The Gabe Collins Bookshelf: China Energy, Strategic Resources, Security Implications & More!

Once a versatile China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) team member with us at the U.S. Naval War College, subsequently the co-founder (with me) of our China SignPost™ 洞察中国 analytical website, and a valued research colleague ever since, Gabe Collins is one of the only professionals I know of who generates analysis of the highest caliber from a commercial, a legal, and a government perspective.

A native of the Permian Basin, Gabe’s also gone from being the 5th-fastest boys’ 100M sprinter at the 2000 New Mexico State Track Meet (2nd in his school division) to being a Texas-licensed attorney and a leading water, resources, and strategic commodities expert. He was probably the only one of the 4,400 undergraduates at Princeton University when we were there (he as an undergrad, I as a grad student; same Chinese classes and study with Princeton in Beijing) to help pay his tuition by working in the oilfields of Southeast New Mexico as a roustabout.

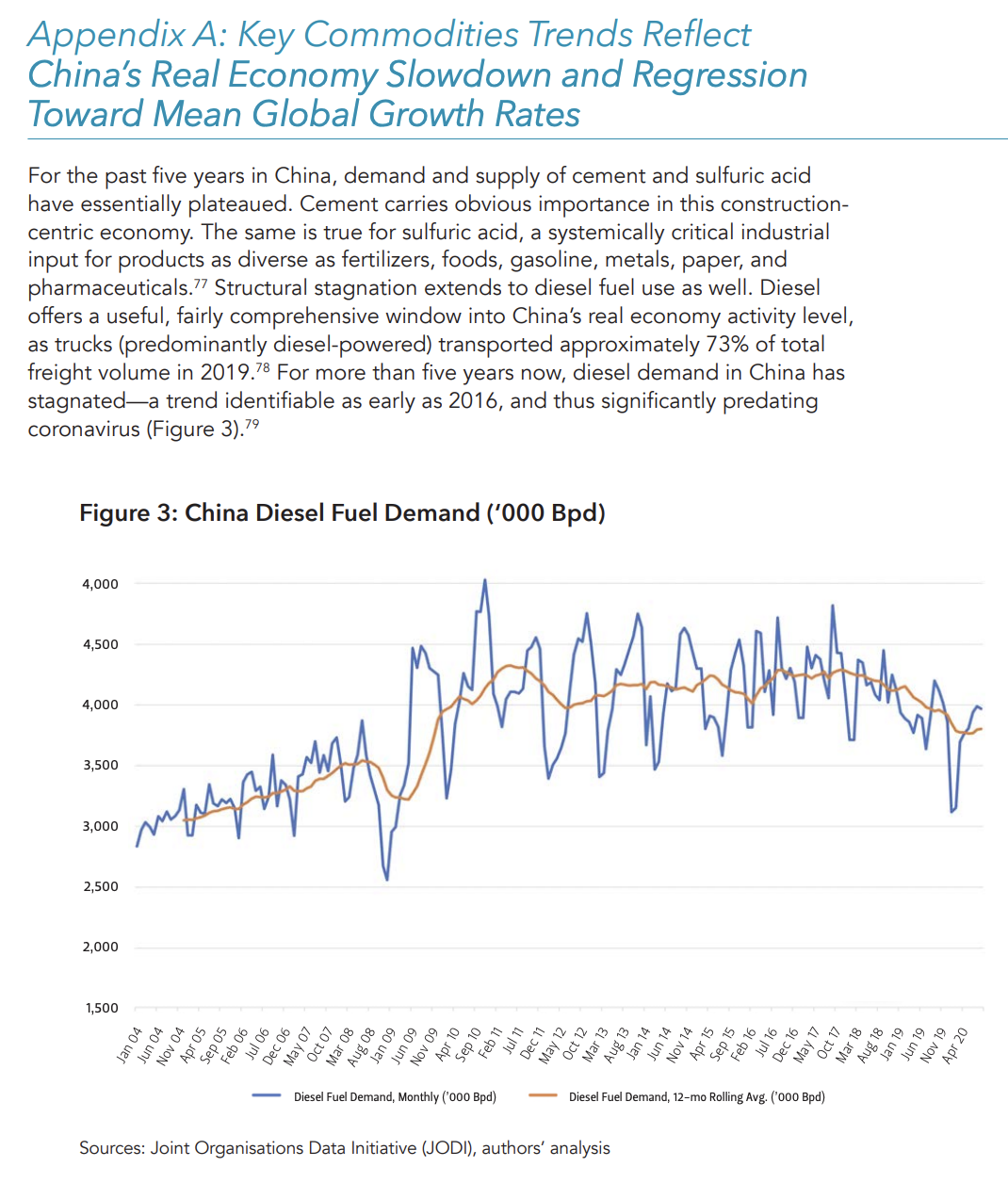

To earn his sweat money at the Cactus Queen enhanced oil recovery project, Gabe sprayed and pulled weeds, moved pipe, repaired broken pumps and saltwater injection wells, loaded trash trailers, and removed the rotted carcass of a cow that had died under a tank battery—all while handling 105-degree heat, wearing a hydrogen sulfide detector, and avoiding black widow and rattlesnake bites. After all that, nothing that involves sitting at a computer and crunching numbers could possibly faze him. As long as America keeps producing the likes of Gabe Collins, it will have a bright future ahead indeed.

To help make Gabe’s insights more broadly available, I’m sharing links and excerpts from some of his publications below. Given the extreme volume of Gabe’s publications, I’ll keep adding to the content below as time permits…

PUBLICATIONS BY GABE COLLINS (SELECTED):

Gabriel B. Collins and Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Energy Nationalism Means Coal Is Sticking Around,” Foreign Policy, 6 June 2022.

Green plans are secondary to political demands.

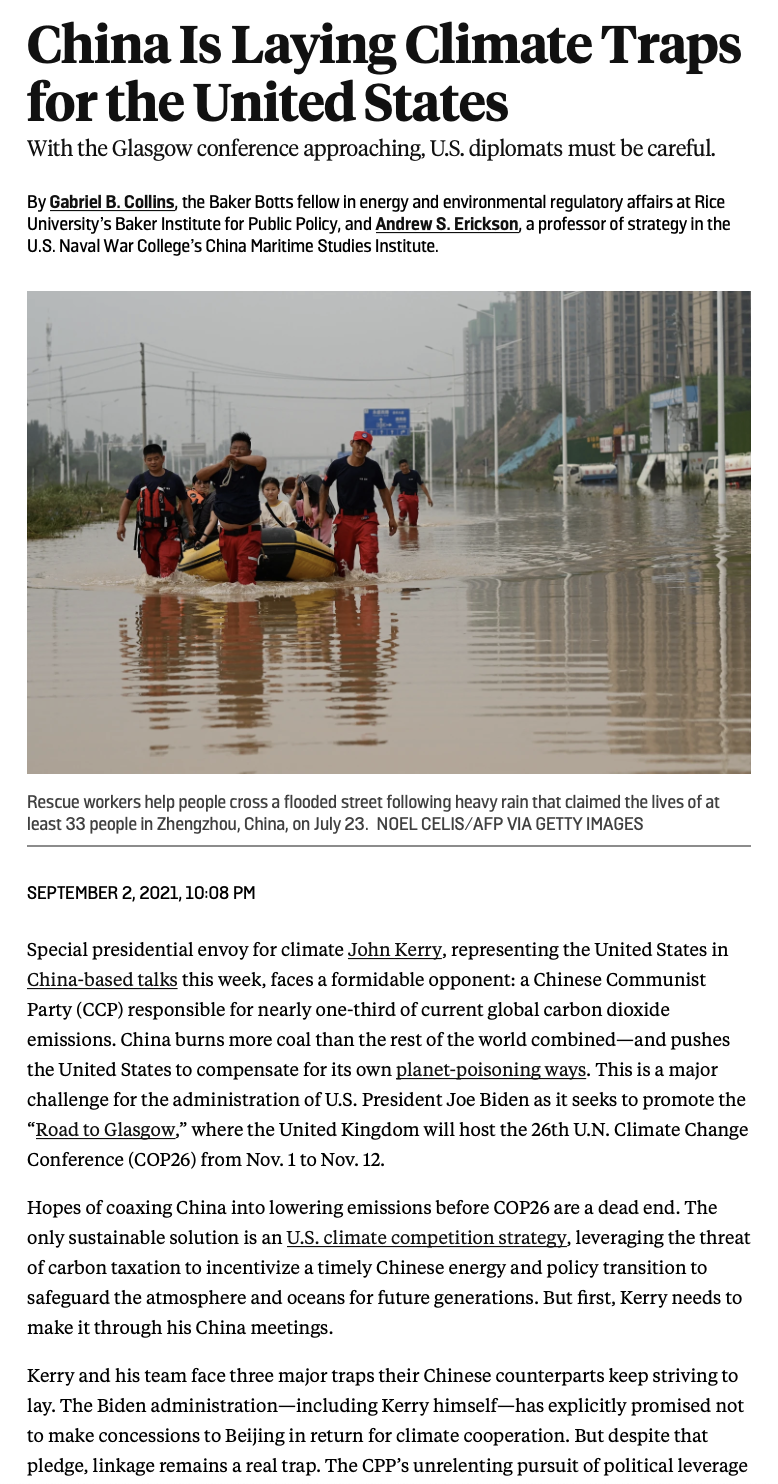

By Gabriel B. Collins, the Baker Botts fellow in energy and environmental regulatory affairs at Rice University’s James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, and Andrew S. Erickson, the research director in the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute.

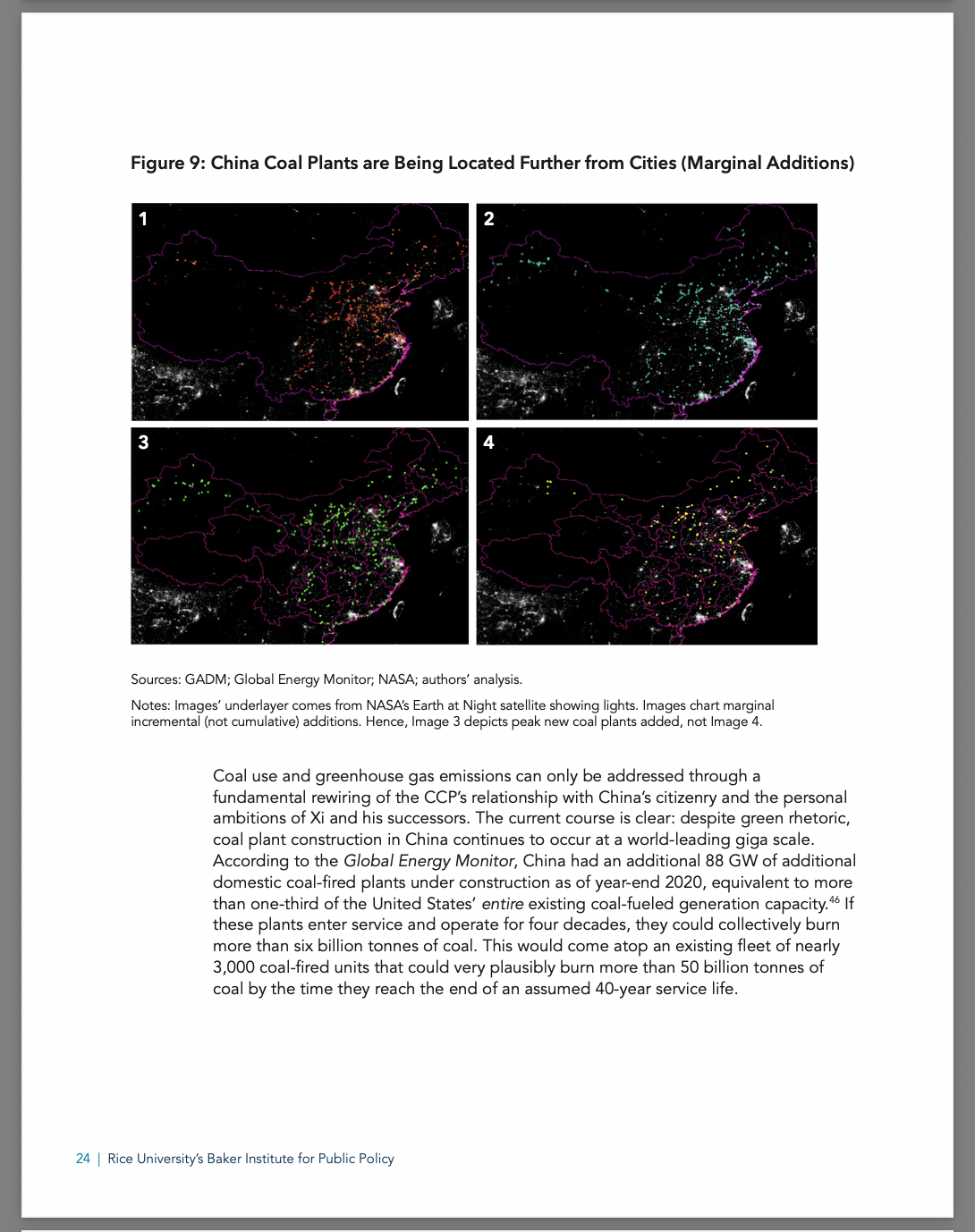

China is touting its renewable energy investments and has vowed to “accelerate the pace of coal reduction” in coming years. Yet in practice the country continues doubling down on coal on the back of blackouts, energy security fears, great-power competition, and Europe’s biggest land war in nearly 80 years. Fear and risk aversion both favor coal entrenchment, and both are in ample supply in Beijing these days.

As a result, millions of metric tons per day of additional greenhouse gases surge into the atmosphere. And the coal hopper is being loaded higher. Chinese policymakers recently greenlighted a coal mine capacity expansion of an additional 300 million metric tons in 2022—almost the annual production of the entire European Union. That’s enough coal to fill a train of standard rail hopper cars that would wrap around the entire equator, plus enough left to stretch from Washington, D.C., to Los Angeles. … … …

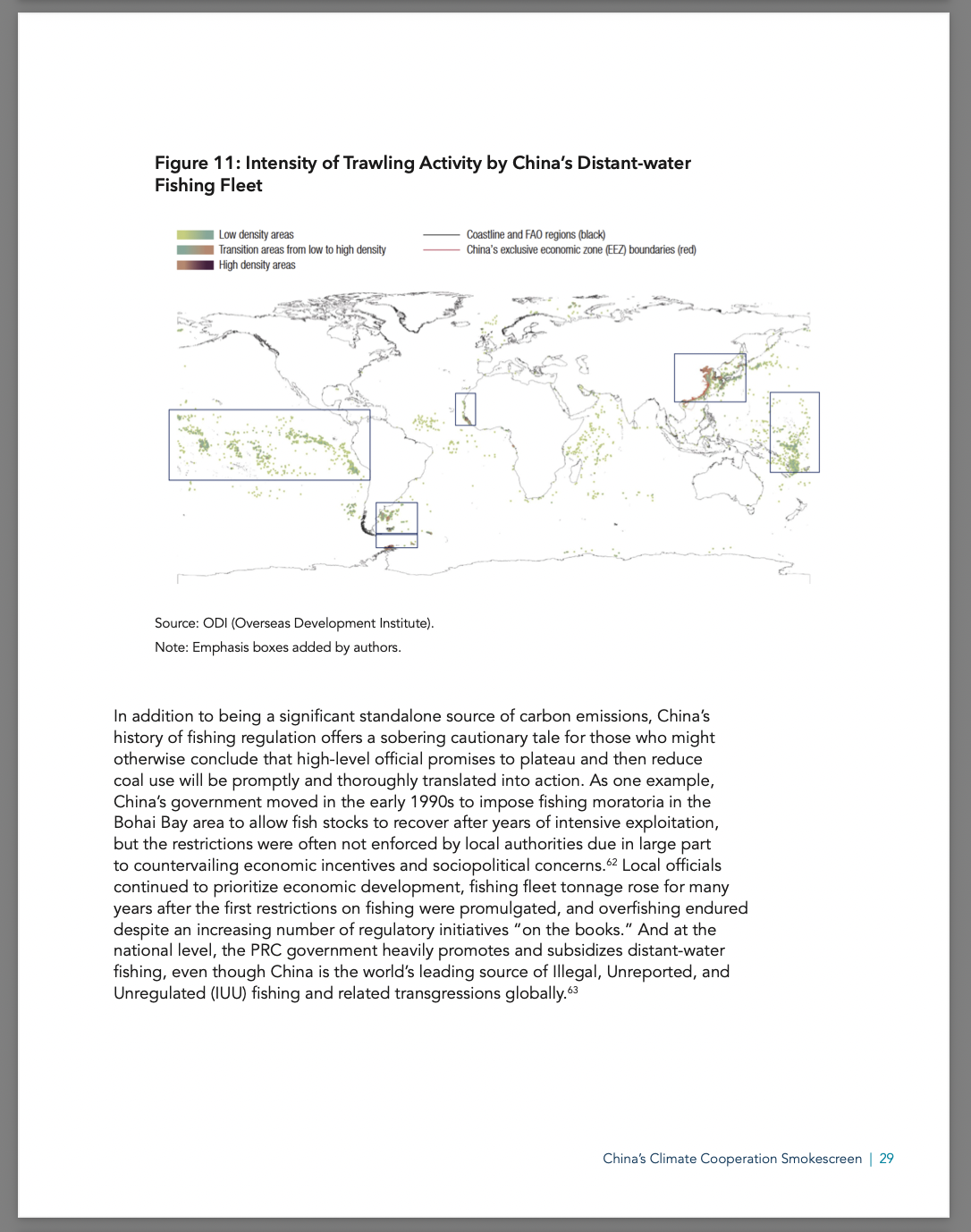

However much “green leadership” the party talks in international forums, it keeps leading the world in burning coal. It treats climate change as a source of leverage in its unrelenting quest to retain a monopoly on political control domestically and deference abroad. The disasters of the global commons can be easily blamed on the rest of the world; power and economic failures at home demand responsibility, or at least scapegoats. Meanwhile, as Chinese policymakers continued allowing King Coal to undercut Queen Green, millions of metric tons per day of additional greenhouse gases would surge skyward.

Cooperating with Beijing requires trusting in the good faith of a dictatorial regime that backslides on binding international environmental commitments and appears to be copping out on COP26’s call to accelerate the phasedown of unabated coal combustion. Worse still, Beijing demands tangible upfront geopolitical concessions by Washington in exchange for ephemeral half-promises on China’s own part—promises that have never materialized in the past.

Domestic economic and political survival imperatives will consistently shunt aside foreigners’ hopes and aspirations for a cleaner Chinese energy system—just as they are now with Beijing’s approval of one of the biggest annual coal production increases in decades. “Trust but verify” falls apart fast when an interlocutor is structurally disincentivized from sustained positive action and treats entreaties for cooperation as opportunities for exploitation.

Accommodations or self-limitations made to coax China to discuss climate issues would, in fact, make the United States, East Asia, and the world lose twice. America would weaken its economy and stress its social fabric while forfeiting its ability to effectively confront China’s ongoing coercive envelopment efforts in the Indo-Pacific, as Chinese interlocutors stall at the negotiating table. Beijing would win on the geopolitical front, but all parties would ultimately lose from degradation of our shared atmospheric and maritime biosphere.

China’s doubling down on coal so soon after the Glasgow summit makes it clear that climate cooperation simply won’t work with Xi and the party pursuing parochial priorities in ruthless Leninist fashion. The only way to avoid continual cop-outs is clear: It’s time for climate competition.

Gabriel B. Collins is the Baker Botts fellow in energy and environmental regulatory affairs at Rice University’s James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, whose funding sources are listed here, and a senior visiting research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Andrew S. Erickson is a professor of strategy and the research director in the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute and a visiting professor in full-time residence in Harvard University’s Department of Government.

