Interviewed by Gordon Arthur, Shephard Media’s Asia-Pacific Editor: “Moving towards Mare Nostrum”

Great to speak with Gordon Arthur for his latest piece! I long enjoyed catching up with “King Arthur” and fellow defense journalists at the Zhuhai Airshow, and really miss those days! But now we continue our tracking of PLA developments by other open source means—and here you can read about the latest PRC military maritime numbers and my key points—what it all means and what the U.S. and its Indo-Pacific Allies and Partners need to do now… yes, NOW!

Gordon Arthur, Asia-Pacific Editor, “Moving towards Mare Nostrum,” Shephard Media, 12 November 2021.

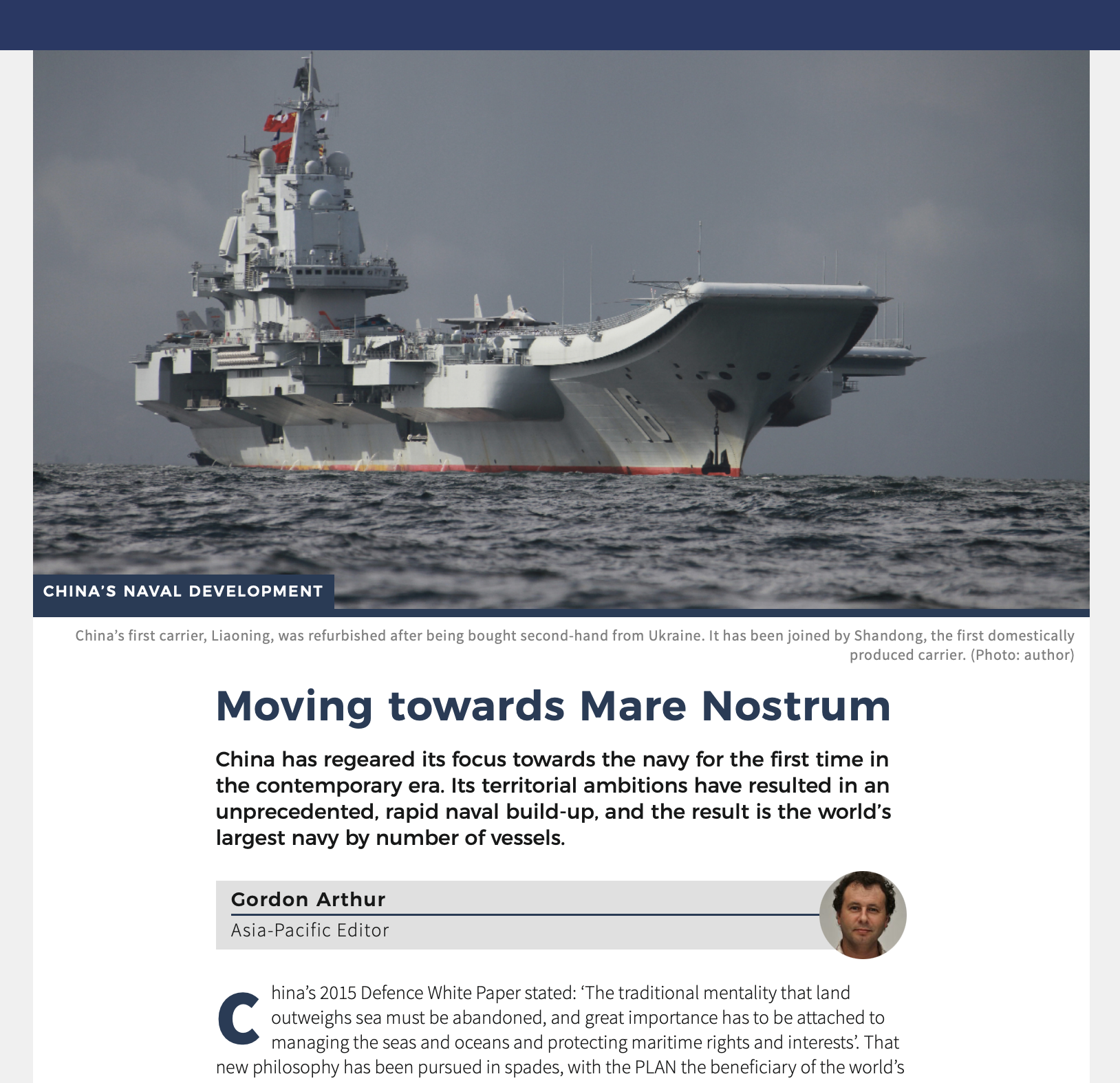

China has regeared its focus towards the navy for the first time in the contemporary era. Its territorial ambitions have resulted in an unprecedented, rapid naval build-up, and the result is the world’s largest navy by number of vessels. …

