“U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South & East China Seas: Background & Issues for Congress”—Latest Info on PAFMM & CCG from Ron O’Rourke, CRS!

If you have trouble accessing the website above, please download a cached copy here.

You can also click here to access the report via the public CRS website.

KEY EXCERPTS:

p. 10

… …

p. 11

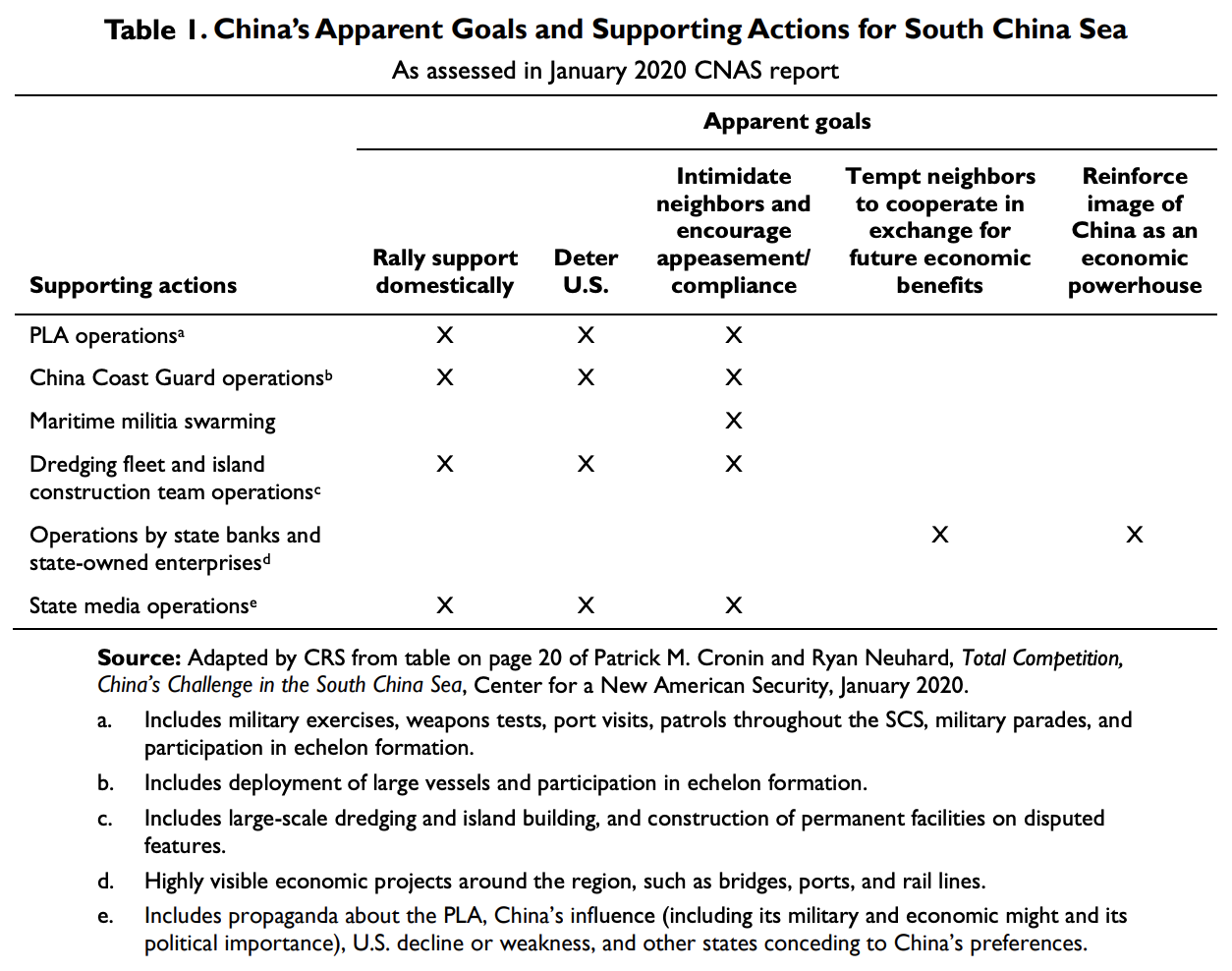

“Salami-Slicing” Strategy and Gray Zone Operations

Observers frequently characterize China’s approach to the SCS and ECS as a gradualist, “salami-slicing” strategy that employs a series of incremental actions, none of which by itself is a casus belli, to gradually change the status quo in China’s favor.34 Other observers have referred to this approach as incrementalism,35 creeping annexation,36 creeping invasion,37 or working to gain ownership through adverse possession,38 or as a “talk and take” strategy, meaning a strategy in which China engages in (or draws out) negotiations while taking gradual actions to gain control of contested areas.39

Observers frequently argue that in support of this gradualist approach, China makes frequent use of gray zone operations, meaning operations that reside in a gray zone between peace and war.40 Gray zone operations can create a conundrum for countries that seek ways to counter them effectively without appearing to employ excessive force or risk escalating the level of violence. Some observers argue that rather than using the term gray zone operations, China’s actions should be referred to as illegal, coercive, aggressive and deceptive (ICAD) operations.41 One U.S. official has characterized China’s actions as amounting to a “boiling frog” strategy.42

***

33 Elisabeth Braw, “Why China Is Stepping Up Its Maritime Attacks on the Philippines,” Foreign Policy, December 13, 2023.

34 See, for example, Julian Ryall, “As Regional Tensions Rise, China Probing Neighbors’ Defense,” Deutsche Welle (DW), October 13, 2022. Another press report refers to the process as “akin to peeling an onion, slowly and deliberately pulling back layers to reach a goal at the center.” (Brad Lendon, “China Is Relentlessly Trying to Peel away Japan’s Resolve on Disputed Islands,” CNN, July 8, 2022.)

35 See, for example, Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang, “China’s Art of Strategic Incrementalism in the South China Sea,” National Interest, August 8, 2020.

36 See, for example, Alan Dupont, “China’s Maritime Power Trip,” The Australian, May 24, 2014.

37 Jackson Diehl, “China’s ‘Creeping Invasion,” Washington Post, September 14, 2014.

38 See Ian Ralby, “China’s Maritime Strategy: To Own the Oceans by Adverse Possession,” The Hill, March 28, 2023.

39 See, for example, Anders Corr, “China’s Take-And-Talk Strategy In The South China Sea,” Forbes, March 29, 2017. See also Namrata Goswami, “Can China Be Taken Seriously on its ‘Word’ to Negotiate Disputed Territory?” The Diplomat, August 18, 2017.

40 See, for example, Masaaki Yatsuzuka, “How China’s Maritime Militia Takes Advantage of the Grey Zone,” Strategist, January 16, 2023. See also Anika Arora Seth, “Weapons of Choice in China’s Territorial Disputes? Axes, Knives, ‘Jostling,’” Washington Post, June 22, 2024.

41 See, for example, David Dizon, “ICAD Tactics: ‘Chinese Plane Dropped 8 Flares on PAF Aircraft’s Flight Path,’” ABS-CBN News, August 12, 2024; Karishma Vaswani, “It Is Time to Give China’s Muscle-Flexing a New Name,” Taipei Times, July 31, 2024 (also published as Karishma Vaswani, “There’s Nothing Gray About China’s Maritime Muscle-Flexing; Illegal, Coercive, Aggressive and Deceptive—Why the ICAD Moniker for Beijing’s Actions in the South China Sea Needs to Be Adopted,” Bloomberg, July 24, 2024); Adam Lockyer, Yves-Heng Lim, and Courtney J. Fung, “Moving Beyond the Grey Zone: The Case for ICAD,” Interpreter, July 17, 2024; Bill Gertz, “China’s Gray-Zone Operations ‘Illegal, Coercive, Aggressive, Deceptive,’ Paparo Says,” Washington Times, May 6, 2024; Ken Moriyasu, “China’s Territorial Claims Illegal, Deceptive: U.S. Indo-Pacific Chief,” Nikkei Asia, May 4, 2024. See also James Holmes, “Is China at War in the South China Sea?” National Interest, June 29, 2024.

42 Matthew Loh, “China Is Gradually Amping up Its Military Aggression in a ‘Boiling Frog’ Strategy, US Indo-Pacific Commander Says,” Business Insider, April 28, 2024; Demetri Sevastopulo, “US Pacific Commander Says China Is Pursuing ‘Boiling Frog’ Strategy,” Financial Times, April 28, 2024.

p. 12

An April 10, 2021, press report states

China is trying to wear down its neighbors with relentless pressure tactics designed to push its territorial claims, employing military aircraft, militia boats and sand dredgers to dominate access to disputed areas, U.S. government officials and regional experts say.

The confrontations fall short of outright military action without shots being fired, but Beijing’s aggressive moves are gradually altering the status quo, laying the foundation for China to potentially exert control over contested territory across vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean, the officials and experts say….

