Friends with “No Limits”? A Year into War in Ukraine, History Still Constrains Sino-Russian Relations

Andrew S. Erickson, “Friends with ‘No Limits’? A Year into War in Ukraine, History Still Constrains Sino-Russian Relations,” Harvard Fairbank Center Blog Post, 21 February 2023.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD A FULL-TEXT PDF.

A year after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, are China and Russia still friends with “no limits?” Since embracing that phrase, Chinese President Xi Jinping has publicly obfuscated regarding ties with Moscow. Meanwhile, ever stronger economic relations—including a doubling of bilateral trade—have offered much-needed support for President Vladimir Putin in the face of Western pressure. Could Chinese contributions undermine EU, U.S., and G7 country sanctions and prolong Putin’s war? What are the prospects for Sino-Russian partnership in politics, defense, and intelligence? How might a new China-Russia axis alter the global order?

February 24 marks the one-year anniversary of Putin’s devastating Ukraine invasion. Among its many reverberations are tremendous ramifications for Sino-Russian relations, which continue to deepen despite lingering differences between the two powers and the autocrats leading them. Emerging potential impacts include increasing energy and resource transactions, alignment in the form of international strategic coordination and demonstrations of their partnership on the world stage, collaboration in military technology and operations, and maritime-security advances.

Xi may even regard developments in Ukraine as the opening salvo in a broad East-versus-West confrontation for control of the international system. This would be in keeping with his signature assessment that “the world is undergoing profound changes unseen in a century, but time and situation are in our favor”—and that attendant changes promise to shift the international system away from the American/Western dominance that he and Putin oppose. Yet complicated bilateral dynamics and history suggest that the future of Sino-Russia relations could include collaboration, codependence, or confrontation—even elements of all three.

