CMSI China Maritime Report #10: “PLAN Force Structure Projection Concept: A Methodology for Looking Down Range”

Capt. Christopher P. Carlson, USNR (Ret.), PLAN Force Structure Projection Concept: A Methodology for Looking Down Range, China Maritime Report 10 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2020).

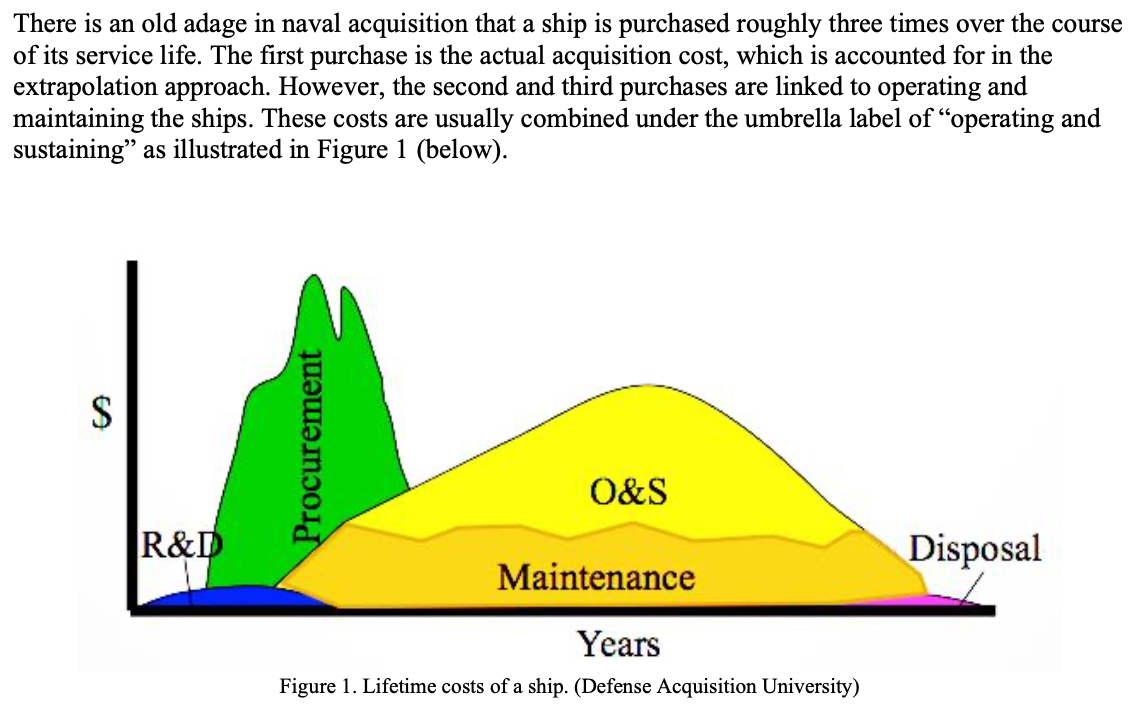

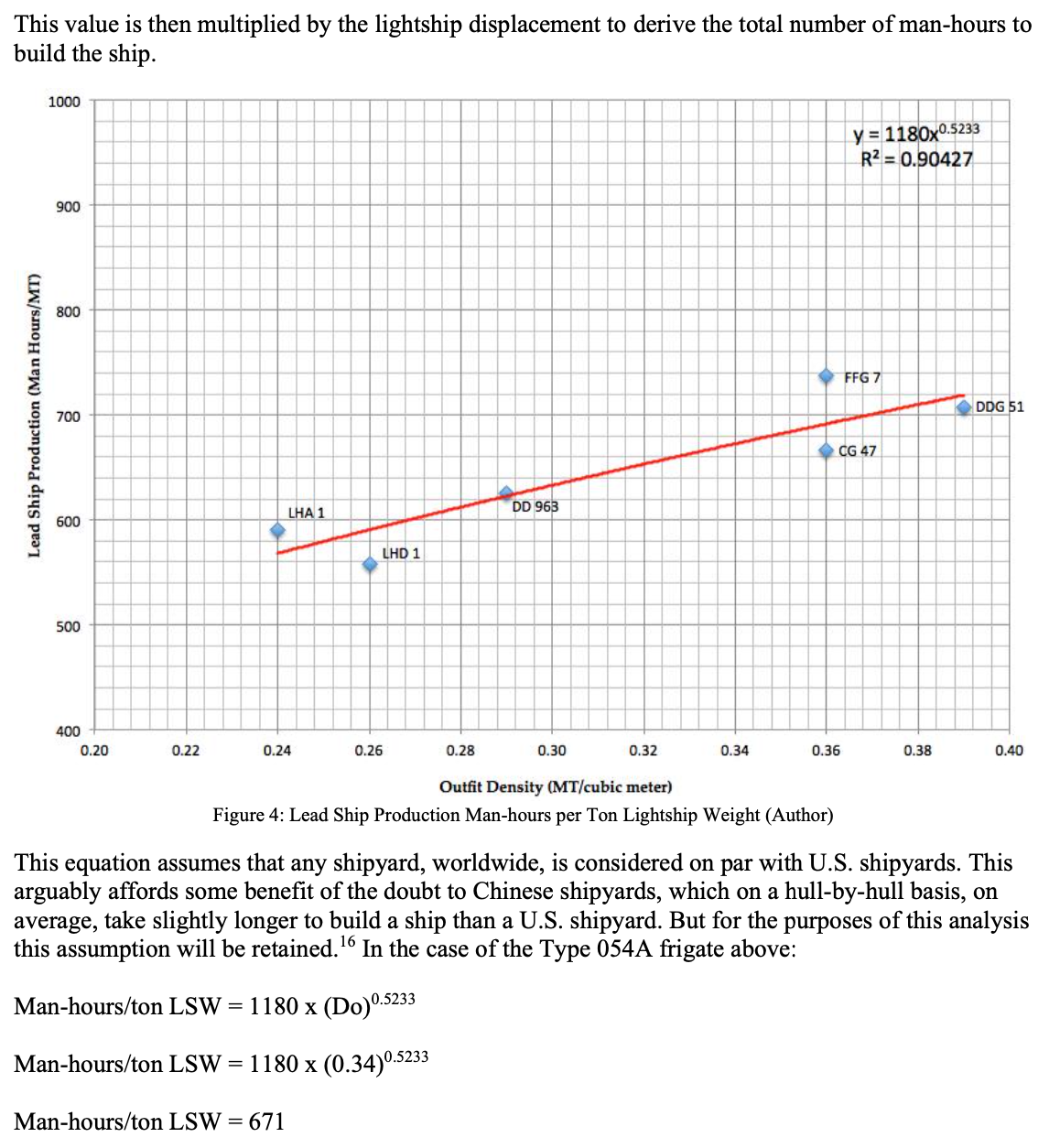

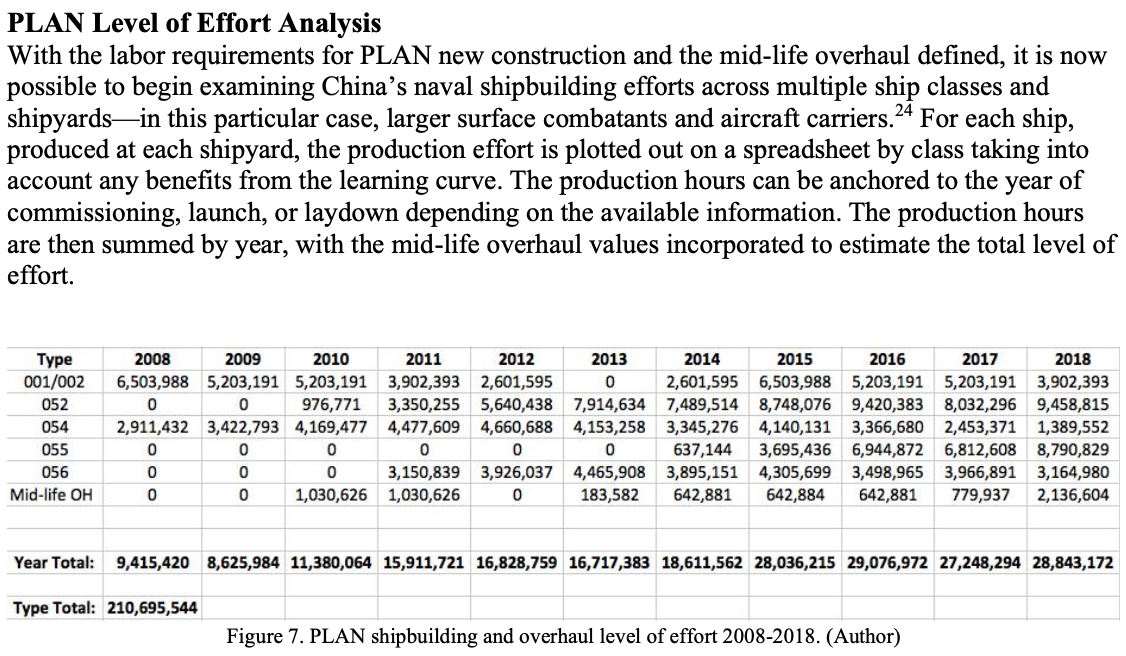

Force structure projections of an adversary’s potential order of battle are an essential input into the strategic planning process. Currently, the majority of predictions regarding China’s future naval buildup are based on a simple extrapolation of the impressive historical ship construction rate and shipyard capacity, without acknowledging that the political and economic situation in China has changed dramatically. Basing force structure projections on total life-cycle costs would be the ideal metric, but there is little hope of getting reliable data out of China. A reasonable substitute in shipbuilding is to look at the construction man-hours, as direct labor accounts for 30-50 percent of a ship’s acquisition cost, depending on the ship type, and is therefore a representative metric of the amount of resources and effort applied to a ship’s construction. The direct labor man-hours