Key China Excerpts from Big DIA Report: “Challenges to Security in Space: Space Reliance in an Era of Competition & Expansion”

Challenges to Security in Space: Space Reliance in an Era of Competition and Expansion (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence Agency, 2022).

Click here to download a cached copy.

p. iii

Challenges to Security in Space was first published in early 2019 to address the main threats to the array of U.S. space capabilities, and examine space and counterspace strategies and systems pursued primarily by China and Russia and, to a lesser extent, by North Korea and Iran. This second edition builds on that work and provides an updated, unclassified overview of the threats to U.S. space capabilities, particularly from China and Russia, as those threats continue to expand.

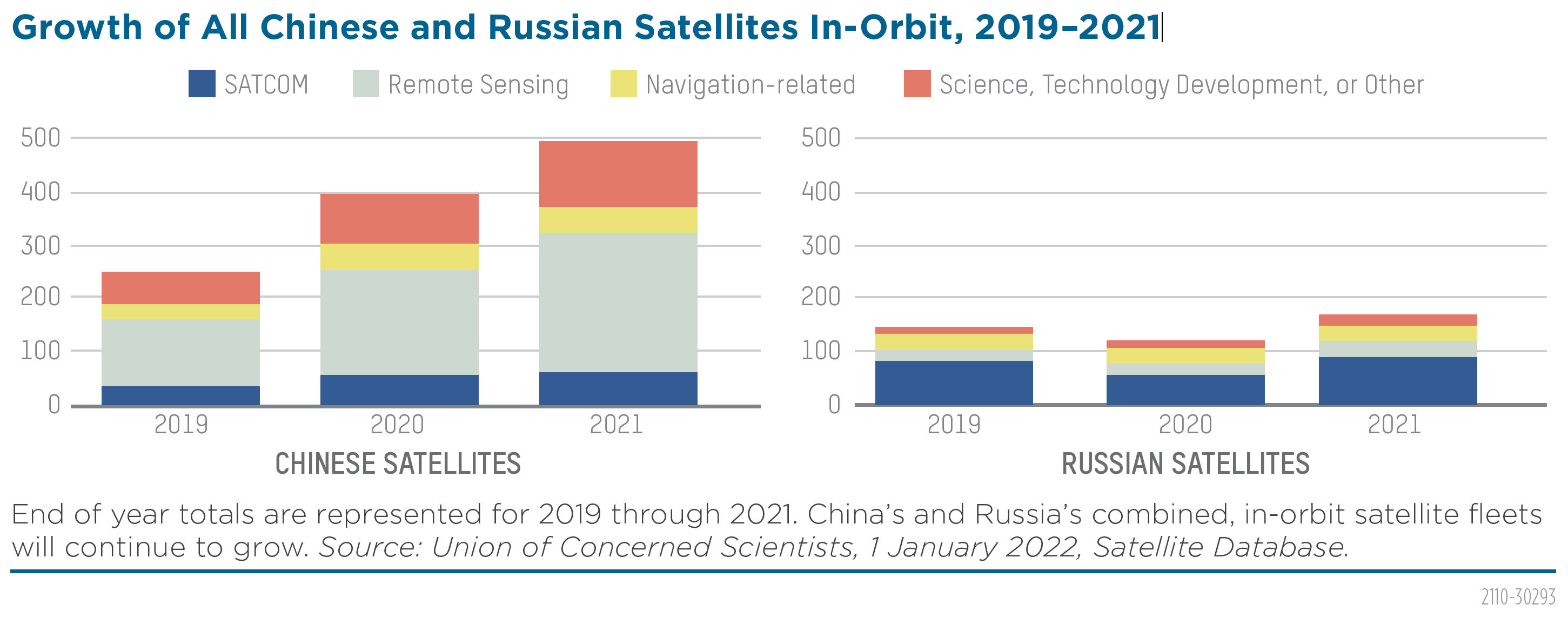

Between 2019 and 2021 the combined operational space fleets of China and Russia have grown by approximately 70 percent. This recent and continuing expansion follows a period of growth (2015–2018) where China and Russia had increased their combined satellite fleets by more than 200 percent. The drive to modernize and increase capabilities for both countries is reflected in nearly all major space categories—satellite communications (SATCOM), remote sensing, navigation-related, and science and technology demonstration.

Since early 2019, competitor space operations have also increased in pace and scope worldwide, China’s and Russia’s counterspace developments continue to mature, global space services proliferate, and orbital congestion has increased. As a result, DIA has published this new edition to:

- Expand its examination of competitor space situational awareness (SSA), and command and

control (C2) capabilities;

- Detail the profiles of organizations operating space and counterspace systems based on new information;

- Deepen our characterization of new space and counterspace systems deployed and in development;

- Focus on China’s and Russia’s interests in exploring the Moon and Mars;

- Provide a new section on the use of space beyond Earth orbit and its implications;

- Widen our treatment on the threats posed to all nations’ space operations from space debris.

pp. iv–v

Competition. Space competition between the United States and the former Soviet Union began in earnest with Moscow’s launch of the world’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik-1, in 1957. China’s emergence as a space power in the late 20th and early 21st century and Russia’s post-Soviet resurgence have expanded the militarization of space as both countries integrate space and counterspace capabilities into their national and warfighting strategies to challenge the United States. Adversaries have observed more than 30 years of U.S. military operations supported by space systems and are now seeking ways to expand their own capabilities and deny the U.S. a space-enabled advantage.1

China and Russia, in particular, are developing various means to exploit the perceived U.S. reliance on space-based systems and challenge the U.S. position in the space domain.2 Beijing and Moscow seek to position themselves as leading space powers, intent on creating new global space norms. Through the use of space and counterspace capabilities, they aspire to undercut U.S. global leadership. Iran and North Korea will continue to develop and operate electronic warfare (EW) capabilities to deny or degrade space-based communications and navigation.3

p. v

as the Global Positioning System (GPS). Beijing and Moscow have also created separate space forces. As China’s and Russia’s space and counterspace capabilities increase, both nations are integrating space scenarios into their military exercises. They continue to develop, test, and proliferate sophisticated antisatellite (ASAT) weapons to hold U.S. and allied space assets at risk. At the same time, China and Russia are pursuing nonweaponization of space agreements in the United Nations.9 Russia regularly expresses concern about space weapons and is pursuing legal, binding space arms control agreements to curb what it sees as U.S. strength in outer space.10,11 The expansion of Chinese and Russian space and counterspace weapons combined with the general rise of other foreign space capabilities is driving many nations to formalize their space policies to better position themselves to secure the space domain and facilitate their own space services.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25