Chinese naval strategy

Andrew Erickson, professor of strategy at the US Naval War College, told Shephard: ‘The PLAN’s strategy has evolved over four historic phases, with greater responsibilities in each new phase adding a new layer beyond the previous core. While “near-seas active defence” still retains priority, China, since 2004, has added a “far-seas operations” strategy to address its increasing reliance on marine shipping to transport oil, gas and other strategic inputs to China, and products of its factories to customers overseas, as well as to protect other growing overseas interests.’

In fact, Ryan Martinson, Erickson’s colleague, has discerned an emerging new strategic layer in the PLAN. These are now near-seas defence, far-seas protection, global oceanic presence and expansion into the two poles. These radiating layers of strategy have driven increases in payload weight and ship size.

Erickson added: ‘This far-reaching emphasis, in turn, has been driving improved deep-water ASW, precision strike capabilities and aircraft carrier operations. In recent years, Xi Jinping – China’s most powerful leader since Mao and first-ever navalist leader – has called on the PLAN to become a “world-class navy”. In April 2018, he proclaimed: “The task of building a big and powerful people’s navy has never been as urgent as it is today.” Chinese naval strategy has further evolved in order to fulfil the paramount leader’s unprecedented strategic ambitions.’

Erickson pointed out: ‘Ships are the ultimate embodiment of naval strategy. China has the most far-reaching, clearly defined grand strategy of any great power today, with ambitious goals for 2035 and 2049, including achieving control over disputed sovereignty claims, particularly Taiwan. A determined, consistent strategy, funding and technology approach has enabled China’s shipbuilding industry to send an increasingly impressive juggernaut to sea: the world’s largest navy, coastguard and maritime militia by the number of ships.’ …

Erickson elaborated on how China achieved such success. ‘This approach has permitted China to thrive as a “fast follower”, pursuing a just-good-enough approach by exploiting foreign R&D through a process of imitative innovation. Here it seeks, finds, evaluates and adapts systems and processes through spiral development and integrated military and civilian ship production, as part of a larger national focus on military-civil fusion.’

The American academic pointed out that, unlike the US, the focus of Chinese shipyard production has been merchant ships for foreign customers. This allows the world’s largest commercial shipbuilding sector to subsidise Chinese naval shipbuilding, in part by employing a hybrid civil-military production standard that enables efficient transfer of shipbuilding personnel between civilian and military production.

Additionally, ‘contrary to the popular perception that China constructs ships faster, akin to “dumping dumplings into the soup”, on a ship-by-ship basis it may actually be slightly slower in production and fitting-out. Rather, China uses its world-leading shipyard scale, capacity and new-build layout efficiency to build more ships simultaneously than any other country today.’

Beyond the navy, the powerful China Coast Guard (CCG), which is now under direct Central Military Commission control, and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) must also be taken into account.

Erickson explained: ‘In keeping with a strict hierarchy of Chinese security priorities, Beijing’s near-seas active defence strategy has remained at the core of its security efforts since 1985. That is no accident: all unresolved Chinese island/feature and maritime claims lie within the near seas (Yellow, East and South China Seas). Within these top-priority waters, all three Chinese sea forces are focused and have key roles to play in close coordination with each other. The fact that most CCG assets, and virtually all PAFMM assets, are deployed within these three seas frees up the PLAN to focus an increasing proportion of its assets beyond.’

Indeed, larger CCG assets may play a growing role farther afield as a second line of maritime effort behind PLAN operations. The CCG had 255 vessels last year, for example.

