On the Great Wall with Joe Biden: A Retrospective

On the Great Wall with Joe Biden: A Retrospective

Andrew S. Erickson

As a summer intern at U.S. Embassy Beijing in 2001, I spent a day with then-Senator Biden on the Great Wall and in a nearby village. This afforded an unusual opportunity for extended conversation with him and observation of him interacting with others, particularly Chinese locals. In the two decades that I’ve had to contemplate this experience, China has changed tremendously, but human nature and media reports suggest that Biden’s temperament and leadership style have remained the same. What follows are solely my personal recollections and reflections on what is now an interesting historical footnote.

As President Biden passes 100 days in office and faces manifold policy challenges regarding China, I have a personal story to share about him there from two decades ago—in what now seems like a kinder, gentler era. It reveals nothing about policy, but perhaps much about his personality. For two hours on the Great Wall, and then in a small village nearby, I think I saw the same man that many have come to know.

In August 2001, Senator Biden visited China as Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, making this one of his very first trips in that capacity. Dr. Jill Biden, doubtless busy teaching, did not accompany him. Senator Fred Thompson, then unmarried, was likewise unaccompanied, whereas Senators Arlen Specter and Paul Sarbanes came with their wives.

Fred Thompson, Arlen Specter, and Paul and Christine Sarbanes have all passed on; Biden is now the only surviving official from the delegation.

As a summer intern in the Economic Section at U.S. Embassy Beijing, supporting this Senate Delegation was one of my duties. I escorted the Senate spouses for the duration of the visit. On the day of August 10, this dovetailed with the Senators’ itinerary as we—Senators, spouses, and support staff—all visited the second-closest Great Wall location to downtown Beijing: Mutianyu, followed by the nearby mountain village of Yanzikou.

My impressions of Biden:

- Comfortable traveling light for the long haul. He carried no bag, only a pen clipped to the placket of his white polo shirt. He was constantly walking and talking in a way that seemed indefatigable yet easy and comfortable. Measured but not artificially calibrated.

