CMSI China Maritime Report #15: “The New Chinese Marine Corps: A ‘Strategic Dagger’ in a Cross-Strait Invasion”

Conor M. Kennedy, The New Chinese Marine Corps: A “Strategic Dagger” in a Cross-Strait Invasion, China Maritime Report 15 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, October 2021).

This report discusses the recent expansion/reform of the Chinese Marine Corps in the context of a Taiwan invasion scenario.

Summary

Since 2017, the People’s Liberation Army Navy Marine Corps (PLANMC) has undergone significant expansion, growing from two brigades to eight. The major impetus behind these efforts is a desire to build the service arm into an expeditionary force capable of operating in most environments at short notice. However, PLANMC reform has also bolstered its ability to contribute to major campaigns along China’s periphery, including a Taiwan invasion scenario. This report examines the PLANMC’s role in a cross-strait amphibious campaign and analyzes how new additions to the force could be used against Taiwan. It explores what roles the PLANMC would likely play in the three major phases of a Taiwan invasion: preliminary operations; assembly, embarkation, and transit; and assault landing and establishment of a beachhead. It also examines new capabilities designed for operations beyond the initial beach assault. This report argues the PLANMC is not being configured for a traditional landing operation, but rather is focusing development toward new operational concepts that could provide unique capabilities in support of the larger campaign.

Introduction

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has two main amphibious ground combat forces, amphibious combined arms brigades in the army and the marine corps within the navy. For many years, the marine corps remained quite limited. Initially a single brigade and later expanded to two brigades, it could not contribute much to a large-scale landing campaign across the Taiwan Strait. PLA reforms in 2017 have transformed the People’s Liberation Army Navy Marine Corps (PLANMC). The force has tripled in size, garnering significant attention from Chinese and outside observers. The PLAN has also built a number of large amphibious ships to carry these forces.

While the PLANMC’s latest developments indicate the force is preparing for more diverse missions, including greater roles in overseas operations, the service arm’s chief mission remains amphibious warfare. This has important implications for Taiwanese security. Advances in its ability to conduct modern amphibious combat operations may both enhance its effectiveness in traditional beach landings and introduce new capabilities in support of the overall joint campaign against Taiwan. This report examines the PLANMC’s role in a cross-strait amphibious campaign and analyzes how new additions to the force could be used against Taiwan.

This report contains three main sections. The first section discusses the service arm’s transformation and future orientation. The second section examines progress in brigade development to gauge readiness and available capabilities for landing operations. The third section analyzes the PLANMC’s likely roles in the different phases of a Taiwan invasion campaign (i.e., a “joint island landing campaign”) and explores its current ability to perform these roles. … … …

Conclusion

The PLANMC does not appear to be optimizing itself for a traditional amphibious landing against Taiwan. The force is smaller than the PLA group armies trained and equipped for a cross-strait invasion. With multiple types of battalions in each brigade, it is not configured for large-scale opposed landing operations. Compared to the PLAA’s aviation brigades, the single marine corps aviation brigade, lack of close air support, and the still unconfirmed number of air assault battalions provide very limited vertical envelopment capabilities. More importantly, the expanding missions of the PLANMC are focused overseas. As such, the PLANMC on its own will not be the force that breaks Taiwan.

Nonetheless, the PLANMC will play its part if a cross-strait invasion is launched and various force improvements will benefit its utility in the JILC. Headquarters is leading an effort to revamp the abilities of battalion commanders and staff, hoping it can improve coordination of battalion operations. New training programs are increasing the abilities of the force to transport over long distances and operate in various environments, including urban areas. Innovations in transport using RO-RO ships may allow additional amphibious lift for PLANMC forces, providing solutions for an enduring challenge for the overall JILC. The newly created brigades will eventually bring additional capabilities to the equation.

With the above limitations in mind, PLANMC scheme of maneuver ashore might be focused on smaller-scale landing operations combining ship-to-shore and ship-to-objective maneuver and special operations throughout the depth of amphibious objective areas in support of the larger campaign. Operations could focus on rapid multi-dimensional landings and maneuver to control vital objectives and conduct frontal and rear attacks against defenders.109 The PLANMC is also uniquely positioned to provide ample amphibious reconnaissance and special operations forces for preliminary operations.

Senior PRC and PLAN leadership have publicly attached great importance to the PLANMC. The first commandant of the force stated it would “strive to become a strategic dagger that General Secretary Xi and the Central Military Commission can trust and upon which they can rely heavily.”110 With significant support for their development, the PLANMC will be expected to fulfill a greater role in future operations, including a large-scale amphibious landing against Taiwan.

PREVIOUS STUDIES IN THIS CMSI SERIES:

Eric Heginbotham, Chinese Views of the Military Balance in the Western Pacific, China Maritime Report 14 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, June 2021).

Dr. Eric Heginbotham is a principal research scientist at MIT’s Center for International Studies and a specialist in Asian security issues. Before joining MIT, he was a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation, where he led research projects on China, Japan, and regional security issues and regularly briefed senior military, intelligence, and political leaders. Prior to that he was a Senior Fellow of Asian Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. After graduating from Swarthmore College, Heginbotham earned his Ph.D. in political science from MIT. He is fluent in Chinese and Japanese, and was a captain in the U.S. Army Reserve.

Summary

This report examines Chinese views about the military balance of power between China and the United States in the Western Pacific. It argues that while there is no single “Chinese” view on this topic, Chinese analysts tend to agree that 1) the gap between the two militaries has narrowed significantly in recent years, 2) the Chinese military still lags in important ways, and 3) Chinese military inferiority vis-à-vis the U.S. increases the further away it operates from the Mainland. In terms of specific areas of relative strength, the Chinese military has shown the greatest improvements in military hardware, but has farther to go in the area of jointness, training, and other military “software.” Nevertheless, despite continued criticism from senior civilian leaders, training quality has likely improved due to a greater focus on realism, and recent military reforms have, to a degree, improved the prospects for jointness.

Introduction

There is no single Chinese view of the military balance. As in the United States, there are many perspectives, informed by personal biases and access to different source material. Conclusions also differ depending on the specific circumstances of each scenario—the adversary, geography, warning time, casus belli, and early crisis decision making. To the extent that it is possible to generalize, the range of Chinese assessments do not, in aggregate, appear to dramatically differ from professional or informed analyses by Western experts. The Chinese leadership recognizes both the remarkable strides that have been made in modernizing the Chinese military, as well as important continuing weaknesses. Chinese analysts agree with American counterparts that Chinese capabilities are far more formidable immediately offshore than they are in more distant locations.

To an extent, the reason for broad consensus across the Pacific lies in the exchange of ideas between Western and Chinese analysts. Chinese views may be a function of ready access to translated Western analyses, which in turn rely heavily on anecdotes and analyses found in published Chinese sources.

To say that there is general agreement on the balance of power does not imply a complete agreement or identity between Chinese and U.S. views. Systematic biases may affect the assessments of each state, as well as different groups within them. High levels of U.S. operational proficiency, a product of sophisticated training structures and regimes developed after the Vietnam War, may alert some U.S. analysts to factors that may not be considered by Chinese counterparts. Only recently, for example, has “jointness” become a guiding criterion in Chinese military decision making. Similarly, as PLA modernization contributes to an improved understanding of modern war, the analysis of military balance issues has expanded to include greater consideration of dynamic factors in combat. Improved assessment may, in turn, contribute to a more circumspect (i.e., pessimistic) assessment of the balance even as it increases Chinese prospects for overcoming challenges.

This report comprises five main parts. The first section outlines the types of source materials that reflect Chinese views, and the second touches on analytic methods behind Chinese assessments. The third section assesses how Chinese leaders and analysts view the overall balance of power today and its evolution over the last two decades. The fourth section discusses particular areas of perceived strength and weakness in PLA capabilities relative to those of the United States. The fifth section examines how Chinese analysts view the potential future impact of intensified competition with the United States and the latter’s increasingly sharp focus on competition with China. The report concludes with a summary of findings. … … …

Jennifer Rice and Erik Robb, The Origins of “Near Seas Defense and Far Seas Protection”, China Maritime Report 13 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, February 2021).

This report traces the origins and development of China’s current naval strategy: “Near Seas Defense and Far Seas Protection.” Near Seas Defense is a regional, defensive concept concerned with ensuring China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests. Its primary focus is preparing to fight and win informatized local wars within the first island chain. Far Seas Protection has both peacetime and wartime elements. In peacetime, the Chinese navy is expected to conduct a range of “non-war military operations” such as participating in international peacekeeping, providing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, evacuating Chinese citizens from danger, and engaging in joint exercises and naval diplomacy. In wartime, the PLAN could be tasked with securing China’s use of strategic sea lanes and striking important nodes and high-value targets in the enemy’s strategic depth. Nears Seas Defense and Far Seas Protection is rooted in the ideas of Alfred Thayer Mahan and Mao Zedong.

About the Authors

- Jennifer Rice is a senior intelligence analyst with the Office of Naval Intelligence. Her portfolio includes issues of naval strategy, modernization, diplomacy, and force employment. She completed her MA in Security Policy Studies at George Washington University and received a BA in English and Political Science from James Madison University.

