“U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South & East China Seas: Background & Issues for Congress”—142nd ed. of O’Rourke’s CRS Report—Great Info on PAFMM & CCG!

If you have trouble accessing the website above, please download a cached copy here.

You can also click here to access the report via the public CRS website.

KEY EXCERPTS:

p. 9

… …

p. 10

“Salami-Slicing” Strategy and Gray Zone Operations

Observers frequently characterize China’s approach to the SCS and ECS as a “salami-slicing” strategy that employs a series of incremental actions, none of which by itself is a casus belli, to gradually change the status quo in China’s favor.30 Other observers have referred to China’s approach as a strategy of gray zone operations (i.e., operations that reside in a gray zone between peace and war),31 of incrementalism,32 creeping annexation33 or creeping invasion,34 or as a “talk and take” strategy, meaning a strategy in which China engages in (or draws out) negotiations while taking actions to gain control of contested areas.35 An April 10, 2021, press report, for example, states

China is trying to wear down its neighbors with relentless pressure tactics designed to push its territorial claims, employing military aircraft, militia boats and sand dredgers to dominate access to disputed areas, U.S. government officials and regional experts say.

The confrontations fall short of outright military action without shots being fired, but Beijing’s aggressive moves are gradually altering the status quo, laying the foundation for China to potentially exert control over contested territory across vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean, the officials and experts say….

The Chinese are “trying to grind them down,” said a senior U.S. Defense official….

“Beijing never really presents you with a clear deadline with a reason to use force. You just find yourselves worn down and slowly pushed back,” [Gregory Poling of the Center for Strategic and International Studies] said.36

***

30 See, for example, Julian Ryall, “As Regional Tensions Rise, China Probing Neighbors’ Defense,” Deutsche Welle (DW), October 13, 2022. Another press report refers to the process as “akin to peeling an onion, slowly and deliberately pulling back layers to reach a goal at the center.” (Brad Lendon, “China Is Relentlessly Trying to Peel away Japan’s Resolve on Disputed Islands,” CNN, July 8, 2022.)

31 See, for example, Masaaki Yatsuzuka, “How China’s Maritime Militia Takes Advantage of the Grey Zone,” Strategist, January 16, 2023.

32 See, for example, Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang, “China’s Art of Strategic Incrementalism in the South China Sea,” National Interest, August 8, 2020.

33 See, for example, Alan Dupont, “China’s Maritime Power Trip,” The Australian, May 24, 2014. 34 Jackson Diehl, “China’s ‘Creeping Invasion,” Washington Post, September 14, 2014.

35 The strategy has been called “talk and take” or “take and talk.” See, for example, Anders Corr, “China’s Take-And- Talk Strategy In The South China Sea,” Forbes, March 29, 2017. See also Namrata Goswami, “Can China Be Taken Seriously on its ‘Word’ to Negotiate Disputed Territory?” The Diplomat, August 18, 2017.

36 Dan De Luce, “China Tries to Wear Down Its Neighbors with Pressure Tactics,” NBC News, April 10, 2021. See also Dan Altman, “The Future of Conquest, Fights Over Small Places Could Spark the Next Big War,” Foreign Affairs, September 24, 2021.

[CONTINUED…]

p. 11

Island Building and Base Construction

Perhaps more than any other set of actions, China’s island-building (aka land-reclamation) and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Paracel Islands and Spratly Islands in the SCS have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is rapidly gaining effective control of the SCS. China’s large-scale island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS appear to have begun around December 2013, and were publicly reported starting in May 2014. Awareness of, and concern about, the activities appears to have increased substantially following the posting of a February 2015 article showing a series of “before and after” satellite photographs of islands and reefs being changed by the work.37

China occupies seven sites in the Spratly Islands. It has engaged in island-building and facilities- construction activities at most or all of these sites, and particularly at three of them—Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, and Mischief Reef, all of which now feature lengthy airfields as well as substantial numbers of buildings and other structures.

