Competition with China Can Save the Planet: Pressure, Not Partnership, Will Spur Progress on Climate Change

Andrew S. Erickson and Gabriel Collins, “Competition with China Can Save the Planet: Pressure, Not Partnership, Will Spur Progress on Climate Change,” Foreign Affairs 100.3 (May/June 2021): 136–49.

- China’s climate diplomacy stands at a great remove from the country’s coal-hungry industrial reality.

- When it comes to climate change, the United States should compete, not cooperate, with China.

ANDREW S. ERICKSON is Professor of Strategy at the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute and a Visiting Scholar at Harvard University’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.

Despite Chinese President Xi Jinping’s pledge that his country will reach “carbon neutrality” by 2060, “serious decarbonization remains a distant prospect,” argue Andrew S. Erickson and Gabriel Collins in Foreign Affairs. “China remains addicted to coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel. It burns over four billion metric tons per year and accounts for half of the world’s total consumption.”

Furthermore, the authors find the use of coal-fired power plants in China dramatically expanded in 2020, warning that the ongoing investments in coal are evidence that China will remain reliant on it for decades to come.

“When it comes to climate change, the United States should compete, not cooperate, with its rival,” the authors contend. “A cooperation-first approach in which Beijing sets the fundamental terms is doomed to fail. Countries seeking cooperation with China are supplicants and, under a best-case scenario, will be forced to make concessions first, after which Beijing might finally deign to engage.”

Erickson and Collins argue that Xi and Chinese policymakers know that their country is critical to curb greenhouse gas emissions on an international level and use that leverage to advance their interests in other areas—suggesting that “Xi’s bullish talk of combating climate change is a smokescreen for a more calculated agenda.”

“Beijing will likely continue using negotiations on climate issues to shield its domestic human rights record and regional aggression. Worse still, it will probably demand economic, technological, and security compromises from the United States and its allies—such as their agreeing not to challenge China’s coercive activities in the South China Sea.”

The authors recommend that U.S. officials “build a coalition of like-minded partners—largely drawn from the industrialized member states of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—to pressure China into sourcing its energy supplies more sustainably.” This coalition should then seek to implement “carbon taxation—a levy on goods or services corresponding to their carbon footprint, or the emissions required to make them.”

Erickson and Collins explain that “a coordinated system would make carbon-intensive Chinese goods less competitive and reduce the disadvantages that manufacturers in the United States face from coal-fired Chinese competitors. But more important, it would force China to take decarbonization seriously.”

“Negotiating proactively with China cannot curtail climate change; Beijing would impose unacceptable costs while failing to deliver on its end of any bargain,” the authors conclude. “Only a united climate coalition has the potential to bring China to the table for productive negotiations, rather than the extractive ones it currently pursues.”

This article is part of the May/June issue of Foreign Affairs, which will be released in full on April 20, 2021.

Late last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged that his country would reach “carbon neutrality” by 2060, meaning that by that time, it would remove every year from the atmosphere as much carbon dioxide as it emitted. China is currently the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, responsible for nearly 30 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. Targeting net-zero emissions by 2060 is an ambitious goal, meant to signal Beijing’s commitment both to turning its enormous economy away from fossil fuels and to backing broader international efforts to combat climate change.

