The Ryan Martinson Bookshelf: Unique Insights on China’s Maritime Policies, Forces & Operations + Coast Guard Reform

For analysis of Chinese maritime policy and China Coast Guard development, it simply doesn’t get any better than this. Enjoy this fully updated one-stop library of my colleague Ryan Martinson’s work. It’s well worth reading all of these superb publications and interviews, even as they exceed three dozen in number!

Andrew S. Erickson, “The Ryan Martinson Bookshelf: Unique Insights on China’s Maritime Policies, Forces & Operations + Coast Guard Reform,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 2 February 2021.

Ryan D. Martinson is an Assistant Professor in the China Maritime Studies Institute of the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. The views represented in these articles are his alone, and do not reflect the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

PUBLICATIONS

Ryan D. Martinson, “Early Warning Brief: Introducing the ‘New, New’ China Coast Guard,” Jamestown China Brief, 25 January 2021.

Introduction

In the past decade, the China Coast Guard (CCG, 中国海警, zhongguo haijing) has experienced two major reforms. The first, which began in 2013, uprooted the service from the Ministry of Public Security—where it was organized as an element of the People’s Armed Police (PAP)—and placed it under the control of the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), a civilian agency. In the process, the CCG was combined with three other maritime law enforcement forces: China Marine Surveillance (CMS), China Fisheries Law Enforcement (CFLE), and the maritime anti-smuggling units of the General Administration of Customs. The resulting conglomerate was colloquially called the “new” CCG, differentiating it from the “old” CCG of the Ministry of Public Security years. The second reform began in 2018, when the “new” CCG, now swollen with the ranks of four different forces, was stripped from the SOA and transferred to the PAP, which itself had just been reorganized and placed under the Central Military Commission (CMC) (China Brief, April 24, 2018).

While much research has been done on the first reform, little is known about the second, at least in the English-speaking world. This article seeks to answer basic questions about the “new, new” CCG. What are its roles/missions, organization, and force structure? How does it differ from the CCG of the SOA years? How is it similar? What progress has been made two years after the second reform began?

The Roles and Missions of the (New, New) CCG

The “new, new” CCG has a dual identity. On the one hand, it is a component of China’s “armed forces” (武装力量, wuzhuang liliang). Its personnel wear camouflage working uniforms, are divided into officers and enlisted, seek promotion according to a system of ranks/grades, and operate vessels classified as “warships” (舰, jian). On the other hand, the CCG is also a domestic law enforcement force. It enforces Chinese criminal and administrative law in areas under its jurisdiction, which includes the mainland coast and all three million km2 of Chinese-claimed ocean space. Its law enforcement authorities were recently defined in the country’s first Coast Guard Law, which was adopted by the National People’s Congress (NPC) on January 22 and will be promulgated on February 1 (PRC Coast Guard Law, January 23).

The “new, new” CCG’s missions are basically unchanged from the SOA years (Xinhua, June 23, 2018):

- Fighting crime at sea

- Maintaining maritime security

- Supporting the development and exploitation of marine resources

- Protecting the marine environment

- Managing fisheries

- Suppressing maritime smuggling activities

Conspicuously absent is maritime search and rescue, which officially falls under the purview of other agencies—though in practice the CCG does conduct emergency rescue operations (Renminwang, December 27, 2019).

Together, these missions are defined as “rights protection law enforcement” (维权执法, weiquan zhifa). Indeed, this is the overarching purpose of the CCG. It is symbolized by one of three stripes on the PAP service flag (Xinhua, January 11, 2018) and codified in the recently-revised People’s Armed Police Law (PRC Ministry of Justice, June 20, 2020). Before 2018, “rights protection law enforcement” narrowly referred to efforts to defend China’s claimed maritime rights in the face of foreign encroachment. Today it encompasses everything the service does. [1]

During the SOA years, the CCG was China’s primary maritime law enforcement force operating in disputed space. This has not changed. Since 2018, the “new, new” CCG has spearheaded major sovereignty enforcement operations, especially in the South China Sea where it has buttressed Beijing’s unlawful claim to resource rights on the basis of the “nine-dash line.” It has escorted Chinese research vessels conducting seismic surveys in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone, along the line’s western boundary (AMTI, December 13, 2019); intimidated Malaysia for exploiting seabed resources in its own exclusive economic zone, near the line’s southeastern boundary (AMTI, November 25, 2020); and shepherded Chinese fishers as they trawled for fish in Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone, along the line’s southern boundary (The Jakarta Post, January 1, 2020).

But the “new” CCG was not, and the “new, new” CCG is not, the only Chinese maritime law enforcement force on the sovereignty beat. Local-level CMS and CFLE organizations—funded and managed by provincial and municipal governments—remained intact after 2013. The “new” CCG was charged with “guiding and coordinating” their activities (Government of the PRC, June 9, 2013), an arrangement that did not work well.[2] Local-level law CMS and CFLE units have thus far survived the second reform, their relationship with the CCG seemingly as ill-defined as ever (Xinhua, June 23, 2018), and they have retained their dozens of large, oceangoing cutters.

Some of these ships operate in disputed space. For example, from December 2019 to January 2020, the Yuzheng 45005—a 1,764 tonne(t) cutter operated by Guangxi CFLE—conducted a 57-day mission to the Spratly waters where it “safeguarded national maritime rights and interests and the security of the lives and property of Chinese fisher folk” (Guangxi Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, January 20, 2020) The circumstances of the mission suggest Yuzheng 45005 was among several cutters escorting Chinese fishers as they operated in waters northeast of Natuna Besar, where Indonesia’s EEZ boundary overlaps with the nine-dash line (The Jakarta Post, December 29, 2019). Local-level CFLE forces also help the CCG enforce China’s annual fishing moratorium. During the 2020 moratorium, the combined force “expelled” (驱离, quli) 1,138 foreign fishers from Chinese-claimed spaced, boarded 73 foreign fishing boats (impounding 11 of them), and detained 66 foreign fishers (Renminwang, September 28, 2020). … … …

Ryan D. Martinson, “Appendix I—The China Coast Guard: A Uniformed Armed Service,” in Michael A. McDevitt, China as a Twenty-First-Century Naval Power: Theory, Practice, and Implications (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2020), 187–206.

This appendix chronicles Beijing efforts to create a unified, capable maritime law enforcement agency.1 In his 18th Party Congress Work Report, Hu Jintao, then general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), identified four lines of effort that the country would pursue to transform China into a maritime power: raise the country’s capacity to exploit marine resources, develop its maritime economy, protect its marine environment, and safeguard maritime rights and interests. China’s maritime law enforcement (MLE) forces play an important role in each, and the most important of them is safeguarding China’s maritime rights and interests.2 The key point to keep in mind is that a world-class maritime rights protection force is an inextricable element in the march toward great maritime power.

Xi Jinping became general secretary of the CCP on November 15, 2012, and quickly turned his attention to semichaotic state of the maritime law enforcement institutions of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The organization now known as the China Coast Guard did not exist at the time. Instead, five different agencies, each with a narrow mission set, performed “coast guard–like” missions. These organizations, which scarcely communicated with each other, competed for funding, missions, and acclaim. This situation—described as “five dragons stirring up the sea”—led to waste, inefficiency, and disarray.3 None knew this better than Xi himself, who had witnessed it while serving as vice chair the of China’s Central Military Commission (CMC) and as leader of the CCP’s Maritime Rights Protection Leading Small Group, an entity that establishes policy.4 During 2012 he had observed the inauguration of a regular PRC constabulary presence established near the Senkaku Islands on the pretext that Tokyo had nationalized these disputed, barren rocks. In the South China Sea, China’s constabulary forces were also busy as the lead agencies in a several-month-long stand-off with Manila over Scarborough Shoal, a large, mostly submerged feature that both countries claim 140 nautical miles west of Subic Bay. Today, thanks to what took place in 2012, Beijing effectively controls Scarborough, by virtue of a continuous MLE presence. Both the Senkaku and Scarborough operations were successful assertions of Chinese sovereignty claims, but conducting simultaneous sovereignty campaigns in the East and South China Seas placed huge stresses on China’s maritime law enforcement forces. These stresses did not end when the campaigns ended; the agencies were subsequently tasked with maintaining permanent presences in the vicinity of these widely separated features.

