O’Rourke’s New CRS Report—“U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South & East China Seas”—Offers Latest CCG + PAFMM Info

If you have trouble accessing the website above, please download a cached copy here.

You can also click here to access the report via the new public CRS website.

KEY EXCERPTS:

p. 9

“Salami-Slicing” Strategy and Gray Zone Operations

p. 9

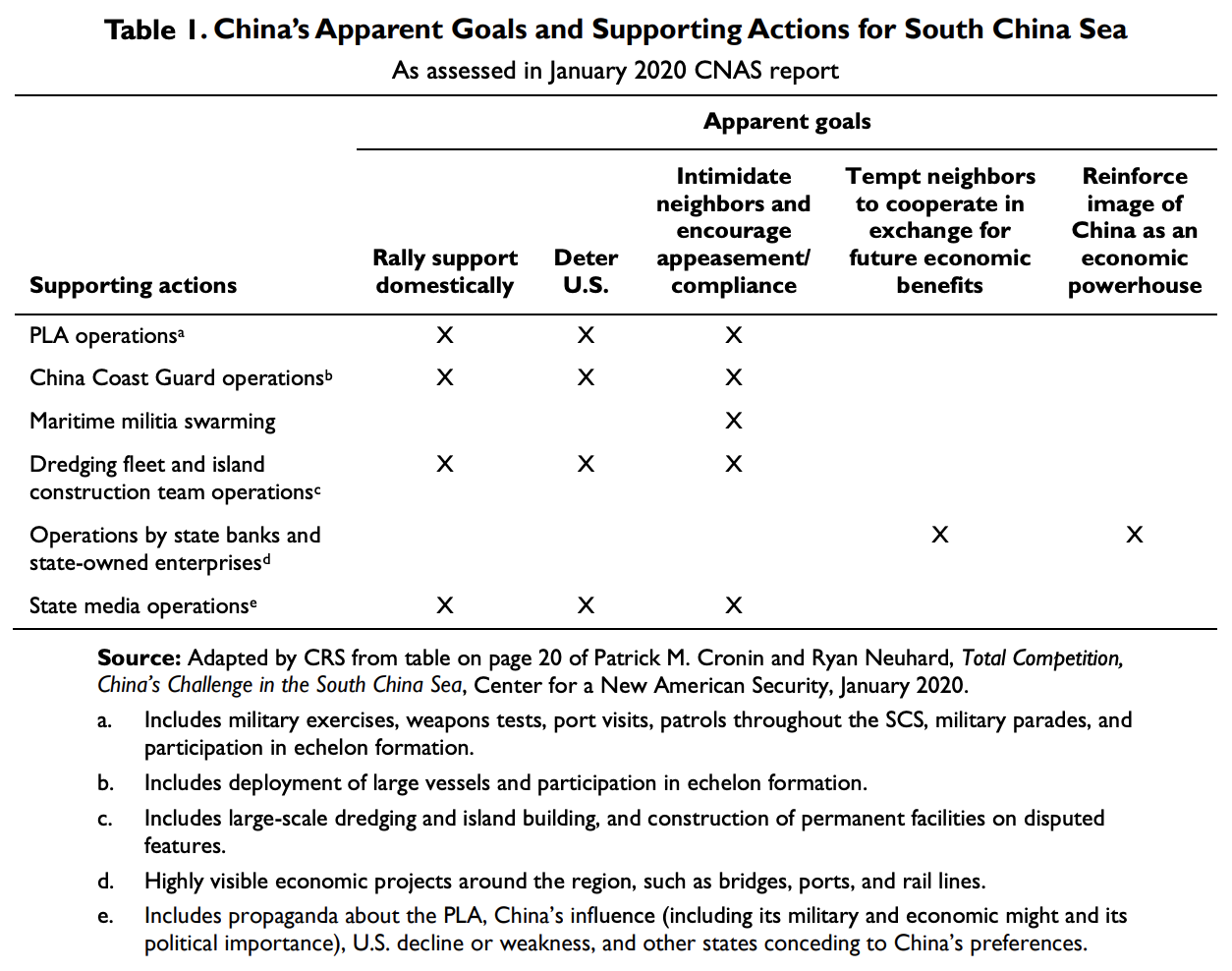

Observers frequently characterize China’s approach to the SCS and ECS as a “salami-slicing” strategy that employs a series of incremental actions, none of which by itself is a casus belli, to gradually change the status quo in China’s favor. Other observers have referred to China’s approach as a strategy of gray zone operations (i.e., operations that reside in a gray zone between

p. 10

peace and war), of incrementalism,31 creeping annexation32 or creeping invasion,33 or as a “talk and take” strategy, meaning a strategy in which China engages in (or draws out) negotiations while taking actions to gain control of contested areas.34 A March 17, 2020, press report in China’s state-controlled media stated that “Chinese military experts on Tuesday [March 17] suggested the use of non-lethal electromagnetic weapons, including low-energy laser devices, in expelling US warships that have been repeatedly intruding into the South China Sea in the past week.”35 A July 15, 2020, press report states

Its navy drills grab most of the attention, but China has also been quietly mounting a range of civilian and scientific operations to consolidate its claims in the South China Sea.

The diversified approach includes setting up a maritime rescue centre in Sansha, a prefecture-level city on Woody Island, which China calls Yongxing. It also involves undisclosed research and oil infrastructure.

Observers said the multipronged approach is meant to bolster China’s presence and consolidate its actual control over the waterway as other counties [sic: countries] repeatedly question its claims to the waters.36

Some observers argue that China is using the period of the COVID-19 pandemic to further implement its salami-slicing strategy in the SCS while the world’s attention is focused on addressing the pandemic.37 In a video conference with ASEAN foreign ministers in April 2020,

***

31 See, for example, Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang, “China’s Art of Strategic Incrementalism in the South China Sea,” National Interest, August 8, 2020.