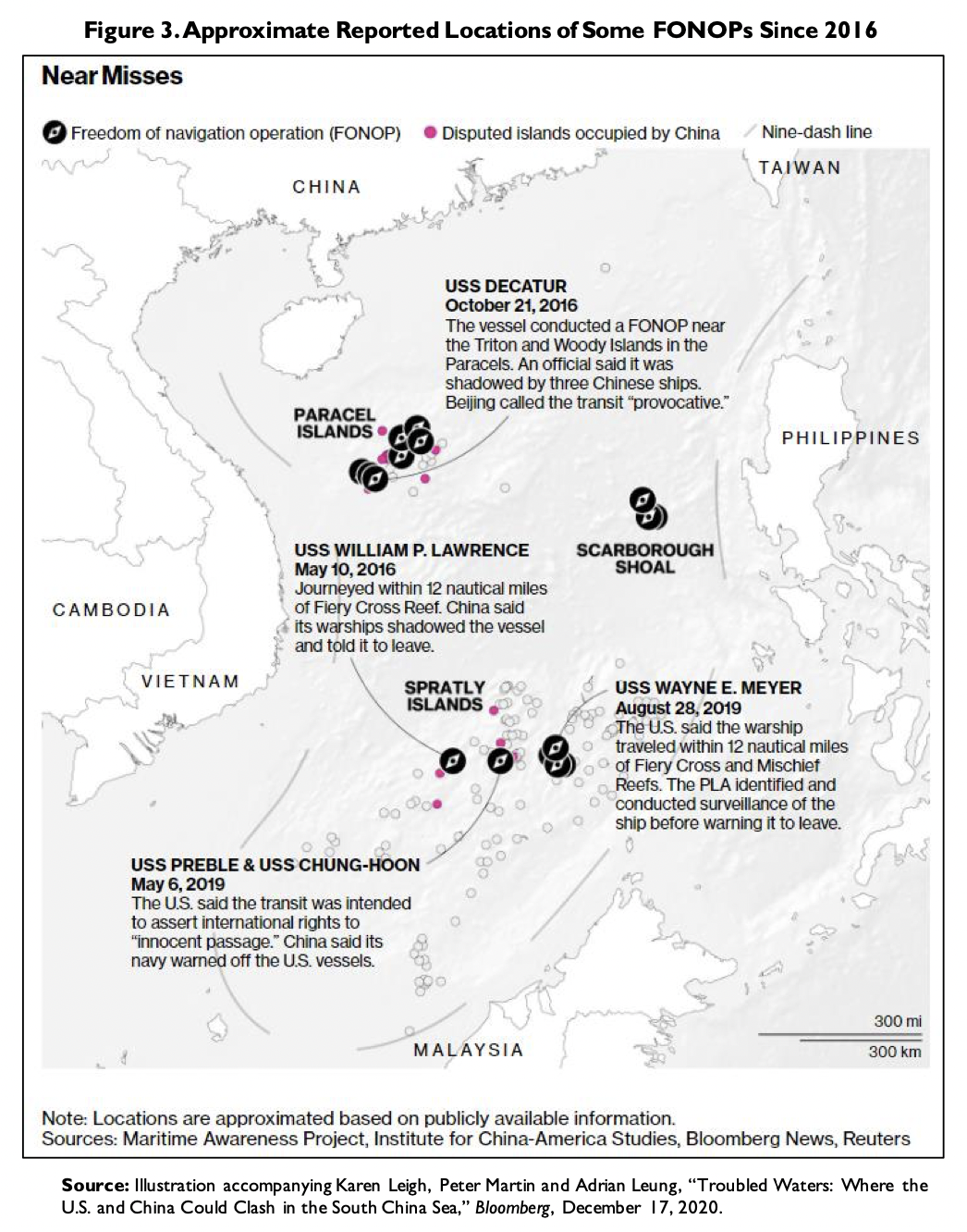

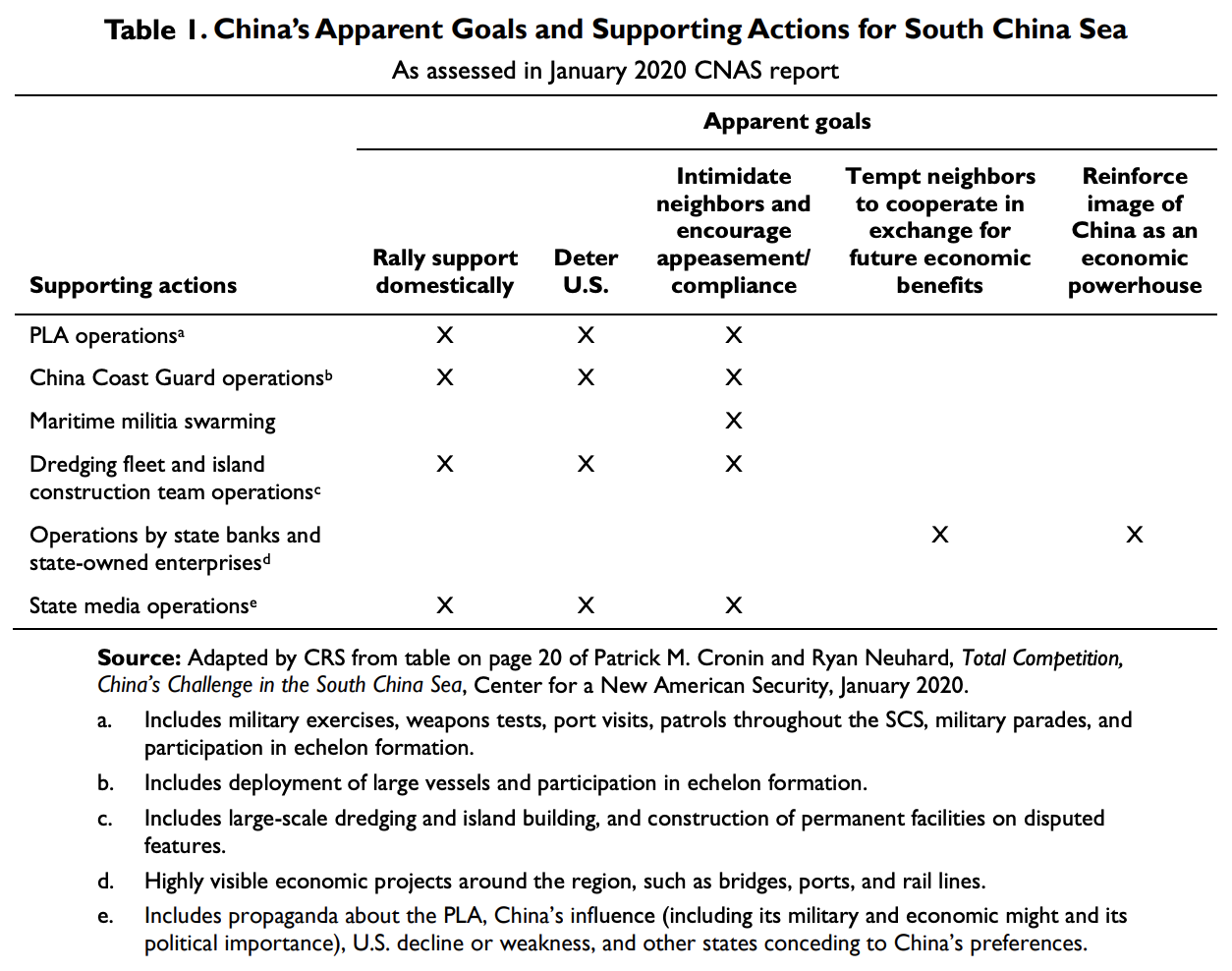

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show reported military facilities at sites that China occupies in the SCS, and reported aircraft, missile, and radar “range rings” extending from those sites. Although other countries, such as Vietnam, have engaged in their own island-building and facilities-construction activities at sites that they occupy in the SCS, these efforts are dwarfed in size by China’s island- building and base-construction activities in the SCS.38

***

37 Mira Rapp-Hooper, “Before and After: The South China Sea Transformed,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), February 18, 2015.

38 See, for example, “Vietnam’s Island Building: Double-Standard or Drop in the Bucket?,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), May 11, 2016. For additional details on China’s island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS, see, in addition to Appendix E, CRS Report R44072, Chinese Land Reclamation in the South China Sea: Implications and Policy Options, by Ben Dolven et al.

p. 12

p. 13

… …

p. 16

USE OF COAST GUARD SHIPS AND MARITIME MILITIA ………………………………………………………………………………………. 16

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

China asserts and defends its maritime claims not only with its navy, but also with its coast guard and its maritime militia. Indeed, China employs its maritime militia and its coast guard more regularly and extensively than its navy in its maritime sovereignty-assertion operations. … …

p. 97

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

Coast Guard Ships

Overview

The China Coast Guard (CCG) is much larger than the coast guard of any other country in the region,218 and it has increased substantially in size through the addition of many newly built ships. China makes regular use of CCG ships to assert and defend its maritime claims, particularly in the ECS, with Chinese navy ships sometimes available over the horizon as backup forces. DOD states that

The CCG is subordinate to the PAP [People’s Armed Police] and is responsible for a wide range of maritime security missions, including defending the PRC’s sovereignty claims; fisheries enforcement; combating smuggling, terrorism, and environmental crimes; as well as supporting international cooperation. In 2021, the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress passed the Coast Guard Law which took effect on 1 February 2021. The legislation regulates the duties of the CCG, to include the use of force, and applies those duties to seas under the jurisdiction of the PRC. The law was meet with concern by other regional countries that may perceive the law as an implicit threat to use force, especially as territorial disputes in the region continue.