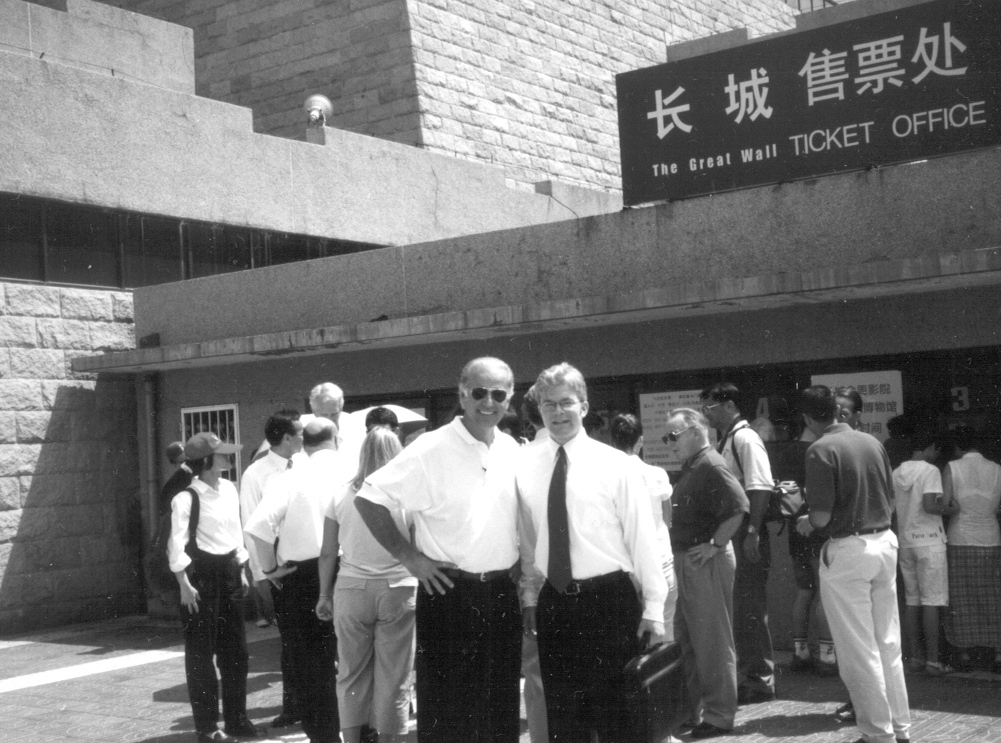

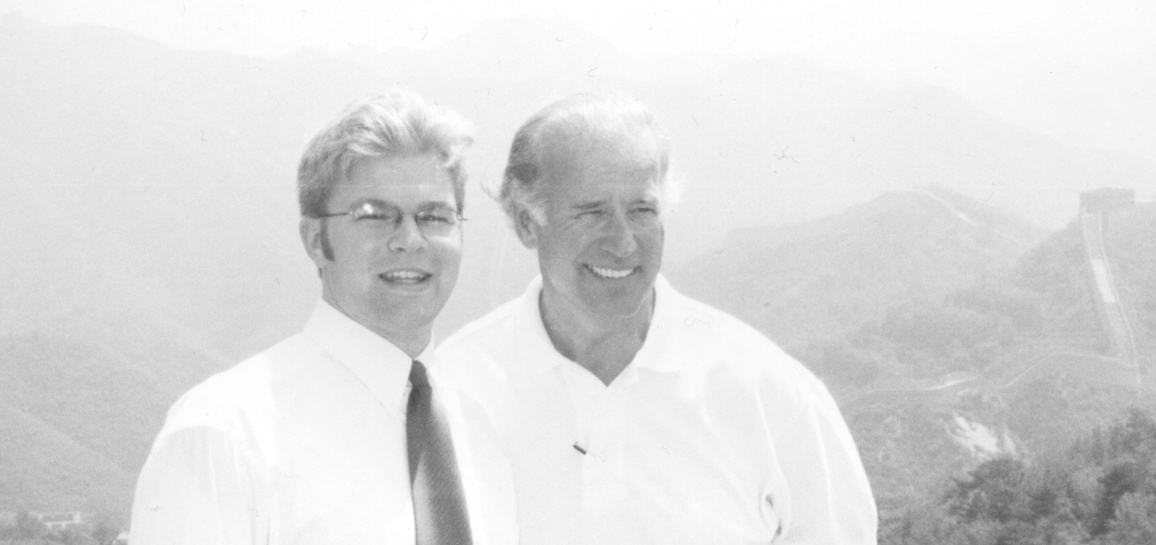

- Extremely sociable extrovert, without any pretense. It was a hot, humid day at the Great Wall (Photo 1), leaving many drenched in sweat even though we took the cable car up to the wall’s main upper section. A distinguished-looking aide with a shock of white hair attracted attention, with people drawn to him for photos assuming that he was a Senator. This, and the limited desire of many to exert themselves left Biden with a small immediate audience for the interpersonal conversation that clearly drove him as an individual: to my great surprise, much of that audience was me! For perhaps two hours I had much of Biden’s attention as we hiked up some of the inclines along the wall’s undulating path and enjoyed some great views (Photo 2).

PHOTO 1: The author escorting Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Joe Biden, together with other U.S. Senators, as a U.S. Embassy Beijing intern at the Great Wall, China, August 10, 2001 (Mutianyu Ticket Office).

PHOTO 2: The author with Senator Biden, on Great Wall at Mutianyu, August 10, 2001.

- Unassuming man of the people. What Biden was clearly drawn to, and enjoyed most, was meeting others on their own terms. Having spent a summer in Washington as a Senate intern, and with other college internships in the Peace Corps Headquarters, the U.S. Consulate General Hong Kong and Macau, and the White House Office of Management and Budget, I knew that some politicians were surprisingly introverted, and some had very different public “on” and private “off” personas. Not Joe Biden. For him, it was all friendly interpersonal exchanges all the time. I simply don’t know what he would have done without other people with whom to relate.

- I dearly wish in retrospect that I had asked Biden all about his meetings and his thoughts on U.S.-China relations—none of which I was privy to at the time. But he was the ultimate conversationalist, and he made our conversation about me. He asked all about my experience interning at the Embassy, and commended my interest in public service. He asked all about my family, and my community, the way an affable sports coach or other pillar of local society might. It reminded me of some of the key figures in my small hometown of Williamstown, Massachusetts, only at a whole other level of intensity and scope. Biden kept talking constantly yet engagingly, maintaining a friendly momentum that I haven’t experienced before or since.

- Biden exuded empathy and led through friendly rapport. It was a fascinating contrast with Secretary of State Colin Powell, whose July 28–29, 2001 visit to meet with President Jiang Zemin and other top PRC officials I had supported only days before. Powell was equally impressive and distinctive, but with an entirely different personality. He quietly commanded respect, exuding maximum authority with minimal speech in a way I have seldom witnessed. (Helping to escort PLA Navy Commander Wu Shengli at Harvard in 2014 offered me a rare reminder of such a quintessential military bearing—the air of command, personified. As with Biden’s easy extroversion, these are core personality traits that cannot be learned or altered, much less effected artificially.) After shuttling documents between the Embassy and Powell’s suite at the St. Regis Hotel around the clock, and later facilitating their disposal as appropriate, I met Powell leaving his room in the morning. What would have been a jovial conversation with Biden was a respectful several-word exchange with Powell. Similarly powerful and impressive, similarly unforgettable, entirely different in expression.