However, China cannot sustain such a shipbuilding scale indefinitely. Erickson noted: ‘Nearby, near-term progress doesn’t transfer well across space or time. Indeed, China may have already reached its peak growth rate and mobilisation ability. Looking forward, Chinese naval shipbuilding is slowing down and faces mounting maintenance and overhaul requirements.’ … …

Sinking the competition

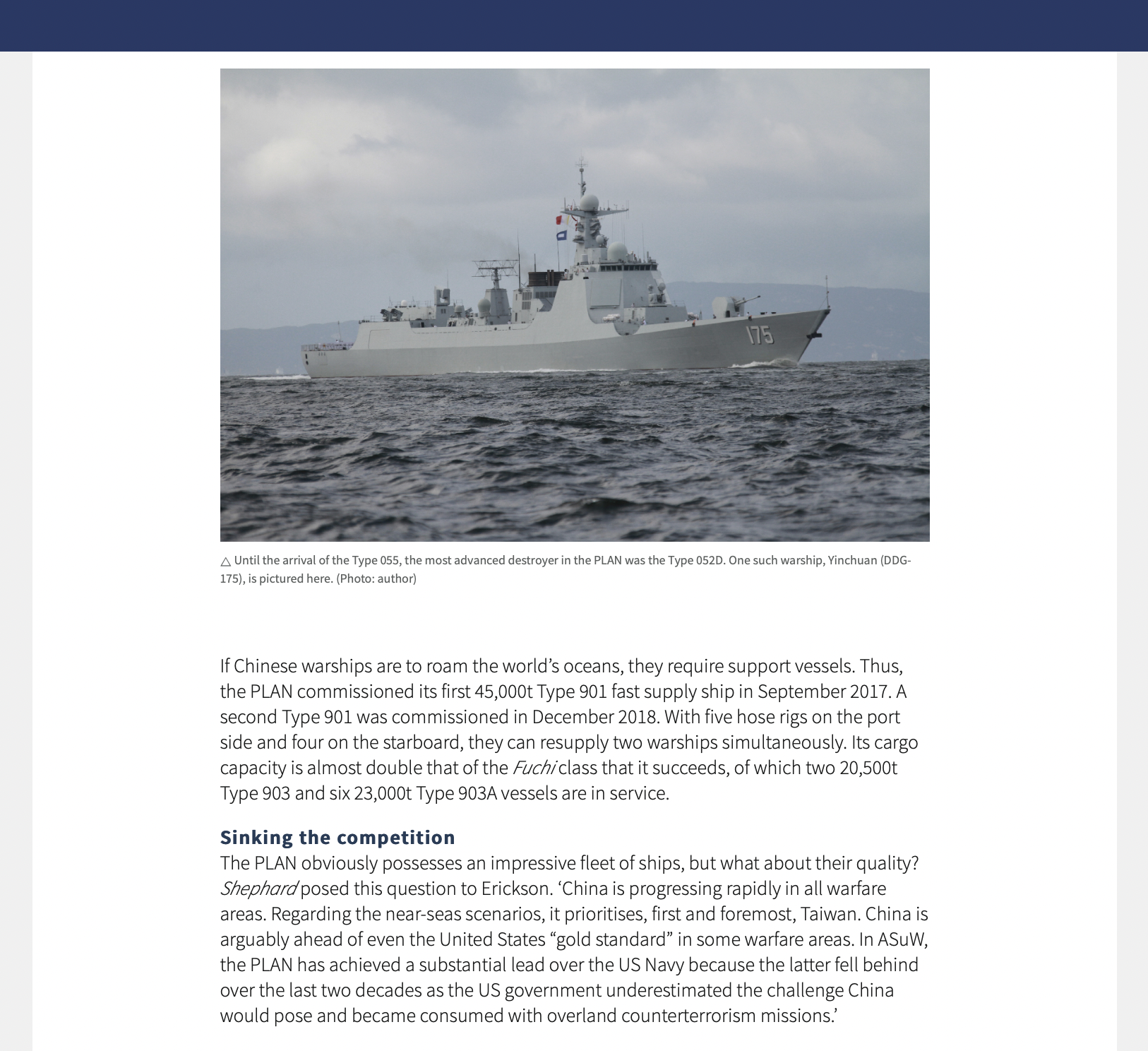

The PLAN obviously possesses an impressive fleet of ships, but what about their quality? Shephard posed this question to Erickson. ‘China is progressing rapidly in all warfare areas. Regarding the near-seas scenarios, it prioritises, first and foremost, Taiwan. China is arguably ahead of even the United States “gold standard” in some warfare areas. In ASuW, the PLAN has achieved a substantial lead over the US Navy because the latter fell behind over the last two decades as the US government underestimated the challenge China would pose and became consumed with overland counterterrorism missions.’