Two weaknesses stood out. One was an organizational problem, the other that China’s maritime law enforcement forces lacked the ships they needed—especially large-displacement cutters—to maintain constabulary presence where and when necessary. The solution to the latter problem was straightforward: by the end of 2012 Chinese leaders had instructed the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy to transfer eleven auxiliary vessels to what would become the Chinese coast guard. They were painted white and sent to the “front lines.” At the same time, Beijing hastened production of several new classes of oceangoing patrol ships, the first step in what has turned out to be a sustained coast guard building program. As of this writing China has the world’s largest coast guard fleet, some 252 cutters and patrol craft, including the two largest cutters in the world, displacing some 12,000 tons. Approximately 115 of China cutters are large enough to conduct sustained patrols throughout China’s claimed waters. The addition of large harbors and docks on three of China’s man-made bases in the Spratlys (Subi, Mischief, and Fiery Cross Reefs) also increases Beijing’s ability to patrol routinely the farthest reaches of its South China Sea claims.5

Once he had assumed control of the civil side of the Chinese party-state by becoming president of the PRC, Xi took prompt action to remedy the organizational chaos as well. At that time maritime law enforcement and maritime rights protection were state, not party, functions. Coast guard reform was one of Xi’s first substantive actions, and in March 2013 the National People’s Congress (NPC) passed legislation to reconstitute the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), empowering it to oversee an amalgamation of four of the old “dragons.” The China Coast Guard was born four months later, on July 22, 2013.6 This marked the beginning of what turned out to be a long and difficult process to create a coast guard befitting a maritime power. If, however, China’s maritime law enforcement reform has encountered many difficulties, it has also achieved major improvements.7 … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Deciphering China’s ‘World Class’ Naval Ambitions,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (August 2020).

The Chinese Navy already routinely operates out of area, so its global aspirations should come as no surprise.

The scale and speed of China’s naval construction bear only one conclusion: Beijing is seeking to erode U.S. naval supremacy. This judgment requires no specialized knowledge of China or access to top secret intelligence. One need only look at the platforms the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is building and the pace at which it is building them.

But to fully understand the nature of the China maritime challenge, one must dig deeper—into the ideas guiding China’s naval development. This is far more difficult. The Chinese military is extremely cautious about revealing its true intentions. It produces lots of media content, but most of it is fluff. Analysts who spend their days sifting through Chinese sources failed to anticipate Beijing’s decision to build three enormous military facilities in the heart of the South China Sea. One day, China just began dredging sand and coral.

Still, many important things cannot be hidden. The service cannot build and shape a fighting force in secret. Major priorities must be communicated and inculcated. Soldiers, sailors, airmen, and rocketeers need to know what is asked of them and why it matters. By necessity, much of this happens in the open. The PLA can conceal plans to build bases; it cannot obscure broader aspirations.

The PLAN’s newest aspiration is to transform itself into a “world-class navy.” The idea of becoming “world class” was not a PLAN invention. Sometime in 2016, China’s head of state Xi Jinping told the PLA to transform itself into a world-class military. This injunction later appeared in Xi’s report at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, making it the official policy of the Chinese party-state.

The concept means different things for different services. For the PLAN, the clearest articulation appears in a speech delivered by PLAN Commander Vice Admiral Shen Jinlong shortly after the 19th Party Congress.1 The concept has what Admiral Shen calls three “essential features.” Two refer to key attributes of a world-class navy—global reach and command of the sea; the third highlights the process of getting there. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Counter-Intervention in Chinese Naval Strategy,” Journal of Strategic Studies, published online 27 March 2020.

The prospect of U.S. military involvement in a regional war looms large in Chinese naval strategy. This article examines the Chinese Navy’s evolving role in countering U.S. military intervention in a conflict over Chinese-claimed offshore islands. This role has both wartime and peacetime aspects. In peacetime, the PLA Navy serves a deterrence function, demonstrating China’s ability and resolve to fight the U.S. military if the U.S. were to intervene. In wartime, the operations of the PLA Navy would sit at the heart of any maritime campaign, helping to achieve China’s territorial objectives in spite of U.S. involvement.

Keywords: Naval strategy; Chinese navy; territorial disputes; counter-intervention; maritime strategy; U.S.-China relations

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “The Role of the Arctic in Chinese Naval Strategy,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief 19.22 (20 December 2019).

Introduction

In her recent China Brief article, Dr. Anne-Marie Brady examined the prospect of China deploying military power to the Arctic (China Brief, December 10). Applying the methods she used in her pathbreaking 2017 book, Brady draws from authoritative Chinese sources to demonstrate the growing importance of the Arctic in China’s strategic calculus. [1] She also cites a host of other indications that Beijing intends to send naval forces—especially submarines—north through the Bering Strait. Her research provides important context for an oracular 2019 U.S. Department of Defense claim that China could be laying the foundation for naval operations in the Arctic (Department of Defense, May 2).

Building on the excellent work done by Brady and others, this article argues that the available evidence allows for more categorical conclusions about China’s Arctic intentions. Specifically, the Chinese Navy has formally decided to incorporate Arctic ambitions into its naval strategy, and Chinese scientists and engineers are already conducting research to help it realize these ambitions.

From the Near Seas to the Two Poles

In China, “naval strategy” (海军战略, haijun zhanlüe) serves two key purposes. It defines the principles guiding how the fleet will be used today, and it outlines the plans for building the capabilities needed to meet the requirements of tomorrow. [2] China’s first official naval strategy dates to the mid-1980s, when the service’s chief preoccupation was restoration of Chinese-claimed islands (including Taiwan). Called “near seas defense” (近海防御, jinhai fangyu), it instructed the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to prepare to seize and maintain command of the sea in waters within the first island chain, a capability the PLAN already possessed vis-à-vis its weakest neighbors. It also catalogued the equipment and training needed to enable the service to achieve these wartime aims in scenarios involving more capable navies. [3]

By 2015, China’s naval strategy had officially changed to “near seas defense, far seas protection” (近海防御, 远海防卫/护卫 / jinhai fangyu, yuanhai fangwei/huwei). [4] The new strategy reflected trends that had been evident for years. The PLAN’s maritime defense mission remained preeminent. But the service was also increasingly tasked with operating in waters beyond East Asia, in the “far seas.” This began with an epochal 2008 decision to send successive task forces to counter Somali piracy in the Gulf of Aden, but soon extended to a whole range of other functions, often lumped under the rubric of “protecting overseas interests.”

The Arctic did not figure in either of these strategies. But we now know that it will in the next strategy. This fact was omitted from China’s 2018 White Paper on Arctic Policy (State Council Information Office, January 26, 2018) and its 2019 National Defense White Paper (State Council Information Office, July 24) —authoritative documents largely meant for foreign consumption. However, the political commissar of Dalian Naval Academy, Senior Captain Yu Wenbing (喻文兵), revealed the name of the next strategy in a July 2018 essay. Published in the PLAN’s official newspaper, Yu’s essay discussed his institute’s role in training and educating the leaders of the future navy. To provide context for his advocacy, he pointed out that the PLAN’s strategy was transitioning to a new concept: “near seas defense, far seas protection, oceanic presence, and expansion into the two poles” (近海防御, 远海防卫, 大洋存在, 两极拓展, jinhai fangyu, yuanhai fangwei, dayang cunzai, liangji tuozhan ). [5]

Senior Captain Yu did not indicate when this transition would be complete—but a more recent source does. In mid-2019, Ni Hua (倪华), a PLAN engineer posted to the Military Representative Office in Yichang City (Hubei Province) published an article about the need to boost China’s ability to counter the threats posed by foreign sea mines. Ni began by discussing the strategic concerns shaping China’s mine warfare needs. After citing the growing importance of the maritime domain to Chinese national security, he stated that “by 2030 the navy will…promote the construction and development of equipment according to the strategic requirements of ‘near seas defense, far seas protection, presence in the two oceans, expansion into the two poles.’” [6]

Most recently, the new strategic concept was broached during a presentation by Deng Aimin (邓爱民), Director of the Ship Development and Design Center of the 701 Research Institute, part of the state-owned China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation (CSIC). At an October 2019 event in Shenzhen, Deng spoke on the topic of China’s planned nuclear-powered icebreaker, which his team was designing. He offered some brief remarks on the strategic drivers behind his work: “Everyone should be fairly clear about our national strategy. One aspect is the strategic position of the poles. Another is expansion into the two poles…” [7]

Clearly, then, the PLA has decided that the next naval strategy will bring the service to the Arctic. Perhaps as a result of this decision, the PLA strategic studies community has grown increasingly candid about discussing the military’s future role in this new arena. For example, in a 2017 article, three analysts from the PLAN Submarine Academy examined the increasing out-of-area requirements of China’s submarine force. They argued, “China’s submarine forces must not only operate in the Pacific Ocean; they must also operate in the Indian Ocean. In the future, they must even operate in the Atlantic Ocean and the Arctic Ocean.” [8]

A more thorough treatment of this subject was published by PLAN Captain Zuo Pengfei (左鹏飞), a lecturer at China’s National Defense University. In his 2018 volume entitled A Study of Polar Strategy, Captain Zuo forthrightly discusses the military value of the Arctic to China and calls for deploying Chinese naval forces to the region. He writes, “As the world becomes hotter, the Arctic passages will increasingly become important areas for the operations of China’s maritime forces. Once [Chinese] forces normalize their presence in this region, they will not only be able to effectively pin down great powers like the U.S. and Russia; they will greatly reduce pressure from primary opponents in our other strategic directions.” [9]

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “China as an Atlantic Naval Power,” RUSI Journal 164.7 (18 December 2019).

