The Paul Nantulya Bookshelf: Elucidating China-Africa Relations with Unique Insights

Paul Nantulya’s incisive work curates and analyzes revealing information on an array of important and timely but hitherto under-researched topics, following PRC activities across the continent that will contribute the vast majority of new people to the world during this century!

As a research associate at The Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Paul Nantulya researches and prepares written analysis on contemporary Africa security issues. Located at the U.S. National Defense University, The Africa Center is an academic institution within the Department of Defense established and funded by Congress for the study of security issues relating to Africa and serving as a forum for bilateral and multilateral research, communication, training, and exchange of ideas involving military and civilian participants.

Mr. Nantulya’s areas of expertise include Chinese foreign policy, China/Africa relations, African partnerships with Southeast Asian countries, mediation and peace processes, Africa’s Great Lakes region, and East and Southern Africa.

Prior to joining the Africa Center, Mr. Nantulya served as a regional technical advisor on South Sudan for Catholic Relief Services (CRS) from 2009 to 2011, where he supported crisis mitigation for the Government of South Sudan including writing policy analyses for the Ministry of Peace and Comprehensive Peace Agreement Implementation. In this role he worked closely with South Sudan’s external partners, particularly Japan’s International Cooperation Agency, on conflict prevention.

In 2005–09, Mr. Nantulya was CRS/Sudan’s governance manager in Juba. In this capacity he coordinated technical assistance for the Office of the President on establishing functional systems of state and local government. Mr. Nantulya previously worked for the South Africa-based Africa Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), coordinating ACCORD’s participation in the Tokyo International Conference on African Development, the preeminent forum for Japan/Africa relations. He also worked on civilian and military peacekeeping in the Southern African Development Community. Additionally, he was part of the ACCORD team that worked with President Nelson Mandela on the Arusha Peace Process on Burundi (1999–2001), President Thabo Mbeki and Deputy President Jacob Zuma on ceasefire talks (2001–03), President Ketumile Masire on the Inter-Congolese Dialogue (2002), and Dr. Nicholas Haysom on the Sudan peace process (2002–03).

Mr. Nantulya holds a B.A. in international relations from United States International University in Nairobi, Kenya, a Graduate Certificate in Japanese from the Japan Africa Interchange Institute in Nairobi, Kenya, and an M.S. in Defense and Strategic Studies from Missouri State University in Springfield, MO. He tweets at @PNantulya.

Areas of Expertise

Governance, mediation, peace processes, peacekeeping, East Africa

PUBLICATIONS

Paul Nantulya, “China’s Blended Approach to Security in Africa,” Italian Institute for International Political Studies, 29 July 2021.

2021 is a significant year for Africa-China relations. It marks 20 years since the Forum for China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) was established. China’s Communist Party, which has been in contact with African parties longer than any other political party in the industrialized world, turned 100. Meanwhile, South Africa’s African National Congress, one of the first African movements to be mentored by China, turned 109. The shared liberation movement contacts between China and Africa have been heavily invoked by both sides as the continent braces for the eighth FOCAC Summit, which will take place Senegal in September.

There will be a lot to discuss. FOCAC has evolved into more than a high-level summit. It has established numerous joint mechanisms for capacity building, technical support, and coordination, from local government and agriculture to law enforcement, security, and defense. China is not only Africa’s single largest trade partner and bilateral creditor; it also runs more exchanges for African politicians, civil servants, and professionals than any other country.

This also extends to military ties, which have grown overtime alongside China’s other engagements. China’s military strategy in Africa centers on cultivating personal and professional ties, diffusing norms and models, and forging ideological and political bonds of solidarity.

In fact, military exercises, port visits, and military training appear to play a minimal role. Moreover, the PLA does not deploy troops alongside African forces in the field. Numbers tell a part of the story. Professional and political exchanges constituted 90 percent of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) engagements in Africa between 2000 and 2016. This broke down to 13 joint military drills, 22 naval port calls, and 259 exchanges and dialogues, suggesting a much stronger emphasis on relationship-building and networking. Over 80 percent of these interactions were conducted with the militaries of the Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa (FLMSA) with whom China has particularly strong historical bonds.

This legacy of engagement dates back to 1950, a year after the People’s Republic of China was founded, when the PLA embarked on supporting Africa’s wars of independence. By 1955, when the Bandung Conference on Afro-Asian Solidarity was held, China was hosting African fighters at Nanjing Military Academy, the Fourth Department of Beijing’s Higher Military Institute (now the PLA’s National Defense University), and other schools. By 1958, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had trained over 3,000 fighters, received over 400 African delegations seeking weaponry, and stationed hundreds of military instructors in Africa. Between 1958 and 1961, China participated in the All-Africa Peoples Congresses in Accra, Tunis, and Cairo, the precursors of the Organization of African Unity (OAU, now African Union, or AU) which was tasked with decolonization. When it established its Liberation Committee in 1963 in Tanzania to coordinate the armed struggle, China became its main provider of arms, military trainers, and advisors. This continued until the fall of apartheid in 1994. … … …

***

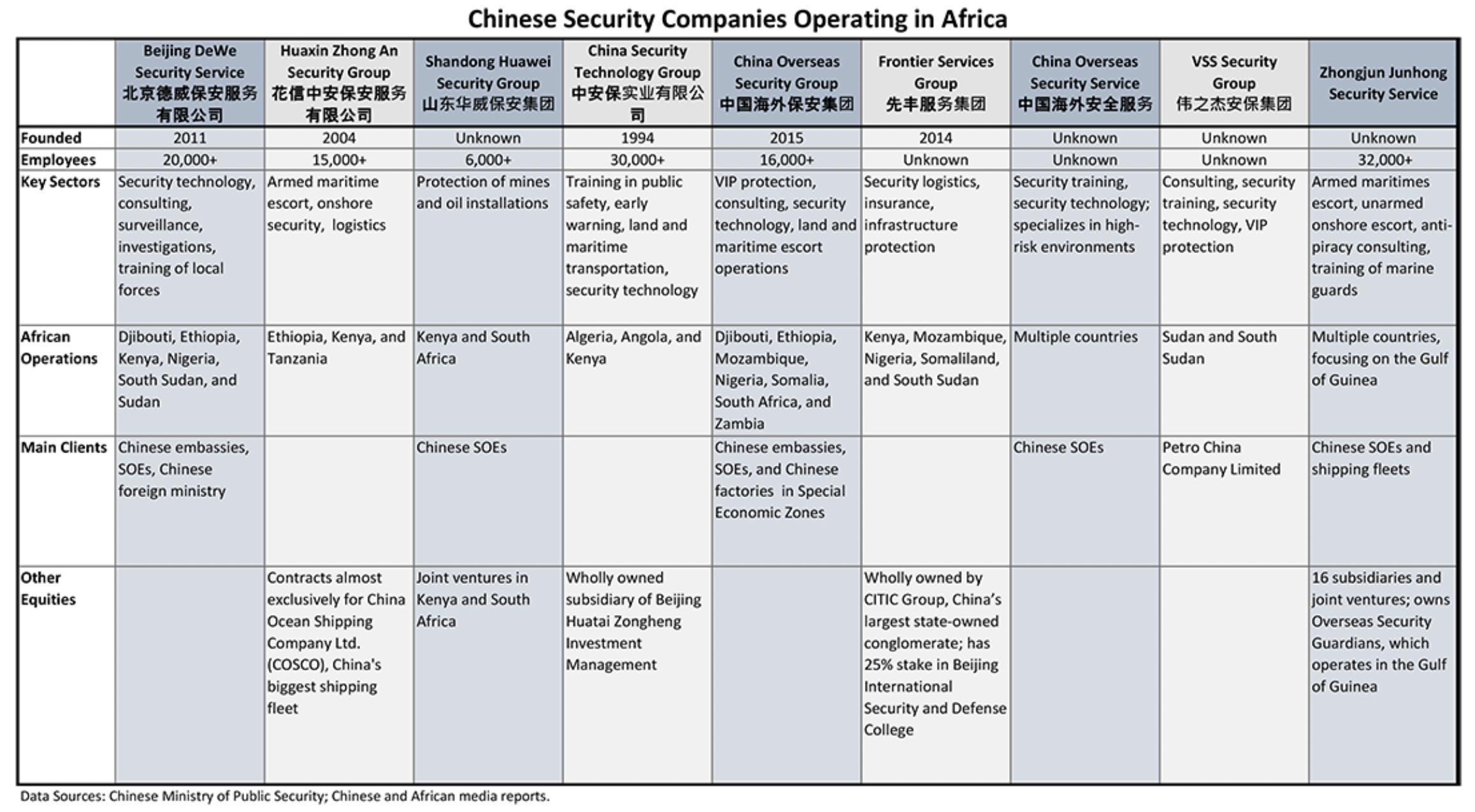

Paul Nantulya, “Chinese Security Firms Spread along the African Belt and Road,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 15 June 2021.