The Chinese are “trying to grind them down,” said a senior U.S. Defense official….

“Beijing never really presents you with a clear deadline with a reason to use force. You just find yourselves worn down and slowly pushed back,” [Gregory Poling of the Center for Strategic and International Studies] said.43

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

China asserts and defends its maritime claims primarily with its maritime militia and its coast guard rather than its navy, although the navy can serve as an “over-the-horizon” backup force when needed. Operations by the maritime militia are particularly prominent in the SCS. For more on China’s coast guard and maritime militia, see Appendix E. … … …

***

43 Dan De Luce, “China Tries to Wear Down Its Neighbors with Pressure Tactics,” NBC News, April 10, 2021.

p. 14

p. 15

… …

p. 68

Appendix E. China’s Approach to Maritime Disputes in SCS and ECS

This appendix presents additional background information on China’s approach to maritime disputes in the SCS and ECS, and to strengthening its position over time in the SCS.187

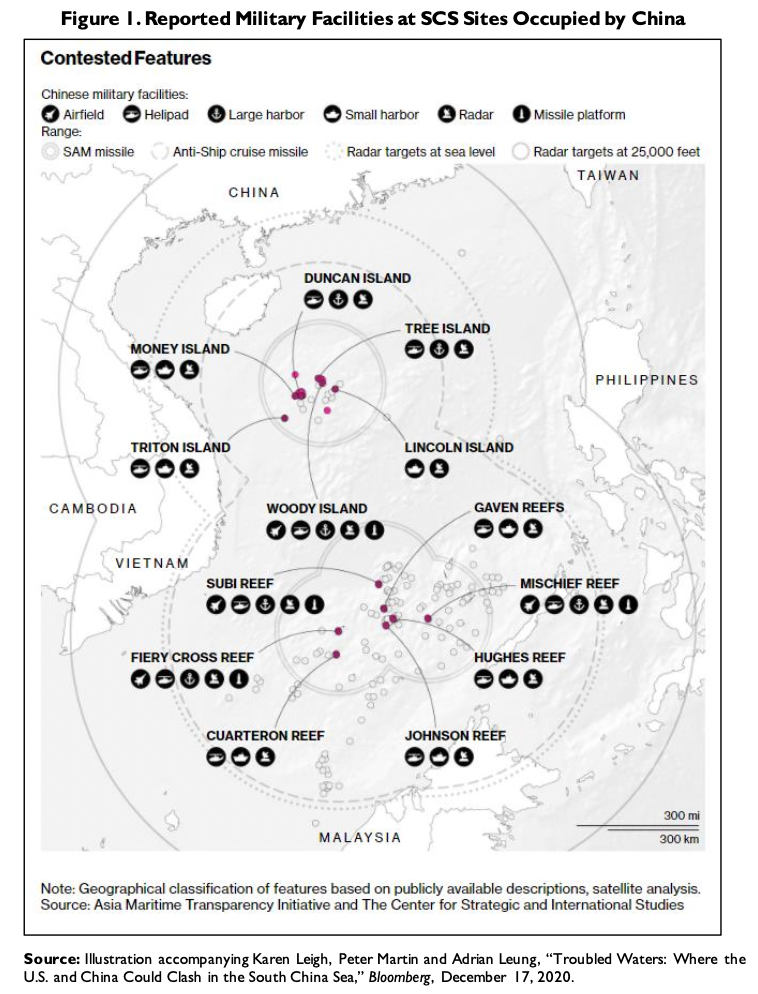

Island Building and Base Construction

DOD stated in 2023 that

Since at least 2014, CMM [China’s Maritime Militia] vessels have engaged in covert small scale reclamation activity and likely caused physical changes observed at multiple unoccupied features in the Spratly Islands, including Lankiam Cay, Eldad Reef, Sandy Cay, and Whitsun Reef. Beijing likely is attempting to covertly alter these features so that it can portray them as naturally formed high tide elevations capable of supporting PRC maritime claims out to the farthest extent of the nine-nash line. In contrast to the PRC large-scale reclamation program, which was overt and where the original status of occupied features is well documented, the less well-known historical record about many of the unoccupied features makes them more susceptible to PRC efforts to shape international opinion regarding the status of the features….

The PRC’s outposts on the Spratly Islands are capable of supporting military operations, including advanced weapon systems, and have supported non-combat aircraft. However, no large-scale presence of combat aircraft has been yet observed at airfields on the outposts….

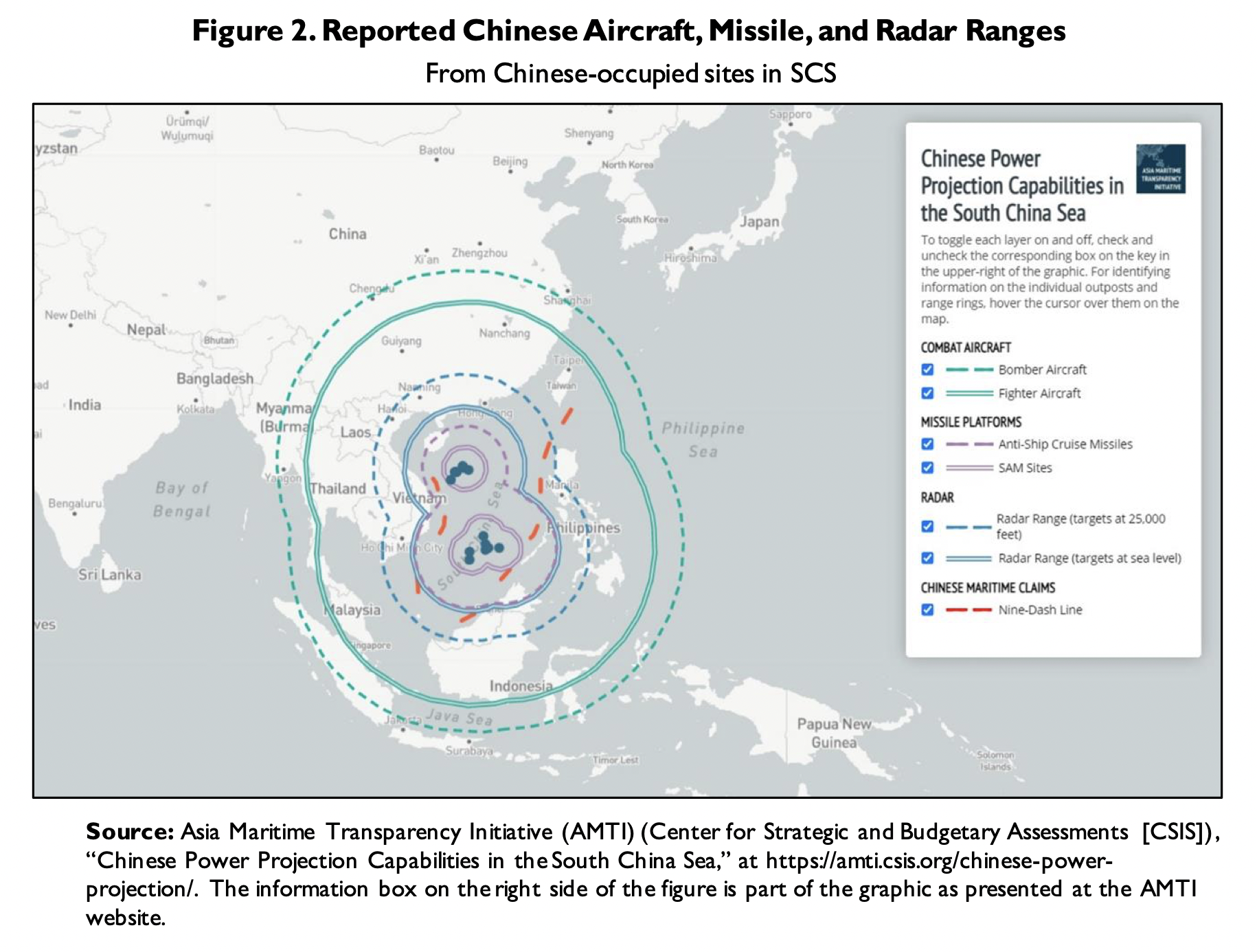

Since early 2018, the PRC-occupied Spratly Islands outposts have been equipped with advanced anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems and military jamming equipment, representing the most capable land-based weapons systems deployed by any claimant in the disputed SCS areas to date. In mid-2021, the PLA deployed an intelligence-gathering ship and a surveillance aircraft to the Spratly Islands during U.S.-Australia bilateral operations in the region. From early 2018 through 2022, the PRC regularly used its Spratly Islands outposts to support naval and coast guard operations in the SCS. The PRC has added more than 3,200 acres of land to the seven features it occupies in the Spratlys. China has also added military infrastructure, including 72 aircraft hangars, docks, satellite communication equipment, antenna array, radars, and hardened shelters for missile platforms.

