Getting Synergized? PLAN-CCG Cooperation in the Maritime Gray Zone

Don’t miss the latest Martinson masterpiece: Pathbreaking analysis in Asian Security on coordination between China’s Navy and Coast Guard in “gray zones” at sea! Reveals both substantial improvements and lingering limitations… Prof. Ryan Martinson’s cutting-edge insights offer a unique “feel” for precise PRC capabilities, shortfalls & trends… an analytical x-factor that’s all-too-hard to come by!

Ryan D. Martinson, “Getting Synergized? PLAN-CCG Cooperation in the Maritime Gray Zone,” Asian Security (27 November 2021).

Professor Ryan D. Martinson is a researcher in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the Naval War College. He holds a master’s degree from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and a bachelor’s of science from Union College. Martinson has also studied at Fudan University, the Beijing Language and Culture University, and the Hopkins-Nanjing Center.

ABSTRACT

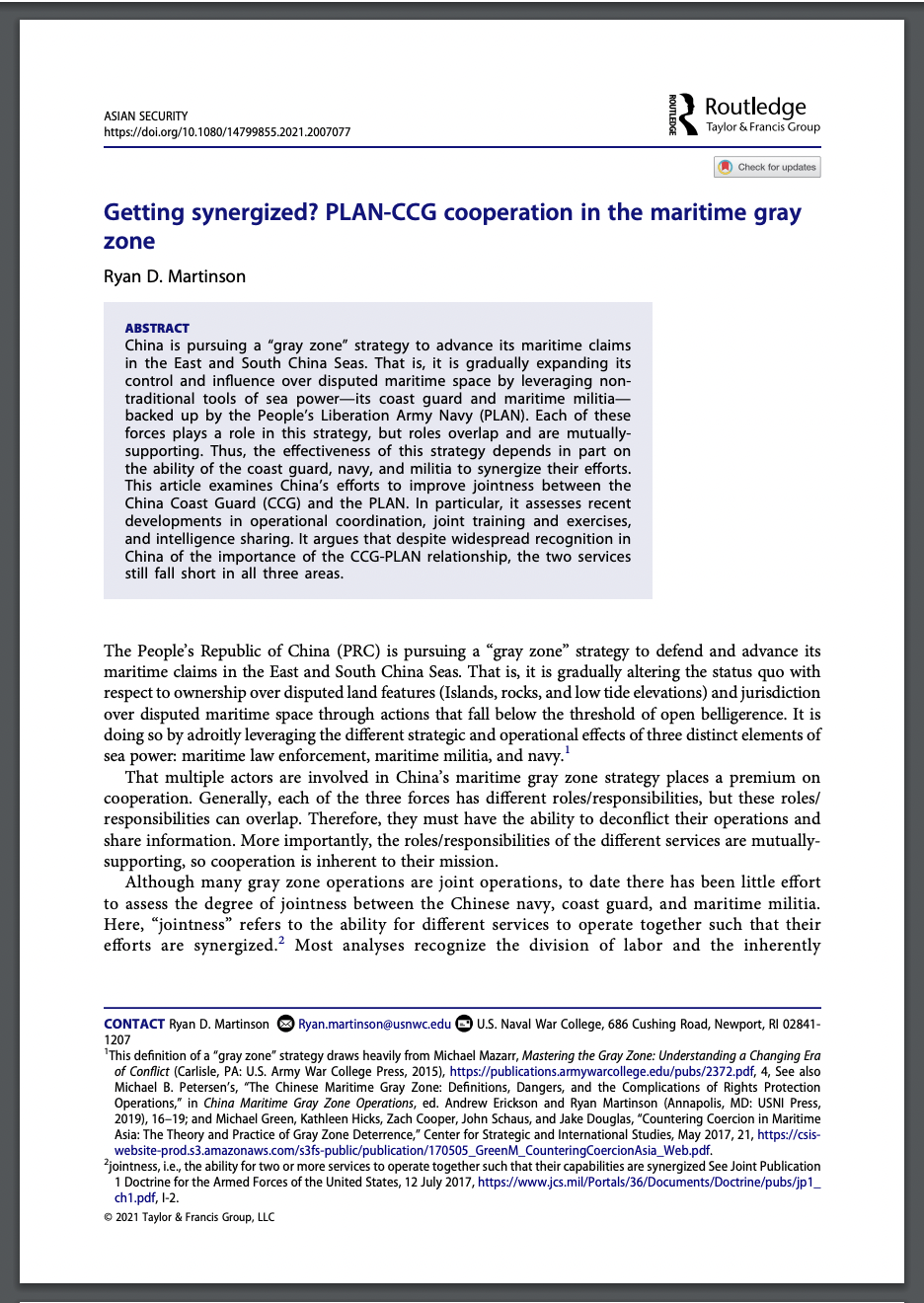

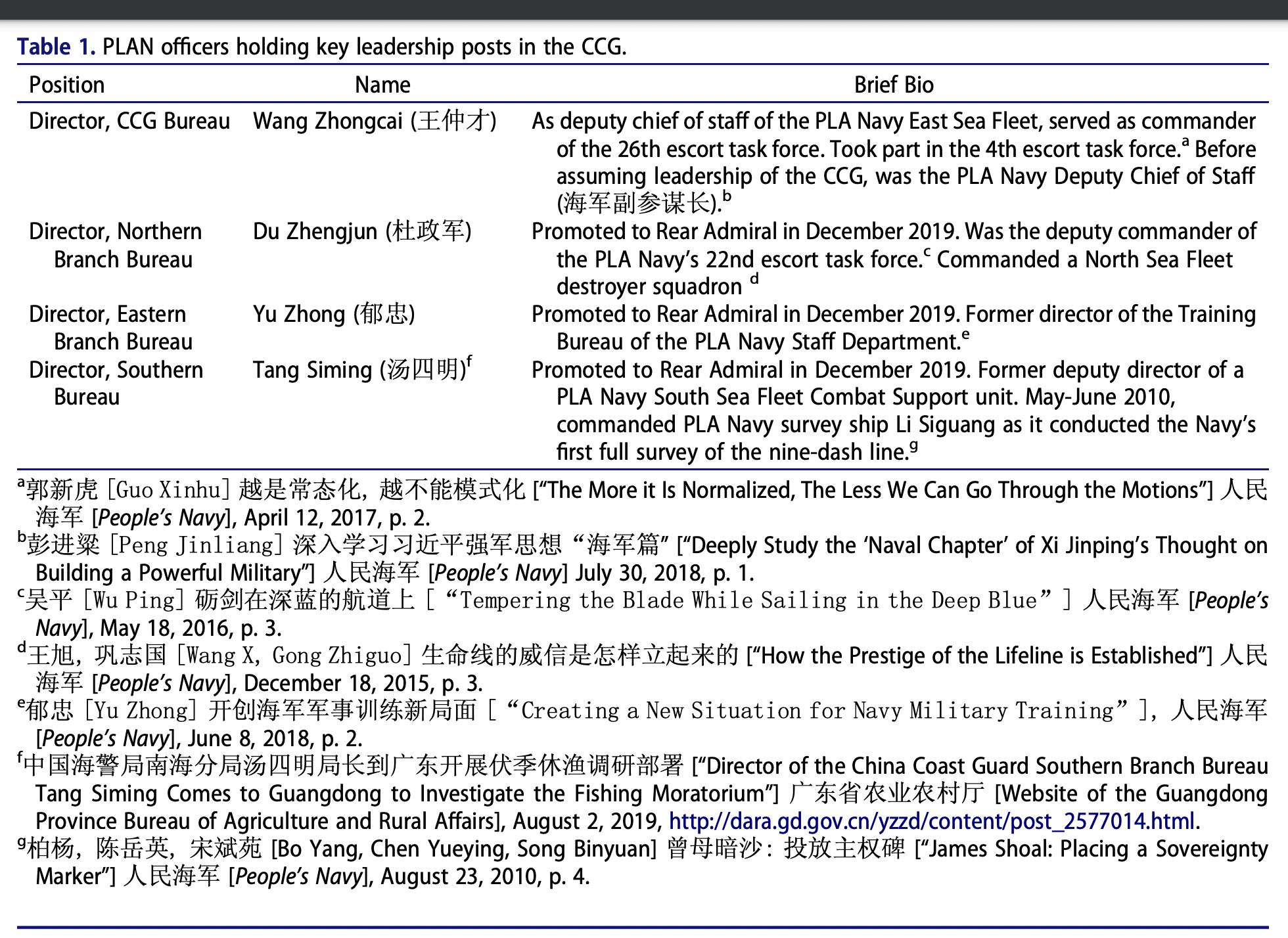

China is pursuing a “gray zone” strategy to advance its maritime claims in the East and South China Seas. That is, it is gradually expanding its control and influence over disputed maritime space by leveraging nontraditional tools of sea power—its coast guard and maritime militia—backed up by the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). Each of these forces plays a role in this strategy, but roles overlap and are mutually-supporting. Thus, the