Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: An Ambitious and Uncertain Course—CMSI Vol. 6 in Naval Institute Press “Studies in Chinese Maritime Development” series

Andrew S. Erickson, ed., Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: An Ambitious and Uncertain Course (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016; paperback 15 February 2023).

- Paperback edition released in 2023!

- As with the previous five volumes in our “Studies in Chinese Maritime Development” series, an Amazon Kindle edition is available.

Author of:

- Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Military Shipbuilding Industry Steams Ahead, On What Course?” 1–16.

- Andrew S. Erickson, Jonathan Ray, and Robert T. Forte, “Underpowered: Chinese Conventional and Nuclear Naval Power and Propulsion,” 238–48.

Andrew S. Erickson, ed., Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: An Ambitious and Uncertain Course (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016).

ISBN-10: 1682470814

ISBN-13: 978-1682470817

Hardcover: 376 pages

Official release date: December 15, 2016

Series: Studies in Chinese Maritime Development

BOOK DESCRIPTION

One of this century’s most significant events, China’s maritime transformation is already making waves. Yet China’s course and its implications, including at sea, remain highly uncertain―triggering intense speculation and concern from many quarters and in many directions. It has never been more important to assess what ships China can supply its navy and other maritime forces with, today and in the future. China’s shipbuilding industry has grown more rapidly than any other in modern history. Commercial shipbuilding output jumped thirteen-fold from 2002-12. Beijing has largely met its goal of becoming the world’s largest shipbuilder by 2015. Yet progress is uneven, with military shipbuilding leading overall but with significant weakness in propulsion and electronics for military and civilian applications alike. Moreover, no other book has answered three pressing questions: What are China’s prospects for success in key areas of naval shipbuilding? What are the likely results for China’s navy? What are the implications for the U.S. Navy?

To address these critical, complex issues, this volume brings together some of the world’s leading experts and linguistic analysts, often pairing them in research teams. These sailors, scholars, analysts, industry experts, and other professionals have commanded ships at sea, led shipbuilding programs ashore, toured Chinese vessels and production facilities, invested in Chinese shipyards and advised others in their investment, and analyzed and presented important data to top-level decision-makers in times of crisis. In synthesizing their collective insights, the book fills a key gap in our understanding of China, its shipbuilding, its navy, and what it all means.

Their findings will fascinate and concern you. While offering different perspectives, they largely agree on several important points. Through a process of “imitative innovation,” China has been able to “leap frog” some naval development, engineering, and production steps and achieve tremendous cost and time savings by leveraging work done by the U.S. and other countries. China’s shipbuilding industry is poised to make the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) the second largest navy in the world by 2020, and―if current trends continue―a combat fleet that in overall order of battle (i.e., hardware-specific terms) is quantitatively and even perhaps qualitatively on a par with that of the U.S. Navy by 2030. Already, Chinese ship-design and -building advances are increasing the PLAN’s ability to contest sea control in a widening arc of the Western Pacific.

China continues to lack transparency in important respects, but much is knowable through the interdisciplinary research approach pioneered by the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute in the series “Studies in Chinese Maritime Development,” of which this is the sixth volume.

BLURBS

“A nation’s shipbuilding capabilities and capacities can promote or constrain its strategy and ambitions at sea. Mahan knew this, and so do the Chinese. This new volume from CMSI is a great source of insights on China’s shipbuilding industrial base and the means that will be at Beijing’s disposal in the future. I would recommend it to anyone who wants to better understand the competition for maritime superiority that is looming before us.”

—Congressman J. Randy Forbes, Chairman, House Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee

“A good book on a very important set of questions. Now and in the future we need to know as much as we can about the capabilities and practices of the organizations that design, build, and maintain the ships of China’s navy and its auxiliaries.”

—Andrew W. Marshall, former Director, Office of Net Assessment, Pentagon

“Does China have the means to become a leading global naval power? In the coming decades, can China’s design bureaus, shipyards, and supporting industries build the fleet it will need to fulfill this lofty ambition? This thorough, well-researched, and original volume provides answers to these vitally important questions. Essential reading for analysts, policymakers, naval officers, and American citizens concerned with their country’s future as the world’s preponderant sea power.”

—Aaron L. Friedberg, Professor of Politics and International Affairs, Princeton University

“To understand China’s naval future, we must understand what its shipbuilding industry can provide. This path-breaking volume points the way.”

—Evan S. Medeiros, former Senior Director for Asian Affairs, U.S. National Security Council

“China’s intention to become a major maritime power in the coming decades is well known, but much less appreciated are the means by which it will attain that status. Andrew Erickson’s Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: An Ambitious and Uncertain Course thoughtfully, clearly, and factually presents the many facets of China’s commercial and naval shipbuilding ambition and the sobering scope of that national enterprise. To project China’s direction and pace in maritime and global affairs and their impact on U.S. maritime power without absorbing the insights of this book’s extraordinary contributors would be a huge mistake and a sure way to get the future wrong. A must at the top of every national security reading list.”

—Admiral Gary Roughead, USN (Ret.), 29th Chief of Naval Operations

“The contributors to this volume shed new light on an important but under-studied topic: the industrial sinews of China’s naval modernization and expansion. It deserves to be studied by scholars and policy makers alike.”

—Thomas G. Mahnken, President and CEO, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments

REVIEWS

“…the book provides authoritative, in-depth analysis of an area crucial to current and future global naval developments that makes it essential reading for any serious student of contemporary maritime affairs.”

—Conrad Waters, “Naval Books of the Year,” Warship 2019: 203–04.

“The level of scholarship seems to be very good… the source material is derived a combination of US military intelligence reports, publicly available journals, news sources, and shipping information, commercially available satellite imaging, and translated Chinese military reports and journals, news articles, and government reports and economic proclamations. The book provides a very thorough assessment of the Chinese commercial shipbuilding industry and the naval military/naval industry. … The book also provides a very good look into the Chinese shipbuilding and associated governmental organization and structure.”

—Bayard B., “Comprehensive with High Level of Scholarship,” Review, Amazon.com, 3 February 2019.

“Specialized researchers may want to utilize the entire series, while college and university faculty members and high school teachers will find Chinese Naval Shipbuilding indispensable as a source for teaching about modern China. This is the only book to bring together the history of the PLAN with an explanation of the present situation and projections for the future. …a must for… teaching about what is happening under the seas, on the seas, and above the seas.”

—Andrew M. McGreevy, Education About Asia 23.1 (Spring 2018): 63–64.

“In his introduction, Andrew S. Erickson borrows a Chinese phrase frequently cited in the Chinese media to describe the speed of launching new warships in recent years: ‘In recent years, China’s navy has been launching new ships like dropping dumplings’ (下饺子) into soup broth. Chinese people like this phrase, which signifies China’s growing maritime capabilities, while other countries in China’s neighborhood exhibit concerns. A well-known analyst specializing in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in general and the PLA Navy (PLAN) in particular, Erickson tries to answer such questions as what are the drivers contributing to this phenomenon? How advanced are these warships compared with Western counterparts? What progress has been made in China’s shipbuilding industry, and what are the constraining elements in this sector? What is the likely picture for China’s naval development by 2030, and what are the implications for the US Navy? To respond to these questions, Erickson assembled a diverse group of naval officers, scholars, industrial analysts, PLA experts, and related professionals to discuss China’s shipbuilding sector. This book is the product of the conference, held in 2015. … The arrangement of chapters is logical, and the ground covered is thorough. … In terms of quality, China’s shipbuilding industry has entered an ‘imitation and innovation’ period, able to conduct reverse engineering and master new technologies after three decades of trial and error. Nevertheless, there are technological hurdles that have to be overcome before 2030. In the field of power and propulsion, as pointed out by Erickson, Jonathan Ray, and Robert Forte, China still relies on imported diesel and gas turbines, while air-independent power is not able to offer enough power, and progress in lithium-ion batteries needs to be tested. Progress has been made in developing nuclear reactors for submarines but not enough to support aircraft carriers. … The book makes a large contribution to our understanding of the status and progress of China’s shipbuilding industry. All of the authors have made very good use of the available public sources, including the Chinese government’s policy announcements and regulations, industrial analyses, and individual enterprises’ publications, and this enables them to make a knowledgeable assessment of the progress in China’s shipbuilding industry.”

—Arthur S. Ding, The China Journal 79 (January 2018): 195–197.

“Very comprehensive and useful study on a huge topic, the book will meet the needs of those interested in PLA and China defense related issues.”

—Eric Grillon, 5-Star Review, Amazon.com, 13 December 2017.

