Key China Content from New NIC Report: “Global Trends 2040: A More Contested World”

Global Trends 2040: A More Contested World (Office of the Director of National Intelligence: National Intelligence Council, March 2021).

KEY CHINA-RELATED CONTENT (Hypothetical scenarios excluded because their details are notional):

I. MAIN REPORT

p. 7

“Asian economies appear poised to continue decades of growth, at least through 2030, and are looking to use their economic and population size to influence international institutions and rules.”

p. 16

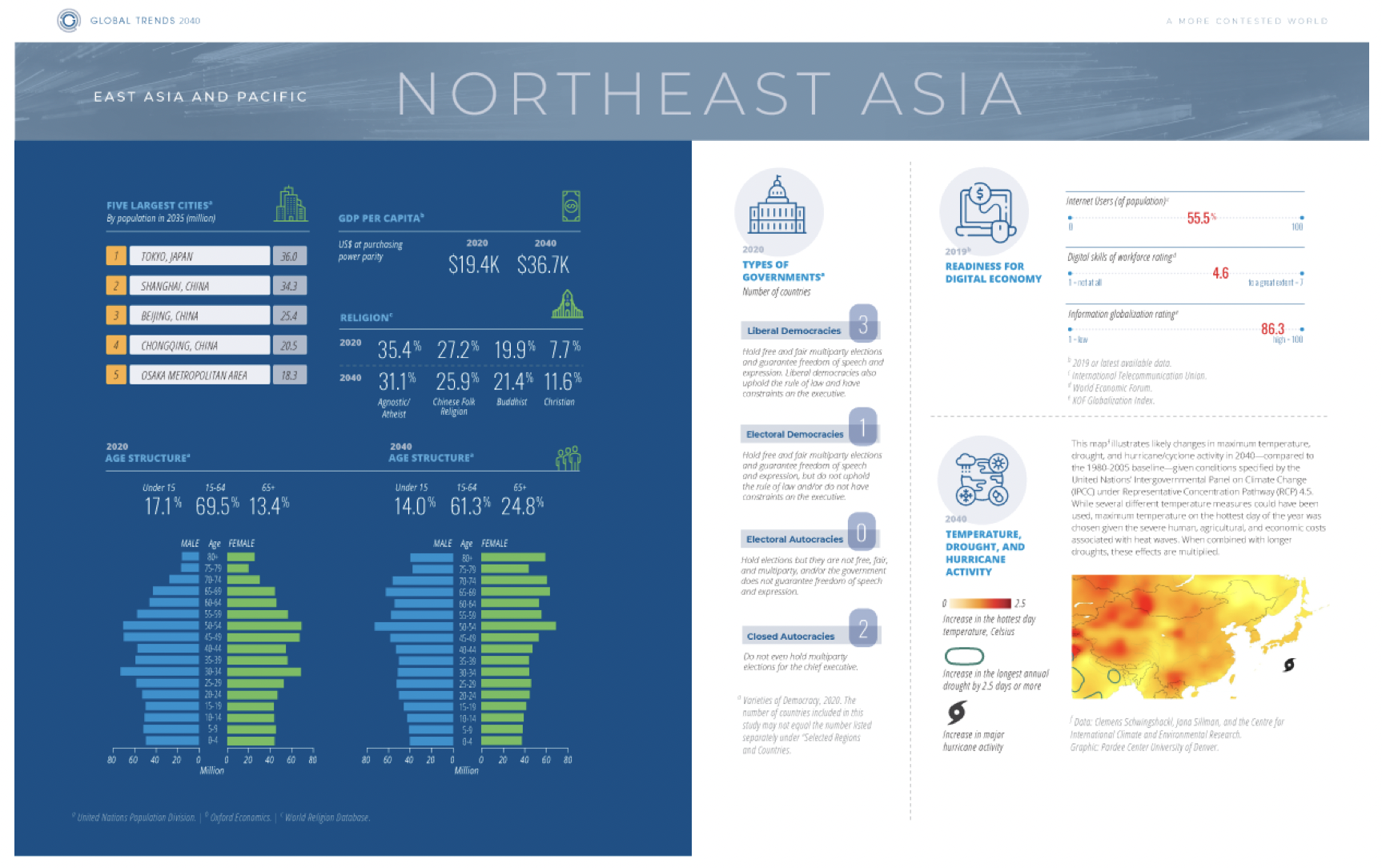

“rapidly aging and contracting populations in some developed economies and China will weigh on economic growth.”

p. 18

“Although India’s population growth is slowing, it will still overtake China as the world’s most populous country around 2027.”

p. 29

“The greatest variable is likely to be how China handles the demographic crunch it will see during the next two decades—the deep decline in fertility from its one-child policy has already halted the growth of its labor force and will saddle it with a doubling of its population over 65 during the next two decades to nearly 350 million, the largest by far of any country. Even if the Chinese workforce is able to rise closer to advanced-economy productivity levels through improved training and automation, China remains in danger of hitting a middle-income trap by the 2030s, which may challenge domestic stability.”