China has shown an interest in extending its reach to the Atlantic Ocean.

China is in the process of becoming an Atlantic naval power, Ryan D. Martinson argues. Since 2014, the activities of the Chinese navy in the South Atlantic have evolved from port visits and largely symbolic joint exercises to independent operations at sea. This helps the Chinese navy to gain familiarity with the operating environment, so that it can effectively respond when called on by civilian leaders to protect China’s growing interests in the region. China’s increased naval presence in the South Atlantic may also reflect a shift in Beijing’s strategy for countering perceived threats from the U.S. military in the Western Pacific.

In recent years, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has dramatically expanded the geographic scope of its maritime operations. It has moved east, into the Western and Central Pacific. In 2007, the PLAN regularised training activities beyond the ‘first island chain’, the archipelagic barrier separating the China Seas from the wider Pacific.1 Today, Chinese warships routinely transit the Miyako Strait and Bashi Channel to conduct blue-water combat training in the Philippine Sea.2

The PLAN is also moving west, into the Indian Ocean. In December 2008, the PLAN’s first anti-piracy escort task force departed China for a four-month deployment to the Gulf of Aden. Since then, China has maintained a continuous naval presence in the northwest Indian Ocean. The original anti-piracy mission has evolved to include a broad set of non-combat roles, from friendly port visits to evacuating Chinese citizens from war-torn countries.

In little over a decade, the PLAN has transformed itself from a regional navy to a force with major presence out of area. This transformation is incomplete: there are strong indications that China intends to further bolster its sea power in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. But Beijing is also looking beyond the Indo-Pacific to other parts of the world where Chinese interests are concentrated.

This article examines the next frontier in Chinese naval expansion. It argues that, while the Northern Indian Ocean, and Western and Central Pacific Ocean will remain the primary geographic focus of Chinese sea power development, Beijing is preparing for future operations in the South Atlantic.

First, the article outlines the known facts of PLAN operations in the South Atlantic, including port visits, training and exercises, and other activities. It shows how PLAN activities have evolved since the service first arrived in the South Atlantic in 2014. It also highlights the role of Cape Town as a friendly port that Chinese naval forces rely on for shore- based support while operating in the South Atlantic. Second, it discusses the main drivers behind Beijing’s interest in the South Atlantic. It examines the growth in tangible Chinese interests, on shore and at sea, and explores the possibility that Beijing’s focus on the South Atlantic is intended, at least in part, to relieve US military pressure along China’s maritime periphery. … … …

***

Jessica Chen Weiss, “What China’s Assertiveness in the South China Sea Means—And What Comes Next,” The Monkey Cage, Washington Post, 30 May 2019.

China’s ‘maritime gray zone operations’ target U.S. naval vessels.

On Wednesday, General Joseph F. Dunford Jr., chairman of the Pentagon’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, remarked that despite assurances that there would be no moves to militarize the South China Sea, China had built “10,000-foot runways, ammunition storage facilities” — and routinely deployed aviation and missile defense capabilities. U.S. naval vessels operating in East Asia report being shadowed and harassed by China’s maritime forces. The Royal Australian Navy flagship Canberra also reported a recent encounter in the South China Sea while trailed by a Chinese warship: Its helicopter pilots were hit with lasers from what appeared to be fishing vessels.

To put these and other recent events in context, I reached out to two experts: Andrew S. Erickson, a professor at the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) and a visiting scholar at Harvard University’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, and Ryan D. Martinson, a researcher at CMSI. They are the editors of the book “China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations” (U.S. Naval Institute, 2019). What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation:

Jessica Chen Weiss: The trade war has dominated headlines in U.S.-China relations, but what’s the state of play between the United States and China in the South China Sea? How has China’s artificial enlargement of islands and reefs affected U.S. operations and interests?

Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson: While tariff disputes dominate world news, territorial disputes in the South China Sea remain a key flash point in U.S.-China relations. Beijing maintains a claim to all of the space within a “dashed line” enclosing most of the South China Sea — including hundreds of tiny islands and reefs. China also believes it has the right to engage in military, scientific and economic activity anywhere within this zone, and to limit at least some these same activities by other countries. Over the last decade or so, Beijing has vigorously asserted these claims. Instead of using its navy, it has relied on coast guard and maritime militia forces, operating in the “gray zone” between war and peace. … … …

***

Prashanth Parameswaran, “Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson on China and the Maritime Gray Zone,” The Diplomat, 14 May 2019.

How China thinks about and acts in the maritime gray zone, and what that means for the region’s future.

Over the past few years, as China has continued its expansion in the maritime domain, scholars and practitioners alike have honed in on the subject of how Beijing operates in the so-called “gray zone” between war and peace, staying below the threshold of armed conflict to secure gains while not provoking military responses by others, including the United States. Understanding the dynamics of this has important implications not only for particular maritime spaces, such as the East China Sea and the South China Sea, but also for broader issues such as the management of U.S.-China competition and wider regional peace and stability.

The Diplomat’s senior editor, Prashanth Parameswaran, recently spoke to Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson, both affiliated with the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute, about how China thinks about and acts in the maritime gray zone and what that might mean for the region’s future. The discussion was framed around the release of a new edited volume by the authors in March entitled China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations.

One of the core contributions of the book is providing a detailed and systematic understanding of how China itself thinks about the maritime gray zone – both on its own terms as well as how it related to broader Chinese foreign and defense policy – with a detailed use of Chinese sources. What are some of the key takeaways about how China thinks about the maritime gray zone in particular, in terms of how it is defined as well as the objectives and key components of China’s approach? And what would you flag as some of the areas of similarity and difference with respect to how others may think of these challenges and talk about them?

China is much more transparent in Chinese. And, particularly in native-language sources, Chinese policymakers are very clear about the fact that their long-term goal is to exercise “administrative control” over all of the 3 million square kilometers of Chinese-claimed maritime space. This includes all of the Bohai Gulf, large sections of the Yellow Sea and East China Sea, and all of the area within the nine-dash line in the South China Sea. Many Western analysts assume that China has more abstract aims, like discrediting the international legal order. This may happen anyway, as a byproduct of their actions, but the most compelling evidence suggests that Beijing sees strategic, economic, and symbolic value in controlling as much space as possible within the First Island Chain.

Chinese leaders don’t use the term “gray zone” to describe their approach to asserting control over this space. For at least a decade, they have conceived of their policy as a balancing act. On the one hand, they feel the need to defend and advance China’s claims. They call these actions “maritime rights protection.” On the other hand, they want to avoid severely harming their relations with other states. Regional stability, after all, is vital for sustaining China’s economic development — which remains the core of China’s grand strategy. Using paranaval forces like the coast guard and the militia allows them to find an optimal balance between “rights protection” and “stability maintenance.” Paranaval forces are much less provocative than gray-hulled warships. The Chinese coast guard operates on the pretext of routine law enforcement, and militia often pretend to be fishermen. Yet both forces can be used to pursue traditional military objectives of controlling space. … … …

***

Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 11 March 2019.

- Republished as “Interview: China’s Maritime ‘Gray Zone’ Operations,” The Maritime Executive, 2019.

On March 15th, the Naval Institute Press will publish China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations, a volume edited by professors Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson from the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. CIMSEC recently reached out to Erickson and Martinson about their latest work. … …

Q: The title of your book is China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations. How does the term “gray zone” apply here?

Martinson: We usually prefer to use Chinese concepts when talking about Chinese behavior, and Chinese strategist do not generally use the term “gray zone.” But we think that the concept nicely captures the essence of the Chinese approach. We were inspired by the important work done by RAND analyst Michael Mazarr, who contributed a chapter to the volume. In his view, gray zone strategies have three primary characteristics. They seek to alter the status quo. They do so gradually. And they employ “unconventional” elements of state power. Today, a large proportion of Chinese-claimed maritime space is controlled or contested by other countries. This is the status quo that Beijing seeks to alter. Its campaign to assert control over these areas has progressed over a number of years. Clearly, then, Chinese leaders are in no rush to achieve their objectives. And while China’s Navy plays a very important role in this strategy, it is not the chief protagonist.