“…the sixth volume in the China Maritime Studies Institute and the United States Naval Institute series, Studies in Chinese Maritime Development, and like its predecessors this book is an authoritative work of international scholarship. …chapters written by some of the world’s leading China experts that systematically cover the significant features of China’s military shipbuilding industry. In an environment where much of the Chinese naval effort lacks transparency this book delves down into the nuts and bolts …although each chapter is itself a treasure trove of information and analysis that providing great insight into its own particular subject, [in] collective synthesis ‘this book fills a key gap in our understanding of China, its shipbuilding, its navy, and what it all means’. …highly recommended for everyone who wants to better understand our future… …helps to fill the knowledge gap that informs fact based commentary on China. If you don’t believe you need to better understand the future importance of shipbuilding in China, then you will be sure to witness a major strategic surprise over the next few years. Chinese Naval Shipbuilding is healthy food for the brain.”

—Gregory P. Gilbert; prepared originally for International Journal of Maritime History, published online via the Australian Naval Institute, 23 September 2017.

“goes a long way towards clearing up the misconceptions of the PLAN and their shipbuilding directions into the future.”

—M. C. Huitron, 5-Star Review, Amazon.com, 2 August 2017.

“This is a good…summation of China’s shipbuilding capabilities. …the references are outstanding, particularly if you are able to read Chinese.”

—Amazon Customer, 4-Star Review, Amazon.com, 19 July 2017.

“According to the editor, China’s naval shipbuilding industry is an overlooked element in the country’s overall growth strategy and policy goals. The contributors – comprising sailors, scholars and industry professionals – seek to assess China’s prospects in key areas of shipbuilding and the potential implications for the US Navy.”

—Survival: Global Politics and Strategy 59.4 (August–September 2017): e4.

“A very knowledgeable book for someone interesting in naval technology and its progress and forecast in China.”

—Khurram Shahzadon, 4-Star Review, Amazon.com, 27 June 2017.

“…since around 2000, [China] has powered ahead to the point that it has become the world’s biggest shipbuilder; the owner of one of the largest cargo fleets; the biggest fishing nation; and a very big player in offshore oil and gas. In short, it has very rapidly become a very significant maritime nation. It is not surprising, then, that the United States’ defence establishment and, most particularly, its naval intelligentsia… have begun to take a very close interest in Chinese matters maritime. This excellent and wide-ranging book represents a very strong expression of that interest. …a very strong interest and knowledge of current Chinese naval affairs. The book makes it obvious that the next decade will be very important and probably exciting as far as US/China naval relations are concerned.”

—Ausmarine (May/June 2017): 60.

“Breathtaking in scope and importance is the only way to adequately describe [this] book… edited and with an introduction written by the redoubtable Dr. Andrew Erickson. Seeing the breadth and depth of naval—and merchant—ship construction in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) leaves no doubt as to the global strategic agenda and capability, current and future, of Beijing. Certainly nothing has been seen like it in China since the great era of Adm. Zheng He in the 15th Century. …Too much to discuss in one review. Let me just say: This book will remind you of the US’ leap into global influence with Teddy Roosevelt’s pre-Presidential work to transform the U.S. Navy.”

—Gregory Copley, “Essential Reading: Important New Strategic Literature,” Defense and Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy 2 (2017): 16.

“This is one of the best in an excellent series of books the US Naval Institute Press has produced on China.”

—Peter Hore, “China Reaches for Maritime Manifest Destiny,” Warships: International Fleet Review (April 2017): 47–48.

“This is an important, timely and indeed ambitious book at a pivotal moment in world history.”

—The Navy Magazine, Australian Navy League, 79.1 (January-March 2017).

“the best reference on China’s maritime march is the recent Chinese Naval Shipbuilding, the work of the U.S. Naval War College’s impressive China Maritime Studies Institute….”

—Admiral Gary Roughead, USN (Ret.), 29th Chief of Naval Operations, Forbes, 20 January 2017.

“China’s shipbuilding industry has grown more rapidly than any other in modern history. China is the world’s leading shipbuilder. I was most interested to learn what Dr. Andrew Erickson had to say in his latest book ‘Chinese Naval Shipbuilding’. Professor Erickson is a Professor of Strategy at the Naval War College. He is considered a giant in his field. The book is divided into five sections describing the Peoples Republic of China’s shipbuilding industry’s foundation and resources, infrastructure, approach to naval architecture and design, remaining challenges and a section which provides strategic conclusions and predictions for the future of American naval and maritime power. The book is a collection of articles under each of the five sections. Also include are multiple graphs, tables and illustrations as resources. The one article I was most interested in [was] by Carlson and Bianchi who discuss the change in the Chinese naval plans from near coast defense to near seas and now to far seas operations. They also review the resources, capabilities and objectives adapted to reach their goals. They claim this evolution brought an increase in the complexity and technical sophistication to the Chinese military shipbuilding industry. Various articles also discuss the Jiangkai-II class guided missile frigate, and the Stirling Engine Air Independent Propulsion systems and Lithium-ion battery storage systems for its submarines. They also review the Chinese aircraft carries and nuclear propulsion technologies. The book is easy to read and well researched. It is 376 pages’ hardcover.”

—Jean, “Really Liked It,” 4-Star Review, Goodreads, 27 January 2017.

“…adds the most recent volume to Dr. Andrew Erickson’s excellent edited collections on the increase of the People’s Republic’s military, economic, and industrial power… provides a nuanced and insightful view of a major Chinese strategic investment, its shipbuilding industry, and is required reading for anyone, academic or layman, trying to understand the associated capabilities and implications of the People’s Republic’s maritime rise. … The articles are easily readable, each approximately ten to fifteen pages of crisp, synthesized content, with end notes allowing readers to further explore the author’s research, although most references are translated from Mandarin Chinese. The works also feature multiple graphs, tables, and illustrations, providing further resources for students and researchers. … Overall, Chinese Naval Shipbuilding provides a very useful window into an area of intense Communist Party strategic investment. The work gives the reader an excellent overview of the industry as a whole, overlapped with strategic context and geopolitical implications. …the volume also provides a unique look at the industry’s challenges…. Nuanced and complex, it describes both the accomplishments of an industry that now leads the world in commercial tonnage produced, but also lags behind in critical areas mastered by much smaller and less-rich nations. Erickson’s volume is a worthy addition to his series and an enjoyable read.”

—Michael DeBoer, Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 9 January 2017.

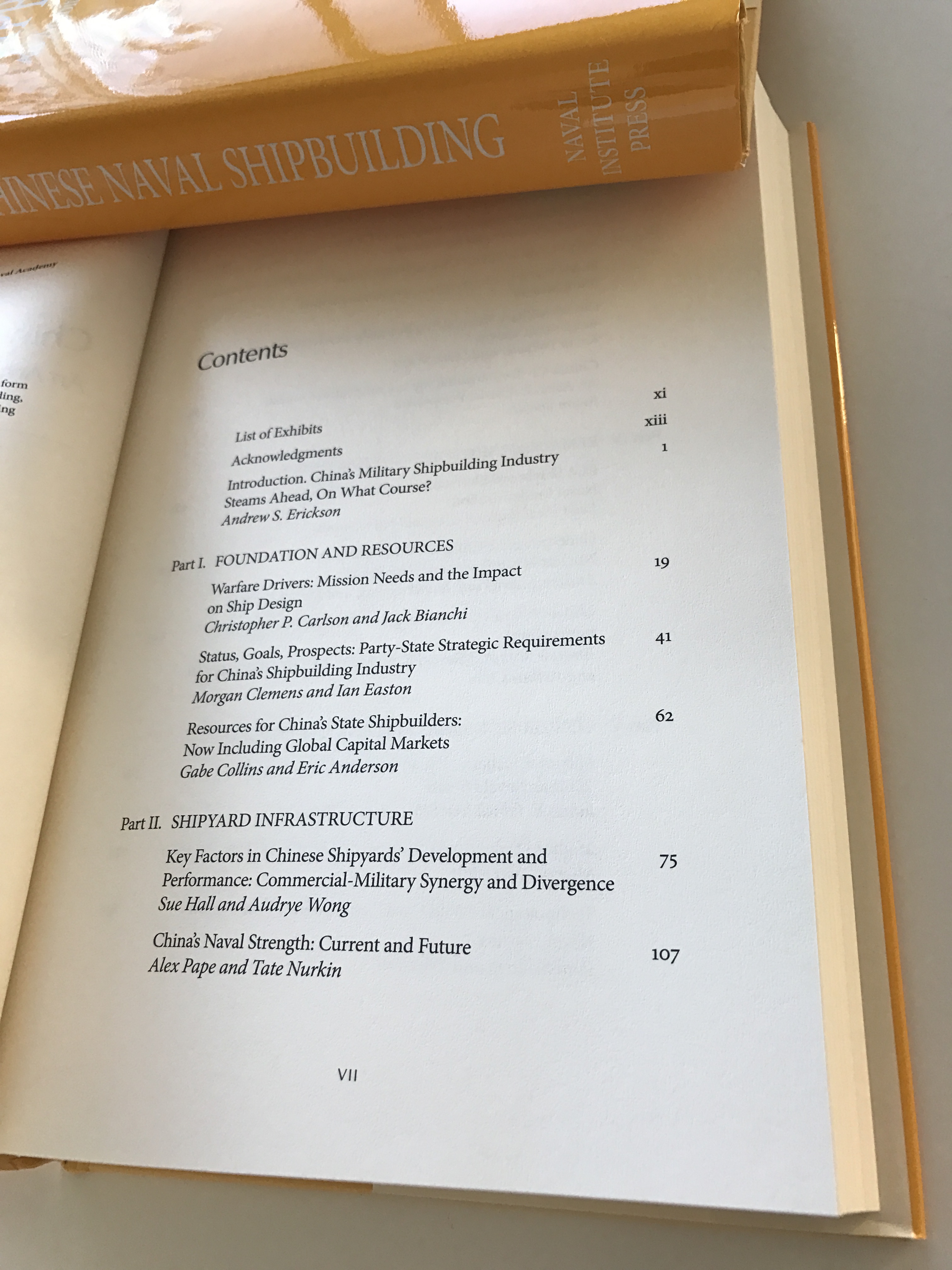

CONTENTS OF VOLUME

List of Exhibits

Acknowledgments

Introduction. China’s Military Shipbuilding Industry Steams Ahead, On What Course?