p. 40

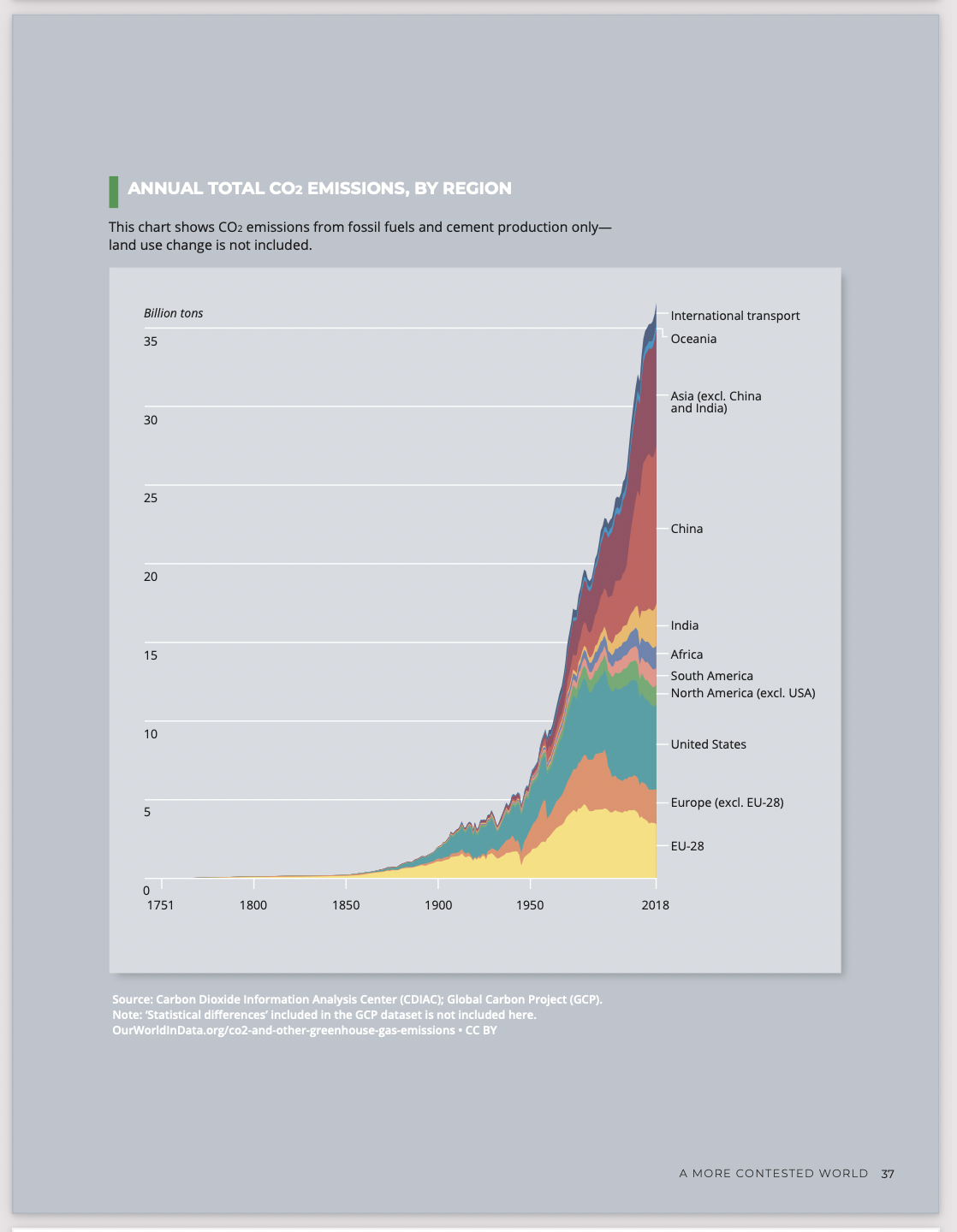

“China is trying to boost its international image by claiming to be a leader on climate diplomacy despite its growing emissions—already the highest in the world.”

p. 54

“The race for technological dominance is inextricably intertwined with evolving geopolitics and is increasingly shaped by broader political, economic, and societal rivalries, particularly those associated with China’s rise. Amassing the resources to sustain broad technology leadership, including the concentration of human talent, foundational knowledge, and supply chains, requires decades of long-term investment and visionary leadership. Those focusing their resources today are likely to be the technology leaders of 2040. In open economies, a mix of private efforts and partnerships between governments, private corporations, and research programs will compete with state-led economies, which may have an advantage in directing and concentrating resources, including data access, but may lack the benefits of more open, creative, and competitive environments.”

p. 62

“The efforts of both government and commercial actors will establish new domains of space competition, particularly between the United States and China.”

“CHINA AS A SPACE POWER. By 2040, China will be the most significant rival to the United States in space, competing on commercial, civil, and military fronts. China will continue to pursue a path of space technology development independent of that involving the United States and Europe and will have its own set of foreign partners participating in Chinese-led space activities. Chinese space services, such as the Beidou satellite navigation system, will be in use around the world as an alternative to Western options.”

p. 67

“During the next two decades, power in the international system will evolve to include a broader set of sources and features with expanding technological, network, and information power complementing more traditional military and economic power. The rivalry between the United States and China is likely to set the broad parameters for the geopolitical environment during the coming decades, forcing starker choices on other actors. States will leverage these diverse sources of power to jockey over global norms, rules, and institutions, with regional powers and nonstate actors exerting more influence within individual regions and leading on issues left unattended by the major powers. The increased competition over international rules and norms, together with untested technological military advancements, is likely to undermine global multilateralism, broaden the mismatch between transnational challenges and institutional arrangements to tackle them, and increase the risk of conflict.”

p. 76

“Chinese leaders have tapped widespread, often xenophobic nationalism to build support for policies, such as an aggressive Chinese posture in territorial disputes.”

