Sarah Kirchberger, Svenja Sinjen, and Nils Wörmer, eds., Russia-China Relations: Emerging Alliance or Eternal Rivals? (New York, NY: Springer, 2022).

Click here to access full-text PDF.

This open access book examines Russia-China relations across a variety of civilian and military areas of cooperation. It provides an up-to-date assessment of strategic cooperation fields between China and Russia; examines the potential military-strategic impact of a Russian-Chinese alliance for NATO; and distills expertise on technical, military, economic and political aspects of Chinese-Russian cooperation. The contributing authors, leading experts in the field, present empirical case studies covering a wide range of strategic cooperation areas. They shed new light on Chinese and Russian strategic goals, external push and pull factors, and mutual perception shifts; and discuss the options for Western countries to influence this development. This book analyses the evolution of the relationship since the watershed moment of the Crimean crisis in 2014, and whether or not a full-blown military alliance, as hinted in late 2020 by President Putin, is indeed a realistic scenario for which NATO will have to prepare. It will appeal to students and scholars of international relations, political decision-makers, as well as anyone interested in Eurasian politics and the potential military-strategic impact of a Russian-Chinese alliance for NATO.

ABOUT THE EDITORS

Sarah Kirchberger is Head of Asia-Pacific Strategy & Security at the Institute for Security Policy at Kiel University (ISPK), a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, and Vice President of the German Maritime Institute (DMI). She was previously an Assistant Professor of Sinology at Hamburg University and a naval analyst with the shipbuilder TKMS.

Svenja Sinjen is Head of Science Communication at the Foundation for Science and Democracy (SWuD), Germany, and an editor at the journal SIRIUS. In addition, she leads SWuD’s Project “Global Transformation & German Foreign Policy.” Previously, she was Head of the Program ‘Future Forum Berlin’ at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP).

Nils Wörmer is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s International Politics and Security Affairs Department (KAS), Germany. He was previously in charge of the foundation’s Syria and Iraq office, which was established under his management in 2015. From 2013 to 2015, Nils Wörmer led the Afghanistan program of KAS in Kabul.

OF PARTICULAR INTEREST—The Military Dimension of Sino-Russian Cooperation: Case Studies

