O’Rourke’s Latest CRS Report—USG/N Info on PLAN Ships & Projections of #s Lead thru 2040—“China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities”

As part of Ronald O’Rourke’s continuous incremental improvements, this 261st (!) edition of his report on PRC naval modernization incorporates numbers provided by the U.S. Navy. Given the authoritative analysis supporting these revelations, and the rarity with which they are made publicly available in this manner, they are all worth reading carefully in full!

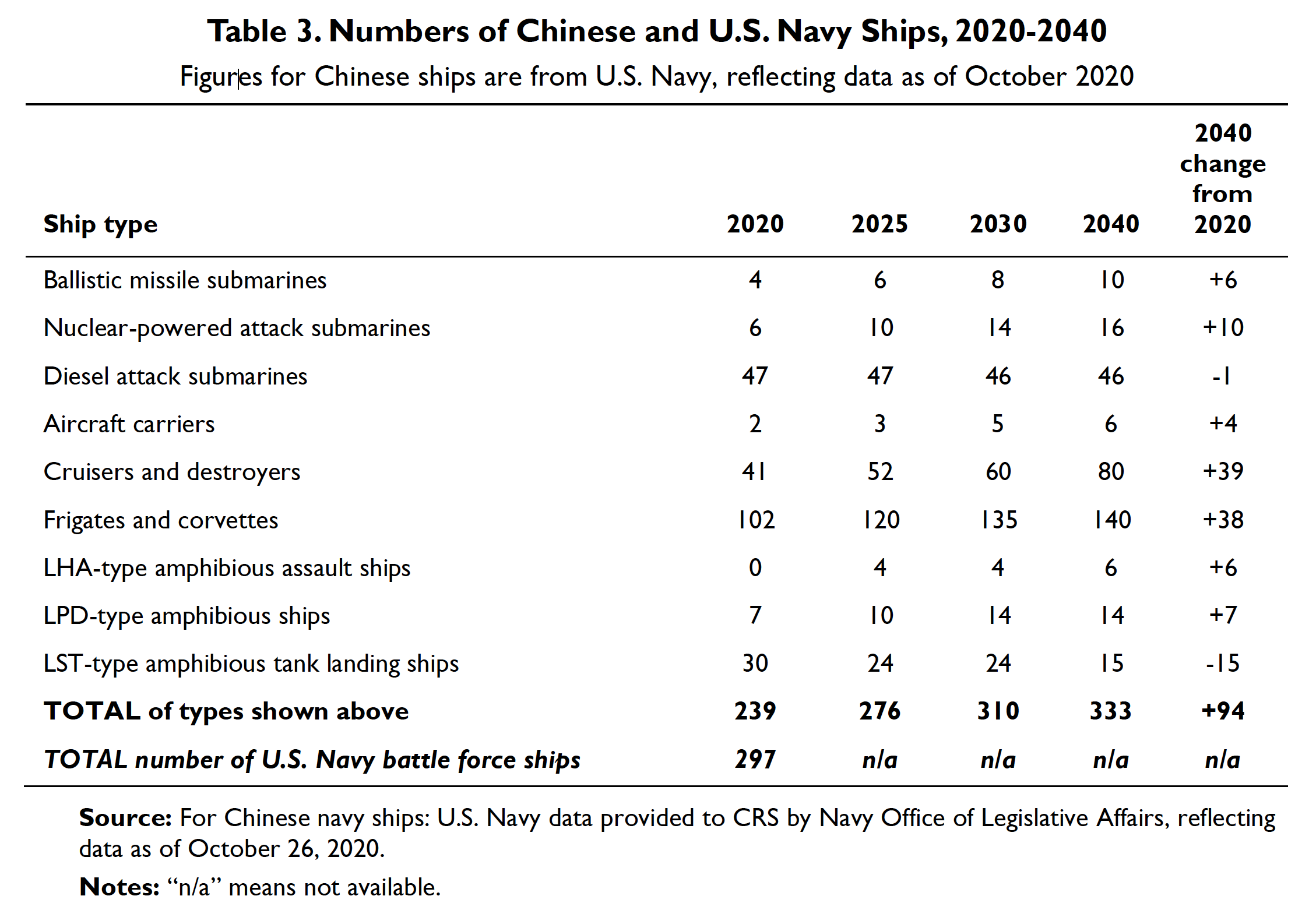

Bottom line up front: here’s the key table (p. 10):

By 2040, the PLA Navy is thus projected to have the following:

- Ballistic missile submarines (SSBN): 10 (+6)

- Nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSN): 16 (+10)

- Diesel attack submarines (SSK): 46 (-1)

- Aircraft carriers (CV): 6 (+4)

- Cruisers and destroyers (CG & DDG): 80 (+39)

- Frigates and corvettes (FFG & FFL): 140 (+38)

- Amphibious Assault Ship-type amphibious ships (LHA): 6 (+6)

- Amphibious Transport Dock-type amphibious ships 14 (LPD): (+7)

- Tank Landing Ship-type amphibious ships (LST): 15 (-15)

- TOTAL of above-mentioned types: 333 (+94)

Ronald O’Rourke, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, RL33153 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 8 March 2022).

Having trouble accessing the website above? Please download a cached copy here!

You can also click here to access the report via the public CRS website.

Here’s another important table (p. 7):

Note from me (Andrew Erickson): The U.S. Navy is duty bound to count PLA Navy ship numbers strictly according to the criteria listed in SECNAVINST 5030.8C (“General Guidance for the Classification of Naval Vessels and Battle Force Ship Counting Procedures”). The resulting battle force numbers calculated for China therefore correspond numerically with those for the U.S. Navy battle force. To be sure, aspects of the analysis and implications can be complex in practice, and O’Rourke offers thoughtful explanations and implications in his frequently-updated report.

Further references:

- United States Navy ships

- U.S. Navy Ships – Index

- List of naval ship classes in service

- Nomenclature of Naval Vessels

Now, back to the specific contents of O’Rourke’s report…

p. 1

This report is based on unclassified open-source information, such as the annual Department of Defense (DOD) report to Congress on military and security developments involving China,4 a 2019 Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) report on China’s military power,5 a 2015 Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) report on China’s navy,6 published reference sources such as IHS Jane’s Fighting Ships,7 and press reports.

***

4 Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, Annual Report to Congress, released on November 3, 2021, 173 pp. Hereinafter 2021 DOD CMSD.

5 Defense Intelligence Agency, China Military Power, Modernizing a Force to Fight and Win, 2019, 125 pp. Hereinafter 2019 DIA CMP.

6 Office of Naval Intelligence, The PLA Navy, New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century, undated but released in April 2015, 47 pp.

