Now Out in Paperback! “Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific”

Volume information: Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson, eds., Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014; paperback 15 September 2024).

- Kindle edition now available!

- China Ocean Press (www.oceanpress.com.cn) purchased the simplified Chinese language rights to publish an authorized Chinese-language edition.

Coauthor of:

- Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson, “Introduction,” 1–13.

- Andrew S. Erickson and Justin D. Mikolay, “Guam and American Security in the Pacific,” 14–35.

- Walter C. Ladwig III, Andrew S. Erickson, and Justin D. Mikolay, “Diego Garcia and American Security in the Indian Ocean,” 130–79. PART 1 PART 2

Rebalancing US Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific. Edited by Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson. Annapolis, May 2014: US Naval Institute Press. 240pp, hardcover; seven maps. ISBN: 978-1-61251-465-9. $47.95.

SUMMARY

As the U.S. military presence in the Middle East winds down, the Asia-Pacific is receiving increased attention from the American national security community. The Obama administration has announced a “rebalancing” of the U.S. military posture in the region, in reaction primarily to the startling improvement in Chinese air and naval capabilities over the last decade or so. This timely study sets out to assess the implications of this shift for the long-established U.S. military presence in Asia and the Pacific. This presence is anchored in a complex basing infrastructure that scholars–and Americans generally–too often take for granted. In remedying this state of affairs, this volume offers a detailed survey and analysis of this infrastructure, its history, the political complications it has frequently given rise to, and its recent and likely future evolution.

American seapower requires a robust constellation of bases to support global power projection. Given the rise of China and the emergence of the Asia-Pacific as the center of global economic growth and strategic contention, nowhere is American basing access more important than in this region. Yet manifold political and military challenges, stemming not least of which from rapidly-improving Chinese long-range precision strike capabilities, complicate the future of American access and security here. This book addresses what will be needed to maintain the fundamentals of U.S. seapower and force projection in the Asia-Pacific, and where the key trend lines are headed in that regard.

This book demonstrates that U.S. Asia-Pacific basing and access is increasingly vital, yet increasingly vulnerable. This important strategic component demands far more attention than the limited coverage it has received to date, and it cannot be taken for granted. More must be done to preserve capabilities and access upon which American and allied security and prosperity depend.

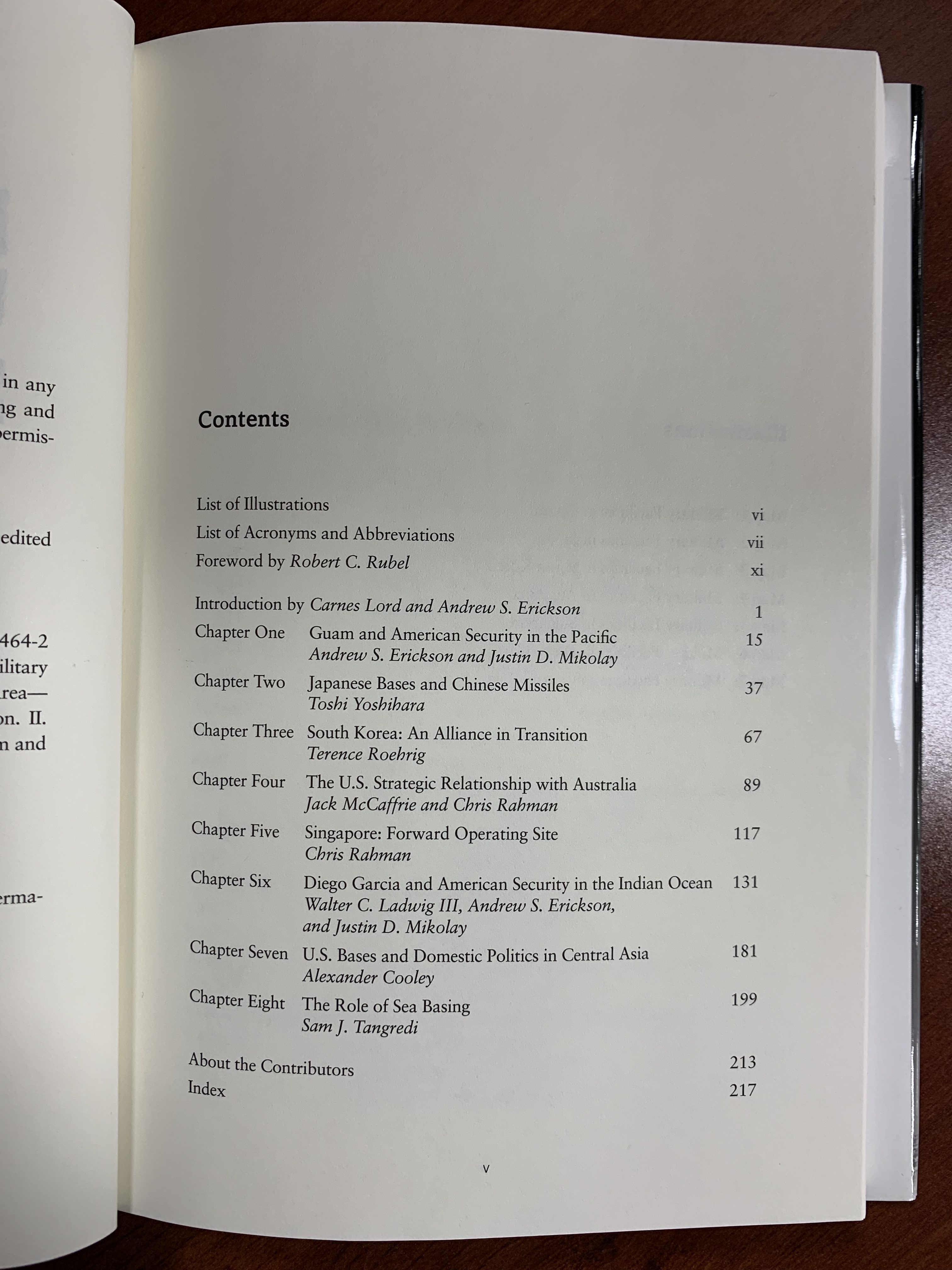

Chapters:

- “Introduction,” Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson

- “Guam and American Security in the Pacific,” Andrew S. Erickson and Justin Mikolay

- “Japanese Bases and Chinese Missiles,” Toshi Yoshihara

- “South Korea: An Alliance in Transition,” Terence Roehrig

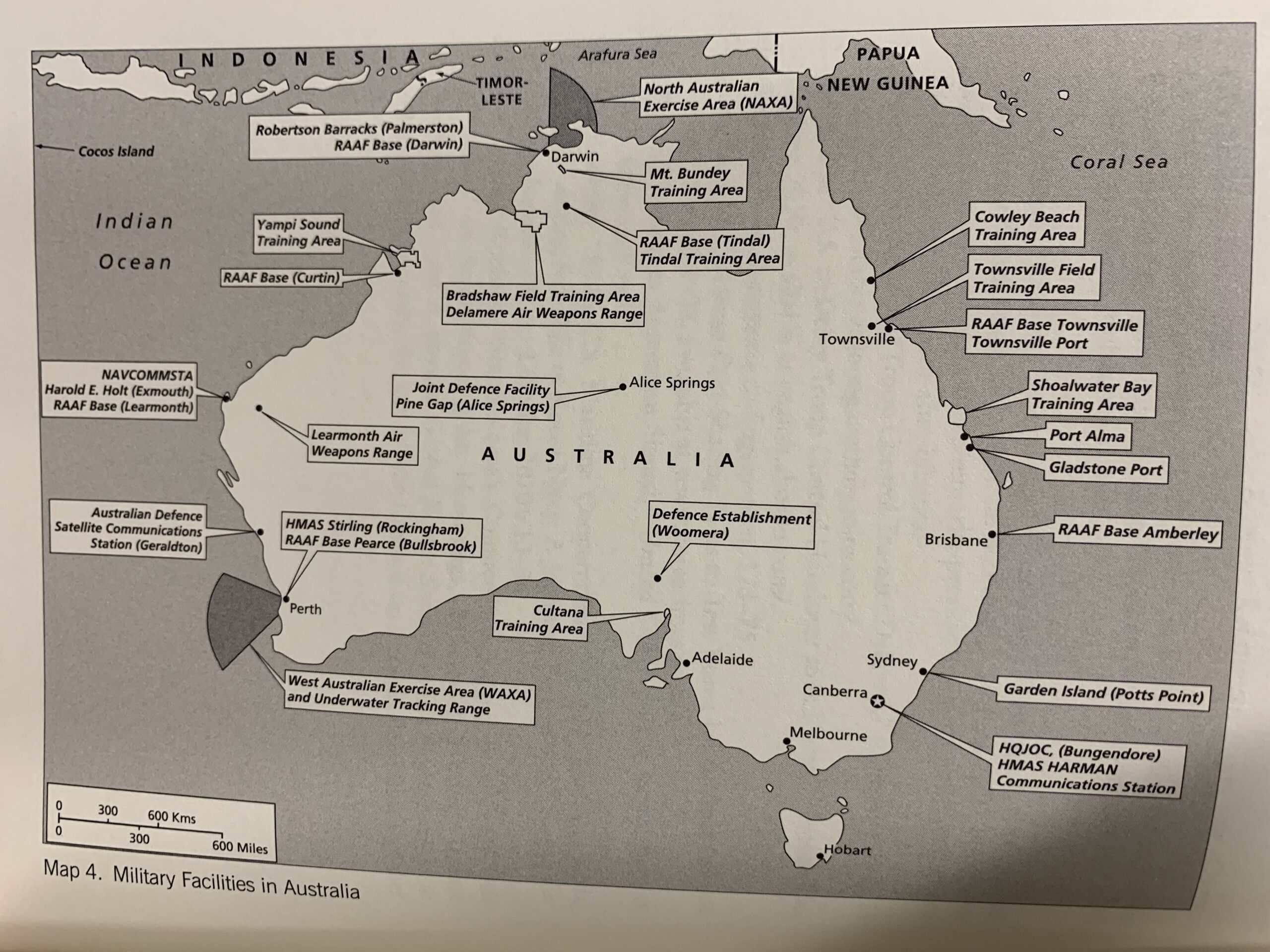

- “The U.S. Strategic Relationship with Australia,” Jack McCaffrie and Chris Rahman

- “Singapore: Forward Operating Site,” Chris Rahman

- “Diego Garcia and American Security in the Indian Ocean,” Walter C. Ladwig III, Andrew S. Erickson, and Justin D. Mikolay

