O’Rourke’s Latest CRS Report—“China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities”—USG/N Info on PLAN Ships & Projections of #s Lead thru 2040

Latest and greatest…with many references to CMSI reports, including the Quick Look Summary from, and revised versions of papers presented at, our 11-13 April 2023 Conference—“Chinese Undersea Warfare: Development, Capabilities, Trends”! As part of Ronald O’Rourke’s continuous incremental improvements, this # 26X (!) edition of his report on PRC naval modernization incorporates numbers provided by the U.S. Navy. Given the authoritative analysis supporting these revelations, and the rarity with which they are made publicly available in this manner, they are all worth reading carefully in full!

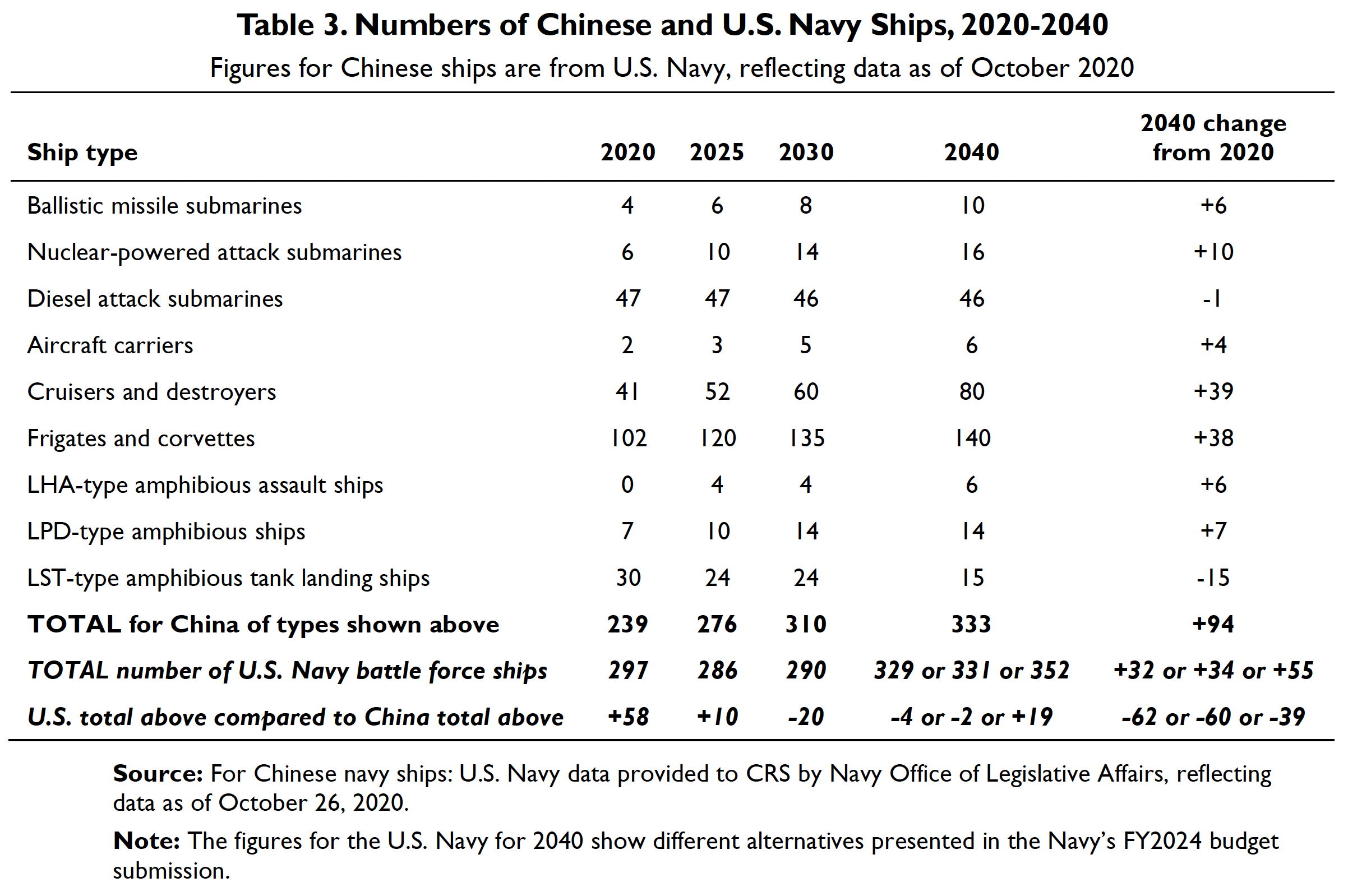

Bottom line up front: here’s the key table (p. 11):

By 2040, the PLA Navy is thus projected to have the following:

- Ballistic missile submarines (SSBN): 10 (+6)

- Nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSN): 16 (+10)

- Diesel attack submarines (SSK): 46 (-1)

- Aircraft carriers (CV): 6 (+4)

- Cruisers and destroyers (CG & DDG): 80 (+39)

- Frigates and corvettes (FFG & FFL): 140 (+38)

- Amphibious Assault Ship-type amphibious ships (LHA): 6 (+6)

- Amphibious Transport Dock-type amphibious ships 14 (LPD): (+7)

- Tank Landing Ship-type amphibious ships (LST): 15 (-15)

- TOTAL of above-mentioned types: 333 (+94)

Ronald O’Rourke, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, RL33153 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 5 October 2023).

Having trouble accessing the website above? Please download a cached copy here!

You can also click here to access the report via the public CRS website.

