Important New CRS Report by Caitlin Campbell: “China’s Military: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA)”

Caitlin Campbell, China’s Military: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) R46808 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 4 June 2021).

Click here to download a cached copy.

China’s military modernization is a major factor driving some observers’ concerns about China’s rise, China’s intentions toward the United States and its allies and partners, and the role China aspires to play in the world. China’s military progress also informs the widely-held view that the United States and China are engaged in a “great power competition.” Congressional actions on these issues could shape, and be shaped by, U.S. defense strategy, budgets, plans, and programs; U.S. policy toward China, U.S. partners and allies in the Indo-Pacific, and the region more generally; and U.S. defense industrial policies, among other things.

The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s or China’s) ruling party, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is modernizing, reforming, and reorganizing its military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), to defend the Party’s interests and meet defense requirements set by China’s leaders. These interests and defense requirements have expanded in recent decades as China’s economic and geopolitical power and ambitions have grown.

The CCP’s national defense priorities include defending the Party; protecting what it views as China’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and unity; protecting China’s growing overseas interests; deterring nuclear attacks and maintaining a nuclear counterattack capability; and deterring and countering acts it views as terrorism. Some of the Party’s national defense objectives, such as safeguarding the CCP’s control over the country and deterring nuclear attacks, have been in place for several decades. Others are more recent, such as safeguarding China’s overseas interests and its interests in space and cyberspace.

China presents its military posture as purely defensive, serving only to protect China’s legitimate sovereign interests. It calls its national military strategy “active defense,” a concept that prescribes the ways in which China can defend its interests and prevail over a militarily superior adversary. This strategy allows for the use of offensive operational and tactical approaches, and the PLA has and continues to develop capabilities to wage offensive operations across a range of domains.

China’s current military modernization push began in 1978 and accelerated in the 1990s. Xi Jinping, the General Secretary and “core leader” of the CCP, Chairman of the CCP’s Central Military Commission, and State President, has continued to make military modernization a priority and has linked military modernization to his signature issue: the “China Dream” of a modern, strong, and prosperous country. In 2017, Xi formalized three broad goals for the PLA: (1) to achieve mechanization of the armed forces and to make significant progress toward what the United States would call a “networked” force by 2020; (2) to “basically complete” China’s military modernization process by 2035; and (3) to have a “world-class” military by 2049, the centenary of the establishment of the PRC. Xi has initiated the most ambitious reform and reorganization of the PLA since the 1950s, in an effort to transform the military into a capable joint force as well as to further consolidate control of the PLA in the hands of Xi and the CCP.