32 See, for example, Alan Dupont, “China’s Maritime Power Trip,” The Australian, May 24, 2014.

33 Jackson Diehl, “China’s ‘Creeping Invasion,” Washington Post, September 14, 2014.

34 The strategy has been called “talk and take” or “take and talk.” See, for example, Anders Corr, “China’s Take-And-Talk Strategy In The South China Sea,” Forbes, March 29, 2017. See also Namrata Goswami, “Can China Be Taken Seriously on its ‘Word’ to Negotiate Disputed Territory?” The Diplomat, August 18, 2017.

35 Liu Xuanzun, “US Intrusions in S.China Sea Can Be Stopped by Electromagnetic Weapons: Experts,” Global Times, March 17, 2020.

36 Kristin Huang, “The Under-the-Radar South China Sea Projects Beijing Uses to Cement Its Claims,” South China Morning Post, July 15, 2020. See also Nguyen Thuy Anh, “Science Journals: A New Frontline in the South China sea Disputes,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), July 15, 2020.

37 See, for example, Tsukasa Hadano and Alex Fang, “China Steps Up Maritime Activity with Eye on Post-pandemic Order,” Nikkei Asian Review, May 13, 2020; Harsh Pant, “China’s Salami Slicing overdrive: It’s Flexing Military Muscles at a Time When Covid Preoccupies the Rest of the World,” Times of India, May 13, 2020; Veeramalla Anjaiah, “How To Tame Aggressive China In South China Sea Amid COVID-19 Crisis—OpEd,” Eurasia Review, May 14, 2020; Robert A. Manning and Patrick M. Cronin, “Under Cover of Pandemic, China Steps Up Brinkmanship in South China Sea,” Foreign Policy, May 14, 2020. Another observer, offering a somewhat different perspective, states

Recent developments in the South China Sea might lead one to assume that Beijing is taking advantage of the coronavirus crisis to further its ambitions in the disputed waterway. But it’s important to note that China has been following a long-term game plan in the sea for decades. While it’s possible that certain moves were made slightly earlier than planned because of the pandemic, they likely would have been made in any case, sooner or later. (Steve Mollman, “China’s South China Sea Plan Unfolds Regardless of the Coronavirus,” Quartz, May 9, 2020.)

A May 3, 2020, press report stated

Analysts reject the idea that Beijing has embarked on a new South China Sea campaign during the pandemic. But they do believe the outbreak is having an effect on perceptions of Chinese policy. “China is doing what it is always doing in the South China Sea, but it is a lot further along the road towards control than it was a few years ago,” said Gregory Poling, director of the Asia Maritime

p. 11

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reportedly stated: “It is important to highlight how the Chinese Communist party is exploiting the world’s focus on the Covid-19 crisis by continuing its provocative behaviour. The CCP [Chinese Communist Party] is … coercing its neighbours in the South China Sea.” 38

***

Transparency Initiative at CSIS, the Washington-based think-tank.

(Kathrin Hille and John Reed, “US Looks to Exploit Anger over Beijing’s South China Sea Ambitions,” Financial Times, May 3, 2020.)

38 As quoted in Kathrin Hille and John Reed, “US Looks to Exploit Anger over Beijing’s South China Sea Ambitions,” Financial Times, May 3, 2020. (Ellipsis as in original.)

USE OF COAST GUARD SHIPS AND MARITIME MILITIA ………………………………………………………………………………………. 13

p. 13

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

China asserts and defends its maritime claims not only with its navy, but also with its coast guard and its maritime militia. Indeed, China employs its coast guard and maritime militia more regularly and extensively than its navy in its maritime sovereignty-assertion operations. DOD states that China’s navy, coast guard, and maritime militia together “form the largest maritime force in the Indo-Pacific.”43

***

43 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2018, p. 16. See also Andrew S. Erickson, “Maritime Numbers Game, Understanding and Responding to China’s Three Sea Forces,” Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, January 28, 2019.

p. 18

In an April 22, 2020, statement, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated

Even as we fight the [COVID-19] outbreak, we must remember that the long-term threats to our shared security have not disappeared. In fact, they’ve become more prominent. Beijing has moved to take advantage of the distraction, from China’s new unilateral announcement of administrative districts over disputed islands and maritime areas in the South China Sea, its sinking of a Vietnamese fishing vessel earlier this month, and its “research stations” on Fiery Cross Reef and Subi Reef. The PRC continues to deploy maritime militia around the Spratly Islands and most recently, the PRC has dispatched a flotilla that included an energy survey vessel for the sole purpose of intimidating other claimants from engaging in offshore hydrocarbon development. It is important to highlight how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is exploiting the world’s focus on the COVID19 crisis by continuing its provocative behavior. The CCP is exerting military pressure and coercing its neighbors in the SCS, even going so far as to sink a Vietnamese fishing vessel. The U.S. strongly opposes China’s bullying and we hope other nations will hold them to account too.53

***

53 Department of State, “The United States and ASEAN are Partnering to Defeat COVID-19, Build Long-Term Resilience, and Support Economic Recovery,” Press Statement, Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State, April 22, 2020. See also A. Ananthalakshmi and Rozanna Latiff, “U.S. Says China Should Stop ‘Bullying Behaviour’ in South China Sea,” Reuters, April 18, 2020; Gordon Lubold and Dion Nissenbaum, “With Trump Facing Virus Crisis, U.S. Warns Rivals Not to Seek Advantage,” Wall Street Journal, April 20, 2020; Brad Lendon, “Coronavirus may be giving Beijing an opening in the South China Sea,” CNN, April 7, 2020; Agence France-Presse, “US Warns China Not to ‘Exploit’ Virus for Sea Disputes,” Channel News Asia, April 6, 2020.

p. 28

Recent Specific Actions

Recent specific actions taken by the Trump Administration include but are not necessarily limited to the following:

- As an apparent cost-imposing measure, DOD announced on May 23, 2018, that it was disinviting China from the 2018 RIMPAC (Rim of the Pacific) exercise.79

- In November 2018, national security adviser John Bolton said the U.S. would oppose any agreements between China and other claimants to the South China Sea that limit free passage to international shipping.80

