The Oriana Skylar Mastro Bookshelf: Scholar-Servicemember Insights into Leading Chinese & Indo-Pacific Security Issues

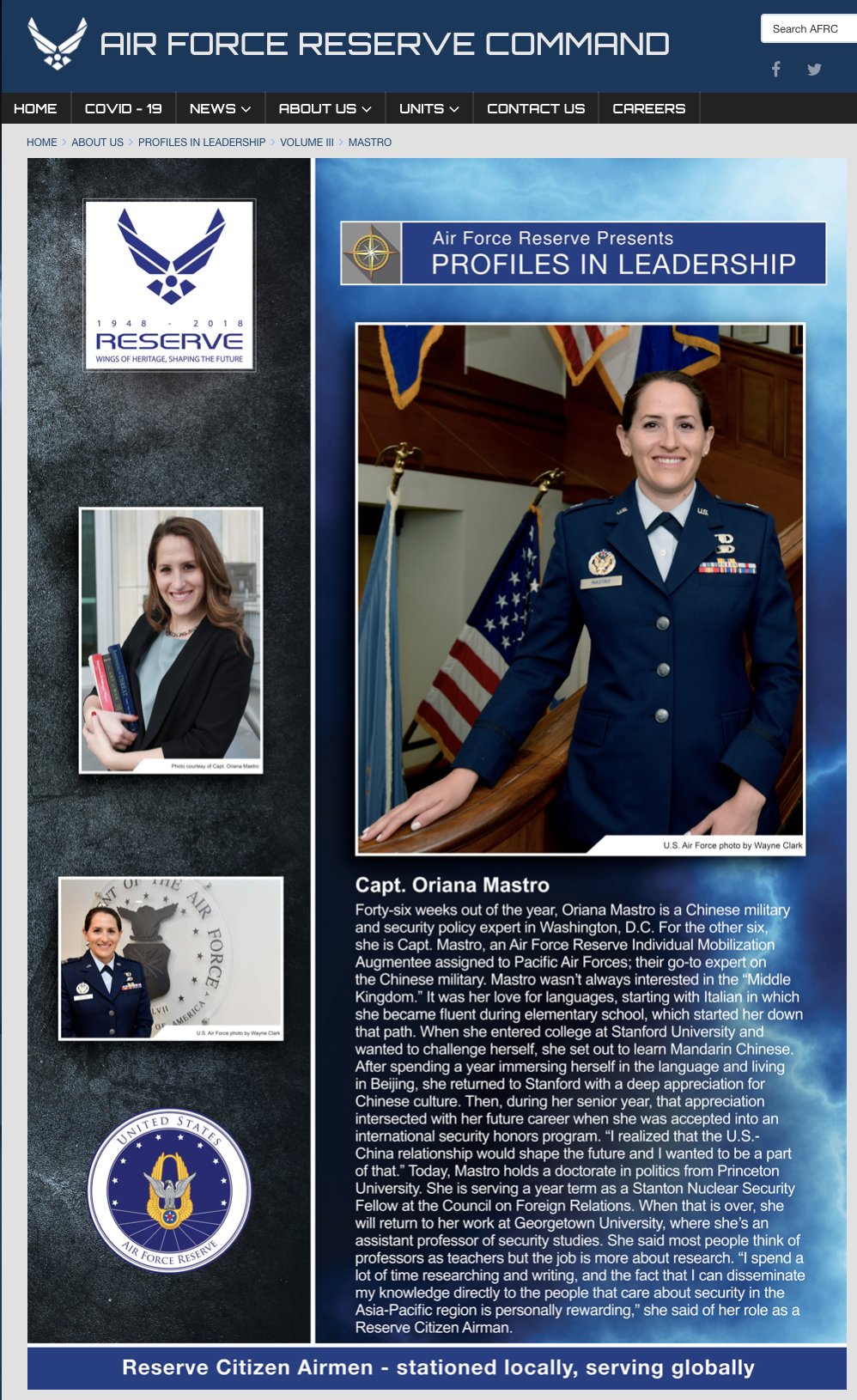

Dr. Oriana Skylar Mastro is a Center Fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI). Within FSI, she works primarily in the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center (APARC) and the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) as well. She is also a fellow in Foreign and Defense Policy Studies at the American Enterprise Institute and an inaugural Wilson Center China Fellow.

Mastro is an international security expert with a focus on Chinese military and security policy issues, Asia-Pacific security issues, war termination, and coercive diplomacy. Her research addresses critical questions at the intersection of interstate conflict, great power relations, and the challenge of rising powers. She leverages process tracing, qualitative historical analysis, and the case study method with the goal of conducting policy-relevant research. She has published widely, including in Foreign Affairs, International Security, International Studies Review, Journal of Strategic Studies, The Washington Quarterly, The National Interest, Survival, and Asian Security. She is also the author of The Costs of Conversation: Obstacles to Peace Talks in Wartime (Cornell University Press, 2019) which won the American Political Science Association International Security Section’s Best Book Award for pre-tenured faculty in 2020.

Mastro also continues to serve in the United States Air Force Reserve, for which she works as a Strategic Planner at INDOPACOM. She has received numerous awards for her military service and contributions to U.S. strategy in Asia, including the 2020 and 2018 Meritorious Service Medal, the 2017 Air Force recognition Ribbon, and the 2016 Individual Reservist of the Year Award. In 2017, the National Bureau of Asian Research awarded her the Ellis Joffe Prize for PLA Studies.

Prior to her appointment at Stanford in August 2020, Mastro was an assistant professor of security studies at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. She holds a B.A. in East Asian Studies from Stanford University and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Politics from Princeton University.

Follow her commentary on Twitter @osmastro and her website at orianaskylarmastro.com.

Research interests: Chinese military and security policy, Asia-Pacific security issues, war termination, coercive diplomacy, international security

梅慧琳博士是斯坦福大学弗里曼斯波利 (Freeman Spogli) 国际问题研究院的研究员,主要研究有关中国的军事与安全政策、亚太安全问题、战争终止和强制性外交等议题。梅博士也是美国企业公共政策研究所 (AEI) 的常驻学者并同时作为空军预备役在美国印太司令部 (INDOPACOM) 身兼战略规划员一职。鉴于她为美国亚洲战略所作出的贡献,梅博士于2016年获得预备役杰出个人奖之殊荣。梅博士常在《外交事务 (Foreign Affairs)》、《国际安全 (International Security)》、《国际研究评论 (International Studies Review)》、《战略学学刊 (Journal of Strategic Studies)》、《华盛顿季刊 (The Washington Quarterly)》、《国家利益 (The National Interest)》、《存续 (Survival)》和《亚洲安全 (Asian Security)》等期刊广泛发表评论,并著有《对话的代价: 战时和平谈判之障碍》(康奈尔大学出版社, 2019) 一书。梅博士在斯坦佛大学获得东亚研究学士学位,并在普利斯顿大学获得政治学硕士和博士学位。需要了解梅博士著作和评论以及近况的可访问她的推特 (@osmastro) 和个人网站 (orianaskylarmastro.com)。

PUBLICATIONS & PRESENTATIONS

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “The United States Must Avoid a Nuclear Arms Race with China,” CATO Unbound: A Journal of Debate, 21 September 2020.

In his lead essay, Eric Gomez cites profound technological changes as the main reason why the United States should rethink its nuclear policy. However, there is one drastic change he does not adequately take into account: the rise of China. This response essay, therefore, focuses on the China factor in U.S. nuclear policy.

Chinese Nuclear Modernization

Since the turn of the century, China has been modernizing its nuclear forces in earnest. Currently, Beijing’s nuclear arsenal is estimated to number in the 200s. From 2017 to 2018, warheads increased by ten, and the Pentagon anticipates that the stockpile will double over the next ten years. These modernization efforts, such as moving from silo-based liquid-fueled ICBMs to mobile solid-fueled delivery vehicles, have focused mainly on improving force survivability. China also added a sea leg to its nuclear deterrent in 2016 with the introduction of submarine-launched ballistic missiles (JL-2) on its Jin-class ballistic missile submarine.

