The Andrew Rhodes Bookshelf: Charting the Indo-Pacific with Maps, History & Geostrategy

Andrew S. Erickson, “The Andrew Rhodes Bookshelf: Charting the Indo-Pacific with Maps, History & Geostrategy,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 2 July 2021.

Andrew J. Rhodes is a career civil servant who has served as an expert in Asia-Pacific affairs in a variety of analytic, advisory, and staff positions across the Department of Defense and the interagency. He earned a BA in political science from Davidson College in Davidson, NC, an MA in international relations from Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, DC, and an MA in national security and strategic studies from the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, RI, from which he graduated with highest distinction. He has also received a certificate in Geographic Information Sciences from the University of North Dakota. He is an affiliated scholar of the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. The contents of all his publications reflect his own personal views alone and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Watch his multimedia presentation to the Washington Map Society as its 2019 Dr. Walter W. Ristow Prize Winner—“Thinking in Space: The Case of Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

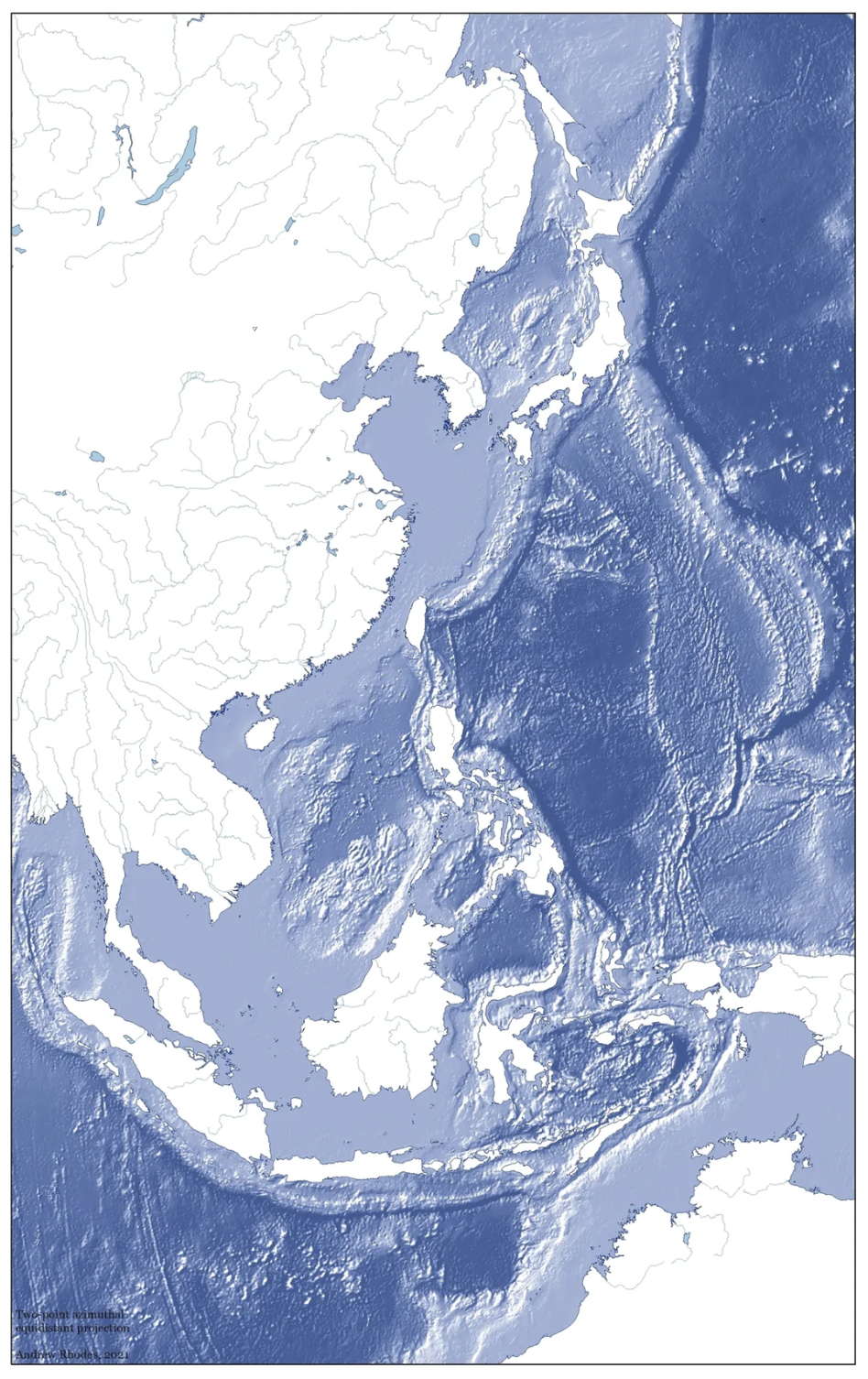

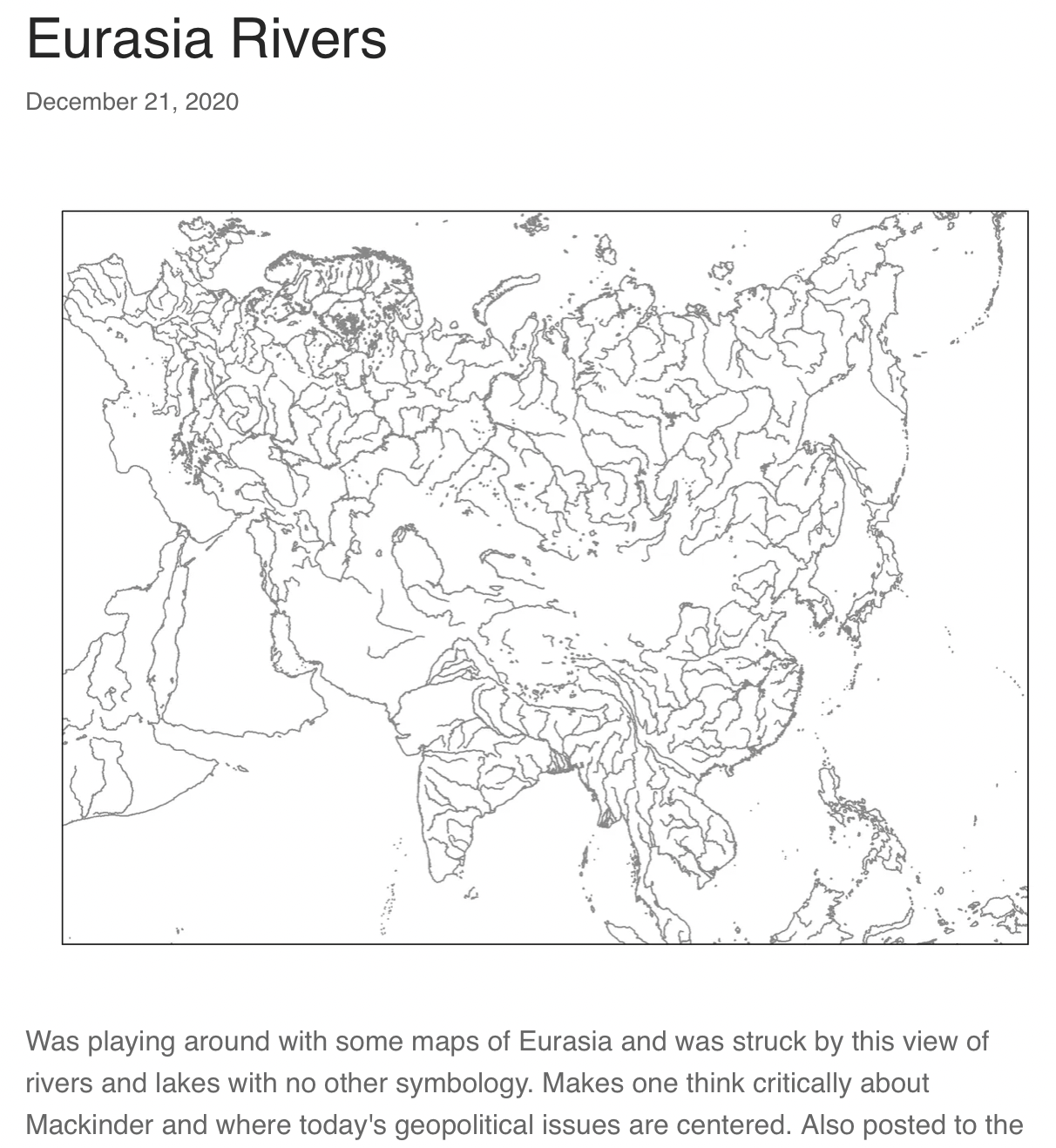

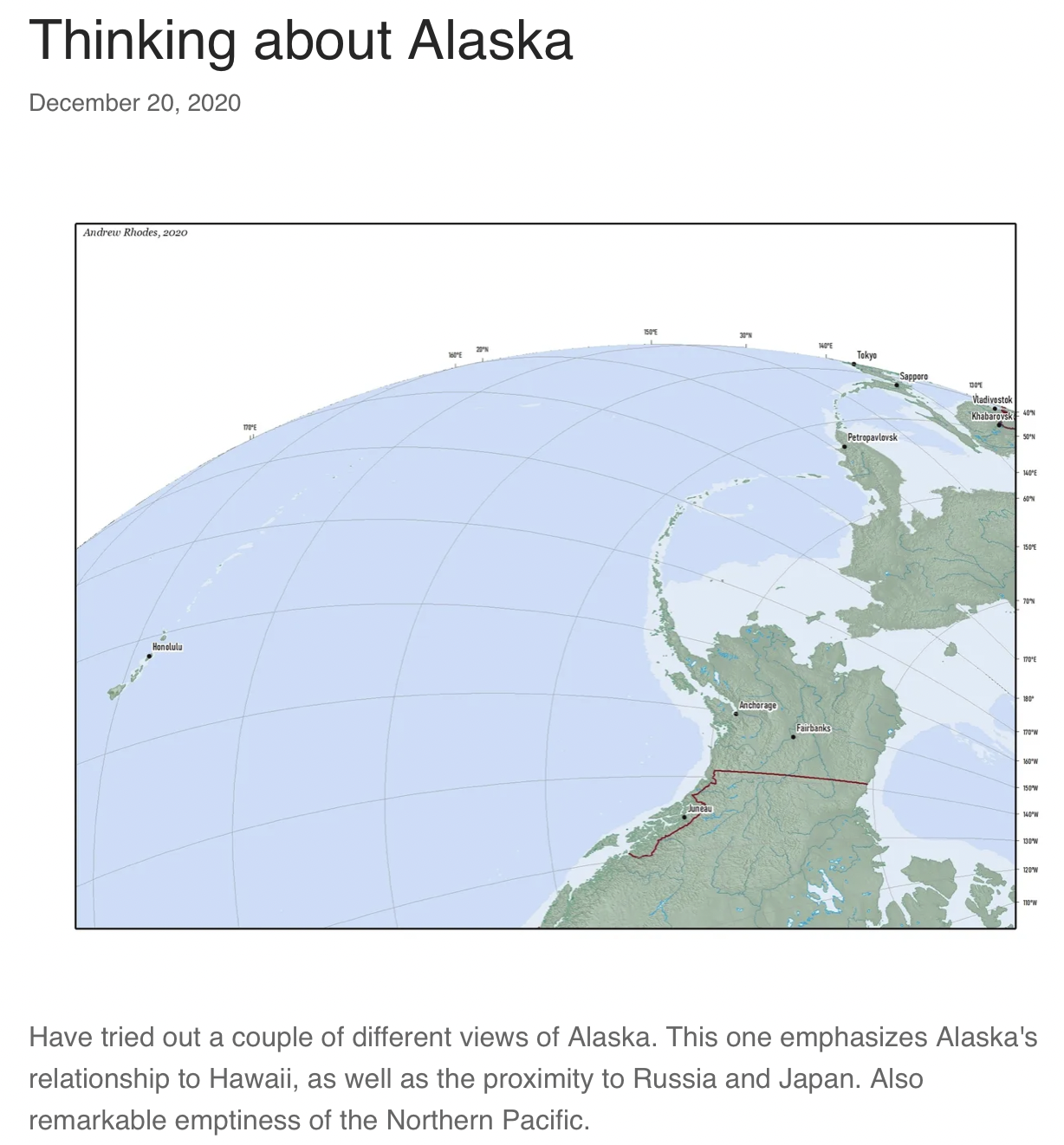

Here are some of his latest cartographic creations.

PUBLICATIONS:

Andrew Rhodes, “The 1988 Blues—Admirals, Activists, and the Development of the Chinese Maritime Identity,” Naval War College Review 74.2 (Spring 2021): 61–79.

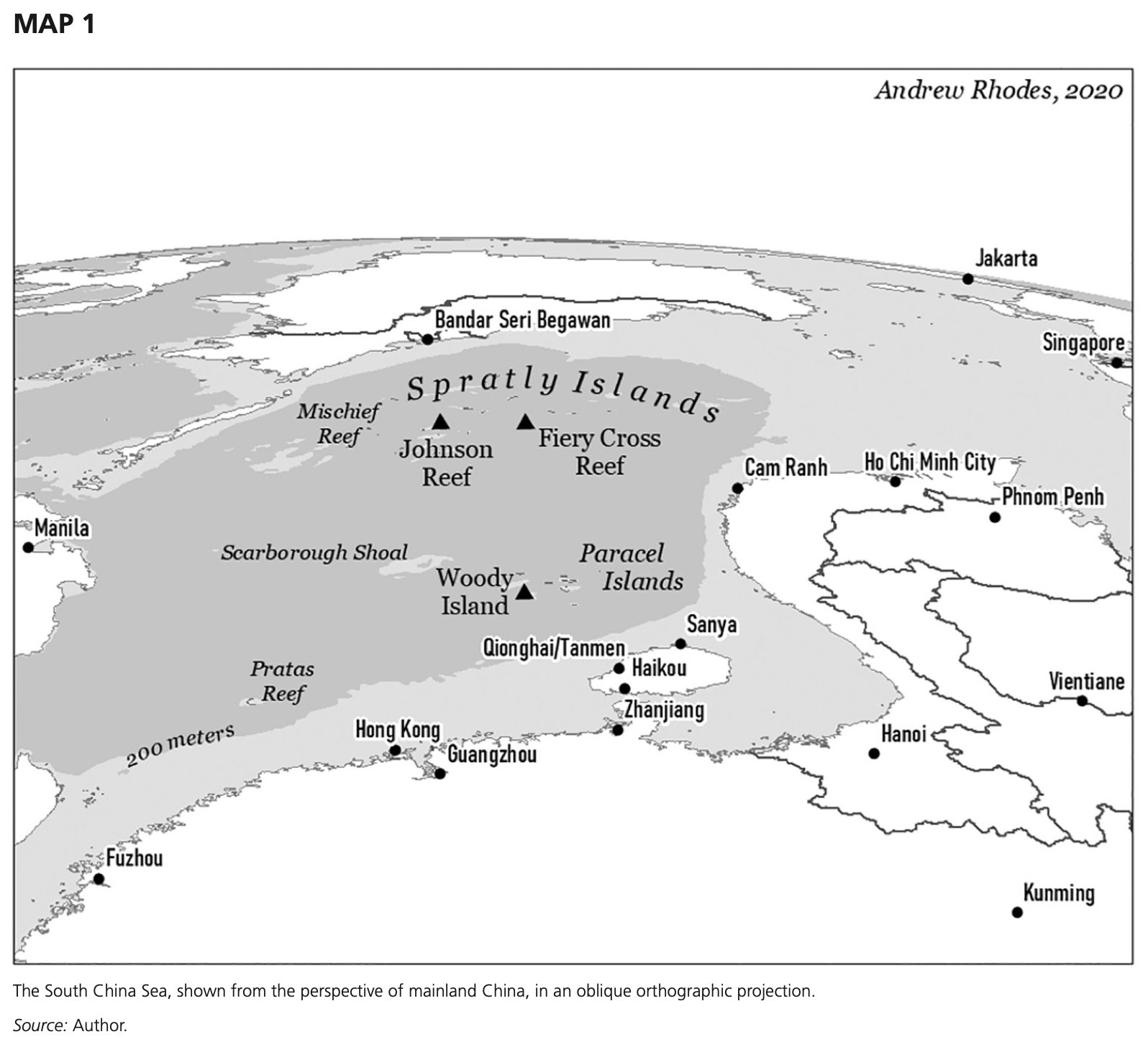

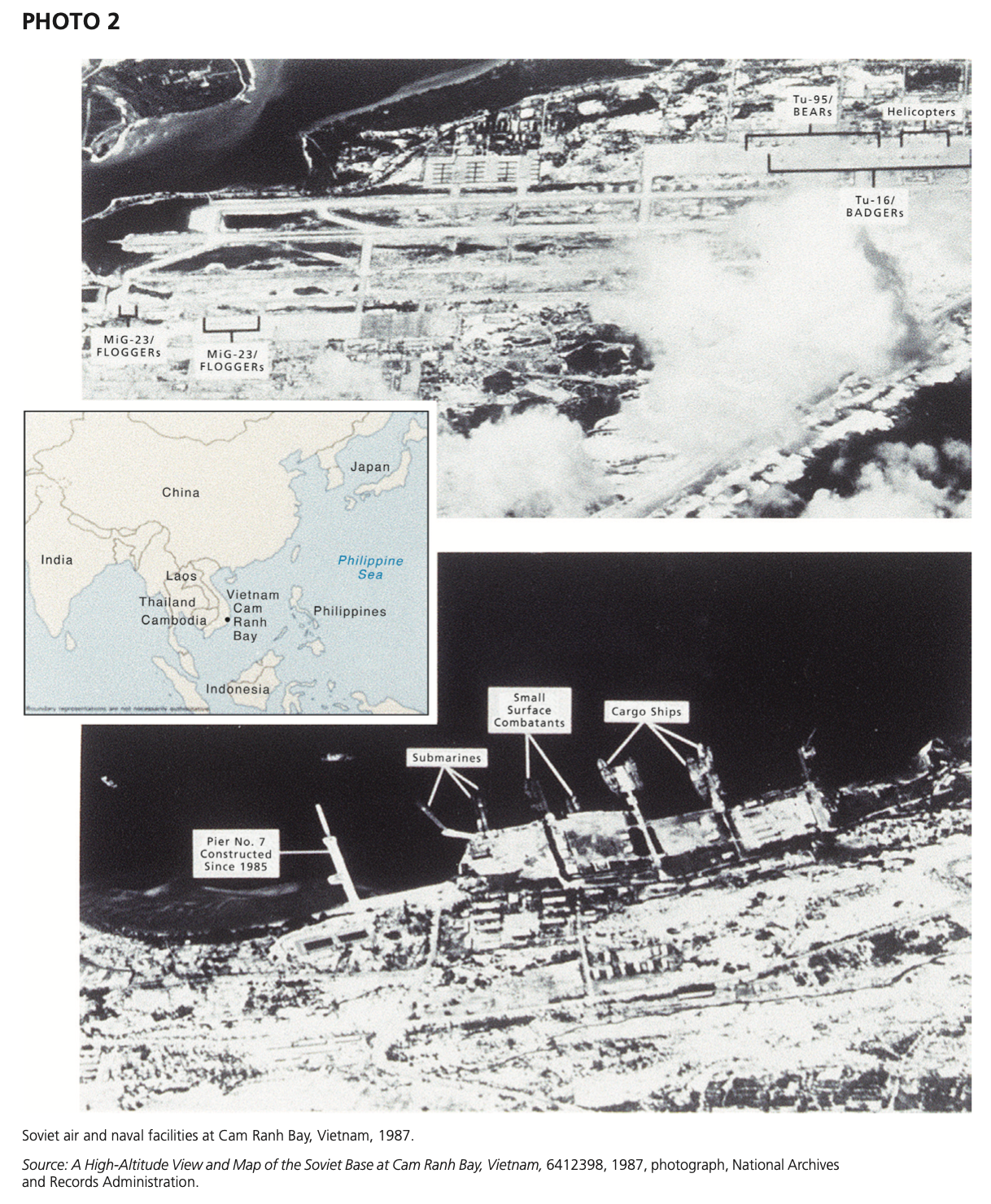

This article captures the nexus of culture and strategy in describing a key moment in the development of Chinese sea power. In the late 1980s, pro-democracy activists and the PLA were on divergent political paths, but both embraced similar language and concepts about the importance of the global maritime system. The parallel 1988 stories of the television documentary Heshang and the Navy’s campaign to occupy the Spratlys offer key insights into understanding China’s path to becoming a maritime power.