The PRC has stated these projects are mainly to improve marine research, safety of navigation, and the living and working conditions of personnel stationed on the outposts. However, the outposts provide airfields, berthing areas, and resupply facilities that allow the PRC to maintain a more flexible and persistent military and paramilitary presence in the area. This improves the PRC’s ability to detect and challenge activities by rival claimants or third parties and widens the range of response options available to Beijing.188

A January 25, 2023, press report stated

***

187 For additional discussion, see Andrew Chubb, Dynamics of Assertiveness in the South China Sea: China, the Philippines, and Vietnam, 1970–2015, National Bureau of Asian Research, May 2022, 45 pp.; or Andrew Chubb, “PRC Assertiveness in the South China Sea, Measuring Continuity and Change, 1970–2015, International Security, Winter 2020-2021: 79-121.)

188 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023, released October 19, 2023, pp. 81, 124, 126-127.

p. 69

A newly emerged satellite image shows a Chinese air defense facility on the Paracel Islands, which analysts say indicates the People’s Liberation Army now has surface-to-air missiles at the ready permanently in both the contested archipelagos in the South China Sea….

A satellite image of what appears to be a newly-built but completed missile battalion on Woody Island within the Paracel group has surfaced this week on Twitter.

The image—credited to Maxar Technologies, a space technology firm, and allegedly taken last April—shows four buildings with retractable roofs at a site on Woody (Yongxing in Chinese), the largest of the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea.

One of the buildings has its roof partially open, showing what appears to be surface-to-air missiles (SAM) launchers inside.

ImageSat International, a space intelligence company, first detected the appearance, removal and reappearance of HQ-9 SAM launchers on Woody Island in 2016.

But the new satellite image, which RFA could not verify independently, shows that the PLA has completed building an air defense base resembling those on the three artificial islands that it has fully militarized.

Similar structures with retractable roofs were detected on Subi, Mischief and Fiery Cross reefs, part of the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, Tom Shugart, adjunct Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security, wrote on Twitter.

They are permanent facilities that can house long-range missile batteries that would expand China’s reach in disputed areas.189

A December 20, 2022, press report stated

China is building up several unoccupied land features in the South China Sea, according to Western officials, an unprecedented move they said was part of Beijing’s long-running effort to strengthen claims to disputed territory in a region critical to global trade.

While China has previously built out disputed reefs, islands and land formations in the area that it had long controlled—and militarized them with ports, runways and other infrastructure—the officials presented images of what they called the first known instances of a nation doing so on territory it doesn’t already occupy. They warned that Beijing’s latest construction activity indicates an attempt to advance a new status quo, even though it’s too early to know whether China would seek to militarize them….

The officials said new land formations have appeared above water over the past year at Eldad Reef in the northern Spratlys, with images showing large holes, debris piles and excavator tracks at a site that used to be only partially exposed at high tide. A 2014 photo of the reef, previously reported to have been taken by the Philippine military, had depicted what the officials said was a Chinese maritime vessel offloading an amphibious hydraulic excavator used in land reclamation projects.

They said similar activities have also taken place at Lankiam Cay, known as Panata Island in the Philippines, where a feature had been reinforced with a new perimeter wall over the course of just a couple of months last year. Other images they presented showed physical changes at both Whitsun Reef and Sandy Cay, where previously submerged features now sit permanently above the high-tide line.190

***

189 RFA [Radio Free Asia] Staff, “China Puts Missile Bases on Disputed South China Sea Islands, Analysts Say,” Radio Free Asia, January 25, 2023.

190 Philip Heijmans, “China Accused of Fresh Territorial Grab in South China Sea,” Bloomberg, December 20, 2022. See also Dan Parsons and Tyler Rogoway, “China’s Man-Made South China Sea Islands Like You’ve Never Seen Them Before,” The Drive, October 27, 2022.

p. 70

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia Coast Guard Ships

Overview

For additional discussion of China’s island-building and facility-construction activities, see CRS Report R44072, Chinese Land Reclamation in the South China Sea: Implications and Policy Options, by Ben Dolven et al.

The China Coast Guard (CCG) is much larger than the coast guard of any other country in the region,191 and it has increased substantially in size through the addition of many newly built ships. China makes regular use of CCG ships to assert and defend its maritime claims, particularly in the ECS, with PRC navy ships sometimes available over the horizon as backup forces. DOD states that

The CCG is subordinate to the PAP and is responsible for a wide range of maritime security missions, including defending the PRC’s sovereignty claims; combating smuggling, terrorism, and environmental crimes; as well as supporting international cooperation. In 2021, the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress passed the Coast Guard Law which took effect on 1 February 2021. The legislation regulates the duties of the CCG, to include the use of force, and applies those duties to seas under the jurisdiction of the PRC. The law was met with concern by other regional countries that may perceive the law as an implicit threat to use force, especially as territorial disputes in the region continue.

Since the law, CCG activity has continued to prompt regional concern. In March 2022, the Philippines lodged a diplomatic protest against the PRC after a CCG vessel reportedly engaged in “close distance maneuvering” near a Filipino vessel in the disputed Scarborough Shoal. In December 2022, Japan reported that CCG vessels stayed in its territorial waters for over 72 hours, the longest continuous intrusion since 2012.

The CCG’s continued expansion and modernization makes it the largest maritime law enforcement fleet in the world. Newer CCG vessels are larger and more capable than older vessels, allowing them to operate further offshore and remain on station longer. While exact numbers are unavailable, open-source reporting and commercial imagery counts indicate the CCG has over 150 regional and oceangoing patrol vessels (more than 1,000 tons). These larger vessels include over 20 corvettes transferred from the PLAN, which were modified for CCG operations. The newer, larger CCG vessels are equipped with helicopter facilities, high-capacity water cannons, multiple interceptor boats and guns ranging from 20 to 76 millimeters. Revised estimates indicate the CCG operates more than 50 regional patrol combatants (more than 500 tons), which can be used for limited offshore operations, and an additional 300 coastal patrol craft (100 to 499 tons).192

***

191 See, for example, Damien Cave, “China Creates a Coast Guard Like No Other, Seeking Supremacy in Asian Seas,” New York Times, June 12 (updated September 24), 2023.

192 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023, released October 19, 2023, pp. 79-80. See also Alyssa Chen, “China Coast Guard: What Does It Do and How Did It Become So Powerful?” South China Morning Post, July 1, 2024; Karishma Vaswani, “China’s Coast Guard Is Its Secret Weapon Against Taiwan,” Bloomberg, June 11, 2024; “Control by Patrol: The China Coast Guard in 2023,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), March 29, 2024; Yukio Tajima, “China Flexes Maritime Muscle with Bigger, Tougher Coast Guard Ships,” Nikkei Asia, February 28, 2024.

p. 71

Maritime Militia

China also uses its maritime militia—also referred to as China’s Maritime Militia (CMM) or the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM)—to defend its maritime claims. The CMM/PAFMM essentially consists of fishing-type vessels with armed crew members. In the view of some observers, the CMM/PAFMM—even more than China’s navy or coast guard—is the leading component of China’s maritime forces for asserting its maritime claims, particularly in the SCS. U.S. policymakers and analysts have paid increasing attention to the role of the CMM/PAFMM as a key tool for implementing China’s salami-slicing strategy.193 DOD states the following about the PAFMM:

***

193 See, for example, the following items, which are grouped by year of publication:

Items published in 2024: Helen Davidson, “China’s Maritime Militia: The Shadowy Armada Whose Existence Beijing Rarely Acknowledges,” Guardian, June 12, 2024; Philip Heijmans, “China Militia Presence Increases in South China Sea, Report Says,” Bloomberg, February 28, 2024 (reporting on the following item); “Wherever They May Roam: China’s [maritime] Militia in 2023,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), February 28, 2024.

Items published in 2023: Agnes Chang and Hannah Beech, “Fleets of Force, How China Strong-Armed Its Way Into Dominating the South China Sea,” New York Times, November 16, 2023; Brad Lendon, “‘Little Blue Men’: Is a Militia Beijing Says Doesn’t Exist Causing Trouble in the South China Sea?” CNN, August 12, 2023.

Items published in 2022: “The Ebb and Flow of Beijing’s South China Sea Militia,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), November 9, 2022; Samuel Cranny-Evans, “Analysis: How China’s Coastguard and Maritime Militia May Create Asymmetry at Sea,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, July 13, 2022.