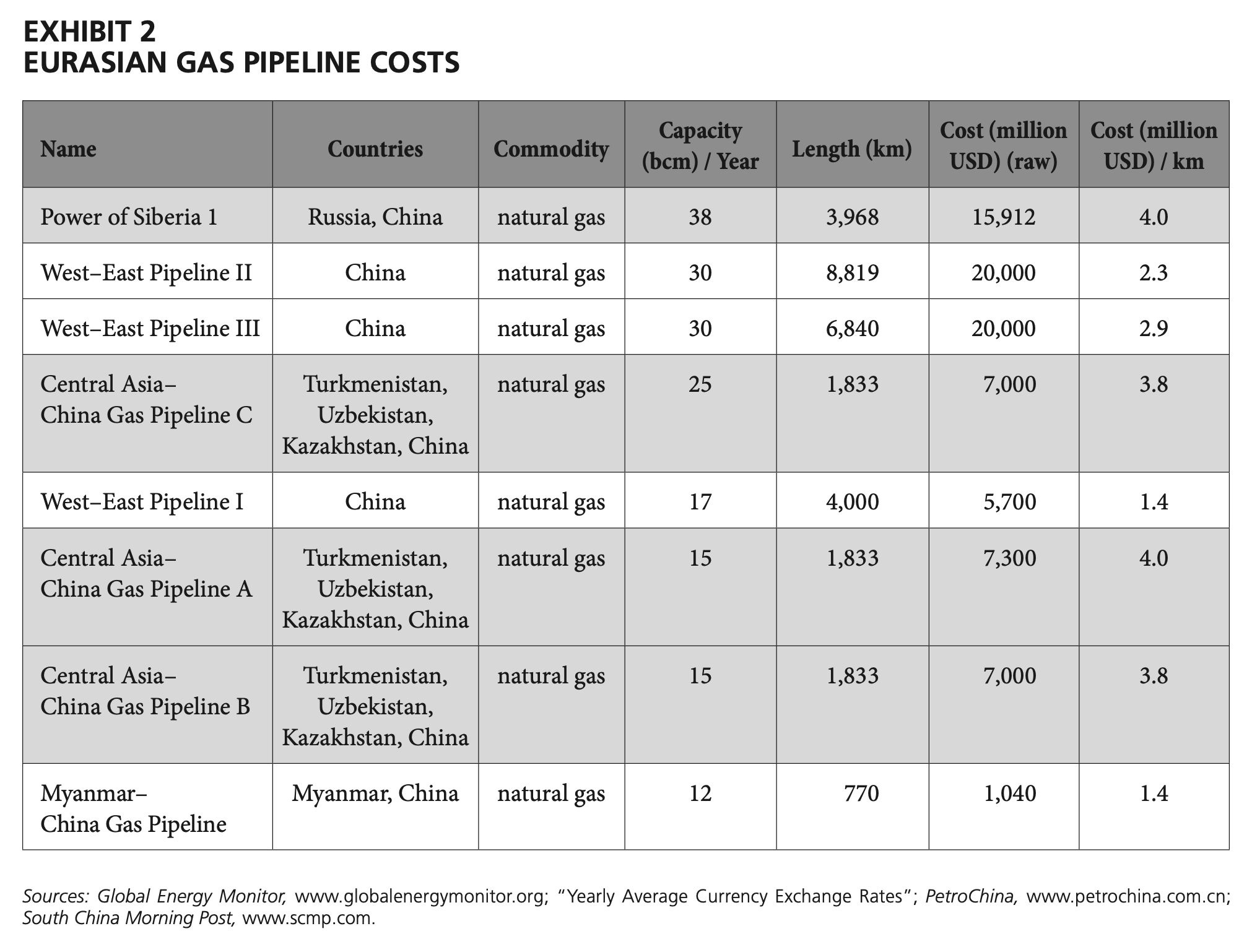

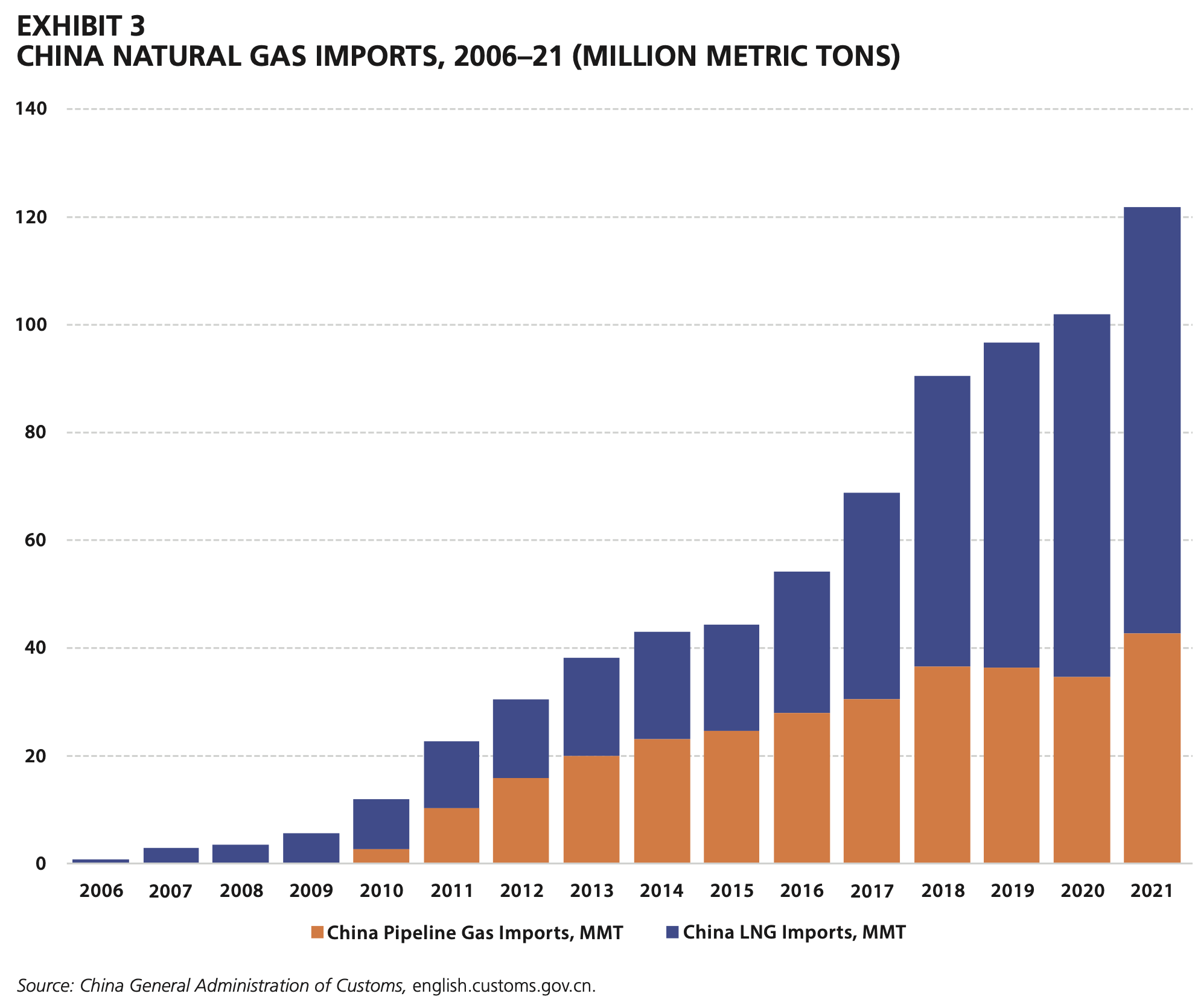

Already Russo-Chinese energy, resource, and financial transactions have grown considerably. Less visible but similarly consequential is the sharing of military technology, possibly to be complemented with sharper intelligence on U.S. and allied military forces. A truly transformational possibility would be Russian granting China access to its air and naval bases in its Far East and High North/Arctic.

A Moscow under continued duress and isolation could yield far more than cheaper oil and gas for Beijing. Russian military crown-jewel technologies—particularly in the undersea-warfare realm—could be coupled with China’s financial resources and industry to tip the Indo-Pacific security balance in favor of a Sino-Russian axis of autocracy at the expense of the United States and its allies and partners.

