CMSI China Maritime Study/‘Red Book’ 17—“The Maritime Fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific: Indonesia & Malaysia Respond to China’s Creeping Expansion in the South China Sea”

Scott Bentley, The Maritime Fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific: Indonesia and Malaysia Respond to China’s Creeping Expansion in the South China Sea, Naval War College China Maritime Study 17 (January 2023).

Dr. Bentley is a civilian analyst for the U.S. Department of the Navy, but the views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or U.S. government. This monograph draws extensively from research undertaken for the author’s PhD dissertation while resident in Canberra at the Australian Defence Force Academy, University of New South Wales.

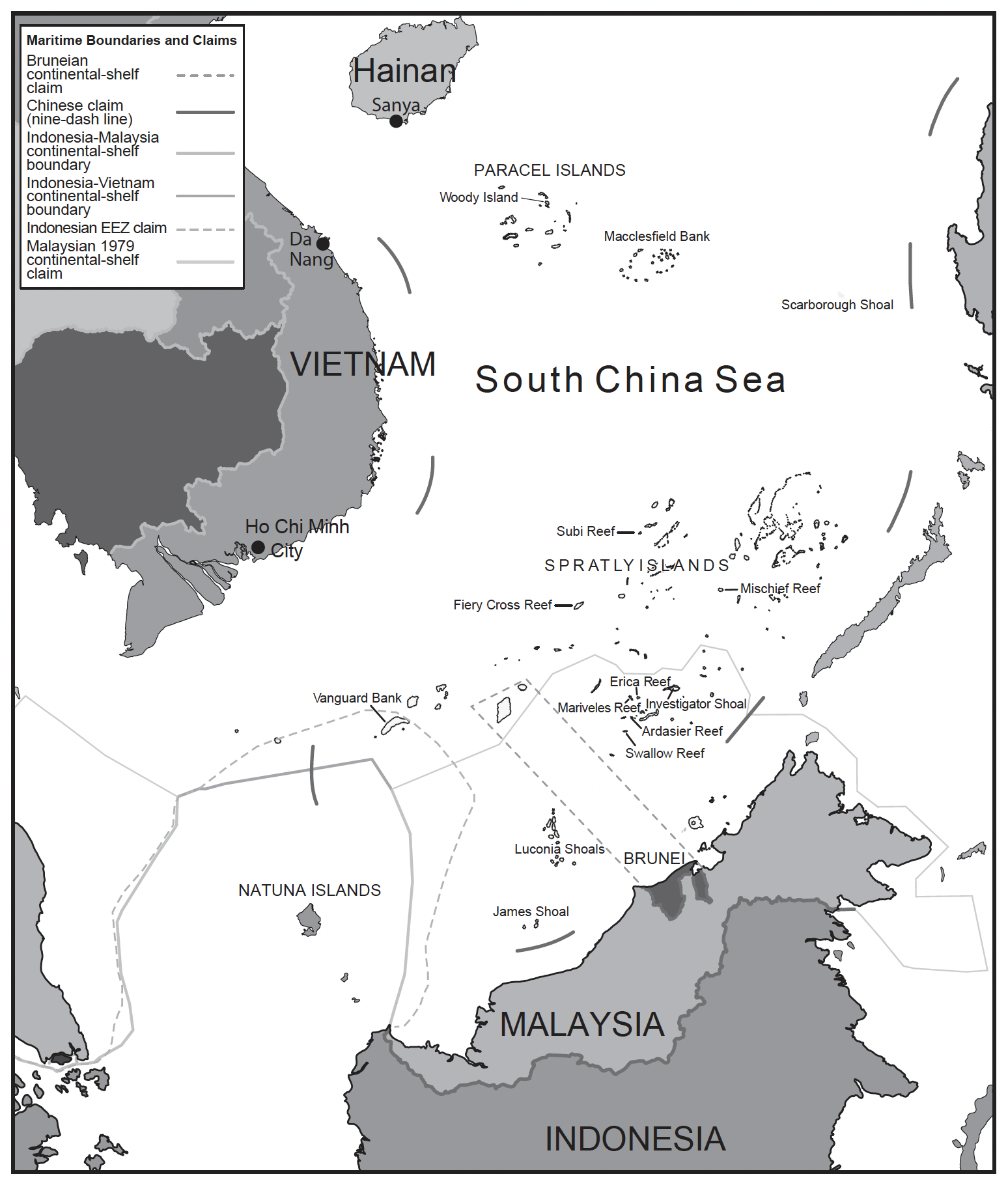

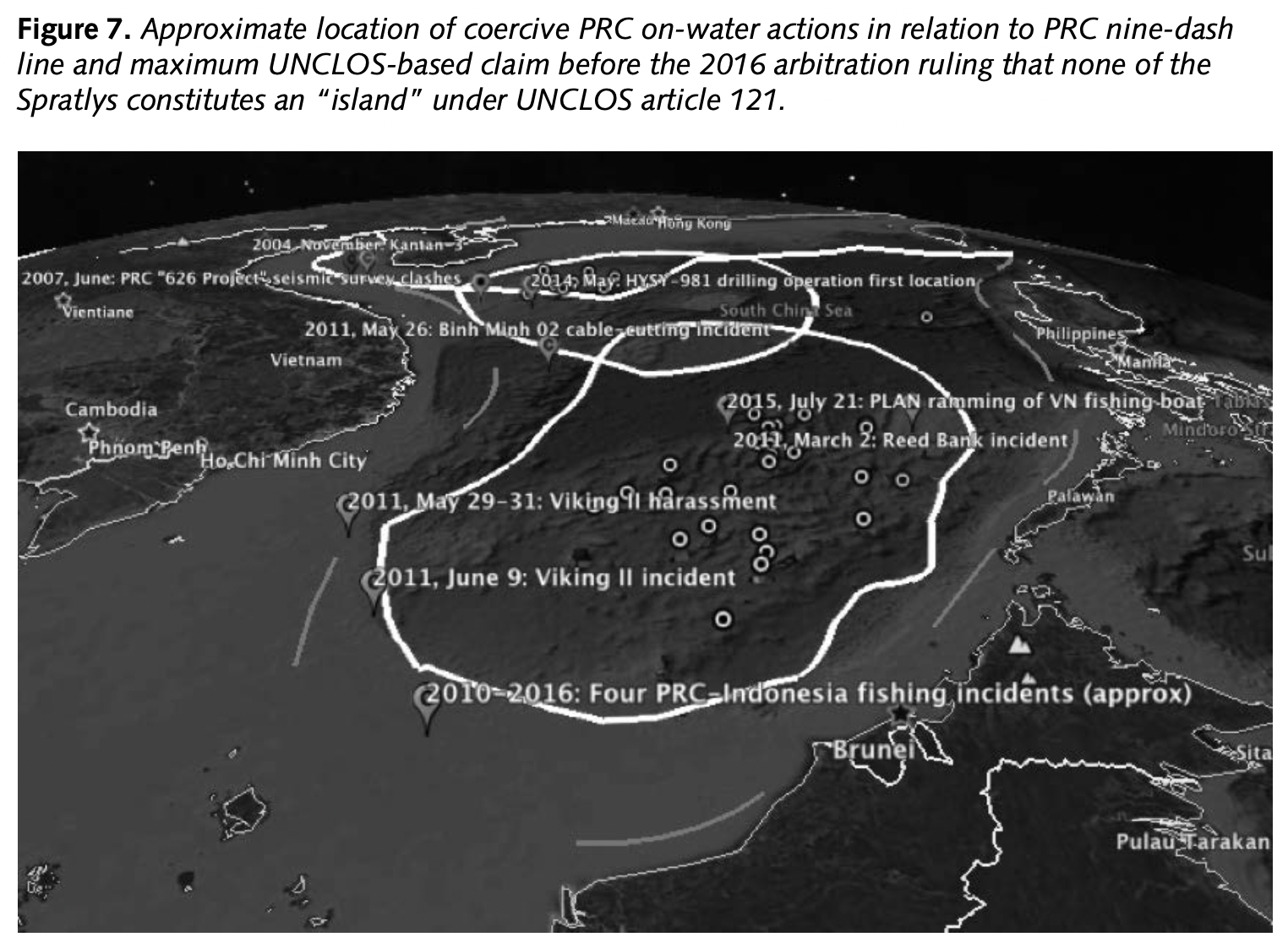

China now is attempting to expand its control to the southernmost extent of its nine-dash-line claim in the South China Sea, in waters ever closer to Indonesian and Malaysian shores. This area of the South China Sea, spanning from Indonesia’s Natuna Islands to the South Luconia Shoals, has greater strategic importance than the Spratly or Paracel Island chains farther to the north. Whereas the Spratlys have for centuries been regarded as “dangerous ground” and commercial mariners have avoided them, the vital sea lines of communication (SLOCs) connecting the Pacific and Indian Oceans flow through this part of the southern South China Sea. Therefore, these areas are far more vital to international commerce and navigation than the dangerous grounds closer to China’s Spratly Islands outposts.