Items published in 2021: Zachary Haver, “Unmasking China’s Maritime Militia,” BenarNews, May 17, 2021; Ryan D. Martinson, “Xi Likes Big Boats (Coming Soon to a Reef Near You),” War on the Rocks, April 28, 2021; Ryan D. Martinson, “Manila’s Images Are Revealing the Secrets of China’s Maritime Militia, Details of the Ships Haunting Disputed Rocks Sshow China’s Plans,” Foreign Policy, April 19, 2021; Brad Lendon, “Beijing Has a Navy It Doesn’t Even Admit Exists, Experts Say. And It’s Swarming Parts of the South China Sea,” CNN, April 13, 2021; Samir Puri and Greg Austin, “What the Whitsun Reef Incident Tells Us About China’s Future Operations at Sea,” International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), April 9, 2021; Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Records Expose China’s Maritime Militia at Whitsun Reef, Beijing Claims They Are Fishing Vessels. The Data Shows Otherwise,” Foreign Policy, March 29, 2021; Zachary Haver, “China’s Civilian Fishing Fleets Are Still Weapons of Territorial Control,” Center for Advanced China Research, March 26, 2021; Drake Long, “Chinese Maritime Militia on the Move in Disputed Spratly Islands,” Radio Free Asia, March 24, 2021; Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Secretive Maritime Militia May Be Gathering at Whitsun Reef, Boats Designed to Overwhelm Civilian Foes Can Be Turned into Shields in Real Conflict,” Foreign Policy, March 22, 2021.

Items published in 2019: Gregory Poling, “China’s Hidden Navy,” Foreign Policy, June 25, 2019; Mike Yeo, “Testing the Waters: China’s Maritime Militia Challenges Foreign Forces at Sea,” Defense News, May 31, 2019; Laura Zhou, “Beijing’s Blurred Lines between Military and Non-Military Shipping in South China Sea Could Raise Risk of Flashpoint,” South China Morning Post, May 5, 2019; Andrew S. Erickson, “Fact Sheet: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM),” April 29, 2019, Andrewerickson.com; Jonathan Manthorpe, “Beijing’s Maritime Militia, the Scourge of South China Sea,” Asia Times, April 27, 2019; Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), March 11, 2019; Jamie Seidel, “China’s Latest Island Grab: Fishing ‘Militia’ Makes Move on Sandbars around Philippines’ Thitu Island,” News.com.au, March 5, 2019; Gregory Poling, “Illuminating the South China Sea’s Dark Fishing Fleets,” Stephenson Ocean Security Project (Center for Strategic and International Studies), January 9, 2019.

Items published in 2018: Andrew S. Erickson, “Shining a Spotlight: Revealing China’s Maritime Militia to Deter its Use,” National Interest, November 25, 2018; Todd Crowell and Andrew Salmon, “Chinese Fisherman Wage Hybrid ‘People’s War’ on Asian Seas,” Asia Times, September 6, 2018; Andrew S. Erickson, “Exposed: Pentagon Report Spotlights China’s Maritime Militia,” National Interest, August 20, 2018; Jonathan Odom, “China’s Maritime Militia,” Straits Times, June 16, 2018.

Item published in 2017: Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA, China Maritime Report No. 1, Naval War College, China Maritime Studies Institute, Newport, RI, March 2017, 22 pp.

p. 72

China’s Maritime Militia (CMM) is a subset of the PRC’s national militia, an armed reserve force of civilians available for mobilization that is ultimately subordinate to the CMC through the National Defense Mobilization Department. Throughout China, militia units organize around towns, villages, urban sub-districts, and enterprises and vary widely in composition and mission.

CMM vessels train with and assist the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and the China Coast Guard (CCG) in tasks such as safeguarding maritime claims, surveillance and reconnaissance, fisheries protection, logistics support, and search and rescue. These operations traditionally take place within the FIC along China’s coast and near disputed features in the SCS such as the Second Thomas Shoal, Scarborough Reed, and Luconia Shoal. However, the presence of possible CMM vessels mixed in with Chinese fishing vessels near Indonesia’s Natuna Island outside of the “nine-dashed line” on Chinese maps indicated a possible ambition to expand CMM operations within the region. The PRC employs the CMM in gray zone operations, or “low-intensity maritime rights protection struggles,” at a level designed to frustrate effective response by the other parties involved. The PRC employs CMM vessels to advance its disputed sovereignty claims, often amassing them in disputed areas throughout the SCS and ECS. In this manner, the CMM plays a major role in coercive activities to achieve the PRC’s political goals without fighting and these operations are part of broader Chinese military theory that sees confrontational operations short of war as an effective means of accomplishing strategic objectives.

CMM units have been active for decades in incidents and combat operations throughout China’s near seas and in these incidents CMM vessels are often used to supplement CCG cutters at the forefront of the incident, giving the Chinese the capacity to outweigh and outlast rival claimants. From September 2021 to September 2022, maritime militia vessels were a constant presence near Iroquois Reef in the Spratly Islands within the Philippines EEZ. Other notable examples include standoffs with the Malaysia drill ship West Capella (2020), defense of China’s HYSY-981 drill rig in waters disputed with Vietnam (2014), occupation of Scarborough Reef (2012), and harassment of USNS Impeccable and Howard O. Lorenzen (2009 and 2014). Historically, the maritime militia also participated in China’s offshore island campaigns in the 1950s, the 1974 seizure of the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam, the occupation of Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands in 1994.

The CMM also protects and facilitates Chinese fishing vessels operating in disputed waters. From late December 2019 to mid-January 2020, a large fleet of over 50 Chinese fishing vessels operated under the escort of multiple China Coast Guard patrol ships in Indonesian claimed waters northeast of the Natuna Islands. At least a portion of the Chinese ships in this fishing fleet were affiliated with known traditional maritime militia units, including a maritime militia unit based out of Beihai City in Guangxi province. While most traditional maritime militia units operating in the SCS continue to originate from townships and ports on Hainan Island, Beihai is one of a number of increasingly prominent maritime militia units based out of provinces in mainland China. These mainland based maritime militia units routinely operate in the Spratly Islands and in the southern SCS, and their operations in these areas are enabled by increased funding from the Chinese government to improve their maritime capabilities and grow their ranks of personnel.

[start of text box] CMM AND LAND RECLAMATION IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

Since at least 2014, CMM vessels have engaged in covert small scale reclamation activity and likely caused physical changes observed at multiple unoccupied features in the Spratly Islands, including Lankiam Cay, Eldad Reef, Sandy Cay, and Whitsun Reef. Beijing likely is attempting to covertly alter these features so that it can portray them as naturally formed high tide elevations capable of supporting PRC maritime claims out to the farthest extent of the nine-nash line. In contrast to the PRC large-scale reclamation program, which was overt and where the original status of occupied features is well documented, the less well-

p. 73

known historical record about many of the unoccupied features makes them more susceptible to PRC efforts to shape international opinion regarding the status of the features. [end of text box]

Through the National Defense Mobilization Department, Beijing subsidizes various local and provincial commercial organizations to operate CMM vessels to perform “official” missions on an ad hoc basis outside of their regular civilian commercial activities. CMM units employ marine industry workers, usually fishermen, as a supplement to the PLAN and the CCG. While retaining their day jobs, these mariners are organized and trained, often by the PLAN and the CCG, and can be activated on demand.

Since 2014, China has built a new Spratly backbone fleet comprising at least 235 large steel-hulled fishing vessels, many longer than 50 meters and displacing more than 500 tons. These vessels were built under central direction from the PRC government to operate in disputed areas south of 12 degrees latitude that China typically refers to as the “Spratly Waters,” including the Spratly Islands and southern SCS. Spratly backbone vessels were built for prominent CMM units in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan Provinces. For vessel owners not already affiliated with CMM units, joining the militia was a precondition for receiving government funding to build new Spratly backbone boats. As with the CCG and PLAN, new facilities in the Paracel and Spratly Islands enhance the CMM’s ability to sustain operations in the SCS.

Starting in 2015, the Sansha City Maritime Militia in the Paracel Islands has been developed into a salaried full-time maritime militia force with its own command center and equipped with at least 84 purpose-built vessels armed with mast-mounted water cannons for spraying and reinforced steel hulls for ramming. Freed from their normal fishing responsibilities, Sansha City Maritime Militia personnel—many of whom are former PLAN and CCG sailors—train for peacetime and wartime contingencies, often with light arms, and patrol regularly around disputed South China Sea features even during fishing moratoriums.

The Tanmen Maritime Militia is another prominent CMM unit. Homeported in Tanmen township on Hainan Island, the formation was described by Xi as a “model maritime militia unit” during a visit to Tanmen harbor in 2013. During the visit, Xi encouraged Tanmen to support “island and reef development” in the SCS. Between 1989 and 1995, the Tanmen Maritime Militia, under the authority of the PLAN Southern Theater Navy (then the South Sea Fleet), was involved in the occupation and reclamation of PRC outposts in the Spratly Islands, including Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, and Mischief Reef.194

***

194 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023, released October 19, 2023, pp. 80-82.

p. 83

April 2023 Remarks by Commander, Office of Naval Intelligence

In April 5, 2023, remarks at a conference, Rear Admiral Mike Studeman, Commander, Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) stated the following about the actions of China’s military forces:

Russia is not alone in playing with fire in the international commons and risking serious escalation. Like its close friend, China seems to think it’s also okay to conduct high-risk activities with its frontline forces.