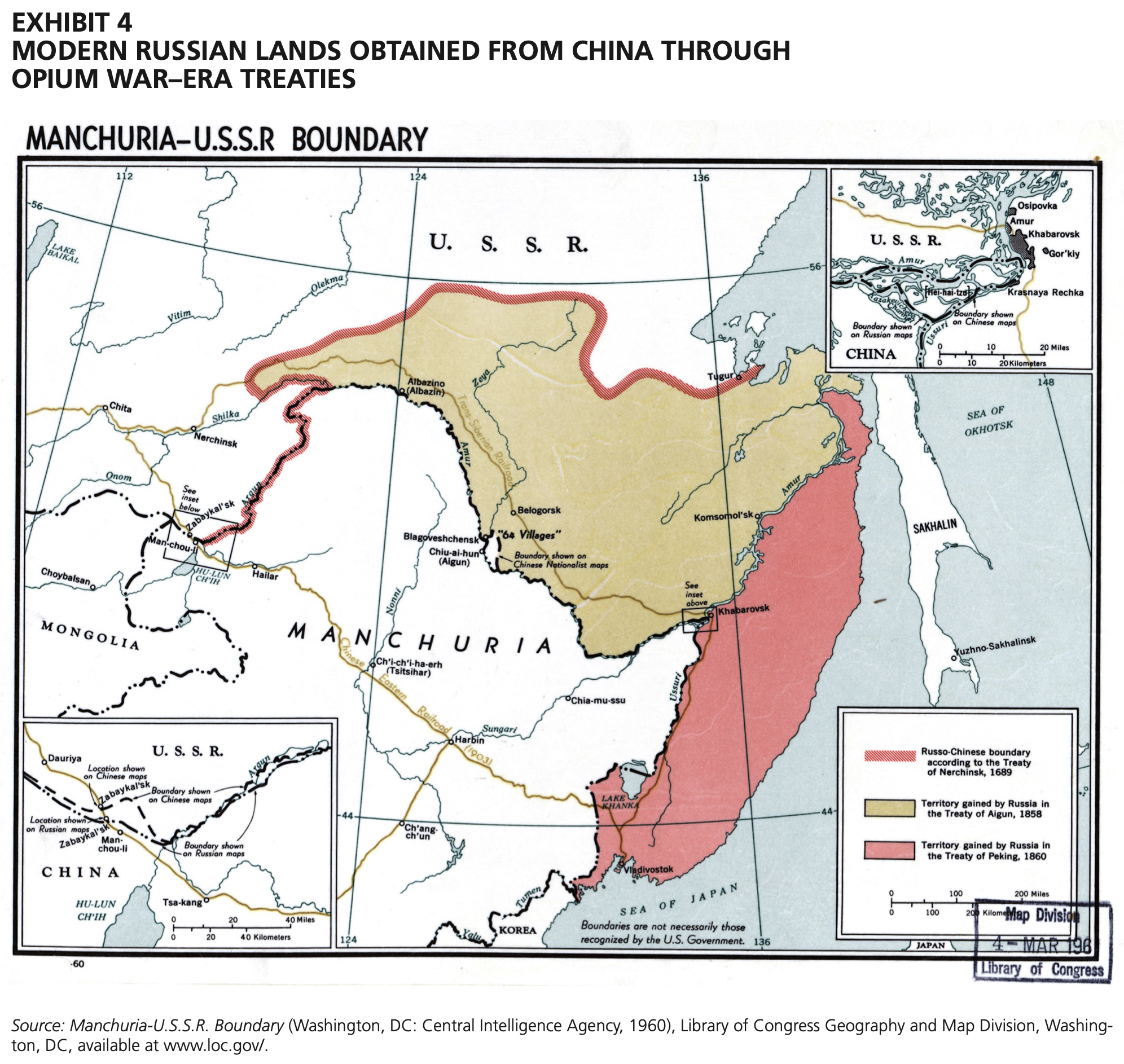

The relationship between the two historically aggrieved great powers is highly complex, however. Despite strong incentives for far-reaching entente, a panoply of factors could constrain, divert, or even derail their interaction. China and Russia’s centuries-old relationship resounds with cycles of mutual suspicion, temporary modus vivendi, and repeated division. Existential concerns have periodically overshadowed positive-sum prospects, arguably since the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk that first defined their initial mutual border and market access. Exigencies of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war neither fundamentally change the reality that a weakened Russia could arouse irredentist aspirations in China; nor eliminate fears among Russia’s present leaders, or its populace, regarding China’s long-term ambitions.