to build a Chinese surface combatant can be estimated by linking a ship’s outfit density to historical U.S. information. This analytical model also allows for the inclusion of the mid-life overhaul and modernization for each ship, which is a major capital expense in the out years following initial procurement. For the naval analyst examining the Chinese Navy’s future force structure, the outfit density concept provides a tool to evaluate the degree of national effort when it comes to military shipbuilding.

PREVIOUS STUDIES IN THIS CMSI SERIES:

Roderick Lee and Morgan Clemens, Organizing to Fight in the Far Seas: The Chinese Navy in an Era of Military Reform, China Maritime Report 9 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, October 2020).

CMSI has just published China Maritime Report No. 9, entitled Organizing to Fight in the Far Seas: The Chinese Navy in an Era of Military Reform. Written by Mr. Roderick Lee and Mr. Morgan Clemens, this report discusses the challenges that PLA reform and PLA Navy (PLAN) strategy intend to resolve, highlights key organizational developments within the PLAN that preceded China’s military reform, and discusses the known facts of command and control of PLAN forces operating in the far seas.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has been laying the organizational groundwork for far seas operations for nearly two decades, developing logistical and command infrastructure to support a “near seas defense and far seas protection” strategy. In the context of such a strategy, the PLAN’s ability to project power into the far seas depends upon its ability to dominate the near seas, effectively constituting a “sword and shield” approach. Along with the rest of the PLA, the PLAN’s peacetime command structure has been brought into line with its wartime command structures, and in terms of near seas defense, those command structures have been streamlined and made joint. By contrast, the command arrangements for far seas operations have not been clearly delineated and no one organ or set of organs has been identified as responsible for them. While this is manageable in the context of China’s current, limited far seas operational presence, any meaningful increase in the size, scope, frequency, and intensity of far seas operations will require further structural reforms at the Central Military Commission and theater command levels in order to lay out clear command responsibilities.

Timothy R. Heath, Winning Friends and Influencing People: Naval Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics, China Maritime Report 8 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, September 2020).