The deployment of Chinese security firms in Africa is expanding without a strong regulatory framework. This poses heightened risks to African citizens and raises fundamental questions over responsibility for security in Africa.

“A more robust regulatory process in Africa will be essential to prioritize and protect African citizen interests.”

Since 2012, over 200,000 Chinese workers relocated to Africa to work on China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR, yī dài, yī lù, 一带一路), commonly known as the Belt and Road Initiative, bringing the number of Chinese immigrants on the continent to 1 million. There are over 10,000 Chinese companies in Africa, including at least 2,000 state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Chinese SOEs have a major stake in African construction projects, generating over $40 billion in revenue annually.

The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences notes that 84 percent of China’s Belt and Road investments are in medium- to high-risk countries. Three hundred and fifty serious security incidents involving Chinese firms occurred between 2015 and 2017, from kidnappings and terror attacks to anti-Chinese violence, according to China’s Ministry of State Security. This has placed a premium on security to safeguard these investments and a growing demand from executives of Chinese SOEs for a more robust Chinese security presence on the ground. While the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been averse to maintaining a large presence in Africa due to a host of reputational and logistical factors, China is not confident that African security forces can do the job.

The Chinese government is, consequently, increasingly relying on Chinese security firms as part of its security mix. There are 5,000 security firms registered in China, employing 4.3 million ex-PLA and People’s Armed Police. Twenty of these are licensed to operate overseas and report that they employ 3,200 individual contractors, more than the size of PLA peacekeeping deployments, which number around 2,500 troops. The actual number of Chinese contractors in Africa is doubtlessly significantly higher. Beijing DeWe Security Service and Huaxin Zhong An Security Group employ 35,000 contractors in 50 African countries, South Asia, the Middle East, and China. Overseas Security Guardians and China Security Technology Group employ 62,000 in the same regions. In Kenya, DeWe employs around 2,000 security contractors to protect the $3.6-billion Mombasa-Nairobi-Naivasha Standard Gauge Railway alone.

China does not want its security providers to be compared to Russia’s shady Wagner Group or the disbanded American security firm, Blackwater. Yet that is a real danger. Moreover, Chinese security contracting comes with many of the same risks associated with some Chinese SOEs, including a lack of transparency, weak national controls, undue influence on regime elites, and social tensions.

The proliferation of foreign security firms has important policy implications for Africa as it undermines the government’s role as the primary security provider within a country and heightens the risk of human rights violations. A more robust regulatory process in Africa will be essential to prioritize and protect African citizen interests.

***

Paul Nantulya, “Reshaping African Agency in China-Africa Relations,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2 March 2021.

The interests of African citizens can be strengthened in investment deals with China by ensuring agreements are transparent, technical experts are involved, and the public is engaged.

The asymmetries in power between China and its African partners are immense. Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy with a GDP of roughly $500 billion, is a fraction of China’s GDP of $14.3 trillion. China is Africa’s largest trading partner, with trade growing 40-fold in the past 20 years. China is also Africa’s single biggest creditor, holding 20 percent of the continent’s debt. African countries borrowed around $143 billion in combined Chinese state and commercial loans between 2006 and 2017.

African countries make up half of the 50 nations that are most indebted to China, with Djibouti, the Republic of the Congo, Niger, and Zambia topping the list in terms of share of GDP. These countries demonstrate how spiraling debt with China can have a ripple effect on shrinking African leverage. Zambia is a case in point. In 2020, it appealed to China to restructure $11 billion in loans. China, however, insisted that all its arrears be cleared as a precondition, a demand Zambian President Edgar Lungu had no leverage to resist. Other lenders whom Zambia had asked for bailouts suddenly became reluctant to offer the country concessions as they might be used to pay arrears to Chinese creditors. According to Ken Ofori, Ghana’s finance minister, China’s approach to debt negotiations disadvantages its highly indebted partners as it makes other creditors nervous that “their released resources will simply be transferred to Beijing.”

Fears that unsustainable debt could cause African countries to lose control of their national assets are also growing. In 2018, the Kenyan public was shocked when a leaked report from the auditor general revealed that the strategic port of Mombasa had been put up as a sovereign guarantee. That is, its escrow account would be surrendered to China’s Export-Import Bank if the Kenyan government defaulted on its $3.2-billion loan for the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway. In Zambia, worries that Chinese firms will seize key assets to recover debts frequently make the headlines, with the local power utility, ZESCO, and the international airport being cited in a flood of angry media reports since 2018.

Concerns over imbalance have been raised over other facets of Chinese investments as well. For example, many African commentators note that Chinese firms, which currently dominate African construction tenders, mainly hire Chinese labor and import Chinese material in multibillion-dollar projects. The common understanding is that African countries give in to such practices because the financing, impact assessments, and project execution are all done by Chinese entities. Saying no to China means that the money might go elsewhere.

The issue of corruption often features prominently in these agreements as African government leaders tend to negotiate opaque deals that benefit them personally or extend their patronage network. African leaders, therefore, are less inclined to write more stringent standards of accountability and local ownership into these agreements.

Given the paucity of empirical data, the secrecy of Sino-African negotiations, and the widely varying motivations of African leaders, it’s hard to generalize how this imbalance plays out in individual countries. For instance, a 2017 study by McKinsey found that of the 1,000 Chinese firms in 8 African countries that receive the lion’s share of Chinese labor-intensive investments, 89 percent of the laborers were African. A study conducted over 4 years by the University of London’s School of African and Oriental Studies found that in Angola and Ethiopia—high-profile countries for Chinese investment—the local participation rate of African labor is 90 percent and 74 percent respectively.

Nevertheless, as many details of these agreements remain tightly held between African leaders and their Chinese counterparts, it’s hard to say how these deals benefit African citizens. That concerns about harmful practices continue to be raised underscores very real fears about the lopsided nature of these engagements. Consequently, a growing number of Africans do not view the relationship as a “mutually beneficial partnership” (hùhuì huǒbàn guānxi, 互惠的伙伴关系) as is often promoted.

Given the challenges inherent within this imbalanced power relationship, how can African citizens effectively assert agency over their national interests? … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Chinese Security Contractors in Africa,” Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, 8 October 2020.

As China’s engagement with African countries has grown over the past several years, Beijing is increasingly turning to security contractors to protect its Belt and Road Initiative projects, citizens, and diplomats.

Introduction

As China’s engagement with African countries has grown over the past several years, Beijing is turning to security contractors to protect its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, citizens, and diplomats. Chinese security contractors are active in a growing number of African countries; they mostly work for Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and increasingly with African security forces and security companies. They protect oil and gas installations, railways, mines, construction sites, and even Chinese embassies.

China has long claimed to “keep a low profile” and uphold its doctrine of “non-interference” in its foreign policy, and it has largely declined to deploy its armed forces abroad. But these diplomatic tenets are now being severely tested, as China’s rapidly expanding interests in Africa have created a need for security contractors to provide protection for those interests.

Over 200,000 Chinese workers have relocated to Africa in search of opportunities along the BRI as of 2018, bringing the total number of Chinese immigrants to over 1 million. Furthermore, over 10,000 Chinese companies were operating on the continent as of 2017.

