Adversaries and Planning Assumptions: China’s Navy and the Post-Cold War World

Andrew S. Erickson, “Adversaries and Planning Assumptions: China’s Navy and the Post-Cold War World,” in Evan Wilson and Paul Kennedy, eds., Planning for War at Sea: 400 Years of Great Power Competition (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2025), 317–39.

This chapter explains how and why the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has responded to changing circumstances—mainly its perception of foreign threats and technology—in the post-Cold War era.1 It probes the assumptions about the nature of the adversary and the required tasks that have shaped PLAN fleet design and development. China studies the U.S. military assiduously for both lessons for its own development and insights into how to counter in furtherance of key strategic goals, with unification over Taiwan long the ultimate objective.2 Here, paramount leader Xi Jinping’s determination to make historic achievements across the Taiwan Strait, his preoccupation with the U.S. as his most formidable enemy in the latter regard, and his perception of a limited window of opportunity are raising the risks of conflict.

Changing circumstances and strategy

Specifics of Beijing’s maritime strategy and development can be challenging to glean. As a Peking University scholar explains,

“China’s national government has never set forth a comprehensive list of its maritime interests, especially its core maritime interests. One reason for this is that China is developing too rapidly, so it is quite difficult to be certain of its interests, which are changing. Being intentionally vague will allow policy leeway in dealing with future uncertainties. Furthermore, vagueness also has some benefits of its own. Maintaining a vague position on the major issues of the East China Sea and the South China Sea is not only advantageous for flexibly handling maritime disputes with other countries, but helps to ease potential pressure from domestic public opinion and reduces unnecessary policy risk.”3

Nevertheless, carefully examining pedigreed sources reveals the broader outlines of China’s maritime trajectory.

PLAN thought is rooted in mid-twentieth-century history,4 but it has evolved considerably over the ensuing decades. Sino-American rapprochement in the 1970s ended the most difficult and threatening period of the Cold War for Beijing by removing American threats, affording support in deterring Soviet threats, and allowing for the PRC’s first naval efforts beyond its coastal waters. The People’s Republic’s unprecedented seaward turn was springboarded by the relatively intact and significant potential of its shipbuilding industry, which had been saved from the worst of Maoist malpractice by its physical unsuitability for relocation into China’s remote interior during the disastrous Third Front movement. As part of his modernization drive in the early 1980s, Deng prioritized shipbuilding industrial development to facilitate the export of manufactures around the world. In 1985, he assigned the PLAN its first-ever independent strategy: “Near Seas Active Defense,” focused on the dispute-filled Yellow, East, and South China Seas. There Beijing has the world’s most numerous and extensive disputed island and feature claims, with the largest number of other parties; none looms larger than Taiwan. The 1995–96 Taiwan Strait Crisis and 1999 Belgrade Embassy Bombing catalyzed a concerted People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and PLAN buildup that has already yielded dramatic results.5

Xi, the PRC’s first navalist leader, now seeks to transform China into a “maritime great power.” Two years after assuming office, in 2015, he added “Far Seas Protection”—a more modest version of U.S. and Western allied-style sea lane security—to the PLAN’s strategy. Subsequently, as two researchers explain, “On April 12, 2018, Xi Jinping attended the naval parade in the South China Sea, during which he called for [the service to] ‘strive to comprehensively build the People’s Navy into a world-class navy.’” They elaborate: “the only way to consider oneself a world-class navy is to have the power to match, contend with, and square off against any opponent; deter and win possible maritime conflicts; and forcefully support the country’s status as a world-class great power.”6

Circa 2018, as part of this effort, Xi extended the PLAN’s strategic and operational writ to all the world’s oceans, adding a third layer of PLAN strategy to include “near seas defense, far seas protection, [global] oceanic presence, and expansion into the two poles.”7 This latest, largest layer of PRC naval strategy and its operationalization remains a work in progress. A China Central Television Reporter’s interview of Yin Zhongqing, Deputy Chairman of the Finance and Economy Committee at the Thirteenth National People’s Congress, reveals similar language: “China must…do a better job protecting our territorial sea and controlling the near seas, enter the deep ocean, and move toward distant oceans until we reach Antarctica and the Arctic.”8

