The Ryan Martinson Bookshelf: Must-Read Revelations re China’s Maritime Policies, Sea Forces & Oceanic Operations

For analysis of Chinese maritime policy and China Coast Guard development, it simply doesn’t get any better than this. Enjoy this fully updated one-stop library of my colleague Ryan Martinson’s work. It’s well worth reading all of these superb publications and interviews, even as they exceed three dozen in number!

Andrew S. Erickson, “The Ryan Martinson Bookshelf: Must-Read Revelations re China’s Maritime Policies, Sea Forces & Oceanic Operations,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 9 November 2020.

Ryan D. Martinson is an Assistant Professor in the China Maritime Studies Institute of the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. The views represented in these articles are his alone, and do not reflect the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

PUBLICATIONS

Ryan D. Martinson, “Deciphering China’s ‘World Class’ Naval Ambitions,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (August 2020).

The Chinese Navy already routinely operates out of area, so its global aspirations should come as no surprise.

The scale and speed of China’s naval construction bear only one conclusion: Beijing is seeking to erode U.S. naval supremacy. This judgment requires no specialized knowledge of China or access to top secret intelligence. One need only look at the platforms the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is building and the pace at which it is building them.

But to fully understand the nature of the China maritime challenge, one must dig deeper—into the ideas guiding China’s naval development. This is far more difficult. The Chinese military is extremely cautious about revealing its true intentions. It produces lots of media content, but most of it is fluff. Analysts who spend their days sifting through Chinese sources failed to anticipate Beijing’s decision to build three enormous military facilities in the heart of the South China Sea. One day, China just began dredging sand and coral.

Still, many important things cannot be hidden. The service cannot build and shape a fighting force in secret. Major priorities must be communicated and inculcated. Soldiers, sailors, airmen, and rocketeers need to know what is asked of them and why it matters. By necessity, much of this happens in the open. The PLA can conceal plans to build bases; it cannot obscure broader aspirations.

The PLAN’s newest aspiration is to transform itself into a “world-class navy.” The idea of becoming “world class” was not a PLAN invention. Sometime in 2016, China’s head of state Xi Jinping told the PLA to transform itself into a world-class military. This injunction later appeared in Xi’s report at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, making it the official policy of the Chinese party-state.

The concept means different things for different services. For the PLAN, the clearest articulation appears in a speech delivered by PLAN Commander Vice Admiral Shen Jinlong shortly after the 19th Party Congress.1 The concept has what Admiral Shen calls three “essential features.” Two refer to key attributes of a world-class navy—global reach and command of the sea; the third highlights the process of getting there. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Counter-Intervention in Chinese Naval Strategy,” Journal of Strategic Studies, published online 27 March 2020.

The prospect of U.S. military involvement in a regional war looms large in Chinese naval strategy. This article examines the Chinese Navy’s evolving role in countering U.S. military intervention in a conflict over Chinese-claimed offshore islands. This role has both wartime and peacetime aspects. In peacetime, the PLA Navy serves a deterrence function, demonstrating China’s ability and resolve to fight the U.S. military if the U.S. were to intervene. In wartime, the operations of the PLA Navy would sit at the heart of any maritime campaign, helping to achieve China’s territorial objectives in spite of U.S. involvement.

Keywords: Naval strategy; Chinese navy; territorial disputes; counter-intervention; maritime strategy; U.S.-China relations

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “The Role of the Arctic in Chinese Naval Strategy,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief 19.22 (20 December 2019).

Introduction

In her recent China Brief article, Dr. Anne-Marie Brady examined the prospect of China deploying military power to the Arctic (China Brief, December 10). Applying the methods she used in her pathbreaking 2017 book, Brady draws from authoritative Chinese sources to demonstrate the growing importance of the Arctic in China’s strategic calculus. [1] She also cites a host of other indications that Beijing intends to send naval forces—especially submarines—north through the Bering Strait. Her research provides important context for an oracular 2019 U.S. Department of Defense claim that China could be laying the foundation for naval operations in the Arctic (Department of Defense, May 2).

Building on the excellent work done by Brady and others, this article argues that the available evidence allows for more categorical conclusions about China’s Arctic intentions. Specifically, the Chinese Navy has formally decided to incorporate Arctic ambitions into its naval strategy, and Chinese scientists and engineers are already conducting research to help it realize these ambitions.