- In January 2019, the then-U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral John Richardson, reportedly warned his Chinese counterpart that the U.S. Navy would treat China’s coast guard cutters and maritime militia vessels as combatants and respond to provocations by them in the same way as it would respond to provocations by Chinese navy ships.81

***

79 RIMPAC is a U.S.-led, multilateral naval exercise in the Pacific involving naval forces from more than two dozen countries that is held every two years. At DOD’s invitation, China participated in the 2014 and 2016 RIMPAC exercises. DOD had invited China to participate in the 2018 RIMPAC exercise, and China had accepted that invitation. DOD’s statement regarding the withdrawal of the invitation was reprinted in Megan Eckstein, “China Disinvited from Participating in 2018 RIMPAC Exercise,” USNI News, May 23, 2018. See also Gordon Lubold and Jeremy Page, “U.S. Retracts Invitation to China to Participate in Military Exercise,” Wall Street Journal,” Wall Street Journal, May 23, 2018. See also Helene Cooper, “U.S. Disinvites China From Military Exercise Amid Rising Tensions,” New York Times, May 23, 2018; Missy Ryan, “Pentagon Disinvites China from Major Naval Exercise over South China Sea Buildup,” Washington Post, May 23, 2018; James Stavridis, “U.S. Was Right to Give China’s navy the Boot,” Bloomberg, August 2, 2018. 80 Jake Maxwell Watts, “Bolton Warns China Against Limiting Free Passage in South China Sea,” Wall Street Journal, November 13, 2018. 81 See Demetri Sevastopulo and Kathrin Hille, “US Warns China on Aggressive Acts by Fishing Boats and Coast

p. 29

respond to provocations by them in the same way as it would respond to provocations by Chinese navy ships.79

- On March 1, 2019, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo stated, “As the South China Sea is part of the Pacific, any armed attack on Philippine forces, aircraft, or public vessels in the South China Sea will trigger mutual defense obligations under Article 4 of our Mutual Defense Treaty [with the Philippines].”80 (For more on this treaty, see Appendix B.)

- As discussed earlier, on July 13, 2020, Secretary Pompeo issued a statement that strengthened, elaborated, and made more specific certain elements of the U.S. position regarding China’s actions in the SCS.

- On August 26, 2020, Secretary Pompeo announced that the United States had begun “imposing visa restrictions on People’s Republic of China (PRC) individuals responsible for, or complicit in, either the large-scale reclamation, construction, or militarization of disputed outposts in the South China Sea, or the PRC’s use of coercion against Southeast Asian claimants to inhibit their access to offshore resources.”81

***

79 RIMPAC is a U.S.-led, multilateral naval exercise in the Pacific involving naval forces from more than two dozen countries that is held every two years. At DOD’s invitation, China participated in the 2014 and 2016 RIMPAC exercises. DOD had invited China to participate in the 2018 RIMPAC exercise, and China had accepted that invitation. DOD’s statement regarding the withdrawal of the invitation was reprinted in Megan Eckstein, “China Disinvited from Participating in 2018 RIMPAC Exercise,” USNI News, May 23, 2018. See also Gordon Lubold and Jeremy Page, “U.S. Retracts Invitation to China to Participate in Military Exercise,” Wall Street Journal,” Wall Street Journal, May 23, 2018. See also Helene Cooper, “U.S. Disinvites China From Military Exercise Amid Rising Tensions,” New York Times, May 23, 2018; Missy Ryan, “Pentagon Disinvites China from Major Naval Exercise over South China Sea Buildup,” Washington Post, May 23, 2018; James Stavridis, “U.S. Was Right to Give China’s navy the Boot,” Bloomberg, August 2, 2018.

80 Jake Maxwell Watts, “Bolton Warns China Against Limiting Free Passage in South China Sea,” Wall Street Journal, November 13, 2018.

81 See Demetri Sevastopulo and Kathrin Hille, “US Warns China on Aggressive Acts by Fishing Boats and Coast [CONTINUED…]

p. 30

- On March 1, 2019, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo stated, “As the South China Sea is part of the Pacific, any armed attack on Philippine forces, aircraft, or public vessels in the South China Sea will trigger mutual defense obligations under Article 4 of our Mutual Defense Treaty [with the Philippines].”82 (For more on this treaty, see Appendix B.)

- As discussed earlier, on July 13, 2020, Secretary Pompeo issued a statement that strengthened, elaborated, and made more specific certain elements of the U.S. position regarding China’s actions in the SCS.

- On August 26, 2020, Secretary Pompeo announced that the United States had begun “imposing visa restrictions on People’s Republic of China (PRC) individuals responsible for, or complicit in, either the large-scale reclamation, construction, or militarization of disputed outposts in the South China Sea, or the PRC’s use of coercion against Southeast Asian claimants to inhibit their access to offshore resources.”83

***

Guard; Navy Chief Says Washington Will Use Military Rules of Engagement to Curb Provocative Behavior,” Financial Times, April 28, 2019. See also Shirley Tay, “US Reportedly Warns China Over Hostile Non-Naval Vessels in South China Sea,” CNBC, April 29, 2019; Ryan Pickrell, “China’s South China Sea Strategy Takes a Hit as the US Navy Threatens to Get Tough on Beijing’s Sea Forces,” Business Insider, April 29, 2019; Tyler Durden, “‘Warning Shot Across The Bow:’ US Warns China On Aggressive Acts By Maritime Militia,” Zero Hedge, April 29, 2019; Ankit Panda, “The US Navy’s Shifting View of China’s Coast Guard and ‘Maritime Militia,’” Diplomat, April 30, 2019; Ryan Pickrell, “It Looks Like the US Has Been Quietly Lowering the Threshold for Conflict in the South China Sea,” Business Insider, June 19, 2019.

