Dr. Peter Dutton, J.D. now Senior Research Scholar in Law & Senior Fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center

Big news! Dr. Peter Alan Dutton, J.D., has just joined Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center as a Senior Research Scholar in Law and a Senior Fellow. This follows twenty-three years of superlative leadership, scholarship, teaching, and other academic and policy contributions at the U.S. Naval War College. His new bio is appended immediately below. The compilation following below it documents Prof. Dutton’s body of work and experience that he brings to this new position, and makes it readily accessible to all who may find it of interest. In New Haven, Dr. Dutton continues an amazing career, which I’ve previously summarized (in reverse chronological order) as “Dean, Director, Scholar, Lawyer, Naval Flight Officer.” Looking forward to his next great chapter as he returns to focusing on his love of legal studies, and to the insights that flow from it!

Peter Dutton is a Senior Research Scholar in Law and Senior Fellow in the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School. Before joining the Center, he was professor of international law in the Stockton Center for International Law at the U.S. Naval War College. He also served as dean (interim) of the Center for Naval Warfare Studies, as director of the China Maritime Studies Institute, and as professor of joint military operations.

Dutton served the U.S. Navy for more than 40 years in active duty and civilian capacities. His active-duty career began as a naval flight officer in a variety of aircraft, including the A-6E Intruder, with operations in the Caribbean, Pacific, and European theaters. As a Judge Advocate, his active-duty deployments include with Carrier Group Six, on board the USS John F. Kennedy, deployed to the Persian Gulf in support of Operation Southern Watch and other operations. He worked with and advised a series of Pacific Fleet Commanders, Secretaries of Defense, Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and other government offices on policies in the Asia-Pacific region. He also testified before the Senate and the House of Representatives on a variety of China-related issues.

Dutton’s research is interdisciplinary, combining international law, China studies, and international politics, including geostrategic theory. His writings focus on international law of the sea and air, with an emphasis on the East and South China Seas, and geo-political strategy. Additional research interests include Chinese views of sovereignty and international law, international law and Taiwan, and the strategic implications of China’s maritime expansion. He is a non-resident affiliate in research at Harvard University Fairbank Center for China Studies, and a non-resident affiliated scholar at the US-Asia Law Institute at New York University School of Law. Dutton holds a Ph.D. in War Studies from King’s College London, a J.D. from the College of William & Mary, an M.A. from the U.S. Naval War College, and a B.S. from Boston University.

FOUNDATIONAL SERVICE, WORKS, AND CONTRIBUTIONS

For the past twenty-three years, Dr. Dutton made superlative leadership, scholarship, teaching, and other academic and policy contributions at the Naval War College. The NWC professor (2004–24) and former China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) director (2011–19) and Interim Dean of the Center for Naval Warfare Studies (May 2021–October 2022) played a leading role in analyzing and interpreting China’s disputed island and maritime sovereignty claims, efforts to promote them, and broader geostrategic goals and trajectory. He did so for the scholarly and policy communities, the U.S. Navy, and other organizations of the U.S. government. Dr. Dutton drew on an unusual—if not unique—combination of training as a scholar, lawyer, naval flight officer, and journalist. He served at NWC as Judge Advocate General, Director of CMSI, and Interim Dean of CNWS, the College’s research arm; as well as tenured Full Professor in CNWS’s Strategic and Operational Research Department(SORD) and Stockton Center for International Law (SCIL).

As Interim Dean, CNWS, Professor Dutton shepherded the organization through a period of great challenges and change inside the College and at the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) leadership level alike. He helped reintegrate the Center’s diverse faculty to normal at-work operations after more than a year of college-wide remote work during the COVID pandemic. Dr. Dutton simultaneously helped CNWS achieve a much closer, more integrated research relationship with the Director(ate) of Warfighter Development (OPNAV N7) and across the Navy in response to requirements from the Fleet. In the ramp-up to his deanship, Prof. Dutton headed a fourteen-month hiring evolution across the Center in which he chaired eight hiring committees that supported the hiring of ten new CNWS faculty members.

Prior to serving at the senior leadership level, Dr. Dutton spent eight-and-a-half years as CMSI Director during a time of rapid strategic and operational change in Sino-American relations and corresponding increase in demand for high-quality, ground-breaking research products. From early 2011 through 2019, as head of CMSI, Director Dutton fostered broad understanding of Beijing’s strategy, policy, and activities at sea. Under his organizational and intellectual leadership, CMSI scholars performed impactful academic research using Chinese-language sources to develop deeper insight into key aspects of China’s growing maritime power. These efforts helped to inform the Navy, advise current leaders, educate the service’s next generation, and engage the Nation more broadly. Professor Dutton led the growth of CMSI faculty from four to eight full-time research and support personnel, expanded and included affiliates from around the College to more than a dozen, served as an integrator for China-related research across the College, and expanded CMSI’s engagement with faculty members from NWC’s teaching departments, the College of Maritime Operational Warfare (CMOW), and International Programs. Externally, he developed close relationships with each successive Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet and other operational leaders and their staffs to ensure CMSI research was closely connected to the fleet’s most pressing research requirements.

Dr. Dutton has contributed world-class academic scholarship at the intersection of international law, China studies, and maritime strategy. Its rigor and relevance has generated numerous invitations testify before the U.S. Senate, the House of Representatives, and U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. His writings have been included, inter alia, in policy briefings to the President of the United States, Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, several of whom he was subsequently requested to brief in person. His publications and presentations on PRC views of international law have been fundamental to the work of the National Security Council, the National Intelligence Council, and the highest-level operational commands. Additionally, Dr. Dutton’s research has been widely utilized by allied governments and he has been called upon to brief Cabinet level officials including in the United Kingdom, the Philippines, and Japan. His articles have published in a wide range of scholarly journals, including in the premier international law publication, the American Journal of International Law.

Dr. Dutton has thereby advanced the understanding of China’s maritime expansion in the broader naval, policy, and academic communities through regular conferences, the publication of conference volumes, CMSI’s China Maritime Studies series, and numerous other published articles, books, and reports. Furthermore, during his time as a member and leader of CMSI, Dr. Dutton completed a Ph.D. at King’s College London. His dissertation, entitled “Securing the Sea: China’s Quest for Maritime Security,” considered the geostrategic and security rationales for China’s sovereigntist approach to international law of the sea. His dissertation was awarded the “Outstanding Dissertation” award for his year of graduation. The presentations, lectures, and articles that resulted from his doctoral-level scholarship contributed substantially to NWC’s curriculum.

Among Prof. Dutton’s many observations: Rather than operate freely on exterior lines like such geographically advantaged sea powers as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan, China must radiate sea power from interior lines in a way that currently prioritizes the assertion of increasing control over its disputed sovereignty claims in the Yellow, East, and South China Seas; while also seeking growing influence across the Indo-Pacific, as well as nascent access and presence globally. Watch for Harvard to publish a book on this and related findings based on his King’s College London Ph.D. dissertation! (I have personally witnessed a U.S. cabinet official reveal that he had read several chapters as Dutton briefed him.)

Dr. Dutton began his career at NWC just weeks after the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks as the Staff Judge Advocate for the College. Because he had just come from deployment to the Persian Gulf as a Strike Group Judge Advocate, he was immediately called upon to contribute to the operational law teaching program in NWC’s Joint Military Operations (JMO) department as an additional duty. Dr. Dutton was then offered a full-time position as an active-duty JMO moderator and eventually a full-time civilian faculty position in the department. In addition to creating the first-ever differentiated law curriculum for the College of Naval Warfare, Professor Dutton made additional original contributions to the curriculum relating the concept of legitimacy to the achievement of operational and strategic objectives. These concepts made a lasting impact on the curriculum and are still taught by members of the JMO faculty today. Prof. Dutton has also been an active and popular contributor to the Electives program, sole-taught courses on “Governing China” and “China’s Century of Humiliation,” and contributing to a wide range of other electives, including Joint Land Air Sea Strategic Exercise (JLASS), international and maritime law electives, and the Maritime Advanced Warfare Seminar (MAWS), among others.

Professor Dutton is a highly-regarded scholar in his field. His in-residence affiliations include spending a year as a visiting scholar in MIT’s Security Studies Program. In 2012, he was invited to serve as an adjunct professor of law at the New York University School of Law, where he taught a course on “Chinese Attitudes Toward International Law.” At NYU Law School, he also served as a senior fellow and faculty advisor to the U.S.-Asia Law Institute where he managed a major research program on international law of the sea that included more than a decade of engagements with PRC scholars and officials and a project on the international law of maritime delimitation to assist East and Southeast Asian states manage their maritime disputes with China. In 2018 and 2023, Dr. Dutton was an adjunct faculty member at the University of Adelaide School of Law in Adelaide, South Australia. Since 2023, Dr. Dutton has been an Affiliated Scholar with the Norwegian Institute of Defence Studies in Oslo, Norway. He maintains additional active relationships with the Harvard University Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations, and the American Society of International Law.

Through all these efforts, Dr. Dutton has helped to both further China maritime security studies generally and pioneer an important academic field truly understood by only a select few, some of whom lack his freedom to interface with such a broad range of interlocutors and audiences on both sides of the Pacific. Although too modest to say so himself, Professor Dutton can already claim significant formal and informal policy influence. In the formal dimension, his periodic testimony before U.S. government bodies bears (re)reading as an encapsulation of his ongoing findings.

I have periodically reviewed the below testimonies and publications, and discovered fresh insights in the process. I thus commend this work by Professor Dutton to anyone interested in this subject. The summaries below are instructive, but it’s worth clicking on the links for the full text:

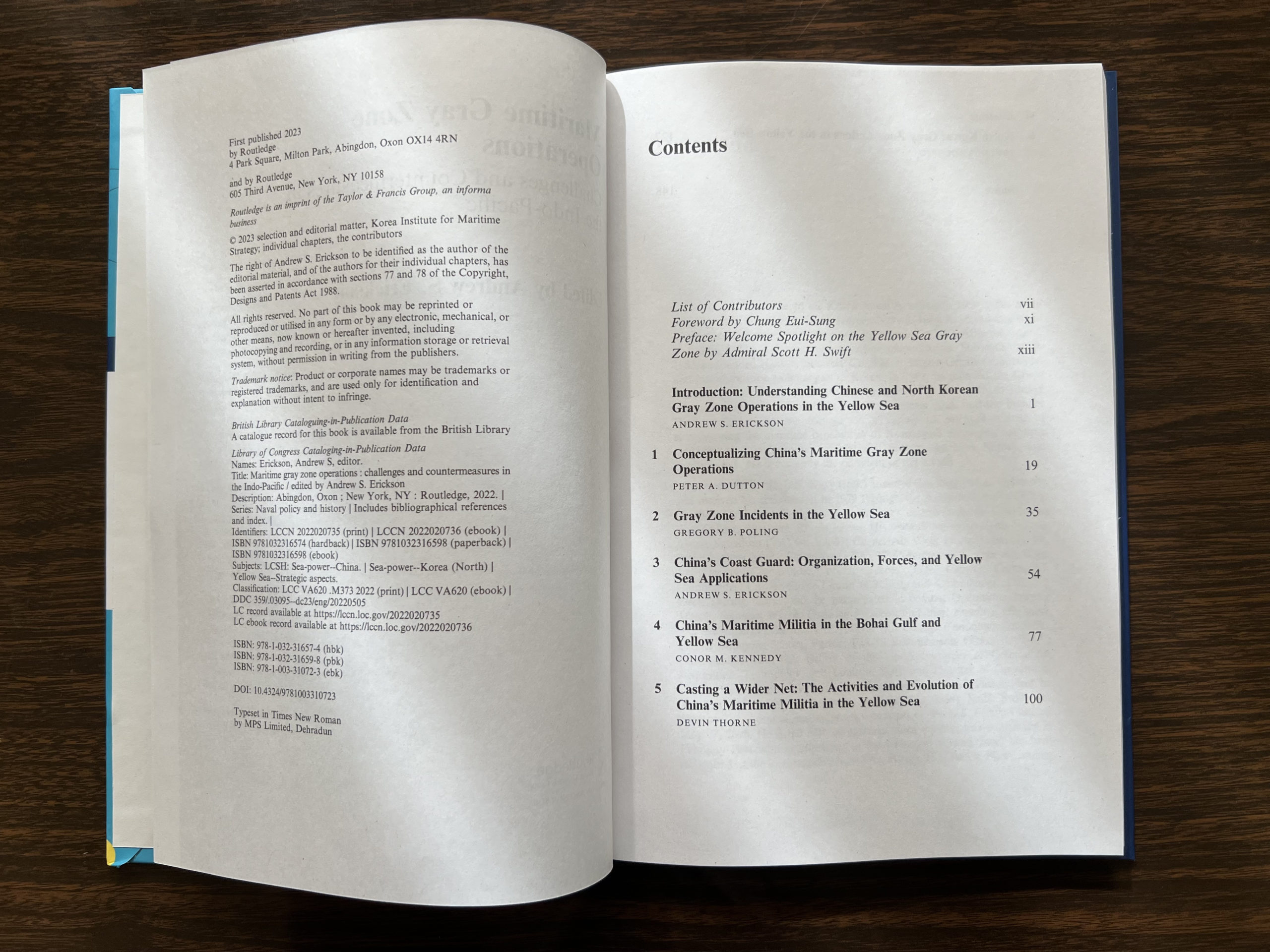

Peter A. Dutton, “Conceptualizing China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” in Andrew S. Erickson, ed., Maritime Gray Zone Operations: Challenges and Countermeasures in the Indo-Pacific (New York, NY: Routledge Cass Series: Naval Policy & History, 2022/paperback 2024), 19–34.

Something different is going on in the waters of the South China Sea. It is an international contestation, but not international armed conflict. It involves physical coercion, but not military force. It is neither truly a constabulary action, nor a campaign of war. This contestation exists in the space between conflict and peace. It involves unoccupied and unoccupiable space. This new form of contestation was in part enabled by the creation of vast resource zones at sea during the 20th century. In these continental shelves and exclusive economic zones, states accrued new forms of political space at sea. They acquired exclusive sovereign rights to the living and non-living resources and the jurisdictional authority to bring to bear the state’s constabulary powers to enforce those rights, while at the same time international law preserved many traditional freedoms enjoyed by all states.1 In a sense, these zones are themselves gray.

It happens all the time that states contest jurisdiction in these areas, as states dispute where boundaries should be drawn between their respective resource zones.2 Such boundary disputes are about the proper application of the rules to a given geographic area, not fundamental disagreements about what rules should apply and who should make them. They might involve incremental expansion of a state’s authority, but not the wholesale redefinition of sovereign rights to most of one of the world’s great seas as belonging to a single coastal country.3 This new phenomenon, this gray zone strategy, involves China’s use of non-militarized coercion to redefine the legal status of the 1.39 million square miles of ocean space it claims and to consolidate its authority over it.

To focus only on the specific actions employed by China in the South China Sea—indeed in all the seas around China—might lead to the conclusion that what is being observed is simply a new application of an existing concept—either hybrid warfare or gunboat diplomacy. But this new form of maritime contestation is not simply about the choice of tactics, nor about the simultaneous employment of constabulary and irregular forces in combination with other instruments of national power. It is also about the redefinition of the nature of a globally important maritime space and the wholesale rejection of the international rules that govern which state has priority of rights within it. It is about an expansionary campaign disguised as a defensive action. … … …

***

Peter A. Dutton, “Palestine’s Quest for Full United Nations Membership,” Articles of War(Lieber Institute: West Point, NY, 22 April 2024).

Amidst the ongoing war between Hamas and Israel in Gaza, the United States vetoed Palestine’s latest bid for full acceptance as a member State of the United Nations (UN). In the view of the United States, the only way for a stable future between Israel and Palestine is through direct, bilateral negotiations.

Earlier in the week the United Nations Security Council had unanimously agreed to begin the process to consider Palestine’s petition to become a full member State. Ambassador Vanessa Frazier of Malta, who holds the Security Council’s rotating presidency for the month of April 2024, acknowledged the lack of objection to initiating the process and announced the Palestinian request would be given immediate consideration.

Earlier, the Security Council met in a private session to discuss giving renewed consideration to Palestine’s request for full membership, which it first entered on September 23, 2011. A second, public session was held in which the Security Council approved the proposal to reconsider Palestine’s application. Ambassador Frazier then referred the matter to the Security Council’s admissions committee for immediate consideration. Thus began a new phase of Palestine’s quest for full UN membership. … … …

***

Peter A. Dutton, “Challenging China: The Philippine Experience in the South China Sea,” U.S.-Asia Law Institute Podcast with Dr. Jay Batangbacal, New York University School of Law, 29 January 2024.

An obscure reef in the South China Sea has become the latest flashpoint in China’s long-running campaign to dominate the South China Sea. Since last summer, the Chinese Coast Guard has repeatedly employed water cannons, lasers, and acoustic weapons and rammed Philippine Navy and Coast Guard vessels to prevent them from resupplying military personnel positioned at Second Thomas Shoal. The U.S. labels China’s actions as violations of international law and has confirmed that its mutual defense treaty with the Philippines extends to attacks on Philippine vessels at sea. Jay Batongbacal, a lawyer and professor at the University of the Philippines College of Law, will discuss how this tiny maritime feature became a potential conflict site, why a 2016 ruling by an international tribunal in the Philippines’ favor has not ended the dispute, and how international law can continue to be effective in the face of Chinese attacks. Peter Dutton, an adjunct professor of international law at NYU School of Law, will be the moderator.