The U.S. Naval War College is funded by the U.S. Department of Defense. The views expressed by the authors are theirs alone. They in no way represent those of the Naval War College, the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other organization with which the authors are, or have been, affiliated.

***

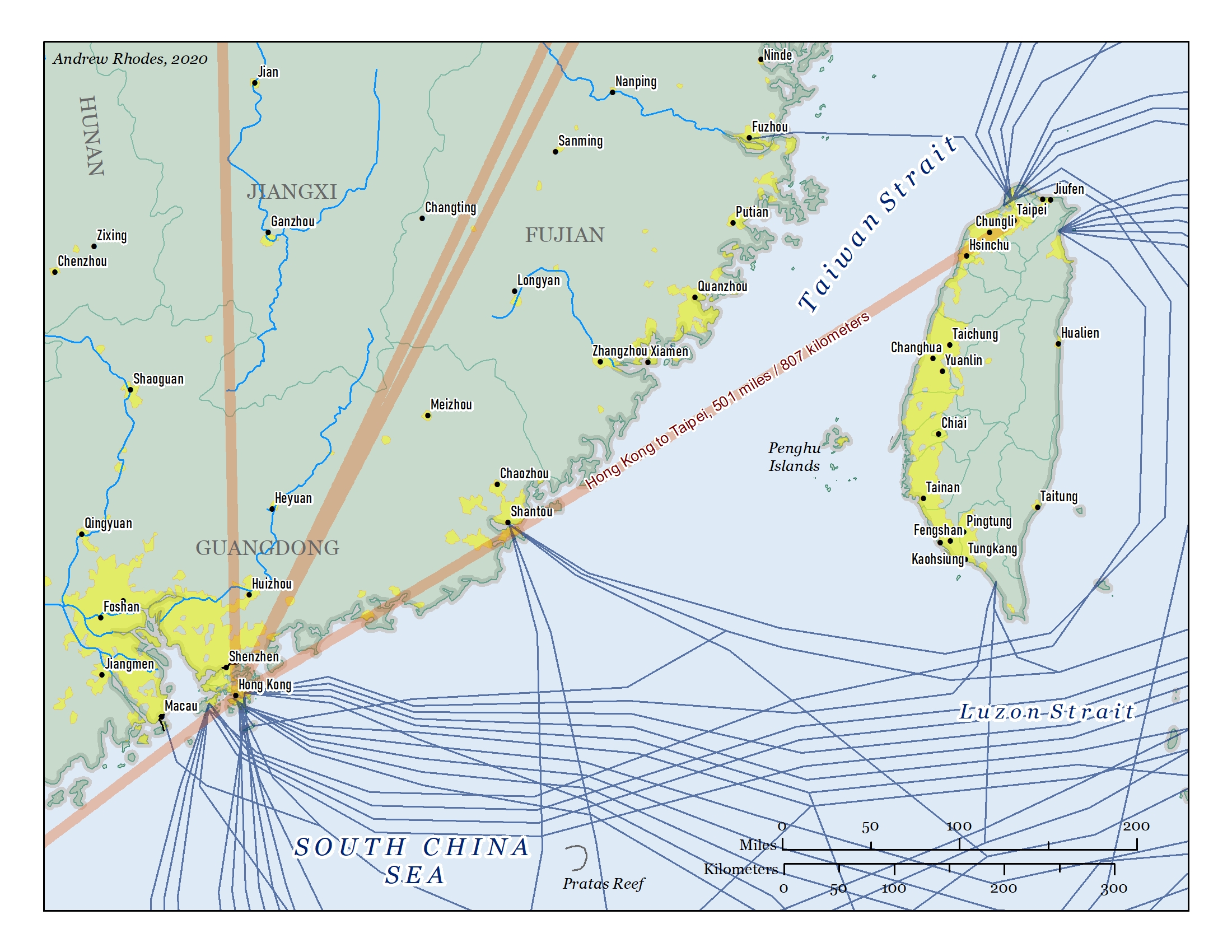

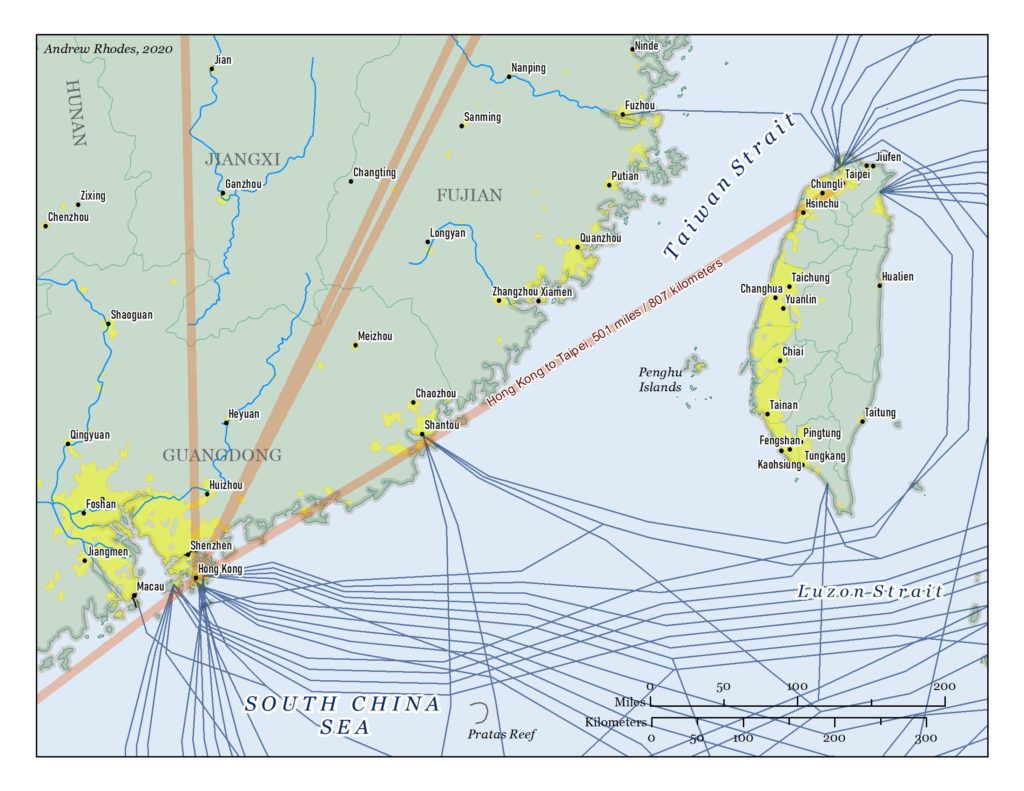

To make Taiwan an indigestible choking hazard, here’s exactly where to invest now.

Andrew S. Erickson and Gabriel B. Collins, “Eight New Points on the Porcupine: More Ukrainian Lessons for Taiwan,” War on the Rocks, 18 April 2022.

Watching Russia falter in Ukraine, Chinese President Xi Jinping may conclude that if he decides to invade Taiwan, he cannot hope to achieve victory with little or limited fighting. The risk is that this will lead him to prepare a much bigger assault, deploying far heavier and more concentrated firepower to batter the island into submission.

In response to this possibility, a number of recent assessments have called for Taiwan to pursue an “asymmetric” dragon-choking “porcupine strategy” prioritizing “a large number of small things” for its defense. In short, turn the anti-access/area denial issue on its head and present People’s Liberation Army forces with multiple, numerous, hard-to-counter defenses that specifically target key Chinese military weaknesses. Drawing on Ukraine’s experience, there are eight concrete areas where the United States and Taiwan should now invest to make the island tougher to invade, even harder to subdue, and harder still to occupy and govern: ballistic missile defense, air defense, sea-denial fires, shore-denial fires, mine warfare, information warfare, civil defense, and the resilience of critical infrastructure.

The goal of these measures is to present a robust anti-access/area-denial threat to Beijing’s aspirations in Taiwan, clouding its prospects for military and political success and, ideally, keeping the threat of Chinese invasion hypothetical through this critical decade and beyond. … … …

***

Check out this must-read testimony on China’s energy import dependency from Gabe Collins at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy! It’s part of a timely U.S.-China Economic & Security Review Commission (USCC) hearing on PRC energy issues…

Watch the webcast, read the text, or just scroll through Gabe’s 16 data-rich exhibits—and I guarantee you’ll come away with invaluable insights. Access full information, revealing graphics and scrollable screenshots here…

Gabriel B. Collins, “China’s Energy Import Dependency: Potential Impacts on Sourcing Practices, Infrastructure Decisions, and Military Posture,” testimony at hearing on “China’s Energy Plans and Practices,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 17 March 2022.

Click here to watch a webcast of the hearing.

***

FULL TEXT OF TESTIMONY BY GABRIEL B. COLLINS, J.D.:

Gabriel Collins, J.D., Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, Center for Energy Studies[1]

Executive Summary:

- China is likely to remain heavily reliant on seaborne crude oil, and to a lesser extent, on liquefied natural gas supplies. Sustained high oil and gas prices could incrementally ameliorate the trend by incentivizing conservation, making domestic drilling more profitable, and further accelerating vehicle fleet electrification efforts. Oil and gas storage capacity in China is also likely to expand substantially in coming years.

- More gas will come overland from Russia, particularly in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine and the likely subsequent move by European consumers to reduce imports of Russia-origin gas.

- China will generally seek to maximize benefits while minimizing costs, which means a default path of continuing to rely substantially on U.S. control of the global maritime commons outside of East Asia. Certain energy exporter states, particularly in the Gulf Region, seek to play the U.S. off China to maximize their strategic leverage but it remains unclear whether China would try to supplant the U.S. as the chief security guarantor and assume the many burdens that come with that status.

- A key exception to this trend would come if the U.S. decisively stepped back from the region and left a security vacuum and access to a physical infrastructure presence network constructed over several decades. A lesser, but still impactful version of this scenario could arise if U.S. partners in the Gulf continue doubting long-term U.S. commitments to their security. This dynamic may already be playing out in its early stages.

- Emphasizing overland oil and gas transit routes for suppliers other than Russia and the Stans would impose steep economic penalties on Chinese consumers. Adopting a more militarized oil and gas import security policy would augment these economic costs and also impose military tradeoffs Beijing would very likely seek to avoid.

- Rather than spend what could be upwards of $50 billion per year to move seaborne oil onto pipelines and build a Middle Eastern base network, China is more likely to rely on market means (inventories and fuel pricing) and technological transformation—especially electric vehicles—to try and manage risks associated with oil import dependence.

- China is likely to continue its accelerated naval modernization program, including both quantitative and qualitative improvements to its naval and air assets, as well as special operations forces. Oil and gas import security do not appear to be a core driver of these efforts, but naval, air, and special operations capabilities are fungible across theatres on relatively short notice. A key warning indicator of strategic intent would be pursuit of facility access in energy-rich regions, especially facilities with deep draft ports and airfields able to accommodate mass aerial entry of personnel and materiel and access agreements that permit placement of munitions and execution of kinetic combat operations.

Intro:

This testimony focuses on China’s interests in fossil energy resources and how they affect its energy procurement infrastructure and ability to commercially and physically safeguard this sourcing footprint and the economic interests that depend on it. “Fossil energy resource” means “coal, crude oil, and natural gas,” with the primary emphasis on crude oil and natural gas since China has abundant domestic coal reserves and can rapidly scale up production in response to energy crises, as it did in late 2021 and continues to do. The assessment addresses four core topical areas to set up the final section, which offers six recommendations for actions Congress can take to uphold and advance key U.S. national interests. Key topics are:

- Energy Demand and Sourcing: What does China’s current infrastructure for obtaining imported energy look like, was strategic framework was it built under, and how have sourcing approaches evolved over time?

- Energy Supply Geography: What volume of energy resources does China import overland versus by sea? To what extent do overland routes offer a potential shortcut to the Persian Gulf?

- Handling Energy Supply Disruptions: How is China postured to handle energy supply disruptions, including those from armed conflict?

- Military Defense of Energy Sources and Transit Routes: What are China’s current and prospective future capabilities for securing energy imports, both at the source and along key transit routes? To what extent has energy import dependency shaped development of military capabilities including air and naval power projection and ground forces, including special operations?

- Recommendations for Congress

China’s Energy Demand and Sourcing

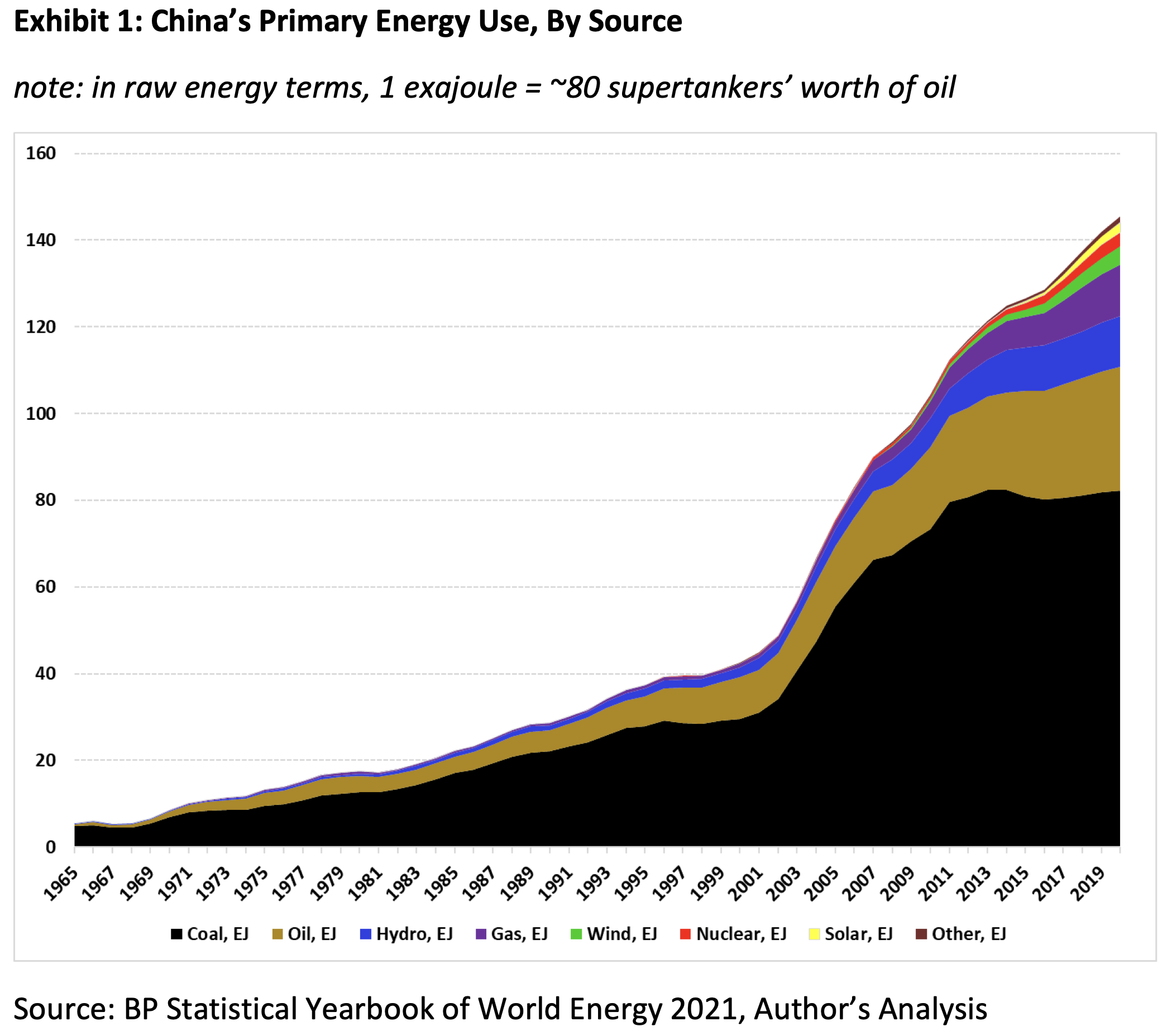

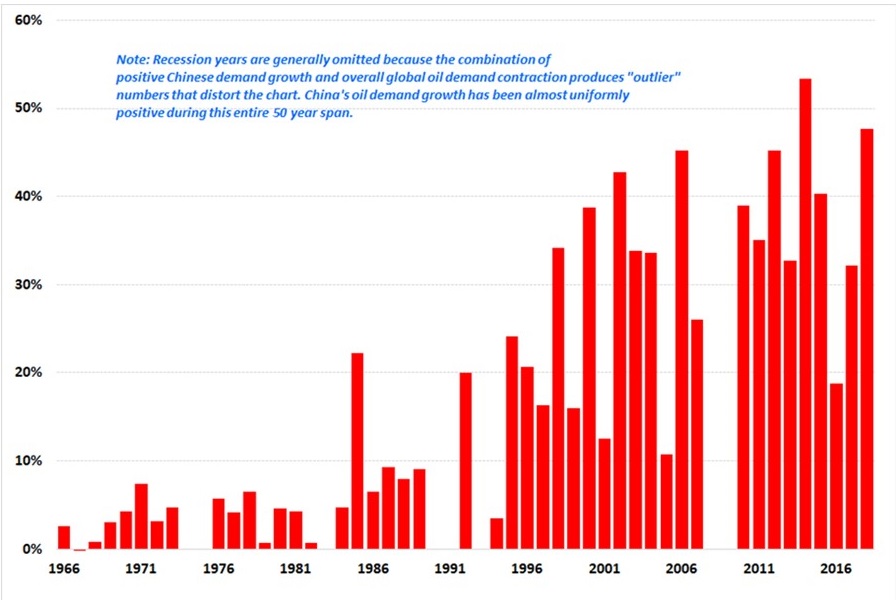

Oil and natural gas are China’s second and third-largest sources of energy and now account for about 28% of China’s total primary energy use, up from 22% in 2010 (Exhibit 1). Natural gas use alone is now larger than hydropower and exceeds wind, solar, and “other” renewables by about 50%. For oil in particular, China has for years been the world’s largest source of incremental demand growth and even in pandemic-crimped 2020, still saw demand increase by about the same volume of oil that the entire country of Israel consumed daily that year.

Exhibit 1: China’s Primary Energy Use, By Source

note: in raw energy terms, 1 exajoule = ~80 supertankers’ worth of oil

Source: BP Statistical Yearbook of World Energy 2021, Author’s Analysis

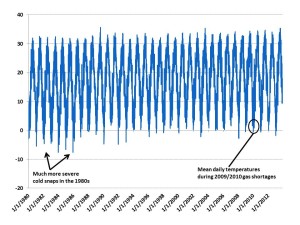

The analysis excludes hydropower, renewables (which in China primarily means wind and solar), and nuclear energy. The reason for doing so is that for PRC policymakers, “energy security” is synonymous with “import dependence.”[1]While American analysts might view events such as the 2021 Texas Blackout as energy security issues, their Chinese peers broadly view challenges that are localized and soluble through domestic action as being outside of the securitized paradigm that imported resources fall into. Put differently, Chinese decisionmakers are more likely to consider oil disruptions national security problems (国家安全问题) and electricity supply issues as social/economic problems (社会经济问题).[2] Beijing, provincial, and local officials all respond robustly to both sets of challenges, but with one potentially overtly securitized and the other not.