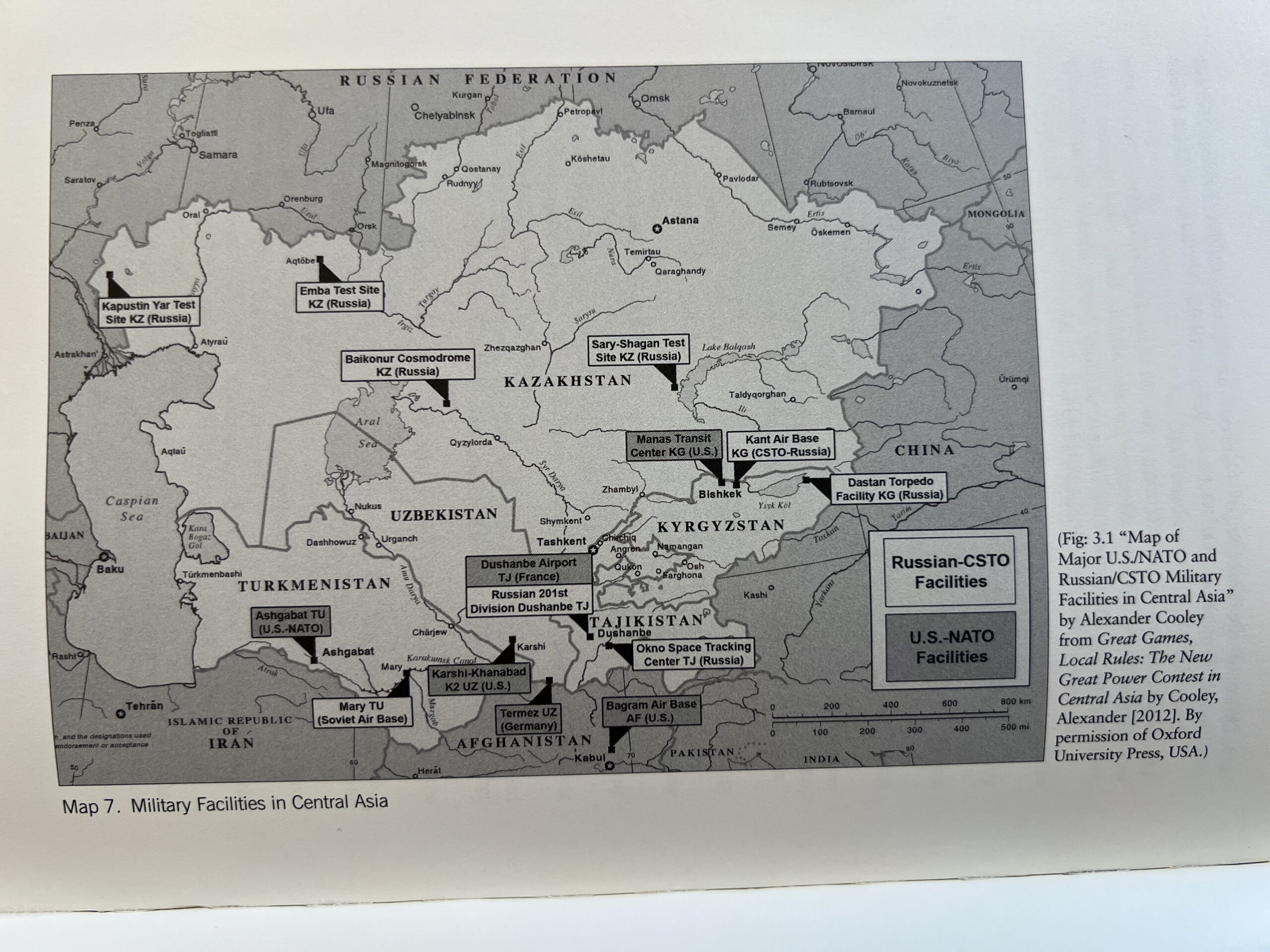

- “U.S. Bases and Domestic Politics in Central Asia,” Alexander Cooley

- “The Role of Sea Basing,” Sam J. Tangredi

DETAILS OF DIEGO GARCIA CHAPTER:

Walter C. Ladwig III, Andrew S. Erickson, and Justin D. Mikolay, “Diego Garcia and American Security in the Indian Ocean,” in Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson, eds., Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014), 130–79.

From the “Introduction,” by Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson, 7–8:

Walter C. Ladwig III, Andrew S. Erickson, and Justin D. Mikolay provide a comprehensive overview of the history, geopolitics, and strategic and operational military functions of the joint U.S.-British base on the remote island of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. The largest, and virtually only, American military footprint in the Indian Ocean at the present time (though that is changing with the hosting of U.S. military forces in northern Australia), Diego Garcia has gradually assumed considerable strategic significance for the United States, primarily as a staging base for a disparate range of capabilities such as submarine replenishment, afloat prepositioning of U.S. Army and Marine Corps equipment and munitions, long-range bomber support, and the like. The authors emphasize that while this base is too distant to directly support the projection of U.S. military power ashore throughout the region (with certain exceptions such as B-52 missions) and is too small to house combat or other forces in great numbers, it also has important advantages. Notable among them is its status as a sovereign British territory with virtually no indigenous population and none currently resident, its relative invulnerability to attack, and its presence at the seam of the two American combatant commands that have responsibility for the Indian Ocean. The authors also discuss in some detail the roles and interests of other powers in the Indian Ocean, notably India and China, and how they perceive the U.S. presence there.

Initial section of chapter, 131–32:

After more than a decade of war, the U.S. military is returning to an expeditionary force posture across the Middle East and South Asia. To project power, deter adversaries, and maintain a credible contingency response capability, the United States must sustain a robust, continuous, and enduring maritime presence throughout the region. For decades the American base on the British island of Diego Garcia has played an important role in helping the United States sustain a forward presence in the region. Yet questions remain about the military importance of Diego Garcia and how the island might be used by the American military in the future.

U.S. forces operate from a network of bases and military facilities across the Indian Ocean littoral, stretching from Northeast Africa to the Middle East, the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf, and South Asia. The United States maintains strong military-to-military relationships with several Gulf states, and these states host tens of thousands of U.S. troops at a number of land-based facilities. Such facilities do not come cheap or without liabilities, from host nation demands to popular opposition to the close proximity of Iranian missiles. Map 6 depicts Diego Garcia’s location and current facilities.

Diego Garcia helps facilitate regional military operations because of its central geographic location in the Indian Ocean littoral. The U.S. military uses Diego Garcia for long-range bomber operations, special forces staging, the replenishment of naval surface combatants and guided-missile nuclear-powered submarines (SSGN) capable of carrying out strike and special operations, and the prepositioning of Army and Marine Corps brigade sets.