***

Peter A. Dutton, “Oceans Under Pressure: China’s Challenge to the Maritime Order,” Britain’s World (Council on Geostrategy: London, UK, 23 January 2024).

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) reflects a series of compromises between the ocean’s various stakeholders and seeks to preserve maritime stability by ensuring tensions do not build to the point of conflict. As it opened for signature in 1982, states began organising their maritime claims and activities around its four key elements (see Box 1), which transformed and stabilised the maritime domain. The People’s Republic of China (PRC), however, is systematically and dangerously undermining each of these foundational elements, threatening to return the global maritime domain to its former state of instability. If the UNCLOS system is to be preserved, states with important maritime interests, including the United Kingdom (UK), must reinforce its provisions with clear policy statements, support affected stakeholders actively, and employ stiffer action where required. Without such efforts, the future order of the oceans is in doubt.

The key elements of UNCLOS

Beginning in the early 20th century, advancements in military technologies, notably the capacity to drill offshore for oil and gas, and expanded industrial fishing, put pressure on states to establish international laws to regulate activities at sea. It was not until after the Second World War, however, that states were able to address these pressing issues. In 1982, negotiators completed a comprehensive treaty to provide order, stability, and sustainable productivity in the world’s oceans. To achieve these aims, UNCLOS advances four interwoven areas of international law.

First, it defines maritime zones and establishes the bases for delimiting them. It is the first international treaty, for instance, to establish a uniform maximum breadth of the territorial sea at 12 nautical miles and creates the 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) within which coastal states possess sovereign rights to the resources inside it. It provides a system to delimit maritime zones between neighbours based on coastal geography, international law, and equitable results. These important advancements brought rapid and substantial uniformity to maritime claims around the world and stability to what had previously been a global patchwork.

Second, UNCLOS defines the rights and duties which apply within its several maritime zones. It balances the security and economic interests of coastal states against the freedoms of maritime states to navigate and operate freely on the seas. In doing so, it provides for various passage regimes, including the right of innocent passage in the territorial sea, which requires ships to pass in an un-threatening manner, and transit passage, which grants ships and aircraft the right to pass through narrow coastal straits. In the rest of the oceans, it preserves the right of high seas freedoms, excepting only a coastal state’s right to the resources and related jurisdiction in its EEZ and continental shelf.

Third, UNCLOS establishes rules, standards, and norms to protect the maritime environment. It views the resources in and under the high seas as the ‘common heritage of mankind’. It gives coastal states jurisdiction to protect and preserve the marine environment and requires them to undertake measures to avoid over-exploitation of living resources. Further, it requires cooperation between neighbouring states to conserve living resources and to prevent marine pollution and other environmental damage. It requires environmental assessment prior to undertaking action which may cause substantial pollution.

Fourth, and finally, UNCLOS establishes a mandatory system to resolve disputes and advance maritime stability. It obliges states to settle disputes by peaceful means, allows parties to choose their own dispute resolution methods, and establishes processes among which states can choose to adjudicate disputes. It even lets states opt out of the most contentious types of disputes, such as those involving sovereignty over territory, military activities, and law enforcement. … … …

***

Peter A. Dutton, “The Naval Balance in the Indo-Pacific,” Sea Power Podcast, Episode 8, Isaac B. Kardon, U.S. Naval War College, November 2023.

Guest Peter Dutton discusses a paper delivered in Australia in November 2022, considering AUKUS, the Quad, and the naval capabilities that the PRC brings to bear in the Indo-Pacific theater.

***

Peter A. Dutton, “China is Rewriting the Law of the Sea,” (Review of China’s Law of the Sea, by Isaac B. Kardon, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), Foreign Policy, 10 June 2023.

Washington missed the boat to shape the global maritime order. Beijing is stepping in.

For decades, scholars and policymakers have puzzled over the question: What is China trying to accomplish with its extensive maritime claims throughout the South and East China seas?

A few answers are floated regularly: Perhaps Beijing wants to control natural resources. The South China Sea is a rich source of fisheries and other living resources, and it contains commercially viable hydrocarbon deposits. Or, perhaps, Chinese leaders seek security. After all, Beijing has constructed military bases on Woody Island in the Paracels and on all seven of the Spratly Islands that it occupies. Chinese leaders may also want to bolster Beijing’s status in the larger regional order by setting the maritime agenda and making the rules for dispute resolution.

But neither resource interests, security, nor status alone provide satisfactory explanations for Beijing’s behavior. Instead, as China analyst Isaac B. Kardon argues in his groundbreaking book, China’s Law of the Sea: The New Rules of Maritime Order, Beijing sees itself as fundamentally above the law and beyond accountability to others, especially smaller states. And while full-scale global change to the oceans regime is beyond China’s grasp, Kardon writes, Beijing’s actions may have consequences beyond its nearby waters.

The law of the sea—codified for decades in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea—is pretty clear on most things. Countries have territorial seas stretching 12 nautical miles off their coasts. Islands do, too. Rocks and submerged features do not. Countries also have resource zones that stretch at least 200 nautical miles, theirs alone to fish, mine, and harvest deep-sea riches. Every state can fly, sail, and operate in waters beyond the territorial seas and pass freely through straits. The problem is that China, though a party to the U.N. convention, flouts each of these elements.

China, as Kardon systematically demonstrates, challenges the prevailing law of the sea by undermining the geography-based rules for defining coastal zones, controlling ocean resources that belong to other states, hampering freedom of navigation, and ignoring its commitment to abide by dispute resolution provisions. … … …

***

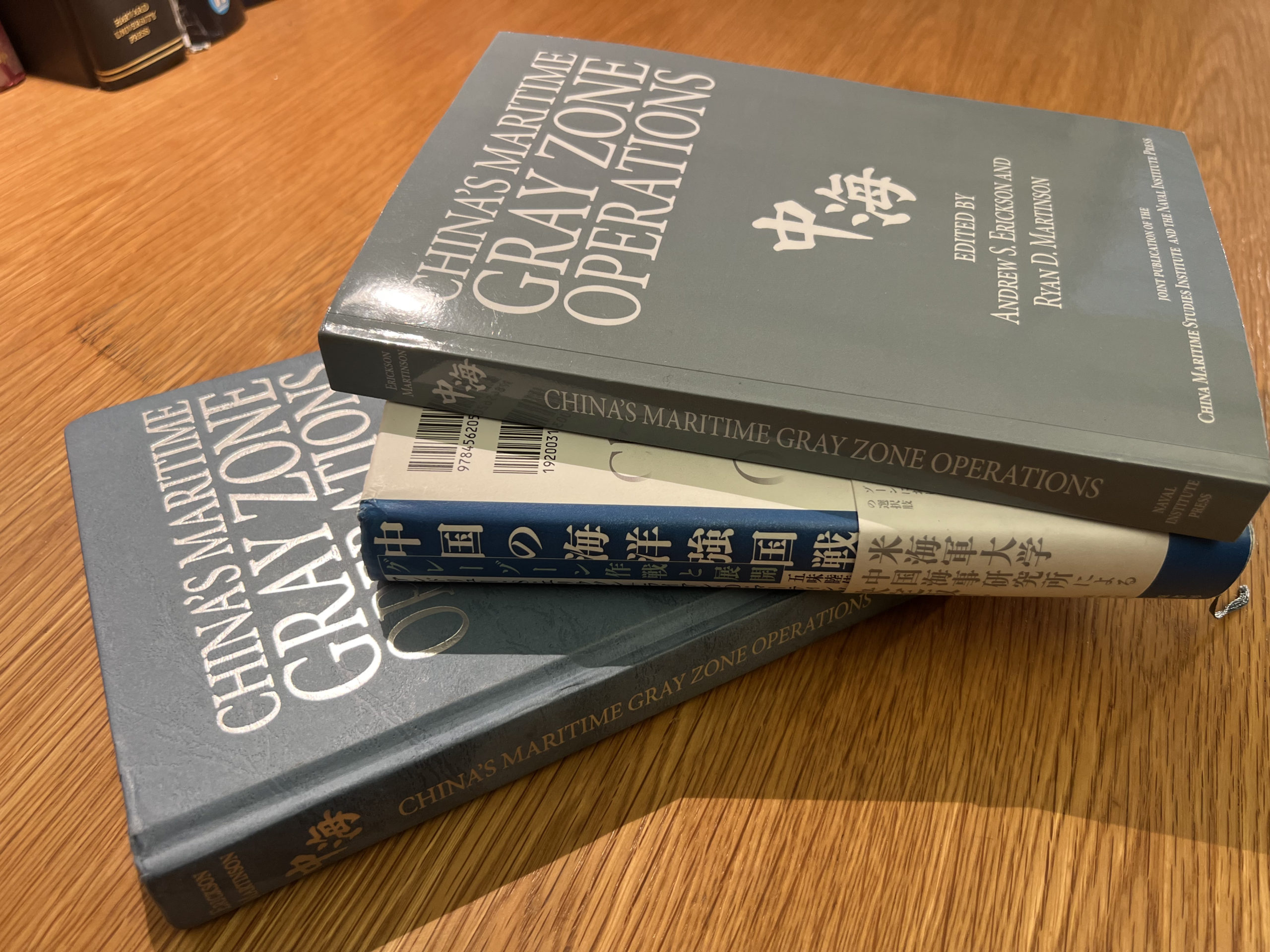

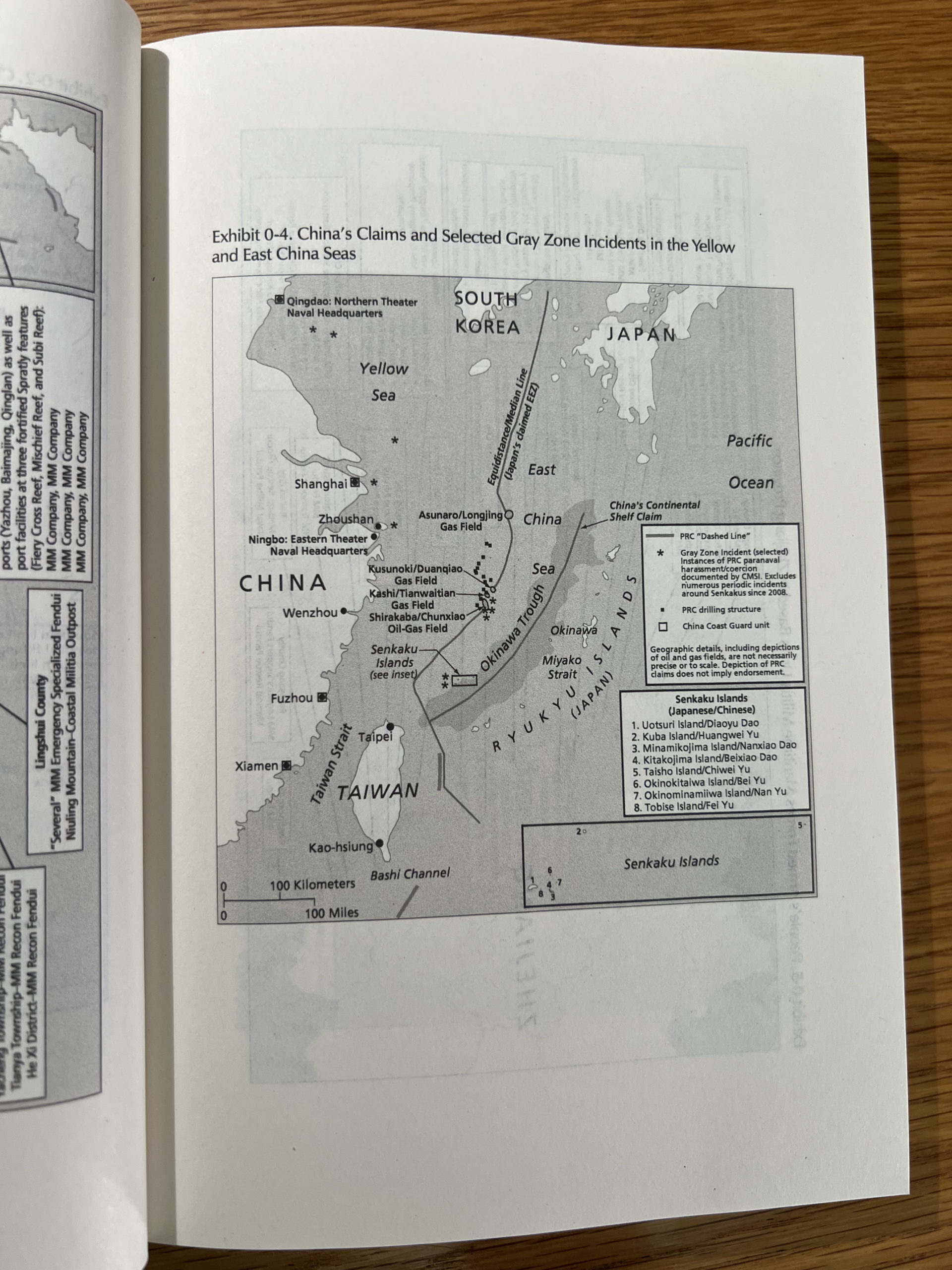

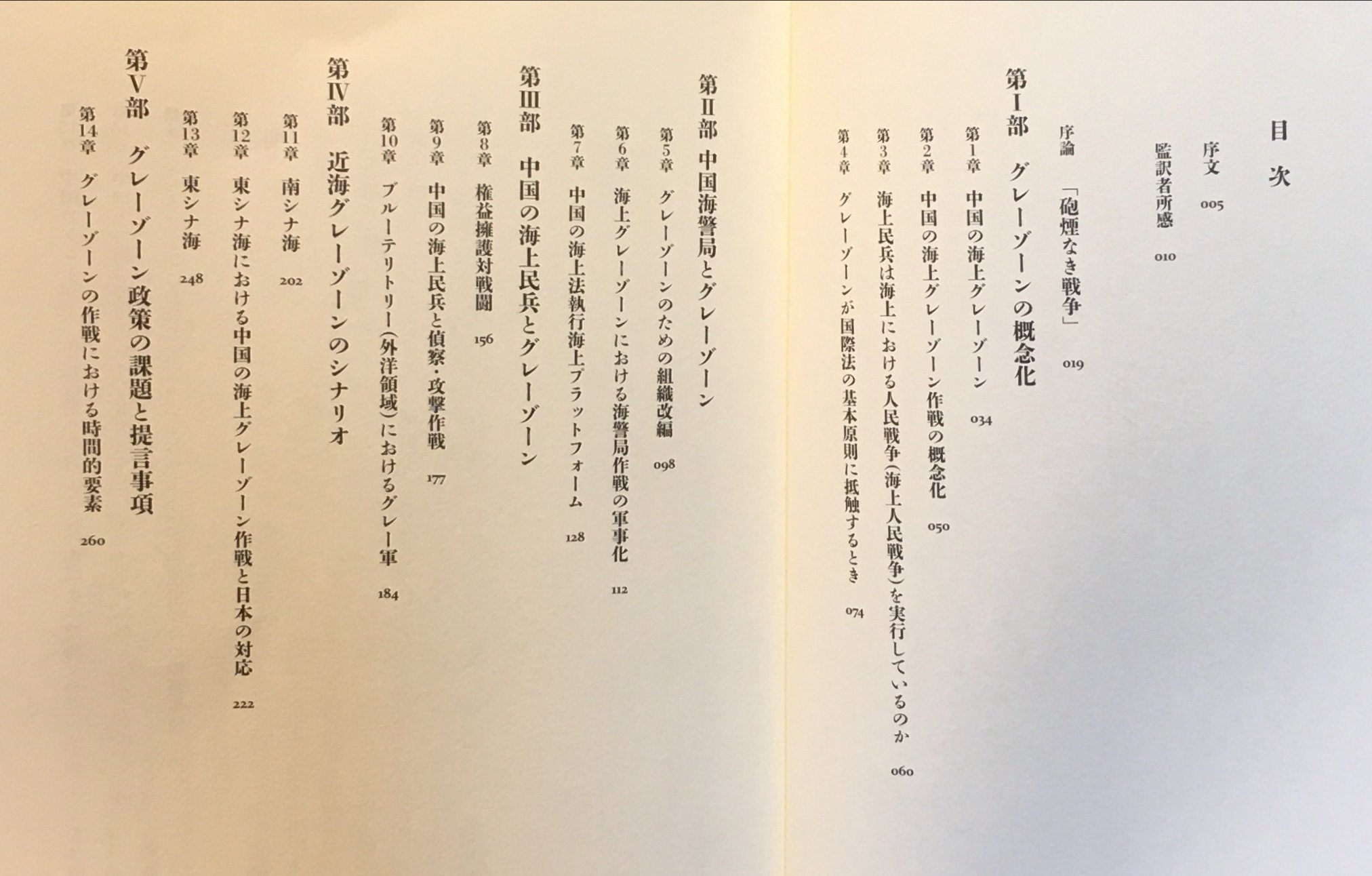

Peter A. Dutton, “Conceptualizing China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” in Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, eds., China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019; paperback 15 January 2023), 30–37.

