The Challenges in Resetting U.S.–Southeast Asia Relations

Ja Ian Chong, “The Challenges in Resetting U.S.–Southeast Asia Relations,” East Asia Forum, 10 December 2020.

Ja Ian Chong is Associate Professor of Political Science at the National University of Singapore.

The incoming Biden administration needs to be ready for a Southeast Asia that is more skeptical of US commitment and careful about Beijing’s reactions. Southeast Asian capitals interested in cooperation need to be prepared to show initiative as Washington finds its footing amid the COVID-19 pandemic, economic woes and political turmoil.

Trans-Pacific relations will also be difficult to sustain if the United States wants engagement more than their Southeast Asian counterparts, or if Washington believes that it can ease its way back into a region without putting in the effort. Leaders in both Washington and Southeast Asia need to manage their own and each other’s expectations to make cooperation work.

Apprehension about the lack of US commitment and abandonment of the region is the mood among Southeast Asian countries…. The regional perspective sees Washington — across recent presidential administrations — as talking a big game with little practical gains to offer when push comes to shove. The George W Bush administration seemed to care little about Southeast Asia unless it concerned counter-terrorism. The Obama administration talked up ‘rebalancing’ but these efforts apparently fizzled out when China pressed its South China Sea claims, including Beijing’s reclamation and fortification of maritime features.

President Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership affirmed the lack of US commitment to Southeast Asia. The United States remains conspicuously absent from and silent about the recently concluded Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. These perceptions are unfair to Washington and its longstanding US cooperation in Southeast Asia, but they are part of the landscape that the Biden administration must navigate as it seeks to revitalise regional ties and multilateralism. … …

Efforts to ‘build back better’ collaborative trans-Pacific ties… requires patience, political will and some appetite for risk based on a clear-eyed appreciation of the limitations set by mutual expectations. These conditions provide the basis on which tough conversations about how the renewal of Southeast Asia–US cooperation can proceed — moving beyond showing up for regional meetings, saying the right things and running freedom of navigation operations in disputed waters. Re-engaging Southeast Asia on more substantive, multilateral terms, reinvigorating ties and forging new areas of collaboration will be difficult if leaders in Washington and Southeast Asian capitals do not fully grasp these realities.

View more posts by Ja Ian Chong

FURTHER ANALYSIS:

The Ian Chong Bookshelf: Rigorous Scholarship, Sino-Asian Revelations, Real-World Relevance

Among my many blessings, it has been my good fortune to have enjoyed such a wonderful time in Princeton’s Politics Ph.D. program. My classmates there included Ian Chong, whom I’ve subsequently met up at with conferences across the United States and Asia. We’ve also overlapped as affiliates at Harvard and of the Columbia-Harvard China and the World Program. Along the way, I’ve learned a tremendous amount from Ian concerning both the discipline of scholarship and the real world issues that he elucidates with it. His sharp intellect is always instructive and his sense of humor is infectious. Informing Ian’s work is a deep empathy for the people it might somehow help through better understanding and policies, making him a public intellectual in the very best sense. So, if you haven’t done so already, please take a look at Ian’s publications and presentations below. Whatever your focus, I’m confident you’ll find much of interest and relevance that is simply unavailable anywhere else.

BIOGRAPHY:

Dr. Ja Ian Chong is associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore. Dr. Chong’s work crosses the fields of international relations, comparative politics, and political sociology, with a focus on security issues relating to China and East Asia. He follows the interplay of social movements, politics, and foreign policy in East Asia closely. Dr. Chong was formerly was a 2019–20 Harvard-Yenching Visiting Scholar, 2013 Taiwan Fellow, 2012–13 East-West Center Asian Studies Fellow, and 2008–09 Princeton-Harvard China and the World Program fellow. He previously taught at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and worked with the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. and the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies in Singapore. He is an editor with the Singapore studies collective, AcademiaSG, and one of the founding editors of the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. He received the 2012 NUS Faculty Award for Promising Researcher.

Dr. Chong’s work appears in a number of journals, edited volumes, and newspapers, including the China Quarterly, European Journal ofInternational Relations, International Security, and Security Studies. He is author of External Intervention and the Politics of State Formation: China, Thailand, Indonesia – 1893-1952 (Cambridge University Press, 2012), recipient of the 2013–14 Best Book Award from the International Security Studies Section of the International Studies Association.

The focus of Dr. Chong’s teaching and research is on international relations, especially IR theory, security, Chinese foreign policy, and international relations in the Asia-Pacific. Of particular interest to him are issues that stand at the nexus of international and domestic politics, such as influences on nationalism and the consequences of major power competition on the domestic politics of third countries. He also enjoys examining historical material in his research. In addition to his academic background, he has experience working in think-tanks both in Singapore and in the United States. As such, he also probes the relationship between political science theory and policy. He strongly believes that the two can inform each other.

Dr. Chong is currently working on two major projects. The first examines how responses to power transition by non-leading states aggregate to affect the acuteness of competition among leading states. He looks empirically at East Asia following World War II, after the Vietnam War, and after the end of the Cold War. A second explores the micro-processes behind elite capture and influence operations both historically and in the present-day. This project considers several Southeast Asia cases in comparative perspective to cases in Europe, Australasia, North America, and Northeast Asia looking at ethnic diaspora as well as business and political elites.

莊嘉穎現任新加坡國立大學政治系副教授。研究領域跨越國際關係、比較政、政治社會學等領域,對同盟結構、政治制度轉型、爭議政治、外力介入、亞洲安全、中國外交和中美關係等專題。曾擔任哈佛燕京學社訪問學人、International Studies Review副編輯、National Bureau of Asian Research旗下Maritime Awareness Project國際諮詢委員,東西方中心(East-West Center)亞洲學人、國際暨戰略研究中心(CSIS)研究員。莊嘉穎現為新加坡研究合作社AcademiaSG其中的編輯,也是Georgetown Journal of International Affairs創刊編輯之一。

學術著作在《世界經濟與政治》、Asian Security、China Quarterly、Contemporary Southeast Asia、East Asia Forum、 European Journal of International Relations、International Security、Security Studies、The National Interest以及《二十世紀中國》等刊物發表。專書《External Intervention and the Politics of State Formation: China, Thailand, Indonesia – 1893-1952 》(劍橋大學初版社,2012年)榮獲國際研究學會(International Studies Association)國際安全研究組(International Security Studies Section)2013/4年度最佳圖書獎。

Ja Ian Chong adalah profesor madya sains politik di Universiti Nasional Singapura (NUS).

Karya Dr Chong melintasi bidang hubungan antarabangsa, politik perbandingan, dan sosiologi politik, dengan fokus pada isu keselamatan yang berkaitan dengan China dan Asia Timur. Dia mengikuti interaksi gerakan sosial, politik, dan dasar luar di Asia Timur secara dekat. Dr. Chong sebelumnya adalah Visiting Scholar di Institut Harvard-Yenching pada 2019/20, Taiwan Fellow 2012/3, East-West Center Asian Studies Fellow 2012/3, dan 2008/9 Fellow di Program Princeton-Harvard China dan Dunia. Dia sebelumnya bekerja dengan Pusat Kajian Strategik dan Antarabangsa (CSIS) di Washington, D.C., Amerika Syarikat dan Institut Pertahanan dan Kajian Strategik (IDSS) di Singapura. Dia pada masa ini seorang penyunting dengan kolektif pengajian Singapura tersebut, AcademiaSG, dan salah satu penyunting pengasas untuk Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

Karya Dr. Chong muncul dalam sejumlah jurnal, jilid yang diedit, dan surat khabar, termasuk China Quarterly, European Journal of International Relations, International Security, dan Security Studies. Dia adalah pengarang Intervensi Luar dan Politik Pembentukan Negara: China, Thailand, Indonesia – 1893-1952, Cambridge University Press, 2012, penerima Anugerah Buku Terbaik 2013/4 dari Bahagian Pengajian Keselamatan Antarabangsa di Persatuan Pengajian Antarabangsa.