The Chinese have been periodically flying their fighters much closer to U.S. aircraft than ever before. For many years, the Chinese would react to U.S. operations in international airspace, but they would stand-off by a matter of miles on average. However, in the last few years, we’ve experienced over 100 fighter intercepts that have approached within 100 feet of U.S. and allied aircraft, sometimes within 10 to 20 feet of those aircraft. This means that if there’s one single twitch of the stick in the cockpit of those fighters, disaster is just a second away. This photo (referring to supporting graphics) shows how close a PRC J-11 fighter jet flew near the cockpit of a U.S. RC-135, one of our unarmed surveillance aircraft flying in international airspace.

These kinds of dangerous PRC behaviors are not just concentrated against the U.S., but are also directed at our allies. In May 2022, a Chinese J-16 fighter harassed an unarmed Australian P-8 patrol aircraft operating in international airspace in the eastern portion of the South China Sea, far away from China. While crossing in front, without warning the Chinese pilot dispensed clouds of chaff, the thin aluminum strips used to evade a radar-guided missile in combat. The chaff was ingested into the jet engines of the Australian aircraft, endangering the crew, which was lucky to bring back the jet safely.

In the East China Sea, Chinese fighters have also harried Canadian patrol aircraft engaged in patrols in international airspace designed to help enforce U.N. Security Council Resolution sanctions against North Korea. China signed on to those U.N. resolutions, yet still acts in risky, highly assertive ways that hazard air crews. These kinds of interactions are occurring all too frequently, though China will either deny they occur or blame others when they occur.

It’s not just close proximity operations that we worry about. China routinely engages in radio intimidation, giving repeated warnings to ships and aircraft operating in international spaces, threatening consequences. Threatening with language insinuating that China has unilateral control over what the rest of the world recognizes as international air and waterspace.

On the surface of the sea, Chinese Maritime Militia vessels, the China Coast Guard, and the PLA Navy operate in synchronicity to pressure foreign forces inside the so-called “nine-dashed line,” which is China’s massive, illegal, extraterritorial claim to most of the South China Sea. The Militia and Coast Guard have rammed foreign ships, water cannoned other vessels, interfered with legitimate resource exploration activities sponsored by other nations, driven off Southeast Asia nations’ fishermen in their own waters, and engaged in

***

220 See, for example, James R. Holmes, “The Nine-Dashed Line Isn’t China’s Monroe Doctrine,” The Diplomat, June 21, 2014, and James Holmes, “China’s Monroe Doctrine,” The Diplomat, June 22, 2012.

p. 84

many other harassment tactics as they try to enforce their unlawful claims and cow other nations into giving China de facto control of whatever Beijing unilaterally claims in contravention of the U.N. Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS),

When it chooses, China also intentionally violates COLREGs and CUES, two agreements designed for safety at sea. COLREGs are International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, which were published by the International Maritime Organization in 1972. CUES stands for the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea, which has been in existence since 2014. China has signed both, but ignores them at unpredictable times. One example is a PLA LUYANG destroyer dangerously cutting across the bow of a US destroyer in 2018. Another Chinese tactic we’ve seen recently involves a PLA auxiliary putting themselves on a collision course with a foreign vessel, falsely signaling that they’ve lost control of steerage, and claiming “stand-on” rights to force the other ship to give way and change course. These behaviors reflect a brazen disregard for basic safety guidelines and show how flagrantly China flouts international strictures they promised to abide.

The Chinese also menace with military-grade lasers, like the recent case of a Coast Guard ship lasing a Philippine resupply ship making for one of the Philippine’s outposts in the South China Sea. True professionals, the Philippines have recognized the best way to deal with this is not by responding with guns or missiles. The know their best “weapon system” is a video camera to show the world what’s happening and expose China’s pattern of bullying and unsafe behavior. China also directed eye-damaging lasing against an Australian patrol aircraft monitoring a PLA Task Group operating just north of Australia, and in the past has used lasers against U.S. pilots landing in Djibouti.

There are other ways China systematically bends, breaks, or tries to skirt around international norms, conventions, and laws. For ten years, the Chinese have been covertly attempting to build up a number of cays in the Spratly Islands zone. We have seen them try to raise submerged or partly submerged sandbars and reefs to become above-water features by dumping loads of sandbags. Their auxiliaries have been offloading tractors to bulldoze sand around to further enlarge these features.

The Chinese lawfare gambit is to try to use these features as anchor points to claim exclusive economic zones and territorial water rights using a new rationale they concocted called “offshore archipelagos for continental states.” China knows manmade islets don’t qualify for any Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) claims, so they try to build them up secretly and pretend they naturally formed. At the same time, they are desperately trying to reshape the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), or at least alter the way its interpreted, which today clearly defines what is a continental state and what is an archipelagic state. China is definitively, based on many factors under UNCLOS, the former and not the latter. (Fiji, Philippines, Indonesia, however, are examples of nations that are officially able to claim archipelagic status.)

Just like their unlawful claim to own everything inside the “nine-dashed line,” most recently Beijing has illegally claimed jurisdiction over the Taiwan Strait, a highly-trafficked international waterway. More disturbingly, Beijing has started to slowly condition the region to the possibilities of “boarding and inspections” in these international spaces using its Maritime Safety Administration forces. China is likely going to slowly, patiently, lay the groundwork to justify future extraterritorial and extralegal actions in the Taiwan Strait, either directed at Taiwan or any other foreign forces it feels shouldn’t operate there—all of which constitutes a direct threat to a major international sea line of communication.

Not only does the region have to worry about what China’s frontline forces are doing beyond their legitimate borders as they try to control more areas in the First Island China, but many countries have been confronted with even more invasive operations. China’s auxiliaries often operate without permission in other nations’ EEZs doing military and resource surveys. Chinese distant water fishing fleets continue to illegally overexploit and

p. 85

deplete fishing stocks in other nations’ littorals. And Chinese surveillance balloons have recklessly and repeatedly flown through scores of nations’ sovereign airspaces in clear violation of international law.

DOES XI JINPING HAVE CONTROL OVER HIS FRONTLINE FORCES?

All of these activities beg several questions. The first one we need to ask ourselves is whether or not Xi Jinping has lost control of his frontline forces. Are the frontline forces free to do what they like, or are these high-risk tactics deliberated on and approved on high by Xi Jinping?

Well, first, it’s clear that Xi Jinping wants to be in control of everything. In a remarkable bureaucratic feat of maneuvering, Xi has been able to throw out the collective leadership practices that marked the last 50 years of how China made decisions. He has concentrated more power than anyone since Mao. He has successfully placed himself in charge of all major “Leading Groups,” which coordinate everything from national security to domestic policy. Xi also eliminated the power of other networks and factions that had been serving as counterbalancing forces within the Chinese decision-making system. Recall the image of Hu Jintao, the former president, being physically lifted out of his seat, manhandled and escorted out of the last National Party Congress. That was Xi symbolically proclaiming there is no other power except his own in today’s China. So, Xi is clearly in charge, and he’s notoriously architected a chain of command so that all major decisions either flow up or down from him.

Let’s consider a second possibility: Has Xi Jinping unleashed forces that he can’t control? Has he given excess license to his subordinates to take actions at the tactical level, even if they carry potential strategic effects? Do commanders of frontline forces exercise too much freedom of action, because Xi is preoccupied or overburdened?

Indeed, it’s hard to believe that Xi can maintain enough span of control to allow him to have cognizance of everything that his forces are doing. Overconcentration of power at the top naturally creates gaps and seams in governance. It is very possible Xi has been surprised, pretended he wasn’t, and covered down with damage control measures while trying to sustain the image of infallibility of his rule.

A glimmer of insight into this dynamic takes us out to the far west of China, to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with India, where an aggressive Western Military Region commander orchestrated patrols and set up encampments beyond China’s lines in the first of a series of major provocations, violating years of protocols that had kept peace on the LAC. The friction ultimately led to dozens of deaths and bloodletting in Galwan Valley in mid-2020, creating near-war conditions between two nuclear powers and quickly destroying years of hard-earned bilateral trust. In this case study, one has to conclude Xi Jinping is either geopolitically incompetent…or Xi was compelled to provide retrospective support, doubling down on the miscalculation of his generals. To some, it smells a lot like a military region commander became the tail that wagged the Beijing dog.

A third important question: Does Xi Jinping actively encourage assertive, even belligerent execution of his policies because he values loyalty to the China dream above everything else, literally at almost any cost? In the fever to realize China’s rise, is he willing to brook almost anything that his forces do so long as China ends up being advantaged, comes out on top, or looks strong? It’s reasonable to think that Xi may be either explicitly or implicitly sending the message down chain that it’s better to over-execute than to under-execute. It’s better to err on the side of aggressiveness. So Xi, in effect, may be consciously letting his wolf warriors and hawks loose on China’s neighbors and other nations.