- Erik Robb is a senior intelligence analyst with the Office of Naval Intelligence focused on Asian military affairs and DoD contingency planning. Erik received a BA from Yale University in East Asian Studies and an MA from UC San Diego in International Relations. He is also a graduate of the Hopkins-Nanjing Center.

- The views and opinions expressed herein by the authors do not represent the policies or position of the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy, and are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Introduction

In 2015, China publicized its current naval strategy of “Near Seas Defense and Far Seas Protection,” which calls for the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to expand the geographic and mission scope of its operations.1 The strategy retains the PLAN’s longstanding focus on defending China’s mainland from attack and asserting national sovereignty claims, but adds new emphasis to safeguarding China’s economic development and strategic interests by protecting sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and engaging in long-distance security missions. The concept of Far Seas Protection is guiding the PLAN’s transformation into a global navy able to conduct both high-intensity combat operations and a variety of peacetime missions. This transformation is well underway and Beijing likely has established goals for its completion. However, these goals are probably not rigid because of factors beyond China’s control. The pace at which the PLAN completes this transformation will depend on other countries’ willingness to accommodate China’s naval ambitions and on the emergence of new global missions arising from transnational security threats or humanitarian crises. … …

p. 6

Intellectual Roots

China’s current naval strategy is rooted in the ideas of Alfred Thayer Mahan and Mao Zedong. Although other Western and Chinese thinkers have also informed the PLAN’s strategy, the influence of Mahan and Mao is unmistakable. Far Seas Protection’s emphasis on safeguarding China’s SLOCs and overseas interests echoes Mahan’s thinking about the interdependency of economic prosperity and naval power.24 Mahan believed that a strong nation requires a powerful navy to protect its overseas commercial interests and the SLOCs connecting those interests. He also believed the corollary, that a nation’s commercial interests generate the wealth to fund a powerful navy. Beijing increasingly links China’s future economic development with sea power. As described in one authoritative volume, “the seas and oceans bear on the enduring peace, lasting stability and sustainable development of China… it is necessary for China to develop a modern maritime military forces structure commensurate with its national security and development interests.”25 Secure SLOCs are the “lifelines” of China’s economic development.26

Mahan further maintained that the imperative to control SLOCs would cause great powers to compete for “command of the sea,” which he defined as “that overbearing power on the sea which drives the enemy’s flag from it.”27 A nation that enjoys command of the sea can shield its seaborne trade from enemy disruption. China’s strategy incorporates Mahan’s concepts of command of the sea as well as sea control (these concepts are not identical; sea control is more limited in scope to temporary control of a specific area).28 The PLA has long viewed command of the sea (制海权) as critical to the success of blockade or island landing campaigns against Taiwan. The PLA is now emphasizing control more comprehensively across multiple domains, in light of today’s increasingly complex and informatized operations. “Comprehensive control” (综合控制权) is the ability to control the surface, undersea, air, and space domains and seamlessly integrate the forces operating in these domains through networked information and command systems. 29 In this expanded conceptualization of sea control, the networked systems are every bit as important as the ships and aircraft they are meant to support.

China’s strategy also demonstrates the enduring influence of Mao, whose concept of active defense (积极防御) remains the PLA’s guiding principle.30 Active defense combines strategic defense with campaign offense and is a fluid concept; its focus shifts from defense to offense when conditions are advantageous to do so. Mao recognized that although defense is important, ultimately offense is necessary to bring about victory.31 This concern for the offense resonates with contemporary Chinese strategists. The authors of the 2015 Defense White Paper instruct the PLA to “seize the strategic

p. 7

initiative in military struggle.”32 According to the 2013 Science of Military Strategy, future guidance to China’s navy will “elevate offense from the campaign and tactical levels to the strategic level.” China “cannot wait for the enemy to attack,” but rather should engage in “strategic attack activities.”33 Similarly, another source notes that once an “opponent has already set in motion his war machine, and avoiding war is no longer possible…[China] must set in motion [its] war machine to prevent being passively caught up in war” and to control the war’s initiation and escalation.34Although China frames its military power as a means of defense, Chinese leaders and strategists provide the authority to act offensively and proactively to defend its interests. … …

p. 12

The PLAN’s Future—Power Projection, Expeditionary Missions, and Nuclear Submarines

The PLAN’s strategy of Near Seas Defense and Far Seas Protection and China’s new priority to defend the maritime domain will likely shape the composition and employment of naval forces for decades to come. Far Seas Protection will require greater emphasis on global power projection and expeditionary capabilities. China’s aircraft carrier force may become one of the most visible aspects of its modern, blue-water force and the PLAN will need to develop new concepts of operations and tactics to enable secure, integrated aircraft carrier task group operations in the far seas. Chinese military experts have advocated for a force of up to six aircraft

p. 13

carriers, including nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, by the mid-2030s in order to better accomplish China’s national defense missions and sustain blue-water operations.6

In addition, Far Seas Protection will require the PLAN to refine and enhance its ability to support global expeditionary operations to secure China’s national strategic and economic interests, including defense or interdiction of SLOCs and force projection in littoral areas around the world. China will acquire large, multi-mission expeditionary platforms such as LPDs and LHAs for this purpose. These ships will likely carry out a variety of missions including counter-piracy, troop insertion, and HA/DR and medical response.

As the PLAN continues its effort to “go global” to fulfill the requirements of the new naval strategy in the far seas, Beijing will likely identify additional missions for its nuclear submarine force. The PLAN has already begun to deploy submarines into the Indian Ocean to support ongoing security operations.65 If Beijing wishes to extend the distance or increase the number of its far seas submarine deployments, the PLAN will likely need to acquire additional nuclear submarines because they have greater endurance than conventional submarines, which make up most of China’s current submarine force.

p. 14

Beijing’s Timeline to Advance Its Naval Strategy

China likely adheres to a clear timeline for aspects of naval development over which Beijing exerts direct control, such as platform construction and far seas deployments. During his speech to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, Xi outlined requirements for the PLA to become a mechanized force by 2020, a fully modernized force by 2035, and a “world-class” force by 2050.66 Beijing conveys more specific near-term guidance through its Five Year Plans, which direct research, development, and acquisition, and through the Outline for Military Training.67 Each service of the PLA likely has a force modernization strategy and training plan linked to these directives.

However, certain aspects of Far Seas Protection are outside of Beijing’s control either because they rely on foreign partnerships and cooperation or because they are driven by circumstances. For example, China’s pursuit of overseas basing and port access agreements is opportunistic and depends on the willingness of potential host countries to accommodate the PLAN. Although Beijing might seek to influence favorable responses from these countries through infrastructure investment, diplomatic and military engagement, and other economic incentives, the potential host’s receptivity to China’s naval presence is ultimately beyond Beijing’s control. Furthermore, unless Beijing changes its longstanding aversion to formal alliances, other countries have no binding incentive to aid China during wartime.

Security cooperation efforts similarly rely on regional or international consensus to implement. The UN endorsed international counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, enabling foreign navies to conduct security operations in Somalian waters. Without this type of top-level support, and the underlying security crisis that required action, the PLAN may never have embarked on a continuous far seas mission in 2008. In contrast, since at least 2012 Beijing has publicly called for international support to combat piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, working through the UN, bilateral exchanges, and other forums to open a debate and seek consensus on a cooperative security effort.68 China’s 2015 Defense White Paper pledged to help African countries ensure navigational security in the Gulf of Guinea.69 However, despite these efforts, Beijing has not succeeded in gaining the regional and international support to establish a security coalition in the Gulf of Guinea. The emergence of security threats, international unrest, natural disasters, and other humanitarian crises cannot be predicted or directed, but all of these provide opportunities to engage military forces, often in new ways and in new areas of the world.

Zachary Haver, Sansha City in China’s South China Sea Strategy: Building a System of Administrative Control, China Maritime Report 12 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, January 2021).