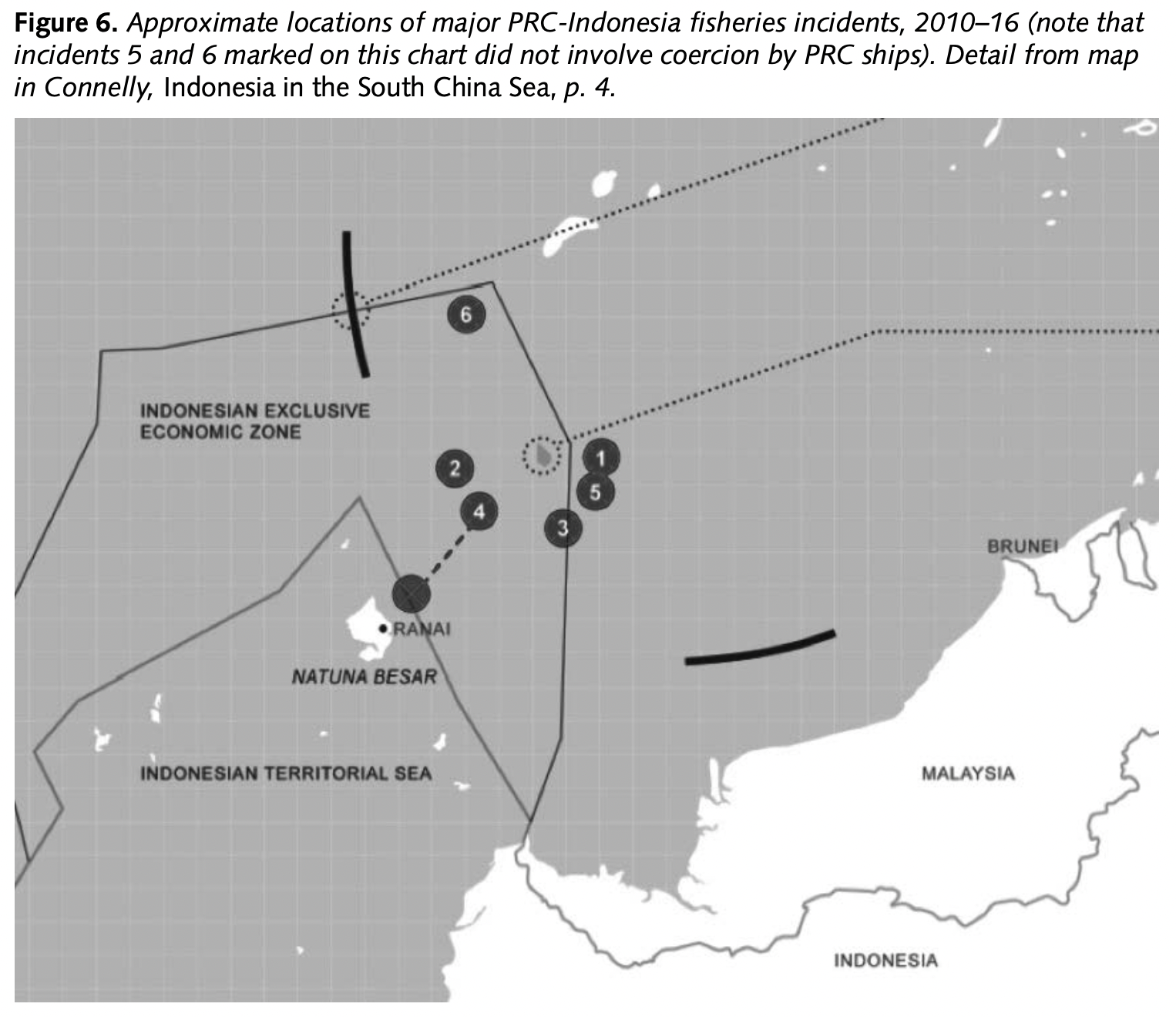

In June 2016, Indonesian president Joko Widodo held a cabinet meeting on the deck of the Indonesian Navy Parchim-class patrol craft Imam Bonjol while it operated in the South China Sea (SCS) near the Natuna Islands.1 Only several days prior, that same ship had detained a Chinese fishing vessel and arrested its crew, despite attempts by the China Coast Guard (CCG) to intervene.2 On the deck of the warship with the president were members of his cabinet including the commander of the Indonesian Armed Forces (Tentara Nasional Indonesia, or TNI), the chief of the Indonesian Navy (Tentara Nasional Indonesia–Angkatan Laut, or TNI-AL), the foreign minister, the coordinating minister for political and security affairs, and the minister for maritime affairs and fisheries, among others. Noting the economic and strategic importance of the Natuna Islands, the president announced an upgrade in maritime-defense capability for Indonesia’s naval and maritime law-enforcement (MLE) agencies, as well as an increase in patrols in the area.3 China never was mentioned by name, but the Indonesian president clearly was directing his message toward Beijing.

President Widodo, to whom Indonesians affectionately refer as “Jokowi,” stood on the deck of Imam Bonjol as a tangible symbol of Indonesian resolve in the South China Sea, following the third maritime incident with China in three months. All these incidents had involved Indonesian attempts to arrest Chinese fishing vessels operating in areas where Indonesia’s claimed exclusive economic zone (EEZ) overlaps with China’s “nine-dash line,” although not all incidents resulted in the detention of Chinese fishing vessels.

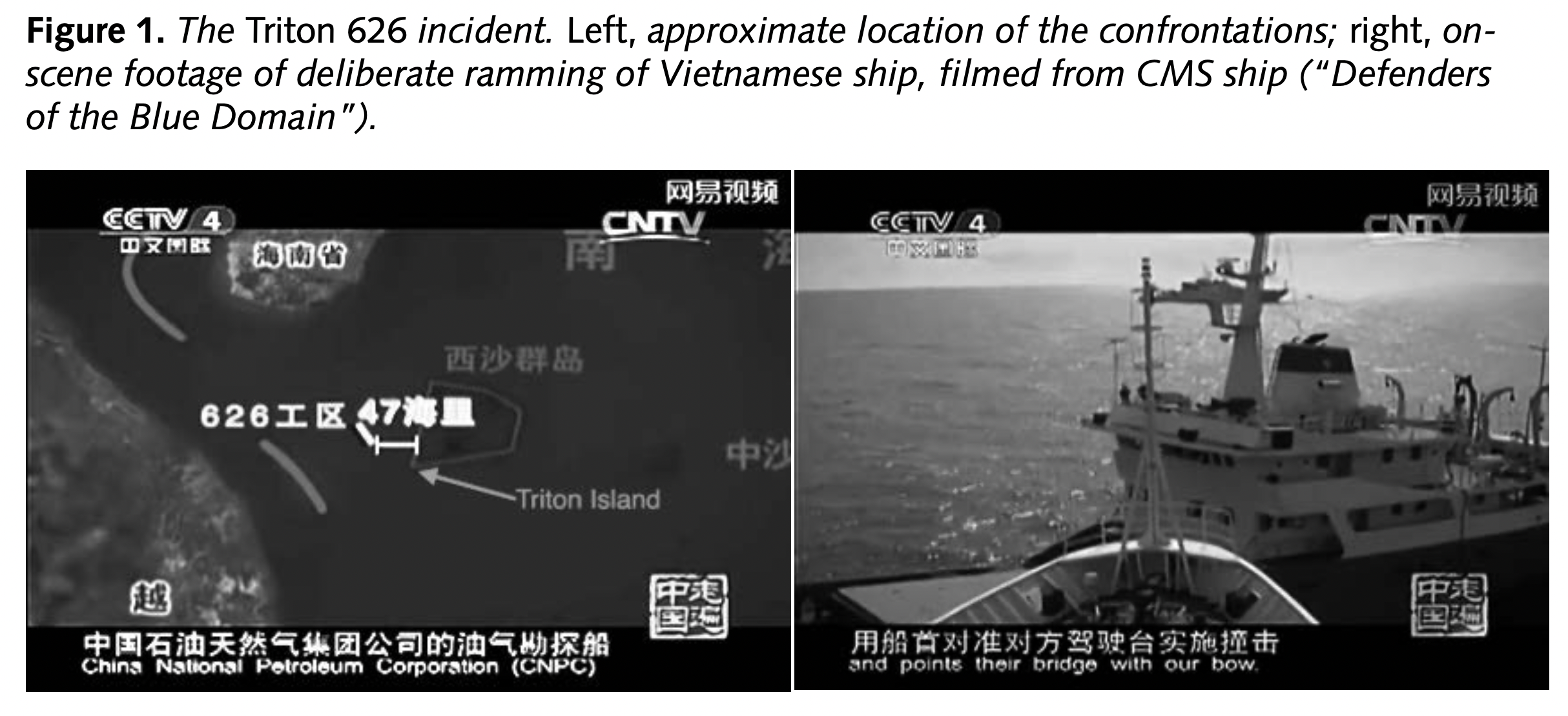

The first incident in 2016 occurred on 20 March, when the CCG Zhaoyu-class large patrol ship (WPS) 3304 rammed a Chinese fishing vessel that had been arrested and was at the time under the operational control of Indonesian MLE personnel. China’s escalatory tactics, employed almost inside the Indonesian territorial sea extending from Natuna Besar Island, effectively compelled the Indonesian personnel to abandon the Chinese fishing vessel in fear for their safety. After a second CCG patrol ship arrived on scene, CCG personnel boarded and took command of the Chinese fishing vessel, preventing Indonesian authorities from detaining it.4

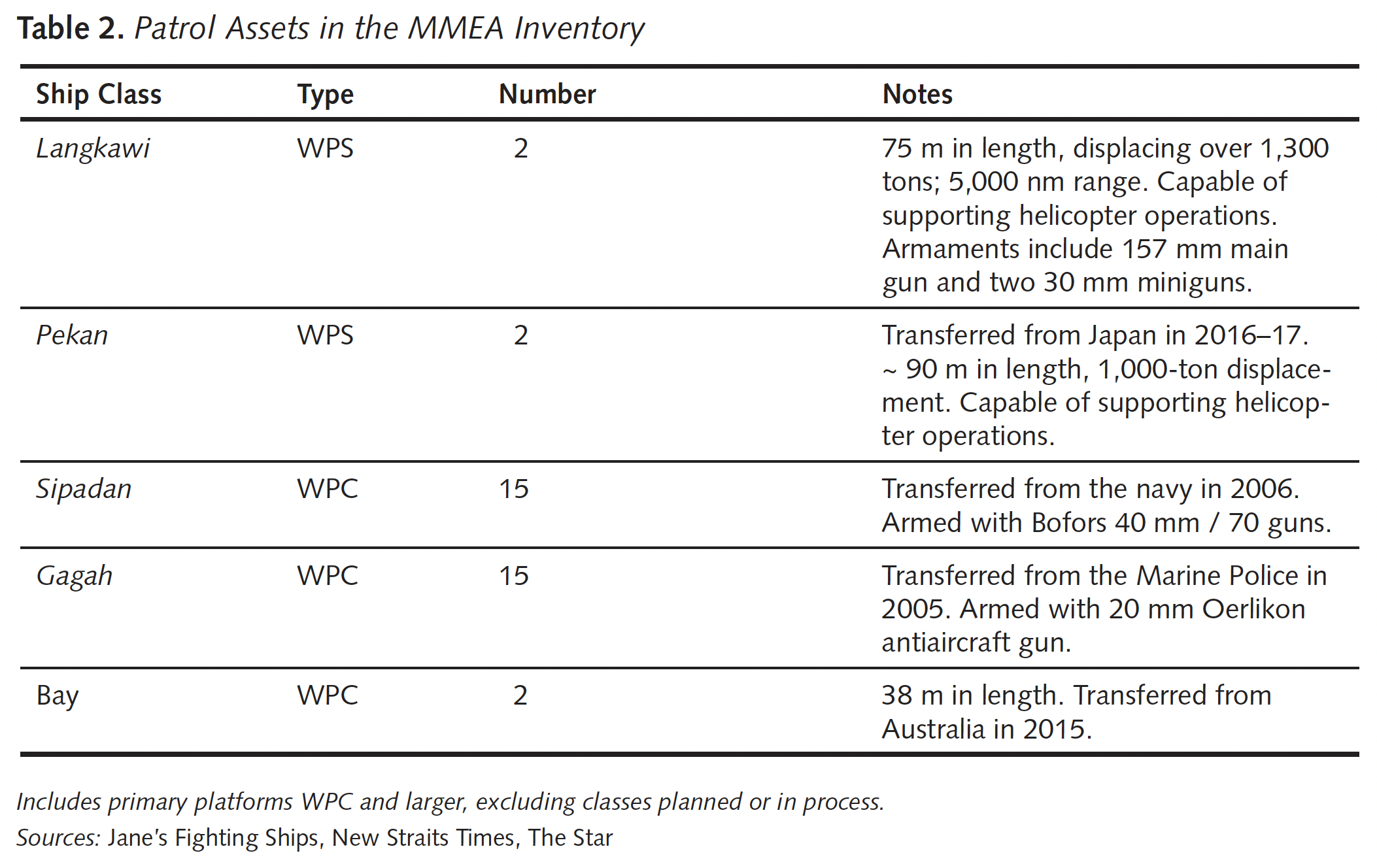

Only days after the incident with Indonesia, on 24 March 2016, officials of Malaysia’s coast guard agency, the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA), announced that they had expelled a large fleet of more than a hundred Chinese fishing vessels operating fifteen nautical miles from Malaysia’s maritime boundary with Indonesia. Given that these events occurred in a similar geographic area around the same time, it is likely that the Chinese fishing vessel the CCG freed from Indonesian authorities on 20 March was part of a much larger Chinese fishing fleet operating in the area at the time, under apparent CCG escort. The MMEA deployed five patrol ships to interdict the fleet, and later provided photographic evidence to the Malaysian foreign ministry to present to Beijing as part of a diplomatic protest over the activity.5 According to Shahidan Kassim, the minister on the Malaysian National Security Council (NSC) responsible for the MMEA at the time, the Chinese fishing fleet had been operating in the area for at least a week, and one of the Chinese fishing vessels from the fleet rammed an MMEA patrol ship, forcing the latter to return to port in Sarawak for repairs.6