Diego Garcia is the sovereign territory of a close ally and does not present the uncertainty that periodically plagues other overseas bases. Elsewhere, host nations may question long-term American commitments or demand “tacit or private goods, which risks future criticism and contractual renegotiation in the event of regime change.” Meanwhile, from a military standpoint, Diego Garcia’s isolated location introduces operational challenges but also mitigates vulnerability to terrorist or state-based attacks.

Potential conflict involving Iran drives a significant portion of future U.S. force posture planning in the region. Such a contingency requires maritime assets continuously on station in the Gulf and the northern Indian Ocean as well as the use of land-based platforms operating from Gulf states. Specific components of U.S. military planning for possible Iran scenarios are classified, but the Iranian threat dictates a mix of maritime and land-based response options far closer to the point of action than Diego Garcia.

Our analysis proceeds in four sections. The first section examines the emerging strategic importance of the Indian Ocean littoral. The second, and most extensive, section concentrates on American interests in the Indian Ocean and surveys the history and development of the American presence on Diego Garcia as part of an expeditionary, networked basing strategy in the region. A third section examines India and China’s interests and activities in the region. The final section assesses the likelihood of great-power cooperation in the region, suggests how the United States might best develop and maintain basing and access there, and underscores the need for the further development of a U.S. regional strategy.

ABOUT THE EDITORS

Carnes Lord, currently Professor of Strategic Leadership at the Naval War College and director of the Naval War College Press, is a political scientist with broad interests in international and strategic studies, national security organization and management, and political philosophy. He has taught at the University of Virginia and the Fletcher School, and served in a variety of senior positions in the U.S. government. (For further details, see https://usnwc.edu/Faculty-and-Departments/Directory/Carnes-Lord).

Andrew S. Erickson is an Associate Professor at the Naval War College and an Associate in Research at Harvard’s Fairbank Center. In spring 2013, he deployed as a Regional Security Education Program scholar aboard the USS Nimitz Carrier Strike Group. Erickson runs the research websites www.andrewerickson.com and www.chinasignpost.com.

BLURBS

“Maritime power depends on many things, Mahan taught, not least of which is an array of well-positioned, amply supplied, and strongly defended bases. The United States can no longer take for granted its ability to operate unhindered in the Asia-Pacific, which makes this volume of thoughtful essays all the more timely and important. If the shift in American power and interest to Asia is to mean anything, decision-makers will have to heed the arguments advanced here.”

— Dr. Eliot A. Cohen, Robert E. Osgood Professor of Strategic Studies, Johns Hopkins SAIS; former Counselor of the Department of State; author of Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime.

“World order in the 21st century will depend more and more upon the terms of the political and strategic relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China. In this very timely book, Lord and Erickson and their authors examine expertly the likelihood of achievement of an effective U.S. pivot to Asia. This is, and needs to be, largely a maritime shift in U.S. posture. A seismic correction in U.S. geostrategy is happening.”

— Dr. Colin S. Gray, Professor and Director, Centre for Strategic Studies, University of Reading

“The announced U.S. ‘pivot to Asia’ raised expectations and uncertainties among allies and adversaries throughout Asia and beyond. In Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific, Carnes Lord and Andrew Erickson have produced a well-considered, written and researched primer on the political-military considerations and drivers that will shape the future U.S. military posture throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Informed by the relevant historical background and host-country access issues in several key locations hosting or servicing U.S. forces, this book is a timely and invaluable resource that policymakers and analysts involved in Asian security affairs will want to keep close at hand.”

— Ambassador Lincoln P. Bloomfield, Jr., former PDASD/ISA and Assistant Secretary of State for Political Military Affairs

“Rebalancing U.S. Forces provides a detailed introduction to the complex, often contentious questions surrounding the deployment of U.S. forces in Asia and the Pacific. As the United States pursues an increasingly differentiated basing strategy across the region, a deeper understanding of the history of this issue is much needed, and this volume helps point the way.”

— Dr. Jonathan D. Pollack, Senior Fellow, China and East Asian Strategy, The Brookings Institution

“In Rebalancing U.S. Forces, Carnes Lord and Andrew Erickson have drawn together the powerful writing of the very best thinkers concerning the Pacific, US forces in the region, and the atmospheric debates about the levels, location, and employment of military force in this most nautical part of the globe. This is a book that must be on the shelf of any 21st century geopolitical analyst.”

— Admiral James G. Stavridis, USN (Ret.), Ph.D.; Dean, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University; Supreme Allied Commander at NATO, 2009–13

REVIEWS

“…potential threats all underscore the need for the U.S. to reevaluate its basing in and access to the Asia-Pacific Region. Rebalancing U.S. Forces… is an excellent place to begin. Students and strategists alike will benefit from this volume… incredibly timely… a practical and useful guide that will benefit both practitioners and students equally. …offers a history of American force posture in the Pacific, and provides excellent examples of the bureaucratic struggles, domestic politics, and the roles that individuals play in making basing decisions. …begins with an interesting examination of Guam’s role as an example to Washington on the costs and benefits of basing efforts in the Pacific. … continues by considering American basing in allied and partner countries, including Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Singapore. …final chapter…was particularly noteworthy for its careful explanation of the practical utility of sea basing in the Pacific. …where Rebalancing U.S. Forces shines is in the tremendous depth and contemporary context it provides. …Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson have found the appropriate balance between depth, breadth, and context. …an essential introduction to U.S. basing in the Pacific for defense and intelligence analysts, military planners, and strategists, and is recommended reading for students of security studies. …It is evident after reading this volume that for the United States to remain strategically relevant, to demonstrate credible commitment to its allies and offer credible deterrents to its adversaries, it must rebalance and reexamine its basing network in the Asia/Pacific. Rebalancing U.S. Forces is an excellent start to that reexamination.”

— Christopher L. Mercado; published originally in Strategy Bridge, republished in RealClearDefense, 2 October 2017.

“a useful starting point for analysts, defence officials and military planners concerned with understanding and strengthening regional security in the Asia-Pacific.”

