U.S. Department of Defense Annual Reports to Congress on China’s Military Power—2002-19—Download Complete Set + Read Highlights Here

Since I couldn’t find a single-source location on the Internet, and the Pentagon has deactivated some of the previous links, I decided to make my own. Now you can download cached PDFs of all the Department of Defense’s China reports directly by year!

2018 + Accompanying Fact Sheet

Additionally, here are some highlights from, and analysis of, several of the most recent reports:

2018

Andrew S. Erickson, “Exposed: Pentagon Report Spotlights China’s Maritime Militia,” The National Interest, 20 August 2018.

For countering China’s shadowy Third Sea Force—the Maritime Militia—sunlight is the best disinfectant and demonstrated awareness is an important element of deterrence. This year’s Department of Defense report to Congress offers both.

Finally, some good news from Washington! Last Thursday the Pentagon released its annual report to Congress on military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The single most important revelation alone justifies the 145-page report’s $108,000 cost many times over. Even more than when last year’s report mentioned it for the first time, the U.S. government has officially deployed the formidable credibility of the world’s foremost intelligence collection and analytical capabilities to shine a spotlight and expose the shadowy People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). Previously, in beltway bureaucracy, the PAFMM was mentioned by Ronald O’Rourke in his Congressional Research Service report and by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which rightly recommended that the Department of Defense address this vital subject. Indeed, there is no substitute for the Pentagon’s credibility in this regard. By releasing these important facts officially and authoritatively, the 2018 report has performed a signal service.

Beijing uses the PAFMM to advance its disputed sovereignty claims across the South and East China Seas. The Maritime Militia, China’s third sea force, often operates in concert with China’s first sea force (the Navy) and second sea force (the Coast Guard). In an unprecedented accompanying Fact Sheet, the Pentagon’s 2018 report offers a recent example: “China . . . is willing to employ coercive measures to advance its interests and mitigate other countries’ opposition. . . . In August 2017, China conducted a coordinated PLA Navy (PLAN), China Coast Guard (CCG), and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia patrol around Thitu Island and planted a flag on Sandy Cay, a sandbar within 12 nautical miles of Subi Reef and Thitu Island, possibly in response to the Philippines’ reported plans to upgrade its runway on Thitu Island.”

Each PRC sea service is the maritime division of one of China’s three armed services, and each is the world’s largest by number of ships. “The PLAN, CCG, and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) form the largest maritime force in the Indo-Pacific,” the report emphasizes. First, “The PLAN is the region’s largest navy, with more than 300 surface combatants, submarines, amphibious ships, patrol craft, and specialized types.” It is also the world’s largest navy numerically; as of August 17, 2018, the U.S. Navy has 282 deployable battle-force ships. Second, “Since 2010, the CCG’s fleet of large patrol ships (more than 1,000 tons) has more than doubled from approximately 60 to more than 130 ships,” the report adds, “making it by far the largest coast guard force in the world and increasing its capacity to conduct simultaneous, extended offshore operations in multiple disputed areas.” Third, Beijing has what is clearly the world’s largest and most capable maritime militia. One of the few maritime militia forces in existence today at all, it is virtually the only one charged with involvement in sovereignty disputes. Only Vietnam, one of the very last countries politically and bureaucratically similar to China, is known to have a roughly equivalent force with a roughly equivalent mission. Moreover, when it comes to forces at sea—militia or otherwise—Hanoi is simply not in the same league as Beijing and cannot compete either quantitatively or qualitatively.

Beijing’s use of the PAFMM undermines vital American and international interests in maintaining the regional status quo, including the rules and norms on which peace and prosperity depend. PAFMM forces engage in gray zone operations, at a level specifically designed to frustrate effective response by the other parties involved. One PRC source terms this PAFMM participation in “low-intensity maritime rights protection struggles”; the Pentagon’s report describes broader PAFMM and CCG “use of low-intensity coercion in maritime disputes.” “During periods of tension, official statements and state media seek to portray China as reactive,” the report explains. “China uses an opportunistically timed progression of incremental but intensifying steps to attempt to increase effective control over disputed areas and avoid escalation to military conflict.” In particular, “PAFMM units enable low-intensity coercion activities to advance territorial and maritime claims.” Because the PAFMM is virtually unique and tries to operate deceptively under the radar, it has remained publicly obscure for far too long even as it trolls with surprising success for advances in sovereignty disputes in seas along China’s contested periphery.

Fortunately, the U.S. government is well aware of the PAFMM’s predations and monitors it closely. In providing such detailed coverage of the PAFMM in its latest report, the Pentagon has strongly validated key findings from the Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute’s (CMSI) open source research project on that subject, which is now entering its fifth year. In what follows, I share CMSI’s conclusions and the related text in the report.

A component of the People’s Armed Forces, China’s PAFMM operates under a direct military chain of command to conduct state-sponsored activities. The PAFMM is locally supported, but answers to the very top of China’s military bureaucracy: Commander-in-Chief Xi Jinping himself.

Part-time PAFMM units incorporate marine industry workers (e.g., fishermen) directly into China’s armed forces. As the Pentagon explains, “The PAFMM is a subset of China’s national militia, an armed reserve force of civilians available for mobilization. . . . Militia units organize around towns, villages, urban sub-districts, and enterprises, and vary widely in composition and mission.” While retaining day jobs, personnel (together with their ships) that meet the standards for induction into the PAFMM are organized and trained within the militia—as well as, in many cases, by China’s Navy—and activated on demand. As part of such efforts, “A large number of PAFMM vessels train with and assist the PLAN and CCG in tasks such as safeguarding maritime claims, surveillance and reconnaissance, fishery protection, logistics support, and search and rescue.” To further support and encourage PAFMM efforts, “The government subsidizes various local and provincial commercial organizations to operate militia vessels to perform ‘official’ missions on an ad hoc basis outside of their regular civilian commercial activities.”

Since 2015, starting in Sansha City in the Paracel Islands, China has been developing a new full-time PAFMM contingent: more professionalized, militarized, well-paid units including military recruits, crewing purpose-built vessels with mast-mounted water cannons for spraying and reinforced hulls for ramming. “In the past, the PAFMM rented fishing vessels from companies or individual fishermen, but China has built a state-owned fishing fleet for at least part of its maritime militia force in the South China Sea,” the Pentagon expounds. “The Hainan provincial government, adjacent to the South China Sea”—whose important role in PAFMM development my colleague Conor M. Kennedy and I explain here, here, and here—“ordered the building of 84 large militia fishing vessels with reinforced hulls and ammunition storage, which the militia received by the end of 2016, along with extensive subsidies to encourage frequent operations in the Spratly Islands.” The report elaborates: “This particular PAFMM unit is also China’s most professional, paid salaries independent of any clear commercial fishing responsibilities, and recruited from recently separated veterans.” Lacking fishing responsibilities, personnel train for peacetime and wartime contingencies, including with light arms, and deploy regularly to disputed South China Sea features even during fishing moratoriums.

China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), Coast Guard, and Government Maritime Forces 2018 Recognition and Identification Guide (Suitland, MD: Office of Naval Intelligence, July 2018).