Thus prioritized, funded, and tasked, the PLAN is charged with leading the maritime component of Xi’s timeline for the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation.” By 2027, the timeline calls for achieving the “Centennial Military Building Goal” of capabilities to realize the PLA’s “founding mission” of vanquishing the Kuomintang (KMT), now on Taiwan. By 2035, it calls for completing military modernization. By 2049, it calls for becoming a strong country with world-class armed forces. There is a strong maritime component to national strategy throughout. As two researchers contend: “Threats to China’s national security primarily come from the sea, the focus of military struggle is at sea, and the center of gravity of China’s expanding national interests is also at sea.”9

Even approaching Xi’s ambitious goals would require eroding, and in some cases overturning, formidable Western advantages. The PLAN’s efforts to do so include (1) working increasingly jointly with other forces, including China’s land-based, missile-heavy “anti-Navy” forces; (2) attempting to impose risk by maximizing the numbers of PLAN vessels and the numbers of anti-ship missiles deployed on them, while accepting risk in battle damage survivability to reduce costs; and (3) pursuing new technologies and ways of war, such as unmanned systems and autonomous operations, that may disproportionately advantage China or target adversary vulnerabilities. … … …

INITIAL PAPER PRESENTATION:

Andrew S. Erickson, “Adversaries and Planning Assumptions: The Chinese Navy and the Post-Cold War World,” presented at Yale Naval History Conference on “Thinking About Enemies in Advance,” Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, Yale University, New Haven, CT, 21–23 April 2022.

VOLUME INFORMATION

How have navies contemplated possible enemies? How did they learn, or fail to learn, once operations began? How does this analysis inform today’s planning for future conflict? These questions guide the noted historians and naval strategists who contributed to Planning for War at Sea. A central theme is the regular failure of navies’ best-laid plans.

Covering four centuries of naval warfare, the chapters illustrate the challenges all navies faced when considering possible enemies. Even during the Age of Sail, ships were among the most expensive and long-term national endeavors. Navies therefore planned well in advance for future wars, usually without knowing their adversaries or how they would fight them at sea. Building a capable navy requires sustained investment in naval infrastructure long before the fighting starts.

In the final chapters naval strategists expand on this historical analysis to address how effectively or ineffectively today’s three leading navies—Russia, China, and the United States—have configured themselves during the post–Cold War era in preparing for future great power conflict. This collection is an important work for strategists, scholars, and policymakers.

Reviews

— Admiral John Richardson, USN (Ret.) 31st Chief of Naval Operations

“Kennedy, Wilson and their world-class contributors provide a warning from the past, examining the causes of naval strategic failure in a succession of case studies that highlight the impact of flawed pre-war assumptions, outmoded plans, and ill-suited equipment. Today, with the biggest navies belonging to continental powers, and technology evolving by the day, the potential for catastrophic failure has never been greater. Essential reading.”

— Prof. Andrew Lambert, Laughton Professor of Naval History, Kings College, London

“In Planning for War at Sea, we see the enormous value of a deep knowledge of the past for helping us ask better questions about strategy and planning for our contemporary world. Kennedy and Wilson bring together insightful chapters from some of our leading naval scholars to share the wisdom naval history has to offer today’s naval professionals.”

— Benjamin “BJ” Armstrong, editor of 21st Century Mahan, Revised and Expanded: Sound Military Conclusions for the Modern Era

“This is an impressive and valuable collection of thought-provoking essays. It is timely, given the ways recent conflicts—like those in Ukraine and Afghanistan—have forced us to reassess how best to plan and prepare for war. Wilson, Kennedy, and their contributors review historical approaches to that challenge from a maritime perspective and illuminate how difficult and important it can be.”