— H.R. McMaster, Survival: Global Politics and Strategy 57.5 (October-November 2015), 232–33.

“Can the United States rely on its land bases, major naval surface combatants, and above all, its fleet of formidable nuclear-powered aircraft carriers to sustain a forward military presence in the Asia-Pacific region in the coming decades? This is the key question for Carnes Lord and Andrew Erickson, the editors of Rebalancing US Forces…. … Above all… it is China’s increasing power projection capabilities embedded in the People Liberation Army’s (PLA) growing technological developments, including long-range precision-strike assets, that is gradually redefining the regional military balance and subsequently US strategy. … The question of the long-term strategic effectiveness of America’s forward presence in the region is analyzed in detail through select case studies of Guam, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Singapore, the Indian Ocean and Central Asia. … Last but not least, the concluding chapter by Sam Tangredi examines the conceptual adaptation, experimentation, and ongoing debates concomitant to the concept of sea basing. … Taken together, Rebalancing U.S. Forces… shows the increasing complexity of issues shaping the US forward presence in Asia, as well as the need for a deeper understanding of country-specific strategic priorities, debates and choices. …the publication makes a significant contribution to both theoretical and policy-oriented literature focusing on strategic studies in the Asia-Pacific region.”

— Michael Raska, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Contemporary Southeast Asia 37.1 (2015): 146–49.

“a collection of essays relating to the Obama administration’s ‘rebalancing’ of forces to the Asia-Pacific region…. The collection—assembled by editors Carnes Lord and Andrew Erickson, faculty members at the US Naval War College—has a distinct naval flavor. That … however, does not detract from either the book’s relevance or contribution, which is substantial. … Each of the essays… is a valuable contribution to the analysis of the United States’ global strategy and the role that its bases play in the world, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. The questions they raise should be the subject of discussion and debate at the highest levels of the Department of Defense.”

— Clark Capshaw, Military Sealift Command, Air & Space Power Journal 29.4 (July-August 2015).

“In view of strict fiscal constraints, the closure of many U.S. bases overseas, America’s focus on growing threats in the Asia-Pacific area, and concerns over uncertain regional allies and neutrals, 12 strategy and national security experts offer incisive analyses of ‘the strategic realities of our era’ regarding the repositioning of U.S. forces in the Pacific and Indian Ocean littorals and in Central Asia. The essays discuss specific geographic, political, and economic considerations and challenges; future potential use for deterrence, ally support, power projection, and sea control; and military and political strengths and vulnerabilities.”

— William D. Bushnell, Military Officer (May 2015): 23.

“There’s an old joke military officials like to tell. Amateurs do strategy, professionals do logistics. For most of us self-proclaimed ‘amateurs’, how the US positions itself in the Asia-Pacific is one of the key strategic questions of our time. As Lord and Erickson’s new book Rebalancing U.S Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific admirably demonstrates, this is also fundamentally a question of logistics. This is a very timely and important book given the many questions that are being asked of the US role in the Asia-Pacific. Among allies the question focus on how the ‘pivot’ or ‘rebalance’ is being implemented, and how force presence translates into promises of force. For those concerned about US presence, the questions are whether the US is targeting them and whether its intentions are offensive or not. Finally for the US itself, there are questions about the long term capacity of America to afford and sustain an expanded presence in this remote region. Whatever your viewpoint on these questions, this book is a rich source of details and data to help guide assessment. Foremost the eight case studies demonstrate the substantial presence the US already has in the region. One-fifth of all US forces are in the Asia-Pacific, involving at least 330,000 civilian and military personnel, five aircraft carrier groups, 180 ships, 1,500 aircraft and substantial Marine and Coast Guard capacity. All this aptly demonstrates the wisdom of those who questioned how the US could pivot to a region it had never actually left. Yet for those who doubt US commitment to the Asia-Pacific, the Obama Administration’s intention to have 60% of the naval fleet in the Asia-Pacific and increased Marine presence in Australia do little to prove the US presence will endure. As several chapters clearly detail, the nature of US presence in these countries is as much about historical legacy as contemporary strategic policy. This is especially true for the base locations. As former US Defence Secretary Rumsfeld has noted of US bases in South Korea ‘our troops were virtually frozen in place from where they were when the Korean War ended in 1953’. This obvious point should help defray Chinese concerns that the US is attempting to encircle it. As Toshi Yoshihara elegantly demonstrates in the chapter on Japan, Beijing has paid significant attention to the location and presence of US bases. It also seems to have come up with a worst-case ‘solution’ of attacking via ballistic missiles. While Yoshihara identifies a number of questionable assumptions behind this approach, it does encourage serious reading of the final chapter on Sea-Basing as an alternate approach. Yoshihara’s analysis also strengthens the merits of more remote and sustainable bases for the US such as Guam, Australia and Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. Moving out to more remote bases, either outside China’s A2/AD zone or a serious effort at remote offshore balancing as advocated by Barry Posen and others, would require changes to the way the US approaches regional security and its allies. The logistics at the heart of the US presence in the Asia-Pacific, and almost uniformly endorsed by the authors in this book is that distance still matters and the shorter distance from base to crisis point the better. Continuing America’s preferred strategy of quick and decisive force will be much harder to sustain if its fleet has to move to locations five to seven days sailing time away. This is where the nut of strategy meets the screw of logistics. Close in means greater threat but a quicker response, further away is more safety yet less immediate capacity. Complications also exist in the political circumstances of the bases themselves. While Guam and Diego Garcia are under US control, there are still tensions around US bases in Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Australia. As all the chapters, but especially Alexander Cooley’s insightful chapter on Central Asia demonstrates, those who host the US are not mere passive recipients. Leaders in host countries argue between themselves and with Washington over locations, they seek political pay offs, and they ‘cheap ride’ in the provision of their own security forces. Some like South Korea have event tried to claim a veto over what the US can and can’t do with American forces based in its territory. Important questions such as the support the US receives from its allies can only be answered with a clear understanding of just how much the US does for its allies today. Inevitably an edited book like this will have stronger and weaker chapters, and for those reading about their own countries, the bar for authors to say anything new or important will be that much higher. Any Australians who is likely to pick up this book is likely to be aware of most of the details McCaffrie and Rahman outline. The Australia chapter also feels one of the driest, in terms of just listing names and places, as much as the authors try to dress it up. Still, the most significant step in the US-Australia relationship in the last few years has been a question of basing, and understanding how the Darwin deployment fits into the wider picture of US presence, and the message the US tries to send with its force posture is vital. Too many arguments around the US approach to the Asia-Pacific still treat military force as something that is entirely a question of will or desire. If nothing else, this book demonstrates how short sighted that view is. As the authors rightly argue ‘it is puzzling that serious students of American national security policy have paid so little attention to the subject of overseas basing over the years’. This is not just a question for those interested in the sharp end of conflict. As the debates over the pivot and the South China Sea have shown, presence matters. Too little presence and your commitment comes into doubt, too much and your intentions can look menacing. All the while trying to manage the tension between the message you send to opponents and allies via your presence, with the inevitable trade-off between security, capacity and speed of response. This book deserves to be on the shelf of all those who want to move beyond amateur games of risk about the Asia-Pacific and contribute to the full scope of professional analysis.”

