China’s Coast Guard: Organization, Forces, and Yellow Sea Applications

Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Coast Guard: Organization, Forces, and Yellow Sea Applications,” in Andrew S. Erickson, ed., Maritime Gray Zone Operations: Challenges and Countermeasures in the Indo-Pacific (New York, NY: Routledge Cass Series: Naval Policy & History, 2022), 54–76.

Introduction

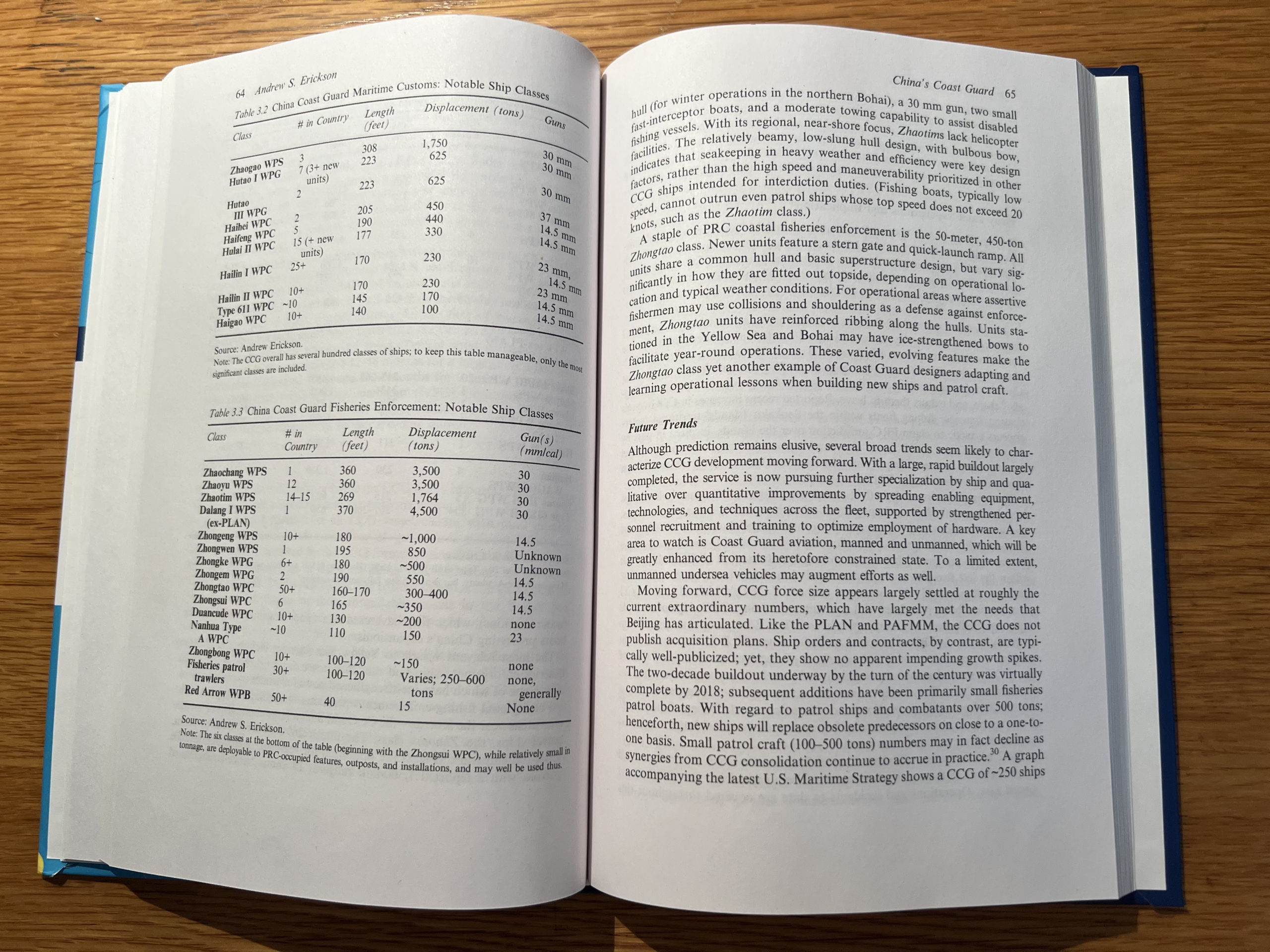

China has by far the world’s largest Coast Guard by number of ships, with the world’s largest Maritime Law Enforcement (MLE) ships by size.2 By 2017, following an historically unprecedented two-decade buildup, China’s 17,000-plus CCG personnel crewed 225 ships of over 500 tons capable of operating offshore, and at least another 1,050 vessels confined to closer waters, for a total of over 1,275—more hulls than the Coast Guards of all its regional neighbors combined.3 Five years later, fleet size has stabilized at approximately this level.

This MLE juggernaut is proportionate to China’s other superlative elements of national power. China has the world’s second largest defense budget, funded by what is at least the world’s second largest economy. Among many other defense distinctions, it also has the world’s largest Navy and Maritime Militia by number of ships. Together, China’s three sea forces “form the largest maritime force in the Indo-Pacific.”4 Still more germane to MLE issues, China has the world’s largest fishing fleet and world’s most fishers. It has the world’s largest merchant marine, largest aquaculture and pisciculture industries, and largest marine sector overall. Managing them—together with fisheries enforcement, marine traffic supervision, ensuring safety of life at sea, and customs administration more generally—constitutes a vital mission set for the CCG, inherently requiring numerous ships and personnel to execute fully and effectively.5

But here’s the rub: China also has the world’s most numerous and ex-tensive disputed maritime and island/feature claims, with the largest number of other parties. Addressing them is likewise an important mission for the CCG. The CCG and its predecessor white hull counterparts (the “Five Dragons”—State Oceanic Administration, China Marine Surveillance, Fisheries Law Enforcement, etc.) have been involved in sovereignty disputes for years. (Admiral Swift cites a case with the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1960 in his Preface; a more recent example is CCG enforcement of Beijing’s seizure of Scarborough Shoal from 2012 onward.) Beijing employs its MLE forces to advance its disputed sovereignty claims to a greater degree than most other powers, and on a greater scale than all. Moreover, the CCG’s force structure, organization, and leadership have evolved dramatically in recent years, with further developments unfolding as you read these words. An updated understanding of China’s second sea force is therefore long overdue, although it will be far from the final word.