These are not merely historical anecdotes. Similar Chinese activity continues to occur in the same areas, with similar responses from Indonesia and Malaysia. Most recently, from December 2019 to January 2020, a large Chinese fishing fleet—over fifty ships—operated in the southern South China Sea, escorted by multiple CCG patrol ships.7 Prior to 2010, China had no official maritime presence in these areas. When the Indonesians arrested some Chinese fishermen in 2009, China issued diplomatic protests.8 Today, China’s diplomatic and strategic goals are directly supported by a massively expanded fleet of People’s Republic of China (PRC) government ships that operate in these areas regularly.

China now is attempting to expand its control to the southernmost extent of its nine-dash-line claim in the South China Sea, in waters ever closer to Indonesian and Malaysian shores. This area of the South China Sea, spanning from Indonesia’s Natuna Islands to the South Luconia Shoals, has greater strategic importance than the Spratly or Paracel Island chains farther to the north. Whereas the Spratlys have for centuries been regarded as “dangerous ground” and commercial mariners have avoided them, the vital sea lines of communication (SLOCs) connecting the Pacific and Indian Oceans flow through this part of the southern South China Sea.9 Therefore, these areas are far more vital to international commerce and navigation than the dangerous grounds closer to China’s Spratly Islands outposts.

China does not yet control the South China Sea. Both Indonesia and Malaysia have continued to operate normally despite growing pressure from China. Although relatively less well known and little studied in the United States, Indonesia and Malaysia in fact have been the most consistently assertive among Southeast Asian claimants in the South China Sea since 2016, and both countries are responding with some success to China’s efforts to expand its control farther south, closer to their shores. Despite China’s attempts to enforce its claims in these areas, Chinese control is weakest and most vulnerable in the southern South China Sea. As long as Indonesia and Malaysia continue actively to resist China’s efforts and challenge its excessive claims in these areas, China will struggle to achieve its strategic goals.

This monograph approaches the debate on Chinese control in the South China Sea by examining the perspectives, policies, and actions of two key Southeast Asian claimants in the South China Sea, Indonesia and Malaysia. The political will of the Southeast Asian claimants is key to the broader question of Chinese control, since China must break their political will to assert their claims if it is to exercise any degree of real control. If rival claimants continue to operate in the South China Sea despite Chinese attempts to coerce them into submission, China is not in any meaningful sense of the word exerting “control” over the South China Sea. Chinese control requires rival claimants to acquiesce to China’s claims, ceasing their own operations in contested areas.

Long wary of China’s strategic intent in the South China Sea, Indonesia has continued aggressively to interdict Chinese fishing vessels operating in the overlap between Indonesia’s claimed EEZ and China’s nine-dash line, even after being confronted by CCG escorts attempting to protect them. Indonesia is the only Southeast Asian claimant successfully to have arrested Chinese fishermen and detained their vessels for operating in disputed areas of the South China Sea since 2015. Even when China has achieved operational successes, as it did in March 2016 by ramming one of its own fishing vessels, Indonesia has responded assertively, successfully detaining Chinese fishing vessels and their crews in May and June of that year. The Indonesian Navy, in particular, has shown that it is willing to escalate to low levels of military force to assert its claims, opening fire on Chinese fishing vessels on more than one occasion in 2016.10 In January 2020, Indonesia conducted the largest-ever operational deployment of navy and coast guard ships to the South China Sea, sending over a dozen surface combatants and patrol ships to challenge China’s presence in the same area.11

Despite ongoing Chinese pressure, Malaysia also has responded to Chinese activity and has continued robust hydrocarbon operations in disputed areas, including near the South Luconia Shoals and Malaysian outposts in the Spratly Islands. Over the last several decades, Malaysia steadily has developed significant oil and gas reserves in disputed areas within the nine-dash line. Malaysia is the only claimant in the South China Sea actively to have developed hydrocarbon resources near its major Spratly Islands outposts. These hydrocarbon operations also extend to the South Luconia Shoals, where the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) has maintained a countervailing presence since China established a persistent coast guard patrol there in 2013.

Thus, not only do leaders in Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur continue to display the political will to oppose Chinese control of the South China Sea, but they are acting on it. As China pushes farther south into the South China Sea, it is running directly into two of Southeast Asia’s most important strategic players. What might at first seem to be among China’s greatest strengths—its employment of an immense, integrated maritime capability to coerce Southeast Asian claimants into acquiescing to its expansive claims—rapidly is becoming its greatest weakness. China’s efforts to expand its control into the southern South China Sea has become a significant strategic vulnerability in terms of its relations with Indonesia and Malaysia. Beijing’s efforts to push south, ever closer to their shores, already has begun to amplify previously existing concerns in Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur about China’s long-term strategic intent in the region, resulting in overlapping efforts to improve their own maritime capabilities and increase security cooperation with the United States and its allies.

The United States enjoys strong and enduring relationships with both Indonesia and Malaysia, providing a competitive advantage over China, with its expansionist agenda in the region. Despite publicly espousing policies of professed neutrality since the days of the Cold War, both Indonesia and Malaysia have continued to tilt strategically toward the United States and its allies.12 Indonesia and Malaysia are natural geopolitical partners for the United States, and their growing importance has been recognized in U.S. national strategy.13 Both are legitimate and vibrant democracies, in a region trending overall in the other direction.14 Strategically positioned astride vital SLOCs in and out of the South China Sea, these two countries comprise the connective tissue between the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Together, Indonesia and Malaysia form the maritime fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific. The success or failure of China’s creeping expansion ultimately will hinge on the political responses from leaders ashore in Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur. New opportunities are emerging to enhance U.S. engagement and reinforce the capability of these partners to resist Chinese coercion. The future of the Indo-Pacific hangs in the balance.

This study proceeds by first briefly outlining China’s push south and its efforts to expand its control in the South China Sea. Next, the bulk of the monograph is devoted to analyzing Indonesian and Malaysian perceptions of China, and examining those countries’ responses to China’s creeping expansion in the South China Sea. These responses have included efforts to increase their own naval and coast guard presence in disputed areas, efforts enabled by growing maritime capabilities, as well as increased security cooperation with the United States and its allies. The study details these responses through March 2020, but does not address subsequent developments, including the global COVID-19 pandemic. Despite recent developments prior to publication, the strategic trends outlined in the monograph are deep rooted and likely will persist. A conclusion summarizes these trends and highlights opportunities for U.S. policy makers to enhance long-standing security and defense cooperation with these two crucial geostrategic partners located at the maritime fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific. … … …

PREVIOUS PUBLICATIONS IN THE SERIES:

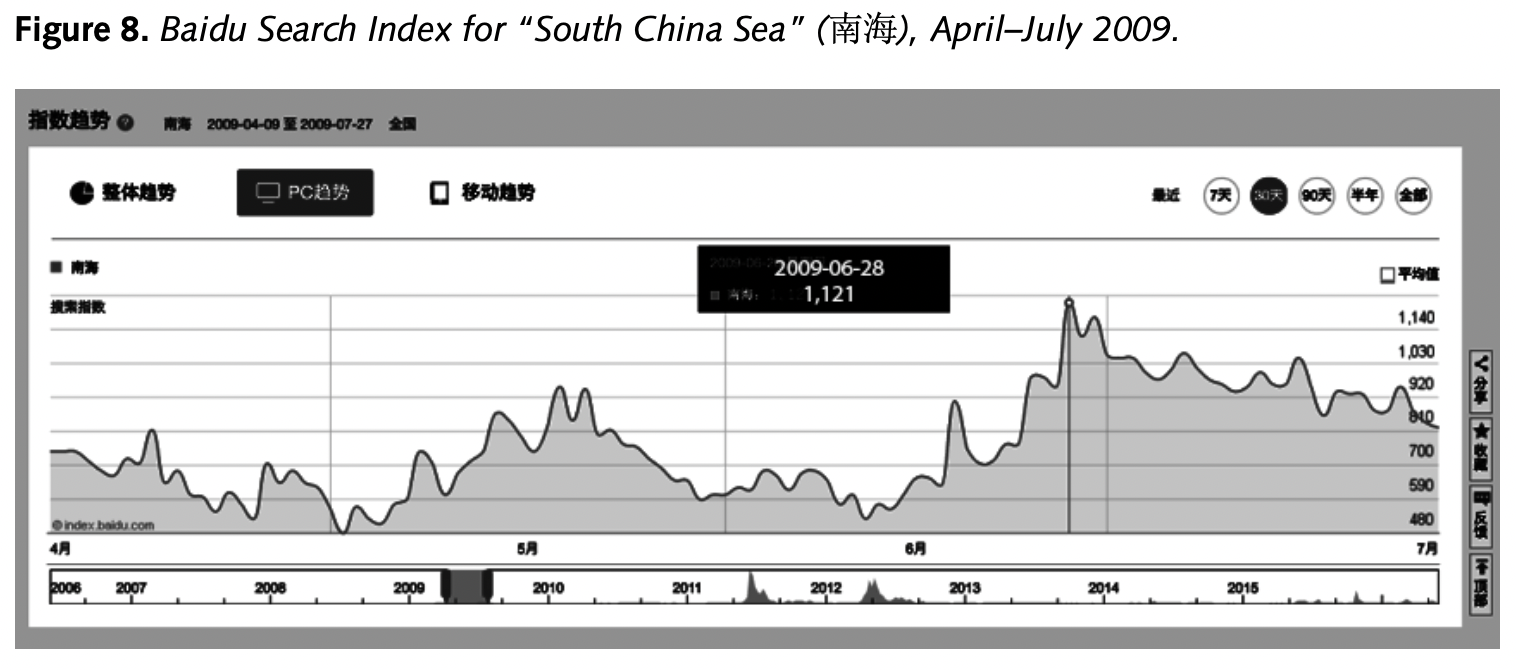

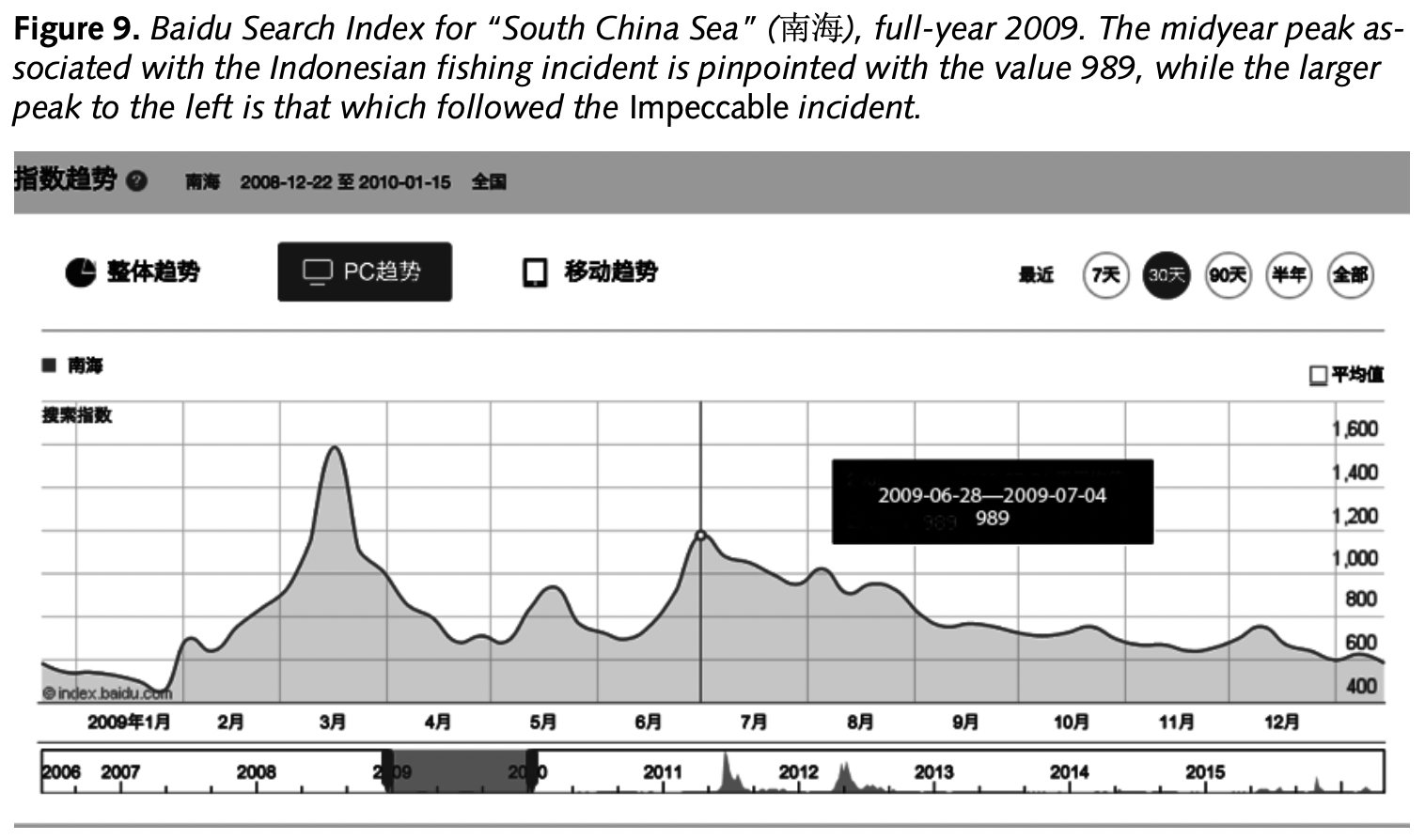

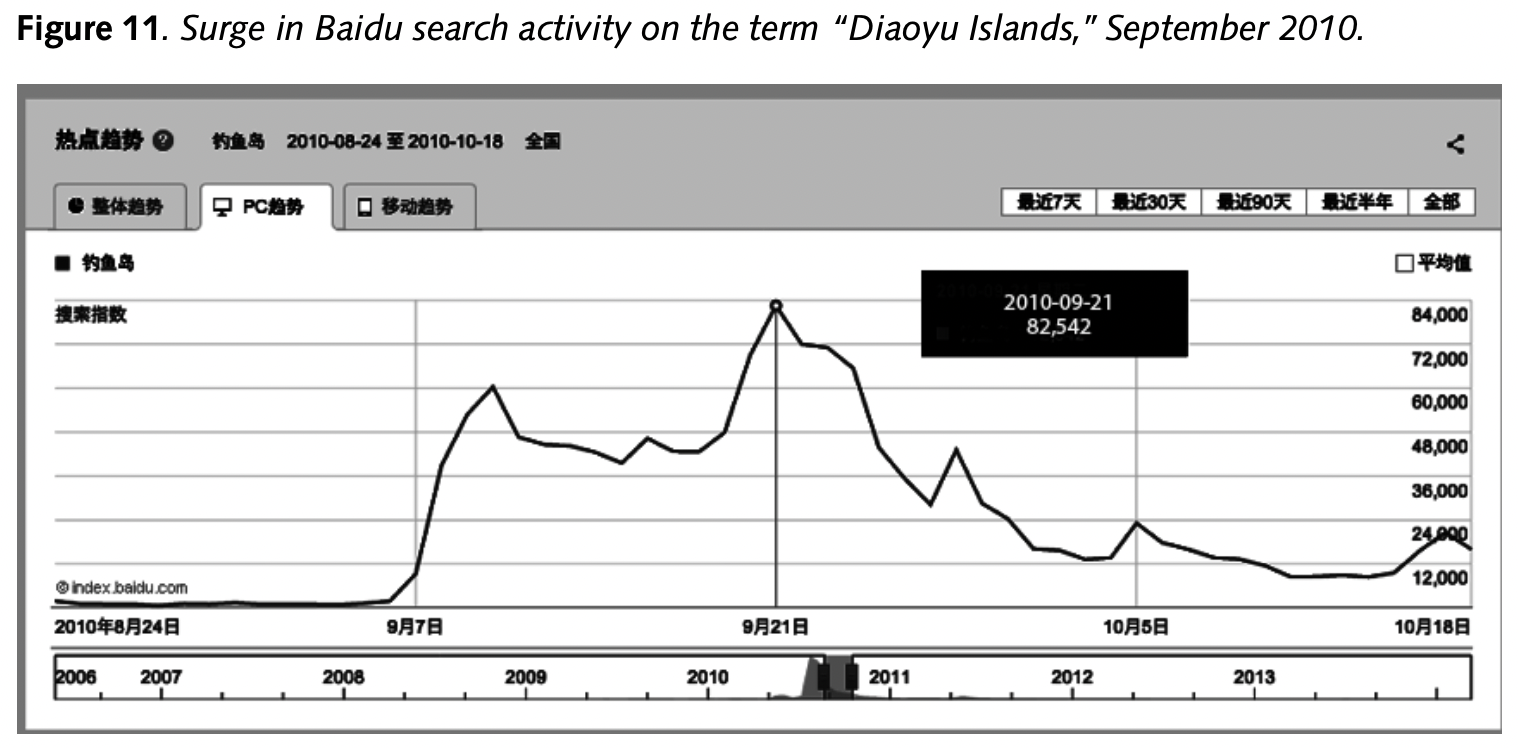

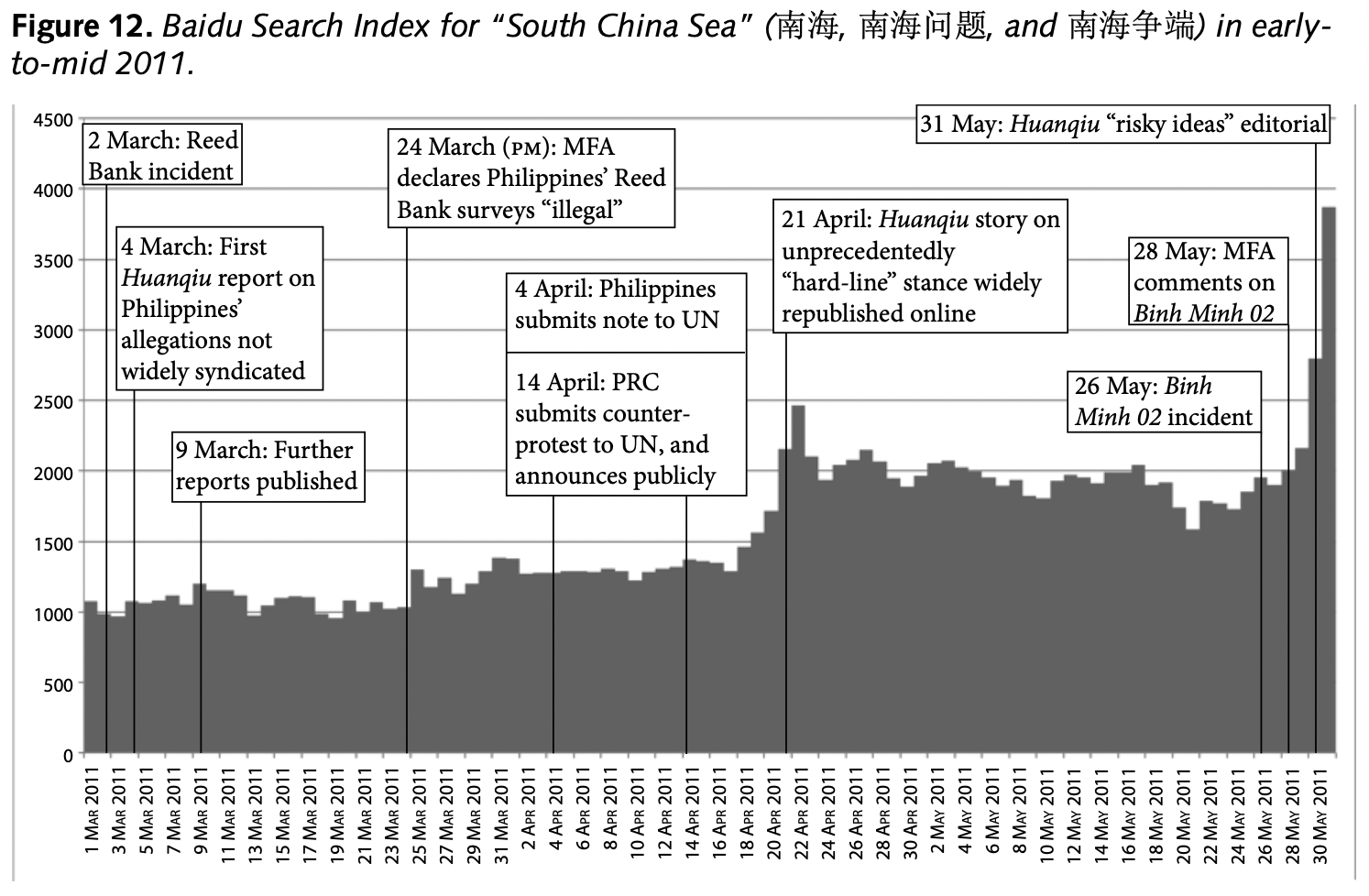

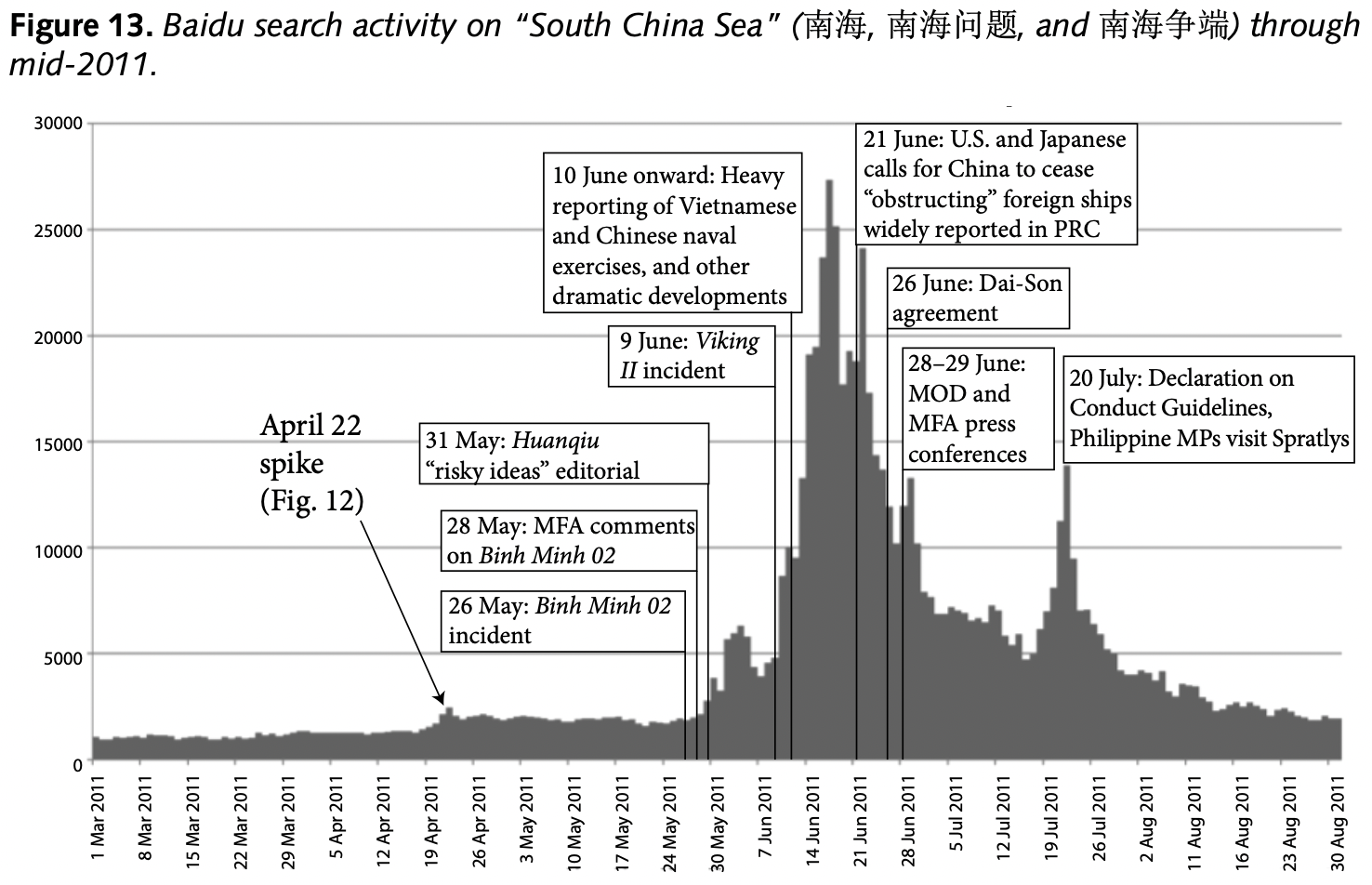

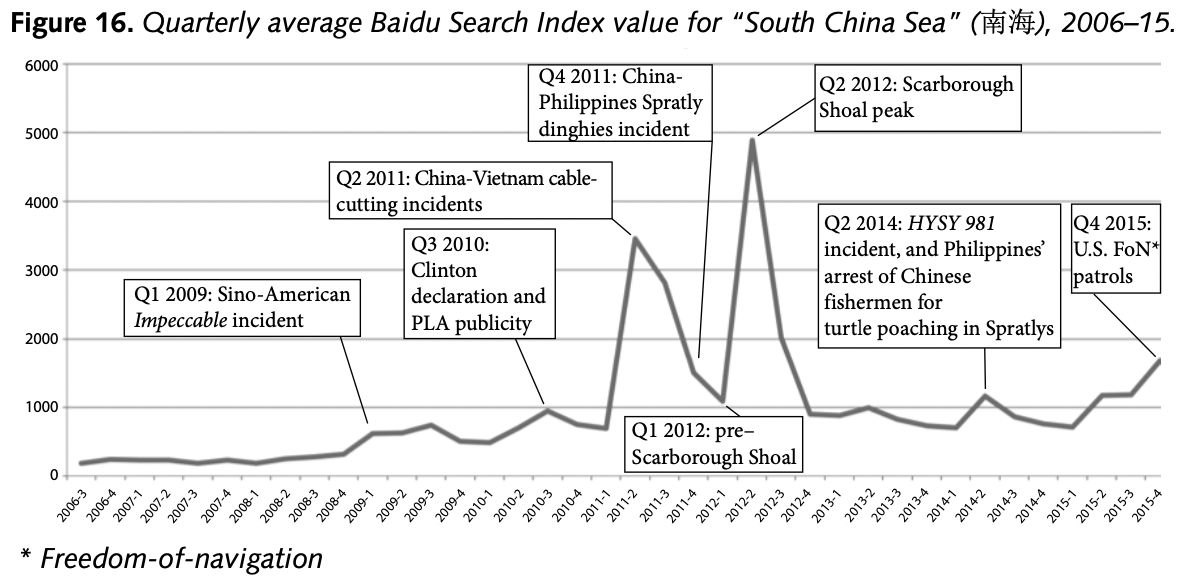

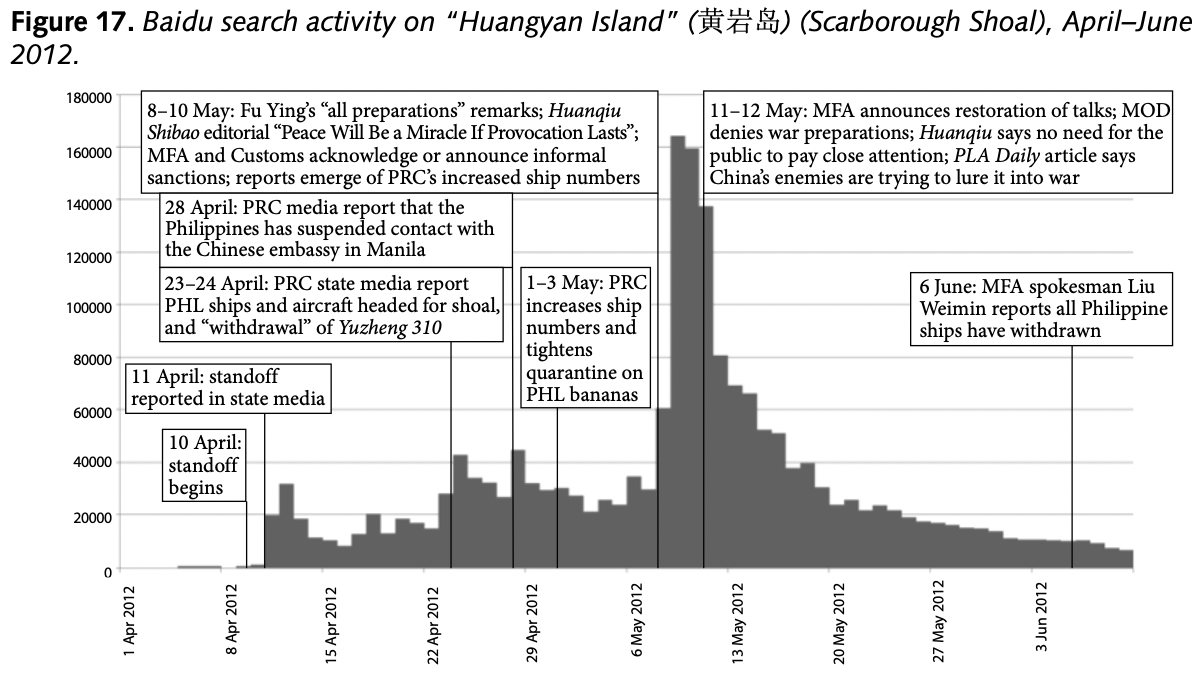

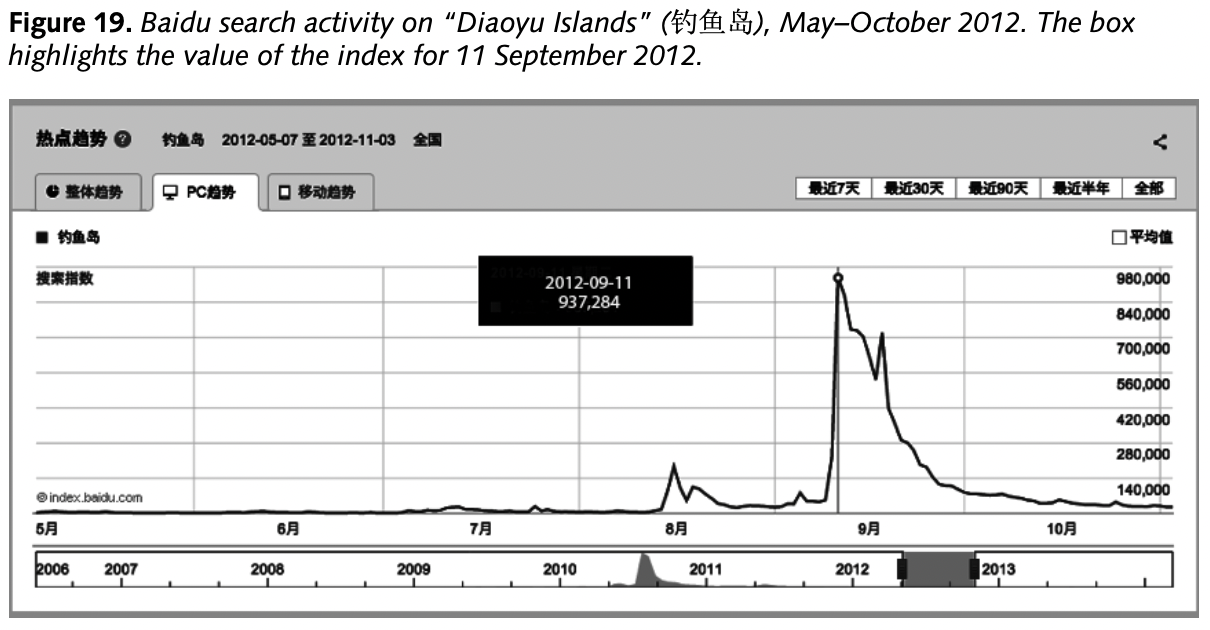

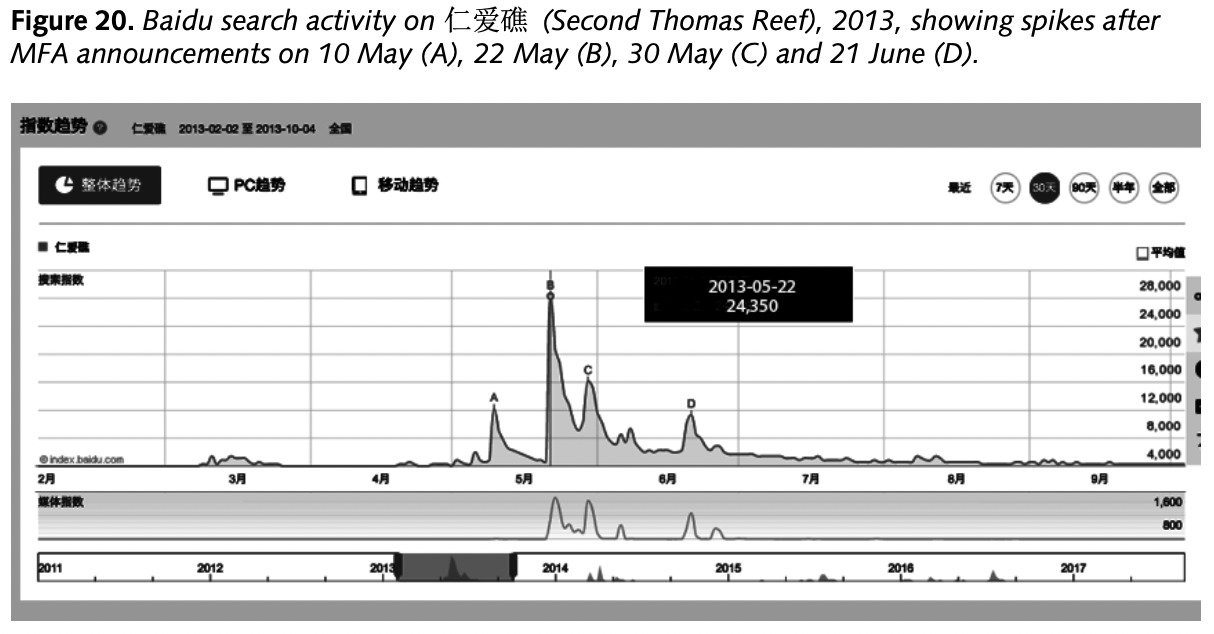

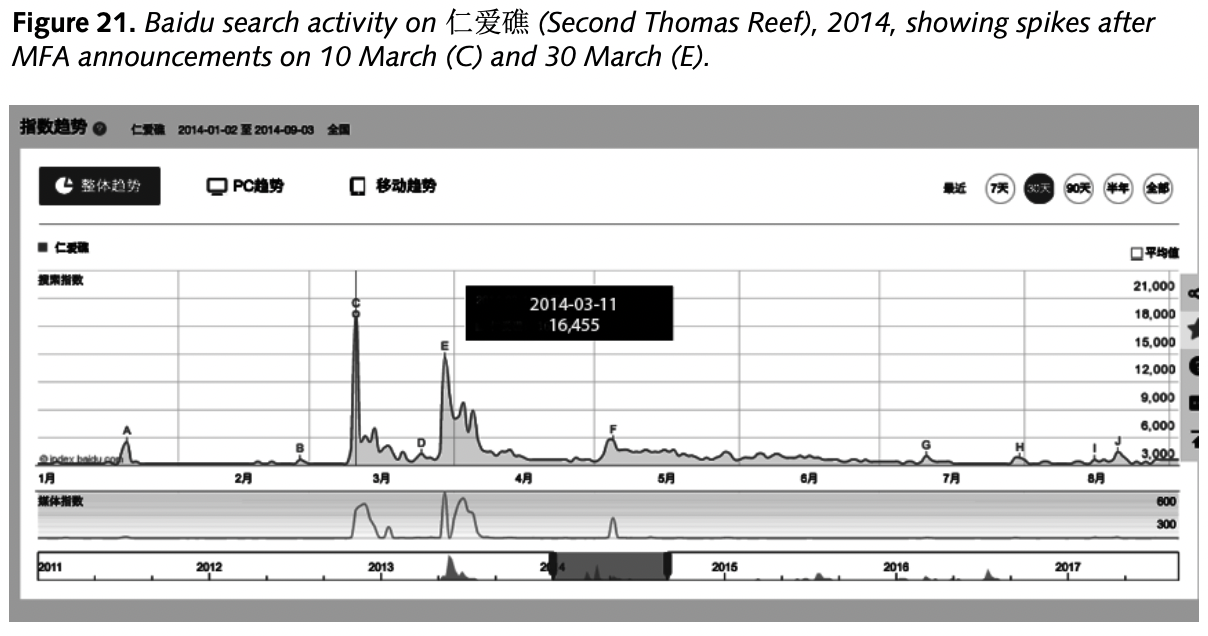

Andrew Chubb, Chinese Nationalism and the “Gray Zone”: Case Analyses of Public Opinion and PRC Maritime Policy, Naval War College China Maritime Study 16 (May 2021).