82 State Department, Remarks With Philippine Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin, Jr., Remarks [by] Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State, March 1, 2019, accessed August 21, 2019 at https://www.state.gov/remarks-withphilippine-foreign-secretary-teodoro-locsin-jr/. See also James Kraska, “China’s Maritime Militia Vessels May Be Military Objectives During Armed Conflict,” Diplomat, July 7, 2020. See also Regine Cabato and Shibani Mahtani, “Pompeo Promises Intervention If Philippines Is Attacked in South China Sea Amid Rising Chinese Militarization,” Washington Post, February 28, 2019; Claire Jiao and Nick Wadhams, “We Have Your Back in South China Sea, U.S. Assures Philippines,” Bloomberg, February 28 (updated March 1), 2019; Jake Maxwell Watts and Michael R. Gordon, “Pompeo Pledges to Defend Philippine Forces in South China Sea, Philippines Shelves Planned Review of Military Alliance After U.S. Assurances,” Wall Street Journal, March 1, 2019; Jim Gomez, “Pompeo: US to Make Sure China Can’t Blockade South China Sea,” Associated Press, March 1, 2019; Karen Lema and Neil Jerome Morales, “Pompeo Assures Philippines of U.S. Protection in Event of Sea Conflict, Reuters, March 1, 2019; Raissa Robles, “US Promises to Defend the Philippines from ‘Armed Attack’ in South China Sea, as Manila Mulls Review of Defence Treaty,” South China Morning Post, March 1, 2019; Raul Dancel, “US Will Defend Philippines in South China Sea: Pompeo,” Straits Times, March 2, 2019; Ankit Panda, “In Philippines, Pompeo Offers Major Alliance Assurance on South China Sea,” Diplomat, March 4, 2019; Mark Nevitt, “The US-Philippines Defense Treaty and the Pompeo Doctrine on South China Sea,” Just Security, March 11, 2019; Zack Cooper, “The U.S. Quietly Made a Big Splash about the South China Sea; Mike Pompeo Just Reaffirmed Washington Has Manila’s back,” Washington Post, March 19, 2019; Jim Gomez, “US Provides Missiles, Renews Pledge to Defend Philippines,” Associated Press, November 23, 2020; Reuters staff, “‘We’ve Got Your Back’—Trump Advisor Vows U.S. Support in South China Sea,” Reuters, November 23, 2020.

83 Department of State, “U.S. Imposes Restrictions on Certain PRC State-Owned Enterprises and Executives for Malign Activities in the South China Sea,” press statement, Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State, August 26, 2020. See also Susan Heavey, Daphne Psaledakis, and David Brunnstrom, “U.S. Targets Chinese Individuals, Companies amid South China Sea Dispute,” Reuters, August 26, 2020; Matthew Lee (Associated Press), “US Imposes Sanctions on Chinese Defense Firms over Maritime Dispute,” Defense News, August 26, 2020; Kate O’Keeffe and Chun Han Wong, “U.S. Sanctions Chinese Firms and Executives Active in Contested South China Sea,” Wall Street Journal, August 26, 2020; Ana Swanson, “U.S. Penalizes 24 Chinese Companies Over Role in South China Sea,” New York Times, August 26, 2020; Tal Axelrod, “US Restricting Travel of Individuals Over Beijing’s Moves in South China Sea,” The Hill, August 26, 2020.