Andrew S. Erickson

Part I. FOUNDATION AND RESOURCES

Warfare Drivers: Mission Needs and the Impact on Ship Design

Christopher P. Carlson and Jack Bianchi

Status, Goals, Prospects: Party-State Strategic Requirements for China’s Shipbuilding Industry

Morgan Clemens and Ian Easton

Resources for China’s State Shipbuilders: Now Including Global Capital Markets

Gabe Collins and Eric Anderson

Part II. SHIPYARD INFRASTRUCTURE

Key Factors in Chinese Shipyards’ Development and Performance: Commercial-Military Synergy and Divergence

Sue Hall and Audrye Wong

China’s Naval Strength: Current and Future

Alex Pape and Tate Nurkin

Monitoring Chinese Shipbuilding Facilities with Satellite Imagery

Sean O’Connor and Jordan Wilson

Civil-Military Integration Potential in Chinese Shipbuilding

Daniel Alderman and Rush Doshi

Part III. NAVAL ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN

PLAN Warship Construction and Standardization

Mark Metcalf

China’s Military Shipbuilding Research, Development, and Acquisition System

Kevin Pollpeter and Mark Stokes

China’s Civilian Shipbuilding in Competitive Context: An Asian Industrial Perspective

Julian Snelder

Part IV. REMAINING SHIPBUILDING CHALLENGES

PLA Shipboard Electronics: Impeding China’s Naval Modernization

Leigh Ann Ragland-Luce and John Costello

Underpowered: Chinese Conventional and Nuclear Naval Power and Propulsion

Andrew S. Erickson, Jonathan Ray, and Robert T. Forte

China’s Aircraft Carrier Program: Drivers, Developments, Implications

Andrew Scobell, Michael E. McMahon, Cortez A. Cooper III, and Arthur Chan

Part V. CONCLUSIONS AND ALTERNATIVE FUTURES

Maximal Scenario: Expansive Naval Trajectory to “China’s Naval Dream”

James E. Fanell and Scott Cheney-Peters

Medium Scenario: World’s Second “Far Seas” Navy by 2020

Michael McDevitt

Technological “Wild Cards” and Twenty-First-Century Naval Warfare

Paul Scharre and Tyler Jost

How China’s Shipbuilding Output Might Affect Requirements for U.S. Navy Capabilities

Ronald O’Rourke

List of Acronyms

About the Contributors

Index

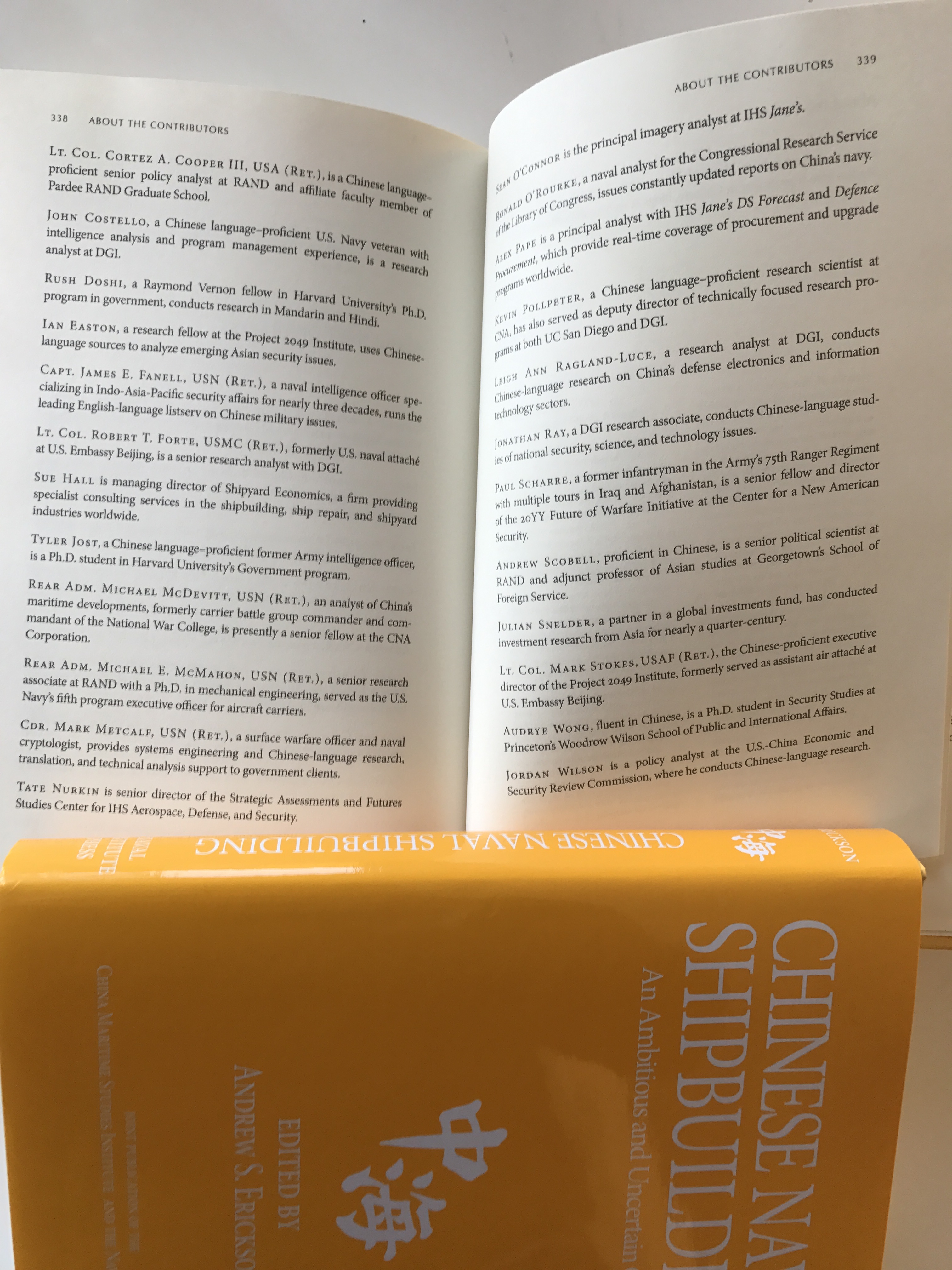

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

Daniel Alderman, a deputy director at Defense Group, Inc. (DGI), is Chinese language–proficient and oversees analytic production at DGI’s Center for Intelligence Research and Analysis.

Eric Anderson, a Chinese-proficient research analyst, leads Sino-American sectoral innovation analysis at the University of California (UC), San Diego’s Study of Innovation and Technology in China (SITC) project.

Jack Bianchi, a research associate at DGI, employs Chinese-language sources to analyze China’s defense-related science and technology development.

Capt. Christopher P. Carlson, USNR (Ret.), a submariner and intelligence officer, designs war games and has published a wide range of articles and books.

Arthur Chan, a research associate at RAND, is proficient in Chinese.

Scott Cheney-Peters, a civil servant at the State Department and a Reserve surface warfare officer, is founder and president of the Center for International Maritime Security.

Morgan Clemens, a research analyst at DGI, studies China’s armed forces and defense industry using Chinese-language sources.

Gabe Collins, a licensed Texas attorney, conducts security, commodity, and market research in Chinese, Russian, and Spanish.

Lt. Col. Cortez A. Cooper III, USA (Ret.), is a Chinese language– proficient senior policy analyst at RAND and affiliate faculty member of Pardee RAND Graduate School.

John Costello, a Chinese language–proficient U.S. Navy veteran with intelligence analysis and program management experience, is a research analyst at DGI.

Rush Doshi, a Raymond Vernon fellow in Harvard University’s Ph.D. program in government, conducts research in Mandarin and Hindi.