“China’s middle class, defined as those earning between $10 and $110 per day, has grown rapidly from 3.1 percent of the population in 2000 to 52.1 percent in 2018—equivalent to approximately 686 million people who are better positioned to make demands on their government.”

p. 81

“In China, the central tension is whether the Chinese Communist Party can maintain control by delivering a growing economy, public health, and safety, while repressing dissent. The massive middle class in China is largely quiescent now; an economic slowdown could change this.”

“Externally, China, Russia and other actors, in varying ways, are undermining democracies and supporting illiberal regimes. This support includes sharing technology and expertise for digital repression. In particular, some foreign actors are attempting to undermine public trust in elections, threatening the viability of democratic systems. Both internal and external actors are increasingly manipulating digital information and spreading disinformation to shape public views and achieve political objectives.”

p. 85

“Over the long term, the advance or retreat of democracy will depend in part on the relative power balance among major powers. Geopolitical competition, including efforts to influence or support political outcomes in other countries, relative success in delivering economic growth and public goods, and the extent of ideological contest between the Western democratic model and China’s techno-authoritarian system, will shape democratic trends around the world.”

“Although authoritarian regimes in countries from China to the Middle East have demonstrated staying power, they have significant structural weaknesses, including widespread corruption, overreliance on commodities, and highly personalist leadership.”

“Today the most common form of authoritarian regime is personalist—rising from 23 percent of dictatorships in 1988 to 40 percent in 2016—and other regimes, including in China and Saudi Arabia, are moving in that direction.”

p. 90

“During the next two decades, power in the international system will evolve to include a broader set of sources and features with expanding technological, network, and information power complementing more traditional military, economic, and cultural soft power. No single state is likely to be positioned to dominate across all regions or domains, opening the door for a broader range of actors to advance their interests.”

“The United States and China will have the greatest influence on global dynamics, supporting competing visions of the international system and governance that reflect their core interests and ideologies. This rivalry will affect most domains, straining and in some cases reshaping existing alliances, international organizations, and the norms and rules that have underpinned the international order.”

“In this more competitive global environment, the risk of interstate conflict is likely to rise because of advances in technology and an expanding range of targets, new frontiers for conflict and a greater variety of actors, more difficult deterrence, and a weakening or a lack of treaties and norms on acceptable use.”

p. 92

“During the next two decades, the intensity of competition for global influence is likely to reach its highest level since the Cold War. No single state is likely to be positioned to dominate across all regions or domains, and a broader range of actors will compete to advance their ideologies, goals, and interests. Expanding technological, network, and information power will complement more traditional military, economic, and soft power aspects in the international system. These power elements, which will be more accessible to a broader range of actors, are likely to be concentrated among leaders that develop these technologies.”

pp. 92–93

“During the next 20 years, sources of power in the international system are likely to expand and redistribute. Material power, measured by the size of a nation’s economy, military, and population, and its technological development level, will provide the necessary foundation for exercising power, but will be insufficient for securing and maintaining favorable outcomes. In an even more hyperconnected world, power will include applying technology, human capital, information, and network position to modify and shape the behavior of other actors, including states, corporations, and populations. The attractiveness of a country’s entertainment, sports, tourism, and educational institutions will also remain important drivers of its influence. As global challenges such as extreme weather events and humanitarian crises intensify, building domestic resiliency to shocks and systemic changes will become a more important element of national power, as will a state’s ability and willingness to help other countries. In coming years, the countries and nonstate actors that are best able to harness and integrate material capabilities with relationships, network centrality, and resiliency will have the most meaningful and sustainable influence globally.”

pp. 93–94

“Control of key sites of exchange, including telecommunications, finance, data flows, and manufacturing supply chains, will give countries and corporations the ability to gain valuable information, deny access to rivals, and even coerce behavior. Many of these networks, which are disproportionately concentrated in the United States, Europe, and China, have become entrenched over decades and probably will be difficult to reconfigure. If China’s technology companies become co-dominant with US or European counterparts in some regions or dominate global 5G telecommunications networks, for example, Beijing could exploit its privileged position to access communications or control data flows. Exercising this form of power coercively, however, risks triggering a backlash from other countries and could diminish the effectiveness over time.”

p. 94

“From public diplomacy and media to more covert influence operations, information technologies will give governments and other actors unprecedented abilities to reach directly to foreign publics and elites to influence opinions and policies. China and Russia probably will try to continue targeting domestic audiences in the United States and Europe, promoting narratives about Western decline and overreach.”