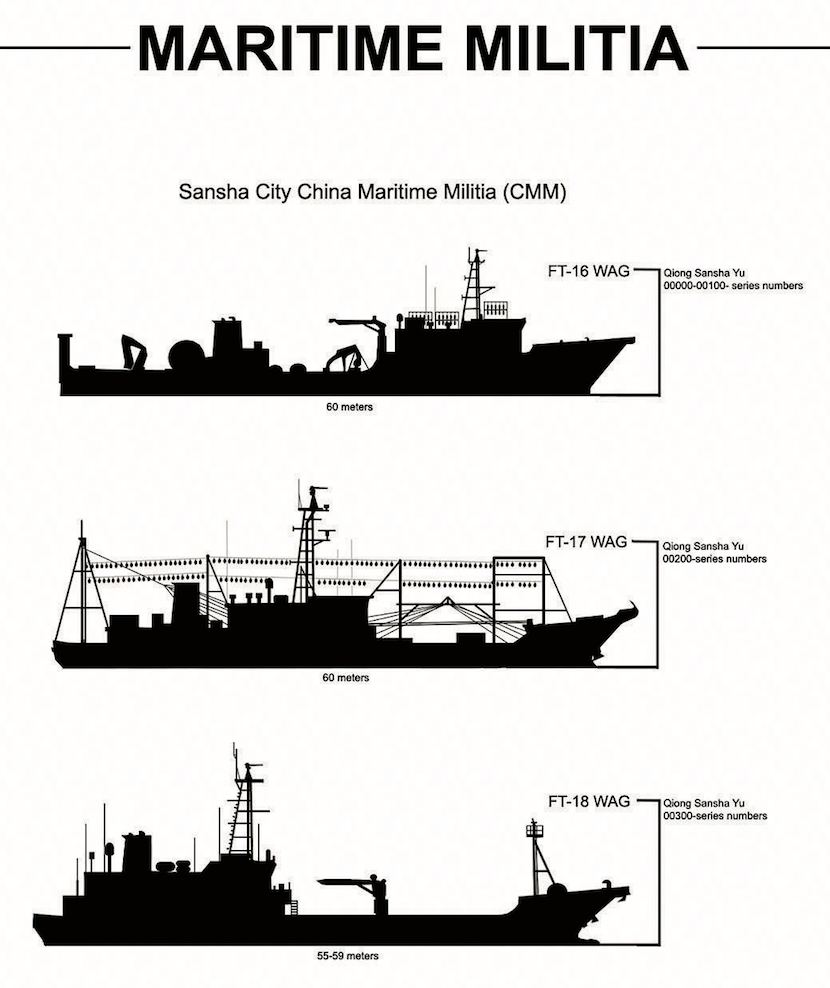

(EXCERPT SHOWING THREE TYPES OF SANSHA CITY MARITIME MILITIA VESSELS)

In July, the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence issued the China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), Coast Guard, and Government Maritime Forces 2018 Recognition and Identification Guide. The excerpt above shows three different types of purpose-built PAFMM vessels operated by the Sansha City Maritime Militia.

PAFMM units have participated in manifold international sea incidents. As the Pentagon attests, “The militia has played significant roles in a number of military campaigns and coercive incidents over the years, including the 2009 harassment of the USNS IMPECCABLE conducting normal operations, the 2012 Scarborough Reef standoff, the 2014 Haiyang Shiyou-981 oil-rig standoff, and a large surge of ships in waters near the Senkakus in 2016.”

The last of these is particularly significant, since it is now one of several publicly documented examples of PAFMM involvement in international incidents in the East China Sea, but had not been conclusively confirmed by previously known open sources. Other examples, as documented in CMSI research to date, include swarming into the Senkaku Islands’ territorial sea in 1978 and harassment of USNS Howard O. Lorenzen in 2014. So, while the vast majority of publicly revealed incidents involving PAFMM forces have occurred throughout the South China Sea, the PAFMM also clearly operates and has been empowered to engage in provocative activities in the East China Sea as well. Any PRC attempts to deny that the PAFMM operates in the East China Sea, including in disruptively close proximity to foreign forces, may therefore be easily disproven. The Pentagon is clear: “The PAFMM . . . is active in the South and East China Seas.”

This conclusive exposure of PAFMM activities in the East China Sea should be an important reminder to policy-makers in Tokyo and Washington alike that Beijing is certain to continue to wield its third sea force as a tool of choice to probe and apply pressure vis-à-vis the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands. These pinnacle-shaped features are the peak Sino-Japanese geographical flashpoint. As the current and previous U.S. administrations have affirmed explicitly, the Senkakus are covered under Article 5 of the U.S.-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, which states, in part: “Each Party recognizes that an armed attack against either Party in the territories under the administration of Japan would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional provisions and processes.”

American and Japanese analysts and decision-makers should therefore redouble their efforts to share information and develop and implement potential countermeasures concerning the PAFMM. Here, as elsewhere, sunlight is the best disinfectant and demonstrated awareness is an important element of deterrence. Just as the Pentagon’s 2017 report was the first iteration to mention the PAFMM and this latest 2018 edition builds strongly on that foundation, it is to be hoped that the Japan Ministry of Defense’s Defense of Japan 2017 report—which likewise mentioned the PAFMM for the first time, albeit without explicit in-text reference to the East China Sea—will be followed with a 2018 edition offering far more robust PAFMM coverage, including detailed consideration of extant and potential future activities in the East China Sea.

As mentioned above, the Pentagon’s latest report also stresses PAFMM involvement in the layered cabbage-style envelopment of the Philippines-claimed Sandy Cay shoal near Thitu Island in the South China Sea, although it does not mention the fact—confirmed by commercially available AIS data concerning ship movements—that China has sustained a presence of at least two PAFMM vessels around Sandy Cay since August 2017. As the Pentagon emphasizes, the “PLAN, CCG, and PAFMM sometimes conduct coordinated patrols.” Inter-service cooperation applies in peace and war: “In conflict, China may also employ China Coast Guard and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia ships to support military operations.”

“In the South China Sea,” the report emphasizes, “the PAFMM plays a major role in coercive activities to achieve China’s political goals without fighting, part of broader PRC military doctrine stating confrontational operations short of war can be an effective means of accomplishing political objectives.” Other CMSI-documented examples of international incidents involving the PAFMM there that the report does not mention explicitly include direct participation in China’s 1974 seizure of the Western Paracel Islands from Vietnam; involvement in the occupation and development of Mischief Reef resulting in a 1995 incident with the Philippines; harassment of various Vietnamese government/survey vessels, including the Bin Minh and Viking; participation in the 2014 blockade of Second Thomas Shoal; and engagement in the 2015 maneuvers around USS Lassen.

In conclusion, the Pentagon deserves great credit for employing the full force of its tremendous analytical capabilities and official authority to shine a bright, inescapable spotlight on the PAFMM’s true nature and activities. There is no plausible deniability: the PAFMM is a state-organized, -developed, and -controlled force operating under a direct military chain of command to conduct PRC state-sponsored activities. Publicly revealing the PAFMM’s true nature and activities is an important step in deterring its future use. But far more is needed to counter the pernicious challenge of Beijing’s shadowy but fully knowable third sea force. As the Pentagon’s valuable new report emphasizes, “China continues to exercise low-intensity coercion to advance its claims in the East and South China Seas.”

Dr. Andrew S. Erickson is a professor of strategy in the U.S. Naval War College (NWC)’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) and an Associate in Research at Harvard University’s John King Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. Since 2014, he and his colleague Conor M. Kennedy have been conducting and publishing in-depth research on the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) and briefing key U.S. and allied decision-makers on the subject. In 2017 Erickson received NWC’s inaugural Civilian Faculty Research Excellence Award, in part for his pioneering contributions in this area.

Image: China’s People Liberation Army (Navy) sailors from the honour guard march during a welcoming ceremony for Fiji’s Prime Minister Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama outside the Great Hall of the People, in Beijing, July 16, 2015. REUTERS/Jason Lee

2017

Andrew S. Erickson, “New Pentagon China Report Highlights the Rise of Beijing’s Maritime Militia,” The National Interest, 7 June 2017.

Pentagon experts have finally keyed in on one of the most important aspects of China’s strategy to dominate the waterways of the Asia-Pacific.

Issued yesterday, the Pentagon’s annual report to Congress on China’s military and security developments contains a typically vast array of data, some publicly specified or confirmed for the first time. Among its 106 pages—arguably the most significant development is its unprecedented coverage of China’s maritime militia—the first official U.S. government assessment to call it out in public. This is a long overdue and welcome breakthrough: the shadowy but knowable force’s vanguard units are literally on the front lines of Beijing’s efforts to overpower its neighbors and advance its control over the South China Sea.

Together with the world’s largest Coast Guard, and with China’s Navy backstopping in an “overwatch” capacity, China’s maritime militia plays a central role in maritime activities designed to overwhelm or coerce an opponent through activities cannot be easily countered without escalating to war. The report terms this approach “low-intensity coercion in maritime disputes.” Leading elements of China’s maritime militia have already played frontline roles in manifold Chinese incidents and skirmishes with foreign mariners throughout the South China Sea. Such international-sea incidents of significant concern to the United States and its regional allies and partners include multiple contributions to furthering China’s sovereignty claims in the South China Sea.