China’s economic power in Africa is unmistakable; in 2017 alone, Chinese SOEs generated about $51 billion in revenue from local BRI projects, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics. As of 2020, China was responsible for more construction projects in Africa than France, Italy, and the United States combined. However, China’s expanded global engagements are fraught with risks. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences notes in its 2020 assessment that 84 percent of China’s BRI investments are in medium- to high-risk countries.

To protect its investments, Beijing has invested in and trained security contractors. As of 2013, China had around 4,000 registered security firms with an estimated 4.3 million employees, mostly demobilized military and police personnel. Phoenix International, a Chinese think tank with strong SOE ties, reports that likely no more than twenty of these firms conduct activities overseas protecting SOEs and other Chinese interests. By 2013, they employed around 3,200 personnel, according to the Germany-based Mercator Institute for China Studies, more than the number of United Nations (UN) peacekeepers China furnishes, a figure that stood at 2,534 troops and police as of June 2020.

The true number of Chinese private security contractors, however, could be much higher. Chinese SOEs spend about $10 billion annually on security, according to the Beijing-based China Overseas Security and Defense Research Center.

The International Data Corporation reports that China, as well as Latin America and Asia-Pacific countries, will account for the largest growth in overseas security spending between 2019 and 2023. From this perspective, China’s strategic shift from keeping a low profile to claiming global leadership sets the stage for the expansion of Chinese overseas security contracting. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “China Promotes Its Party-Army Model in Africa/La Chine promeut son modèle Parti-armée en Afrique,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 28 July 2020.

China’s party-army model, whereby the army is subordinate to a single ruling party, is antithetical to the multiparty democratic systems with an apolitical military accountable to elected leaders adopted by most African countries.

“The Chinese party-army model also tends to reinforce elite networks and hierarchies, which feature heavily in China’s political relationships and often supersede institutional and constitutional procedures.”

The principle of absolute party control of the military is one of the pillars of China’s governance model. It follows the central rule—“The party commands the gun, and the gun must never be allowed to command the party” (Qiānggǎn zi lǐmiàn chū zhèngquán, 枪杆子里面出政权)—coined by the founder of the Communist Party of China (CPC), Mao Zedong. The adage defines the relationship between the ruling party and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), as well as the party’s tight control of the Chinese government, which is often described as a “party state” (dǎng guó, 黨國).

As China deepens its ties to African militaries, including through training and education initiatives, Beijing brings its perspective on party-army relations. The venues through which it does this have been growing steadily in the past decade. For example, under its China-Africa Action Plan 2018-2021, China receives 60,000 African students annually, which surpasses both the United States and United Kingdom. China provides an additional 50,000 professional training opportunities and 50,000 government fellowships to African public servants. Around 5,000 slots go to military professionals, up from 2,000 under its 2015-2018 Plan.

The concept of party supremacy over the military is at odds with the principle of an apolitical military, which is central to the multiparty democratic systems adopted by nearly all African constitutions since the early 1990s. The Chinese party-army model has obvious appeal to some African ruling party and military leaders who welcome redefining the role of the military as ensuring the survival of the ruling party. It also tends to reinforce elite networks and hierarchies (guānxi, 关系), which feature heavily in China’s political relationships and often supersede institutional and constitutional procedures. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Post-Nkurunziza Burundi: The Rise of the Generals/Le Burundi après Nkurunziza: les généraux en ordre de marche,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 22 June 2020.

In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza’s sudden death has exposed power struggles within the ruling party and the ascendancy of the military.

“Nkurunziza’s legacy of patronage-based and repressive governance means whoever controls the levers of power has wide scope for self-enrichment and violence.”

Barely two weeks after an election marked by government violence, intimidation, extrajudicial killings, and a media blackout, Burundians were shocked by news that longtime president, Pierre Nkurunziza, 55, had died. Rumors swirled about possible causes, with some saying he died of COVID-19 and others citing foul play. The government said he died of cardiac arrest. A succession crisis immediately ensued, exposing rifts in the ruling party and military.

General Evariste Ndayishimiye, the ruling party candidate widely known by his guerrilla nickname Neva (“never”), claimed a landslide victory in the May 20 presidential elections in a process that was widely seen as unfair. Recognizing that the playing field was not level, the African Union didn’t send observers. On May 11, 9 days before the polls, Burundi authorities informed East African Community observers that they would face a mandatory 14-day quarantine because of COVID-19. The observers, consequently, pulled out. Over 200 of the opposition National Freedom Council’s poll observers were illegally detained. Burundi’s highly respected Catholic Bishops Conference did field 2,716 observers in all 119 municipalities, however. And they denounced the polls as neither free nor fair based on their tally. The government reacted by demanding the bishops be defrocked. On June 4, the seven-member Constitutional Court—all ruling party appointees—threw out the opposition’s petition to annul the results.

The quarantine for external poll observers is ironic given Burundi’s disregard for World Health Organization (WHO) safety guidelines. Campaign rallies drew large crowds without masks or social distancing. Three weeks before polling, Nkurunziza downplayed the risks, claiming that masks were unnecessary because “God has purified the air of Burundi.” He then expelled the WHO coronavirus task force for “unacceptable interference.” Burundi now faces a spike in underreported cases.

This series of crises came on top of an ongoing political upheaval that erupted in 2015 when Nkurunziza refused to step down at the end of his second constitutionally mandated term. This violation of Burundi’s fledgling democratic process triggered massive peaceful protests, a violent crackdown against civil society and the political opposition, targeted assassinations in the military, and a failed coup. Burundi has known turbulence since then, with an estimated 1,700 people having been killed and close to 500,000 of the country’s 11 million citizens now refugees. The United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Burundi has noted that the death toll is grossly undercounted given the scale of mass atrocities committed. This is corroborated by hundreds of eyewitness testimonies, data obtained through government sources, and mass graves discovered around the country.

Nkurunziza’s legacy of patronage-based and repressive governance means whoever controls the levers of power has wide scope for self-enrichment and violence against their rivals. This is all the more significant given Burundi’s history of ethnically based violence and the potential for greater regional instability. … … …

***

Ambassador Phillip Carter III, Dr. Raymond Gilpin, and Paul Nantulya, “China in Africa: Opportunities, Challenges, and Options,” in Scott D. McDonald and Michael C. Burgoyne, eds., China’s Global Influence: Perspectives and Recommendations (Honolulu, HI: Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, September 2019).

Introduction

The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) diplomatic, economic, and security engagements with Africa have deepened since the turn of this century. The PRC and private Chinese firms, many of them backed by central and local governments, are visiting Africa more frequently, while foreign direct investment (FDI) and development assistance are trending upward.2 In addition, growing People’s Liberation Army (PLA) engagement with African countries and regional institutions is evidenced by increased security assistance, consistent support for peacekeeping initiatives, and a growing military footprint. Understanding the geo-strategic implications of these developments requires a careful analysis of four key questions. Does the recent acceleration constitute a trend? How much influence does the PRC derive from these engagements? How do African countries perceive recent developments? How do Beijing’s interventions compare to those of Africa’s other external partners?

This chapter starts with a strategic analysis of the evolution of China-Africa relations to unpack the drivers of this relationship. While it is true that China has had a long-standing relationship with Africa and tends to play the long game, the historical overview also highlights important transactional dimensions. Chinese officials often make short-term decisions based on their national self-interest or policy adjustments. Meanwhile, African governments are becoming more selective and circumspect as pressure grows from African civil society, academics, and private sector leaders for more equitable deals with the Chinese that enhance transparency, eliminate corruption, and avoid unsustainable debt.

While many African countries acknowledge China’s role in critical areas, like infrastructure development and peacekeeping operations, some have become wary of potential downsides of dependency, dumping, security arrangements that compromise human rights, and onerous debt. Increasingly, Chinese involvement is being evaluated within the context of the roles, activities, and relative costs of opportunities pro- vided by other development partners. Consequently, in Africa, any analysis of the implications of Chinese engagements must include a broader discussion of other external partners. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Burundi, the Forgotten Crisis, Still Burns/Le Burundi, la crise oubliée, brûle toujours,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 24 September 2019.

Although Nkurunziza has suppressed external reporting on Burundi, the country’s 4-year-old political and humanitarian crisis shows no signs of abating.