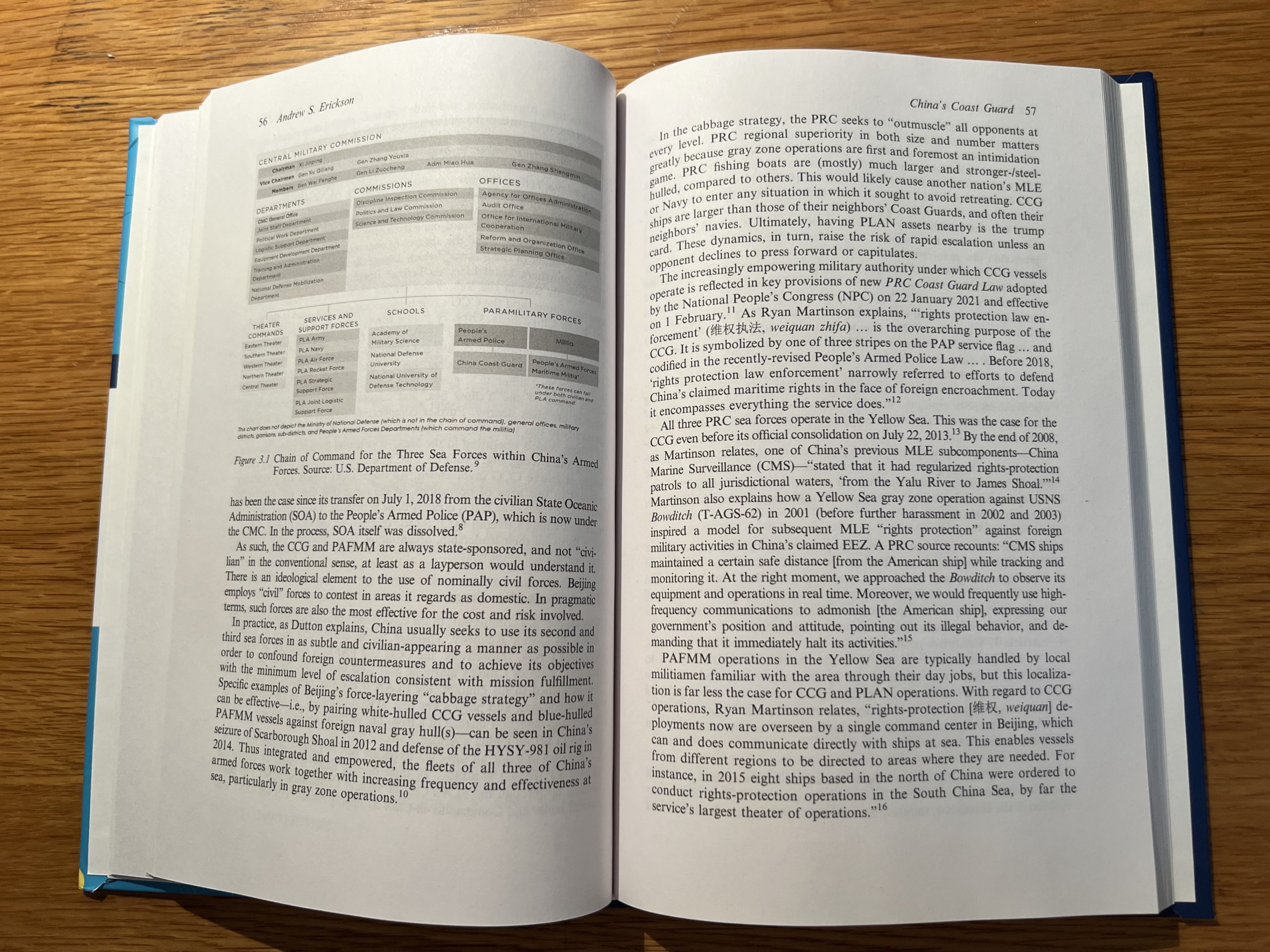

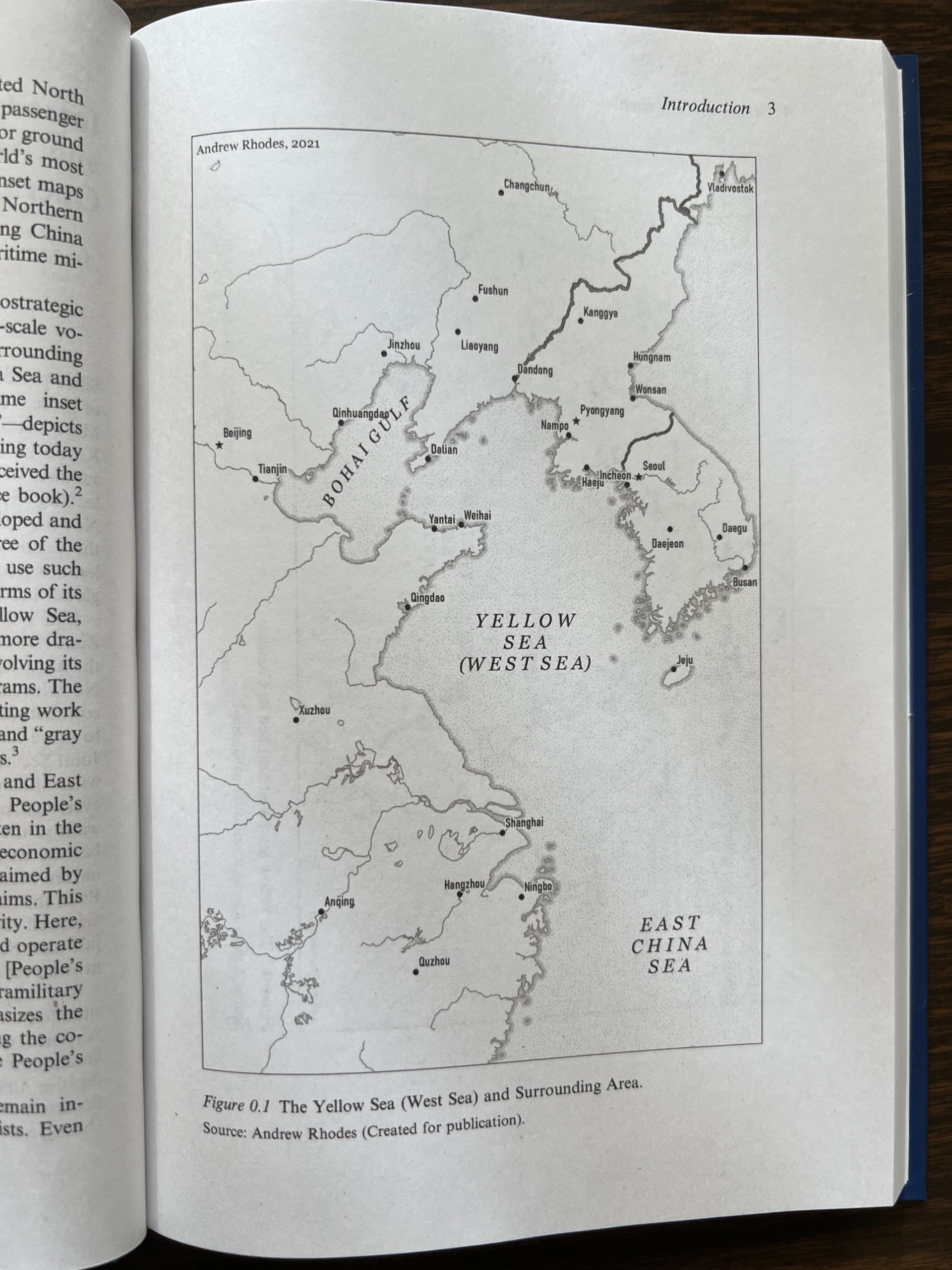

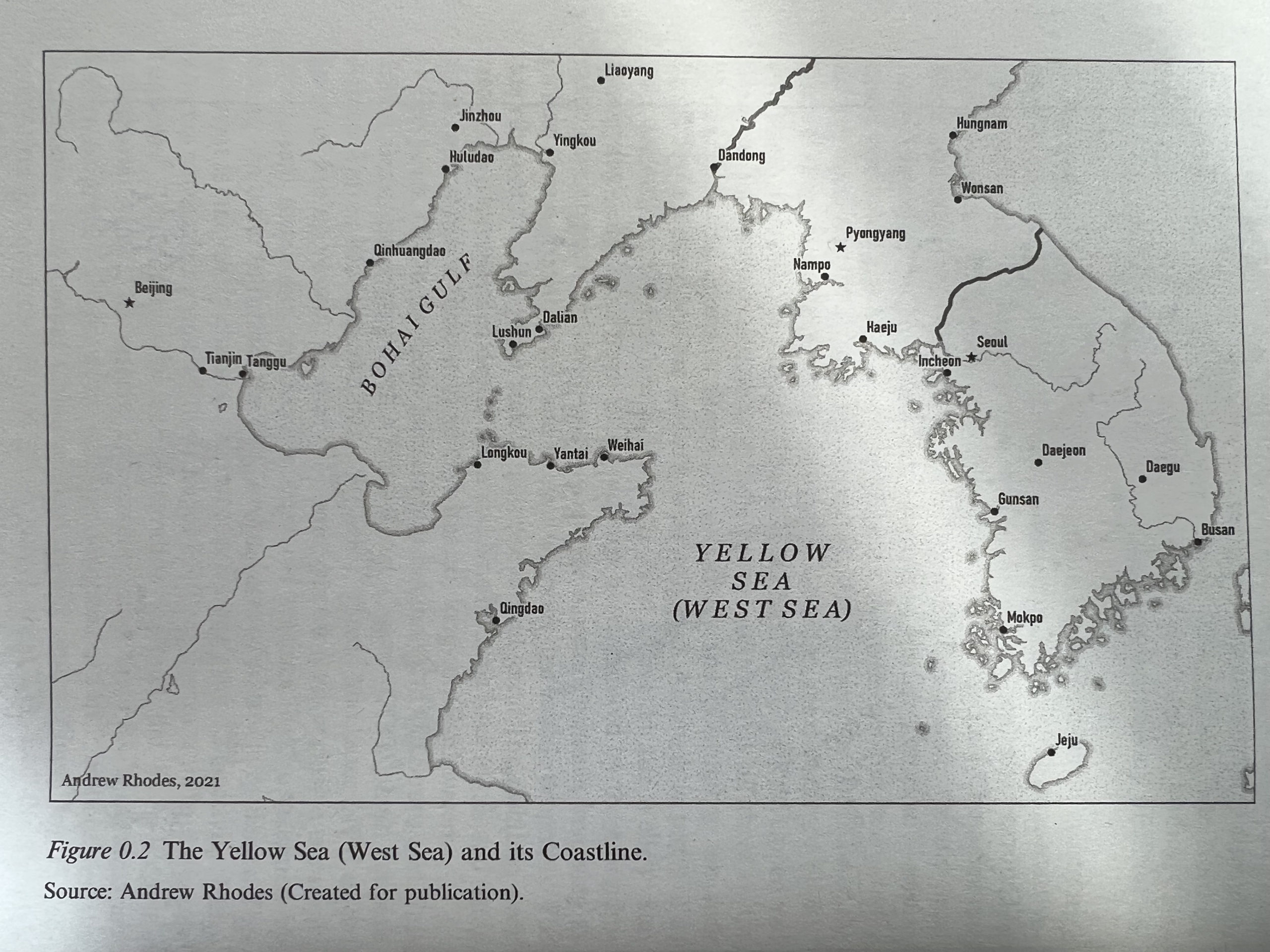

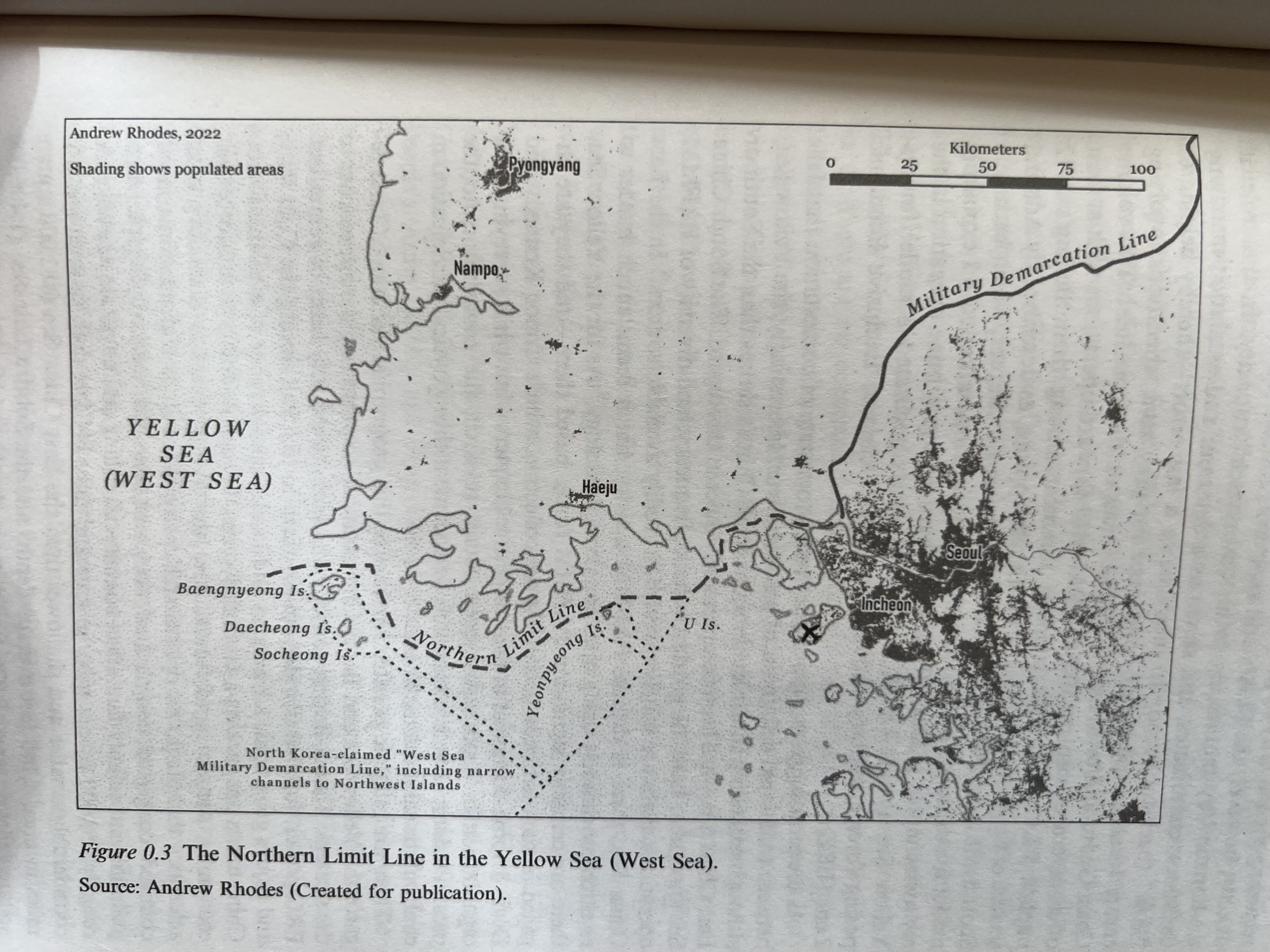

From the CCG’s perspective, the operational environment and key dynamics of the Yellow Sea may be distilled concisely. As Admiral Swift relates from operational experience in his Preface to this volume, the Yellow Sea is a confined, congested, contested zone. Characteristics specific thereto include political sensitivities stemming from proximity to Beijing—as well as Seoul and Pyongyang—and the absence of contested land features between China and either of the Koreas6 (which dispute the status of maritime zones near the Northern Limit Line,7 as Terence Roehrig details in his chapter). This suggests that in the Yellow Sea Beijing places