effectiveness of this strategy depends in part on the ability of the coast guard, navy, and militia to synergize their efforts. This article examines China’s efforts to improve jointness between the China Coast Guard (CCG) and the PLAN. In particular, it assesses recent developments in operational coordination, joint training and exercises, and intelligence sharing. It argues that despite widespread recognition in China of the importance of the CCG-PLAN relationship, the two services still fall short in all three areas.

TEXT (SELECTED)

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is pursuing a “gray zone” strategy to defend and advance its maritime claims in the East and South China Seas. That is, it is gradually altering the status quo with respect to ownership over disputed land features (Islands, rocks, and low tide elevations) and jurisdiction over disputed maritime space through actions that fall below the threshold of open belligerence. It is doing so by adroitly leveraging the different strategic and operational effects of three distinct elements of sea power: maritime law enforcement, maritime militia, and navy.1

That multiple actors are involved in China’s maritime gray zone strategy places a premium on cooperation. Generally, each of the three forces has different roles/responsibilities, but these roles/ responsibilities can overlap. Therefore, they must have the ability to deconflict their operations and share information. More importantly, the roles/responsibilities of the different services are mutually-supporting, so cooperation is inherent to their mission.

Although many gray zone operations are joint operations, to date there has been little effort to assess the degree of jointness between the Chinese navy, coast guard, and maritime militia. Here, “jointness” refers to the ability for different services to operate together such that their efforts are synergized.2 Most analyses recognize the division of labor and the inherently cooperative nature of China’s gray zone operations, but very few studies have examined how effectively this division of labor is implemented and how efficiently the three services cooperate.3

This paper seeks to contribute to this neglected area of scholarship, focusing in particular on the vital coast guard-navy relationship. In particular, it examines coast guard-navy jointness in three essential respects: 1) operational coordination, 2) joint training and exercises, and 2) intelligence sharing. It argues that despite a widespread recognition of the need to improve coast guard-navy jointness, relations between the two services remain fairly weak.

It comprises six parts. Part 1 briefly outlines the division of labor in China’s gray zone strategy. Part 2 discusses recent organizational changes that have impacted coast guard-navy relations. Parts 3, 4, and 5 assess coast guard-navy jointness in operational coordination, force development (training/exercises), and intelligence sharing. The paper concludes with a summary of key findings.