— Andrew Carr, Australian Army Journal 12.1 (Winter 2015): 138–141.

“Very good.”

— Victor Pavlyatenko, 5-Star Review, Amazon.com, 11 February 2015.

“‘Rebalancing U.S. Forces’ gives an in-depth look at how the U.S. and Allied forces are attempting to manage a growing and modernizing China through overseas basing and the development of new weapons systems. It also gives fresh insight into how the U.S. needs to manage its relations with East and Southeast Asian nations to maintain the status quo regionally.”

— Jesse Semenza, “Very Good Book, Yet a Very Easy Read,” 4-Star Review, Amazon.com, 26 January 2015.

“Its meat and potatoes is the strategic pivot being carried out by the USA, which will see 60 percent of the US Navy’s operational effort concentrated in Asia-Pacific. The book contains eight chapters about the forward deployment of US forces in an arc from Korea to the Indian Ocean, and it also deals with the role of Australia, and the impact of domestic politics of Central Asia. … The closing essay argues for sea basing, but concludes it is an unlikely option. In their introductory essay the editors suggest the advent of precision guided ballistic missiles in the Chinese arsenal make it likely America will be unable to rely on super-carriers as the primary platforms for projecting into Asia-Pacific. With that assertion, and others, they provide substantial food for thought.”

— Peter Hore, Warships: International Fleet Review (December 2014).

“Our world continues to change very rapidly. The rise of China… led to much re-thinking among America’s defense intelligentsia. At the forefront of this, as usual, is the Naval War College which proves, yet again, that ‘military intellectual’ is not an oxymoron. If this book is any indication, the War College and its connections are still strong and useful thinkers. … This first rate collection of essays looks beyond Iraq and Afghanistan and takes a clear-eyed look at where America’s military future lies. Refreshingly thoughtful and sensible.”

— Work Boat World (October 2014): 45.

“…an excellent and timely discussion of the countries and locations presently hosting U.S. bases in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region. …informative on current U.S. presence in the region…. The maps at the beginning of the chapters provide an overview of that chapter’s particular location, giving the reader some reference point. …well-written discussion of current U.S. overseas basing… wealth of footnotes supporting the research. …a very informative anthology providing context of where the United States bases forces currently. The authors make a good case for continued and expanded basing in the region to support our friends, partners, and allies. They leave the reader to ponder tradeoffs that make this region logistically difficult. This is a book for planners, analysts, and State Department or congressional staffers concerned with the region. They should spend time reading Rebalancing U.S. Forces prior to making decisions about our future in the region.”

— Col. Steve Hagel, USAF (Ret.), Defense Analyst, Air Force Research Institute, Strategic Studies Quarterly (November 2014).

“This is an excellent book and necessary reading for anyone interested (professionally or otherwise) in security in the Asia-Pacific and or the evolving US global force posture. Individual chapters… would be recommended reading for those concerned with the respective regions. The text is written to academic standards and each chapter includes detailed endnotes: a most valuable resource for further research, in particular with regard to the Chinese sources cited. The standard of presentation and quality of editing is high. The intended audience for this book would principally be those in the academic, think tank and policy analysis communities, and… is essential reading: however, the text is also accessible to those reading for pleasure. All in all, this is an engaging book and one that is highly recommended.”

— James Bosbotinis, The Naval Review (November 2014).

“This excellently edited volume of essays, most contributed by Naval War College faculty, is devoted to the ongoing rebalancing of U.S. forces (the Obama administration’s much-heralded ‘pivot’) and their concomitant basing structure from Europe and the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific. … One derives a certain sense of déjà vu—that “heartland” and “rimland” have returned with a vengeance, evoking the memories of Halford Mackinder and Alfred T. Mahan, respectively. … This work involves a chapter-by-chapter analysis of the past, present, and projected future of U.S. basing and forward presence, running roughly east to west, from Guam to the former-Soviet Central Asia (Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan). The analyses are dense and detailed. As with all … chapters, a good map displays the base locations.”

— Robert E. Harkavy, “Basing and the Pivot,” Review Essay, Naval War College Review 67.4 (Autumn 2014): 147–50.

“For those readers who have an interest in reading the plans of the U.S. Navy in addressing… operations in the Asia-Pacific region, as well as a case for efforts towards sea basing, this is a book that contains a detailed and nuanced analysis. Readers… will find a wealth of information about American capabilities in the Pacific and Indian Ocean basins….. At a slim 216 pages of written material (followed by an index), this book includes eight essays on a bevy of concerns for the Navy in the Asia-Pacific region, written by a variety of contributors from both academia as well as high-ranking officers from the United States, Great Britain, and Australia. … As a thoughtful and persuasive work, it deserves attention by military as well as civilian audiences.”