less emphasis on gray zone operations, and the CCG’s role is somewhat different, than in the East and South China Seas. Gregory Poling surveys the key flashpoints in his chapter, the most extensive of which involve fishing rights disputes stemming from overlapping exclusive economic zone (EEZ) claims, particularly between China and South Korea. Beijing also opposes the operations of U.S. Navy and other U.S. government vessels in its claimed EEZ, which covers much of the Yellow Sea, and discourages their participation in military exercises nearby. Further complicating matters is North Korean proximity to this waterway and the fact that North Korea has its own fleet of fishing vessels operating in the area—a potential friction point between Beijing and Pyongyang. From the PRC’s perspective, fishing disputes alone justify extensive CCG involvement. All major CCG vessels are potentially relevant to this area of operations, in the sense that they are potentially deployable there even if this is rarely done in practice. This chapter therefore examines China’s overall MLE forces, centered on the CCG, with a particular focus on their leadership, organization, force structure, future trends, and operational employment. … … …

VOLUME INFORMATION

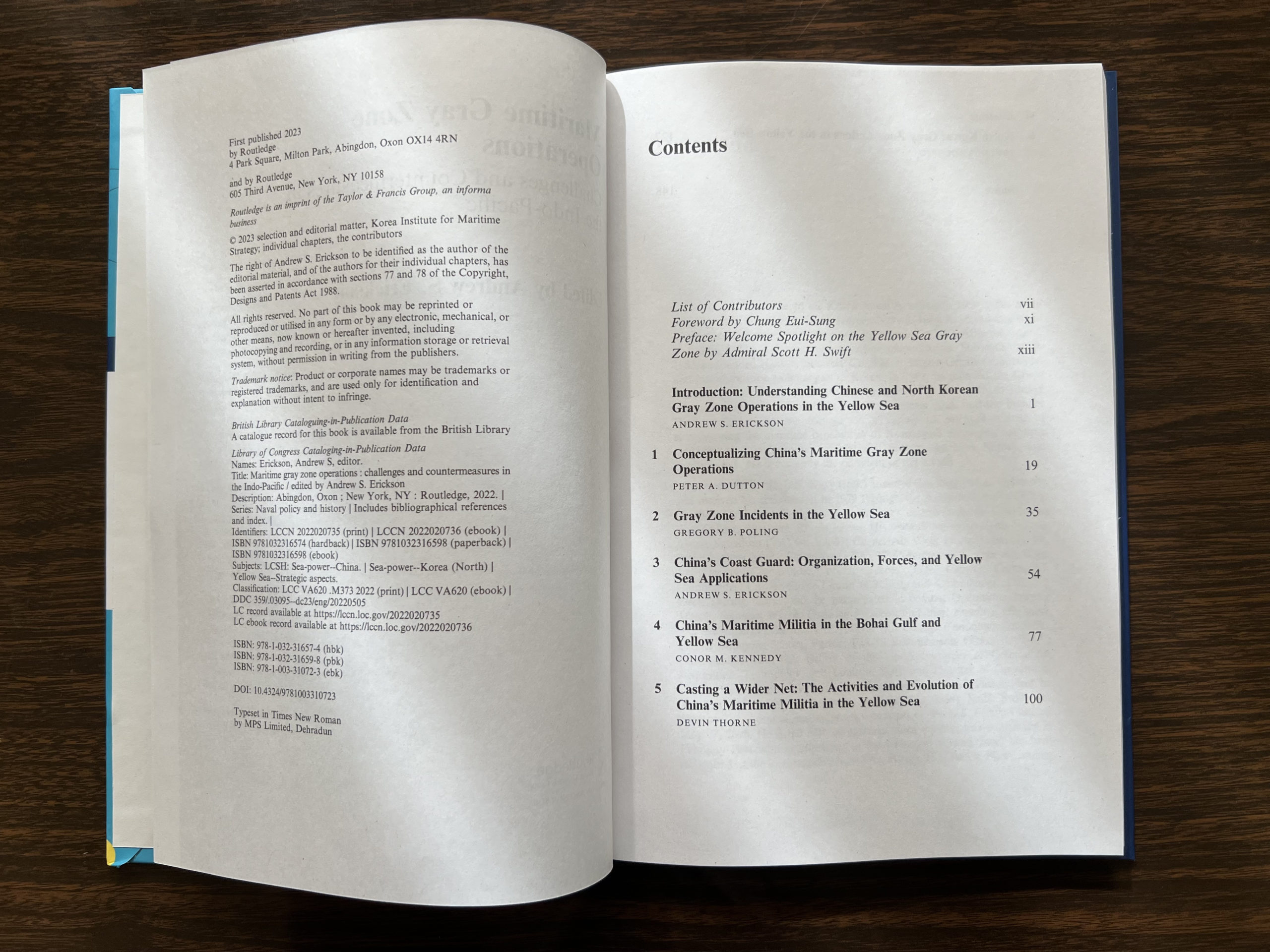

Check out our new book, published in Naval War College Professor Geoffrey Till’s Routledge Cass Series on Naval Policy & History. Sponsored by the Korea Institute for Maritime Strategy (KIMS), it offers:

1) An authoritative Preface by former Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet Admiral Scott Swift (USN, Ret.).