7 IHS Jane’s Fighting Ships 2018-2019, and previous editions. Other sources of information on these shipbuilding programs may disagree regarding projected ship commissioning dates or other details, but sources present similar overall pictures regarding PLA Navy shipbuilding.

p. 5

In addition to modernizing its navy, China in recent years has substantially increased the size and capabilities of its coast guard. DOD states that China’s coast guard is “by far the largest coast guard force in the world…. ”25 China also operates a sizeable maritime militia that includes a large number of fishing vessels. China relies primarily on its maritime militia and coast guard to assert and defend its maritime claims in its near-seas region, with the navy operating over the horizon as a potential backup force.26

Numbers of Ships; Comparisons to U.S. Navy

Overview

DOD states that “the PLAN is the largest navy in the world with a battle force of approximately 355 platforms, including major surface combatants, submarines, aircraft carriers, ocean-going amphibious ships, mine warfare ships, and fleet auxiliaries. This figure does not include 85 patrol

***

25 DOD states that

The CCG’s [China Coast Guard’s] rapid expansion and modernization has improved the PRC’s ability to enforce its maritime claims. Since 2010, the CCG’s fleet of large patrol ships ([i.e., those displacing] more than 1,000 tons) has more than doubled from approximately 60 to more than 130 ships, making it by far the largest coast guard force in the world and increasing its capacity to conduct simultaneous, extended offshore operations in multiple disputed areas. Furthermore, the newer ships are substantially larger and more capable than the older ships, and the majority are equipped with helicopter facilities, high-capacity water cannons, and guns ranging from 30 mm to 76 mm. A number of these ships are capable of long-endurance and out-of-area operations.

In addition, the CCG operates more than 70 fast patrol combatants (more than 500 tons), which can be used for limited offshore operations, more than 400 coastal patrol craft, and approximately 1,000 inshore and riverine patrol boats.

(2021 DOD CMSD, pp. 75-76. See also 2019 DIA CMP, p. 78.)

26 For additional discussion, see 2021 DOD CMSD, p. 76, and CRS Report R42784, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

p. 6

combatants and craft that carry anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs). The PLAN’s overall battle force is expected to grow to 420 ships by 2025 and 460 ships by 2030. Much of this growth will be in major surface combatants.”27 DIA states that “the PLAN is rapidly retiring older, single-mission warships in favor of larger, multimission ships equipped with advanced antiship, antiair, and antisubmarine weapons and sensors and C2 [command and control] facilities.”28

Ultimate Size and Composition of China’s Navy Not Publicly Known

The planned ultimate size and composition of China’s navy is not publicly known. The U.S. Navy makes public its force-level goal and regularly releases a 30-year shipbuilding plan that shows planned procurements of new ships, planned retirements of existing ships, and resulting projected force levels, as well as a five-year shipbuilding plan that shows, in greater detail, the first five years of the 30-year shipbuilding plan.29 In contrast, China does not release a navy force-level goal or detailed information about planned ship procurement rates, planned total ship procurement quantities, planned ship retirements, or resulting projected force levels. The ultimate size and composition of China’s navy might be an unsettled and evolving issue among Chinese military and political leaders. One observer states that “it seems the majority of past foreign projections of Chinese military and Chinese navy procurement scale and speed have been underestimates…. All military forces have a desired force requirement and a desired ‘critical mass’ to aspire toward. Whether the Chinese navy is close to its desired force or not, is of no small consequence.”30

Number of Ships Is a One-Dimensional Measure, but Trends in Numbers Can Be of Value Analytically

Relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities are sometimes assessed by showing comparative numbers of U.S. and Chinese ships. Although the total number of ships in a navy (or a navy’s aggregate tonnage) is relatively easy to calculate, it is a one-dimensional measure that leaves out numerous other factors that bear on a navy’s capabilities and how those capabilities compare to its assigned missions. As a result, as discussed in further detail in Appendix A, comparisons of the total numbers of ships in China’s navy and the U.S. Navy are highly problematic as a means of assessing relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities and how those capabilities compare to the missions assigned to the two navies. At the same time, however, an examination of trends over time in these relative numbers of ships can shed some light on how the relative balance of U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities might be changing over time.