Additionally, China is producing ballistic missile systems with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) and maneuverable reentry vehicle (MaRV) technologies that enhance missiles’ effectiveness. To this end, China has launched more ballistic missiles for testing and training in 2019 than the rest of the world combined. Meanwhile, the PLA’s new hypersonic cruise missiles supposedly are capable of piercing existing missile defense systems. Furthermore, structural reforms in China’s military reveal the critical role nuclear weapons play in Chinese strategy. In 2016, the branch in charge of China’s nuclear deterrent, the Second Artillery, was upgraded to a service, the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force. Its commander was added to China’s highest military body, the Central Military Commission.

China’s drive to modernize, diversify, and expand its nuclear forces may cause some to argue with Gomez’s essential premise that new thinking is needed. This week, U.S. Strategic Commander Adm. Charles Richard remarked that China’s nuclear weapons buildup is “inconsistent” with their long-held no-first-use policy, emphasizing the need for the United States to pursue nuclear modernization. Indeed, there has been a resurgence in Cold War thinking about nuclear deterrence. For example, Former Senator Jon Kyl and Michael Morell argued for more low-yield nuclear warheads as part of an “escalate to deescalate” strategy. Similarly, Bret Stephens raised concerns that the U.S. arsenal is insufficient to prevent Chinese aggression.

However, I agree with Gomez that we need to rethink U.S. nuclear policy to ensure it can better meet contemporary challenges. Specifically, I argue that to best suit U.S. foreign policy interests, U.S. nuclear policy needs to minimize the role of nuclear weapons in U.S.-China great power competition and pave the way for arms control. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “China-India: Talk is Cheap, But Never Free,” Lowy Interpreter, 29 September 2020.

Temper the negotiation hopes. States often worry a willingness to talk will communicate weakness to an adversary.

There is no end in sight for the ongoing China-India border crisis. In June, China and India’s border dispute along the LAC (Line of Actual Control) resumed after a decades-long halt to the fighting, with the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers and an unspecified number of casualties on the Chinese side. After a few months of relative calm, tensions erupted in late August with “provocative military movements” near Pangong Tso Lake and a Tibetan soldier’s death in India’s Special Frontier Forces. Only a few weeks ago, both sides accused each other of firing warning shots, the first use of live fire in 45 years.

Although China and India’s foreign ministers recently agreed to disengage at talks in Moscow during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation meeting, troops remain massed at the border. China is reportedly building military infrastructure. Many worry that increased tensions could lead to war, especially given India’s limited options.

As the second- and fourth-largest militaries in the world – and two nuclear powers at that – soon enter the fifth month of a standoff, the world has been relatively silent. All countries, especially the United States, should help China and India avoid an armed confrontation. Wars happen, especially over territory. And it wouldn’t be the first time the two countries have fought over this issue. Fifty-eight years ago, the two countries found themselves at war when massed Chinese artillery opened fire on a weak Indian garrison in Namka Chu Valley, in an eastern area China considers Southern Tibet and India calls Arunachal Pradesh. China launched a simultaneous assault against the western sector, clearing Indian posts north of Ladakh. After 30 days of sporadic fighting, the war came to an end with a unilateral Chinese withdrawal from much of the territory it had seized.

But such a unilateral ceasefire is extremely rare. Most contemporary conflicts end through a negotiated settlement. This means getting the two countries to talk to each other face-to-face during a war can be necessary for war termination. But my research shows this does not come easily – states are often concerned that a willingness to talk will communicate weakness to their adversary, who, in turn, will be encouraged to continue the fighting. Only when states are confident their diplomatic moves will not convey weakness, and their adversary does not have the will or capabilities to escalate is a belligerent willing to come to the negotiating table.

What does this all mean for the prospects of peace in a China-India border conflict? The short answer is it depends on how the war goes for both sides and whether outside countries are involved. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “China’s Maritime Ambitions: Implications for U.S. Regional Interests,” testimony at hearing on “China’s Maritime Ambitions,” U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific, and Nonproliferation, via WebEx to Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC, 30 June 2020.

Chairman Bera, Ranking Member Yoho, members of the subcommittee: thank you for the opportunity to share my views on China’s maritime ambitions.

China wants to become a ‘maritime great power,’ a term Chinese President Xi Jinping uses as part of his national revitalization rhetoric.1 To this end, China is building a blue-water navy that can control its near seas, fight and win regional wars, and protect its vital sea lanes and its many political and economic interests beyond East Asia. But whether in the near or far seas, China’s ambitions engage U.S. interests.

Therefore, in this testimony, I will focus on China’s approach to the near seas—the South China Sea (SCS) and the East China Sea (ECS) —and touch upon its intentions in the Indian Ocean. But first, I would like to lay out a few thoughts about how to conceptualize ambition more generally. This may seem academic, but I believe a rigorous framework is crucial for understanding the nuances of China’s ambitions and devising effective U.S. strategic responses.

Using this framework, I come to two main conclusions: 1) China’s ambitions are different in the SCS and ECS than in the Indian Ocean and beyond. For the near seas, China is concerned with sovereignty and regional hegemony; for the far seas, it is concerned with protecting the sources of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) domestic legitimacy such as economic growth, guarding against external political pressure, and protection Chinese nationals. But all of its ambitions are about competition with the United States. 2) China’s objectives in the SCS and ECS are detrimental to U.S. interests, but its methods are problematic mainly because they are effective and difficult to counter. In contrast, in the Indian Ocean and beyond, there are aspects of China’s current objectives that are legitimate and do not necessarily threaten U.S. interests. But its methods are undermining democratic principles and sustainable growth. Moreover, there is the risk that China could change its strategy to disrupt freedom of navigation as its capabilities evolve. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Has COVID-19 Changed How China’s Leaders Approach National Security?” ChinaFile, 3 June 2020.

he Chinese leadership’s preference for a benign external security environment during the country’s rise has not changed, but views about how to achieve this end state may be evolving. For most of the post-reform era, China’s leaders have attempted to ensure global conditions conducive to their interests by reassuring other countries that China’s rise would be peaceful. Even as China has become even more assertive in its maritime claims, vis-à-vis Taiwan, and most recently along the line of actual control (LAC) with India, rhetoric from Beijing has tended to emphasize China’s inherently peaceful nature. As recently as the spring of 2019, at the 18th Shangri-La Dialogue, China’s defense minister, General Wei Fenghe, contended that China has “never provoked a war or conflict, nor has it ever invaded another country or taken an inch of land from others,” and assured that it never will. In short, the strategic focus has largely been on reassurance.

But there is another parallel thread within Chinese historical and contemporary behavior: a deep fear that foreign powers will exploit times of internal difficulty to their benefit, and China’s detriment. This interpretation of history, which admittedly is highlighted and propagated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for its own ends, can cause the CCP to deviate from assurance to focus on deterrence as a means to create a benign security environment. The recent spike in Chinese military and paramilitary activities in the South and East China Sea and exercises around and incursions along the LAC with India may be designed to warn those actors that COVID-19 has not made China soft.

In this vein, China often sees its assertiveness as a response to a transgression by the other side, a tendency Andrew Scobell of RAND calls its “cult of defense.” Chinese media has accused Vietnam of making trouble in the South China Sea during the pandemic and Taiwan of taking advantage of COVID to expand its international space with its “mask diplomacy.” In short, the CCP may believe its aggressive actions will ensure a benign external environment during the uncertainty of COVID by deterring other actors from taking actions detrimental to Beijing.

Lastly, there has always been an opportunistic strain in the behavior of the CCP’s leadership, especially under Xi Jinping. As its relative power gap grows, China may be more confident in pushing its agenda. According to this logic, Beijing may still care about the security environment and yet doubt other countries can do much to undermine its rise.

So, which is it? I would be surprised if the Chinese leadership were so confident at this level of its power, especially given the U.S. focus on strategic competition and America’s military might. I think an emphasis on deterrence to ensure a benign security environment is the more likely explanation for recent Chinese assertiveness. But if China comes out on top post-COVID, motivations for its aggression may shift to opportunism. Regardless, it seems that provocative and aggressive behavior, especially against its neighbors, is here to stay.