p. 1

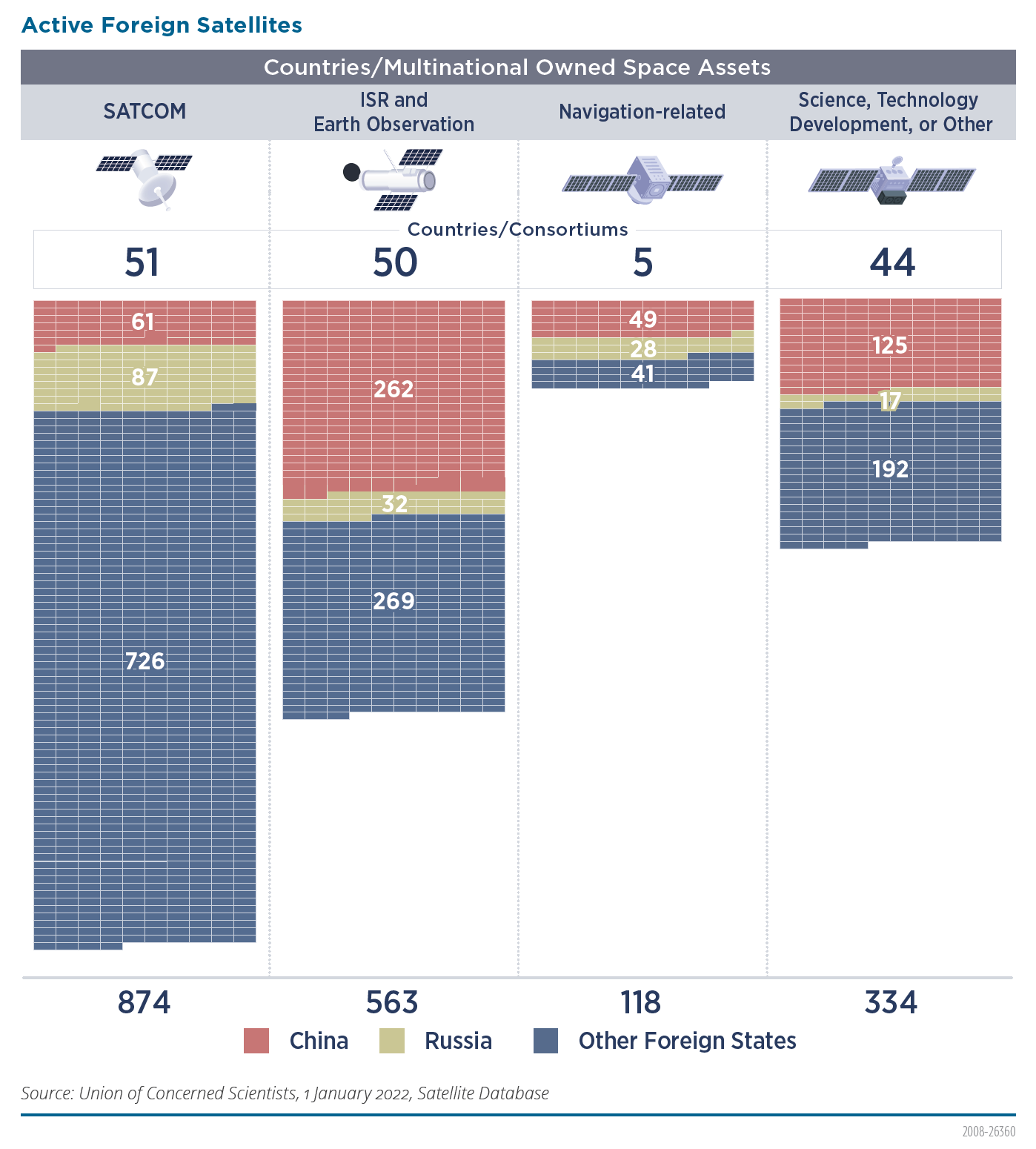

Exhibit: “Active Foreign Satellites”

p. 2

Space-based remote-sensing, communication, and navigation systems are used for various commercial, civilian, and military applications. Many nations, including China and Russia, have recognized the benefits of investing in and using space technologies.

p. 4

Adversary ASAT missiles can be used to attack satellites in LEO and would produce massive amounts of debris that can remain in orbit for decades or even centuries. China tested an ASAT missile against its own defunct weather satellite in 2007, which created a debris cloud that poses a threat to satellites in nearby orbits today.34 Russia used an ASAT missile as recently as 15 November 2021 to destroy one of its derelict satellites in orbit.35

p. 7

p. 8

CHINA

Exploring the vast universe, developing space programs, and becoming an aerospace power have always been the dream we have been striving for.

—Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, 24 April 2016, Remarks on the first China Space Day39

Space has already become a new domain of modern military struggle; it is a critical factor for deciding military transformation; and it has an extremely important influence on the evolution of future form-states, modes, and rules of war. Therefore, following with interest the military struggle circumstance of space and strengthening the study of the space military struggle problem is a very important topic we are currently facing.