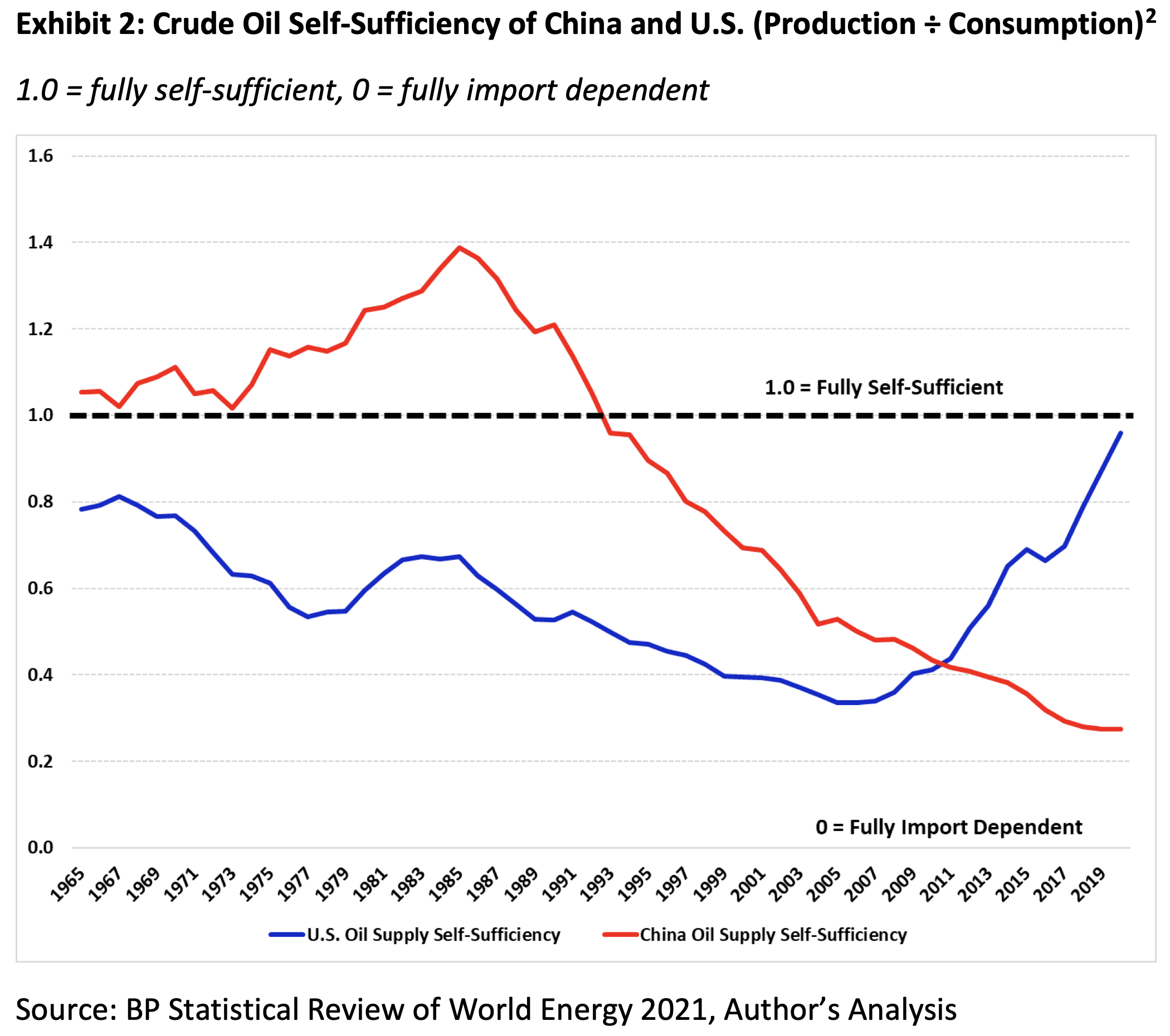

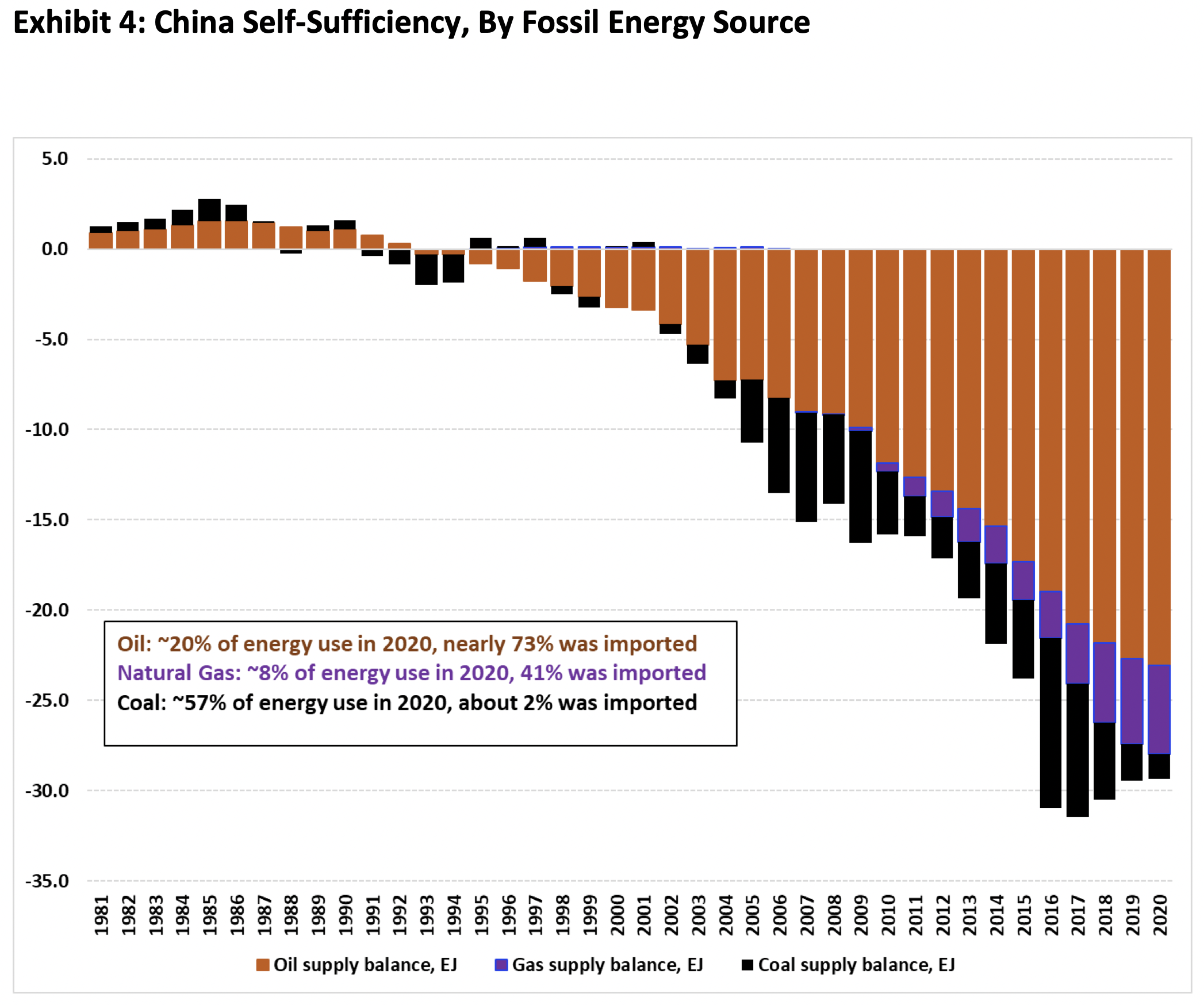

Accordingly, Yangtze River water spinning generation turbines at the Three Gorges Dam and solar panels produced domestically—or for nuclear power, a combination of domestic uranium reserves, multi-year intervals between refueling, and a mandated 10-year reactor fuel stockpile–mitigates the risks of import disruption and places those energy sources in a non-securitized category.[3] In contrast, oil and gas have both become increasingly vital vectors of import dependency for China. By 2020, China imported more than 70% of its oil and 40% of its natural gas. For perspective, China’s present oil import dependence ratio approximates where the United States was in the early 2000s, a period of acute anxiety over resource security and one where fateful policy decisions—including the invasion of Iraq—were undertaken for various stated reasons, but all under a cloud of perceived oil insecurity.

Exhibit 2: Crude Oil Self-Sufficiency of China and U.S. (Production ÷ Consumption)[2]

1.0 = fully self-sufficient, 0 = fully import dependent

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2021, Author’s Analysis

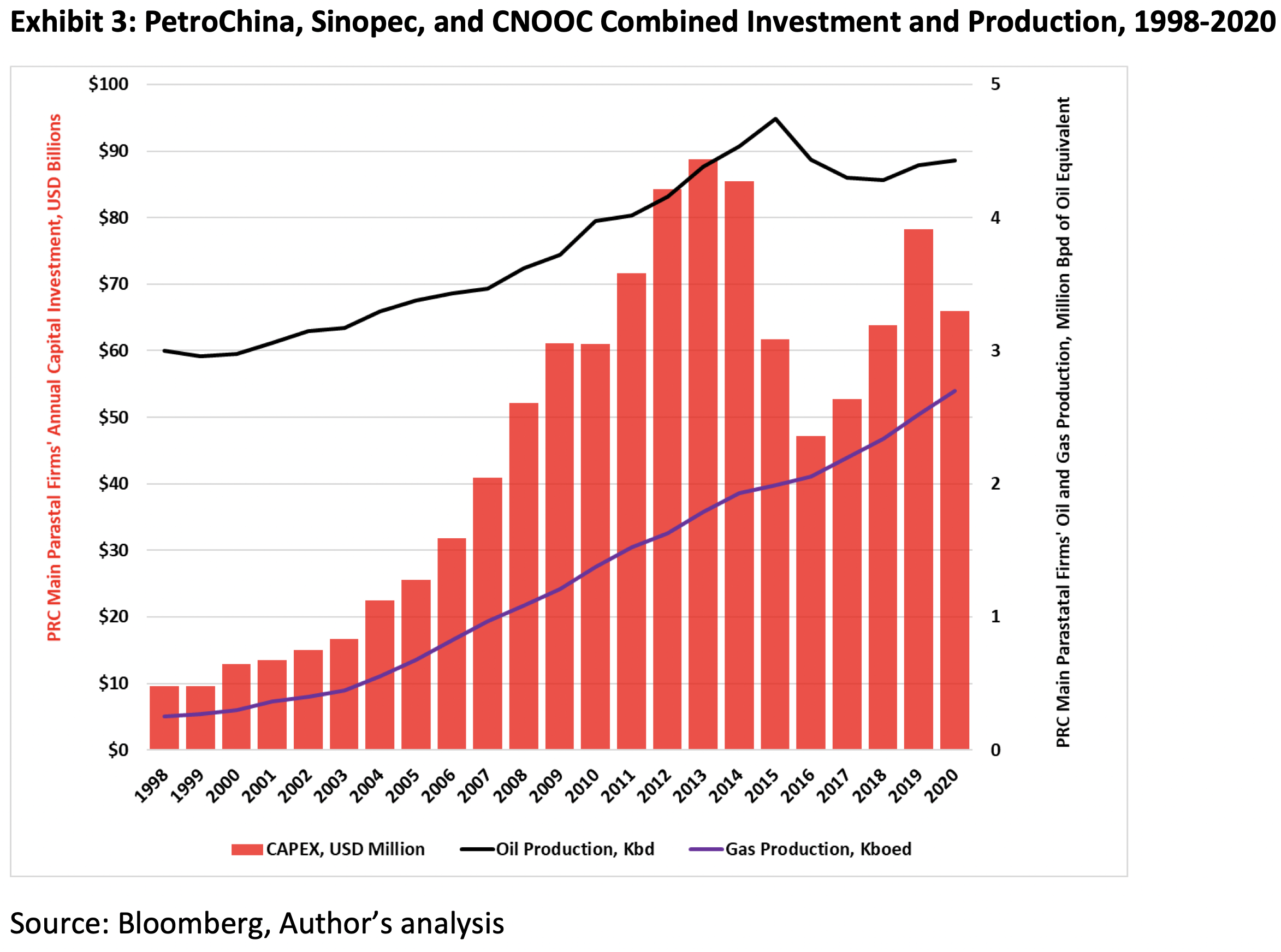

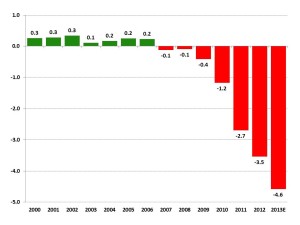

Furthermore, the past 20 years make one thing increasingly clear: unlike the United States, China is not going to drill its way to lower crude oil and natural gas import dependence. Between 2000 and 2013, China’s “Big 3” (PetroChina, Sinopec, and CNOOC) ramped up their combined annual capital investment, which peaked in 2013 at about seven times the 2000 level and declined subsequently (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: PetroChina, Sinopec, and CNOOC Combined Investment and Production, 1998-2020

Source: Bloomberg, Author’s analysis

This massive effort brought oil production from 3 million bpd in 2000 up to about 4.4 million bpd in 2020. Gas production grew more substantially, rising about 10-fold. But for both commodities, import dependency steadily deepened because domestic production simply could not keep pace with demand growth despite cumulative nominal expenditures of more than $1 trillion USD.[3]Indeed, it is likely that China’s domestic oil production peaked in 2015.[4] For perspective, U.S. shale producers invested roughly a trillion dollars between 2010 and 2020, during which domestic light tight oil production leapt nearly nine-fold from 842 thousand bpd to 7.4 million bpd.[4]

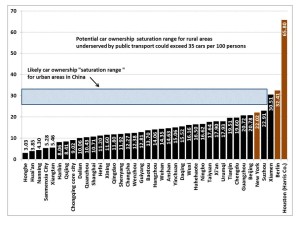

Instead, Beijing is taking a different tack: (1) taking in additional imports of oil and gas (with seaborne shipment dominating incremental volumes), (2) seeking to maximize its oil and gas procurement flexibility, and (3) aggressively promoting transport electrification to reduce oil demand. China sold approximately 3 million plug-in EVs last year into a car parc of approximately 225 million vehicles—the world’s second largest after that of the United States. As such, even if it doubles the current annual sales rate, fleet turnover is still a multi-decade endeavor. And as the example of Norway shows, even as EVs grab a much greater share of the fleet (more than 80% of new vehicle sales in 2021 and about 20% of the total passenger vehicle fleet), motor fuels demand can remain persistently high.[5]

Oil is consumed by far more than just passenger and light business vehicles and the heavy transport, aviation, and shipping sectors will likely be tougher to electrify. Natural gas, meanwhile, is playing a key role in helping large coastal cities in China improve residents’ health and lives by reducing emissions from home heating and industrial boilers that formerly burned coal.[6] Oil and gas also yield critical petrochemical building blocks—including for materials needed by EVs and other energy transition technologies such as wind turbines and solar panels.[7] In short, China’s leadership will for years to come, have to grapple with significant, and perhaps even larger, oil and natural gas import dependence.

Exhibit 4: China Self-Sufficiency, By Fossil Energy Source

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, Author’s Analysis

It is helpful to frame analysis of China’s energy sourcing with the lens of energy security, which the Chinese government (like other major global energy consumers) presumably seeks to attain via its energy resource-related policies and activities abroad. Energy security incorporates three core concepts: (1) adequacy and diversity of supply, (2) stability of price, and (3) maintaining a relatively low price.[8] For China specifically, the need to ensure adequate and diverse oil and gas import supplies drives an increasing dependence on seaborne imports but is generally handled through day-to-day activity by firms that while often state-controlled, generally behave commercially.

Trying to maintain price stability and affordability presents more complex challenges, ones that implicate internal dynamics in both the importer and exporter countries and thus feature intertwined political, diplomatic, and potentially, military dimensions. For its entire post-Mao industrial rise to date, it has been able to free ride off on U.S. efforts to maintain flows of oil and LNG from the Middle East and the ensure free maritime transit for the tankers that bring molecules to market.

The U.S. retains deep energy-centric interests in the Persian Gulf region.[9] Yet a combination of increased domestic energy abundance over the past 15 years, an apparent breakdown in the historical U.S.-Saudi partnership as OPEC increasingly views U.S. shale producers as competitors, and a push from some quarters to de-emphasize Washington’s military role in the region suggest a much more uncertain future. Multiple scholars now question the wisdom of expensive U.S. military presence to defend Gulf oil and gas flows, while China-focused scholars and strategists frame the Persian Gulf region as a secondary priority that should not detract from strategic focus on ensuring China does not achieve hegemony in Asia.[10]

Pullback discussions may represent perception more than reality, especially as oil prices rise in early 2022. U.S. policy has for decades emphasized paying close geopolitical attention to key oil producing countries. Indeed, multiple U.S. National Defense Strategy documents acknowledge energy’s importance to national security and the resultant perceived need to engage forward to, as the 2018 NDS puts it: “…foster a stable and secure Middle East that…is not dominated by any power hostile to the United States, and that contributes to stable global energy markets and secure trade routes.”[11]

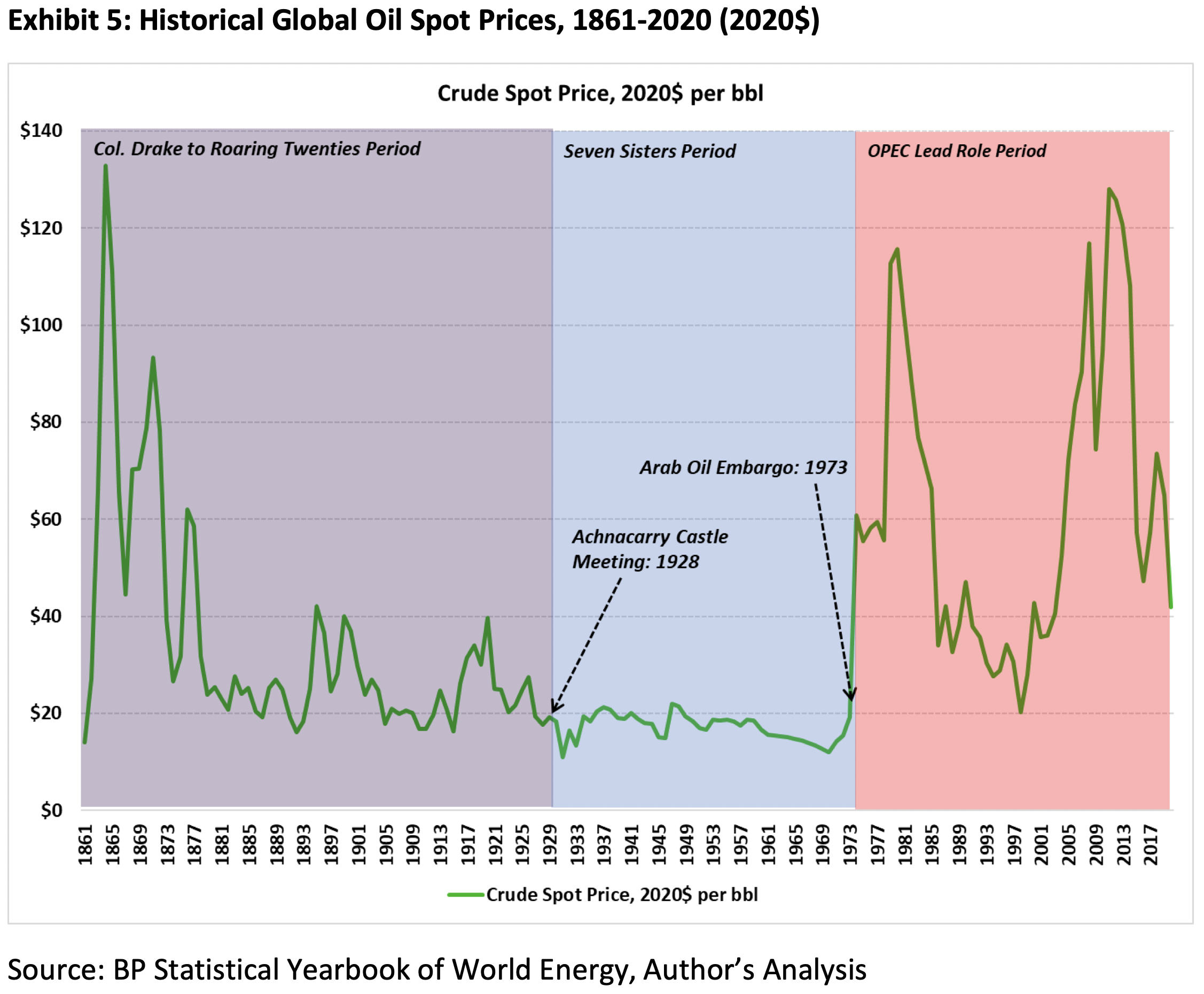

While price stability is a strategic objective, it has been fleeting in the global oil market and the future looks increasingly inclined to volatility. From 1928, when the so-called Seven Sisters[5]met at Scotland’s Achnacarry Castle to form an oil pricing cartel, until the 1960s when producer country nationalism began to erode their arrangement, oil prices enjoyed a remarkable run of stability. As the Achnacarry Agreement yielded to the next oil cartel, OPEC, oil price volatility followed with the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973 and the Iranian Revolution a few years thereafter. Oil prices were rangebound (in historical terms) from the mid-1980s to late 1990s, and then volatility ensued again as a product of China’s demand and the U.S. shale boom thereafter (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5: Historical Global Oil Spot Prices, 1861-2020 (2020$)

Source: BP Statistical Yearbook of World Energy, Author’s Analysis

The confluence of continued strong demand for oil, increasingly intense efforts to starve the sector of capital to try and force accelerated decarbonization[12], and the return of “blood and iron” great power politics—exemplified by Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine—portends price volatility ahead. Simultaneously, fundamental dynamics in the U.S. domestic energy security discussion suggest that despite oil market turbulence, the U.S. commitment to the Gulf Region remains unsettled.