— Nathan Albright, Naval Historical Foundation, 5 September 2014.

“With this well-crafted edited volume, Lord and Erickson have put together an excellent team to provide us with a valuable and much needed discussion of the current U.S. basing arrangements in the Asia-Pacific. …a truly excellent book… the quality and strength of each individual chapter is a reflection of the depth of knowledge of the authors assembled for the task. Its level of detail (including seven excellent maps) will also make it a useful reference text… in the end it’s a testimony to the book’s quality that its biggest problem is that you are left wanting more.”

— Patrick Cullen, U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 140 (September 2014): 74.

“The Naval Institute Press has published [an] excellent new [book] on the Pacific region’s past, present, and future …Lord and Erickson, faculty members at the Naval War College, present a very insightful and wide-ranging set of essays by some of the best minds on the Pacific.Given the rise of China and the emergence of theAsia-Pacific region as the center of global economic growth and strategic contention, nowhere is American presence and basing more important. That said, the manifold political and military challenges, to include rapidly improving Chinese long-range precision-strike capabilities, complicate the future of American access.”

— VADM Peter H. Daly, USN (Ret.), “CEO Notes,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 140.6 (June 2014): 6.

“this is an extremely informative and interesting edited volume. … Most of the chapters are organized about particular territories: Guam, Japan, S. Korea, Australia, Diego Garcia, Singapore and Central Asia. (There is also a chapter about sea basing.) While some contributions emphasize the history of the relationship with the US, e.g., the Australia and S. Korea chapters, others are intensely focused on strategic considerations. For me, these were the standouts, particularly the chapters about Guam, Diego Garcia and Japan. … a strong recommend for anyone interested in a better understanding of the geopolitical situation in East Asia and the Indian Ocean.”

— A. J. Sutter, “Not-to-Miss Background for Understanding East Asian Geopolitics,” 5-Star Rating, Amazon.com, 1 June 2014.

“Lord and Erickson’s essay collection will be a must-read for the entire Asian security establishment. … fascinating details, for example about nuclear submarine reactor cores, warship steaming ranges and speeds, Australia’s targeting role during during Desert Storm, the tempo of US personnel and materiel transiting Singapore every year (150 US ships, 400 aircraft and 30,000 personnel) and even the plumbing of Diego Garcia (not trivial given its average elevation of 4 feet above sea level). … There is even a chapter at the end on ‘sea basing’, an operational concept using floating mobile platforms for storage, repair and deployment. … Nothing, as Lord and Erickson imply, shouts commitment louder than bases.”

— Julian Snelder, “Bases, Places and Boots on the Ground: A Review of ‘Rebalancing US Forces’,” The Lowy Interpreter, 14 May 2014.

“the arrival… could hardly be more timely. … More than merely a history of America’s basing archipelago in the Asia-Pacific theater, Rebalancing U.S. Forces is a critical examination of the assumptions underlying U.S. basing, and therefore U.S. strategy, for the region. … Editors Carnes Lord and Andrew Erickson, both professors at the U.S. Naval War College, are uniquely suited for this project. In addition to his academic accomplishments, Carnes Lord has long service inside the White House and the National Security Council staff. Andrew Erickson’s intimate knowledge of China and its military forces and doctrine has made him a veritable one-man national asset. Lord and Erickson, in turn, have recruited an eminent roster of contributors to this anthology who provide a survey of the history, practicalities and future of the U.S. base structure in the Asia-Pacific region. … Unlike many anthologies, the contributions to Rebalancing U.S. Forces are uniformly excellent. Each chapter essay is thoroughly researched and sourced, and is written by experts well familiar with the history, dilemmas, and future challenges of each location. Seven first-rate maps of U.S. facilities spanning the region further enhance the book. … Policy makers … should read Rebalancing U.S. Forces to obtain a deeper understanding of the challenges America and its partners face.”

— Robert Haddick, “America’s Military Bases in the Asia-Pacific: Strategic Asset or Vulnerability?” The National Interest, 18 May 2014.

“…leading US naval thinkers Carnes Lord, professor of strategic leadership at the US Naval War College, and Andrew S. Erickson, an associate professor at the college, were clearly key thinkers in bringing together the new US Naval Institute book, Rebalancing US Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific…. The book is a collected work of the faculty of the US Naval War College and its external contributors, but it draws very much on the College’s roots and association with the great maritime strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, who so clearly saw, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the need for US basing options in the Pacific. … What is significant about this study is the fact that, for the first time in decades, the US has been thinking from a clean-sheet perspective about its basing needs. … The US ‘re-balancing’ toward Asia and the Pacific has begun to raise major planning issues for the US, and that is what this important new book addresses. … in an outstandingly well researched chapter entitled ‘Diego Garcia and American Security in the Indian Ocean’ … Walter C. Ladwig III, Andrew S. Erickson, and Justin D. Mikolay … chronicle India’s and the PRC’s interests and concerns in the Indian Ocean. Chapters such as this, in the book, make it a vital resource. …”

— Defense & Foreign Affairs Special Analysis 32.18 (25 February 2014): 1–2.

FURTHER INFORMATION

For a two-article summary of the volume, see:

Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson, “Bases for America’s Asia-Pacific Rebalance (Part 1 of 2),” The Diplomat, 2 May 2014.

Part one of a two-part series evaluating the evolving network of US bases in the Asia-Pacific.

The first part of a two-part series that evaluates the United States’ evolving network of bases in the Asia-Pacific and the opportunities and challenges each brings to the table moving forward.