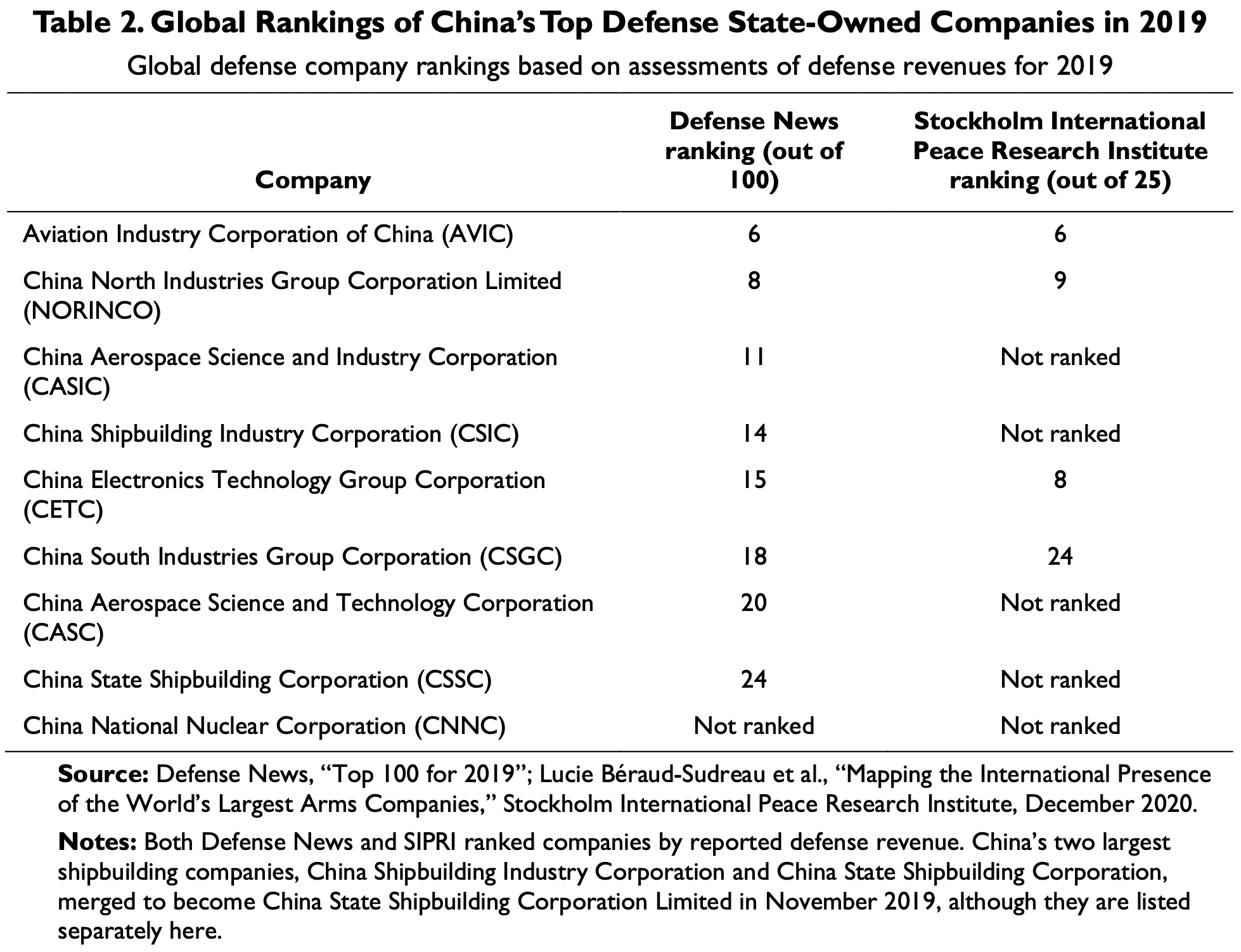

After decades of modernization supported by steady defense budget increases and other policies that promote military-technological advances, the PLA has become a formidable regional military with growing power projection capabilities. China’s armed forces are improving capabilities in every domain of warfare, have superior capabilities to other regional militaries in many areas, and are eroding U.S. military advantages in certain areas. China’s missile force, in particular, can put at risk a large range of targets in the region, including U.S. and allied bases. The PLA faces significant challenges and limitations, however, including a lack of combat experience, insufficient training in realistic combat scenarios, a limited ability to conduct joint operations, limited expeditionary capabilities, a new and largely untested organizational structure, and a dependence on foreign suppliers for certain military equipment and materials. … … …

p. 1

Introduction

The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s or China’s) ruling party, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), has built itself a modern and regionally powerful military. Decades of military modernization have transformed the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) from a bloated, low- technology, ground forces-centric force to a leaner, more networked, high-technology force.1 Increasingly capable across multiple warfare domains, the PLA has reached parity with the U.S. military in several areas and is strengthening its ability to “counter an intervention by an adversary in the Indo-Pacific region and project power globally,” according to the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD).2 Outside observers and the PLA itself also acknowledge that the PLA faces uncertainties and limitations, many of which the PLA is seeking to address, including through an ambitious reform and reorganization initiative begun in 2015.