The CCG’s rapid expansion and modernization has made it the largest maritime law enforcement fleet in the world. Its newer vessels are larger and more capable than [its] older vessels, allowing them to operate further off shore and remain on station longer. A 2019 academic study published by the U.S. Naval War College estimates the CCG has over 140 regional and oceangoing patrol vessels (or more than 1,000 tons displacement). Some of the vessels are former PLAN [PLA Navy] vessels, such as corvettes, transferred to the CCG and modified CCG operations. The newer, larger vessels are equipped with helicopter facilities, high-capacity water cannons, interceptor boats, and guns ranging from 20 to 76 millimeters. In addition, the same academic study indicates the CCG operates more than 120 regional patrol combatants (500 to 999 tons), which can be used for limited offshore operations, and an additional 450 coast patrol craft (100 to 499 tons).219

***

217 Philip Heijmans, “China Accused of Fresh Territorial Grab in South China Sea,” Bloomberg, December 20, 2022. See also Dan Parsons and Tyler Rogoway, “China’s Man-Made South China Sea Islands Like You’ve Never Seen Them Before,” The Drive, October 27, 2022.

218 For a comparison of the CCG to other coast guards in the region in terms of cumulative fleet tonnage in 2010 and 2016, see the graphic entitled “Total Coast Guard Tonnage of Selected Countries” in China Power Team, “Are Maritime Law Enforcement Forces Destabilizing Asia?” China Power (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), updated August 26, 2020, accessed February 7, 2023, at https://chinapower.csis.org/maritime-forces- destabilizing-asia/.

219 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s [CONTINUED…]

p. 98

In March 2018, China announced that control of the CCG would be transferred from the civilian State Oceanic Administration to the Central Military Commission.220 The transfer occurred on July 1, 2018.221

A January 30, 2023, blog post stated

China’s coast guard presence in the South China Sea is more robust than ever. An analysis of automatic identification system (AIS) [i.e., ship transponder] data from commercial provider MarineTraffic shows that the China Coast Guard (CCG) maintained near-daily patrols at key features across the South China Sea in 2022. Together with the ubiquitous presence of its maritime militia, China’s constant coast guard patrols show Beijing’s determination to assert control over the vast maritime zone within its claimed nine-dash line….