Mass atrocities and crimes against humanity committed primarily by state agents and their allies continue to take place in Burundi, according to the September 2019 report of the UN Commission of Inquiry on Burundi. The Commission, moreover, found that President Pierre Nkurunziza and many in his inner circle are personally responsible for some of the most serious of these crimes. They include “summary executions, arbitrary arrests and detentions, acts of torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, sexual violence, and forced disappearances.”

The Commission has been investigating the Burundi crisis since 2016. Its findings mirror those of the International Criminal Court, which opened a separate investigation in 2017 based on “a reasonable basis to believe that state agents and groups implementing state policies … launched a widespread and systematic attack against the Burundian civilian population.” The persistence of such atrocities echoes Burundi’s 1972 and 1993 genocides and the brutal civil war that ended in 2005. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Escalating Tensions between Uganda and Rwanda Raise Fear of War/L’escalade des tensions entre l’Ouganda et le Rwanda suscite la crainte d’une guerre,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 3 July 2019.

The long simmering rivalry between Yoweri Museveni and Paul Kagame has escalated border tensions into a serious risk of armed interstate conflict.

“Reflecting the limited checks and balances in authoritarian governance structures, senior officials on both sides have also escalated their rhetoric rather than serving as moderating influences.”

Formerly staunch allies, Uganda and Rwanda are at loggerheads. Since March 2019, their armies have been massing along their border. In May 2019, tensions rose after Uganda protested what it said was an incursion by Rwandan forces onto Ugandan territory, killing two civilians in the border town of Rukiga. Rwanda refuted the claim, saying that it was pursuing a group of smugglers that had illegally crossed over to its side of the border.

The trigger to the rapidly escalating tensions between the two countries was a December 2018 Report of the United Nations Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) that found that the military wing of a coalition of Rwandan opposition groups calling itself the “Platform Five,” or P5, was being armed and trained by Uganda, Burundi, and the DRC. The P5 military forces are led by General Kayumba Nyamwasa—formerly a Ugandan senior army officer and also a former Rwandan Army Chief of Staff. The P5 has been in existence since at least 2014 and seeks to overthrow the ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF). Unlike other Rwandan rebel outfits such as the Interahamwe, the P5 is dominated by former high-ranking RPF government, intelligence, and military officials, the vast majority of whom once served in the Uganda military and government.

In July and December 2018 as well as April 2019, P5 elements and their allies launched attacks into Rwanda. The December attack led to the deaths of two Rwandan soldiers and an unknown number of rebels. Two civilians were killed and eight were seriously wounded in the April assault. Rwanda pursued and captured three senior Rwandan rebel commanders accused of leading the attacks. They are now facing a military tribunal.

In February 2019, Rwanda closed its border with Uganda after accusing Kampala of harboring Nyamwasa’s fighters and arbitrarily detaining and torturing Rwandan nationals—charges Uganda denies. The border was reopened briefly in early June but shut again a few weeks later. Rwanda has issued a travel advisory warning its citizens not to travel to Uganda. Alarmed by the escalation, a coalition of three civil society organizations have sued Uganda and Rwanda in the East African Court of Justice over the border closure and other acts of hostility that they say are hurting ordinary citizens.

Over the past year, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni and Rwandan President Paul Kagame have exchanged threats laced with loaded cultural messaging. Reflecting the limited checks and balances in authoritarian governance structures, senior officials on both sides have also escalated their rhetoric rather than serving as moderating influences. This has put the two countries on a war footing. During a briefing for military attachés accredited to Uganda in May shortly after the cross-border shooting, Uganda’s army chief, General David Muhoozi, and the Rwandan defense attaché, Lt. Col. James Burabyo, had a heated exchange, falling just short of personal insults, to the astonishment of other envoys in the room.

General Nyamwasa added fuel to the fire in May 2019 during an interview with Uganda’s state media in which he accused Rwanda of sponsoring a coup attempt in Burundi three years ago and backing former Burundi army officers that joined the Resistance for Rule of Law (Red Tabara) and other rebels fighting President Pierre Nkurunziza, such as the Republican Forces of Burundi (FOREBU). Kigali saw his appearance on a Uganda government media outlet as yet another indication of ongoing collaboration among Rwandan rebels, Uganda, and Burundi.

The prospect of war between Uganda and Rwanda is also significant since interstate conflict in Africa has become rare with nearly all active armed conflicts on the continent today an outcome of unresolved domestic grievances and rivalries.

Tensions between Uganda and Rwanda also have direct implications for stability in the Great Lakes region more generally, with Burundi becoming a key flashpoint of the rivalry between Kampala and Kigali. Rwanda, which recently succeeded Uganda as EAC chair, decries what it calls “connections between Bujumbura and Kampala” and blames both for allowing the P5 and other armed groups to use Burundi as an operational base. The UN has reported on clashes in the DRC’s South Kivu region between P5 fighters and Red Tabara, which is the largest rebel group battling the Burundi government.

Hostility between Uganda and Rwanda also distracts and diminishes regional capacity to combat other crises in the Great Lakes region, not least the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) insurgency, and efforts to respond to the expanding Ebola outbreak in the eastern DRC.

The economic costs of the crisis are also being felt. Uganda’s imports from the East African Community (EAC) increased more than 8 percent in the 2017–2018 fiscal year, largely due to trade with Rwanda and Burundi. This will decrease significantly given the restriction of movement across the Uganda/Rwanda border and the continuing crisis in Burundi. Museveni dismissed the issue, saying that his country “will find better markets.” He did so in full military regalia, signifying that this was more than a trade war. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “The Challenging Path to Reform in South Africa/La voie difficile de la réforme en Afrique du Sud,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 11 June 2019.

Despite voters’ repudiation of corrupt governance practices, the ANC remains divided in its commitment to reforms.

The Zuma Effect Continues to Hurt the ANC

Perceptions of disillusionment and growing polarization stand out in the wake of the general elections in South Africa. With just 66 percent of voters casting ballots in May’s elections, turnout was the lowest in South Africa’s democratic history. This downturn reflects widespread disenchantment with government among South African citizens. Rampant corruption and impunity under former President Jacob Zuma, who led South Africa from 2009-2018, have driven away voters, especially young people who feel the ruling African National Congress (ANC) has lost its way. As much as 4.9 trillion rand ($339 billion), or a third of South Africa’s GDP, was misdirected during Zuma’s scandal-filled presidency.

Although the ANC did not perform as badly at the polls as many observers anticipated, its 58 percent rate of support was its worst showing in a national election since democracy was established in 1994. This continues its slow decline in support from 70 percent in 2004, 66 percent in 2009, and 63 percent in 2014. It is now 35 seats short of the two-thirds majority it had enjoyed continuously since 1994. Some ANC voters gravitated toward the populist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a breakaway of the ANC’s militant Youth League. Others supported the centrist Democratic Alliance (DA), which has made inroads among black voters despite its identity as a predominantly white party.

The EFF, which campaigned on a redistribution platform, including land confiscation and nationalization of mines, secured 10 percent of the vote, up from 6 percent in 2014, becoming the only mainstream party to increase its share of the electorate. The EFF is now the official opposition in three provinces. Meanwhile, the DA remains the official opposition at the national level, despite having failed to increase its share of the vote for the first time since 1994. A section of its white supporters voted for Ramaphosa in the hope of countering Zuma’s followers. Others chose the white nationalist Vryheidsfront (Freedom Front) partly due to rising fears of forceful land and property expropriation, which the EFF and Zuma’s most ardent supporters have championed.

There was a spike in racially-charged rhetoric under Zuma. Moreover, several racially-based parties formed before the elections, such as Black First Land First (BLF) and African Transformation Movement (ATM), have links to the former president. While campaigning, BLF members forcefully occupied and vandalized white-owned homes and farms in Cape Province. Reports also surfaced of small groups of white farmers arming themselves for self-defense. Notably, however, the BLF and ATM performed poorly in the polls. Moreover, the Cape Town-based Institute for Justice and Reconciliation’s latest survey of race relations found that nearly 70 percent of South Africans support greater racial integration and reconciliation. Left unchecked, however, the rise in racial rhetoric threatens to undermine the foundations of the post-apartheid settlement. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “High Stakes in South Africa’s Elections/Les enjeux cruciaux des élections en Afrique du Sud,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 3 May 2019.