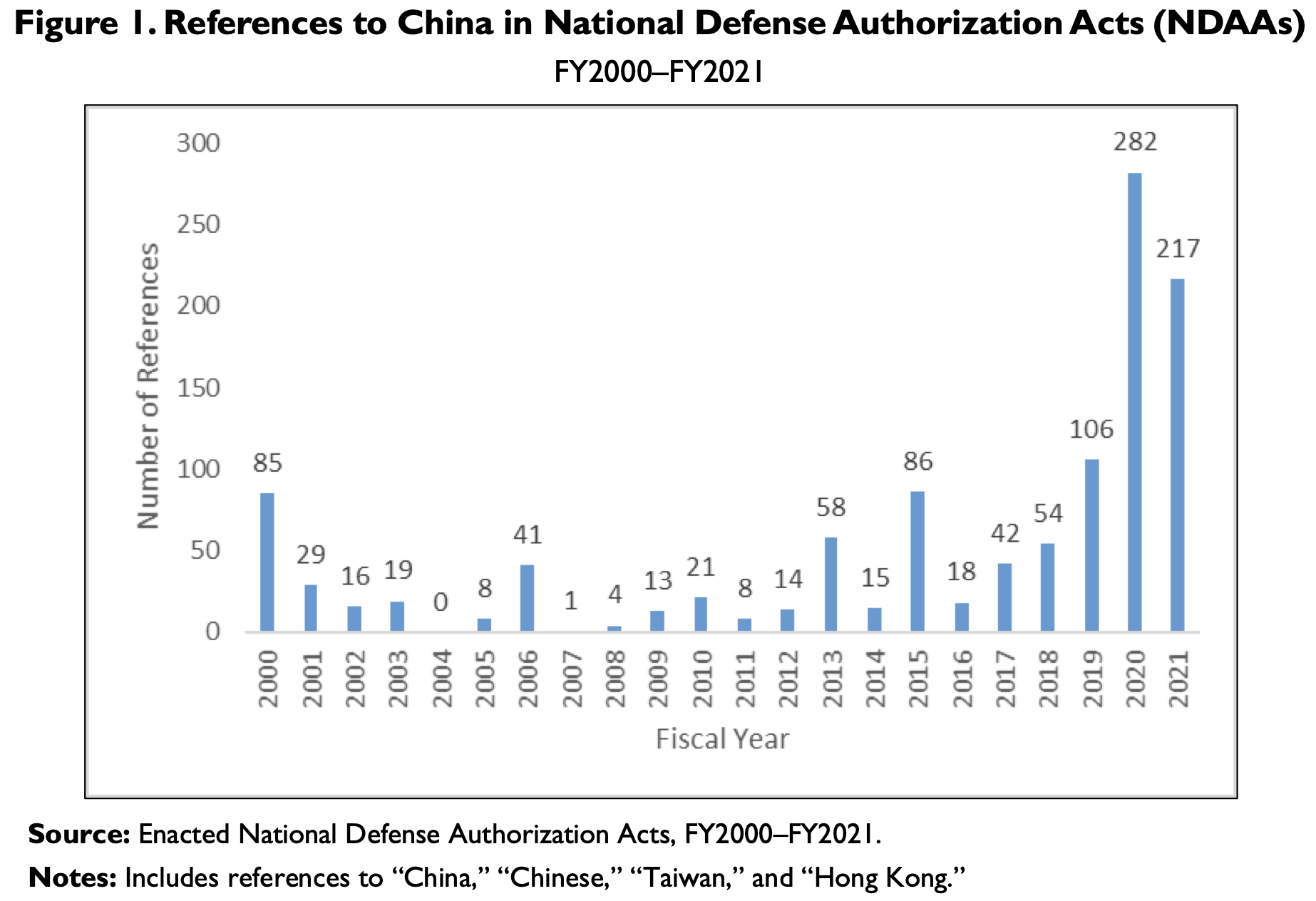

U.S. policymakers and observers increasingly describe China’s military buildup as a threat to U.S. and allied interests. This view reflects concerns about PLA capabilities—many of which appear designed specifically to counter U.S. military power—China’s growing economic and geopolitical power, and uncertainty about China’s regional and global intentions. Some Members of both parties in Congress have argued that meeting this perceived challenge requires the United States to strengthen its military advantages, and address major vulnerabilities, vis-à-vis China. Congressional decisions on this issue could shape, and be shaped by, U.S. defense strategy, budgets, plans, and programs, and the U.S. defense industrial base, among other things.