AMTI analyzed AIS data from the year 2022 across the five features most frequented by Chinese patrols: Second Thomas Shoal, Luconia Shoals, Scarborough Shoal, Vanguard Bank, and Thitu Island. Comparison with data from 2020 shows that the number of calendar days that a CCG vessel patrolled near these features increased across the board….

The incomplete nature of AIS data means that these numbers are likely even higher. Some CCG vessels are not observable on commercial AIS platforms, either because their AIS transceivers are disabled or are not detectable by satellite AIS receivers. In other cases, CCG vessels have been observed broadcasting incomplete or erroneous AIS information….

The behavior of CCG vessels observed on patrol in 2022 was similar to that of years past. But AIS data tells only part of the story of the CCG’s influence in the Spratly Islands and its friction with Southeast Asian law enforcement, which took new forms in 2022. Oil and gas standoffs, a recurring feature of the last three years prior, were not as prominent in 2022, likely due to the success of the previous CCG harassment….

As Southeast Asian claimants continue to operate in the Spratly Islands in 2023, the constant presence of China’s coast guard and maritime militia makes future confrontations all but inevitable.222

Law Passed by China on January 22, 2021

A January 22, 2021, press report stated

China passed a law on Friday [January 22] that for the first time explicitly allows its coast guard to fire on foreign vessels, a move that could make the contested waters around China more choppy….

China’s top legislative body, the National People’s Congress standing committee, passed the Coast Guard Law on Friday, according to state media reports.

According to draft wording in the bill published earlier, the coast guard is allowed to use “all necessary means” to stop or prevent threats from foreign vessels.

***

Republic of China 2022, p. 78.

220 See, for example, David Tweed, “China’s Military Handed Control of the Country’s Coast Guard,” Bloomberg,

March 26, 2018.

221 See, for example, Global Times, “China’s Military to Lead Coast Guard to Better Defend Sovereignty,” People’s Daily Online, June 25, 2018. See also Economist, “A New Law Would Unshackle China’s Coastguard, Far from Its Coast,” Economist, December 5, 2020; Katsuya Yamamoto, “The China Coast Guard as a Part of the China Communist Party’s Armed Forces,” Sasakawa Peace Foundation, December 10, 2020.

222 “Flooding the Zone: China Coast Guard Patrols in 2022,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), January 30, 2023.

p. 99

The bill specifies the circumstances under which different kind of weapons—hand-held, ship borne or airborne—can be used.

The bill allows coast guard personnel to demolish other countries’ structures built on Chinese-claimed reefs and to board and inspect foreign vessels in waters claimed by China.

The bill also empowers the coastguard to create temporary exclusion zones “as needed” to stop other vessels and personnel from entering.

Responding to concerns, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said on Friday that the law is in line with international practices.223

On February 19, 2021, the State Department stated that

the United States joins the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan, and other countries in expressing concern with China’s recently enacted Coast Guard law, which may escalate ongoing territorial and maritime disputes.

We are specifically concerned by language in the law that expressly ties the potential use of force, including armed force by the China Coast Guard, to the enforcement of China’s claims in ongoing territorial and maritime disputes in the East and South China Seas.

Language in that law, including text allowing the coast guard to destroy other countries’ economic structures and to use force in defending China’s maritime claims in disputed areas, strongly implies this law could be used to intimidate the PRC’s maritime neighbors.

We remind the PRC and all whose force operates—whose forces operate in the South China Sea that responsible maritime forces act with professionalism and restraint in the exercise of their authorities.

We are further concerned that China may invoke this new law to assert its unlawful maritime claims in the South China Sea, which were thoroughly repudiated by the 2016 Arbitral Tribal[1] ruling. In this regard, the United States reaffirms its statement of July 13th, 2020 regarding maritime claims in the South China Sea.

The United States reminds China of its obligations under the United Nations Charter to refrain from the threat or use of force, and to conform its maritime claims to the