Abstract

In 1988, the views of the prodemocracy creators of a popular documentary had little in common with the PLAN leadership’s views regarding China’s governance, but there is surprising overlap in the way the two groups were “selling the sea,” helping to explain a critical moment in the evolution of China’s maritime identity and commitment to maritime power.

Text of Article

The year 1988 marked a critical moment in China’s emergence as a maritime power. The seven months from February to August 1988 saw not only a major naval campaign in the Spratly Islands but also the startling cultural phenomenon of 河殇 (Heshang, or River Elegy), a multi-episode television documentary that called on China to turn away from tradition to embrace a maritime identity.1 The prodemocracy creators of Heshang and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy (PLAN) leadership had little in common in terms of how they thought China should be governed, but there is a surprising overlap in the way the two groups were “selling the sea,” or seeking to forge a more maritime future for China.2 These two parallel stories highlight an important but overlooked historical moment in the evolution of China’s maritime identity and its commitment to maritime power.

In China in 1988, several trends were building to a dramatic, and ultimately violent, crescendo, with major implications for Chinese society and China’s place in the world. A decade after the launch of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, the movement that sought democratic political reforms and a new Chinese culture was developing powerful momentum and ties to the outside world—only to meet tragic suppression a year later at Tiananmen Square. At the same time, the PLA, and the PLAN in particular, was in the midst of its own reform and new engagement on the global stage. Consideration of the intersection of the cultural and political history of 1988 with the military and naval history of 1988 has focused—understandably—on the path to June 1989. But there are intriguing parallels, beyond mere coincidence, in the cultural and naval events of the spring and summer of 1988 that provide a new lens for viewing the relationship between Chinese culture and Chinese sea power.

Thirty-two years is not long in the grand sweep of naval history or Chinese history, but the rapid pace of PLAN development in the twenty-first century makes 1988 seem rather like the ancient past. The late 1980s are within the living memory of many scholars and strategists, but too few remember the events of 1988 and the global, regional, and national context in which they took place. For most Americans, the China of 1988 hides behind two veils—the Tiananmen Square massacre and the end of the Cold War—that obscure our view of important historical trends. Many of the key trends the world confronts today grew from seeds that already were germinating, in very recognizable ways, in 1988. A closer examination of 1988 suggests, for example, that the campaign begun in 2014 to build artificial islands in the Spratly Islands had unprecedented scope but emerged from actions driven by the “maritime mentality” and specific naval actions of 1988.3 Revisiting Heshang reveals how PLA leaders in the Xi Jinping era have echoed the language of 1988’s prodemocracy activists. The PLAN commander in 2014 wrote that China had suffered in the past because it “clung to the traditional thinking of valuing the land and neglecting the sea,” while the 2015 defense white paper called for China to abandon the “traditional mentality that land outweighs sea.”4

The next section of this article briefly will review key concepts in the literature on maritime identity and sea power, and will suggest taking a nuanced view of China’s evolution from a continental power to a more maritime power. Following this theory section, the two subsequent sections will explore the cultural dimensions and historical context in which Heshang emerged and the strategic context of the 1988 naval campaign. The final portions of the article will examine the interaction of these cultural and naval events, and how such a consideration enriches our understanding of China’s maritime identity. The article will conclude by arguing that the events of 1988 offer clear evidence that China’s commitment to sea power has been well under way for more than three decades, and has built on a surprisingly diverse basis of support over that period. … … …

***

Andrew Rhodes, “Same Water, Different Dreams: Salient Lessons of the Sino-Japanese War for Future Naval Warfare,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 11.2 (Fall 2020): 35–50.

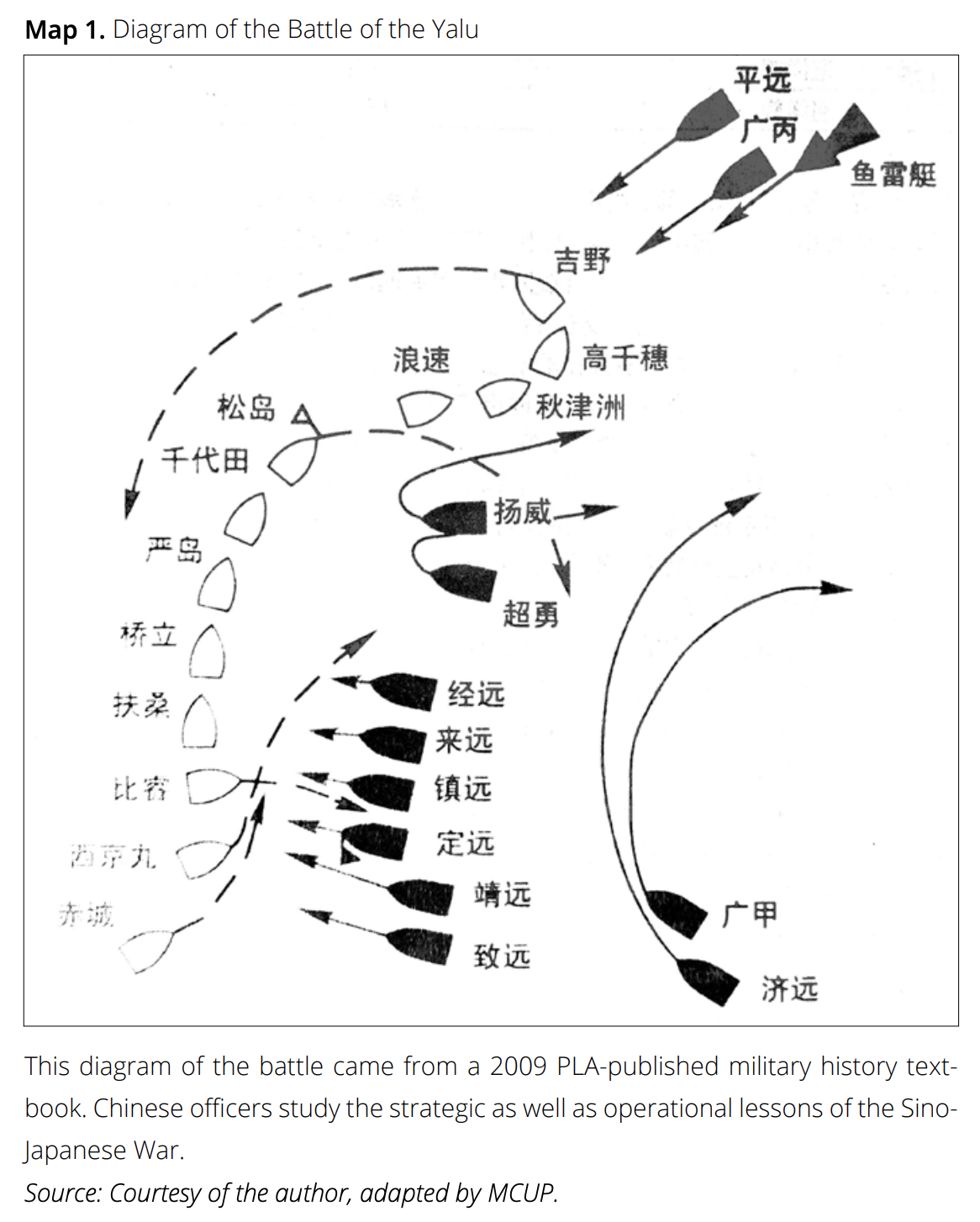

Rhodes relies on a historical example with his discussion of the salient lessons that can be learned from the Sino-Japanese War. He encourages professional military educators and planners who are developing future operational concepts to look beyond simply retelling history and consider how the legacy of this conflict might shape Chinese operational choices. He reinforces the concept that military history is not simply a resource for answering concerns about future conflict, but it encourages us to ask better questions about the role of the sea Services and how they can handle uncertainty when preparing for the future.

Abstract: American officers considering the role of the sea Services in a future war must understand the history and organizational culture of the Chinese military and consider how these factors shape the Chinese approach to naval strategy and operations. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 remains a cautionary tale full of salient lessons for future conflict. A review of recent Chinese publications highlights several consistent themes that underpin Chinese thinking about naval strategy. Chinese authors assess that the future requires that China inculcate an awareness of the maritime domain in its people, that it build institutions that can sustain seapower, and that, at the operational level, it actively seeks to contest and gain sea control far from shore. Careful consideration of the Sino-Japanese War can support two priority focus areas from the Commandant’s Planning Guidance: “warfighting” and “education and training.”

Keywords: Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), China, seapower, naval history, naval strategy, People’s Liberation Army, Qing Dynasty

Few Americans reflect on the operational and strategic lessons of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95, despite that it marks the “birth of the modern international order of the Far East.”1 For Chinese strategists and historians, this first Sino-Japanese War remains a major focus of study and a source of cautionary tales about contending for regional power and employing a navy. Indeed, 1894 was the last time China had a world-class navy: now that the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has gained international prominence, Chinese navalists have justifiably given new attention to this chapter in China’s naval history. Every nation and military Service has its own strategic culture that shapes the way contemporary issues are analyzed through historical analogy. Some of these strategic narratives are a deliberate effort to fit history conveniently to current issues, but the prevailing narrative, whatever its origins, still shapes decision making. Technological change is a major aspect of changes in the character of future naval warfare, but equally important are the stories that a Service tells itself, for these help determine choices on force design and the development of operational concepts.