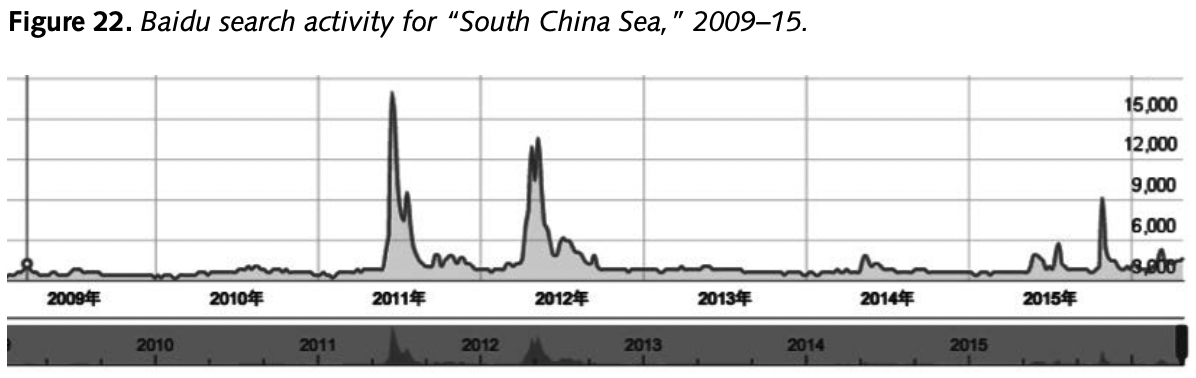

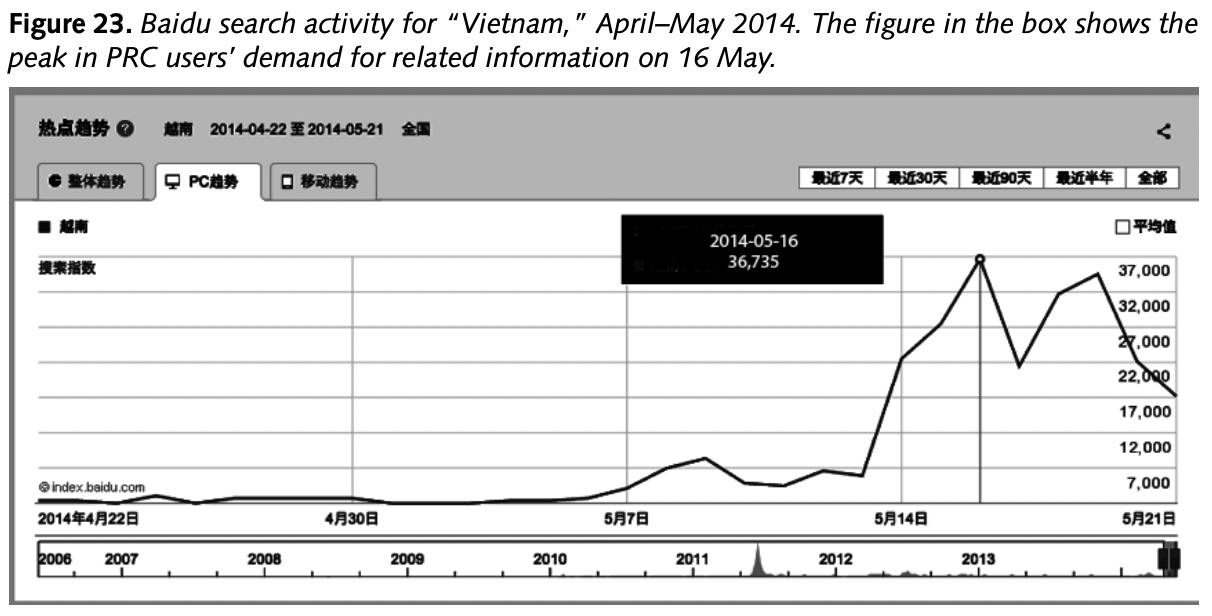

This volume examines the role of popular nationalism in China’s maritime conduct. Analysis of nine case studies of assertive but ostensibly nonmilitary actions by which the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has advanced its position in the South and East China Seas in recent years reveals little compelling evidence of popular sentiment driving decision-making. While some regard for public opinion demonstrably shapes Beijing’s propaganda strategies on maritime issues, and sometimes its diplomatic practices as well, the imperative for Chinese leaders to satisfy popular nationalism is at most a contributing factor to policy choices they undertake largely on the basis of other considerations of power and interest. Where surges of popular nationalism have been evident, they have tended to follow after the PRC maritime actions in question, suggesting instead that Chinese authorities channeled public opinion to support existing policy. … … …

Ryan D. Martinson, Echelon Defense: The Role of Sea Power in Chinese Maritime Dispute Strategy, Naval War College China Maritime Study 15 (February 2018).