In recent years, Chinese leaders have called on the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to carry out tasks related to naval diplomacy beyond maritime East Asia, in the “far seas.” Designed to directly support broader strategic and foreign policy objectives, the PLAN participates in a range of overtly political naval diplomatic activities, both ashore and at sea, from senior leader engagements to joint exercises with foreign navies. These activities have involved a catalogue of platforms, from surface combatants to hospital ships, and included Chinese naval personnel of all ranks. To date, these acts of naval diplomacy have been generally peaceful and cooperative in nature, owing primarily to the service’s limited power projection capabilities and China’s focus on more pressing security matters closer to home. However, in the future a more blue-water capable PLAN could serve more overtly coercive functions to defend and advance China’s rapidly growing overseas interests when operating abroad.

Isaac B. Kardon, Conor M. Kennedy, and Peter A. Dutton, Gwadar: China’s Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan, China Maritime Report 7 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, August 2020).

China Maritime Report No. 7 offers a detailed examination of China’s infrastructure project in the port of Gwadar, Pakistan. Written by Dr. Peter Dutton, Dr. Isaac Kardon, and Mr. Conor Kennedy, this report is the second in a series of studies looking at China’s interest in Indian Ocean ports and its “strategic strongpoints” there (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms. Gwadar is an inchoate “strategic strongpoint” in Pakistan that may one day serve as a major platform for China’s economic, diplomatic, and military interactions across the northern Indian Ocean region. As of August 2020, it is not a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base, but rather an underdeveloped and underutilized commercial multipurpose port built and operated by Chinese companies in service of broader PRC foreign and domestic policy objectives. Foremost among PRC objectives for Gwadar are (1) to enable direct transport between China and the Indian Ocean, and (2) to anchor an effort to stabilize western China by shoring up insecurity on its periphery. To understand these objectives, this case study first analyzes the characteristics and functions of the port, then evaluates plans for hinterland transport infrastructure connecting it to markets and resources. We then examine the linkage between development in Pakistan and security in Xinjiang. Finally, we consider the military potential of the Gwadar site, evaluating why it has not been utilized by the PLA then examining a range of uses that the port complex may provide for Chinese naval operations.

Peter A. Dutton, Isaac B. Kardon, and Conor M. Kennedy, Djibouti: China’s First Overseas Strategic Strongpoint, China Maritime Report 6 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, April 2020).

This report analyzes PRC economic and military interests and activities in Djibouti. The small, east African nation is the site of the PLA’s first overseas military base, but also serves as a major commercial hub for Chinese firms—especially in the transport and logistics industry. We explain the synthesis of China’s commercial and strategic goals in Djibouti through detailed examination of the development and operations of commercial ports and related infrastructure. Employing the “Shekou Model” of comprehensive port zone development, Chinese firms have flocked to Djibouti with the intention of transforming it into a gateway to the markets and resources of Africa—especially landlocked Ethiopia—and a transport hub for trade between Europe and Asia. With diplomatic and financial support from Beijing, PRC firms have established a China-friendly business ecosystem and a political environment that proved conducive to the establishment of a permanent military presence. The Gulf of Aden anti-piracy mission that justified the original PLA deployment in the region is now only one of several missions assigned to Chinese armed forces at Djibouti, a contingent that includes marines and special forces. The PLA is broadly responsible for the security of China’s “overseas interests,” for which Djibouti provides essential logistical support. China’s first overseas strategic strongpoint at Djibouti is a secure commercial foothold on the African continent and a military platform for expanding PLA operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

Daniel Caldwell, Joseph Freda, and Lyle Goldstein, China’s Dreadnought? The PLA Navy’s Type 055 Cruiser and Its Implications for the Future Maritime Security Environment, China Maritime Report 5 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, February 2020).