Ian Easton, a research fellow at the Project 2049 Institute, uses Chinese-language sources to analyze emerging Asian security issues.

Capt. James E. Fanell, USN (Ret.), a naval intelligence officer specializing in Indo-Asia-Pacific security affairs for nearly three decades, runs the leading English-language listserv on Chinese military issues.

Lt. Col. Robert T. Forte, USMC (Ret.), formerly U.S. naval attaché at U.S. Embassy Beijing, is a senior research analyst with DGI.

Sue Hall is managing director of Shipyard Economics, a firm providing specialist consulting services in the shipbuilding, ship repair, and shipyard industries worldwide.

Tyler Jost, a Chinese language–proficient former Army intelligence officer, is a Ph.D. student in Harvard University’s Government program.

Rear Adm. Michael McDevitt, USN (Ret.), an analyst of China’s maritime developments, formerly carrier battle group commander and commandant of the National War College, is presently a senior fellow at the CNA Corporation.

Rear Adm. Michael E. McMahon, USN (Ret.), a senior research associate at RAND with a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering, served as the U.S. Navy’s fifth program executive officer for aircraft carriers.

Cdr. Mark Metcalf, USN (Ret.), a surface warfare officer and naval cryptologist, provides systems engineering and Chinese-language research, translation, and technical analysis support to government clients.

Tate Nurkin is senior director of the Strategic Assessments and Futures Studies Center for IHS Aerospace, Defense, and Security.

Sean O’Connor is the principal imagery analyst at IHS Jane’s.

Ronald O’Rourke, a naval analyst for the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress, issues constantly updated reports on China’s navy.

Alex Pape is a principal analyst with IHS Jane’s DS Forecast and Defence Procurement, which provide real-time coverage of procurement and upgrade programs worldwide.

Kevin Pollpeter, a Chinese language–proficient senior research scientist at CNA, has also served as deputy director of technically focused research programs at both UC San Diego and DGI.

Leigh Ann Ragland-Luce, a research analyst at DGI, conducts Chinese-language research on China’s defense electronics and information technology sectors.

Jonathan Ray, a DGI research associate, conducts Chinese-language studies of national security, science, and technology issues.

Paul Scharre, a former infantryman in the Army’s 75th Ranger Regiment with multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, is a senior fellow and director of the 20YY Future of Warfare Initiative at the Center for a New American Security.

Andrew Scobell, proficient in Chinese, is a senior political scientist at RAND and adjunct professor of Asian studies at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service.

Julian Snelder, a partner in a global investments fund, has conducted investment research from Asia for nearly a quarter-century.

Lt. Col. Mark Stokes, USAF (Ret.), the Chinese-proficient executive director of the Project 2049 Institute, formerly served as assistant air attaché at U.S. Embassy Beijing.

Audrye Wong, fluent in Chinese, is a Ph.D. student in Security Studies at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

Jordan Wilson is a policy analyst at the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, where he conducts Chinese-language research.

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Andrew S. Erickson, a U.S. Naval War College Professor of Strategy and associate-in-research at Harvard University’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies who is proficient in Chinese, blogs at www.andrewerickson.com.

LIST OF EXHIBITS

Exhibit 0-1. Significant Chinese Naval Shipyards

Exhibit 0-2. China’s Primary Order of Battle (Major Combatants), 1985–2030

Exhibit 1-1. Evolution of China’s Naval Strategy—Impact on PLAN Warfare Area Capabilities

Exhibit 4-1. Shipbuilding Production Trends Since 1990 (in millions of compensated gross tons)

Exhibit 4-2. Historical Shipbuilding Production (in millions of gross tons)

Exhibit 4-3. Trends in Production, Ordering, and Forward Orderbook for World Shipbuilding (in millions of compensated gross tons)

Exhibit 4-4. World Historical Production and Orderbook Phasing (in millions of compensated gross tons)

Exhibit 4-5. China Historical Production and Orderbook Phasing

Exhibit 4-6. Top 20 Chinese Shipbuilders from China’s Shipyards Report 2003

Exhibit 4-7. Top 20 Chinese Shipbuilders, 2012

Exhibit 4-8. Shipbuilding Throughput Comparison of Major Shipbuilders

Exhibit 4-9. Shipbuilding Throughput Changes for Chinese Shipbuilders

Exhibit 4-10. New Ship Price Volatility

Exhibit 4-11. Complexity Ranking of Ships According to Average Compensated Gross Ton (CGT) Coefficient

Exhibit 4-12. Composition of Chinese Shipbuilding Production by Size and Complexity

Exhibit 5-1. Estimated Chinese Investment in Naval Ship Construction by Type, 2010–24

Exhibit 5-2. Bohai (Huludao) Shipyard Military Output, 2006–30

Exhibit 5-3. Wuchang (Wuhan) Shipyard Military Output, 2006–30

Exhibit 5-4. Jiangnan (Shanghai) Shipyard Military Output, 2006–30

Exhibit 5-5. Hudong (Shanghai) Shipyard Military Output, 2006–30

Exhibit 5-6. Huangpu Shipyard Military Output, 2006–30

Exhibit 6-1. Configuration and Growth of China’s Huludao Shipyard

Exhibit 7-1. China’s White-Listed Shipyards

Exhibit 8-1. Types of GJBs (Guojia Junyong Biaozhun, PRC National Military Standards)

Exhibit 8-2. Electromagnetic Compatibility—GJBs and MIL-STDs

Exhibit 8-3. GJB 4000-2000 Subject Areas

Exhibit 9-1. China’s IDAR Technology Innovation Process

Exhibit 9-2. First Five Stages in Military Shipbuilding Research and Development Process

Exhibit 9-3. Primary Organizations Involved in China’s Military Shipbuilding

Exhibit 10-1. Experts’ Assessment of China Capability Gap versus Class Leader

Exhibit 11-1. Key Shipbuilding Organizations Specializing in Shipboard Electronics

Exhibit 14-1. PLAN—Platform Inventory in 2015

Exhibit 14-2. PLAN 2030—Forecast Platform Inventory

Exhibit 15-1. Far Seas Navies’ Major Ships, circa 2020

Exhibit 15-2. Major Far Seas Ships, PLAN vs. U.S. Navy, circa 2020

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

On behalf of the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI), the editor thanks the Naval War College (NWC) Foundation for its important contributions in support of CMSI’s 2015 annual conference and this resulting volume. The foundation’s generosity has long played a crucial role in ensuring that such events and the publications that flow from them are of the highest caliber, and this past year has offered a particularly important example of that invaluable partnership.

As with all CMSI events and conference volumes, countless individuals have made vital contributions. While it is not possible to list them individually, the editor extends his sincere gratitude to all concerned. The support of the leadership of NWC, and of the U.S. Navy more broadly, has been crucial to our efforts. Finally, the Naval Institute Press is to be commended for its professionalism and dedication to the Studies in Chinese Maritime Development series in which this sixth volume appears. That series is the product of nearly a decade of constructive collaboration between two vital historic centers of American thinking on sea power: Annapolis and Newport.

Andrew Sven Erickson

Newport, Rhode Island

December 2016

***

INTRODUCTION TO “STUDIES IN CHINESE MARITIME DEVELOPMENT” SERIES

Andrew S. Erickson, editor

Powered by the world’s second largest economy and defense budget, China is going to sea with a scale and sophistication that no continental power ever before sustained in the modern era. Its three sea forces are all leaders in their own right: the world’s second-largest blue water navy, the world’s largest blue water coast guard, and the world’s largest (and virtually only) maritime militia.

While paramount leader Xi Jinping is working to transform his nation further into a “great maritime power,” at a minimum today’s Middle Kingdom is already a hybrid land-sea power. Amid European decline and American fiscal and strategic challenges, this historic transformation has the potential to end six centuries of largely Western dominance of the world’s oceans. To properly inform its strategy and policy, the U.S. Navy and nation must understand this momentous sea change.

Since its establishment in 2006 the China Maritime Studies Institute has been conducting research and holding conferences covering the broad waterfront of Chinese oceanic efforts in order to advise U.S. Navy leadership and support the Naval War College in its core mission area of helping to define the future Navy. The Studies in Chinese Maritime Development series assembles the resulting proceedings into edited volumes focusing on specific topics of importance to further understand the dynamics of these changes.

Previous Titles in the Series

China’s Future Nuclear Submarine Force

China’s Energy Strategy: The Impact on Beijing’s Maritime Policies

China Goes to Sea: Maritime Transformation in Comparative Historical Perspective

China, the United States and 21st-Century Sea Power: Defining a Maritime Security Partnership

Chinese Aerospace Power: Evolving Maritime Roles

RELATED READING

Andrew S. Erickson, “Chinese Shipbuilding and Seapower: Full Steam Ahead, Destination Uncharted,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 14 January 2019.

- Reprinted as “Chinese Shipbuilding and Seapower: Full Steam Ahead,” The Maritime Executive, 18 January 2019.