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Rising Tensions in the South China Sea,” Council on Foreign Relations, 20 May 2020.

The risk of a military confrontation between the United States and China in the South China Sea is growing. In a new Center for Preventive Action report, Oriana Skylar Mastro details how the United States could prevent a clash, or take steps to de-escalate if one should occur.

Tensions between the United States and China have been rising in the South China Sea over the past two months as both countries increase their military operations in the contested waters. These tensions have been further exacerbated by recriminations over the ongoing trade war and the spread of the novel coronavirus. In a recent report, “Military Confrontation in the South China Sea,” I argue that these dynamics point to a worrying trend: the risk of a military clash in the South China Sea involving the United States and China could rise significantly in the next eighteen months.

The two countries have serious conflicting interests that could spark crisis and conflict. Beijing considers the majority of the South China Sea to be an inalienable part of its territory and exercising full sovereignty over this area is a core component of President Xi Jinping’s “China Dream.” For its part, the United States needs these waterways to stay free and open if it is to deter Chinese aggression, live up to its alliance commitments, and prevent Beijing from displacing the United States in the Indo-Pacific.

To date, conflict has largely been avoided because China has used primarily economic and diplomatic coercive measures to expand and consolidate its control over the South China Sea. In recent months, however, China has begun to rely more heavily on military means to aggressively assert China’s claims. In February, there was a report from the Philippines that a Chinese Navy ship pointed its “fire control radar” at a Philippine Navy ship off Commodore Reef in the Spratly Islands, though China denies the claim. In March, China opened two new research stations on Fiery Cross Reef and Subi Reef in the Spratly Islands; these facilities are also equipped with defense silos and military-grade runways. In April, Beijing attempted to strengthen its maritime claims in the South China Sea through the creation of two new municipal districts. Overall, the Chinese military is stepping up its activities—including its patrols—in these waters. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Military Confrontation in the South China Sea,” Contingency Planning Memorandum No. 36, Council on Foreign Relations, 21 May 2020.

The trade war, fallout from COVID-19, and increased military activity raise the risk of conflict between the United States and China in the South China Sea. Oriana Skylar Mastro offers nine recommendations for ways the United States can prevent or mitigate a military clash.

Introduction

The risk of a military confrontation in the South China Sea involving the United States and China could rise significantly in the next eighteen months, particularly if their relationship continues to deteriorate as a result of ongoing trade frictions and recriminations over the novel coronavirus pandemic. Since 2009, China has advanced its territorial claims in this region through a variety of tactics—such as reclaiming land, militarizing islands it controls, and using legal arguments and diplomatic influence—without triggering a serious confrontation with the United States or causing a regional backlash. Most recently, China announced the creation of two new municipal districts that govern the Paracel and Spratly Islands, an attempt to strengthen its claims in the South China Sea by projecting an image of administrative control. It would be wrong to assume that China is satisfied with the gains it has made or that it would refrain from using more aggressive tactics in the future. Plausible changes to China’s domestic situation or to the international environment could create incentives for China’s leadership to adopt a more provocative strategy in the South China Sea that would increase the risk of a military confrontation. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Instability looms in North Korea,” The Survival Editors’ Blog, 4 May 2020.

What will happen to North Korea if Kim Jong-un’s regime collapses? Although the North Korean leader has reappeared in public, Oriana Skylar Mastro warns that we should start preparing for the sudden collapse of his regime.

North Korean state media published on Friday 1 May reports of Kim Jong-un’s presence at the opening ceremony of a fertilizer factory in Sunchon, the North Korean dictator’s first public appearance since 11 April. South Korean officials claim that Kim did not undergo surgery or any other medical procedure during his public absence. But no one has offered any explanations for his disappearance, including why he missed the 15 April holiday to celebrate the birthday of his late grandfather and founder of North Korea, Kim Il-sung. This incident has also raised concerns about what the end of the Kim regime could mean for the country and how unprepared the world currently is, should something unexpected happen to Kim.

Even though Kim is still apparently alive, that does not mean North Korea is inured to instability. My historical analysis of 31 autocratic hereditary regimes since the Second World War tells us that if Kim were in any way incapacitated it would likely mean the end of the regime. Admittedly, North Korea has been a historical exception − the only clean case of a ruling family retaining true power into the third generation. But many of the reasons Kim Jong-un was able to successfully consolidate power after the death of his father, Kim Jong-il, do not currently apply. Kim Jong-il selected Kim Jong-un as his successor perhaps as early as 1992 (the elder Kim died in 2011) and helped build his legitimacy by travelling around the country with him. After Kim Jong-un was named the official successor, he also became the head of the military and intelligence apparatus, which helped him consolidate his own power within the regime. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “5 Things to Know If Kim Jong Un Dies,” 27 April 2020.

Hereditary dictatorships rarely last past three generations, and collapse may be in the cards for North Korea.

North Korea’s dictator, Kim Jong Un, was reported to have had a cardiovascular procedure on April 12, treating a health condition allegedly stemming from “excessive smoking, obesity, and overwork,” according to one South Korean publication. Since then, Kim has not made any public appearances; he was absent from April 15 celebrations of North Korea’s most important holiday, the birthday of his grandfather and founder of the regime, Kim Il Sung. On Saturday, April 25, he even missed the annual parade celebrating the founding of the armed forces. Panic has reportedly broken out in North Korea’s capital of Pyongyang, where residents are buying up necessities in preparation for the worst.

As a result, there is much speculation that the North Korean leader is gravely ill. U.S. officials and the intelligence community have received reports about Kim’s troubled health, but, given the closed nature of North Korea, it is impossible to accurately assess the severity of Kim’s condition.

If Kim dies, or is even incapacitated, it poses a serious threat to the regime. The hereditary nature of North Korea’s government means that internal stability is heavily reliant on the smooth succession to a new leader—which likely means one of Kim’s family members. But, as I found in my recent study of all hereditary autocracies since World War II, passing power is particularly difficult in family dictatorships, where the ability to find an individual who is both competent and enjoys elites’ support is relatively low, due to the small pool of candidates. As in medieval monarchies, succession crises become the norm, and obscure figures or new dynasties rise as a result: Since World War II, no family dictatorship has ever managed to pass power for a third time.

The situation is dire in North Korea, where there is no clear successor to Kim. Instability in North Korea would have immediate and long-term implications for the region and U.S.-China competition. Here are five things you need to know as speculation about Kim’s health continues. … … …

***

Oriana Mastro and Arzan and Tarapore, “Asymmetric But Uneven: The China-India Conventional Military Balance,” in Kanti Bajpai, Selina Ho, and Manjari Chatterjee Miller, eds., Routledge Handbook of China-India Relations (London: Routledge, 2020), 235–47.

What are the key trends in the conventional military balance between China and India? This chapter addresses how each country’s military forces are postured to deter and, if necessary, fight the other. It examines each side’s military priorities, programs of military modernization to date, the local military balance on their land border and in the Indian Ocean, and the implications of these factors for the outcome of potential crises and conflicts.

The Routledge Handbook of China–India Relations provides a much-needed understanding of the important and complex relationship between India and China. Reflecting the consequential and multifaceted nature of the bilateral relationship, it brings together thirty-five original contributions by a wide range of experts in the field. The chapters show that China–India relations are more far-reaching and complicated than ever and marked by both conflict and cooperation. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “All in the Family: North Korea and the Fate of Hereditary Autocratic Regimes,” Survival 62.2 (March 2020), 103–24.

Even though the Kim regime has been an exception, the pattern of rapid, unexpected regime collapse among hereditary autocracies indicates a need for policymakers to be prepared.

What is the weakest link in a hereditary autocracy, what are the patterns of collapse and what typically happens after the end of such a regime? This article identifies four patterns concerning the collapse of such regimes. These findings are relevant to policy makers that hope to evaluate the stability of the North Korean regime and plan adequately for its aftermath. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, The Cost of Conversation: Obstacles to Peace Talks in Wartime (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019).