Competing factions of the ANC and other political parties have vastly different visions for handling sensitive issues of corruption, land expropriation, and restoring trust in South Africa.

South Africa’s sixth elections since the end of apartheid have the potential to reconfigure South Africa’s political landscape. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) is embroiled in a fierce internal struggle over its future trajectory. Two factions are jostling for control: one aligned to the patronage-based ex-president, Jacob Zuma, and the other to his successor, President Cyril Ramaphosa, who is standing on a platform of reform, renewal, and accountability. Zuma’s loyalists support populist policies that resonate with the ANC’s constituency on the left, such as land expropriation without compensation and the nationalization of the South Africa Reserve Bank (or central bank). They are distrustful of Ramaphosa’s platform and have largely stayed away from major campaign events. Many Zuma-era politicians implicated in the ongoing judicial inquiry on state capture are the ANC candidates for parliamentary and provincial seats, fueling concerns that they will undercut Ramaphosa’s reform agenda if elected.

The ANC’s support has dropped to historic lows due the systematic diversions of state resources under Zuma, detailed in the State of Capture and Secure in Comfort reports. The leftist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), which broke away from the ANC in 2013, has made inroads in ANC strongholds and is now the third largest party in the country—despite also being the youngest. The perilous state of the ANC was laid bare in a damning internal reportpresented to the rank and file at the 54th National Conference in December 2017. Its overall strategic assessment of the party struck a somber note: “We are today faced with a painful challenge, where the entirety of the liberation movement is projected as corrupt.” … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “The African Union Wavers between Reform and More of the Same/Entre réformer ou poursuivre sur la même lancée, l’Union africaine hésite,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 29 April 2019.

The African Union will need to overcome a lack of political will and address structural challenges if it is to be effective in responding to security crises on the continent, consistent with its founding mission.

The African Union’s ability to respond effectively to political crises has been hampered by institutional challenges, dating back to well before it was established to replace the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 2002. Intended to address some of the OAU’s inadequacies, the reforms that laid the foundation of the AU were rooted in the findings of a special OAU panel that investigated the circumstances leading to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, the reasons the international community failed to act sooner, and the institutional gaps that eventually prevented a coherent response from the OAU and the United Nations.

In response to the panel’s findings, the new AU undertook three major reforms.

First, it would prioritize “non-indifference” over the OAU’s principle of “non-intervention.” The new organization would embrace the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine, which asserts that sovereignty is not a privilege but a responsibility and that states cannot invoke it to shield themselves from scrutiny for harming their citizens. Indeed, in such situations, other states are obligated to intervene. This concept was incorporated into the AU’s Constitutive Act under Article 4(h).

Second, it established several new institutions that were meant to be more effective than their predecessors. These included the AU Commission (AUC), which runs day-to-day operations and is mostly staffed by professionals, unlike the OAU’s General Secretariat, which had been dominated by political appointees. The Pan-African Parliament and the Economic, Social, and Cultural Council (ECOSOCC) were also established. Both institutions play a role in the AU’s conflict prevention and management initiatives.

Civil society bodies from each of the AU’s five regions and Africa’s diaspora make up the ECOSOCC. The ECOSOCC engages the AU on peace and security issues through its Peace and Security and Political Affairs Committees. It also conducts visits to countries in conflict, prepares reports and analyses on conflict situations, and engages conflicting parties directly. The ECOSOCC’s decision-making body, the General Assembly, at times takes official positions that differ with those taken by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government. The Pan-African Parliament, whose membership reflects the composition of Africa’s 54 legislatures, conducts fact-finding missions, acts as a third-party mediator, and participates in the organization’s peace and security deliberations and decisions. Its specialized Committee on Cooperation, International Relations, and Conflict Resolution works autonomously of other AU organs.

Third, new protocols were set up to enforce ethical standards. Adopted in January 2007, the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance, for instance, outlines punitive measures against incumbents that refuse to leave power after losing elections, or those that seek to revise constitutions and laws to remain in office at all costs. The Charter entered into force as a legal instrument in 2012 after 15 countries ratified it. It has now been ratified by 32 countries and signed by 46.

Nearly two decades after the AU’s founding, however, many of these reforms have yet to be meaningfully implemented. As a result, the AU is still hobbled by the same institutional weaknesses that stymied the OAU. In a growing number of cases, members have also openly undermined and defied AU resolutions. The AU’s impotence in dealing with situations in DRC, Burundi, and South Sudan, among other crises, shows that the institutional reforms intended to correct the problems of the past have yet to take root. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Implications for Africa from China’s One Belt One Road Strategy/

Les enjeux du projet chinois « Une ceinture, une route » pour l’Afrique,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 22 March 2019.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative forges intertwining economic, political, and security ties between Africa and China, advancing Beijing’s geopolitical interests.

The end state of One Belt One Road is the building of a new global system of alternative economic, political, and security “interdependencies” with China at the center.

Launched in 2014, One Belt One Road (一带一路), presented internationally as the Belt and Road Initiative, is China’s signature vision for reshaping its global engagements. It is strategic and comprehensive in scope and an essential component of the Communist Party of China’s (CPC’s) twin objectives of achieving national rejuvenation (zhonghua minzu weida fuxing, 中华民族伟大复兴) and restoring China as a Great Power (shi jie qiang guo, 世界强国). It now spans three continents and touches 60 percent of the world’s population. The 65 or so countries that have so far signed on to the program (including approximately 20 from Africa) account for 30 percent of the world’s GDP and 75 percent of its energy reserves. Some 50 Chinese state owned companies are implementing 1,700 infrastructure projects around the world worth about $900 billion. One Belt One Road (OBOR) has been written into the state and ruling party constitutions as strategic priorities for China to attain Great Power status by the middle of the 21st century. All of China’s leaders have advanced this quest since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, but the pursuit has accelerated under President Xi Jinping.

Strategic Rationale

The end state of One Belt One Road is the building of a “Community of Common Destiny for Mankind” (人类命运共同体), defined as a new global system of alternative economic, political, and security “interdependencies” with China at the center (zhongguo, 中国). For this reason, Chinese leaders describe One Belt One Road as a national strategy (zhanlüe, 战略), with economic, political, diplomatic, and military elements (综合国力), not a mere series of initiatives.

OBOR directly supports many elements of China’s national security strategy. At a macro level, it seeks to reshape the world economic order in ways that are conducive to Beijing’s drive for Great Power status. One Belt One Road has two components. The Silk Road Economic Belt establishes six land corridors connecting China’s interior to Central Asia and Europe. It includes railroads to Europe, oil and gas pipelines from the Caspian Sea to China, and a high-speed train network connecting Southeast Asia to China’s eastern seaboard. The Maritime Silk Road establishes three “blue economic passages” knitted together through a chain of sea ports from the South China Sea to Africa that also direct trade to and from China.

One Belt One Road also increases Beijing’s control of critical global supply chains and its ability to redirect the flow of international trade. Central to these efforts are moves to open new sea lines of communication and expand China’s strategic port access around the world. In 2017, Chinese state-owned companies announced plans to buy or secure majority stakes in nine overseas ports, all located in regions where China plans to develop new sea lanes. This is in addition to the 40 ports in Africa, Asia, and Europe in which Chinese state-owned firms hold stakes worth a combined $40 billion.

China’s return on investment from increased port access and supply chains is not all about economics. In five cases—Djibouti, Walvis Bay (Namibia), Gwadar (Pakistan), Hambantota (Sri Lanka), and Piraeus (Greece)—China’s port investments have been followed by regular People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy deployments and strengthened military agreements. In this way, financial investments have been turned into geostrategic returns.