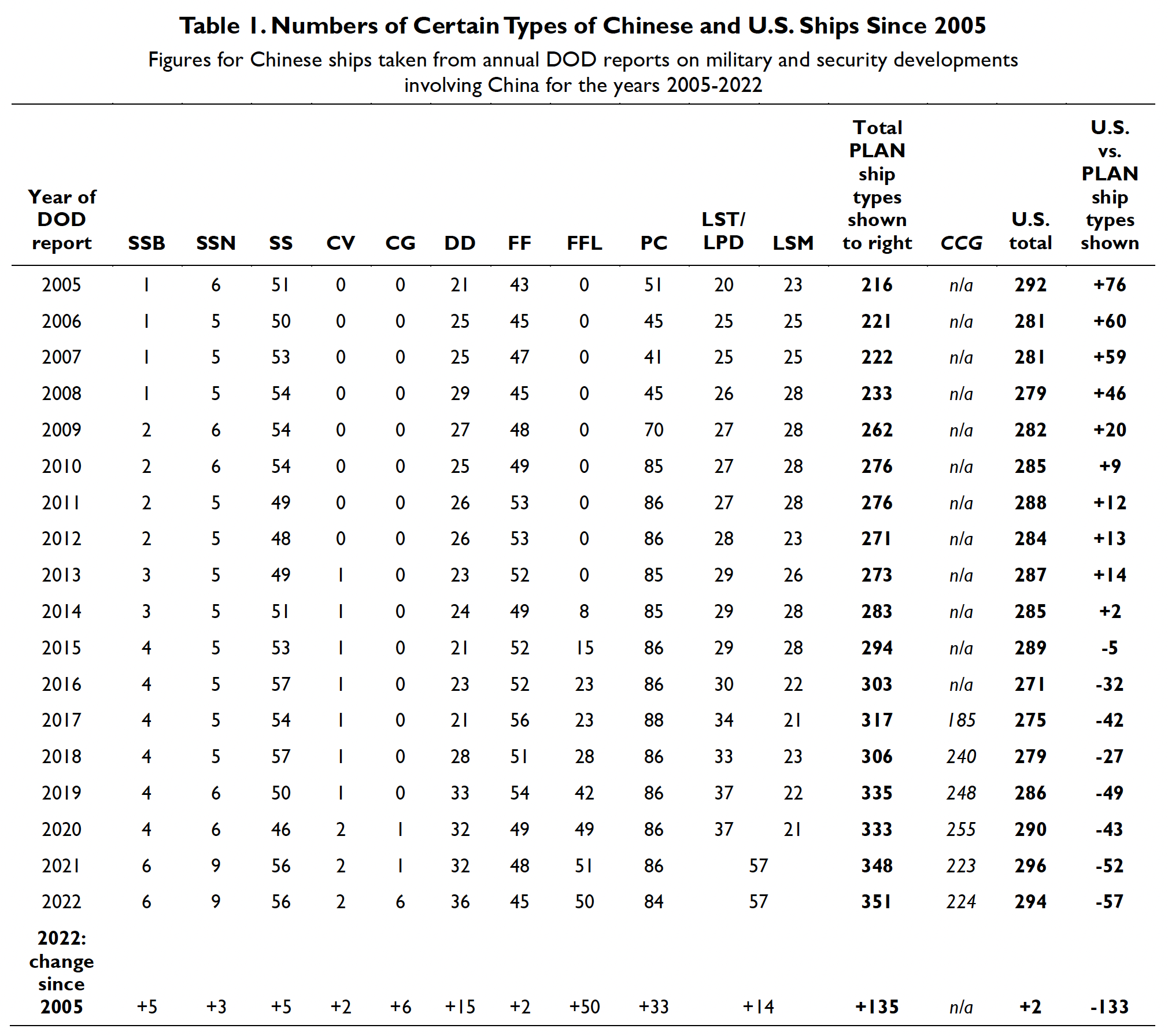

Here’s another important table (p. 9):

Note from me (Andrew Erickson): The U.S. Navy is duty bound to count PLA Navy ship numbers strictly according to the criteria listed in SECNAVINST 5030.8C (“General Guidance for the Classification of Naval Vessels and Battle Force Ship Counting Procedures”). The resulting battle force numbers calculated for China therefore correspond numerically with those for the U.S. Navy battle force. To be sure, aspects of the analysis and implications can be complex in practice, and O’Rourke offers thoughtful explanations and implications in his frequently-updated report.

Further references:

- United States Navy ships

- U.S. Navy Ships – Index

- List of naval ship classes in service

- Nomenclature of Naval Vessels

Now, back to the specific contents of O’Rourke’s report…

p. 1

Introduction

Issue for Congress

This report provides background information and issues for Congress on China’s naval modernization effort and its implications for U.S. Navy capabilities. China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, is the top focus of U.S. defense planning and budgeting.1 The issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Biden Administration’s proposed U.S. Navy plans, budgets, and programs for responding to China’s naval modernization effort. Congress’s decisions on this issue could affect U.S. Navy capabilities and funding requirements, and the U.S. defense industrial base.

Sources and Terminology

This report is based on unclassified open-source information, such as the annual Department of Defense (DOD) report to Congress on military and security developments involving China,2 a 2019 Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) report on China’s military power,3 a 2015 Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) report on China’s navy,4 published reference sources such as IHS Jane’s Fighting Ships,5 and press reports.

For convenience, this report uses the term China’s naval modernization effort to refer to the modernization not only of China’s navy, but also of Chinese military forces outside China’s navy that can be used to counter U.S. naval forces operating in the Western Pacific, such as land-based anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), land-based surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), land-based Air Force aircraft armed with anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), and land-based long-range radars for detecting and tracking ships at sea.

***

1 For an overview of China’s military, see CRS Report R46808, China’s Military: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), by Caitlin Campbell. For more on China’s military modernization effort being the top focus of U.S. defense planning and budgeting, see CRS Report R43838, Great Power Competition: Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

2 Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022, Annual Report to Congress, released on November 29, 2022, 174 pp. Hereinafter 2022 DOD CMSD.

3 Defense Intelligence Agency, China Military Power, Modernizing a Force to Fight and Win, 2019, 125 pp. Hereinafter 2019 DIA CMP.

4 Office of Naval Intelligence, The PLA Navy, New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century, undated but released in April 2015, 47 pp.

5 IHS Jane’s Fighting Ships 2021-2022, and previous editions.

p. 2

Background

Brief Overview of China’s Naval Modernization Effort

Key overview points concerning China’s naval modernization effort include the following:

- China’s naval modernization effort, which forms part of a broader Chinese military modernization effort that includes several additional areas of emphasis,7 has been underway for about 30 years, since the early to mid-1990s, and has transformed China’s navy into a much more modern and capable force.

- China’s navy is a formidable military force within China’s near-seas region, and it is conducting a growing number of operations in more-distant waters, including the broader waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and waters around Europe.

- China’s navy is, by far, the largest of any country in East Asia, and as shown in Table 2, sometime between 2015 and 2020, China’s navy surpassed the U.S. Navy in numbers of battle force ships (meaning the types of ships that count toward the quoted size of the U.S. Navy), making China’s navy the numerically largest in the world. DOD states that “the PLAN is the largest navy in the world with a battle force of approximately 340 platforms, including major surface combatants, submarines, ocean-going amphibious ships, mine warfare ships, aircraft carriers, and fleet auxiliaries…. This figure does not include approximately 85 patrol combatants and craft that carry anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM). The PLAN’s overall battle force is expected to grow to 400 ships by 2025 and 440 ships by 2030. Much of this growth will be in major surface combatants.”8 The U.S. Navy, by comparison, included 290 battle force ships as of October 5, 2023, and the Navy’s FY2024 budget submission projects that the Navy will include 290 battle force ships by the end of FY2030.9

- U.S. military officials and other observers are expressing concern or alarm regarding the pace of China’s naval shipbuilding effort, the capacity of China’s shipbuilding industry compared with the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry, and resulting trend lines regarding the relative sizes and capabilities of China’s navy and the U.S. Navy.10 China’s navy is viewed as posing a major

***

7 Other areas of emphasis in China’s military modernization effort include space capabilities, cyber and electronic warfare capabilities, ballistic missile forces, and aviation forces, as well as the development of emerging military-applicable technologies such as hypersonics, artificial intelligence, robotics and unmanned vehicles, directed-energy technologies, and quantum technologies. For more on China’s military modernization effort in general, see CRS Report R46808, China’s Military: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), by Caitlin Campbell. For a discussion of advanced military technologies, see CRS In Focus IF11105, Defense Primer: Emerging Technologies, by Kelley M. Sayler. U.S.-China competition in military capabilities in turn forms one dimension of a broader U.S.-China strategic competition that also includes political, diplomatic, economic, technological, and ideological dimensions.

8 2022 DOD CMSD, p. 52. See also 2019 DIA CMP, p. 63.

