Geography Matters, Time Collides: Mapping China’s Maritime Strategic Space under Xi

Honored to contribute to Nadège Rolland’s insightful National Bureau of Asian Research Strategic Space series!

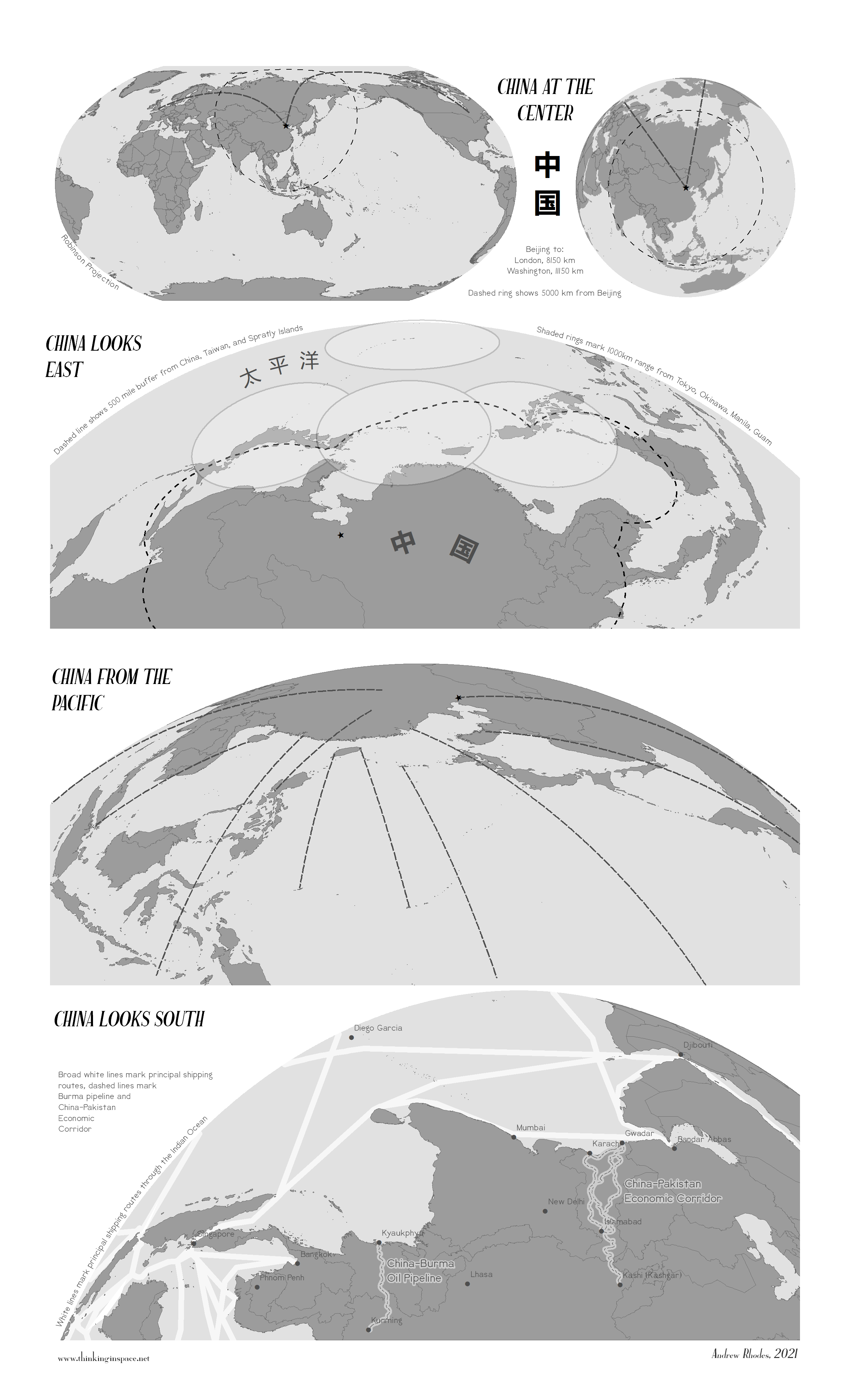

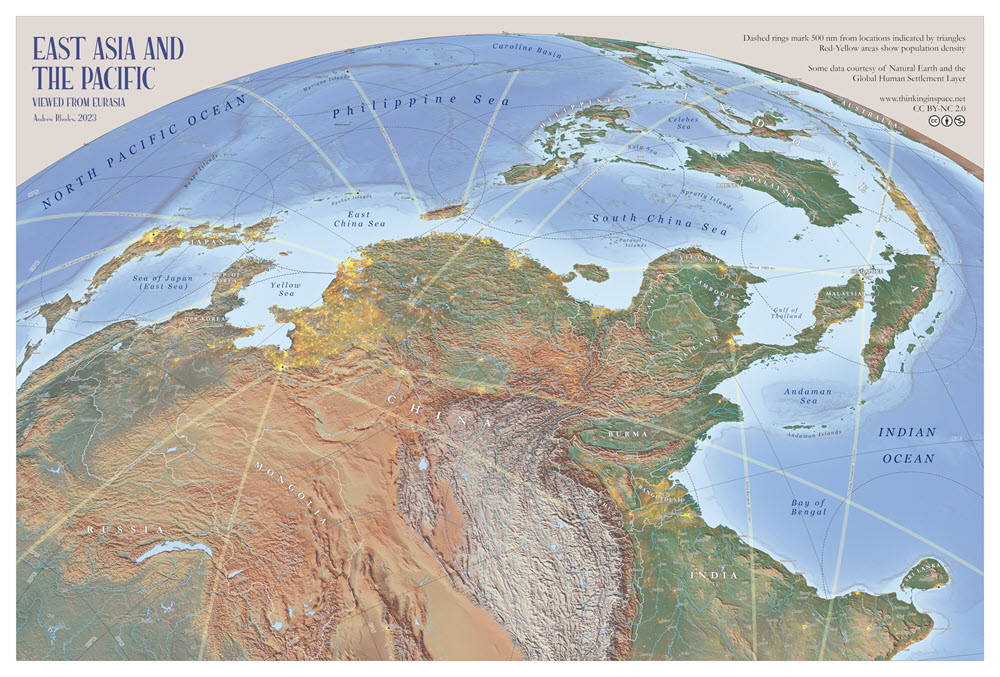

Grateful to Andrew Rhodes for permission to use three of his world-class maps! Click here to see his other cartographic creations, as well as his publications. I’ve made a curated compilation of some of his greatest hits here.

What are China’s military maritime priorities? Easy to say historically and nearby, harder looking forward in time and distance…