This article will begin with a brief review of the maritime aspects of the 1894–95 conflict, followed by a summary of the initial conclusions that American naval officers drew from the conflict at the time, reminding American readers that this should not be an obscure conflict for the sea Services. The following section will seek to broaden American understanding of the importance of the Sino-Japanese War by reviewing recent Chinese naval and academic writing on the conflict that have not previously been translated or widely studied in the United States. Finally, the article will offer some conclusions about the key themes that emerge after studying some examples from this body of Chinese-language literature. These writings indicate that, for Chinese strategists and naval officers, the Sino-Japanese War remains an important and salient case study for thinking about the role of seapower in peacetime and in war. The Commandant’s Planning Guidance calls for correcting insufficient “discussions on naval concepts, naval programs, or naval warfare” and strengthening the presence of a “thinking enemy” in wargaming.2 The sea Services’ planners and educators should devote further study to the Sino-Japanese War and, most critically, how this history might shape future Chinese decisions. … … …

***

Commander Christopher Nelson, U.S. Navy, and Andrew Rhodes, “Embrace Analog Tools in a Digital Intelligence Age,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146.10 (October 2020).

- Naval Intelligence Essay Contest Winner—First Prize

- Cosponsored by the Naval Institute and Naval Intelligence Professionals

Summary: The naval intelligence community must strike a balance between old tools and new technology.

Commander Nelson is the deputy senior naval intelligence manager for East Asia at the Office of Naval Intelligence. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, Rhode Island.

Mr. Rhodes is a career civil servant who has served as an expert in Asia-Pacific affairs in a variety of analytic, advisory, and staff positions across the Department of Defense and the interagency. He recently graduated with highest distinction from the U.S. Naval War College and is an affiliated scholar of the Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute.

The Knowledge Professional’s Tool kit: Active Learning

There are many proven tools naval intelligence officers can use to improve this passive learning curve and embrace more active learning in training and on the job.

Physical maps, such as the one being used here by Admiral William “Bull” Halsey’s intelligence officers during World War II, can display a geographic area in its entirety at a resolution and a relative size that most computers and screens cannot match. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

A first step toward active learning begins with encouraging handwritten note-taking in training classes, and should include greater use of hand annotation in routine analysis.5 Officers trying to master the enemy’s order of battle should make their own notecards and reference documents (cheat sheets). Receiving a gouge book is not the same as making it oneself: The process of drafting a reference sheet eventually obviates the need for it—by collating, condensing, and processing the data, the officers learn it for themselves.

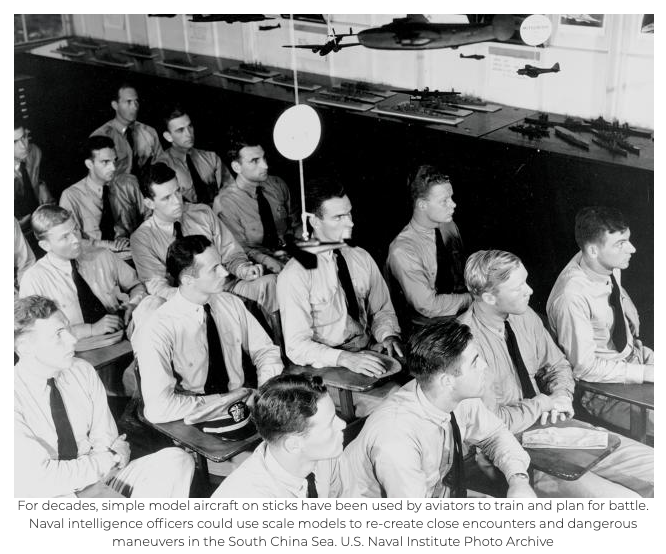

Flashcards are a proven analog tool, but what should today’s naval intelligence officers be memorizing? In World War II, intelligence officers would drill aircraft silhouettes with slideshows, and playing cards with silhouettes were popular gimmicks for teaching aircraft recognition in military and civilian populations. The nation’s more recent wars have produced decks of playing cards depicting people, such as key figures of the Iraqi regime. But the foundational knowledge of operational intelligence for the type of conflicts and adversaries prioritized by the National Defense Strategy should emphasize the right geography and technology. A deck of playing cards (or handmade flashcards) for today’s challenges should include key bases, distances between locations, characteristics of key military platforms, and the ranges and capabilities of key missile systems. In addition, in the age of what Chinese strategists call “informatized warfare,” it is essential to know (without looking it up) which parts of the electromagnetic spectrum a system uses to sense, communicate, or attack.

Finally, officers should embrace analog methods of active visualization by making their own maps and diagrams when studying a problem. Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan himself found this technique useful: He describes using cardboard models to visually re-create past naval battles as he analyzed them for his early works on sea power.6 Similar examples of effective visualization for studying operational problems and developing new solutions are the early 20th-century gaming floors at the Naval War College and the Royal Navy’s Western Approaches Tactical Unit during the Battle of the Atlantic.7 As with handwritten notes and personalized study aids, forcing a person’s mind to visualize a dynamic situation through his or her own eyes enables active study of that problem.

The Knowledge Professional’s Tool kit: Communicating

The way naval intelligence officers perform their duties has changed little in recent years, despite advances in the civilian knowledge economy.8 The use of digital tools is stale and lackluster, but bringing new digital resources to the professional toolkit is only part of the solution. Many of the operations for which these tools are needed also can be done with analog tools that serve an intelligence professional in studying the adversary, and are essential to communicating that knowledge in a coherent way.

Paper beats pixels. Large-format displays are valuable tools to illustrate a point in the moment or to serve as an “information radiator” or “kanban board” that groups can use as they come and go and a situation unfolds.9 There are good reasons why classrooms have always been filled with chalkboards, whiteboards, and maps. But in recent years, large digital screens have taken over conference rooms and displaced analog methods for large displays. Electronic displays have many advantages in the types of media they can present, but they also can reduce the resolution of the information relayed to the viewer. Statistician Edward Tufte points out that a printed sheet of paper can contain far more data and graphics than a screen, arguing that an 11” x 17” sheet folded once to be a “four-pager” easily “shows the content-equivalent of 50 to 250 typical [PowerPoint] slides.”10

For decades, simple model aircraft on sticks have been used by aviators to train and plan for battle. Naval intelligence officers could use scale models to re-create close encounters and dangerous maneuvers in the South China Sea.

Google Earth and powerful geographic information systems are valuable research and analysis tools, but analog maps remain superior in many settings. Napoleon was known to lie down on a massive table to study detailed maps with his staff; President Abraham Lincoln kept a map folded in his pocket when he visited Grant in the field; and President Franklin D. Roosevelt would study wall charts with his staff and then draw on maps to illustrate a point.11

Large physical maps or charts can do many things that images on a screen cannot. First, they can display a geographic area in its entirety at a resolution and a relative size that most computers and screens cannot match. Second, when a map is placed on a table, it encourages collaborative learning—admirals and their staffs gather around, pointing, discussing, and annotating it. This creates an interactive discussion that no digital format can accomplish. And finally, they are aesthetically pleasing. A beautiful map with the right detail has a magical effect, inviting deeper study and tactile engagement.12

At their best, knowledge management efforts do not lock users into exclusively analog or digital formats—they strike a balance. Just as ubiquitous printers make digital words and images more permanent and portable, scanners and software allow users to digitize, share, and render searchable their analog holdings. Scanners and digitization software, however, are not deployed widely enough in the intelligence community. All-source intelligence officers would be more effective with fewer barriers to scanning foreign language publications and media, preparing them for databasing and computer-assisted translation with optical character recognition, and cross-referencing with other databases. The same tools also would aid officers in storing and sharing the notes, personalized references, and visual aids they generate in active learning.

Rock beats paper.Physical objects, such as scale models and sand tables, present a three-dimensional and tactile connection to a problem set. A briefer can manipulate the object to visualize its position and context in space and time. For example:

- Manipulating multiple models together allows a briefer to tell a compelling and dynamic story. For decades, aviators have used simple model aircraft on sticks to analyze and explain the subtle relationships of speed, angles, and distance in combat engagements. Intelligence professionals should use similar means to re-create close encounters and dangerous maneuvers in the South China Sea, using detailed models that faithfully depict the relative size, shape, and motion of the ships. Briefing with this technique would take Mahan’s method for analyzing positions and use it to communicate analytic conclusions.

- Terrain and building models, from crude sand tables in the field to works by professional model makers, are another proven analog technique used to prepare units for deployment, plan daring raids, and brief Presidents.13 Today’s intelligence professionals could communicate more effectively by breaking out of formulaic slideware and embracing visual aids with three dimensions. They could strike a balance of digital and analog by using inexpensive 3D digital printers to create physical models as dynamic briefing aids.

Embrace your inner artist. The suggestions above call for intelligence professionals not only to use more analog tools, but also to employ them creatively in ways that might seem outmoded or unpolished. The true test should be the effectiveness of the communication. It was not too long ago that drawing pictures by hand was a valued skill among military officers. A hand-drawn diagram may not look as “finished” as a PowerPoint slide, but it will be truer to the precise point the officer is trying to convey, can include more details and subtlety of line than PowerPoint will ever allow, and will prove field-expedient when everything else breaks. … … …

***

Andrew Rhodes (2019 Dr. Walter W. Ristow Prize Winner), “Thinking in Space: The Case of Franklin D. Roosevelt,” Multimedia Presentation at Member Meeting, Washington Map Society, 4 June 2020.

***

Andrew J. Rhodes, “The Geographic President: How Franklin D. Roosevelt Used Maps to Make and Communicate Strategy,” The Portolan, Washington Map Society (Spring 2020): 7–16.

Winner of the 2019 Ristow Prize for Academic Achievement in the History of Cartography, the author presented a version of this article at the June 2020 WMS meeting.

Geographic literacy is not among the few constitutional requirements for holding the office of President. American Presidents have varied widely in their cognitive and communication skills, including their ability to use geographic information in support of critical thinking and to employ maps as a medium for communication. Many presidents have understood the relationship between national power and physical space, and several might stake claims to being among our most “geographic” presidents. George Washington was a surveyor and general, Thomas Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase and sponsored the Lewis and Clark expedition, James Monroe declared a hemispheric doctrine, Ulysses Grant and Dwight Eisenhower commanded armies on a continental scale, Theodore Roosevelt was an explorer, and many post-World War II presidents had practical navigation experience as soldiers, sailors, and pilots. But the president who demonstrated the most compelling use of geographic thinking and communication, despite his physical disability and a lack of military training, was the one who orchestrated American victory on a global scale: Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR).