IMPLICATIONS OF XI JINPING’S CHOICES

p. 86

Let’s put this all back together. The truth about the motivations, behaviors, and controls over China’s frontline forces is likely found somewhere in the middle of all three of the central questions offered above.

Chairman Xi has certainly emerged as one of the most powerful leaders China has ever seen. He does act like an emperor eagerly building empire. He clearly whips up fervency for China’s rejuvenation. And he does support using almost any measure and method available to achieve his dream of supremacy, the sooner the better. With a remarkable degree of tone-deafness, Xi continues to demonstrate a willingness to sanction tactics and approaches long after they prove to be counterproductive to China’s reputation and long-term interests, even if they erode trust for China in the region, and even if they make everything the PRC do seem suspect.

We have strong indications that Xi Jinping is generally aware of most things his frontline forces are doing, but not everything they are doing, which is perhaps a function of the unwieldiness of China’s governance model. History warns us of the dangers of dictatorships, the distortions in totalitarian states, where the truth doesn’t always flow quickly to an all-powerful authoritarian. Bad news is adulterated on the way up to Big Brother. Half-truths, falsities, incomplete data, and rosier-than-right reports thrive in bureaucratically threatening systems, because civil servants and generals are perpetually scared. They quite naturally protect themselves because there are few safeguards or protections for individuals. And history tells us that in tyrannical societies of this nature, this phenomenon is only going to get worse with time as information is increasingly modified to provide news the autocrat wants to hear.

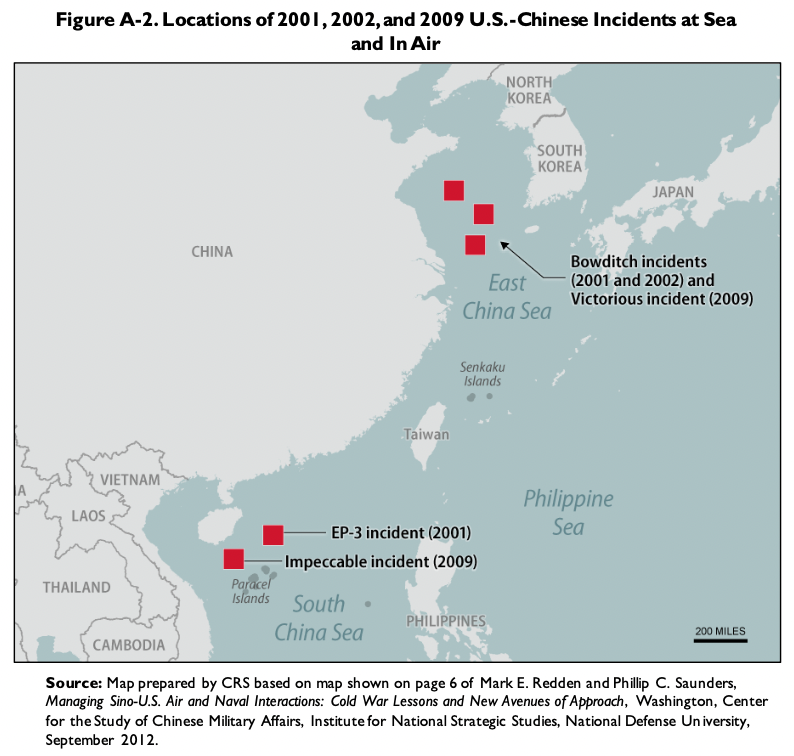

What this means, overall, is that we’re living in more unpredictable and dangerous times, when anything can happen. Going forward, the Indo-Pacific region and the world must not just contend with the dread of a hulking, temperamental China, but also its ever-growing war machine, which is a destabilizing force unto itself. We must not just grapple with the idea that China is becoming increasingly comfortable with using raw, naked power to advance its interests in almost every sector. Now we also need to worry about Chinese minions of all stripes that are eager to please, feel like they have a license to over-execute, and in their zealotry may end up committing a number of tactical mistakes or mishaps that could result in ruinous strategic outcomes. Recall the 2001 disaster, when an over-exuberant and under-skilled Chinese pilot hit a U.S. EP-3 operating on a routine patrol in international airspace.

The U.S. recognizes all these dangers, of course, and is responsibly trying to make sure we have reliable lines of communication with the Chinese, including “hot lines.” While we have multiple physical means of communicating with the PLA, the CCP generally continues to view communications as a lever to reward or punish not just the U.S., but nearly all foreign interlocutors. Simply stated, the PLA will talk only when they perceive such communication as an advantage—not, unfortunately, during an unfolding crisis, not following an incident, and to not to discuss strategic frictions. It would be in their best interest to do so, of course, especially since senior Chinese leaders may get a better set of facts (and sooner) from the American side than their own.

Meanwhile we can expect China to continue executing its grand strategy, which involves applying significant energy to advance its creeping expansionistic agenda. They’ll move forward using enticements, like dangling Belt and Road Initiative capital, and they’ll move forward using “gray zone” coercion, because they think these carrots and sticks work. But, unfortunately, we may not be able to trust that Xi is going to be sufficiently in control of his frontline forces.

This problem will likely get worse as China fields more unmanned systems. China is already deploying thousands of unmanned systems and the prospects that China will employ them for additional surveillance, harassment, exploitation, interference, and intimidation is high. We’ve already seen China deploy an incredible number of buoys—

p. 87

floating and anchored, unmanned surface vehicles, and unmanned underwater vehicles in the First Island Chain, around Taiwan, West Philippine Sea, Bering Sea, Central Pacific, near Australia, Indian Ocean, polar regions, and even around Africa. What are they doing with all these systems, the world should wonder?

In the end, if you exercise ultimate power, then you also own ultimate responsibility for what your forces do. Xi is the authoritarian atop an absolutist state, and he has the power to alter what his forces do or don’t do. Xi remains the accountable entity for all actions of his frontline forces.

CHINA’S RATIONALE FOR AGGRESSIVE FRONTLINE FORCE BEHAVIORS

If a Chinese official was here, he would reject all the above and claim China is the real victim in all this. He would say the U.S. remains locked into a “Cold War mindset” using outdated alliance systems, or blocs, that threaten China. He would declare that U.S. operations in the Indo-Pacific generate friction among nations and profess that our presence is fundamentally destabilizing. He would say America shouldn’t be in the Western Pacific in the first place. He might mention what a Chinese Defense Minister said years ago, that “Asia is for Asians,” a term coined by Imperial Japan in WWII—the same regime that touted the “East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere” (which, by the way, has striking parallels to China’s Belt and Road Initiative language).

The PRC official would say America and its allies constantly operate in China’s waters, in China’s airspace, or on China’s periphery. He would never admit that U.S. forces are actually operating lawfully in the international commons. He would proclaim that foreign air and maritime operations anywhere inside the first and second island chains are designed to keep China down, stop its rise, contain, encircle, and threaten China’s “core sovereignty” interests.

Truth told, this perspective makes a whole lot of sense if you’re stuck in a paranoiac Marxist-Leninist-style government that has a fundamental need of an archenemy—a longstanding opponent that China can blame for whatever ills affect the country, whatever sacrifices the country must make, or whatever actions they feel they must take externally in the name of “defense” for their country against a supposed implacable hegemon. This fear mongering is never going to go away on the Chinese side.

For all these reasons, China thinks America and its allies need to be pushed back and out. And they constantly experiment with novel ways to do that. Chinese academies, think tanks, and the PLA work round the clock to develop new tactics and techniques for their frontline forces, and they keep using whatever measures they can get away with—no matter how risky—if they think it helps achieve China’s goals.

On 60 minutes, Admiral Paparo, the Pacific Fleet commander, recently asked an important question. When China talks about America containing them, he asks, “China, are you doing anything that should be contained?” An analogy applies here. It’s like your neighbor not just claiming their own house and yard, but the public street in front of their house, the sidewalks, and then your own front lawn. And when you go out to deal with the attack dogs the neighbor left on your own front lawn, the offending neighbor himself feigns offense and cries, “you’re containing me!” Perhaps the neighbor should stick to his own legal property and simply follow public ordinances instead.221

***

221 Rear Admiral Mike Studeman, Commander, Office of Naval Intelligence, “Dangers Posed by China’s Frontline Forces,” remarks as prepared for the Sea Air and Space Conference, Washington, DC, April 5, 2023.