“The growing contest between China and the United States and its close allies is likely to have the broadest and deepest impact on global dynamics, including global trade and information flows, the pace and direction of technological change, the likelihood and outcome of interstate conflicts, and environmental sustainability. Even under the most modest estimates, Beijing is poised to continue to make military, economic, and technological advancements that shift the geopolitical balance, particularly in Asia.”

China Reclaiming Global Power Role

“In the next two decades, China almost certainly will look to assert dominance in Asia and greater influence globally, while trying to avoid what it views as excessive liabilities in strategically marginal regions. In Asia, China expects deference from neighbors on trade, resource exploitation, and territorial disputes. China is likely to field military capabilities that put US and allied forces in the region at heightened risk and to press US allies and partners to restrict US basing access. Beijing probably will tout the benefits of engagement while warning of severe consequences of defiance. China’s leaders almost certainly expect Taiwan to move closer to reunification by 2040, possibly through sustained and intensive coercion.”

p. 95

“China will work to solidify its own physical infrastructure networks, software platforms, and trade rules, sharpening the global lines of techno-economic competition and potentially creating more balkanized systems in some regions. China is likely to use its infrastructure and technology-led development programs to tie countries closer and ensure elites align with its interests. China probably will continue to seek to strengthen economic integration with partners in the Middle East and Indian Ocean region, expand its economic penetration in Central Asia and the Arctic, and work to prevent countervailing coalitions from emerging. China is looking to expand exports of sophisticated domestic surveillance technologies to shore up friendly governments and create commercial and data-generating opportunities as well as leverage with client regimes. China is likely to use its technological advancements to field a formidable military in East Asia and other regions but prefers tailored deployments—mostly in the form of naval bases—rather than large troop deployments. At the same time, Beijing probably will seek to retain some important linkages to US and Western-led networks, especially in areas of greater interdependence such as finance and manufacturing.”

“China is likely to play a greater role in leading responses to confronting global challenges commensurate with its increasing power and influence, but Beijing will also expect to have a greater say in prioritizing and shaping those responses in line with its interests. China probably will look to other countries to offset the costs of tackling transnational challenges in part because Beijing faces growing domestic problems that will compete for attention and resources. Potential financial crises, a rapidly aging workforce, slowing productivity growth, environmental pressures, and rising labor costs could challenge the Chinese Communist Party and undercut its ability to achieve its goals. China’s aggressive diplomacy and human rights violations, including suppression of Muslim and Christian communities, could limit its influence, particularly its soft power.”

p. 96

“India’s population size—projected to become the largest in the world by 2027—geography, strategic arsenal, and economic and technological potential position it as a potential global power, but it remains to be seen whether New Delhi will achieve domestic development goals to allow it to project influence beyond South Asia. As China and the United States compete, India is likely to try to carve out a more independent role. However, India may struggle to balance its long-term commitment to strategic autonomy from Western powers with the need to embed itself more deeply into multilateral security architectures to counter a rising China. India faces serious governance, societal, environmental, and defense challenges that constrain how much it can invest in the military and diplomatic capabilities needed for a more assertive global foreign policy.”

p. 97

“The influence of nonstate actors will vary and be subject to government intervention. China, the EU, and others are already moving to regulate or break up superstar firms, while Beijing is trying to control or suppress NGOs and religious organizations. Many nonstate actors are likely to try to push back on state efforts to consolidate sovereignty in newer frontiers, including cyberspace and space.”

“Countries, including China and Russia, are likely to apply technological innovations to make their information campaigns more agile, difficult to detect, and harder to combat, as they work to gain greater control over media content and means of dissemination.”

p. 98

CONTESTED AND TRANSFORMING INTERNATIONAL ORDER

“As global power continues to shift, many of the relationships, institutions, and norms that have largely governed and guided behavior across issues since the end of the Cold War are likely to face increasing challenges. Competition in these areas has been on the rise for years with China, Russia, and other countries demanding a greater say.Disagreements are likely to intensify over the mission and conduct of these institutions and alliances, raising uncertainty about how well equipped they will be to respond to traditional and emerging issues. Over time, states may even abandon some aspects of this international order.”

“Rising and revisionist powers, led by China and Russia, are seeking to reshape the international order to be more reflective of their interests and tolerant of their governing systems. China and Russia continue to advocate for an order devoid of Western-origin norms that allows them to act with impunity at home and in their perceived spheres of influence. They are advocating for alternative visions of the role of the state and human rights and are seeking to roll back Western influence, but their alternative models differ significantly from each other. Russia is promoting traditional values and desires a Russian-dominated protectorate covering much of Eurasia. China seeks growing global acceptance of its current social system—namely the Chinese Communist Party’s monopoly on power and control over society—socialist market economy, and preferential trading system.”

Increasing Ideological Competition

“The multidimensional rivalry with its contrasting governing systems has the potential to add ideological dimensions to the power struggle. Although the evolving geopolitical competition is unlikely to exhibit the same ideological intensity as the Cold War, China’s leadership already perceives it is engaged in a long-term ideological struggle with the United States. Ideological contests most often play out in international organizations, standard-setting forums, regional development initiatives, and public diplomacy narratives.”