Research Interests

- Security

- External Intervention

- Sovereignty

- Nationalism

- International and Domestic Political Institutions

- Politics of Hegemony and Domination

- Major Power Rivalry

- International Relations and Politics of the Asia-Pacific

- Chinese Foreign Policy

- U.S.-China Relations

- Chinese Politics

- Political Liberalisation and Foreign and Security Policy

- Alliance Politics

- Contentious Politics

- Social Movements

- Taiwan

- Hong Kong

- Northeast and Southeast Asian regional politics

- Influence operations

Teaching Areas

- International Relations

- Chinese Foreign Policy

- International Relations of the Asia-Pacific

- International Security

- External Intervention

- Sovereignty, State formation, and State-Building

- Alliance Politics

Courses Taught:

- China’s Foreign Policy

- International Relations Graduate Field Seminar

- International Relations in the Asia-Pacific

- International Security

- Foreign Policy and Diplomacy

- State and Society

PUBLICATIONS:

SINGLE-AUTHORED BOOKS

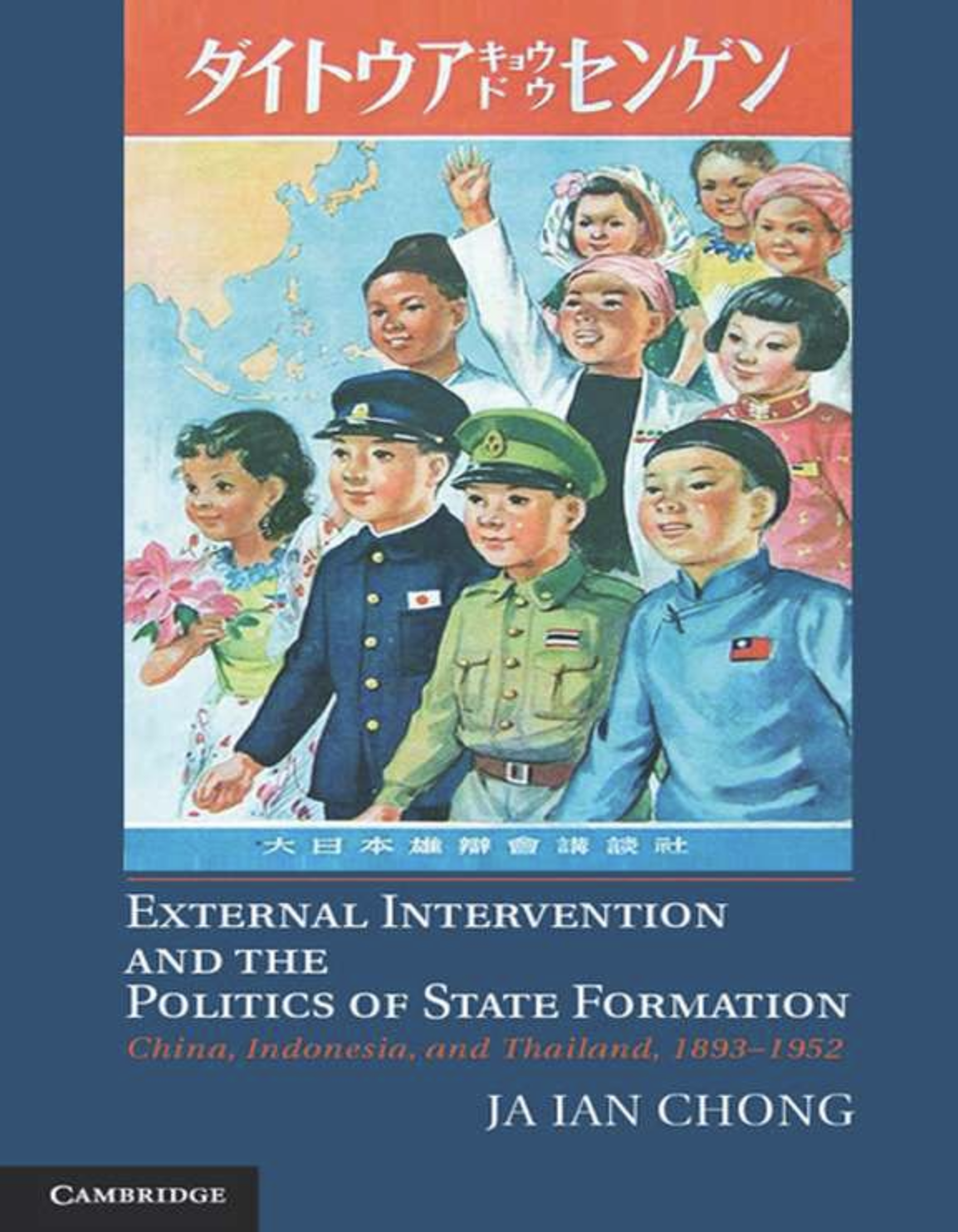

Ja Ian Chong, External Intervention and the Politics of State Formation: China, Indonesia, Thailand, 1893-1952 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Best Book Award 2013/4, International Security Studies Section, International Studies Association

This book explores ways in which foreign intervention and external rivalries can affect the institutionalization of governance in weak states. When sufficiently competitive, foreign rivalries in a weak state can actually foster the political centralization, territoriality, and autonomy associated with state sovereignty. This counterintuitive finding comes from studying the collective effects of foreign contestation over a weak state as informed by changes in the expected opportunity cost of intervention for outside actors. When interveners associate high opportunity costs with intervention, they bolster sovereign statehood as a next best alternative to their worst fear—domination of that polity by adversaries. Sovereign statehood develops if foreign actors concurrently and consistently behave this way toward a weak state. This book evaluates that argument against three “least likely” cases—China, Indonesia, and Thailand between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries.

REFEREED ARTICLES & BOOK CHAPTERS

Ja Ian Chong, “No Easy Answers: Southeast Asia and China’s Influence,” in Brian Fong, Wu Jieh-Min, and Andrew J. Nathan, eds., China’s Influences: Center-Periphery Tug-of-War across the Indo-Pacific (London: Routledge, 2020).

PRC influence in Southeast Asia can unsettle the region by heightening uncertainties and putting pressure on existing fault lines even as it promises economic growth and prosperity. China’s interests and actions intersect with deep-seated concerns about institutions, and political stability across Southeast Asia in ways that go beyond the commercial benefits from Chinese economic prominence. Beijing naturally seeks to advance its interests in the region and avert developments that negatively affect those concerns. Chinese pursuit of these objectives can erode the ability to of the main regional grouping, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), to promote region-wide collaboration and put pressure on the social compacts holding various polities together. Southeast Asian states need to carefully manage the effects that follow from the uneven distribution of gains, costs, and risks that come with enhanced engagement with China to ensure stable and sustainable cooperation. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Power in Comparison: Teaching and Studying Taiwan in Global Perspective,” American Journal of Chinese Studies 27.1 (April 2020): 52–57.

Taiwan is, in many ways, experiencing growing global visibility that is translating into more scholarly attention and interest. This situation results from Taiwan’s political liberalization and economic success which enables everything from sustained external contacts to artistic achievement and official outreach. An issue that now faces those committed to teaching Taiwan is how to consolidate and expand on existing awareness and concerns. One way to do so is to examine Taiwan-related topics in comparative perspective and actively bring it into discussions within academic disciplines and across different regions.

For social scientists, teaching Taiwan next to other cases and incorporating it into disciplinary debates raises the question: what is Taiwan a case of? Clearly establishing the conceptual bases for assessing Taiwan or Taiwan-based phenomena, alongside the cases with which they will undergo investigation, is crucial. Such considerations ground teaching with the intellectual rigor and methodological robustness that scholars and students expect and deserve. Careful comparison fosters theoretical innovation and the development of new perspectives that make Taiwan more accessible and relevant to students beyond area specialists. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “The Burdens of Ethnicity: Ethnic Chinese Communities in Singapore and Their Relations with China,” in Terence Chong, ed., Navigating Differences: Integration in Singapore (Singapore: Yusof Ishak Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2020), 165–85.

Communities in Singapore who trace their roots to what is today the PRC have a complex and sometimes difficult relationship with their place of ancestral origin. This was the case since migration to Singapore began en masse in the early nineteenth century. Much of the complication comes from how these communities and their diverse interests intersect with the concerns of other groups in Singapore, as well as politics and economics both locally and in China. The PRC’s recent global prominence and the efforts of its government to exercise influence externally muddies matters further for ethnic Chinese in Singapore. A solution is to develop a stronger sense of citizenship based around reasonable, substantive, and meaningful civic values and rights that transcend ethnicity, religion, and other narrower concerns. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “A Matter of Trust: Understanding Limited Support for Taiwan’s Defense Reform,” in Ryan Dunch and Ashley Esarey, eds., Taiwan in Dynamic Transition (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2020), 181–97.