- Reprinted as “Chinese Seapower: Full Steam Ahead, Destination Uncharted,” RealClearDefense, 25 January 2019.

- Selected as one of five 2018-19 top-vote-receiving Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) articles from pool chosen by the think tank’s leadership, 9 July 2019.

In recent years, China has been building ships rapidly across the waterfront. Chinese sources liken this to “dumping dumplings into soup broth.” Now, Beijing is really getting its ships together in both quantity and quality. The world’s largest commercial shipbuilder, it also constructs increasingly sophisticated models of all types of naval ships and weapons systems. What made this possible, and what does it mean?

History and Drivers

China’s shipbuilding industry enjoyed early and inherent advantages that its aircraft industry, for example, notably lacked. Unlike most other sectors, its infrastructure could not be physically relocated far inland as part of Mao’s disastrously inefficient Third Front campaign. When Deng began reforms at the end of the 1970s, he prioritized shipbuilding to support the shipping industry, which helped carry foreign trade, underwriting several decades of rapid growth that has changed China, the United States, and the world significantly.

In 1982, China State Shipbuilding Corporation was formed from the Sixth Ministry of Machine Building. That same year, the Middle Kingdom made its first delivery to the international ship market. Abundant cheap labor and domestic demand buoyed Chinese shipwrights despite a ruthlessly competitive international market.

Shipbuilding’s commercial dual-use nature has long facilitated transfer and absorption of much foreign technology, standards, and design and production techniques. China’s shipbuilding industry has leapfrogged key steps, focusing less on research and more on development, thereby saving time and resources and enjoying the most rapid growth in modern history.

China’s current naval buildout dates to the mid-1990s, catalyzed and accelerated in part by a series of events that impressed its leaders with their inability to counter American military dominance. These include Operation Desert Storm in 1991, the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1995-96, and the Belgrade Embassy Bombing in 1999.

Fleet Modernization

Ships are the physical embodiment of naval strategy—the most essential element through which a nation pursues its goals at sea. China has parlayed the world’s second-largest economy and second-largest defense budget into the world’s largest ongoing comprehensive naval buildup, which has already yielded the world’s largest navy by number of ships. It is making big waves, ever-farther from its shores.

After shrinking to replace many obsolescent vessels with fewer but more modern vessels in the 1990s and 2000s, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is now improving in both numbers and sophistication. As China’s maritime strategy has evolved, so have PLAN requirements. In response to this major growth in perceived needs, the PLAN has taken on more warfare areas, with significant improvements across the board. In the 1990s, the PLAN did not have significant strike or air defense capabilities; now it does. To meet high-end, multirole requirements—such as area and point defense in layers—with more missions and greater capabilities, PLAN vessels have grown more sophisticated, and generally expanded. The larger vessels of China’s navy increasingly resemble those of its American counterpart.

Shipbuilding Strengths

Regarding Chinese shipbuilding advantages, it is difficult to obtain specific data. Numbers related to budgeting and process efficiency in China’s relatively opaque defense industry unfortunately remain very difficult to investigate precisely using open sources. The official statistics Beijing releases still do not even include a reliable breakdown for China’s service budgets—such as that of the PLAN—within the overall official PLA budget (itself highly controversial). Because of the lack of precise information available, estimating Chinese ship production expenses logically involves making assumptions about relative costs in comparison to those known for other countries—not an exact science.

Still, the larger dynamics are clear. China has the world’s largest shipbuilding infrastructure, and its development enjoys top-level leadership support, starting with Xi Jinping himself. Commercial production is price-capped in part by China’s relatively stable business and vendor base. It helps subsidize military production, an option closed to the United States given its paucity of commercial shipbuilding. Chinese shipbuilding is greatly facilitated by an unparalleled organizational structure for collecting and disseminating technology, and integrating it into development and production processes at an industrial scale. Moving forward, an important variable is the extent to which China can use its familiar approach of moving up the value chain and parlaying exceptional cost-competitiveness into exceptional quantity at sufficient quality.

China’s effort to exploit civil-military synergies offers both opportunities and challenges. This was vigorously debated by the contributors to the Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute(CMSI)’s Naval Institute Press volume on Chinese Naval Shipbuilding. “Not a good mix operationally—colocation and coproduction are challenging if not counterproductive” was one of the more pointed critiques. Potential civil-military incompatibilities cited include culture, security, standards, design, engineering, propulsion, construction, and timescales.

Nevertheless, dual-use construction is undeniably emphasized in many authoritative Chinese industry policies and publications, and also in the form of a central commission for integrated military and civilian development headed by none other than Xi himself. There is certainly some intermingling in practice, with the greatest manifestation visible in shipyard infrastructure. High-tech, high-value-added, and high reliability commercial shipbuilding—for example, of liquid natural gas (LNG) and liquid propane gas (LPG) tankers, very large crude carriers (VLCCs), high-capacity container ships carrying more than 10,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU), and even cruise ships—can be directly relevant to warship production in a way that building simple ships like bulk carriers is not.

Beijing’s prioritized military sector generally enjoys better funding, infrastructure, and human capital in the form of advanced personnel—such as engineers with long-term experience, as opposed to rapid turnover. The proof is in the pudding: the PLAN is “not receiving junk” from China’s shipbuilding industry but rather increasingly sophisticated, capable vessels. Its growing satisfaction with them is indicated in part by longer production runs of fewer classes.

A more specific question remains: what limitations on high-end capabilities plague Chinese-produced warships? For now, China faces substantial difficulties in fielding the largest, most sophisticated surface combatants and submarines, as well as remaining weaknesses in propulsion and electronics. These all involve complex systems-of-systems in which China’s preferred second-mover piecemeal integration of foreign and domestic technologies cannot offer a “good enough” result. China’s aircraft carrier program offers a prime example.

Deck Aviation Challenges

With regard to aircraft carrier development, China has come a long way but has still has further to go. The appeal is clear: these apex predators of the sea are also the most modularized naval system, one of the few ships that are relatively easy to upgrade over a considerable lifespan. But given difficulties inherent in improving marine and aviation propulsion, power, and launch technologies, an evolutionary “crawl, walk, run” trajectory seems likely for China’s aircraft carrier program.

This remains very much a work in progress: the PLAN is still “crawling” and not even “walking” yet. China has already shown that it can build decent carrier hulls. But deck aviation platforms are primarily a conveyance for aircraft-delivered payloads. And there is “no such thing as a free launch.” Payload delivery is essential to a fleet’s performance; so too is having infrastructure sufficient to support and sustain it. China’s first carrier, Liaoning, is designed for air defense, not strike. It offers a very modest extension of air defense: getting a Flanker-type aircraft like the J-15 beyond its unrefueled range from a land-based airfield.

The PLAN faces formidable challenges in such areas as electronics, maritime monitoring, and command; control; communications; computers; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4ISR). All are often underappreciated due to their subtlety and ubiquity of employment, but are nonetheless essential for robust deck aviation operations. They may be less amenable to China’s preferred approach of copying and emulation than are simpler structural systems. Chinese personnel are improving markedly in their training, but need to become still more proficient in the hard-to-steal “tribal knowledge” of coordinating operations and using equipment, including shipboard electronics.

With far greater launching power than Liaoning’s ski jump, catapults will enable larger aircraft and payloads, delivering the PLAN to deck aviation’s “walking” stage. Deploying heavier airborne early warning aircraft will improve situational awareness. “Running,” as China perceives it, would require a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier with an electromagnetic launch system—the latter of which the United States is still struggling to perfect.

Carrier Group Assembly

China is gradually strengthening its ability to project significant power into distant waters by increasingly fielding the components of an aircraft carrier group. Sustaining a carrier group at sea requires replenishment vessels. Protecting a carrier group requires surface combatants with robust air defenses and offensive missiles as well as nuclear-powered submarines with potent anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs).

To improve at-sea replenishment, China is currently building the Type 901 integrated supply ship, which can furnish fuel, food, and some spare parts. It remains limited in ability to transfer ordnance, its biggest difference from the U.S. Supply class. It is already more than adequate for furnishing air-to-air missiles for Liaoning. It could be refitted with more dry transfer stations to increase ordnance transfer capability—a useful indicator to watch for, which would suggest intent to emulate the United States in long-distance power projection.

As for protection and coordination, the Type 055 cruiser, if it has the command and control facilities described in open sources, will be the centerpiece of future Chinese carrier groups—able to organize other ships somewhat like a U.S. Aegis cruiser does. With 112 vertical launch cells (VLS), this large multi-mission vessel has more than double the missile capacity of any previous PLAN surface combatant. Its VLS loadouts of HHQ-9 surface-to-air missiles suggest great capacity for area air defense, its loadouts of YJ-18 ASCMs offer a significant anti-surface warfare capability, its loadouts of CJ-10 land-attack cruise missiles suggest a nascent potential for projecting power ashore, and its Yu-8 rocket-assisted torpedoes offer an antisubmarine warfare (ASW) capability.