***

223 Yew Lun Tian, “China Authorises Coast Guard to Fire on Foreign Vessels if Needed,” Reuters, January 22, 2021. See also Wataru Okada, “China’s Coast Guard Law Challenges Rule-Based Order,” Diplomat, May 28, 2021; Nguyen Thanh Trung, “How China’s Coast Guard Law Has Changed the Regional Security Structure,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), April 12, 2021; Kawashima Shin, “China’s Worrying New Coast Guard Law, Japan Is Watching the Senkaku Islands Closely,” Diplomat, March 17, 2021;Editorial Board, “China’s New Coast Guard Law Appears Designed to Intimidate,” Japan Times, March 4, 2021; Ryan D. Martinson, “The Real Risks of China’s New Coastguard Law, The Use-of-Force Provisions Are Just the Beginning,” National Interest, March 3, 2021; Sumathy Permal, “Beijing Bolsters the Role of the China Coast Guard,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), March 1, 2021; Katsuya Yamamoto, “Concerns about the China Coast Guard Law—the CCG and the People’s Armed Police,” Sasakawa Peace Foundation, February 25, 2021; Asahi Shimbun, “New Chinese Law Raises Pressure on Japan around Senkaku Islands,” Asahi Shimbun, February 24, 2021; Ryan D. Martinson, “Gauging the Real Risks of China’s New Coastguard Law,” Strategist, February 23, 2021; Eli Huang, “New Law Expands Chinese Coastguard’s Jurisdiction to at Least the First Island Chain,” Strategist, February 16, 2021; Shigeki Sakamoto, “China’s New Coast Guard Law and Implications for Maritime Security in the East and South China Seas,” Lawfare, February 16, 2021; Expert Voices,“Voices: The Chinese Maritime Police Law,” Maritime Awareness Project, February 11, 2021 (includes portions with subsequent dates); Seth Robson, “China Gets More Aggressive with Its Sea Territory Claims as World Battles Coronavirus,” Stars and Stripes, February 1, 2021; Shuxian Luo, “China’s Coast Guard Law: Destabilizing or Reassuring?” Diplomat, January 29, 2021; Shigeki Sakamoto, “China’s New Coast Guard Law and Implications for Maritime Security in the East and South China Seas,” Lawfare, February 16, 2021; Michael Shoebridge, “Xi Licenses Chinese Coastguard to be ‘Wolf Warriors’ at Sea,” Strategist, February 15, 2021; “New Law Institutionalises Chinese Maritime Coercion,” Oxford Analytica Daily Brief, February 15, 2021.

p. 100

International Law of the Sea, as reflected in the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention. We stand firm in our respective alliance commitments to Japan and the Philippines.224

On March 16, 2021, following a U.S.-Japan “2+2” ministerial meeting that day in Tokyo between Secretary of State Blinken, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi, and Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi, the U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee released a U.S.-Japan joint statement for the press that stated in part that the minister “expressed serious concerns about recent disruptive developments in the region, such as the China Coast Guard law.225

Maritime Militia

China also uses its maritime militia—also referred to as the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM)—to defend its maritime claims. The PAFMM essentially consists of fishing- type vessels with armed crew members. In the view of some observers, the PAFMM—even more than China’s navy or coast guard—is the leading component of China’s maritime forces for asserting its maritime claims, particularly in the SCS. U.S. analysts have paid increasing attention to the role of the PAFMM as a key tool for implementing China’s salami-slicing strategy, and have urged U.S. policymakers to focus on the capabilities and actions of the PAFMM.226 DOD states the following about the PAFMM:

***

224 U.S. Department of State, “Department Press Briefing—February 19, 2021,” Ned Price, Department Spokesperson, Washington, DC, February 19, 2021. During the question-and-answer portion of the briefing, the following exchange occurred:

QUESTION: I have two quick questions about the Chinese coast guard law. Have you raised concern directly with Beijing? And secondly, has the U.S. seen any examples of concerning behavior since the law was passed in either the South China Sea or the East China Sea?

MR PRICE: For that, I think, Demetri, we would want to—we might want to refer you to DOD for instances of concerning behavior—for concerning behavior there. When it comes to the coast guard law, of course, we have been in close contact with our allies and partners, and we mentioned a few of them in this context: the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan, and other countries that face the type of unacceptable PRC pressure in the South China Sea. I wouldn’t want to characterize any conversations with Beijing on this. Of course, we have emphasized that, especially at the outset of this administration, our—the first and foremost on our agenda is that coordination among our partners and allies, and we have certainly been engaged deeply in that.

See also Demetri Sevastopulo, Kathrin Hille, and Robin Harding, “US Concerned at Chinese Law Allowing Coast Guard Use of Arms,” Financial Times, February 19, 2021; Simon Lewis, Humeyra Pamuk, Daphne Psaledakis, and David Brunnstrom, “U.S. Concerned China’s New Coast Guard Law Could Escalate Maritime Disputes,” Reuters, February 19, 2021.

225 Department of State, “U.S.-Japan Joint Press Statement,” Media Note, Office of the Spokesperson, March 16, 2021. See also Ralph Jennings, “Maritime Law Expected to Give Beijing an Edge in South China Sea Legal Disputes,” VOA, March 15, 2021; Junko Horiuchi, “Japan, U.S. Express ‘Serious Concerns’ over China Coast Guard Law,” Kyodo News, March 16, 2021.

226 For additional discussions of the PAFMM, see, for example, “The Ebb and Flow of Beijing’s South China Sea Militia,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), November 9, 2022; Samuel Cranny-Evans, “Analysis: How China’s Coastguard and Maritime Militia May Create Asymmetry at Sea,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, July 13, 2022; Zachary Haver, “Unmasking China’s Maritime Militia,” BenarNews, May 17, 2021; Ryan D. Martinson, “Xi Likes Big Boats (Coming Soon to a Reef Near You),” War on the Rocks, April 28, 2021; Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Records Expose China’s Maritime Militia at Whitsun Reef, Beijing Claims They Are Fishing Vessels. The Data Shows Otherwise,” Foreign Policy, March 29, 2021; Zachary Haver, “China’s Civilian Fishing Fleets Are Still Weapons of Territorial Control,” Center for Advanced China Research, March 26, 2021; Chung Li-hua and Jake Chung, “Chinese Coast Guard an Auxiliary Navy: Researcher,” Taipei Times, June 29, 2020; Gregory Poling, “China’s Hidden Navy,” Foreign Policy, June 25, 2019; Mike Yeo, “Testing the Waters: China’s Maritime Militia Challenges Foreign Forces at Sea,” Defense News, May 31, [CONTINUED…]

p. 101

Background & Missions. The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) is a subset of China’s national militia, an armed reserve force of civilians available for mobilization that is ultimately subordinate to the Central Military Commission through the National Defense Mobilization Department. Throughout China, militia units organize around towns, villages, urban sub-districts, and enterprises, and vary widely in composition and mission.