p. 55

1972 Convention on Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs)

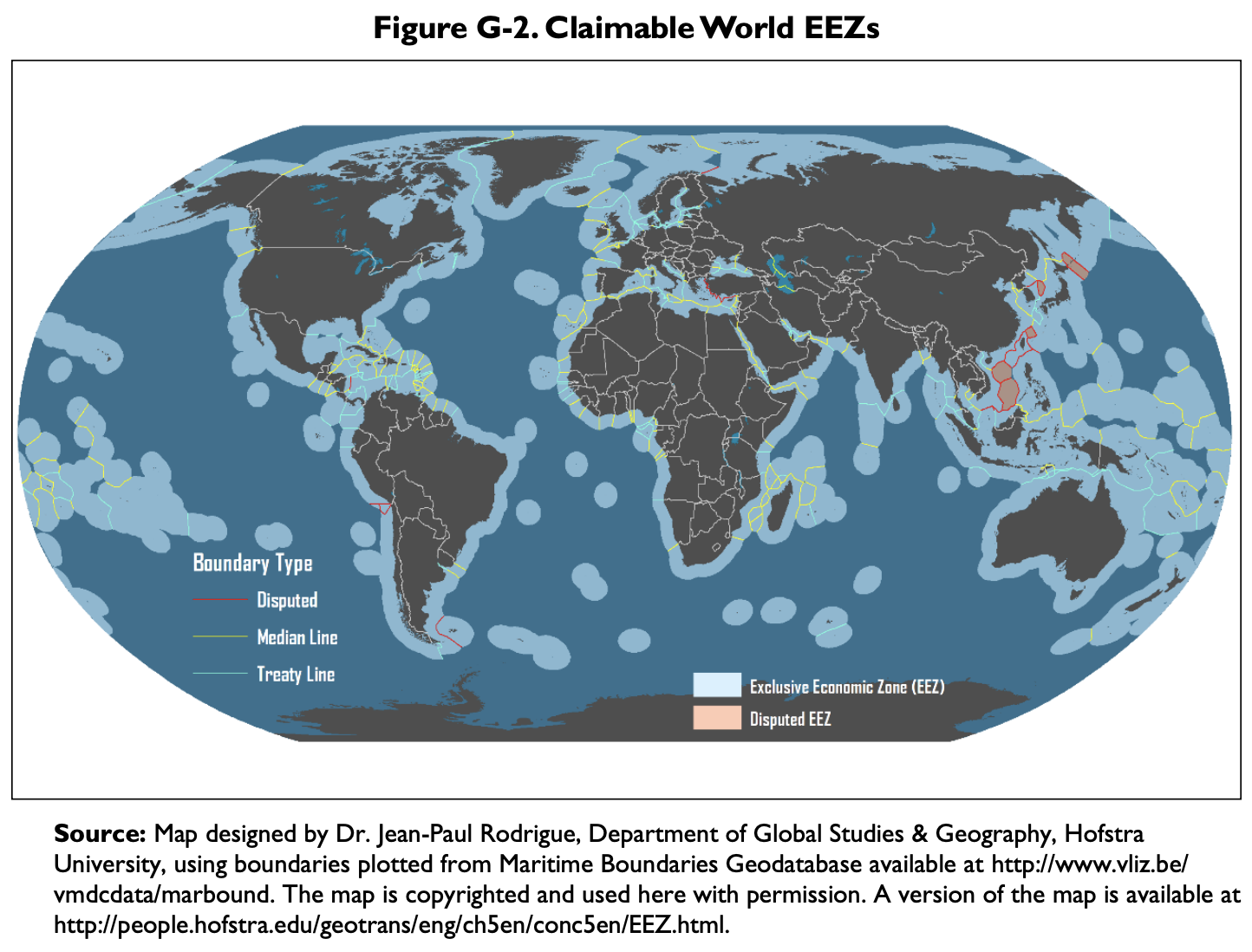

China and the United States, as well as more than 150 other countries (including all those bordering on the South East and South China Seas, but not Taiwan),138 are parties to an October 1972 multilateral convention on international regulations for preventing collisions at sea, commonly known as the collision regulations (COLREGs) or the “rules of the road.”139 Although [CONTINUED… ]

***

138 Source: International Maritime Organization, Status of Multilateral Conventions and Instruments in Respect of Which the International Maritime Organization or its Secretary-General Performs Depositary or Other Functions, As at 28 February 2014, pp. 86-89. The Philippines acceded to the convention on June 10, 2013.

139 28 UST 3459; TIAS 8587. The treaty was done at London October 20, 1972, and entered into force July 15, 1977. The United States is an original signatory to the convention and acceded the convention entered into force for the United States on July 15, 1977. China acceded to the treaty on January 7, 1980. A summary of the agreement is

[CONTINUED… ]

p. 56

commonly referred to as a set of rules or regulations, this multilateral convention is a binding treaty. The convention applies “to all vessels upon the high seas and in all waters connected therewith navigable by seagoing vessels.”140 It thus applies to military vessels, paramilitary and law enforcement (i.e., coast guard) vessels, maritime militia vessels, and fishing boats, among other vessels.

***

available at http://www.imo.org/About/Conventions/ListOfConventions/Pages/COLREG.aspx. The text of the convention is available at https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201050/volume-1050-I-15824- English.pdf.

140 Rule 1(a) of the convention.

p. 73

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

Coast Guard Ships

DOD states that the China Coast Guard (CCG) is the world’s largest coast guard.184 It is much larger than the coast guard of any country in the region, and it has increased substantially in size in recent years through the addition of many newly built ships. China makes regular use of CCG ships to assert and defend its maritime claims, particularly in the ECS, with Chinese navy ships sometimes available over the horizon as backup forces.185 The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) states the following:

Under Chinese law, maritime sovereignty is a domestic law enforcement issue under the purview of the CCG. Beijing also prefers to use CCG ships for assertive actions in disputed waters to reduce the risk of escalation and to portray itself more benignly to an international audience. For situations that Beijing perceives carry a heightened risk of escalation, it often deploys PLAN combatants in close proximity for rapid intervention if necessary. China also relies on the PAFMM—a paramilitary force of fishing boats—for sovereignty enforcement actions….

China primarily uses civilian maritime law enforcement agencies in maritime disputes, employing the PLAN [i.e., China’s navy] in a protective capacity in case of escalation.

The CCG has rapidly increased and modernized its forces, improving China’s ability to enforce its maritime claims. Since 2010, the CCG’s large patrol ship fleet (more than 1,000 tons) has more than doubled in size from about 60 to more than 130 ships, making it by far the largest coast guard force in the world and increasing its capacity to conduct extended offshore operations in a number of disputed areas simultaneously. Furthermore, the newer ships are substantially larger and more capable than the older ships, and the majority are equipped with helicopter facilities, high-capacity water cannons, and guns ranging from 30-mm to 76-mm. Among these ships, a number are capable of long-distance, long-endurance out-of-area operations. In addition, the CCG operates more than 70 fast patrol combatants ([each displacing] more than 500 tons), which can be used for limited offshore operations, and more than 400 coastal patrol craft (as well as about 1,000 inshore and riverine patrol boats). By the end of the decade, the CCG is expected to add up to 30 patrol ships and patrol combatants before the construction program levels off.186

In March 2018, China announced that control of the CCG would be transferred from the civilian State Oceanic Administration to the Central Military Commission.187 The transfer occurred on July 1, 2018.188 On May 22, 2018, it was reported that China’s navy and the CCG had conducted

***

184 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2018, p. 71.

185 See Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2015, pp. 3, 7, and 44, and Department of Defense, Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy, undated but released August 2015, p. 14.

186 Defense Intelligence Agency, China Military Power, Modernizing a Force to Fight and Win, 2019, pp. 66, 78. A similar passage appears in Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2018, pp. 71-72.

187 See, for example, David Tweed, “China’s Military Handed Control of the Country’s Coast Guard,” Bloomberg, March 26, 2018.

188 See, for example, Global Times, “China’s Military to Lead Coast Guard to Better Defend Sovereignty,” People’s Daily Online, June 25, 2018. See also Economist, “A New Law Would Unshackle China’s Coastguard, Far from Its Coast,” Economist, December 5, 2020; Katsuya Yamamoto, “The China Coast Guard as a Part of the China Communist Party’s Armed Forces,” Sasakawa Peace Foundation, December 10, 2020.

p. 74

their first joint patrols in disputed waters off the Paracel Islands in the SCS, and had expelled at least 10 foreign fishing vessels from those waters.189

Maritime Militia

China also uses the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM)—a force that essentially consists of fishing ships with armed crew members—to defend its maritime claims. In the view of some observers, the PAFMM—even more than China’s navy or coast guard—is the leading component of China’s maritime forces for asserting its maritime claims, particularly in the SCS. U.S. analysts in recent years have paid increasing attention to the role of the PAFMM as a key tool for implementing China’s salami-slicing strategy, and have urged U.S. policymakers to focus on the capabilities and actions of the PAFMM.190

***

189 Catherine Wong, “China’s Navy and Coastguard Stage First Joint Patrols Near Disputed South China Sea Islands as ‘Warning to Vietnam,’” South China Morning Post, May 22, 2018. For additional discussion of China’s coast guard, see Andrew S. Erickson, Joshua Hickey, and Henry Holst, “Surging Second Sea Force: China’s Maritime LawEnforcement Forces, Capabilities, and Future in the Gray Zone and Beyond,” Naval War College Review, Spring 2019; Teddy Ng and Laura Zhou, “China Coast Guard Heads to Front Line to Enforce Beijing’s South China Sea Claims,” South China Morning Post, February 9, 2019; Ying Yu Lin, “Changes in China’s Coast Guard,” Diplomat, January 30, 2019.