Most navies with aircraft carriers do not protect them with robust submarines, but if China is to approach the American gold standard that it so clearly admires, and to which it apparently aspires, it will have to improve its nuclear-powered submarines, which are needed to allow for a full range of long-distance undersea operations. Even with a towed sonar array, China’s 093A nuclear-powered attack submarine remains at a significant disadvantage in being able to detect, and if necessary, attack enemy submarines while remaining undetected itself. It is still primarily an anti-surface ship platform with torpedo-tube-fireable YJ-18 ASCMs and a relatively noisy reactor, particularly in the secondary loop. Major work remains for China to project distant undersea power.

Near Seas Operational Scenarios

Closer to China’s shores, there is limited value for Chinese carrier operations, given their relative vulnerability and the potential for a highly-contested environment. But China’s shipbuilding industry has already produced a fleet of several hundred increasingly advanced warships capable of “flooding the zone” along the contested East Asian littoral, including increasingly large amphibious vessels well-suited to landing on disputed features, if they can be protected sufficiently. This is also where China’s large, conventionally-powered submarine fleet can be particularly deadly. When several hundred easy-and-cheap-to-build ships from China’s coast guard and its most advanced maritime militia units are factored in, Beijing’s numerical preponderance becomes formidable for the “home game” scenarios it cares about most. And that does not even include the land-based “anti-navy” of aircraft and missiles that backstops them. In this way, Beijing is already able to pose a formidable military-maritime challenge to the regional interests and security of the United States and its East Asian allies and partners.

Trends and Implications

China’s naval buildup is only part of an extraordinary maritime transformation—modern history’s sole example of a land power becoming a hybrid land-sea power and sustaining such an exceptional status. Underwriting this transition are a vast network of ports, shipping lines and financial systems, and—of course—increasingly advanced ships. All told, this raises the rare prospect of a top-tier non-Western sea power in peacetime, one of the few instances to occur since the Ming Dynasty developed cutting-edge nautical technologies and briefly projected unrivaled maritime power across the Indian Ocean. Now, for the first time in six centuries, commercial sea power development has flowed away from the Euro-Atlantic shipyards of the West, back toward an Asian land power that is going seaward to stay. Military sea power may be poised to follow.

Beijing is pursuing a requirements-based approach:

The PLAN’s transition from a “Near Seas” to a “Near and Far Seas” navy is dispersing its fleet over greater distances, making it more difficult to protect and support, as well as requiring enhanced logistics and facilities access.

Some of the most important and challenging requirements include:

- long endurance propulsion—especially nuclear power, the ultimate “gold standard”

- area air defenses for surface combatants and emerging carrier groups

- land-attack and strike warfare, including from deck aviation assets

- ASW

- acoustic quieting for submarines, to help them both survive being targeted in deeper blue-water environments, and search more effectively without limitation by self-generated noise

- and, finally, broad-coverage C4ISR

China has started to pursue all these objectives, but it will take years before it fully accomplishes them.

Already, however, Chinese ship-design and shipbuilding advances are increasing the PLAN’s ability to contest sea control in a widening arc of the Western Pacific. China is producing two to three surface combatants for every one the United States produces. If current trends continue, China will be able to deploy a combat fleet that in overall order of battle (meaning, hardware-specific terms) is quantitatively larger and qualitatively on par with that of the U.S. Navy by 2030.

Whether China can stay on this trajectory, given looming maintenance costs and downside risks to its economy as it faces an S-curved growth slowdown, is another question. It is a question that is linked to many other uncertainties about China’s future. China under Xi is becoming increasingly statist and militarized, thereby suggesting that naval shipbuilding will not suffer for lack of resources even as debt continues to spiral upward in state-owned enterprises. China’s very capable shipbuilding industry is closing remaining gaps with its Japanese and Korean rivals, even as Korean shipbuilders suffer unprofitability and rapidly-declining order books. However, China faces continued challenges in overcapacity and an aging workforce.

Moreover, a major mid-life maintenance bill for the overhauls of all new PLAN vessels will start coming due in the next 5-10 years. This will demand considerable resources—in money and shipyard space, with production and maintenance in potential competition. By then, China’s aging society may reorient resource allocation by stimulating “guns vs. butter,” and even “guns vs. canes” debates. The true long-term cost of sustaining top-tier sea power tends to eventually outpace economic growth by a substantial margin. For all its rapid rise at sea thus far, China is unlikely to avoid such challenging currents.

Dr. Andrew S. Erickson is a Professor of Strategy in the China Maritime Studies Institute and the recipient of the inaugural Civilian Faculty Research Excellence Award at the Naval War College. He serves on the Naval War College Review’s Editorial Board and is an Associate in Research at Harvard University’s John King Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. In 2013, while deployed in the Pacific as a Regional Security Education Program scholar aboard USS Nimitz, he delivered twenty-five hours of presentations. Erickson is the author of Chinese Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Development (Jamestown Foundation/Brookings Institution Press, 2013). He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University. Erickson blogs at www.andrewerickson.com. The views expressed here are his alone and do not represent the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

This article elaborates on a podcast in which CSIS scholar Bonnie Glaser interviewed Dr. Erickson as part of the ChinaPower Project that she directs there.

***

BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY OF VOLUME, AS WELL AS EDITOR’S FURTHER ANALYSIS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS:

Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Naval Shipbuilding Sets Sail,” The National Interest, 8 February 2017.

The United States needs to reengineer a naval shipbuilding “sweet spot.”

China has parlayed the world’s second-largest economy and second-largest defense budget into the world’s largest ongoing comprehensive naval buildup, which has already yielded the world’s second-largest navy. All that is only part of an extraordinary maritime transformation—modern history’s sole example of a land power becoming a hybrid land-sea power on a sustained basis. Underwriting this transition are a vast network of ports, shipping lines and financial systems, and increasingly advanced ships. It also raises the rare prospect of a top-tier non-Western sea power in peacetime, one of the few instances to occur since the Ming Dynasty developed cutting-edge nautical technologies and briefly projected unrivaled power across the Indian Ocean six centuries ago. These factors raise a critical question for our age: Where is China headed at sea, and to what end?

Ships are the physical embodiment of naval strategy and an essential element through which a nation achieves the ends of maritime strategy. China has three major sea forces: the navy, coast guard and maritime militia. Of them, the navy is China’s primary force beyond the near seas (such as the Yellow, East China and South China Seas) as well as the critical measure of its sophistication in shipbuilding. Yet, unlike every other major shipbuilding power, China does not reveal how many warships of each class it intends to build.

The strategic goals and guidance of the party, state and People’s Liberation Army determine Chinese naval shipbuilding choices. To rationalize ship and weapons-system design with naval strategy, two main research organizations perform analysis: the strategically focused Naval Research Institute and the technically focused Naval Armament Research Institute. This is part of a larger Weapons and Armament Development Strategy drafted by the General Armament Department and approved by the Central Military Commission. It helps inform China’s more than twenty-six thousand national standards and more than eleven thousand military standards, with the naval subset compiled in a two-thousand-plus-page volume titled “General Specifications for Naval Ships.”

For now at least, open sources do not deeply illuminate the specifics of this planning process, thereby constraining the potential for deductive analysis. Fortunately, extensive production by China’s shipbuilding industry (SBI) already offers a bonanza for inductive analysis, particularly through the interdisciplinary approach pioneered by the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. As the editor for the sixth volume in CMSI’s conference book series, “Studies in Chinese Maritime Development,” I assembled a diverse group of some of the world’s leading specialists and had them address the following questions:

- What are China’s prospects for success in key areas of naval shipbuilding?

- What are the likely results for China’s navy?

- What are the larger implications, particularly for the U.S. Navy (USN)? … … …

***

FULL-LENGTH REVIEWS

Review of Andrew S. Erickson, ed., Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: An Ambitious and Uncertain Course (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016); The Navy Magazine, Australian Navy League, 79.1 (January–March 2017).

This is an important, timely and indeed ambitious book at a pivotal moment in World history. In understanding China’s Shipbuilding and Designs one also gains a glimpse into the cultural knowledge, technologies and enduring artefacts necessary to sustain a Navy. It was no accident that the Industrial Revolution had at its core the impetus given by the need to rebuild the Royal British Navy following the Civil Wars; the 1688 Golden Takeover (by the Dutch); the financial crises of the 1690s; and, the 1707 Act of Union. Ship designs, builds and manufacturing that defined British Navy and Industry for the next 300 years.

The enduring nature of both the revolution and the Navy also shaped new means of working and organising resources (Admiralty); new financial models (based upon The Bank of England and the City of London), and significantly impacted the mass movement of peoples across the world – exacerbated by the Irish Potato famine and the Highland Clearances. An industrial revolution of this type could not therefore be sustained without impacting society and the work force (for example the Great Leap Forward that killed millions); which similarly impacted the designs and builds of ships and democratic political organisations alike. For example, the rise of the Unions; the Labour movement, and Sinn Fein (in Ireland).

