“China Is Using Tibetans as Agents of Empire in the Himalayas”—Part 2 in Pathbreaking Foreign Policy Series

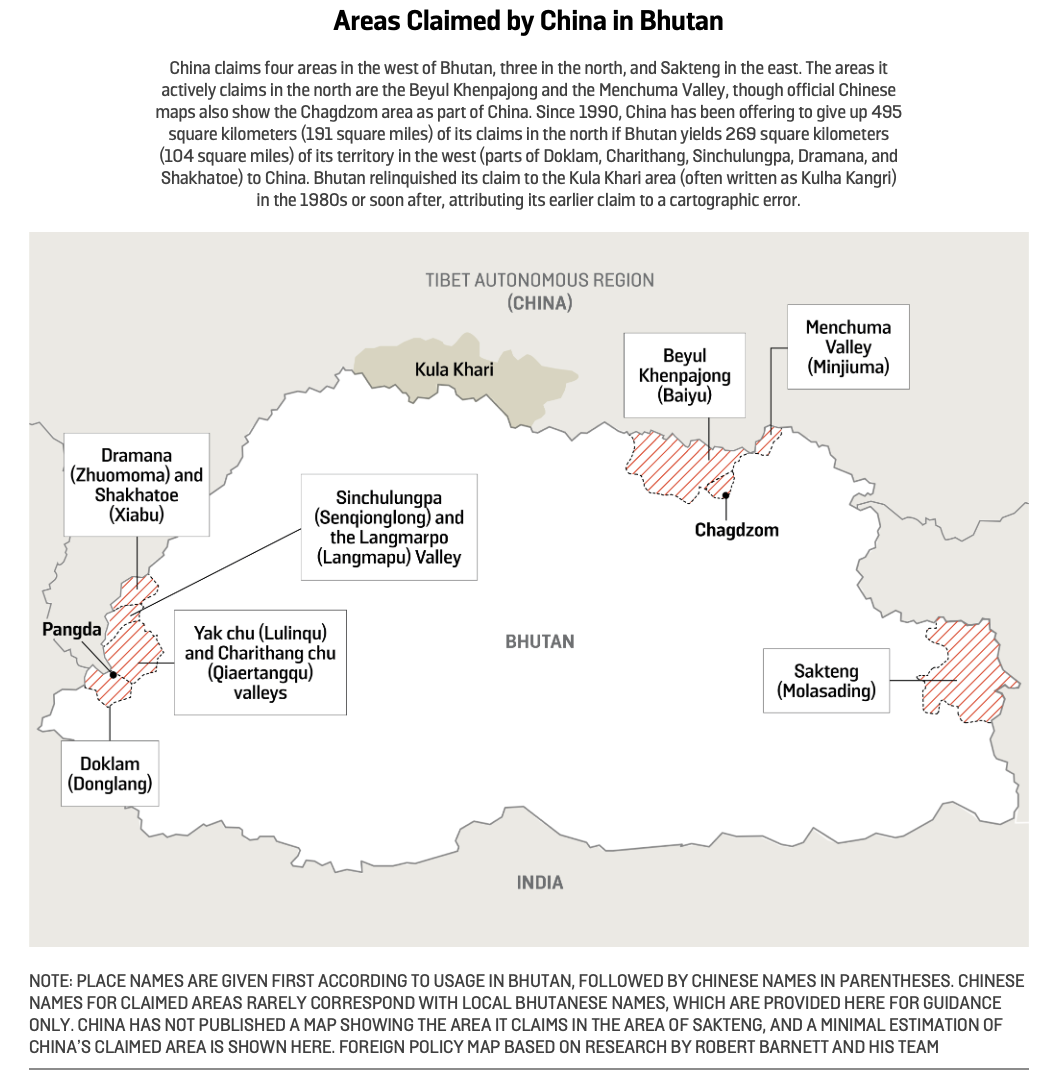

It’s not often that an article opens up a major window into a vital, under-studied area. Leading Tibetan scholar Robert Barnett and colleagues do so by probing acutely the intersection of geopolitics with the lives of those compelled to serve in frontline positions by Party persistence. This must-read piece, like its predecessor in a two-part Foreign Policy series, does all that, and more… Be sure to read the full text for fascinating details published nowhere else. And definitely don’t miss the informative map and many revealing photos—many of which show immediately why there were no substantial “settlements” in these contested but climatically harsh hinterlands before PRC policies placed some there strategically.

Robert Barnett, “China Is Using Tibetans as Agents of Empire in the Himalayas,” Foreign Policy, 28 July 2021.

What life is like for the quarter-million residents of fortress villages in Tibet.

In April 1998, with the Himalayan passes still more than 6 feet deep in snow, Penpa Tsering, a 22-year-old Tibetan herder, set off to the south from his home in Tibet across a remote 15,700-foot-high pass called the Namgung La. He was leading a train of a dozen yaks carrying tsampa (parched barley flour), rice, and fodder.