Three Tables Showing Numbers of Chinese and U.S. Navy Ships

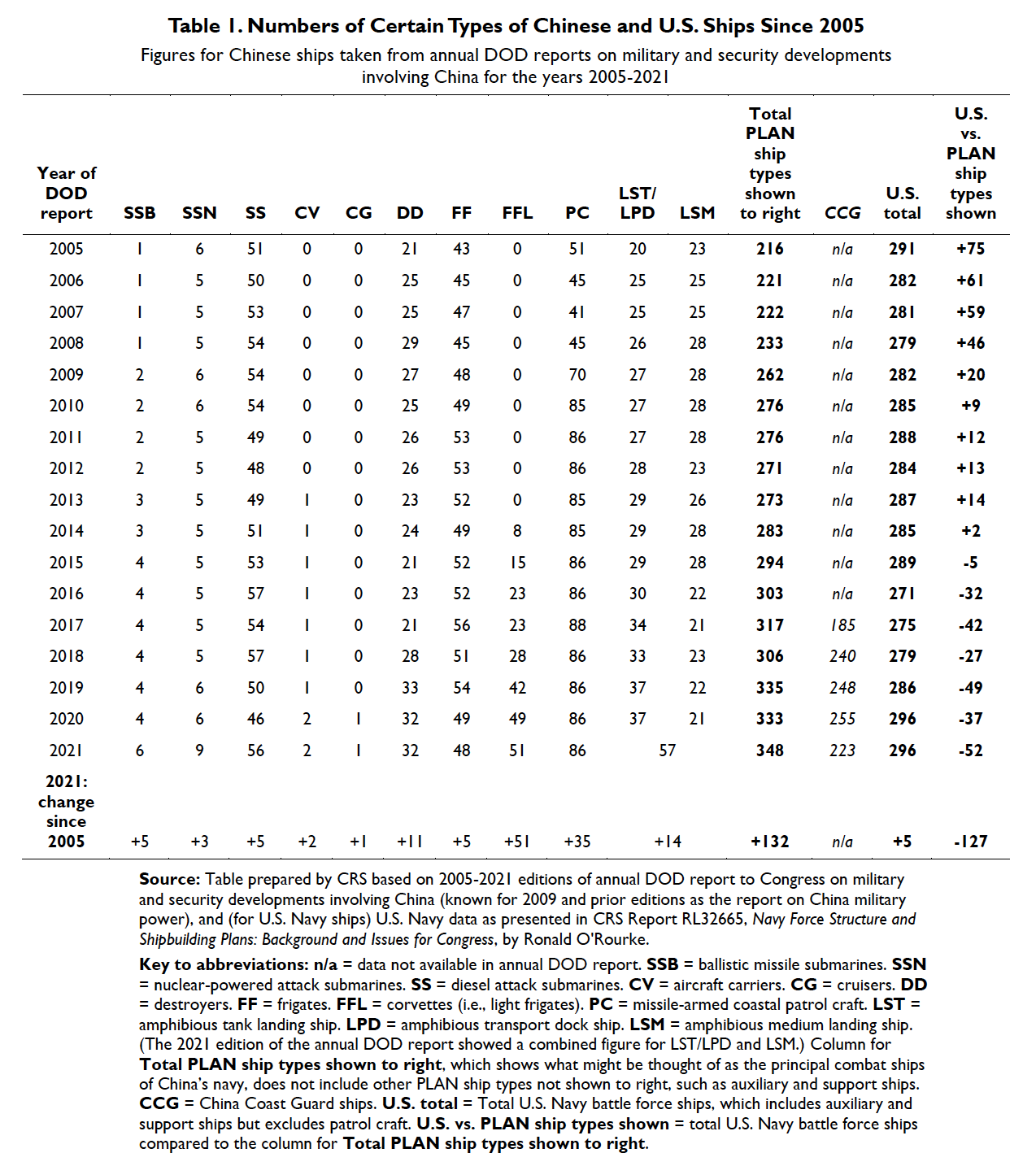

Table Showing Figures from Annual DOD Reports

Table 1 shows numbers of certain types of Chinese navy ships—those that might be thought of as the principal combat ships of China’s navy—from 2005 to the present, along with the number of China coast guard ships from 2017 to the present, as presented in DOD’s annual reports on

***

27 2021 DOD CMSD, p. 49. See also pp. vi, 48, and 2019 DIA CMP, p. 63.

28 2019 DIA CMP, p. 69.

29 For more information on the U.S. Navy’s force-level goal, 30-year shipbuilding plan, and five-year shipbuilding plan, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

30 Rick Joe, “Hints of Chinese Naval Procurement Plans in the 2020s,” Diplomat, December 25, 2020.

p. 7

p. 8

Notes: The DOD report generally covers events of the prior calendar year. Thus, the 2021 edition covers events during 2020, and so on for earlier years. Similarly, for the U.S. Navy figures, the 2021 column shows the figure for the end of FY2020, and so on for earlier years.

About 65% of the increase since 2005 in the total number of Chinese navy ships shown in the table (a net increase of 86 ships out of a total net increase of 132 ships) resulted from increases in missile-armed fast patrol craft starting in 2009 (a net increase of 35 ships) and corvettes starting in 2014 (51 ships). These are the smallest surface combatants shown in the table. The net 35-ship increase in missile-armed fast patrol craft was due to the construction between 2004 and 2009 of 60 new Houbei (Type 022) fast attack craft31 and the retirement of 25 older fast attack craft that were replaced by Type 022 craft. The 51-ship increase in corvettes is due to the Jingdao (Type 056) corvette program discussed later in this report. ONI states that “a significant portion of China’s Battle Force consists of the large number of new corvettes and guided-missile frigates recently built for the PLAN.”32 As can also be seen in the table, most of the remaining increase since 2005 in the number of Chinese navy ships shown in the table is accounted for by increases in amphibious ships (14 ships) and cruisers and destroyers (12 ships).

Table 1 lumps together less-capable older Chinese ships with more-capable modern Chinese ships. In examining the numbers in the table, it can be helpful to keep in mind that for many of the types of Chinese ships shown in the table, the percentage of the ships accounted for by more capable modern designs was growing over time, even if the total number of ships for those types was changing little.

For reference, Table 1 also shows the total number of ships in the U.S. Navy (known technically as the total number of battle force ships), and compares it to the total number of the types of Chinese ships that are shown in the table. The result is an apples-vs.-oranges comparison, because the Chinese figures exclude certain ship types, such as auxiliary and support ships, while the U.S. Navy figure includes auxiliary and support ships but excludes patrol craft. Changes over time in this apples-vs.-oranges comparison, however, can be of value in understanding trends in the comparative sizes of the U.S. and Chinese navies.

On the basis of the figures in Table 1, it might be said that in 2015, the total number of principal combat ships in China’s navy surpassed the total number of U.S. Navy battle force ships (a figure that includes not only the U.S. Navy’s principal combat ships, but also other U.S. Navy ships, such as auxiliary and support ships). It is important, however, to keep in mind the differences in composition between the two navies. The U.S. Navy, for example, has many more aircraft carriers, nuclear-powered submarines, and cruisers and destroyers, while China’s navy has many more diesel attack submarines, frigates, and corvettes.