FDR’s use of maps is evident in several key aspects. of leadership identified by the presidential scholar Fred Greenstein, including effectiveness as a public communicator, organizational capacity, vision, and cognitive style.1 FDR brought substantial political and government experience to the presidency and had developed expertise in naval issues as Assistant Secretary of the Navy during World War I, but FDR was largely self-taught when it came to geography, international relations, and military strategy. Nevertheless, his use of geography shows that his passionate curiosity, critical thinking skills, and effective communication were more important than technical skills or military experience. In an era where military service is increasingly rare among presidential candidates, FDR’s use of geography is instructive for how lifelong civilians participate in the formulation of strategy. FDR’s geographic presidency offers important lessons for how leaders can be effective thinkers, bureaucratic organizers, and public communicators. FDR employed geography as a tool in three key ways: to support his own critical thinking, to help coordinate strategy and policy among his advisors and allies, and to build public support. … …

FDR made the Map Room available only to an exclusive group of his closest advisors, like Hopkins and Marshall, but he also expected that his principal officers would be conversant in the geography of the war. McCrea recounts that Hopkins visited the Map Room every day and that FDR came to use it more and more as the war progressed. At one point, probably late in 1942, FDR ordered Secretary of War Henry Stimson to come to the Map Room on a Sunday afternoon for what FDR called a “geography lesson.” McCrea recalled that FDR asked him to move his wheelchair to the map of the Pacific where he criticized a recent memorandum from Stimson that failed to consider the tyranny of distance in the Pacific.20 In many other administrations, one might expect the geography lessons to flow in the other direction.

In addition to the globes for the Oval Office and Churchill, FDR also ordered the OSS to provide copies to the War Department and Congress. Although FDR might have thought the globe helpful for Stimson’s geography lessons, its key War Department user was Marshall. Marshall played a role in the production and delivery of the globes and discussed their value as both decision aids and symbolic gifts in correspondence with FDR and Dwight Eisenhower, who was meeting regularly with Churchill in London at the time.21

The Map Room was a key predecessor of the White House Situation Room, which continues to serve as a communications center but no longer emphasizes putting issues into a geographic context. The Map Room’s more durable legacy is the role of the Situation Room and its staff in facilitating and hosting interagency policy discussions and meetings of the National Security Council. Policy debates, strategic discussions, and occasional geography lessons still take place in the White House basement even if the walls are not (alas) lined with maps. … … …

***

Andrew Rhodes, “The Second Island Cloud: A Deeper and Broader Concept for American Presence in the Pacific Islands,” Joint Force Quarterly 95 (Fourth Quarter 2019): 46-53.

Rhodes wrote this essay while a student at the U.S. Naval War College. It won the Strategic Research Paper category of the 2019 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Strategic Essay Competition.

In the early 20th century, the visionary Marine officer Earl “Pete” Ellis compiled remarkable studies of islands in the Western Pacific and considered the practical means for the seizure or defense of advanced bases. A century after Ellis’s work, China presents new strategic and operational challenges to the U.S. position in Asia, and it is time for Washington to develop a coherent strategy, one that will last another 100 years, for the islands of the Western Pacific. It has become common to consider the second island chain as a defining feature of Pacific geography, but when Ellis mastered its geography, he saw not a “chain,” but a “cloud.” He wrote in 1921 that the “Marshall, Caroline, and Pelew Islands form a ‘cloud’ of islands stretching east and west.” His apt description of these archipelagoes serves well for a broader conception of the islands in, and adjacent to, traditional definitions of the second island chain. A new U.S. strategy should abandon the narrow lens of the “chain” and emphasize a broader second island cloud that highlights the U.S. regional role and invests in a resilient, distributed, and enduring presence in the Pacific.

The United States has often been of two minds about its role in Asia, and recent heated debate on the future of U.S. security commitments in the region is no exception. This pendulum has swung before, from the heavy presence lasting from World War II through Vietnam to a partial retrenchment under Richard Nixon’s Guam Doctrine, and back toward statements of a greater strategic emphasis on the region under the Obama administration’s “Rebalance to Asia.” Despite some inconsistent messaging on military alliances and trade relationships, the Trump administration has indicated a major focus on Asia in the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) and its strategy for a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.” Regardless of whether the United States pursues broad engagement with the region, focuses on military containment of China, or decides to allow a larger Chinese sphere of influence in the Western Pacific, the second island cloud represents critical geography for what Vice President Mike Pence has called an “ironclad commitment” to the region. To demonstrate this commitment and respond to operational imperatives, there is a compelling need to get serious about the second island cloud—we need to identify the challenges to a sustained or enhanced U.S. presence and to pursue near-term opportunities that advance U.S. national interests. A strategy for the second island cloud should deepen the unique U.S. relationship with these islands and reframe the strategic discussion with a broader definition that includes valuable islands excluded from the second island chain.

Origins and Interpretations

The second island chain has no official standing among geographers or international organizations but has served as shorthand for the line of islands extending from the Japanese mainland, through the Nanpõ Shotõ, the Marianas, and the western Caroline Islands, before terminating somewhere in eastern Indonesia. The second island chain lies to the east; the first island chain, which is also imprecise, generally comprises a line from southern Japan through the Ryukyus and Taiwan, terminating in the Philippines or Borneo. The island chains took on strategic importance for the United States when it annexed the Philippines and Guam after the Spanish-American War. The fortification of these outposts was a central feature of negotiations in the 1920s that vainly sought to prevent military competition and conflict between the United States and Japan. Michael Green notes that as much as many planners of the interwar period regretted the decision not to establish robust fortifications of strategic points such as Guam, the restrictions of the Washington Naval Treaties incentivized key innovations in fleet mobility, such as underway replenishment, to mitigate against the threat to fixed fueling points.

The notorious geopolitician Karl Haushofer was one of the first to describe the island chain concept, calling them “offshore island arcs.” Haushofer served as German military attaché in Tokyo before he established his Institute for Geopolitics at the University of Munich and gained influence in the 1930s with Nazi leaders such as Adolf Hitler and Rudolf Hess. Leading architects of the post–World War II Pacific security architecture, including Douglas MacArthur and Dean Acheson, also invoked the island chains. Chinese strategists have focused contemporary attention on the island chains, and it is Chinese adaptations and descriptions of the island chains that have reintroduced the concept to American strategists. Throughout the remarkable modernization of China’s military since the 1990s, its leaders have emphasized the military challenge of U.S. and allied deployments in the island chains and the strategic importance of the waters they enclose. A central figure in the promulgation of the island chains in Chinese geostrategy and military planning was Admiral Liu Huaqing, often referred to as the “Father of the People’s Liberation Army Navy,” who served as its commander in the 1980s and then as vice chairman of the Central Military Commission in the 1990s. One leading Chinese scholar on seapower references control over the Pacific islands as key to U.S.-led efforts to “contain China,” invokes the operational imperative to “break through” the island chains, and also highlights the power of small islands to confer broad “jurisdictional sea area.” Andrew Erickson and Joel Wuthnow catalog these discussions of the island chains concept in Chinese sources and lay out three ways that Chinese authors have thought about island chains: as barriers, springboards, and benchmarks. These three concepts provide a useful framework for not only understanding Chinese perspectives but also analyzing U.S. interests in the region. A durable U.S. regional strategy should reject what have become Chinese concepts of the islands and redefine the geography as a cloud, then consider the various roles of the second island cloud as a barrier, springboard, and benchmark. … … …

Conclusion

A stable footing in the second island cloud is worth these costs and risks, as it can serve as a strategic position and powerful symbol that transcends the operational imperatives to balance Chinese military capabilities in the near term. In the first 50 years after the United States took possession of Guam, Ellis saw the rise of Japan and envisioned key geographic aspects of its defeat that took place two decades after his death. In 1942, geostrategist Nichols Spykman foresaw that technological change and political shifts could one day make Chinese airpower more dominant than British, Japanese, or American seapower in what he called the “Asian Mediterranean.” In only 30 years, China changed from a strategic partner in the Cold War to a peer rival in a newly bipolar world. China is pursuing a much more expansive role on the international stage with new security relationships and overseas bases and is even contemplating military alliances. The coming decades will see major structural changes to the international system, and a truly long-term strategy should secure America’s Pacific position through and beyond the current competition.

Ely Ratner argues that “it is imperative that the United States stop China’s advances toward exerting exclusive and dominant control over key geographic regions.” With growing Chinese investment and influence throughout the Pacific islands, the second island cloud can play a central role in near-term efforts to avoid a power vacuum and create what Ratner calls “spheres of competition.” The current administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy and the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act passed by Congress have brought important focus to the policy discussion on the region, but sustained energy is required to realize these ambitions. In addition to developing new partnerships, Washington should double down where it is already strong—the second island cloud is squarely aligned to the United States, but U.S. policy must work hard to sustain that alignment and build on it to our advantage.

Ellis’s description of an island cloud aptly captures the complexity and diversity of the key geography and provides a framework for lasting and dispersed strength—chains fail with a single weak link, but clouds are resilient. The argument for a durable commitment to the second island cloud in the 21st century is much the same as what Ellis wrote in 1913: “Once secure it will stand as a notice to all the world that America is in the Western Pacific to stay.”

For two of the articles cited here, see:

Andrew S. Erickson and Joel Wuthnow, “Why Islands Still Matter in Asia: The Enduring Significance of the Pacific ‘Island Chains’,” The National Interest, 5 February 2016.

Andrew S. Erickson and Joel Wuthnow, “Barriers, Springboards and Benchmarks: China Conceptualizes the Pacific ‘Island Chains’,” The China Quarterly 225 (March 2016): 1-22.