“Western democratic governments probably will contend with more assertive challenges to the Western-led political order from China and Russia. Neither has felt secure in an international order designed for and dominated by democratic powers, and they have promoted a sovereignty-based international order that protects their absolute authority within their borders and geographic areas of influence. China and Russia view the ideas and ideology space as opportunities to shape the competition without the need to use military force. Russia aims to engender cynicism among foreign audiences, diminish trust in institutions, promote conspiracy theories, and drive wedges in societies. As countries and nonstate actors jockey for ideological and narrative supremacy, control over digital communications platforms and other vehicles for dissemination of information will become more critical.”

p. 98

“actions by China, Russia, and others may present starker choices over political, economic, and security priorities and relationships.”

p. 99

“if China and Russia continue to ratchet up pressure, their actions may resolidify or spawn new security relationships among democratic and like-minded allies, enabling them to put aside differences.”

“China and Russia probably will continue to shun formal alliances with each other and most other countries in favor of transactional relationships that allow them to exert influence and selectively employ economic and military coercion while avoiding mutual security entanglements. China and Russia are likely to remain strongly aligned as long as Xi and Putin remain in power, but disagreements over the Arctic and parts of Central Asia may increase friction as power disparities widen in coming years.”

“The future focus and effectiveness of established international organizations depend on the political will of members to reform and resource the institutions and on the extent to which established powers accommodate rising powers, particularly China and India.”

pp. 99–100

“Western leadership of the intergovernmental organizations may further decline as China and Russia obstruct Western-led initiatives and press their own goals. China is working to re-mold existing international institutions to reflect its development and digital governance goals and mitigate criticism on human rights and infrastructure lending while simultaneously building its own alternative arrangements to push development, infrastructure finance, and regional integration, including the Belt and Road Initiative, New Development Bank, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.”

p. 100

“Long dominated by the United States and its allies, China is now moving aggressively to play a bigger role in establishing standards on technologies that are likely to define the next decade and beyond. For example, international standard-setting bodies will play critical roles in determining future ethical standards in biotechnology research and applications, the interface standards for global communication, and the standards for intellectual property control.”

“authoritarian powers, led by China and Russia, have gained traction as they continue to emphasize their values and push back on norms they view as Western-centric—particularly those that gained currency after the end of the Cold War, such as exceptions that allow for interfering in the internal affairs of member states to defend human rights.”

“During the next 20 years, this competition probably will make it harder to maintain commitment to many established norms and to develop new ones to govern behavior in new domains, including cyber, space, sea beds, and the Arctic.”