Taiwan’s citizenry maintains a curious ambivalence toward military reform and modernization. It faces an increasingly powerful China that claims the right to use force against the island and builds future military operations against Taiwan integrally into its military planning. Despite this, there is limited public appetite for military spending, and defense related bud gets have been falling since the early 2000s, including support for projects that seek the transfer of more advanced technologies from the United States. These trends reflect a focus on doctrine, acquisitions, training, bureaucracy, and legislation when it comes to military and defense issues in Taiwan, including on reform.

There is relative inattention to civil-military relations, specifically the shedding of the military’s legacy as a tool for repression under martial law. Active participation in transitional justice efforts can help the military and Taiwan’s society come to terms with the former’s complicity, if not active role, during the White Terror, and allow for more active support of the military in Taiwan society. Such developments are an important next step in political reform for Taiwan’s military following its nationalization in the 1990s and key to enabling it to play a larger and more effective role in securing Taiwan in the face of growing threats. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Shifting Winds in Southeast Asia: Chinese Prominence and the Future of Regional Order,” in Ashley J. Tellis, Alison Szalwinski, and Michael Wills, eds., Strategic Asia 2019: China’s Expanding Strategic Ambitions (Seattle, WA: National Bureau of Asia Research, 2019), 143–74.

MAIN ARGUMENT

China’s growing economic, strategic, and political prominence have put it in a stronger position to shape developments in Southeast Asia. Beijing’s apparent disinterest in strategic restraint, the region’s inability to resolve collective action problems, and uncertainty over the future U.S. role in the region bolster China’s influence and preeminence there. Such trends reflect not just historically close ties between China and Southeast Asia but also China’s recent attempts to take the initiative in these relationships and divide the unity of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Should the U.S. wish to retain an active forward presence in Southeast Asia, more direct, frequent, and intense friction with China is likely. Robust regional partnerships and a credible rules-based order are key to weathering such tensions.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

- China’s resurgence in the region, coupled with uncertainty about U.S. regional leadership, implies the continued erosion of ASEAN centrality, which in the past has helped promote regional calm. If Southeast Asian states wish to maintain regional autonomy and avoid being torn between the U.S. and China, they must overcome collective action problems.

- ASEAN’s challenges in managing contentious U.S.-China relations mean there is mounting urgency for member states to decide whether to engage in serious organizational reform or adopt alternative institutional arrangements, including ones that may facilitate Chinese primacy.

- The U.S. must more concretely articulate and implement its Indo-Pacific strategy in Southeast Asia. The viability of the U.S. position in the region depends on clarity, consistency, and direction with ASEAN, individual Southeast Asian states, and other regional actors. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Is ASEAN Still ‘In the Driver’s Seat’ or Asleep at the Wheel?” East Asia Forum Quarterly 10.1 (January-March 2018): 3–5.

Over its history, ASEAN has reduced the possibility of war among its members and created a platform for member states to project their common concerns and to advance shared interests. ASEAN enabled what were relatively new, developing and in some cases small states collectively to play a sort of quasi-middle power role with which more powerful actors have to contend. But it may no longer be able to inhabit such a sweet spot.

Established at the height of the Cold War, ASEAN was entrenched around an understanding among conservative, anti-communist elites with at least some authoritarian sympathies. These elites accepted autonomy, mutual non-intervention, consensus on issues that required collective action and mutual restraint from the use of force as the basis for coordination, if not cooperation. Such commitments reduced tensions among member governments and enabled them to focus on consolidating domestic political authority, economic development and, where convenient, diplomatic cooperation.

ASEAN successfully carved out an area of steady economic growth and calm at a time when wars were raging in Indochina and when China was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution. As a result, external actors (including the major powers) accepted ASEAN prerogatives in Southeast Asia.

Riding on ASEAN’s Cold War successes, members consolidated the group’s position as East Asia’s premier regional organisation—due partially to the absence of similar arrangements in Northeast Asia. Other actors, including major powers like the United States, China and Japan, were therefore willing to accept ASEAN ‘centrality’ and its position ‘in the driver’s seat’ when it came to intra-regional cooperation.

These considerations characterised several ASEAN-focussed cooperation initiatives in East Asia between the 1990s and 2000s. They included the ASEAN Regional Forum, ASEAN+3, the East Asian Summit and the multilateral Chiang Mai Initiative for currency swaps after the 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis. The 1990s also saw ASEAN expand to cover most of Southeast Asia with the incorporation of Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and even Vietnam—the grouping’s former adversary.

The question for ASEAN now is whether its formula for success remains relevant. Finding common ground on pressing issues has become a growing challenge, the usual platitudes about solidarity and centrality notwithstanding. Recent efforts to manage disputes have had limited success, as demonstrated by the decades-long processes surrounding the Declaration of Conduct of Parties and the Code of Conduct over the South China Sea. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Deconstructing Order in Southeast Asia in the Age of Trump,” in “Roundtable: The Trump Presidency and Southeast Asia,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 39.1 (April 2017): 29–35.

With its primary stated goal of re-working the nature of America’s relationship with the rest of the world, the administration of President Donald Trump comes at an awkward time for Southeast Asia. Regional states are at a moment where they are adjusting domestic politics, their relationships with each other and the main inter-governmental organization, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). They are also responding to China, whose role in the region is evolving as Beijing moves into a new stage in its decades-long development into a major world power that is more ready to take robust positions on issues where its interests sometimes diverge with those of its neighbours. Amid these changes, Washington seems to be looking to move away from its longstanding commitment to liberalizing trade and investment in Asia, while taking a more openly muscular stance on security. Specifically, the United States under Trump is pondering possibilities for altering the longstanding basis for its economic and security exchanges with China, which includes adopting policies that differ more starkly from, or even oppose, those of Beijing.

Even though it is early days for the Trump administration, current developments suggest good reason to expect uncertainty, possibly even some turmoil, at least in the short term. The regional security and economic architectures in Southeast Asia—primarily the post-World War II US-backed order on the one hand and ASEAN and various arrangements built around it on the other–are especially unprepared for addressing major shocks or crises at this moment. Cleavages among ASEAN members and limited institutional capacity constrain the responses regional actors can take collectively, and may dampen individual reactions as well. Even though armed conflict among Southeast Asian countries remains unlikely, effective regional cooperation in the face of greater instability and uncertainty may be difficult to achieve and sustain without consistent American support. Given that Trump and his team still have ample time to learn, there is, of course, a possibility that the new administration can adapt to circumstances in Southeast Asia specifically, and the Asia Pacific more broadly.

The American Foundations of Regional Architecture

Regional cooperation in Southeast Asia continues to rest on the US-sponsored liberal international order, supplemented by ASEAN and its affiliated mechanisms. Southeast Asian states have experienced significant economic growth since the end of the Second World War and after the Cold War. Underpinning this economic success story is a cycle that ties capital from North America, Europe and Japan, as well as more recently South Korea and Taiwan, to raw materials and production networks across Asia that manufacture for North American and European consumers. Making this possible is a constant lowering of trade and investment barriers driven by a belief in the benefits of enterprise and wealth creation not only for their own sakes, but also as facilitators of social and political stability. Much of Southeast Asia’s prosperity—and indeed challenges with the environment and inequality—over the past seven or so decades come from being key economic nodes in the American-backed liberal international order.

Overseeing this economic order are the US-backed Bretton Woods institutions — the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) — which maintain the basic governing principles of the world economic system. Given that the US dollar denominates much of the world’s commercial activity, the US Federal Reserve too plays a critical role in the world economy via its influence over US interest rates. Despite talk of having alternative arrangements and institutions manage the world economy, the Bretton Woods institutions and the US dollar remain irreplaceable for the time being. Regional initiatives such as the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), intra- and extra-ASEAN free trade agreements, and even calls for the Chinese yuan to denominate regional trade or even become a reserve currency, operate as part of the liberal economic order and do not provide a substitute. Being integrated in the world economy means that Southeast Asia remains subject to the prevailing international economic order and its ordering principles. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong and Todd H. Hall, “One Thing Leads to Another: Making Sense of East Asia’s Repeated Tensions,” Asian Security 13.1 (March 2017): 20–40.