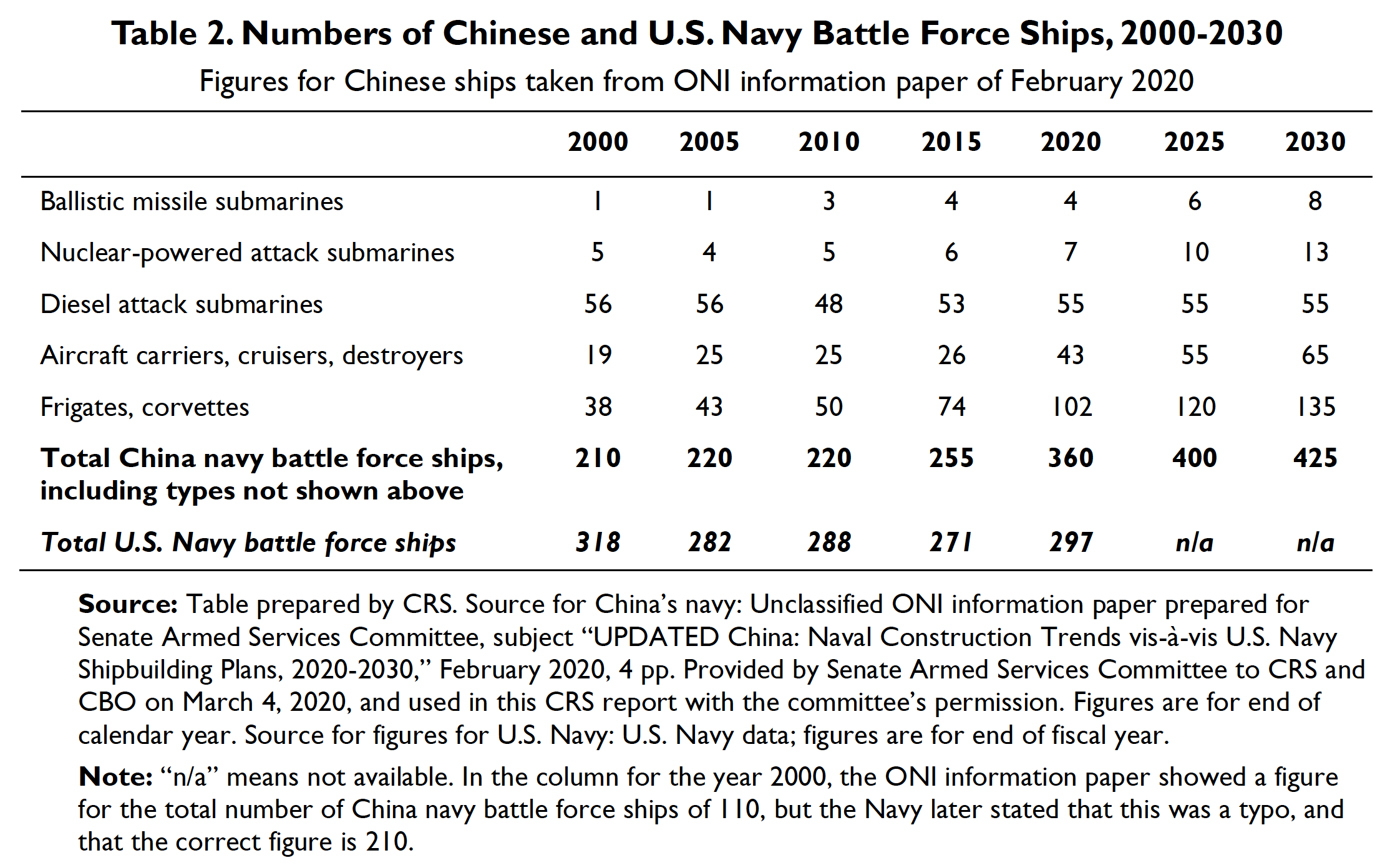

Table Showing ONI Figures from February 2020

Table 2 shows comparative numbers of Chinese and U.S. battle force ships (and figures for certain types of ships that contribute toward China’s total number of battle force ships) from 2000 to 2030, with the figures for 2025 and 2030 being projections. The figures for China’s ships are taken from an ONI information paper of February 2020. Battle force ships are the types of ships that count toward the quoted size of the Navy. For China, the total number of battle force ships shown excludes the missile-armed coastal patrol craft shown in Table 1, but includes auxiliary

***

31 The Type 022 program was discussed in the August 1, 2018, version of this CRS report, and earlier versions.

32 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 9

and support ships that are not shown in Table 1. Compared to Table 1, the figures in Table 2 come closer to providing an apples-to-apples comparison of the two navies’ numbers of ships, although it could be argued that China’s missile-armed coastal patrol craft can be a significant factor for operations within the first island chain.

Table 2. Numbers of Chinese and U.S. Navy Battle Force Ships, 2000-2030

On the basis of the figures in Table 2, it might be said that China’s navy surpassed the U.S. Navy in terms of total number of battle force ships sometime between 2015 and 2020. As mentioned earlier in connection with Table 1, however, it is important to keep in mind the differences in composition between the two navies. The U.S. Navy, for example, currently has many more aircraft carriers, nuclear-powered submarines, and cruisers and destroyers, while China’s navy currently has many more diesel attack submarines, frigates, and corvettes.

As noted earlier, DOD stated in the 2021 edition of its annual report on military and security developments involving China that “the PLAN’s overall battle force is expected to grow to 420 ships by 2025 and 460 ships by 2030.”33 The figures of 420 and 460 battle force ships are 20 and 35 ships more, respectively, than the figures of 400 and 425 battle force ships shown for 2025 and 2030 in Table 2. This suggests that between February 2020 (the date of the figures in Table 2) and November 2021 (when the 2021 edition of DOD’s annual report was released), DOD revised upward its projections for 2025 and 2030 for the total number of battle force ships in China’s Navy. Such a revision might reflect an increase in expected construction of new ships, an increase in expected service lives for existing ships, or both.

Table Showing U.S. Navy Figures from October 2020

Table 3 shows numbers of certain types of Chinese navy ships in 2020, and projections of those numbers for 2025, 2030, and 2040, along with the total number of U.S. Navy battle force ships in 2020. The figures for China’s ships were provided by the Navy at the request of CRS. As with

***

33 2021 DOD CMSD, p. 49. See also pp. vi, 48.

p. 10

Table 1, the result for 2020 is an apples-vs.-oranges comparison between the Chinese navy and U.S. navy totals, because the Chinese total for 2020 excludes certain ship types, such as auxiliary and support ships, while the U.S. Navy total for 2020 includes auxiliary and support ships.

As shown in Table 3, the U.S. Navy projects that between 2020 and 2040, the total number of Chinese ships of the types shown in the table will increase by 94, or about 39%, with most of that increase (77 ships out of 94) coming from roughly equal increases in numbers of large surface combatants (cruisers and destroyers—39 ships) and small surface combatants (frigates and corvettes—38 ships). Numbers of ballistic missile submarines and nuclear-powered attack submarines are each projected to more than double between 2020 and 2040, and the total number of diesel attack submarines is projected to remain almost unchanged. The number of large surface combatants is projected to almost double, and the number of small surface combatants is projected to increase by more than one-third. Numbers of larger (LHA- and LPD-type) amphibious ships are projected to increase, and the number of smaller (LST-type) amphibious ships is projected to decline, with the result that the total number of amphibious ships of all kinds is projected to decline slightly.

Selected Elements of China’s Naval Modernization Effort

This section provides a brief overview of elements of China’s naval modernization effort that have attracted frequent attention from observers. … … …

p. 49

Appendix A. Comparing U.S. and Chinese Numbers of Ships and Naval Capabilities

This appendix presents some additional discussion of factors involved in comparing U.S. and Chinese numbers of ships and naval capabilities.