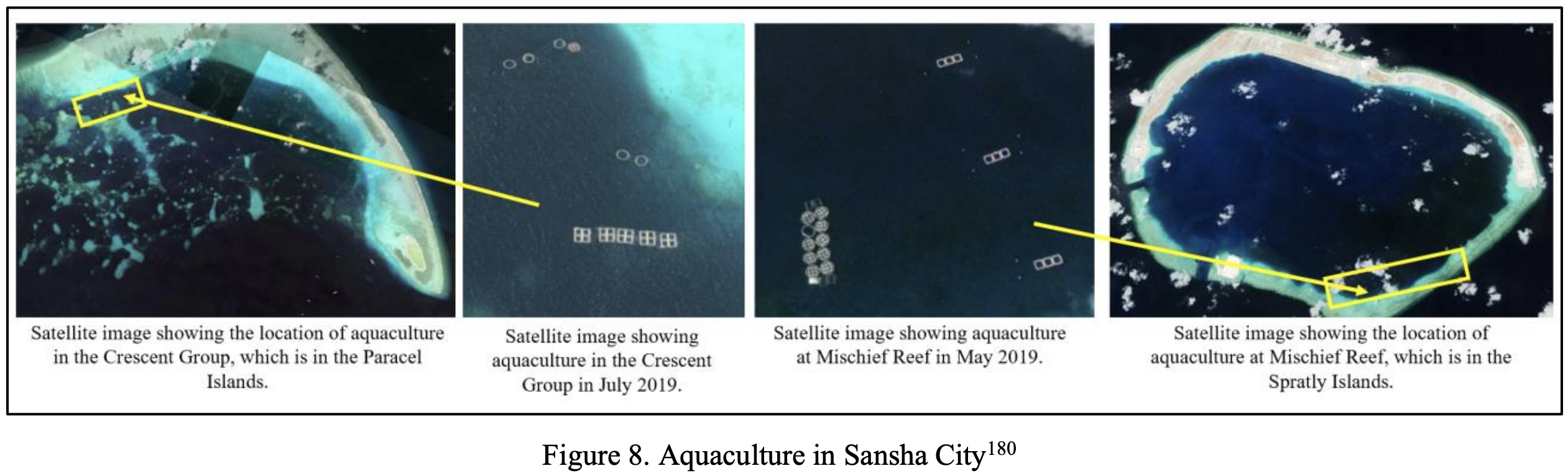

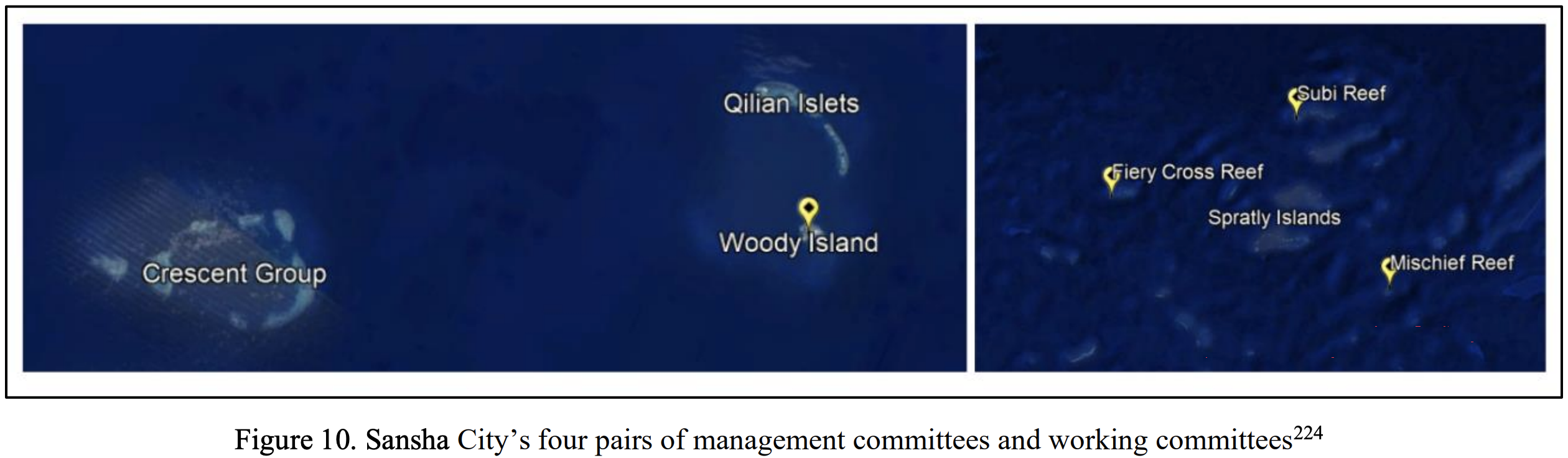

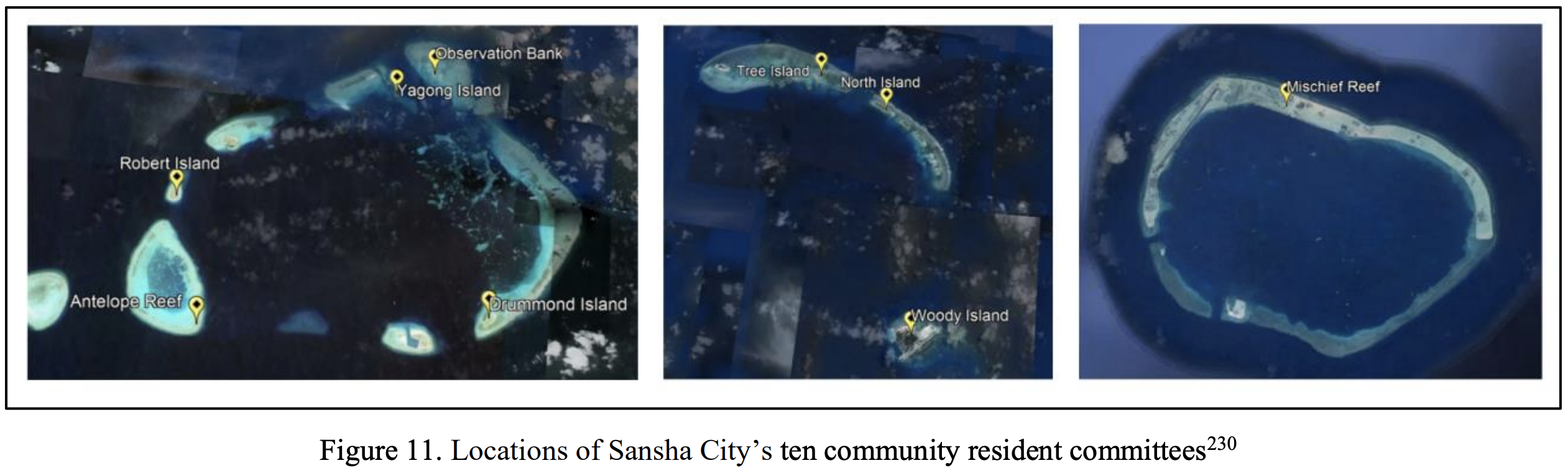

China established Sansha City in 2012 to administer the bulk of its territorial and maritime claims in the South China Sea. Sansha is headquartered on Woody Island. The city’s jurisdiction includes the Paracel Islands, Zhongsha Islands, and Spratly Islands and most of the waters within China’s “nine-dash line.” Sansha is responsible for exercising administrative control, implementing military-civil fusion, and carrying out the day-to-day work of rights defense, stability maintenance, environmental protection, and resource development. Since 2012, each level of the Chinese party-state system has worked to develop Sansha, improving the city’s physical infrastructure and transportation, communications, corporate ecosystem, party-state institutions, and rights defense system. In effect, the city’s development has produced a system of normalized administrative control. This system ultimately allows China to govern contested areas of the South China Sea as if they were Chinese territory.

Key Findings

- Sansha is responsible for administering China’s maritime and territorial claims in the South China Sea on a day-to-day basis from the front lines of the disputes.

- Sansha’s physical infrastructure, transportation, communications, economy, party-state institutions, and defense capabilities form a unified system that continuously strengthens the city’s capacity to exercise administrative control over contested areas of the South China Sea.

- The city uses civilian-administrative means, including maritime law enforcement and maritime militia operations, rather than military force to advance China’s position in the South China Sea disputes.

- The development of Sansha is gradually civilianizing and institutionalizing China’s efforts to control the South China Sea, providing a mechanism to govern contested areas as if they were Chinese territory.

- The city’s development aligns closely with China’s broader strategy in the South China Sea, which aims to consolidate China’s claims while deterring other states from strengthening their own claims. This strategy relies on China Coast Guard (CCG) and maritime militia operations backed by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy.

- Military-civil fusion is the guiding principle of the city’s development, which ensures that all aspects of Sansha’s development ultimately serve China’s sovereignty and security interests.