China’s 13th Five Year Plan, a document adopted in 2016 that provides long-range implementing guidance in five-year increments, calls for the “construction of maritime hubs” to safeguard China’s “maritime rights and interests” as it embarks on laying a “foundation for maritime Great Power status” by 2020. The centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, 2049, has been set as the year when it will become the world’s “main maritime power” (海洋强国). Accordingly, China’s drive to acquire port access and secure supply lines are likely to intensify alongside the expansion of the Maritime Silk Road. In 2010, only one-fifth of the world’s 50 largest deep water ports had any Chinese investment. By 2019, it had increased to two-thirds. The China Ocean Shipping Company, which controls most Chinese overseas port holdings, is now the world’s fourth largest shipping fleet. Beijing’s merchant marine has quadrupled since 2009 to become the world’s second largest. It now moves more global cargo that any other country.

Beijing also plans to use the artery of routes envisaged under OBOR to reduce China’s dependence on maritime chokepoints that could be contested by rivals. The PLA is locked in territorial disputes with Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Brunei, in [the] so-called “near seas” (jinhai 近海). This raises the risk that they could create a blockade during a crisis that would disrupt its shipping. To counter the threat, One Belt One Road is being positioned to reroute traffic to Chinese-built port clusters in Sudan, Djibouti, Gwadar, Hambantota, Colombo, and Myanmar to bypass narrow chokepoints in the South China Sea.

As a party political instrument, OBOR strengthens Xi’s authority at home. It is a central element of “Xi Jinping Thought,” which is inscribed in the state and party constitutions as a guiding philosophy. This further enables Xi to marshal every resource at his disposal to see his signature program through.

Funding for One Belt One Road comes from “policy lenders” (政策性银行), so called because their lending decisions are responsive to presidential and geostrategic preferences. They include the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank), which have committed over $1 trillion. The Silk Road Fund holds $40 billion in investment funds and is supervised by China’s Central Bank. The Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, whose remit now includes Africa, has a capital base of $100 billion. Additional funds come from China’s foreign exchange reserves and its sovereign wealth fund, which hold $7 trillion and $220 billion, respectively.

To be sure, OBOR faces many problems. First, debates on Chinese social media tools such as Weibo and Renren suggest that it does not enjoy broad domestic support. Second, concerns are growing about economic sustainability in the countries where massive Chinese-funded infrastructure projects are being implemented, as their governments take on more debt to pay for them. Third, hostility is rising in many countries toward policies that favor Chinese workers over locals in construction and infrastructure contracts. This has been most prominent in African countries, such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia, to name a few. Fourth, some of Beijing’s rivals in Asia and around the world are increasingly uneasy about what they see as an effort to use OBOR to expand China’s military posture and political leverage. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “The Ever-Adaptive Allied Democratic Forces Insurgency/La nature évolutive des Forces démocratiques alliées,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 8 February 2019.

The ADF, one of the least understood militant groups in the Great Lakes, has endured for over 20 years by instrumentalizing Islamist, ethnic, and secessionist ideologies to recruit and forge new alliances.

A surge in violent activity by the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) has demonstrated growing virulence in this mysterious group operating on the borders of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The number of violent events linked to ADF tripled in 2018, to 132 from 38 in 2017. Fatalities doubled to 415 over the same period. This includes the killing of peacekeepers from the United Nations Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), as well as civilians along the DRC/Uganda border. In all, the deaths of 700 civilians have been attributed to the ADF since 2014.

The ADF is one of the oldest, yet least understood militant groups in Africa. An offshoot of the Ugandan Tabliq/Salafi movement from the mid-1990s, it has been based for most of its existence in the DRC, where it became deeply embedded in local sociopolitical dynamics and conflicts. While this might suggest that it lost its Ugandan character, its goals still include the overthrow of the regime of Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, and the bulk of its known senior leadership is Ugandan. The ADF has taken on many faces ranging from Salafi-Jihadi to secular-nationalist, ethno-nationalist, and secessionist, with each aimed at different audiences and employed for different purposes. While little is known about its internal workings given its highly secretive nature, one major challenge in developing a coherent strategy to defeat the ADF lies in the difficulty of determining which of these identities is dominant at a given point in time. To add to this complexity, the ADF has from time to time served as a proxy in the Great Lakes region’s extended and complicated conflicts.

Recent reports suggest that the ADF is attempting to forge ties to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Its flag incorporates a new name, Madina at Tauheed Wau Mujahedeen (“City of Monotheism and Holy Warriors”). Documents and videos seized during MONUSCO operations suggest that it is currently focusing on establishing a caliphate in the region. The movement in recent years has also vigorously enforced strict Islamic law in its strongholds in the DRC and sought to radicalize and increase its recruitment of Congolese Muslims. The growing prominence of ISIS-inspired narratives in ADF propaganda videos coincide with efforts by the ADF to return to its Salafi roots so that it could exploit Jihadi-Salafi networks in East Africa. These efforts increased after its dramatic loss of territory in the wake of a series of military offensives by Ugandan, Congolese, and UN forces and the capture of its charismatic leader, Jamil Mukulu, in Tanzania in 2015. He is currently being held in Uganda on charges of mass murder, terrorism, and crimes against humanity at the Special War Crimes Division of the Ugandan High Court. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Chinese Hard Power Supports Its Growing Strategic Interests in Africa/

Les activités stratégiques croissantes de la Chine en Afrique reposent sur le hard power chinois,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 17 January 2019.

China’s growing military engagement in Africa is aimed at advancing Beijing’s economic and strategic interests, in particular its Belt and Road Initiative.

The debate on China-Africa relations has largely focused on Beijing’s massive infrastructure projects around the continent. Less noticeable but no less significant are its security activities, which have grown in scale and scope alongside President Xi Jinping’s signature One Belt One Road strategy—presented internationally as the Belt and Road Initiative—to create new international infrastructure, trade, and investment links to the Chinese economy.

China’s growing military footprint in Africa is part of a policy that has at its core the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation (zhonghua minzu weida fuxing, 中华民族伟大复兴) and its restoration as a “Great Power” (shi jie qiang guo, 世界强国). In the past decade, Beijing has pursued an increasingly competitive and assertive foreign policy that made a decisive break with Beijing’s decades-long approach of “hiding our capabilities,” “biding our time,” and “keeping a low profile”—a policy known as taoguang yanghui (韬光养晦). According to Xi, “China now stands tall and firm in the East” and should “take center stage” in the world. This theme is echoed in the Diversified Employment of the Armed Forces, China’s defense guidance, which says that a world-class military deployable in a wide range of scenarios is indispensable in pursuing the “Great Rejuvenation of China.”

In 2015, China passed a law that allows overseas deployments of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and China’s other security forces, including the People’s Armed Police. Two years later, Beijing opened its first foreign naval base in Djibouti. In July 2018, the PLA constructed additional pier facilities at the base, and in November, it conducted live fire exercises there, employing armored fighting vehicles and heavy artillery—the first time China had conducted exercises on such a scale on foreign soil. That same month, PLA helicopters conducted a major training exercise to evacuate war casualties from a guided missile frigate off Djibouti’s coast, demonstrating China’s sophisticated ground and aerial capabilities in the region, in addition to its naval assets.

In 2018, the PLA conducted drills in Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, and Nigeria, while its medical units worked with counterparts in Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Zambia to develop their combat casualty care capabilities as part of decades-long relationships that involve arms sales and intelligence cooperation. In May, Burkina Faso established diplomatic relations with China and rescinded its recognition of Taiwan. The PLA is now developing ties to the Burkina Faso military that will likely feature training in counterterrorism and infrastructure protection, two key elements of Chinese engagement in the Sahel. In neighboring Mali, the PLA deployed its Sixth Battle Group, consisting of regular and Special Forces, to the United Nations-led Peacekeeping Operation in Mali (MINUSMA) to protect the mission’s Chinese and foreign staff and secure critical infrastructure. This deployment provided China with a security presence in a country that remains central in its ongoing effort to extend the BRI into the Sahel and the larger West African region.

Efforts to establish a comprehensive security assistance policy gained pace at the inaugural China-Africa Defense and Security Forum held June 26–July 10, 2018, ahead of the fourth Forum for China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in September. Defense officials from around 50 African countries developed new priorities for Chinese security engagement, including combating terrorism and piracy, and protecting Chinese nationals and economic infrastructure. These constitute an important part of the 2019–2021 China-Africa Action Plan, which established the overarching framework for China’s security programs in Africa. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Stability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo beyond the Elections/

La stabilité en République démocratique du Congo après les élections,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 28 November 2018.