***

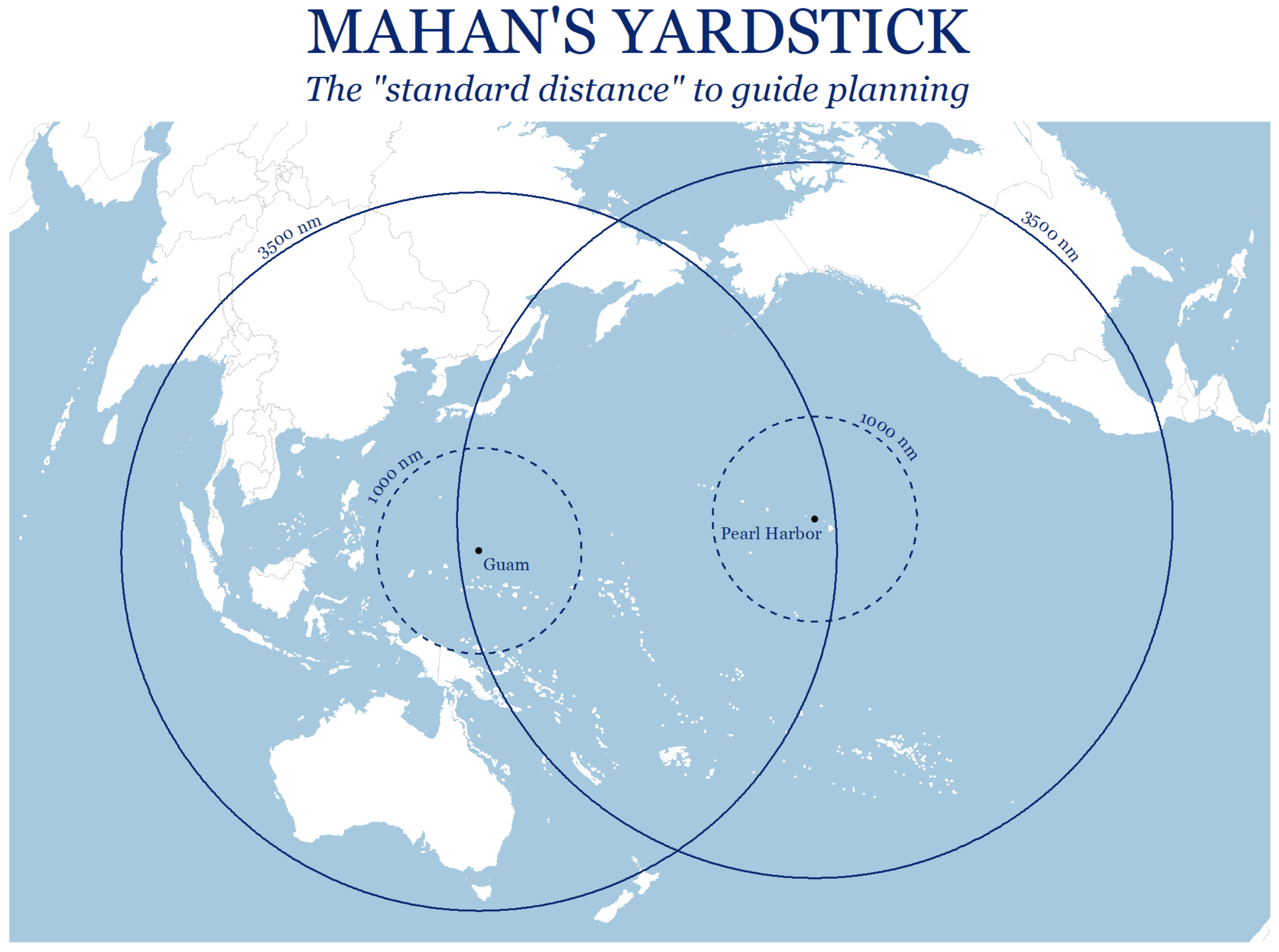

Andrew Rhodes, “Go Get Mahan’s Yardstick,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145.7 (July 2019).

Mahan’s 3,500 nm “standard distance” for naval planning may be a crude metric, but it highlights the geographic reality that must shape theater strategy and force development in the vast Pacific operating area.

Writing 120 years ago, just after the U.S. Navy burst on the world stage in the Spanish-American War, Alfred Thayer Mahan said one of the most critical numbers naval planners needed to keep in mind was 3,500. The 3,500 nautical miles (nm) from Hawaii to Guam are what he called the “standard distance” at the heart of naval planning for the United States. Mahan was making a narrow point about the importance of range to battleship design, drawing lessons from the 1898 “race to Manila” for designing a U.S. fleet that could reach the other side of the globe and defeat the enemy when it got there. Nevertheless, that same 3,500-nm distance remains a defining reality in the Pacific theater today, but few U.S. strategists fully appreciate its implications. In thinking about the challenges the nation faces in the Pacific, the Navy must consider Mahan’s yardstick at an intuitive level and also in the course of more deliberate analysis.

The Tyranny of Distance

Mahan’s standard distance is better known among sailors in the Seventh Fleet, planners stationed in Hawaii or Guam, and some policymakers in Washington. Indeed, invoking the “tyranny of distance” has become a staple of congressional testimony by Indo-Pacific Command leaders highlighting the difficulties of rapid response and the importance of forward deployment and foreign partnerships. But the challenge Mahan’s yardstick presents must be more than an Indo-Pacific Command talking point: It should be at the heart of force planning conversations on Capitol Hill and in the Pentagon and be better understood by the American people who pay for that force.

Distance is only one aspect of the operating environment in the Pacific, but low geographic literacy is a problem. In Mahan’s writings, the importance of careful study of geography and the spatial relationships that enable or inhibit concentration of the fleet’s combat power is a repeated theme. His “standard distance” may be a crude metric, but it highlights the geographic reality that must shape theater strategy and force development.

Planners who neglect this yardstick are ignoring one of the most important measures of the Navy’s effectiveness. At the expense of measuring the fleet’s reach, analysts focus on readiness levels, budgets, and total ship numbers. These metrics are essential to force management, but focusing debate on the number of ships obscures a vital issue: the ability of those ships, at the ranges of modern naval combat, to, as Wayne Hughes has argued, “attack effectively first.” A 355-ship Navy, or even a 600-ship Navy, is little better than a 280-ship Navy if those ships lack the ability to maneuver, sense, evade, and attack effectively at the ranges of naval combat in the missile age. …

Carrier aviation is not the only area of force capability where distance has been underplayed. The U.S. surface fleet is well behind Russia and China when it comes to long-range antisurface warfare, although not for any lack of technical capability. This lack of offensive reach results from conscious decisions, such as that 25 years ago to remove the Tomahawk antiship missile (TASM) from the fleet. …

And what might be the “critical distance” for 21st-century naval strategy and operational planning? There are many worthy candidates for a new Mahanian yardstick, but a strong case can be made for 1,000 nautical miles. This is roughly the distance from Shanghai to Tokyo or Manila, from Beijing to Okinawa or Hong Kong, from Singapore to Palawan, and from Jakarta to Fiery Cross Reef. It is a bit beyond the reported 810-nm (1,500-km) range of the Chinese DF-21D antiship ballistic missile—a worthy consideration, given the attention that particular weapon system has gained in the past decade. Given the possibility of new weapons entering the U.S. arsenal after a withdrawal from the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, the DF-21D range is comparable to that of a Pershing II missile, which retired Navy Captain Sam Tangredi has argued for adapting to a sea-based system. And deployment of the MQ-25 Stingray in its planned refueling role will push the air wing’s striking range close to 1,000 nm, depending on the mission profile and the range of the weapons it carries. …

The Navy must do more to inculcate an awareness of critical distance and must place greater emphasis on range, reach, and distance in force planning and strategy development. And all personnel should spend more time studying the distances in the Pacific and considering which essential strategic and operational challenges might dictate the “standard distance” for the 21st century. But until a better metric comes into focus, measure off 3,500 nm on a good chart of the Pacific and keep Mahan’s yardstick handy.

***

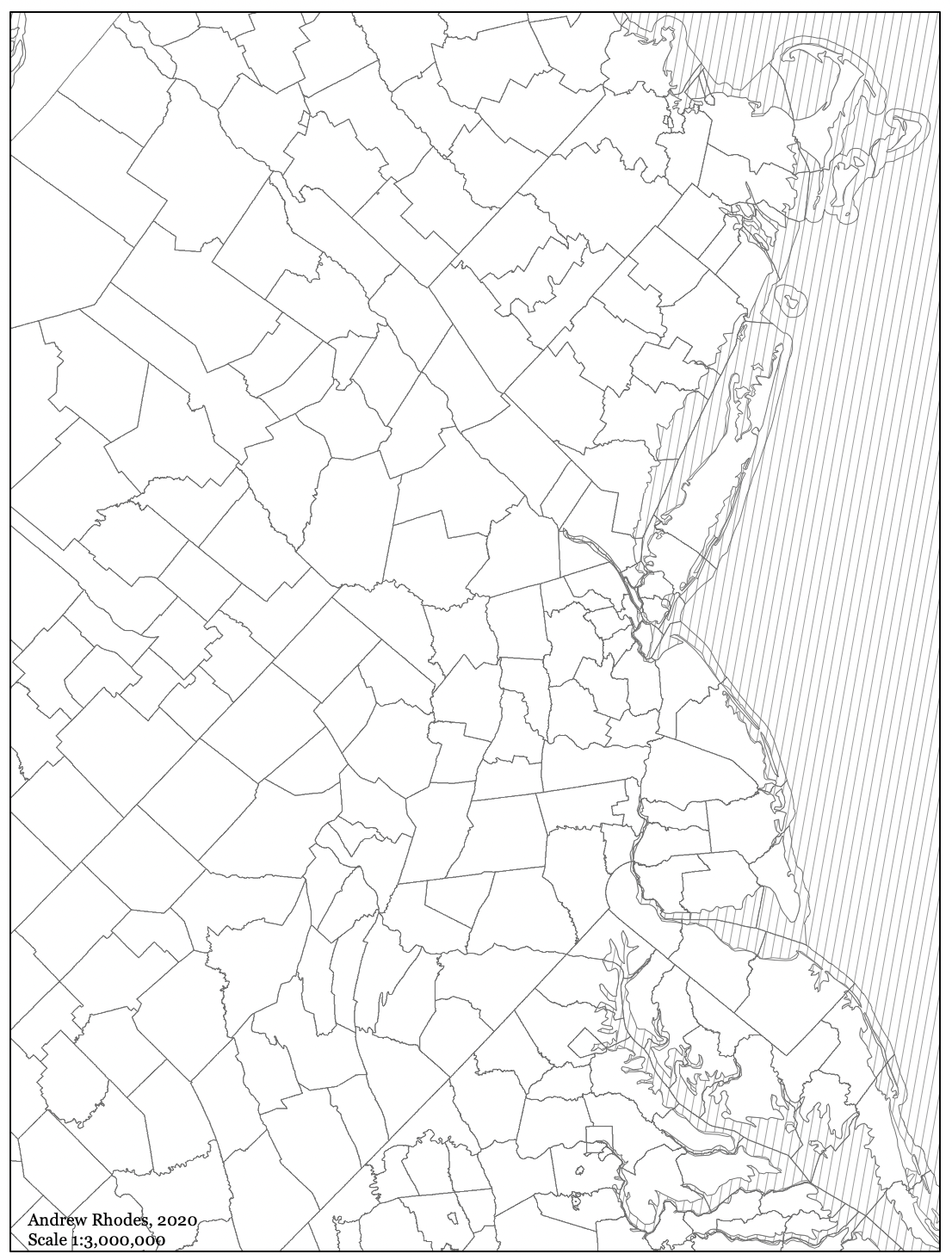

Andrew Rhodes, “Thinking in Space: The Role of Geography in National Security Decision-Making,” Texas National Security Review 2.4 (November 2019): 90-108.

