “Greenland’s Airport Saga: Enter the US?” Over the Circle, September 18, 2018; Marc Lanteigne, “Greenland’s Airports: A Balance between China and Denmark?” Over the Circle, June 15, 2018; Arne Finne (translated by Elisabeth Bergquist), “Intense Airport Debate in Greenland,” High North News, May 30, 2018.

116 State Department, “Secretary Pompeo Postpones Travel to Greenland,” Press Statement, Morgan Ortagus, Department Spokesperson, May 9, 2019. See also Krestia DeGeorge, “US State Department Announces Plans for a Diplomatic Presence in Greenland,” Arctic Today, May 9, 2019; Morten Soendergaard Larsen and Robbie Gramer, “Trump Puts Down New Roots in Greenland,” Foreign Policy, November 8, 2019.

117 See, for example, Lauren Meier and Guy Taylor, “U.S. Reopens Consulate in Greenland Amid Race for Arctic Supremacy,” Washington Times, June 10, 2020.

p. 35

economic aid package for Greenland that the Trump Administration presented as a U.S. action done in a context of Chinese and Russian actions aimed at increasing their presence and influence in Greenland.118 Some observers argue that a desire to preclude China (or Russia) from increasing its presence and influence in Greenland may have been one of the reasons why President Trump in August 2019 expressed an interest in the idea of buying Greenland from Denmark.119

For Russia, the question of whether and how to respond to China’s activities in the Arctic may pose particular complexities. On the one hand, Russia is promoting the NSR for use by others, in part because Russia sees significant economic opportunities in offering icebreaker escorts, refueling posts, and supplies to the commercial ships that will ply the waterway. In that regard, Russia presumably would welcome increased use of the route by ships moving between Europe and China. More broadly, Russia and China have increased their cooperation on security and other issues in recent years, in no small part as a means of balancing or countering the United States in international affairs, and Russian-Chinese cooperation in the Arctic (including China’s investment in Russia’s Arctic oil and gas industry) can both reflect and contribute to that cooperation.120 The U.S. Department of Defense states that China’s “expanding Arctic

***

118 For State Department briefings about the economic aid package, see State Department, Briefing On the Road to Nuuk: Economic Cooperation, Special Briefing, Michael J. Murphy, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, Francis R. Fannon, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Energy Resources, Jonathan Moore, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, Gretchen Birkle, USAID Deputy Assistant Administrator, May 15, 2020; and State Department, Briefing on the Administration’s Arctic Strategy, Special Briefing, Office of the Spokesperson, April 23, 2020.

For press reports about the economic aid package, see, for example, Jessica Donati, “U.S. Offers Aid to Greenland to Counter China, Russia,” Wall Street Journal, April 23, 2020; Carol Morello, “U.S. to Give Aid to Greenland, Open Consulate in Bid to Counter Russia and China,” Washington Post, April 23, 2020; Jacob Gronholt-Pedersen and Humeyra Pamuk, “US Extends Economic Aid to Greenland to Counter China, Russia in Arctic,” Reuters, April 23, 2020; Laura Kelly, “US Announces New Funding for Greenland in Push for Stronger Arctic Presence,” The Hill, April 23, 2020; Paul McCleary, “Battle For The Arctic: Russia Plans Nuke Icebreaker, US Counters China In Greenland,” Breaking Defense, April 23, 2020; Katrina Manson and Richard Milne, “US Financial Aid for Greenland Sparks Outrage in Denmark,” Financial Times, April 23, 2020; Alex Fang, “US Rejects China’s ‘Near-Arctic State’ Claim in New Cold War; Washington to Open Consulate in Greenland and Give Economic Aid,” Nikkei Asian Review, April 24 (updated April 26), 2020; Martin Breum, “The US Aid Package to Greenland Marks a New Chapter in a Long, Complex Relationship,” Arctic Today, April 29, 2020; Malte Humpert, “U.S. Says Arctic No Longer Immune from Geopolitics As It Invests $12m in Greenland,” High North News, April 29, 2020; Tom Parfitt, “US, China and Russia Wrestle for Influence in Greenland and the Arctic Circle,” Times (UK), May 1, 2020.