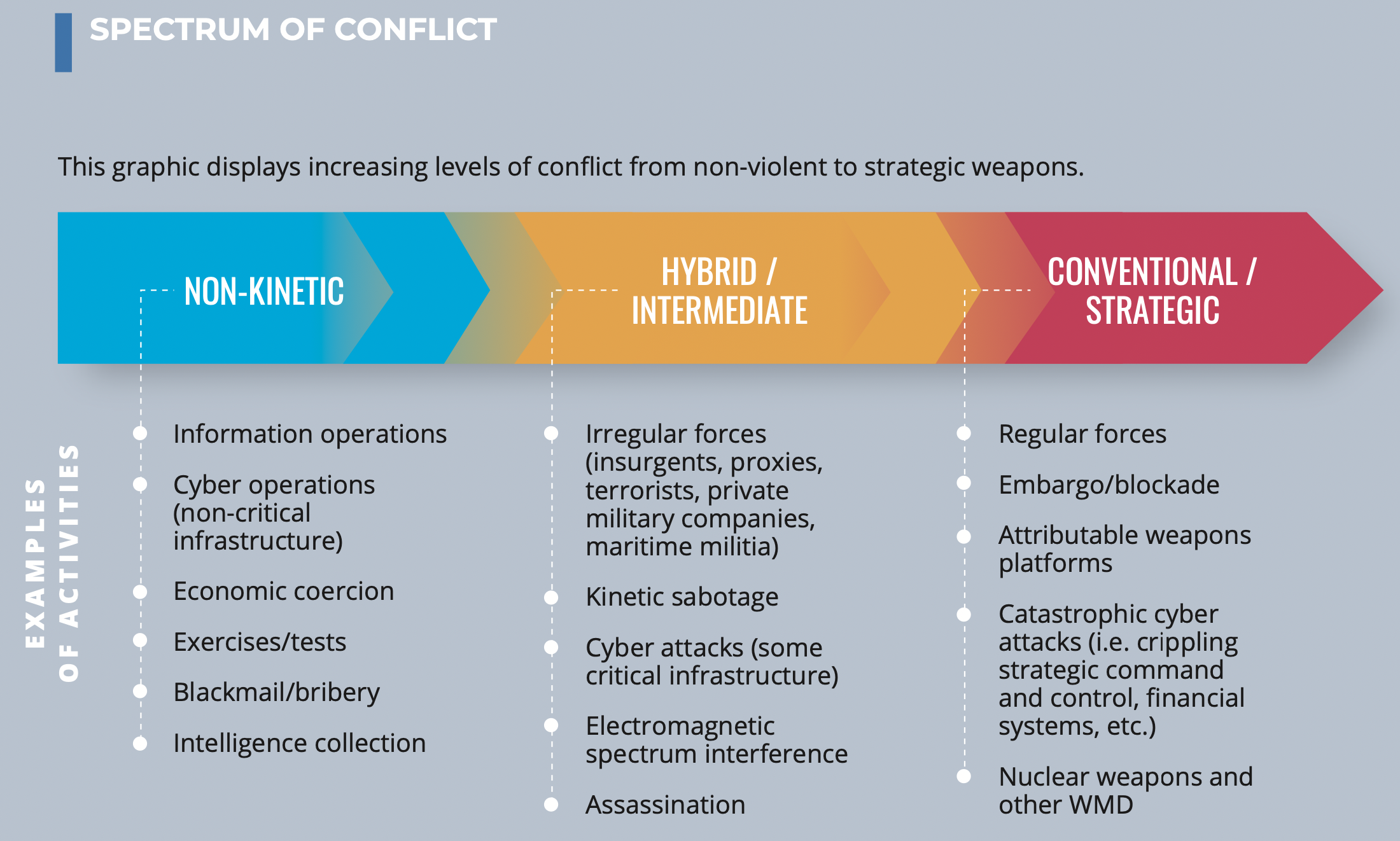

p. 104 [Situating Maritime Militia in Spectrum of Conflict]

p. 106

“China and Russia are investing in new delivery vehicles including missiles, submarines, bombers, and hypersonic weapons. These states are likely to continue to field increasingly accurate, lower yield nuclear weapons on platforms intended for battlefield use, which could encourage states to consider nuclear use in more instances with doctrines that differentiate between large-scale nuclear exchanges and “limited use” scenarios.”

p. 107

“Shifting international power dynamics—in particular, the rise of China and major power competition—are likely to challenge US-led counterterrorism efforts and may make it increasingly difficult to forge bilateral partnerships or multilateral cooperation on traveler data collection and information-sharing efforts that are key to preventing terrorists from crossing borders and entering new conflict zones.”

II. FIVE-YEAR REGIONAL OUTLOOKS

“As the pandemic has demonstrated, it is often a country or region’s less tangible characteristics—such as history, leadership, innovation, and social trust—that combine with tangible features such as wealth, military power, and infrastructure to determine its ability to adapt to structural changes or shocks to the system.”

“European countries increasingly recognize the threat that China’s rise and global ambitions pose to their values, domestic security, and economic future, but they will struggle to protect themselves given their hope for increased access to the Chinese domestic market, interest in future opportunities for technological cooperation, and, in some cases, a pressing need for foreign investment. The EU and its member states may take some steps to diversify supply chains in strategic areas, limit Chinese access to technology, and protect European firms from foreign takeovers, but their economic relationship with China probably will not change in fundamental ways.”

“Both Russia and China are likely to look for opportunities in the region, but their influence will be tempered by complex local histories and the many ethnic and sectarian rivalries. Amid widespread perceptions that the United States is pulling back, many MENA states are seeking to diversify their partnerships to increase their flexibility to address security, technology, and economic challenges. China and Russia are looking to take advantage of vacuums and disarray, but generally stop short of security guarantees.”

Continued Cooperation With China

“China will loom ever larger in Russia’s thinking as its most useful, powerful, and at times, worrisome partner. China’s insistence on a muscular sphere of influence will validate Russia’s own claims to a new world order, and vice-versa. The closeness of Russia’s relationship with China will be driven to a great degree by the two countries’ shared perception of the United States as a mutual competitor, if not adversary, and it probably will be boosted by the personal relationship between Putin and President Xi Jinping. At the same time, China’s global influence and centrality to the world’s economy, Russia’s reliance on China for 5G and other technology, and the continuing dependence of the Russian economy on energy exports, increasingly to China, may keep many Russian officials awake at night. In part to hedge against growing Chinese power, Russia probably will seek to shore up its own influence with regional powers, such as India, Japan, South Korea, and Turkey, and try to renew ties with Europe, especially France and Germany.”

“Growing Military, Technological, and Economic Cooperation: Since 2018, Russia and China have stepped up joint military exercises, and Russia remains China’s largest supplier of arms. The two countries are increasingly cooperating in research and development efforts. In late 2019, Russia and China established a technology investment fund to advance joint development of strategic technologies, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and 5G wireless. Russia probably will remain one of China’s largest suppliers of crude oil and increasingly look to sell natural gas to China as Europe’s demand for Russian gas declines.”

“Managing Relationship Tensions: China’s growing economic clout and encroachment on areas that Moscow sees as within its claimed sphere of influence, partially in Central Asia and the Arctic, could complicate the relationship. Russia has remained outside China’s economic Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), preferring to link its own Eurasian Economic Union to BRI and maintain a semblance of parity in its relationship with Beijing. Russia has viewed China’s expansion of influence as far less threatening than that of the West, but this perception could shift if personal relations between the two leaders cooled or either country came to view the United States as less threatening.”

“Moscow’s drive for predominance in the region probably will challenge freedom of access and exacerbate tensions with regional partners, including other Arctic Council members and China, which considers itself a “near-Arctic” state.”

“Eurasian states will continue to define their geostrategic direction in relation to Russia and, increasingly, to China. They are attempting to reinforce their autonomy and independence, balancing among Russia, China, and the West.”