Since 2006, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has pursued an expansionary agenda in disputed areas of the East and South China Seas. Its primary objective: assert administrative control over all of Chinese-claimed maritime space. To this end, it has relied on a novel approach for employing sea power, which Chinese strategists call “echelon defense.” China’s maritime forces are often disposed on two lines. On the front line are unarmed or lightly armed coast guard forces. Acting on the pretext of routine law enforcement, they physically demonstrate China’s claims and enforce these claims in the face of foreign resistance. Instead of armed force, Chinese coastguardsmen use verbal threats backed up by nonlethal measures such as bumping or ramming foreign vessels, loud sirens, and powerful water cannons. Behind the coast guard, on the second line, lies the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy (PLAN). The presence of gray-hulled Chinese warships in disputed areas ensures escalation dominance, forcing other claimants to compete on China’s terms. Because the PRC operates by far the world’s largest coast guard fleet, other states are often helpless to respond. Using this approach, China has dramatically enhanced its ability to influence the course of events in strategically important areas of the Western Pacific. By acting gradually and opportunistically, Chinese surface forces have expanded control over contested space without armed conflict, and without jeopardizing the primary objective of Chinese grand strategy: economic development. This monograph examines China’s use of “echelon defense” since 2006. Relying on hundreds of original Chinese sources, it illuminates how Beijing sees the role of sea power in its maritime dispute strategy, offering empirically-based conclusions about the strategic calculus underlying Chinese behavior at sea. … … …

Peter A. Dutton and Ryan D. Martinson, eds., China’s Evolving Surface Fleet, Naval War College China Maritime Study 14 (July 2017).

This edited volume focuses on the development of China’s surface navy, the roles and missions of this evolving fleet, and the strategic ramifications of such development. Major themes include the capacity, organization and control, and support of China’s surface fleet; the aircraft carrier as a new element therein; and U.S. and international views concerning the overall implications. Specific chapter topics include China’s amphibious force and missile craft, the interconnection between China’s Surface Fleet Developments and its maritime strategy, the significance of China’s surface fleet in PLA doctrinal writings, the PLAN destroyer force, Chinese deck aviation, Far Seas operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond, the evolution of PLAN logistics and maintenance, and international perspectives. … … …

Peter A. Dutton and Ryan D. Martinson, eds., Beyond the Wall: Chinese Far Seas Operations, Naval War College China Maritime Study 13 (May 2015).

Much has been written about Chinese sea power in the “near seas” of East Asia—those waters located within the chain of islands extending from the Kurils in the north to Sumatra in the south. This volume attempts to broaden the discussion by examining China’s efforts to shape its navy to meet new and growing needs beyond Asia, in waters to which it usually refers as the “far seas,” or “distant seas.” Remote from domestic bases of support, the far seas impose a range of logistical and operational challenges on the PLA Navy. But this distance from the Chinese homeland also provides new opportunities for cooperation with the other navies of the world, creating a much-needed antidote to the growing tensions east of Malacca.

This all raises important questions: As China moves more confidently beyond the East Asia region, what roles will China’s maritime power play in protecting China’s evolving far seas interests? How will China’s navy contribute to stability in the global commons? Will China’s approach to foreign policy and international law evolve or change; and, if so, how? How might these changes affect the relationship between Chinese and American maritime power? In addressing these questions, this volume addresses the links between China’s evolving overseas national interests, its evolving foreign policy perspectives, its perspectives on international law of the sea, and its naval and maritime development. It also considers how these developments might support a cooperative approach to global maritime stability—especially outside East Asia. China’s global interests are increasing and recent operations in the Gulf of Aden, hospital ship operations in Africa and the Caribbean, and ship operations in the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf, in combination with new force structure and doctrinal developments, suggest the PLAN is also developing the capacity to operate more effectively beyond the near seas to influence events that affect China’s expanding interests. … … …

Kenneth Allen and Morgan Clemens, The Recruitment, Education, and Training of PLA Navy Personnel, Naval War College China Maritime Study 12 (August 2014).

Looking back at the parlous state of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in the early 1980s, Liu Huaqing, its former commander, wrote, “All areas [of the navy] required significant strengthening, but I believed the key was developing capable personnel.” Indeed, during Admiral Liu’s tenure (1982-88), the PLAN embarked on a major effort to improve the quality of its officers and enlisted personnel an effort that continues to this day. This historically-informed monograph examines the results of reforms of the way in which the PLAN recruits, educates, and trains its officers and enlisted personnel today. … … …

Peter A. Dutton, Andrew S. Erickson, and Ryan D. Martinson, eds., China’s Near Seas Combat Capabilities, Naval War College China Maritime Study 11 (February 2014).

This edited volume explores China’s claims and capabilities within and around the ‘First Island Chain,’ the so-called ‘Near Seas.’ It assesses the rapidly evolving situations of concern in the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea, and South China Sea; and related capabilities, doctrinal development, and plausible scenarios. It concludes with discussion of possible U.S. Navy responses to China’s ‘Near Seas’ strategy. … … …

Andrew S. Erickson and Austin M. Strange, No Substitute for Experience: Chinese Anti-Piracy Operations in the Gulf of Aden, Naval War College China Maritime Study 10 (November 2013).

In this carefully researched, comprehensive, and highly detailed study, the authors address six major aspects of China’s anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden since their inception in December 2008: Modern Piracy and the Relevance to China; Institutional Underpinnings: Domestic Political and Policy Issues; China’s Views on Multilateral Coordination; China’s Recent Antipiracy Activities in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean; Operational Trajectories; and Lessons Learned and Implications for Global Maritime Governance. The authors conclude that through these operations “China’s navy has accrued know-how … that it could not have gained otherwise. It has implemented [this knowledge] … with impressive speed and resourcefulness … increasing PLAN capabilities and confidence.” But, the authors caution, “China’s process of gaining Far Seas experience is not simply one of increasing naval capabilities–it is far broader. Antipiracy operations conveniently enable China both to respond to internal and external pressures to act on the international stage and to raise significantly the overall ability of its increasingly powerful navy.” … … …

Lyle J. Goldstein, ed., Not Congruent but Quite Complementary: U.S. and Chinese Approaches to Nontraditional Security, Naval War College China Maritime Study 9 (July 2012).

This edited volume is unique in several respects, and not only because it offers both Chinese and American perspectives side by side. First and foremost, the assembled papers offer a glimpse into the rapidly developing and wide-ranging Chinese-language discussion about non-traditional security (NTS) issues and their role in Beijing’s future foreign policy. A plethora of Chinese citations attest to the careful efforts that have been made to synthesize this important literature, heretofore largely inaccessible to Western scholars. In addition, the volume includes both the views of policy insiders and also the ideas of individuals outside of government. Indeed, many of the authors do not shy away from challenging current policies. What this volume is not is a rote recitation of “happy talk.” The analyses are clear-eyed about certain limits with respect to NTS capabilities and sensitive regarding the implications of certain divergent views on NTS issues for the bilateral relationship overall. The assembled papers broadly assess the full scope of the bilateral NTS relationship and simultaneously dive deeply into crucial case studies, in such vital areas as counterpiracy and peacekeeping. Finally, as befits the work of an institute focused on maritime studies, there is a distinct focus on maritime issues, including a chapter on maritime counterterrorism, without ignoring key developments ashore that are crucial components to addressing any NTS challenges and to furthering the bilateral relationship as a whole.

A strong consensus at the conference and among the chapters that follow emerges that new Chinese interest in and capabilities for NTS operations offer a vital strategic opportunity to enhance U.S.-China security cooperation. The chapters also reveal that while American and Chinese viewpoints on NTS issues are hardly congruent, they are surprisingly complementary. It is therefore hoped that this volume will help to build the foundation of a more cooperative pursuit of Chinese and American national interests and of international security more generally. … … …

David Curtis Wright, The Dragon Eyes the Top of the World: Arctic Policy Debate and Discussion in China, Naval War College China Maritime Study 8 (August 2011).

The Chinese are increasingly interested in the effects of global climate change and the melting of the Arctic ice cap, especially as they pertain to emergent sea routes, natural resources, and geopolitical advantage. China seems to see the overall effect of Arctic climate change as more of a beckoning economic opportunity than a looming environmental crisis. Even though it is not an Arctic country, China wants to be among the first states to exploit the region’s natural resource wealth and to ply ships through its sea routes, especially the Northwest Passage. The Arctic is currently quite topical in China, and articles on China’s newfound interest in Arctic affairs now appear with some frequency in major academic journals, as well as in the popular media. There is currently something of a cacophony of Chinese voices on Arctic affairs, and this is because Chinese Arctic policy has not been fully formulated or promulgated. There does, however, seem to be a current consensus within Arctic policy debate, discussion, and deliberation in China, and that is that the Arctic belongs to all humankind and not to any one country or group of countries. But herein is a quandary for China, which has a long and assertive record of insisting on sovereign state rights as the paramount principle of international relations. … … …

Peter A. Dutton, Military Activities in the EEZ: A U.S.-China Dialogue on Security and International Law in the Maritime Commons, Naval War College China Maritime Study 7 (December 2010).

China is attempting to assemble the technology to challenge the U.S. Navy’s access to the western reaches of “its” lake and thereby challenge the political access that American naval power now ensures. China has also mobilized its lawyers. Its international-law specialists have become adjunct soldiers in China’s legal campaign to challenge the dominant, access-oriented norms at sea, especially for military freedoms of navigation in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This expanse of waters, known as the EEZ, stretches two hundred nautical miles from a coastal state’s shores and collectively constitutes more than a third of all ocean space. Because the EEZ is a rich resource zone and a region through which all major sea-lanes pass, its space is critical to regional political stability, national resource extraction, and global commerce. For the United States, the world’s EEZs are therefore critical regions in which naval power must be brought to bear in support of two fundamental sources of stability for the global system: deterrence of international armed conflict and suppression of nontraditional threats to commerce and other activities. For China, however, its EEZ and other jurisdictional waters are zones in which outside interference is an unwelcome intrusion into domestic security issues, a zone of competition for resources with neighboring states that claim overlapping rights, and a region in which national, not international, maritime power should dominate.

This volume is the product of a workshop held in Newport in July 2009 to discuss the different perspectives held by the United States and China on the legitimacy of foreign military activities in a coastal state’s EEZ. The conference, addressing “The Strategic Implications of Military Activities in the EEZ,” was attended by fifty representatives of the American and Chinese policy, military, legal, and academic communities. Its aims were to increase mutual understanding of the bases for each state’s perspectives and to add a dimension of richness to ongoing talks between the two countries under the framework of the Defense Consultative Agreement and the Military Maritime Consultative Agreement. Eight papers from workshop participants are reproduced here. … … …

David Griffiths, U.S.-China Maritime Confidence Building: Paradigms, Precedents, and Prospects, Naval War College China Maritime Study 6 (July 2010).

As two great powers that will influence much of the immediate future of our small and vulnerable planet, China and the United States are in a marriage of sorts. Like it or not, the two societies depend on each other. Environmental degradation, social unrest, economic problems, or pandemic outbreak in one must inevitably affect the other. Both must be active contributors to a peaceful, prosperous, sustainable, global community. Both governments emphasize their commitment to a positive and constructive mutual engagement. At sea, however, that engagement is not always trouble free. Confrontation happens—and when it does, events do not always unfold in the way that policy makers might have intended or preferred. Like a married couple, both sides prefer to downplay to the outside world the extent and nature of quarrels. But despite this public posture, those in command of naval and maritime air forces understand only too well the potential risks of damage, injury, and even death at the tactical level. More worrying is the inherent risk of unintended consequences and the potential for an uncontrolled strategic-political spiral of unwanted escalation. It is bad policy and in no one’s interest to perpetuate a relationship in which an innocent mistake at sea can trigger an unwanted political crisis.