119 See, for example, Marc Lanteigne and Mingming Shi, “‘No Sale’: How Talk of a US Purchase of Greenland Reflected Arctic Anxieties,” Over the Circle, September 17, 2020; Stuart Lau, “Did China’s Growing Presence in Arctic Prompt Donald Trump’s Offer to Buy Greenland?” South China Morning Post, September 1, 2019; Nadia Schadlow, “Why Greenland Is Really About China,” The Hill, August 28, 2019; Daniel Lippman, “Trump’s Greenland Gambit Finds Allies Inside Government,” Politico, August 24, 2019; Seth Borenstein (Associated Press), “Icy Arctic Becomes Hot Property for Rival Powers,” Navy Times, August 22, 2019; Ragnhild Grønning, “Why Trump Is Looking to Buy Greenland—Even If It’s Not for Sale,” High North News, August 19, 2019. See also Caitlin Hu and Stephen Collinson, “Why Exactly Is the US So Interested in Greenland?” CNN, July 23, 2020. See also Tarisai Ngangura, “ExStaffer: Trump Wanted to Trade ‘Dirty’ Puerto Rico for Greenland,” Vanity Fair, August 19, 2020; Jacob Gronholt-Pedersen, “As the Arctic’s Attractions Mount, Greenland is a Security Black Hole,” Reuters, October 20, 2020; Gordon Lubold, “U.S. Holds Talks Over Economic, Security Arrangements With Greenland,” Wall Street Journal, October 28, 2020.

120 See, for example, Sherri Goodman and Yun Sun, “What You May Not Know About Sino-Russian Cooperation in the Arctic and Why it Matters,” Diplomat, August 13, 2020; Sarah Cammarata, “Russia and China Should Be Viewed as ‘One Alliance’ in the Arctic, U.K. Defense Official Warns,” Politico, June 6, 2020; Owen Matthews, “Putin Needs Xi More than China Needs Russia,” Spectator USA, May 25, 2020; Ken Moriyasu, “US Awakens to Risk of ChinaRussia Alliance in the Arctic,” Nikkei Asian Review, May 24, 2020; Christopher Weidacher Hsiung, “The Emergence of a Sino-Russian Economic Partnership in the Arctic?” Arctic Institute, May 19, 2020; Mario Giagnorio, “A Cold Relation: Russia, China and Science in the Arctic,” New Eastern Europe, March 25, 2020 (interview with Rasmus Gjedssø Bertelsen and Mariia Kobzeva); Alana Monteiro, “Strategic Partnership, Arctic-Style: How Russia and China

p. 36

engagement has created new opportunities for engagement between China and Russia. In April 2019, China and Russia established the Sino-Russian Arctic Research Center. In 2020, China and Russia plan to use this center to conduct a joint expedition to the Arctic to research optimal routes of the Northern Sea Route and the effects of climate change. The PRC will cover 75 percent of the expedition’s expenses.”121

On the other hand, Russian officials are said to be wary of China’s continued growth in wealth and power, and of how that might eventually lead to China becoming the dominant power in Eurasia, and to Russia being relegated to a secondary or subordinate status in Eurasian affairs relative to China. Increased use by China of the NSR could accelerate the realization of that scenario: As noted above, the NSR forms part of China’s geopolitical Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Some observers argue that actual levels of Sino-Russian cooperation in the Arctic are not as great as Chinese or Russian announcements about such cooperation might suggest.122

Linkages Between Arctic and South China Sea

Another potential implication of the renewal of great power competition is a linkage that is sometimes made between the Arctic and the South China Sea relating to international law of the sea or the general issue of international cooperation and competition.123 One aspect of this linkage

***

Play the Game,” Modern Diplomacy, March 14, 2020; Matteo Giovannini, “China and Russia Strengthen Strategic Partnership Along ‘Polar Silk Road,’” China Daily, December 6, 2019; “Russia Reinforces its Arctic Policies (With China Alongside),” Over the Circle, April 19, 2019: Melody Schreiber, “US Has ‘Vital National Interests’ at Stake in Russia-China Relationship in the Arctic, Expert Says,” Arctic Today, April 2, 2019; Rebecca Pincus, China and Russia in the Arctic, Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on “An Emerging China-Russia Axis? Implications for the United States in an Era of Strategic Competition,” March 21, 2019; Liz Ruskin, “China, Russia Find Common Cause in Arctic,” Alaska Public Media, March 21, 2019; Olga Alexeeva and Frederic Lasserre, “An Analysis of Sino-Russian Cooperation in the Arctic in the BRI Era,” Advances in Polar Science, December 2018: 269-282; Marc Lanteigne, “Northern Crossroads, Sino-Russian Cooperation in the Arctic,” National Bureau of Asian Research, March 2018, 6 pp. Nicholas Groffman, “Why China-Russia Relations Are Warming Up in the Arctic,” South China Morning Post, February 17, 2018.