2) Cutting-edge chapters by Peter Dutton, Gregory Poling, Conor Kennedy, Devin Thorne, & Terence Roehrig.

3) Uniquely revealing maps by Andrew Rhodes—including of the Northern Limit Line, Pyongyang’s counterproposals thereto, the five nearby Northwest Islands under South Korean control.

Proud to work with these leading stakeholders & superstars! Peter offers the best gray zone conceptual framework I’ve yet seen. Greg offers a tour de force of comparative context vis-a-vis the South China Sea & East China Sea. Devin offers unparalleled insights on the evolution of specialized PAFMM forces & the extent of their operations in the Yellow Sea. Terry delivers a powerful history & current survey of North Korean strategy, policy, & actions in these strategically pivotal yet strangely understudied waters.

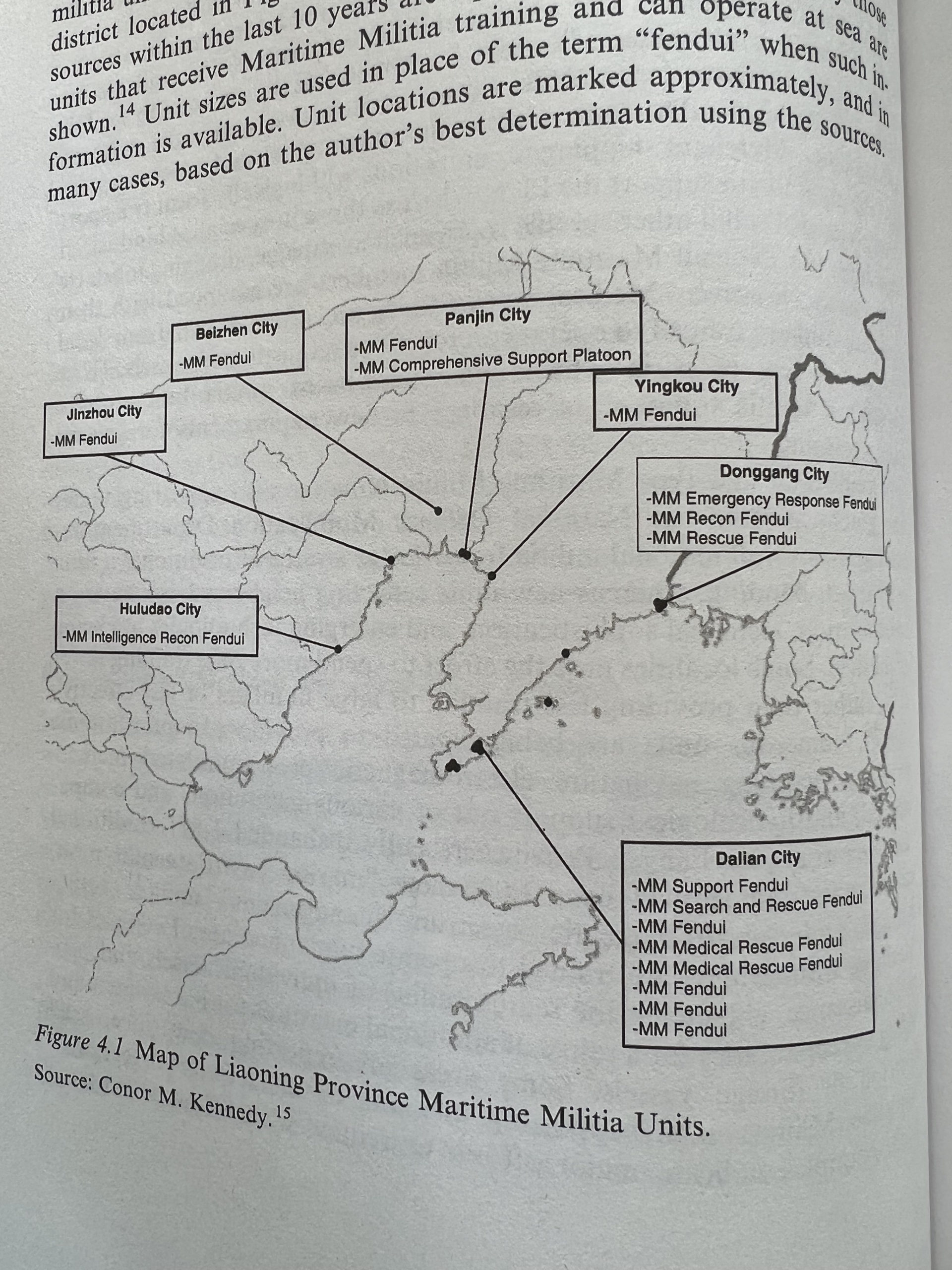

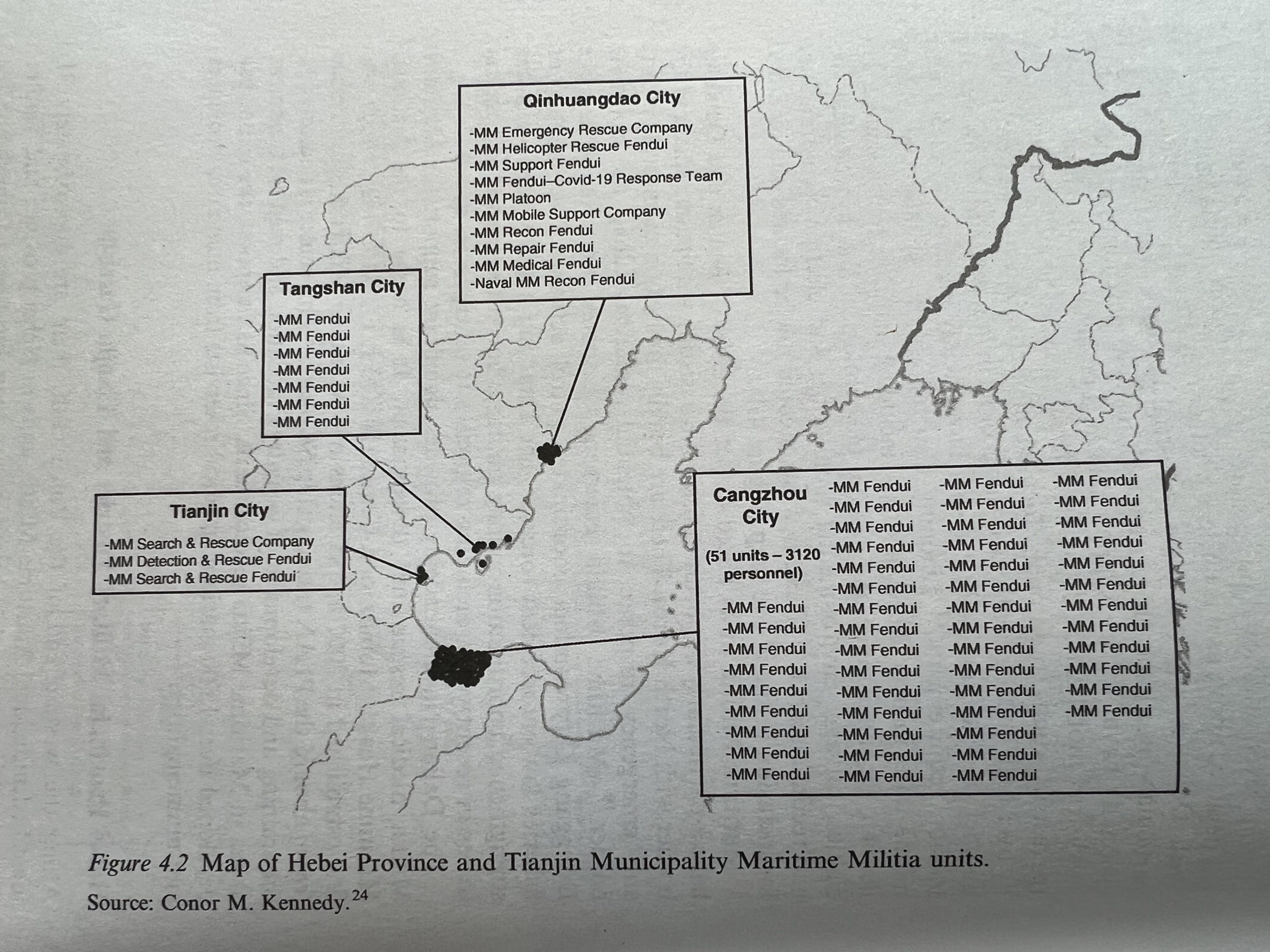

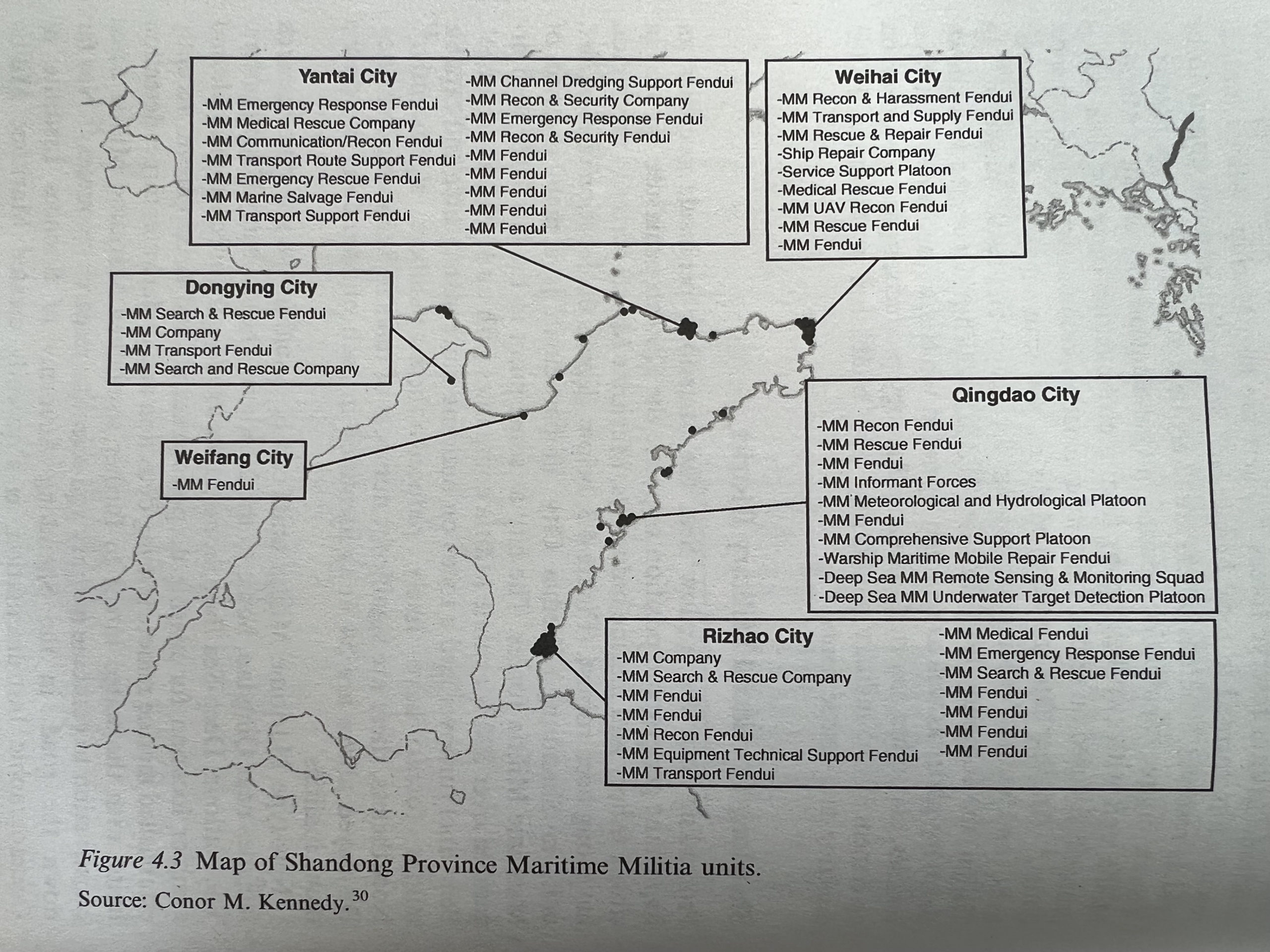