PAFMM vessels train with and assist the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and the China Coast Guard (CCG) in tasks such as safeguarding maritime claims, surveillance and reconnaissance, fisheries protection, logistics support, and search and rescue. China employs the PAFMM in gray zone operations, or “low-intensity maritime rights protection struggles,” at a level designed to frustrate effective response by the other parties involved. China employs PAFMM vessels to advance its disputed sovereignty claims, often amassing them in disputed areas throughout the South and East China Seas. In this manner, the PAFMM plays a major role in coercive activities to achieve China’s political goals without fighting, and these operations are part of broader Chinese military theory that sees confrontational operations short of war as an effective means of accomplishing strategic objectives.

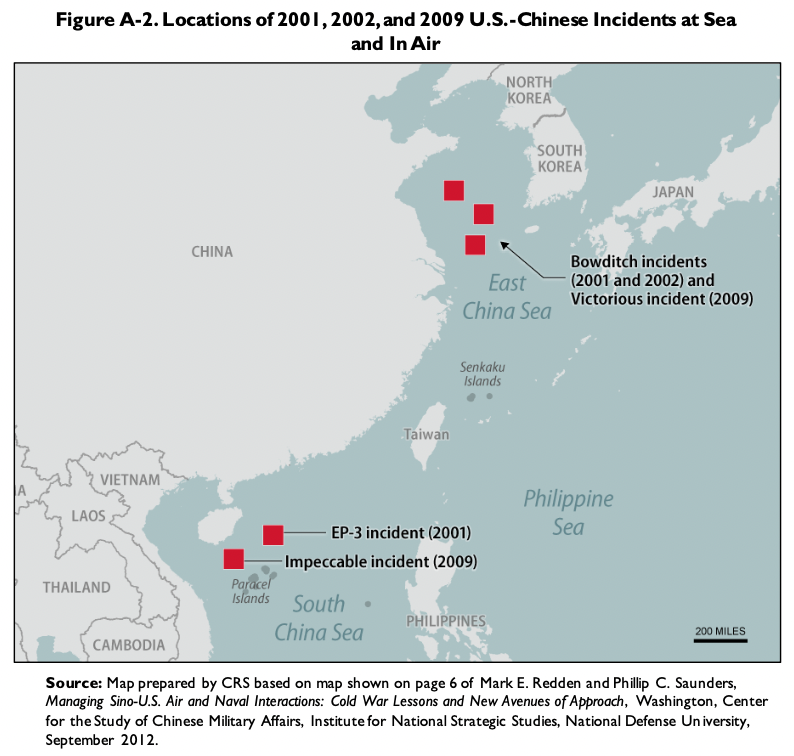

Operations. PAFMM units have been active for decades in maritime incidents and combat operations throughout China’s near seas and in these incidents PAFMM vessels are often used to supplement CCG cutters at the forefront of the incident, giving the Chinese the capacity to outweigh and outlast rival claimants. In March of 2021, hundreds of Chinese militia vessels moored in Whitsun Reef, raising concerns the Chinese planned to seize another disputed feature in the Spratly Islands. Other notable incidents include standoffs with the Malaysian drill ship West Capella (2020), defense of China’s HYSY-981 oil rig in waters disputed with Vietnam (2014), occupation of Scarborough Shoal (2012), and harassment of USNS Impeccable and Howard O. Lorenzen (2009 and 2014). Historically the maritime militia also participated in China’s offshore island campaigns in the 1950s, the 1974 seizure of the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam, and the occupation of Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands in 1994.

The PAFMM also protects and facilitates PRC fishing vessels operating in disputed waters. For example, from late December 2019 to mid-January 2020, a large fleet of over 50 PRC fishing vessels operated under the escort of multiple China Coast Guard patrol ships in