121 Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2020, Annual Report to Congress, generated August 21, 2020, released September 1, 2020, p. 133.

122 See, for example, Elizabeth Buchanan, “Russia and China in the Arctic: Assumptions and Realities,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, September 25, 2020; Maria Shagina and Benno Zogg, “Arctic Matters: Sino-Russian Dynamics,” Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich, September 2020, 4 pp.; Elizabeth Buchanan, “There Is No Arctic Axis, Russia and China’s Partnership in the North is Primarily Driven by Business, Not Politics,” Foreign Policy, July 21, 2020; Mariia Kobzeva, “A Framework for Sino-Russian Relations in the Arctic,” Arctic Institute, May 5, 2020; Ling Guo and Steven Lloyd Wilson, “China, Russia, and Arctic Geopolitics,” Diplomat, March 29, 2020; James Foggo III, “Russia, China Offer Challenges in the Arctic,” Defense One, July 10, 2019; Anita Parlow, “Does a Russia-China Alignment in the Arctic Have Staying Power?” Arctic Today, June 27, 2019; Marc Lanteigne, “Scenes from a Northern Crossroad: China and Russia in the Arctic,” Over the Circle, February 20, 2019; Marc Lanteigne, “No Borderline: A Norway-Russia Frontier Festival Connects with China,” Over the Circle, February 16, 2019; Atle Staalesen, “Beijing Finds a Chinatown on NoRway’s Arctic Coast,; The Asian Superpower Looks towards the Arctic and Finds a Home in This Year’s Barents Spektakel Winter Festival,” Barents Observer, February 12, 2019; Elizabeth Wishnick, “Russia and the Arctic in China’s Quest for Great-Power Status,” in Ashley J. Tellis, Alison Szalwinski, and Michael Wills, editors, Strategic Asia 2019, China’s Expanding Strategic Ambitions, National Bureau of Asian Research, Seattle and Washington, DC, pp. 64-75.

123 See, for example, Robinson Meyer, “The Next ‘South China Sea’ Is Covered in Ice,” Atlantic, May 15, 2019; Justin D. Nankivell, “The Role of History and Law in the South China Sea and Arctic Ocean,” Maritime Awareness Project, August 7, 2017; Sydney J. Freedberg, “Is The Arctic The next South China Sea? Not Likely,” Breaking Defense, August 4, 2017; Caroline Houck, “The Arctic Could Be the Next South China Sea, Says Coast guard Commandant,” Defense One, August 1, 2017; Daniel Thomassen, “Lessons from the Arctic for the South China Sea,” Center for International Maritime Security, April 4, 2017.

p. 37

relates to whether China’s degree of compliance with international law of the sea in the South China Sea has any implications for understanding potential Chinese behavior regarding its compliance with international law of the sea (and international law generally) in the Arctic. A second aspect of this linkage, mentioned earlier, is whether the United States should consider the option of moving to suspend China’s observer status on the Arctic Council as a punitive costimposing measure for unwanted Chinese actions in the South China Sea. A third aspect of this linkage concerns the question of whether the United States should become a party to UNCLOS: Discussions of that issue sometimes mention both the situation in the South China Sea124 and the extended continental shelf issue in the Arctic.125

***

124 For further discussion of this situation, see CRS Report R42784, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress.

125 See, for example, Ben Werner, “Zukunft: U.S. Presence in Arctic Won’t Stop Chinese, Russia Encroachment Without Law of the Sea Ratification,” USNI News, August 1, 2017.