—China’s Science of Military Strategy, 2020 National Defense University40

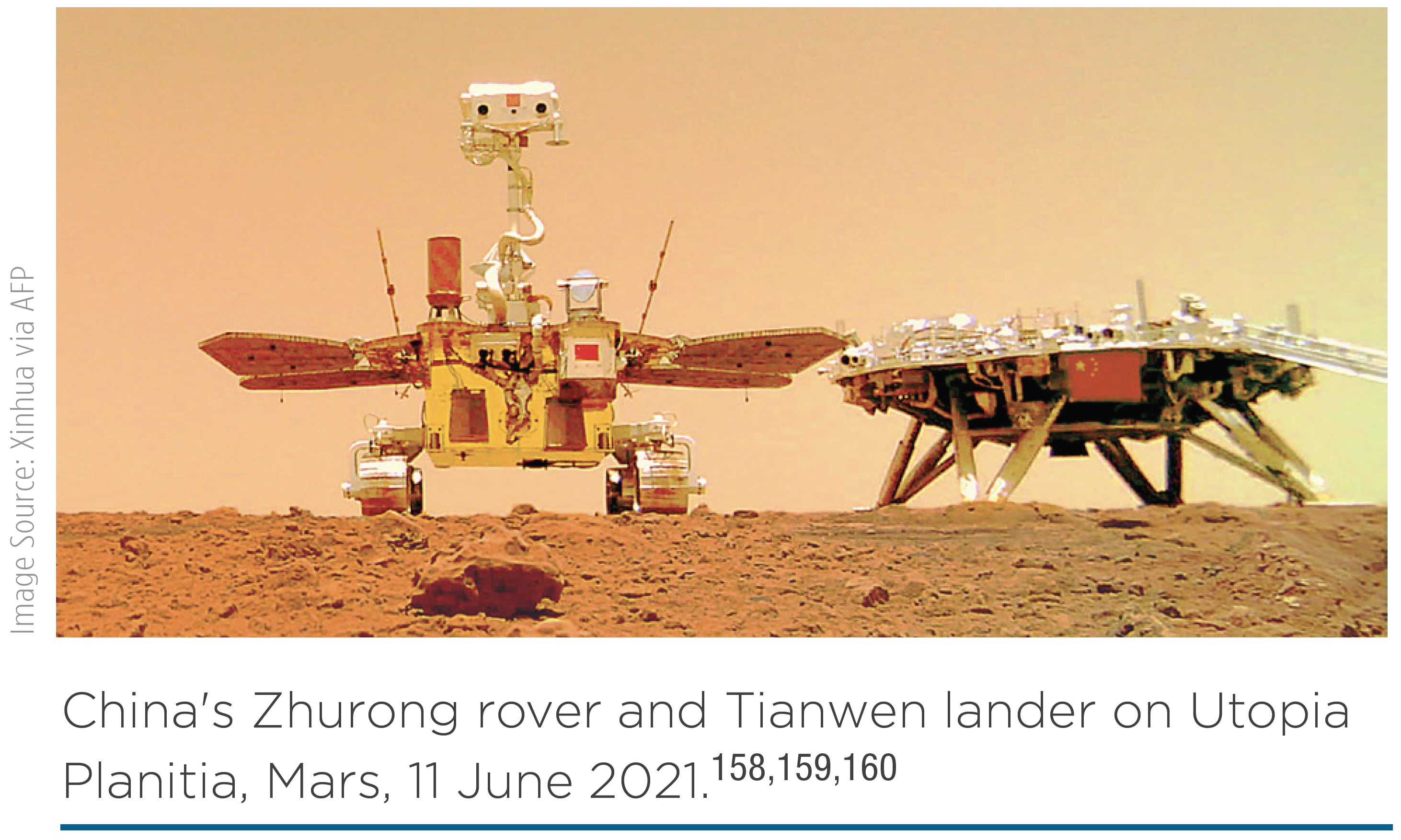

China has devoted considerable economic and technological resources to growing all aspects of its space program, improving military space applications, developing human spaceflight, and conducting lunar and Martian exploration missions.41 During the past 10 years, China has doubled its launches per year and the number of satellites in orbit.42,43 China has placed three space stations in orbit, two of which have since deorbited, and the third of which launched in 2021.44,45,46,47,48 Furthermore, China has launched a robotic lander and rover to the far side of the Moon;49 a lander and sample return mission to the Moon;50,51,52,53 and an orbiter, lander, and rover in one mission to Mars.54,55,56 China has also launched multiple ASAT missiles that are able to destroy satellites and developed mobile jammers to deny SATCOM and GPS.57,58,59,60,61,62,63

Beijing’s goal is to become a broad-based, fully capable space power.64 Its rapidly growing space program—second only to the United States in the number of operational satellites—is a source of national pride and part of Chairman Xi Jinping’s “China Dream” to establish a powerful and prosperous China. The space program, managed by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), supports both civilian and military interests, including strengthening its science and technology sector, growing international relationships, and modernizing the military. China seeks to rapidly achieve these goals through advances in the research and development of space systems and space-related technology.65,66,67,68,69

China will continue to launch a range of satellites that substantially enhance its ISR capabilities; field advanced communications satellites able to transmit large amounts of data; increase PNT capabilities; and deploy new weather and oceanographic satellites.70 China has also developed and probably will continue to develop weapons for use against satellites in orbit to degrade and deny adversary space capabilities.71,72,73

p. 9

Military Strategic Guidelines

In 2015, Beijing’s official release of China’s Military Strategy directed the PLA to research and give priority to strategies to win “informatized local wars” and emphasized “maritime military struggle.”74 Chinese military strategy documents also emphasize the growing importance of offensive air, long-distance mobility, and space and cyberspace operations. China expects its future wars to be fought mostly outside its borders and in the maritime domain. China promulgated its military strategy and the supporting documents through its most recent update to its military strategic guidelines, the top-level directives that Beijing uses to define concepts, assess threats, and set priorities for planning, force posture, and modernization.75

The PLA uses “informatized warfare” to describe the process of acquiring, transmitting, processing, and using information to conduct joint military operations across the land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace domains and the electromagnetic spectrum during a conflict. PLA writings guide much of China’s military modernization today and highlight the benefit of near-real-time shared awareness of the battlefield in enabling quick, unified efforts to seize tactical opportunities. In November 2020, China’s Central Military Commission issued a trial update to PLA joint doctrine to codify warfighting reforms and will almost certainly improve its ability to conduct joint operations.76 Space-based systems will play an increasingly important role in support of these goals.77

Space Strategy and Doctrine

China officially advocates for the peaceful use of space and is pursuing agreements in the United Nations on the nonweaponization of space.78 China also continues to improve its counterspace weapons capabilities and has enacted military reforms to better integrate cyberspace, space, and EW into joint military operations. China’s space strategy is expected to evolve over time, keeping pace with the application of new space technology. These changes probably will be reflected in published national space strategy documents, through space policy actions, and in programs enacted by political and military leadership.

The PLA views space superiority, the ability to control the space-enabled information sphere and to deny adversaries their own space-based information gathering and communication capabilities, as a critical component to conduct modern “informatized warfare.”79,80,81,82 China’s first public mention of space and counterspace capabilities came as early as 1971, largely from academics reviewing foreign publications on ASAT technologies. However, Chinese science and technology efforts on space began to accelerate in the 1980s, most likely as a result of the U.S. space-focused Strategic Defense Initiative to defend against the former Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons.83 Subsequently, after observing the U.S. military’s performance during the 1991 Gulf War through actions in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and the second Iraq War, the PLA embarked on an effort to modernize weapon systems, across all domains including space, and update its doctrine to focus on using and countering adversary information-enabled warfare.84

China’s perceptions of the importance of space-enabled operations to the United States and its allies has shaped integral components of PLA military planning and campaigns. In addition, space is a critical enabler of beyond-line-of-sight operations for deployed Chinese forces, and the PLA probably sees counterspace operations as a means to deter and counter a U.S. intervention during a regional military conflict.85,86 China has claimed that “destroying or capturing satellites and other sensors” would make it difficult for the U.S. and allied militaries to use precision-guided weapons.87 Moreover, Chinese defense academics suggest that reconnaissance, communication, navigation, and early warning satellites could be among the targets of attacks designed to “blind and deafen the enemy.”88

p. 10

Space and Counterspace Organizations

China’s space program comprises organizations in the military, political, defense-industrial, and commercial sectors. The PLA historically has managed China’s space program and continues to invest in improving China’s capabilities in space-based ISR, SATCOM, satellite navigation, human spaceflight, and robotic space exploration.89 Although state-owned enterprises are China’s primary civilian and military space contractors, China is placing greater emphasis on decentralizing and diversifying its space industry to increase competition.90

In 2015, China established the Strategic Support Force (SSF) to integrate cyberspace, space, and EW capabilities into joint military operations as part of its military reforms.91,92,93 The SSF forms the core of China’s information warfare force, supports the entire PLA, and reports directly to the Central Military Commission.