The maritime relationship between China and the United States is a vital element in their relationship and a strategic concern for other states. Their tactical-level interaction at sea is too complex to be governed solely by legal arrangements and political postures. It is too important to be conducted on-scene by best guesses about each other’s intentions, especially when things get exciting and the testosterone and adrenaline start flowing. And when things do go wrong, the resulting political fallout can be too serious to be addressed by rhetoric and dogmatic adherence to rigid positions. Interactions at sea are inherently fluid and must be managed mutually, responsibly, and predictably. At the moment, the maritime relationship between China and the United States is not working as effectively as it should—or must. The business of government is to manage events and minimize risk, so no political leadership should be satisfied with a situation in which an honest misjudgment or accident at sea can result in an unwanted international political problem at an inopportune time. … … …

Lyle J. Goldstein, Five Dragons Stirring Up the Sea: Challenge and Opportunity in China’s Improving Maritime Enforcement Capabilities, Naval War College China Maritime Study 5 (April 2010).

Today, China remains relatively weak in the crucially important middle domain of maritime power, that between commercial prowess and hard military power, which is concerned with maritime governance—enforcing a nation’s own laws and ensuring “good order” off its coasts. Despite major improvements over the last decade, China’s maritime enforcement authorities remain balkanized and relatively weak—described in a derogatory fashion by many Chinese experts as so many “dragons stirring up the sea.” In Northeast Asia, China’s weak maritime enforcement capacities are the exception, especially when compared to the coast guard capacities of Japan (or, outside the region, of the United States). Indeed, Japan’s coast guard was recently described as almost, if not quite, a second navy for Tokyo.

China’s relative weakness in this area is a mystery, one that forms the central research question of the present study. This condition of relative weakness is outlined in the monograph’s first part. The second part describes and analyzes the current situation of each of the five most important bureaucratic agencies responsible for maritime enforcement and governance in China today. The third part of this study raises the question of what relationships these entities, and any future unified Chinese coast guard, would have with the Chinese navy. Before turning to implications and prospects, the fourth delves into a variety of macro explanations for the weakness of China’s coast guard entities today. Part five analyzes the possibilities for future maritime security cooperation, by looking closely at U.S.-China civil maritime engagement between coast guard entities over the last decade. The final part elaborates on three possible strategic implications of enhanced Chinese coast guard capabilities. This study, as a whole, draws on hundreds of Chinese language sources, interviews in China, and, especially, a highly detailed and remarkably candid 2007 survey by Professor He Zhonglong and three other faculty members at the Border Guards Maritime Police Academy in Ningbo.

The continuing evolution of Chinese coast guard entities into more coherent and effective agents of maritime governance presents both a challenge and an opportunity for security and stability in East Asia. Enlarged capacities will naturally result in more stringent enforcement of China’s maritime claims vis-à-vis its many neighbors. However, a more benign potential result is that enhanced Chinese capacities in maritime governance may result in greater willingness by Beijing to support global maritime safety and security norms as a full-fledged and vital “maritime stakeholder.” … … …

Nan Li, Chinese Civil-Military Relations in the Post-Deng Era: Implications for Crisis Management and Naval Modernization, Naval War College China Maritime Study 4 (January 2010).

This study addresses two analytical questions: What has changed in Chinese civil-military relations during the post–Deng Xiaoping era? What are the implications of this change for China’s crisis management and its naval modernization? Addressing these questions is important for three major reasons. First, because the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is a party army, it is commonly assumed that its primary function is domestic politics—that is, to participate in party leadership factional politics and to defend the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) against political opposition from Chinese society. For the past twenty years, however, the PLA has not been employed by such party leaders as Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao against political opposition from either the CCP or Chinese society. The PLA’s ground force, which is manpower-intensive and therefore the most appropriate service for domestic politics, has been continuously downsized. Technology and capital-intensive services that are appropriate for force projection to the margins of China and beyond and for strategic deterrence but are inappropriate for domestic politics—such as the PLA Navy (PLAN), the PLA Air Force (PLAAF), and the Second Artillery (the strategic missile force)—have been more privileged in China’s military modernization drive. This study, by examining change in Chinese civil-military relations, undertakes to resolve this analytical puzzle.

Second, China’s civil-military interagency coordination in crisis management during the post-Deng era has remained an area of speculation, for lack of both information and careful analysis. By analyzing change in Chinese civil-military relations, this study aims to shed some light on this analytical puzzle as well. Finally, the PLAN was previously marginalized within the PLA, partly because the latter was largely preoccupied with domestic issues and politics, where the PLAN is not especially useful. By exploring change in Chinese civil-military relations, this study also attempts to explain why during the post-Deng era the PLAN has become more important in China’s military policy. … … …

Andrew S. Erickson, Lyle J. Goldstein, and William S. Murray, Chinese Mine Warfare: A PLA Navy ‘Assassin’s Mace’ Capability, Naval War College China Maritime Study 3 (June 2009).

While photos of a first Chinese aircraft carrier will no doubt cause a stir, the Chinese navy has in recent times focused much attention upon a decidedly more mundane and non-photogenic arena of naval warfare: sea mines. This focus has, in combination with other asymmetric forms of naval warfare, had a significant impact on the balance of power in East Asia. In tandem with submarine capabilities, it now seems that China is engaged in a significant effort to upgrade its mine warfare prowess. Submarines are large and difficult to hide, and various intelligence agencies of other powers are no doubt attuned to the scope and dimensions of these important developments. By contrast, mine warfare (MIW) capabilities are easily hidden and thus constitute a true “assassin’s mace” (杀手锏 or 撒手锏)—in the American metaphor, a “silver bullet” for the PLA Navy, a term some Chinese sources, including the PLAN itself, apply explicitly to MIW. Relying heavily on sea mines, the PLAN is already fully capable of blockading Taiwan and other crucial sea lines of communication in the western Pacific area. Indeed, sea mines, used to complement a variety of other capabilities, constitute a deadly serious challenge to U.S. naval power in East Asia.

This monograph proceeds in ten steps. First, there is a discussion of the Persian Gulf War as a catalytic moment for contemporary Chinese MIW. A second section develops this context further with an account of the little-known history of Chinese MIW. The next two sections consist of detailed descriptions of the PLAN mine inventory and the various means of delivery. A fifth section addresses the human factor in Chinese MIW development, outlining recent training and exercise patterns. The following section offers a provisional outline of the PLAN’s evolving MIW doctrine. The seventh section brings prospective mine countermeasures (MCM) programs into the strategic equation, and the eighth discusses specific scenarios of concern, especially the Taiwan blockade scenario, aiming for a comprehensive net assessment of the MIW component in the future Asia-Pacific maritime security environment. The discussion of scenarios is followed by an evaluation of an alternative viewpoint concerning Chinese MIW potential. In the tenth, concluding, section, implications are discussed for U.S. defense and foreign policy. … … …

Peter A. Dutton, Scouting, Signaling, and Gatekeeping: Chinese Naval Operations in Japanese Waters and the International Law Implications, Naval War College China Maritime Study 2 (February 2009).

The Han incident was not the first (or last) incursion to cause the JMSDF to exercise its submarine-hunting and -tracking capabilities. Over the past decade, the Japanese have observed more frequent submarine operations activities in the western and northern reaches of the East China Sea by China’s increasingly capable submarine force. As recently as October 2008, for instance, several news reports and abundant Internet chatter reported that the JMSDF had detected two Chinese submarines—a Han and a Song—waiting for the aircraft carrier USS George Washington, newly based in Japan as the replacement for the USS Kitty Hawk, as it transited from its home port at Yokosuka Naval Base near Tokyo en route to a routine port visit in Pusan, South Korea. Reportedly the Chinese submarines remained outside Japanese territorial waters, but reports also suggest that the missions of the PLAN vessels may have been to gather intelligence on the acoustic and electronic signatures of the carrier and to signal China’s keen interest in American naval presence in the region. Perhaps the Han, relatively noisy and certain to be detected, accompanied the quieter, diesel-driven Song attack submarine to make sure this strategic signal was received. In any case, these operations appear to have been designed to detect and monitor American fleet movements from Japanese bases, and perhaps to remind the United States and Japan of the increasing strength of China’s submarine-borne anti-access capabilities.

Each of China’s naval activities discussed above appears to have had intelligence collection or political signaling as a core purpose, but a key difference between most Chinese naval operations and the Han’s passage though the Ishigaki Strait is that the Han clearly passed submerged through an area of Japanese territorial seas in which both the Chinese and Japanese perspectives on international law of the sea appear to agree that, in order to pass lawfully, submarines must be on the surface and flying their flag—if they pass at all. In the remaining cases of Chinese naval activity in Japanese straits, the existence of a corridor in which high seas freedoms apply provides a channel that the vessels of all states may pass through in whatever mode they desire. Thus, whereas both the Japanese and Chinese governments viewed the 2004 submerged passage of the Han through the Ishigaki Strait as a violation of coastal-state rights, all parties agree that the passage of ships and submarines through the “high seas corridor” routes in the Tsushima, Tsugaru, and Osumi straits were fully in compliance with international law—even if those ships were accompanied by a submerged submarine.

Chinese surface and submarine fleet activities in Japanese waters over the last decade suggest that China is maximizing its use of lawful operations—and even some operations that it appears to view as contrary to international law—to send strategic messages, to scout avenues for operations in the Pacific Ocean, and perhaps to find methods to control access to the littoral waters of East Asia during times of crisis. Accordingly, this study examines the current state of the Chinese submarine fleet and looks through the lens of international law at recent Chinese naval activities—primarily submarine—in and around the Japanese Archipelago. The study places special emphasis on legal analysis of the 2004 passage of a Chinese Han-class submarine on an underwater excursion through the Ishigaki Strait as the counterexample to Chinese operations that appear largely to have been planned to ensure consistency with international law, in order to assess the importance of the November 2004 event in the overall scheme of China’s regional operations and to draw conclusions about the impact of this event on international law. … … …

Gabriel B. Collins and Lieutenant Commander Michael C. Grubb, U.S. Navy, A Comprehensive Survey of China’s Dynamic Shipbuilding Industry: Commercial Development and Strategic Implications, Naval War College China Maritime Study 1 (August 2008).

China’s dynamic shipbuilding sector now has the attention of key decision makers in Washington. During testimony before the Armed Services Committee of the House of Representatives on 13 December 2007, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral Gary Roughead observed, “The fact that our shipbuilding capacity and industry is not as competitive as other builders around the world is cause for concern.” Pointing directly to Beijing’s new prowess in this area, he concluded, “[China is] very competitive on the world market. There is no question that their shipbuilding capability is increasing rapidly.” The present study aims to present a truly comprehensive survey of this key sector of the growing Chinese economy. In doing so, it provides decision-makers and analysts with the clearest possible picture of the extraordinary pace of activity now under way in China’s ports, as well as the commercial and strategic implications flowing from this development. … … …