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “China’s Far Seas Naval Operations, From the Year of the Snake to the Year of the Pig,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 18 February 2019.

Every year, about this time, the leaders of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) send their regards to Chinese sailors deployed overseas during the Lunar New Year. Every year these messages are covered by the Chinese press. Few in China pay attention to these reports. Fewer foreign observers even know of them, but they should. This annual ritual tells the story of China’s emergence as a global naval power.

***

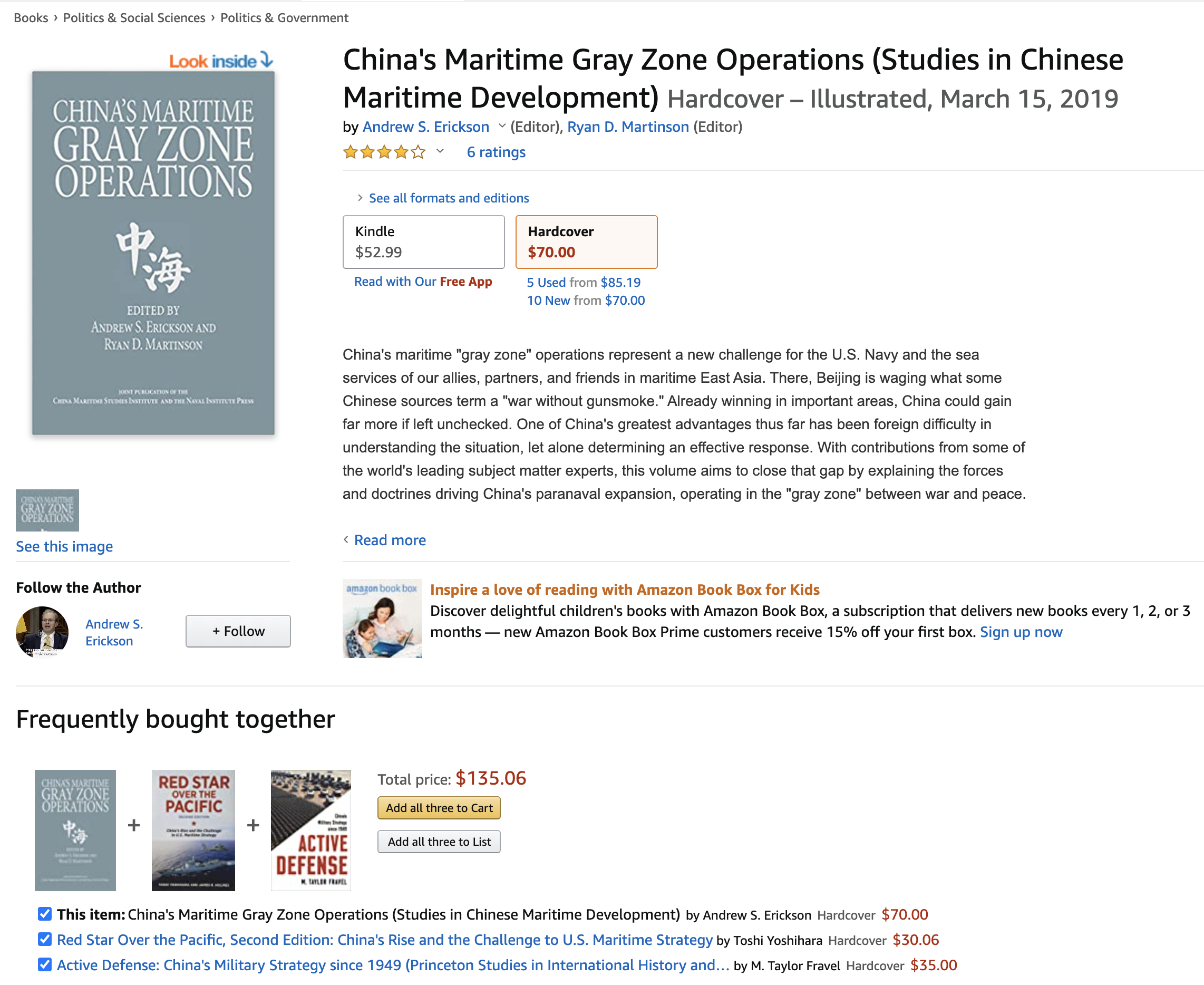

Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, eds., China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019).

- Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Introduction: ‘War Without Gun Smoke’—China’s Paranaval Challenge in the Maritime Gray Zone,” 1–11.

- Ryan D. Martinson, “Militarizing Coast Guard Operations in the Maritime Gray Zone,” 92–107.

- Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Conclusion: Options for the Definitive Use of U.S. Sea Power in the Gray Zone,” 291–301.

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Assessing the Future of Chinese Sea Power: Insights from the ‘Marine Science and Technology Award’,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief 19.2 (18 January 2019).

In late December, the Chinese press announced the 2018 winners of the “Marine Science and Technology Award” (MSTA), an annual prize recognizing China’s best work in oceanic research (China Ocean News, December 26 2018). For outside observers, the list of winners helps to identify pockets of excellence in Chinese marine science and technology. It also sheds light on Beijing’s current maritime intentions and future maritime capabilities—namely, where China is investing its resources, and which of its investments are panning out. Since 2016, award organizers have released limited information on winning “classified projects” (涉密项目), which are of special interest to those seeking to gauge China’s maritime ambitions. This article aggregates these data to identify the organizations and individuals at the forefront of strategically-important ocean research and development in China. It also explores how this information creates opportunities for more targeted analysis of individual Chinese maritime research projects. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson and Peter A. Dutton, China’s Distant-Ocean Survey Activities: Implications for U.S. National Security, China Maritime Report 3 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2018).

Today, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is investing in marine scientific research on a massive scale. This investment supports an oceanographic research agenda that is increasingly global in scope. One key indicator of this trend is the expanding operations of China’s oceanographic research fleet. On any given day, 5-10 Chinese “scientific research vessels” (科学考查船) may be found operating beyond Chinese jurisdictional waters, in strategically-important areas of the Indo-Pacific. Overshadowed by the dramatic growth in China’s naval footprint, their presence largely goes unnoticed. Yet the activities of these ships and the scientists and engineers they embark have major implications for U.S. national security. This report explores some of these implications. It seeks to answer basic questions about the out-of-area—or “distant-ocean” (远洋)—operations of China’s oceanographic research fleet. Who is organizing and conducting these operations? Where are they taking place? What do they entail? What are the national drivers animating investment in these activities? … … …

***

Ryan Martinson and Peter Dutton, “Chinese Scientists Want to Conduct Research in U.S. Waters—Should Washington Let Them?” The National Interest, 4 November 2018.

In recent years, Chinese scientists—and the government agencies that back them—have fixed their gaze on American waters, especially those near the U.S. territory of Guam. This has raised questions about the ability of current policy to adequately protect U.S. interests.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is not the only element of Chinese sea power plying the world’s great waterways. Today, Chinese oceanographic research vessels routinely operate in strategically important areas of the Indo-Pacific region. From the deck plates of China’s large (and still growing) fleet of survey ships, Chinese scientists are pursuing their research agendas in exotic new places: Madagascar, Micronesia, Benham Rise in the Philippine Sea, the Arabian Sea and the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone in the waters south of Hawaii.

The rapid expansion of China’s out-of-area—or “distant-ocean” (远洋)—oceanographic research operations raises important questions for Indo-Pacific nations. Many places of interest to Chinese oceanographers fall within the two hundred nautical mile exclusive economic zone of other countries. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) empowers coastal states to decide whether to allow marine scientific research (MSR) in their exclusive economic zones. Should they approve Chinese MSR? If so, under what conditions? What if Chinese scientists are not doing what they say they are doing? What are the risks of ignorance?

As an Indo-Pacific country and the state with the world’s largest exclusive economic zone, the United States faces these same questions. In recent years, Chinese scientists—and the government agencies that back them—have fixed their gaze on American waters, especially those near the U.S. territory of Guam. This has raised questions about the ability of current policy to adequately protect U.S. interests.

American policy has long been to make the waters of the U.S. exclusive economic zone open and available to the activities of foreign scientists. In many cases, it does not even require a permit or advance notice to undertake MSR. While this policy is admirable for its robust endorsement of maritime freedom, this approach leaves the United States vulnerable to exploitation by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a strategic competitor with an ocean agenda markedly different from our own. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, Echelon Defense: The Role of Sea Power in Chinese Maritime Dispute Strategy, Naval War College China Maritime Study 15 (February 2018).