From the Near Seas to the Two Poles

In China, “naval strategy” (海军战略, haijun zhanlüe) serves two key purposes. It defines the principles guiding how the fleet will be used today, and it outlines the plans for building the capabilities needed to meet the requirements of tomorrow. [2] China’s first official naval strategy dates to the mid-1980s, when the service’s chief preoccupation was restoration of Chinese-claimed islands (including Taiwan). Called “near seas defense” (近海防御, jinhai fangyu), it instructed the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to prepare to seize and maintain command of the sea in waters within the first island chain, a capability the PLAN already possessed vis-à-vis its weakest neighbors. It also catalogued the equipment and training needed to enable the service to achieve these wartime aims in scenarios involving more capable navies. [3]

By 2015, China’s naval strategy had officially changed to “near seas defense, far seas protection” (近海防御, 远海防卫/护卫 / jinhai fangyu, yuanhai fangwei/huwei). [4] The new strategy reflected trends that had been evident for years. The PLAN’s maritime defense mission remained preeminent. But the service was also increasingly tasked with operating in waters beyond East Asia, in the “far seas.” This began with an epochal 2008 decision to send successive task forces to counter Somali piracy in the Gulf of Aden, but soon extended to a whole range of other functions, often lumped under the rubric of “protecting overseas interests.”

The Arctic did not figure in either of these strategies. But we now know that it will in the next strategy. This fact was omitted from China’s 2018 White Paper on Arctic Policy (State Council Information Office, January 26, 2018) and its 2019 National Defense White Paper (State Council Information Office, July 24) —authoritative documents largely meant for foreign consumption. However, the political commissar of Dalian Naval Academy, Senior Captain Yu Wenbing (喻文兵), revealed the name of the next strategy in a July 2018 essay. Published in the PLAN’s official newspaper, Yu’s essay discussed his institute’s role in training and educating the leaders of the future navy. To provide context for his advocacy, he pointed out that the PLAN’s strategy was transitioning to a new concept: “near seas defense, far seas protection, oceanic presence, and expansion into the two poles” (近海防御, 远海防卫, 大洋存在, 两极拓展, jinhai fangyu, yuanhai fangwei, dayang cunzai, liangji tuozhan ). [5]

Senior Captain Yu did not indicate when this transition would be complete—but a more recent source does. In mid-2019, Ni Hua (倪华), a PLAN engineer posted to the Military Representative Office in Yichang City (Hubei Province) published an article about the need to boost China’s ability to counter the threats posed by foreign sea mines. Ni began by discussing the strategic concerns shaping China’s mine warfare needs. After citing the growing importance of the maritime domain to Chinese national security, he stated that “by 2030 the navy will…promote the construction and development of equipment according to the strategic requirements of ‘near seas defense, far seas protection, presence in the two oceans, expansion into the two poles.’” [6]

Most recently, the new strategic concept was broached during a presentation by Deng Aimin (邓爱民), Director of the Ship Development and Design Center of the 701 Research Institute, part of the state-owned China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation (CSIC). At an October 2019 event in Shenzhen, Deng spoke on the topic of China’s planned nuclear-powered icebreaker, which his team was designing. He offered some brief remarks on the strategic drivers behind his work: “Everyone should be fairly clear about our national strategy. One aspect is the strategic position of the poles. Another is expansion into the two poles…” [7]

Clearly, then, the PLA has decided that the next naval strategy will bring the service to the Arctic. Perhaps as a result of this decision, the PLA strategic studies community has grown increasingly candid about discussing the military’s future role in this new arena. For example, in a 2017 article, three analysts from the PLAN Submarine Academy examined the increasing out-of-area requirements of China’s submarine force. They argued, “China’s submarine forces must not only operate in the Pacific Ocean; they must also operate in the Indian Ocean. In the future, they must even operate in the Atlantic Ocean and the Arctic Ocean.” [8]

A more thorough treatment of this subject was published by PLAN Captain Zuo Pengfei (左鹏飞), a lecturer at China’s National Defense University. In his 2018 volume entitled A Study of Polar Strategy, Captain Zuo forthrightly discusses the military value of the Arctic to China and calls for deploying Chinese naval forces to the region. He writes, “As the world becomes hotter, the Arctic passages will increasingly become important areas for the operations of China’s maritime forces. Once [Chinese] forces normalize their presence in this region, they will not only be able to effectively pin down great powers like the U.S. and Russia; they will greatly reduce pressure from primary opponents in our other strategic directions.” [9]

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “China as an Atlantic Naval Power,” RUSI Journal 164.7 (18 December 2019).