After a war breaks out, what factors influence the warring parties’ decisions about whether to talk to their enemy, and when may their position on wartime diplomacy change? How do we get from only fighting to also talking?

In The Costs of Conversation, Oriana Skylar Mastro argues that states are primarily concerned with the strategic costs of conversation, and these costs need to be low before combatants are willing to engage in direct talks with their enemy. Specifically, Mastro writes, leaders look to two factors when determining the probable strategic costs of demonstrating a willingness to talk: the likelihood the enemy will interpret openness to diplomacy as a sign of weakness, and how the enemy may change its strategy in response to such an interpretation. Only if a state thinks it has demonstrated adequate strength and resiliency to avoid the inference of weakness, and believes that its enemy has limited capacity to escalate or intensify the war, will it be open to talking with the enemy.

Through four primary case studies—North Vietnamese diplomatic decisions during the Vietnam War, those of China in the Korean War and Sino-Indian War, and Indian diplomatic decision making in the latter conflict—The Costs of Conversation demonstrates that the costly conversations thesis best explains the timing and nature of countries’ approach to wartime talks, and therefore when peace talks begin. As a result, Mastro’s findings have significant theoretical and practical implications for war duration and termination, as well as for military strategy, diplomacy, and mediation. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Diminishing Returns in U.S.-China Security Cooperation,” The U.S. and China in Asia: Mitigating Tensions and Enhancing Cooperation (Washington, DC: John Hopkins SAIS Pacific Community Initiative, October 2019), 32–42.

Introduction

U.S.-China relations have entered a period best characterized as an era of increased tension with aspects of strategic competition. Despite what President Trump has called the “great chemistry” between him and President Xi, the two countries are escalating disagreements over issues such as trade, the North Korean nuclear and missile programs, and the South China Sea.1

The United States trade deficit with China rose to a record $419 billion in 2018, with the United States importing only a third of what China was exporting. To protect American manufacturing and to stop “unfair transfers of American technology and intellectual property to China,” Trump imposed three rounds of tariffs on Chinese products in 2018, the most recent in September on over $250 billion worth of goods. Moreover, the U.S. is specifically targeting high-tech Chinese goods to put pressure on Beijing’s Made in China 2025 plan, and China is deliberately targeting U.S. agricultural products such as soybeans.

On North Korean security issues, China consistently condemns Kim Jong-un’s nuclear ambitions and supports the UN Security Council’s sanctions on North Korea. Despite its promises, however, China slowly relaxed its sanctions over the summer of 2018, conducting illicit ship-to-ship transfers of oil and allowing North Korean workers to return to jobs inside China. This softened stance has made it extremely difficult for the Trump administration to keep up its economic pressure on North Korea to stop building nuclear weapons.

Finally, in the East and South China Seas, unsafe air encounters and U.S. freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) are points of serious contention between the two countries. China’s maneuvers in these waters have grown increasingly aggressive. In October, an unidentified Chinese destroyer came within 45 feet of the USS Decatur as it was conducting a routine freedom of navigation operation, in what is described as an “unsafe and unprofessional maneuver.”2 … … …

***

Bonnie S. Glaser and Oriana Skylar Mastro, “How an Alliance System Withers: Washington Is Sleeping Through the Japanese-Korean Dispute. China Isn’t,” Foreign Affairs, 9 September 2019.

For more than half a century, U.S. power in Asia has rested on the alliance system that Washington built in the years after World War II. Now, a dispute between Japan and South Korea—the two most important pillars of that system—threatens to undo decades of progress.

But instead of seeking to actively mediate between its allies, Washington has largely watched from the sidelines—leaving the field to China, which has moved quickly to benefit from U.S. inaction. At a trilateral summit with the Japanese and South Korean foreign ministers in late August, for instance, China encouraged the two sides to at least put aside their differences long enough to make progress on a trilateral trade deal. This should give Washington pause. If, in the years ahead, the U.S. alliance system collapses, it is moments like this that will mark the beginning of the end: moments when Beijing, long intent on breaking U.S. alliances in Asia, proved more capable of managing and reinforcing regional order than a distracted United States.

The latest round of friction between South Korea and Japan began in the halls of South Korea’s supreme court. In the fall of 2018, the court ordered three Japanese companies to compensate South Koreans who claimed that they had been used as forced laborers in World War II. Tokyo, however, maintains that any claims to reparations for wartime abuses were settled by the $800 million in economic aid and loans it paid Seoul under a 1965 treaty. In March 2019, South Korean shop owners organized a nationwide boycott of Japanese goods. In response, the Japanese government restricted exports of three important chemicals used in the South Korean semiconductor industry, which accounts for a quarter of South Korea’s total exports. Japan also removed South Korea from its white list of preferred trading partners. Seoul responded in kind and went a step further, pulling out of a new intelligence-sharing agreement that had taken years to negotiate.

Chinese policymakers have recognized the rift between Seoul and Tokyo as a godsend. Fractures between two crucial U.S. allies make it harder for Washington to form a united front in peacetime or in a potential crisis. Such disunity also benefits China when it comes to dealing with North Korea, the nuclear-armed pariah state on its border. Here, Beijing favors sanctions relief, diplomatic engagement, and various economic inducements. So, too, does the current government of South Korea, but its space for engagement has been restricted by Washington and Tokyo, who prefer a more hawkish approach. Now, with the tripartite partnership under stress, China could try to make common cause with South Korea, disrupting Washington’s and Tokyo’s efforts to pursue hard-line policies. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “China’s Military Modernization Program: Trends and Implications,” Testimony before “U.S.-China Relations in 2019: A Year in Review,” hearing, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 4 September 2019.

Chinese Military Activities and Progress in the People’s Liberation Army’s Modernization in 2019

China’s military modernization program has continued apace, with defense spending growing for the 24th consecutive year, making China the second-largest defense spender after the United States.1 China spent an estimated $175.4 billion on defense in 2019, with funds going to personnel, training, and procurement.2 The increase in resources and effort has resulted in more frequent, sophisticated, and multifaceted People’s Liberation Army (PLA) presence and activities in the region and beyond. China’s main line of effort remains centered on East Asia, and its concerns are over the East China Sea, the South China Sea, and Taiwan. Below I capture the major developments in China’s regional activities with a focus on the South China Sea and China’s military presence beyond East Asia, as well as address recent developments in the Sino-Russian relationship and the publication of the 2019 Chinese Defense White Paper. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Pyongyang Is Playing Washington Against Beijing,” Foreign Policy, 5 August 2019.

China is finding it harder and harder to steer its troublesome ally.

On July 31, North Korea conducted its second missile test in a week, launching two short-range ballistic missiles from near the port of Wonsan. North Korean media reported that the tests were a “solemn warning” to South Korea about its planned military exercise with the United States in August and its purchase of U.S. fighter jets.

That won’t have pleased Beijing, which has long been frustrated by the provocations of both its only formal ally and the United States. Although China’s response was muted, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs asking all parties concerned to make positive efforts to promote denuclearization, Beijing has been pushing for both the United States and North Korea to, in its words, “cherish the hard-won momentum of dialogue and deescalation.” Unsurprisingly, China has criticized sporadic unilateral, aggressive U.S. behavior, attempting to push President Donald Trump toward a reassurance strategy of reducing sanctions and military presence. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, testimony before the hearing on “A New Approach for An Era of U.S.-China Competition,” Senate Foreign Relations Committee, 13 March 2019.

Chairman Risch, Ranking Member Menendez, and distinguished members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to discuss some of the ways China is challenging US primacy in the region and in the international system more broadly. Before I begin describing the tactics China has been employing to accumulate power and influence, at times at the United States’ expense, I want to be upfront about the strategic framework that colors my thinking.

First, I do not believe China is inherently a threat to the United States. But China has defined its interests and goals in such a way that they conflict with those of the United States. Specifically, China believes that dominance of the Indo-Pacific is central to its security and interests, meaning that Beijing cannot feel secure with the US forward presence in the region. And the United States cannot protect its own interests and national security without the ability to operate there. Thus, we have a serious conflict of interest.