- Reprinted in Japanese as:

- ピーター・A・ダットン(Peter A.Dutton)

退役米国海軍中佐および法務官、米国海軍大学中国海事研究所(CMSI)所長。 - 第2章 中国の海上グレーゾーン作戦の概念化

- アンドリュー・S・エリクソン (編集), ライアン・D・マーティンソン (編集), 五味 睦佳 (翻訳), 大野 慶二 (翻訳), 木村 初夫 (翻訳), 五島 浩司 (翻訳), 杉本 正彦 (翻訳), 武居 智久 (翻訳), 山本 勝也 (翻訳) [Andrew S. Erickson (Editor), Ryan D. Martinson (Editor), Gumi Mutsuka (Translator), Ohno Keiji (Translator), Kimura Hatsuo (Translator), Goto Koji (Translator), Sugimoto Masahiko (Translator), Tomohisa Takei (translator), and Katsuya Yamamoto (translator)]; 中国の海洋強国戦略:グレーゾーン作戦と展開 (日本語) [China’s Maritime Power Strategy: Strategy and Deployment in Gray Zone (Japanese translation of China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations)] (Tokyo: 原書房 [Hara Shobo Press], 2020), 50–59.

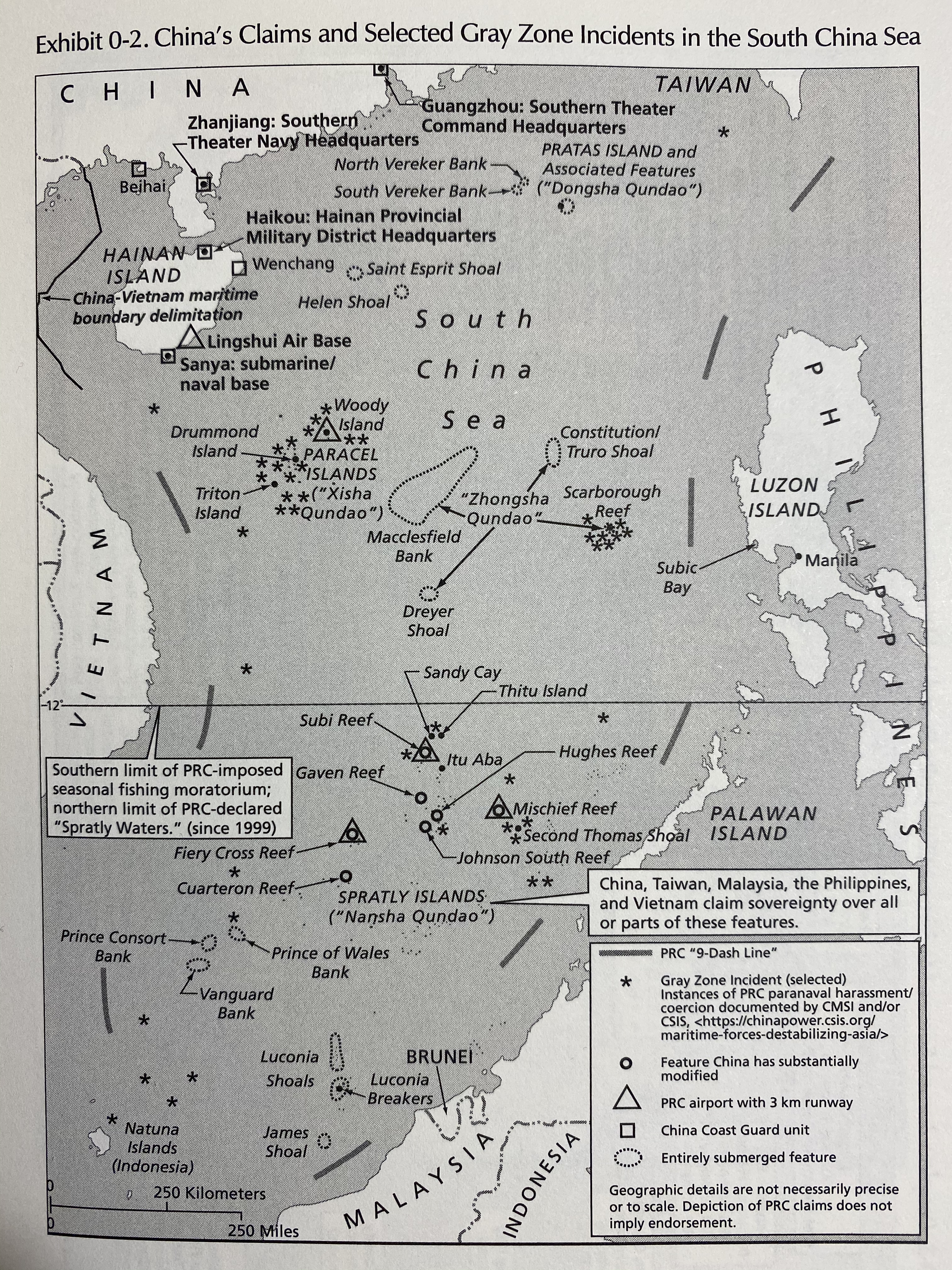

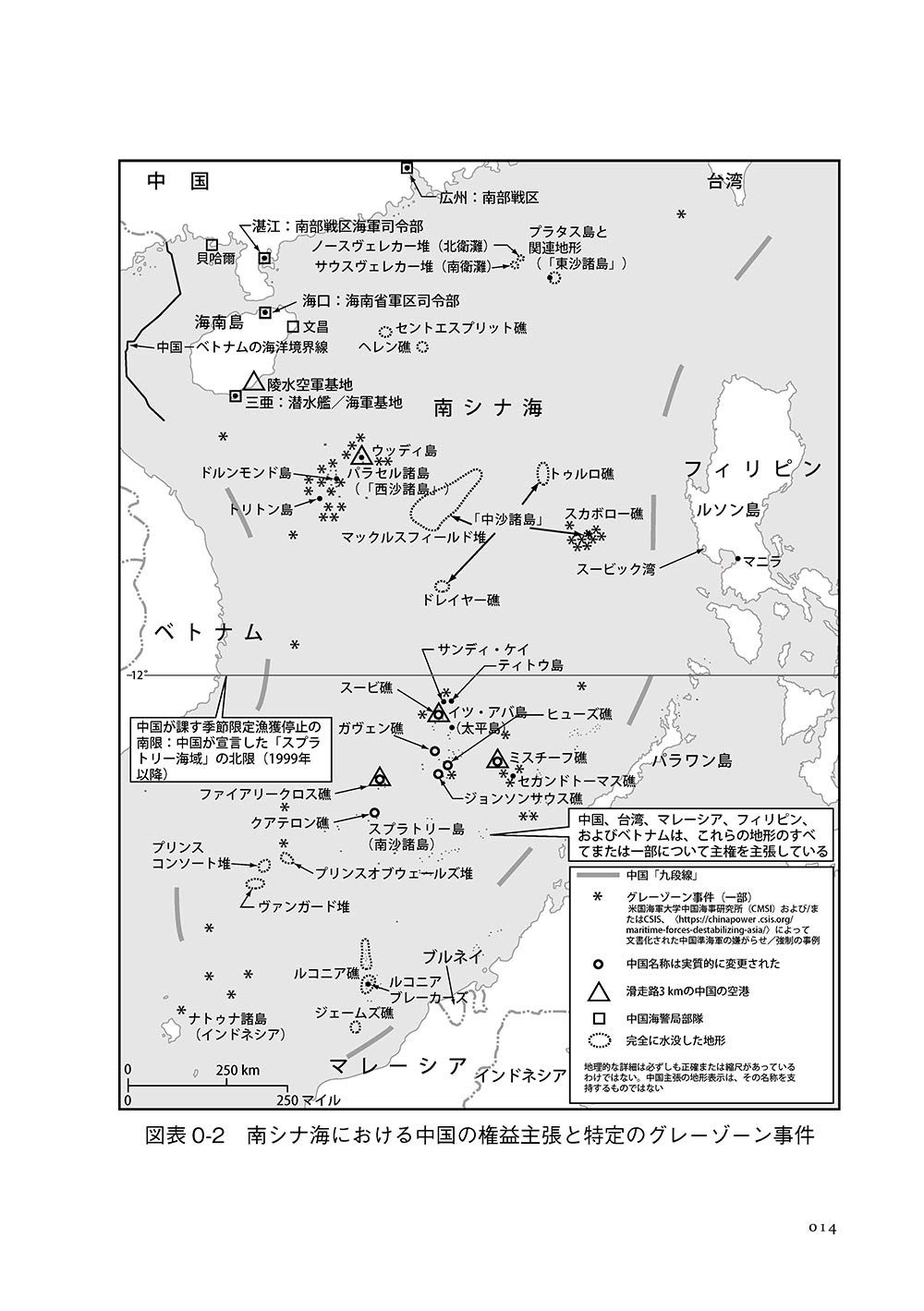

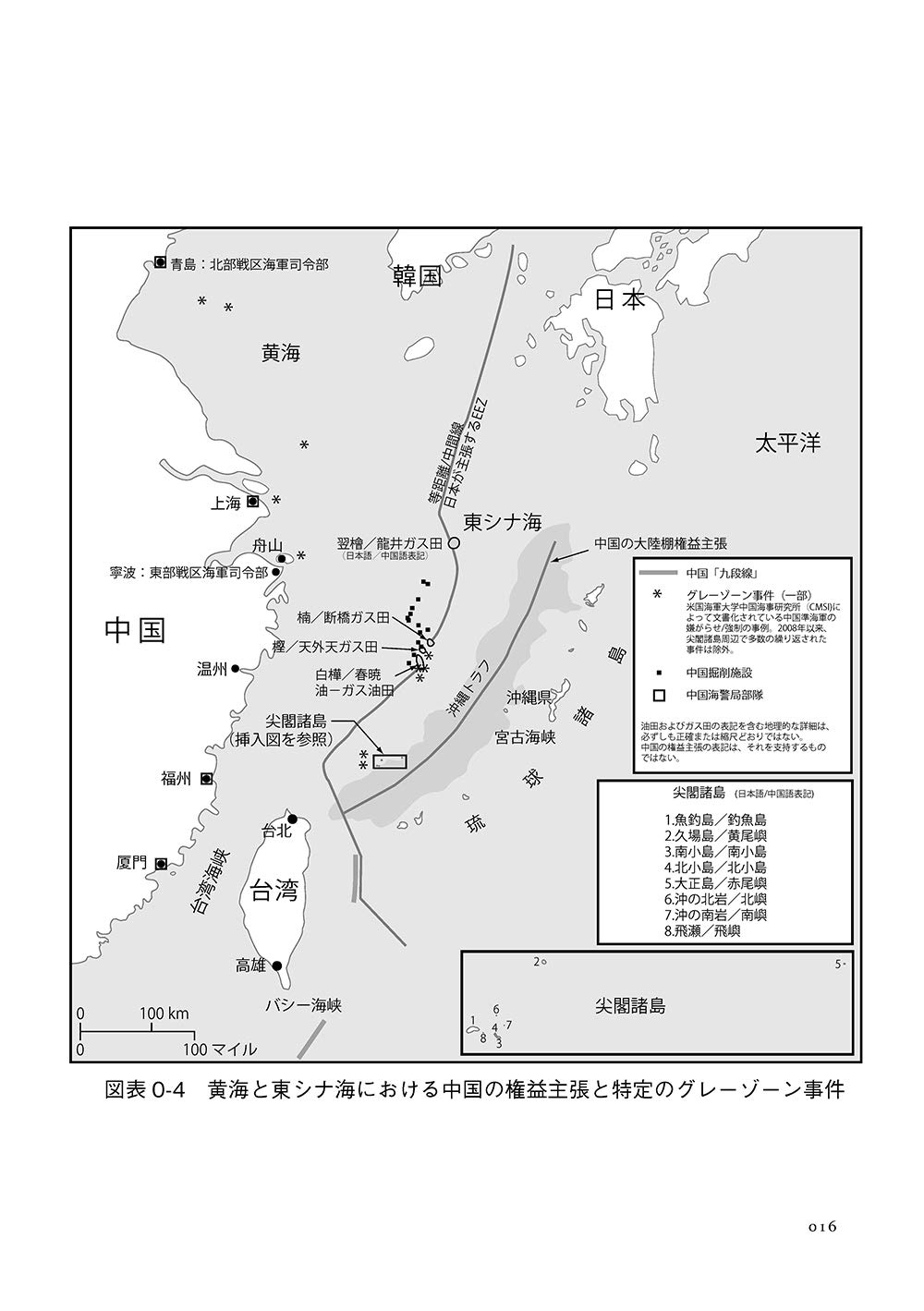

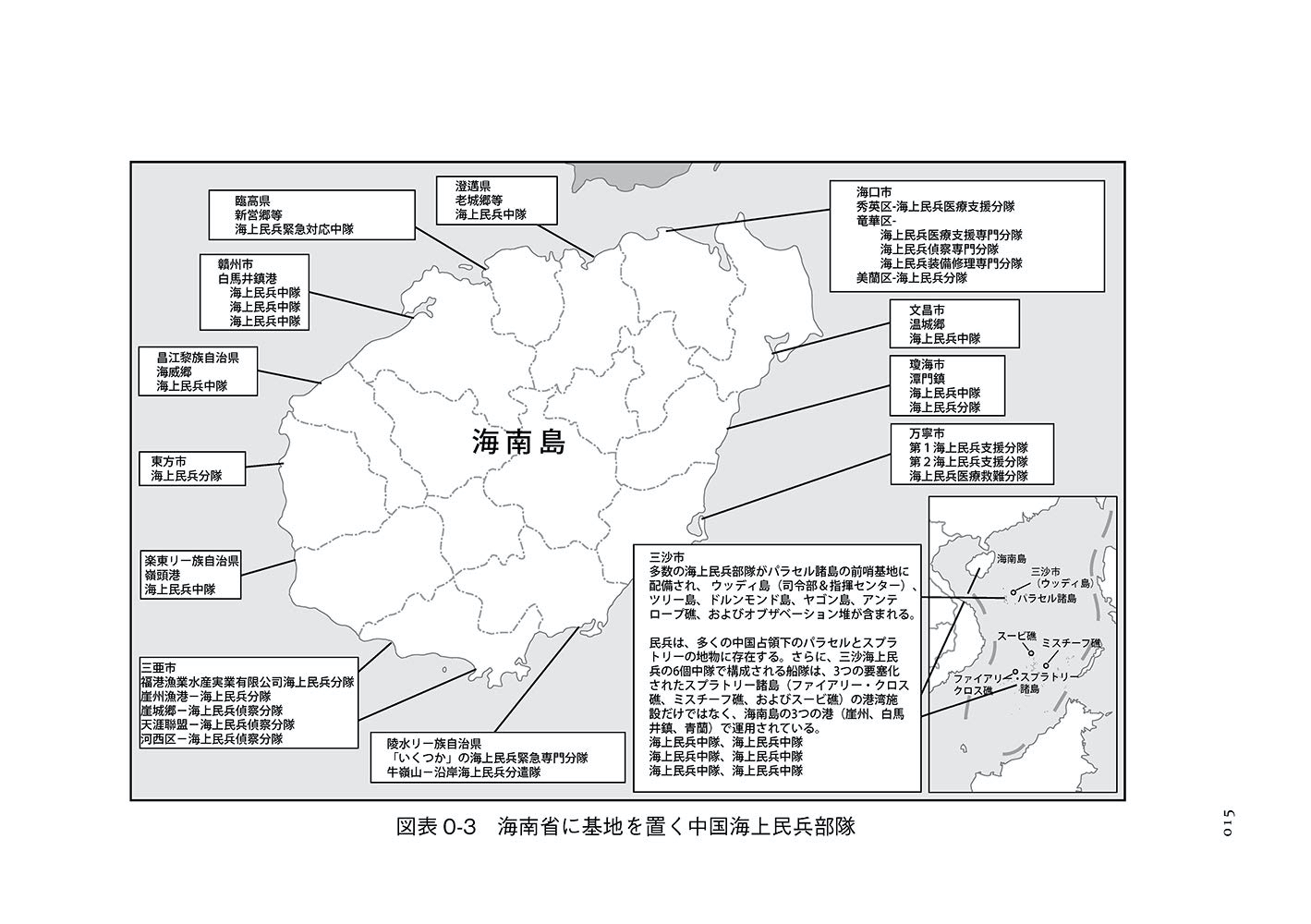

This volume is designed to grapple with an important aspect of the nature and form of the Chinese-led change occurring at sea in East Asia. Something new has been going on since at least 2012, when China employed a combination of coast guard cutters and maritime militia vessels to seize physical control of Scarborough Reef in the South China Sea. Even earlier, coordination among the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy (PLAN), China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels, and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) units was seen in the 2009 USNS Impeccable incident. Since then, the pattern has been repeated many times. It is, for instance, a central feature of the ongoing Chinese activities in the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute in the East China Sea. It was evident in China’s 2014 employment and shielding of the Hai Yang Shi You 981 drilling rig in the waters between Vietnam and the Paracel Islands. And it was central to China’s assertion of traditional fishing rights in the Indonesian exclusive economic zone off Natuna. This new phenomenon is China’s use of nonmilitarized coercion to achieve its maritime aims in the East Asian sea space.

As I wrote in 2013, China found a gap to exploit in resolving the disputes in the South China Sea in its favor. This gap exists in the space between peaceful dispute resolution options chiefly negotiations or institutional approaches to resolving the disputes-and armed conflict. China sought this gap after being foreclosed from other options. Bilateral negotiations, which it favored, went nowhere because China approached them on the condition that the other party accept Chinese sovereignty before proceeding. This and the obvious political and economic imbalance made bilateral negotiations unacceptable to the weaker parties. Similarly, China found multilateral negotiations unacceptable. It was unwilling to cede its position of power and did not want to link the outcome of negotiations with its overall relations with Association of Southeast Asian Nations states. Litigation, arbitration, or mediation were also unacceptable options to China, as its reaction to the Philippines’ South China Sea arbitration case demonstrated. There was simply too much to lose, both in the substantive aspects of China’s claims and in China’s increasing prerogatives as regional leader and rule setter.