Penpa Tsering had been dispatched by the village leader of Lagyab, a settlement in Lhodrak county nearly 7 miles northeast of the Namgung La as the crow flies, to take desperately needed supplies to four other Tibetan herders who were spending the winter in a remote grassland area at 14,200 feet on the south side of the pass. Without the food that Penpa Tsering’s yaks were carrying, the herders would not survive the winter. After one day and one night of walking, Penpa Tsering reached his fellow herders and saved their lives. They later said they had expected to die. But Penpa Tsering never made it back to Lagyab: He died in an avalanche as he tried to find his way back across the pass.

In the Chinese media reports on which this account is based, Penpa Tsering’s death is presented as an act of martyrdom, a minor figure in the pantheon of China’s model citizens. His sacrifice, however, was unnecessary. The men he saved were overwintering in the high pasturelands not to improve their lives or to help their flocks but as pawns in an imperial project designed and driven by politicians in Beijing, 1,600 miles away. Today, that project has expanded into a vast network of quasi-militarized settlements along—and sometimes across—China’s Himalayan borders. Its purpose is to strengthen China’s geopolitical position in the region; it has little or nothing to do with the welfare or interests of the herders. But it cannot function without them.

No nomad freely overwinters in a tent at more than 14,000 feet on the south side of the eastern Himalayas, where storms and snowfall are especially dangerous and access is impossible for six months of the year. Normally, the four men on the south side of the pass would have returned months earlier to the shelter of their families and homes in Lagyab, only a 29-mile walk away and 2,300 feet lower in altitude, long before winter had set in. But someone in the Chinese bureaucracy had decided… that the site of the nomad’s camp was “very important and someone needs to be stationed there all year-round.”

The reason for that decision lay in a new territorial claim by China. As Foreign Policy detailed in Part 1 of this investigation, the Namgung La marks the traditional border between Tibet and Bhutan. Thirty years after China annexed Tibet in the 1950s, Beijing changed its view of that border and declared that a 232-square-mile area of northern Bhutan, lying to the south of the Namgung La, had once belonged to Tibet and therefore was now part of China. That area was the Beyul Khenpajong, a remote and uninhabited region, famous throughout the Himalayas as a “hidden valley,” that is exceptionally sacred to the Bhutanese. … … …

Twenty-three years after Penpa Tsering died, the efforts of the four herders from Lagyab have seen China’s border security enhanced, Bhutan placed under increasing diplomatic pressure, and border infrastructure modernized. The herders of Gyalaphug now live in modern homes and will soon be eating tourist rice. But the prospects of any change in the ethnically stratified, colonial nature of China’s administration in Tibet have become more, not less, remote.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE IN SERIES:

Robert Barnett, “China Is Building Entire Villages in Another Country’s Territory,” Foreign Policy, 7 May 2021.

Since 2015, a previously unnoticed network of roads, buildings, and military outposts has been constructed deep in a sacred valley in Bhutan.

In October 2015, China announced that a new village, called Gyalaphug in Tibetan or Jieluobu in Chinese, had been established in the south of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). In April 2020, the Communist Party secretary of the TAR, Wu Yingjie, traveled across two passes, both more than 14,000 feet high, on his way to visit the new village. There he told the residents—all of them Tibetans—to “put down roots like Kalsang flowers in the borderland of snows” and to “raise the bright five-star red flag high.” Film of the visit was broadcast on local TV channels and plastered on the front pages of Tibetan newspapers. It was not reported outside China: Hundreds of new villages are being built in Tibet, and this one seemed no different.

Gyalaphug is, however, different: It is in Bhutan. Wu and a retinue of officials, police, and journalists had crossed an international border. They were in a 232-square-mile area claimed by China since the early 1980s but internationally understood as part of Lhuntse district in northern Bhutan. The Chinese officials were visiting to celebrate their success, unnoticed by the world, in planting settlers, security personnel, and military infrastructure within territory internationally and historically understood to be Bhutanese.

This new construction is part of a major drive by Chinese President Xi Jinping since 2017 to fortify the Tibetan borderlands, a dramatic escalation in China’s long-running efforts to outmaneuver India and its neighbors along their Himalayan frontiers. In this case, China doesn’t need the land it is settling in Bhutan: Its aim is to force the Bhutanese government to cede territory that China wants elsewhere in Bhutan to give Beijing a military advantage in its struggle with New Delhi. Gyalaphug is now one of three new villages (two already occupied, one under construction), 66 miles of new roads, a small hydropower station, two Communist Party administrative centers, a communications base, a disaster relief warehouse, five military or police outposts, and what are believed to be a major signals tower, a satellite receiving station, a military base, and up to six security sites and outposts that China has constructed in what it says are parts of Lhodrak in the TAR but which in fact are in the far north of Bhutan.

This involves a strategy that is more provocative than anything China has done on its land borders in the past. The settlement of an entire area within another country goes far beyond the forward patrolling and occasional road-building that led to war with India in 1962, military clashes in 1967 and 1987, and the deaths of 24 Chinese and Indian soldiers in 2020. In addition, it openly violates the terms of China’s founding treaty with Bhutan. It also ignores decades of protests to Beijing by the Bhutanese about far smaller infractions elsewhere on the borders. By mirroring in the Himalayas the provocative tactics it has used in the South China Sea, Beijing is risking its relations with its neighbors, whose needs and interests it has always claimed to respect, and jeopardizing its reputation worldwide. … … …