U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities are sometimes compared by showing comparative numbers of U.S. and Chinese ships. Although the total number of ships in a navy (or a navy’s aggregate tonnage) is relatively easy to calculate, it is a one-dimensional measure that leaves out numerous other factors that bear on a navy’s capabilities and how those capabilities compare to its assigned missions. One-dimensional comparisons of the total numbers of ships in China’s navy and the U.S. Navy are highly problematic as a means of assessing relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities and how those capabilities compare to the missions assigned to those navies, for the following reasons:

- A fleet’s total number of ships (or its aggregate tonnage) is only a partial metric of its capability. Many factors other than ship numbers (or aggregate tonnage) contribute to naval capability, including types of ships, types and numbers of aircraft, the sophistication of sensors, weapons, C4ISR systems, and networking capabilities, supporting maintenance and logistics capabilities, doctrine and tactics, the quality, education, and training of personnel, and the realism and complexity of exercises. In light of this, navies with similar numbers of ships or similar aggregate tonnages can have significantly different capabilities, and navy-to-navy comparisons of numbers of ships or aggregate tonnages can provide a highly inaccurate sense of their relative capabilities. In recent years, the warfighting capabilities of navies have derived increasingly from the sophistication of their internal electronics and software. This factor can vary greatly from one navy to the next, and often cannot be easily assessed by outside observation. As the importance of internal electronics and software has grown, the idea of comparing the warfighting capabilities of navies principally on the basis of easily observed factors such as ship numbers and tonnages has become increasingly less reliable, and today is highly problematic.

- Total numbers of ships of a given type (such as submarines or surface combatants) can obscure potentially significant differences in the capabilities of those ships, both between navies and within one country’s navy. Differences in capabilities of ships of a given type can arise from a number of other factors, including sensors, weapons, C4ISR systems, networking capabilities, stealth features, damage-control features, cruising range, maximum speed, and reliability and maintainability (which can affect the amount of time the ship is available for operation).

- A focus on total ship numbers reinforces the notion that changes in total numbers necessarily translate into corresponding or proportional changes in aggregate capability. For a Navy like China’s, which is modernizing by replacing older, obsolescent ships with more modern and more capable ships, this is not necessarily the case. As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, for example, China’s attack submarine force today has only a slightly larger number of boats than it had in 2000 or 2005, but it has considerably more aggregate capability than it did in 2000 or 2005, because the force today includes a much larger percentage of relatively modern designs.

p. 50

- Comparisons of total numbers of ships (or aggregate tonnages) do not take into account the differing global responsibilities and homeporting locations of each fleet.The U.S. Navy has substantial worldwide responsibilities, and a substantial fraction of the U.S. fleet is homeported in the Atlantic. As a consequence, only a certain portion of the U.S. Navy might be available for a crisis or conflict scenario in China’s near-seas region, or could reach that area within a certain amount of time. In contrast, China’s navy has more-limited responsibilities outside China’s near-seas region, and its ships are all homeported along China’s coast at locations that face directly onto China’s near-seas region. In a U.S.-China conflict inside the first island chain, U.S. naval and other forces would be operating at the end of generally long supply lines, while Chinese naval and other forces would be operating at the end of generally short supply lines.

- Comparisons of numbers of ships (or aggregate tonnages) do not take into account maritime-relevant military capabilities that countries might have outside their navies, such as land-based anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), land-based anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), and land-based Air Force aircraft armed with ASCMs or other weapons. Given the significant maritime-relevant non-navy forces present in both the U.S. and Chinese militaries, this is a particularly important consideration in comparing U.S. and Chinese military capabilities for influencing events in the Western Pacific. Although a U.S.-China incident at sea might involve only navy units on both sides, a broader U.S.-China military conflict would more likely be a force-on-force engagement involving multiple branches of each country’s military.

- The missions to be performed by one country’s navy can differ greatly from the missions to be performed by another country’s navy. Consequently, navies are better measured against their respective missions than against one another. Although Navy A might have less capability than Navy B, Navy A might nevertheless be better able to perform Navy A’s intended missions than Navy B is to perform Navy B’s intended missions. This is another significant consideration in assessing U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities, because the missions of the two navies are quite different.

As mentioned earlier, while comparisons of the total numbers of ships in China’s Navy and the U.S. Navy are highly problematic as a means of assessing relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities and how those capabilities compare to the missions assigned to those navies, an examination of the trends over time in the relative numbers of ships can shed some light on how the relative balance of U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities might be changing over time.

Summary

In an era of renewed great power competition, China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, has become the top focus of U.S. defense planning and budgeting. China’s navy, which China has been steadily modernizing for more than 25 years, since the early to mid-1990s, has become a formidable military force within China’s near-seas region, and it is conducting a growing number of operations in more-distant waters, including the broader waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and waters around Europe.

China’s navy is viewed as posing a major challenge to the U.S. Navy’s ability to achieve and maintain wartime control of blue-water ocean areas in the Western Pacific—the first such challenge the U.S. Navy has faced since the end of the Cold War. China’s navy forms a key element of a Chinese challenge to the long-standing status of the United States as the leading military power in the Western Pacific. Some U.S. observers are expressing concern or alarm regarding the pace of China’s naval shipbuilding effort and resulting trend lines regarding the relative sizes and capabilities of China’s navy and the U.S. Navy.

China’s naval modernization effort encompasses a wide array of ship, aircraft, and weapon acquisition programs, as well as improvements in maintenance and logistics, doctrine, personnel quality, education and training, and exercises. China’s navy has currently has certain limitations and weaknesses, and is working to overcome them.

China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, is assessed as being aimed at developing capabilities for addressing the situation with Taiwan militarily, if need be; for achieving a greater degree of control or domination over China’s near-seas region, particularly the South China Sea; for enforcing China’s view that it has the right to regulate foreign military activities in its 200-mile maritime exclusive economic zone (EEZ); for defending China’s commercial sea lines of communication (SLOCs), particularly those linking China to the Persian Gulf; for displacing U.S. influence in the Western Pacific; and for asserting China’s status as the leading regional power and a major world power.

Consistent with these goals, observers believe China wants its navy to be capable of acting as part of a Chinese anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) force—a force that can deter U.S. intervention in a conflict in China’s near-seas region over Taiwan or some other issue, or failing that, delay the arrival or reduce the effectiveness of intervening U.S. forces. Additional missions for China’s navy include conducting maritime security (including antipiracy) operations, evacuating Chinese nationals from foreign countries when necessary, and conducting humanitarian assistance/disaster response (HA/DR) operations.

The U.S. Navy in recent years has taken a number of actions to counter China’s naval modernization effort. Among other things, the U.S. Navy has shifted a greater percentage of its fleet to the Pacific; assigned its most-capable new ships and aircraft and its best personnel to the Pacific; maintained or increased general presence operations, training and developmental exercises, and engagement and cooperation with allied and other navies in the Indo-Pacific; increased the planned future size of the Navy; initiated, increased, or accelerated numerous programs for developing new military technologies and acquiring new ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles, and weapons; begun development of new operational concepts (i.e., new ways to employ Navy and Marine Corps forces) for countering Chinese maritime A2/AD forces; and signaled that the Navy in coming years will shift to a more-distributed fleet architecture that will feature a smaller portion of larger ships, a larger portion of smaller ships, and a substantially greater use of unmanned vehicles. The issue for Congress is whether the U.S. Navy is responding appropriately to China’s naval modernization effort.