At the same time, use of force to quickly resolve the disputes was too risky. The Philippines is a treaty ally with the United States, which might come to its aid if Beijing used force to resolve the territorial disputes between it and Manila.

Additionally, the overarching U.S. strategic objective for the region after the Cold War ended was to maintain stability. The omnipresent U.S. Seventh Fleet was there to see that military force was not used by any party to resolve any of the many disputes left over from World War II. Accordingly, like water flows toward a crack in cement, China’s policies toward its South China Sea disputes flowed naturally to the gap between peaceful dispute resolution and armed conflict. This is the gray zone-not peace, not war, but having attributes of each.

What is China trying to accomplish? What are the elements of the gray zone strategy? And why does it seem to be working? China’s fundamental objective is to project national power in all its dimensions into the maritime domain. There are at least three familiar subcomponents to China’s strategy. First, in terms of security, China is a continental power seeking a maritime buffer zone to enhance its security from threats from the sea. In this sense, China is advancing an interior security strategy by creating expanding rings of control, denial, and contestation beyond its coastline.

To do this, China seeks to create the conditions necessary to exercise increased sea control at least as far from its shores as is necessary to confront U.S. sea power before it can be projected ashore. This is the classic struggle between sea power and coastal defense. It is as old as triremes and cannon balls. What is different about this security strategy, however, is that at the same time as it seeks to expand its control over East Asian waters, China wants to avoid direct conflict. This strategy seeks to expand Chinese control over the East Asian littorals without provoking a kinetic response from any other state.

Second, China’s maritime power projection strategy also has a resource component. China is a resource-insecure state. Its policymakers wrestle with an enormous population, air and water pollution, declining ground water, increased desertification, and the lack of annual replacement of glacial mass on the Tibetan plateau to feed China’s key rivers. Chinese strategic documents repeatedly point to the oceans as an essential space for the future survival of the Chinese people. They are taught to believe there is a fundamental fairness in claiming for a population of nearly a billion and a half more sea space than international law currently allows. Law seems of little consequence to those who believe China is fighting for its survival. So, regardless of the law, China is expanding the waters that it claims a right to exploit for fishing and aquaculture. Similarly, China seeks to expand its control over nonliving resources on and under the seabed, especially hydrocarbons, although on this issue China seems to take a somewhat more compromising approach.

Third, China is a rising regional power seeking to project political influence into the maritime domain as one way to center regional relations around its own interests and preferences. As noted, Beijing is positioning itself as the rule maker in its relations with regional states. This is clear in its statements concerning the South China Sea arbitration, for instance. Additionally, China’s behavior in the Senkaku/Diaoyu crisis of September 2012 was consistent with enhancing the regional credibility of Chinese power. In response to the Japanese government’s purchase of three of the islets, China chose to escalate the political significance of that sovereignty dispute both internally and externally. To demonstrate that China’s policies had the strong support of its citizens, Chinese newspapers throughout September were filled with the minute details of each side’s actions and focused especially on the change China was creating at Japan’s expense. The articles commanded the attention of the Chinese people and built support for the Chinese Communist Party’s policies. Externally, the Chinese filled the waters around these small islands with coast guard ships and fishing vessels in a campaign that remains unabated to this day. The effect was to successfully challenge Japanese exclusive control over the Senkaku Islands. This was an external signal that China no longer needed to accept a secondary status in the political order of East Asia.

These are at least some of the aims of China’s strategy. There may be others, and this volume offers multiple perspectives. But what are some of the elements of the strategy? … … …

***

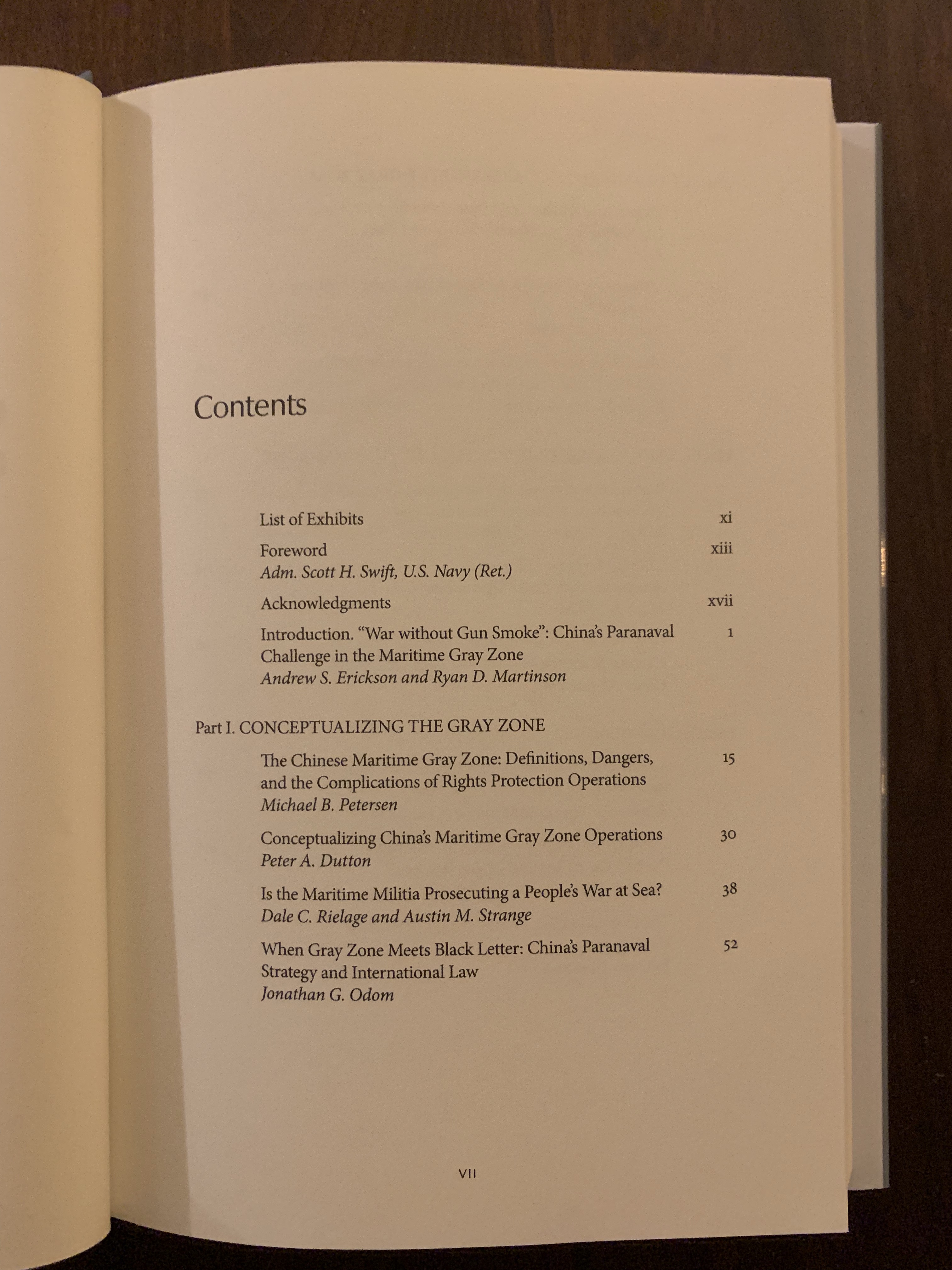

Peter A. Dutton, “Introduction, Deterrence: Selected Articles from the Naval War College Review,” Naval War College Newport Paper 46 (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2021), 1–6.

Volume Information

The subject of deterrence fell away from the forefront of American strategic thinking during the three decades following the fall of the Soviet Union. Our ability to deter much weaker states by denying them the ability to achieve their aims was long assumed. But today there is a new global security situation that makes it imperative for American military officers and security specialists to begin to relearn the fundamental tenets of this aspect of national security.

The purpose of this volume is to contribute to that campaign of learning by drawing on some of the excellent scholarship published in the Naval War College Review during the Cold War and the decades since. Some of the articles included here lay out a few of the fundamentals of the theories of deterrence.

Introduction

The subject of deterrence fell away from the forefront of American strategic thinking during the three decades following the fall of the Soviet Union. Our ability to deter much weaker states by denying them the ability to achieve their aims was long assumed. But today there is a new global security situation that makes it imperative for American military officers and security specialists to begin to relearn the fundamental tenets of this aspect of national security.

The purpose of this volume is to contribute to that campaign of learning by drawing on some of the excellent scholarship published in the Naval War College Review during the Cold War and the decades since. Some of the articles included here lay out a few of the fundamentals of the theories of deterrence. A notable aspect of these articles is how similar the challenges of deterring the Soviet Union were to the challenges of deterring China and Russia that we face now. A second purpose of this collection is to describe and assess some of the practical aspects of deterrence in East Asia and Europe today. But despite its scope, this volume only can begin to educate the reader about the complex and well-developed theories and practical requirements of deterrence. Accordingly, a third purpose of this volume is to whet the reader’s appetite to learn more and, from a base of knowledge and in light of professional experience, to contribute new thinking to the literature on deterrence.

Indeed, more study will be needed if we are to perpetuate for another generation the freedom from direct attack by another country that the United States has enjoyed over the past seventy-six years. Our security since the end of the Second World War has been no accident. Well before the conclusion of that devastating conflict, American strategists were planning to win the peace. In the years just prior to the war, Nicholas J. Spykman, as chairman of Yale University’s Department of International Relations and director of the Yale Institute of International Studies, developed the fundamental outlines of the system of American-led global security.1 That system enabled an unparalleled period of global security and economic development and suppressed direct conflict between great powers.

Spykman developed his theories of security after watching two great powers—Germany and Japan—rise in Europe and Asia in the first half of the twentieth century and, in rising, initiate two global wars during which American soil was attacked and American lives were lost. Spykman’s system of security rested on the premise that the United States is most secure when no regional great power can consolidate a position of primacy in either Europe or Asia and by so doing project power outward to attack the United States or curtail American access to the trading system of Eurasia.

To ensure in each region of Eurasia that no country or combination of countries could threaten America and its interests, American power—resident in Europe and Asia—would maintain stability by entering into alliances with like-minded states.2 These regional alliance systems would retain either a regional preponderance of power or at least a sufficient balance of power to deter conflict (see figure). In combination, these regional systems guaranteed that American power could underwrite global security. Further, maintaining resident forces in Europe or Asia required free access to the global commons to ensure that the United States could trade freely with Eurasian states and could deploy forces across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to shore up its forward-deployed forces as necessary.

Spykman’s premises informed America’s decision after World War II to remain engaged in the world rather than retreat to the isolation of the North American continent. The global strategic posture he outlined led to the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in Europe and to a system of bilateral alliances in East Asia with Japan, the Republic of Korea, Australia, the Philippines, and Thailand. American forces in the region built on these alliances to add a system of partnerships with other states interested in maintaining stability, free trade, and national development. Since 1950, defense of this system has been and remains the most important reason for the American policy of preventing mainland China from taking over Taiwan by force. Deterring a Chinese attack on Taiwan continues to be a central organizing purpose of U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific region. The offshore alliances and partnerships that extend along the island chain from the Japanese islands through Taiwan and the Philippines to Australia enable American naval and air forces resident in Asia to ensure regional security and contribute to global stability.

Today, however, China’s rise in Asia and its entente with Russia, which straddles Eurasia, threaten this American-led system of security. Russian naval developments pose a threat to the American homeland and endanger our ability to project forces across the Atlantic.3 China’s rapid and comprehensive military development is focused on bringing Taiwan under its control, severing the American geostrategic position in Asia, and enabling China to advance the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy’s goal of global expansion with fewer limitations.4 Disruptive actors in western Asia and the Middle East, such as Iran and Syria, also threaten stability there.

With these developments, America and its allies no longer enjoy military primacy in any key region of the world beyond the Western Hemisphere, and they struggle to retain a balance of power in Asia in particular. Since the American-led security system is global, fault lines in one region cause tremors across the entire system. Accordingly, successive American administrations have deterred China from using military force to attack Taiwan and thereby disrupt the order on which regional and global stability and American security depend.

However, memories of how best to deter a peer or near-peer competitor have dimmed since America and its allies undertook to deter aggression by the Soviet bloc. Deterrence is not simply a matter of “overmatch”—a term used too often in the Pentagon today. Of course, deterrence involves careful force structure and military planning, but it also involves a deep understanding of a potential adversary’s motives, interests, and objectives. It can involve all elements of national power. It certainly involves careful political signaling, publicly and privately. And it involves the underappreciated factor of restraint and “off-ramps.” Deterring a potential adversary requires the implicit reassurance that negative consequences will be avoided as long as key lines remain uncrossed. It may be enhanced by positive opportunities as well as negative guarantees. The chapters of this volume begin to address some of these attributes of nuclear and conventional deterrence.

The volume begins with Jack Raymond’s lecture to the Naval War College’s Naval Command Course, “The Influence of Nuclear Weapons on National Strategy and Policy.” Raymond observes that “one of the recurrent national mistakes of the United States has been to underestimate the will and capacity of other countries to outperform it in industrial, technological, and scientific fields.” Deterring our adversaries requires us to understand them—words that seem all the more prescient today since Raymond was lecturing in 1966 about the inevitability of confrontation between the United States and China. He warns that in Asia, “deterrence and containment, in order to have any chance of being effective, [require] sizeable ground and naval forces as well as nuclear air power.” Raymond cautions against the dangers of neglect of the strength of conventional forces and too much reliance on nuclear deterrence, recalling how “Admiral Felt[,] taking command of the Pacific forces in 1958, just as the Taiwan crisis broke, [found] that he had only a limited supply of conventional explosives. In war, the Fleet would either have had to remain virtually inactive or attack with nuclear bombs.” Some theorize that this situation actually could serve to deter an opponent, since to defend its interests the United States would have no choice but to escalate. From our historical remove, however, that seems a dangerous assumption indeed.

The next several chapters pick up this thread of the role of nuclear weapons in deterrence. The eminent scholar Colin Gray, in “Defense, War-Fighting and Deterrence,” addresses the concept of deterrence through denial—that is, preventing an enemy from achieving its objective through the use of force. One Soviet theory of victory at the time anticipated that if through a nuclear exchange the Soviet Union could destroy the United States, it could eliminate its chief global rival and thus emerge damaged but victorious. Gray responds with the concept of deterrence through resilience—that is, America could win by surviving. But to deter nuclear conflict, the United States would need to commit to comprehensive resilience programs, including “civil defense, air defense, BMD [ballistic-missile defense], and offensive forces,” to ensure that the Soviet Union could not defeat it completely. While this may be a good strategy for homeland defense, Gray does not address how this strategy might apply to those allies whom we have pledged to defend from nuclear attack, a concept known as extended deterrence. Donald Snow, in “Strategic Uncertainty and Nuclear Deterrence,” answers Gray’s essay directly, arguing that nuclear wars are likely to destroy utterly all societies that engage in them. In Snow’s view, to ensure that nuclear wars never will be fought, they must be considered unwinnable. He argues in favor of a posture of mutually assured destruction so that if great-power rivals “know with certainty that an attack will result in a crushing counterattack, then neither can ever calculate advantage from initiating a nuclear war and both are deterred.”

Edward Ohlert, in an award-winning Naval War College student essay entitled “Strategic Deterrence and the Cruise Missile,” observes that in the face of “persistent pressure of a vigorous Soviet [nuclear] procurement program, U.S. perceptions of deterrence have evolved from ‘clear superiority’ through ‘mutual assured destruction’ to ‘flexible response options.’” But Ohlert offers that the Soviet Union pursued a “deterrent strategy based primarily upon demonstrated capability to reestablish strategic equivalence.” In other words, the Soviet goal was not mutually assured destruction but to “guarantee that, in postwar conditions, the opponent does not have sufficient unopposed reserve nuclear forces to conquer the world,” so a situation of parity would resume. On the topic of parity, Jerome Burke, in “‘Analogous Response’: The Cruise-Missile Threat to CONUS,” discusses how the Soviet Union’s failure to get American agreement to withdraw cruise missiles from Europe led it to develop advanced weapon systems, including submarines armed with nuclear or ballistic missiles, which the USSR positioned stealthily off the American East Coast. Burke argues that today “Putin has reasserted the Soviet strategic objective of holding the continental United States . . . at risk with now-combat-proven land-attack cruise missiles . . . and modern, difficult-to-detect submarines.” He concludes that a core part of Russia’s deterrence doctrine is to “hold the United States under a nuclear threat equal to that which the United States and NATO pose to Russia.”

Moving to essays about the utility of naval power to deter actions across the spectrum of conflict, we have George Lindsey’s chapter, “The Place of Maritime Strength in the Strategy of Deterrence,” in which he reminds us that strategic nuclear war is not the only deterrent object of military forces. Naval forces have a role in deterring the full range of conflict that includes tactical nuclear warfare, conventional war, and “situations less than war.” Picking up on this last concept, Hunter Stires, in “‘They Were Playing Chicken,’” looks back in time at the activities of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet from 1937 to 1940. Japan and China were at war; the United States was neutral but had interests in the battle space. To secure American strategic objectives, a mission-command culture was fostered to encourage independent action and judgment at the tactical level. Stires relates this prewar period to the situation today in the South China Sea, noting that in the late 1930s such tactical deterrence was sufficient to achieve American strategic objectives without causing unwanted escalation. While this approach may have been effective before the introduction of nuclear weapons, it will be fair for readers to consider whether such mission command today could result in tactical brinkmanship that would lead to unwanted escalation.