This monograph examines China’s use of naval and coast guard forces to advance its maritime claims in the period since 2006. These include claims to sovereignty over dozens of land features, such as Scarborough Shoal. They also include rights to use and administer vast swaths of ocean that China claims on the basis of its particular interpretation of international law. Chinese leaders believe that the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) entitles them to jurisdictional rights over three million square kilometers of maritime space, often referred to as China’s “blue national territory” (蓝色国土). Nearly half of this space, Chinese leaders frequently lament, is contested by other states. To defend these “maritime rights,” Chinese ships are charged with a whole host of missions that often are conducted well out of sight of land.

Part 1 outlines China’s maritime claims, the value that Chinese leaders ascribe to them, and the overall objectives driving PRC policy. Part 2 looks at the naval and coast guard forces charged with defending and advancing these claims: their organizations, doctrines, and capabilities. Part 3 sketches the strategic context of China’s echelon defense approach. Part 4 zeroes in on the six major types of operations the Chinese coast guard and navy conduct in disputed areas. The monograph concludes with an accounting of PRC expansion over the ten-year period from 2006 to 2016, including key decisions that guided and enabled that expansion. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson and Katsuya Yamamoto, “How China’s Navy Is Preparing to Fight in the ‘Far Seas’,” The National Interest, 18 July 2017.

Two PLA Navy officers might have a clue.

On June 28, the Chinese navy launched the first of a formidable new class of warship. At over twelve thousand tons and bristling with sensors and weapons, the Type 055 destroyer is among the most advanced surface combatants in the world. When completed, it will join the world’s fastest-growing fleet, a service that commissioned twenty-three new surface ships in 2016 alone, compared with just six for the U.S. Navy and zero for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force. Clearly some great fear or ambition hastens China’s investment in sea power.

But what is it?

Unfortunately, Beijing is saying very little. And what it does say is unconvincing. For example, PLA Navy officer Zhang Junshe (张军社) claims the Type 055 will protect international sea lanes, upon which the Chinese economy is increasingly dependent, but does not name which country or group threatens them in the first place. He tells us the ship will help fulfill China’s “international responsibilities” (国际责任) and provide “public security goods” (公共安全产品), but these are just meaningless buzzwords that foreigners use—surely they have no purchase in the halls of Zhongnanhai. He suggests the new warship will operate with Chinese aircraft carriers, but where and for what ends, he does not say.

Faced with a lack of reliable information, much foreign analysis of Chinese intentions ultimately rests on a few facts and lots of speculation. Our understanding of Beijing’s designs in waters beyond East Asia—the so-called “Far Seas”—is especially poor. Thus, when candid statements do become available, they deserve careful consideration. In mid-2016, a PLA Navy periodical called Naval Affairs (海军军事学术) published an article that may help shed light on China’s Far Seas naval ambitions. Because Naval Affairs is an “internal distribution” publication—that is, only available to those within the Chinese military—it treats subjects with the rarest of candor. As such, if offers a valuable window into how the PLA Navy actually thinks about strategy.

Entitled “Several Issues China Must Emphasize as it Strategically Manages the Two Oceans Under the New Situation,” the article was written by two PLA Navy officers, both researchers at the Naval Research Institute, the home of Chinese naval strategy. The first author, Lt. Cdr. Tang Jianfeng (唐剑峰), is a staff officer in NRI’s Research Guidance Department. His coauthor is Cdr. Yang Zukui (杨祖快), Deputy Director of NRI’s Research Office. Tang and Yang are mid-level strategists writing about what China’s naval strategy should be, not necessarily what it is. However, their analysis is informed by privileged knowledge of PLA Navy doctrine, existing and planned capabilities, and the aims and preferences of their superiors, whom they naturally seek to please. What does it say? … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson and Katsuya Yamamoto, “Three PLAN Officers May Have Just Revealed What China Wants in the South China Sea,” The National Interest, 9 July 2017.

Chinese strategy in the South China Sea is expansionary in aim, incremental by design and realist in orientation.

Earlier this year, Kyodo News published a tantalizing summary of a Chinese article that seemed to offer rare insights into Beijing’s intentions in the South China Sea. Unfortunately, Kyodo’s report was too vague to be fully appreciated, or long-remembered. We have tracked down the original. It is well worth a closer look.

The article comes from a special class of periodical published by the Chinese military for “internal distribution.” These are not classified documents per se. Rather, they are teaching materials and scholarly works written for a select audience. Due to this restricted access, these works are both candid and extremely authoritative. As such, they offer invaluable insights into the thinking of the Chinese military and party-state.

This particular article was printed in a mid-2016 issue of Naval Studies (海军军事学术), one of the most important “internal distribution” periodicals on maritime affairs in China. Run by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Naval Research Institute, it is a bimonthly scholarly journal that delves into a range of topics on naval strategy.

The article is titled “Military Crises in the South China Sea: Analysis, Assessment, and Responses.” It was written by three Chinese naval officers: Lt. Comm. Jin Jing, a researcher at the Naval Research Institute, and Commanders Xu Hui and Wang Ning, both political officers from the PLA Navy South Sea Fleet. We assume that analysis published by these three mid-level officers in this forum is orthodox, honest and very well-informed. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, The Arming of China’s Maritime Frontier, China Maritime Report 2 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, June 2017).

China’s expansion in maritime East Asia has relied heavily on non-naval elements of sea power, above all white-hulled constabulary forces. This reflects a strategic decision. Coast guard vessels operating on the basis of routine administration and backed up by a powerful military can achieve many of China’s objectives without risking an armed clash, sullying China’s reputation, or provoking military intervention from outside powers.

Among China’s many maritime agencies, two organizations particularly fit this bill: China Marine Surveillance (CMS) and China Fisheries Law Enforcement (FLE). With fleets comprising unarmed or lightly armed cutters crewed by civilian administrators, CMS and FLE could vigorously pursue China’s maritime claims while largely avoiding the costs and dangers associated with classic “gunboat diplomacy.”

This same logic argued against employing the armed elements of its maritime law enforcement forces, the China Maritime Police (CMP). Though the CMP had the authority and ability to operate throughout the three million square kilometers of China’s claimed jurisdictional space, Chinese leaders elected to keep this service away from disputed and sensitive areas. Its identity as a military organization contradicted key premises of China’s maritime dispute strategy.

Since 2013, these assumptions have changed. In that year, Chinese leaders began a major restructuring of the country’s fragmented and dysfunctional maritime law enforcement system, derisively described as “five dragons managing the sea” (五龙制海). This reform sought to “integrate” four Chinese maritime law enforcement forces—the three “dragons” mentioned above, plus a fourth force owned by the General Administration of Customs (GAC)—into a new agency called the “China Coast Guard.” While organizational change has been slow, one outcome is clear: the reform has empowered the armed elements of China’s constabulary forces to play an increasingly important role along China’s maritime frontier.1 This reflects a subtle but significant shift in Chinese policy, with possible implications both for future PRC behavior and the future of the China Coast Guard as an organization. … … …

***

James E. Fanell and Ryan D. Martinson, “Countering Chinese Expansion through Mass Enlightenment,” Center for International Maritime Security, 18 October 2016.

From Newport to New Delhi, a tremendous effort is currently underway to document and analyze China’s pursuit of maritime power. Led by experts in think tanks and academia, this enterprise has produced a rich body of scholarship in a very short period of time. However, even at its very best, this research is incomplete—for it rests on a gross ignorance of Chinese activities at sea.

This ignorance cannot be faulted. The movements of Chinese naval, coast guard, and militia forces are generally kept secret, and the vast emptiness of the ocean means that much of what takes place there goes unseen. Observers can only be expected to seek answers from the data that is available.

The U.S. Navy exists to know the answers to these secrets, to track human behavior on, above, and below the sea. While military and civilian leaders will always remain its first patron, there is much that USN intelligence can and should do to provide the raw materials needed for open source researchers to more fully grasp the nature of China’s nautical ambitions. Doing so would not only improve the quality of scholarship and elevate the public debate, it would also go a long way to help frustrate China’s current—and, to date, unanswered—strategy of quiet expansion. Most importantly, sharing information about the movements and activities of Chinese forces could be done without compromising the secrecy of the sources and methods used to collect it. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “The Scholar as Portent of Chinese Actions in the South China Sea,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 25 July 2016.

Chinese leaders, like leaders elsewhere, rely on the advice of outside experts—academics and other professional scholars—to help them cope with the myriad challenges of international politics. Statesmen and scholars, however, come from very different worlds. When leaders craft foreign policy, they place a premium on secrecy. Scholars, by contrast, have powerful motives to share their views and tout their influence.