Second, China prefers to use political and economic tools to achieve its security goals, but as its military becomes more proficient, it will not shy away from using this tool as well if the issue at hand is important and the other tools do not suffice. In other words, I believe Chinese leaders are being truthful when they say they would prefer to achieve China’s goals peacefully. But this just means that they hope the United States and others will fully accommodate their position without a fight.

Lastly, I believe China’s territorial aims are limited. It wants control over the South China Sea, the East China Sea and Taiwan, and nothing more. Thus, if the United States conceded to China the sphere of influence of Northeast, Southeast, Central, and South Asia, our points of contention would be greatly lessened. However, I also believe these demands are too much and that the US cannot concede to them without seriously jeopardizing its own security and that of its allies and partners in the region. In other words, it is easy to avoid conflict if you give the other side everything it wants. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “The Stealth Superpower: How China Hid Its Global Ambitions,” Foreign Affairs (January/February 2019).

Although China does not want to usurp the United States’ position as the leader of a global order, its actual aim is nearly as consequential. In the Indo-Pacific region, China wants complete dominance; it wants to force the United States out and become the region’s unchallenged political, economic, and military hegemon. And globally, even though it is happy to leave the United States in the driver’s seat, it wants to be powerful enough to counter Washington when needed.

“China will not, repeat, not repeat the old practice of a strong country seeking hegemony,” Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, said last September. It was a message that Chinese officials have been pushing ever since their country’s spectacular rise began. For decades, they have been at pains to downplay China’s power and reassure other countries—especially the United States—of its benign intentions. Jiang Zemin, China’s leader in the 1990s, called for mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality, and cooperation in the country’s foreign relations. Under Hu Jintao, who took the reins of power in 2002, “peaceful development” became the phrase of the moment. The current president, Xi Jinping, insisted in September 2017 that China “lacks the gene” that drives great powers to seek hegemony.

It is easy to dismiss such protestations as simple deceit. In fact, however, Chinese leaders are telling the truth: Beijing truly does not want to replace Washington at the top of the international system. China has no interest in establishing a web of global alliances, sustaining a far-flung global military presence, sending troops thousands of miles from its borders, leading international institutions that would constrain its own behavior, or spreading its system of government abroad.

But to focus on this reluctance, and the reassuring Chinese statements reflecting it, is a mistake. Although China does not want to usurp the United States’ position as the leader of a global order, its actual aim is nearly as consequential. In the Indo-Pacific region, China wants complete dominance; it wants to force the United States out and become the region’s unchallenged political, economic, and military hegemon. And globally, even though it is happy to leave the United States in the driver’s seat, it wants to be powerful enough to counter Washington when needed. As one Chinese official put it to me, “Being a great power means you get to do what you want, and no one can say anything about it.” In other words, China is trying to displace, rather than replace, the United States. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “In the Shadow of the Thucydides Trap: International Relations Theory and the Prospects for Peace in U.S.-China Relations,” Journal of Chinese Political Science 24 (2019): 25–45.

Abstract

Rising powers and the consequent shifts in the balance of power have long been identified as critical challenges to the international order. What is the likelihood that China and the United States will fall into the Thucydides Trap, meaning that the two countries will fight a major war during a potential power transition? This article creates a framework of seven variables, derived from dominant international relations theories and Graham Allison’s “twelve clues for peace,” that predict the likelihood of major conflict between a rising and an established power: degree of economic interdependence, degree of institutional constraints, domestic political system, nature of relevant alliances, nature of nuclear weapons programs, the sustainability of the rising power’s growth, and its level of dissatisfaction. It then evaluates the values of these variables in the context of the U.S.-China relationship to determine whether pessimism about the prospects of peace is warranted. This analysis leads to more mixed conclusions about the prospects of peace than liberal international relations theory and Allison’s twelve clues would suggest. This research further operationalizes power transition theory and has practical implications for U.S. policy toward China.

Keywords: U.S.-China relations, Thucydides trap, Power transition theory, Interstate war , Nuclear deterrence, Economic liberalism, International institutions

Introduction

Rising powers and the consequent shifts in the balance of power have long been identified as critical challenges to the international order. Unsurprisingly, power transition theory—the idea that as the power disparity between an incumbent great power and a rising power decreases, the likelihood of major war increases—has led to an outpouring of research that evaluates why major war occurs and whether it can be avoided [1]. Most recently, Graham Allison has argued that China and the United States are more likely than not to fight a war, given the historical record: 12 out of the 16 times a rising power has accumulated enough power to challenge the hegemon, the result was major war [2]. He characterizes this dynamic, in which the paranoia of the great power and the hubris of the rising power cause armed conflict, as the “Thucydides Trap.”

Will the United States and China go to war as the power gap between them decreases? What are the most likely pathways to conflict? The current IR approach to U.S.-China relations fails to adequately answer these questions for three reasons. First, it does not thoroughly evaluate the empirical record in the case of the United States and China. For example, Graham Allison derives from the four historical cases in which war was avoided twelve “clues for peace,” including variables such as institutionalization of the international system, nature of alliances, cultural similarity, economic interdependence, and nuclear dynamics. But Allison does not operationalize these variables by clearly outlining the values they can take and the ways those values correspond to the likelihood of war. This omission leaves open the question of whether these variables take on the values that correspond to a lower likelihood of war in the case of U.S.-China relations.1 And though many scholars and commentators have criticized Allison’s analysis as excessively pessimistic, few have focused their critiques on the degree to which these ‘clues for peace’ are applicable in the U.S.-China case.2

Second, the scholarship that does evaluate the empirical record with respect to U.S.-China relations tends to focus on only one variable at a time, failing to provide a comprehensive picture of all the mitigating and exacerbating factors. For example, there is literature on where alliance dynamics are stabilizing or destabilizing3; how nuclear weapons may dampen or increase tendencies to escalate to war; [10, 11] how economic relationships may motivate war, prevent it, or be irrelevant4; and the degree to which international institutions shape and constrain Chinese power [15, 16]. Few studies, however, weigh multiple factors and assess how they may work together to affect the likelihood of conflict.

Third, the work that has attempted to provide a comprehensive analysis of the factors impacting conflict is outdated, as the values of the variables in question have changed drastically over the past ten to twenty years [17–22]. In the 1990s, China was just beginning to join international institutions—in 2000, China participated in 52 international organizations, compared with 75 today [23, 24]. In 1999, China voted for the first time in favor of a nonconsensual peacekeeping operation; now, it is the largest contributor of peacekeeping troops among the permanent members of the UN Security Council and the third largest overall donor to the UN [25, 26]. During the same period, China’s economy grew from $4.8 trillion in purchasing power parity to $23.16 trillion, a nearly five-fold increase. Lastly, its military modernization had only just begun in the 1990s. In 1996, China spent only 1% of its GDP on its military [27]. Although the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had approximately four times as many personnel as the U.S. Army, China lagged severely behind in tanks, armored infantry fighting vehicles, and armored personnel carriers.5 The vast majority of vessels and aircraft in the PLA Navy (PLAN) and PLA Air Force (PLAAF) were outdated. For example, most submarines and fighter aircraft were based on 1950s Soviet designs.6 Between then and 2015, official military spending increased by 620%, enabling China to make great strides in modernizing its equipment and professionalizing its forces.7

In this article, I attempt to fill these gaps by doing three things. First, I create a comprehensive framework of the prospects for peace that synthesizes Allison’s twelve “clues” with the independent variables explored in dominant international relations theories about the causes of war and peace. The result is seven variables that are prevalent in scholars’ thinking on the likelihood of conflict between a rising and an incumbent great power. Then, I lay out these variables, explaining what values they can take and how these values correspond to the likelihood of war. Lastly, I evaluate the values of these variables in the context of the U.S.-China relationship to determine whether pessimism about the future prospects of peace is warranted.