Division of Labor in the Gray Zone

China’s maritime gray zone operations rely on a division of labor between the country’s three maritime forces. The coast guard and the maritime militia are generally engaged in the most provocative “rights protection” operations, i.e., actions to defend and advance China’s maritime claims. This, Chinese strategists believe, gives Beijing more leeway to act assertively without the risk of armed conflict or severely harming its reputation.4 White-hulled coast guard cutters are seen as less menacing than modern naval combatants. Moreover, given that they are more lightly armed than naval combatants, the consequences of an inadvertent armed clash are less potentially catastrophic.5

China’s maritime militia is a component of China’s armed forces directly commanded by the PLA. Members of the maritime militia are often disguised as civilian mariners, especially fishermen, allowing for robust actions with a low risk of military escalation and surreptitious intelligence collection. While they serve many of the same “rights protection” functions as the coast guard, they have no formal law enforcement authority; their intentionally ambiguous status allows Beijing to downplay its role in directing their actions. Militia-PLAN cooperation is an important and understudied topic, but it is beyond the scope of this paper.6

Operating on the front lines of China’s gray zone strategy, the coast guard and militia perform three major “rights protection” missions. First, they maintain presence in “Chinese” waters to physically represent Beijing’s maritime claims. Second, where and when directed, they prevent foreign vessels from using Chinese-claimed space for military, scientific, or economic purposes. They do this by demanding the foreign mariners cease operations or accept the consequences of noncompliance, which can include being subjected to non-lethal force such as high-powered water cannons, bumping, or ramming. Third, they ensure the security of Chinese civilian mariners (fishermen, scientists, oil/gas exploration units, etc.) operating in Chinese-claimed maritime space. They come to their aid if they are threatened and, if the risk is serious enough, escort them as they operate in harm’s way. Here, the coast guard and militia’s main tactic is to place their vessels in between the civilian vessel and any would-be attackers. Regardless of the primary mission, the coast guard and militia are charged with collecting intelligence on foreign civilian and military activities.7

Although the Chinese coast guard and – to a lesser extent – the maritime militia are the chief actors in China’s maritime gray zone strategy, they are not alone. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) also performs a number of important roles. It may directly engage foreign civilian mariners acting in violation of Chinese claims, serving an essentially law enforcement function. However, they do so only if and when the Chinese coast guard unavailable.8 In the past, PLAN forces have evicted Vietnamese fishers from the Paracels and Philippine fishers from Spratly waters.9 Moreover, like the coast guard and militia, PLAN warships sometimes conduct symbolic actions to declare Chinese sovereignty over disputed land and sea. For example, PLAN warships hold ceremonies at the James Shoal, a fully submerged feature marking the southernmost point of Chinese-claimed territory.10

More generally, however, the PLAN’s gray zone role is supportive. It serves as a “backstop” (后盾) for China’s front line forces. That is, it maintains readiness to come to the aid of the Chinese coast guard and militia should a dispute escalate to hostilities. This readiness also serves to deter foreign leaders, both at sea and on shore, from taking provocative actions, lest they precipitate an armed conflict they do not want. Lastly, the PLA also leverages its air-, sea-, shore-, and space-based sensors to provide intelligence support to the coast guard and militia.

While multiple PLA services can and do provide these supportive functions, none is as important as the PLAN. During times of tension or crisis, PLAN ships can operate near the trouble spot for long periods of time, prepared to rapidly come to the aid of the coast guard and militia if the situation escalates. Warships are also best equipped to perform what Edward Luttwak has called “ active naval suasion.”11 That is, their presence can communicate China’s will to assert its prerogatives, in the hope of deterring them from taking actions – or compel them to cease actions – inimical to Chinese interests. The nature and duration of this presence can send sophisticated signals to foreign states, both to the victims of PRC coercion and those who would consider coming to their aid.