SUMMARY

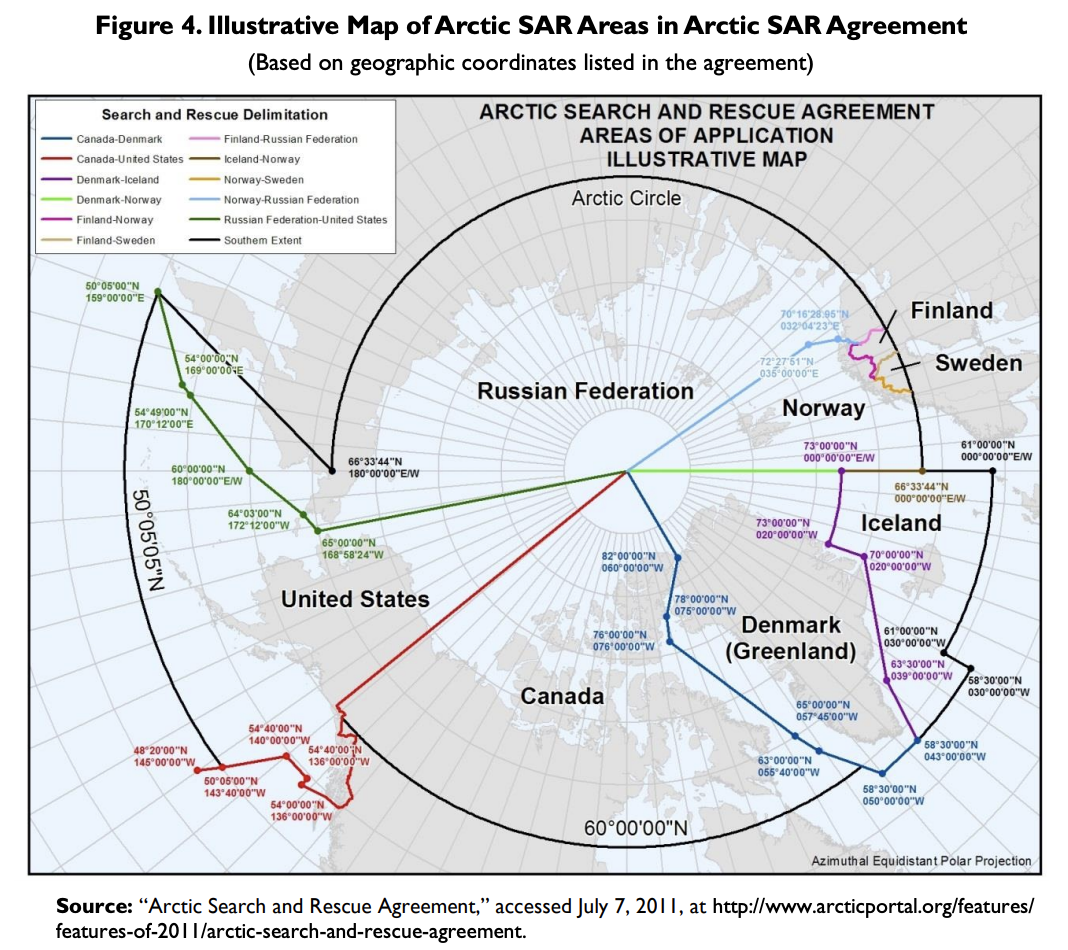

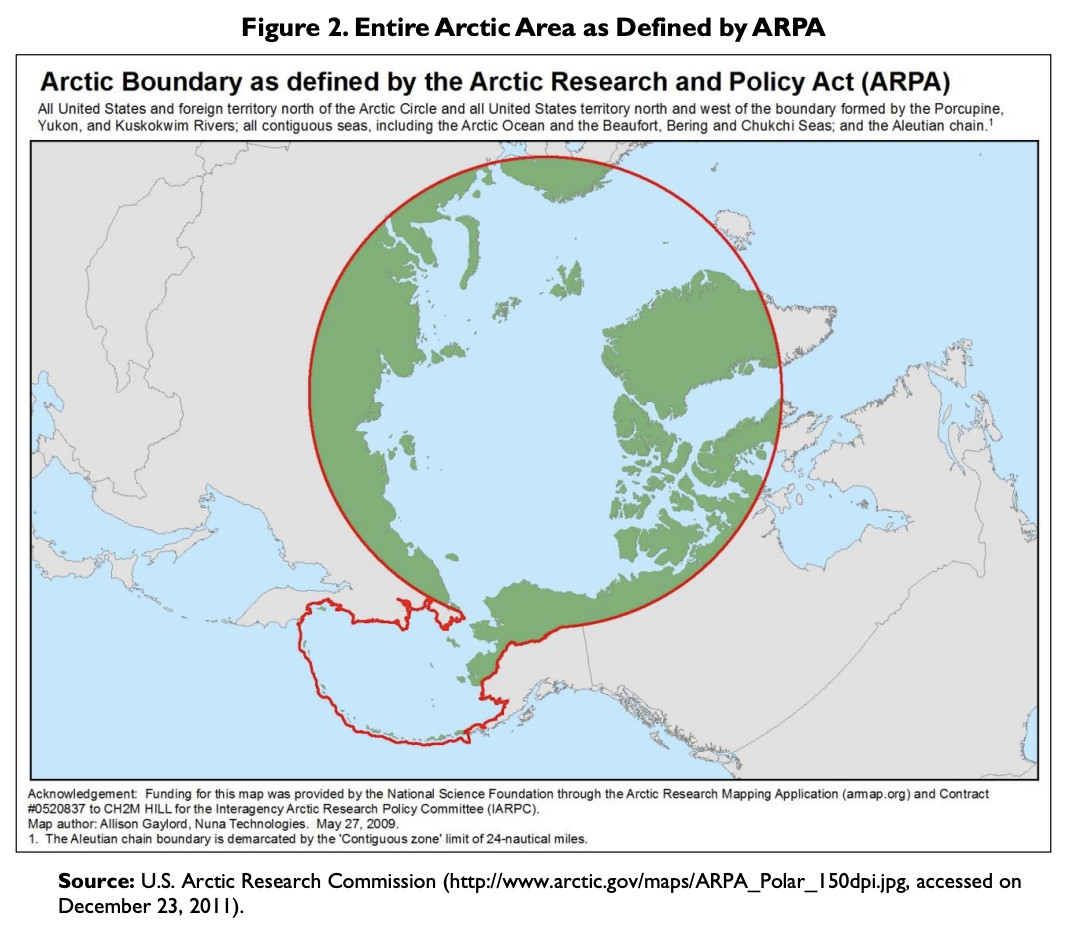

The diminishment of Arctic sea ice has led to increased human activities in the Arctic, and has heightened interest in, and concerns about, the region’s future. The United States, by virtue of Alaska, is an Arctic country and has substantial interests in the region. The seven other Arctic states are Canada, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark (by virtue of Greenland), and Russia.

The Arctic Research and Policy Act (ARPA) of 1984 (Title I of P.L. 98-373 of July 31, 1984) “provide[s] for a comprehensive national policy dealing with national research needs and objectives in the Arctic.” The National Science Foundation (NSF) is the lead federal agency for implementing Arctic research policy. Key U.S. policy documents relating to the Arctic include National Security Presidential Directive 66/Homeland Security Presidential Directive 25 (NSPD 66/HSPD 25) of January 9, 2009; the National Strategy for the Arctic Region of May 10, 2013; the January 30, 2014, implementation plan for the 2013 national strategy; and Executive Order 13689 of January 21, 2015, on enhancing coordination of national efforts in the Arctic. On July 29, 2020, the Trump Administration announced that career diplomat James (Jim) DeHart would be the U.S. coordinator for the Arctic region.

The Arctic Council, created in 1996, is the leading international forum for addressing issues relating to the Arctic. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) sets forth a comprehensive regime of law and order in the world’s oceans, including the Arctic Ocean. The United States is not a party to UNCLOS.