Click here to read a French-language summary and analysis of this article.

Being able to “think in space” is a crucial tool for decision-makers, but one that is often deemphasized. In order to improve its ability to think in space, the national security community ought to objectively assess how effectively it is employing geographic information and seek every opportunity to sharpen its skills in this area.

Only statesmen who can do their political and strategic thinking in terms of a round earth and a three-dimensional warfare can save their countries from being outmaneuvered on distant flanks.

-Nicholas Spykman

Leaders who fail to think in space do so at their own peril. Nicholas Spykman published the above warning on the importance of mental maps in the context of World War II and the global challenges it presented, but his argument regarding the importance of spatial thinking to the nation’s security has never been more relevant. Thinking in space has long been an essential tool for thinking critically and communicating clearly when it comes to national security decision-making. The importance of mental maps and geographic communication are only growing in an era of new global challenges and renewed great power competition. Strategists and diplomats would benefit from gaining greater insight into the ways geographic information shapes national security decision-making. Moreover, understanding this impact can help produce recommendations for how American strategists can more effectively think in space.

The tools and resources needed to elevate the spatial thinking of those charged with conducting America’s foreign policy and securing the national interest are all available. Unfortunately, American strategists are currently not making full use of geographic information, inhibiting the policymaking process as well as the government’s ability to communicate global policy. Despite national security decision-makers having unprecedented access to geographic information and tools with which to visualize the world, this is not the golden age of spatial thinking in national security policymaking. The challenges confronting the national security community require learning new ways of spatial thinking — and relearning old ones — on a global scale.

The ability to “think in space” is more than mere navigation, map-reading, or geographic literacy. The basic assumptions laid out in Richard Neustadt and Ernest May’s classic study Thinking in Time, which explores how decision-makers can make better use of history, are germane to this type of thinking. The first assumption is that busy decision-makers and their advisers are presented with a tremendous quantity and diversity of information every day. Thus, when it comes to thinking in space, such individuals can consume only a small amount of the geographic information available to them. Second, the pressures of time and limited information do not lend themselves to thinking critically or, in the case of thinking in space, questioning the geographic renderings they are presented with. Third, it is nevertheless possible to achieve marginal improvements — in this case, in the use of geographic information — and be, as Neustadt and May put it, “more reflective and systematic.”

This article seeks to advance the conversation about how geographic information shapes national security decisions. While many have agreed with Spykman that “geography matters” and although there is a substantial literature on cartography as a form of communication, there has been little analysis of how geography “matters” when it comes to contemporary national security decision-making. This article begins by considering the position of national security decision-making at the intersection of the art and science of cartography and visualization, the unique cartographic consciousness of American strategists, and the various theories of geopolitics. These three elements are analogous to the three “images” Kenneth Waltz identified to discuss international relations: the individual, the national, and the global. In the sections that follow, I discuss the interaction of technology and geography, arguing that the ability of decision-makers to think critically in space has not kept pace with the advances of technology. The article then turns to the structure and process for employing geography in U.S. national security institutions and the importance of thinking in space in order to tackle 21st-century national security challenges. Finally, the article closes with recommendations for making the national security workforce more effective and identifies areas for further research. … …

Conclusion

Geographic analogies are powerful instruments, though they run the same risks of cognitive bias and shallow analysis as other simplifications, such as historical analogy. The shortcomings of historical analogy have been well studied by scholars who warn against the “tyranny of the past upon the imagination,” and the dangers awaiting those who “do not examine a variety of analogies before selecting the one that they believe sheds light on their situation.” The great military historian Michael Howard highlighted the dangers of overlapping analogies in both history and cartography, writing that historical battlefield maps, with “neat little blocks and arrows moving in a rational and orderly way…are an almost blasphemous travesty of the chaotic truth.”

Just as one ought not to depend on a single historical analogy, a senior official or policy analyst could constrain their thinking if relying on a single geographic perspective. Geography can be just as subjective as history, and those who desire to think more effectively in space should seek out multiple perspectives in the maps they study and their own mental maps. As mentioned above, Richard Edes Harrison argued that a critical first step is to dispense with persistent conventions that inhibit a “flexible view of geography,” such as always placing north at the top of the map. Harrison also wrote, in a wartime article co-authored by Robert Strausz-Hupé, that “the main pitfall to avoid is the continual use of one map, for the mind is inexorably conditioned to its shapes. It begins to look ‘right’ and all others ‘wrong.’” Take as an example a map of the Taiwan Strait rotated 55 degrees. Such a map will look “wrong” at first, but has the benefit of forcing the viewer to give fresh consideration to the key distances and geographic relationships.

Despite the pace of technological development and geopolitical shifts in the last two decades, the fundamental processes of national security institutions have changed remarkably little and are not conducive to the flexible view advocated by Harrison and Strausz-Hupé above. The bureaucratic circulatory system continues to rely on strategy documents, memos, email, briefings, and PowerPoint slides with anemic geographic content. The current distribution of cartographic capability and the standard forms of communication within the government are stagnant and may actively contribute to spatial de-skilling. Thus, the national security community needs to sharpen its understanding of the problem and consider different processes. There is limited data on questions of geographic literacy, trends in the use of geographic data, or the effectiveness of spatial thinking within the U.S. national security establishment. More research is needed to understand the institutional dimensions of how the U.S. government thinks in space, where the strengths and weakness are, what credible options for improvement exist, and what barriers inhibit their employment. Collection of such data would enable meaningful evaluation of how effectively the U.S. government’s geospatial tools and products support decision-makers and would undoubtedly suggest ways to improve the government’s use of geography and fix technical gaps and problems. Broad surveys of America’s national security institutions could not only identify any persistent holes in basic geographic knowledge but could also highlight conceptual strengths and weaknesses in employing the art and science of cartography. The findings of such investigations would provide valuable information to the civilian and military academic institutions of higher learning that shape future policymakers.

There is much work to be done in studying and improving the way the U.S. national security apparatus uses geography. However, another vital question for future scholars and analysts will be how America’s potential adversaries think in space. Succeeding in a long-term strategic competition requires a deep understanding of the thought processes, priorities, and blind spots of the other side. It is crucial to understand the persistent distortions that exist in an adversary’s world view, what inefficiencies endure in the ways they process new and ambiguous geographic information, and what cartographic messages resonate best with their national security system. But this will not be possible until the U.S. national security community improves its own ability to think in space.

Thinking in space is only one tool available to decision-makers and is no panacea to crafting successful strategies and avoiding tragic blunders. But more sophisticated geographic thinking and communication will sharpen national security decision-making and help decision-makers to better communicate their plans to the public. The national security community must be a learning and adaptive organization. It needs an objective evaluation of how effectively it is employing geographic information and it must seek every opportunity to sharpen its skills in order to think effectively in space.

***

Andrew J. Rhodes, “Thinking in Space: The Role of Geography in National Security Decision Making,” Defense Technical Information Center, Technical Report Accession Number: AD1069543, 1 February 2019.

Abstract: The ability to think in space is more than navigation, map-reading, or geographic literacy. Spatial reasoning is a key aspect of critical thinking and geography is a valuable tool for communicating critical thought. This study seeks to advance the conversation about how geographic information shapes operational and strategic decisions and how it sits at the junction of theories of geopolitics, the art and science of cartography and visualization, and the unique cartographic consciousness of the American national security establishment. The U.S. government is punching below its weight when it comes to the use of geographic information in strategic analysis, policy making processes, and its communication of global policy. The tools, resources, and imperatives are all at hand to elevate the spatial thinking of those charged with securing the national interest. This challenge promises to grow only more daunting in an era of great power competition that will require new spatial thinking and relearned old thinking on a global scale.

Descriptors: geopolitics, decision-making, geography, cartography, cognition, psychology, international relations, national security, treaties, international law, globalization

Subject categories: psychology, geography, government, and political science

A paper submitted to the faculty of the Naval War College in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the curriculum. The contents of this paper reflect the author’s own personal views and are not necessarily endorsed by the NWC, the Department of the Navy, or the U.S. Government.

Cover photo: White House Map Room circa 1943, Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

p. 67

… Chinese military modernization re-introduces old lessons about the tremendous extent of the Pacific theater. Preparing for a high-end conflict that emphasizes the air and maritime domain might require re-learning the cartography of the air-age globalism that took hold in the 1940s. If there is a map genre that captures the current strategic conversation on military competition with China, it is probably a map of overlapping Chinese missile range rings that has become increasingly common in the OSD annual reports to Congress on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and various products by defense think tanks like the Center for Strategic and

p. 68

Budgetary Assessments (CSBA).145 Invoking the “tyranny of distance” has become a standard talking point for officials highlighting the difficulties of rapid response and the importance of forward deployment and foreign partnerships in the Pacific. If China is the primary concern for force planners, they must have better mental maps of the Pacific and be prepared to make effective geographic cases to the national leadership, the American people, and key allies. Alfred Thayer Mahan in 1898, just after the Spanish-American War, wrote that the 3,500 nautical miles from Hawaii to Guam defined the “standard distance” at the heart of naval planning for the United States. Today that same 3,500 nm distance is a defining reality of the Pacific theater, but few American strategists fully appreciate the implications of that distance. Meaningful preparation for the challenges the United States faces in the Pacific will require a better intuitive understanding of the geography of the region and more sophisticated analysis of the spatial implications of the theater. … … …

p. 87

Techniques, Tactics, and Procedures for Geographic Staff Work

Aiding leadership through more sophisticated thinking in space cannot stop with a master’s degree or JPME certification. Adjustments to the institutional processes by which the national security bureaucracy provides geospatial resources to decision makers also offers opportunities. Some of the barriers to better use of geography are decidedly tactical and technical, and broader sharing of simple techniques and procedures could elevate the geographic game of the average staff officer.