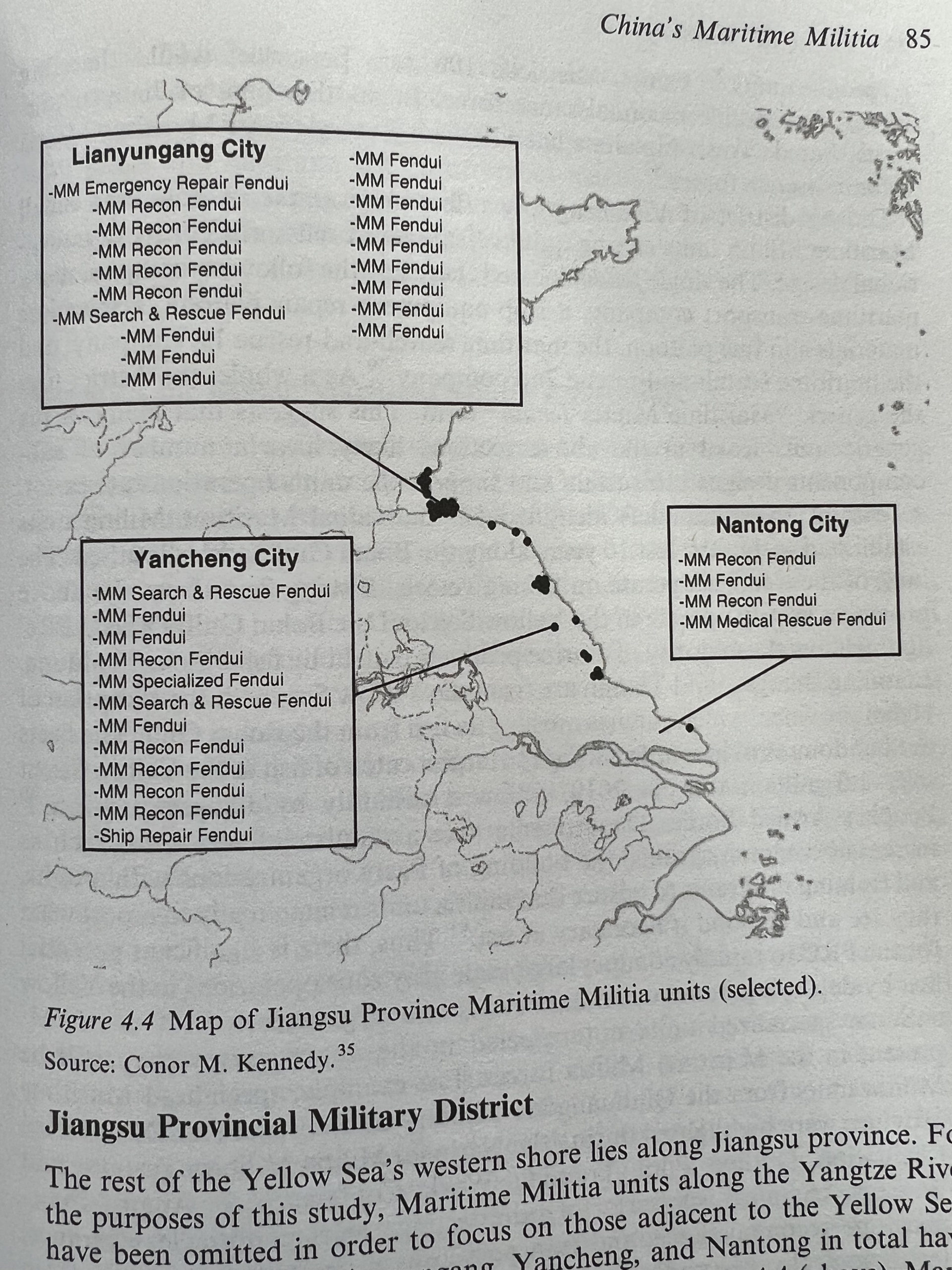

To see just how deep our new book dives in with original Chinese-language research, etc., see the graphics (& endnotes) in Conor’s chapter! He’s identified, geolocated & analyzed Yellow Sea Maritime Militia units beyond anything else Open Source to the very best of my knowledge.

I’m honored to offer an Introduction and a chapter on the China’s Coast Guard. Hope this book helps increase attention to, & understanding of, all these vital issues…