China maritime-militia forces played a central role in the 1974 battle in which China seized the western Paracel Islands from Vietnam. More recently, as the report documents, they “played significant roles in . . . the 2011 harassment of Vietnamese survey vessels.” They harassed USNS Impeccable in international waters in 2009. They helped trigger the 2012 incident in which they ultimately supported other Chinese forces in seizing Scarborough Shoal from the Philippines. They engaged in reconnaissance and sovereignty patrols during China’s February 2014 blockade of Philippine resupply of Second Thomas Shoal. They played the frontline role in the 2014 repulsion of Vietnamese vessels from disputed waters surrounding China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s HYSY-981 oil rig.

The militia is a key component of China’s armed forces and its maritime subcomponent is the Third Sea Force of China. China’s maritime militia is a set of marine industry workers (typically fishermen) and their vessels trained, equipped, organized and commanded directly by the local military commands of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). These units typically answer to the PLA chain of command, and are certain to do so when activated for international-sea incidents pre-planned by Beijing. While most militiamen have civilian jobs, new units are emerging that appear to employ elite forces full-time as militarized professionals. Directed participation by China maritime-militia forces in international-sea incidents or provocations occurs under the PLA chain of command, and sometimes also under the temporary command of the Chinese maritime law-enforcement agencies.

Here’s why the Pentagon’s publicizing of China’s maritime-militia matters: it is strongest—and most effective—when it can lurk in the shadows. But the Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute’s two-and-a-half-year study—and more than twenty articles, papers and briefings—reveals that there is more than enough open-source information available to expose China’s maritime militia for what it is: a state-organized, state-developed and state-controlled force operating under a direct military chain of command to conduct Chinese state-sponsored activities.

By revealing the maritime militia’s true nature and “calling it out” in public, the U.S. government can remove the force’s plausible deniability, reduce its room for maneuver, and reduce the chances that China’s leaders will employ it dangerously in future encounters with American and allied vessels at sea. The very few previous U.S. government-related statements were not top-level official assessments, and hence did not have the full force and influence of the U.S. government behind them. China’s maritime militia was mentioned by Adm. Scott Swift, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet; by Ronald O’Rourke in his Congressional Research Service report on Chinese maritime disputes; and by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which rightly recommended that the Department of Defense address this vital subject. But the Pentagon’s new report is the first official top-level assessment by the U.S. government to cover China’s maritime militia. It is extremely encouraging that the U.S. government has finally brought to bear the full force of its authority and its tremendous analytical capabilities to address this vital issue.

Unique Insights

Beyond its maritime-militia coverage, the report offers a treasure trove of other insights. Some areas, particularly broader strategic points and basic force-structure elements, are well known to PLA analysts outside the U.S. government but are conveniently compiled in a go-to source for many in Washington not normally focused on the subject. A number of specific points, however, are difficult—if not impossible—to corroborate or even learn through open sources. The report contains too many insights to enumerate them all here, and is best read in full—or at least skimmed directly. The following surveys some of the most important and interesting highlights from both categories. … … …

2016

Andrew S. Erickson, “How Good Are They? The Latest Insights Into China’s Military Tech,” War on the Rocks, 18 May 2016.

It’s that time of year again, and the end of an era. On Friday, the Obama Administration released the last annual Pentagon China report under its watch. Working the China military observers’ graveyard shift this weekend, I published analyses of the report’s overall content, and its key omissions — namely, any mention whatsoever of China’s maritime militia of “little blue men” trolling for territorial claims. Here, I’ll focus on the report’s greatest comparative advantage: insights concerning Beijing’s military technology and its applications that no other public source offers with such official backing or reliable details.

Defense Industrial Dynamics

The Pentagon’s report offers extensive coverage of China’s defense-industrial sector, including key policies and trends. Beijing clearly seeks a comprehensive indigenous defense industrial base, with strong commercial underpinnings. To that end, it is launching its third major round of post-Cold War reforms. Informed by extensive policy documents and a hierarchy of priority subjects, Beijing is funding extensive research, development, and acquisition throughout its sprawling defense industry and related organizations. Emphases include the widespread Chinese approach of civil-military integration and acquiring foreign technology by any means necessary — including extensive cyber and human espionage — while absorbing it and developing indigenous technology and systems in parallel. Characteristic of President Xi Jinping’s structural reform efforts more generally, a new high-level advisory body will oversee these efforts: the Strategic Committee of Science, Technology, and Industry Development for National Defense. One indication of progress: $15 billion in arms export agreements signed between 2010 and 2014.

This systematic explication enhances the credibility and utility of the 145-page report. But what most of its most avid consumers really want to know is: How good is the military hardware that China can produce? And how do performance parameters and quality vary by type of weapon system? It is in the totality of such information that the report really shines.

However, in meeting its obligations to Congress, and, by extension, the public, the Pentagon’s annual report had to address a wide range of disparate issues concerning Chinese military and security development. It had to do so in a format largely shaped by its previous 14 iterations. Allow me, therefore, to summarize and reconfigure its key findings to best address these pressing questions. I have worked here to distill insights into just how good various types of Chinese military hardware have become. …

Andrew S. Erickson, “Pentagon Report Aims to Lay Out Chinese Military Goals,” China Real Time Report (中国实时报), Wall Street Journal, 15 May 2016.

With things heating up in the South China Sea and across the Taiwan Strait, Washington just attempted to shine some badly needed light on Beijing’s military efforts.

On Friday, the Pentagon released its 15th annual report to Congress on Chinese military and security development, its last under the Obama administration. “Despite China’s opacity…this report documents the kind of military that China is building,” Abraham Denmark, deputy assistant secretary of defense for East Asia, explained at the media rollout event. “We hope it contributes to the public’s understanding of the PLA.”

Indeed it does. China characteristically dismissed the report, without seeking to disprove any of its assertions. As Mr. Denmark stressed, the Pentagon publication “lets the facts speak for themselves.” He highlighted three key areas of emphasis: military maritime activities, power projection and reforms. …

Andrew S. Erickson, “The Pentagon’s 2016 China Military Report: What You Need to Know,” The National Interest, 14 May 2016.

Andrew S. Erickson, “Obama Pentagon’s Last China Report: Covers Most Bases Commendably, But Misses Maritime Militia,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 14 May 2016.

The end of an era… Friday’s Department of Defense (DoD) report to Congress on Chinese military and security developments is the last issued under the Obama Administration. Amid geopolitical uncertainty, it was a respectable final contribution. Nevertheless, it suffers from an unfortunate shortcoming. The Pentagon report rightly highlighted growing concern about Beijing’s mounting maritime coercion, but passed up a rare chance to connect it with a potent player flouting the rules of the game. China’s Maritime Militia, the irregular frontline sea force of “Little Blue Men” trolling for territorial claims, receives nary a mention. Like a trident with only one full-fledged prong, a report covering only one of China’s three major sea forces in depth—and ignoring one entirely—remains regrettably incomplete.

“China is using coercive tactics…to advance their interests in ways that are calculated to fall below the threshold of provoking conflict,” DoD’s report rightly emphasizes. Asked to elaborate on such “Gray Zone” operations in yesterday afternoon’s roll-out event at the Pentagon, Deputy Assistant Secretary of defense for East Asia Abraham M. Denmark stated that China’s coast guard and fishing vessels sometimes act in an “unprofessional” manner “in the vicinity of the military forces or fishing vessels of other countries in a way that’s designed to attempt to establish a degree of control around disputed features.” “These activities are designed to stay below the threshold of conflict,” Denmark explained, “but gradually demonstrate and assert claims that other countries dispute.”

A key official thus encapsulated one of the most important, complex security challenges facing his government and a vital region whose peacefulness and openness it underwrites. The problem: his administration’s final iteration of the report offering unparalleled authoritative public insights on Chinese security developments missed a chance to cut to the heart of the problem by addressing China’s Maritime Militia and the concept of People’s War at Sea that inspires its development.

Covering the Bases

None of this should overshadow the report’s many welcome contributions. At a hefty 145 pages, it is highly informative and will repay whatever time you can devote to it. Through detailed text, maps, and figures, it documents a rapidly developing Chinese military, commanded by leaders inspired by ambitious national goals, in the throes of the most sweeping reforms in three decades or more. In doing so, it outlines broad dimensions of strategy, organization, leadership, and events that are largely available in open source scholarship—sometimes richer, more nuanced, and more comprehensive—but rarely in one place and almost never with a leading government’s analytical seal of approval.