*** *** ***

ADDITIONAL SPECIFIC DETAILS FROM RECENT VERSION OF REPORT:

Ronald O’Rourke, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, RL33153 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 9 March 2021).

Having trouble accessing the website above? Please download a cached copy here!

You can also click here to access the report via the public CRS website.

p. 5

Anti-Ship Missiles

Anti-Ship Ballistic Missiles

China reportedly is fielding two types of land-based ballistic missiles with a capability of hitting ships at sea—the DF-21D (Figure 1), a road-mobile anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) with a range of more than 1,500 kilometers (i.e., more than 910 nautical miles), and the DF-26 (Figure 2), a road-mobile, multi-role intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) with a maximum range of about 4,000 kilometers (i.e., about 2,160 nautical miles) that DOD says “is capable of conducting both conventional and nuclear precision strikes against ground targets as well as conventional strikes against naval targets.”21

Until recently, reported test flights of DF-21s and SDF-26s have not involved attempts to hit moving ships at sea. A November 14, 2020, press report, however, stated that an August 2020 test firing of DF-21 and DF-26 ASBMs into the South China resulted in the missiles successfully hitting a moving target ship south of the Paracel Islands.22 A December 3, 2020, press report stated that Admiral Philip Davidson, the commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, “confirmed, for the first time from the U.S. government side, that China’s People’s Liberation Army has successfully tested an anti-ship ballistic missile against a moving ship.”23 China reportedly is also

***

21 2020 DOD CMSD, p. 55.

22 Kristin Huang, “China’s ‘Aircraft-Carrier Killer’ Missiles Successfully Hit Target Ship in South China Sea, PLA Insider Reveals,” South China Morning Post, November 1,4 2020. See also Peter Suciu, “Report: China’s ‘Aircraft- Carrier Killer’ Missiles Hit Target Ship in August,” National Interest, November 15, 2020; Andrew Erickson, “China’s DF-21D and DF-26B ASBMs: Is the U.S. Military Ready?” Real Clear Defense, November 16, 2020.

23 Josh Rogin, “China’s Military Expansion Will Test the Biden Administration,” Washington Post, December 3, 2020.

p. 6

developing hypersonic glide vehicles that, if incorporated into Chinese ASBMs, could make Chinese ASBMs more difficult to intercept.24

Observers have expressed strong concerns about China’s ASBMs, because such missiles, in combination with broad-area maritime surveillance and targeting systems, would permit China to attack aircraft carriers, other U.S. Navy ships, or ships of allied or partner navies operating in the Western Pacific. The U.S. Navy has not previously faced a threat from highly accurate ballistic missiles capable of hitting moving ships at sea. For this reason, some observers have referred to ASBMs as a “game-changing” weapon.

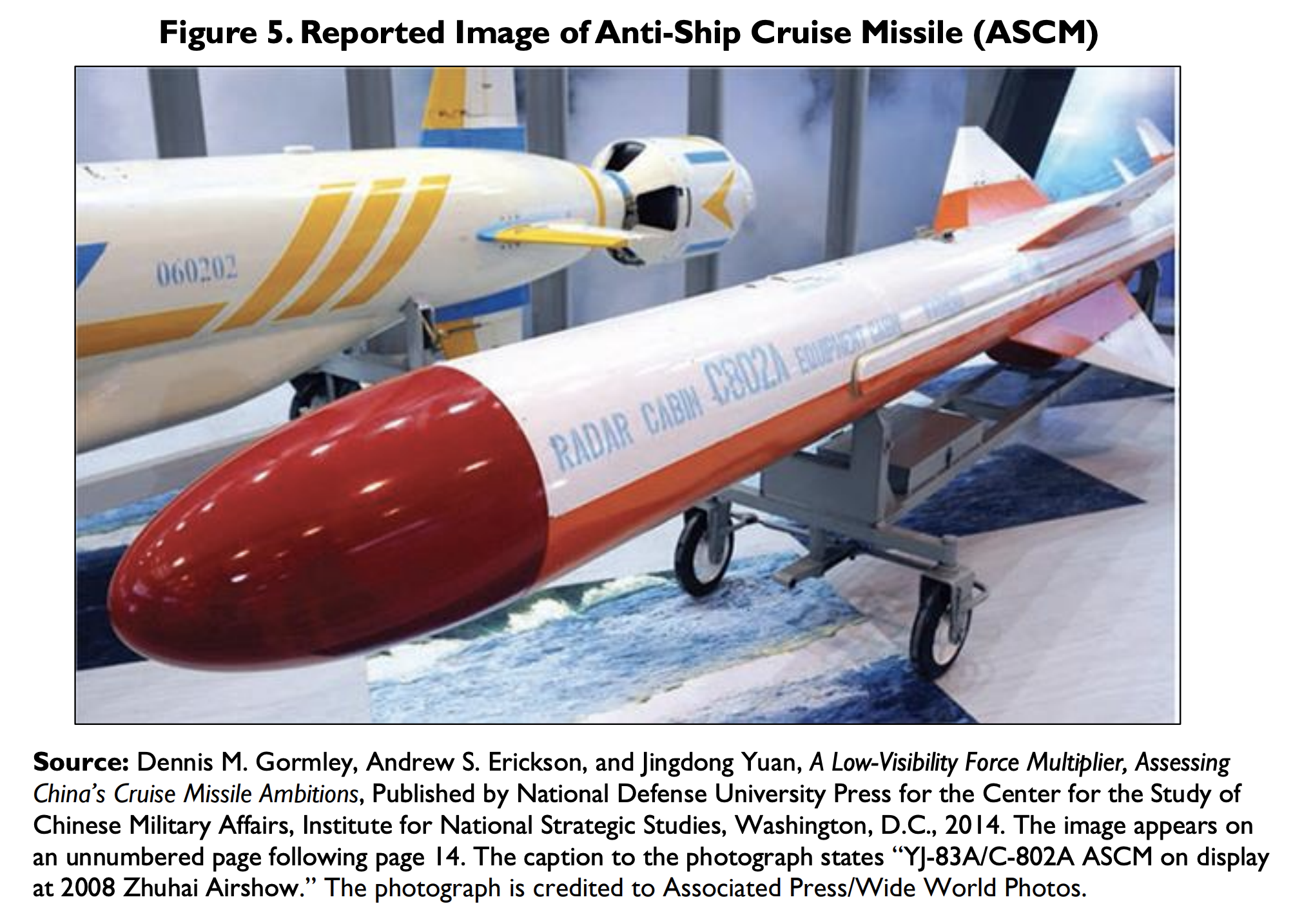

Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs)

China’s extensive inventory of anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) (see Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5 for examples of reported images) includes both Russian- and Chinese-made designs, including some advanced and highly capable ones, such as the Chinese-made YJ-18.25 Although China’s ASCMs do not always receive as much press attention as China’s ASBMs (perhaps because ASBMs are a more-recent development), observers are nevertheless concerned about them. As discussed later in this report, the relatively long ranges of certain Chinese ASCMs have led to concerns among some observers that the U.S. Navy is not moving quickly enough to arm U.S. Navy surface ships with similarly ranged ASCMs.