Both the East and Southeast China Seas have been home to a series of repeated episodes of tension between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its neighbors. Much of the existing literature either treats such episodes as isolated data points or as the manifestation of underlying structural factors. In this paper, we argue that repeated tensions can have important effects on subsequent interactions, generating emergent dynamics with dangerous consequences. What is more, we believe those dynamics to already be in play in several of the disputes within East Asia today. Examining recent developments in PRC-Japan and PRC-Philippines relations, we seek to shed light on how iterated episodes of tension are shaping the trajectory of interactions in both dyads. We believe these insights can inform efforts to understand relations in the region and beyond, given the growing frequency and intensity of repeated tensions among actors. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “America’s Asia-Pacific Rebalance and the Hazards of Hedging,” in David W.F. Huang, ed., Asia-Pacific Countries and the U.S. Rebalancing Strategy (London: PalgraveMacMillan, 2016), 155–73.

Hedging is a common approach that regional states in the Asia-Pacific seek to adopt in order to navigate between an ascendant China and a still dominant USA. Undergirding such a strategy is a desire among regional states to avoid “choosing” between the USA and China. However, there tends to be less policy and scholarly attention paid to how hedging strategies actually fare in securing the interests of regional states during power transition. This is of particular concern given the increasing tensions that seem to be afflicting the Asia-Pacific in spite of efforts by regional states to hedge, particularly following the American rebalance to Asia. This chapter examines the downside risks that may result from efforts by regional states to hedge between China and the USA. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Popular Narratives versus History: Implications for an Emergent China,” European Journal of International Relations 20.4 (December 2014): 939–64.

Closely associated with China’s growing prominence in international politics are discussions about how to understand Chinese history, and how such perspectives inform the way a stronger China may relate to the rest of the world. This article examines two narratives as cases, and considers how they fit against more careful historical scholarship. The first is the nationalist narrative dealing with Qing and Republican history, and the second is the narrative on the Chinese world order. Analyses of Chinese nationalism tend to see a more powerful China as being more assertive internationally, based in part on a belief in the need to address and overcome past wrongs. Studies of historical regional systems in Asia point to the role that a peaceful ‘Confucian’ ethos played in sustaining a stable Chinese-led order, and highlight the promise it holds for checking regional and international tensions. The two perspectives create an obvious tension when trying to understand China’s rise, which can suggest that using historical viewpoints to understand contemporary developments may be doomed to incoherence. This article argues that difficulties in applying knowledge of the past to analyses of China’s role in contemporary world politics indicate a relative inattentiveness to Chinese and Asian history. It illustrates how the nature of China’s rise may be more contingent on the external environment that it faces than popular received wisdom may indicate. The article suggests that a more extensive engagement with historical research and historiography can augment and enrich attempts to appreciate the context surrounding China’s rise. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong and Todd H. Hall,「反覆性緊張的後果研究:以四個東亞雙邊爭端為例」 [A Study on the Consequences of Repeated Tensions: Examining Several Cases of Dyadic Disputes in East Asia], World Economics and Politics (《世界經濟與政治》) 9 (2014): 50–74.

In this paper, we build on existing work on evolving rivalries, learning, and spiral models, but adding additional insights from more recent work on emotions within international relations. We believe that iterated, unresolved episodes of tension need to be viewed in an integrated fashion, whereby the previous event sets the context for the next. With each outbreak of tension, the political terrain shifts, and knowing how and where these shifts can occur can help to explain the dangers that may subsequently emerge. More specifically, we highlight mechanisms through which iterative episodes of tension can interact with known psychological dynamics to shape political attitudes, perceptions of new information, and also the political incentives actors face. In doing so, we offer a cautionary warning to those who would assume that crises are resolved when tensions subside. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong and Todd H. Hall, “The Lessons of 1914 for East Asia Today? Missing the Trees for the Forest,” International Security 39.1 (Summer 2014): 7–43.

A century has passed since the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo set in motion a chain of events that would eventually convulse Europe in war. Possibly no conflict has been the focus of more scholarly attention. The questions of how and why European states came to abandon peaceful coexistence for four years of armed hostilities—ending tens of millions of lives and several imperial dynasties—have captivated historians and international relations scholars alike.

Today, Europe appears far removed from the precipice off which it fell a century ago. If anything, most European states currently seem more concerned about the damage potentially caused by financial instruments than instruments of war. On a global scale, the destructive power of contemporary weaponry so dwarfs armaments of that earlier era that some scholars have argued great power war to be obsolete.1 Additionally, the international community has established international institutions, forums, and consultative mechanisms to channel conflict away from the battlefield and into the conference room.

Yet, not only do the great power relations of that era persist in intriguing scholars; as Steven Miller and Sean Lynn-Jones observe, they also continue to “haunt,” for “they raise troubling doubts about our ability to conduct affairs of state safely in an international environment plagued by a continuing risk of war.”2 In many ways, these doubts have assumed a renewed salience as the world enters an era of significant ambiguity. Possibly foremost among the sources of this ambiguity is the economic and military growth of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a development that has introduced uncertainty into the strategic relations among great powers, particularly the PRC and the United States, and serves as a reminder that history may be far from over.

Indeed, there would seem to be striking parallels between the situation facing the PRC and the United States in this century to that of Imperial Germany and Great Britain at the beginning of the last. Both situations involve late developing states confronting entrenched liberal great powers in positions of global military dominance. In the common narrative of the latter pair, Imperial Germany—dissatisfied with its lot in the world, seeking to expand its influence, generate a global presence, and “take its place in the sun”—set itself on a path to conflict with an entrenched yet declining Great Britain wary to relinquish its position. The result was deteriorating relations, security competition, and finally the tragic outbreak of World War I.

The lesson that emerges from this analogy is thus a worrying one, pointing to the dangers of war between a rising and an established power. It encourages observers to be on the lookout for possible signs of dissatisfaction in the PRC, to question whether it is seeking to dethrone the United States or contest the existing global order in ways similar to Germany a century ago. Much work has already been done on this topic; in fact, within the community of international relations scholars, it has arguably had a key role in framing debates about the future of the PRC in the international system.3 We believe, however, the analogy across these two great power dyads to be of limited use. We reach this conclusion not only because of contextual differences between the lead-up to World War I and the present that many scholars of international relations have already identified. It is also because of the more general way in which analogies can function to limit and distort the comprehension of problems. That said, we believe that the experience of World War I itself remains rife with lessons possibly more relevant now than ever. The outbreak of World War I was a complex, yet contingent, event to which multiple factors contributed, absent any one of which history might have unfolded quite differently. Although not necessarily portents of another full-scale world war, the factors we identify do have the potential to exacerbate the risk of tensions or increase the likelihood of conflict in East Asia. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Chinese Nationalism Reconsidered,” in Kate Zhou, Shelley Rigger, and Lynn T. White, III, eds., Democratization in China, Korea, and Southeast Asia? Local and National Perspectives (New York, NY: Routledge, 2014), 232-47.

A pervasive narrative for the years from the First Opium War (1839-1842) and the mid-twentieth century is that it marks China’s “Century of National Humiliation” by external powers. According to this view, military defeat, foreign economic and political domination, and domestic upheaval characterized this period. What follows is that China emerged from this dishonor with victory over Japan during World War II and the Communist Revolution. This position suggests that the Chinese experience of success rests on persistently struggling for political unity and national interest even against the greatest of odds.1 An obvious implication of this understanding is that the Chinese people and state should assert what is, in their view, “right.” I propose to highlight not just recollections of China emerging from a position of purported weakness in this chapter, but to furnish more historical context and detail about how this development unfolded. I pay particular attention to tensions that may exist between popular nationalist-influenced recollections of key events during the “century of humiliation” and data garnered from closer historical analyses of these episodes.2 Such an approach can underscore some of the constraints and pressures nationalist-based mobilization and resistance face. This can assist in underlining some of the key dynamics that helped to shape contemporary Chinese nationalism and its effects on today’s Chinese foreign as well as domestic policy.