China has shown an interest in extending its reach to the Atlantic Ocean.

China is in the process of becoming an Atlantic naval power, Ryan D. Martinson argues. Since 2014, the activities of the Chinese navy in the South Atlantic have evolved from port visits and largely symbolic joint exercises to independent operations at sea. This helps the Chinese navy to gain familiarity with the operating environment, so that it can effectively respond when called on by civilian leaders to protect China’s growing interests in the region. China’s increased naval presence in the South Atlantic may also reflect a shift in Beijing’s strategy for countering perceived threats from the U.S. military in the Western Pacific.

In recent years, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has dramatically expanded the geographic scope of its maritime operations. It has moved east, into the Western and Central Pacific. In 2007, the PLAN regularised training activities beyond the ‘first island chain’, the archipelagic barrier separating the China Seas from the wider Pacific.1 Today, Chinese warships routinely transit the Miyako Strait and Bashi Channel to conduct blue-water combat training in the Philippine Sea.2

The PLAN is also moving west, into the Indian Ocean. In December 2008, the PLAN’s first anti- piracy escort task force departed China for a four- month deployment to the Gulf of Aden. Since then, China has maintained a continuous naval presence in the northwest Indian Ocean. The original anti-piracy mission has evolved to include a broad set of non-combat roles, from friendly port visits to evacuating Chinese citizens from war-torn countries.

In little over a decade, the PLAN has transformed itself from a regional navy to a force with major presence out of area. This transformation is incomplete: there are strong indications that China intends to further bolster its sea power in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. But Beijing is also looking beyond the Indo-Pacific to other parts of the world where Chinese interests are concentrated.

This article examines the next frontier in Chinese naval expansion. It argues that, while the Northern Indian Ocean, and Western and Central Pacific Ocean will remain the primary geographic focus of Chinese sea power development, Beijing is preparing for future operations in the South Atlantic.

First, the article outlines the known facts of PLAN operations in the South Atlantic, including port visits, training and exercises, and other activities. It shows how PLAN activities have evolved since the service first arrived in the South Atlantic in 2014. It also highlights the role of Cape Town as a friendly port that Chinese naval forces rely on for shore- based support while operating in the South Atlantic. Second, it discusses the main drivers behind Beijing’s interest in the South Atlantic. It examines the growth in tangible Chinese interests, on shore and at sea, and explores the possibility that Beijing’s focus on the South Atlantic is intended, at least in part, to relieve US military pressure along China’s maritime periphery. … … …

***

Jessica Chen Weiss, “What China’s Assertiveness in the South China Sea Means—And What Comes Next,” The Monkey Cage, Washington Post, 30 May 2019.

China’s ‘maritime gray zone operations’ target U.S. naval vessels.

On Wednesday, General Joseph F. Dunford Jr., chairman of the Pentagon’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, remarked that despite assurances that there would be no moves to militarize the South China Sea, China had built “10,000-foot runways, ammunition storage facilities” — and routinely deployed aviation and missile defense capabilities. U.S. naval vessels operating in East Asia report being shadowed and harassed by China’s maritime forces. The Royal Australian Navy flagship Canberra also reported a recent encounter in the South China Sea while trailed by a Chinese warship: Its helicopter pilots were hit with lasers from what appeared to be fishing vessels.

To put these and other recent events in context, I reached out to two experts: Andrew S. Erickson, a professor at the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) and a visiting scholar at Harvard University’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, and Ryan D. Martinson, a researcher at CMSI. They are the editors of the book “China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations” (U.S. Naval Institute, 2019). What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation:

Jessica Chen Weiss: The trade war has dominated headlines in U.S.-China relations, but what’s the state of play between the United States and China in the South China Sea? How has China’s artificial enlargement of islands and reefs affected U.S. operations and interests?

Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson: While tariff disputes dominate world news, territorial disputes in the South China Sea remain a key flash point in U.S.-China relations. Beijing maintains a claim to all of the space within a “dashed line” enclosing most of the South China Sea — including hundreds of tiny islands and reefs. China also believes it has the right to engage in military, scientific and economic activity anywhere within this zone, and to limit at least some these same activities by other countries. Over the last decade or so, Beijing has vigorously asserted these claims. Instead of using its navy, it has relied on coast guard and maritime militia forces, operating in the “gray zone” between war and peace. … … …

***

Prashanth Parameswaran, “Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson on China and the Maritime Gray Zone,” The Diplomat, 14 May 2019.

How China thinks about and acts in the maritime gray zone, and what that means for the region’s future.

Over the past few years, as China has continued its expansion in the maritime domain, scholars and practitioners alike have honed in on the subject of how Beijing operates in the so-called “gray zone” between war and peace, staying below the threshold of armed conflict to secure gains while not provoking military responses by others, including the United States. Understanding the dynamics of this has important implications not only for particular maritime spaces, such as the East China Sea and the South China Sea, but also for broader issues such as the management of U.S.-China competition and wider regional peace and stability.

The Diplomat’s senior editor, Prashanth Parameswaran, recently spoke to Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson, both affiliated with the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute, about how China thinks about and acts in the maritime gray zone and what that might mean for the region’s future. The discussion was framed around the release of a new edited volume by the authors in March entitled China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations.

One of the core contributions of the book is providing a detailed and systematic understanding of how China itself thinks about the maritime gray zone – both on its own terms as well as how it related to broader Chinese foreign and defense policy – with a detailed use of Chinese sources. What are some of the key takeaways about how China thinks about the maritime gray zone in particular, in terms of how it is defined as well as the objectives and key components of China’s approach? And what would you flag as some of the areas of similarity and difference with respect to how others may think of these challenges and talk about them?

China is much more transparent in Chinese. And, particularly in native-language sources, Chinese policymakers are very clear about the fact that their long-term goal is to exercise “administrative control” over all of the 3 million square kilometers of Chinese-claimed maritime space. This includes all of the Bohai Gulf, large sections of the Yellow Sea and East China Sea, and all of the area within the nine-dash line in the South China Sea. Many Western analysts assume that China has more abstract aims, like discrediting the international legal order. This may happen anyway, as a byproduct of their actions, but the most compelling evidence suggests that Beijing sees strategic, economic, and symbolic value in controlling as much space as possible within the First Island Chain.

Chinese leaders don’t use the term “gray zone” to describe their approach to asserting control over this space. For at least a decade, they have conceived of their policy as a balancing act. On the one hand, they feel the need to defend and advance China’s claims. They call these actions “maritime rights protection.” On the other hand, they want to avoid severely harming their relations with other states. Regional stability, after all, is vital for sustaining China’s economic development — which remains the core of China’s grand strategy. Using paranaval forces like the coast guard and the militia allows them to find an optimal balance between “rights protection” and “stability maintenance.” Paranaval forces are much less provocative than gray-hulled warships. The Chinese coast guard operates on the pretext of routine law enforcement, and militia often pretend to be fishermen. Yet both forces can be used to pursue traditional military objectives of controlling space. … … …

***

Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 11 March 2019.

- Republished as “Interview: China’s Maritime ‘Gray Zone’ Operations,” The Maritime Executive, 2019.

On March 15th, the Naval Institute Press will publish China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations, a volume edited by professors Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson from the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. CIMSEC recently reached out to Erickson and Martinson about their latest work. … …

Q: The title of your book is China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations. How does the term “gray zone” apply here?

Martinson: We usually prefer to use Chinese concepts when talking about Chinese behavior, and Chinese strategist do not generally use the term “gray zone.” But we think that the concept nicely captures the essence of the Chinese approach. We were inspired by the important work done by RAND analyst Michael Mazarr, who contributed a chapter to the volume. In his view, gray zone strategies have three primary characteristics. They seek to alter the status quo. They do so gradually. And they employ “unconventional” elements of state power. Today, a large proportion of Chinese-claimed maritime space is controlled or contested by other countries. This is the status quo that Beijing seeks to alter. Its campaign to assert control over these areas has progressed over a number of years. Clearly, then, Chinese leaders are in no rush to achieve their objectives. And while China’s Navy plays a very important role in this strategy, it is not the chief protagonist.

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “China’s Far Seas Naval Operations, From the Year of the Snake to the Year of the Pig,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 18 February 2019.