Joseph Kabila seeks to maintain the status quo as the Democratic Republic of the Congo enters a transition amid growing instability.

President Joseph Kabila’s failure to step down when his term expired in December 2016 plunged the DRC into its worst political crisis since the Second Congo Civil War of 1998 to 2003. Since then, at least 1,200 citizens have been killed, many in extrajudicial killings by Congolese security forces for suspicion of participating in demonstrations. This has been accompanied by a 40 percent increase in human rights violations as a result of the disproportionate use of force by security forces during anti-Kabila protests. The unrest created by the political crisis has galvanized many of the estimated 70 armed groups in the DRC, some of which openly stated that they would “liberate the Congo” from a leader with no legitimacy.

Prospects that the December 30 elections will have a stabilizing effect are dim. The ruling People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD) remains in control of the electoral commission, as well as all branches of government and the security services. The subservience of these institutions to the executive undermined the credibility of the last presidential polls in 2011. Their continued partisanship suggests that the outcome of the December vote will not produce the legitimacy that free and fair elections are intended to generate. Revealingly, Kabila’s preferred successor, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, is a hardcore loyalist with strong links to the presidential family perceived by many to be a front man through whom Kabila would control affairs until 2023 when he will be eligible to run again. Disagreements in the opposition, meanwhile, have prevented it from presenting a unified candidate, potentially fumbling a golden opportunity given that just 16 percent of voters said they would vote for Shadary. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Grand Strategy and China’s Soft Power Push in Africa/

La Grande stratégie et la montée en puissance du pouvoir d’influence de la Chine en Afrique,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 30 August 2018.

China is doubling down on its soft power initiatives in Africa as part of China’s Grand Strategy to tap emerging markets, shape global governance norms, and expand its influence.

In July 2018, Tanzanian president John Magufuli laid a foundation stone for the Mwalimu Nyerere Memorial Academy, named for the nation’s revered founding president. The $45-million project, which is being fully funded and built by the Chinese government, will provide leadership training to emerging leaders from countries governed by the Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa (FLMSA). The decision to build this school was made at the biennial FLMSA summit in May 2017, which brought together the African National Congress of South Africa, Chama Cha Mapinduzi of Tanzania, Popular Front for the Liberation of Mozambique, Movement for the Liberation of Angola, Southwest African Peoples Organization of Namibia, and Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front. All had received Chinese backing during their fight against apartheid and colonialism.

This initiative and others show China’s growing ability to advance its strategic interests through cooption, cooperation, and inducements. At the 19th Communist Party of China (CPC) Congress in October 2017, President Xi Jinping called it “soft power with Chinese characteristics.” The concept of soft power was adapted from American scholar Joseph Nye’s writings from the early 1990s on the importance of culture, values, and ideals to shape global norms. Over time, the subject has stimulated intense interest in China. In 2017, Wang Huning, a leading proponent of soft power, was elected to China’s topmost body, the six-member Politburo Standing Committee. “China will be a global leader in national strength and international influence,” Xi said at the October Congress. “We will improve our capacity to tell our stories, present a multidimensional view, and enhance China’s cultural soft power.” … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “After Burundi’s Referendum, a Drive to Dismantle the Arusha Accords/

Réforme et renouveau ou toujours la même rengaine au Zimbabwe,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 20 July 2018.

Sweeping changes to Burundi’s constitution have consolidated power in the presidency, dismantled much of the Arusha Accords, and heightened the risk of greater violence and instability.

“The East African Community, which has been chairing peace talks on Burundi, along with the multilateral guarantors of the Arusha Accords, did not send observers to the referendum.”

The passage of Burundi’s controversial May 2018 referendum to alter nearly a third of the 2005 Constitution’s articles put the ruling CNDD/FDD party on the cusp of a long sought-after goal: to overturn the 2000 Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement.

Mediated by former Presidents Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Nelson Mandela of South Africa, the Arusha Accords ended the cycles of violence Burundi experienced from the 1960s through the genocides of 1972 and 1991 and the 1993–2005 civil war. The Accords built in systems that ensured the respect of political minorities, power sharing among parties, and inclusive governance. By abolishing these systems, the CNDD/FDD has tightened its control of the state apparatus and done away with mechanisms designed to hold it accountable. It will now rule virtually unchallenged.

The East African Community (EAC), which has been chairing peace talks on Burundi, along with the multilateral guarantors of the Arusha Accords—the African Union (AU), European Union (EU), and United Nations (UN)—did not send observers to the referendum. This, and the fact that the referendum was held despite the displacement of over 500,000 Burundians, who could not participate in the vote and almost all of whom felt threatened by the government, raise questions about the referendum’s legitimacy.

Additionally, the climate of intimidation and violence made it an unbalanced contest. The parties that remain in Burundi’s internal opposition largely stayed away from the referendum process and accused the government of massive voter intimidation. At the launch of the referendum campaign in December 2017, President Pierre Nkurunziza threatened to “correct” those who opposed the exercise. “Any person who stands against this… will have to contend with God.… But I know some people are deaf to these messages. Let them try.” In similar fashion, Désiré Bigirimana, administrator of the Gashoho municipality, was quoted at a rally in February as saying, “Anybody who will come and tell you anything other than a ‘yes’ to the referendum, or different from what President Pierre Nkurunziza says, should be lynched. Is that clear?”

Throughout the campaign and during voting, the CNDD/FDD’s ethnically based youth militia, the Imbonerakure, informed on real or perceived opponents, harassed the population, conducted illegal police operations, and forced recruitment into the ruling party through, in several cases, torture. This was corroborated by eyewitness interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch, which also documented scores of abuses committed between December 2017 and March 2018, including abductions, rapes, and killings by members of the police and intelligence, military, and the Imbonerakure. These atrocities extended across borders where Burundian refugees have been surveilled, threatened, abducted, and killed in some cases, by individuals suspected of being members of the Imbonerakure. The worst episode of violence occurred a week before voting, when unidentified gunmen massacred at least 24 people in a village in northwest Burundi.

Worries about the credibility of the referendum had been building for some time. In early May, the Chairman of the AU Commission, Musa Faki, wrote to EAC Chairman and mediator of the stalled inter-Burundian dialogue, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, warning that the referendum would deepen Burundi’s crisis. Similar warnings were delivered by the EU, UN, and AU.

A legal challenge to the referendum was thrown out by the Constitutional Court, which has been packed with Nkurunziza’s loyalists since its vice president was forced into exile in 2015 for refusing to endorse the president’s decision to run for a third term in office. The constitutional changes called for in the referendum took effect on June 6. Explosions and gunfire now occur with greater frequency. Local monitors have documented more disappearances and killings since the new laws were enacted, including beheadings and bodies dumped in public places, some of them with hands tied. Attacks on civilians by the Imbonerakure have continued, including one in mid-June that resulted in the deaths of eight civilians. Burundians continue to flee the worsening violence, adding to the nearly 500,000 citizens who have sought refuge in neighboring countries and 175,000 who have been internally displaced. The EAC peace talks remain suspended and the guarantors of the Arusha Accords are pondering their next steps. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Reform and Renewal in Zimbabwe or More of the Same?/

Réforme et renouveau ou toujours la même rengaine au Zimbabwe,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 28 June 2018.

Multiple possible scenarios could emerge from Zimbabwe’s July 30 polls—the country’s first without Robert Mugabe’s name on the ballot. For now, the military appears intent on leveraging its interests.

The bomb blast at the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) rally in Bulawayo on June 23 threatened to mar what has been Zimbabwe’s most peaceful election campaign in decades. President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who assumed the presidency after Robert Mugabe was pushed out by the military last November, was unharmed. However, two people were killed, and at least 49, including his two deputies, were injured. Many fear that this could have been an assassination attempt on Mnangagwa given the intense infighting between the military establishment and civilian ZANU-PF cadres since Mugabe’s ouster and an ongoing purge of his allies in the party. Mnangagwa has accused such factionalism as being behind the alleged plot. Despite the attack, the government refrained from declaring a state of emergency.