“Belarusian leaders—whether or not President Lukashenka stays in power—will seek to balance their country’s dependence on Russia against Western and possibly Chinese support to ensure they retain their own power and sovereignty.”

“The Central Asian states of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan will continue to be at the center of competition between Russia and China, but the premium those two powers place on getting along may lead them to compartmentalize if not resolve any differences involving the region.

China’s expanding economic influence faces public unease in Central Asia and may compel regional governments to seek counterweights to Beijing. Moscow is well positioned to play this role and retain influence….”

“Many of the countries in the region—excluding India and Bhutan—will continue to look to China to finance development projects, judging from the scale of existing projects and loans.”

“The balancing approach, particularly in relation to China, also affects regional dynamics. Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka probably judge their countries can more easily deflect New Delhi’s demands or block its regional leadership aspirations by maintaining ties with Beijing. For its part, New Delhi probably will look for ways to mitigate Chinese influence given China’s expanding foothold in the Indian Ocean. For example, India almost certainly will continue to encourage Japan to offer economic investment and some military cooperation to other South Asian countries to push them to align more closely with New Delhi and Tokyo.”

“India and China may slip into a conflict that neither government intends, especially if military forces escalate a conflict quickly to challenge each other on a critical part of the contested border. In June 2020, a short military exchange that resulted in the deaths of at least 20 Indian soldiers exacerbated the strategic rivalry between Beijing and New Delhi and sharply affected international perceptions of both countries.”

The Appeal of Chinese Economic Engagement

“China is likely to remain the biggest source of development funding in South Asia, but it is less clear whether it will maintain its lead to the same extent. Factors affecting China’s lead include the extent of funding available from other sources such as Japan, the Gulf states, and the West; the level of scrutiny applied to governments when approving non-transparent loans from China; the publicly available information about the potential benefits and risks of major projects; and China’s willingness to prioritize investment in South Asia on the scale of the past 5-10 years.”

“The trajectory for East Asia to 2025 increasingly appears to be one in which China expands its leading position in the region, with the majority of its neighbors accommodating Chinese predominance. This accommodation derives largely from their need for economic ties to China and a lack of alternatives, although many countries would prefer to avoid deference to Beijing. By 2025, China’s ambitions and military capabilities are likely to extend further into the Pacific, and its institutional reach will be even broader, having already expanded via organizations such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Lancang Mekong Cooperation forum.”

“During this period, non-traditional security issues, including sea level rise and extreme weather, are likely to become more prominent across the region. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has increased uncertainty, most countries in the region appear to have weathered the pandemic better than the rest of the globe. Barring a major resurgence of COVID-19, East Asia and Pacific nations are likely to be better positioned economically and politically than the West in the post-pandemic era”

“With some of the highest median ages in the region and fertility rates well below replacement, China, Japan, and South Korea are expected to see significant drops in their working-age populations in the next several decades as well as rising social security burdens. Conversely, many Southeast Asian populations are young and well above replacement fertility rates. Indonesia, for example, with a median age of 30, and a fertility rate of 2.3, will be poised to reap a demographic dividend in which its working-age population outnumbers dependents.”

“During the last decade, East Asia has watched China rise against a global backdrop of cracks in the rules-based, Western-led international system. Within this context, East Asia’s middle powers have taken on larger roles to defend democratic rules and norms, push back against perceived Chinese assertiveness, help others build resilience and protect their own sovereignty, and preserve regional stability. Northeast Asian countries’ size and military strength allow them to push back more forcefully than their Southeast Asian neighbors, yet they are increasingly take China’s preferences into account. Australia, Japan, and to a lesser extent New Zealand and South Korea, have deliberately increased their efforts to support free trade, the rule of law, and democratic norms, and provide the region with economic alternatives to Chinese funding.”

“Regional responses to more prominent middle power leadership have been largely welcoming, in part because many countries in the region are wary of growing tensions between great powers and overreliance on either China or the United States. These middle powers are generally seen as trusted partners. In a poll in 2020, Southeast Asian policy elites ranked Japan as the “most trusted” global power, with 61.2 percent of the respondents expressing confidence in Japan to provide global public goods. In the next five years, there probably will be even more calls for middle powers to play this active role, although their ability to meet regional demand for assistance is likely to be constrained by their own economic and strategic circumstances vis-a-vis China.”

“This growing regional emphasis on multilateralism could have the unintended consequence of pulling East Asia more tightly together even as regional states become increasingly wary of growing Chinese power. A greater sense of East Asian regionalism could by chance or design exclude the United States from some regional activities, despite many regional states’ continuing interest in the United States playing a stabilizing role.”

“drought conditions along the Mekong River in mainland Southeast Asia are caused by gradually shifting climate effects, as well as construction of multiple dams in the Chinese section of the river, which has limited the water’s flow, and in February 2020 caused unprecedented drought conditions.”

“South China Sea. In May 2020, China announced a temporary fishing prohibition in waters it has claimed above the 12th parallel, including waters also claimed by the Philippines and Vietnam, as a move to conserve fisheries. Philippines fisheries bureau statistics indicated that the average daily haul for Filipino fishermen had fallen from about 20 kilograms (kg) in the 1970s to less than 5 kg today.”