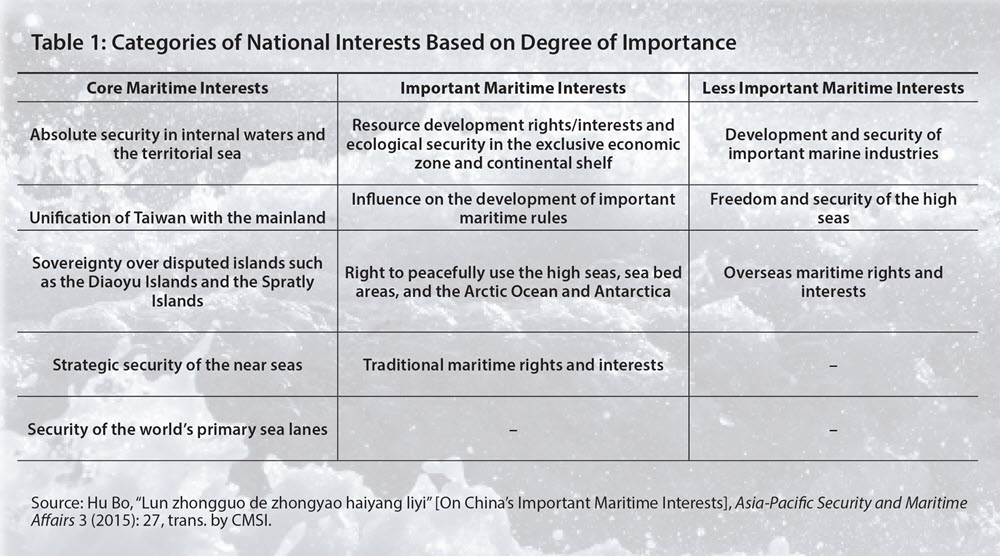

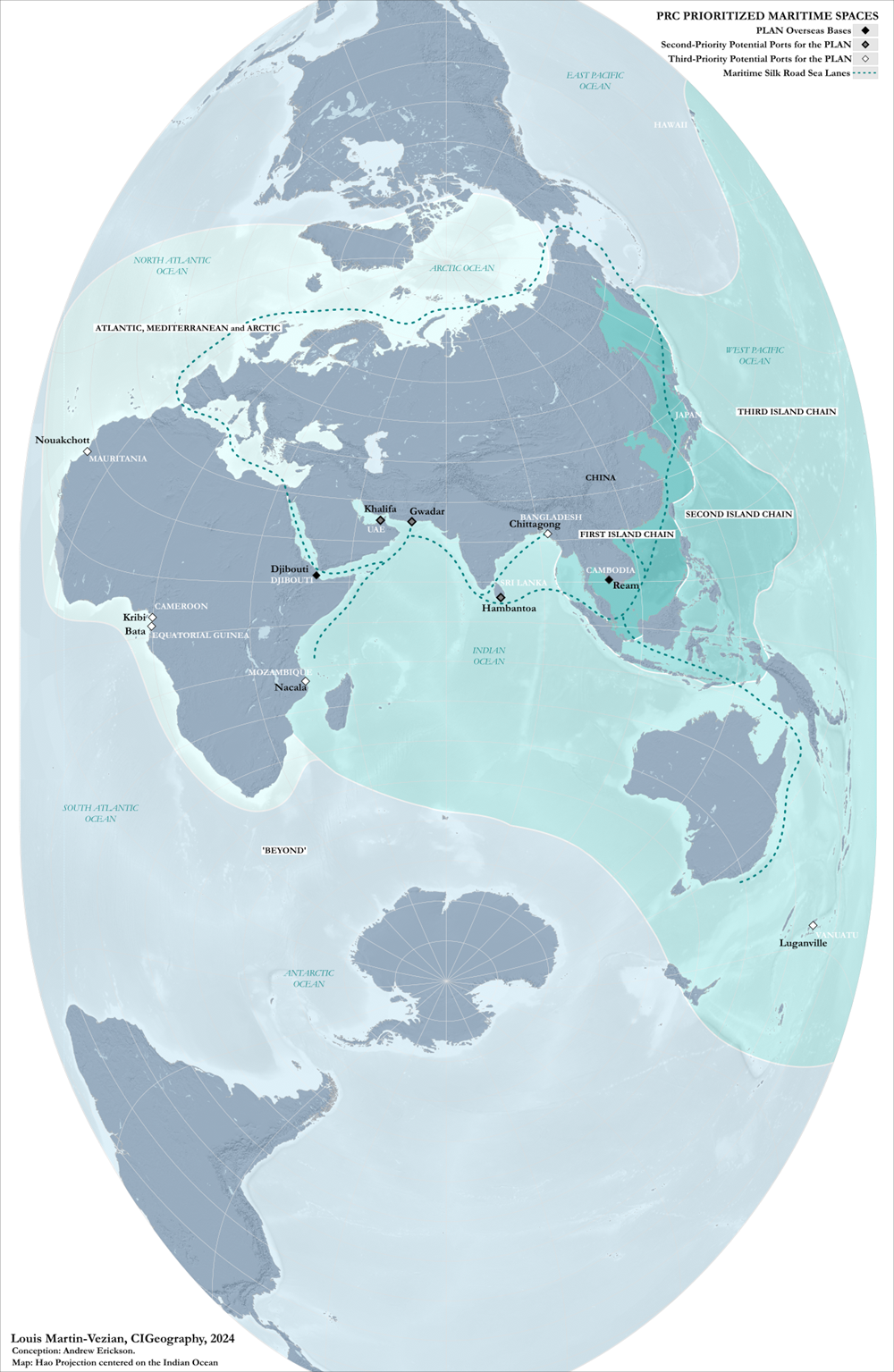

Overall, available PRC writings suggest tentative prioritization: (1) Near Seas and First Island Chain, (2) out to Second Island Chain, (3) Western Pacific out to Third Island Chain bisecting Hawaii and northern Indian Ocean, (4) Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea and Arctic Ocean, and (5) beyond. Few sources explicitly delineate such layers—but few, if any, disagree. I include a (translated) table by Peking University Professor Hu Bo, which offers ideas in this regard.

Delighted to work with Louis Martin-Vézian of CIGeography on a new “PRC Prioritized Maritime Spaces Map”!

- Projects China’s oceanic priorities strategic zones.

- Offers best official depiction available of key Maritime Silk Road sea lanes in Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative.

- Plots PLA Navy’s current bases as well as potential future first- and second-priority ports that might offer special access/support.

Andrew S. Erickson, Geography Matters, Time Collides: Mapping China’s Maritime Strategic Space under Xi (Seattle, WA: National Bureau of Asian Research, 1 August 2024).

Andrew Erickson considers the “mental map” of China’s leaders—how they regard the physical nature of strategic space—in the context of the maritime expansion being pursued by Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party. He uses maps as visual references for understanding China’s evolving maritime geography and the constraints on its power in the maritime domain.

This essay is from the Mapping China’s Strategic Space project, which seeks to better understand what constitutes the “strategic space” beyond China’s national borders that Chinese leaders consider vital to their pursuit of national political, economic, and security objectives and to the achievement of China’s rise.