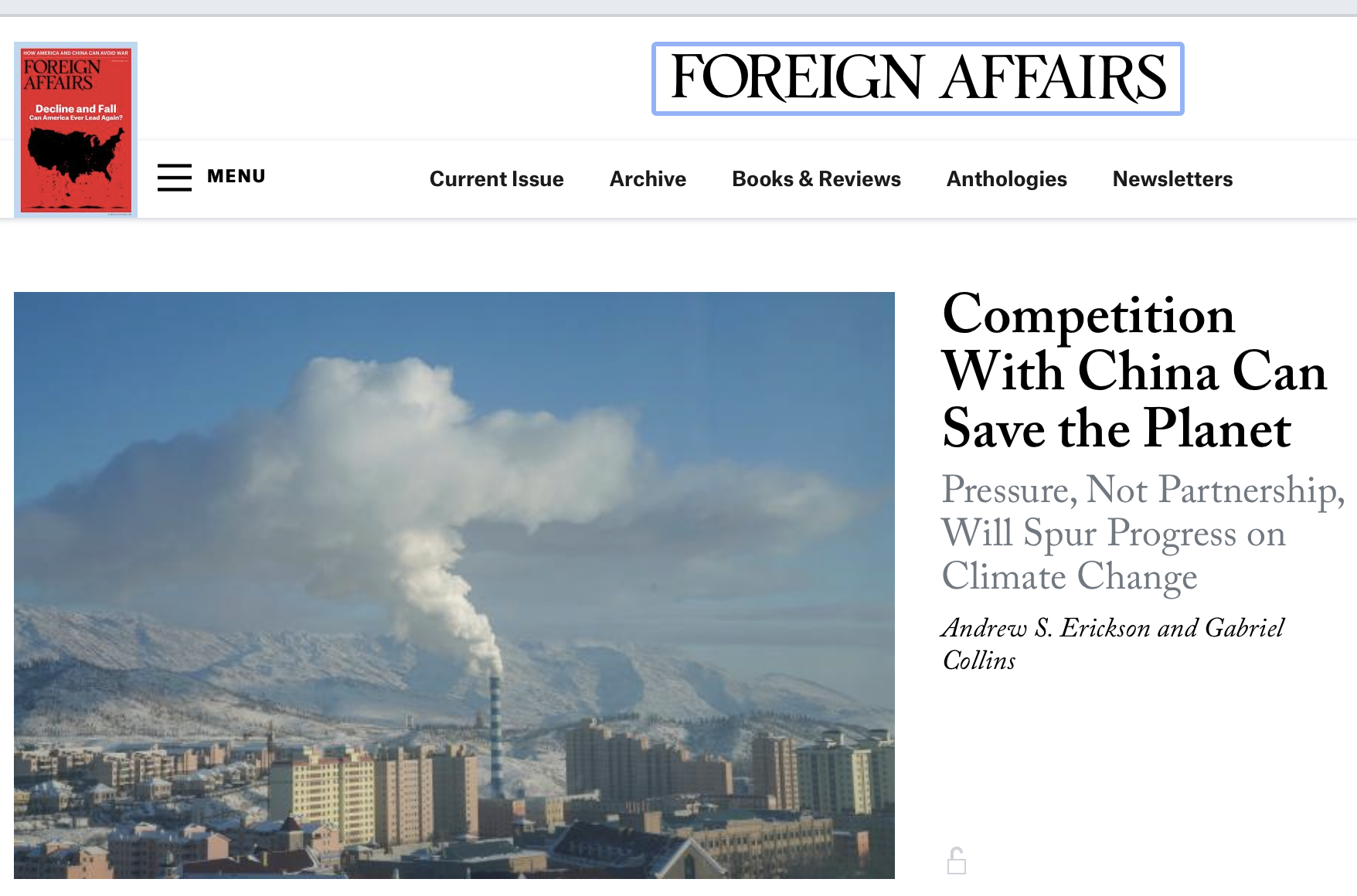

But this rhetorical posturing masks a very different reality: China remains addicted to coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel. It burns over four billion metric tons per year and accounts for half of the world’s total consumption. Roughly 65 percent of China’s electricity supply comes from coal, a proportion far greater than that of the United States (24 percent) or Europe (18 percent). Finnish and U.S. researchers revealed in February that China dramatically expanded its use of coal-fired power plants in 2020. China’s net coal-fired power generation capacity grew by about 30 gigawatts over the course of the year, as opposed to a net decline of 17 gigawatts elsewhere in the world. China also has nearly 200 gigawatts’ worth of coal power projects under construction, approved for construction, or seeking permits, a sum that on its own could power all of Germany—the world’s fourth-largest industrial economy. Given that coal power plants often operate for 40 years or more, these ongoing investments suggest the strong possibility that China will remain reliant on coal for decades to come.

Here’s the inconvenient truth: the social contract that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has forged with the Chinese people—growth and stability in exchange for curtailed liberties and one-party rule—has incentivized overinvestment across the board, including in the coal that powers most of China’s economy. China may be shuttering some coal plants and investing in renewable energy, but serious decarbonization remains a distant prospect.

Xi’s bullish talk of combating climate change is a smokescreen for a more calculated agenda. Chinese policymakers know their country is critical to any comprehensive international effort to curb greenhouse gas emissions, and they are trying to use that leverage to advance Chinese interests in other areas. Policymakers in the United States have hoped to compartmentalize climate change as a challenge on which Beijing and Washington can meaningfully cooperate, even as the two countries compete elsewhere. John Kerry, the United States’ senior climate diplomat, has insisted that climate change is a “standalone issue” in U.S.-Chinese relations. Yet Beijing does not see it that way.

After U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken declared in late January that Washington intended to “pursue the climate agenda” with China while simultaneously putting pressure on Beijing regarding human rights and other contentious policy issues, Zhao Lijian, the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s spokesperson, warned the Biden admin- istration that cooperation on climate change “is closely linked with bilateral relations as a whole.” In other words, China will not compartmentalize climate cooperation; its participation in efforts to slow global warming will be contingent on the positions and actions that its foreign interlocutors take in other areas.

Zhao’s conspicuously sharp-tongued riposte is already inducing key U.S. partners to pull their punches in climate interactions with China. For instance, in a February video call with Han Zheng, China’s top vice premier, Frans Timmermans, the executive vice president of the European Commission and the EU’s “Green Deal chief,” reportedly steered clear of discussing human rights and the EU’s plans for a carbon border tax, issues China finds contentious. Beijing will likely continue using negotiations on climate issues to shield its domestic human rights record and regional aggression. Worse still, it will probably demand economic, technological, and security compromises from the United States and its allies—such as their agreeing not to challenge China’s coercive activities in the South China Sea—for which those countries would receive little, if anything, in return.

As a result, U.S. officials seem to face a stark choice. If they make concessions to win China’s cooperation in tackling climate change, Beijing will offer only those climate promises that it would outright fail to fulfill, find itself unable to fulfill amid opposition from powerful domestic interests, or, less likely, fulfill merely by default if its economic growth slows more rapidly than widely expected. But if they refuse to deal with China, they may imperil efforts to slow global warming. There is another option, however. When it comes to climate change, the United States should compete, not cooperate, with its rival. … … …