Those seeking a reasonable overview of Chinese military efforts need look no further than paragraph one. “Chinese leaders have characterized modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as essential to achieving great power status and what Chinese President Xi Jinping calls the ‘China Dream’ of national rejuvenation. They portray a strong military as critical to advancing Chinese interests, preventing other countries from taking steps that would damage those interests, and ensuring that China can defend itself and its sovereignty claims.” Thus motivated, “The long-term, comprehensive modernization of the armed forces of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) entered a new phase in 2015 as China unveiled sweeping organizational reforms to overhaul the entire military structure. These reforms aim to strengthen the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) control over the military, enhance the PLA’s ability to conduct joint operations, and improve its ability to fight short-duration, high-intensity regional conflicts at greater distances from the Chinese mainland.” Beijing continues to put its money where its mouth is, with China’s defense budget indisputably the world’s second largest. While acknowledging the challenges inherent in such a calculation, the Pentagon estimates Beijing’s total military-related spending in 2015 at over $180 billion. Exercises of increasing scale, jointness, complexity, and realism are part of an effort to make China’s military far more than the sum of its unevenly growing parts.

There is, as well, the obligatory government messaging. Thus readers are assured that: “While the United States builds a stronger military-to-military relationship with China, DoD will also continue to monitor and adapt to China’s evolving military strategy, doctrine, and force development, and encourage China to be more transparent about its military modernization program.” Like other public U.S. government reports, this one reveals few details of Chinese computer network operations. Nevertheless, some cyber activities directed against its sponsoring institution in 2015 “appear to be attributable directly to China’s government and military.” Clearly, the Pentagon is not amused.

As has been the case since its first iteration in 2002, however, the report’s greatest contribution lies in its provision of technical weapons specifications and other data often otherwise unavailable in publicly authoritative form.

South Sea Sitrep

Concerning recent developments in the South China Sea, the report makes a robust contribution, offering unprecedented information in user-friendly text and graphics. Beijing’s eight outposts on the seven Spratly features it occupies are detailed in pages splashed with size comparison schematics, photos and statistics before and after augmentation and fortification, and facilities diagrams.

In two years through late 2015, China added more than 3,200 acres to the aforementioned Spratly features, against the 50 acres reclaimed by the other occupants combined. Among other activities, “China excavated deep channels to improve access to its outposts, created artificial harbors, dredged natural harbors, and constructed new berthing areas to allow access for larger ships,” the report notes. “Development of the initial four features—all of which were reclaimed in 2014—has progressed to the final stages of primary infrastructure construction, and includes communication and surveillance systems, as well as logistical support facilities.” Perhaps most importantly, “China’s four South China Sea airfields ultimately “could have runways long enough to support any aircraft in China’s inventory.”

While the report ignores China’s Maritime Militia (and its even-larger land-based counterpart), it offers several important points concerning Beijing’s other major “Gray Zone” force: the China Coast Guard (CCG). This agency has acquired “more than 100” new, improved, longer-range “ocean-going patrol ships.” Already the world’s largest blue water civil maritime force, “the CCG’s total force level is expected to increase by 25 percent.” A growing proportion of its ships will be able to embark helicopters, currently a rarity in the force. In the coming decade, the CCG will have greater ability to patrol and enforce China’s claims in the Near Seas (the Yellow Sea; and especially the East and South China Seas). The Pentagon offers no details behind these important bullet points, however; for that, you’ll have to consult the extensive scholarship of my China Maritime Studies Institute colleague Ryan Martinson.

Naval News

Buoyed by a building binge, “The PLAN now possesses the largest number of vessels in Asia, with more than 300 surface ships, submarines, amphibious ships, and patrol craft.” Quality is improving even faster than quantity, with older vessels swapped for “larger, multi-mission ships equipped with advanced anti-ship, anti-air, and anti-submarine weapons and sensors.” As part of this trend toward bigger, better ships, DoD states that China has likely “begun construction of a larger Type 055 ‘destroyer’,” properly considered a heavy “guided-missile cruiser.”

Submarine force modernization remains a leading priority. By 2020, China is forecast to have “between 69 and 78 submarines.” The Pentagon deems that four Jin-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) are already “operational,” without explaining what that means in practice. It projects that during the next decade “up to five may enter service before China begins developing and fielding its next-generation SSBN, the Type 096,” bearing the follow-on JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). Also within this timeframe, “China may construct a new Type 095 nuclear-powered, guided-missile attack submarine (SSGN), which not only would improve the PLAN’s anti-surface warfare capability but might also provide it with a more clandestine land-attack option.” As for nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs), “four additional SHANG-class SSN (Type 093) will eventually join the two already in service.”

In keeping with an enduring focus on anti-surface warfare (ASUW),” China is modernizing its anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) and their over-the-horizon targeting. In a widespread example of China improving on Russian systems that it accesses, digests, and emulates, its “newest indigenous submarine-launched ASCM, the YJ-18 and its variants” will be deployed on Song– and Yuan-class conventional submarines as well as Shang-class SSNs.

Aviation Advances

Not to be eclipsed by the PLAN, the PLA Air Force (PLAAF) “is the largest air force in Asia and the third largest in the world, with more than 2,800 total aircraft (not including UAVs) and 2,100 combat aircraft (including fighters, bombers, fighter-attack and attack aircraft).” As with the PLAN, improvements in quality are prioritized over quantity. China’s air force is replacing old platforms with new ones, thereby and “rapidly closing the gap” vis-à-vis Western counterparts “across a broad spectrum of capabilities from aircraft and command-and-control (C2) to jammers, electronic warfare (EW), and datalinks.”

As “the only country other than the United States to have two concurrent stealth fighter programs,” China is developing “fifth-generation aircraft, which could enter service as early as 2018.” DoD believes this will “significantly improve China’s existing fleet of fourth-generation aircraft.”

Strongly emphasizing UAVs, the PLAAF has employed the Yilong (Pterodactyl) for disaster relief. “China is advancing its development and employment of UAVs. Last year, the Shendiao (Divine Eagle) was reported to be the PLA’s “newest high-altitude, long-endurance UAV for a variety of missions such as early warning, targeting, EW, and satellite communications.”

Rocket Force to be Reckoned With

A major beneficiary of recent reforms, the PLA Rocket Force boasts a new name and elevation to a bona fide service. Unenviably abbreviated as “PLARF,” it controls the world’s most enviably extensive inventory of sub-strategic nuclear and conventional ballistic missiles—notably including 75-100 ICBMs. In addition to constant upgrading and as part of an effort to evade missile defenses, China’s Rocket Force is “developing and testing several new classes and variants of offensive missiles, including a hypersonic glide vehicle.”

PLARF “may be enhancing peacetime readiness levels for [its] nuclear forces to ensure responsiveness.” Other nuclear highlights include the road-mobile, solid-fueled CSS-5 Mod 6 (DF-21) medium-range ballistic missile “for regional deterrence missions.” Unveiled in the September 2015 Beijing military parade, when fielded the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile may hold ground targets as far away as Guam at risk. A nuclear version, “if it shares the same guidance capabilities, would give China its first nuclear precision strike capability against theater targets.”

Space and Counter-space

Long a top-tier power in both areas, China is working hard to enhance its space systems and be able to threaten those of potential opponents. Space accomplishments for 2015 included the launch of 19 rockets bearing 45 spacecraft, including navigation, surveillance, and test satellites. The Long March (LM)-6 and the LM-11 “next generation” launchers debuted, the latter a militarily-relevant “quick response” system to orbit a small payload. A single LM-6 orbited 20 satellites, including four Xingchen femtosatellites weighing only 100 g each. Meanwhile, China’s Beidou/Compass positioning, navigation, and timing satellite network is on track to achieve global coverage by 2020.

Chinese counter-space capabilities under development include directed energy weapons, satellite jammers, and kinetic kill vehicles. The report notes multiple tests. A 2013 ballistic missile test to over 30,000 km altitude “could have been a test of technologies with a counterspace mission in geosyncronous orbit.” An antisatellite missile system tested in summer 2014 has likely enjoyed subsequent progress. As part of increasingly-complex orbital operations, China is “probably testing dual-use technologies in space that could be applied to counterspace missions.”