Focusing on the applicability and predictions of the variables that purportedly dampen conflictive tendencies has both theoretical and practical implications. First, each of the twelve “clues” is related to a major debate within international relations theory. Determining whether these factors have the predicted impact in the case of a major power dyad, such as China and the United States, is critical to assessing their empirical validity. Second, while scholarship has evaluated some of these factors in the case of U.S.-China relations, the value of the relevant variables, such as the military balance of power, has changed considerably over the past ten years, and an updated analysis is needed. Third, evaluating multiple factors side-by-side allows for a more accurate picture of the sources of instability and some insight into the way conflict could break out. Lastly, understanding the salience and applicability of mitigating factors can help policy makers in both countries work effectively to reduce the likelihood of major war. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “It Takes Two to Tango: Autocratic Underbalancing, Regime Legitimacy and China’s Responses to India’s Rise,” Journal of Strategic Studies 42.1 (2019): 114–52.

ABSTRACT

What factors do autocracies evaluate when responding to perceived threats and why might they fail to balance appropriately? Do autocratic leaders choose greater exposure to an external threat if, by doing so, it preserves regime legitimacy?

I posit that autocratic leaders may choose greater exposure to an external threat if, by doing so, it preserves regime legitimacy. Specifically, the desire to promote a positive image to one’s domestic public creates incentives to publicly downplay a rival’s military progress, which then affects the state’s ability to mobilize resources to respond to the growing threat. I test this theory in the case of China’s response to India’s military rise. This research contributes to balancing theory and empirical work on East Asian security. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “The Theory and Practice of War Termination: Assessing Patterns in China’s Historical Behavior,” International Studies Review 20.4 (December 2018): 661–684.

How has China historically performed when it attempts to engage in conflict resolution? Are historical patterns of war termination behavior likely to manifest themselves in future conflicts, even with all the changes to China’s internal and external environments since its last war in 1979?

Abstract

What factors determine how China attempts to terminate armed conflict? This article derives from the war termination literature three factors that impact the ability of disputants to resolve conflicts: approach to wartime diplomacy, views on escalation, and receptiveness to mediation. I then evaluate China’s attempts to bring conflict to a close according to these three factors in the Korean War, Sino-Indian War, and Sino-Vietnamese War. I argue that China tends to entertain talks only with weaker opponents, rely on heavy escalation to bring about peace, and leverage outside parties less as empowered mediators and more as an additional source of pressure on its enemies. A subsequent analysis of authoritative Chinese strategic writings reveal that these patterns have been imbued in contemporary thought and, therefore, are likely to persist in future flashpoints. My findings add a new dimension to the war termination literature and have policy implications for regional peace and stability.

Introduction

Whether China will rise peacefully is hotly debated in both academic and policy communities. Power transition theory presents the possibility of conflict as largely dependent on relative power, with the most dangerous stage emerging when the rising power is approaching parity with the dominant power. Conflict can erupt then either because the rising power is dissatisfied with the current system and seeks to change it in its image or because the declining power launches a preventive war as a last-ditch attempt to hold onto its position in the international system (Organski and Kugler 1980; Gilpin 1981; Copeland 2000). Offensive realism focuses on balance of power more broadly and how increased power—and the expanding military capabilities that tend to accompany it—will inevitably encourage revisionist and expansionist behavior (Mearsheimer 2001). Scholars have tried to understand Chinese behavior through these theoretical lenses, most recently by evaluating the degree to which China harbors revisionist intentions, with a particular focus on its assertiveness in territorial disputes (Johnston 2013; Mastro 2014a,b). Leveraging international relations theory on how crises escalate to war has also been a fruitful avenue for evaluating the likelihood of conflict between China and the United States (Goldstein 2013; Swaine and Zhang 2006).

The heightened possibility of an armed conflict involving China, according to international relations theory, justifies an examination of Chinese strategic thinking about the onset, conduct, and termination of wars. China specialists have contributed greatly to our understanding of the first two components. A comprehensive study of past incidents of Chinese use of force internationally and domestically posits that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has not hesitated to move beyond coercive diplomacy to use force to further its policy goals, though with varying degrees of success (Scobell 2003, 2). Allen Whiting (2001) points out that early warning for deterrence, seizure of the initiative, risk acceptance, and risk management consistently characterize past cases of PLA deployment from 1950 to 1996. Alastair Iain Johnston (1998a) analyzes the Seven Military Classics of Ancient China and concludes that China has a strategic culture that emphasizes offensive action and flexibility, which still influences China’s use of military force against external threats to this day. Another systematic review of historical cases reveals that China responds with deterrent or coercive strategies primarily when it feels threatened or feels a sense of urgency to resolve a dispute (Godwin and Miller 2013). Thomas Christensen (2006) argues that China may use force even without a clear provocation if its leadership perceives a closing window of opportunity to create favorable long-term strategic trends. When China does respond with the use of force, Chinese leaders tend to rely on surprise attacks, inflicting casualties, creating tensions, and using deception to achieve a systematic advantage over its opponents, even those that are more technologically advanced (Burles and Shulsky 2000). … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Conflict and Chaos on the Korean Peninsula: Can China’s Military Help Secure North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons?” International Security 43.2 (Fall 2018): 84–116.

Will China intervene if war breaks out on the Korean Peninsula, and if so, does Beijing have the willingness and capabilities to deal safely with North Korea’s nuclear program? How can the United States account for China’s military role in this mission and work together with China to coordinate their shared interests and regional security?

Securing and destroying Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons would be the United States’ top priority in a Korean contingency, but scholars and policymakers have not adequately accounted for the Chinese military’s role in this mission. China’s concerns about nuclear security and refugee flows, its expanding military capabilities to intervene, and its geopolitical competition with the United States all suggest that China is likely to intervene militarily and extensively on the Korean Peninsula if conflict erupted. In this scenario, Chinese forces would seek to gain control of North Korea’s nuclear facilities and matériel. For the most part, China has the capabilities to secure, identify, and characterize North Korean nuclear facilities, though it exhibits weaknesses in weapons dismantlement and nonproliferation practices. On aggregate, however, Chinese troops on the peninsula would be beneficial for U.S. interests and regional security. Nevertheless, to mitigate the risks, the United States should work with China to coordinate their movements in potential areas of operation, share intelligence, and conduct combined nuclear security training.

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Cooperation and Competition with China: The Need for New Approaches,” Statement before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on East Asia, the Pacific, and International Cybersecurity Policy, “China Challenge, Part 2: Security and Military Developments” hearing, 5 September 2018.

On August 18, 2018, the Department of Defense released its seventeenth Annual Report to Congress on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. Since 2002, the annual reports have addressed the current and probable future course of the military-technological development of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), as well as the development of Chinese grand strategy, security strategy, military strategy, military organizations, and operational concepts through the next quarter-century.1 Since 2012, the reports have tripled in length to incorporate more information on China’s force modernization and special topics. This year’s report includes five special topics: China’s expanding global influence, China’s approach to North Korea and its diplomatic history and objectives, the PLA’s progress in becoming a joint force, overwater bomber operations, and Xi’s innovation-driven development strategy and the push to turn China into a science and technology powerhouse by 2050.

The annual report to Congress is a crucial tool for collating information and maintaining awareness of China’s growing military capabilities. Its systematic collection of data is a useful resource for scholars like me, and in this testimony I do not challenge the facts or assessments it presents. However, the U.S. government generally is less adept at understanding the implications of these developments, what they bode for the future, and the best way to respond. Therefore, in this testimony, I will discuss several misconceptions about cooperation and competition with China that may hinder U.S. attempts to deter Chinese aggression and compete effectively with China regionally and globally. I will also present recommendations about what Congress should do to improve the U.S.’s ability to interpret and respond to China’s challenge. The bottom line is that great power competition requires expanding U.S. efforts beyond traditional friends and allies, and the U.S. needs a whole-government approach to identifying and responding to the China challenge. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Xi Jinping and Kim Jong Un Keep Meeting—Here’s Why,” The National Interest, 26 June 2018.

China has been successful at keeping North Korea close and leveraging the relationship to achieve its own overarching goals beyond denuclearization.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un made his third visit to China in mid-June. The fact that Kim visited Beijing shortly after the Singapore summit was unsurprising—it was expected that Kim would have to debrief Xi and the two would want to strategize ways forward.

But the predictability of the visit does not diminish its importance. Specifically, the meeting allowed China to establish its influence behind the scenes, shape its image on the global stage, while also solidifying progress in its broader goals for the future of the peninsula and U.S.-China relations.