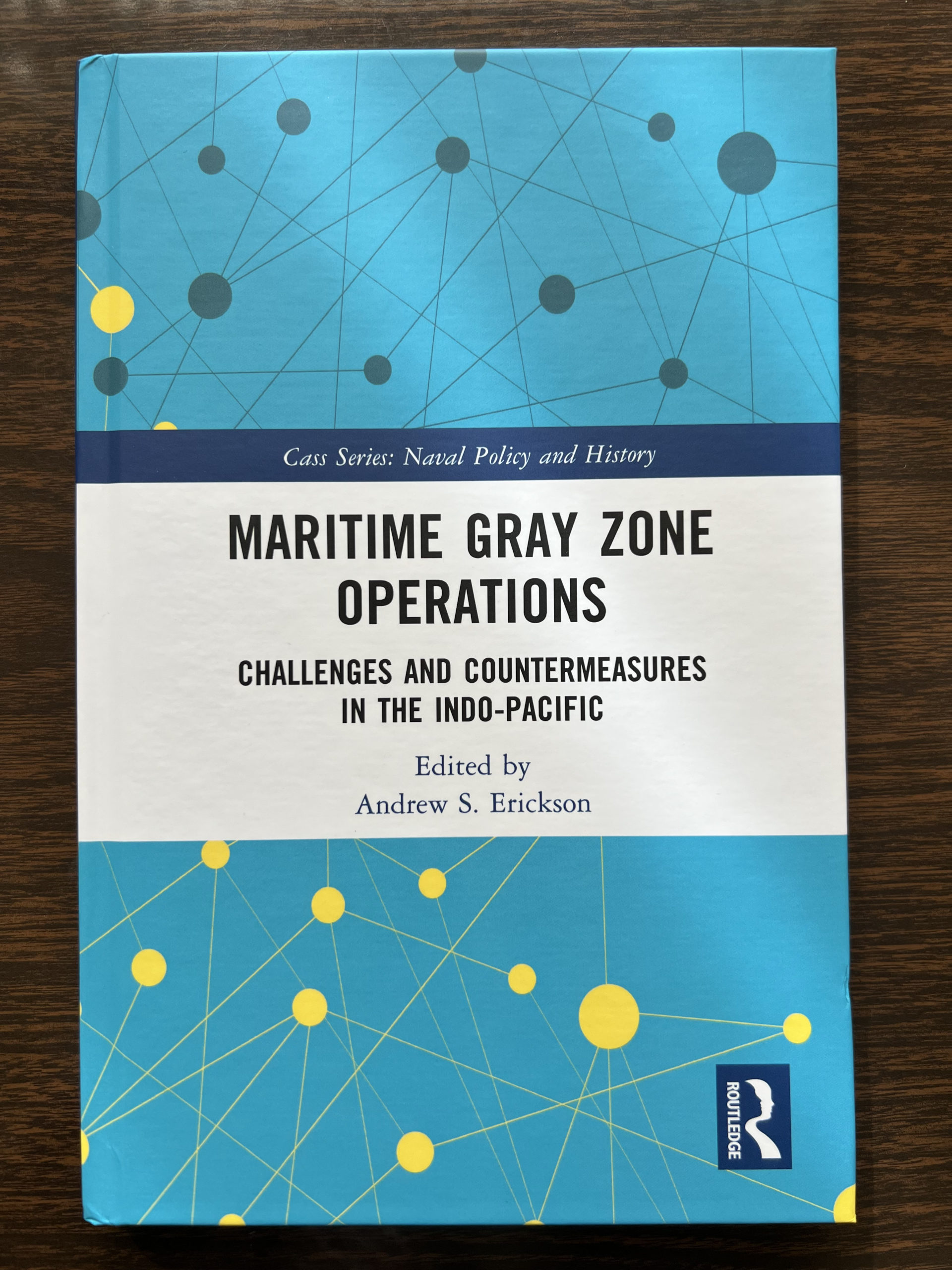

Andrew S. Erickson, ed., Maritime Gray Zone Operations: Challenges and Countermeasures in the Indo-Pacific (New York, NY: Routledge Cass Series: Naval Policy & History, 2022).

Author of:

- Andrew S. Erickson, “Introduction: Understanding Chinese and North Korean Gray Zone Operations in the Yellow Sea,” 1–18.

- Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Coast Guard: Organization, Forces, and Yellow Sea Applications,” 54–76.

Book Description

This book addresses the issues raised by Chinese and North Korean maritime ‘gray zone’ activities in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region.

For years, China has been harassing its neighbors in South China Sea and East China Sea, employing both coast guard and maritime militia forces, in the name of safeguarding Chinese sovereignty. This behavior is frequently characterized as constituting ‘gray zone’ activity. As the term suggests, this refers to a state of conflict that falls between peace and war. Interestingly, the Yellow Sea, which is geographically much closer to China than South China Sea or East China Sea, has been comparatively quiet. However, there is a danger that the PRC has the capability to replicate its gray zone activities in this area. Worse, North Korea has also been engaging in carefully-calibrated provocations there. This book addresses pressing questions about these activities and offers: (1) a conceptual framework to understand maritime gray zone operations and Beijing and Pyongyang’s approach, with an unprecedented focus on the Yellow Sea; (2) a comprehensive, fully updated fleet force structure for the PRC’s Coast Guard, together with projections regarding how the Coast Guard is likely to develop in the future; (3) an extensive organizational analysis of the PRC’s Maritime Militia that surveys the many units relevant to Yellow Sea operations, some revealed publicly for the first time; and (4) a detailed assessment of North Korean maritime ‘gray zone’ activities.

This book will be of great interest to students of naval strategy, maritime security, Asian politics, and international security.

Table of Contents

Introduction: Understanding Chinese and North Korean Gray Zone Operations in the Yellow Sea

Andrew S. Erickson, U.S. Naval War College and Harvard University

1. Conceptualizing China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations

Peter A. Dutton, U.S. Naval War College and MIT

2. Gray Zone Incidents in the Yellow Sea

Gregory B. Poling, Center for Strategic and International Studies

3. China’s Coast Guard: Organization, Forces, and Yellow Sea Applications

Andrew S. Erickson, U.S. Naval War College and Harvard University

4. China’s Maritime Militia in the Bohai Gulf and Yellow Sea

Conor M. Kennedy, U.S. Naval War College

5. Casting a Wider Net: The Activities and Evolution of China’s Maritime Militia in the Yellow Sea

Devin Thorne, Threat Intelligence Analyst, Recorded Future

6. North Korea: Gray Zone Actions in the Yellow Sea

Terence Roehrig, U.S. Naval War College and Columbia University

Editor

Biography

Andrew S. Erickson is Professor of Strategy at the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute, RI, USA and a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Government at Harvard University.

Since presenting at the 22nd Annual Conference of the Council on Republic of Korea (ROK)-U.S. Security Studies, convened by the Korea Institute for Maritime Strategy in 2007, it has been my honor and pleasure to visit South Korea at every opportunity. My experience deepened when I spent the summer of 2010 teaching a course at Yonsei University and meeting with leading experts from Korean academic, military, and government circles. Now, in editing this volume, I hope to help draw long-overdue attention to the Yellow Sea and Korean maritime security issues, which have received far less coverage than the Korean land-based security issues that regularly make global headlines.

Like many foreigners, I have repeatedly visited the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). (For security reasons, South Korean civilians are barred from the boundary area itself, even as servicemembers guard the front lines there.) No witness to this unique location could fail to be moved by its stark contrasts and historical, political, and geostrategic significance. It is striking to drive through the carefully protected village of Daeseong-dong into the Joint Security Area and to enter the border-straddling Conference Building, where bilateral negotiations and meetings are occasionally held. Once the ever-vigilant ROK sentries have secured the door at the far end, one may walk to the side of the table that technically lies in North Korea. Amid the barbed wire and land mines separating the Koreas since 1953, a vibrant nature reserve resounds with birdsongs—offering hope of a better future. Even the drive back to Seoul is stirring. Sometimes I witness South Korean armored vehicles lumbering along the highway. Always I am most struck by just how close this dangerous division is to a leading global megacity, which grows ever closer to it.

Yet, airplane flights in and out of Seoul present a similarly striking situation—a window into the subject of this book. Incheon International Airport is one of world’s largest, busiest, most highly rated airports. Built on a landfill between two small islands in the Yellow Sea, it lies near the historically decisive Allied landing of September 10–19, 1950. As an aircraft approaches or departs from Incheon, it typically passes close to the Northern Limit Line (NLL), a seaward extension of the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) dividing the Koreas on land, but highly contested in practice. And undisputed North Korean territorial waters, airspace, and territory are not far away. A passenger viewing waters, islets, and mudflats from the window of their aircraft or ground transportation over Yeongjong Bridge is witnessing one of the world’s most cramped, contested maritime spaces. The third of the three volume inset maps that follow below in this Introduction, Fig 0:3 Figure 0.3—entitled “The Northern Limit Line in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)” and produced by leading China analyst and cartographer Andrew Rhodes,1 depicts this military maritime microcosm. … … …