The last three chapters in this volume address various aspects of conventional deterrence in relation to potential conflict across the Taiwan Strait. Sam Goldsmith, in “U.S. Conventional Access Strategy,” addresses the key question of the value of the object, asserting that China’s “leadership appears unconvinced that the United States would risk a conflict with China—one that could escalate to a nuclear war—over disputes concerning territories that geographically are distant from the U.S. mainland and seemingly are unrelated to core U.S. national security interests.” The word seemingly is key here. Has the United States clearly and effectively communicated the value of the object? Do Chinese leaders understand how, in American minds, Taiwan relates to the American-led global system of security and stability? Goldsmith concludes that “[w]ithout clear U.S. deterrence, the risk of miscalculation only will increase.” He then lays out the developments needed to enhance our regional force posture to achieve assured conventional access to “return the China-U.S. strategic deterrence calculus to a more stable equilibrium.” More should be said, however, about how clearly American leaders communicate American interests in Taiwan’s status.

Like Goldsmith, Jeffrey Kline and Wayne Hughes, in “Between Peace and the Air-Sea Battle,” offer advice on how to deter China from initiating a cross-strait war. They argue that at least until necessary force-structure advances are made to achieve assured conventional access, a “war at sea” strategy can deter Chinese aggression; or, if deterrence fails, it can deny China use of the sea inside the first island chain while the United States and its allies execute a distant blockade. Finally, Naval War College professor William Murray places one additional piece in a conventional cross-strait deterrence puzzle in “Revisiting Taiwan’s Defense Strategy.” Whether the United States prepares to fight in close, as Goldsmith describes, or at a distance, as Kline and Hughes lay out, in either scenario deterrence is enhanced if Taiwan’s defenses prevent or delay PLA forces from establishing a lodgment on the island. Echoing Gray’s advocacy for the deterrent effect of resilience, Murray advises Taiwan to undertake a “porcupine defense” by hardening key facilities, building redundancies into critical infrastructure, stockpiling critical supplies, and undertaking other military and civilian programs to extend the time during which Taiwan can withstand a PLA onslaught until the United States and other like-minded states can come to the island’s aid.

These articles are brought together to help readers begin the campaign of relearning the fundamentals of deterrence in a world in which peer and near-peer competitors once again are key actors. Those whose ambition is to learn more deeply about deterrence might begin with classics such as Thomas C. Schelling’s Arms and Influence and The Strategy of Conflict, Richard K. Betts’s Nuclear Blackmail and Nuclear Balance, and Herman Kahn’s On Escalation. These readings will confirm that deterrence is a complex business. But if the United States and its allies are to avoid great-power conflict in this century and retain for another generation the global posture that has served our interests so well, we must commit to mastering the subject.

***

Isaac B. Kardon, Conor M. Kennedy, and Peter A. Dutton, Gwadar: China’s Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan, China Maritime Report 7 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, August 2020).

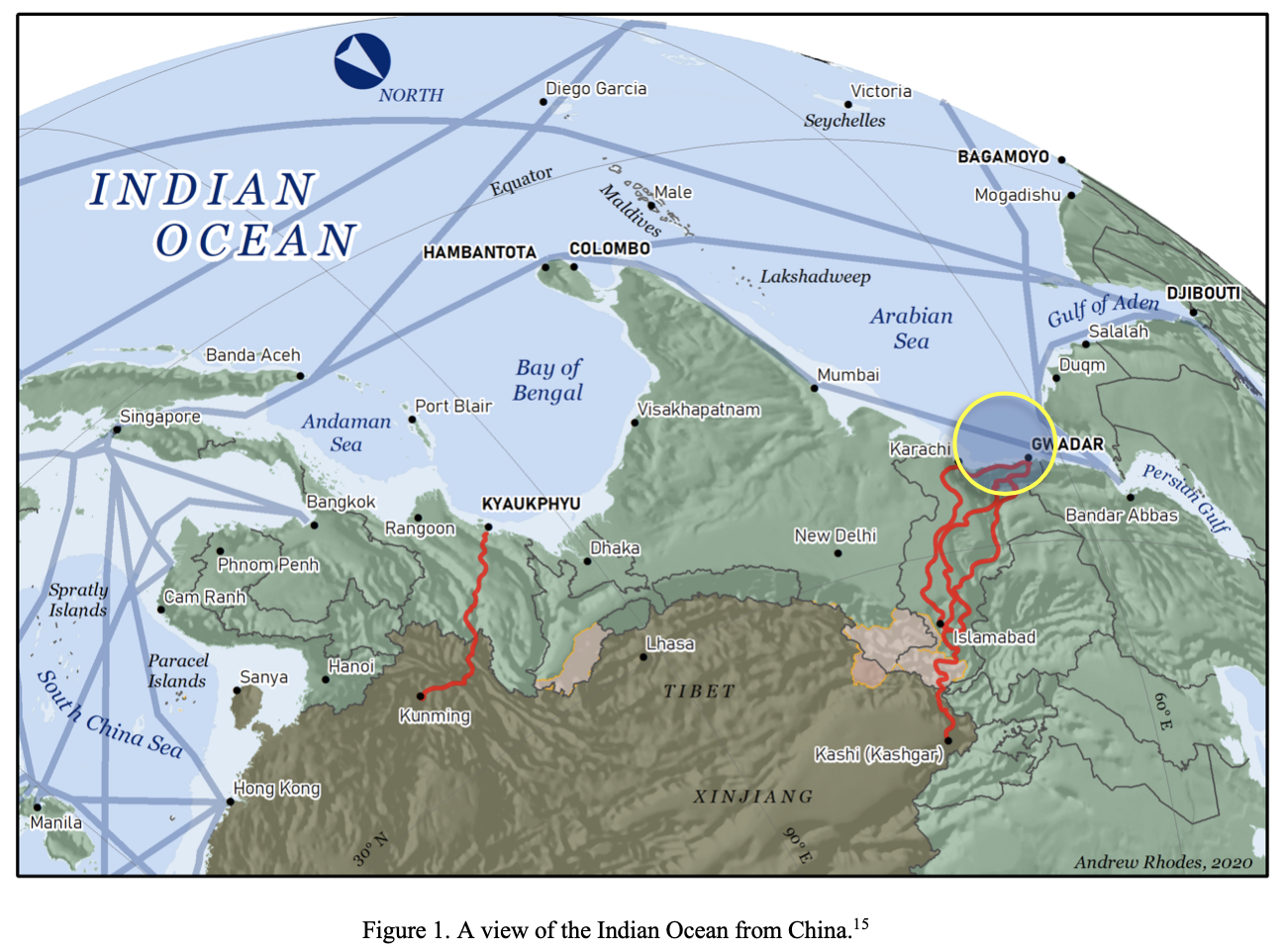

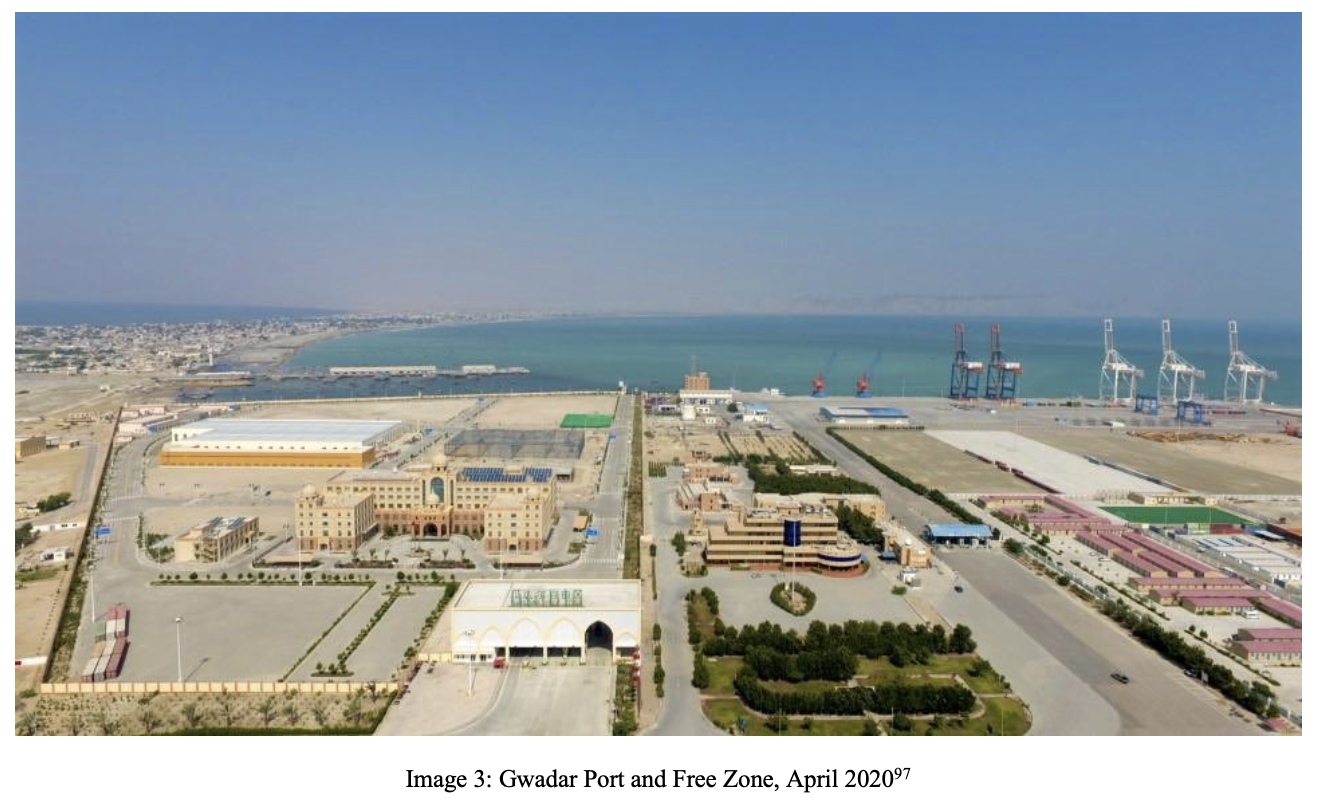

China Maritime Report No. 7 offers a detailed examination of China’s infrastructure project in the port of Gwadar, Pakistan. Written by Dr. Peter Dutton, Dr. Isaac Kardon, and Mr. Conor Kennedy, this report is the second in a series of studies looking at China’s interest in Indian Ocean ports and its “strategic strongpoints” there (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms.