First, the broader geopolitical competition with the United States was a central consideration for the visit. Xi most likely wanted to clearly signal to the United States that China continues to play the pivotal role in shaping Kim. Chinese media reporting was not subtle on this point—highlighting that China’s dual suspension plan, which consisted of a pause of U.S. military exercise for a freeze in North Korean nuclear testing, was basically adopted in Singapore. According to Chinese media, this demonstrates China’s role as “a responsible great power” and that progress on the Korean nuclear issue “is indeed inseparable from China’s efforts.”

Second, to enhance its image as a regional power, Chinese official statements worked to promote an image of unity with North Korea. The post–meeting statements highlighted that the two sides had a “shared understanding” of a “series of issues of mutual concern including the prospect for the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” Reporting emphasized that even though there were highs and lows due to the nuclear issue, the bilateral relationship was strong, but evolving—and this bilateral relationship would greatly impact the regional environment.

Lastly, China wants to solidify progress towards a reduced U.S. military presence on the peninsula. Along these lines, the United States stopping joint exercises is only the first step. Beijing will likely begin to push for peace treaty talks that would undermine the legitimacy of a continued U.S. presence on the peninsula. China may even push Kim to bring up the U.S. deployment of the THAAD system to South Korea in the next round of talks, which could put the United States in a tough position. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, Testimony prepared for “Roundtable: China’s Role in North Korea Contingencies,” Hearing on China’s Policy Toward Contingencies in North Korea, US.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 12 April 2018.

How are the PLA and PAP preparing for a contingency in North Korea? What forces would be available to respond to a contingency, and what might those operations look like in different scenarios? In non-specialist terms, about many forces could China devote to a North Korean contingency, where would they come from, what would they be capable of doing?

If China intervened militarily on the Korean peninsula, the newly formed Northern Theater Command headquartered in Jinan would be in charge of the large ground force needed for any operations, from establishing a buffer zone to conducting more expansive combat operations. Force posture and exercises suggest that China is considering infiltrating North Korea by ground, air or sea, depending on the contingency and the degree to which China decides to intervene. For example, in September 2017, two days after North Korea’s fifth nuclear test, land and air force personnel conducted exercises while China’s strategic rocket force practiced shooting down incoming missiles over the waters close to North Korea.1 The People’s Armed Police (PAP), of which there are approximately 50,000 in the Northeast provinces, would most likely be in charge of securing the border in the meantime.2

There are three group armies in the Northern Theater Command (the 78th, 79th, and 80th), each with 30,000 to 50,000 troops that have their own Army Aviation Brigades (about 1,000 people) and SOF Brigades (about 2,000 people). These forces could be used in a ground invasion of North Korea, or in more limited contingencies, China could air drop in SOF, for example to secure critical sites, something the Z-10 brigades seem to be training for.3 The Aviation Brigades have a full mix of the transport (Mi-17, Z-8, Z-9) and attack helicopters (Z-10, Z-19) needed for close air support and lift capabilities into North Korea.4 If a conflagration were to ensue on the Korean peninsula, China could also pull Army Aviation brigades and SOF from Central Theater Command in addition to airborne units assigned to the PLAAF if it needed extra forces.5 The fact that Shandong was added to the Northern Theater command during the reorganization suggests that China may also have plans to enter North Korea by sea. Since 2015, the majority of Chinese naval drills have taken place in the Bohai and Yellow Sea off the coast of North Korea and Japan, including three known major exercises in the waters close to North Korea.

There is some opacity surrounding which forces would be in charge of handling North Korea WMD. China has reportedly created “sanfang” (三方) units (meaning three components—nuclear, biological, and chemical) within its military forces designed to deal with WMD; media reports suggest that the Chinese military has engaged in training and exercises to deal with nuclear contingencies with units participating from across all services in the military.6 There are indications that the Army is training to engage in radiation monitoring, contamination inspection, and decontamination.7 Also, the Chinese air force, border forces, militia, reserve forces, police, armed police, air defense, civil defense, and other specialized units would all be involved in the broader mission of protection against nuclear contamination.8 Once secured, technical experts from outside the PLA, likely from the Chinese Engineering and Physics Institute, the China Institute of Radiation Protection, and the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, would be invited in to support the mission.9 The Strategic Rocket Force would likely provide technical expertise as well, given its missile technology and nuclear weapons knowledge.10 … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “What China Gained From Hosting Kim Jong Un,” Foreign Affairs, 9 April 2018.

An Edge Over Washington, Not Friendship With Pyongyang

In late March, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, who had not stepped foot outside the hermit kingdom since taking power in 2011, traveled to Beijing to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping for the first time. The encounter came amid two decades of declining relations between North Korea and China, with its worst period yet under Xi—only six high-level bilateral exchanges had taken place over the past six years, compared to 54 during the presidency of his predecessor, Hu Jintao.

As I previously argued in the January/February issue of Foreign Affairs, Beijing had grown wary of Kim’s provocations and was “no longer wedded to North Korea’s survival.” It was remarkable, then, that Xi had extended the invitation to Kim. Has there been a sudden thaw in diplomatic relations? And if so, what does this apparent reversal signify?

On the surface, Xi appears driven by a desire for improved Sino–North Korean relations. During the Xi-Kim meeting, the Chinese media portrayed their two countries as ideological comrades, emphasizing their common interest in finding a peaceful solution to the security challenges on the peninsula and publishing photos of the two leaders sharing a warm embrace. But although the summit signals Beijing’s interest in pursuing productive relations with Pyongyang, Xi’s decision to meet with Kim represents less of a strategic shift than appearances might suggest. China is still not wedded to North Korea’s survival, and the countries’ “alliance” continues to be only in name. For Beijing, the ultimate goal of the meeting was not to patch up the relationship with Pyongyang but to shape the direction of upcoming U.S.–North Korean talks and to ensure that any outcome favors Chinese interests over those of the United States.

NEW ENVIRONMENT, NEW STRATEGY

Over the past few years, relations between Beijing and Pyongyang had deteriorated to the point where Chinese strategists and even military officers were suggesting that China might not take North Korea’s side in the event of a conflict on the peninsula. China had a lot to be upset about. Kim blatantly ignored its demands to refrain from provocative activities, conducting 86 missile tests and four nuclear tests since assuming power. Demonstrating a complete disregard for China’s interests, Kim had all of his nuclear tests conducted at the Punggye-ri site, about 100 miles from the Chinese border, which caused significant consternation in Beijing about nuclear fallout. Not only that, but Kim had a habit of conducting these tests during moments of significance for Beijing, such as during Xi’s May 2017 One Belt, One Road summit in Beijing, and, a few months later, during the BRICs summit in Xiamen. Xi may have felt personally disrespected by these tests, as it became obvious to the world that the timing of North Korea’s nuclear testing was no coincidence. … … …

***

Michael Chase and Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Long-Term Strategic Competition between the United States and China in Military Aviation,” in Tai Ming Cheung and Thomas G. Mahnken, eds., The Gathering Pacific Storm: Emerging U.S.-China Competition in Defense Technological and Industrial Development (Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2018): 111–37.

Given the bilateral tensions and importance of airpower to national defense, has long-term peacetime strategic competition between the United States and China in the military aviation sector emerged? Specifically, what is the degree to which each country is engaging in a cost imposing strategy to further their objectives at the other’s expense and how successful are attempts to influence each other’s decision-making calculus through such a competitive strategy?

The United States has enjoyed overwhelming military technological superiority in the post-Cold War era, but China has begun to chip away at this dominance. As distrust and strategic rivalry becomes more prominent in U.S.-China relations, this is helping to turn what had previously been parallel but separate military research and development efforts by both countries into a directly connected competition. This contest for leadership in defense technology and innovation promises to be a long-term and highly expensive endeavor for the United States and China

While there are some similarities between this emerging U.S.–China defense strategic competition and the twentieth-century Cold War, there are also significant differences. The U.S.–Soviet confrontation was primarily an ideological, geostrategic, and militarized rivalry between two countries and supporting alliances that were largely sealed from each other. This twenty-first century rivalry takes place against a backdrop of globalized interdependence, the blurring of military and civilian boundaries, and the growing prominence of geo-economic determinants.