To examine this issue, I begin by briefly recapping key features common to popular nationalist understandings of China’s recent past before examining where these accounts diverge from recent historical research and discussing the implications of such differences. Exploring the range of divergence in expressions of nationalism in China may prove particularly fruitful given its apparent influence on that polity’s modern history and current development. Received wisdom, at least among political scientists and policy analysts, tends to take Chinese nationalism as especially forceful, immutable, and consistent, varying perhaps only in intensity over particular issues and during specific moments in time. Significant departures from this position in the historical record may suggest that much of this potency may depend substantively on historical contingency and degrees of success in purposeful popular mobilization. This may imply that Chinese nationalism may only be as much of an impediment to cooperation and even compromise as prominent interested parties and groups in China allow, especially over longer time horizons. That mainstream Chinese nationalist accounts show substantial malleability implies that other nationalist perspectives too may be similarly subject to effective political machinations, much like many widely-held beliefs. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Malaysia and Singapore’s Online Response to U.S. ‘Rebalancing’,” Asia Politics and Policy 5.2 (April 2013): 314–47.

If there is one thing about the online response to the United States’ “rebalance” to Asia in Singapore and Malaysia, it is the lack of sustained popular discussion. Most vocal on the topic are professional pieces by foreign policy-related think tanks and institutions. The professional sites tend to offer more systematic analyses of the rebalance and broader related issues. In comparison, nonprofessional commentary on blogs and other sites tend to be event-driven and focuses on particular episodes relating to the rebalance. Readers of the nonprofessional sites tend to be members of the public with a general interest in current affairs, but not necessarily regional or international politics.

Professional, Institutional Sites

Web sites operated by think tanks in Malaysia and Singapore contain some in-depth material on the U.S. rebalance, but more generally, information on U.S.-East Asian relations and U.S.-China relations. Good examples of these Web sites are those of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS; http://www.rsis.edu.sg/), the Institute for Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia (http://www.isis.org.my/), and the Singapore Institute of International Affairs (http://siiaonline.org/content.aspx?page=Home). These sites feature pieces that examine everything from the overall strategic outlook on the region to analyses of specific policies. For instance, the ISIS Web site featured an article by Firdaos Rosli (2012) that came out in New Straits Times: “Which Trade Pact Should We Pick?” The article tried to explore the pros and cons of the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which respectively reflect the U.S. rebalance and regional responses. Likewise, RSIS Commentaries regularly carry pieces considering the various aspects of tensions in the South China Sea, including the U.S. and Chinese roles.

Mostly written by academics and policy makers, these sites tend to be reference points for specialist debates about the rebalance and U.S.-China relations. Indeed, the official affiliations of some of the authors published by these sites suggest that they are fora for floating trial balloons or the informal interpretation of official positions. Authors are sometimes officials or active participants in quasi-official track two or…. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “China-Southeast Asian Relations since the Cold War,” in Andrew T.H. Tan, ed., East and South-East Asia: International Relations and Security Perspectives (New York, NY: Routledge, 2013).

China’s ties with Southeast Asia since the Cold War may anticipate some of the broader trends in Chinese foreign policy. Of note, may be Beijing’s efforts to navigate between assurance and assertiveness when trying to work with smaller actors as China becomes a major world power. Southeast Asia’s physical proximity to China may make the advantages and constraints of power asymmetry especially acute for the various governments, including Beijing. China’s movement from cautious economic engagement in Southeast Asia from the early 1990s to multilateralism between the late 1990s and late 2000s through its more muscular policy from the late 2000s may be representative of an evolving foreign policy outlook. In this regard, the development of China’s relations with Southeast Asia from the end of the Cold War may be worth closer scrutiny. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “How External Intervention Made the Sovereign State: Foreign Rivalries, Local Complicity, and State Formation in Weak Polities,” Security Studies 19.4 (October–December 2010): 623–55.

From post-World War II decolonization to establishing order in war-torn polities today, external intervention can play an important role in fostering sovereign statehood in weak states. Much attention in this regard emphasizes local reactions to outside pressures. This article augments these perspectives by drawing attention to ways that foreign actors may affect the development of sovereignty through their efforts to work with various domestic groups. Structured comparisons of China and Indonesia during the early to mid-twentieth century suggest that active external intercession into domestic politics can collectively help to shape when and how sovereignty develops. As these are least likely cases for intervention to affect sovereign state making, the importance of foreign actors indicates a need to reconceptualize the effects of outside influences on sovereignty creation more broadly. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Lost in Transition, or Why Non-Leading States Should Concern Washington and Beijing,” East Asia Forum Quarterly 2.2 (July-September 2010.

Power transitions in international relations—real or perceived—are unsettling. This is especially so for non-leading states. Their interests depend on shifts in the international system that they cannot shape. Leading powers should, however, pay attention to how non-leading states react to expectations of change in the global political environment. Their reactions, especially when considered together, can exacerbate or moderate security dilemmas among the leading powers and has the potential to affect regional and even systemic stability. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Breaking Up is Hard to Do: Foreign Intervention and the Limiting of Fragmentation in the Late Qing and Early Republic, 1893 – 1922,” Twentieth Century China 35.1 (November 2009): 75–98.

This article examines why and how persistent political fragmentation existed alongside continued centralization in late Qing and early Republican China. By analyzing new archival material and existing scholarship, the piece argues that external intervention helped preserve the viability of a single Chinese state even as the same phenomenon also spurred ongoing fractionalization. Because major powers’ governments generally saw China as an area of secondary strategic import, they tried to avoid armed conflict over the polity and seek accommodation. Since outside powers diverged in their objectives, they settled on sponsoring indigenous partners, notably various militarists as well as the Chinese Nationalists, to sustain a degree of central government rule alongside substantial regional autonomy. In reconsidering the effects of foreign intervention, this article engages the discussion on political consolidation in the late Qing and early Republic, and suggests that overly stressing integration or division tends to present incomplete accounts of the issue.

INTRODUCTION

The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been. —Luo Guanzhong, Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi).1

What is remarkable about China during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is that it held together. Given the various internal and external pressures, the polity appeared to be heading toward complete and utter disintegration. Population expansion, a series of rebellions and natural disasters, and an erosion of central government capabilities pushed at the seams from within.2 From without, foreign powers looked set to partition the Chinese polity just as they did everywhere from Africa to Southeast Asia—this was, after all, the high age of imperialism. The question, then, is how the late Qing and early Republic maintained sufficient political unity to provide the foundations for the later development of a centralized, sovereign Chinese state in spite of these pressures.

The key to China’s resilience against complete fragmentation between the end of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth lay in the nature of external competition over and intervention into the polity. That the foreign governments most active in and around China generally saw it as an area of secondary import, and not worth a major armed conflict, gave the various outside powers a stake in seeking settlements among themselves. This brought simultaneous external financial, economic, and even military backing for central governments as well as various regional administrations, a dynamic that kept the Chinese polity whole even as it deepened fractures across the country. By highlighting the role of foreign actors in holding China together even as they simultaneously fostered growing fractiousness, this article takes seriously the multifaceted characteristics of external intercession into domestic politics. In doing so, I forward a perspective that locates the development of the modern Chinese state more fully within the global context of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.3

That external intervention helped hold China together did not exclude it from contributing to the breakdown in central government rule. The peculiarities of major power competition over the Chinese polity produced two countervailing forms of pressure. On one hand, major powers like Germany, Japan, Russia, and France extended financial aid, military assistance, and political support to various local actors within their respective regions of interest in efforts to exclude rivals from these areas. This gave local political agents the wherewithal to stand up to the central government, whether it was under the Qing court or a militarist clique. On the other hand, largely British and American attempts to avoid disadvantaged access vis-à-vis the other great powers brought attempts to shore up central government rule through the provision of economic as well as political backing to those in power at the capital. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, 〈主權國的興起與世界政治架構: 現代主權在華夏的誕生〉[“The International System and the Emergence of the Sovereign State: The Birth of the Modern Sovereign State in the Chinese World”], in 《天體、生體與國體:迴向世界的漢學》[Heavenly Bodies, Physical Bodies, and Political Bodies: Sinology Faces the World], 祝平次 楊儒賓 編 [Chu Ping-tzu and Yang Rur-bin, eds.], (台北 [Taipei]: 國立台灣大學出版中心 [National Taiwan University Publishing Centre], 2005年 [民94])[2005]), 407–57.