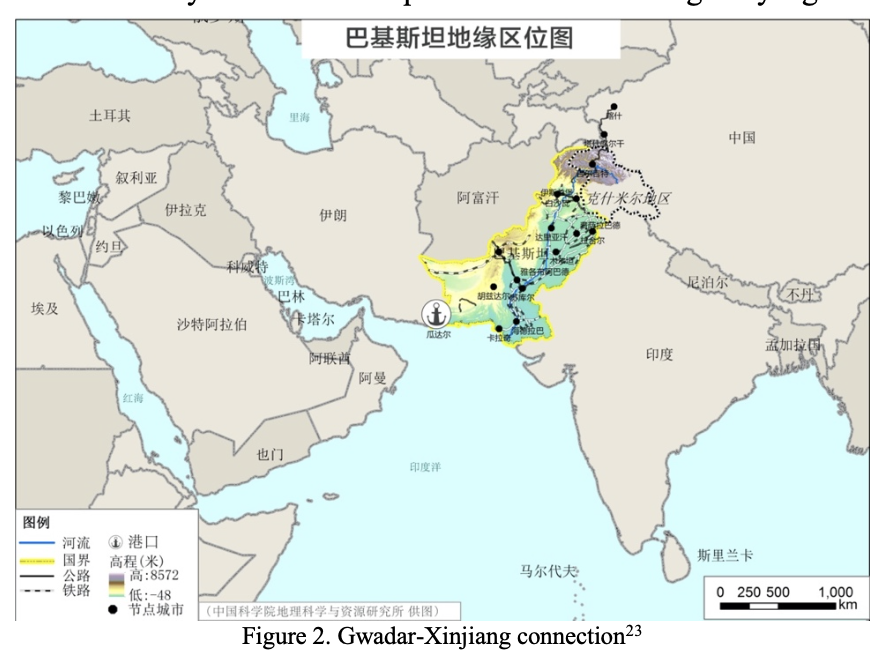

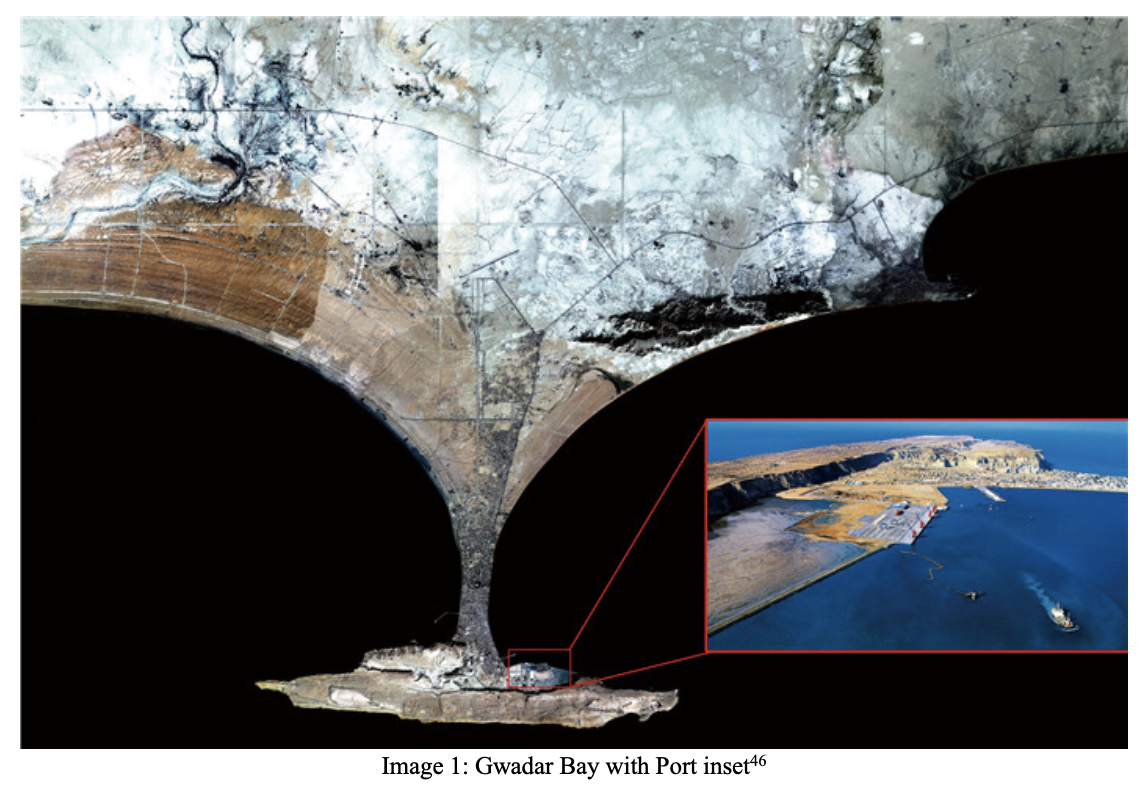

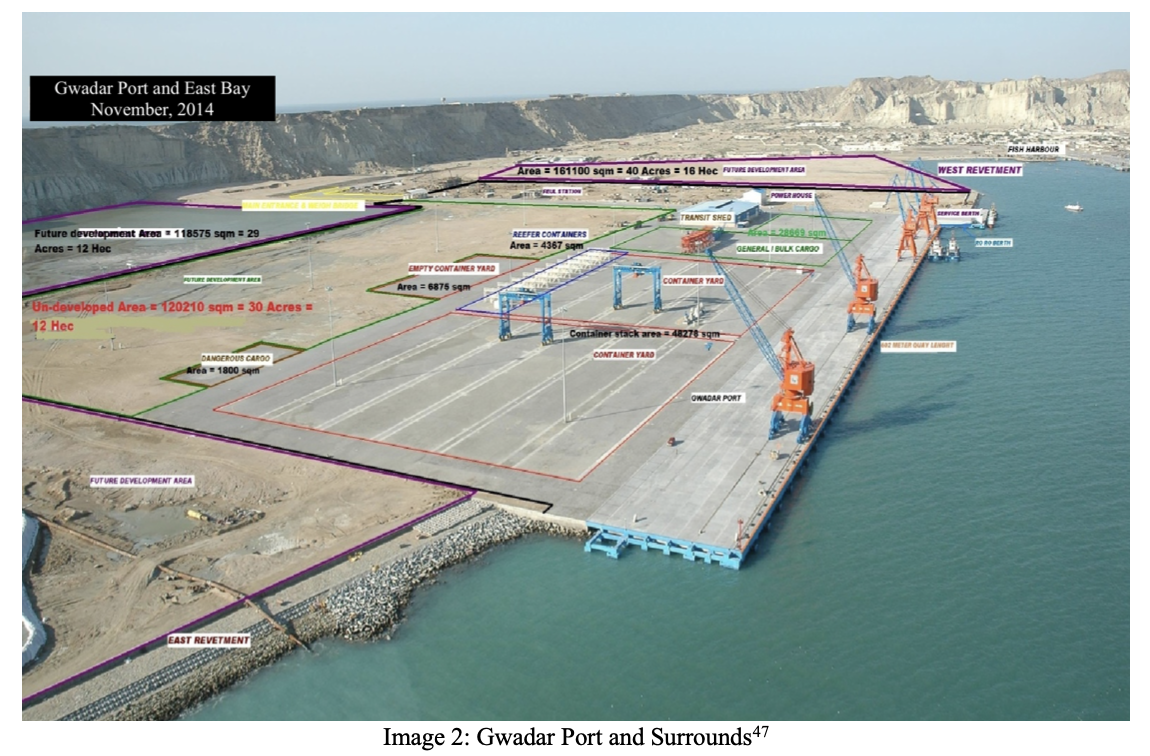

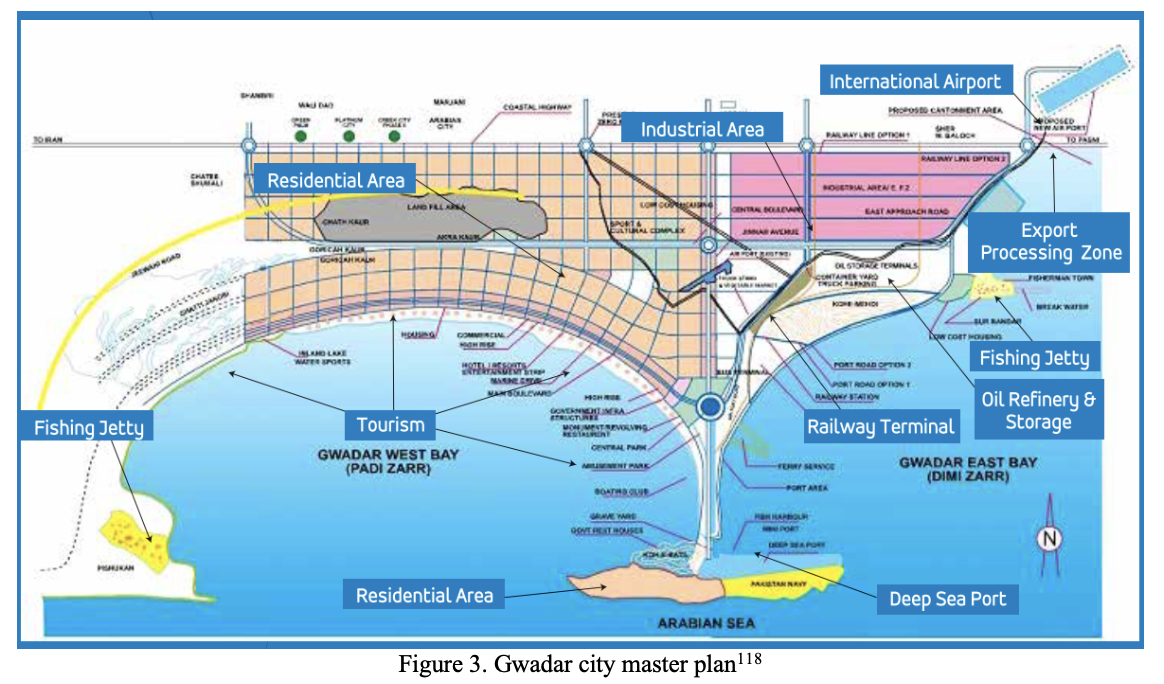

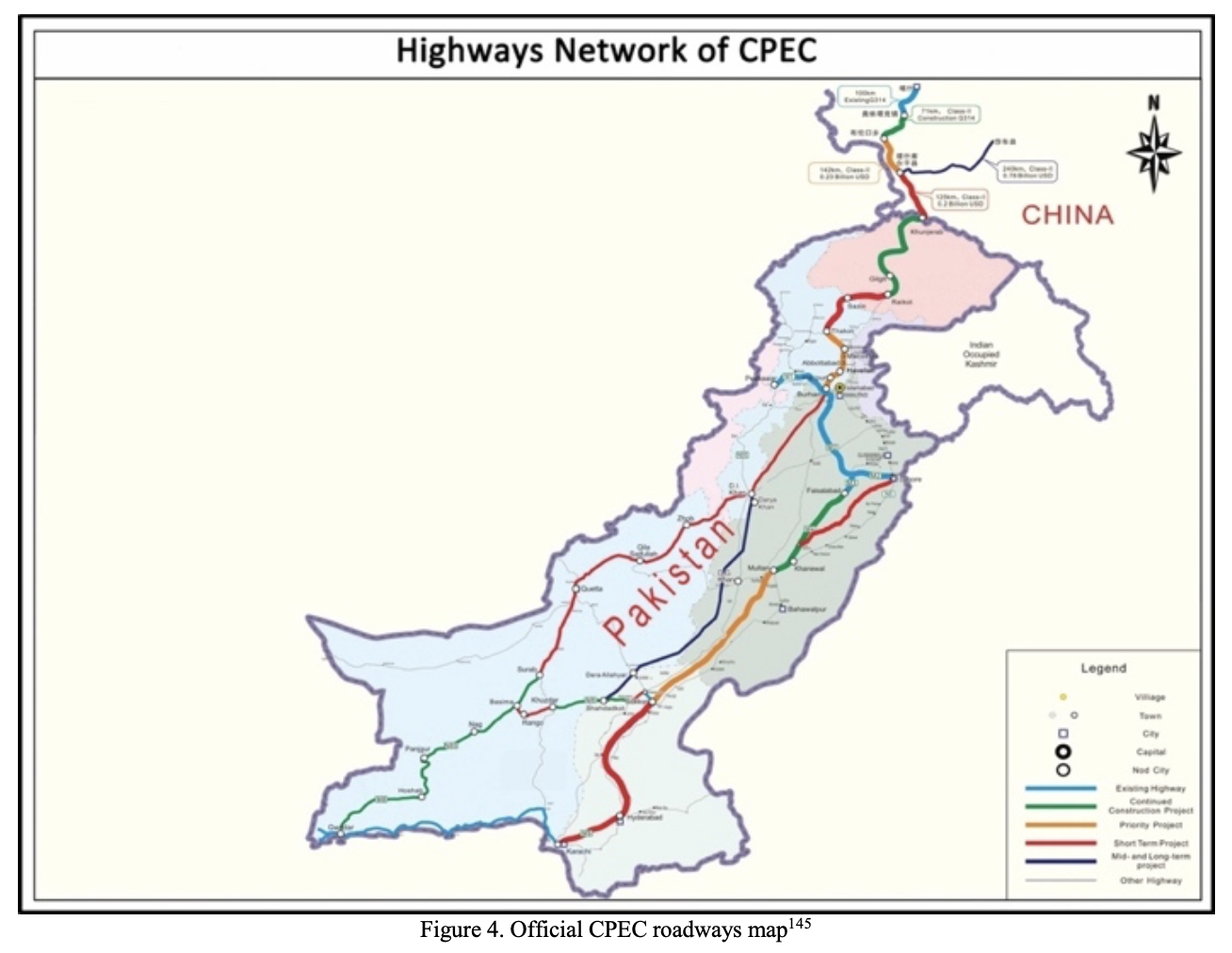

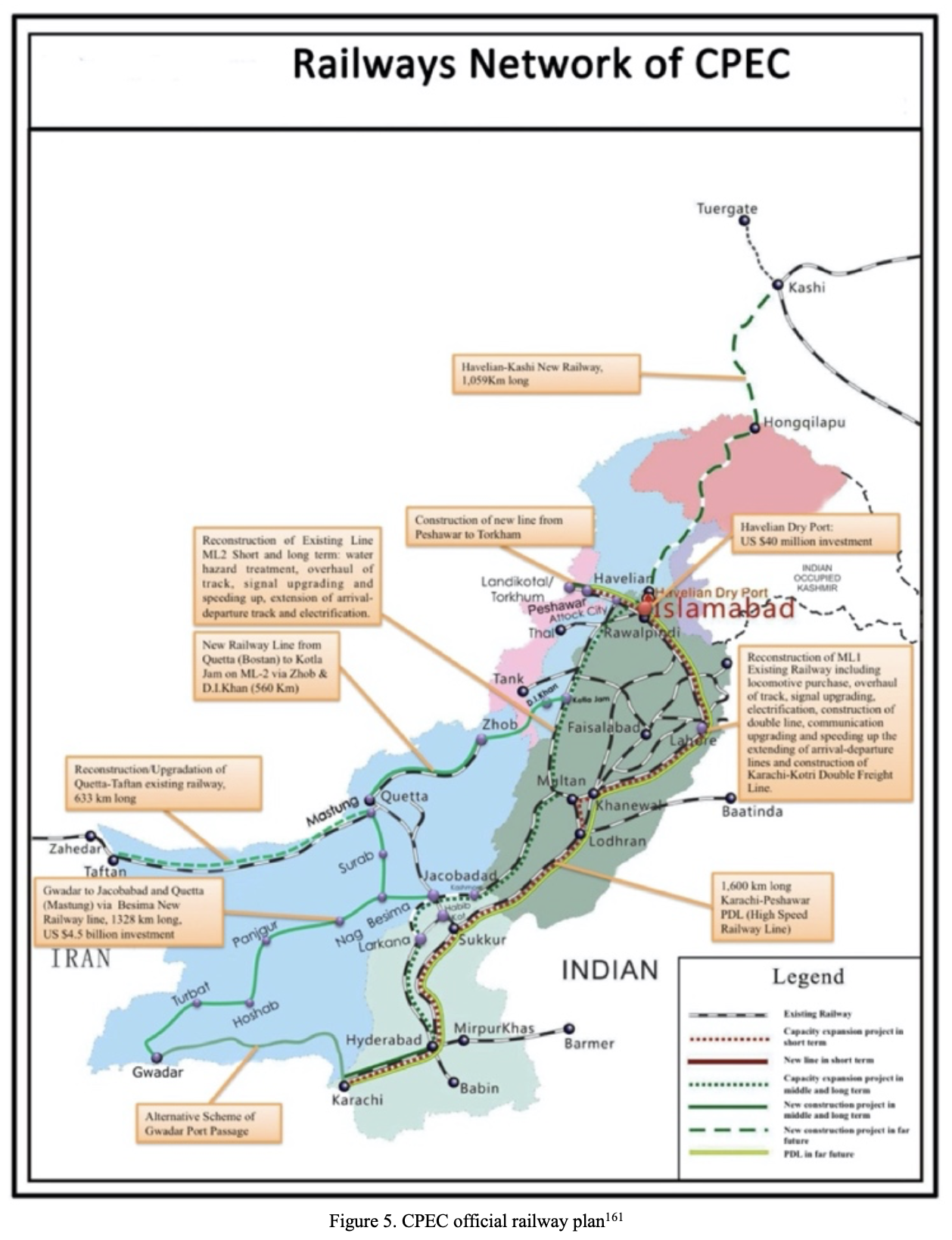

Gwadar is an inchoate “strategic strongpoint” in Pakistan that may one day serve as a major platform for China’s economic, diplomatic, and military interactions across the northern Indian Ocean region. As of August 2020, it is not a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base, but rather an underdeveloped and underutilized commercial multipurpose port built and operated by Chinese companies in service of broader PRC foreign and domestic policy objectives. Foremost among PRC objectives for Gwadar are (1) to enable direct transport between China and the Indian Ocean, and (2) to anchor an effort to stabilize western China by shoring up insecurity on its periphery. To understand these objectives, this case study first analyzes the characteristics and functions of the port, then evaluates plans for hinterland transport infrastructure connecting it to markets and resources. We then examine the linkage between development in Pakistan and security in Xinjiang. Finally, we consider the military potential of the Gwadar site, evaluating why it has not been utilized by the PLA then examining a range of uses that the port complex may provide for Chinese naval operations.

Key Findings

- Chinese analysts view Gwadar as a top choice for establishing a new overseas strategic strongpoint, owing to its prime geographic location and strong Sino-Pakistani ties. Many PLA analysts consider Gwadar to be a suitable site for naval support.

- China’s interest in Gwadar—and in Pakistan’s economic development in general—does not depend primarily on commercial returns. Instead, the Gwadar project is best understood as a mode of strategic investment in China’s internal and external security.

- Externally, Gwadar’s principal strategic purpose for China is to become an “exit to the ocean” (出海口)—that is, a direct route via Chinese infrastructure to secure reliable access to the strategic space and resources of the northern Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf.

- Internally, Gwadar is an extension of China’s national security and development policies. Beijing seeks to develop commercial linkages between western China, Pakistan, and Central Asia to promote economic growth and thus manage perceived risks to social stability in Xinjiang.

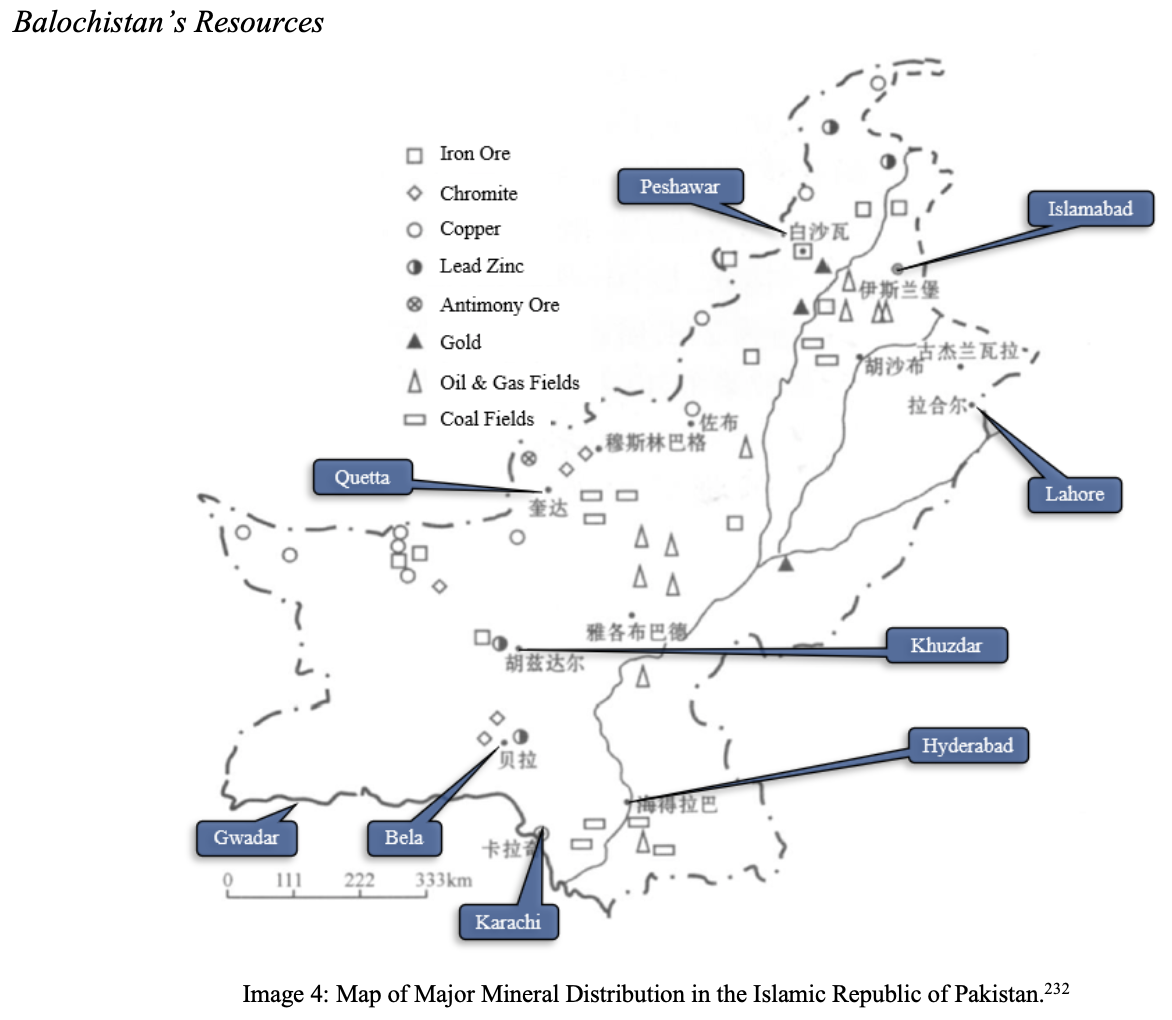

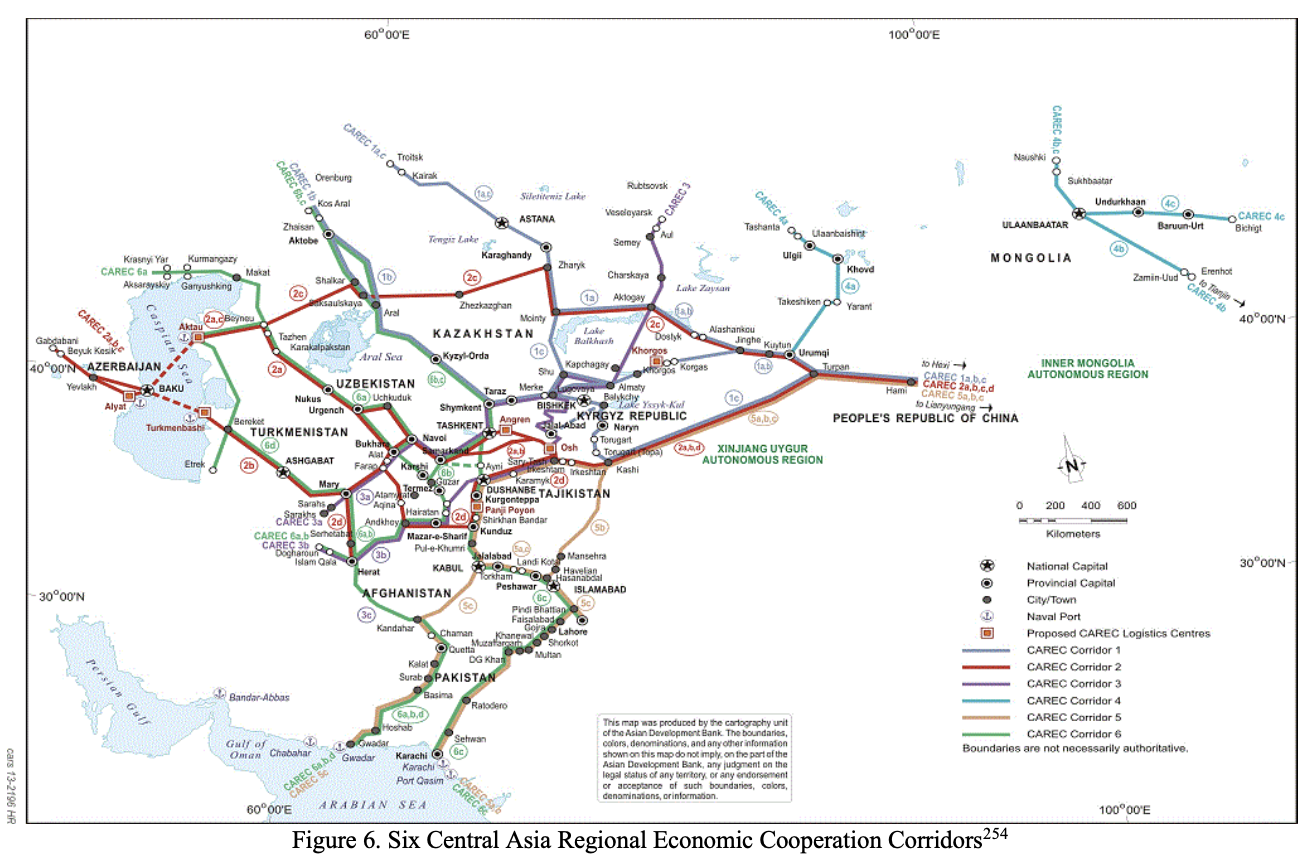

- Extensive transport infrastructure is fundamental to China’s overall plans for Pakistan. Yet while the planned transport corridor is often discussed as though it were operational, very little modern infrastructure has been built beyond a few roads and the port itself.