190 For additional discussion of the PAFMM, see, for example, Chung Li-hua and Jake Chung, “Chinese Coast Guard an Auxiliary Navy: Researcher,” Taipei Times, June 29, 2020; Gregory Poling, “China’s Hidden Navy,” Foreign Policy, June 25, 2019; Mike Yeo, “Testing the Waters: China’s Maritime Militia Challenges Foreign Forces at Sea,” Defense News, May 31, 2019; Laura Zhou, “Beijing’s Blurred Lines between Military and Non-Military Shipping in South China Sea Could Raise Risk of Flashpoint,” South China Morning Post, May 5, 2019; Andrew S. Erickson, “Fact Sheet: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM),” April 29, 2019, Andrewerickson.com; Jonathan Manthorpe, “Beijing’s Maritime Militia, the Scourge of South China Sea,” Asia Times, April 27, 2019; Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), March 11, 2019; Jamie Seidel, “China’s Latest Island Grab: Fishing ‘Militia’ Makes Move on Sandbars around Philippines’ Thitu Island,” News.com.au, March 5, 2019; Gregory Poling, “Illuminating the South China Sea’s Dark Fishing Fleets,” Stephenson Ocean Security Project (Center for Strategic and International Studies), January 9, 2019; Andrew S. Erickson, “Shining a Spotlight: Revealing China’s Maritime Militia to Deter its Use,” National Interest, November 25, 2018; Todd Crowell and Andrew Salmon, “Chinese Fisherman Wage Hybrid ‘People’s War’ on Asian Seas,” Asia Times, September 6, 2018; Andrew S. Erickson, “Exposed: Pentagon Report Spotlights China’s Maritime Militia,” National Interest, August 20, 2018; Jonathan Odom, “China’s Maritime Militia,” Straits Times, June 16, 2018; Andrew S. Erickson, “Understanding China’s Third Sea Force: The Maritime Militia,” Fairbank Center, September 8, 2017; Andrew Erickson, “New Pentagon China Report Highlights the Rise of Beijing’s Maritime Militia,” National Interest, June 7, 2017; Ryan Pickrell, “New Pentagon Report Finally Drags China’s Secret Sea Weapon Out Of The Shadows,” Daily Caller, June 7, 2017; Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, “Hainan’s Maritime Militia: All Hands on Deck for Sovereignty Pt. 3,” Center for International Maritime Security, April 26, 2017; Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, “Hainan’s Maritime Militia: Development Challenges and Opportunities, Pt. 2” Center for International Maritime Security, April 10, 2017; Andrew Erickson, “Hainan’s Maritime Militia: China Builds A Standing Vanguard, Pt. 1,” Center for International Maritime Security, March 25, 2017; Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA, China Maritime Report No. 1, China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College, Newport, RI, March 2017, 22 pp.; Michael Peck, “‘Little Blue Sailors’: Maritime Hybrid Warfare Is Coming (In the South China Sea and Beyond),” National Interest, December 18, 2016; Peter Brookes, “Take Note of China’s Non-Navy Maritime Force,” The Hill, December 13, 2016; Christopher P. Cavas, “China’s Maritime Militia a Growing Concern,” Defense News, November 21, 2016; Christopher P. Cavas, “China’s Maritime Militia—Time to Call Them Out?” Defense News, September 18, 2016; Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, “Riding A New Wave of Professionalization and Militarization: Sansha City’s Maritime Militia,” Center for International Maritime Security, September 1, 2016; John Grady, “Experts: China Continues Using Fishing Fleets for Naval Presence Operations,” USNI News, August 17, 2016; David Axe, “China Launches A Stealth Invasion in the South China Sea,” Daily Beast, August 9, 2016; Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy, “Countering China’s Third Sea Force: Unmask Maritime Militia Before They’re Used Again,” National Interest, July 6, 2016; Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy, “China’s Maritime Militia, What It Is and How to Deal With It,” Foreign Affairs, June 23, 2016.

p. 75

DOD states that “the PAFMM is the only government-sanctioned maritime militia in the world,” and that it “has organizational ties to, and is sometimes directed by, China’s armed forces.” 191 DIA states that

The PAFMM is a subset of China’s national militia, an armed reserve force of civilians available for mobilization to perform basic support duties. Militia units organize around towns, villages, urban subdistricts, and enterprises, and they vary widely from one location to another. The composition and mission of each unit reflects local conditions and personnel skills. In the South China Sea, the PAFMM plays a major role in coercive activities to achieve China’s political goals without fighting, part of broader Chinese military doctrine that states that confrontational operations short of war can be an effective means of accomplishing political objectives.

A large number of PAFMM vessels train with and support the PLA and CCG in tasks such as safeguarding maritime claims, protecting fisheries, and providing logistic support, search and rescue (SAR), and surveillance and reconnaissance. The Chinese government subsidizes local and provincial commercial organizations to operate militia ships to perform “official” missions on an ad hoc basis outside their regular commercial roles. The PAFMM has played a noteworthy role in a number of military campaigns and coercive incidents over the years, including the harassment of Vietnamese survey ships in 2011, a standoff with the Philippines at Scarborough Reef in 2012, and a standoff involving a Chinese oil rig in 2014. In the past, the PAFMM rented fishing boats from companies or individual fisherman, but it appears that China is building a state-owned fishing fleet for its maritime militia force in the South China Sea. Hainan Province, adjacent to the South China Sea, ordered the construction of 84 large militia fishing boats with reinforced hulls and ammunition storage for Sansha City, and the militia took delivery by the end of 2016.192

***

191 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2018, p. 71.