9 For additional discussion, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

10 See, for example, Michael Lee, “Chinese Shipbuilding Capacity Over 200 Times Greater Than US, Navy Intelligence Says,” Fox News, September 14, 2023; Joseph Trevithick, “Alarming Navy Intel Slide Warns Of China’s 200 Times Greater Shipbuilding Capacity,” The Drive, July 11, 2023; Chris Bradford, “Point of No Return, US Navy Faces Being Totally Outgunned by China in Just Seven Years—We Need a Fleet Ready to Fight War Now, Says Expert,” U.S. Sun, March 1, 2023; Keith Griffith, “China’s Naval Fleet Is Growing and the US ‘Can’t Keep Up’ with

(continued…)

p. 3

- challenge to the U.S. Navy’s ability to achieve and maintain wartime control of blue-water ocean areas in the Western Pacific—the first such challenge the U.S. Navy has faced since the end of the Cold War. China’s navy forms a key element of a Chinese challenge to the long-standing status of the United States as the leading military power in the Western Pacific.

- China’s naval ships, aircraft, and weapons are much more modern and capable than they were at the start of the 1990s, and are comparable in many respects to those of Western navies. DOD states that “as of 2021, the PLAN is largely composed of modern multi-role platforms featuring advanced anti-ship, anti-air, and anti-submarine weapons and sensors.”11 ONI states that “Chinese naval ship design and material quality is in many cases comparable to [that of] USN [U.S. Navy] ships, and China is quickly closing the gap in any areas of deficiency.”12

- China’s naval modernization effort encompasses a wide array of platform and weapon acquisition programs, including anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), submarines, surface ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles (UVs),13 and supporting C4ISR (command and control,

***

the Warship Buildup as Beijing Uses Its Sea Power to Project an ‘Increasingly Aggressive Military Posture Globally,’ Navy Secretary Warns,” Daily Mail (UK), February 23, 2023; Brad Lendon and Haley Britzky, “US Can’t Keep Up with China’s Warship Building, Navy Secretary Says,” CNN, February 22, 2023; Meredith Roaten, “Shipyard Capacity, China’s Naval Buildup Worries U.S. Military Leaders,” National Defense, January 26, 2023; Oliver Parken and Tyler Rogoway, “Extremely Ominous Warning About China From US Strategic Command Chief, Admiral Richard Says ‘The Big One’ with China Is Coming and the ‘Ship Is Slowly Sinking’ in Terms of U.S. Deterrence,” The Drive, November 6, 2022; Xiaoshan Xue, “As China Expands Its Fleets, US Analysts Call for Catch-up Efforts,” VOA, September 13, 2022; Aidan Quigley, “Chinese Navy Narrowing Capability Gap with U.S., Analysts Say,” Inside Defense, November 16, 2021; Alex Hollings, “Just How Big Is China’s Navy? Bigger Than You Think,” Sandboxx, July 28, 2021; Kyle Mizokami, “China Just Commissioned Three Warships in a Single Day, That’s Almost Half as Many as the U.S. Will Induct in One Year,” Popular Mechanics, April 27, 2021; Geoff Ziezulewicz, “China’s Navy Has More Ships than the US. Does That Matter?” Navy Times, April 9, 2021; Dan De Luce and Ken Dilanian, “China’s Growing Firepower Casts Doubt on Whether U.S. Could Defend Taiwan, In War Games, China Often Wins, and U.S. Warships and Aircraft Are Kept at Bay,” NBC News, March 27, 2021; Brad Lendon, “China Has Built the World’s Largest Navy. Now What’s Beijing Going to Do with It?” CNN, March 5, 2021; Andrew S. Erickson, “A Guide to China’s Unprecedented Naval Shipbuilding Drive,” Maritime Executive, February 11, 2021; Stephen Kuper, “Beijing Steps Up Naval Shipbuilding Program with Eyes on Global Navy,” Defence Connect, January 11, 2021; James E. Fanell, “China’s Global Navy—Today’s Challenge for the United States and the U.S. Navy,” Naval War College Review, Autumn 2020, 32 pp.; Ryan Pickrell, “China Is the World’s Biggest Shipbuilder, and Its Ability to Rapidly Produce New Warships Would Be a ‘Huge Advantage’ in a Long Fight with the US, Experts Say,” Business Insider, September 8, 2020; Ryan D. Martinson, “Deciphering China’s ‘World-Class’ Naval Ambitions,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, August 2020; Dave Makichuk, “China’s Navy Shipbuilders Are ‘Outbuilding Everybody,’” Asia Times, March 11, 2020; Jon Harper, “Eagle vs Dragon: How the U.S. and Chinese Navies Stack Up,” National Defense, March 9, 2020; H. I. Sutton, “The Chinese Navy Is Building An Incredible Number Of Warships,” Forbes, December 15, 2019; Nick Childs and Tom Waldwyn, “China’s Naval Shipbuilding: Delivering on Its Ambition in a Big Way,” International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), May 1, 2018; James R. Holmes and Toshi Yoshihara, “Taking Stock of China’s Growing Navy: The Death and Life of Surface Fleets,” Orbis, Spring 2017: 269-285.

For articles offering differing perspectives, see, for example, David Axe, “The Chinese Navy Can’t Grow Forever—The Slowdown Might Start Soon,” Forbes, November 12, 2020; Mike Sweeney, Assessing Chinese Maritime Power, Defense Priorities, October 2020, 14 pp.

11 2022 DOD CMSD, p. 50.

12 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 3. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

13 See, for example, H. I. Sutton, “China Reveals New Heavily Armed Extra-Large Uncrewed Submarine,” Naval News, February 23, 2023; Ryan Martinson, “Gliders With Ears: A New Tool in China’s Subsea Surveillance Toolbox,”

(continued…)

p. 4

- communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems. China’s naval modernization effort also includes improvements in logistics, doctrine, personnel quality, education and training, and exercises.14

- China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, is assessed as being aimed at developing capabilities for, among other things, addressing the situation with Taiwan militarily, if need be; achieving a greater degree of control or domination over China’s near-seas region, particularly the South China Sea; enforcing China’s view that it has the right to regulate foreign military activities in its 200-mile maritime exclusive economic zone (EEZ);15 defending China’s commercial sea lines of communication (SLOCs), particularly those linking China to the Persian Gulf; displacing U.S. influence in the Western Pacific; and asserting China’s status as the leading regional power and a major world power.16 Additional missions for China’s navy include conducting maritime security (including antipiracy) operations, evacuating Chinese nationals from foreign countries when necessary, and conducting humanitarian assistance/disaster response (HA/DR) operations.

- Observers believe China wants its navy to be capable of acting as part of an anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) force—a force that can deter U.S. intervention in a conflict in China’s near-seas region over Taiwan or some other issue, or failing that, delay the arrival or reduce the effectiveness of intervening U.S. forces.

- The planned ultimate size and composition of China’s navy is not publicly known. In contrast to the U.S. Navy, China does not release a navy force-level goal or detailed information about planned ship procurement rates, planned total ship procurement quantities, planned ship retirements, and resulting projected force levels.

- Although China’s naval modernization effort has substantially improved China’s naval capabilities, China’s navy currently is assessed as having limitations or weaknesses in certain areas,17 including joint operations with other parts of China’s military,18 anti-submarine warfare (ASW), long-range targeting, a limited capacity for carrying out at-sea resupply of combatant ships operating far from

***

Maritime Executive, March 21, 2022; Gabriel Honrada, “Underwater Drones Herald Sea Change in Pacific Warfare,” Asia Times, January 12, 2022.