「現代化」與「對外」主權的興起:華夏政治觀面對國際現實的一刻 「對外主權」,在今天中國政治思想中佔了一定的地位。任何有中華文化背景的政治實體,都不自覺地為了本身的權益,竭力訴求主權自主,限制或杜絕外來勢力干預,及確保國際間法律平等待遇。這反映了它們在「對外主權」觀念上的基本共識。 為什麼要用「對外主權」這個名詞?確切地說「主權」是個雙面的觀念,它有「對外」和「對內」兩方面的功能:對內,它是一個行政體制,在明確的地理範圍之內擁有絶對的統治權,如立法、施政、司法、警察和國防等;對外,它代表境內人民及各個團體,處理境外事物。 事實上,今天國際上所遵守的「對外主權」,是從一系列不同的概念沿革而成,如「明訂版圖界線」、「版圖界線的不可侵犯」、「政治行為自主」、「各國法律平等」等。而以上的概念,在廿世紀前,「前現代」中國政治思想中卻非常罕見。當時「對外主權」的概念,是源自十七世紀的歐洲,然後隨著辛亥革命、五四運動、北伐、國共內戰等社會、政治、思想「現代化」的過程逐漸發展演變,成為今天中國政治的主流思想。無論是處理疆域問題、國際交流、或尋求國際認同的時侯,强調「對外主權」幾乎成為「現代」中國政治的一個特徵。這套產生在三百多年前的觀念,究竟如何飄洋過海,滲入中華文化及華人社會,以至今天產生如此重大的影響,是本文所關注的要點。 本文計劃以廿世紀初的思潮和政治辯論為主要題材,設法深入瞭解「對外主權」的觀念,在廿世紀中國政治中的形成,立足和發展。並探討,它如何在現代中國政治中,取得如此重要的地位。本文將以「現代」具有中華文化背景政治實體處理對外關係的方式為重點,並不打算以「現代民族主義」的觀點審視,介時希望能提出不同的見解。 為擅明以上過程,必須略述廿世紀初中國的大環境,列強壓境,中國不得不攺變一貫對外政治架構,從宗主國的地位驟然降到倍受强權欺凌的劣勢。當時羣情激憤,對外關係構想層出不窮,包括主權外交、共產國際、投靠列強、甚至無政府主義等。最後,行使的是以「對外主權」為概念的主權外交。 本文將從以下三個角度,研析這個概念在中國的興起。第一,因為無法抗拒當時的國際形勢,被迫接受一個由西方列強擬定,以照顧它們利益為主旨的外交框架。第二,純粹出於提升行政以及經濟效應。第三,知識份子和政治菁英追求「現代化」的結果。 本文希望經過研習和觀察,能進一步理解「對外主權」的概念,和它在以中華文化為背景的政治實體上的地位和影響,並能提出看法及意見。… … …

***

Ja Ian Chong and LAM Peng Er, “Japan-Taiwan Relations: Between Affinity and Reality,” Asian Affairs: An American Review 30.4 (Winter 2004): 249–67. (Note errata on authorship listed in next issue).

This paper examines the ingredients for the affinity between Taiwan and Japan: a shared history, which began when Taiwan became the first colony of Japan; common values; economic ties; strategic alignment; and political and social networks. The authors then examine the limits of this relationship. The paper address the implications of this multifaceted relationship for stability in East Asia. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Testing Alternative Responses to Power Preponderance: A Look at the Asia-Pacific,” Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Working Paper Series 60 (January 2004).

In an earlier piece entitled, “Revisiting Responses to Power Preponderance: Beyond Balancing and Bandwagoning”, the author developed four alternative responses to power preponderance that fell outside the traditional international relations framework of balancing and bandwagoning. The four responses are namely binding, buffering, bonding and beleaguering. The previous work argued that states might broadly adopt these four responses to preponderant power depending on their relative power next to the leading state and the level of integration with the world system.

In this follow-on work, the author tries to test the above conceptual argument against empirical evidence. To do so, this paper looks at five case studies, China, Taiwan, Singapore, North Korea and Australia during the past decade-and-a-half of American unipolarity. This choice of the four East Asian cases aims to vary power and integration while holding potential intervening variables such as culture, geography, and history constant. Australia is a control case as it differs from the four East Asian cases in geography, history, and culture.

This paper finds that non-leading states respond to power preponderance along the intervals of power and integration as predicted by the argument. However, this study also finds that state responses to power preponderance do not fit perfectly within the categories laid out by the argument. States often display some mixture of strategic responses even if they are inclined towards one approach. Nonetheless, such variation in response appears to be unsystematic and fluctuates according to the specific historical contingencies of each case.

Although the paper argues that relative power and integration play an important role in shaping responses to power preponderance, it leaves open the possibility that prior state choices, particularly on normative issues, can affect power and integration. The paper concludes by suggesting that the collective and cumulative effects of alternative responses to power preponderance may affect the persistence of unipolarity. As such, the paper also calls for further study into the reactions of lesser powers to preponderant power. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Revisiting Responses to Power Preponderance: Beyond the Balancing-Bandwagoning Dichotomy,” Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Working Paper Series 54 (November 2003).

Since the 1990s, there has been a growing body of literature in international relations that looks at the unipolar world order that emerged from the ashes of the Cold War. Most of these works, however, tend to focus on describing the characteristics of this unipolar world or predicting its longevity. This working paper contends that such approaches do not pay adequate attention to how non-leading states in the international system are attempting to respond to American primacy of power in this age of unipolarity. The author argues that conventional conceptions of international politics that frame state reactions to superior power within the bounds of balancing and bandwagoning are inadequate to understand how state actors are trying to advance and preserve interests in relation to preponderant American power.

As such, this paper tries to argue that states try to forward and defend interests in relation to the system leader based on power relative to the pre-eminent state and integration in the world system. Power, on one hand, defines the capability of second-tier states to act, while integration, on the other, helps determine the incentives and costs of different actions. On the basis of relative power and integration, the paper identifies four possible alternative conceptualisations of alternative strategies to balancing and bandwagoning—buffering, bonding, binding, and beleaguering. It goes on to suggest that the tendency of states to pursue these various approaches to advancing and defending interests may have an impact on the nature and even duration of the current unipolar order.

Although this paper takes seriously the structural perspective in considering responses to dealing with the problem created by highly asymmetric power realities that lie beyond the balancing-bandwagoning dichotomy, it does not rule out the possibility that other factors may also affect state action. It accepts that a states power and level of integration are highly dependent on prior decisions within the polity that may rest on ideational and contingent material realities. The argument of this paper also does not rule out the effects of path dependence from previous historical events specific to each state. … … …

UNREFEREED ARTICLES & BOOK CHAPTERS

Ja Ian Chong, Review of Steve Chan, Thucydides Trap? Historical Interpretation, Logic of Inquiry, and the Future of Sino-American Relations (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2020); ISSF Roundtable 12-2, H-Diplo, 9 November 2020.

… … … A main thrust in the volume is the argument that American acceptance of status adjustment is key to avoiding conflict since the PRC does not have revisionist intentions.Rather, it is the United States, especially under the Trump administration, that is unsettling the existing international order and stability with withdrawal from international arms control treaties and voting against the UN General Assembly majority (134-141).I am left wondering why a natural status adjustment will not occur as the United States limits its own institutional participation, allowing the PRC’s relative prominence to grow by default.Additionally, whatever the problems of the Trump administration’s policies, its actions say little about the Xi leadership’s intentions given the opacity of the current Chinese political system.The PRC may have made declarations in support of the international system and joined various international organizations, but Chan does not elaborate on why he believes such steps equate to China committing to the sorts of strategic restraint that are needed to maintain order (122, 134-8).[6] Further explanation can make Chan’s case more persuasive.