Record low extents of Arctic sea ice over the past decade have focused scientific and policy attention on links to global climate change and projected ice-free seasons in the Arctic within decades. These changes have potential consequences for weather in the United States, access to mineral and biological resources in the Arctic, the economies and cultures of peoples in the region, and national security.

The geopolitical environment for the Arctic has been substantially affected by the renewal of great power competition. Although there continues to be significant international cooperation on Arctic issues, the Arctic is increasingly viewed as an arena for geopolitical competition among the United States, Russia, and China. Russia in recent years has enhanced its military presence and operations in the Arctic, and the United States, Canada, and the Nordic countries have responded with their own increased presence and operations. China’s growing diplomatic, economic, and scientific activities in the Arctic have become a matter of increasing curiosity or concern among the Arctic states and other observers.

The Department of Defense (DOD) and the Coast Guard are devoting increased attention to the Arctic in their planning and operations. Whether DOD and the Coast Guard are devoting sufficient resources to the Arctic and taking sufficient actions for defending U.S. interests in the region has emerged as a topic of congressional oversight. The Coast Guard has two operational polar icebreakers and has received funding for the procurement of the first of at least three planned new polar icebreakers.

The diminishment of Arctic ice could lead in coming years to increased commercial shipping on two trans-Arctic sea routes—the Northern Sea Route close to Russia, and the Northwest Passage close to Alaska and through the Canadian archipelago—though the rate of increase in the use of these routes might not be as great as sometimes anticipated in press accounts. International guidelines for ships operating in Arctic waters have been recently updated.