This report discusses issues for Congress related to the PLA, the PLA’s ongoing reform and reorganization efforts, the PLA’s roles in advancing China’s national security interests, major features of China’s strategic outlook, PLA capabilities and modernization, uncertainties related to PLA capabilities, and the resources that fuel PLA modernization. In order to cover a wide range of topics in a concise format, the report does not go into great depth on some topics and omits other topics that might be considered germane.

CRS products that provide additional background on issues related to China’s military include

- CRS In Focus IF11719, China Primer: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), by Caitlin Campbell

- CRS In Focus IF11712, China Primer: U.S.-China Military-to-Military Relations, by Caitlin Campbell

- CRS Report R43838, Renewed Great Power Competition: Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke

- CRS Report RL33153, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke

- CRS Report R42784, S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke

- CRS Report R45898, S.-China Relations, coordinated by Susan V. Lawrence

- CRS In Focus IF10275, Taiwan: Political and Security Issues, by Susan V. Lawrence

- CRS Report R41007, Understanding China’s Political System, by Susan V. Lawrence and Michael F. Martin

p. 33

China’s Three Maritime Forces

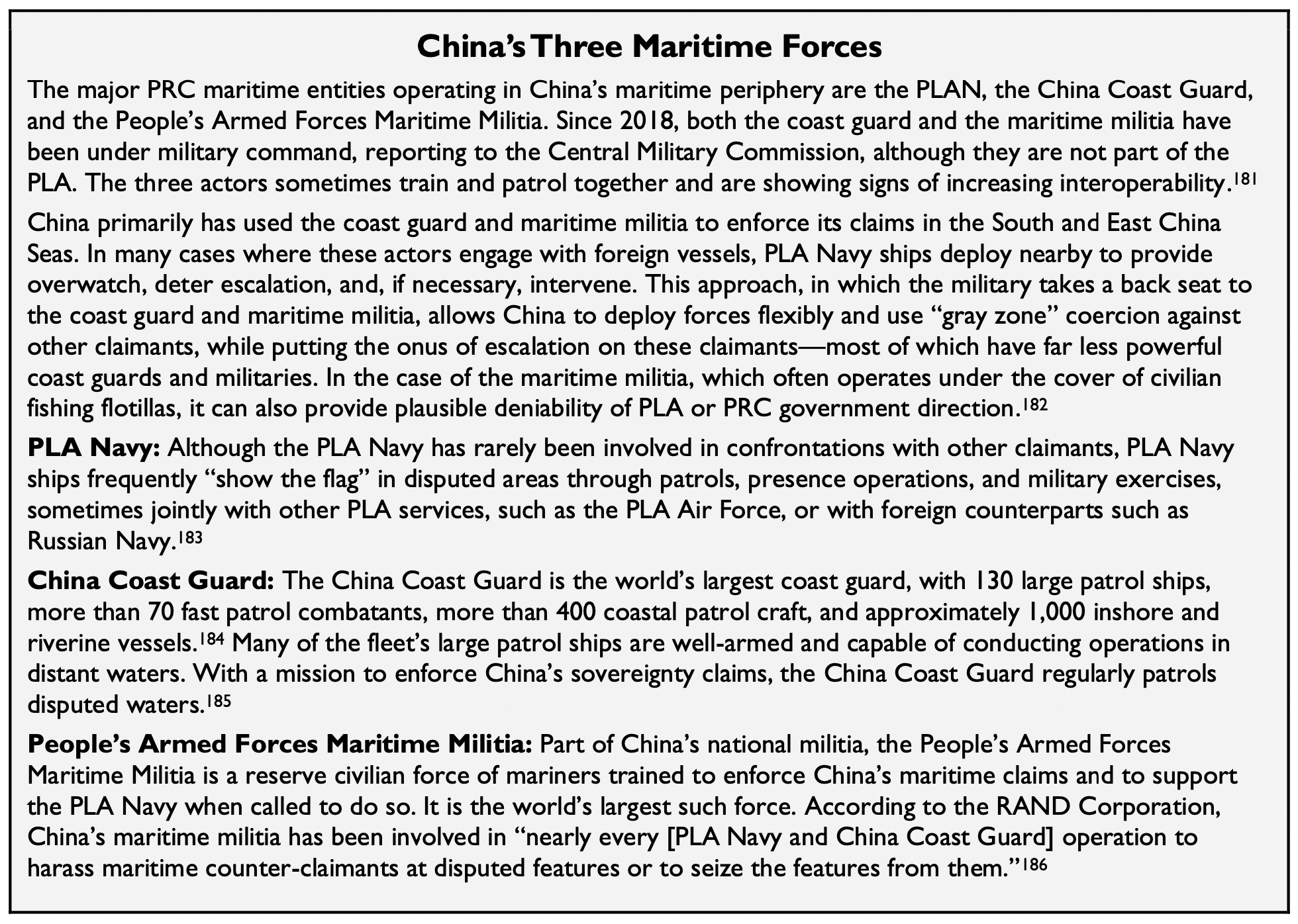

The major PRC maritime entities operating in China’s maritime periphery are the PLAN, the China Coast Guard, and the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia. Since 2018, both the coast guard and the maritime militia have been under military command, reporting to the Central Military Commission, although they are not part of the PLA. The three actors sometimes train and patrol together and are showing signs of increasing interoperability.181

China primarily has used the coast guard and maritime militia to enforce its claims in the South and East China Seas. In many cases where these actors engage with foreign vessels, PLA Navy ships deploy nearby to provide overwatch, deter escalation, and, if necessary, intervene. This approach, in which the military takes a back seat to the coast guard and maritime militia, allows China to deploy forces flexibly and use “gray zone” coercion against other claimants, while putting the onus of escalation on these claimants—most of which have far less powerful coast guards and militaries. In the case of the maritime militia, which often operates under the cover of civilian fishing flotillas, it can also provide plausible deniability of PLA or PRC government direction.182