The SSF, led by PLA General Ju Qiansheng,94 is divided into two major departments: the Space Systems Department (SSD), very likely consolidating the majority of the PLA’s space functions, and the Network Systems Department (NSD), very likely in charge of cyberspace operations and EW.95,96 The SSD focuses primarily on satellite launches and operations to support ISR, navigation, and communication requirements.97 The SSD’s China Launch and Tracking Control (CLTC) operates all four launch sites, in addition to Yuanwang space support ships, two major satellite control centers—Xian Satellite Control Center (XSCC) and the BACC— and the PLA telemetry, tracking, and control (TT&C) system for all Chinese satellites.98,99 The EW functions of the PLA before 2015 were probably transferred to the NSD when it was stood up in 2015 as well.100,101

The State Council’s State Administration for Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND) is the primary civilian organization that coordinates and manages China’s space activities, including allocating space research and development funds.102 It also maintains a working relationship with the PLA organization that oversees China’s military acquisitions. SASTIND guides and establishes policies for state-owned entities conducting China’s space activities.103

The China National Space Administration (CNSA), subordinate to SASTIND, serves as the public face of China’s civilian space efforts.104 China is increasingly using CNSA efforts to bolster relationships with countries around the world, providing opportunities to cooperate on space issues.105,106,107 As of 2019, China had more than a hundred cooperative space-related agreements with more than three dozen countries and four international organizations.108,109

Many space technologies can serve a civilian and military purpose and China emphasizes “military-civil fusion”—a phrase used, in part, to refer to the use of dual-use technologies, policies, and organizations for military benefit.110 The SSF works with civilian organizations like universities and research organizations to incorporate civilian support to military efforts since there is an already high demand for aerospace talent and competition for finite human resources.111 China’s commercial space sector features partially state-owned enterprises such as Zhuhai Orbita, Expace, Galactic Energy, and OK-Space for remote sensing, launch, and communication services.112,113,114,115

Acquisition of Foreign Space and Counterspace Technologies

The PLA continues to rely on overt and covert acquisition of foreign space and counterspace technologies to build Chinese knowledge and advance technological modernization as a supplement to its domestic research. China uses traditional technical espionage and cyberespionage techniques as well as its open-source collection network, technology transfer organizations, and exploitation of overseas scholars. Acquisition of foreign technology is used

p. 11

to circumvent the costs of research and facilitate “leapfrog” development by exploiting the creativity of other nations.116

ISR Satellite Capabilities

China employs a robust space-based ISR capability designed to enhance its worldwide situational awareness. Used for military and civilian remote sensing and mapping, terrestrial and maritime surveillance, and intelligence collection, China’s ISR satellites are capable of providing electro-optical and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery as well as electronic and signals intelligence data.117 China also exports its satellite technology globally, including its domestically developed remote-sensing satellites.

As of January 2022, China’s ISR satellite fleet contained more than 250 systems—a quantity second only to the United States, and nearly doubling China’s in-orbit systems since 2018.118,119 The PLA owns and operates about half of the world’s ISR systems, most of which could support monitoring, tracking, and targeting of U.S. and allied forces worldwide, especially throughout the Indo-Pacific region. These satellites also allow the PLA to monitor potential regional flashpoints, including the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, Indian Ocean, and the South China Sea.120,121,122

Recent improvements to China’s space-based ISR capabilities emphasize the development, procurement, and use of increasingly capable satellites with digital camera technology as well as space-based radar for all-weather, 24-hour coverage. These improvements should increase China’s monitoring capabilities—including observation of U.S. aircraft carriers, expeditionary strike groups, and deployed air wings, making them more susceptible to long-range strikes. Space capabilities probably will enhance potential PLA military operations farther from the Chinese coast.123,124,125,126 These capabilities are being augmented with electronic reconnaissance satellites that monitor radar and radio transmissions.127

Satellite Communications

China owns and operates more than 60 communications satellites, at least 4 of which are dedicated to military use.128 China produces its military-dedicated satellites domestically. Its civilian communications satellites incorporate off-the-shelf commercially manufactured components.129 China is fielding advanced communications satellites capable of transmitting large amounts of data.130 Existing and future data relay satellites and other beyond-line-of-sight communications systems could convey critical targeting data to Chinese military operation centers.131,132,133