***

24 See, for example, Christian Davenport, “Why the Pentagon Fears the U.S. Is Losing the Hypersonic Arms Race with Russia and China,” Washington Post, June 8, 2018; Keith Button, “Hypersonic Weapons Race,” Aerospace America, June 2018.

25 2020 DOD CMSD, p. 59.

p. 8

Submarines

Overview

China has been steadily modernizing its submarine force, and most of its submarines are now built to relatively modern Chinese and Russian designs. Qualitatively, China’s newest submarines might not be as capable as Russia’s newest submarines,26 but compared to China’s earlier submarines, which were built to antiquated designs, its newer submarines are much more capable.

Types and Numbers

Most of China’s submarines are non-nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSs). China also operates a small number of nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) and a small number of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). The number of SSNs and SSBNs may grow in coming years, but the force will likely continue to consist mostly of SSs. DOD states that

***

26 Observers have sometimes characterized Russia’s submarines rather than China’s as being the most capable faced by the U.S. Navy. See, for example, Joe Gould and Aaron Mehta, “US Could Lose a Key Weapon for Tracking Chinese and Russian Subs,” Defense News, May 1, 2019; Dave Majumdar, “Why the U.S. Navy Fears Russia’s Submarines,” National Interest, October 12, 2018; John Schaus, Lauren Dickey, and Andrew Metrick, “Asia’s Looming Subsurface Challenge,” War on the Rocks, August 11, 2016; Paul McLeary, “Chinese, Russian Subs Increasingly Worrying the Pentagon,” Foreign Policy, February 24, 2016; Dave Majumdar, “U.S. Navy Impressed with New Russian Attack Boat,” USNI News, October 28, 2014.

p. 9

“The PLAN will likely maintain between 65 and 70 submarines through the 2020s, replacing older units with more capable units on a near one-to-one basis.”27 ONI states that “China’s submarine force continues to grow at a low rate, though with substantially more-capable submarines replacing older units. Current expansion at submarine production yards could allow higher future production numbers.” ONI projects that China’s submarine force will grow from a total of 66 boats (4 SSBNs, 7 SSNs, and 55 SSs) in 2020 to 76 boats (8 SSBNs, 13 SSNs, and 55 SSs) in 2030.28

China’s newest series-built SS design is the Yuan-class (Type 039) SS (Figure 6), its newest SSN class is the Shang-class (Type 093) SSN (Figure 7), and its newest SSBN class is the Jin (Type 094) class SSBN (Figure 8). In May 2020, it was reported that two additional Type 094 SSBNs had entered service, increasing the total number in service to six.29

DOD states that since the mid-1990s, “China’s shipyards have delivered 13 Song class SS units (Type 039) and 17 Yuan class diesel-electric air-independent-powered attack submarine (SSP)

***

27 2020 DOD CMSD, p. 45.

28 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 1. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission. See also H. I. Sutton, “China Increases Production of AIP Submarines With Massive New Shipyard,” Naval News, February 16, 2021; H. I. Sutton, “First Image Of China’s New Nuclear Submarine Under Construction,” Naval News, February 1, 2021.

29 See, for example, Peter Suciu, “China Now Has Six Type 094A Jin-Class Nuclear Powered Missile Submarines,” National Interest, May 6, 2020.

p. 10

(Type 039A/B). The PRC is expected to produce a total of 25 or more Yuan class submarines by 2025.”30 DOD states further:

Over the past 15 years, the PLAN has constructed twelve nuclear submarines—two Shang I class SSNs (Type 093), four Shang II class SSNs (Type 093A), and six Jin class SSBNs (Type 094), two of which were awaiting entry into service in late 2019. Equipped with the CSS-N-14 (JL-2) submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), the PLAN’s four operational Jin class SSBNs represent the PRC’s first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent. Each Jin class SSBN can carry up to 12 JL-2 SLBMs….China’s next-generation Type 096 SSBN, which will likely begin construction in the early-2020s, will reportedly carry a new type of SLBM. The PLAN is expected to operate the Type 094 and Type 096 SSBNs concurrently and could have up to eight SSBNs by 2030….

By the mid-2020s, China will likely build the Type 093B guided-missile nuclear attack submarine. This new Shang class variant will enhance the PLAN’s anti-surface warfare capability and could provide a clandestine land-attack option if equipped with land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs).”31

Submarine Weapons

China’s submarines are armed with one or more of the following: ASCMs, wire-guided and wake-homing torpedoes, and mines. Wake-homing torpedoes can be very difficult for surface

***

30 2020 DOD CMSD, p. 45.

31 2020 DOD CMSD, p. 45.

p. 11

ships to decoy. Each Jin-class SSBN is armed with 12 JL-2 nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs).32

***

32 DOD estimates the range of the JL-2 at 7,200 km (2020 DOD CMSD, p. 58). Such a range could permit Jin-class SSBNs to attack targets in Alaska (except the Alaskan panhandle) from protected bastions close to China, targets in Hawaii (as well as targets in Alaska, except the Alaskan panhandle) from locations south of Japan, targets in the western half of the 48 contiguous states (as well as Hawaii and Alaska) from mid-ocean locations west of Hawaii, or targets in all 50 states from mid-ocean locations east of Hawaii.

p. 17

Surface Combatants

Overview

China since the early 1990s has put into service numerous new classes of indigenously built surface combatants, including a new cruiser (or large destroyer), several classes of destroyers and frigates, a new class of corvettes (i.e., light frigates), and a new class of missile-armed patrol craft.