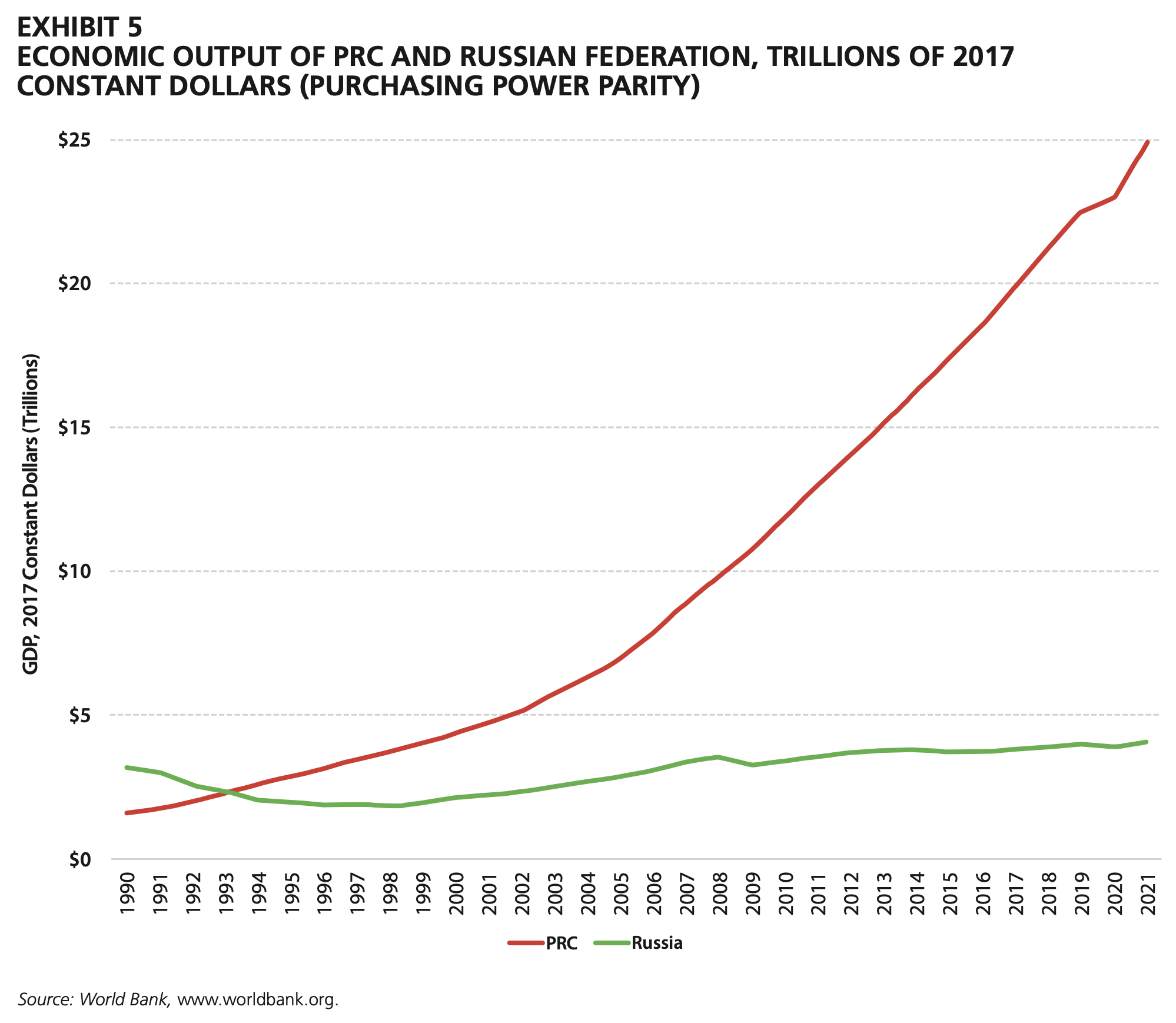

No matter how severely damaged and marginalized by war, Russia will recoil from being regarded as a vassalized basket case responsible chiefly for meeting China’s resource demands. Such a vision is likely to rapidly generate friction points with China, the self-appointed leader of the “global South,” as it expands its already leading economic influence in Central Asia and elsewhere in Russia’s self-claimed “Near Abroad.” Moreover, in the probable event that Putin increasingly accommodates Xi’s demands in an attempt to save Russia’s economy, Russian popular resentment at national subservience may ultimately prompt Putin or whoever succeeds him to reset relations symbolically, perhaps even substantively, away from Beijing’s preferences.

The extreme complexity of the Sino-Russian relationship—both for the parties involved and regarding their combined impact—must thus be factored into projections of possible trends and outcomes. A key contradiction and friction point: China already regards Russia as unavoidably declining demographically and economically toward permanent marginalization. Yet Russia’s historical and cultural identity resists accepting a position as China’s resource-providing subaltern. Simultaneously, however, there is a complex codependency. To fulfill Xi’s ambitious vision for “enter[ing] the center stage of global affairs,” Beijing needs Moscow as a globally-recognized independent partner that both exemplifies the benefits that a China-led order provides for China’s partners and is sufficiently strong to resist mounting American and European pressure.

A year into Putin’s Ukraine War, Russo-Chinese relations should be assessed carefully. The equations likely to govern their evolution and attendant geo-economic and geopolitical shifts are dynamic and multivariate. Assessments of future prospects must consider a range of scenarios and possibilities. One of the few certainties is that this pivotal great power relationship will continue to matter greatly.

Andrew S. Erickson is a Visiting Professor in Harvard’s Department of Government and an Associate in Research at the Fairbank Center. He is Professor of Strategy and the Research Director at the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI).

RELATED RESEARCH

Andrew S. Erickson and Gabriel B. Collins, “Putin’s Ukraine Invasion: Turbocharging Sino-Russian Collaboration in Energy, Maritime Security, and Beyond?” Naval War College Review 75.4 (Autumn 2022): 91–126.

Putin’s war of choice in Ukraine will continue to send shock waves across the shores of maritime Asia for years, with unfolding impacts on ecosystems inhabited by oil barrels, gas pipelines, submarine technologies, jet engines, and basing access, within a context of a China-Russia relationship characterized over the centuries by cycles of fear, temporary bonds, and renewed division.

Enlarging the aperture of the Russo-Ukrainian war still further brings us to its potential impact on Russia’s relationship with China, and thereby also on the international position of the United States. In “Putin’s Ukraine Invasion: Turbocharging Sino-Russian Collaboration in Energy, Maritime Security, and Beyond?,” Andrew S. Erickson and Gabriel B. Collins provide some far-ranging speculations about the future of the Russia-China relationship, beginning with a look at its energy dimension. Although the Chinese had seemed to be moving toward a tighter embrace of Vladimir Putin, they have been ambivalent about his Ukrainian venture and have declined to provide the Russians with overt military assistance. Putin’s military debacle clearly has altered the terms of the relationship, with Russia now a distinctly junior partner—a situation with which the Russian leadership may become increasingly uncomfortable. Erickson and Collins make the important point that the Chinese are no longer in the position of relying on Russian/Soviet military technology transfer to provide their high-end weapons systems—with the important exception of submarine-quieting technology, which the authors suggest could form the basis for a grand bargain that could pose grave dangers for the United States in its efforts to contain the Chinese military threat in the western Pacific. They speculate further about possible increased access by the Chinese to Russian port facilities in the Far East and the Arctic.