Counter-intervention Capabilities

The aforementioned developments are geared primarily to improving China’s prospects for furthering its outstanding Near Seas claims and deterring—and, in a worst case scenario, defeating—U.S. and allied efforts to intervene in related disputes. Additional assets with particular “keep out” applications include a “credible” integrated air defense system extending “300 nm (556 km)” from China’s coast. Designed to counter enemy aircraft and ballistic missiles, it is composed of “robust early warning, fighter aircraft, and a variety of SAM [surface-to-air missile] systems as well as point defense.” As part of this counter-intervention complex, “The PLAAF possesses one of the largest forces of advanced long-range SAM systems in the world….” Notably, “China’s airshow displays claim that new Chinese radar developments can detect stealth aircraft.”

Radiating Ripples

Meanwhile, far from China, prospects remain more modest. Among manifold Chinese interests ever-further afield, the Pentagon highlights oil imports. Currently at 60% of total supply, they are expected to reach 80% by 2035. Currently “unable to support major combat operations in South Asia,” the Middle Kingdom is nevertheless steadily making power projection progress. In an incremental step, China started building its first domestically produced aircraft carrier last year. Its “next generation of carriers will probably be capable of improved endurance and of launching more varied types of aircraft, including EW [electronic warfare], early warning, and anti-surface warfare [ASuW], thus increasing the potential striking power of a PLAN ‘carrier battle group’ in safeguarding China’s interests in areas beyond its immediate periphery.” Likely carrier missions include “patrolling economically important sea lanes, conducting naval diplomacy, regional deterrence, and [humanitarian assistance and disaster relief].” Distant submarine deployments to date, most in conjunction with anti-piracy operations, “support an apparent Chinese requirement to project power into the Indian Ocean.” “Sea-based land attack probably is an emerging requirement for the PLAN,” the report judges, predicting long-range land-attack cruise missile (LACM) development for its surface combatants as well as the aforementioned submarines. Arming new Luyang III-class destroyer with LACMs would give the PLAN “its first land-attack capability.”

China’s Indian Ocean support footprint is expanding to support missions of lower intensity. Noting both ongoing logistics and intelligence limitations and Beijing’s official acknowledgement of its first overseas facility in Djibouti, DoD forecasts that China “will probably establish several access points” in the Indian Ocean “in the next decade,” most likely “in countries with which it has a longstanding friendly relationship and similar strategic interests, such as Pakistan, and a precedent for hosting foreign militaries.” At the same time, however, “China’s overseas naval logistics aspiration may be constrained by the willingness of countries to support a PLAN presence in one of their ports.”

Bright Spots

While the Pentagon raises numerous concerns with Chinese military development, it works to emphasize more positive aspects: Chinese cooperation, agreements, and contributions. To this end, it includes lengthy lists of exchanges and appends the full text of Sino-American memoranda of understanding. Additionally, it explains, a five-day Sino-Indian military standoff along the nations’ disputed border in September 2015 gave way to a conciliatory meeting, discussion, and stand-down. Beijing also contributes increasingly to global security. Keen to avoid portrayal as a selfish superpower (PKO), China has over 3,000 personnel in UN peacekeeping operations and is “the sixth largest financial contributor to the UN PKO budget…pledging 6.66 percent of the total $8.27 billion budget for the period from July 2015 to June 2016.”

Parting Shot

With this generally substantive report, the Obama Administration is not going gently into a good night, but it leaves its successor an already-overdue task. Congress should mandate that next year’s iteration include significant coverage of China’s Maritime Militia, as well as greatly-enhanced treatment of China’s Coast Guard. Only by understanding, publicizing, and countering the negative actions of all three of Beijing’s major sea forces can Washington ensure a positive future for the South China Sea and throughout the Asia-Pacific.

A hefty report at 145 pages! Highly informative, well worth a read. It documents a rapidly developing Chinese military and paramilitary, inspired by a far-reaching “China Dream,” in the throes of ambitious reforms.

Major missed opportunity: no mention of Maritime Militia whatsoever. On that vital topic, you’re still stuck with this next-best analysis.

Key Quotations from text of report:

p. i–“In the South China Sea, China paused its land reclamation effort in the Spratly Islands in late 2015 after adding more than 3,200 acres of land to the seven features it occupies in the archipelago.”

p. 2–New 2016 Military Theaters map

p. 6–Text box on “China’s Evolving Overseas Access”:

“China most likely will seek to establish additional naval logistics hubs in countries with which it has a longstanding friendly relationship and similar strategic interests, such as Pakistan, and a precedent for hosting foreign militaries. China’s overseas naval logistics aspiration may be constrained by the willingness of countries to support a PLAN presence in one of their ports.”

p. 10–Useful South China Sea feature occupation map (China vs. other claimants)

p. 13–Important text boxes:

“China’s Use of Low-Intensity Coercion in Maritime Disputes”

“Reclamation and Construction in the South China Sea”

“China paused its two-year land reclamation effort in the Spratly Islands in late 2015 after adding over 3,200 acres of land to the seven features it occupies; other claimants reclaimed approximately 50 acres of land over the same period. As part of this effort, China excavated deep channels to improve access to its outposts, created artificial harbors, dredged natural harbors, and constructed new berthing areas to allow access for larger ships. Development of the initial four features—all of which were reclaimed in 2014—has progressed to the final stages of primary infrastructure construction, and includes communication and surveillance systems, as well as logistical support facilities.”

pp. 14-20–Interesting graphics on Spratly feature augmentation and fortification

p. 21–“China maintains approximately 3,079 personnel in ten UN PKOs, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. This number increased from 2,200 in 2014. China is also the sixth largest financial contributor to the UN PKO budget—fourth among UN Security Council members—pledging 6.66 percent of the total $8.27 billion budget for the period from July 2015 to June 2016.”

“From 2010 to 2014, China’s arms sales totaled approximately $15 billion.”

p. 22–“PLA Rocket Force (PLARF). The Rocket Force, renamed from the PLASAF late last year, operates China’s land-based nuclear and conventional missiles. It is developing and testing several new classes and variants of offensive missiles, including a hypersonic glide vehicle; forming additional missile units; upgrading older missile systems; and developing methods to counter ballistic missile defenses.”

p. 25–“The CJ-10 has a range in excess of 1500 km and offers flight profiles different from ballistic missiles that can enhance targeting options.”

“China unveiled the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) during the September 2015 parade in Beijing. When fielded, the DF-26 will be capable of conducting precision strikes against ground targets and contribute to strategic deterrence in the Asia-Pacific region. The official parade announcer also referenced a nuclear version of the DF-26, which, if it shares the same guidance capabilities, would give China its first nuclear precision strike capability against theater targets.”

“The PLAN now possesses the largest number of vessels in Asia, with more than 300 surface ships, submarines, amphibious ships, and patrol craft. China is rapidly retiring legacy combatants in favor of larger, multi-mission ships equipped with advanced anti-ship, anti-air, and anti-submarine weapons and sensors.”

p. 26–“The PLAN places a high priority on the modernization of its submarine force and currently possesses five SSNs, four nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBN), and 53 diesel-powered attack submarines (SS/SSP). By 2020, this force will likely grow to between 69 and 78 submarines.”

“In addition to the 12 KILO-class SS units acquired from Russia in the 1990s and 2000s, China has built 13 SONG-class SS (Type 039) and 13 YUAN-class SSP (Type 039A) with a total of 20 YUANs planned for production. China continues to improve its SSN force, and four additional SHANG-class SSN (Type 093) will eventually join the two already in service.”

“Over the next decade, China may construct a new Type 095 nuclear-powered, guided-missile attack submarine (SSGN), which not only would improve the PLAN’s anti-surface warfare capability but might also provide it with a more clandestine land-attack option.”

“Four JIN SSBNs are operational, and up to five may enter service before China begins developing and fielding its next-generation SSBN, the Type 096, over the coming decade. The Type 096 will reportedly be armed with a successor to the JL-2, the JL-3 SLBM.”

“China has also probably begun construction of a larger Type 055 “destroyer,” a vessel better characterized as a guided-missile cruiser (CG) than a DDG.”