For those studying an opaque state like the People’s Republic of China (PRC), it is therefore very tempting to regard the “influential” Chinese scholar, who writes and speaks without reserve, as a proxy for the shy statesman he serves. The lure of this approach is especially strong in the case of the South China Sea, where authoritative—and reliable—statements of PRC intentions are particularly scarce. In the aftermath of the recent ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (Case No. 2013-19), the writings of Chinese scholars will no doubt be closely scrutinized for insights about the PRC’s likely response to this desolating blow to its South China Sea claims.

But is this a wise approach?

We must immediately distinguish the advisor from the propagandist. Both have direct connections with the state. Indeed, an individual scholar may serve both functions. As a propagandist, the scholar justifies past and current policy; as an advisor, she seeks to shape future policy. Studying the work of the propagandist has merits: we learn what the PRC wants domestic and international audiences to believe. The statements of the advisor, however, are potentially much more rewarding, for they may suggest future actions. Knowing what a state may do allows one to engage in proactive diplomacy and prepare countermeasures.

Given the legal and strategic complexities of the issues at stake, Chinese scholars have an important advisory role to play in South China Sea policy. However, among the dozens (hundreds?) of Chinese scholars researching the law and politics of the South China Sea, the vast majority will never speak to or have their work read by men and women in positions of real authority. Thus, if one’s aim is to conjecture about the direction of PRC policy, the works of only a tiny number of Chinese scholars—i.e., those with demonstrable influence—are worth considering.

Researchers at the Hainan Center for South China Sea Policy and Law (海南省南海政策与法律研究中心) fall into this category. Examining this institute—and the work of one scholar in particular—allows us to explore what can and cannot be learned from the writings of “influential” Chinese scholars. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Panning for Gold: Assessing Chinese Maritime Strategy from Primary Sources,” Naval War College Review 69.3 (Summer 2016): 23–44.

What are the drivers behind China’s vigorous pursuit of sea power? What are the interests Beijing seeks to advance by building a powerful bluewater navy and the world’s largest coast guard? What are the principles that guide its use of sea power in pursuit of its national interest? How are China’s state objectives, and approaches to pursuing them, evolving over time?

The answers to these questions are of obvious concern both to the states along China’s maritime periphery, many of which are party to maritime disputes with Beijing, and to external powers with major interests in East Asia, such as the United States. Increasingly, Chinese actions have important implications for other parts of the watery world, such as the Indian Ocean region, where China has maintained a constant naval presence since late 2008.1

Those seeking to gauge and define Chinese policy must be willing and able to draw on all available sources of information. Most fail to do so. The vast majority of analyses of China’s maritime strategy focus almost entirely on Chinese behavior: what it has done, what it has built. In particular, most highlight a small number of events or cases from which they draw conclusions about Chinese strategy.

To be sure, Chinese actions are the best indicators of Chinese strategy. They reveal exactly what Chinese policy makers are willing to do. They provide raw data that cannot be manipulated. However, the specific drivers of a given behavior are often open to interpretation. Some analysts, for example, assume that Chinese actions in the “near seas” of East Asia are a product of a carefully designed and implemented national strategy, with head and arms working in perfect coordination. However, were these analysts familiar with the breadth of Chinese writings lamenting the country’s lack of well-defined ends, ways, and means, they might revise this proposition. While strategy is surely involved, Chinese mariners probably are not acting out a detailed script for regional dominance.2 Moreover, a particular action may be the result of local initiative, or later may be judged a mistake, in which case it may not portend future behavior. The 2009 Impeccable incident, discussed below, may be a case in point.

Judicious use of authoritative statements about Chinese maritime strategy can validate and enrich assessments made on the basis of observed behavior, ameliorating the problems described above. Many of those who research and write on contemporary maritime issues, however, are not fully aware of the potential value of original Chinese documents. Moreover, those who are aware often disagree, sometimes fiercely, about which sources are most useful.3 This problem is exacerbated by the tremendous proliferation of Chinese documents in recent years, a challenge that has aptly been called “a poverty of riches.”4

This article seeks to describe the range of sources available for helping to understand Chinese maritime strategy and to assess their relative value. It comprises five parts. Part 1 outlines basic assumptions and defines key terminology. The subsequent three parts examine three distinct categories of sources, grouped according to the role of the author or speaker: those who formulate Chinese maritime strategy, those who implement the strategy, and the scholars and pundits who define and influence it. The article concludes by offering a set of general rules for assessing the value of Chinese sources on maritime strategy.

The primary aim of this article is to identify specific individuals and their affiliations and draw conclusions about why their statements may (or may not) shed light on Chinese maritime strategy. For illustration purposes, the article will offer examples of the type of information that may be gleaned from close reading of those sources. It does not, however, seek to define Chinese maritime strategy comprehensively, per se. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “The Courage to Fight and Win: The PLA Cultivates Xuexing for the Wars of the Future,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief 16.9, 1 June 2016.

With all its new weapons systems and platforms, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has become a powerful military by any standard that can be quantified. But how will PLA officers and enlisted, however well-armed, perform when faced in combat by a capable adversary? China’s civilian and military leaders are not optimistic.

Since early 2013, the PLA has conducted a political campaign to cultivate xuexing (血性)—courage, or valor—in its soldier, sailors, and airmen. Prompted by instructions from Xi Jinping, this campaign has sought to ensure that the services exhibit the aggressiveness needed to defeat a powerful adversary. It was initiated due to a perceived lack of warrior spirit in the military. The PLA seeks to rectify inadequacies by changing service culture through political work and training. Understanding this effort sheds light on how Chinese leaders gauge the balance of power between China and potential foes. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Shepherds of the South Seas,” Survival 58.3 (2016): 187–212.

On 21 July 2014, a Chinese law-enforcement ship, YZ 32501, arrived at its home port in Nantong, Jiangsu. As its crew disembarked, they were received by a senior officer from the China Coast Guard, who had travelled from Shanghai for the event. He thanked them for their 80 days of ‘continuous combat’ in the South China Sea.

Eighty days was a long deployment for a ship of this size (just 500 tonnes). Indeed, the vessel had no obvious mandate to operate in the South China Sea: its primary mission is to manage fisheries in areas under the jurisdiction of Jiangsu province, far to the north. But it had been urgently pressed into action in remote waters – and not to protect fish.1

During its weeks in the South China Sea, YZ 32501 conducted a type of operation called huhang, or ‘escort’. Traditionally, escort missions are performed by naval forces. British, Canadian and American surface combatants, for instance, escorted merchant ships across the North Atlantic during the Second World War, protecting them from the depredations of German submarines. The warships of numerous countries, including China, shepherd civilian vessels transiting through the Gulf of Aden, protecting them from Somali pirates.

However, unarmed or lightly armed Chinese maritime law-enforcement ships also perform escort missions. Their flocks are not vessels using the ocean as an avenue of transportation, but ships and platforms seeking to exploit it as a source of economic wealth.2 These include Chinese fishing trawlers, seismic-survey ships and, in the case of YZ 32501, a billion-dollar drilling rig named Haiyang Shiyou (HYSY) 981. These operations, which largely take place in the South China Sea, are an integral, but under-studied, part of China’s strategy to advance the country’s position in its maritime disputes. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “The 13th Five-Year Plan: A New Chapter in China’s Maritime Transformation,” Jamestown China Brief, 12 January 2016.

During the past three decades, China has experienced a tremendous transformation in its strategic outlook. It has evolved from a terracentric state with its military, political, economic, and cultural roots firmly planted on the Eurasian continent to one of the world’s premier maritime states. The blueprints for this transformation can be found in the pages of the party-state’s “Five-Year Plans for Economic and Social Development” (FYPs). In March 2016, China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) will approve the 13th FYP (2016–2020). As is the custom, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) issued a “proposed” (建议) version of the 13th FYP at the autumn plenary meeting of the Central Committee. A close reading of this document suggests that the next FYP will embody maritime aspirations that are increasingly global in scale and scope. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Deciphering China’s Armed Intrusion Near the Senkaku Islands,” The Diplomat, 11 January 2016.

The appearance of an armed Coast Guard ship gives Japanese authorities plenty to ponder.

How to interpret the late-December appearance of an “armed” China Coast Guard ship near the Senkaku (a.k.a. Diaoyu) Islands?

The two tiny turrets fore and aft are not the story. Other Chinese vessels have sailed these waters with deck guns. Japanese ships operating here are, of course, armed. And in any case, the use – or threat – of force is inimical to the chief aim of China’s Senkaku Island patrols: i.e., to “demonstrate” Chinese sovereignty without risking military conflict. Acts of aggression, when they do occur in these waters, usually involve threatening others with collision, in which case the ship itself is the instrument of coercion.