Putin’s war of choice in Ukraine goes far beyond Javelins, the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (i.e., HIMARS), and Russia’s campaign of destruction against the second-most-industrialized post-Soviet state. Shock waves from the war now wash across the shores of maritime Asia, with years of unfolding impacts ahead. Accordingly, this article takes readers through a journey featuring ecosystems inhabited by oil barrels, gas pipelines, submarine technologies, jet engines, and basing access. It also will explore China and Russia’s centuries-old relationship cycle of fear, temporary bonds of common cause, and division anew.

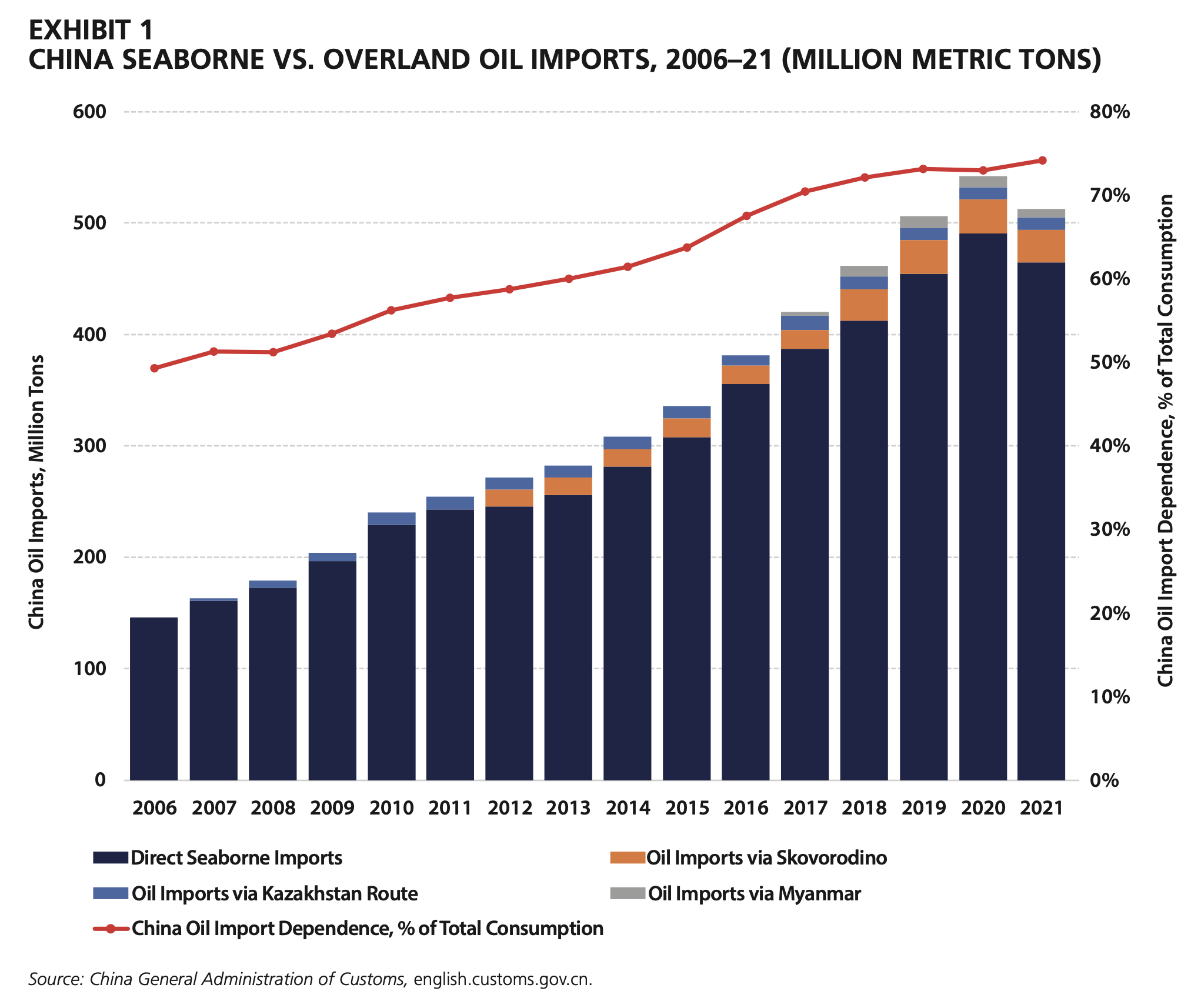

In coming months and years, China will tap the Russian raw material storehouse more deeply. But a Moscow under duress and isolation could yield far more than cheaper oil and gas; Russian military pinnacle technologies—particularly in the undersea-warfare realm—could be coupled with China’s financial resources and industry to tip the Indo-Pacific security balance in favor of a Sino-Russian axis of autocracy at the expense of the United States and its allies and partners. People’s Liberation Army (PLA) access to air and naval bases in the Russian Far East and High North, plus acoustic intelligence sharing, could make conditions in the Indo-Pacific even worse for the United States and its allies and partners.

Yet downside risk for the United States is not the only story unfolding. This article also assesses potential limiting factors that could constrain, divert, or even derail Sino-Russian interaction. Long-standing mutual suspicions have dogged the two countries’ relationship, arguably since the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk. The treaty was the first-ever such agreement between the tsardom of Russia and the Qing dynasty of China, and defined their initial mutual border and market access.1 Exigencies of the day dominate the present discourse on Russo-Chinese relations, but the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war does not eliminate concerns among Russia’s current decision makers, or its populace, regarding China’s long-term ambitions—nor does it fundamentally change the reality that a weakened Russia could arouse revisionist ambitions in China.

A Russia whose motives for aggressive military action in Europe likely include regaining the fear-based “respect” accorded the Soviet Union in the past may tire of being viewed—and perhaps treated—as a vassal of China. Indeed, scholars Fiona Hill and Angela Stent assess that Putin “wants the West and the global South to accept Russia’s predominant regional role in Eurasia. This is more than a sphere of influence; it is a sphere of control, with a mixture of outright territorial reintegration of some places and dominance in the security, political, and economic spheres of others.”2 Such a