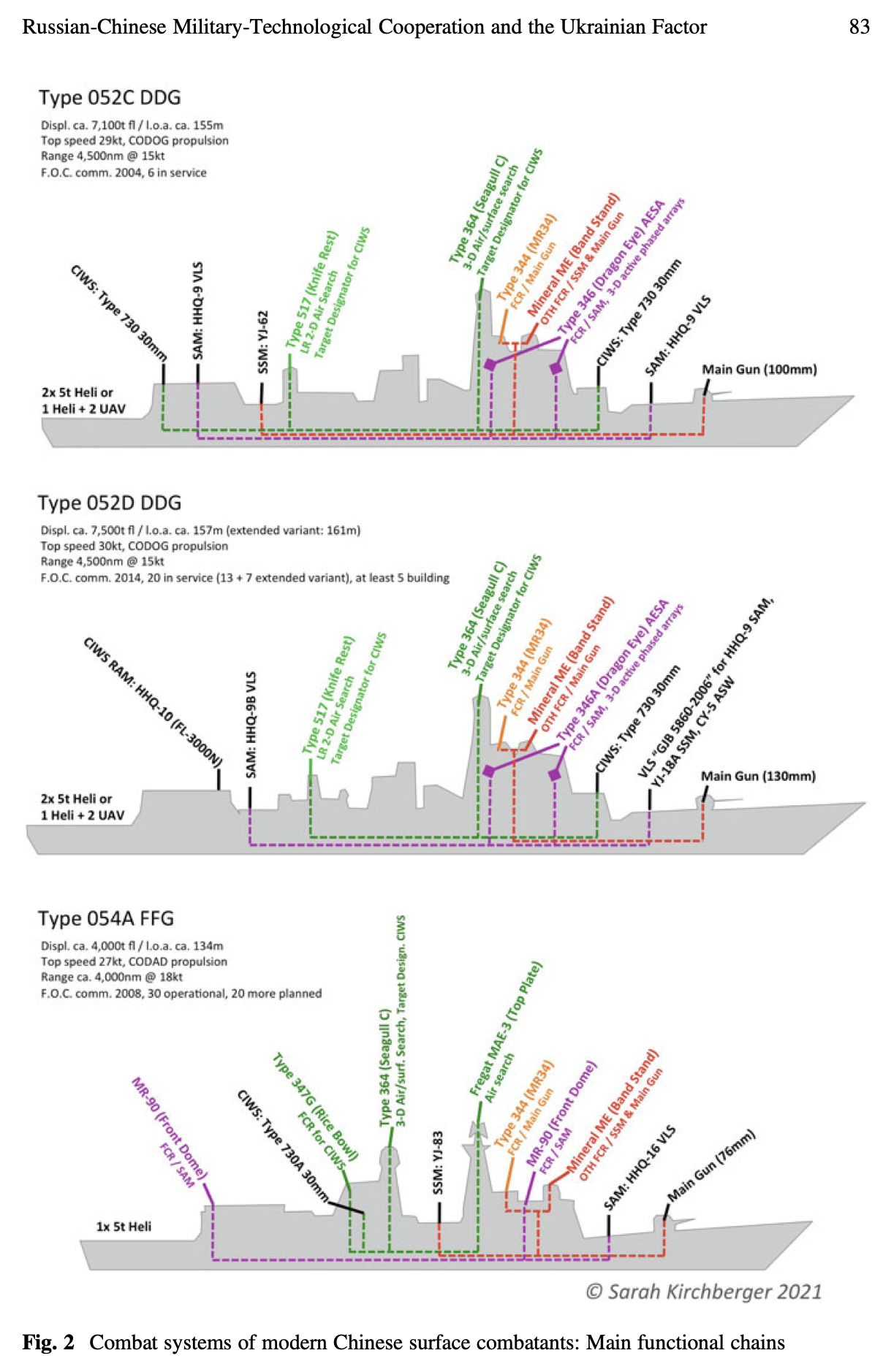

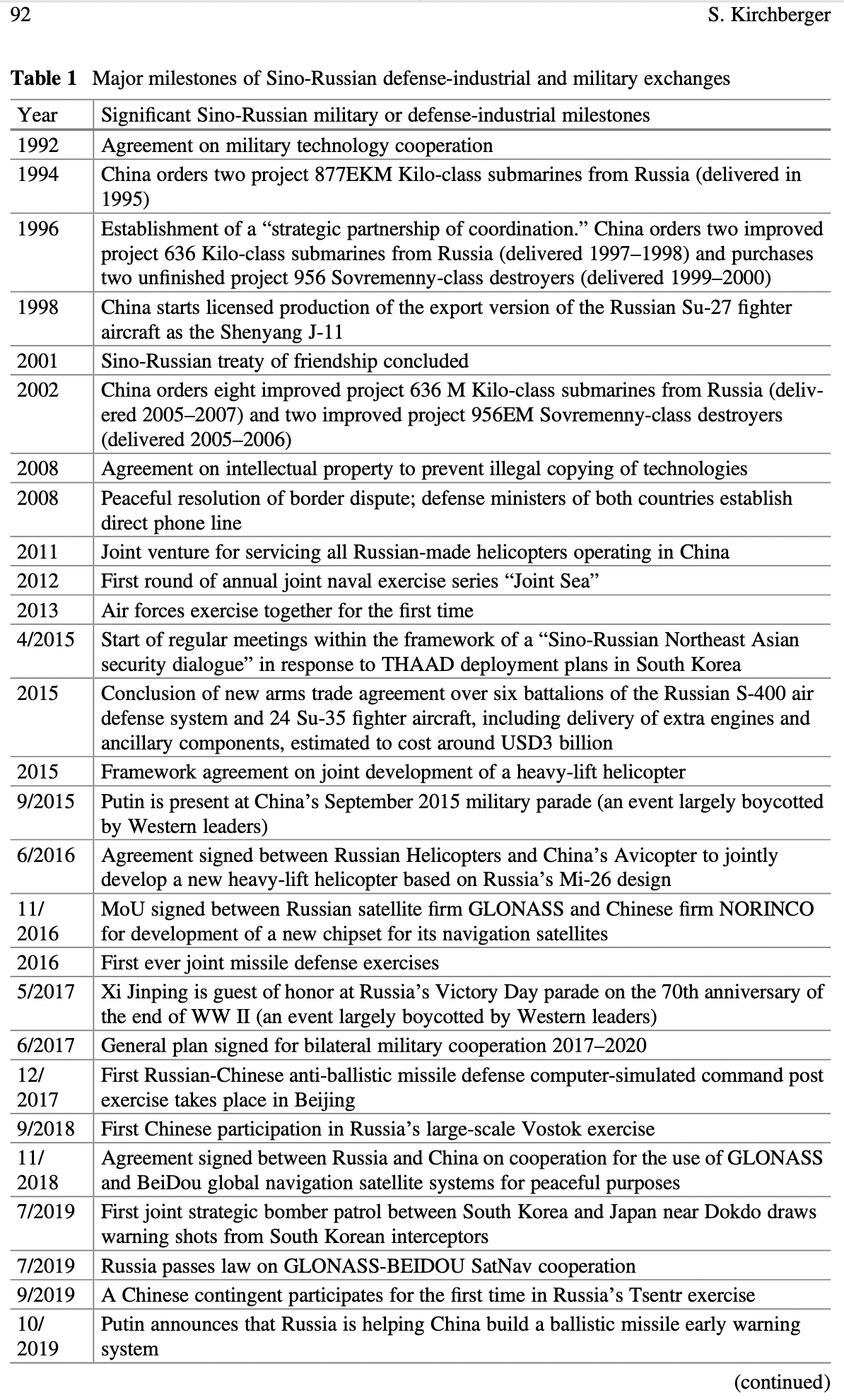

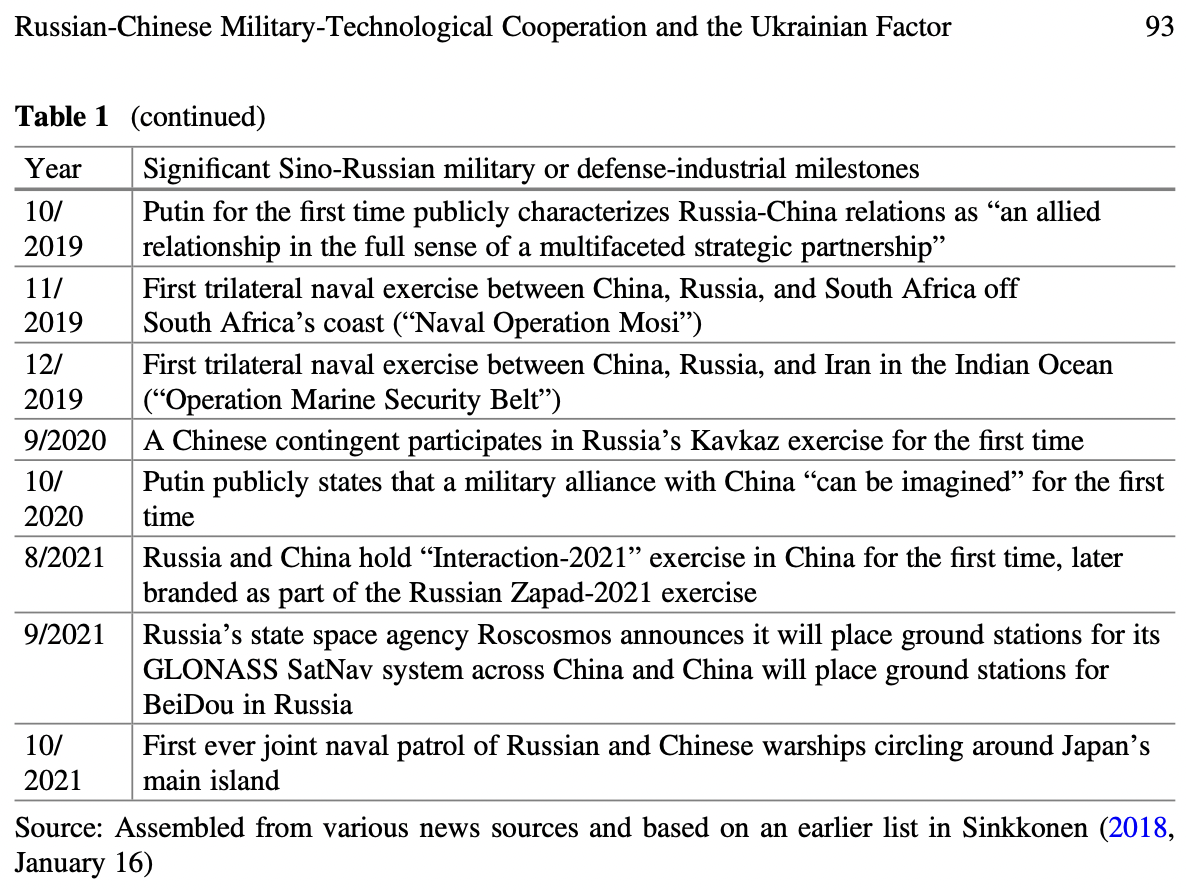

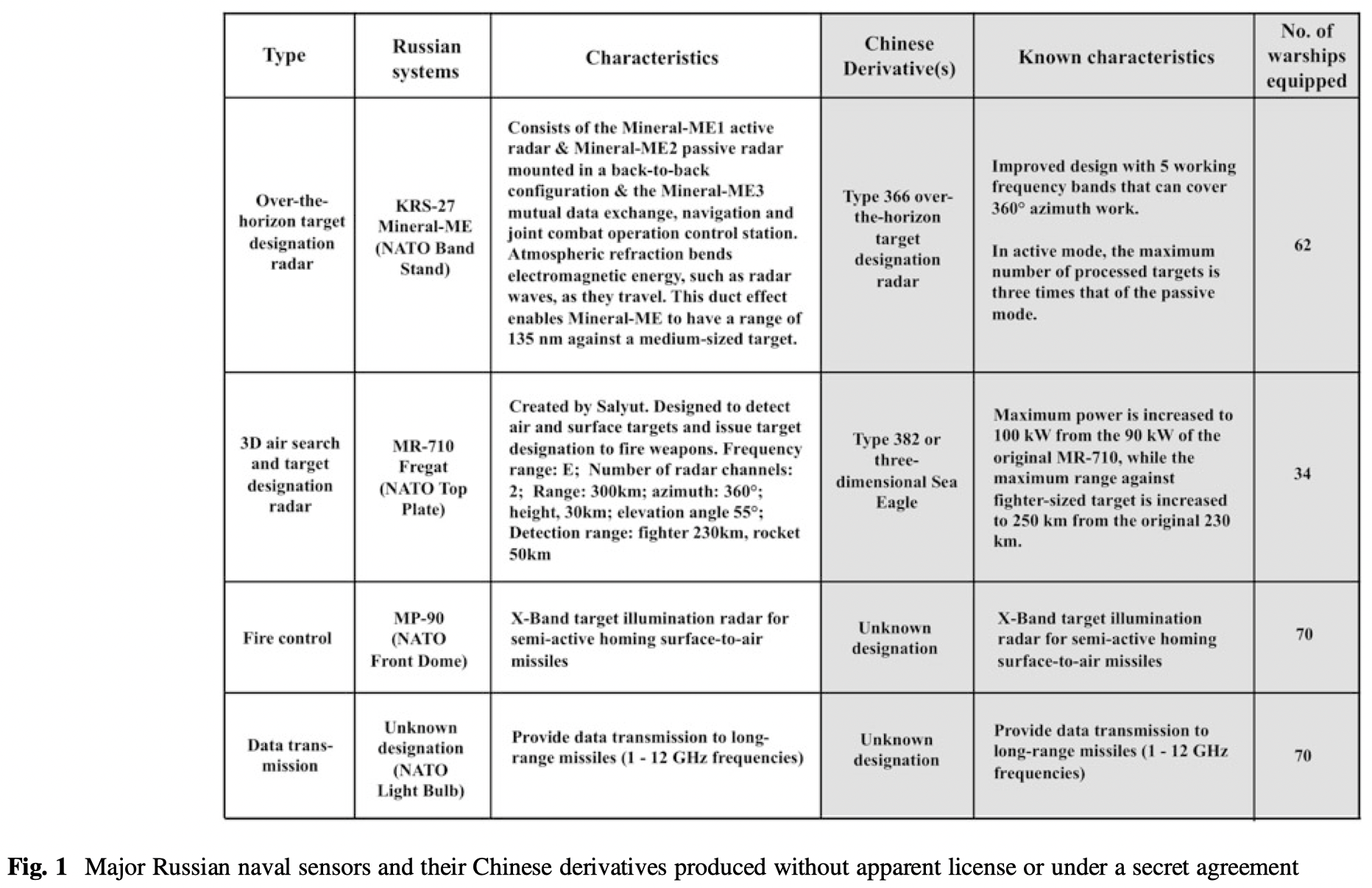

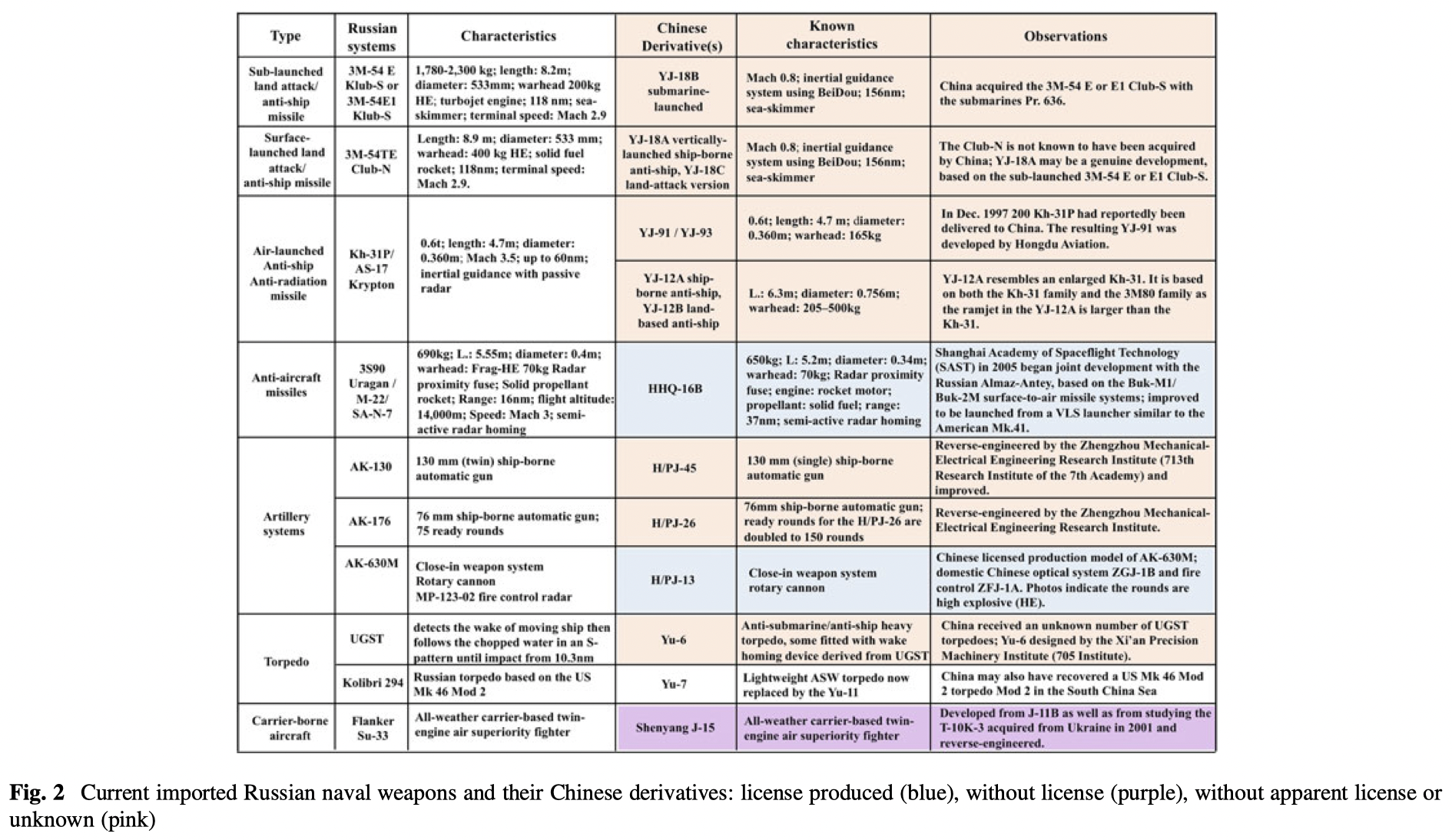

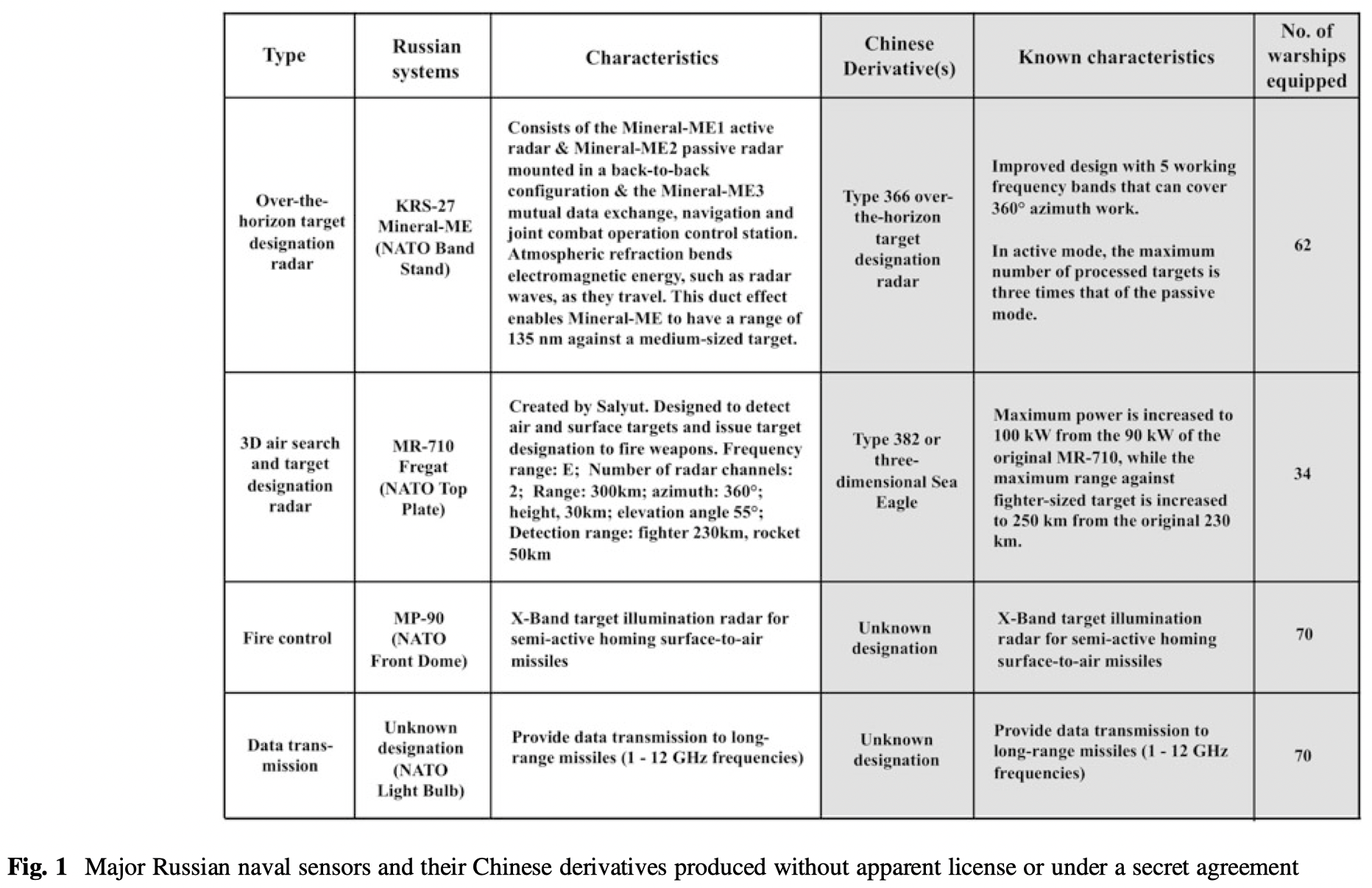

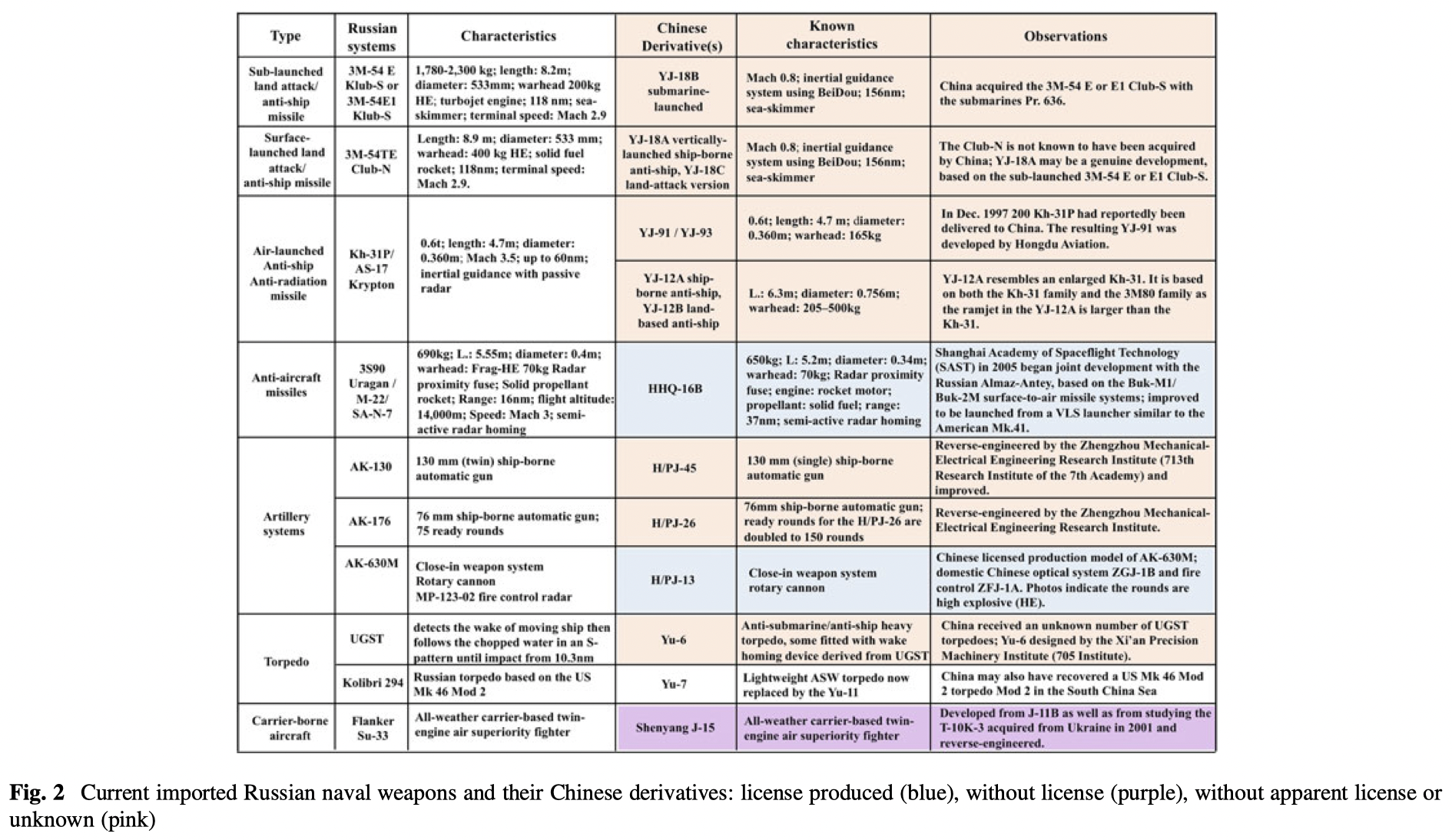

Arms transfers are an important indicator of the level of strategic trust between countries. During the past 70 years, relations between China and the Soviet Union/Russia have gone through phases that were characterized by dramatically different levels of military-industrial cooperation. This chapter explores how the fallout from the Crimea crisis of 2014 has impacted the Russian-Chinese arms trade relationship against the backdrop of a history where Russia aimed to restrict arms transfers to China. It argues that the sanctions imposed on China after the Tiananmen massacre in 1989 and on Russia since early 2014 have had the combined unintended consequence of incentivizing closer Russian-Chinese arms-industrial cooperation than had ever existed before. Western ambiguity toward Ukraine after 2014 furthermore provided China with opportunities to profit from openings in Ukraine’s arms-industrial complex. The chapter starts with a historical overview of the Russian-Chinese arms trade relationship before analyzing the impact of Russian and Ukrainian transfers on China’s military modernization before and after 2014. The final part discusses how changed incentives since 2014 have fostered unprecedented Sino-Russian arms-industrial cooperation. This could solidify the developing Chinese-Russian military relationship and eventually lead toward a more equal relationship in joint arms development.