The U.S. appears clearly positioned to be the world’s largest oil consumer and second -largest importer (after China) for years to come, since even intensified energy transition efforts will take decades to meaningfully shift American oil consumption patterns. Unlike China, the U.S. also appears likely to remain the world’s first or second-largest oil producer through at least 2030. Anti-fossil fuel domestic policies could change the trajectory, but in doing so would risk triggering a political backlash that likely ultimately leads to stronger consensus on the need to maximally exploit domestic shale resources to manage price volatility and perceived import risks.[13]

Coming years will likely feature increasing pressure upon Beijing to reduce oil import dependence by decreasing demand through transport electrification but also, potentially, to assume a more prominent role in Persian Gulf security if the U.S. elects to reduce its large residual military position there. It is even possible that a future U.S. administration more hospitable to domestic oil and gas resource development and less inclined to maintain large forward deployments in the Middle East might actively seek to force a leading Chinese role in Persian Gulf security. This would end its 40-year run of being able to “draft” off the United States and instead make it confront a strategic dilemma Washington has now grappled with for at least a decade—how to allocate combat power between its highest priority theater and the Gulf region.

Convergence of these factors—many of which are mutually reinforcing—points to China likely having to more seriously contemplate assuming a more substantive security role in key oil and gas producing geographies (aside from North America). China had made attempts to establish a presence near the Gulf Region before, including continuously deploying vessels on “anti-piracy” missions off the Horn of Africa since 2008 and building a permanent military base in Djibouti capable of docking any ship in the PLA Navy.[14] Chinese support for Saudi ballistic missile production and revelations in late 2021 of apparent Chinese attempts to build military infrastructure at the UAE’s Khalifa port suggests that Beijing may now be trying to lay deeper diplomatic and physical infrastructure for future energy security efforts.[15]

China’s Energy Supply Geography and Infrastructure

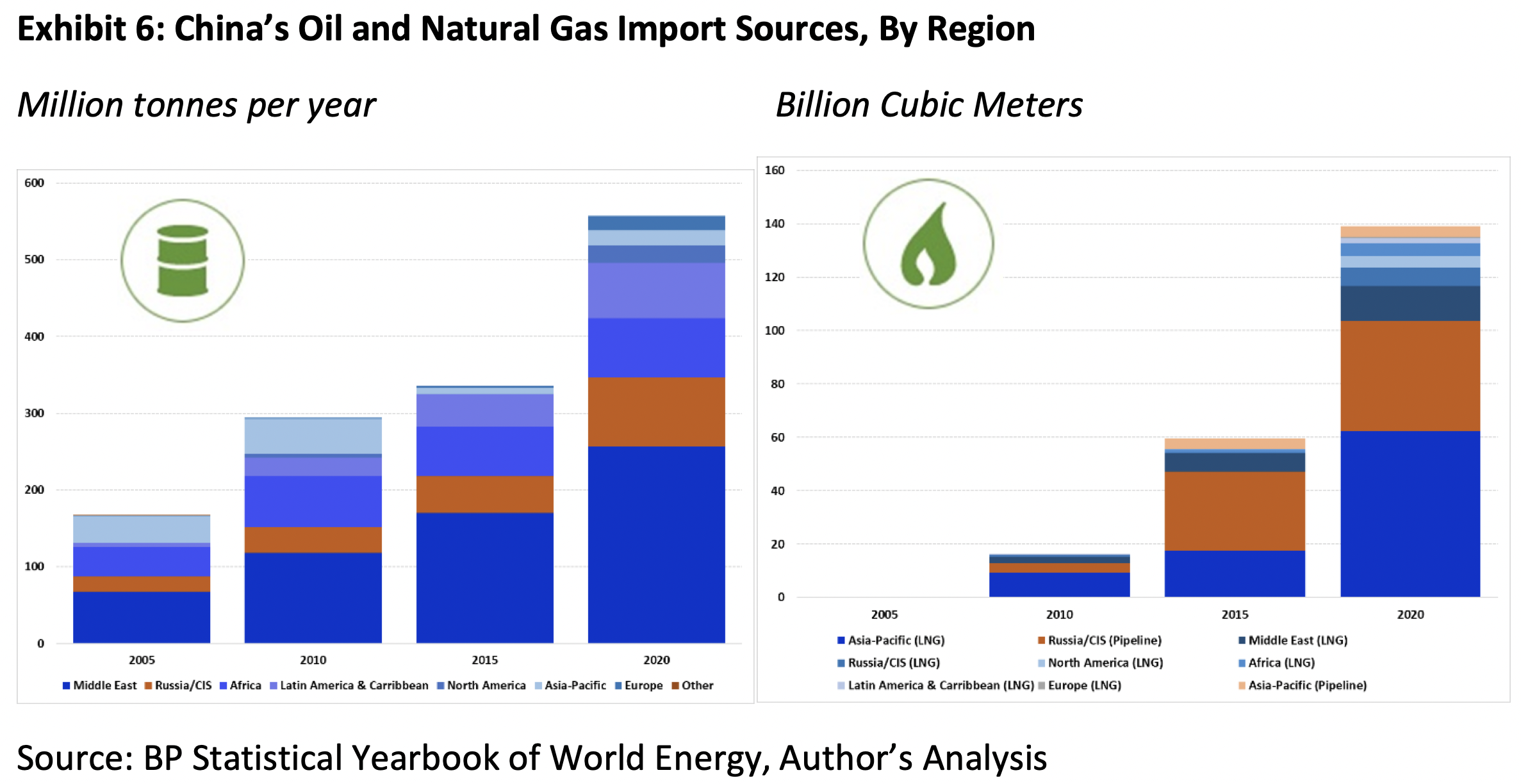

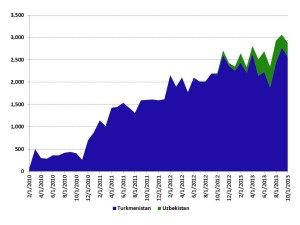

Looking at China’s oil imports by region, a few things immediately jump out. First, it is having to go further from home to buy barrels, with the Asia-Pacific’s share of imports declining from almost 21% in 2005 to only 3.5% in 2020. Among key oil import supply zones, three regions stand out. Russia and Latin America each saw exports to China rise by a bit less than 20% over the past 15 years. Volumes from the Middle East rose by nearly 50%, and account for close to half of China’s total imports (Exhibit 6). For natural gas, imports come from more geographically adjacent locales, with the biggest portion originating in the Asia-Pacific (primarily Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia) and Russia/CIS (primarily Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, with expansion expected from Russia).

Exhibit 6: China’s Oil and Natural Gas Import Sources, By Region

Million tonnes per year Billion Cubic Meters

Source: BP Statistical Yearbook of World Energy, Author’s Analysis

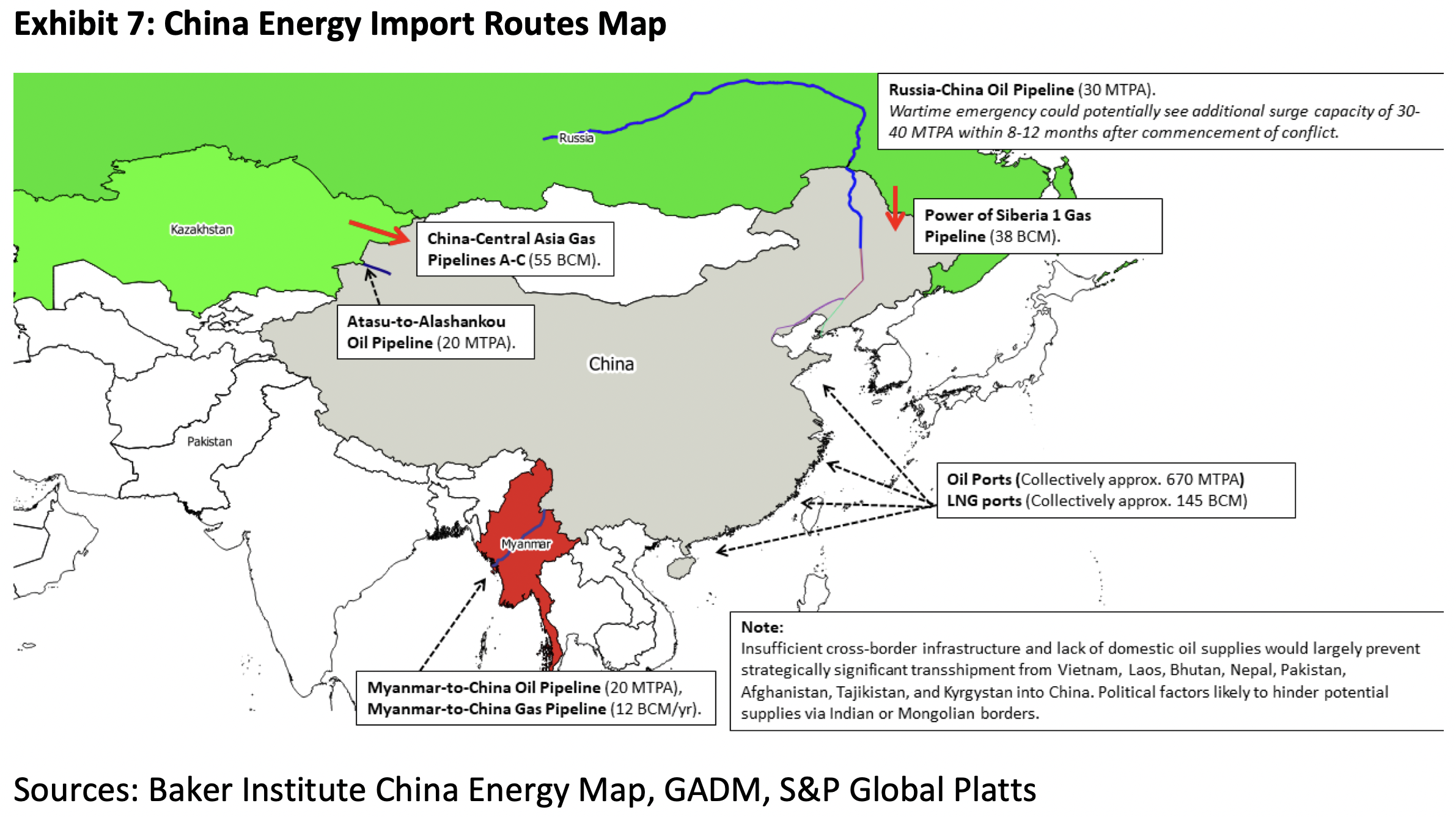

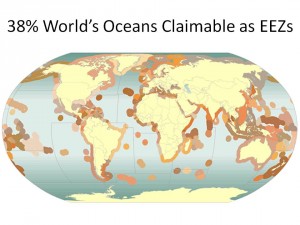

Some of the regional sourcing makes immediately clear how the molecules actually arrive in China. For instance, hydrocarbon supplies from Africa or Latin America obviously come by sea. Other exporters—especially Russia—supply significant volumes of oil and gas to China through both pipelines and maritime channels. Readers seeking a glimpse of the future need look no further than the respective capacities of overland and seaborne import routes for oil and gas. The three inbound oil pipelines at full tilt can transport a combined 70 million tonnes per year—roughly 14% of China’s total crude oil imports in 2021. In contrast, data from the Baker Institute China Energy Map suggest the country’s oil ports can take in 670 million tonnes per year—about 1.3 times what China actually imported in 2021 (Exhibit 7).

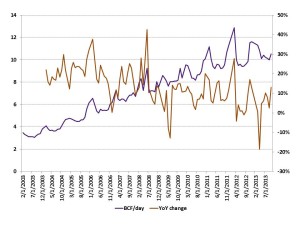

Overland routes fare better on the gas side, with approximately 105 billion cubic meters per year of pipeline capacity currently in service versus 169 BCM of gas actual imports in 2021. But like oil, seaborne import capacity is higher than overland (145 BCM/yr vs. 105 BCM/yr) and is also poised to grow faster than pipelines over the next 2-3 years.[16] By the late 2020s, the planned Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, now in the planning phase, could add 80 BCM/yr of pipeline supply (equivalent to about 50 million tonnes of LNG).

Intensifying economic warfare by the U.S. and Europe against Russia in the wake of that latter’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 is likely to make pipeline routes to China more attractive to Russia due to loss of European market share if consumers there diversify gas supplies and more attractive to China, which would rather procure preferentially-priced, semi-captive supplies via pipeline from Russia instead of bidding against European, Japanese, and South Korean consumers for premium priced seaborne LNG.

Exhibit 7: China Energy Import Routes Map

Sources: Baker Institute China Energy Map, GADM, S&P Global Platts

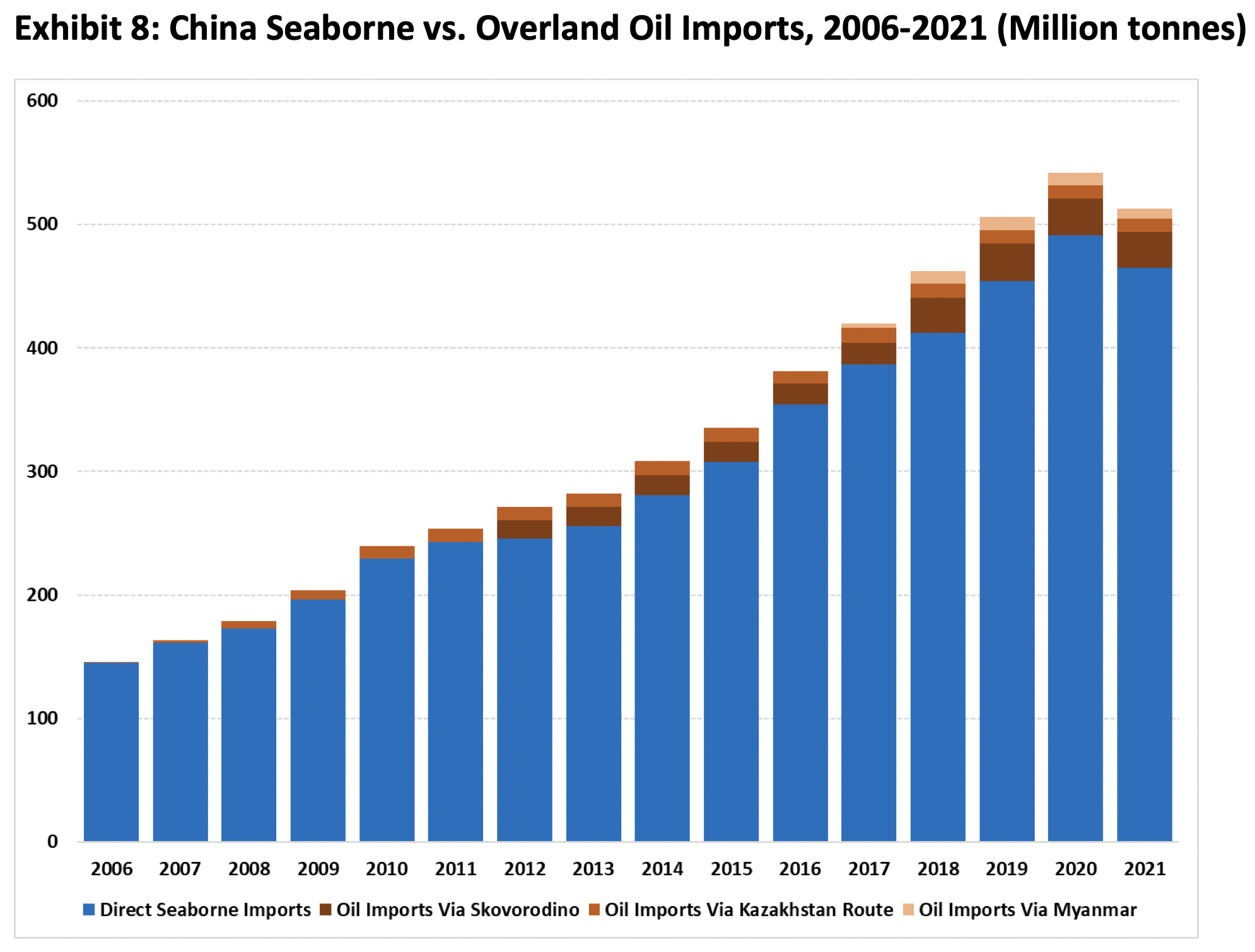

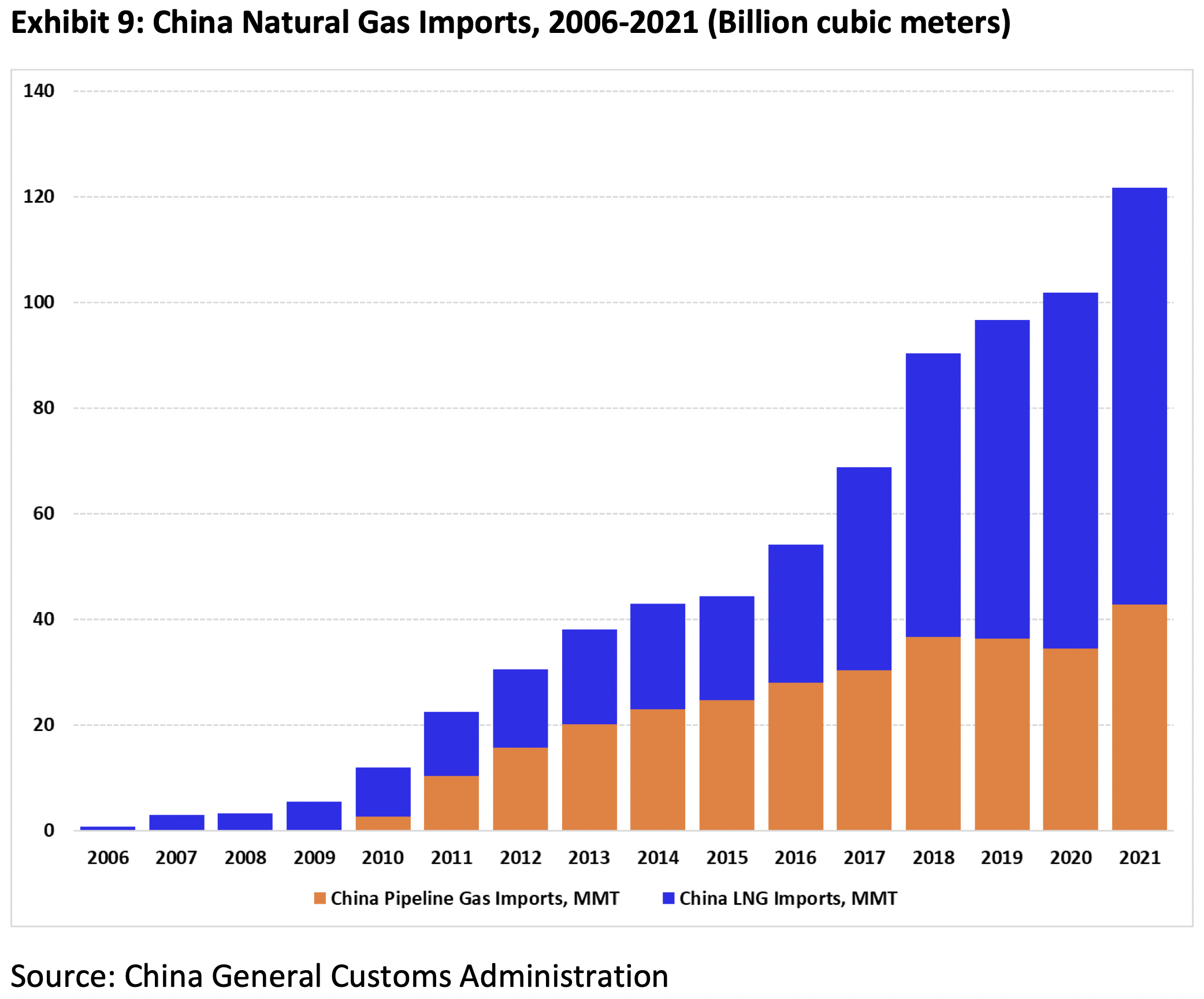

For both oil and gas, seaborne supplies have supplied most of China’s incremental import growth. Most additional oil import volumes—including from Russia—have come by sea since 2018. Pipeline gas was the largest source of imports in the early 2010s, but after 2016, inbound LNG supplies steadily rose while overland pipeline deliveries remained steady (Exhibit 8, Exhibit 9).