REPORT SUMMARY

Summary

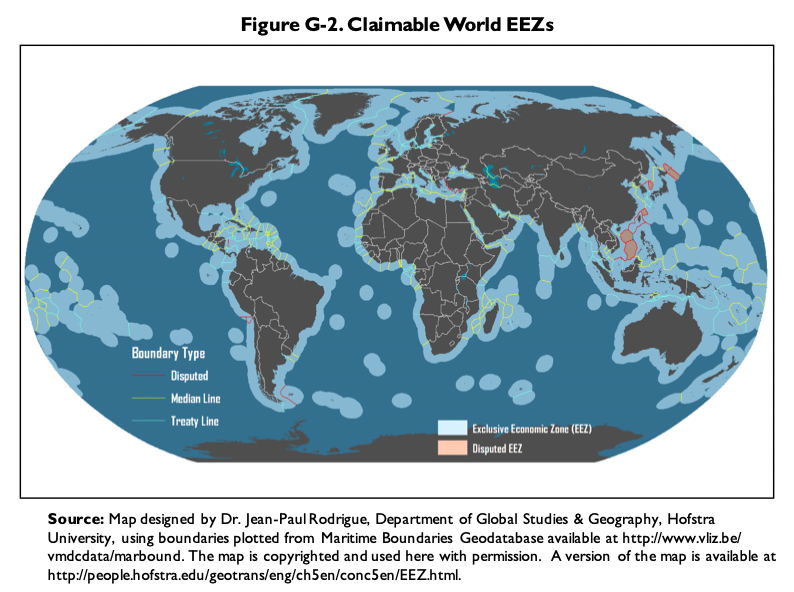

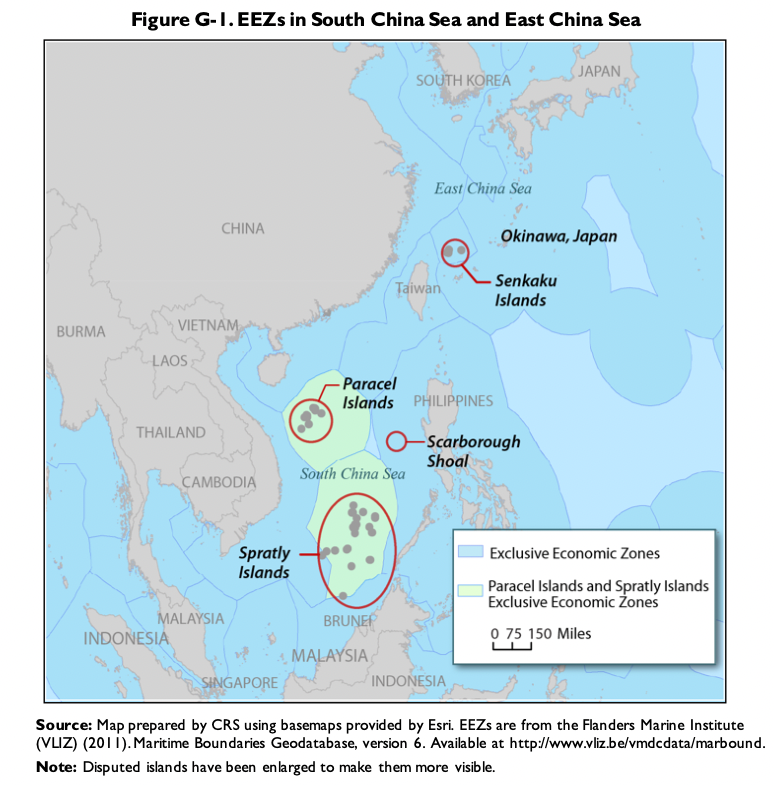

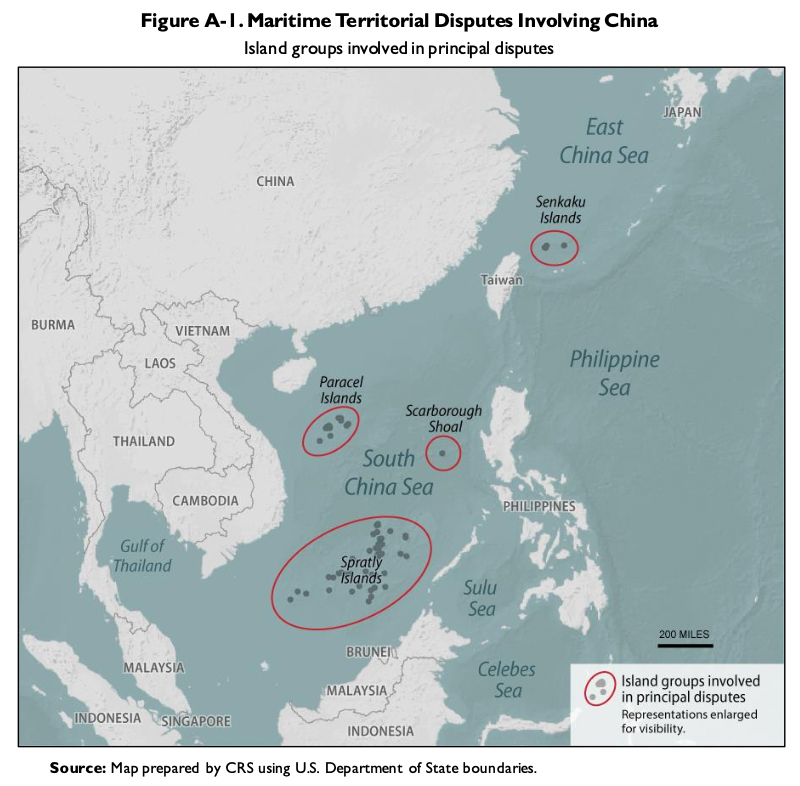

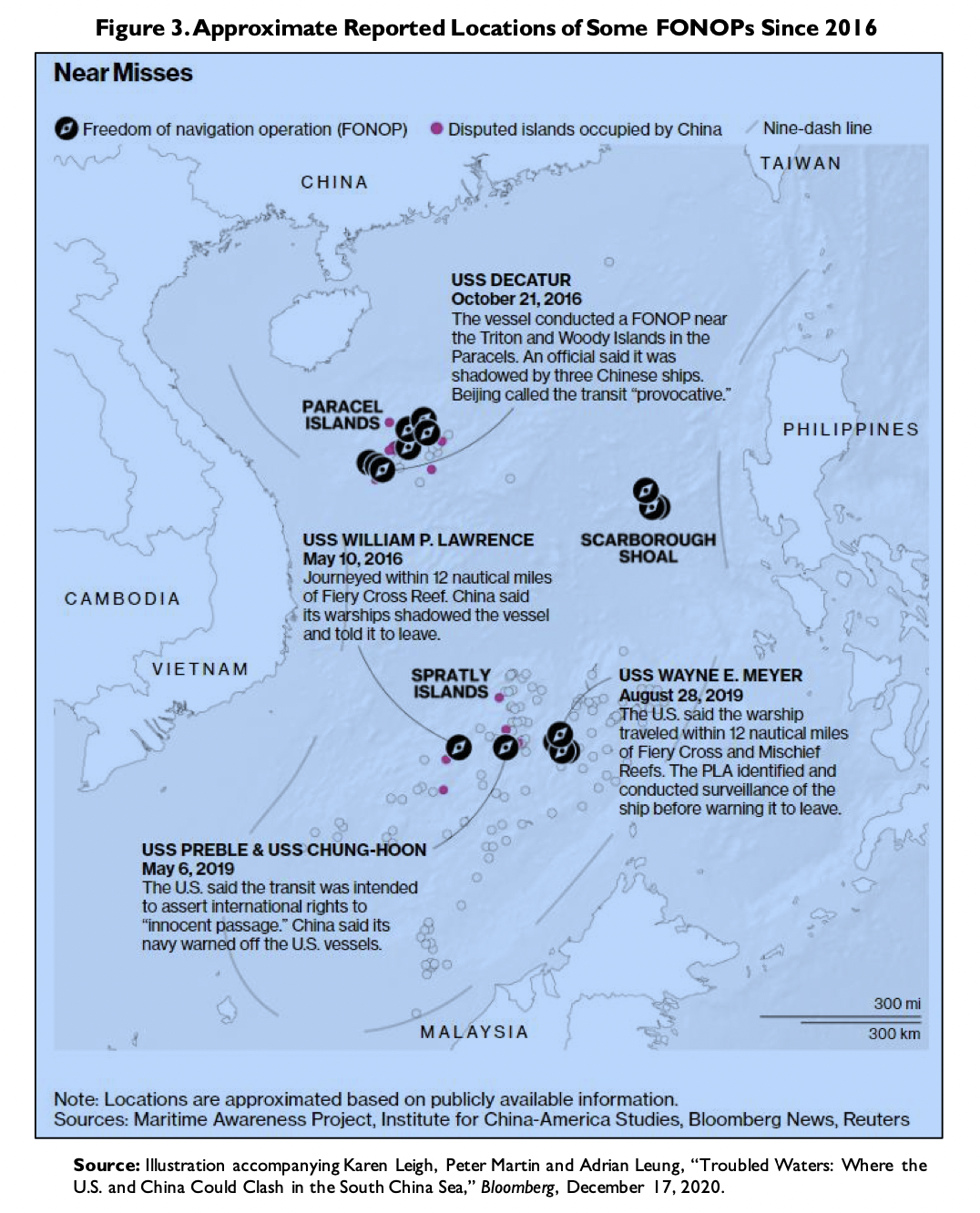

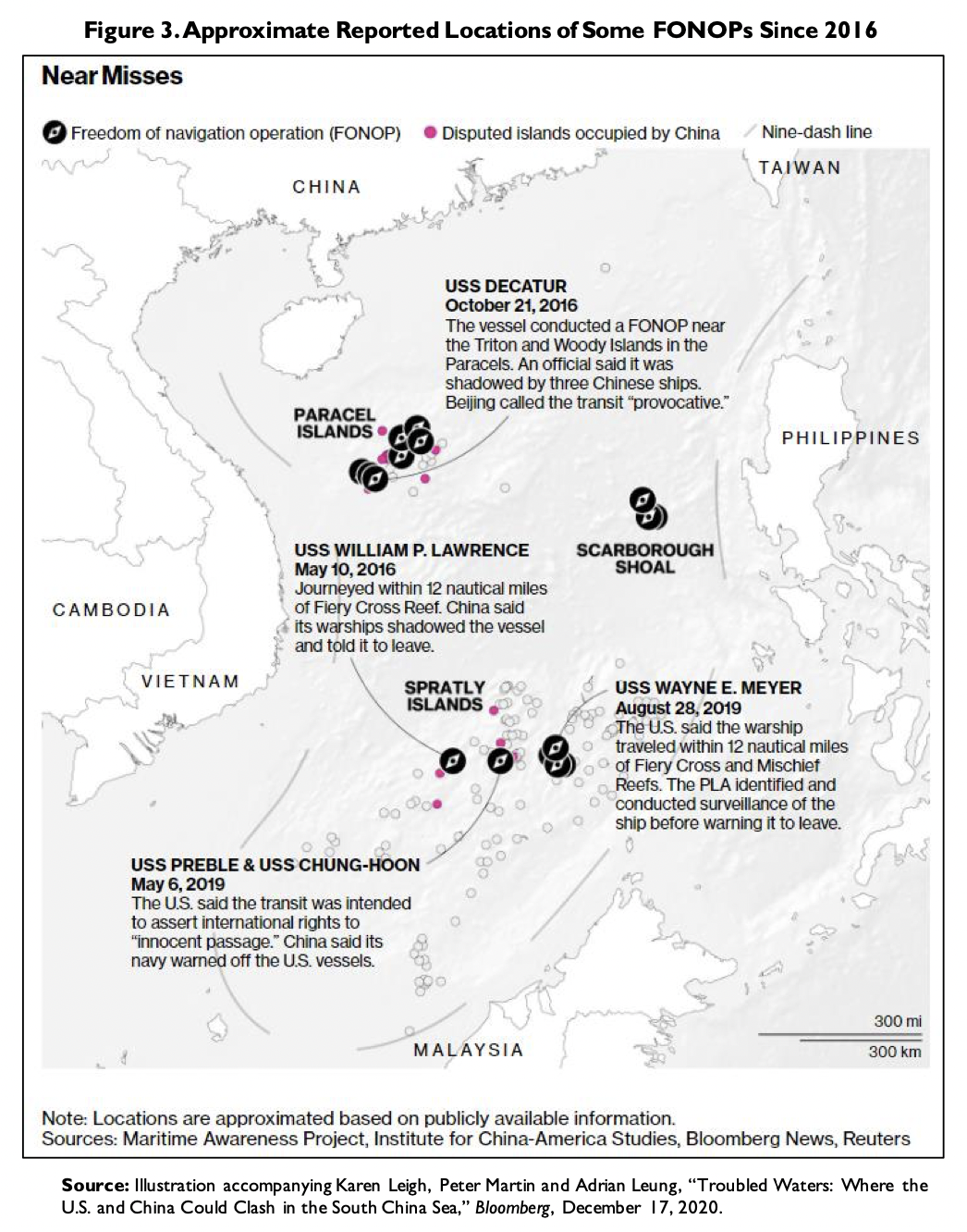

Over the past 10 to 15 years, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of strategic competition between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC, or China). China’s actions in the SCS—including extensive island-building and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. PRC domination of China’s near-seas region—meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea—could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.

Potential broader U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. security relationships with treaty allies and partner states; maintaining a regional balance of power favorable to the United States and its allies and partners; defending the principle of peaceful resolution of disputes and resisting the emergence of an alternative “might-makes-right” approach to international affairs; defending the principle of freedom of the seas, also sometimes called freedom of navigation; preventing China from becoming a regional hegemon in East Asia; and pursuing these goals as part of a larger U.S. strategy for competing strategically and managing relations with China.

Potential specific U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: dissuading China from carrying out additional base-construction activities in the SCS, moving additional military personnel, equipment, and supplies to bases at sites that it occupies in the SCS, initiating island-building or base-construction activities at Scarborough Shoal in the SCS, declaring straight baselines around land features it claims in the SCS, or declaring an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the SCS; and encouraging China to reduce or end operations by its maritime forces at the Senkaku Islands in the ECS, halt actions intended to put pressure against Philippine-occupied sites in the Spratly Islands, provide greater access by Philippine fisherman to waters surrounding Scarborough Shoal or in the Spratly Islands, adopt the U.S./Western definition regarding freedom of the seas, and accept and abide by the July 2016 tribunal award in the SCS arbitration case involving the Philippines and China.

The issue for Congress is whether the Administration’s strategy for competing strategically with China in the SCS and ECS is appropriate and correctly resourced, and whether Congress should approve, reject, or modify the strategy, the level of resources for implementing it, or both. Decisions that Congress makes on these issues could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.

AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY—RONALD O’ROURKE

Mr. O’Rourke is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the Johns Hopkins University, from which he received his B.A. in international studies, and a valedictorian graduate of the University’s Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, where he received his M.A. in the same field.