This raises the fundamental questions addressed by Andrew Erickson in identifying the means by which China is seeking to become a maritime power. It is one thing to build ships – another one entirely to sustain Fleets over time, with supporting structures and organisations necessary to endure. It is here that Erickson’s final analysis is most interesting – recognising that, ‘ultimately, it is likely to be the ability to rapidly adapt to a changing war-fighting environment that will confer the most long-term advantages’. This ability to adapt is a component of the human software, as Erickson calls it, and is likely to be the critical factor. Just as Kaiser’s Germany was essentially entrapped by the Mahanian effort put into building a formidable Blue Water Navy (with aspirations in the South China Sea), so too may be China. By locking itself into current thinking, just at a moment of significant change – when the Global West moves (as we know is coming) to a new state. Strategic agility, as Erickson also argues, should be the guiding star for all naval planners. This planning, though, and its impact is wider than simply on navies alone. The question for the CCP may be ‘what organisations are coming that may augment, overthrow or replace it’? History also shows, this can often come from Navies. A threat for the West may be that over-emboldened by its Navy and facing interstitial threats at home, a weakened China may severely miscalculate. And President Xi Jinping and China, despite Admiral Harry B. Harris’s (U.S. Pacific Command) contrary views, may not be as powerful or secure as often portrayed… … …

***

Michael DeBoer; review of Andrew S. Erickson, ed., Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: An Ambitious and Uncertain Course (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016); Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 9 January 2017.

Chinese Naval Shipbuilding Capability: An Uncertain Course adds the most recent volume to Dr. Andrew Erickson’s excellent edited collections on the increase of the People’s Republic’s military, economic, and industrial power published by the Naval Institute Press. Erickson’s credentials include a professorship in strategy at the Naval War College, a research associateship at Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, and [serving as] a regular congressional witness on areas pertaining to Chinese capabilities and strategy. He is a giant in the field. The work combines seventeen articles written by thirty-two authors, among them storied names such as CRS naval analyst Ronald O’Rourke and former former Director of Intelligence and Information Operations (N2) for U.S. Pacific Fleet CAPT James Fanell (ret). The volume provides a nuanced and insightful view of a major Chinese strategic investment, its shipbuilding industry, and is required reading for anyone, academic or layman, trying to understand the associated capabilities and implications of the People’s Republic’s maritime rise.

The three hundred-forty-page tome is broken into five sections, describing the PRC’s shipbuilding industry’s foundation and resources, infrastructure, approach to naval architecture and design, remaining challenges, and a section which provides strategic conclusions and predictions for the future of American naval and maritime power. The articles are easily readable, each approximately ten to fifteen pages of crisp, synthesized content, with end notes allowing readers to further explore the author’s research, although most references are translated from Mandarin Chinese. The works also feature multiple graphs, tables, and illustrations, providing further resources for students and researchers. While each article provides fascinating insights into the past, present, and future of Chinese shipbuilding, four areas of study especially stood out as enjoyable, informative, and useful.

First, Christopher P. Carlson and Jack Bianchi’s Chapter I review of the People’s Republic’s naval and maritime history from the formation of the communist state to Xi Jinping provides a concise review of the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) strategic development. Carlson and Bianchi first review the PLAN’s operational shift from Near Coast Defense, to Near Seas Active Defense, and finally to Near Seas Defense and Far Seas Operations, as the PLAN’s resources, capabilities, and objectives adapted to match the nation’s goals. The pair provide an excellent linkage between China’s strategic situation since Mao’s victory and the requirements of PLAN platforms as the force shifted from a coastal force to a limited blue water force and finally to a force intended to defend Chinese interests on both the near and far seas. This evolution brought an increase in the complexity and technical sophistication to the Chinese military shipbuilding industry.

Second, Leigh Ann Ragland-Luce and John Costello provide insight into a major limitation of Chinese military shipbuilding: combat electronics. Ragland-Luce and Costello point out that, while PLAN hull and mechanical systems are regularly manufactured using modern industry standards such as modular construction, the PLAN remains unable to field a top-tier indigenously developed combat control system. The authors use the Jiangkai-II (054A)-class guided missile frigate, a modern warship by any standard, whose combat control system (CCS) is based upon the French TAVITAC, vice a comparable Chinese design. This potential lack of integration between the French CCS and developing Chinese weapons and sensor systems might well prove a combat handicap for PLAN forces in future conflicts. Similarly, editor Andrew Erickson with Jonathan Ray and Robert T. Forte provide an excellent dissertation on the limitations of Chinese propulsion plant designs. According to the trio, the PLAN appears proficient in coastal diesel submarine propulsion technologies. The PLAN effectively integrates Sterling Engine Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) systems into its Yuan-class diesel-electric boats (SSPs), and it leads research into safe Lithium-Ion battery storage systems, potentially increasing coastal submarine endurance. It still lags considerably in both modern integrated surface propulsion plants and nuclear powered propulsion designs.

Third, the work uses present shipbuilding capacity to extrapolate future PLAN capability and force structure. CAPT James Fanell (ret) and Scott Cheney-Peters (Founder of CIMSEC) provide a realistic warning regarding the long-term challenge of Chinese strategic depth in military shipbuilding. Ronald O’Rourke caps the work with a set of implications for the U.S. Navy if PLAN force structure continues to expand.

Fourth, the work also provides an excellent overview of the curious public-private nature of an industry. The ten-year old split of Chinese shipbuilding into competitive public-private corporations Chinese State Shipbuilding Company (CSSC) and Chinese Industrial Shipbuilding Company (CSIC), induced formidable challenges to reintegrate as demand for commercial Chinese-built shipping demand drops and the People’s Republic attempts to cut excess overhead in its public ventures. The work also appropriately conveys the confusing and byzantine structure of the Chinese military-industrial complex, broken into multiple institutes and directorates with potentially overlapping responsibilities. …

Overall, Chinese Naval Shipbuilding provides a very useful window into an area of intense Communist Party strategic investment. The work gives the reader an excellent overview of the industry as a whole, overlapped with strategic context and geopolitical implications. As discussed, the volume also provides a unique look at the industry’s challenges, including increased engineering costs, poor integration with modern combat systems, and challenges in surface ship engineering plants and nuclear propulsion technologies. Nuanced and complex, it describes both the accomplishments of an industry that now leads the world in commercial tonnage produced, but also lags behind in critical areas mastered by much smaller and less-rich nations. Erickson’s volume is a worthy addition to his series and an enjoyable read.

Read CIMSEC’s interview with editor Dr. Andrew Erickson on this book here.

***

INTERVIEWS

Shannon Tiezzi, “Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: Measuring the Waves—An interview with Andrew S. Erickson,” The Diplomat, 25 April 2017.

After a six-century hiatus, sea power development may once again find its center of gravity in the Asia-Pacific. While the Trump Administration plans a naval buildup, China is already well into a buildup of its own. A new book from Naval Institute Press explains why Beijing is making such waves, how big they are, and how great they might become. To learn more, The Diplomat’s Editor-in-Chief Shannon Tiezzi interviewed Naval War College professor Andrew S. Erickson, the editor of Chinese Naval Shipbuilding.

Tell me about your book. I understand that it’s the sixth volume in the joint China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI)-Naval Institute Press (USNI) series, “Studies in Chinese Maritime Development.”

That’s right! It’s the product of two great historic centers of American thinking on seapower: Newport and Annapolis.

Here’s why we collaborated on this book: China’s maritime transformation is already making major waves. It’s not just one of this century’s most significant events, but part of an even greater sea change: for the first time in 600 years, sea power development may be flowing away from the Euro-Atlantic shipyards of the West. For the first time in nearly two millennia, it may be flowing toward a longtime land power that’s going seaward to stay. As Chinese mandarins and mariners chart their country’s new course, specificity is often scarce — yet ships are no abstraction. For all these reasons, it’s never been more important to assess what ships China can supply its navy and other sea forces with, today and tomorrow. From a Newport-based perspective, in particular, this raises three pressing questions: What are China’s prospects for success in key areas of naval shipbuilding? What are the likely results for China’s navy? What does this mean for the U.S. Navy (USN)?

To answer these questions, we assembled some of the world’s leading experts and linguistic analysts. Our contributors include sailors, scholars, and industry experts. They’ve commanded ships at sea, led naval programs ashore, seasoned intelligence analysts, toured Chinese vessels, invested in Chinese shipyards, and briefed leaders facing urgent national security decisions. China continues to lack transparency in important respects, but much has been revealed through such interdisciplinary analysis — a hallmark of CMSI efforts.

Accordingly, our contributors assess the impact of Beijing’s substantial economic resources, growing maritime focus, and uneven but improving defense industrial base on its prospects for success in key areas of naval shipbuilding; the likely results for China’s sea forces, particularly its navy; and the implications for the USN.