Apart from outright lying, actors can have a range of motivations and possibilities for participating in organizations, not all of which conform to the overall interests of the grouping or all its members.Among other things, actors may use participation to frame issues, change agendas, and block decisions.Such effects are particularly pronounced when it comes to powerful actors and applies to the PRC as much as it does to the United States.Indeed, the ongoing U.S.-China tussles over the World Trade Organization, World Health Organization, and World Intellectual Property Organization may indicate the presence of such machinations.Even if there is acceptance of existing arrangements, rules, and international law on Beijing’s part today, Chan admits that there is nothing to stop a change of heart and reneging on China’s part.[7]

Indications exist that the Xi leadership may be less satisfied with the status quo than Chan claims given that current PRC actions push up against not only the United States and Taiwan.South Korea reported economic punishment from China as a result of the deployment of a missile defense system to guard against possible North Korean attacks and repeated dangerous behavior by Chinese fishing vessels.[8] Japan expressed concern over increased naval and aerial activity by PRC assets in and over contested areas.[9] Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam indicate growing PRC harassment of their fishing and other civilian vessels in the South China Sea, which is notable given that Indonesia and the PRC do not have overlapping territorial claims.[10] Then there are tensions along the Sino-Indian border that recently resulted in deadly clashes between Indian and Chinese troops.[11]

Current PRC behavior is worrisome for regional actors in other ways as well.Australia reports economic pressure for not conforming to Beijing’s preferences on pushing for an open investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic and complaining about PRC efforts to influence its internal politics.[12] Along with Canada, Australia saw citizens detained and charged for illegal activities under suspicious circumstances.[13] Singapore too faced Chinese state pressure over its insistence on adherence the rule of law over the arbitration over the South China Sea brought by the Philippines against the PRC.[14] That such issues do not receive more treatment by Chan is curious since they raise questions about PRC’s commitment to self-restraint and can potentially trigger the chain-ganging effects on U.S.-China ties that Chan warns readers about (21-22, 211-215). Such friction can potentially harden positions and raise the stakes over an issue such that prevailing becomes more tied to status and other concerns, driving more aggressive and even revisionist behavior.[15]

Chan’s finding that misplaced worries about the PRC and its intentions stem in part from misunderstandings of perspectives on international politics that are informed by theories from “the West” rather than China deserves elaboration and debate.So-called “Western” international relations theories often have parallels in the Chinese tradition, broadly construed.Work analyzing Spring and Autumn, Warring States, Song, and Ming documents indicate that the strategic thought that is prominent in these periods closely resembles statecraft familiar to those in the contemporary “West.”[16] Texts as varied as the Han-era annals Records of the Grand Historian and the Ming-era fiction Romance of the Three Kingdoms will suggest the same.[17] Parallels between “Western” and “Chinese” approaches to politics are unsurprising. Several millennia of collective human experience, thought, and debate over statecraft, conflict, as well as governance are almost certainly bound to produce similarities in responses.

Dividing the world into “Western” and “Chinese” views of the world ignores the fact the PRC has disagreements with ostensibly “non-Western” polities such as India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, each with their own distinct philosophical traditions.[18] Also, despite sharing cultural origins, people in the PRC and on Taiwan disagree fundamentally issues of political values and rights, not the relatively simple issues of who should rule China or what a Chinese state should entail geographically.[19] Moreover, the PRC’s ruling Chinese Communist Party draws at least some of its inspiration from European thinkers in the form of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.Successive dynasties from historical China also proved themselves very adept at conquest—that is how regimes and empires get built.[20] Attributing tensions between the United States and PRC to culture suggests an overly monolithic view of the rich and varied philosophical and political traditions both major powers draw from, giving them less credit than is due.[21]

To claim that contemporary international scholarship and U.S. policy are unable to adequately understand China because they are “Western” may oversimplify the nature and seriousness of problems dogging U.S.-China relations and their consequences for the world.Relegating difference to culture is not only Orientalizing, it can encourage a misplaced expectation that understanding can bring some sort of happy, mutually acceptable outcome. Perhaps Beijing and Washington understand each other well.They simply disagree fundamentally over values and interests in ways that make finding mutually acceptable accommodation increasingly difficult.This does not have to imply that either side is morally superior or normatively “better” than the other, just that understanding provides little promise for improving relations and avoiding confrontation.Better accounting for such possibilities invites fuller consideration of the roles that agency and contingency play in major power relations, two features that Chan clearly identifies as critical in the volume.

Thucydides’s Trap? deserves much credit for grappling with important, pressing, and difficult questions about the drivers behind the downturn in U.S.-China relations and possible ways to address this slide.Yet, Chan’s outlook is more similar to Graham Allison’s than he initially lets on. Allison’s call for creative statecraft is possible only if the United States and China are not locked in a structural situation which neither can escape or beset by contingent circumstances that prevents Washington and Beijing from effectively exercising the agency Chan believes is central. Chan offers some insight when he points to divergences in perspectives between Washington and Beijing but may be overly limiting the ways he conceives of effects of culture and socialization.Likewise, the volume can go further in conceptualizing the various ways third parties such as regional actors and international organizations can affect U.S.-China ties, given that world politics is not just major powers going at each other—a fact both Chan and Allison recognize. Major power interactions simply do not occur in a vacuum.Such dynamics may reinforce competition as much as ameliorate them, but their effects await further clarification and explanation. … … …

***

Chong Ja Ian, “The Continuing Contest for Singapore’s Future,” The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 24 July 2020.

As the dust settles after the city-state’s 10 July general election, Singaporeans are facing a new parliamentary term that promises to be challenging. Tensions will play out between persistent constitutional constraints and new expectations in the context of a pandemic-ridden world. Voters are anticipating substantive change following the unexpectedly strong showing by alternative political parties. The Workers’ Party (WP) won a record 10 seats, consolidating its position as Singapore’s largest and most important opposition party.

Beneath the excitement remains the fact that the long-dominant People’s Action Party (PAP) retains its parliamentary supermajority and close relationship with key state agencies, such as the People’s Association. This raises questions about how the nation will reconcile a popular desire for greater oversight and more diversity with a political system that remains dominated by a single party.

One theme common among the opposition parties was the need to have a parliament that is more representative of the different voices that make up the country and better able to watch over a PAP administration. The larger and more electorally successful parties—the WP, the Progress Singapore Party (PSP) and the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP)—were particularly clear in articulating this aspiration, emphasising a need to avoid giving the PAP ‘a blank cheque’.

Singaporean voters also seemed to support a more systematically redistributive approach to public policy. The WP, SDP and, to some degree, the PSP all took on positions to the left of the PAP, putting forward proposals for a national minimum wage, redundancy insurance, and support for unpaid caregivers to apply across the board. The PAP, on the other hand, kept to its traditional emphasis on the efforts of individuals and families, with minimalist state support supplemented by one-off transfers.

Acceptance of, even enthusiasm for, more left-leaning proposals suggests that Singaporeans are willing to consider different social and economic policy settings. This shift in popular sentiment is perhaps unsurprising, given the widespread concern about the impacts of a prolonged global economic slowdown in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Another takeaway from this election is Singaporeans’ apparent readiness to have more open discussions about race, discrimination and bullying. Half-way through the election campaign, news broke that one of the WP’s candidates, Raeesah Khan, had posted strongly worded statements about discrimination and supposed special treatment. … … …

***

Chong Ja Ian, “Complications of Ethnicity: The Politics of Chinese-ness in Singapore,” in Diversity and Singapore Ethnic Chinese Communities, in Koh Khee Heong, Ong Chang Woei, Phua Chiew Ping, Chong Ja Ian, Yang Yan, eds. (Singapore: Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre and the Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, 2020), 1–12.

Where I begin my discussion is to ask what people mean when they say they are Chinese or ethnic Chinese. There are multiple layers of meaning that come with that statement. The roots of these meanings are located historically in ideas about what China and Chinese ought to be. If you ask what China is or is not, an easy answer is “Well, China is today People’s Republic of China.” You can probe a little bit more and enquire how places like Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet fit within such a conception of China. Even such a simple line of questioning will quickly uncover the fact that claims about what “China” is or is not faces contestation. We cannot get away from this fact. Ideas about China encounter challenges because they too are historically rooted phenomena that will face challenge from new realities. … … …

***

Wayne Soon and Ja Ian Chong, “What History Teaches About the Coronavirus Emergency,” The Diplomat, 12 February 2020.

Lessons of transparency and transnational cooperation from the 1910-11 Manchurian Plague are still relevant to China and the world today.