Since 1984, Mr. O’Rourke has worked as a naval analyst for the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress. He has written many reports for Congress on various issues relating to the Navy, the Coast Guard, defense acquisition, China’s naval forces and maritime territorial disputes, the Arctic, the international security environment, and the U.S. role in the world. He regularly briefs Members of Congress and Congressional staffers, and has testified before Congressional committees on many occasions.

In 1996, he received a Distinguished Service Award from the Library of Congress for his service to Congress on naval issues.

In 2010, he was honored under the Great Federal Employees Initiative for his work on naval, strategic, and budgetary issues.

In 2012, he received the CRS Director’s Award for his outstanding contributions in support of the Congress and the mission of CRS.

In 2017, he received the Superior Public Service Award from the Navy for service in a variety of roles at CRS while providing invaluable analysis of tremendous benefit to the Navy for a period spanning decades.

Mr. O’Rourke is the author of several journal articles on naval issues, and is a past winner of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Arleigh Burke essay contest. He has given presentations on naval, Coast Guard, and strategy issues to a variety of U.S. and international audiences in government, industry, and academia.

CLICK BELOW FOR THE FULL TEXT OF SOME OF THE PUBLICATIONS CITED IN O’ROURKE’S CRS REPORT:

Peter A. Dutton and Andrew S. Erickson, “When Eagle Meets Dragon: Managing Risk in Maritime East Asia,” RealClearDefense, 25 March 2015.

Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Records Expose China’s Maritime Militia at Whitsun Reef,” Foreign Policy, 29 March 2021.

Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Secretive Maritime Militia May Be Gathering at Whitsun Reef,” Foreign Policy, 22 March 2021.

Andrew S. Erickson,“Fact Sheet: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM),” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 29 April 2019.

Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 11 March 2019.

Andrew S. Erickson, “Shining a Spotlight: Revealing China’s Maritime Militia to Deter its Use,” The National Interest, 25 November 2018.

Andrew S. Erickson, “Exposed: Pentagon Report Spotlights China’s Maritime Militia,” The National Interest, 20 August 2018.

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA, China Maritime Report 1 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, March 2017).

Andrew S. Erickson and Emily de La Bruyere, “Crashing Its Own Party: China’s Unusual Decision to Spy on Joint Naval Exercises,” China Real Time Report (中国实时报), Wall Street Journal, 19 July 2014.

Andrew S. Erickson and Emily de La Bruyere, “China’s RIMPAC Maritime-Surveillance Gambit,” The National Interest, 29 July 2014.

Andrew S. Erickson, “PRC National Defense Ministry Spokesman Sr. Col. Geng Yansheng Offers China’s Most-Detailed Position to Date on Dongdiao-class Ship’s Intelligence Collection in U.S. EEZ during RIMPAC Exercise,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 1 August 2014.

“Andrew S. Erickson on the ‘Decade of Greatest Danger’,” interviewed by Eyck Freymann, The Wire China, 25 April 2021.