The July 30 election will be the first without Mugabe’s name on the ballot since independence in 1980. It will also serve as a litmus test for Mnangagwa, a former Mugabe protégé. Since the transition, in an effort to reduce Zimbabwe’s diplomatic and economic isolation, the government has been at pains to signal a shift toward greater inclusion. Mugabe’s removal came on the back of growing economic hardships. Zimbabwe’s economic outlook has been in decline since the Government of National Unity (2009–13) was disbanded. Hard currency is in short supply stoking inflation, past government profligacy has led to mounting debt, and unemployment remains very high. Agriculture, once Zimbabwe’s mainstay and chief foreign exchange earner, continues to post negative growth. Sanctions relief and the revamping of the economy provide powerful incentives for reform and re-engagement with the international community as ZANU-PF struggles to find new sources of legitimacy.

It has moved quickly in this regard. Zimbabwe applied to rejoin the Commonwealth and invited 61 countries and international agencies to monitor the July polls. In February, Zimbabwe broke tradition by according the deceased opposition doyen, Morgan Tsvangirai, a state-funded funeral—a rare distinction usually reserved for ZANU-PF stalwarts. More recently, the government permitted a major protest by the MDC over lack of electoral reforms. It would not, however, allow a planned counter demonstration by ZANU-PF youth due to safety concerns.

While such overtures have been welcomed, ZANU-PF’s agenda remains ambiguous. Many of its old features persist, such the military’s domination of party and government functions. Given that Mugabe’s ouster was partially prompted by the military’s desire to stem its declining influence in the party, the military’s overt entanglement in politics is a cause for concern. The risks of instability persist. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “When Peace Agreements Fail: Lessons from Lesotho, Burundi, and DRC/

Quand les accords de paix échouent: les leçons du Lesotho, du Burundi et de la RDC,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 30 April 2018.

Conflicts in Africa often reflect a breakdown of peace agreements that have been methodically dismantled by politicians intent on evading checks on power while oversight is weak. Vigilance is vital as early progress is not a guarantee of long-term success.

Many of the conflicts in Africa today are resumptions of earlier conflicts. These conflicts, therefore, reflect a breakdown, to some degree, of previously negotiated peace agreements. A review of the experiences from three of these cases—Lesotho, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—offers lessons that can help inform future such accords. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “South Africa’s Strategic Priorities for Reform and Renewal/Priorités stratégiques de l’Afrique du Sud pour la réforme et le renouveau,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 17 February 2018.

South Africans have high hopes that Cyril Ramaphosa will be able to deliver change to systemic state capture. However, sustained reforms in South Africa’s most important national institutions are required if those hopes are to be met.

Cyril Ramaphosa has come to power in South Africa as the head of a party and government deeply divided between reformists and those with a vested interest in maintaining entrenched patronage relationships. Under Jacob Zuma, corruption and abuse of office reached alarming levels, sapping public trust and costing the ruling ANC significant support. Zuma faces 783 counts of fraud in connection with a 1999 arms deal. A judicial inquiry is also underway to investigate how the Guptas—wealthy Indian immigrants with close ties to him—became a “shadow state” that influenced appointments and removals of ministers and directors of state-owned enterprises for private gain.

Ramaphosa’s program to end state capture, root out party corruption, and entrench accountability have been endorsed by the ANC and government as South Africa’s strategic guidance for the next five years. But actual implementation of a comprehensive reform program will be a delicate task, and the stakes are high. Corruption is now the dominant social issue among South Africans, who are angry at the increasing solidification of government rot. What reforms are needed to put the country’s future back on a democratic, accountable, and service-oriented trajectory? … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “The Troubled Democratic Transitions of African Liberation Movements/

Les transitions démocratiques tourmentées des mouvements de libération africains,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 14 December 2017.

Zimbabwe’s recent political crisis has provided a lens into the challenges many African countries face in transitioning from their founding liberation movement political structures to genuine, participatory democracies.

Zimbabwe’s recent political crisis has provided a lens into the ongoing challenges many African countries face in transitioning from their founding liberation movement political structures to genuine, participatory democracies. While often a source of dynamism and reform in the early years, such movements may also foster stagnation and become an entrenched obstacle to power sharing and accountability. Legitimacy conferred by the struggle tends to foster a sense of entitlement to rule among liberation leaders and parties. As the euphoria of liberation subsides, mismanagement sets in, public confidence plummets, and opposition grows. Violence, in turn, becomes an increasingly frequent means for ensuring compliance. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “Solidarity in Peace and Security: The Nordic-African Partnership/

La solidarité en matière de paix et de sécurité: Le partenariat entre les pays nordiques et l’Afrique,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 29 November 2017.

Nordic countries’ decades-long peace and security engagement in Africa has centered on African interests, long-term partnerships, and building African capacity.

In June 2017, the 16th annual Africa-Nordic Dialogue convened in Abuja, Nigeria. That same month Norway hosted talks between the Government of South Sudan and its opposition, the first time the warring parties had met face-to-face since July 2016. In neighboring Finland, the Burundi government and its opponents were meeting behind the scenes in negotiations spearheaded by former Finnish President and anti-apartheid campaigner Martti Ahtisaari.

This confluence of events was not a one-off coincidence, but rather part of a long tradition of Nordic-African solidarity. The Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) have a history of engagement in Africa dating back to the struggles against colonialism and apartheid. Initially, the Nordic countries focused on supporting African liberation movements. This later expanded to address the challenges of governance, development, and human security, with a heavy focus on peacekeeping and peacebuilding.

Today, Nordic-African relations are built on the values of democracy, solidarity, and holistic African development. Much of the emphasis of the Nordic model of engagement has centered on building African capacity through long-term technical assistance. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “A Medley of Armed Groups Play on Congo’s Crisis/Une mosaïque de groupes armés tire parti des effets de la crise au Congo,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 25 September 2017.

The DRC’s political crisis has galvanized and revived many of the estimated 70 armed groups currently active in the country, making the nexus between political and sectarian violence by armed militias a key feature of the DRC’s political instability.

The legitimacy of the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in its peripheral regions has always been tenuous. Throughout the country’s history, the most vehement opposition to Kinshasa has frequently emerged from its most far-flung provinces, such as Kasai, Katanga, and the Kivus. Today, this fault line is being exacerbated by President Joseph Kabila’s decision to suspend elections and remain in office after the end of his constitutionally mandated term limit in December 2016.

In addition to triggering protests across many cities, the political crisis has revived and galvanized armed groups and militias in areas that harbor long-running grievances against the central government. Some insurgents have openly called on the President to step aside, even as their activities remain local. Others have expanded their attacks outside their traditional areas of operation in an apparent effort to exploit worsening grievances. Still others have focused their attacks on government personnel and facilities, including electoral commission offices, saying that preparations for new elections are meaningless as long as Kabila is a candidate.

In the DRC, the nexus between political and sectarian violence by armed militias is a key feature of political instability. This occurs in a climate of endemic corruption, weak or nonexistent institutions, and lack of trust between citizens and government. Nefarious actors thrive in this environment. This review highlights some of the patterns of violence by the estimated 70 armed groups active in the DRC—as uncertainty and anxiety over Kabila’s intentions intensify. … … …

***

Paul Nantulya, “The Costs of Regional Paralysis in the Face of the Crisis in Burundi/Les coûts de l’inaction régionale face à la crise au Burundi,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 24 August 2017.

Despite the serious humanitarian and economic tolls generated by Burundi’s crisis, the reaction of its neighbors has been remarkably subdued.

“Burundi’s troubles are costing the EAC hundreds of millions of dollars annually.”

In June 2017, the UN Commission of Inquiry on Burundi reported that atrocities were being committed on a massive scale. This includes extrajudicial executions, torture, sexual and gender-based violence, enforced disappearances, and mass graves. Many of the violations were accompanied by ethnic-based hate speech delivered by state and ruling party officials. Over 400,000 Burundians have taken refuge in neighboring countries, including 240,000 in Tanzania’s Nyarugusu camp, now the third largest in the world. The number of Burundian refugees is expected to exceed a half million by the end of this year, which would make Burundi the third largest source of refugees in sub-Saharan Africa.