Accounts about the disease started sporadically. Somewhere in China people were getting sick in unusual numbers. Then press reports started appearing. Large numbers of people were getting seriously ill along main transport axes. News of deaths soon followed. In a few months 60,000 people would die before the disease came under control. This was not Wuhan in December 2019 and January 2020; it was northeastern China from late 1910 to early 1911. The Manchurian Plague, as the incident came to be known, was the first instance of modern techniques being applied to a public health crisis in China. Lessons of transparency and transnational cooperation from that event more than a century ago are still relevant to China and the world today.

In 1910 and 1911, Manchuria was nominally under Chinese control, but years of foreign incursion saw Japan, Russia, Britain, France, Germany, the United States, and others jostling for power in the region. These foreign actors blamed the Qing government, then running China, for not doing enough to stem the spread of plague. The disease was allegedly transmitted from marmots to humans and later evolved to rapid human-to-human transmission. In response, the Qing court-appointed Wu Lien-teh (伍連德), an ethnically Chinese, Cambridge-trained doctor and public health expert who was born and raised in the British colony of Penang, to fight the plague.

Wu, together with his colleagues in China and abroad, implemented several familiar measures. They came to an early consensus that quarantine and isolation were the best ways to solve the problems and developed a variety of methods, some highly authoritarian, to stem the plague. They insisted on mask-wearing among medical personnel, demanded the cremation of infected bodies, imposed travel restrictions on affected reasons, built up quarantine facilities, and imposed strict home-quarantine. Officials rounded up locals using wagons, holding them until they were no longer symptomatic, disinfected houses that held suspected patients (against their owner’s wills), and forcibly quarantined people in hospitals.

The steps Wu and his colleagues took anticipate action by today’s Chinese government, notably the construction of a special care hospital in 10 days and the use of drones to ensure that residents not leave their homes unnecessarily and without a face mask. Such measures to control the 2019 novel coronavirus (officially known as COVID-19) outbreak suggest an unpleasant level of encroachment on personal rights, with which Wu and his colleagues would likely agree. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “Is Singapore Ready for Malign Foreign Influence?” East Asia Forum, 17 January 2020.

Singaporean politicians and commentators repeatedly emphasise the dangers of malign foreign interference. Attention has moved from a foreign academic being expelled for being an ‘agent of influence’ to civil society activists meeting with foreign leaders and independent media receiving foreign foundation funding. Opinion pieces echo the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) yet-to-be verified claims about external instigation in Hong Kong’s ongoing protests and discuss how Singapore may face similar issues.

Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) is even convening a meeting for academics to discuss foreign influence. These events may lead to legislation on the issue. But Singapore’s approach to the management of undue foreign involvement in local politics can benefit from further discussion, explanation and refinement.

The city-state’s concerns are unsurprising. From Singapore’s perspective, the world seems increasingly tumultuous and uncertain given the possible economic decoupling of the United States and the PRC as well as more muscular foreign policy from both major powers. The island’s past prosperity rested on opportunities arising from the convergence of PRC and US economic and strategic interests. Then there are allegations of outside attempts to distort political processes in nearby Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan and Malaysia as well as in the United Kingdom and the United States. These events are occurring against the backdrop of a leadership transition in Singapore, triggering its already acute sense of vulnerability.

Effective external manipulation of local politics often involves the manipulation of groups and individuals in positions of authority and sensitivity. This enables direct access to legislative processes, policymaking, policy implementation and sensitive information while lowering the risks of detection and the potential for blowback. Efforts to sow social discord typically rely on the exploitation of trusted figures, entities or sources of information to create or exacerbate existing cleavages.

Singapore’s minuscule independent media, feeble civil society and dormant academia simply do not have much social and political capital to be worth the effort to manipulate. They have less influence than chambers of commerce, industry associations and state-affiliated bodies that not only have foreign members but regularly interact with officials over policy matters.

It is unclear whether existing mechanisms can constrain persons in authority should ill-intentioned foreign actors compromise them, despite persistent warnings about threats from China, Malaysia and elsewhere. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, “A Fraught and Frightening Future? Southeast Asia under the Shadow of Trump’s American and Xi’s China,” Asia Dialogue, 14 January 2019.

If the tumult from last November’s APEC Summit in Papua New Guinea is any indication, then Southeast Asia seems set to be buffeted by the playing out of tensions between the US and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Both the Trump administration and Xi Jinping’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP) government appear insistent on their divergent visions, be they strategic, economic, institutional or political.

This new reality places Southeast Asia on the fault line of increasingly opposed American and Chinese interests. Complicating matters is the fact that Southeast Asia is particularly ill-equipped to deal with the challenges and consequences of Sino-American differences and tensions at present. As a result, there is little to contain the growing competitive impulses of the Trump and Xi administrations in Southeast Asia and the negative effects that will follow.

One reason Southeast Asia is likely to become an arena for increased US-China friction comes from the fact that it is an area where an increasingly powerful and dominant China is developing primacy. Not only does the region physically border the PRC, but China’s most efficient trade routes to and from South Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe pass through the Malacca Strait and the South China Sea. Disruption of such traffic will prove economically costly to Beijing, especially if there are impediments to the PRC importing energy.

Moreover, the ability to veto access to the South China Sea can help Beijing to defend its coast better, as far as the so-called ‘First Island Chain’, securing passage to the Pacific Ocean for its ballistic missile submarines. Pre-eminence in Southeast Asia also permits Beijing to put pressure on Taiwan and key American allies such as Japan and South Korea, given the importance of the South China Sea to their economies.

Beijing’s emphasis on investment through Xi Jinping’s signature ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) is a means for the PRC to consolidate its leading position in Southeast Asia. BRI projects build on China’s role as Southeast Asia’s top trading partner by tying key infrastructure development in the region to the PRC, and potentially also opening up participant Southeast Asian countries to Beijing’s political sway through indebtedness.

However, these dynamics can create serious domestic problems for Southeast Asian states. For example, the defeat in 2018 of the long-ruling Barisan Nasional (National Front) coalition in Malaysia and subsequent indictment of former Prime Minister Najib Razak came amid allegations of corruption tied to BRI projects. PRC interference related to BRI investments has also become a cause for concern in Thailand, Myanmar and Indonesia. These developments come on top of Beijing’s continued fortification of the artificial islands which it reclaimed in the South China Sea to bolster territorial claims that appear inconsistent with international law. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, Review of Evelyn Goh, ed., Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017); Journal of Chinese Overseas 14.2 (October 2018): 296–300.

China’s ability to shape policies and actions across Asia and beyond has become an issue of growing interest among policymakers and academics alike. Much of this attention comes from the social and political prominence that accompanied the PRC’s rapid and steady economic growth over the four decades. Evelyn Goh’s edited volume, Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia (Oxford 2017), is a welcome addition to efforts at presenting systematic, theoretically-informed analyses of the way the PRC exercises power. … … …

***

Ja Ian Chong, Review of “The Rise of China and the Overseas Chinese by Leo Suryadinata,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 91 (Part 1) 314 (June 2018): 51–54.

Leo Suryadinata’s The Rise of China and the Chinese Overseas: A Study of Beijing’s Changing Policy in Southeast Asia and Beyond is a very welcome addition to the discussion of ties between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and ethnic Chinese living beyond its borders. Suryadinata makes the case in the book that as the PRC becomes more globally prominent, it is increasingly blurring lines in its treatment of PRC citizens and non-PRC citizen ethnic Chinese overseas. This claim comes amid allegations of growing PRC efforts to mobilize ethnic Chinese communities abroad to serve its national interests, be they economic, political, or strategic.

These concerns are not new and are in fact a throwback to the past. They give the book an added timeliness and importance. For much of the Cold War, ethnic Chinese communities in non-communist parts of Southeast Asia faced the suspicion of being a possible subversive fifth column for the PRC, especially if they seemed left-leaning. Such perspectives diminished as the PRC engaged in economic reform from the late 1970s, eschewed radical revolution, and passed a nationality law in 1980 clearly demarcating non-PRC citizen ethnic Chinese abroad from PRC citizens. Recent reports of PRC efforts to lobby and police opinion in foreign countries using members of local ethnic Chinese communities ranging from Europe and North America to Oceania and Southeast Asia have again brought these long-dormant issues to the fore.1 This is an issue on which Suryadinata has previously written, and he provides readers a brief reminder of these themes in Chapter 3.2

An Awkward Closeness