vision is likely to generate friction points rapidly with China (the self-styled leader of the aforementioned “global South”) as it deepens its already large economic presence in Central Asia. Moreover, in the probable event that Putin increasingly accommodates People’s Republic of China (PRC) demands in an attempt to shore up Russia’s economic situation, Russian popular resentment at national subservience may prompt Putin or his ultimate successor to reset relations symbolically, and even substantively, away from Beijing’s preferences. In any event, the equations likely to govern ongoing geoeconomic and geopolitical shifts are dynamic and multivariate. That being the case, this article aims to illustrate potential boundaries, identify important shaping forces, and thus create a template for understanding both ongoing processes and evolutions yet to come.

The extreme complexity of the Sino-Russian relationship—both for the parties involved and regarding their combined impact—must be factored into projections of possible trends and outcomes. A key contradiction and friction point lies in the fact that China already regards Russia as being on an unstoppable decline to permanent marginalization, as measured by key economic and demographic metrics; yet Russia’s historical and cultural identity resists accepting a position as China’s resource pool or subaltern. Simultaneously, however, there is a complex codependency; rather than merely using it as a vassal, Beijing needs Moscow as an independent partner—one globally regarded as such—that exemplifies the benefits that a China-led order provides for PRC partners and that is strong enough to hold up in the face of challenges and resistance from the United States, European Union (EU), and other entities, including in the Middle East. If, for example, PRC president Xi Jinping views events unfolding in Ukraine as the opening salvo in a broad East-versus-West confrontation for control of the international system, in keeping with his signature assessment that “the world is undergoing profound changes unseen in a century, but time and situation are in our favor,” and that the changes will shift the international system away from Western dominance, then Sino-Russian collaboration could deepen significantly.3

With such transformative possibilities in mind, this article will ground its assessments in the best available empirical data and be transparent in its assumptions and logic, but it will not shy away from examining what may well be low-probability yet high-impact possibilities. After all, few government organizations or analysts anywhere appear to have anticipated fully the scope and pace of PLA development over the last two to three decades, yet this development has enabled the dramatic overturning of cross-strait military equations and threatens to become the central security issue of this decade. … … …