He elaborated: ‘Most PLAN ships boast advanced missiles, and loadouts now include supersonic missiles. Both China and the US face challenging limitations in mine warfare because it’s inherently hard to do. On balance, however, the combination of China’s commitment to building dedicated assets and its home-court advantage puts China ahead.

‘In strike, the two navies’ capabilities are currently similar, and China’s continue to improve. The PLAN already deploys potent cruise missiles, with the DH-10 akin to a Tomahawk, and it may start deploying ballistic missiles on aircraft and surface ships. In air defence/anti-air warfare, the US Navy retains a modest lead if SM-6 is factored into the equation (beyond the SM-2, which is more similar in capability). In ASW, particularly open-water ASW away from shallow-water detection systems proximate to China itself, the US retains a major advantage. This is based on the substantial American lead in undersea warfare, particularly submarines.’ …

Erickson offered his analysis of the relative strengths and weaknesses of the PLAN too. ‘The PLA generally, and the PLAN specifically, pursues proximate military priorities with disproportionate success and potential. Over the past two decades, the PLA has achieved a rapid hardware build-out in quantity and increasing quality, together with sweeping reforms to address ongoing weaknesses in organisation, coordination, sophistication and training.

‘China has already arrived as a great power. It has the world’s second-largest economy and defence budget, and the world’s largest standing ground force. Its three sea forces are each world’s largest by a number of ships. It has the Indo-Pacific’s largest air force, the world’s largest sub-strategic missile force and arguably the world’s largest and most sophisticated surface-to-air missile force.

‘In some measures of shipbuilding, land-based ballistic/cruise missiles and integrated air defence systems, it has even surpassed the United States in overall capacity. Chinese sources display confidence that its naval shipbuilding has advantages over its American counterpart,’ Erickson assessed.

The time is now

Shephard asked Erickson just how alarmed he is by the formidable rise of the PLAN. He said that ‘China’s rapid naval ramp-up, while in itself highly worrisome, is part of a far broader concern. The “decade of greatest danger” is already upon us; the US and its allies and partners must weather the “window of vulnerability”. Conflict may be avoidable but not friction and crises.’

He warned that a ‘climax is likely to erupt before 2030 – at the apogee of Xi, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and China’s relative power – in the form of the maximum threat of a kinetic conflict over Taiwan… Here, US and allied success, or failure, will be fundamental and reverberate for the remainder of the century.’

As indicated earlier, we are now in what Erickson calls the Decade of Danger. He forewarned: ‘Given the ambitious goals of Xi, the CCP he leads and the China they control, their default impulse will be to make a major move against Taiwan by the late 2020s – following an extraordinary ramp-up in PLA capabilities, and before the power and grasp of Xi or the party-state has ebbed, or Washington and its allies have fully regrouped and rallied to the challenge.’

The US Naval War College professor advised: ‘Only the most formidable, agile American and allied deterrence can kick the can down the road long enough for a China slowdown to close the “window of vulnerability”. Truly dramatic revelations of world-class PLA progress and selective superiority over the next few years will shock and awe citizens and influencers in Taiwan, America’s allies and America itself. Recent public revelations about a paradigm-shifting build-up of nuclear weapons and associated hardening and delivery systems – in extreme contrast to prior Chinese history, doctrine and messaging – are but one manifestation of this sudden, sweeping and startling build-up.’

Amongst other things, he was referring to the discovery of at least three enormous fields of missile siloes under construction deep in China, which could host more than 250 DF-41 intercontinental ballistic missiles if each were filled.

‘Only well-prepared and well-explained US government answers will stem a riptide of stunned defeatism and prevent Xi from “winning without fighting”. “Holding the line” is likely to require frequent and sustained proactive enforcement actions to disincentivise full-frontal Chinese assaults on the rules-based order in the Asia-Pacific. Chinese probing behaviour and provocations must be met with a range of symmetric and asymmetric responses that impose real costs,’ Erickson urged in no uncertain terms.