About the Editors

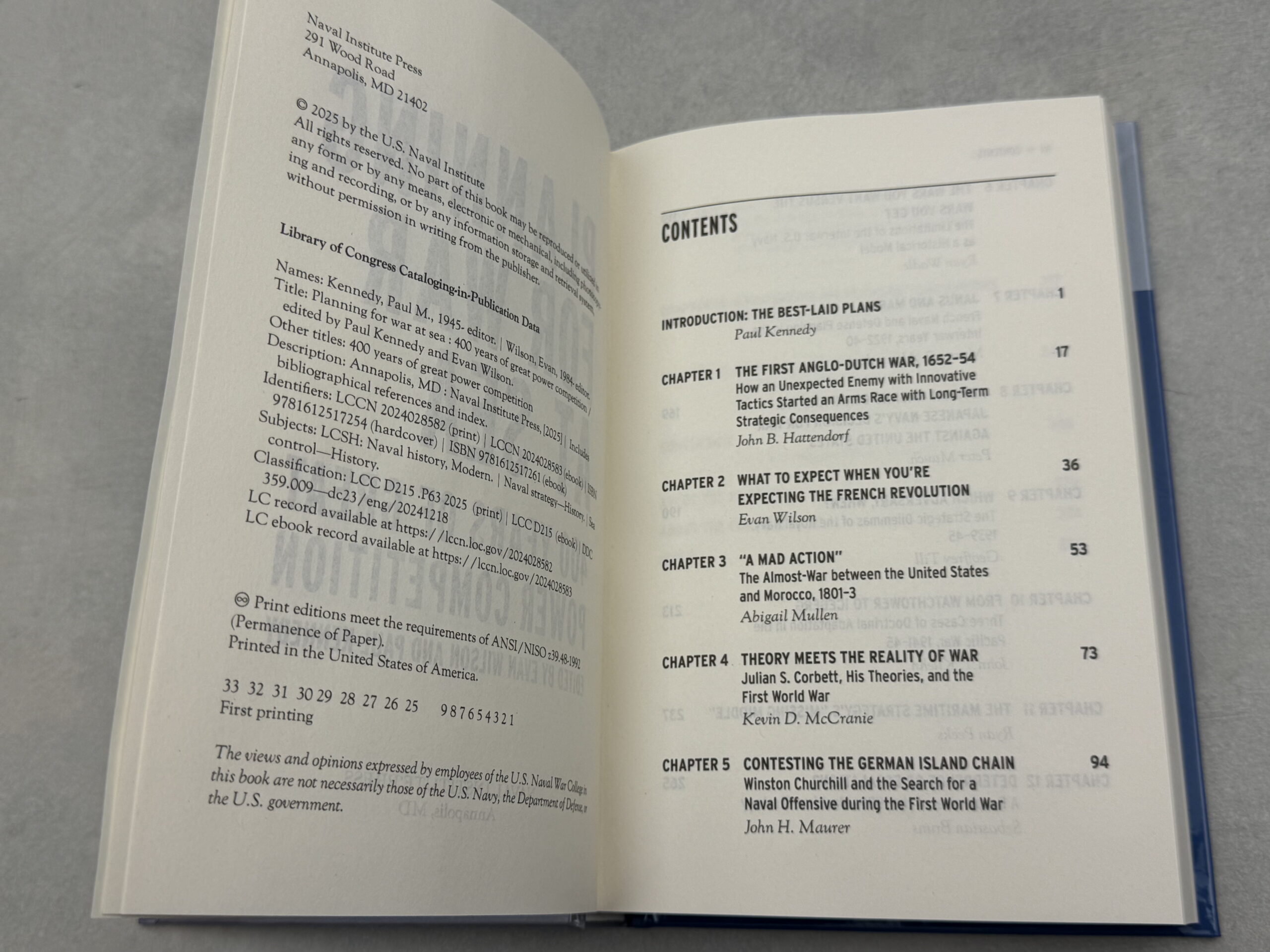

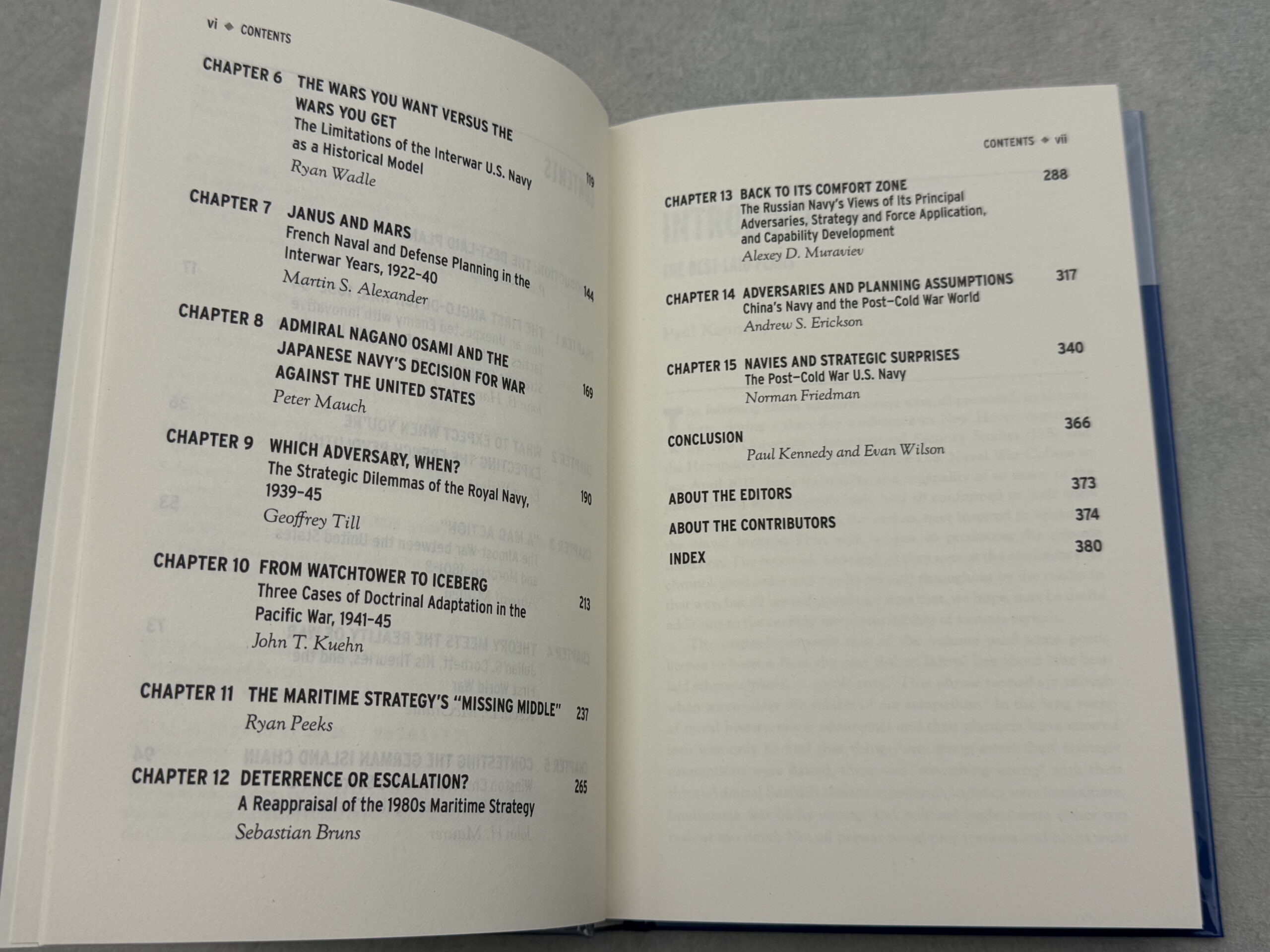

Evan Wilson is an associate professor at the U.S. Naval War College’s Hattendorf Historical Center in Newport, Rhode Island. A recipient of the Sir Julian Corbett Prize in Modern Naval History, he is the author or editor of six books, most recently The Horrible Peace: British Veterans and the End of the Napoleonic Wars.

Paul Kennedy is J. Richardson Dilworth Professor of History and Distinguished Fellow of the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University. He is author or editor of twenty books, the latest being Victory at Sea: Naval Power and the Transformation of the Global Order in World War II.