Ryan Fedasiuk, “Leviathan Wakes: China’s Growing Fleet of Autonomous Undersea Vehicles,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), August 17, 2021.

14 See, for example, Roderick Lee, “The PLA Navy’s ZHANLAN Training Series: Supporting Offensive Strike on the High Seas,” China Brief, April 13, 2020.

15 For additional discussion, see CRS Report R42784, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

16 For additional discussion, see Ryan D. Martinson, “Deciphering China’s ‘World-class’ Naval Ambitions,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, August 2020.

17 For a discussion focusing on these limitations or weaknesses, see Mike Sweeney, Assessing Chinese Maritime Power, Defense Priorities, October 2020, 14 pp. See also Tai Ming Cheung, “Russia’s Ukraine Disaster Exposes China’s Military Weakness,” Foreign Policy, October 24, 2022.

18 See, for example, Ben Noon and Chris Bassler, “Schrodinger’s Military? Challenges for China’s Military Modernization Ambitions,” War on the Rocks, October 14, 2021.

p. 5

19 See, for example, Felix K. Chang, “Sustaining the Chinese Navy’s Operations at Sea: Bigger Fists, Growing Legs,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, May 3, 2023; Will Mackenzie, “Commentary: It’s the Logistics, China,” National Defense, June 10, 2020.

20 See, for example, Kristin Huang, “Size of China’s Navy May Be Closing Gap on US Fleet But What Can the PLA Do with Just One Overseas Naval Base?” South China Morning Post, March 14, 2021.

21 See, for example, Minnie Chan, “China’s Navy Goes Back to Work on Big Ambitions but Long-Term Gaps Remain,” South China Morning Post, August 22, 2020. See also Mallory Shelbourne, “At-Sea Political Officers Could Pose Problems for Chinese Navy in War, Experts Say,” USNI News, September 20, 2023.

22 Alastair Gale, “China’s Military Is Catching Up to the U.S. Is It Ready for Battle?” Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2022; Benjamin Brimelow, “China’s Military Is Growing Rapidly, But It Hasn’t Been ‘Tested’ Like US Troops Have, Former Top US Admiral Says,” Business Insider, March 29, 2022. See also Andrew Scobell, “Xi Jinping’s Worst Nightmare: A Potemkin People’s Liberation Army,” War on the Rocks, May 1, 2023.

The use of a dual command structure in the crews of larger Chinese ships, involving both a commanding officer and a political officer, has been raised as a source of potential reduced command effectiveness in certain tactical situations. See Mallory Shelbourne, “At-Sea Political Officers Could Pose Problems for Chinese Navy in War, Experts Say,” USNI News, September 20, 2023; Roderick Lee, PLA Navy Submarine Leadership – Factors Affecting Operational Performance, China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI), U.S. Naval War College, June 2023, 21 pp.

“Leadership: China Cripples Naval Officers,” Strategy Page, July 18, 2020.

Some observers argue that corruption in China’s shipbuilding companies may be a source of weaknesses in China’s naval modernization effort. See, for example, Zi Yang, “The Invisible Threat to China’s Navy: Corruption,” Diplomat, May 19, 2020. See also Bloomberg News, “China’s Military Probes Slew of Graft Issues Going Back to 2017,” Bloomberg, July 26, 2023; Gordan G. Chang, “China’s Military Is Nowhere Near as Strong as the CCP Wants You to Think,” Newsweek, June 16, 2023; Frank Chen, “Ex-PLA Navy Chief in Deep Water Amid War on Graft,” Asia Times, June 26, 2020.

23 For example, China’s naval shipbuilding programs were previously dependent on foreign suppliers for some ship components. ONI, however, states that “almost all weapons and sensors on Chinese naval ships are produced in-country, and China no longer relies on Russia or other countries for any significant naval ship systems.” (Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, pp. 2-3. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.) Regarding the ASW capabilities of China’s Navy, DOD states

The PLAN is also improving its anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities through the development of its surface combatants and special mission aircraft, but it continues to lack a robust deep-water ASW capability. By prioritizing the acquisition of ASW capable surface combatants, acoustic surveillance ships, and fixed and rotary wing ASW capable aircraft, the PLAN is significantly improving its ASW capabilities. However, it will still require several years of training and systems integration for the PLAN to develop a robust offensive deep water ASW capability.

(2022 DOD CMSD, p. 53.)

See also Gabriel Honrada, “China Simulates ‘Z-day’ Total Sea War with the US,” Asia Times, July 5, 2023; Stephen Chen, “Chinese Military Conjures World War Z Scenario of All-Out Conflict to Test and Evaluate New Navy Weapons,” South China Morning Post, June 28, 2023; Felix K. Chang, “Sustaining the Chinese Navy’s Operations at Sea: Bigger Fists, Growing Legs,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, May 3, 2023; Bryan Clark, “Submarines Will Not Solve America’s Eroding Undersea Advantage,” Washington Examiner, December 5, 2022; Ryan D. Martinson and Conor Kennedy, “Using the Enemy to Train the Troops—Beijing’s New Approach to Prepare its Navy for War,” China Brief, March 25, 2022; Samuel Cranny-Evans, “China’s Maritime Surveillance Network: Bold Moves for Ocean Dominance,” Jane’s International Defence Review, February 17, 2022.

(continued…)

p. 6

- In addition to modernizing its navy, China has substantially increased the size and capabilities of its coast guard. DOD states that China’s coast guard is “the largest maritime law enforcement fleet in the world.”24 China also operates a sizeable maritime militia that includes a large number of fishing vessels. China relies primarily on its maritime militia and coast guard to assert and defend its maritime claims in its near-seas region, with the navy operating over the horizon as a potential backup force.25

Numbers of Ships; Comparisons to U.S. Navy

Overview

DOD states that “the PLAN is the largest navy in the world with a battle force of approximately 340 platforms, including major surface combatants, submarines, ocean-going amphibious ships, mine warfare ships, aircraft carriers, and fleet auxiliaries…. This figure does not include approximately 85 patrol combatants and craft that carry anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM). The PLAN’s overall battle force is expected to grow to 400 ships by 2025 and 440 ships by 2030. Much of this growth will be in major surface combatants.”26 DIA states that “the PLAN is rapidly retiring older, single-mission warships in favor of larger, multimission ships equipped with advanced antiship, antiair, and antisubmarine weapons and sensors and C2 [command and control] facilities.”27

Ultimate Size and Composition of China’s Navy Not Publicly Known

The planned ultimate size and composition of China’s navy is not publicly known. The U.S. Navy makes public its force-level goal and regularly releases a 30-year shipbuilding plan that shows planned procurements of new ships, planned retirements of existing ships, and resulting projected force levels, as well as a five-year shipbuilding plan that shows, in greater detail, the first five years of the 30-year shipbuilding plan.28 In contrast, China does not release a navy force-level goal or detailed information about planned ship procurement rates, planned total ship procurement quantities, planned ship retirements, or resulting projected force levels. The ultimate size and composition of China’s navy might be an unsettled and evolving issue among Chinese

***

24 DOD states that

The CCG’s [China Coast Guard’s] rapid expansion and modernization has made it the largest maritime law enforcement fleet in the world. Its newer vessels are larger and more capable than older vessels, allowing them to operate further offshore and remain on station longer. A 2019 academic study published by the U.S. Naval War College estimates the CCG has over 140 regional and oceangoing patrol vessels (of more than 1,000 tons displacement). Some of the vessels are former PLAN vessels, such as corvettes, transferred to the CCG and modified for CCG operations. The newer, larger vessels are equipped with helicopter facilities, high-capacity water cannons, interceptor boats, and guns ranging from 20 to 76 millimeters. In addition, the same academic study indicates the CCG operates more than 120 regional patrol combatants (500 to 999 tons), which can be used for limited offshore operations, and an additional 450 coastal patrol craft (100 to 299 tons).