Allies in 1950, at odds in 1960, at war in 1969, on opposite sides of the Cold War during the 1980s, the Russians and Chinese have worked out their border issues in recent years to partner against a common challenge: the United States. While it can be argued that both countries distrust one another, Moscow and Beijing share a common concern and can’t afford bad relations. Both abhor the US-Western interventions of the last two decades that in their view have destabilized the Middle East, generating terrorism and instability within or near their borders. Both resent US support for their domestic opposition or to neighboring intimate “foes,” most notably Taiwan, Ukraine, and Georgia. Both have displayed their support for Syria and Iran. Both have been engaged in a “strategic partnership” within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization since 2001. Both are now conducting joint naval exercises, sometimes in sensitive areas. But beyond those gesticulations, how far can this naval partnership go? Is it a harbinger of a future military alliance? Does it suggest an intent to deter future Western interventions from the sea? Is there evidence and are there documents that formally support this signaling of strategic and naval partnerships?

China and Russia are both keen to exploit cutting-edge technologies for military use. Most of these advanced technologies are embedded in the so-called fourth industrial revolution (4IR), such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, automation and robotics, quantum computing, big data, 5G networking, and the “Internet of Things” (IoT). At the same time, most research and development (R & D) taking place in the 4IR is occurring in the commercial realm. The usefulness of 4IR technologies to future military capabilities will depend on how well countries can leverage breakthroughs in commercial R & D, via military-civil fusion (MCF). China and Russia are pursuing concurrent and often intertwined R & D programs to develop and advance 4IR technologies in their respective countries—particularly AI—and to subsequently utilize these technologies (via MCF) in military applications. Their mutual interests in exploiting cutting-edge technologies to underwrite military modernization could motivate Beijing and Moscow to collaborate on future 4IR R & D. Nevertheless, such cooperation could be limited. In particular, Russia lacks the resources or overall technological capacities (money and manpower, plus an already low level of innovation in the national economy) to function as an equal to China, and it may not wish to play the junior partner in such a relationship.

Nuclear issues have historically played an important role in the development of relations between Moscow and Beijing, acting as a source of both potential discord and emergent cooperation. From 1964, when China conducted its first nuclear test, until Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s tenure in the 1980s, nuclear relations between the Soviet Union and China were explicitly adversarial. The normalization of Sino-Soviet relations introduced an era of implicitly adversarial relations that lasted until the Ukraine crisis. During this phase, Russia’s concerns about China’s growing military power and its resulting determination to maintain nuclear deterrence of China remained apparent. Since the onset of the Ukraine crisis, Russia and China have built an increasingly close relationship, leading to a new phase of implicitly cooperative nuclear relations featuring coordinated efforts to maintain nuclear deterrence of the United States. The two countries jointly oppose U.S. efforts to build missile defense systems and high-precision conventional weapons. They coordinate their positions on such issues as multilateral arms control and the post-INF strategic landscape. Russia is helping China to build a missile attack early warning system. Growing levels of defense cooperation raise the possibility of coordinated efforts to maintain nuclear deterrence of the United States in a crisis.

CONTENTS

I. Front Matter

Pages i–xxi

- Sarah Kirchberger, Svenja Sinjen, Nils Wörmer

Pages 1–13

II. Mutual Perceptions and Narratives

III. The Military Dimension of Sino-Russian Cooperation: Case Studies

- Alexandre Sheldon-Duplaix

Pages 101–120

- Richard A. Bitzinger, Michael Raska

Pages 121–140

IV. Spatial and Multilateral Aspects of Sino-Russian Cooperation: Case Studies

Front Matter

Pages 163–163

- Elina Sinkkonen, Jussi Lassila

Pages 165–184

V. The Way Forward: How Could the West Cope with Russia and China?

Front Matter

Pages 243–243