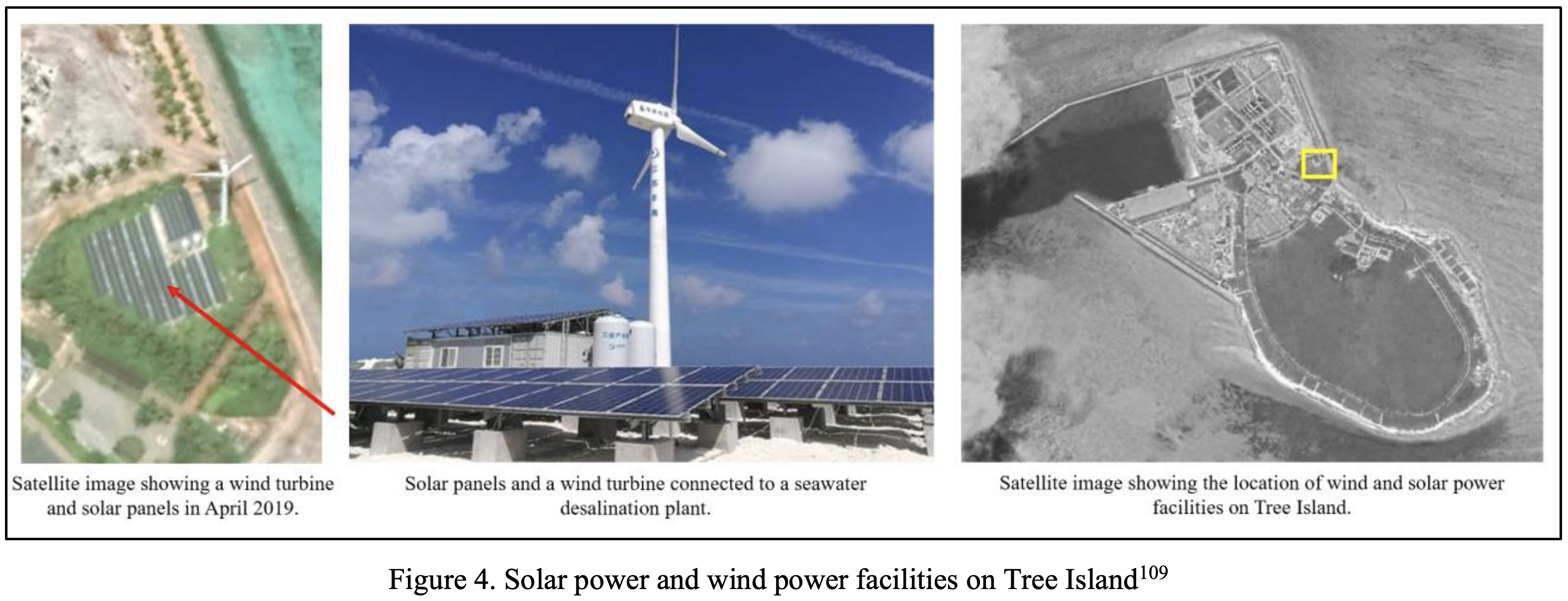

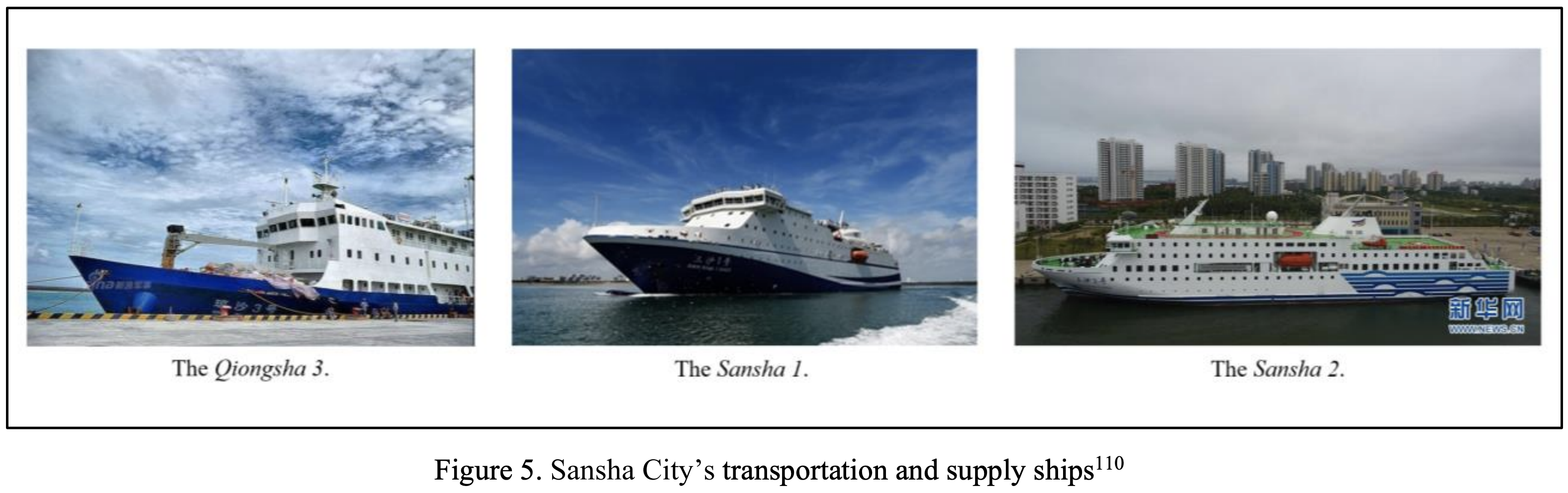

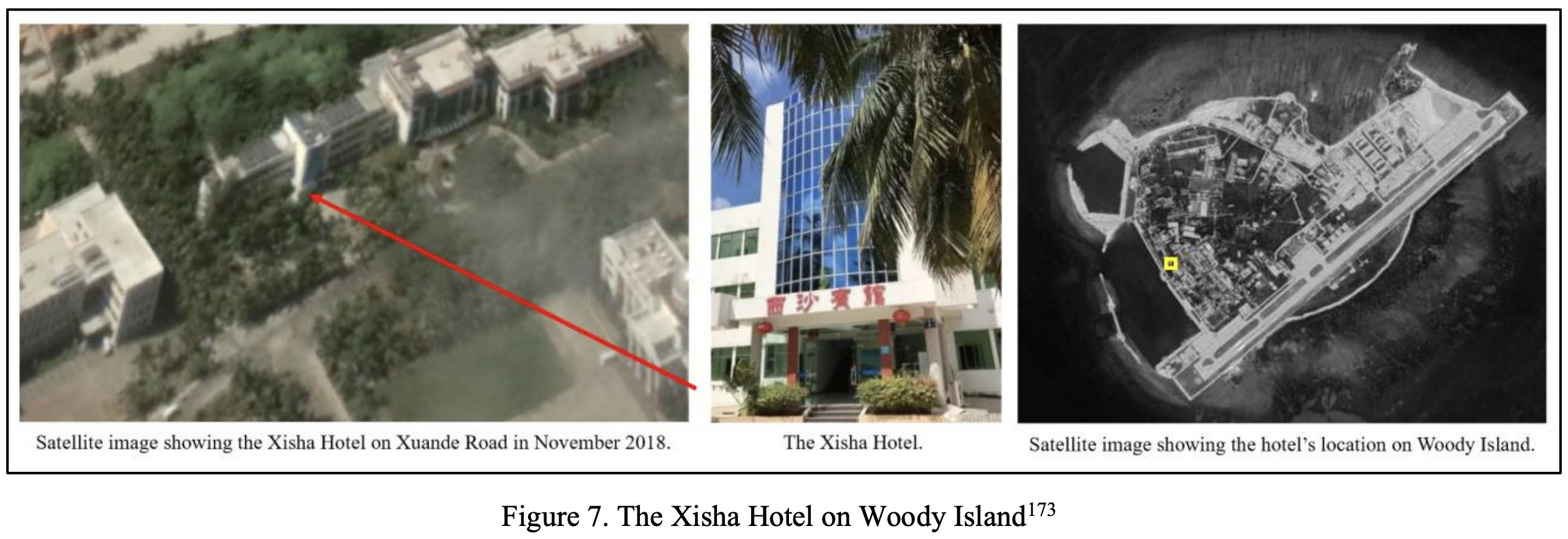

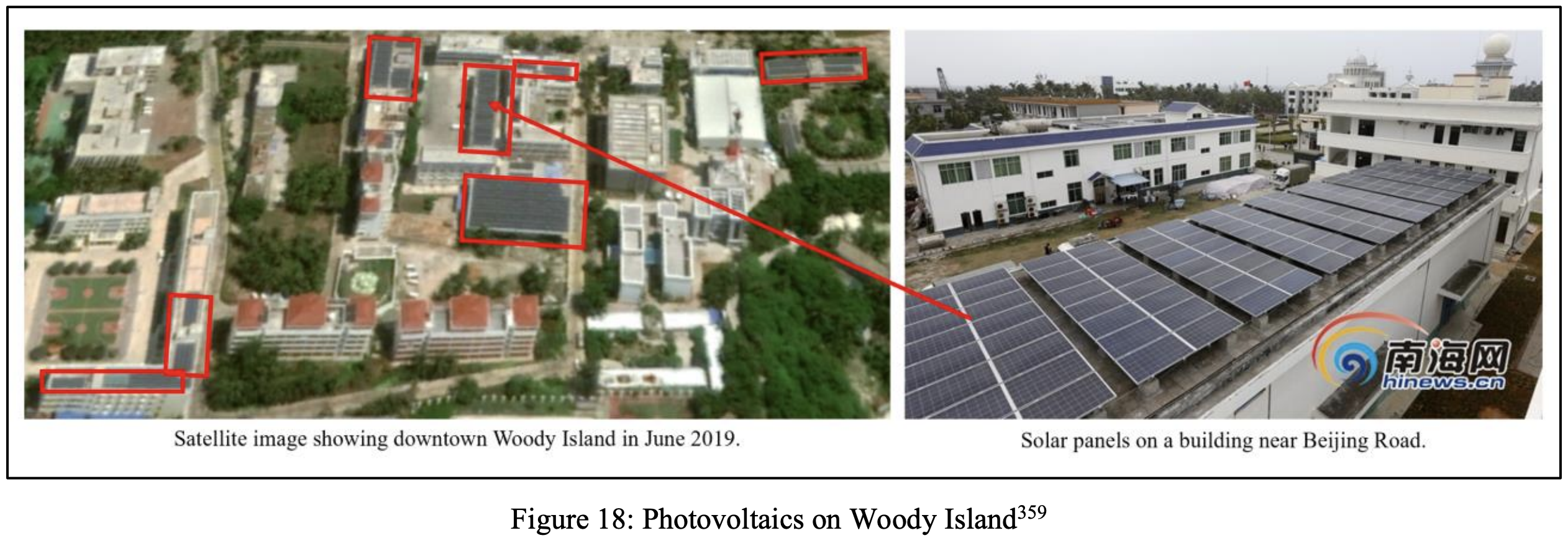

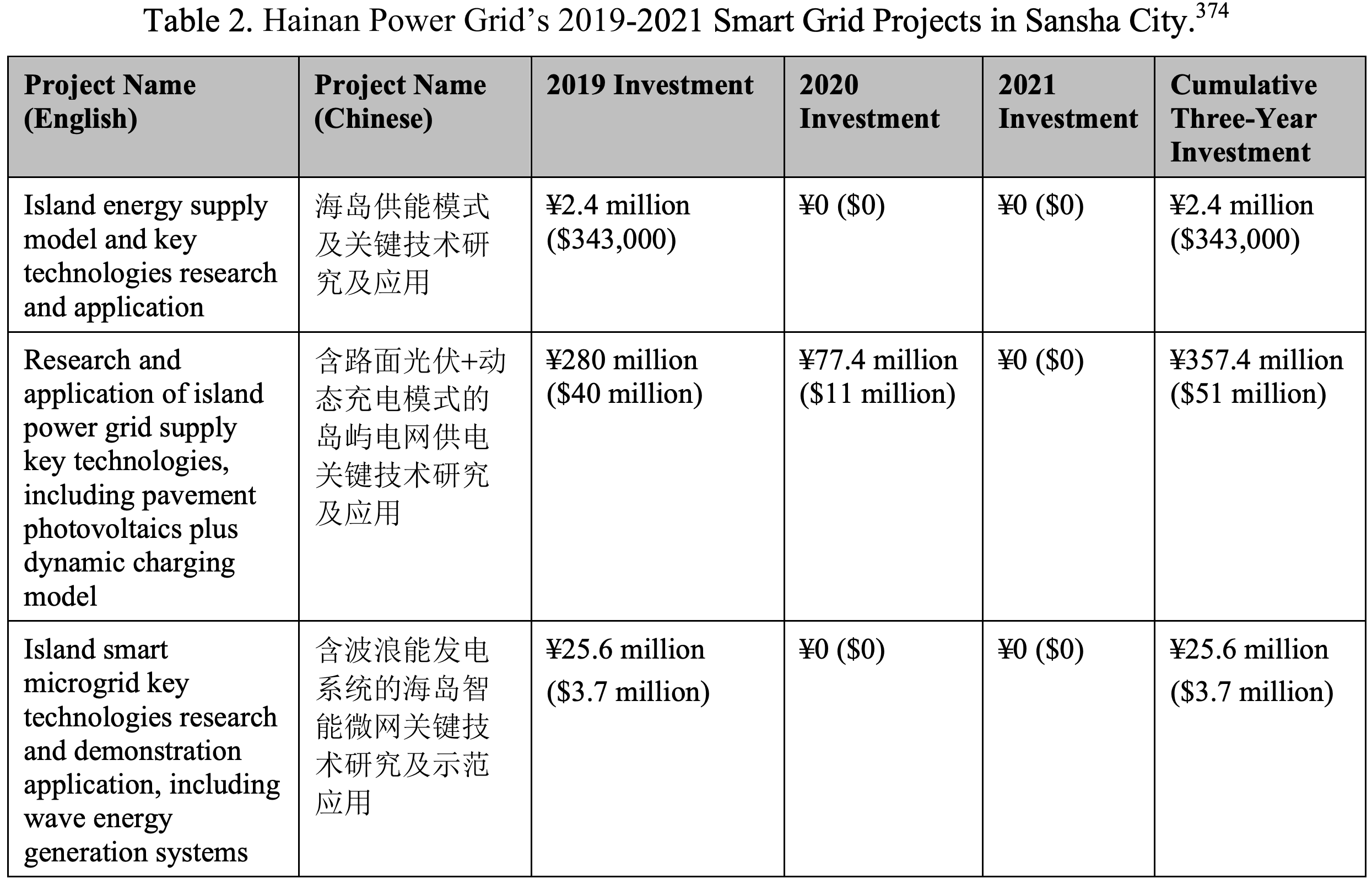

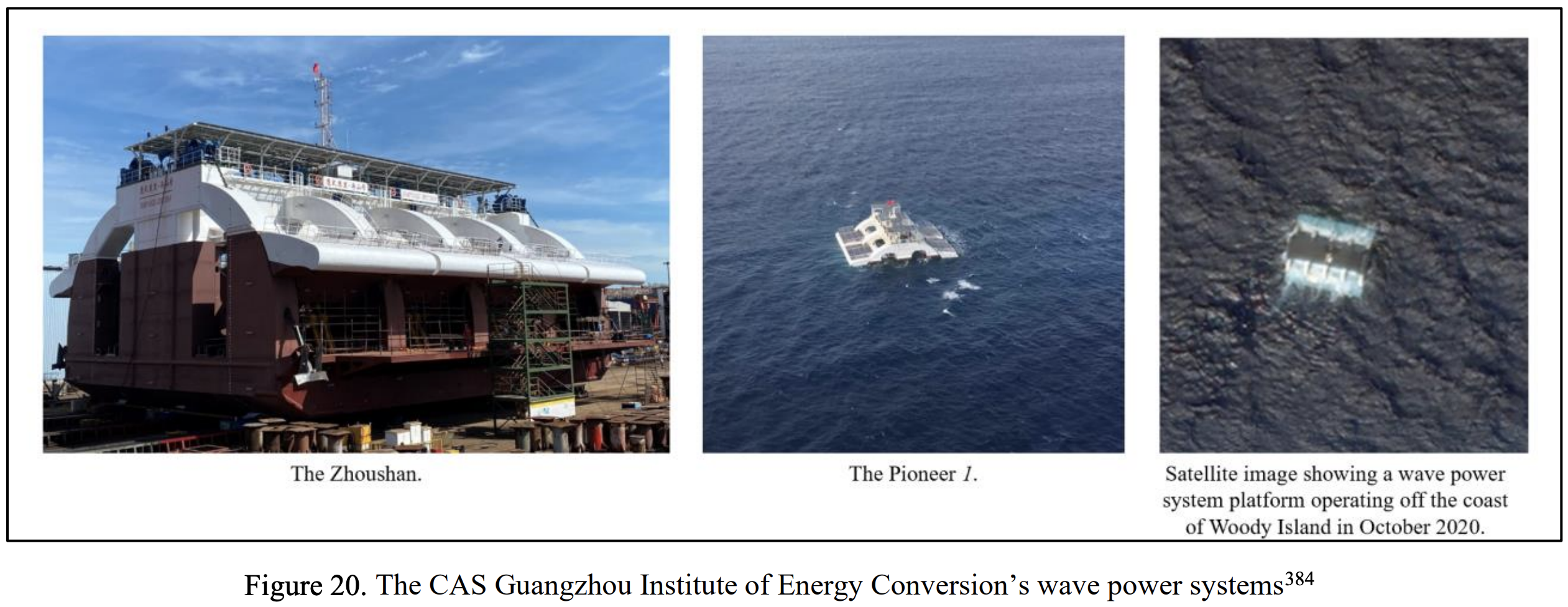

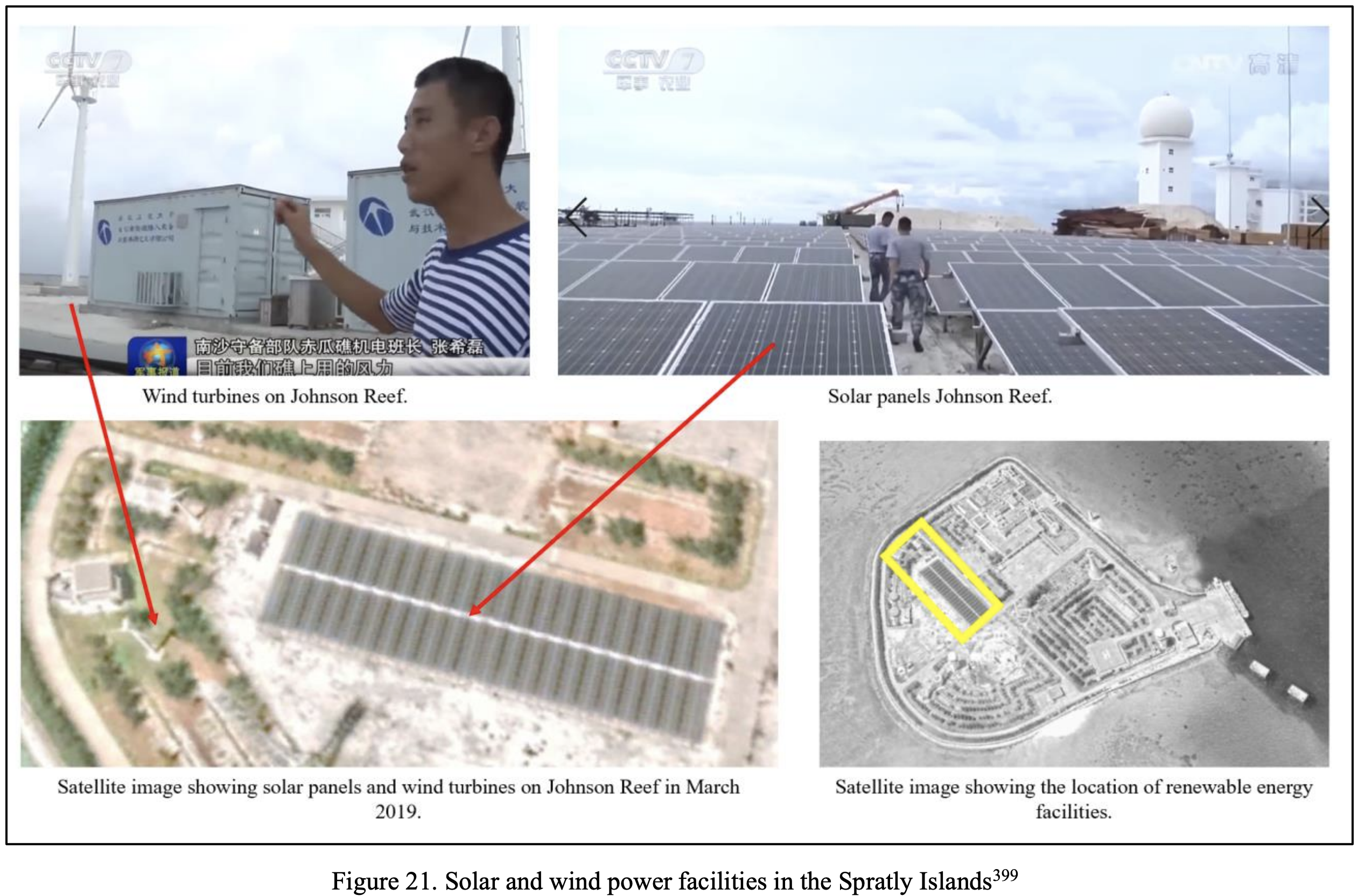