China’s naval modernization, a process that has been underway in earnest for three decades, is now hitting its stride. The advent of the Type 055 cruiser firmly places the PLAN among the world’s very top naval services. This study, which draws upon a unique set of Chinese-language writings, offers the first comprehensive look at this new, large surface combatant. It reveals a ship that has a stealthy design, along with a potent and seemingly well-integrated sensor suite. With 112 VLS cells, moreover, China’s new cruiser represents a large magazine capacity increase over legacy surface combatants. Its lethality might also be augmented as new, cutting edge weaponry could later be added to the accommodating design. This vessel, therefore, provides very substantial naval capability to escort Chinese carrier groups, protect Beijing’s long sea lanes, and take Chinese naval diplomacy to an entirely new and daunting level. Even more significant perhaps, the Type 055 will markedly expand the range and firepower of the PLAN and this could substantially impact myriad potential conflict scenarios, from the Indian Ocean to the Korean Peninsula and many in between. This study of Type 055 development, moreover, does yield evidence that Chinese naval strategists are acutely aware of major dilemmas confronting the U.S. Navy surface fleet.

Conor M. Kennedy, Civil Transport in PLA Power Projection, China Maritime Report 4 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, December 2019).

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has ambitious goals for its power projection capabilities. Aside from preparing for the possibility of using force to resolve Beijing’s territorial claims in East Asia, it is also charged with protecting China’s expanding “overseas interests.” These national objectives require the PLA to be able to project significant combat power beyond China’s borders. To meet these needs, the PLA is building organic logistics support capabilities such as large naval auxiliaries and transport aircraft. But it is also turning to civilian enterprises to supply its transportation needs.

Ryan D. Martinson and Peter A. Dutton, China’s Distant-Ocean Survey Activities: Implications for U.S. National Security, China Maritime Report 3 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2018).

Today, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is investing in marine scientific research on a massive scale. This investment supports an oceanographic research agenda that is increasingly global in scope. One key indicator of this trend is the expanding operations of China’s oceanographic research fleet. On any given day, 5-10 Chinese “scientific research vessels” (科学考查船) may be found operating beyond Chinese jurisdictional waters, in strategically-important areas of the Indo-Pacific. Overshadowed by the dramatic growth in China’s naval footprint, their presence largely goes unnoticed. Yet the activities of these ships and the scientists and engineers they embark have major implications for U.S. national security. This report explores some of these implications. It seeks to answer basic questions about the out-of-area—or “distant-ocean” (远洋)—operations of China’s oceanographic research fleet. Who is organizing and conducting these operations? Where are they taking place? What do they entail? What are the national drivers animating investment in these activities?

Ryan D. Martinson, The Arming of China’s Maritime Frontier, China Maritime Report 2 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, June 2017).

China’s expansion in maritime East Asia has relied heavily on non-naval elements of sea power, above all white-hulled constabulary forces. This reflects a strategic decision. Coast guard vessels operating on the basis of routine administration and backed up by a powerful military can achieve many of China’s objectives without risking an armed clash, sullying China’s reputation, or provoking military intervention from outside powers. Among China’s many maritime agencies, two organizations particularly fit this bill: China Marine Surveillance (CMS) and China Fisheries Law Enforcement (FLE). With fleets comprising unarmed or lightly armed cutters crewed by civilian administrators, CMS and FLE could vigorously pursue China’s maritime claims while largely avoiding the costs and dangers associated with classic “gunboat diplomacy.”

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA, China Maritime Report 1 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, March 2017).

Amid growing awareness that China’s Maritime Militia acts as a Third Sea Force which has been involved in international sea incidents, it is necessary for decision-makers who may face such contingencies to understand the Maritime Militia’s role in China’s armed forces. Chinese-language open sources reveal a tremendous amount about Maritime Militia activities, both in coordination with and independent of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Using well-documented evidence from the authors’ extensive open source research, this report seeks to clarify the Maritime Militia’s exact identity, organization, and connection to the PLA as a reserve force that plays a parallel and supporting role to the PLA. Despite being a separate component of China’s People’s Armed Forces (PAF), the militia are organized and commanded directly by the PLA’s local military commands. The militia’s status as a separate non-PLA force whose units act as “helpers of the PLA” (解放军的 助手) is further reflected in China’s practice of carrying out “joint military, law enforcement, and civilian [Navy-Maritime Law Enforcement-Maritime Militia] defense” (军警民联防). To more accurately capture the identity of the Maritime Militia, the authors propose referring to these irregular forces as the “People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia” (PAFMM).