***

2019; Laura Zhou, “Beijing’s Blurred Lines between Military and Non-Military Shipping in South China Sea Could Raise Risk of Flashpoint,” South China Morning Post, May 5, 2019; Andrew S. Erickson, “Fact Sheet: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM),” April 29, 2019, Andrewerickson.com; Jonathan Manthorpe, “Beijing’s Maritime Militia, the Scourge of South China Sea,” Asia Times, April 27, 2019; Ryan D. Martinson, “Manila’s Images Are Revealing the Secrets of China’s Maritime Militia, Details of the Ships Haunting Disputed Rocks Sshow China’s Plans,” Foreign Policy, April 19, 2021; Brad Lendon, “Beijing Has a Navy It Doesn’t Even Admit Exists, Experts Say. And It’s Swarming Parts of the South China Sea,” CNN, April 13, 2021; Samir Puri and Greg Austin, “What the Whitsun Reef Incident Tells Us About China’s Future Operations at Sea,” International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), April 9, 2021; Drake Long, “Chinese Maritime Militia on the Move in Disputed Spratly Islands,” Radio Free Asia, March 24, 2021; Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Secretive Maritime Militia May Be Gathering at Whitsun Reef, Boats Designed to Overwhelm Civilian Foes Can Be Turned into Shields in Real Conflict,” Foreign Policy, March 22, 2021; Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), March 11, 2019; Jamie Seidel, “China’s Latest Island Grab: Fishing ‘Militia’ Makes Move on Sandbars around Philippines’ Thitu Island,” News.com.au, March 5, 2019; Gregory Poling, “Illuminating the South China Sea’s Dark Fishing Fleets,” Stephenson Ocean Security Project (Center for Strategic and International Studies), January 9, 2019; Andrew S. Erickson, “Shining a Spotlight: Revealing China’s Maritime Militia to Deter its Use,” National Interest, November 25, 2018; Todd Crowell and Andrew Salmon, “Chinese Fisherman Wage Hybrid ‘People’s War’ on Asian Seas,” Asia Times, September 6, 2018; Andrew S. Erickson, “Exposed: Pentagon Report Spotlights China’s Maritime Militia,” National Interest, August 20, 2018; Jonathan Odom, “China’s Maritime Militia,” Straits Times, June 16, 2018; Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA, China Maritime Report No. 1, Naval War College, China Maritime Studies Institute, Newport, RI, March 2017, 22 pp. [CONTINUED…]

p. 102

Indonesian claimed waters northeast of the Natuna Islands. At least a portion of the PRC ships in this fishing fleet were affiliated with known traditional maritime militia units, including a maritime militia unit based out of Beihai City in Guangxi province. While most traditional maritime militia units operating in the South China Sea continue to originate from townships and ports on Hainan Island, Beihai is one of a number of increasingly prominent maritime militia units based out of provinces in the PRC. These mainland based maritime militia units routinely operate in the Spratly Islands and in the southern South China Sea, and their operations in these areas are enabled by increased funding from the PRC government to improve their maritime capabilities and grow their ranks of personnel.

Capabilities. Through the National Defense Mobilization Department, Beijing subsidizes various local and provincial commercial organizations to operate PAFMM vessels to perform “official” missions on an ad hoc basis outside of their regular civilian commercial activities. PAFMM units employ marine industry workers, usually fishermen, as a supplement to the PLAN and the CCG. While retaining their day jobs, these mariners are organized and trained, often by the PLAN and the CCG, and can be activated on demand. Additionally, starting in 2015, the Sansha City Maritime Militia in the Paracel Islands has developed into a salaried full-time maritime militia force equipped with at least 84 purpose- built vessels armed with mast-mounted water cannons for spraying and reinforced steel hulls for ramming along with their own command center in the Paracel Islands. Lacking their normal fishing responsibilities, Sansha City Maritime Militia personnel, many of whom are former PLAN and CCG sailors, train for peacetime and wartime contingencies, often with light arms, and patrol regularly around disputed South China Sea features even during fishing moratoriums. Additionally, since 2014, China has built a new Spratly backbone fleet comprising at least 235 large fishing vessels, many longer than 50 meters and displacing more than 500 tons. These vessels were built under central direction from the Chinese government to operate in disputed areas south of twelve degrees latitude that China typically refers to as the “Spratly Waters,” including the Spratly Islands and southern SCS. Spratly backbone vessels were built for prominent PAFMM units in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan Provinces. For vessel owners not already affiliated with PAFMM units, joining the militia was a precondition for receiving government funding to build new Spratly backbone boats. As with the CCG and PLAN, new facilities in the Paracel and Spratly Islands enhance the PAFMM’s ability to sustain operations in the South China Sea.227 … …

***

227 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022, pp. 79-80. …

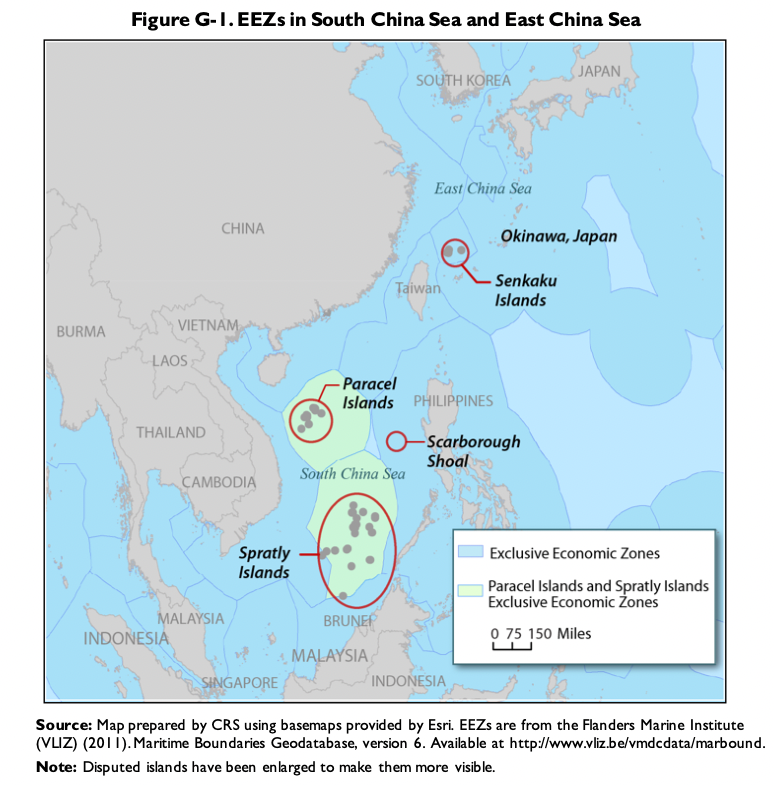

REPORT SUMMARY

In a context of great power competition, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. China’s actions in the SCS—including extensive island- building and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China’s near-seas region—meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea—could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.