(2022 DOD CMSD, p. 78. See also 2019 DIA CMP, p. 78.)

25 For additional discussion, see 2022 DOD CMSD, pp. 79-80, and CRS Report R42784, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

26 2022 DOD CMSD, p. 52. See also 2019 DIA CMP, p. 63.

27 2019 DIA CMP, p. 69.

28 For more information on the U.S. Navy’s force-level goal, 30-year shipbuilding plan, and five-year shipbuilding plan, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

p. 7

military and political leaders. One observer states that “it seems the majority of past foreign projections of Chinese military and Chinese navy procurement scale and speed have been underestimates…. All military forces have a desired force requirement and a desired ‘critical mass’ to aspire toward. Whether the Chinese navy is close to its desired force or not, is of no small consequence.”29

Number of Ships Is a One-Dimensional Measure, but Trends in Numbers Can Be of Value Analytically

Relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities are sometimes assessed by showing comparative numbers of U.S. and Chinese ships. Although the total number of ships in a navy (or a navy’s aggregate tonnage) is relatively easy to calculate, it is a one-dimensional measure that leaves out numerous other factors that bear on a navy’s capabilities and how those capabilities compare to its assigned missions. As a result, as discussed in further detail in Appendix A, comparisons of the total numbers of ships in China’s navy and the U.S. Navy are highly problematic as a means of assessing relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities and how those capabilities compare to the missions assigned to the two navies. At the same time, however, an examination of trends over time in these relative numbers of ships can shed some light on how the relative balance of U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities might be changing over time.

Three Tables Showing Numbers of Chinese and U.S. Navy Ships

Table Showing Figures from Annual DOD Reports

Table 1 shows numbers of certain types of Chinese navy ships—those that might be thought of as the principal combat ships of China’s navy—from 2005 to the present, along with the number of China coast guard ships from 2017 to the present, as presented in DOD’s annual reports on military and security developments involving China. As can be seen in Table 1, every type of Chinese navy ship shown in the table has increased numerically since 2005.

As can be seen in Table 1, about 61% of the increase since 2005 in the total number of Chinese navy ships shown in the table (a net increase of 83 ships out of a total net increase of 135 ships) resulted from increases in missile-armed fast patrol craft starting in 2009 (a net increase of 33 ships) and corvettes starting in 2014 (50 ships). These are the smallest surface combatants shown in the table. The net 33-ship increase in missile-armed fast patrol craft was due to the construction between 2004 and 2009 of about 60 new Houbei (Type 022) fast attack craft30 and the retirement of about 27 older fast attack craft. The 50-ship increase in corvettes is due to the Jingdao (Type 056) corvette program discussed later in this report. ONI states that “a significant portion of China’s Battle Force consists of the large number of new corvettes and guided-missile frigates recently built for the PLAN.”31 As can also be seen in the table, most of the remaining increase since 2005 in the number of Chinese navy ships shown in the table is accounted for by increases in cruisers and destroyers (21 ships) and amphibious ships (14 ships).

***

29 Rick Joe, “Hints of Chinese Naval Procurement Plans in the 2020s,” Diplomat, December 25, 2020.

30 The Type 022 program was discussed in the August 1, 2018, version of this CRS report, and earlier versions.

31 Source: Unclassified ONI information paper prepared for Senate Armed Services Committee, subject “UPDATED China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030,” February 2020, p. 4. Provided by Senate Armed Services Committee to CRS and CBO on March 4, 2020, and used in this CRS report with the committee’s permission.

p. 8

Table 1 lumps together less capable older Chinese ships with more capable modern Chinese ships. In examining the numbers in the table, it can be helpful to keep in mind that for many of the types of Chinese ships shown in the table, the percentage of the ships accounted for by more capable modern designs was growing over time, even if the total number of ships for those types was changing little.

For reference, Table 1 also shows the total number of ships in the U.S. Navy (known technically as the total number of battle force ships), and compares it to the total number of the types of Chinese ships that are shown in the table.32 The result is an apples-vs.-oranges comparison, because the Chinese figures exclude certain ship types, such as auxiliary and support ships, while the U.S. Navy figure includes auxiliary and support ships but excludes patrol craft. Changes over time in this apples-vs.-oranges comparison, however, can be of value in understanding trends in the comparative sizes of the U.S. and Chinese navies.

On the basis of the figures in Table 1, it might be said that in 2015, the total number of principal combat ships in China’s navy surpassed the total number of U.S. Navy battle force ships (a figure that includes not only the U.S. Navy’s principal combat ships, but also other U.S. Navy ships, such as auxiliary and support ships). It is important, however, to keep in mind the differences in composition between the two navies. The U.S. Navy, for example, has many more aircraft carriers, nuclear-powered submarines, and cruisers and destroyers, while China’s navy has many more diesel attack submarines, frigates, and corvettes.

Table Showing ONI Figures from February 2020

Table 2 shows comparative numbers of Chinese and U.S. battle force ships (and figures for certain types of ships that contribute toward China’s total number of battle force ships) from 2000 to 2030, with the figures for 2025 and 2030 being projections. The figures for China’s ships are taken from an ONI information paper of February 2020. Battle force ships are the types of ships that count toward the quoted size of the U.S. Navy. For China, the total number of battle force ships shown excludes the missile-armed coastal patrol craft shown in Table 1, but includes auxiliary and support ships that are not shown in Table 1. Compared to Table 1, the figures in Table 2 come closer to providing an apples-to-apples comparison of the two navies’ numbers of ships, although it could be argued that China’s missile-armed coastal patrol craft can be a significant factor for operations within the first island chain.

As shown in Table 2, China’s navy surpassed the U.S. Navy in terms of total number of battle force ships sometime between 2015 and 2020. As mentioned earlier in connection with Table 1, however, it is important to keep in mind the differences in composition between the two navies. The U.S. Navy, for example, currently has many more aircraft carriers, nuclear-powered submarines, and cruisers and destroyers, while China’s navy currently has many more diesel attack submarines, frigates, and corvettes.

Table Showing U.S. Navy Figures from October 2020

Table 3 shows numbers of certain types of Chinese navy ships in 2020, and projections of those numbers for 2025, 2030, and 2040, along with the total number of U.S. Navy battle force ships in 2020, and projections of those numbers for 2025, 2030, and 2040. The figures for China’s ships were provided by the Navy at the request of CRS. As with Table 1, the result is an apples-vs.-

***

32 The DOD report generally covers events of the prior calendar year. Thus, the 2021 edition covers events during 2020, and so on for earlier years. Similarly, for the U.S. Navy figures, the 2021 column in Table 1 shows the figure for the end of FY2020, and so on for earlier years.

p. 9

oranges comparison between the Chinese navy and U.S. Navy totals, because the Chinese total excludes certain ship types, such as auxiliary and support ships, while the U.S. Navy total includes auxiliary and support ships.