U.S.-China military technological competition lies at the heart of the growing strategic contest between the United States and China. This is largely because this technological rivalry straddles the geostrategic and geo-economic domains covering drivers ranging from industrial policy and foreign direct investment to weapons development programs and threat assessments. Examining the nature of the U.S.-China defense technological competition requires a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the complex military, economic, innovation, and other drivers at play. Moreover, this technological race is still in the early stages of development and can be expected to grow larger, more complex, and more intense, so this book provides an invaluable

This is a pioneering examination of the burgeoning U.S.-China defense technological competition and provides perspectives not only from U.S. analysts but also from China and Russia. One of the major contributions of the book is the use of a competitive strategies framework that outlines some of the key considerations in the assessment of U.S.–China military technological competition. A rich and expansive discussion of this competition across a diverse range of domains, including air, sea, space, and emerging technologies, provides a comprehensive understanding of how complex and varied this contest is becoming, as well as its strategic and global implications. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “How China Ends Wars: Implications for East Asian and U.S. Security,” The Washington Quarterly 48.1 (2018): 45–60.

How has China historically approached diplomacy, mediation and escalation in conflict? To what degree are these historical patterns of behavior likely to manifest themselves in future conflicts, especially given all the changes to China’s internal and external environment since China’s last war in 1979? And how might the U.S. role in the region, and shifting power balances more generally, affect China’s decisions about war termination in future conflicts?

Scholars have long noted the higher likelihood of war that seems to accompany the rise and decline of great powers. Harvard professor Graham Allison most recently argued that war with China in the coming decades is “more likely than not,” if China and the U.S. do not go through the “tremendous effort” of avoiding it. Conflict could break out due to deliberate action or miscalculation in the South China Sea or the East China Sea, on the Korean Peninsula, or across the Taiwan Strait. A recent RAND report also notes that “despite cautious and pragmatic Chinese policies, the risk of conflict with the U.S. will grow in consequence, and perhaps in probability, as China’s strength and assertiveness increases in the Western Pacific.

But how would the People’s Republic of China (PRC) end wars? The real possibility of a conflict involving China justifies an examination of Chinese strategic thinking beyond deterrence, crisis behavior and conflict initiation to include how Beijing thinks about conflict termination. In particular, how has China historically approached diplomacy, mediation and escalation in conflict? To what degree are these historical patterns of behavior likely to manifest themselves in future conflicts, especially given all the changes to China’s internal and external environment since China’s last war in 1979? And how might the U.S. role in the region, and shifting power balances more generally, affect China’s decisions about war termination in future conflicts?

The answers to these questions have significant practical implications. First, this article enhances the understanding of Chinese strategic thinking by evaluating how the characteristics of China’s rise may affect how it attempts to bring any contemporary war to a close. Second, by recognizing some of China’s preferred strategies when it hopes to bring a conflict to a close, U.S. strategists can amend their own approach to counter aspects of Chinese wartime strategy that escalate and prolong conflicts to improve the chances of a short, limited war that ends on terms favorable to Washington.

This article proceeds as follows. First, I summarize from previous research how China approaches three critical factors that shape war termination: wartime diplomacy, escalation and third-party mediation. I then evaluate how China’s increased power, nationalism and participation in international institutions may affect each of these tendencies, respectively. I argue that China is more likely than ever to talk only to weaker opponents, to rely on escalation to bring about peace, and to leverage third parties, including international institutions, to pressure its adversaries to capitulate. I conclude with actionable recommendations, given these findings, for adjusting U.S. peacetime policy, posture and plans to better protect its interests. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “China’s End Run around the World Order,” CATO Unbound: A Journal of Debate, 14 March 2018.

Dr. Kori Schake has written an important essay about problematic assumptions and the challenges the United States faces if it is to take up the National Security Strategy mantle of the “great power competition” with China.

Unfortunately, the situation is more dire and more difficult, with fewer good options, than Schake lays out, for two main reasons.

China Will Only Grow Stronger

Schake admits that the hope that China would become more politically liberal as it grew richer was ill-founded. Her essay, however, still bears traces of optimism that political and economic weaknesses will ensure that China never reaches a level of power at which it can challenge the United States regionally, if not globally.

While she adeptly weighs all possibilities, I would argue that the United States is much more likely to be dealing with a strong China, with a stable Party that has the support of its people for its actions on the world stage. Even hypothesizing otherwise delays a good U.S. strategy response. Ever since Jiang Zemin made the bold decision to allow businessmen and entrepreneurs into the Party, a change of system has become less desirable for those benefiting the most from economic reforms. Coupled with the fact that the majority of Chinese citizens are still poor (500 million still live on less than $5.50 a day), live in rural areas, or make up an urban underclass of migrants, the “haves” are not particularly interested in giving the “have nots” power to determine China’s economic policies.

A more dominant theme in Schake’s essay is the idea that a democratic China would be easier for the United States to manage – and therefore that a democratic China is desirable from a strategic perspective. This is a problematic assumption. First, China’s national interests are not derived from its authoritarianism. A democratic China would also want to reduce its vulnerability to the United States and to have regional powers primarily accommodate its positions. This would necessitate a strategy of pushing out the U.S. military as much as possible, undermining U.S. alliances, and leveraging its economic power to coerce. Nationalism is more organic than many outside observers realize – often it is driven by netizens calling for the use of force while the government censors those calls, rather than the other way around. In short, a democratizing China would be a poster child for Mansfield and Snyder’s argument that democracies in transition can be the most dangerous nations.

Additionally, it seems that much of Schake’s view that things would be easier if China were a democracy is based on her interpretation of the power transition between the United States and Great Britain. While this area is beyond my expertise, I’ll just note that there are alternative explanations for why the transition was peaceful that rely more on realpolitik than on the countries’ similar democratic political systems. For example, Great Britain saw a closer, more immediate threat in Germany in the 1940s and therefore chose to join forces with the United States, and the United States did not have the desire to weaken Great Britain further for the same reason. Alternatively, it is possible that Great Britain realized that it was too weak to succeed in a conflict with the United States, and therefore chose accommodation. Either way, these explanations suggest that maintaining peace between China and the United States means the latter will concede its prime position in the international system without a fight, something at least this author hopes is not currently on the table. … … …

***

Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Why China Won’t Rescue North Korea: What to Expect If Things Fall Apart,” Foreign Affairs (January/February 2018).

The author argues that the conventional wisdom on what China would do if conflict broke out on the Korean Peninsula is dangerously out of date; and that China is likely to intervene militarily and extensively not in support of North Korea, but to protect its national interests.

U.S. officials have long agreed with Mao Zedong’s famous formulation about relations between China and North Korea: the two countries are like “lips and teeth.” Pyongyang depends heavily on Beijing for energy, food, and most of its meager trade with the outside world, and so successive U.S. administrations have tried to enlist the Chinese in their attempts to denuclearize North Korea. U.S. President Donald Trump has bought into this logic, alternately pleading for Chinese help and threatening action if China does not do more. In the same vein, policymakers have assumed that if North Korea collapsed or became embroiled in a war with the United States, China would try to support its cherished client from afar, and potentially even deploy troops along the border to prevent a refugee crisis from spilling over into China.

But this thinking is dangerously out of date. Over the last two decades, Chinese relations with North Korea have deteriorated drastically behind the scenes, as China has tired of North Korea’s insolent behavior and reassessed its own interests on the peninsula. Today, China is no longer wedded to North Korea’s survival. In the event of a conflict or the regime’s collapse, Chinese forces would intervene to a degree not previously expected—not to protect Beijing’s supposed ally but to secure its own interests.

In the current cycle of provocation and escalation, understanding where China really stands on North Korea is not some academic exercise. Last July, North Korea successfully tested an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of reaching the United States’ West Coast. And in September, it exploded a hydrogen bomb that was 17 times as powerful as the one dropped on Hiroshima. … … …

***