With these facts in mind, what can we say about our armed intruder? CCG 31239, or Zhongguo Haijing 31239, was originally built for the PLA Navy, where she served for over 20 years. In the summer of 2015, the vessel was transferred, along with two other ships of her class, to the China Coast Guard – specifically, the agency’s Shanghai “contingent” (zongdui). That CCG 31239 was once a naval vessel does not make her unique. China’s maritime law enforcement fleet has a number of former PLA Navy ships. Several, indeed, have sailed to the Senkakus. But those were all former auxiliary vessels: tug boats, submarine rescue ships, and icebreakers.

CCG 31239 was a frigate. Therefore, by China Coast Guard standards she is very fast. Moreover, she was built to naval specifications: her designers presumably intended her to survive cannon and even missile fire, as warships must in wartime. China Coast Guard ships built from the keel up are not expected to meet the same standards of survivability. All this means that CCG 31239 is much better prepared to prevail in any game of chicken that might take place in these waters. Moreover, CCG 31239 is no doubt equipped with advanced sensors and communications equipment, certainly superior to the commercial-grade hardware usually installed on other China Coast Guard vessels. CCG 31239 will thus improve maritime domain awareness in the waters where she operates.

Yet CCG 31129’s most noteworthy attribute may be her crew. The vessel is operated by a special class of Chinese coastguardsmen. In fact, they are China’s “original” coastguardsmen. Recall that before the creation of the China Coast Guard in mid-2013, Beijing funded many different maritime law enforcement agencies. Those that mattered most to China’s neighbors were China Marine Surveillance (CMS) and Fisheries Law Enforcement (FLE). They were the only organizations that regularly sent ships to the Senkakus, Scarborough Shoal, and the Spratlys. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “China’s Great Balancing Act Unfolds: Enforcing Maritime Rights vs. Stability,” The National Interest, 11 September 2015.

Chinese leaders are torn by two conflicting goals: The desire to regain “lost” islands and waters and a need to maintain stable relations with neighbors and America.

During a July 2015 television news show, Renmin University professor Shi Yinhong was asked to define China’s strategy in the South China Sea. After first declining to answer the question—“I can’t tell this to outsiders. I can’t tell you.”—the raspy-voiced professor quickly found a compromise between discretion and the academic’s inherent need to expatiate. With fellow guest, naval analyst Li Jie, nodding on, Shi described China’s strategy in four characters: 步步为营 (bubu weiying): “Building fortifications after each new advance.”

Professor Shi’s image of an army on the march, carefully consolidating its position after new territory is gained, is only the latest in a long line of metaphors used to depict China’s recent expansion in maritime East Asia. Most are products of American minds. They range from the sartorial to the salacious. Some, like “salami slicing,” are standard terms used by political scientists for decades. Many will doubtless serve as fodder for future scholars seeking to understand both the observers and the observed.

Almost all of these metaphors are descriptive. That is, they are largely based on analysis of patterns of behavior. As such, they shed little light on how Chinese policymakers may actually think about their options. To understand that, one must begin by recognizing the colossal contradiction that sits at the heart of China’s approach to its maritime disputes. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “From Words to Actions: The Creation of the China Coast Guard,” a paper for the China as a “Maritime Power” Conference, CNA Corporation, Arlington, VA, 28–29 July 2015.

Hu Jintao’s 18th Party Congress Work Report spawned a thousand essays to interpret and expound on the “maritime power” (haiyang qiangguo) concept. What did it mean to be a maritime power? What were the standards for judging success and failure? What policies would be needed to achieve these objectives? What were the biggest challenges, and how might they be overcome? In this discussion, which continues to the present, one thing was clear: Becoming a maritime power would require a comprehensive effort from multiple agencies, departments, and services.

At that time, arguably the most important contributor to the success of the “maritime power” endeavor was China’s maritime law enforcement (MLE) forces. They helped regulate the maritime economy; they deterred and punished environmentally destructive economic behavior; and they performed missions to “safeguard maritime rights and interests,” a function that came to the foreground in the turbulent year of 2012.

Yet despite the vital part played by China’s constabulary forces, there were severe problems with the country’s maritime law enforcement system. Each of the five departments responsible for overseeing activities that in any way involved the sea funded its own maritime law enforcement force. Therefore, China’s claimed 3 million square kilometers of jurisdictional waters, 32,000 kilometers of coastline, and 6,000 land features were administered by several different agencies.

This led to waste, inefficiency, and disarray, a situation summed up by the phrase wulong naohai—five dragons stirring up the sea.1

Soon after the 18th Party Congress, State Oceanic Administration (SOA) Director Liu Cigui published an article in which he outlined his understanding of the new concept. To become a maritime power, China would need to “establish maritime administration and maritime law enforcement systems that are authoritative and highly efficient, have fairly concentrated functions, and have uniform responsibilities; that can perform overall planning for both internally oriented administrative law enforcement and externally oriented rights protection law enforcement; and that can provide organizational support for efforts to build China into a maritime power.”2 That is, the five dragon model would have to go.

Liu’s vision was not novel. People both inside and outside government had been calling for maritime law enforcement reform for at least 10 years. It made eminent sense—although, given the bureaucratic interests involved and the scale of the project, it would be both difficult to initiate and difficult to implement. Despite the anticipated difficulties, however, it was only a few months after the 18th Party Congress that Chinese policymakers took a major first step towards building a new system. In March 2013, the National People’s Congress (NPC) passed legislation to re-constitute SOA, empowering it to oversee an entirely new maritime law enforcement entity, to be called the China Coast Guard Bureau (zhongguo haijingju).

***

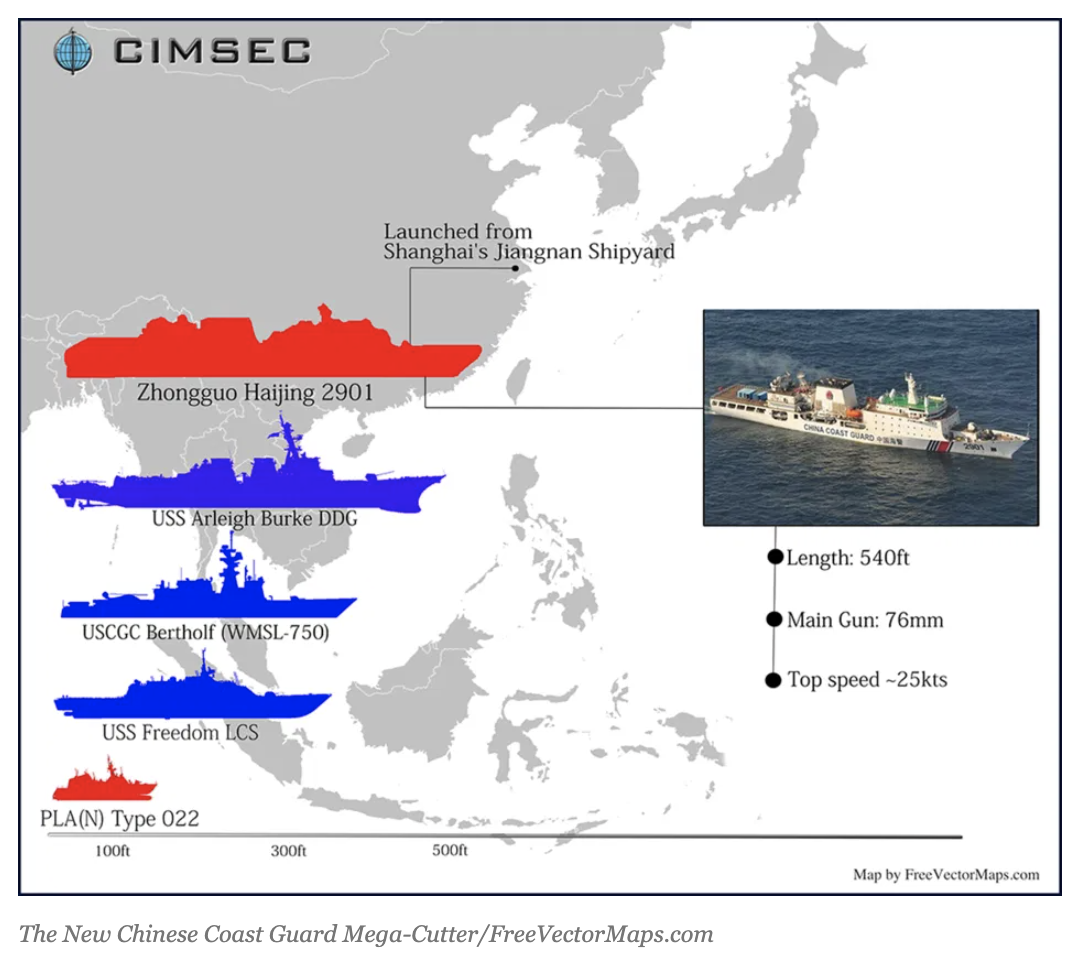

Ryan D. Martinson, “East Asian Security in the Age of the Chinese Mega-Cutter,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 3 July 2015.