Exhibit 8: China Seaborne vs. Overland Oil Imports, 2006-2021 (Million tonnes)

Source: China General Customs Administration

Exhibit 9: China Natural Gas Imports, 2006-2021 (Billion cubic meters)

Source: China General Customs Administration

Do Current or Proposed Pipeline Routes Create Shortcuts to the Permian Gulf?

In a purely geographical sense, oil pipelines running north through Iran or offloading ships at Gwadar, Pakistan would each reduce the distance between Middle Eastern oilfields and China’s key refinery clusters by a few thousand kilometers. For instance, the sailing distance from the Strait of Hormuz to Zhoushan’s massive oil terminals is about 11,000 km by sea but closer to 7,000 km if tankers injected their cargoes into a hypothetical Pakistan-China pipeline beginning at Gwadar.

Yet there are distinct reasons such projects have not been built and these same factors are likely to induce Chinese policymakers and parastatal firms to continue favoring seaborne transit of oil and to a lesser, but important extent, natural gas. Key restraining factors include: (1) scale, (2) cost, (3) transit country risk, (4) flexibility of seaborne energy trade and vulnerability of pipelines, and (5) the opportunity costs of capital and excess shipping cost that could be deployed elsewhere in China’s economy—or in its military budget.

This subsection focuses on scale, cost, and pipeline vulnerability. The approximate quantification of capital and operational costs will illustrate the opportunity burden for the Chinese economy and military budget if Chinese importers were to favor pipelines of unprecedented size over proven maritime routes. This analysis runs through the scenarios and seeks to quantify approximate cost burdens not because the author thinks China will build massive pipelines to reduce maritime transit risk, but rather, to illustrate the sheer economic irrationality of doing so.

Scale

To make a real dent in China’s seaborne oil dependency, an overland pipeline project would have to be huge. It would be on par with Saudi Aramco’s East-West Pipeline, whose two parallel lines of 48 inches and 56 inches in diameter run 1,200 km from the country’s oil rich Eastern Province to the Red Sea port of Yanbu and can move 5 million barrels per day of crude oil.[17]Aramco is currently working to expand the system’s capacity to 7 million bpd and aims to complete the expansion by 2023.[18]

Put more bluntly, China would need additional import capacity in the same league as the world’s single-largest oil pipeline. And it would have to build it under much tougher physical and economic conditions. We’ll get into the economics shortly but consider the physical hurdles alone: While the Saudi East-West Pipeline climbs to a maximum elevation of approximately 1,000 meters, a pipeline transporting oil from coastal Pakistan into Western China would need to traverse the 4,700-meter Khunjerab Pass and oil would need to travel approximately 7,000 km to reach oil refining hubs near Shanghai or in Shandong. The distance would be even further to reach China’s third refining and petrochemical cluster in the Pearl River Delta.

Gas import dependency also appears poised to rise. Unlike the United States over the past 15 years, it does not appear that China will enjoy a domestic gas production resurgence large enough to roll back its rising import dependence. China is the logical market for gas reserves in Eastern Siberia that would otherwise be stranded by distance from Europe and the European market’s general lack of gas demand growth compared to China’s. Furthermore, the unfolding Ukraine crisis and Russian revanchist actions may finally prompt European consumer governments to take more dramatic action to reduce their dependence on gas piped from Russia, thus eliminating a potential source of future demand and further incentivizing Gazprom to construct export routes to China.[19]

China’s overall economic growth slowdown introduces uncertainty about how much its gas imports may grow by over the next decade, but it appears likely that Central Asia can only satisfy perhaps 25 BCM/yr of additional demand by 2030—roughly what the country’s gas use is forecast to grow by in 2022 alone.[20] Central Asian producers, especially Turkmenistan, have large reserves, but “above ground” issues will likely impede full development of the resource. Furthermore, a post-Ukraine invasion Russia isolated from opportunities in Europe will be incentivized to stifle (or gain economic control over) additional Central Asian exports to China, lest those displace future Russian gas sales into the increasingly indispensable Chinese market.

Despite Russia’s planned Power of Siberia 2 pipeline project (slated to bring 80 BCM of capacity online, likely in the late 2020s), even a slower rate of gas demand growth in China will thus likely exceed what overland suppliers can provide.[21] Accordingly, unless Chinese energy demand slows dramatically (possible) or there is a U.S. “shale boom-style” domestic gas production revolution (unlikely), the country’s gas import future also looks to be substantially seaborne, but with potentially significant expansion of pipeline gas supplies from Russia.[22] Having greater pipeline capacity and expanded LNG import facilities will give China optionality for gas sourcing, while also minimizing the perceived risk associated with seaborne imports.

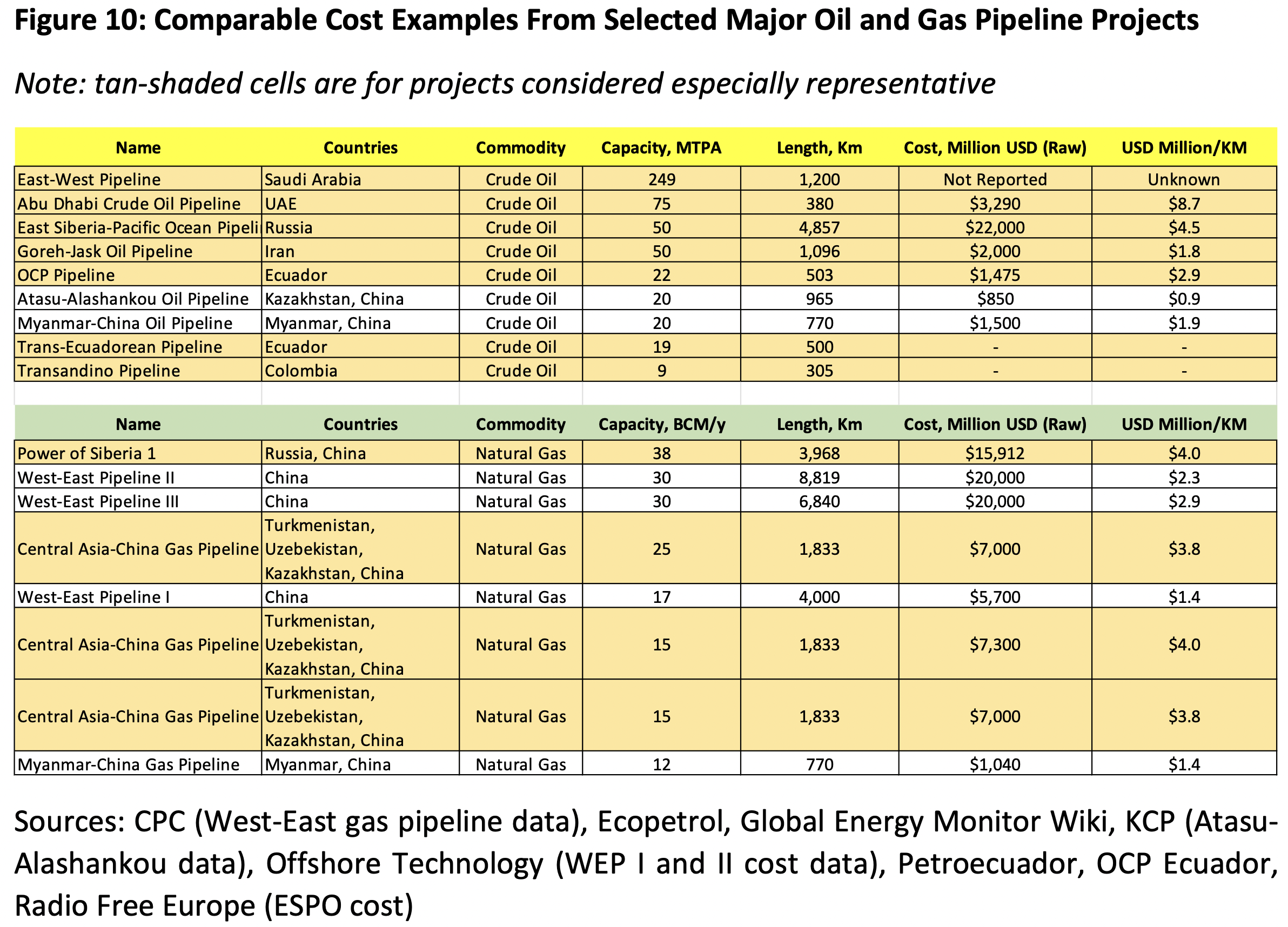

Cost

Several real-world examples help quantify the costs and difficulties likely to be associated with a pipeline that would have to traverse difficult topographical, seismic, and temperature environments, we can examine several real-world examples. Figure 10 summarizes important aspects of the projects, which are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 10: Comparable Cost Examples From Selected Major Oil and Gas Pipeline Projects

Note: tan-shaded cells are for projects considered especially representative

Sources: CPC (West-East gas pipeline data), Ecopetrol, Global Energy Monitor Wiki, KCP (Atasu-Alashankou data), Offshore Technology (WEP I and II cost data), Petroecuador, OCP Ecuador, Radio Free Europe (ESPO cost)

To illustrate the costs imposed by high mountain ranges, consider the Transandino, Trans-Ecuadorean, and OCP pipelines in Colombia and Ecuador. Each transports oil from lowland oilfields across the Andes Mountains with a peak line altitude of approximately 4,000 meters. The Transandino line ranges from 10 to 18 inches in diameter, spans 305 km, and can move up to 190,000 barrels per day.[23] The Trans-Ecuadorean line is 26 inches in diameter, about 500km long, and to move its design capacity of 360,000-to-390,000 bpd of crude oil, incorporates more than 101,000 HP of pumping capacity.[24] The OCP line is designed to move up to 450,000 bpd (22 MTPA) of heavier crudes along a 503km route similar to that of the Trans-Ecuadorean system.[25] Transport costs are significant—from $2.14 to $3.50 per barrel on the OCP system (roughly $0.56/100km moved), more than $2.50 per barrel (roughly $0.50/bbl/100km moved) for the Trans-Ecuadorean line and more than $4.50 per barrel for the Colombian project (roughly $1.50/bbl/100 km moved).[26]

These pipelines are much smaller in terms of size and daily capacity than what a Chinese route designed as a shortcut to the Persian Gulf would be and cross less physically severe mountains but incorporate other systems, such as massive uphill pumping capacity and pressure reduction stations for the downhill portions of the line. The capital costs would be enormous.

Data for oil pipelines in Exhibit 10 above—Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline, East Siberia-Pacific Ocean Pipeline, Goreh-Jask Pipeline, OCP Pipeline, Atasu-Alashankou Pipeline, and Myanmar-China Oil Pipeline—yield an average completed cost of about $3.5 million per km. Assuming a route on the order of 3,500 km linking coastal Iran to China’s western border in Xinjiang, this would imply a capital cost of at least $12 billion for a single line with 1 to 1.5 million barrels per day of capacity. This in turn would imply that a corridor of four such lines capable of meaningfully offsetting China’s maritime oil import dependence could cost $50 billion just to get oil to the Xinjiang border. The corresponding domestic infrastructure expansion necessary to actually get the oil to refineries could realistically double that cost.

Taking the simple average of these three lines’ transportation costs—about $0.85 per bbl per 100 km moved—and applying it to a roughly 3,500km pipeline from Gwadar, Pakistan to Turpan, China would suggest a transport tariff approaching $30/bbl. Maritime transport from the Persian Gulf to China typically costs closer to $2/bbl. Conservatively assuming a transport cost premium of $25/bbl, this means that a 5 million bpd line operating at full capacity would effectively impose an annual tax of nearly $46 billion on Chinese oil consumers—equal to about 18% of China’s total crude petroleum import bill in 2021.

Russia’s Eastern-Siberia-Pacific Ocean Pipeline (ESPO) offers a second example and one that might be more illustrative of the costs if China undertook the highly unlikely choice of building a pipeline route from the Persian Gulf into Turkmenistan along its existing natural gas import pipelines. ESPO traverses nearly 5,000 km from the East Siberian city of Taishet to the Pacific Ocean port of Kozmino, with a spur line delivering oil south to China.

ESPO had to be built in a remote environment with severe climate, but fewer topographical and seismic challenges than a trans-Himalaya route would face. It cost more than $20 billion (roughly $4.5 million per km). As such, its construction costs were about 12.5% higher per km compared to what China’s three large gas import pipelines from Central Asia cost. The costs were about 2.5 times higher per kilometer than Iran’s Goreh-Jask Pipeline.

Russian pipeline operator Transneft charges a tariff of approximately 2,969 rubles per tonne ($3.79/bbl) for oil delivered to the Chinese border ($0.08/bbl/100km moved).[27] Here it’s worth noting that when Russia began pipeline oil shipments to China in 2011, a USD was on average worth about 30 rubles. The rate in early March 2022 is closer to 110 rubles per USD as Putin pursues Ukraine’s subjugation. As such, a Chinese-financed line paid for either in USD or RMB whose value remains tightly linked to the dollar would likely have a tariff that in dollar terms could be 3.5 times the Transneft ESPO tariff, implying a rate on the order of $0.30/bbl/100km or $10.50/bbl to transport oil from the Persian Gulf region to Xinjiang and a similar cost to reach refineries in the Shanghai area or Qingdao. Five million barrels per day of oil delivered at a transport cost of $21/bbl would mean an annual cost of $38 billion—likely 10 times what it would cost to bring the oil by tanker.

Seaborne oil import facilities are generally more cost-effective than pipelines because the builder does not have to pay for the steel vessel that moves the oil from producer to the offload point. Consider the following: Huanghua Port near the city of Cangzhou along the Bohai Gulf is presently constructing an oil berth capable of accommodating 300,000 deadweight ton supertankers. The facility will be able to offload 13 million tonnes of crude annually (about 260,000 bpd) and cost approximately 3 billion RMB (approximately $460 million at a 6.5 RMB/USD exchange rate, or half what the Kazakhstan-China Oil Pipeline cost to deliver a similar average volume).[28] Furthermore, oil ports have the added bonus of being able to import crude from any exporter on earth that can access tidewater.

Vulnerability of Pipelines

Pipeline present three prominent vulnerabilities. First, projects such as the Myanmar-to-China pipeline or a hypothetical Pakistan-to-China pipeline are not overland per se, but rather maritime chokepoint bypasses that must still receive inbound tankers. They therefore would concentrate the target set for an adversary seeking to disrupt oil shipments to China.[29] Interdiction could take the form of a naval blockade, kinetic strikes against the unloading terminal and associated pumping facilities, or denial of access through standoff mining using munitions such as the Quickstrike-ER sea mine.[30]

Second, even fully inland pipeline infrastructure is vulnerable to attack. In some instances, attackers sabotage the line itself. Damage can often be repaired fairly quickly, but a high attack tempo of even simple assaults can cause serious cumulative loss of throughput. For instance, the Caño Limón pipeline in Colombia has been attacked more than 1,300 times during its 36 years in service and has spent at least 3,800 days offline since it entered service in 1986 due to attacks.[31]In 2013 a series of almost daily attacks forced Colombia to reduce oil production by 35,000 bpd, a loss equal to almost 1/5 of the line’s nameplate capacity.[32] Chinese firms now grapple with a lower-intensity, but broadly similar threat in Myanmar where there have been multiple attacks against the Myanmar-China pipeline corridor over the past year.[33] The threat is still nascent, with attacks to date directed at regime soldiers guarding pipeline related facilities but could evolve into a more complex threat where anti-regime elements begin targeting the line itself as rebel groups in Colombia do.

More sophisticated attackers can cause more serious disruptions by targeting pumping stations, whose equipment is more expensive and difficult to replace than the hollow steel tube of the line itself. For example, Houthi rebels targeted two pump stations on Saudi Arabia’s strategic East-West oil pipeline with seven explosive-laden drones in May 2019.[34] The Saudi Energy Minister noted that the drones caused “a fire and minor damage to Pump Station No.8.”[35]Houthi militants often employ drones of the Qassem-1 class with a 30kg warhead for these types of attacks.[36] As knowledge of how to make and operate such low-cost, high-impact munitions proliferates, security risk to key overland energy transit facilities in and near restive areas rises.