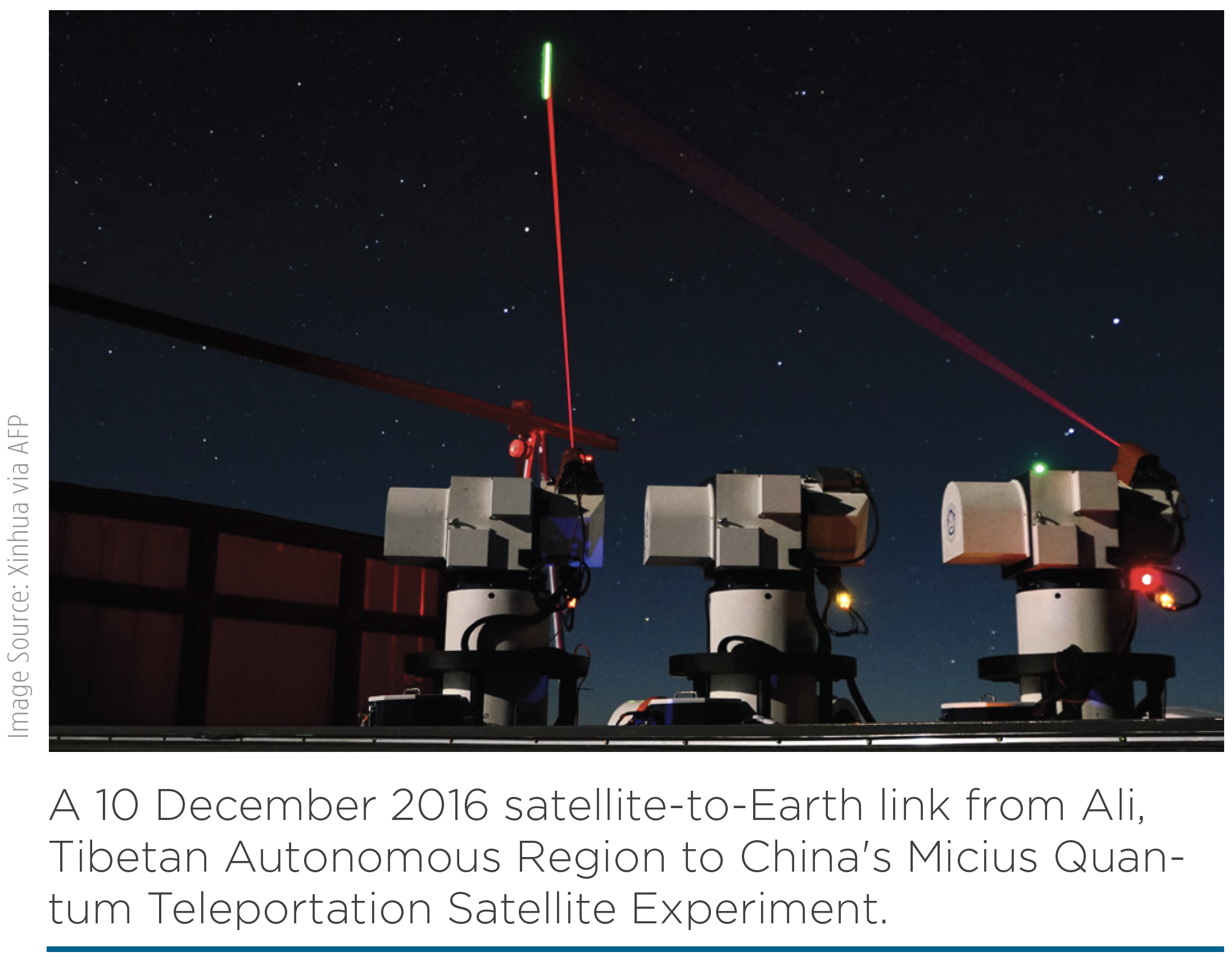

In addition, China is making progress on its ambitious plans to propel itself to the forefront of the global SATCOM industry.134,135,136 China is continuing to test next-generation capabilities like its Quantum Experimentation at Space Scale (QUESS) space-based quantum-enabled communications satellite, which could supply the means to field highly secure communications systems.137,138 In June 2020, a team of Chinese scientists claimed to achieve quantum supremacy, reporting successful satellite-based distributions of entangled photon pairs at a distance of more than 1,200 kilometers and that the photon pairs’ integrity remained intact after traveling such distances. Testing satellite-based quantum entan-

p. 12

glement represents a major milestone in building a practical, global, ultrasecure quantum network, but the widespread deployment and adoption of this technology still faces hurdles.139,140 China also intends to provide SATCOM support to users worldwide and plans to develop at least seven new SATCOM constellations in LEO. However, as these constellations are still in the early stages of development their effectiveness remains uncertain.141,142,143,144,145

PNT Capabilities

China’s satellite navigation system, known as Bei-Dou, is an independently constructed, developed, and exclusively China-operated PNT service. China’s priorities for BeiDou are to support national security and economic and social development by adopting Chinese PNT into precise agriculture, monitoring of vehicles and ships, and aiding with civilian-focused services across more than 100 countries in Africa, Asia, and Europe.146,147 BeiDou provides all-time, all-weather, and high-accuracy PNT services to users domestically, in the Asia-Pacific region, as well as globally and consists of 49 operational satellites.148,149,150,151,152,153,154 Initially deployed to facilitate regional PNT services, BeiDou achieved worldwide initial operating capability in 2018.155,156 In June 2020, China successfully launched the final satellite in the BeiDou satellite constellation, completing its global navigation system.157 China’s military uses BeiDou’s high-accuracy PNT services to enable force movements and precision-guided munitions delivery.161,162

BeiDou has a worldwide positional accuracy standard of 10 meters; accuracy in the Asia-Pacific region is within 5 meters.163 In addition to providing PNT, the BeiDou constellation offers unique capabilities, including text messaging and user tracking through its Regional Short Message Communication service to enable mass communications among BeiDou users. The system also provides additional military C2 capabilities for the PLA.164,165,166 China intends to use its BeiDou constellation to offer additional services and incentives to countries taking part in its Belt and Road Initiative emphasizing building strong economic ties to other countries to align partner nations with China’s interests.167,168 As of May 2021, China is predicting Beidou products and services will be worth $156 billion by 2025, and potentially export BeiDou products to more than 100 million users in 120 countries.169

Human Spaceflight and Space Exploration

Following uncrewed missions that began in 1999, China became the third country to achieve independent human spaceflight when it successfully orbited the crewed Shenzhou-5 spacecraft in 2003.170,171,172 In 2011, China then launched its first space station, Tiangong-1, and in 2016, it launched its second space station, Tiangong-2.173,174,175 In 2020, China conducted its first orbital test of the New-Generation Manned Spaceship, which is expected to replace the Shenzhou series of crewed spacecraft.176 On 29 April 2021, China launched the first element, Tianhe, of its new Tiangong space station.177 Beijing launched the first supply vessel, Tianzhou, and has launched two Chinese crews since then.178,179

China has also taken on a greater role in deep space exploration and space science and has made notable accomplishments during the past several years. China has demonstrated its interest in working with Russia and the European Space Agency (ESA) to con-