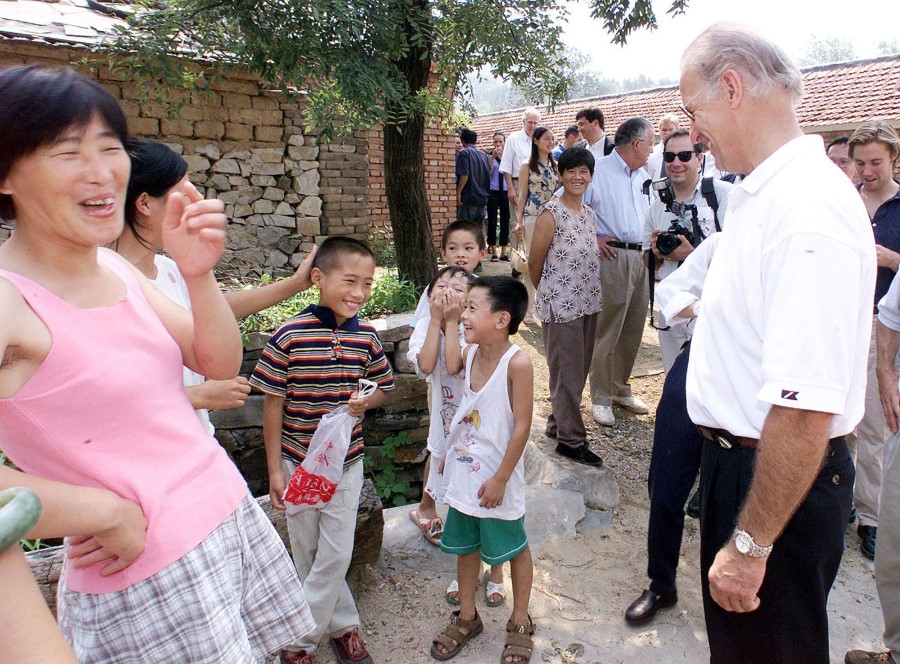

- The very same Joe Biden showed up on our subsequent stop down narrow dusty roads in Yanzikou Village. In a more typical dynamic this time, people who knew he was important in some way surrounded him. Together with my other responsibilities, this prevented me from having a personal conversation. Instead, I became a nearby observer (Photo 3). I saw Biden interact with villagers, from children to elders, on universal terms. Much of it tended to require little translation. There was much smiling and laughter.

- Things became far more serious when Biden entered a tiny village church to receive the Sacrament of Holy Communion from a Roman Catholic priest. I will never forget the look in the Father’s eyes—I fear that he had been prewarned by PRC government minders on no uncertain terms what would be the consequences for him and his flock should he attempt to convey any concerns to Biden regarding religious freedom or other human rights issues.

- Even with this dark cloud of PRC state repression overhanging everything, it was a transcendently beautiful moment. In this arid corn-growing village at the end of a small dirt road there was a powerful universal connection. I think nobody could miss it, regardless of their beliefs. Here again, this appeared to be part of the character and sense of community that Biden brought with him everywhere. For Biden people, not things, always seemed to be the focus.

All too soon, a magical day drew to a close. The American group separated into our different vehicles to navigate the gathering traffic back into urban Beijing. Within days, my summer at U.S. Embassy Beijing would end. I would fly back stateside to begin graduate school early the next month.

At the time, I had no idea that Biden would become President two decades later. He could not have known this either. I certainly knew that he was one of a handful of leading politicians who repeatedly sought the Presidency. I also knew, from reading during my first summer in Washington (1997), how hard he had campaigned previously, how hard a challenge it can be for any candidate, and how hard it had proven for him. What It Takes: The Way to the White House, a surprisingly gripping 1,072-page tome by Richard Ben Cramer detailing the 1988 Presidential race, had particularly impressed all these factors upon me.

The China that Biden and I experienced that summer was, in some ways, very different from the China he now confronts as President, which is vastly more wealthy, powerful, and assertive. In retrospect, summer 2001 was right after the April 1, 2001 EP-3 crisis and two years after the May 7, 1999 Belgrade Embassy Bombing. Things were changing quickly and dark clouds were gathering. That summer, as Biden and I climbed the Great Wall, Beijing was already moving out on its long-term competition with the United States and putting the pieces in place. And yet, in a traumatic transformation with enduring ramifications for U.S. policy, it was only weeks before September 11, which changed Washington’s approach to the region considerably. Twenty years later, Biden is doubtless the same man in disposition and outlook, but China is clearly far more confident and capable. The children he interacted with are now adults. In so many ways, there is simply no returning to August 2001, for any of us.

To this day, I do not know personally how Biden thinks about China and the challenging issues surrounding it. But I do think I was afforded a revealing glimpse into aspects of his personality, and style of leadership, that surely endure. I believe that human dignity, empathy, and common humanity are values that Biden holds dear, and that personal relationships and interpersonal communications are key channels through which he seeks to pursue them. Clearly, the way to his mind is through his heart. Whatever their intentions, those attempting to influence his thinking and decision-making will surely be most effective when appealing along these lines.

I hope to support those who advocate policies that uphold universal ideals in China and around the world as surely as here in the United States. To that end, while China policy may be more challenging and complicated than ever for an American President, it seems to me that Biden could not fail to react compassionately to any aspect of human suffering if it were brought before him in a heartfelt, personal appeal.