The Asia-Pacific region, central to global economic and geopolitical development in the twenty-first century, is the logical focus of the Obama Administration’s ongoing rebalancing of capabilities, relations, and presence thereto. This effort is inspired by profound challenges and opportunities emerging in the region. Aspects of China’s rapid, broad-based development fall into both categories, with challenges including increasingly potent anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems that threaten the viability of potential opponents’ forces with long-range precision strike capabilities. Central to American presence and influence in the vital Asia-Pacific, but facing increasing vulnerabilities, is a complex network of bases and access points that has been too long neglected by both scholars and the American public. This two-part series addresses these timely and important issues, surveys present U.S. basing infrastructure, and examines key challenges and trends that Washington confronts as attempts to preserve its capabilities and influence in the Asia-Pacific.

In an address to the Australian Parliament on November 17, 2011, President Barack Obama announced that the United States, as part of a general upgrade of its security cooperation with Australia, would deploy up to 2,500 U.S. Marines at Darwin in northern Australia. Although the United States has long enjoyed a close military (and intelligence) relationship with Australia, not since World War II has any significant American military force been stationed permanently on the continent. This move, the president explained, reflected “a deliberate and strategic decision—as a Pacific nation, the United States will play a larger and long-term role in shaping this region and its future.” Together with former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s late 2011 visit to Myanmar (Burma), the first by an American secretary of State in more than half a century, this is the most striking manifestation of a new determination on the part of the Obama administration to reassert the United States’ traditional interests in the Asia-Pacific region, to reassure its friends and allies there of the long-term nature of its commitment to them, and to send an unmistakable signal to the People’s Republic of China that the United States is and intends to remain a “Pacific power” fully prepared to meet the challenge of China’s rise and its regional ambitions. …

It is thus critical to examine the countries and territories hosting American bases in one particular region of increasing strategic salience today: the Asia-Pacific. Changes to the U.S. force structure are occurring in a shifting geopolitical environment in which the rise of new powers in Asia, particularly China and India, is creating uncertainty over the future security architecture of the Asia-Pacific region. It has been argued by realist scholars such as John Mearsheimer that America’s dominant position in Northeast Asia (which, along with Western Europe, is considered to be one of the world’s critical regions) facilitates U.S. global hegemony.

Washington needs to rethink fundamentally the American forward presence in Asia in light of the rapid growth in very recent years in the “antiaccess/area denial” (A2/AD) capabilities of the armed forces of the People’s Republic of China. This is largely a story of the evolution of existing locations: despite increasing challenges to American interests in East Asia, the prospects for additional U.S. foreign basing and access rights are declining throughout the region. In response to domestic political pressures in their host nations, facilities and forces in Japan and South Korea are already being consolidated and reduced. Despite efforts to focus on “places, not bases,” Washington seems unlikely to acquire further major footholds in East Asia. A survey of these locations (which will be offered in the second part of this two-part series) suggests many challenges and opportunities for Washington.

Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson, “Bases for America’s Asia-Pacific Rebalance (Part 2 of 2),” The Diplomat, 6 May 2014.

Part two of a two part series evaluating the evolving network of US bases in the Asia-Pacific.

The second part of a two-part series that evaluates the United States’ evolving network of bases in the Asia-Pacific and which opportunities and challenges each brings to the table moving forward. Read part one here.

Moving toward Asia from the West Coast, one immediately encounters the reality of America’s status as an Asia-Pacific power: it possesses a sweeping array of sovereign territory in which to base Pacific-focused forces. Hawaii and Alaska first come into view. Although they are integral parts of the United States, their geographical proximity to Asia gives them unique importance in any discussion of military bases on American soil. Already home to a significant military presence, both are likely candidates for an enhanced military presence in the coming years as part of the Obama administration’s strategic reorientation toward Asia: Hawaii, thanks to its central location, and Alaska thanks to its nearly unparalleled strategic depth.

Hawaii constitutes the backbone of U.S. military presence and power projection capabilities in Asia. Home to the headquarters of U.S. Pacific Command, the largest of the Unified Commands, Hawaii hosts 161 military installations that facilitate all aspects of U.S. military activities, from land, air and space operations, to training, to communications. It has been estimated that military-connected personnel account for 17 percent of Hawaii’s population. As a strategically important forward location in the Pacific, Hawaii has seen a buildup in Army and Marine forces since the 9/11 terrorist attacks. At the same time, the U.S. Navy has increased its visibility in the Western- Pacific in an effort to dissuade and deter potential regional threats from traditional and trans-national actors.

Alaska hosts America’s nascent missile defense umbrella in the Asia-Pacific, one of two locations for the deployment of America’s first-generation ground-based ballistic missile defense system. Globally, the proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) is a major concern for policy makers and military planners; the spread of nuclear weapons within the Asia-Pacific region is perhaps the most serious issue in contemporary security policy. The threat to the U.S. posed by ballistic missiles looms largest in the Asia-Pacific region. North Korea’s nuclear ambitions coupled with the continued development of long-range ballistic missiles already threaten America’s regional allies such as Japan, and in time could pose a similar hazard to portions of the U.S. homeland. Developments in China’s nuclear forces and even adjacent countries such as Pakistan raise similar concerns. Concentrated around the Air Force bases at Eielson and Ft. Greely, the mid-course ground based interceptors are the first line of defense against ballistic missile attacks. Alaska’s significance to Asia-Pacific security goes beyond ballistic missile defense. It is also home to three Air Force bases, three Army bases, and five Coast Guard stations. Its 24,016 personnel include 13,406 from the Air Force. As defense in depth and homeland security become increasingly important to U.S. national security, Alaska will have an increasingly important role to play.

The U.S. also retains other sovereign or associated territories scattered across the Pacific that currently serve some military functions (notably, the missile-testing facility at Kwajalein), or could serve such functions in the future – as of course many of them did during World War II. It is not difficult to envision the U.S. reactivating a network of austere sites for contingency use at places like Midway or Wake Island that could provide the nation greater strategic depth in the Western and Central Pacific than it enjoys today. … … …