p. 13

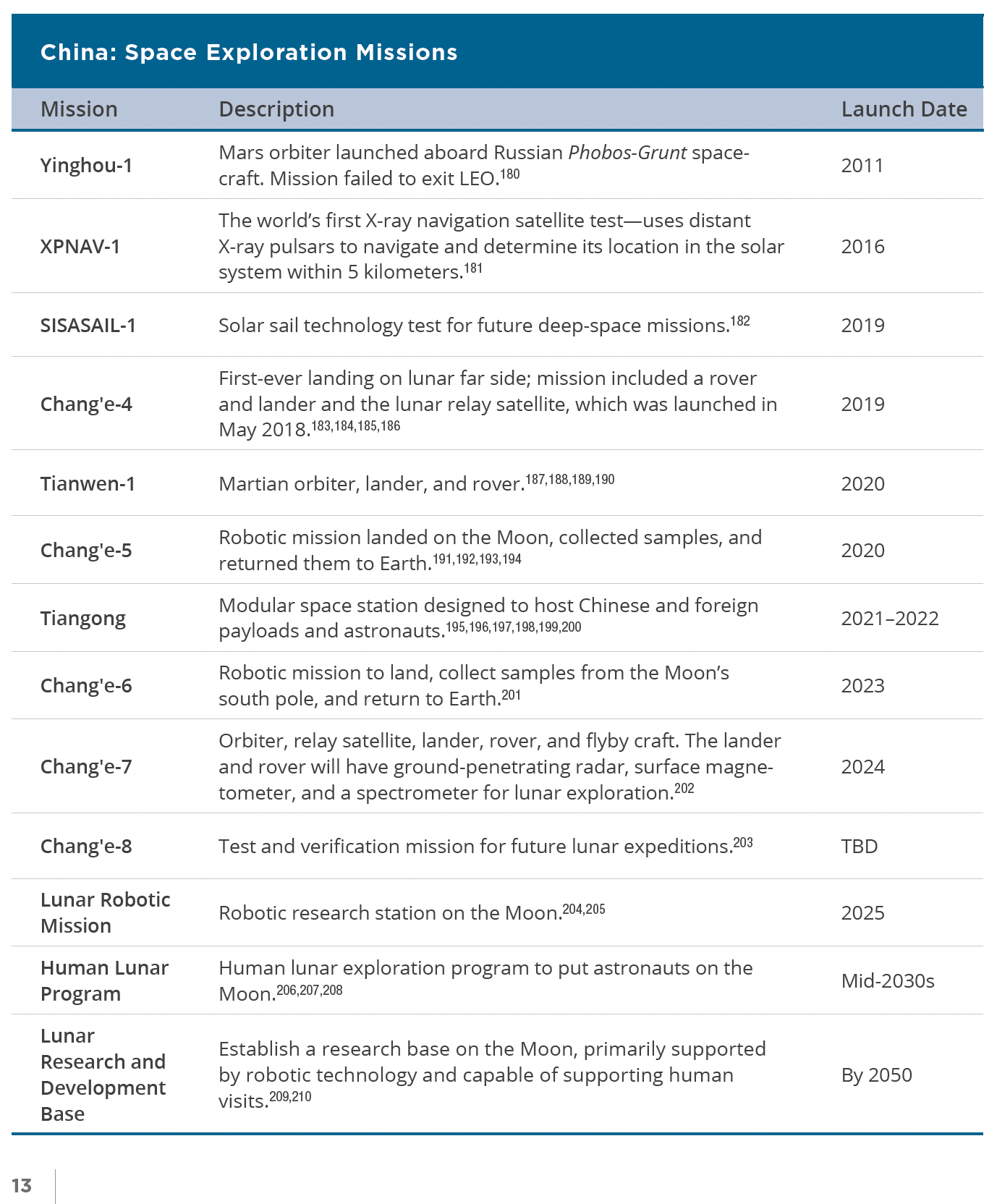

Exhibit: “China: Space Exploration Missions”

p. 14

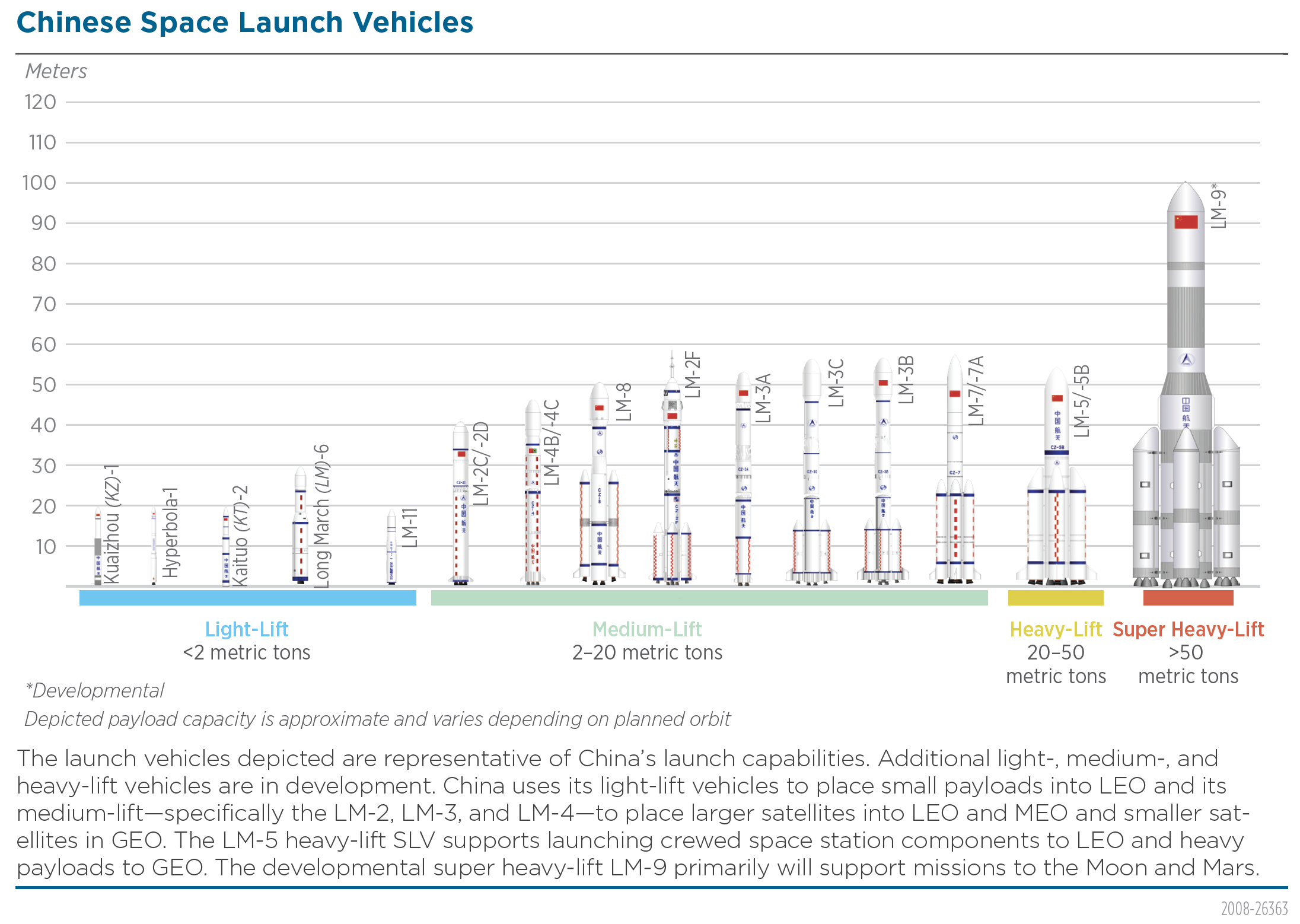

Exhibit: “Chinese Space Launch Vehicles”

duct deep-space exploration.211,212 China is the third country to place a robotic rover on the Moon and was the first to land a rover on the lunar far side in 2019, which is communicating through the Queqiao relay satellitethat China launched the year before to a stable orbit around an Earth-Moon Lagrange point [See Cislunar Chart, page 35].213,214