- Improvements to Sansha’s physical infrastructure and transportation, including the construction of a smart microgrid on Woody Island, allow Woody Island and other occupied features to accommodate a growing number of military, civilian, and law enforcement personnel and guarantee the continuous operation of important facilities.

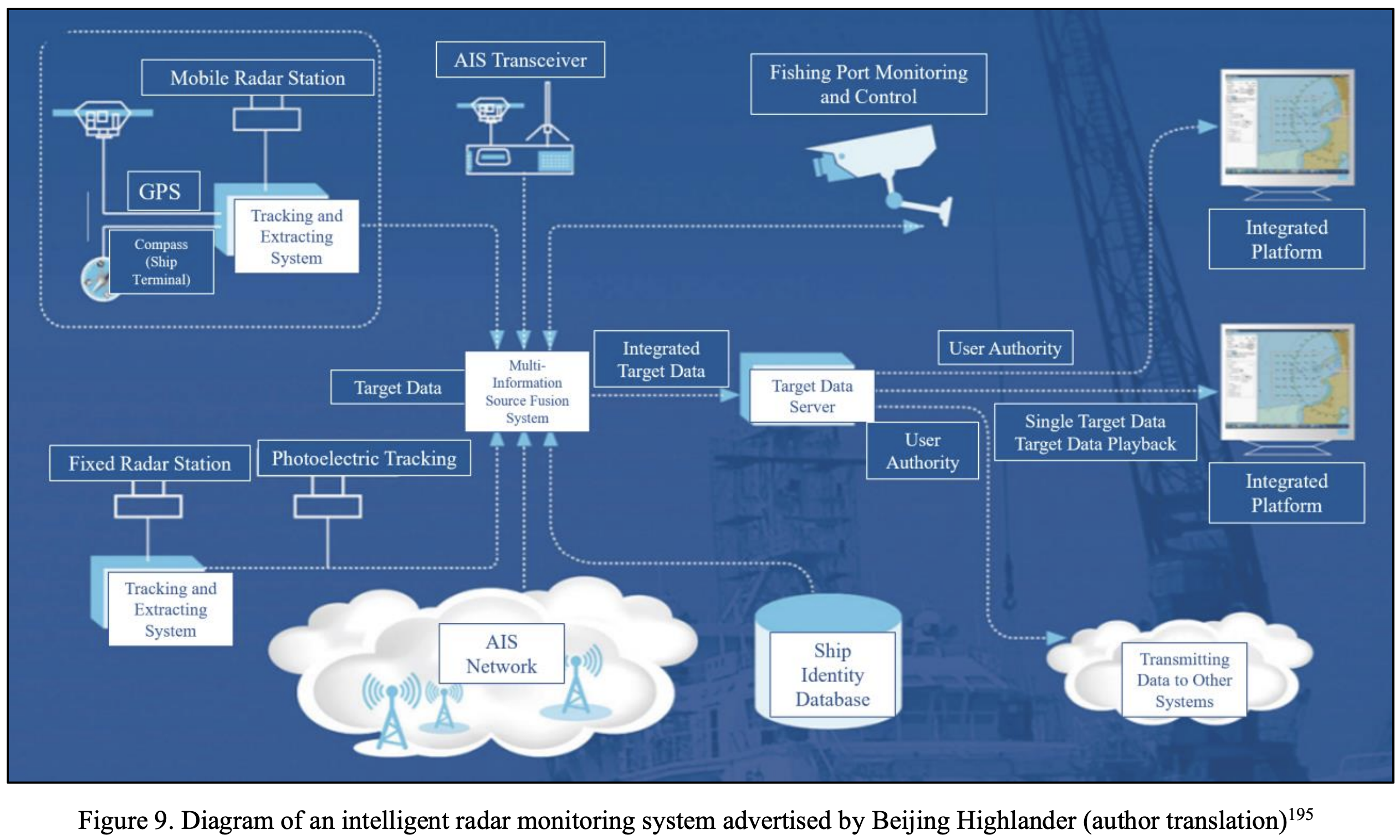

- The development of the city’s communications infrastructure enables local leaders to monitor and govern vast swathes of contested maritime space with ease.