Table 1. Numbers of Certain Types of Chinese and U.S. Ships Since 2005

Sources: Table prepared by CRS based on 2005-2022 editions of annual DOD report to Congress on military and security developments involving China (known for 2009 and prior editions as the report on China military power), and (for U.S. Navy ships) U.S. Navy data as presented in CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke. Consistent with the DOD report, which shows data for China for the year prior to the report’s publication date, the U.S. Navy data here shows data for the year prior to the prior to the DOD report’s publication date. For example, the figure of 294 shown for the U.S. Navy for 2022 shows the number of U.S. Navy ships at the end of FY2021.

Key to abbreviations: n/a = data not available in annual DOD report. SSB = ballistic missile submarines. SSN = nuclear-powered attack submarines. SS = diesel attack submarines. CV = aircraft carriers. CG = cruisers. DD = destroyers. FF = frigates. FFL = corvettes (i.e., light frigates). PC = missile-armed coastal patrol craft. LST = amphibious tank landing ship. LPD = amphibious transport dock ship. LSM = amphibious medium landing ship. (Starting with the 2021 edition, the annual DOD report shows a combined figure for LST/LPD and LSM.) Column for Total PLAN ship types shown to right, which shows what might be thought of as the principal combat ships of China’s navy, does not include other PLAN ship types not shown to right, such as auxiliary and support ships. CCG = China Coast Guard ships. U.S. total = Total U.S. Navy battle force ships, which includes

p. 10

(Starting with the 2021 edition, the annual DOD report shows a combined figure for LST/LPD and LSM.) Column for Total PLAN ship types shown to right, which shows what might be thought of as the principal combat ships of China’s navy, does not include other PLAN ship types not shown to right, such as auxiliary and support ships. CCG = China Coast Guard ships. U.S. total = Total U.S. Navy battle force ships, which includes auxiliary and support ships but excludes patrol craft. U.S. vs. PLAN ship types shown = total U.S. Navy battle force ships compared to the column for Total PLAN ship types shown to right.

Notes: The DOD report generally covers events of the prior calendar year. Thus, the 2021 edition covers events during 2020, and so on for earlier years. Similarly, for the U.S. Navy figures, the 2021 column shows the figure for the end of FY2020, and so on for earlier years.

As shown in Table 3, the U.S. Navy projects that between 2020 and 2040, the total number of Chinese ships of the types shown in the table will increase by 94, or about 39%, with most of that increase (77 ships out of 94) coming from roughly equal increases in numbers of large surface combatants (cruisers and destroyers—39 ships) and small surface combatants (frigates and corvettes—38 ships). Numbers of ballistic missile submarines and nuclear-powered attack submarines are each projected to more than double between 2020 and 2040, and the total number of diesel attack submarines is projected to remain almost unchanged. The number of large surface combatants is projected to almost double, and the number of small surface combatants is projected to increase by more than one-third. Numbers of larger (LHA- and LPD-type) amphibious ships are projected to increase, and the number of smaller (LST-type) amphibious ships is projected to decline, with the result that the total number of amphibious ships of all kinds is projected to decline slightly.

p. 11

Table 3. Numbers of Chinese and U.S. Navy Ships, 2020-2040

Figures for Chinese ships are from U.S. Navy, reflecting data as of October 2020

33 CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

p. 12

Figure 1. Numbers of Ships in U.S. Navy and China’s Navy, 2000-2030

Selected Elements of China’s Naval Modernization Effort

This section provides a brief overview of elements of China’s naval modernization effort that have attracted frequent attention from observers.

Anti-Ship Missiles

Anti-Ship Ballistic Missiles (ASBMs)

China is fielding two types of land-based ballistic missiles with a capability of hitting ships at sea at extended ranges—the DF-21D (Figure 2), a road-mobile anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) with a range of more than 1,500 kilometers (i.e., more than 910 nautical miles), and the DF-26 (Figure 3), a road-mobile, multi-role intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) with a maximum range of about 3,000 kilometers (i.e., about 1,620 nautical miles) that DOD says is “capable of conducting both conventional and nuclear precision strikes against ground targets as well as conventional strikes against naval targets.”34

***

34 2022 DOD CMSD, p. 64. A map on page 67 of the report shows the DF-26 with a range of 4,000 kilometers (about 2,160 nautical miles).

p. 13

Source: Cropped version of photograph accompanying Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s DF-21D Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile (ASBM)—Officially Revealed at 3 September Parade—Complete Open Source Research Compendium,” AndrewErickson.com, September 10, 2015, accessed August 28, 2019.

Until 2020, reported test flights of DF-21s and SDF-26s had not involved attempts to hit moving ships at sea. A November 14, 2020, press report stated that an August 2020 test firing of DF-21 and DF-26 ASBMs into the South China resulted in the missiles successfully hitting a moving target ship south of the Paracel Islands.35 A December 3, 2020, press report stated that Admiral Philip Davidson, the commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, “confirmed, for the first time

***

34 Kristin Huang, “China’s ‘Aircraft-Carrier Killer’ Missiles Successfully Hit Target Ship in South China Sea, PLA Insider Reveals,” South China Morning Post, November 14, 2020. See also Peter Suciu, “Report: China’s ‘Aircraft-Carrier Killer’ Missiles Hit Target Ship in August,” National Interest, November 15, 2020; Andrew Erickson, “China’s DF-21D and DF-26B ASBMs: Is the U.S. Military Ready?” Real Clear Defense, November 16, 2020.

p. 14

from the U.S. government side, that China’s People’s Liberation Army has successfully tested an anti-ship ballistic missile against a moving ship.”36

Observers have expressed strong concerns about China’s ASBMs, because such missiles, in combination with broad-area maritime surveillance and targeting systems, would permit China to attack aircraft carriers, other U.S. Navy ships, or ships of allied or partner navies operating in the Western Pacific. The U.S. Navy has not previously faced a threat from highly accurate ballistic missiles capable of hitting moving ships at sea. For this reason, some observers have referred to ASBMs as a “game-changing” weapon.

In April 2022, it was reported that China may have developed a new type of ASBM, perhaps designated the YJ-21, that is small enough to fit into the vertical launch tube of a surface combatant, and that China had test fired such a weapon from a Type 055 cruiser (or large destroyer).37

China reportedly is developing hypersonic glide vehicles that, if incorporated into Chinese ASBMs, could make Chinese ASBMs more difficult to intercept. A February 2, 2023, press report states

For the first time, the PLA has officially revealed the performance of its advanced anti-ship hypersonic missile, sending a warning to the US amid high tensions in the Taiwan Strait, Chinese analysts said.

China’s YJ-21, or Eagle Strike-21, has a terminal speed of Mach 10, cannot be intercepted by any anti-missile weapons system in the world and can launch lethal strikes towards enemy ships, according to an article posted by the official Weibo account of the People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force on Monday [January 30]….

The article declares that the missile travels six times the speed of sound all the way, and has a terminal speed of 10 times the speed of sound, meaning a speed of 3,400 metres per second (11,155 feet per second) when it hits the target.

“Such a terminal speed cannot be intercepted by any anti-missile weapon system at this stage. Even if it is dropped directly at this terrifying speed [hitting the target] without an explosion it will cause a fatal strike to the enemy ship,” the article stated.

The debut of its export variant, the YJ-21E, at last year’s Airshow China “shows that the domestic version of the Eagle Strike-21 ship-borne hypersonic missile is no longer the navy’s most advanced ship-borne hypersonic missile, and more advanced ship-borne hypersonic missiles are likely to have appeared,” it said.