Every year, about this time, the leaders of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) send their regards to Chinese sailors deployed overseas during the Lunar New Year. Every year these messages are covered by the Chinese press. Few in China pay attention to these reports. Fewer foreign observers even know of them, but they should. This annual ritual tells the story of China’s emergence as a global naval power.

***

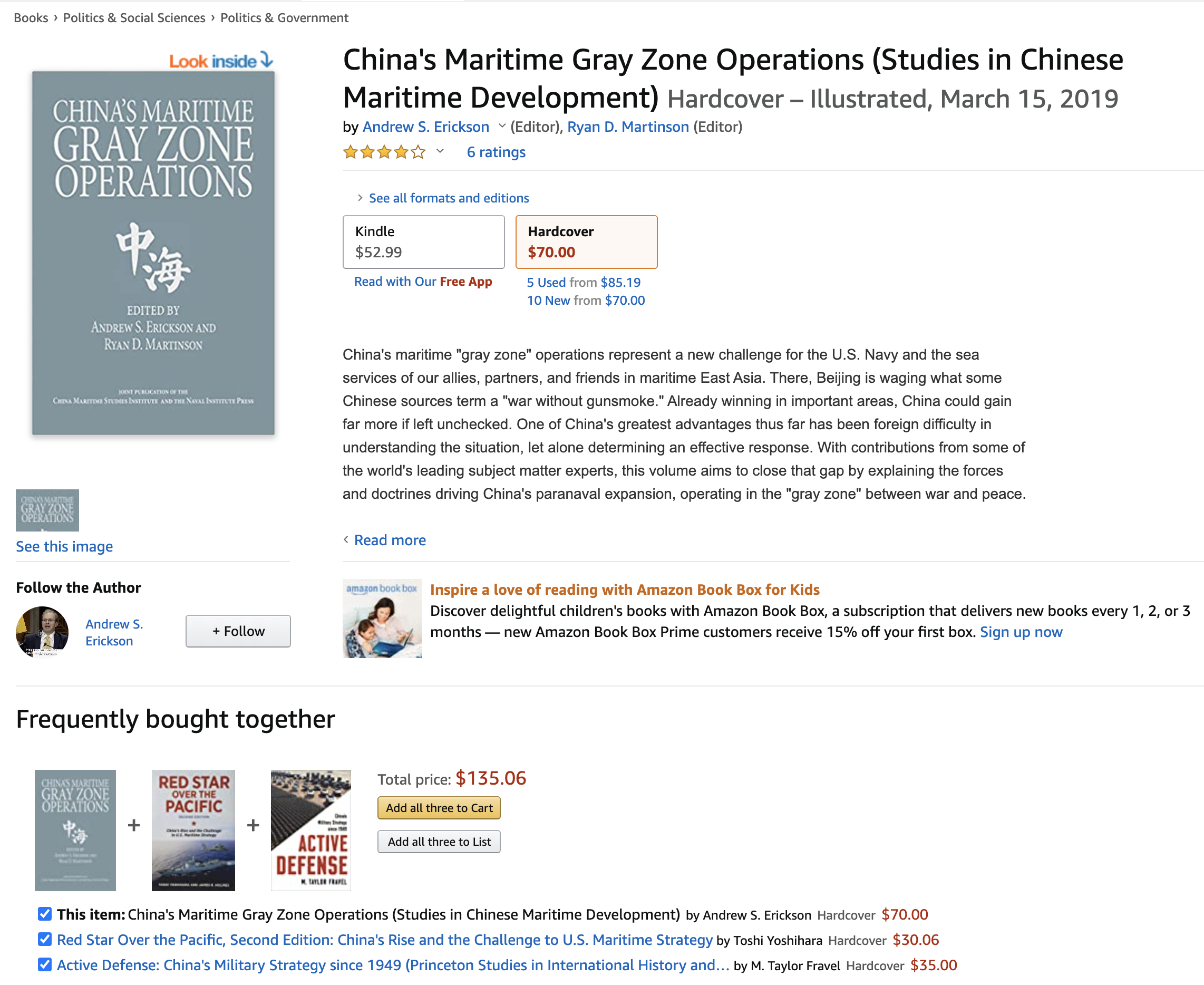

Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, eds., China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019).

- Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Introduction: ‘War Without Gun Smoke’—China’s Paranaval Challenge in the Maritime Gray Zone,” 1-11.

- Ryan D. Martinson, “Militarizing Coast Guard Operations in the Maritime Gray Zone,” 92-107.

- Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Conclusion: Options for the Definitive Use of U.S. Sea Power in the Gray Zone,” 291-301.

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Assessing the Future of Chinese Sea Power: Insights from the ‘Marine Science and Technology Award’,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief 19.2 (18 January 2019).

Ryan D. Martinson and Peter A. Dutton, China’s Distant-Ocean Survey Activities: Implications for U.S. National Security, China Maritime Report 3 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2018).

Ryan Martinson and Peter Dutton, “Chinese Scientists Want to Conduct Research in U.S. Waters—Should Washington Let Them?” The National Interest, 4 November 2018.

Ryan D. Martinson, Echelon Defense: The Role of Sea Power in Chinese Maritime Dispute Strategy, Naval War College China Maritime Study 15 (February 2018).

Ryan D. Martinson and Katsuya Yamamoto, “How China’s Navy Is Preparing to Fight in the ‘Far Seas’,” The National Interest, 18 July 2017.

Ryan D. Martinson and Katsuya Yamamoto, “Three PLAN Officers May Have Just Revealed What China Wants in the South China Sea,” The National Interest, 9 July 2017.

Ryan D. Martinson, The Arming of China’s Maritime Frontier, China Maritime Report 2 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, June 2017).

James E. Fanell and Ryan D. Martinson, “Countering Chinese Expansion through Mass Enlightenment,” Center for International Maritime Security, 18 October 2016.

Ryan D. Martinson, “The Scholar as Portent of Chinese Actions in the South China Sea,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 25 July 2016.

Ryan D. Martinson, “Panning for Gold: Assessing Chinese Maritime Strategy from Primary Sources,” Naval War College Review 69.3 (Summer 2016): 23-44.

Ryan D. Martinson, “The Courage to Fight and Win: The PLA Cultivates Xuexing for the Wars of the Future,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief 16.9, 1 June 2016.

Ryan D. Martinson, “Shepherds of the South Seas,” Survival 58.3 (2016): 187-212.

Ryan D. Martinson, “The 13th Five-Year Plan: A New Chapter in China’s Maritime Transformation,” Jamestown China Brief, 12 January 2016.

Ryan D. Martinson, “Deciphering China’s Armed Intrusion Near the Senkaku Islands,” The Diplomat, 11 January 2016.

Ryan D. Martinson, “China’s Great Balancing Act Unfolds: Enforcing Maritime Rights vs. Stability,” The National Interest, 11 September 2015.

Ryan D. Martinson, “From Words to Actions: The Creation of the China Coast Guard,” a paper for the China as a “Maritime Power” Conference, CNA Corporation, Arlington, VA, 28-29 July 2015.

Ryan D. Martinson, “East Asian Security in the Age of the Chinese Mega-Cutter,” Center for International Maritime Security, 3 July 2015.

Ryan D. Martinson, “China’s Second Navy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 141.4 (April 2015).

Ryan D. Martinson, “Reality Check: China’s Military Power Threatens America,” The National Interest, 4 March 2015.

Ryan D. Martinson, “Jinglue Haiyang: The Naval Implications of Xi Jinping’s New Strategic Concept,” Jamestown China Brief (9 January 2015).

Ryan D. Martinson, “Chinese Maritime Activism: Strategy Or Vagary?” The Diplomat, 18 December 2014.

Ryan D. Martinson, “The Militarization of China’s Coast Guard,” The Diplomat, 21 November 2014.

Ryan D. Martinson, “Here Comes China’s Great White Fleet,” The National Interest, 1 October 2014.

Ryan Martinson, “Power to the Provinces: The Devolution of China’s Maritime Rights Protection,” Jamestown China Brief 14.17 (10 September 2014).

About Ryan D. Martinson

Assistant Professor, Strategic and Operational Research Department, Naval War College

Biography

Ryan D. Martinson is a core member of the China Maritime Studies Institute. He researches China’s maritime strategy, especially its coercive use of sea power in East Asia.

Education

MALD, Tuft University Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, 2009

Graduate Certificate, Hopkins-Nanjing Center, 2005

Beijing Language & Culture University, 2004, Language Training

Fudan University, 2003, Language Training

B.S., Union College, 1999

Awards and Decorations

John Curtis Perry Fellowship

2008

Sasakawa Grant

2008

Freeman Fellowship

2004-2005