We do so in five thematic parts:

- The first section surveys the foundation and resources for China’s naval shipbuilding, providing an overall framework.

- The next three sections examine specialized subsets of China’s shipbuilding program: infrastructure, architecture and design, and impediments.

- Section two, on shipyard infrastructure, surveys China’s vessel construction facilities and their production and evolution.

- The third section covers Chinese naval architecture and design, from standards to production processes to civil-military disparities, and Beijing’s prospects for narrowing them through its preferred centralized approach.

- Section four addresses remaining shipbuilding challenges for China.

- The final section returns to the strategic level by offering alternative futures, conclusions, and takeaways.

How close is China’s navy to challenging America’s as the world’s largest (in numbers) and strongest (in capabilities)?

China’s shipbuilding industry is poised to make the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) the world’s second largest navy by 2020, and — if current trends continue — a combat fleet that in overall order of battle (i.e., hardware-specific terms) is quantitatively and even perhaps qualitatively on a par with that of the USN by 2030.

By imbibing lessons learned and underwritten by others, Beijing benefits from a second-mover advantage. Purchasing foreign naval systems, pushing licensed production well past contractual limits, and even engaging in cyber theft has allowed China to focus less on research, and more on development. It has “leap frogged” some naval development, engineering, and production steps to achieve tremendous cost and time savings by leveraging work done by the United States and other countries. We explore this process of “imitative innovation” in depth. At the same time, the PLAN’s growing fleet will incur a rising maintenance bill as the new ship classes mature, following the time-worn naval adage that “you buy a boat three times” as the costs of vessel ownership and upkeep surpass the outlays for the initial purchase. …

***

Sally DeBoer, President, Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), “A Conversation with Dr. Andrew Erickson on Chinese Naval Shipbuilding,” 19 December 2016.

On the occasion of the publication of his newest book, Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: An Ambitious and Uncertain Course, the 6th volume in the USNI Press’ Studies in Chinese Maritime Development Series, CIMSEC spoke with editor and author Dr. Andrew Erickson, Professor of Strategy in, and a core founding member of, the U.S. Naval War College (NWC)’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI).

SD: Dr. Erickson, thank you so much for joining CIMSEC to talk about your new book, Chinese Naval Shipbuilding. This topic is of great interest to our readership, and your book is perhaps the most comprehensive, detailed, and up-to-date look at the growth, and specifically the methods and implications of that growth, of the People’s Liberation Army – Navy (PLAN). To begin, can you tell us a bit about yourself and what brought you to this topic?

AE: In twelve years in Newport, I’ve been privileged to help establish the U.S. Navy (USN)’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) and turn it into a recognized research center that has inspired both the Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute and the Naval War College’s Russia Maritime Studies Institute. In my own analysis, I’ve explored new areas of Chinese-language methodology and worked to develop new concepts and findings that can enhance U.S. understanding of, and policies toward, China.

With the support of CMSI’s current director, Professor Peter Dutton, I have recently applied our Institute’s resources to examining the industrial underpinnings of one of this century’s most significant events, China’s maritime transformation. Strong strategic demand signals and guidance from civilian authorities, combined with solid shipbuilding industry capability, are already driving rapid progress. Yet China’s course and its implications, including at sea, remain highly uncertain—triggering intense speculation and concern from many quarters and in many directions. Moreover, despite these important dynamics, no book had previously focused on this topic and addressed it from a USN perspective. Like the CMSI conference on which it is based, the resulting volume in our series with the Naval Institute Press, “Studies in Chinese Maritime Development,” focuses some of the world’s leading experts and analysts on addressing several crucial questions of paramount importance to the USN and senior decision makers: To what extent, and to what end, is China going to sea? What are China’s prospects for success in key areas of naval shipbuilding? What are the likely results for China’s navy? What are the implications for the USN?

SD: Part One of the text deals with Foundations and Resources, meaning the foundations of China’s shipbuilding industry and the assets supporting its efforts. The first chapter, in fact, explores how the evolution of China’s maritime strategy impacts future ship design. From your perspective, what primary mission needs will drive Chinese shipbuilding over the next quarter century, and what effect will that have on the fleet?

AE: China’s primary focus remains upholding its interests and promoting its disputed claims in the “Near Seas”—which encompass the waters within the First Island Chain (the Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea)—as well as defending their immediate approaches. It also has a growing desire to increase operational capability in the “Far Seas”—beyond the First Island Chain. This is essentially about being able to project power. First, to improve the defense of China itself; and second, to defend China’s growing economic interests abroad, which largely depend on unfettered access to the sea.

However, operating at greater distances from China places greater demands on its naval platforms as it becomes far more difficult to support surface ships, submarines, and aircraft the farther they move away from the coast. If we look at the desired capabilities for Far Seas operations, then we should expect improvements in surface combatant area anti-air defenses, anti-submarine warfare, and strike warfare. Chinese deck aviation components are largely air defense assets right now. A robust land attack/strike capability is the next step. Improvements in acoustic quieting are absolutely necessary if PLAN submarines are to survive being targeted in deeper, blue water environments. Shifts toward anti-submarine and strike warfare will represent the biggest likely changes in combat capabilities. Also required: a significant improvement in Chinese logistics support to sustain deployed platforms. The PLAN has started actively pursuing these goals, but it will take some time before it masters them. …

EDITOR’S PERSONAL SUMMARY OF THE KEY FINDINGS FROM THE CONFERENCE ON WHICH THIS FURTHER-DEVELOPED AND JUST-UPDATED VOLUME IS BASED:

Andrew S. Erickson, “Steaming Ahead, Course Uncertain: China’s Military Shipbuilding Industry,” The National Interest, 19 May 2016.

“In recent years, China’s navy has been launching new ships like dumping dumplings [into soup broth].” This phrase has circulated widely via Chinese media sources and websites. Accompanying it are ever-more-impressive analyses and photographs, most recently of China’s first indigenous aircraft carrier, now under construction in Dalian. The driving force behind all this, China’s shipbuilding industry, has grown more rapidly than any other in modern history.

One of this century’s most significant events, China’s maritime transformation is already making waves. Still, however, China’s course and its implications—including at sea—remain highly uncertain, triggering intense speculation and concern from many quarters and in many directions. Beijing has largely met its goal of becoming the world’s largest shipbuilder. Yet progress remains uneven, with military shipbuilding leading overall but with significant weakness in propulsion and electronics for military and civilian applications alike. It has thus never been more important to assess what quality and quantity of ships is China able to supply its navy and other maritime forces with, today and in the future. Somewhat surprisingly, however, there has been insufficient attention to this topic, particularly from a U.S. Navy (USN) perspective.

To bridge that gap, a diverse group of some of the world’s leading sailors, scholars, analysts, industry experts, and other professionals convened at the Naval War College (NWC) on 19-20 May 2015 for a two-day conference on “China’s Naval Shipbuilding: Progress and Challenges.” Hosted by NWC’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI), it was cosponsored with the U.S. Naval Institute (USNI), which will publish the resulting edited volume early next year.

CMSI was formally established on 1 October 2006. Its research and analysis of China’s maritime capabilities helps to inform USN leadership and supports NWC in its core mission area of helping to define the future Navy. The annual CMSI conference is a principal function of the Institute, supporting focused examination of the full range of Chinese maritime developments.

This conference, the tenth in a series, focused on a topic of great interest to USN leaders: China’s naval shipbuilding industry. “Shipbuilding” includes construction of new vessels, the repair and modification of existing ones, and the production and repair of shipboard and associated equipment. Paper presenters, discussants, and other attendees analyzed China’s shipbuilding capacity in order to deepen understanding of the relative trajectories of Chinese and American naval shipbuilding and possible corresponding challenges and responses for the USN. The overarching questions, of paramount importance to USN and other observers, included:

– What are China’s prospects for success in key areas of naval shipbuilding?

– What are the likely results for China’s navy?

– What are the implications for the USN?

As the self-designated target yearfor China to become the world’s largest shipbuilder, 2015 was a particularly appropriate time for the conference. In some respects, China has already accomplished its goal, yet major problems and uncertainties remain as we look forward over the next fifteen years through 2030—the rough timeframe for this conference’s analysis.

This is an exciting time to observe the fruits of Chinese naval shipbuilding, and perhaps a significant inflection point. As part of its unprecedented maritime emphasis overall, China’s 2015 Defense White Paper states: “the traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned… great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests.” The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI)’s 2015 report concludes: “China is only in the middle of its military modernization, with continued improvements planned over the following decades. As we view the past 20 years of [People’s Liberation Army Navy/PLAN] modernization, the results have been impressive, but at its core the force has remained essentially the same—a force built around destroyers, frigates and conventional submarines. As we look ahead to the coming decade, the introduction of aircraft carriers, ballistic missile submarines, and potentially a large-deck amphibious ship will fundamentally alter how the PLA(N) operates and is viewed by the world.”