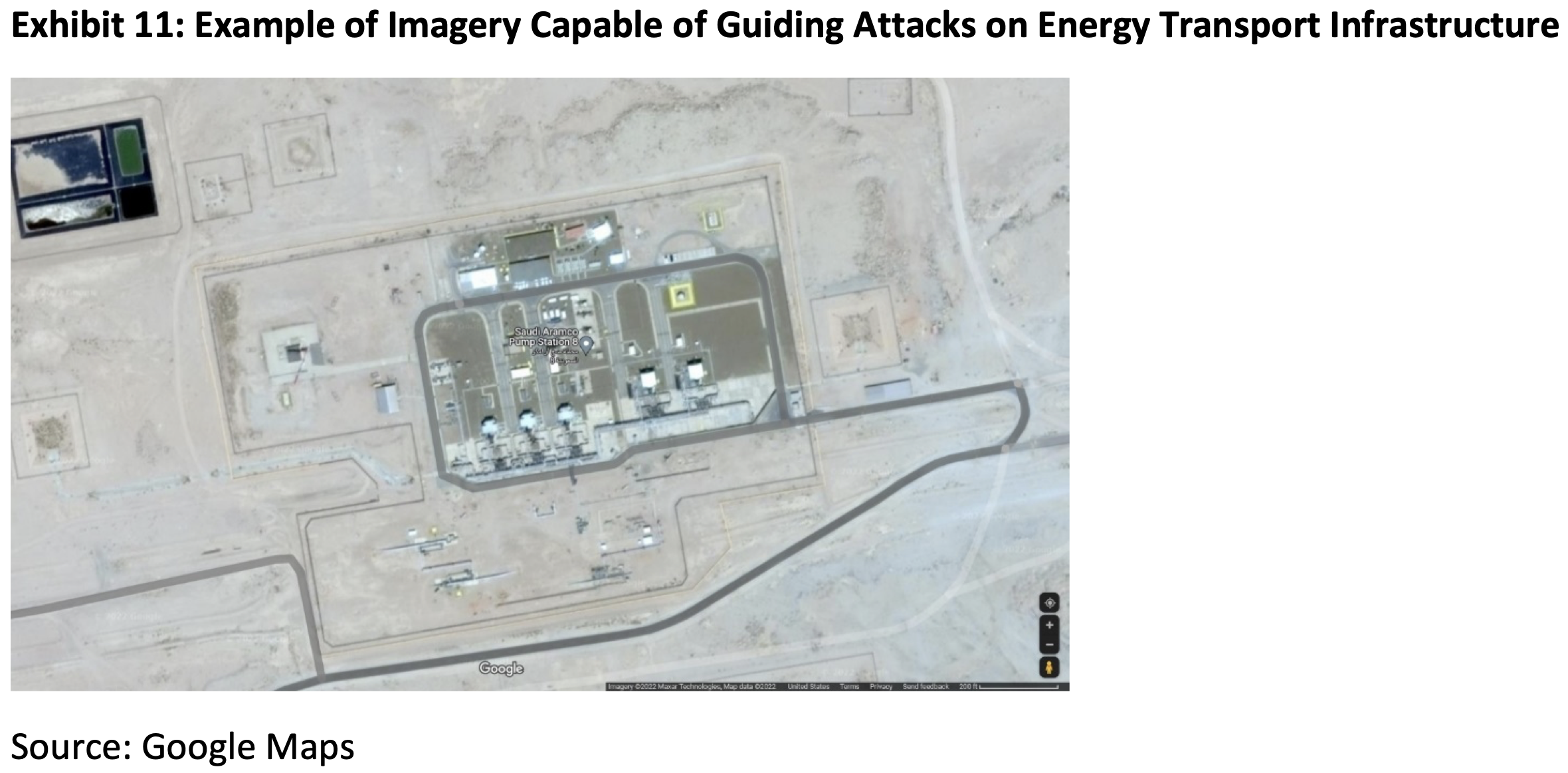

In the Houthi case, a non-state actor was able to strike and damage assets approximately 800km from the Yemeni border (assuming launch from within Yemen). Furthermore, relatively high-resolution imagery now exists of pipeline pumping stations and other energy transport facilities that is sufficiently accurate to program UAV loitering munitions’ guidance and navigation systems. As an example, consider Exhibit 11 which shows Saudi Aramco’s Pump Station Number 8 and was pulled directly from freely available Google Maps imagery.[6] Deriving precise latitude/longitude data from such imagery software is straightforward. Facilities vulnerable to non-state groups with drones would be even more exposed to modern national militaries, who could target key facilities in remote, sparsely populated areas and rapidly disable pipelines carrying oil or gas into China.[37] Cyberattacks are also a key risk from both state and non-state actors, as the roughly weeklong disruption caused by a ransomware attack on the vital U.S. Colonial Pipeline demonstrated in 2021.[38]

Exhibit 11: Example of Imagery Capable of Guiding Attacks on Energy Transport Infrastructure

Source: Google Maps

Pipelines’ fixed nature also makes them proportionally more vulnerable to natural disasters than maritime shipping. Routes traversing mountain ranges such as the Andes or Himalayas are especially vulnerable given the risk of landslides and seismic activity.[39] Indeed, in December 2021 a landslide damaged the Trans-Ecuador Pipeline and forced a multiday shutdown.[40]Routes crossing Central Asia might generally be less vulnerable given that many of those cross open steppe, but any route between Pakistan and China would have to cross seismically active mountains with severe, landslide-prone topography.

Handling Disruptions and Military Defense of Energy Sources and Transit Routes

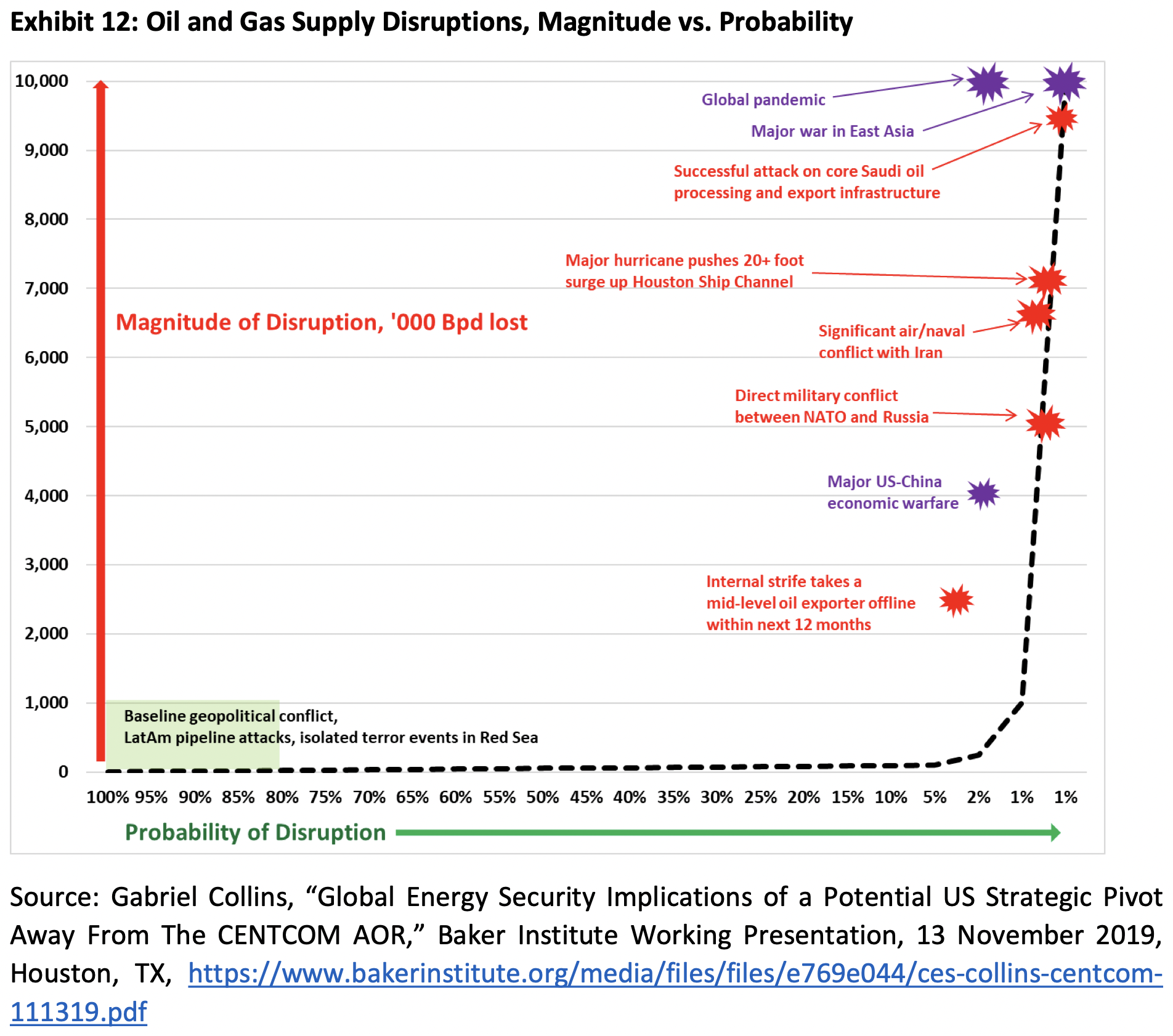

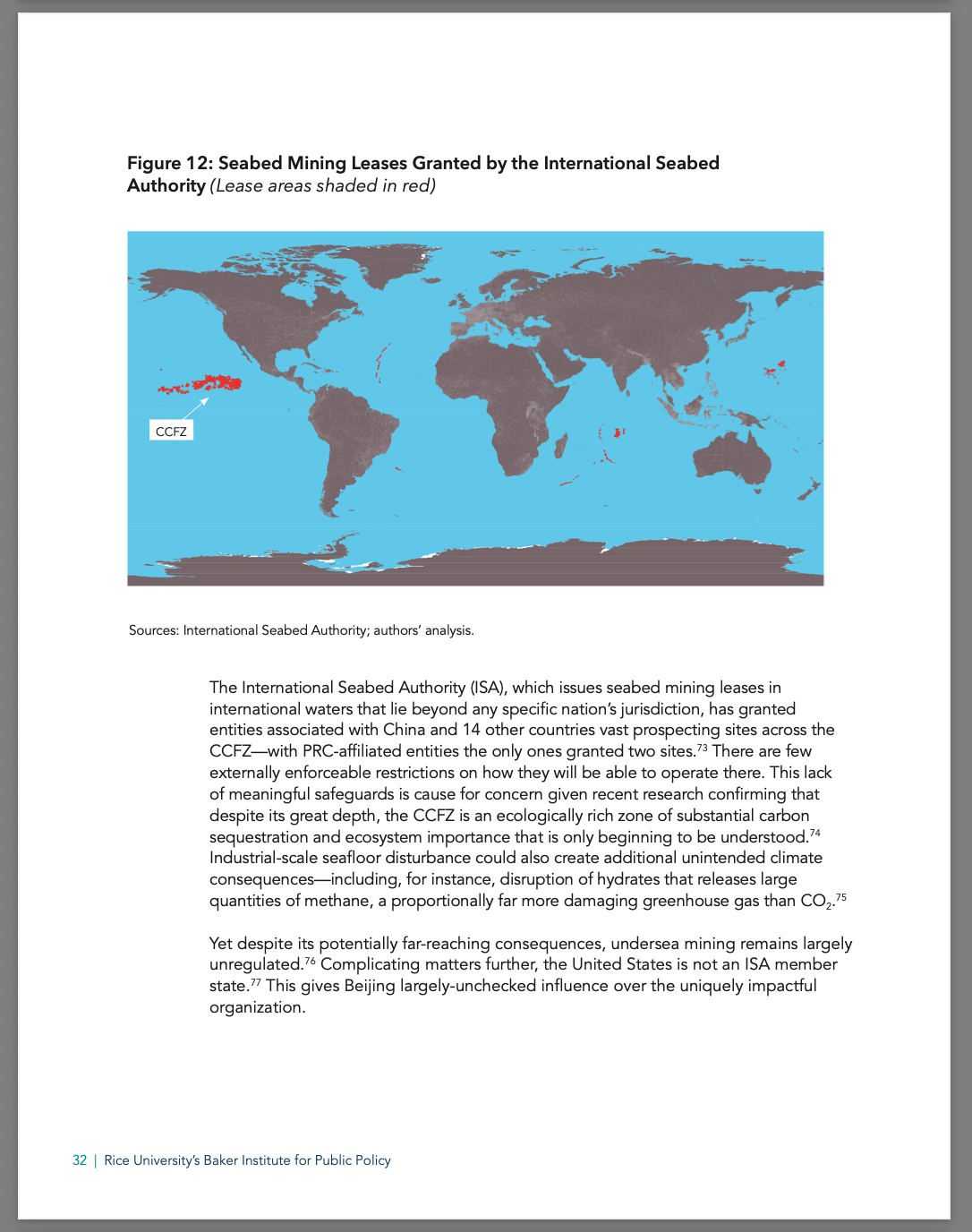

In thinking about maritime trade versus overland pipelines, three core themes arise. The first entails assessing the impact of various disruptive threats upon either the supply of, or demand for, crude oil and natural gas. The second centers on the probability of the event (Exhibit 12). Third is how to best protect oneself via proactive and reactive countermeasures.

Exhibit 12: Oil and Gas Supply Disruptions, Magnitude vs. Probability

Source: Gabriel Collins, “Global Energy Security Implications of a Potential US Strategic Pivot Away From The CENTCOM AOR,” Baker Institute Working Presentation, 13 November 2019, Houston, TX, https://www.bakerinstitute.org/media/files/files/e769e044/ces-collins-centcom-111319.pdf

Potential responses to naval blockades, hurricanes, pirates, producer country instability, and complex market environment threats such as the uncertain state of affairs and price spikes after Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine sometimes overlap but can also differ substantially. Many potential threat events—including some of the highest impact ones—do not have a military solution, as the world learned from the covid-19 pandemic, for instance. This section will examine how China is postured to handle various types of oil and gas supply disruptions.

Other disruptors, such as naval blockades, may require direct military engagement. Still others, such as piracy, producer country internal problems, and maintaining security of maritime transit lie on a spectrum in between, where kinetic power projection is important, but the necessary degree can vastly differ. For instance, security teams embarked on tankers can repel pirates whereas attacks by nation-states on oil and gas production areas or transit routes via blockade/interdiction campaigns often require high-end combined arms capabilities to deter or defeat.

Accordingly, a three-part taxonomy helps classify Chinese energy security (i.e. oil and gas import security) actions. Some clearly stand apart, while others are mutually reinforcing. Category one encompasses market-oriented solutions including supply diversification, expansion of storage, and longer-term demand management approaches such as transport electrification. Category two covers “hybrid” solutions such as state-flagging of oil tankers and deployment of private security firms to defend resource producing assets or transport supply lines that layer implied or actual kinetic protection capacity atop commercial activity by private or quasi-private actors but doing so short of explicit military involvement by China’s armed forces. Category three involves direct deployment of the PRC government’s nation-state diplomatic and military capacity.

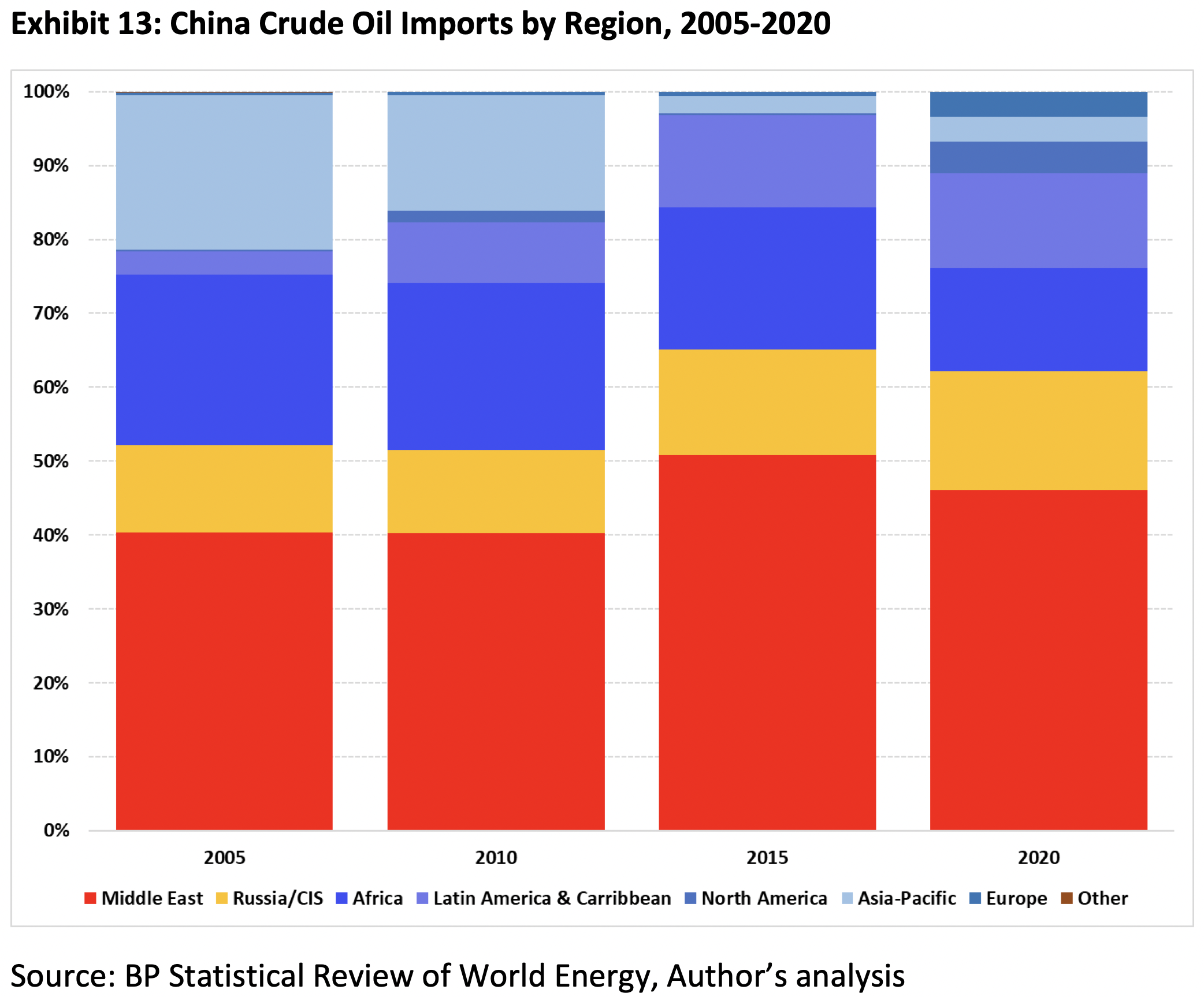

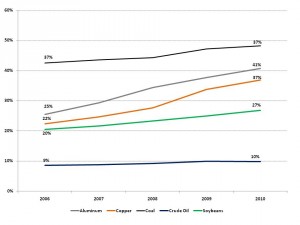

Market-Oriented Solutions

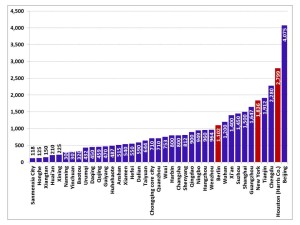

Chinese crude oil and natural buyers have worked to try and diversify their supply sources for many years now. Oil has been the primary focus, given that it remains largely without substitutes as a transport fuel and because efforts to increase domestic supplies have faltered. China’s oil imports more than tripled between 2005 and 2020 and the supplier base has been diversified during that time. But one thing has remained constant—a high dependence on the Middle East, which in 2020 accounted for close to half of China’s oil imports (Exhibit 13). Middle Eastern supplies are unique because they concentrate both producer country risk (key fields geographically close to each other) and transit risks (shipments must transit either the Strait of Hormuz or the Red Sea.

Exhibit 13: China Crude Oil Imports by Region, 2005-2020

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, Author’s analysis

Diversification helps insulate an importing country from potential coercion by specific exporter countries or small subsets of them. What it does not do is protect against price spikes caused by removal of oil supplies from the global market, whether the shortfall results from purposeful action like an embargo or attack, or unexpected outages—like an industrial accident at a major oilfield or export facility. Protection against such events comes through two primary pathways: (1) the cushion provided by inventories and (2) policies to manage demand and reduce an economy’s oil intensity per unit of output.