“The PLAN continues to emphasize anti-surface warfare (ASUW) as its primary focus, including modernizing its advanced ASCMs and associated over-the-horizon targeting systems. Older surface combatants carry variants of the YJ-83 ASCM (65 nm, 120 km), while newer surface combatants such as the LUYANG II are fitted with the YJ-62 (120 nm, 222 km). The LUYANG III and Type 055 CG will be fitted with a variant of China’s newest ASCM, the YJ-18 (290 nm, 537 km), which is a significant step forward in China’s surface ASUW capability. Eight of China’s 12 KILOs are equipped with the SS-N-27 ASCM (120 nm, 222 km), a system China acquired from Russia. China’s newest indigenous submarine-launched ASCM, the YJ-18 and its variants, represents an improvement over the SS-N-27, and will be fielded on SONG, YUAN, and SHANG submarines. China’s previously produced submarine-launched ASCM, the YJ-82, is a version of the C-801, which has a much shorter range. The PLAN recognizes that long-range ASCMs require a robust, over-the-horizon targeting capability to realize their full potential, and China is investing in reconnaissance, surveillance, command, control, and communications systems at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels to provide high-fidelity targeting information to surface and subsurface launch platforms.”

p. 30–“The PLAAF is the largest air force in Asia and the third largest in the world, with more than 2,800 total aircraft (not including UAVs) and 2,100 combat aircraft (including fighters, bombers, fighter-attack and attack aircraft). The PLAAF is rapidly closing the gap with western air forces across a broad spectrum of capabilities from aircraft and command-and-control (C2) to jammers, electronic warfare (EW), and datalinks. The PLAAF continues to field additional fourth-generation aircraft (now about 600). Although it still operates a large number of older second- and third-generation fighters, it will probably become a majority fourth-generation force within the next several years.”

“China has been pursuing fifth-generation fighter capabilities since at least 2009 and is the only country other than the United States to have two concurrent stealth fighter programs.”

p. 31–“China is improving its airfields in the South China Sea with the availability of Woody Island Airfield in the Paracel Islands and construction of up to three new airfields in the Spratly Islands. All of these airfields could have runways long enough to support any aircraft in China’s inventory. During late-October 2015 the PLAN deployed four of its most capable air superiority fighters, the J-11B, to Woody Island.”

“The PLAAF possesses one of the largest forces of advanced long-range SAM systems in the world….”

p. 36–“As of December 2015, China launched 19 SLVs carrying 45 spacecraft, including navigation, ISR, and test/engineering satellites. Noteworthy 2015 accomplishments for China’s space program include:

- Two New Launch Vehicles: September 2015 saw the successful debut of both the Long March (LM)-6 and the LM-11 “next generation” SLVs. The LM-6 is a small liquid-fueled SLV designed to carry up to 1000 kg into low Earth orbit (LEO), and the LM-11is described as a “quick response” SLV designed to launch a small payload into LEO on short notice in the event of an emergency.

- China’s Largest Multi-Payload Launch and Smallest Satellites: The 19 September 2015 inaugural launch of the LM-6 SLV carried the largest number of satellites (20) China has ever launched on a single SLV. Most of the satellites carried onto orbit by the LM-6 were technology-demonstration satellites smaller than 100 kg. Furthermore, the four Xingchen femtosatellites launched aboard the LM-6 are the smallest Chinese spacecraft to date, weighing just 100 g each.

- Launches Begin for Beidou Global Network: China’s Beidou SATNAV constellation began the next step of its construction in 2015 with the launch of the Beidou I1-S, an inclined geosynchronous orbit (IGSO) satellite, on March 30. In 2015, China launched two more medium Earth orbit satellites and two more IGSO satellite. This phase of the project plans to extend the Beidou network beyond its current regional focus to provide global coverage by 2020.”

p. 37–“The PLA is acquiring a range of technologies to improve China’s counterspace capabilities. In addition to the development of directed energy weapons and satellite jammers, China is also developing anti-satellite capabilities and has probably made progress on the antisatellite missile system it tested in July 2014. China is employing more sophisticated satellite operations and is probably testing dual-use technologies in space that could be applied to counterspace missions.”

“In the summer of 2014, China conducted a space launch that had a similar profile to the January 2007 test. In 2013, China launched an object into space on a ballistic trajectory with a peak altitude above 30,000 km, which could have been a test of technologies with a counterspace mission in geosyncronous orbit.”

p. 38–“The PLA Rocket Force’s (PLARF) arsenal contains 75-100 ICBMs.”

p. 47–“In 2015, China imported approximately 60 percent of its oil supply, and this figure is projected to grow to 80 percent by 2035, according to International Energy Agency data. China continues to look primarily to the Persian Gulf, Africa, and Russia/Central Asia to satisfy its growing demand.”

“In 2015, approximately 83 percent of China’s oil imports transited the South China Sea and Strait of Malacca. Separate crude oil pipelines from Russia and Kazakhstan to China illustrate efforts to increase overland supply. In 2015, the Russia–China crude oil pipeline started expanding to double its capacity from 300,000 to 600,000 barrels per day (b/d) by 2016. In 2015, construction was finished on the 440,000-b/d Burma–China oil pipeline.”

“In 2015, China imported approximately 27.7 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas, 45 percent of all of its natural gas imports, from Turkmenistan by pipeline via Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. This pipeline is designed to carry 40 bcm per year with plans to expand it to 60 bcm per year. Another natural gas pipeline designed to deliver 12 bcm per year of Burmese-produced gas commenced operations in September 2013 and shipped 3 bcm of gas in 2014. This pipeline parallels the crude oil pipeline across Burma. There was no progress in 2015 on the natural gas project that China and Russia agreed to in 2014. The pipeline is expected to deliver up to 38 bcm of gas by 2035; initial flows are to start by 2018.”

p. 58–“Recent press accounts suggest China may be enhancing peacetime readiness levels for these nuclear forces to ensure responsiveness.”

“this force is complemented by road-mobile, solid-fueled CSS-5 Mod 6 (DF- 21) MRBM for regional deterrence missions.”

p. 60–“New indigenous radars, the JL-1A and JY-27A, are designed to address the ballistic missile threat, with the JL-1A advertised as capable of the precision tracking of multiple ballistic missiles. China’s SA-20 PMU2 SAMs, one of the most advanced SAM systems Russia offers for export, has the advertised capability to engage ballistic missiles with ranges of 1,000 km and speeds of 2,800 meters per second. China’s domestic CSA-9 long-range SAM system is expected to have a limited capability to provide point defense against tactical ballistic missiles with ranges up to 500 km.”

p. 61–“China has fielded CSS-5 anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) specifically designed to hold adversary aircraft carriers at risk 1,500 km off China’s coast.”

pp. 61-62: “Within 300 nm (556 km) of its coast, China has a credible IADS that relies on robust early warning, fighter aircraft, and a variety of SAM systems as well as point defense primarily designed to counter adversary long-range airborne strike platforms. China continues to develop and to market a wide array of IADSs designed to counter U.S. technology….”

“China’s airshow displays claim that new Chinese radar developments can detect stealth aircraft.”

p. 62–“fifth-generation aircraft, which could enter service as early as 2018, will significantly improve China’s existing fleet of fourth-generation aircraft”

pp. 62-63–“China is advancing its development and employment of UAVs. In 2015, Chinese media reported the development of the Shendiao (Sacred Eagle or Divine Eagle) as the PLA’s newest high-altitude, long-endurance UAV for a variety of missions such as early warning, targeting, EW, and satellite communications. Last year, the PLAAF also reported on its use of a UAV to assist in HA/DR in the aftermath of an earthquake in China’s west—the first public acknowledgment of PLAAF UAV operations. Photos of the UAV showed it was the Yilong (also known as the Wing Loong or Pterodactyl).”

p. 64–“Cyber Activities Directed Against the Department of Defense. In 2015, numerous computer systems around the world, including those owned by the U.S. Government, continued to be targeted for intrusions, some of which appear to be attributable directly to the [sic] China’s Government and military.”

p. 66–“Sea-based land attack probably is an emerging requirement for the PLAN. Chinese military experts argue that in order to pursue a defensive strategy in far seas, the Navy must improve its ability to control land from the sea through long-range LACM development.”

p. 67–“China continues to field an ASBM based on a variant of the CSS-5 (DF-21) MRBM that it began deploying in 2010. The CSS-5 Mod 5 has a range of 1,500 km and is armed with a MaRV. … the DF-26 will be capable of conducting precision strikes against ground targets, potentially placing U.S. forces on Guam at risk.”