The article was first published on the website of China Science Communication, Guangming Online last year, but it was reposted by an official PLA account for the first time, a development experts described as a clear message for the US.38

***

36 Josh Rogin, “China’s Military Expansion Will Test the Biden Administration,” Washington Post, December 3, 2020.

37 Rick Fisher, “China Deploys New Missiles Against the US Navy,” Epoch Times, April 29, 2022; Minnie Chan, “Chinese Navy Shows Off Hypersonic Anti-Ship Missiles In Public,” South China Morning Post, April 20, 2022; Tyler Rogoway, “Mysterious New Missile Launched By China’s Giant Type 055 Destroyer,” The Drive, April 20. See also Decker Eveleth, People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force Order of Battle 2023, James Martin Center of Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, 2023, 65 pp.

38 Amber Wang, “Chinese Military Announces YJ-21 Missile Abilities in Social Media Post Read as Warning to US Amid Tension in Taiwan Strait,” South China Morning Post, February 2, 2023. Material in brackets as in original. See also Gabriel Honrada, “China’s Hypersonic Triad Pressing Down on US,” Asia Times, April 4, 2023.

p. 15

Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs)

Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs)

China’s extensive inventory of anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) (see Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6 for examples of reported images) includes both Russian- and Chinese-made designs, including some advanced and highly capable ones, such as the Chinese-made YJ-18.39

Although China’s ASCMs do not always receive as much press attention as China’s ASBMs (perhaps because ASBMs are a more recent development), observers are nevertheless concerned about them. As discussed later in this report, the relatively long ranges of certain Chinese ASCMs have led to concerns among some observers that the U.S. Navy is not moving quickly enough to arm U.S. Navy surface ships with similarly ranged ASCMs. … … …

***

39 2022 DOD CMSD, p. 54. See also Dmitry Filipoff, “Fighting DMO, PT. 8: China’s Anti-Ship Firepower And Mass Firing Schemes,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), May 1, 2023 (the acronym DMO refers to distributed maritime operations); Sam Goldsmith, Vampire Vampire Vampire, The PLA’s Anti-Ship Cruise Missile Threat to Australian and Allied Naval Operations, Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), April 2022, 43 pp.; Michael Peck, “Chinese Scientists Say They’re Working on an Anti-Ship Missile that Can Fly as High as an Airliner and Dive as Deep as a Submarine,” Business Insider, October 20, 2022; “China Is Developing a New Supersonic Anti-Ship Missile,” Naval News, September 19, 2022.

p. 17

Figure 6. Reported Image of Anti-Ship Cruise Missile (ASCM)

Source: Dennis M. Gormley, Andrew S. Erickson, and Jingdong Yuan, A Low-Visibility Force Multiplier, Assessing China’s Cruise Missile Ambitions, Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Washington, DC, 2014. The image appears on an unnumbered page following page 14. The caption to the photograph states, “YJ-83A/C-802A ASCM on display at 2008 Zhuhai Airshow.” The photograph is credited to Associated Press/Wide World Photos. … …

p. 18

Submarines

Overview

China has been steadily modernizing its submarine force, and most of its submarines are now built to relatively modern Chinese and Russian designs.42 Qualitatively, China’s newest submarines might not be as capable as Russia’s newest submarines,43 but compared to China’s earlier submarines, which were built to antiquated designs, its newer submarines are much more capable.44 An August 2023 Naval War College Report on China’s submarines states

After nearly 50 years since the first Type 091 SSN was commissioned, China is finally on the verge of producing world-class nuclear-powered submarines. This report argues that the propulsion, quieting, sensors, and weapons capabilities of the Type 095 SSGN could approach Russia’s Improved Akula I class SSN. The Type 095 will likely be equipped with a pump jet propulsor, a freefloating horizontal raft, a hybrid propulsion system, and 12-18 vertical launch system tubes able to accommodate anti-ship and land-attack cruise missiles. China’s newest SSBN, the Type 096, will likewise see significant improvements over its predecessor, with the potential to compare favorably to Russia’s Dolgorukiy class SSBN in the areas of propulsion, sensors, and weapons, but more like the Improved Akula I in terms of quieting. If this analysis is correct, the introduction of the Type 095 and Type 096 would have profound implications for U.S. undersea security.45

A September 2023 Naval War College report on China’s submarine industrial base states

In recent years, China’s naval industries have made tremendous progress supporting the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) submarine force, both through robust commitment to research and development (R&D) and the upgrading of production infrastructure at the country’s three submarine shipyards…. Nevertheless, China’s submarine industrial base continues to suffer from surprising weaknesses in propulsion (from marine diesels to fuel cells) and submarine quieting. Closer ties with Russia could provide opportunities for China to overcome these enduring technological limitations by exploiting political and economic levers to gain access to Russia’s remaining undersea technology secrets.46

***

42 For a discussion of Russian military transfers to China, including transfers of submarine technology, see Paul Schwartz, The Changing Nature and Implications of Russian Military Transfers to China, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), June 2021, 8 pp. See also Joseph Trevithick, “Top Russian Submarine Design Bureau Hit By Cyber Attack With Chinese Characteristics,” The Drive, May 10, 2021.

43 Observers have sometimes characterized Russia’s submarines as being the most capable faced by the U.S. Navy. See, for example, Joe Gould and Aaron Mehta, “US Could Lose a Key Weapon for Tracking Chinese and Russian Subs,” Defense News, May 1, 2019; Dave Majumdar, “Why the U.S. Navy Fears Russia’s Submarines,” National Interest, October 12, 2018; John Schaus, Lauren Dickey, and Andrew Metrick, “Asia’s Looming Subsurface Challenge,” War on the Rocks, August 11, 2016; Paul McLeary, “Chinese, Russian Subs Increasingly Worrying the Pentagon,” Foreign Policy, February 24, 2016; Dave Majumdar, “U.S. Navy Impressed with New Russian Attack Boat,” USNI News, October 28, 2014.

44 For an additional overview of China’s submarine force, see U.S. Naval War College, China Maritime Studies Institute, Quick Look Report “Chinese Undersea Warfare: Development, Capabilities, Trends,” undated, 2 pp., which summarizes an academic conference on China’s udersea warfare capabilities that was held by the China Maritime Studies Institute on April 11-13, 2023.

45 Christopher P. Carlson and Howard Wang, A Brief Technical History of PLAN Nuclear Submarines Nuclear Submarines, China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI), U.S. Naval War College, August 2023, p. 1.

46 Sarah Kirchberger, China’s Submarine Industrial Base: State-Led Innovation with Chinese Characteristics State-Led Innovation with Chinese Characteristics, China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI), U.S. Naval War College, September 2023, p. 1

p. 58

Appendix A. Comparing U.S. and Chinese Numbers of Ships and Naval Capabilities

This appendix presents some additional discussion of factors involved in comparing U.S. and Chinese numbers of ships and naval capabilities.