The division of labor between the coast guard, militia, and navy also depends on which class of foreign ship or personnel are involved. In the case of foreign civilians or maritime law enforcement, the Chinese coast guard and militia take the lead. But the PLAN appears to be charged with handling intrusions by foreign surface combatants into waters adjacent to Chinese claimed features, as it is PLAN warships that are often seen trailing U.S. Navy ships operating in the South China Sea, especially when they approach Chinese-occupied land features.12 The task of tracking foreign naval survey and surveillance vessels sometimes falls on the PLAN and sometimes on China’s maritime law enforcement forces.13 … … …

Conclusion

The PLAN serves several important functions in China’s maritime gray zone strategy. Where and when needed, it directly engages foreign civilian mariners found violating Chinese laws and regulations in Chinese-claimed maritime space. Moreover, it tracks and monitors foreign naval vessels operating in “Chinese” waters, including, at least in some cases, survey and surveillance vessels operated by foreign navies. The PLAN also provides “support and cover” to the coast guard. That is, it operates nearby, ready to come to its aid if interactions with foreign forces escalate to armed conflict. This presence is also intended to influence the strategic calculus of foreign decision makers at sea and on shore, by demonstrating Beijing’s will to use force if needed. Lastly, the PLAN provides intelligence to the coast guard and the militia.

The joint nature of China’s maritime gray zone strategy requires that the PLAN be able to operate effectively with the Chinese coast guard, the primary force charged with enforcing China’s maritime claims in peacetime. How effective is inter-service cooperation?

Eight years since the CCG reform began and six years since the PLA reform began, it appears that the two services have not yet forged a close and highly effective partnership. Interoperability is likely weak. The author found very few instances of joint PLAN-CCG joint exercises intended to boost coordination in maritime rights protection operations. Of particular note, there have been very few instances since 2016.

Moreover, while the CCG and the PLAN have likely established mechanisms for coordinating operations in the Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea, the two services have not implemented a system for unifying command ashore. This makes sense, as the CCG is not a part of the PLA theater command system. On the other hand, the PLAN and the CCG are pioneering different command arrangements for forces at sea. In May 2018, the first joint PLAN, CCG, and local law enforcement patrol occurred in the Paracels, with the joint task force operating according to explicit command relationships.

Lastly, there are few indications that intelligence sharing has improved significantly since 2013. CCG command centers and front line forces likely do not have access to the PLA common operational picture. When intelligence is shared, it is probably situational.

These findings strongly suggest that China’s maritime gray zone strategy is not as potent as it might be, given the size and strength of the sea services individually. This is an important corrective to any tendency to inflate the effectiveness of China’s approach to sovereignty enforcement in the East and South China Seas. Of course, these findings also imply that China’s ability to use its sea services to assert control over maritime space could significantly improve if the CCG and the PLAN are able to overcome the challenges described above. Therefore, other disputants should carefully track future developments in these three areas. The findings of this article also suggest some likely causes for suboptimal cooperation between these two services.

The PLAN is still engrossed in the larger PLA reform, which has prioritized efforts to build joint operational capabilities within the PLA. For its part, the CCG too is in the midst of a major effort to integrate personnel from four different maritime law enforcement agencies. This clearly takes precedence over boosting interoperability with the PLAN. Additionally, now that the CCG is no longer part of the State Oceanic Administration, there is less incentive for the PLAN to establish close organizational ties with the CCG. In the past, State Oceanic Administration could provide oceanographic and meteorological services to the PLAN, which it desperately needed as it began to operate beyond East Asia. Mutual need was the basis for two cooperative agreements, one signed in 2009 and one in 2017, ensuring PLAN support for CMS and, later, the CCG. The PAP likely has much less to offer the PLAN and is probably not seen as an attractive partner. Lastly, it has been several years since the last maritime gray zone crisis. The 2014 HYSY-981 incident prompted at least two major joint exercises to boost interoperability in the defense of a Chinese drilling rig. But there has been no incident of similar intensity in the years since. Meanwhile, the CCG has grown far more powerful and less dependent on the PLAN, especially in the South China Sea. Thus, the two services probably feel less urgency to strengthen cooperation.