On May 19th, a formidable new Chinese ship put to sea for the first time. As it left its berth at Jiangnan Shipyard, its onboard automatic identification system (AIS) transmitted signals for anyone who cared to receive them. Its identity, Zhongguo Haijing 2901. Its purpose, sea trials. Its heading, somewhere in the East China Sea.

This was not the voyage of the Red October. Zhongguo Haijing 2901 is not a stealthy nuclear submarine able to menace foreign capitals, or sink foreign fleets. Nor is it a sister ship to China’s Liaoning (CV-16), that other potent symbol of sea power, the aircraft carrier. Indeed, by naval standards, its combat capabilities belong to an earlier age—the 19th century.

However, Zhongguo Haijing, or China Coast Guard (CCG) 2901, was not built to fight wars. At over 10,000 metric tons, it is by far the world’s largest constabulary vessel, a class of ship operating at the vanguard of China’s peacetime expansion in maritime East Asia. When it is commissioned sometime in the coming weeks, it will provide a huge advantage to China in the battle of wills taking place along its maritime periphery. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “China’s Second Navy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 141.4 (April 2015).

While the world has been busy watching China’s blue-water naval buildup, the People’s Republic has been steadily exploiting maritime law enforcement—and its coast guard—as an instrument of statecraft.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is in the midst of a major, much-publicized augmentation of its maritime law-enforcement forces. The familiar lamentations among Chinese navalists—our law-enforcement ships are small and few; we can’t compare with other great powers—have been replaced by quiet recognition that China now possesses the world’s largest blue-water coast guard fleet. Were this simply an effort to enhance the PRC’s ability to enforce uncontroversial domestic law in uncontested waters, few would notice. But outside observers have seen a noteworthy pattern in China’s behavior: It uses the law-enforcement cutter as an instrument of foreign policy.

Despite frequent comment on Chinese expansion in maritime East Asia, there is a shocking dearth of scholarship on this topic. Foreign observers generally agree that by deploying unarmed coast guard ships—white hulls—to pursue interests, China is able to leverage its growing power while avoiding international opprobrium detrimental to other foreign-policy goals. However, there is little systematic discussion of what roles China’s maritime law-enforcement forces perform in their capacity as instruments of policy. This article will take a first step toward filling this gap. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Reality Check: China’s Military Power Threatens America,” The National Interest, 4 March 2015.

The U.S. can’t just wish away China’s A2/AD capabilities.

In their writings on China’s military modernization, too many commentators fail to ground their views in the available sources. In most cases, this practice does no more than discredit the author, or the publication that gives him a forum; but when analysts responsible for writing national assessments are unversed in original writings, the consequences may be far graver.

In a recent Washington Quarterly article, M. Taylor Fravel and Christopher Twomey spotlight the more baleful side of this tendency, taking aim at influential American analysts who write unlearned perspectives about Chinese intentions towards the United States.

The paper’s title—“Projecting Strategy: The Myth of Chinese Counter-Intervention”—captures its thesis. Fravel and Twomey claim that in recent years the U.S. national security community has repeatedly mischaracterized China’s likely response to American intervention in a regional conflict involving China, ascribing aggressive designs where none exist. This practice, the authors believe, has given rise to a conventional wisdom that is harmful to bilateral relations.

To be sure, Fravel and Twomey are on solid ground when they expose those who claim that “counter-intervention” is a term used frequently in Chinese texts. But this error can be set straight in a footnote, certainly no more than a single sentence. Perhaps as simple as this: Authoritative Chinese sources seldom use the term “counter intervention,” or anything resembling it, except when discussing foreign imputations of Chinese strategy.

The two professors, however, go much further than this harmlessly pedantic “word to the wise.” They posit that the absence of this concept means that the ideas that “counter-intervention” embodies—deterring or denying America access during a regional conflict—do not figure into Chinese military planning. Since Chinese texts offer no direct proof of a counter-intervention strategy, those who assume one exists must be imagining it. Thus, with their sloppy attributions, American analysts are guilty of exaggerating the Chinese threat.

However, one need not achieve mastery of the available Chinese texts, or suffer from cognitive defects, to conclude that China almost certainly has a military strategy that accounts for American intervention in a regional war. Here is the train of reasoning. China is a party to many disputes with its neighbors, some of which are American treaty allies (Japan, the Philippines), and one of which America has vowed to defend if attacked (Taiwan). These disputes involve claims of sovereignty over offshore islands and jurisdiction over maritime zones, which China believes constitute “core interests,” especially in the case of Taiwan.

Should one of these lead to war, the U.S. is very likely to enter the conflict: it has shown its willingness to do so in the past, both in word and deed. American statesmen command the most powerful military in the world; its capacity to project power from and on the sea is unparalleled. Conclusion: China has a tremendous incentive to build systems—and develop plans for using them—that enable it to undermine America’s ability to intervene. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Jinglue Haiyang: The Naval Implications of Xi Jinping’s New Strategic Concept,” Jamestown China Brief (9 January 2015).

In studies of Chinese expansion in the near seas of East Asia, one topic that has been almost entirely ignored is the concept of jinglue haiyang, recently endorsed by the Party-state as a facet of China’s maritime power strategy. The word jinglue is not in common usage; indeed, most dictionaries do not define it. It is a verb combining jing, the character for manage or administer, with lue, the character for strategy or stratagem. According to the 1979 edition of the Cihai Dictionary, it means “handling an issue on the basis of prior planning.” A useable translation might be “strategically manage,” with the full phrase rendered as “strategic management of the sea.”

Chinese official and quasi-official sources, the naval press in particular, now regularly cite this new concept, often identifying it as a cornerstone of Chinese President and Commander-in-Chief Xi Jinping’s strategic thought. Given the exoticism of the term and its obvious importance for understanding Chinese maritime strategy, it is worth examining in greater detail. A close reading of Chinese texts suggests that the concept favors an expansive view on the use of sea power in peacetime, perhaps shedding light on the current leadership’s apparent preference for a more active and systematic pursuit of maritime dominance, especially in the waters of the South China Sea. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “Chinese Maritime Activism: Strategy Or Vagary?” The Diplomat, 18 December 2014.

A new study questions the conventional wisdom of a coordinated national strategy.

Everybody who meditates on Chinese foreign policy has a theory of how China functions. This is only human: the mind needs to make sense of all the information. The best analysts constantly reassess their theories in light of new data. In her recent Lowy Institute study, Linda Jakobson presents the English-speaking world with lots of new data – and a new theory to go with them.

It is generally accepted, at least in the United States, that China’s recent activism in the near seas of East Asia is a product of a coordinated national strategy. From Scarborough Shoal to HYSY 981, the goal is quiet expansion. Jakobson questions the conventional wisdom, making a case for ungoverned local initiative – buoyed by surging national power – as the primary factor driving events at sea. Although, at least in this reader’s view, Jacobson does not ultimately clinch the case, her paper is a valuable addition to the scholarship on China’s rise.

Jakobson profiles all of China’s major actors in the maritime sphere, from the highest policymaking bodies to the outspoken ranks of PLA propagandists. Above all, she focuses on China’s maritime law enforcement agencies, a natural choice given that if a strategy does exist they would be the primary instruments with which it would be implemented. In particular, she looks at the recently created China Coast Guard, suggesting a reform encountering stiff headwinds, a case that she makes with great persuasiveness. Jakobson puts a microscope on the agents of Chinese maritime policy, unearthing the details of their political ecosystem from dozens of texts and interviews with Chinese scholars and officials. Her research is a much needed corrective to simplistic views of China as a state able to identify an objective many years in advance and pursue it with anthropomorphic cunning. … … …

***

Ryan D. Martinson, “The Militarization of China’s Coast Guard,” The Diplomat, 21 November 2014.

Plans for China’s still nascent coast guard suggest troubled times ahead in disputed waters.

With new “China Coast Guard” ships entering service at regular intervals, it is easy to forget that the China Coast Guard as an organization does not yet exist in any complete sense. Legislation passed in March 2013 to integrate the ranks (duiwu) of four maritime law enforcement agencies into a new China Coast Guard within a re-constituted State Oceanic Administration (SOA) was a pledge of commitment rather than a plan of action. Many, many difficult decisions would have to be made, countless details to be fleshed out. That responsibility would largely fall on Meng Hongwei, the first head of the China Coast Guard, and Liu Cigui, Director of SOA and the China Coast Guard’s first political commissar.