These new classes of surface combatants demonstrate a significant modernization of PLA Navy surface combatant technology. DOD states that China’s navy “remains engaged in a robust shipbuilding program for surface combatants, producing new guided-missile cruisers (CGs), guided-missile destroyers (DDGs) and corvettes (FFLs). These assets will significantly upgrade the air defense, anti-ship, and anti-submarine capabilities of China’s navy and will be critical as China’s navy expands its operations beyond the range of the PLA’s shore-based air defense systems.”50 DIA states that “the era of past designs has given way to production of modern multimission destroyer, frigate, and corvette classes as China’s technological advancement in naval design has begun to approach a level commensurate with, and in some cases exceeding, that of other modern navies.”51 China is also upgrading its older surface combatants with new weapons and other equipment.52

Type 055 Cruiser/Large Destroyer

***

50 2020 DOD CMSD, pp. 45-46. 51 2019 DIA CMP, p. 70.

52 See, for example, H. I. Sutton, “China Increases Potency Of Anti-Carrier Capabilities,” Forbes, May 1, 2020; Peter Suciu, “Chinese Warships Are Now Armed with Supersonic Anti-Ship Missiles,” National Interest, May 10, 2020.

53 For a discussion of the Type 055 design, see Sidharth Kaushal, “The Type 055: A Glimpse into the PLAN’s Developmental Trajectory,” Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), October 19, 2020.

p. 18

7, 2021, press report by a Chinese media outlet states that the ship displaces more than 12,000 tons.54 By way of comparison, the U.S. Navy’s Ticonderoga (CG-47) class cruisers and Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class destroyers (aka the U.S. Navy’s Aegis cruisers and destroyers) displace about 10,100 tons and 9,300 tons, respectively, while the U.S. Navy’s three Zumwalt (DDG- 1000) class destroyers displace about 15,600 tons.

ONI states that Type 055 ships are being built by two shipyards, and that multiple ships in the class are currently under construction.55 The first Type 055 ship was reportedly commissioned into service on January 12, 2020, about two and a half years after it was launched (i.e., put into the water for the final stages of its construction). A March 7, 2021, press report from a Chinese media outlet stated that the second ship in the class had recently been commissioned into service.56 The sixth ship in the class was reportedly launched in December 2019.57 In August 2020, it was reported that the seventh ship in the class was delivered to the navy in May 2020,58

***

54 Liu Xuanzun, “China’s 2nd Type 055 Large Destroyer Enters Naval Service,” Global Times, March 7, 2021.

55 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

56 Liu Xuanzun, “China’s 2nd Type 055 Large Destroyer Enters Naval Service,” Global Times, March 7, 2021. See also Xavier Vavasseur, “China’s 2nd Type 055 Destroyer ‘Lhasa’ 拉萨 Commissioned With PLAN,” Naval News, March 7, 2021.

57 Kristin Huang, “China Steps Up Warship Building Programme as Navy Looks to Extend Its Global Reach,” South China Morning Post, December 31, 2019. See also Liu Xuanzun, “Chinese Navy Commissions First Type 055 Destroyer,” Global Times, January 12, 2020. Another press report states that eight Type 055 ships are expected to enter service over the next four years, and that more than two dozen such ships might be in service by the late 2020s. (Franz-Stefan Gady, “China’s Navy Commissions First-of-Class Type 055 Guided Missile Destroyer,” Diplomat, January 13, 2020.)

58 Minnie Chan, “Chinese Navy May Launch Eighth Type 055 Stealth Destroyer Later This Year,” South China Morning Post, August 20, 2020.

p. 19

that the eighth ship in the class was launched on August 30, 2020,59 and that the eighth ship “will complete the first group of Type 055 destroyers.”60

Type 052 Destroyer

China since the early 1990s has put into service multiple new classes of indigenously built destroyers, the most recent of which is the Luyang III (Type 052D) class (Figure 15), which displaces about 7,500 tons and is equipped with phased-array radars and vertical launch missile systems that outwardly are broadly similar to those on U.S. Navy cruisers and destroyers. Type 052D ships have been in serial production for some time, and the 25th such ship was reportedly launched on August 30, 2020.61 One observer states that “at present the PLAN fields 20 aegis- type [i.e., Type 052] destroyers in service; however in four to five years it is likely that the PLAN will field 39 aegis-type destroyers in service (or 40, depending on whether a 26th 052D is built or not).”62 Press reports in March 2021 stated that China is now commissioning an upgraded version

***

59 Liu Xuanzun, “PLA Launches New Type 055, Type 052D Destroyers After Decommissioning All Type 051 Destroyers: Reports,” Global Times, August 30, 2020.

60 Minnie Chan, “Chinese Navy May Launch Eighth Type 055 Stealth Destroyer Later This Year,” South China Morning Post, August 20, 2020. See also Peter Suciu, “Chinese Navy to Launch 8th New Type 055 ‘Stealth’ Destroyer,” National Interest, August 22, 2020. A November 18, 2020, press report that cited a November 16, 2020, Chinese-language press report stated that “China’s Type 055 destroyer is equipped with a microwave anti-missile system which can disable the electronic equipment of incoming enemy aircraft and missiles, and even burn the enemy’s pilots.” (“China Uses Microwave Weapons against India,” Chinascope, November 18, 2020, which cited the following as its source: “Lianhe Zaobao, November 16, 2020, https://www.zaobao.com.sg/realtime/china/story20201116- 1101404.”)

61 Liu Xuanzun, “PLA Launches New Type 055, Type 052D Destroyers After Decommissioning All Type 051 Destroyers: Reports,” Global Times, August 30, 2020.

62 Rick Joe, “The Chinese Navy’s Destroyer Fleet Will Double by 2025. Then What?” Diplomat, July 12, 2020. See

p. 20

of the Type 052D, informally called the Type 052DL, that incorporates an extended-length helicopter flight deck and a new radar.63

***

also Kris Osborn, “Double the Destroyers: China Will Soon Have Almost 40 of These Modern Warships,” National Interest, July 17, 2020.

63 “Chinese Navy Commissions Upgraded Variation of the Type 052D Destroyer,” Navy Recognition, March 3, 2021.

p. 27

Operations Away from Home Waters

Although China’s navy operates primarily in China’s home waters, Chinese navy ships are conducting increasing numbers of operations away from China’s home waters, including the broader waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and the waters surrounding Europe, including the Mediterranean Sea and the Baltic Sea. A November 23, 2019, DOD news report quoted Admiral Philip Davidson, the commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, as stating that China’s navy had conducted more global naval deployments in the past 30 months than it had in the previous 30 years.77

While many of China’s long-distance naval deployments have been for making diplomatic port calls, some of them have been for other purposes, including conducting training exercises and carrying out antipiracy operations in waters off Somalia. China has been conducting antipiracy operations in waters off Somalia since December 2008 via a succession of more than 30 rotationally deployed naval escort task forces. China’s distant naval operations are supported in part by China’s military base in Djibouti, which China officially opened in August 2017 as its first overseas military base.78