Space Launch Capabilities

China is improving its space launch capabilities to ensure it has an independent, reliable means to access space and to compete in the international space launch market. China continues to improve manufacturing efficiencies and launch capabilities overall, supporting continued human spaceflight and deep-space exploration missions—including to the Moon and Mars.215 New modular SLVs that allow China to tailor an SLV to the specific configuration required for each customer are beginning to go into operation, leading to increased launch vehicle reliability and overall cost savings for launch campaigns.216 China is also in the early stages of developing a super heavy-lift SLV similar to the U.S. Saturn V or the newer U.S. Space Launch System to support proposed crewed lunar and Mars exploration missions.217

In addition to land-based launches, in 2020 China demonstrated the ability to launch a Long March-11 (LM-11) from a sea-based platform. This capability, if staged correctly, would allow China to launch nearer to the equatorthan its land-based launch

p. 15

sites, increase the rocket’s carrying capacity, and potentially lower launch costs.218

China has developed quick-response SLVs to increase its attractiveness as a commercial small satellite launch provider and to rapidly reconstitute LEO space capabilities, which could support Chinese military operations during a conflict or civilian response to disasters. Compared with medium- and heavy-lift SLVs, these quick-response SLVs are able to expedite launch campaigns because they are transportable via road or rail and can be stored launch-ready with solid fuel for longer periods than liquid-fueled SLVs. Because their size is limited, quick-response SLVs such as the Kuaizhou-1 (KZ-1), LM-6, and LM-11 are only able to launch relatively small payloads of up to approximately 2 metric tons into LEO.

Exhibit: “Chinese Space Launch, SSA, Satellite Control Centers, Command and Control, and Data Reception Stations”

p. 16

In June 2020, China announced its intention to upgrade the payload capacity of the LM-11 in the new LM-11A, designed for land or sea launches, beginning in 2022.221,222,223,224

The expansion of nonstate-owned Chinese launch vehicle and satellite operation companies in China’s domestic market since 2015 suggests that China is successfully advancing military-civil fusion efforts. Military-civil fusion blurs the lines between these entities and obfuscates the end users of acquired foreign technology and expertise.225

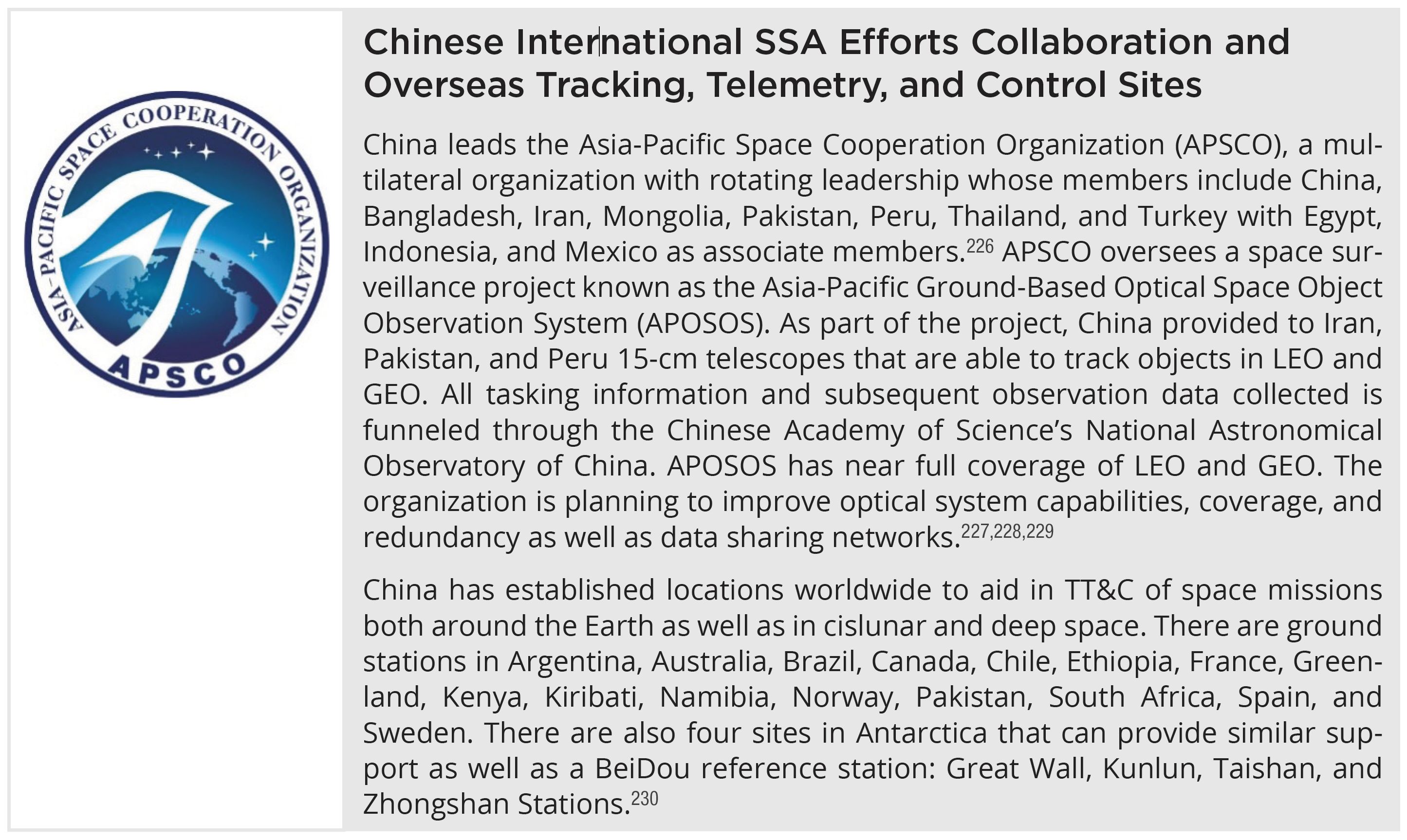

Space Situational Awareness

China has a robust network of space surveillance sensors capable of searching, tracking, and characterizing satellites in all Earth orbits. This network includes a variety of telescopes, radars, and other sensors that allow China to support its missions including intelligence collection, counterspace targeting, ballistic missile early warning

p. 17

(BMEW), spaceflight safety, satellite anomaly resolution, and space debris monitoring.231,232