With an increasingly powerful People’s Republic of China (PRC) under paramount leader Xi Jinping engaging in meteoric military-maritime buildup and pressing disputed sovereignty claims with increasing assertiveness, it is more important than ever to consider Beijing’s “mental map”: how its leaders regard the physical nature of strategic space. As Andrew Rhodes argues cogently, “Being able to ‘think in space’ is a crucial tool for decision-makers, but one that is often deemphasized.”1 This applies to understanding both how PRC leaders envision China’s strategic space and how it is evolving in practice.

Beijing pursues a disciplined hierarchy of national security priorities in a pattern that Peter Dutton terms “concentrism”: “The strongest power is reserved for managing and securing its periphery, the next ring is a zone of disruption of potential attacking powers, and the third is to venture beyond the first two largely at the sufferance of stronger regional powers.” He refers to these three spheres, respectively, as “zones of control, influence, and reach.”2 The resulting “ripples of capability” in China’s military forces, extending in progressively descending circles of intensity outward from PRC shores, remain best viewed overall “through the lens of distance.”3

Per the mental map of Xi and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) the PRC has achieved relatively smooth expansion of influence overland through Central Asia to Europe and the Middle East. It is still working on a more contested project of maritime expansion but has made considerable progress there as well. Beijing’s ambitions also extend to frontier domains. Regarding the projection of sea power, China faces difficult opponents and geography. It is nevertheless becoming an increasingly formidable opponent to neighbors over sovereignty disputes, none more so than Taiwan. The map below by Rhodes offers perspectives on Beijing’s geostrategic location. … … …