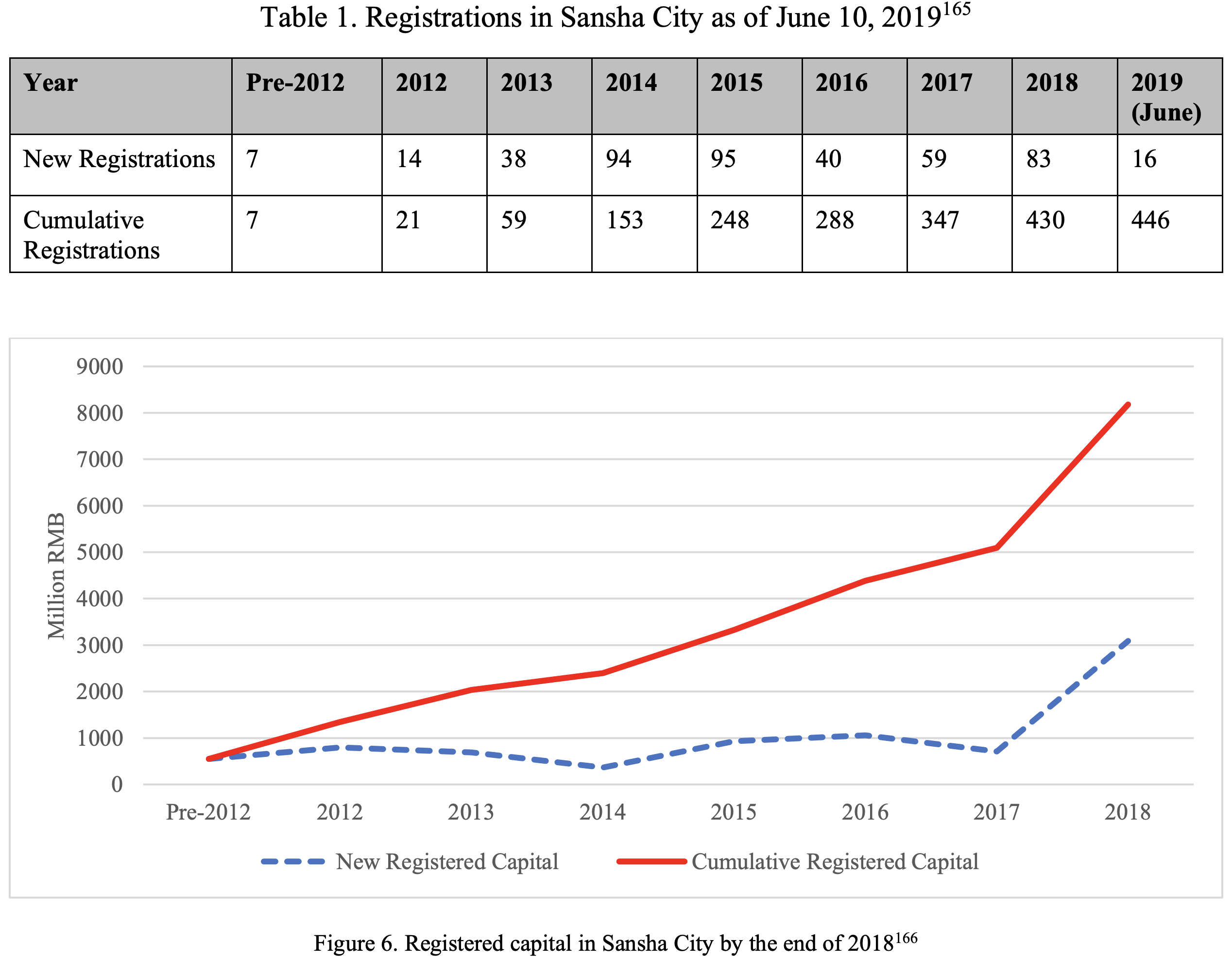

- Sansha’s leaders have systematically mobilized private and state-owned enterprises in support of nearly every aspect of the city’s daily operations and long-term development.

- The expansion of the city’s party-state institutions allows municipal authorities to directly govern contested areas of the South China Sea and ensures the primacy of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) interests in local decision-making.

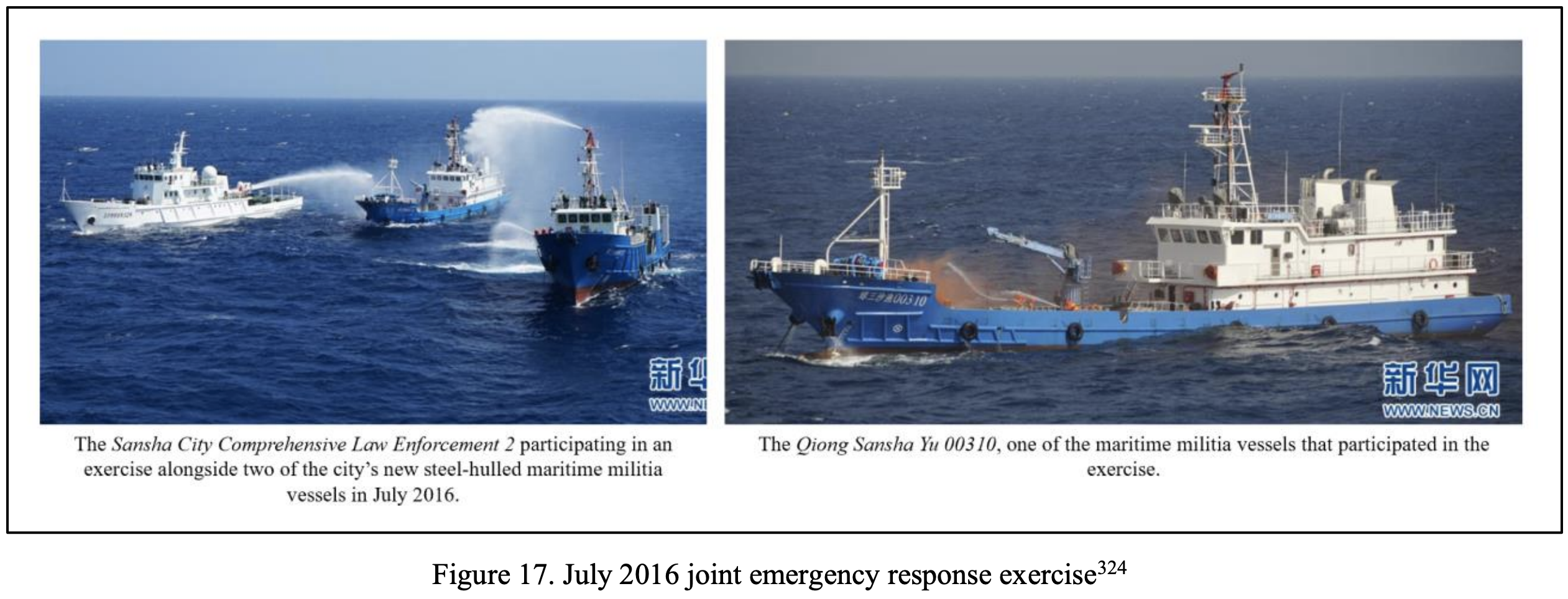

- To defend China’s maritime rights and interests, the city created Sansha Comprehensive Law Enforcement (SCLE), a maritime law enforcement force, and established a new maritime militia force. Sansha has integrated both forces into its military, law enforcement, and civilian joint defense system. Using these capabilities, local leaders physically assert Sansha’s jurisdiction at the expense of China’s neighbors and coordinate joint operations with the CCG.

- Sansha’s system of normalized administrative control is currently strongest in the Paracel Islands. Despite the continuing influence of the central bureaucracies, CCG, and PLA, elements of this system also exist in the Spratly Islands and show signs of expanding.

About the Author

Zachary Haver is a Party Watch Initiative Fellow at the Center for Advanced China Research. His research focuses on the South China Sea disputes and Chinese economic statecraft. He has worked on Chinese security and economic issues at SOS International LLC, the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), the U.S. Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, and the Columbia-Harvard China and the World Program. Zachary received his BA in International Affairs from George Washington University. He lived in China for three years, studied Chinese in both Taiwan and China, and is proficient in Mandarin Chinese.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Isaac Kardon and the rest of the China Maritime Studies Institute team for their encouragement and helpful feedback. Moreover, this project would not have possible without generous support from the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS). Finally, the author thanks Devin Thorne for his valuable contributions.

Jeffrey Becker, Securing China’s Lifelines across the Indian Ocean, China Maritime Report 11 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, December 2020).

How is China thinking about protecting sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and maritime chokepoints in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) in times of crisis or conflict? Relying on Chinese policy documents and writings by Chinese security analysts, this report argues that three critical challenges limit the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN’s) ability to project power into the region and defend access to SLOCs and chokepoints, particularly in times of crisis: (1) the PLAN’s relatively modest presence in the region compared to other powers, (2) its limited air defense and anti-submarine warfare capabilities, and (3) its limited logistics and sustainment infrastructure in the region. To address these challenges, Beijing has already undertaken a series of initiatives, including expanding the capabilities of China’s base in Djibouti and leveraging the nation’s extensive commercial shipping fleet to provide logistics support. Evidence suggests that the PRC may also be pursuing other policy options as well, such as increasing the number of advanced PLAN assets deployed to the region and establishing additional overseas military facilities.

Capt. Christopher P. Carlson, USNR (Ret.), PLAN Force Structure Projection Concept: A Methodology for Looking Down Range, China Maritime Report 10 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2020).

Force structure projections of an adversary’s potential order of battle are an essential input into the strategic planning process. Currently, the majority of predictions regarding China’s future naval buildup are based on a simple extrapolation of the impressive historical ship construction rate and shipyard capacity, without acknowledging that the political and economic situation in China has changed dramatically. Basing force structure projections on total life-cycle costs would be the ideal metric, but there is little hope of getting reliable data out of China. A reasonable substitute in shipbuilding is to look at the construction man-hours, as direct labor accounts for 30-50 percent of a ship’s acquisition cost, depending on the ship type, and is therefore a representative metric of the amount of resources and effort applied to a ship’s construction. The direct labor man-hours to build a Chinese surface combatant can be estimated by linking a ship’s outfit density to historical U.S. information. This analytical model also allows for the inclusion of the mid-life overhaul and modernization for each ship, which is a major capital expense in the out years following initial procurement. For the naval analyst examining the Chinese Navy’s future force structure, the outfit density concept provides a tool to evaluate the degree of national effort when it comes to military shipbuilding.

Roderick Lee and Morgan Clemens, Organizing to Fight in the Far Seas: The Chinese Navy in an Era of Military Reform, China Maritime Report 9 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, October 2020).