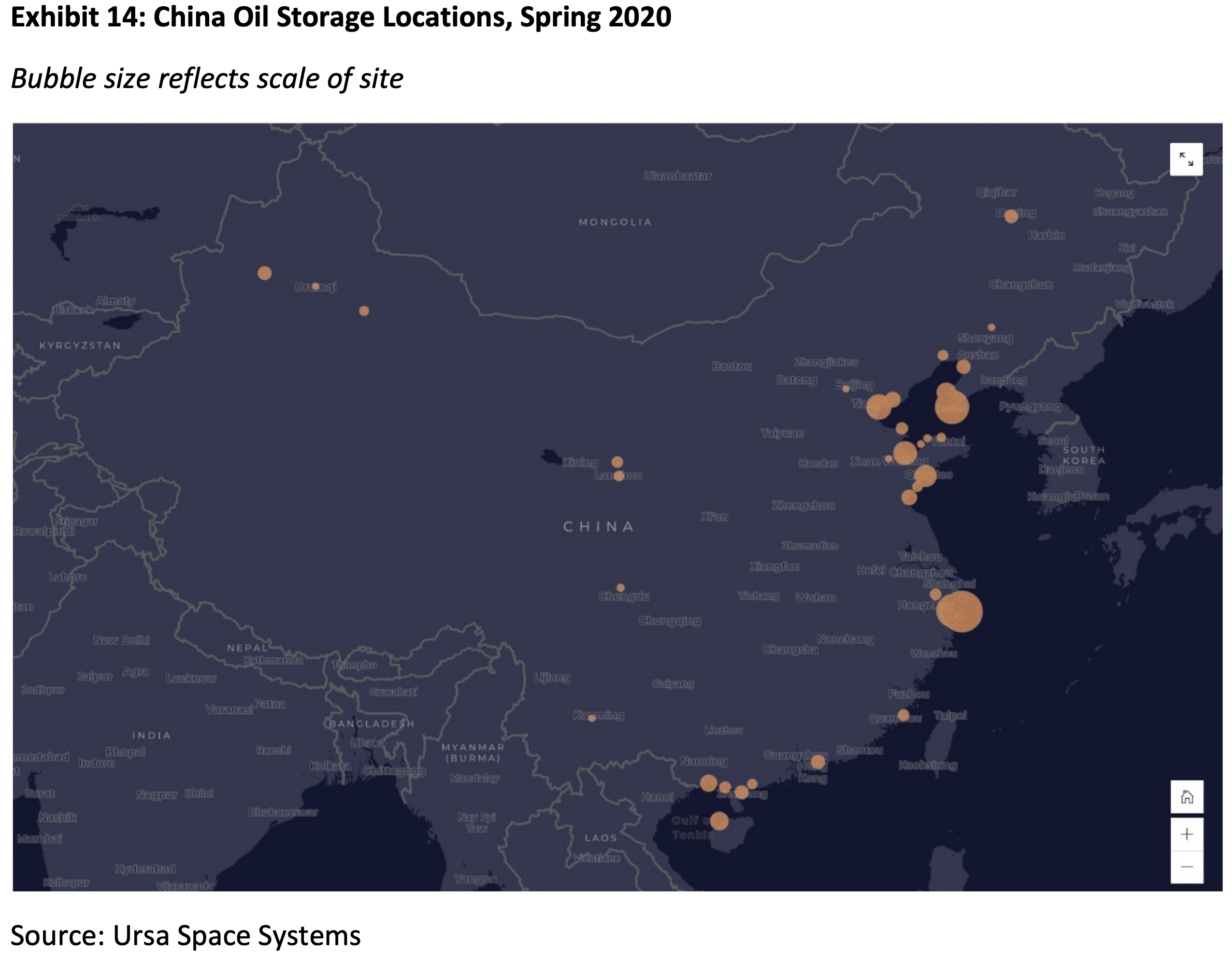

China now has more than 1.3 billion barrels of total oil storage capacity, of which approximately 400 million barrels resides in government strategic petroleum reserve sites (Exhibit 14).[41] The largest storage bases are located near key oil ports and major refining centers. The smaller dots in far Northeast China, far Western China, and Yunnan are all associated with oil import pipeline routes (as well as adjacent domestic production).

Exhibit 14: China Oil Storage Locations, Spring 2020

Bubble size reflects scale of site

Source: Ursa Space Systems

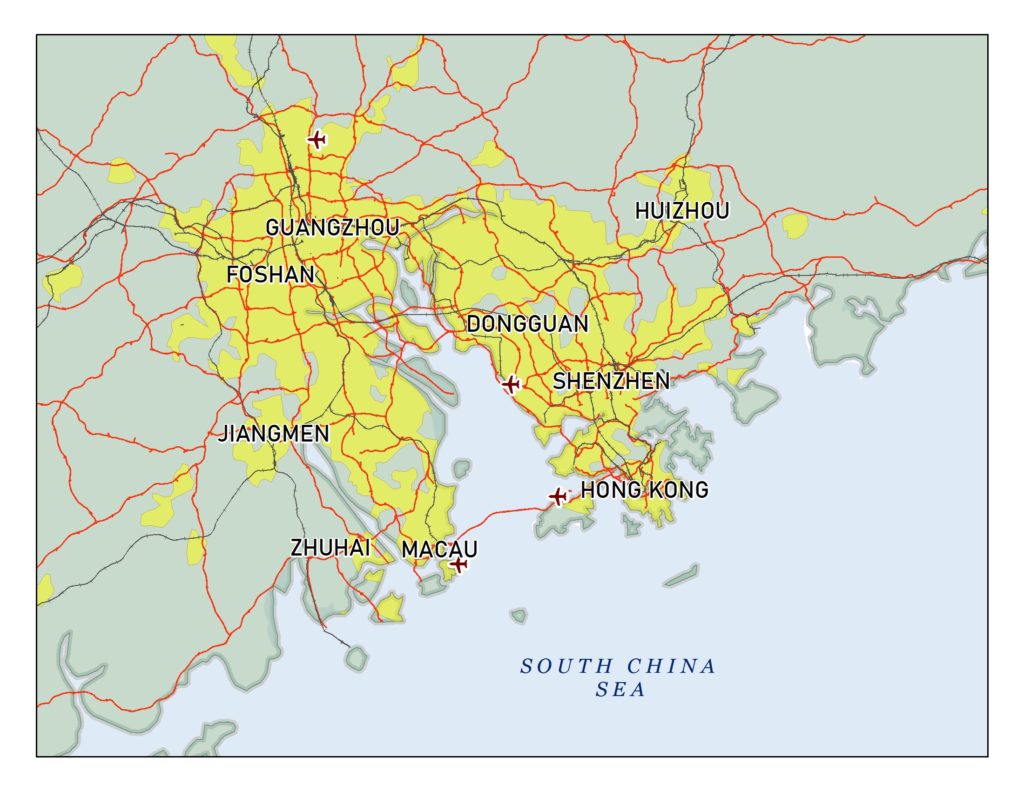

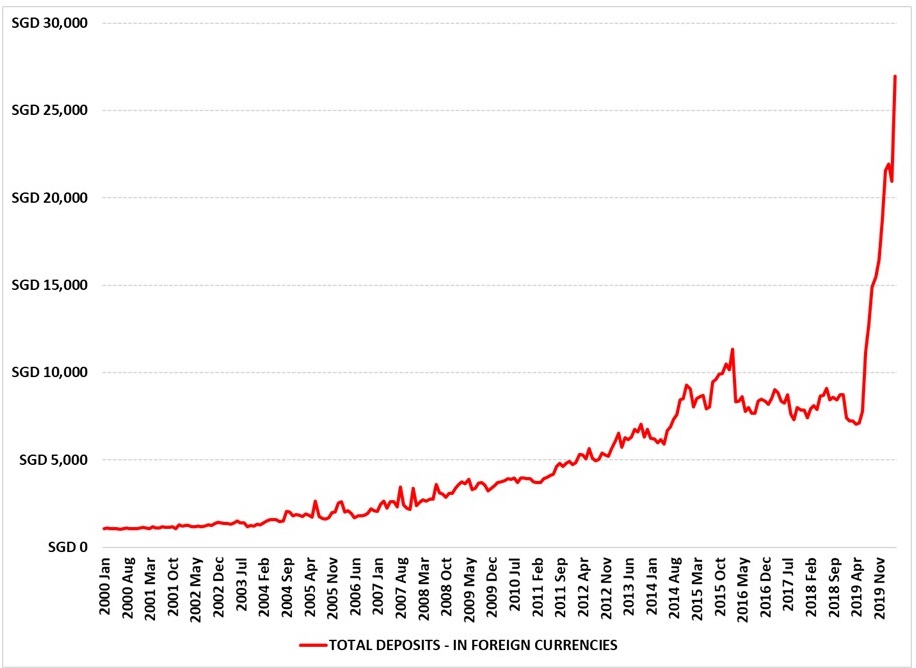

For perspective, U.S. commercial crude oil storage capacity in 2021 was approximately 840 million barrels, plus 727 million barrels of strategic petroleum reserve capacity run by the Department of Energy.[42] As of 4 March 2022, commercial crude oil and SPR storage across the U.S. held a combined total of 989 million barrels.[43] Data vendor Kayrros estimates that as of late February 2022, China’s total crude oil inventories were approximately 950 million barrels—92 days of import coverage at 2021 intake rates.[44] As such, although China is not a member state of the International Energy Agency (IEA), its crude oil inventory holding level is now in line with the IEA’s requirement that each member country “hold emergency oil stocks equivalent to at least 90 days of net oil imports.”[45]

The author’s prior research indicates that at multiple key Chinese oil storage locations, utilization rates between late 2016 and early 2019 were typically between 50% and 70% of nameplate capacity.[46] U.S. commercial crude oil storage facilities show similar usage patterns between 2011 and 2021.[47] Having some degree of “headroom” in the national oil storage tank fleet suggests that if circumstances warranted, oil inventories could increase substantially beyond present levels. Indeed, oil inventory data observable from space provide a key strategic warning indicator of potential PRC military action against Taiwan.[48] China is also constructing subterranean rock caverns for oil storage—with the 19 million barrel Huangdao site in Shandong online and several other locations either online or under construction.[49] Underground sites can be cheaper to build in areas with high land costs and also offer far more protection against precision guided munitions strikes in the event of a conflict, unlike surface oil tanks that are readily broken open and ignited.

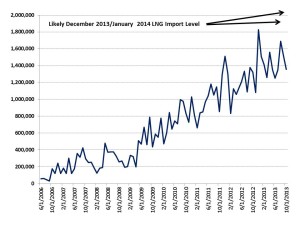

China’s natural gas storage is much less developed than its crude oil inventory sector is. The country had 14.5 billion cubic meters of working gas space at year-end 2020, according to CEDIGAZ.[50] At the 2020 demand level of 330 BCM, this means China has about 16 days of working gas inventory. For comparison, the United States has approximately 137 BCM of working gas storage capacity against 2020 demand of 832 BCM, implying a storage cushion of closer to 60 days.[51] It is thus likely that if China continues to become more dependent on natural gas, the government will encourage firms to expand storage capacity. Gas storage in China may also assume a different form than is the case in the U.S., for instance. At least one company, CNOOC, appears to be “oversizing” the cryogenic storage tanks at one of its LNG import terminals with largest of kind tanks that can literally each hold the entire capacity of a Q-Max LNG tanker—the world’s largest.[52]

China also has options for “stretching” its existing crude oil and natural gas inventories. Fundamentally, there are proactive options— using fuel pricing to manage demand in the near-term and transport electrification over the medium and long-term—as well as the “reactive” option of demand rationing in the event of a severe disruption. For natural gas, the country can throttle up coal-fired power plants to increase electricity supplies. This option is already in use and appears poised to accelerate as the energy crisis of 2022 continues to unfold.[53] Vice Premier Li Keqiang noted at a National Energy Commission meeting on October 9, 2021 that China must maintain stable and secure energy supply chains and that this effort will include greater development of domestic coal, oil, and gas resources.[54] Just two weeks later, Premier Xi Jinping emphasized the importance of energy security, telling workers at the Shengli Oilfield that China must “ensure that its energy livelihood remains in its own hands” (能源的饭碗必须端在自己手里).[55]

Fuel Pricing

Fuel pricing can be used as a mechanism for managing demand and encouraging more efficient energy consumption behaviors. In parts of Europe, for instance, motor fuels are taxed at very high rates to encourage greater fuel-efficiency in vehicles and use of public transport or non-petroleum powered modes of transportation (bicycles, walking, etc.). In China’s case, the National Development and Reform Commission sets gasoline and diesel fuel prices.

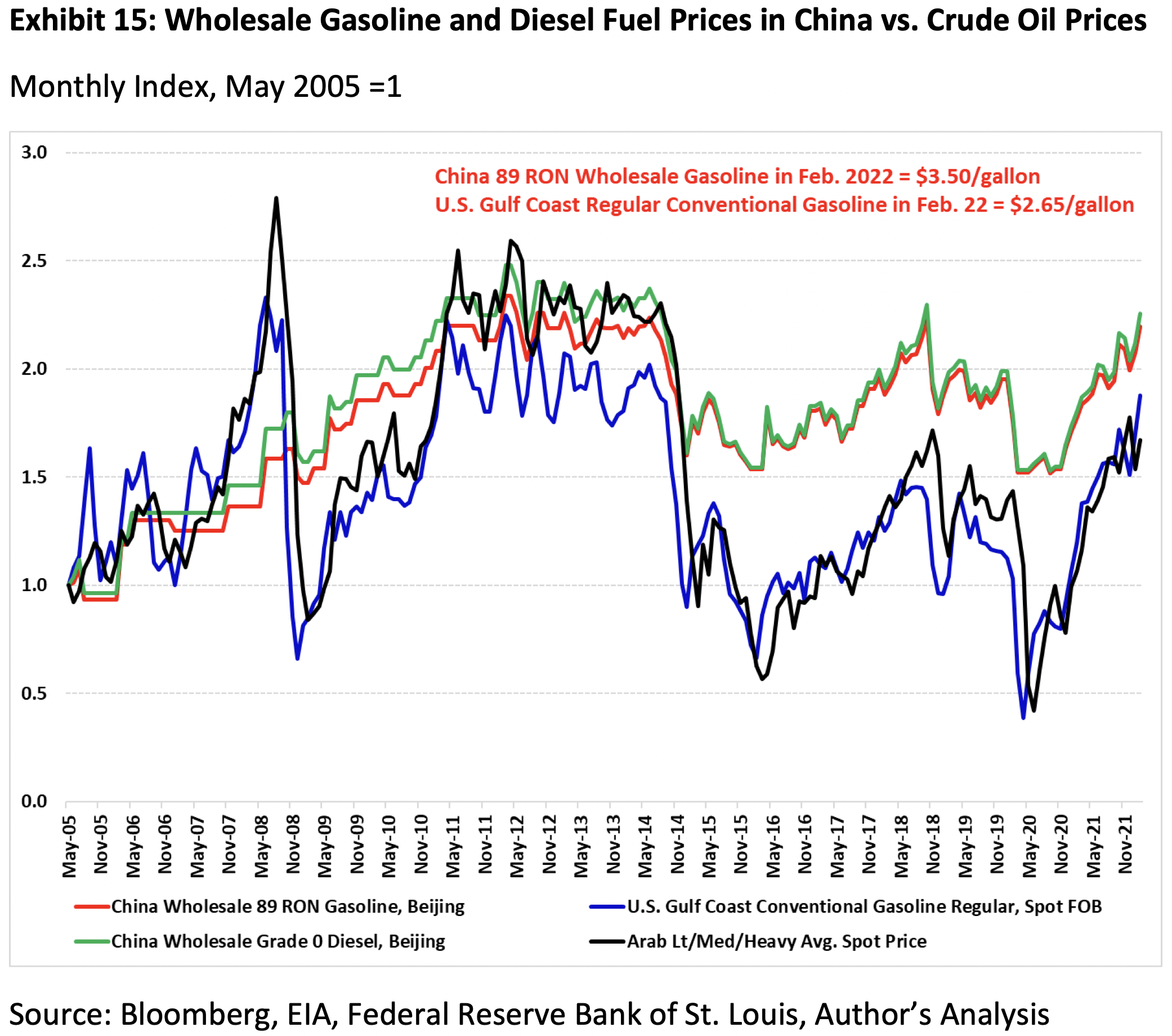

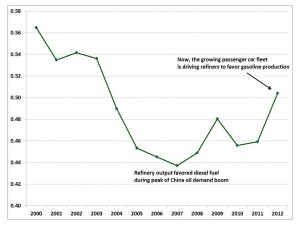

In the mid-2000s, prices tended to stay fixed for periods of many months and often not only lagged behind crude oil price movements, but also undershot them as the Chinese authorities sought to minimize impacts on consumers. The 2010-2014 period saw the wholesale prices of gasoline and diesel begin to track international crude prices more closely and from 2014 onwards the alignment of price movements has been tight (Exhibit 15).

Exhibit 15: Wholesale Gasoline and Diesel Fuel Prices in China vs. Crude Oil Prices

Monthly Index, May 2005 =1

Source: Bloomberg, EIA, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Author’s Analysis

The NDRC pricing mechanism states that if international oil prices change by more than 50 RMB/tonne (about $1/bbl) and remain at that level for 10 working days, oil products prices will be adjusted in accordance.[56] But while China’s official price setting tracks relative global crude price movements, it does not accurately track their absolute level. In fact, for 7 years and running, both gasoline and diesel prices in China have consistently exceeded their U.S. counterparts by a substantial margin. While U.S. Gulf Coast gasoline spot prices closely track the relative movements and absolute levels of key global crude oil benchmarks, China’s wholesale gasoline price presently exceeds that of its U.S. counterpart by nearly 1/3. A plausible explanation is that the NDRC prefers to keep gasoline and diesel prices high to restrain oil demand growth, promote efficiency, and perhaps also make electric vehicles more attractive to Chinese consumers.

Transport Electrification

China’s historical position vis-à-vis the nexus of transportation and energy has been one in which supply insecurity motivated strategic thinking. On the national security side of the ledger, reducing crude oil import dependency could confer significant strategic benefits. Chinese leaders have long worried that in a conflict, an opposing navy could interdict oil shipments to China via a so-called distant blockade. Even if such a campaign ultimately failed to force China’s capitulation in a conflict, it would very likely cause the country substantial transport disruptions and economic damage.[57] Policies such as vehicle electrification that eventually drive down crude oil dependence can help address these deep-seated strategic concerns by making oil imports a less attractive strategic pressure point for potential adversaries. There is also a financial dimension. With China now importing more than 3.5 billion barrels of crude oil per year, the expenditures are significant—with a dollar price tag second only to that incurred from semiconductor imports.

Finally, China’s industrial policy seeks to make electric vehicles an area of global competitive advantage. The Made in China 2025 concept specifically names “new energy vehicles” as one of 10 priority sectors.[58] The State Council’s New Energy Vehicle Development Plan 2021-2035 articulates EV development and market penetration in holistic terms, noting that policymakers aim to encourage broad collaboration and synergistic activities invoking not just the auto industry, but also the energy, transport, and IT sectors.[59]

Transport electrification, however, allows China an opportunity to harness industrial prowess and a unique hardware + software domestic tech development ecosystem to gain technological first mover advantage, and have a real shot at becoming the prime global market shaper in a manner that was simply never possible with petroleum-based transport fuels and technologies. Indeed, the 15-year new energy vehicle plan released by the State Council in November 2020 emphasizes the “promotion of integrated industrial development” (推动产业融合发展).