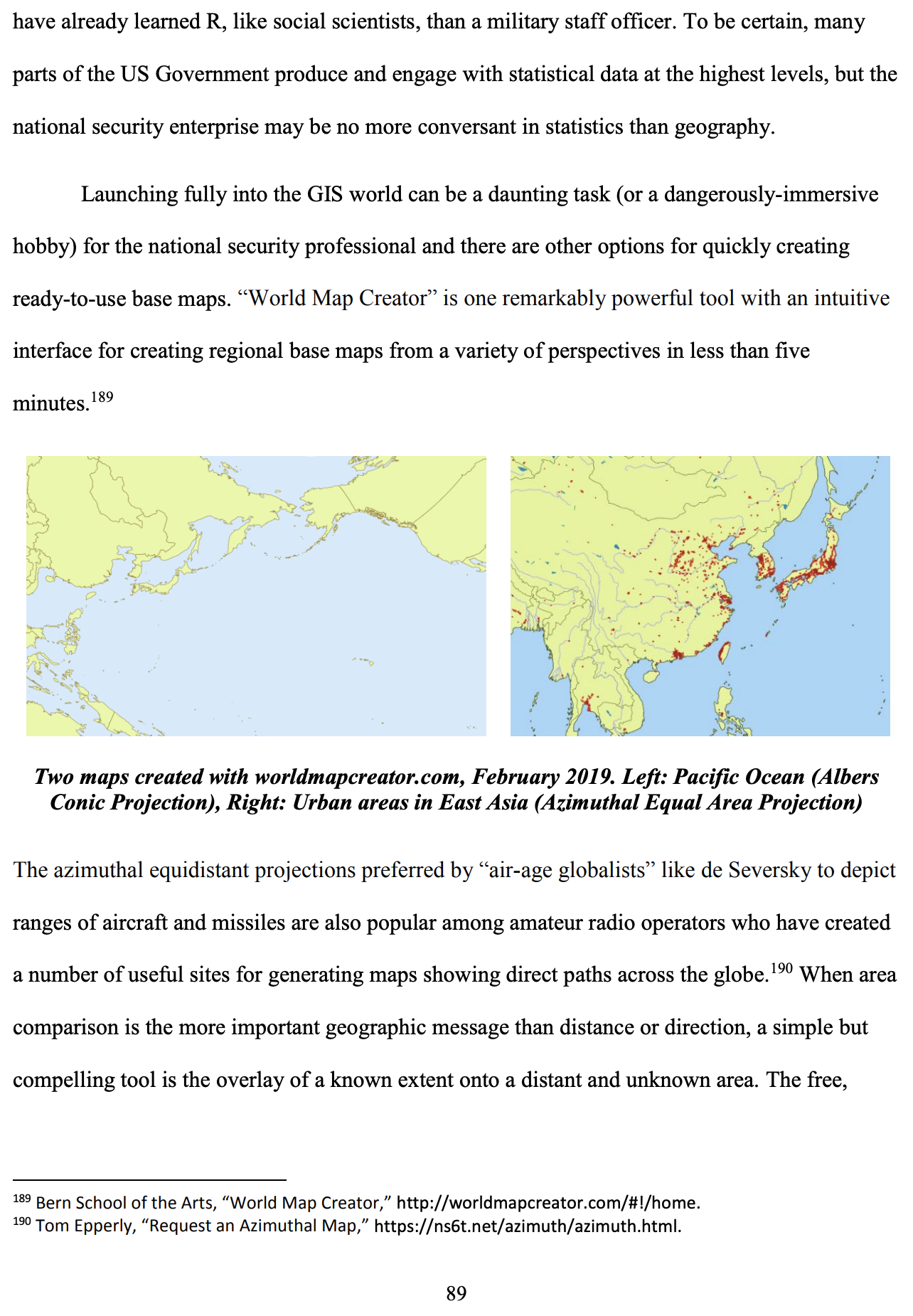

ArcGIS, produced by ESRI, is the overwhelmingly dominant GIS software suite, with a market share akin to that which PowerPoint enjoys among presentation software. The US Government is ESRI’s largest customer and ArcGIS licenses are widely available throughout different parts of the National Security Enterprise. Where licensing costs are prohibitive, the leading open-source alternative to ArcGIS, QGIS, can serve most conceivable geospatial

p. 88

analysis and cartography needs of a typical military officer or foreign policy generalist. The sophistication of software like ArcGIS and QGIS can present steep learning curves to novices and have capabilities in excess of the needs of those seeking to merely incorporate effective cartography into their communication. There are several other free and user-friendly options available for quickly generating base maps tailored to the purpose required. The ArcGIS online portal provides basic GIS services and a library of base maps in different styles, with more powerful services available through subscription.184 The “Natural Earth” project, sponsored by a consortium including the North American Cartographic Information Society, provides an extensive set of well-curated public domain data for use in map making.185 The cartographer Cynthia Brewer, who has published several practical guides to effective cartographic design, also maintains a website for effective and reliably-reproduced color schemes that can quite literally help the amateur cartographer or designer to “paint by numbers.”186 Within the space of an hour or two, and at no cost, a reasonably skilled computer user can learn to create custom maps, choosing among appropriate projections in QGIS and layering data from Natural Earth.187

Grant McDermott, an economist, has argued against GIS software for thematic mapping in favor of the statistical package R, which can interface with many of the same open-source GIS software behind QGIS.188 McDermott has developed materials to learn these techniques and is working on a book on the topic, but the argument in favor of R is more compelling for those who

p. 89

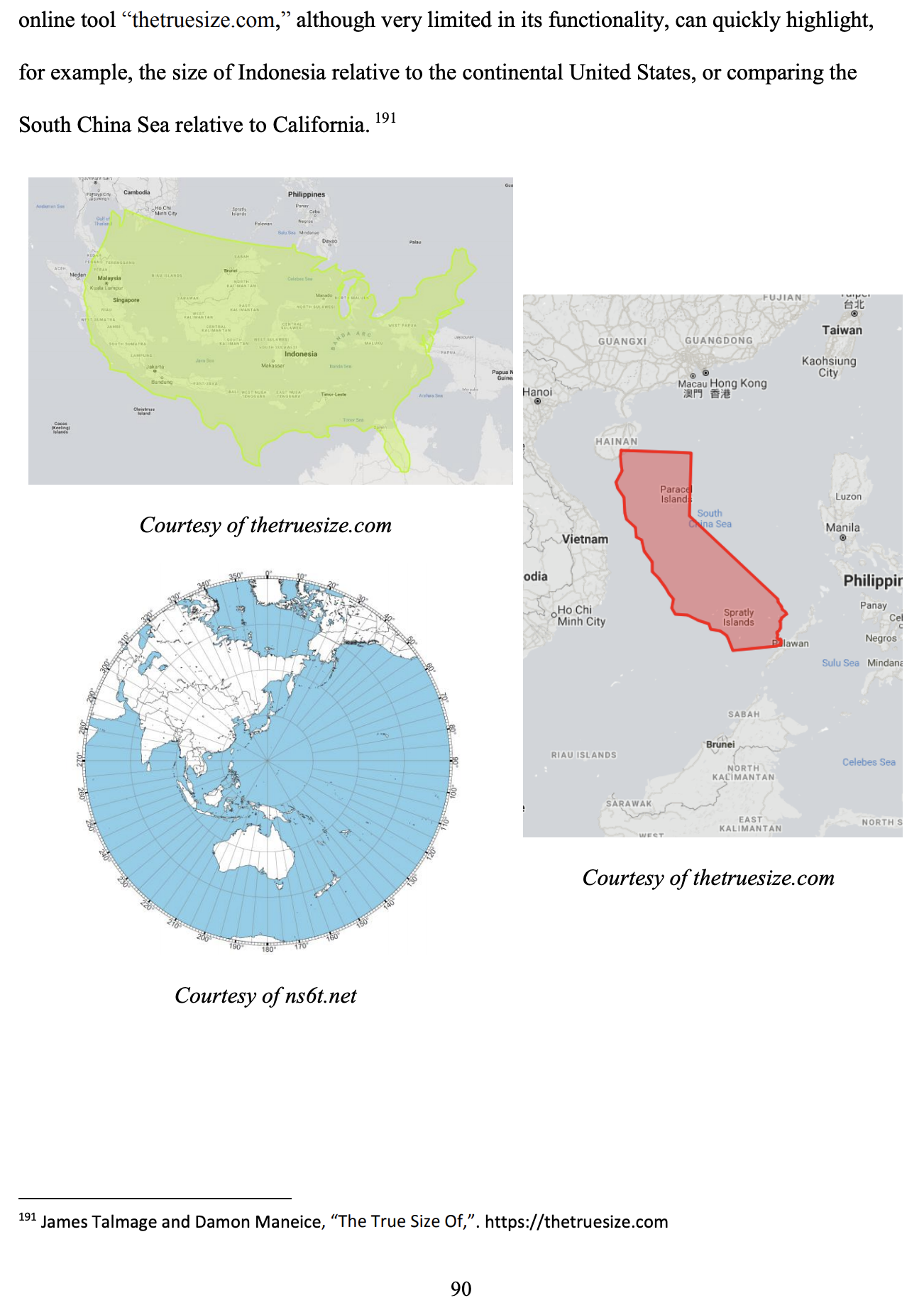

p. 90

***