“Concerns about China’s increasing presence and influence throughout the region have prompted regional democracies to defend democratic rules and norms through both multilateral engagement and bilateral development assistance programs in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands, a trend that probably will continue and perhaps accelerate in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

KEY UNCERTAINTIES

“China will be the common denominator for most regional tension in the next five years as it navigates great power politics and its interest in establishing regional dominance over its neighbors. The manifestation of these tensions is likely to reflect the interconnected nature of East Asia, as Chinese actions in one area—such as the Mekong River—may lead to responses by other countries elsewhere—such as the South China Sea. Tensions may also spiral upward from the local to the international level, such as when Vietnamese or Filipino fishermen confront Chinese Coast Guard vessels and then appeal to their own governments for support from their national coast guards or navies. Each of the areas highlighted in this section could serve as the locus for conflict in the next five years, but it is hard to pinpoint exactly where or when conflict might break out.”

Taiwan

“We assess a high likelihood that cross-Strait tensions will have increased in the next five years. Taiwan’s President, Tsai Ing-wen was re-elected in January 2020 after vowing to protect Taiwan’s sovereignty, and in August 2020, her government announced it would increase Taiwan’s defense budget by 10 percent following a 5 percent increase the year before. In addition, China’s actions to undercut Hong Kong’s autonomy and suppress dissent have increased public support for a distinct Taiwan identity and cemented longstanding concerns that China may take similarly hardline steps toward forcing unification with Taiwan.”

South China Sea

“Disputes in the South China Sea are likely to evolve but not lessen during the next five years if larger powers are increasingly called upon to support the sovereignty claims and commercial interests of smaller claimant states Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Although these states appeared to be increasingly capitulating to China’s desired outcomes pre-pandemic, many in the region responded negatively to Chinese actions in spring and summer 2020, which were perceived as efforts by Beijing to exploit the COVID-19 crisis to consolidate its position. Resource constraints, particularly for fish and energy, are likely to sharpen during the next five years and raise tensions among smaller states, even if they do not feel empowered to push back against Beijing.”

East China Sea

“The waters around the Senkakus—a grouping of disputed islands in the East China Sea administered by Japan—have long been a source of strain between China and Japan, particularly after the Japanese Government bought the islands from a Japanese family in 2012. The presence of Chinese and Japanese fishing and coast guard vessels increases during annual fishing seasons, raising the risk of conflict. The already tense dynamic could be further aggravated by a change in number or type of vessels in and around the territorial waters off the islands. Japan has recently asserted an “unprecedented” increase in the number of Chinese incursions into these waters.”

Pacific Islands

“An influx of attention and aid from larger powers has created a new locus of great power rivalry in small Pacific Island states as Chinese infrastructure and land reclamation projects have fostered academic and press speculation about potential Chinese bases and their significance for US and allied defensive positions. This increased Chinese diplomatic and economic activity has prompted concerns among leaders in some of those countries and spurred counter-efforts by Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States to expand their diplomatic, economic, and security engagement.”

Korean Peninsula

“Tensions on the Korean Peninsula, one of the few hotspots in East Asia in which China is not at its center, are unlikely to be resolved by 2025, the year that will mark the 75th anniversary of the start of the Korean War. Despite promising signs in 2018 that Pyongyang was shifting from coercion and intimidation tactics to dialogue and reconciliation with Seoul, by 2019, missile launches, military posturing, and harsh rhetoric had resumed, with North Korea destroying the inter-Korean Joint Liaison Office in June 2020 to demonstrate its lack of interest in inter-Korean rapprochement. Leader Kim Jong Un’s efforts to improve North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities run counter to South Korean, Japanese, and Western priorities to denuclearize the Peninsula and formalize peace. Moreover, North Korea’s modernization of its military capabilities presents a growing threat to its neighbors as well as stability in and around the Korean Peninsula.”

China’s Domestic Landscape in 2025

“Chinese President Xi Jinping probably will still hold power in 2025, having removed his only term limits in 2018, suggesting we will see continuity on his policy priorities, including a strong Chinese Communist Party (CCP) role in controlling society and the economy, robust support for technological and military development, and little to no tolerance for dissent.

- Beijing probably will pursue economic reforms to lower the risks of a financial crisis, increase domestic consumption, reduce administrative barriers to commerce, and attract foreign investment. However, leaders probably will preserve a guiding CCP role in major state-owned enterprises and private firms, maintain robust industrial policies, selectively intervene in markets, and control cross-border capital outflows.

- Many of China’s heavily indebted local governments, especially in interior and northeastern provinces, are likely to struggle to fund social services and new stimulus measures without substantial national fiscal reforms. China’s demographics will exacerbate these pressures, as its work force has been declining for nearly a decade and its total population could peak as soon as 2023.

- Beijing will continue to rely on security services, extensive local party and partner organizations, and propaganda to prevent citizens from acting on their grievances. Chinese leaders may continue to make minor adjustments to harsh policies targeting Uyghurs or Tibetans; however, they will persist in long-term efforts to forcibly assimilate ethnic and religious minority groups with little concern for international criticism.”