Potential broader U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. security relationships with treaty allies and partner states; maintaining a regional balance of power favorable to the United States and its allies and partners; defending the principle of peaceful resolution of disputes and resisting the emergence of an alternative “might-makes-right” approach to international affairs; defending the principle of freedom of the seas, also sometimes called freedom of navigation; preventing China from becoming a regional hegemon in East Asia; and pursing these goals as part of a larger U.S. strategy for competing strategically and managing relations with China.

Potential specific U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: dissuading China from carrying out additional base- construction activities in the SCS, moving additional military personnel, equipment, and supplies to bases at sites that it occupies in the SCS, initiating island-building or base-construction activities at Scarborough Shoal in the SCS, declaring straight baselines around land features it claims in the SCS, or declaring an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the SCS; and encouraging China to reduce or end operations by its maritime forces at the Senkaku Islands in the ECS, halt actions intended to put pressure against Philippine-occupied sites in the Spratly Islands, provide greater access by Philippine fisherman to waters surrounding Scarborough Shoal or in the Spratly Islands, adopt the U.S./Western definition regarding freedom of the seas, and accept and abide by the July 2016 tribunal award in the SCS arbitration case involving the Philippines and China.

The issue for Congress is whether the Administration’s strategy for competing strategically with China in the SCS and ECS is appropriate and correctly resourced, and whether Congress should approve, reject, or modify the strategy, the level of resources for implementing it, or both. Decisions that Congress makes on these issues could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.

AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY—RONALD O’ROURKE

Mr. O’Rourke is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the Johns Hopkins University, from which he received his B.A. in international studies, and a valedictorian graduate of the University’s Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, where he received his M.A. in the same field.

Since 1984, Mr. O’Rourke has worked as a naval analyst for the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress. He has written many reports for Congress on various issues relating to the Navy, the Coast Guard, defense acquisition, China’s naval forces and maritime territorial disputes, the Arctic, the international security environment, and the U.S. role in the world. He regularly briefs Members of Congress and Congressional staffers, and has testified before Congressional committees on many occasions.

In 1996, he received a Distinguished Service Award from the Library of Congress for his service to Congress on naval issues.

In 2010, he was honored under the Great Federal Employees Initiative for his work on naval, strategic, and budgetary issues.

In 2012, he received the CRS Director’s Award for his outstanding contributions in support of the Congress and the mission of CRS.

In 2017, he received the Superior Public Service Award from the Navy for service in a variety of roles at CRS while providing invaluable analysis of tremendous benefit to the Navy for a period spanning decades.

Mr. O’Rourke is the author of several journal articles on naval issues, and is a past winner of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Arleigh Burke essay contest. He has given presentations on naval, Coast Guard, and strategy issues to a variety of U.S. and international audiences in government, industry, and academia.

CLICK BELOW FOR THE FULL TEXT OF SOME OF THE PUBLICATIONS CITED IN O’ROURKE’S CRS REPORT:

Peter A. Dutton and Andrew S. Erickson, “When Eagle Meets Dragon: Managing Risk in Maritime East Asia,” RealClearDefense, 25 March 2015.

Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Records Expose China’s Maritime Militia at Whitsun Reef,” Foreign Policy, 29 March 2021.

Andrew S. Erickson,“Fact Sheet: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM),” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 29 April 2019.

Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Secretive Maritime Militia May Be Gathering at Whitsun Reef,” Foreign Policy, 22 March 2021.

Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 11 March 2019.

Andrew S. Erickson, “Shining a Spotlight: Revealing China’s Maritime Militia to Deter its Use,” The National Interest, 25 November 2018.

Andrew S. Erickson, “Exposed: Pentagon Report Spotlights China’s Maritime Militia,” The National Interest, 20 August 2018.

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA, China Maritime Report 1 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, March 2017).

Andrew S. Erickson and Emily de La Bruyere, “Crashing Its Own Party: China’s Unusual Decision to Spy on Joint Naval Exercises,” China Real Time Report (中国实时报), Wall Street Journal, 19 July 2014.

Andrew S. Erickson and Emily de La Bruyere, “China’s RIMPAC Maritime-Surveillance Gambit,” The National Interest, 29 July 2014.

Andrew S. Erickson, “PRC National Defense Ministry Spokesman Sr. Col. Geng Yansheng Offers China’s Most-Detailed Position to Date on Dongdiao-class Ship’s Intelligence Collection in U.S. EEZ during RIMPAC Exercise,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 1 August 2014.

“Andrew S. Erickson on the ‘Decade of Greatest Danger’,” interviewed by Eyck Freymann, The Wire China, 25 April 2021.