“China may develop the capability to arm the new LUYANG III-class DDG with LACMs, giving the PLAN its first land-attack capability. Furthermore, the continued deployments of the ASCM-equipped submarines in support of counterpiracy patrols underscore China’s interest in protecting SLOCs beyond the South China Sea. These submarine deployments support an apparent Chinese requirement to project power into the Indian Ocean.”

“In 2015, a PLA report identified a military requirement to extend surveillance into the Western Pacific Ocean.”

p. 68–“In 2015, China began construction of its first domestically produced aircraft carrier. China’s next generation of carriers will probably be capable of improved endurance and of launching more varied types of aircraft, including EW, early warning, and anti-surface warfare (ASW), thus increasing the potential striking power of a PLAN “carrier battle group” in safeguarding China’s interests in areas beyond its immediate periphery. The carriers would most likely perform such missions as patrolling economically important sea lanes, conducting naval diplomacy, regional deterrence, and HA/DR.”

“logistics and intelligence support remain key obstacles, particularly in the Indian Ocean and in other areas outside the greater Asia-Pacific region. As a result, China desires expansion of its access to logistics in the Indian Ocean and will probably establish several access points in this area in the next decade.”

p. 69–“Over the last five years, China has added more than 100 ocean-going patrol ships to the CCG to increase its capacity to conduct extended offshore operations and to replace old units. In the next decade, a new force of civilian law enforcement ships will afford China the capability to patrol more robustly its claims in the East China Sea and the South China Sea. Overall, the CCG’s total force level is expected to increase by 25 percent. Some of these ships will have the capability to embark helicopters, a capability that only a few CCG ships currently have.”

2015

Andrew S. Erickson, “What Does the Pentagon Think about China’s Rising Military Might?” The National Interest, 11 May 2015.

It’s that time of year again. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has just released its annual report on Chinese military and security issues. It documents important trends in this area using information often publicly available nowhere else. Amid the usual dump of fascinating data, several broad themes stand out:

- The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) continues brisk, broad-based modernization.

- It has already achieved progress that the vast majority of militaries could only envy.

- In recent years, it has consolidated core capabilities.

- The PLA’s central focus remains two-fold:

- Safeguarding the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s ruling position by guaranteeing domestic stability in conjunction with internal security forces as necessary

- Increasing ability to exert leverage over disputed border areas, Taiwan, and unresolved island and maritime claims in the “Near Seas” (Yellow, East, and South China Seas).

- But is also developing a new outer layer of power projection and influencing capability, becoming far broader-ranging in operational scope.

- Efforts are underway to make the PLA a great power military with global reach, even if it will not be globally present or capable to U.S. standards.

In what follows, I survey the report’s key findings before assessing its limitations, and its contributions writ large.

Geographic Dynamics

In the Near Seas, China is using low-intensity coercion to further its position in maritime and territorial disputes. Overall, DoD assesses, “PLA ground, air, naval, and missile forces are increasingly able to project power to assert regional dominance during peacetime and contest U.S. military superiority during a regional conflict.” Among the most sobering shifts is the erosion of many of Taiwan’s traditional defense factors by concerted PLA development and anofficial defense budget alone that is ten times greater than Taiwan’s. In a likely testament to identity factors that render cross-Strait issues complex, Taipei now spends only ~2% of GDP on defense, a target level for European members of NATO who face no such existential threat.

In peacetime, Beijing uses incremental salami-slicing tactics to assert effective control over contested areas and features. In this regard, DoD highlights Chinese efforts to prevent Philippine resupply of Second Thomas Shoal, and mentions Luconia Shoals and Reed Bank as potential future flash points. To facilitate such gains while avoiding escalation to military conflict and direct U.S. intervention, ships from the consolidating China Coast Guard (CCG) man the front line. The PLA Navy (PLAN) remains ready back stage in a monitoring and deterrent capacity. Rapid South China Sea island reclamation stands to facilitate even more continuous presence for all such forces.

China’s “whole-of-government” approach to sovereignty assertion, and the escalatory dangers therein, were underscored in 2014 when China National Offshore Oil Company began drilling with its HYSY-981 oil rig roughly 12 nautical miles (nm) from an island disputed with Vietnam and only 120 nm from Vietnam’s coast. There China announced a security radius six-times the 500 m safety zone allowed by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. It used “paramilitary ships” (CCG and fishing boats) to fend off Vietnamese vessels with water cannons and ramming, while PLAN ships conducted “overwatch” and PLA fighter and reconnaissance aircraft and helicopters patrolled above.

In the Far Seas, Beijing is gradually extending its reach and influence with growing power projection capabilities and soft power influence. “The PLA’s growing ability to project power,” DoD judges, “augments China’s globally-oriented objectives to be viewed as a stakeholder in ensuring stability.” In 2013-14, China sent its “first” submarines to the Indian Ocean. A Shang-class (Type 093) nuclear-powered attack submarine conducted a two-month deployment. ASong-class diesel-electric submarine made the first foreign port visit by a PLAN submarine, calling twice on Colombo, Sri Lanka. Far more than their ostensible contribution to PLAN counter-piracy escorts, these new steps offered valuable area familiarization and operational experiences to Chinese undersea forces, while producing a new symbol of Chinese power projection in service of sea lane security. Meanwhile, the PLA is increasing its soft power by training foreign military officers, including those from “virtually every Latin American and Caribbean country” at its Defense Studies Institute.

Sectoral Hierarchy

China’s defense industry has improved remarkably overall. “Over the past decade,” DoD judges, “China has made dramatic improvements in all defense industrial production sectors and is comparable to other major weapon system producers like Russia and the European Union in some areas.” Still, its capabilities remain uneven and patterns of disparity prevail.

The High Ground: Space, Missile, and Cyber Systems

Following a decades-long pattern, China’s space and ballistic and cruise missile sector remains firmly in the lead. There are many concrete manifestations of its superiority. China has deployed 1,200+ short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) opposite Taiwan. The CSS-5 Mod 5 (DF-21D) anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) it has “fielded” in small numbers “gives the PLA the capability to attack ships in the western Pacific Ocean” “within 900 nm of the Chinese coastline.” Its ICBM units are benefitting from improved communications links. The DF-5 ICBM is equipped with multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs), and the new-generation DF-41 under development is “possibly capable of carrying” them as well. China is also developing hypersonic glide vehicles, and tested one in 2014. It boasts the JF12 Mach 5-9 hypersonic wind tunnel, reportedly the world’s largest.

To support what has been “extraordinarily rapid” development of conventionally armed missiles and other long-range precision strike (LRPS) capabilities, as part of the “world’s most rapidly maturing space program” China is lofting surveillance satellites in rapid succession.Gaofen-2, launched in August 2014, became “China’s first satellite capable of sub-meter resolution imaging.” It plans to launch successively improved variants of this satellite in coming years. China gained the ability to send even greater payloads to even higher orbits with the completion of a fourth satellite launch facility, Wenchang on Hainan Island, in 2014. Launches of the Long March-5 and -7 heavy lift boosters are scheduled to commence there by 2016.

Even as it increases its own use of space assets for military purposes, China is strengthening its ability to hold those of potential opponents such as the United States at risk. It is developing a range of counter-space weapons. Unusual launch patterns and activities in space suggest efforts to test such capabilities. When queried by Washington about these actions, Beijing declines to disclose details. Meanwhile, the PLA emphasizes electronic warfare capabilities, and is deploying “jamming equipment against multiple communication and radar systems and GPS satellite systems” on sea- and air-based platforms.

Chinese cyber capabilities have recently joined the top tier as well, with DoD long subjected to numerous intrusions. Beijing is also attempting to use its position in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and other international fora to promote conditions whereby sovereign states can wield greater control over cyberspace governance, both within their borders and even beyond.

Steaming Smartly Ahead: Maritime Systems

Maritime hardware comes next. Warship quantity is impressive: “The PLA Navy now possesses the largest number of vessels in Asia.” But quality is emphasized even more; China is replacing older platforms with newer, more capable ones. China’s shipbuilding industry has finally begun series production of multiple vessel classes. The Luyang-III-class (Type 052D) destroyer, which first entered service in 2014, has a vertical launch system capable of firing anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs), surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), and “antisubmarine missiles.” The Type 055 guided-missile cruiser slated to begin construction in 2015 will wield similar armaments. These include the submarine- and ship-launched YJ-18 ASCM, which DoD terms a “dramatic improvement” over the already-potent SS-N-27 that China previously purchased from Russia with eight of twelve Kilo-class submarines. This will greatly strengthen area air defense capabilities: Chinese naval task forces will increasingly be able to take a protective “umbrella” with them to distant seas far removed from the 300 nm-from-shore envelope of China’s extensive land-based Integrated Air Defense System (IADS). In addition, DoD judges that such warships may be close to fielding LACMs, which would give the PLAN its first capability to strike shore targets Tomahawk missile-style.