Electronic Warfare Capabilities

The PLA considers EW capabilities to be critical assets for modern warfare, and its doctrine emphasizes using EW to suppress or deceive enemy equipment.233 The PLA routinely incorporates in its exercises jamming and antijamming techniques that probably are intended to deny multiple types of space-based communications, radar systems, and GPS navigation support to military movement and precision-guided munitions employment.234 China probably is developing jammers dedicated to targeting SAR, including aboard military reconnaissance platforms. Interfering with SAR satellites very likely protects terrestrial assets by denying imagery and targeting in any potential conflict involving the United States or its allies.235,236 In addition, China probably is developing jammers to target SATCOM over a range of frequency bands, including military-protected extremely high frequency communications.237,238

Cyberthreats

The PLA emphasizes offensive cyberspace capabilities as a major component of integrated warfare and could use its cyberwarfare capabilities to support military operations against space-based assets.239,240 For example, the PLA could employ its cyberattack elements to establish information dominance in the early stages of a conflict to constrain an adversary’s actions or slow its mobilization and deployment by targeting network-based command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR); logistics; and commercial activities.

The PLA also conducts cyberespionage against foreign space entities, consistent with broader state-sponsored industrial and technical espionage, to increase its level of technologies and expertise available to support military research, development, and acquisition. The PLA unit responsible for conducting signals intelligence has supported cyberespionage against U.S. and European satellite and aerospace industries since at least 2007.241,242

Directed Energy Weapons

During the past two decades, Chinese defense research has proposed the development of several reversible and nonreversible counterspace DEWs for reversible dazzling of electro-optical sensors and even potentially destroying satellite components. China has multiple ground-based laser weapons of varying power levels to disrupt, degrade, or damage satellites that include a current limited capability to employ laser systems against satellite sensors.243By the mid- to late-2020s, China may field higher power systems that extend the threat to the structures of nonoptical satellites.244,245,246,247,248

ASAT Missile Threats

In 2007, China destroyed one of its defunct weather satellites more than 800 kilometers above the Earth with an ASAT missile. The effect of this destructive test generated more than 3,000 pieces of trackable space debris, of which more than 2,700 remain in orbit and most will continue orbiting the Earth for decades.249,250 The PLA’s operational ground-based ASAT missile system is intended to target LEO satellites. China’s military units have continued training with ASAT missiles.251,252

China probably intends to pursue additional ASAT weapons that are able to destroy satellites up to GEO. In 2013, China launched an object into space on a ballistic trajectory with a peak orbital radius above 30,000 kilometers, near GEO altitudes. No new satellites were released from the object, and the launch profile was inconsistent with traditional

p. 18

SLVs, ballistic missiles, or sounding rocket launches for scientific research, suggesting a basic capability could exist to use ASAT technology against satellites at great distances and not just LEO.253,254

Orbital Threats

China is developing other sophisticated space-based capabilities, such as satellite inspection and repair. At least some of these capabilities could also function as a weapon. China has launched multiple satellites to conduct scientific experiments on space maintenance technologies and is conducting research on space debris cleanup; the most recent launch was the Shijian-21 launched into GEO in October 2021.255,256,257 In January 2022, Shijian-21 moved a derelict BeiDou navigation satellite to a high graveyard orbit above GEO.258 The Shijian-17 is a Chinese satellite with a robotic arm. Space-based robotic arm technology could be used in a future system for grappling other satellites.259

Since at least 2006, the government-affiliated academic community in China began investigating aerospace engineering aspects associated with space-based kinetic weapons—generally a class of weapon used to attack ground, sea, or air targets from orbit. Space-based kinetic weapons research included methods of reentry, separation of payload, delivery vehicles, and transfer orbits for targeting purposes.260,261,262,263,264,265 China conducted the first fractional orbital launch of an ICBM with a hypersonic glide vehicle from China on 27 July 2021. This demonstrated the greatest distance flown (~40,000 kilometers) and longest flight time (~100+ minutes) of any Chinese land attack weapons system to date.26

p. 34

KEY SPACE ISSUES THROUGH 2030 AND BEYOND

Growth of Reusable Space Technology: Commercial Opportunities and Military Advantage

… The state-owned enterprise, China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, modified the LM-8—launched for the first time on 22 December 2020—into an R-SLV.562 The Chinese company, i-Space, plans to launch the country’s first commercially developed R-SLV, called Hyperbola-2, in late-2021, but a Hyperbola-1 failure probably delayed that launch.563,564 China is also developing two partially reusable capsules: the New-Generation Manned Spaceship intended to replace the Shenzhou capsule, and the New-Generation Reusable Recoverable Satellite as an inexpensive platform for microgravity experiments and rapid space equipment testing.565,566 …

Space planes are another form of reusable technology. Space planes also feature enhanced maneuverability, making them uniquely suitable for certain missions as compared with traditional satellites. Developing a space plane requires overcoming the obstacles of hypersonic flight, a rarified atmospheric environment, and extreme external heating. China has developed hypersonic glide vehicles for ballistic missile warhead delivery probably enabling further achievements in space application.570 China is developing the Shenlong and Tengyun space planes. In 2020, China launched into orbit its first-ever prototype of a space plane, which stayed in orbit for 2 days before returning to Earth. Beijing stated its space plane was testing reusable spacecraft technologies as part of advancing the peaceful use of space.571,572 The Shenlong program previously conducted a drop test as early as 2011, and Tengyun has only completed a model wind tunnel test.573,574 …

p. 37

Challenge to Space Operations: Debris and Orbital Collisions

… Prior to 2007, most debris came from explosions of upper stages of SLVs. Today, nearly one half of all cataloged debris are fragments from three major events: China’s destruction of its own defunct weather satellite in 2007, the accidental collision between a U.S. communications satellite and a dead Russian satellite in 2009, and the 2021 Russian Nudol ASAT test.599,600 …

p. 40

OUTLOOK

… China and Russia value superiority in space. As a result, they will seek ways to strengthen their space and counterspace programs, and determine ways to better integrate them into their respective militaries. Both nations are also seeking to broaden their space exploration initiatives—together and individually—outside Earth’s orbit with plans to explore the Moon and Mars during the next 30 years. Lunar exploration by China and Russia aims to expand their scientific knowledge and prestige. If successful, it will likely lead to attempts by China and Russia to exploit the Moon’s natural resources. …