CMSI has just published China Maritime Report No. 9, entitled Organizing to Fight in the Far Seas: The Chinese Navy in an Era of Military Reform. Written by Mr. Roderick Lee and Mr. Morgan Clemens, this report discusses the challenges that PLA reform and PLA Navy (PLAN) strategy intend to resolve, highlights key organizational developments within the PLAN that preceded China’s military reform, and discusses the known facts of command and control of PLAN forces operating in the far seas.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has been laying the organizational groundwork for far seas operations for nearly two decades, developing logistical and command infrastructure to support a “near seas defense and far seas protection” strategy. In the context of such a strategy, the PLAN’s ability to project power into the far seas depends upon its ability to dominate the near seas, effectively constituting a “sword and shield” approach. Along with the rest of the PLA, the PLAN’s peacetime command structure has been brought into line with its wartime command structures, and in terms of near seas defense, those command structures have been streamlined and made joint. By contrast, the command arrangements for far seas operations have not been clearly delineated and no one organ or set of organs has been identified as responsible for them. While this is manageable in the context of China’s current, limited far seas operational presence, any meaningful increase in the size, scope, frequency, and intensity of far seas operations will require further structural reforms at the Central Military Commission and theater command levels in order to lay out clear command responsibilities.

Timothy R. Heath, Winning Friends and Influencing People: Naval Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics, China Maritime Report 8 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, September 2020).

In recent years, Chinese leaders have called on the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to carry out tasks related to naval diplomacy beyond maritime East Asia, in the “far seas.” Designed to directly support broader strategic and foreign policy objectives, the PLAN participates in a range of overtly political naval diplomatic activities, both ashore and at sea, from senior leader engagements to joint exercises with foreign navies. These activities have involved a catalogue of platforms, from surface combatants to hospital ships, and included Chinese naval personnel of all ranks. To date, these acts of naval diplomacy have been generally peaceful and cooperative in nature, owing primarily to the service’s limited power projection capabilities and China’s focus on more pressing security matters closer to home. However, in the future a more blue-water capable PLAN could serve more overtly coercive functions to defend and advance China’s rapidly growing overseas interests when operating abroad.

Isaac B. Kardon, Conor M. Kennedy, and Peter A. Dutton, Gwadar: China’s Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan, China Maritime Report 7 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, August 2020).

China Maritime Report No. 7 offers a detailed examination of China’s infrastructure project in the port of Gwadar, Pakistan. Written by Dr. Peter Dutton, Dr. Isaac Kardon, and Mr. Conor Kennedy, this report is the second in a series of studies looking at China’s interest in Indian Ocean ports and its “strategic strongpoints” there (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms. Gwadar is an inchoate “strategic strongpoint” in Pakistan that may one day serve as a major platform for China’s economic, diplomatic, and military interactions across the northern Indian Ocean region. As of August 2020, it is not a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base, but rather an underdeveloped and underutilized commercial multipurpose port built and operated by Chinese companies in service of broader PRC foreign and domestic policy objectives. Foremost among PRC objectives for Gwadar are (1) to enable direct transport between China and the Indian Ocean, and (2) to anchor an effort to stabilize western China by shoring up insecurity on its periphery. To understand these objectives, this case study first analyzes the characteristics and functions of the port, then evaluates plans for hinterland transport infrastructure connecting it to markets and resources. We then examine the linkage between development in Pakistan and security in Xinjiang. Finally, we consider the military potential of the Gwadar site, evaluating why it has not been utilized by the PLA then examining a range of uses that the port complex may provide for Chinese naval operations.

Peter A. Dutton, Isaac B. Kardon, and Conor M. Kennedy, Djibouti: China’s First Overseas Strategic Strongpoint, China Maritime Report 6 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, April 2020).

This report analyzes PRC economic and military interests and activities in Djibouti. The small, east African nation is the site of the PLA’s first overseas military base, but also serves as a major commercial hub for Chinese firms—especially in the transport and logistics industry. We explain the synthesis of China’s commercial and strategic goals in Djibouti through detailed examination of the development and operations of commercial ports and related infrastructure. Employing the “Shekou Model” of comprehensive port zone development, Chinese firms have flocked to Djibouti with the intention of transforming it into a gateway to the markets and resources of Africa—especially landlocked Ethiopia—and a transport hub for trade between Europe and Asia. With diplomatic and financial support from Beijing, PRC firms have established a China-friendly business ecosystem and a political environment that proved conducive to the establishment of a permanent military presence. The Gulf of Aden anti-piracy mission that justified the original PLA deployment in the region is now only one of several missions assigned to Chinese armed forces at Djibouti, a contingent that includes marines and special forces. The PLA is broadly responsible for the security of China’s “overseas interests,” for which Djibouti provides essential logistical support. China’s first overseas strategic strongpoint at Djibouti is a secure commercial foothold on the African continent and a military platform for expanding PLA operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

Daniel Caldwell, Joseph Freda, and Lyle Goldstein, China’s Dreadnought? The PLA Navy’s Type 055 Cruiser and Its Implications for the Future Maritime Security Environment, China Maritime Report 5 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, February 2020).

China’s naval modernization, a process that has been underway in earnest for three decades, is now hitting its stride. The advent of the Type 055 cruiser firmly places the PLAN among the world’s very top naval services. This study, which draws upon a unique set of Chinese-language writings, offers the first comprehensive look at this new, large surface combatant. It reveals a ship that has a stealthy design, along with a potent and seemingly well-integrated sensor suite. With 112 VLS cells, moreover, China’s new cruiser represents a large magazine capacity increase over legacy surface combatants. Its lethality might also be augmented as new, cutting edge weaponry could later be added to the accommodating design. This vessel, therefore, provides very substantial naval capability to escort Chinese carrier groups, protect Beijing’s long sea lanes, and take Chinese naval diplomacy to an entirely new and daunting level. Even more significant perhaps, the Type 055 will markedly expand the range and firepower of the PLAN and this could substantially impact myriad potential conflict scenarios, from the Indian Ocean to the Korean Peninsula and many in between. This study of Type 055 development, moreover, does yield evidence that Chinese naval strategists are acutely aware of major dilemmas confronting the U.S. Navy surface fleet.

Conor M. Kennedy, Civil Transport in PLA Power Projection, China Maritime Report 4 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, December 2019).

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has ambitious goals for its power projection capabilities. Aside from preparing for the possibility of using force to resolve Beijing’s territorial claims in East Asia, it is also charged with protecting China’s expanding “overseas interests.” These national objectives require the PLA to be able to project significant combat power beyond China’s borders. To meet these needs, the PLA is building organic logistics support capabilities such as large naval auxiliaries and transport aircraft. But it is also turning to civilian enterprises to supply its transportation needs.

Ryan D. Martinson and Peter A. Dutton, China’s Distant-Ocean Survey Activities: Implications for U.S. National Security, China Maritime Report 3 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2018).

Today, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is investing in marine scientific research on a massive scale. This investment supports an oceanographic research agenda that is increasingly global in scope. One key indicator of this trend is the expanding operations of China’s oceanographic research fleet. On any given day, 5-10 Chinese “scientific research vessels” (科学考查船) may be found operating beyond Chinese jurisdictional waters, in strategically-important areas of the Indo-Pacific. Overshadowed by the dramatic growth in China’s naval footprint, their presence largely goes unnoticed. Yet the activities of these ships and the scientists and engineers they embark have major implications for U.S. national security. This report explores some of these implications. It seeks to answer basic questions about the out-of-area—or “distant-ocean” (远洋)—operations of China’s oceanographic research fleet. Who is organizing and conducting these operations? Where are they taking place? What do they entail? What are the national drivers animating investment in these activities?

Ryan D. Martinson, The Arming of China’s Maritime Frontier, China Maritime Report 2 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, June 2017).

China’s expansion in maritime East Asia has relied heavily on non-naval elements of sea power, above all white-hulled constabulary forces. This reflects a strategic decision. Coast guard vessels operating on the basis of routine administration and backed up by a powerful military can achieve many of China’s objectives without risking an armed clash, sullying China’s reputation, or provoking military intervention from outside powers. Among China’s many maritime agencies, two organizations particularly fit this bill: China Marine Surveillance (CMS) and China Fisheries Law Enforcement (FLE). With fleets comprising unarmed or lightly armed cutters crewed by civilian administrators, CMS and FLE could vigorously pursue China’s maritime claims while largely avoiding the costs and dangers associated with classic “gunboat diplomacy.”

Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson, China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA, China Maritime Report 1 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, March 2017).

Amid growing awareness that China’s Maritime Militia acts as a Third Sea Force which has been involved in international sea incidents, it is necessary for decision-makers who may face such contingencies to understand the Maritime Militia’s role in China’s armed forces. Chinese-language open sources reveal a tremendous amount about Maritime Militia activities, both in coordination with and independent of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Using well-documented evidence from the authors’ extensive open source research, this report seeks to clarify the Maritime Militia’s exact identity, organization, and connection to the PLA as a reserve force that plays a parallel and supporting role to the PLA. Despite being a separate component of China’s People’s Armed Forces (PAF), the militia are organized and commanded directly by the PLA’s local military commands. The militia’s status as a separate non-PLA force whose units act as “helpers of the PLA” (解放军的 助手) is further reflected in China’s practice of carrying out “joint military, law enforcement, and civilian [Navy-Maritime Law Enforcement-Maritime Militia] defense” (军警民联防). To more accurately capture the identity of the Maritime Militia, the authors propose referring to these irregular forces as the “People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia” (PAFMM).