While civil maritime vessels are far less sophisticated than their naval counterparts, and typically lack major armaments, within this lower-intensity context the CCG is enjoying a buildup far more quantitatively impressive than that of the PLAN. It is already the world’s largest blue-water coast guard fleet, with more hulls than all its neighboring counterparts combined—and that includes the rightly-respected Japan Coast Guard. From 2004-08, it added nearly twenty ocean-going patrol ships; by the end of 2015, it is projected to have added another 30+ new vessels of this type. Together with the construction of “more than 100 new patrol craft and smaller units,” this will produce a total force level increase of 25%—growth simply unparalleled anywhere else on the world’s oceans. And that is even as many older platforms are replaced by new, improved ones; with many more having helicopter embarking capability than previously.

Gaining Altitude: Aviation Systems

Lower in achievement thus far but improving rapidly is Chinese military aviation. Quantitatively, the PLA Air Force (PLAAF) is Asia’s largest, and the world’s third largest. The PLAN has an aviation force of its own, which is growing to provide air wings for the “multiple” carriers DoD believes China may build over the next fifteen years. Limitations persist: Beijing’s first carrier,Liaoning, is not expected to embark an air wing “until 2015 or later.” China remains weak in aeroengines, and may soon import perhaps two dozen Russian Su-35S fighters in part for their advanced engines and radars. Yet the PLAAF “is rapidly closing the gap with western air forces across a broad spectrum of capabilities.”

China “is the only country in the world other than the United States to have two concurrent stealth fighter programs.” DoD anticipates the maiden flight of the fifth J-20 low-observable fighter prototype in 2015, while the J-31 fighter may be offered for export. Variants of the Y-20 transport—which may be commissioned in 2016—could provide badly needed troop movement, refueling, and airborne early warning and control (AWACs) capabilities. New variants of the venerable H-6 bomber have been exquisitely retrofitted to serve as tankers and to carry significant weapons load outs, including the YJ-12 supersonic ASCM and the CJ-20 LACM.

Meanwhile, China is placing major emphasis on UAVs. DoD cites a 2013 report by the Defense Science Board, which judges that “China’s move into unmanned systems is ‘alarming’ and combines unlimited resources with technological awareness that might allow China to match or even outpace U.S. spending on unmanned systems in the future.” No fewer than three long-range precision-strike variants under development. The BZK-005 UAV has already been observed conducting intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) over the East China Sea. Without elaboration, DoD notes: “Some estimates indicate China plans to produce upwards of 41,800 land- and sea-based unmanned systems, worth about $10.5 billion, between 2014 and 2023.”

Finally, as part of China’s IADS, the PLAAF also maintains one of the world’s largest forces of advanced long-range SAMs. China is not as strong in SAMs as it is in other ballistic (and cruise) missiles, but is acquiring the long-range S-400 system from Russia, even as it continues to develop long-range indigenous systems such as the CSA-9 for IAD and ballistic missile defense (BMD).

Ground force materiel is typically last in sophistication, although the report offers few specifics. It does draw attention to China’s prioritization and rapid deployment of internal security forces. This pattern has only intensified in response to dozens of deaths from domestic unrest and terrorism in recent years, particularly in conjunction with Xinjiang.

Weaknesses and Attempts to Rectify Them

On the hardware side, China is still missing some critical technologies, industrial processes, and related knowhow. It “continues to lack either a robust coastal or deep water anti-submarine warfare capability,” and its ability to collect and disseminate targeting information in real time under wartime conditions remains uncertain.

Through determined multi-pronged effort, however, Beijing is progressively closing many of the remaining gaps. It continues to obtain significant technologies, components, and systems from abroad. As in the 1990s (albeit to a less extreme degree today), Russian and Ukrainian economic woes facilitate Chinese access to advanced expertise and systems (including S-400 SAMs, Su-35 fighters, and the Petersburg/Lada-class submarine production program from the former; assault hovercraft and aeroengines from the latter). Much technology acquired for commercial aircraft and other civilian programs has military applications. Along the way, DoD documents multiple cases of Chinese nationals seeking to transfer foreign technology illegally. Finally, China is consolidating its own state S&T research funding. Having bet big on nanotechnology, for instance, it now trails only the United States in research funding for that field.

Amelioration of software weaknesses requires laborious human capital investment and wrenching organizational reforms, but the PLA and its civilian masters are clearly determined to prevail even here. As part of enhancement of training realism emphasized by Xi, the PLA is increasing “joint” pan-Military Region exercises. Further reforms likely under consideration include reducing non-combat forces and the relative proportion of ground forces; elevating the proportion and roles of enlisted personnel and non-commissioned officers vis-à-vis commissioned officers; bolstering “new-type combat forces” for naval aviation, cyber, and special operations; establishing a theater joint command system; and reducing China’s current seven Military Regions by as many as two.

Finally, if Beijing is to secure the overseas influence and reach it increasingly desires, foreign policy adjustments will be required. Logistics and intelligence support remain key constraints on Chinese operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond. To remedy this, DoD assesses, Beijing “willlikely establish several access points in this area in the next 10 years. These arrangements likely will take the form of agreements for refueling, replenishment, crew rest, and low-level maintenance. The services provided likely will fall short of permitting the full spectrum of support from repair to re-armament.”

Positive Chinese Contributions and Bilateral Military Relations

Despite the above concerns, DoD also takes pains to recognize positive, growing Chinese contributions to international security and military-to-military relations with the U.S. It documents in exhaustive detail the frequent exchanges and discussions between the two militaries, as well as bilateral and multilateral military exercises dating to 2008. It clearly strives for a balanced approach: “As the United States builds a stronger foundation for a military-to-military relationship with China, it must also continue to monitor China’s evolving military strategy, doctrine, and force development, and encourage China to be more transparent about its military modernization program. In concert with its allies and partners, the United States will continue adapting its forces, posture, and operational concepts to maintain a stable and secure Asia-Pacific security environment.”

Limitations of the Report Itself

Like many products of complex bureaucratic exercises amid far greater competing priorities, this report suffers slightly from omissions, small weaknesses, and inconsistencies. The Maritime Militia, an important component of China’s Cabbage Strategy of enveloping disputed features in layers of non-military forces that opponents might hesitate to use force against, is not mentioned once. With regard to shipbuilding, DoD’s broad brushstrokes obscure lingering unevenness. It names China “the top ship-producing nation in the world,” but omits the critical qualifier that this is in terms of gross commercial tonnage; not sophistication, systems, technology, or quality. Ranges quoted for anti-ship cruise missiles are not explained; some may be debatable in practice depending on the assumptions used to calculate them. Likewise unexplained is DoD’s methodology for calculating China’s total 2014 military spending at $165 billion (against the official figure of $136.3 billion for that year).

Moreover, Pentagon reports are typically stronger in analyzing hardware than software, and this one is no exception. The disparity manifests most prominently in two instances. First, DoD offers incomplete, seemingly uncritical analysis of the “new type of major power relations” advocated by Xi Jinping and other Chinese officials. This may be part of a larger pattern in which the Obama Administration has fallen into the trap of appearing to embrace this loaded meme, whichcarries Chinese expectations of Washington accommodating China’s “core” sovereignty interests without reciprocal concessions from Beijing. It is arguably somewhat disjointed for DoD to express such significant concerns about Chinese weapons systems, while avoiding critical analysis of some of the very policy approaches that inform their threatened worst-case use. Second, the report misses a chance to put in full context the important keynote address that Xi delivered at the CCP Central Foreign Affairs Work Conference in 2014. While the full text remains unavailable in public, subsequent bureaucratic activities and official statements suggest that it may represent a watershed in Xi’s exhorting officials to propose more considerably more assertive external policies. Given the clarity it brings to details of Chinese security hardware, it is unfortunate that DoD could not shed more light on the high-level policies that inform its development and employment.

Undeniable Contribution