- The inland markets and resources of Pakistan (and Afghanistan) present some commercial prospects, but these have not yet borne fruit in part due to severe insecurity.

- Security measures may mitigate some risks to Chinese projects and personnel, but Gwadar and its hinterlands are unlikely to be secure enough to become a major commercial entrepôt.

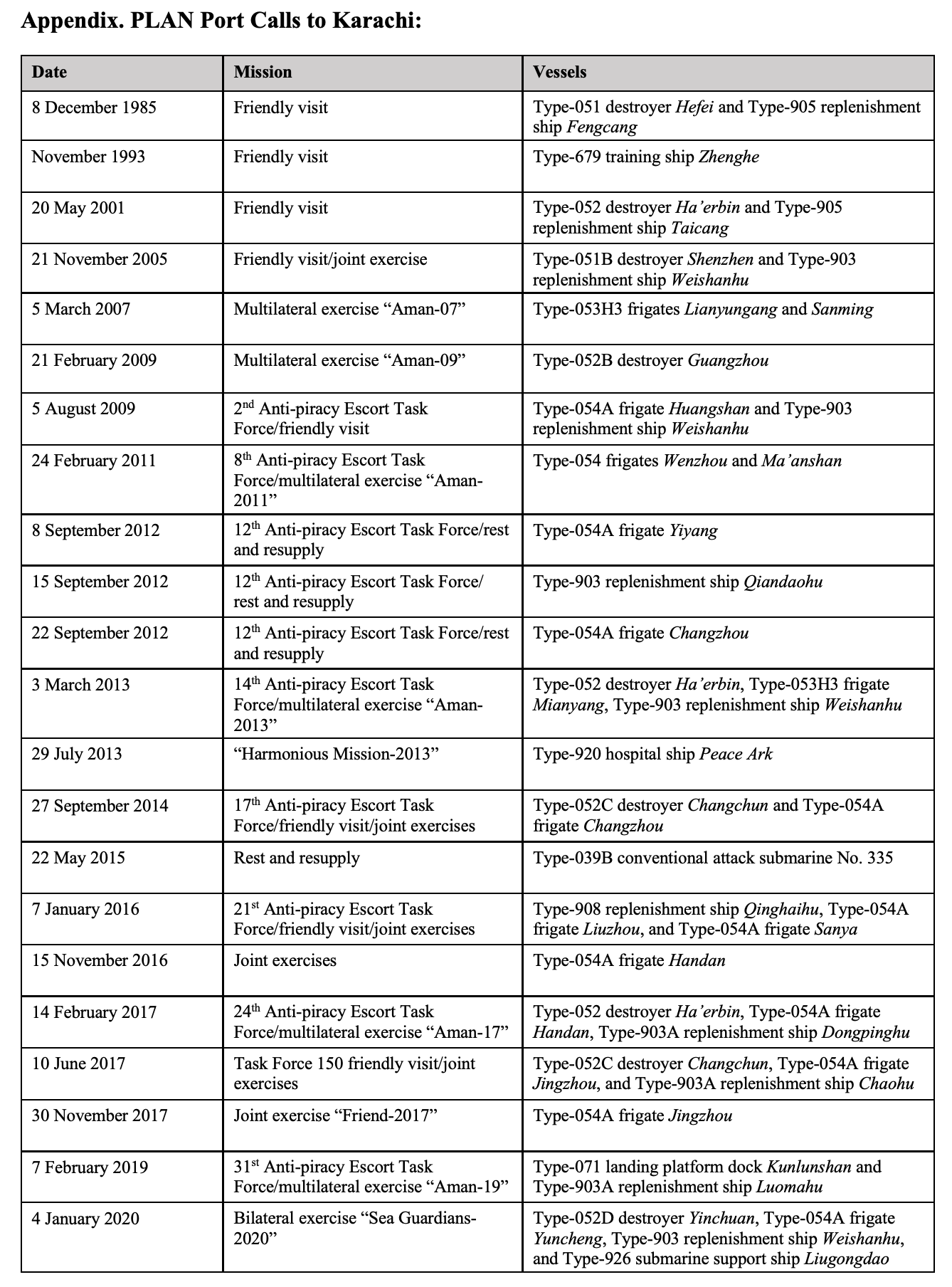

- Gwadar is not a PLA base, but it is used extensively by the Pakistan Navy (PN). The PN operates frigates and patrol vessels bought from China and will also field Chinese-made submarines. Their facilities, parts, and technicians may be readily employed for some of the PLAN fleet.

- Gwadar’s port facilities could support the PLAN’s largest vessels. Beyond the pier, Gwadar possesses a sizeable laydown yard for marshalling military equipment and materials.

- Gwadar will not necessarily have utility as a base in a wartime scenario. The most critical factor informing this view is the apparent lack of political commitment between China and Pakistan to provide mutual military support during times of crisis or conflict.

- If the infrastructure projects mature, Gwadar could become a key peacetime replenishment or transfer point for PLA equipment and personnel. Prepositioning parts, supplies, and other materials at Gwadar would be a productive use of the port and airfield facilities.

Series Overview

This China Maritime Report on Gwadar is the second in a series of case studies on China’s Indian Ocean “strategic strongpoints” (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms. Each case study analyzes a different port on the Indian Ocean, selected to capture geographic, commercial, and strategic variation. Each employs the same analytic method, drawing on Chinese official sources, scholarship, and industry reporting to present a descriptive account of the port, its transport infrastructure, the markets and resources it accesses, and its naval and military utility.

The case studies illuminate the various functions of overseas strategic strongpoint ports in China’s Indian Ocean strategy. While the ports and associated infrastructure projects vary across key characteristics, all ports share certain distinctive qualities: (1) strategic location, positioned astride major sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and/or near vital maritime chokepoints; (2) high-level coordination among Chinese party-state officials, state-owned enterprises, and private firms; (3) comprehensive commercial scope, including Chinese-led development of associated rail, road, and pipeline infrastructure and efforts to promote trade, financing, industry, resource extraction, and inland markets; and (4) potential or actual military utilization, with dual-use functions that can enable both economic and military activities.

Ports are a key enabler for China’s economic, political, and potentially military expansion across the globe. As China’s overseas economic activity grows, so too have demands on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to secure PRC citizens, investments, and supply lines abroad. Official PLA missions now include “safeguarding the security of China’s overseas interests,” but “deficiencies in overseas operations and support” persist. Yet with the notable exception of the sole overseas PLA Navy (PLAN) base at Djibouti, all of the facilities examined in this series are ostensibly commercial. Notably, the establishment of the Djibouti base followed many years of Chinese investment at the adjacent commercial port and sustained attention into resources and markets inland.

We should not assume that Djibouti is a model for other future bases. Instead, China’s strategic strongpoint model should be understood as an evolving alternative to the familiar model of formal overseas basing. With strongpoints, trade, investment, and diplomacy with the host country remain the principal functions. However, the strongpoint creates conditions of possibility for the PLAN to establish a network of supply, logistics, and intelligence hubs. We are already observing this nascent network in operation across the Indian Ocean, and this series seeks to understand its key nodes.

***

Peter A. Dutton, “Vietnam Threatens China with Litigation over the South China Sea,”Lawfare Blog, Paul Tsai China Center, Yale Law School, 27 July 2020.

Vietnam and China have sparred over competing claims in the South China Sea for nearly 50 years. Recently, Vietnamese officials have begun initiating legal proceedings against China to try and change their unfavorable position in the region.

Vietnam and China have sparred over competing claims in the South China Sea for nearly 50 years. But for the first time, in November 2019, Vietnamese officials publicly issued threats to initiate international legal proceedings against China—similar to the Philippine case that ended in 2016. Since November, there have been further indications that the Vietnamese government is quite serious, despite the limited success enjoyed by the Philippines when it invoked the law. In this post, I will address two questions on this issue: What motivates the Vietnamese government to consider this step at this time? And what can Vietnam gain?

For starters, at stake are development rights for the oil and gas reserves under Vietnam’s continental shelf. While the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea allocates resource rights in the water and under the seabed to Vietnam, out to at least 200 nautical miles from Vietnam’s shores, China stakes a “historic rights” claim to much of the same resources through its nine-dash line. This line encompasses about 80 percent of the South China Sea but has already been formally invalidated once by the arbitrators in the Philippine case. Despite its loss in court, China did not abandon its claim. Throughout 2019, Chinese government vessels harassed Vietnamese hydrocarbon survey efforts in an especially rich undersea region known as Vanguard Bank. Under the joint venture between Rosneft and Petro-Vietnam, an exploratory drilling rig began operating in the area in July 2019. China then sent its own survey vessels—under heavy coast guard escort—to demonstrate its claim. Further north, in 2011, ExxonMobil and Petro-Vietnam discovered commercially significant oil and gas deposits in Vietnam’s Block 118. The Ca Voi Xanh (Blue Whale) gas field—the area these two companies are trying to develop—lies only 50 miles off Vietnam’s coast but straddles the vast area claimed by China. A final go-ahead decision is expected sometime this year, and gaining clarity over its legal rights to resources in the region may be a key reason for Vietnam to arbitrate.

Also at stake are fishing rights in Vietnam’s 200-mile exclusive economic zone and in the waters off the disputed Paracel Islands. The Vietnamese government defies annual Chinese fishing bans that attempt to control and curb Vietnamese fishing activities in areas that overlap with China’s nine-dash line. Arbitration in this region would clarify legal rights to the resources and deflect some of the domestic pressure to protect Vietnamese fishermen. Domestic resentment is a force that must be managed carefully since, in 2014, at the height of a dispute over Chinese oil rig HYSY 981, the Vietnamese people conducted anti-China riots, assaulted Chinese in Vietnam and vandalized Chinese commercial interests.

Finally, as noted above, Vietnam disputes Chinese ownership of the Paracel Islands, a group of small but strategically important features that lie between the Vietnamese coast and China’s Hainan Island. The islands have long been claimed by Vietnam, but Chinese forces first occupied features in the Paracels in 1955 in the wake of Vietnam’s war for independence against France. In 1974 China fought a short sea battle against South Vietnamese forces to take full control over the last remaining Vietnamese positions. Since then, China has consolidated control over the islands, built up a military garrison, and harassed or arrested Vietnamese fishermen who try to continue fishing there. … … …

***

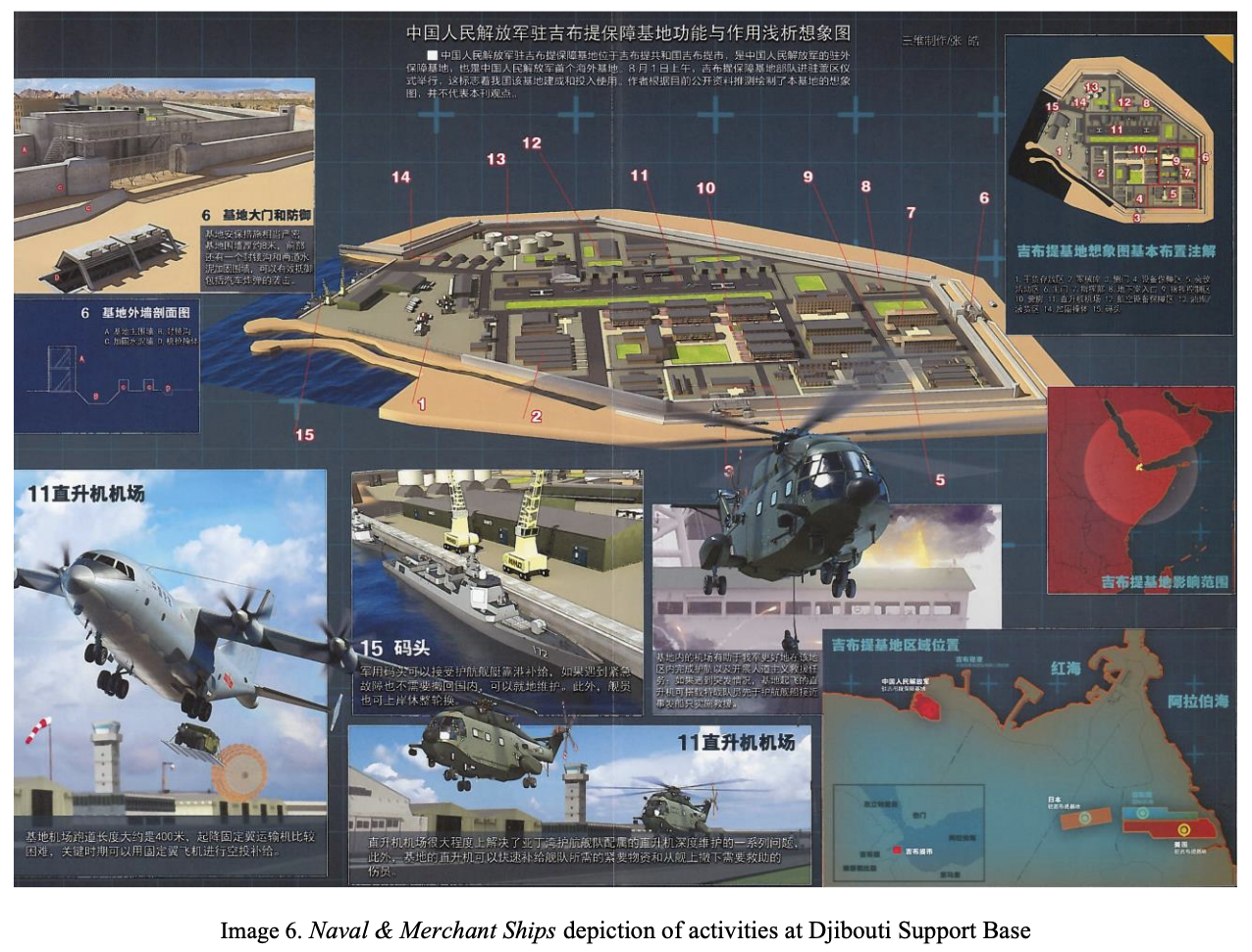

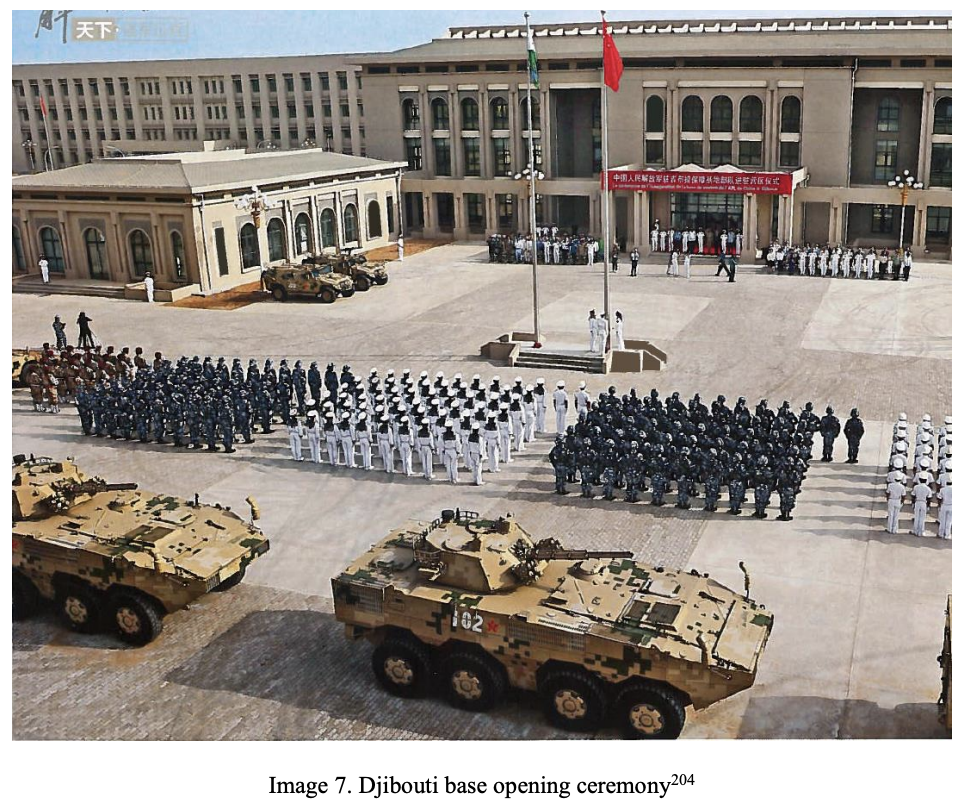

Peter A. Dutton, Isaac B. Kardon, and Conor M. Kennedy, Djibouti: China’s First Overseas Strategic Strongpoint, China Maritime Report 6 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, April 2020).