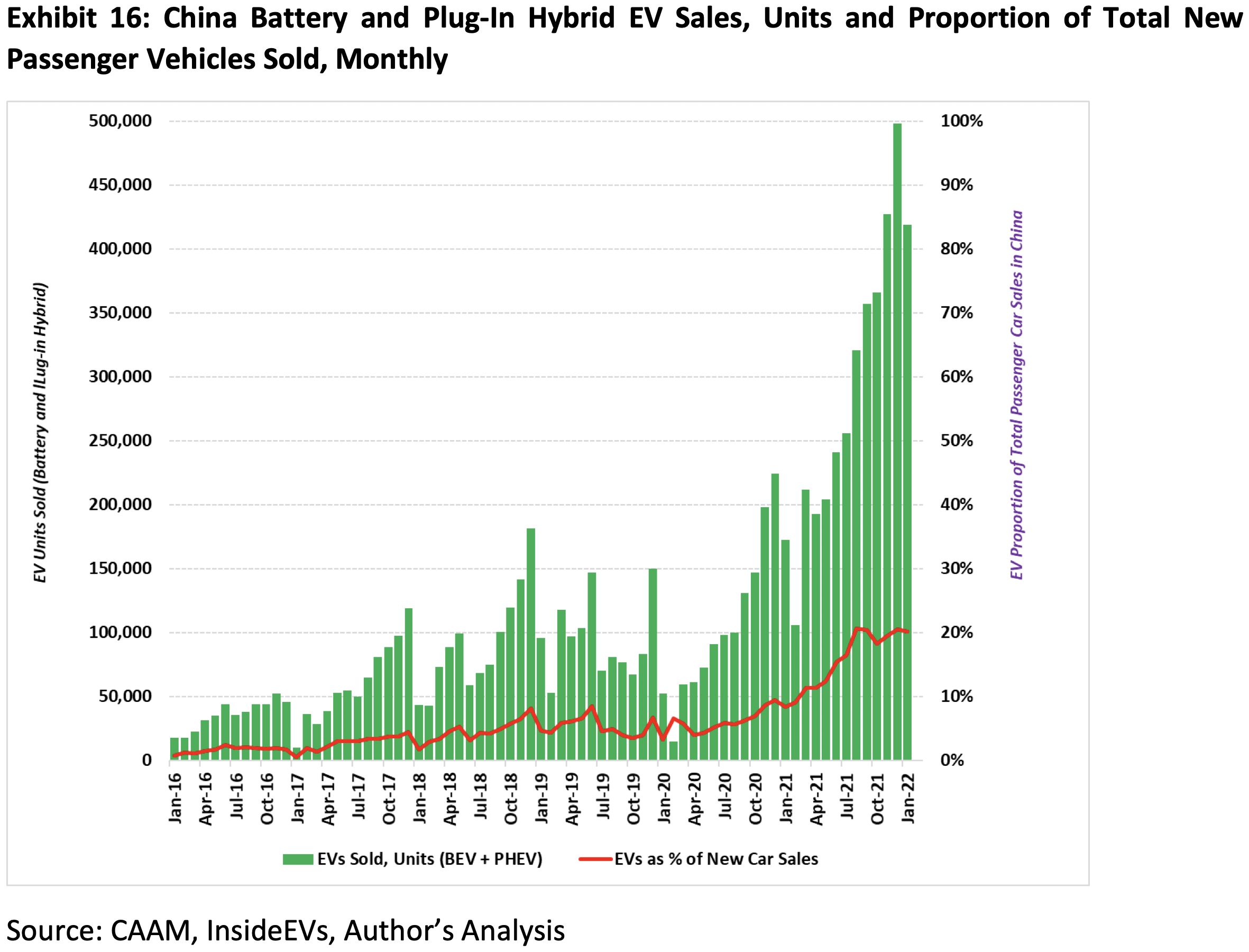

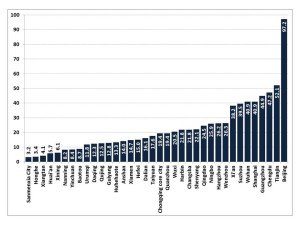

The State Council’s “Energy Conservation and New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan for 2012-2020” [节能与新能源汽车产业发展规划 (2012-2020年)], which was published in July 2012, laid out these policy goals as well as a set of concrete numerical targets. Most specifically, the document sought to have China achieve production and sales of 500 thousand battery and hybrid-electric vehicles per year by 2015 and 2 million units per year by 2020. China’s automakers fell just short in 2020, but saw a dramatic 2021 in which 3.3 million battery EVs and plug-in hybrids were sold by Chinese firms, with about 500,000 of these destined for export markets (Exhibit 16). The EV sales proportions reached in late 2021 are well-aligned with the target established in the State Council’s New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan for 2021-20135 [新能源汽车产业发展规划(2021-2035年)], which seeks to have battery and plug-in hybrid vehicles comprise 20% of total new vehicle sales by 2025.

Exhibit 16: China Battery and Plug-In Hybrid EV Sales, Units and Proportion of Total New Passenger Vehicles Sold, Monthly

Source: CAAM, InsideEVs, Author’s Analysis

China’s EV fleet is growing quickly and approximately 8 million vehicles have been sold (versus a total passenger vehicle fleet of 225-235 million units). Rapid EV expansion does not yet appear to have significantly cut into gasoline or broader transport fuel usage. Norway offers a rough yardstick because it has one of, if not the, largest global EV vehicle fleet share.

Data from Statistics Norway allow a small temporal snapshot between 2016 and 2020, with 2019 being the most representative year since it did not suffer pandemic impacts to fuel demand patterns. In 2019, sales of diesel fuel—the largest fuel source for Norway’s car fleet—fell by about 3% year-on-year after posting a slight increase in 2018.[60]Gasoline sales declined by 5.5% YoY, an acceleration from 2018, when they declined by 3%. Battery EVs and plug-in hybrids accounted for about 13% of the Norwegian passenger car fleet in 2019. China will need 30-35 million EVs to reach the same fleet proportion that Norway attained in 2019, suggesting that EVs as a demand management strategy still have a long way to go before they impact oil demand sufficiently to relax policymakers’ concerns about oil import dependency.

Rationing

In the event of a severe oil supply disruption imposed on China specifically (i.e. an oil blockade) rationing could significantly extend inventory life. The author calculated in a 2018 study of how China might respond to a maritime oil blockade that if China was cut off from seaborne oil imports but did not implement rationing, inventories would last approximately 3 months. The numbers would be broadly similar today. Rationing substantially extended inventory life, as a 35% demand reduction would extend inventory life to 10 months and a 45% demand reduction would stretch stock life to nearly 2 years.[61] There is a historical precedent for such drastic action during a time of conflict. Between 1941 and 1944, the United States used a mix of voluntary and compulsory measures to decrease private and commercial highway gasoline consumption (i.e., transportation-driven gasoline demand) by 32 percent.[62]

Hybrid Solutions

Maritime transportation of oil to China, especially if carried in tankers owned or chartered by PRC firms, may lend itself to intermediate protection options. Specifically, tankers can be PRC-flagged and if necessary also embark armed security teams from PRC private security firms. The issue deserves close attention because PRC oil trader Unipec has for multiple years been the world’s largest charterer of very large crude carriers (a/k/a “supertankers”) and in 2021 chartered more VLCCs than the next five charterers combined.[63]

State-flagging tankers is fundamentally a deterrent strategy for situations of heightened tensions but short of full-scale war. A PRC-flagged tanker in government service would enjoy the substantial protection of China’s flag. If an outside power interdicted such a vessel, China would have grounds to claim a sovereignty breach that could justify an armed response.[64] The fact that China’s main oil trading firms are parastatal and are substantially owned/controlled by the PRC government would introduce some degree of ambiguity as to whether a vessel was in “government service” but if Beijing needed to make the argument, it would likely be relatively straightforward. The result is, as we put it nearly 15 years ago an escalatory barrier that “would thus deter adversaries from interdicting PRC oil shipments unless hostilities were either imminent or already underway. It is difficult to imagine a scenario short of major war in which an adversary would risk triggering escalatory behavior by Beijing.”[65]

If Chinese interests wished to augment protection for energy shipments—likely against non-state actor threats—but without incurring the potential diplomatic and economic costs of a military deployment that would be overkill relative to the problem, they could hire from the PRC’s burgeoning private security sector. Embarking armed personnel on ships would reap the bonus of credible protective capacity while minimizing the legal, diplomatic, and practical liability onus that arises when deploying private security forces ashore.[66]

China’s domestic private security contractor (PSC) scene has burgeoned, with one analyst estimating that more than five thousand domestic PSC’s in China employ at least three million people.[67] Yet their overseas operational footprint remains small and Chinese law restricts them from conducting armed missions.[68] Moreover, even if this restraint were removed, Chinese PSCs are very different than their competitors from the United States, the Former Soviet Zone, and other jurisdictions with a substantial supply of highly-trained and combat-hardened ex-military personnel. For the meantime it is therefore likely that even Chinese-flagged vessels needing armed protection short of direct military escort would hire contractors from other countries.

- Military Defense of Energy Sources and Transit Routes

Chinese analysts fall into two basic camps, which Zha Daojiong characterizes as “globalists” who favor greater reliance on the market and accelerated energy transition efforts to reduce oil dependence and “nationalists” who favor a more forward-leaning mercantilist posture to protect China’s energy security, which is synonymous with oil and gas import dependence.[69] Many of China’s national-level approaches to date, including maximizing supply diversity, expanding oil storage, solidifying PRC firms’ global presence in key oil procurement and trading nodes, managing domestic demand through fuel pricing, and aggressive pursuit of transport electrification emphasize market reliance with an undercurrent of mercantilist state industrial policy.

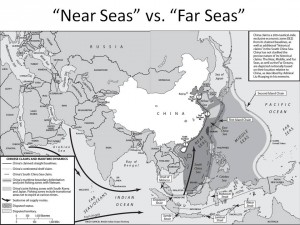

A key question thus remains and the potential answers to it regularly and dynamically evolve: to what extent, if at all, are energy security concerns shaping China’s military development? At present, capabilities are growing but do not appear to be driven by a specific mission focus on energy security. Chinese ground forces are not oriented toward large-scale foreign deployments nor are its air assets, perhaps beyond heavy lift assets useful for evacuating Chinese citizens from distant conflict zones.[70] For naval force modernization and posture, the energy security question is more pressing. Ultimately, seapower is highly fungible and oil/gas import security likely comprises an incremental subset of what has become a broad array of potential “far seas” missions for the PLA Navy.

Examining a historical archive of China Defense White Papers dating from 1995 to 2019 supports such a holistic view. The term “energy security” first appeared in the 2004 edition, the same year China’s oil imports ballooned.[71] The 2006 White Paper noted that concerns about energy resource security (along with multiple other non-traditional security threats) were mounting.[72] The 2008 and 2010 White Papers used similar language. The 2019 White Paper offers more nuanced views that likely more accurately reflect leadership thinking about the intersection between naval power and commerce protection, noting that with respect to China’s overseas interests “The PLA conducts vessel protection operations, maintains the security of strategic SLOCs, and carries out overseas evacuation and maritime rights protection operations.”[73]

How recognition translates into reality on the ground (and more importantly, at sea) remains to be seen. China is clearly building naval forces capable of operating further afield. The PLAN is now building its third aircraft carrier, one that will be closer in size and operational orientation—including catapults—to U.S. carriers.[74] It has also launched a total of at least 25 Type 052D destroyers and at least eight Type 055 cruisers, each of which could project serious combat power far from China’s shores.[75] It has also commissioned 10 amphibious ships (8 X Type 071 and 2X Type 075) with more on the way.[76] Watching the construction of these vessel types plus the necessary logistics ships to support them offers a key strategic warning indicator.

China’s quantitative and qualitative improvements to its naval forces, and indeed across its military services, have been impressive in recent years. But it is also worth bearing in mind that seeking to protect energy shipments coming from far overseas ultimately means seeking to contest control of the global commons. As Barry Posen of MIT puts it:

“The specific weapons and platforms needed to secure and exploit command of the commons are expensive. They depend on a huge scientific and industrial base for their design and production … The development of new weapons and tactics depends on decades of expensively accumulated technological and tactical experience embodied in the institutional memory of public and private military research and development organizations. Finally, the military personnel needed to run these systems are among the most highly skilled and highly trained in the world. The barriers to entry to a state seeking the military capabilities to fight for the commons are very high.”[77]

Whether China wants to take this challenge on is far from clear, given the potential distraction from the core strategic priorities of re-incorporating Taiwan and establishing control over the country’s adjacent maritime environment. Furthermore, the PLA Navy would likely need to expand further precisely as the bulge of naval vessels it acquired in the mid-2000s are now reaching midlife and likely becoming more expensive to sustain.[78] It would also require significantly increasing China’s basing and access footprint across the Middle East and Indian Ocean Region.[7] China presently has one permanent base—a facility at Djibouti with an approximately 400-meter runway. In contrast, the U.S. maintains access to dozens of sites in the region, with runways able to handle any aircraft in the inventory and full basing abilities (including munitions storage, repair, and host country approval for kinetic operations) at multiple of these across several countries.

The U.S. Gulf Region experience is not definitive for what China might face but offers useful insight into the time it takes to build a credible, comprehensive security presence in oil and gas-exporting areas, the number and types of capabilities and platforms for handling various situations, and the potential cost to combat power in other theaters of interest. Diplomatic relationships, the base facilities and access that resulted from them, and the force deployments dedicated to the region cost decades of time and hundreds of billions of cumulative dollars—not including wars.

The U.S. presence in the Gulf Region commenced in the late 1940s, grew in the shadow of the dominant British role, and then assumed greater prominence after the 1956 Suez Crisis and Britain’s subsequent decolonization moves. Conjunctive diplomatic action and military deployments by the U.S. intensified in the 1960s through multiple crises.[79] U.S. policy toward the region became more explicitly securitized following the 1979 Iranian revolution and the Soviet Union’s 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter introduced the “Carter Doctrine” that came to characterize U.S. policy toward the region as it still exists today, noting that ““Let our position be absolutely clear: An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”[80]

The “Tanker War” that ensued a few years later when Iraq and Iran began firing on tankers carrying oil through the Gulf helps illustrate the potential level of military commitment that China could face, were it to become the region’s lead security guarantor. In 1984, Iraq intensified its targeting of tankers serving Iranian export facilities and Iran responded against ships carrying Iraqi oil, as well as vessels loading at Kuwait, which was using a portion of its oil revenues to support Iraq’s war effort.[81] By early 1987, the situation had escalated to the point that Kuwait sought to reflag tankers carrying its oil as American for protection. Worried that the Soviets might seize the opportunity to reflag the tankers under the hammer and sickle and project naval power directly into the Gulf, Washington swung into action and launched Operation Earnest Will to escort tankers and Operation Prime Chance, a covert parallel action to interdict Iranian minelayers and tanker assailants.[82]

Operation Earnest Will saw 13 U.S. warships deployed within the Gulf for escort missions and a total force that included a carrier battle group in the Gulf of Oman that brought the entire deployment to between 25 and 30 vessels in theatre at a given time.[83] U.S. special operations forces also deployed, with the Army’s 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (the “Nightstalkers”), Navy SEALs, Special Boat Units, Marines, other Navy personnel and two oil platform construction barges that were converted into floating sea bases.[84] Chinese forces at present would likely struggle (or even be outright unable) to sustain this level of forward deployed maritime combat power due to a combination of inexperience and lack of a well-developed logistics system. Moreover, deployments approaching this scale would materially reduce available naval combat power in East Asia, China’s priority theatre. Smaller deployments such as the ongoing anti-piracy task forces have value for “showing the flag” but offer limited capability for handling nation-state challenges that are less likely, but are the low-probability, high-impact scenario that a robust naval presence ultimately aims to insure against.

Gulf operations also wrought significant battle damage and loss of life upon U.S. forces. In May 1987, an Iraqi aircraft struck the guided missile frigate USS Stark with two Exocet anti-ship missiles, killing 37 crew members and nearly sinking the vessel. Less than a year later, the frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts hit an Iranian sea mine and was nearly lost, precipitating Operation Praying Mantis, the U.S. Navy’s largest surface engagement since World War II.[85]The PLA Navy’s battle damage management skills and the national leadership’s risk tolerance could be rapidly and severely tested if it seeks a more prominent role as a Gulf Region security guarantor.

Major forward deployments motivated by energy concerns also incur substantial financial costs, both for the directly deployed forces and for changes that may ripple through the entire force structure because of specific military commitment in energy-rich regions. And even significant force deployments still do not calm market forces. As one analyst put it, “…force projection is not a remedy for market power but a strategy to contend with its consequences.”[86] If force projection increases propensity to become involved in conflicts, costs can balloon much further—as the U.S. experienced with a multi-trillion dollar campaign in Iraq.[87]

Combining the likely capital and operational costs of Persian Gulf bypass pipelines estimated earlier in this testimony with the fact that a baseline force structure akin to that the U.S. has maintained in the Gulf Region since the 1980s could realistically cost upwards of $20 billion per year suggests that a maximally securitized Chinese oil and gas import protection policy could add $50 billion or more to the country’s annual oil import tab. Beijing would almost certainly avoid voluntarily assuming such an economic burden, especially as its economy slows and other cost centers begin to bite. The economic dynamics and political complexity of major distant force projection, plus the opportunity cost for China’s ability to generate combat power in its existentially vital home region, will likely disincentivize militarized, overland-focused oil and gas security policies.

Recommendations for Congress

Recommendation 1: Identify and monitor key warning indicators of PRC intent to try and establish greater control over key oil and gas exporting regions. Congress should consider creating an annual “China Global Energy Supply Influence Report.” The public version could assess PRC involvement in arms trade, weapons development, financial transfers to, and facilitation of corruption and/or financial influence activities in key oil and gas-exporting countries. It should also track attempts to establish military presence in these areas, particularly efforts such as those seen in the UAE and Equatorial Guinea in late 2021 that could lead to permanent forces access and presence. A non-public addendum to the report could identify targets and methods for legislative, legal, diplomatic, and if necessary, physical actions to address PRC encroachment in areas identified as key energy security interests of the United States and its allies.

Recommendation 2: Impose costs on China’s attempts to upgrade its presence in the Gulf Region, deny it hegemony over key Gulf states. Key state leaderships’ interactions with the Chinese are by all appearances more about keeping the U.S. interested and invested in the region than they are an actual attempt to trade the traditional security guarantor for a new one. U.S. presence is desirable to our partners and they want us there, but they are concerned about our level of commitment.[88]

Do not make the “Bagram mistake” of effectively abandoning high value strategic outposts. Maintain current forward presence in the CENTCOM AOR and the associated diplomatic, economic, and military equipment supply partnerships. If the U.S. were to exit certain facilities, China could gain access at relatively low cost. Conversely, to build its own basing network from scratch, it will face steep diplomatic and economic costs to construct the network and then maintain/sustain it. Finally, forcing Beijing to build its own proprietary basing network creates strategic warning indicators of Chinese intent because the necessary actions take years to unfold and are physically impossible to conceal in most cases.

Recommendation 3: Refocus U.S. high-end maritime combat power further east, build a lower-end footprint tailored to the highest-probability threats to energy flows from Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East. The transition is already well underway for 5th Fleet, with Bahrain now homeporting Cyclone-class patrol boats and two Coast Guard cutters rather than large destroyers.[89] Latin America and Africa also offer rich upside for enhanced naval presence with smaller craft that have missions distinct from their larger blue water brethren. Put more bluntly, having a DDG or guided missile cruiser hunting pirates, drug smugglers, terrorists, and confronting radical Iranian elements in the Gulf is not sensible. Performing these missions with fast, low-draft vessels of 100-to-1,000 tons displacement that can be built in the United States does make sense and preserves high-end platforms for contingencies involving China, Russia, North Korea, and the like.

Ultimately, maintaining a strong lower-end presence aligned with more unconventional threats, while being able to surge higher end forces (air and naval) as necessary in response to crises underpins longstanding relationships in key regions while minimizing opportunity costs for readiness and concentration of combat power in key zones of the Indo-Pacific.