192 Defense Intelligence Agency, China Military Power, Modernizing a Force to Fight and Win, 2019, p. 79. A similar passage appears in Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2018, p. 72.

p. 89

A January 18, 2020, press report states

Before assuming his post as commander of the United States Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Philip S. Davidson issued a stark warning about Washington’s loosening grip in the fiercely contested South China Sea.

“In short, China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios, short of war with the United States,” Davidson said during a Senate confirmation hearing ahead of his appointment as the top US military official in the region in May 2018.

For many analysts, the dire assessment was a long-overdue acknowledgement of their concerns. Today, there is a growing sense it did not go far enough.

Washington’s strategic advantage in the waterway, which holds massive untapped oil and gas reserves and through which about a third of global shipping passes, has diminished so much, according to some experts, that it is powerless to prevent Beijing from restricting access during peacetime and could struggle to gain the upper hand even in the event of an outright conflict with Chinese forces.

China, which claims almost the entire waterway, has tipped the balance of power not just through a massive build-up of its navy, they say, but also through the presence of a de facto militia made up of ostensibly non-military vessels and an island-building campaign, the profound strategic value of which has been lost on US policymakers.… “The US has lost advantage throughout the spectrum of operations, from low-level interaction against China’s maritime militia to higher-end conflict scenarios,” said James Kraska, a former US Navy commander who lectures at the Naval War College. … … …

REPORT SUMMARY

In an international security environment described as one of renewed great power competition, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS forms an element of the Trump Administration’s more confrontational overall approach toward China, and of the Administration’s efforts for promoting its construct for the Indo-Pacific region, called the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP).

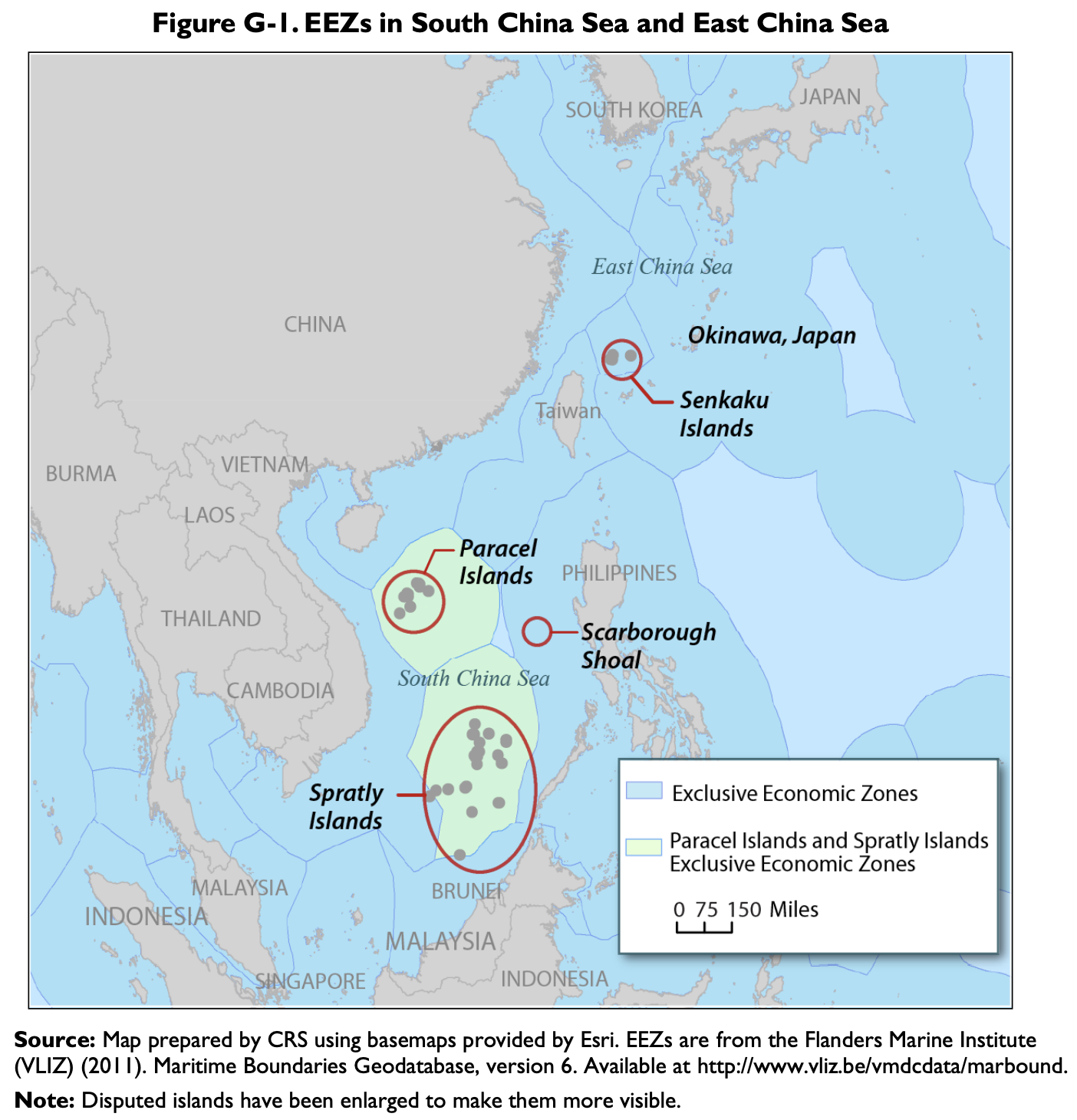

China’s actions in the SCS in recent years—including extensive island-building and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China’s near-seas region—meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea—could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.