China’s first overseas strategic strongpoint at Djibouti is a secure commercial foothold on the African continent and a military platform for expanding PLA operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

This China Maritime Report on Djibouti is the first in a series of case studies on China’s “overseas strategic strongpoints” (海外战略支点). The strategic strongpoint concept has no formal definition, but is used by People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials and analysts to describe foreign ports with special strategic and economic value that host terminals and commercial zones operated by Chinese firms.

Series Introduction

This China Maritime Report on Djibouti is the first in a series of case studies on China’s “overseas strategic strongpoints” (海外战略支点). The strategic strongpoint concept has no formal definition, but is used by People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials and analysts to describe foreign ports with special strategic and economic value that host terminals and commercial zones operated by Chinese firms. Each case study examines the characteristics and functions of port projects developed and operated by Chinese companies across the Indian Ocean region. The distinctive features of these projects are: (1) their strategic locations, positioned astride major sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and clustered near vital maritime chokepoints; (2) the comprehensive nature of Chinese investments and operations, involving coordination among state-owned enterprises and private firms to construct not only the port, but rail, road, and pipeline infrastructure, and further, to promote finance, trade, industry, and resource extraction in inland markets; and (3) their fused civilian and military functions, serving as platforms for economic, military, and diplomatic interactions.

Strategic strongpoints advance a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership objective to become a “strong maritime power” (海洋强国)—which requires, inter alia, the development of a strong marine economy and the capability to protect “Chinese rights and interests” in the maritime domain. With the notable exception of the sole overseas People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base at Djibouti, all of the facilities examined in this series are ostensibly commercial. Even the Chinese presence in Djibouti has some major commercial motivations (addressed in detail in this study). However, China’s strategic strongpoint model integrates China’s various commercial and strategic interests, facilitating Chinese trade and investment with the host country while also helping the PLA establish a network of supply, logistics, and intelligence hubs across the Indian Ocean and beyond.

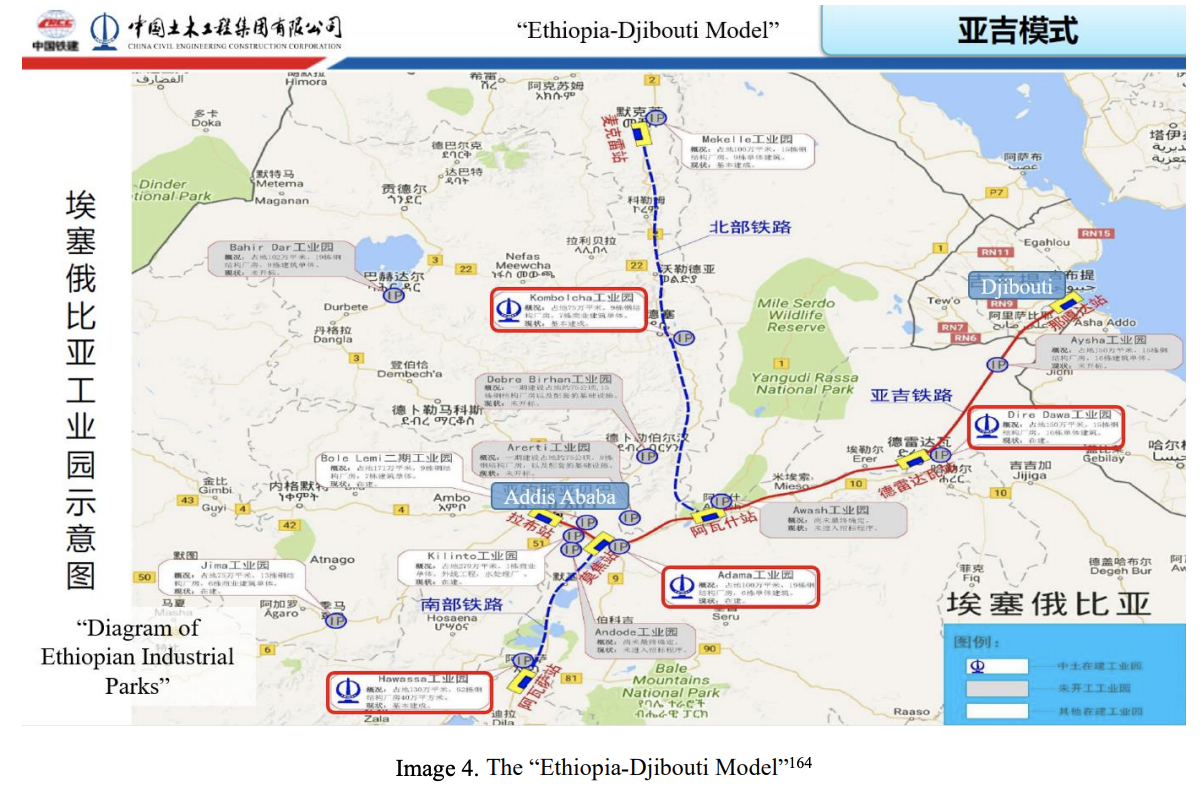

Report Summary

This report analyzes PRC economic and military interests and activities in Djibouti. The small, east African nation is the site of the PLA’s first overseas military base, but also serves as a major commercial hub for Chinese firms—especially in the transport and logistics industry. We explain the synthesis of China’s commercial and strategic goals in Djibouti through detailed examination of the development and operations of commercial ports and related infrastructure. Employing the “Shekou Model” of comprehensive port zone development, Chinese firms have flocked to Djibouti with the intention of transforming it into a gateway to the markets and resources of Africa—especially landlocked Ethiopia—and a transport hub for trade between Europe and Asia. With diplomatic and financial support from Beijing, PRC firms have established a China-friendly business ecosystem and a political environment that proved conducive to the establishment of a permanent military presence. The Gulf of Aden anti-piracy mission that justified the original PLA deployment in the region is now only one of several missions assigned to Chinese armed forces at Djibouti, a contingent that includes marines and special forces. The PLA is broadly responsible for the security of China’s “overseas interests,” for which Djibouti provides essential logistical support. China’s first overseas strategic strongpoint at Djibouti is a secure commercial foothold on the African continent and a military platform for expanding PLA operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

***

Peter A. Dutton, Testing the Boundaries: When Are International Institutional Dispute Resolution Mechanisms Effective to Resolve Maritime Disputes? A Research Report for the Maritime Dispute Resolution Project (New York, NY: U.S.-Asia Law Institute, New York University School of Law, 2019).

The following is a summary of specific issues addressed in the case study analysis and workshop discussions. The summary reflects the views and understandings of the report authors about those discussions and may not reflect the views or understandings of every workshop participant. Further, the summary presented below is not meant to represent the views of any agency of the U.S. government or of any other government.

Overall, it is clear that states from around the world, in every region, have elected to submit their territorial-maritime disputes to IIDR mechanisms. Additionally, states employ the full range of IIDR mechanisms available. These include either full or special panels of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), ad hoc arbitral tribunals, and conciliation commissions. In each case, the parties carefully selected the IIDM mechanism that was best suited for the nature of their particular dispute, and sought to tailor the scope of the IIDR forum’s jurisdiction and the standards to be applied. Their decisions reflect the careful advice of lawyers and legal advisors with special expertise in international dispute resolution and in the intricacies of international law related to maritime claims. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson and Peter A. Dutton, China’s Distant-Ocean Survey Activities: Implications for U.S. National Security, China Maritime Report 3 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2018).

Today, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is investing in marine scientific research on a massive scale. This investment supports an oceanographic research agenda that is increasingly global in scope. One key indicator of this trend is the expanding operations of China’s oceanographic research fleet. On any given day, 5-10 Chinese “scientific research vessels” (科学考查船) may be found operating beyond Chinese jurisdictional waters, in strategically-important areas of the Indo-Pacific. Overshadowed by the dramatic growth in China’s naval footprint, their presence largely goes unnoticed. Yet the activities of these ships and the scientists and engineers they embark have major implications for U.S. national security.

This report explores some of these implications. It seeks to answer basic questions about the out-of-area—or “distant-ocean” (远洋)—operations of China’s oceanographic research fleet. Who is organizing and conducting these operations? Where are they taking place? What do they entail? What are the national drivers animating investment in these activities?

It comprises five parts. Part one defines the fleet, and the organizations that own and operate it. Part two examines primary operating areas. Part three describes the range of activities conducted by Chinese research vessels while operating in distant-ocean areas. Part four sketches the key strategic China Maritime Report No. 3 2 purposes driving state investment in out-of-area oceanography. Part five discusses the implications of Chinese oceanographic research for U.S. national security.

***

Ryan Martinson and Peter Dutton, “Chinese Scientists Want to Conduct Research in U.S. Waters—Should Washington Let Them?” The National Interest, 4 November 2018.

In recent years, Chinese scientists—and the government agencies that back them—have fixed their gaze on American waters, especially those near the U.S. territory of Guam. This has raised questions about the ability of current policy to adequately protect U.S. interests.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is not the only element of Chinese sea power plying the world’s great waterways. Today, Chinese oceanographic research vessels routinely operate in strategically important areas of the Indo-Pacific region. From the deck plates of China’s large (and still growing) fleet of survey ships, Chinese scientists are pursuing their research agendas in exotic new places: Madagascar, Micronesia, Benham Rise in the Philippine Sea, the Arabian Sea and the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone in the waters south of Hawaii.

The rapid expansion of China’s out-of-area—or “distant-ocean” (远洋)—oceanographic research operations raises important questions for Indo-Pacific nations. Many places of interest to Chinese oceanographers fall within the two hundred nautical mile exclusive economic zone of other countries. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) empowers coastal states to decide whether to allow marine scientific research (MSR) in their exclusive economic zones. Should they approve Chinese MSR? If so, under what conditions? What if Chinese scientists are not doing what they say they are doing? What are the risks of ignorance?

As an Indo-Pacific country and the state with the world’s largest exclusive economic zone, the United States faces these same questions. In recent years, Chinese scientists—and the government agencies that back them—have fixed their gaze on American waters, especially those near the U.S. territory of Guam. This has raised questions about the ability of current policy to adequately protect U.S. interests.

American policy has long been to make the waters of the U.S. exclusive economic zone open and available to the activities of foreign scientists. In many cases, it does not even require a permit or advance notice to undertake MSR. While this policy is admirable for its robust endorsement of maritime freedom, this approach leaves the United States vulnerable to exploitation by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a strategic competitor with an ocean agenda markedly different from our own.

Chinese distant-ocean MSR directly serves state interests, including security interests. Many of these operations are more akin to “military surveys,” similar to work done by U.S. Navy special mission ships like the USNS Bowditch. While military surveys are not unlawful, the fact that China disguises military surveys in the garb of MSR harms U.S. interests in at least two ways. It confounds America’s ability to accurately gauge the scale and content of Chinese data collection efforts. Moreover, it undermines the U.S. interest in maritime freedom by allowing China to pursue military aims without reciprocating these freedoms to the United States and other nation-states. To counter these harmful effects, Washington should more vigorously assert its coastal state rights under UNCLOS.

***

Peter A. Dutton and Isaac B. Kardon, “Continuing to Confront China: Trump’s Approach to Maritime Security in East Asia,” GlobalAsia 12.4 (December 2017).

At the 2017 Shangri-La Dialogue, held in Singapore, U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis made clear that, despite some new elements and shifts in emphasis, there would be significant continuity in the U.S. security strategy in East Asia. As he put it: “By further strengthening our alliances, by empowering the region and by enhancing the U.S. military in support of our larger foreign policy goals, we intend to continue to promote the rules-based order that is in the best interest of the United States and all of the countries in the region.” These words could just as easily have been uttered by his predecessors in the Barack Obama administration, and indeed, those of the last several administrations. On a bipartisan basis, all shared a vocal commitment to the so-called liberal international order, underwritten by a formidable U.S. forward military presence in East Asia.

In the contested East and South China Seas, the current administration continues to anchor its policy in defense of “the rules” and the security of allies. On the key questions of sovereignty, maritime jurisdiction and U.S. access to the East Asian littoral, we see a surprising lack of major adjustments. It is, of course, possible that this is just temporary, but in the first year of the new administration, policy on maritime disputes in Asia remains roughly unchanged. Below, we analyze two major continuous aspects of the administration’s policy on maritime security in the region: the central role of allies and “rules-based” interactions. We then turn to some specifics on maritime disputes, most of which are still intact from the previous administration. Overall, the biggest changes are in emphasis rather than substance, though the tough talk about using U.S. “hard power” is now matched by an augmented defense posture that may have consequences for regional security over time. … … …

***

Jerome A. Cohen and Peter Dutton, “How India Border Stand-Off Gives China a Chance to Burnish its Global Image,” South China Morning Post, 21 July 2017.

For the past month, there has been a tense stand-off between China and India in the tri-border Himalayan region that includes Bhutan. Troubles began when China resumed building a road on the Doklam Plateau, which is disputed between Bhutan and China. India, because of its own security interests and as Bhutan’s security guarantor, stepped in to defend the position of the kingdom. China now claims India has invaded “its” territory. Tensions are high, and more than a few commentators have suggested this may be the most serious Sino-Indian border crisis since their 1962 war.

Many possibilities have been advanced for Beijing’s motive to stir up trouble. Some suggest Beijing seeks to peel Bhutan from India’s orbit. Others believe China seeks to take tactically useful high ground from which to threaten a narrow pass connecting to India’s eastern territories. Others focus on domestic Chinese political-military motivations ahead of the 19th Communist Party Congress. Another possibility is that China may be using the tension to create leverage in advance of border dispute negotiations. But why provoke India now? … … …

***

Peter A. Dutton and Ryan D. Martinson, eds., China’s Evolving Surface Fleet, Naval War College China Maritime Study 14 (July 2017).

This edited volume focuses on the development of China’s surface navy, the roles and missions of this evolving fleet, and the strategic ramifications of such development. Major themes include the capacity, organization and control, and support of China’s surface fleet; the aircraft carrier as a new element therein; and U.S. and international views concerning the overall implications. Specific chapter topics include China’s amphibious force and missile craft, the interconnection between China’s Surface Fleet Developments and its maritime strategy, the significance of China’s surface fleet in PLA doctrinal writings, the PLAN destroyer force, Chinese deck aviation, Far Seas operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond, the evolution of PLAN logistics and maintenance, and international perspectives.

***

Peter A. Dutton and Isaac B. Kardon, “Forget the FONOPs—Just Fly, Sail and Operate Wherever International Law Allows,” Lawfare Blog, Paul Tsai China Center, Yale Law School, 10 June 2017.

On May 24, the guided-missile destroyer USS Dewey (DDG 105) operated within 12 nautical miles (nm) of Mischief Reef, a disputed feature in the South China Sea (SCS) controlled by the People’s Republic of China, but also claimed by the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. The Dewey’s action evidently challenged China’s right to control maritime zones adjacent to the reef —which was declared by the South China Sea arbitration to be nothing more than a low tide elevation on the Philippine continental shelf. The operation was hailed as a long-awaited “freedom of navigation operation” (FONOP) and “a challenge to Beijing’s moves in the South China Sea,” a sign that the United States will not accept “China’s contested claims” and militarization of the Spratlys, and a statement that Washington “will not remain passive as Beijing seeks to expand its maritime reach.” Others went further and welcomed this more muscular U.S. response to China’s assertiveness around the Spratly Islands to challenge China’s “apparent claim of a territorial sea around Mischief Reef…[as well as] China’s sovereignty over the land feature” itself.

But did the Dewey actually conduct a FONOP? Probably—but maybe not. Nothing in the official description of the operation or in open source reporting explicitly states that a FONOP was in fact conducted. Despite the fanfare, the messaging continues to be muddled. And that is both unnecessary and unhelpful. … … …

***

Bonnie S. Glaser, “Breaking down the South China Sea ruling: A Conversation with Peter Dutton,” China Power Podcast, Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 2017.