PLA Navy: Although the PLA Navy has rarely been involved in confrontations with other claimants, PLA Navy ships frequently “show the flag” in disputed areas through patrols, presence operations, and military exercises, sometimes jointly with other PLA services, such as the PLA Air Force, or with foreign counterparts such as Russian Navy.183

China Coast Guard: The China Coast Guard is the world’s largest coast guard, with 130 large patrol ships, more than 70 fast patrol combatants, more than 400 coastal patrol craft, and approximately 1,000 inshore and riverine vessels.184 Many of the fleet’s large patrol ships are well-armed and capable of conducting operations in distant waters. With a mission to enforce China’s sovereignty claims, the China Coast Guard regularly patrols disputed waters.185

People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Part of China’s national militia, the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia is a reserve civilian force of mariners trained to enforce China’s maritime claims and to support the PLA Navy when called to do so. It is the world’s largest such force. According to the RAND Corporation, China’s maritime militia has been involved in “nearly every [PLA Navy and China Coast Guard] operation to harass maritime counter-claimants at disputed features or to seize the features from them.”186

***

181 U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, May 2, 2019, p. 52.

182 Two scholars note, however: “While not all [maritime militia] activities at sea are directly controlled by the PLA in real time, the ones of greatest concern to the United States and its allies and security partners are PLA-affiliated.” Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Third Sea Force, the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA,” China Maritime Report 1 (March 2017), p. 8.

183 Sam LaGrone, “China, Russia Kick Off Joint South China Sea Naval Exercise; Includes ‘Island-Seizing’ Drill,” USNI News, September 12, 2016, at https://news.usni.org/2016/09/12/china-russia-start-joint-south-china-sea-naval- exercise-includes-island-seizing-drill; Ryan Browne, “US Navy Has Had 18 Unsafe or Unprofessional Encounters with China Since 2016,” CNN, November 3, 2018, at https://www.cnn.com/2018/11/03/politics/navy-unsafe-encounters-china/index.html.

184 U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, China Military Power Report, January 3, 2019, p. 78.185 Shun Niekawa, “Chinese ships set 65-day record for closing in on Senkaku waters,” The Asahi Shimbun, June 17, 2020, at http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/13465411.

186 Derek Grossman and Logan Ma, “A Short History of China’s Fishing Militia and What It May Tell Us,” The RAND Blog, April 6, 2020, at https://www.rand.org/blog/2020/04/a-short-history-of-chinas-fishing-militia-and-what.html.