Potential general U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. security relationships with treaty allies and partner states; maintaining a regional balance of power favorable to the United States and its allies and partners; defending the principle of peaceful resolution of disputes and resisting the emergence of an alternative “might-makes-right” approach to international affairs; defending the principle of freedom of the seas, also sometimes called freedom of navigation; preventing China from becoming a regional hegemon in East Asia; and pursing these goals as part of a larger U.S. strategy for competing strategically and managing relations with China.

Potential specific U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: dissuading China from carrying out additional base-construction activities in the SCS, moving additional military personnel, equipment, and supplies to bases at sites that it occupies in the SCS, initiating island-building or base-construction activities at Scarborough Shoal in the SCS, declaring straight baselines around land features it claims in the SCS, or declaring an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the SCS; and encouraging China to reduce or end operations by its maritime forces at the Senkaku Islands in the ECS, halt actions intended to put pressure against Philippine-occupied sites in the Spratly Islands, provide greater access by Philippine fisherman to waters surrounding Scarborough Shoal or in the Spratly Islands, adopt the U.S./Western definition regarding freedom of the seas, and accept and abide by the July 2016 tribunal award in the SCS arbitration case involving the Philippines and China.

The Trump Administration has taken various actions for competing strategically with China in the SCS and ECS. The issue for Congress is whether the Trump Administration’s strategy for competing strategically with China in the SCS and ECS is appropriate and correctly resourced, and whether Congress should approve, reject, or modify the strategy, the level of resources for implementing it, or both.

AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY—RONALD O’ROURKE

Mr. O’Rourke is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the Johns Hopkins University, from which he received his B.A. in international studies, and a valedictorian graduate of the University’s Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, where he received his M.A. in the same field.

Since 1984, Mr. O’Rourke has worked as a naval analyst for the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress. He has written many reports for Congress on various issues relating to the Navy, the Coast Guard, defense acquisition, China’s naval forces and maritime territorial disputes, the Arctic, the international security environment, and the U.S. role in the world. He regularly briefs Members of Congress and Congressional staffers, and has testified before Congressional committees on many occasions.

In 1996, he received a Distinguished Service Award from the Library of Congress for his service to Congress on naval issues.

In 2010, he was honored under the Great Federal Employees Initiative for his work on naval, strategic, and budgetary issues.

In 2012, he received the CRS Director’s Award for his outstanding contributions in support of the Congress and the mission of CRS.

In 2017, he received the Superior Public Service Award from the Navy for service in a variety of roles at CRS while providing invaluable analysis of tremendous benefit to the Navy for a period spanning decades.

Mr. O’Rourke is the author of several journal articles on naval issues, and is a past winner of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Arleigh Burke essay contest. He has given presentations on naval, Coast Guard, and strategy issues to a variety of U.S. and international audiences in government, industry, and academia.

CLICK BELOW FOR THE FULL TEXT OF SOME OF THE PUBLICATIONS CITED IN O’ROURKE’S CRS REPORT:

Andrew S. Erickson, “Maritime Numbers Game: Understanding and Responding to China’s Three Sea Forces,” Indo-Pacific Defense Forum Magazine 43.4 (December 2018): 30-35.

Peter A. Dutton and Andrew S. Erickson, “When Eagle Meets Dragon: Managing Risk in Maritime East Asia,” RealClearDefense, 25 March 2015.

Andrew S. Erickson, Joshua Hickey, and Henry Holst, “Surging Second Sea Force: China’s Maritime Law-Enforcement Forces, Capabilities, and Future in the Gray Zone and Beyond,” Naval War College Review 72.2 (Spring 2019): 11-25.

Andrew S. Erickson,“Fact Sheet: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM),” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 29 April 2019.

Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 11 March 2019.

Andrew S. Erickson, “Shining a Spotlight: Revealing China’s Maritime Militia to Deter its Use,” The National Interest, 25 November 2018.

Andrew S. Erickson, “Exposed: Pentagon Report Spotlights China’s Maritime Militia,” The National Interest, 20 August 2018.

Andrew S. Erickson, “Understanding China’s Third Sea Force: The Maritime Militia,” Harvard Fairbank Center Blog Post, 8 September 2017.

Andrew S. Erickson, “New Pentagon China Report Highlights the Rise of Beijing’s Maritime Militia,” The National Interest, 7 June 2017.

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, “Hainan’s Maritime Militia: All Hands on Deck for Sovereignty, Pt. 3,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 26 April 2017.

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, “Hainan’s Maritime Militia: Development Challenges and Opportunities, Pt. 2,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 10 April 2017.

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, “Hainan’s Maritime Militia: China Builds a Standing Vanguard, Pt. 1,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 26 March 2017.

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA, China Maritime Report 1 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, March 2017).

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, “Riding a New Wave of Professionalization and Militarization: Sansha City’s Maritime Militia,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 1 September 2016.

Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy, “Countering China’s Third Sea Force: Unmask Maritime Militia before They’re Used Again,” The National Interest, 6 July 2016.

Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy, “China’s Maritime Militia: What It Is and How to Deal With It,” Foreign Affairs, 23 June 2016.

Andrew S. Erickson and Emily de La Bruyere, “Crashing Its Own Party: China’s Unusual Decision to Spy on Joint Naval Exercises,” China Real Time Report (中国实时报), Wall Street Journal, 19 July 2014.

Andrew S. Erickson and Emily de La Bruyere, “China’s RIMPAC Maritime-Surveillance Gambit,” The National Interest, 29 July 2014.

Andrew S. Erickson, “PRC National Defense Ministry Spokesman Sr. Col. Geng Yansheng Offers China’s Most-Detailed Position to Date on Dongdiao-class Ship’s Intelligence Collection in U.S. EEZ during RIMPAC Exercise,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 1 August 2014.

Prashanth Parameswaran, “Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson on China and the Maritime Gray Zone,” The Diplomat, 14 May 2019.

Ryan D. Martinson and Andrew S. Erickson, “Re-Orienting American Sea Power For The China Challenge,” War on the Rocks, 10 May 2018.