U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities are sometimes compared by showing comparative numbers of U.S. and Chinese ships. Although the total number of ships in a navy (or a navy’s aggregate tonnage) is relatively easy to calculate, it is a one-dimensional measure that leaves out numerous other factors that bear on a navy’s capabilities and how those capabilities compare to its assigned missions. One-dimensional comparisons of the total numbers of ships in China’s navy and the U.S. Navy are highly problematic as a means of assessing relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities and how those capabilities compare to the missions assigned to those navies, for the following reasons:

- • A fleet’s total number of ships (or its aggregate tonnage) is only a partial metric of its capability. Many factors other than ship numbers (or aggregate tonnage) contribute to naval capability, including types of ships, types and numbers of aircraft, the sophistication of sensors, weapons, C4ISR systems, and networking capabilities, supporting maintenance and logistics capabilities, doctrine and tactics, the quality, education, and training of personnel, and the realism and complexity of exercises.162 In light of this, navies with similar numbers of ships or similar aggregate tonnages can have significantly different capabilities, and navy-to-navy comparisons of numbers of ships or aggregate tonnages can provide a highly inaccurate sense of their relative capabilities. The warfighting capabilities of navies have derived increasingly from the sophistication of their internal electronics and software. This factor can vary greatly from one navy to the next, and often cannot be easily assessed by outside observation. As the importance of internal electronics and software has grown, the idea of comparing the warfighting capabilities of navies principally on the basis of easily observed factors such as ship numbers and tonnages has become increasingly less reliable, and today is highly problematic.

- • Total numbers of ships of a given type (such as submarines or surface combatants) can obscure potentially significant differences in the capabilities of those ships, both between navies and within one country’s navy. Differences in capabilities of ships of a given type can arise from a number of other factors, including sensors, weapons, C4ISR systems, networking capabilities, stealth features, damage-control features, cruising range, maximum speed, and reliability and maintainability (which can affect the amount of time the ship is available for operation).

- • A focus on total ship numbers reinforces the notion that changes in total numbers necessarily translate into corresponding or proportional changes in aggregate capability. For a Navy like China’s, which is modernizing by replacing older, obsolescent ships with more modern and more capable ships, this is not necessarily the case. For example, while China’s attack submarine force has only a modestly larger number of boats now than it had in 2000 or 2005 (see

***

162 For further discussion, see, for example, Robert McKeown, “Assessing Military Capability: More than Just Counting Guns,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, December 2022.

p. 59

Congressional Research Service 59

- Table 1 and Table 2), it has considerably more aggregate capability than it did in 2000 or 2005, because the force today includes a much larger percentage of relatively modern designs.

- • Comparisons of total numbers of ships (or aggregate tonnages) do not take into account the differing global responsibilities and homeporting locations of each fleet. The U.S. Navy has substantial worldwide responsibilities, and a substantial fraction of the U.S. fleet is homeported in the Atlantic. As a consequence, only a certain portion of the U.S. Navy might be available for a crisis or conflict scenario in China’s near-seas region, or could reach that area within a certain amount of time. In contrast, China’s navy has more-limited responsibilities outside China’s near-seas region, and its ships are all homeported along China’s coast at locations that face directly onto China’s near-seas region. In a U.S.-China conflict inside the first island chain, U.S. naval and other forces would be operating at the end of generally long supply lines, while Chinese naval and other forces would be operating at the end of generally short supply lines.

- • Comparisons of numbers of ships (or aggregate tonnages) do not take into account maritime-relevant military capabilities that countries might have outside their navies, such as land-based anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), land-based anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), and land-based Air Force aircraft armed with ASCMs or other weapons. Given the significant maritime-relevant non-navy forces present in both the U.S. and Chinese militaries, this is a particularly important consideration in comparing U.S. and Chinese military capabilities for influencing events in the Western Pacific. Although a U.S.-China incident at sea might involve only navy units on both sides, a broader U.S.-China military conflict would more likely be a force-on-force engagement involving multiple branches of each country’s military.

- • The missions to be performed by one country’s navy can differ greatly from the missions to be performed by another country’s navy. Consequently, navies are better measured against their respective missions than against one another. Although Navy A might have less capability than Navy B, Navy A might nevertheless be better able to perform Navy A’s intended missions than Navy B is to perform Navy B’s intended missions. This is another significant consideration in assessing U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities, because the missions of the two navies are quite different.

As mentioned earlier, while comparisons of the total numbers of ships in China’s Navy and the U.S. Navy are highly problematic as a means of assessing relative U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities and how those capabilities compare to the missions assigned to those navies, an examination of the trends over time in the relative numbers of ships can shed some light on how the relative balance of U.S. and Chinese naval capabilities might be changing over time. … … …

Summary

China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, is the top focus of U.S. defense planning and budgeting. China’s naval modernization effort has been underway for about 30 years, since the early to mid-1990s, and has transformed China’s navy into a much more modern and capable force. China’s navy is a formidable military force within China’s near-seas region, and it is conducting a growing number of operations in the broader waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and waters around Europe.

China’s navy is, by far, the largest of any country in East Asia, and sometime between 2015 and 2020 it surpassed the U.S. Navy in numbers of battle force ships (meaning the types of ships that count toward the quoted size of the U.S. Navy). DOD states that China’s navy “is the largest navy in the world with a battle force of approximately 340 platforms, including major surface combatants, submarines, ocean-going amphibious ships, mine warfare ships, aircraft carriers, and fleet auxiliaries…. This figure does not include approximately 85 patrol combatants and craft that carry anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM). The … overall battle force [of China’s navy] is expected to grow to 400 ships by 2025 and 440 ships by 2030.” The U.S. Navy, by comparison, included 290 battle force ships as of October 5, 2023, and the Navy’s FY2024 budget submission projects that the Navy will include 290 battle force ships by the end of FY2030. U.S. military officials and other observers are expressing concern or alarm regarding the pace of China’s naval shipbuilding effort and resulting trend lines regarding the relative sizes and capabilities of China’s navy and the U.S. Navy.

China’s naval modernization effort encompasses a wide array of ship, aircraft, weapon, and C4ISR (command and control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) acquisition programs, as well as improvements in logistics, doctrine, personnel quality, education and training, and exercises. China’s navy currently has certain limitations and weaknesses, which it is working to overcome.

China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, is assessed as being aimed at developing capabilities for, among other things, addressing the situation with Taiwan militarily, if need be; achieving a greater degree of control or domination over China’s near-seas region, particularly the South China Sea; defending China’s commercial sea lines of communication (SLOCs), particularly those linking China to the Persian Gulf; displacing U.S. influence in the Western Pacific; and asserting China’s status as the leading regional power and a major world power. Observers believe China wants its navy to be capable of acting as part of an anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) force—a force that can deter U.S. intervention in a conflict in China’s near-seas region over Taiwan or some other issue, or failing that, delay the arrival or reduce the effectiveness of intervening U.S. forces.

The U.S. Navy has taken a number of actions to counter China’s naval modernization effort. Among other things, the U.S. Navy has shifted a greater percentage of its fleet to the Pacific; assigned its most-capable new ships and aircraft to the Pacific; maintained or increased general presence operations, training and developmental exercises, and engagement and cooperation with allied and other navies in the Indo-Pacific; increased the planned future size of the Navy; initiated, increased, or accelerated numerous programs for developing new military technologies and acquiring new ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles, and weapons; developed new operational concepts for countering Chinese maritime A2/AD forces; and signaled that the Navy in coming years will shift to a more-distributed fleet architecture that will feature a substantially greater use of unmanned vehicles. The issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Biden Administration’s proposed U.S. Navy plans, budgets, and programs for responding to China’s naval modernization effort.