The Conor Kennedy Bookshelf: Pathbreaking Chinese-Language Insights on Militia, Marine Corps, Military Transport, and the Belt & Road

Conor M. Kennedy is a research associate at the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI). At CMSI, his research focuses on Chinese military development and maritime strategy. He has also furnished dozens of annotated translations to support the work of analysts and decision-makers. Kennedy received his B.A. in Political Science and Chinese language from the University of Massachusetts – Amherst and his M.A. from the Johns Hopkins University – Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies, with two years’ residence in China. Immediately prior to joining CMSI, in 2013–14, Kennedy was a National Security Education Program David L. Boren Fellow to China.

PUBLICATIONS:

Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy, “Appendix II—China’s Maritime Militia: An Important Force Multiplier,” in Michael McDevitt, China as a Twenty-First-Century Naval Power: Theory, Practice, and Implications (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2020), 207–29.

APPENDIX II

China’s Maritime Militia

An Important Force Multiplier

Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy

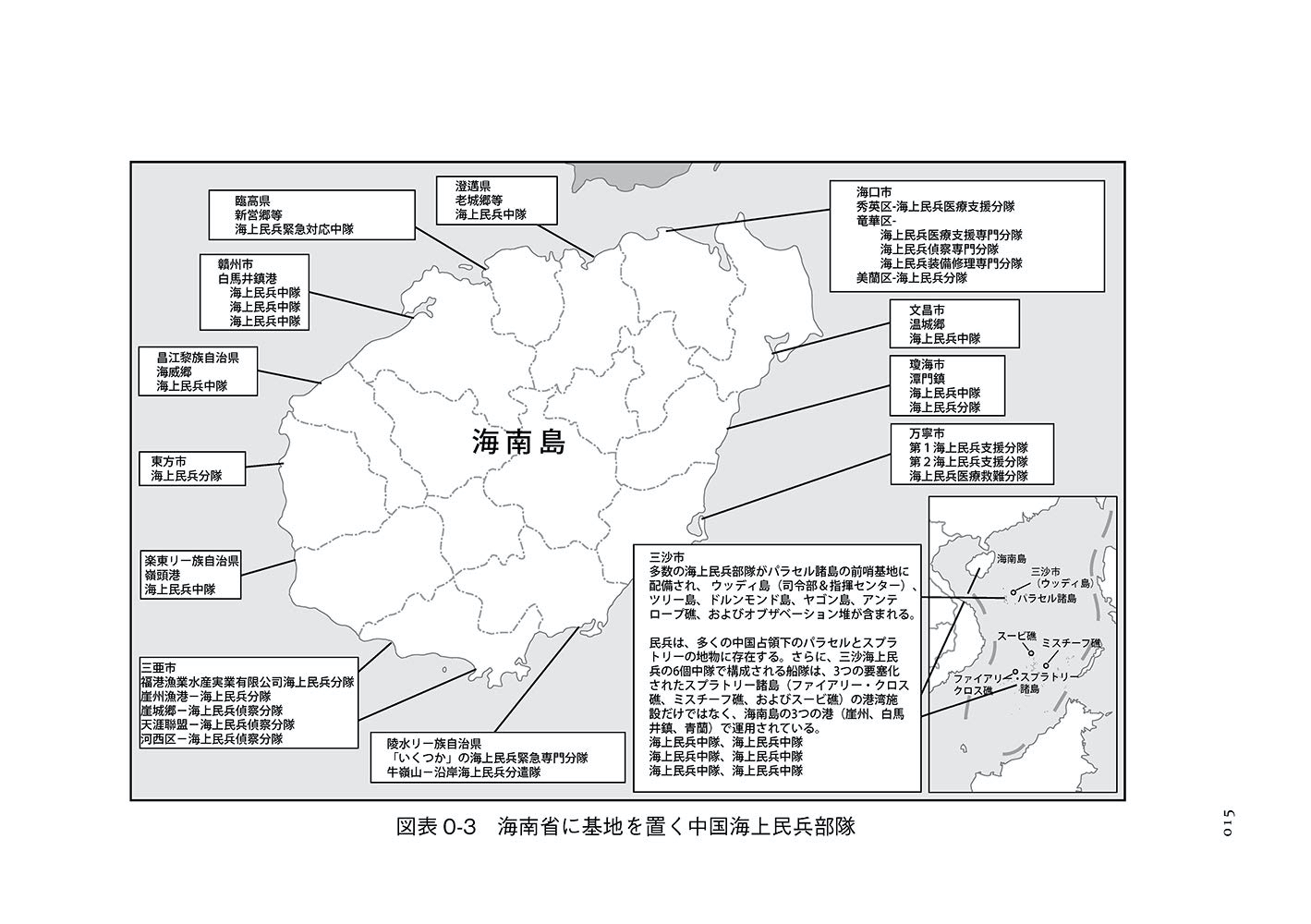

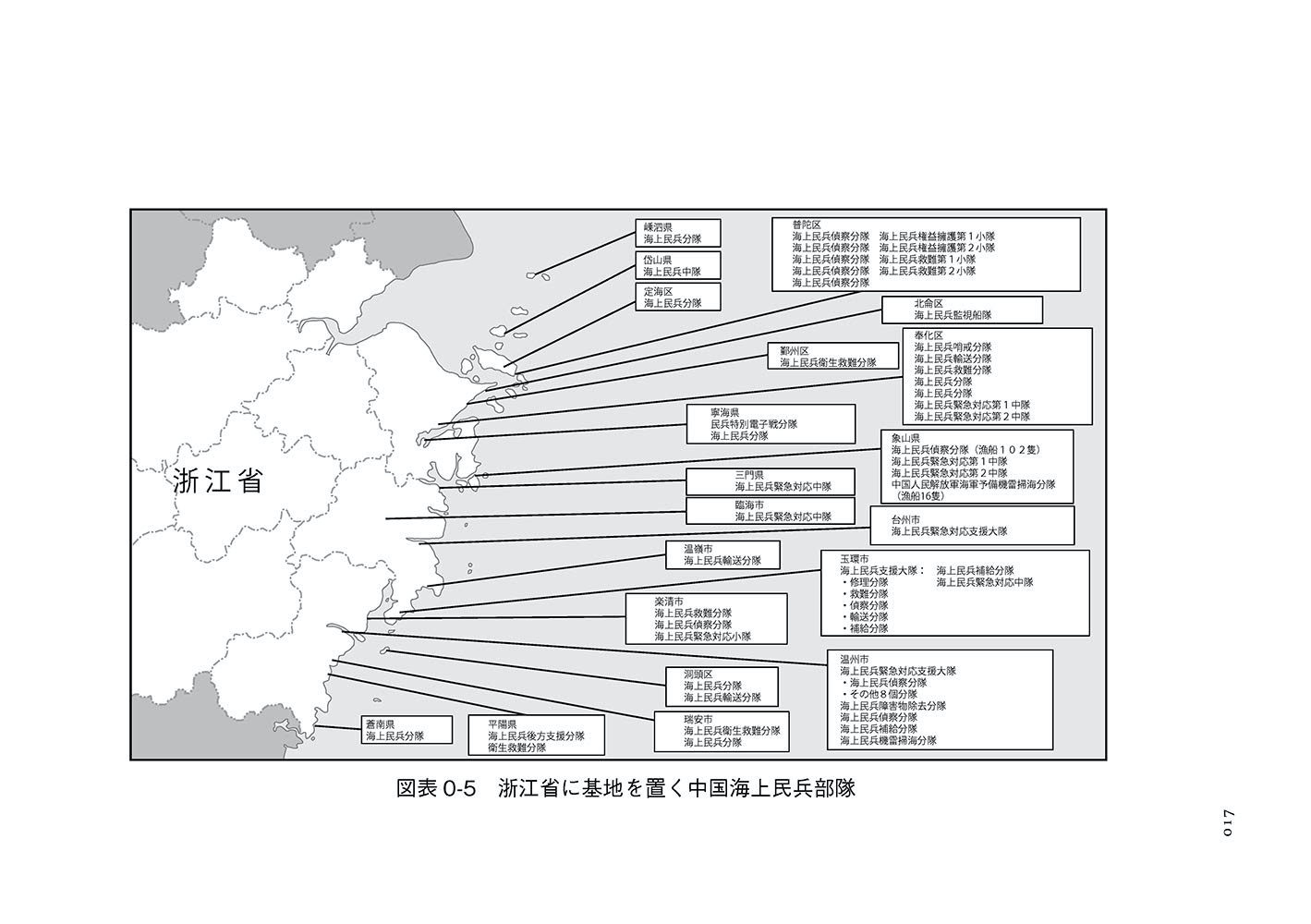

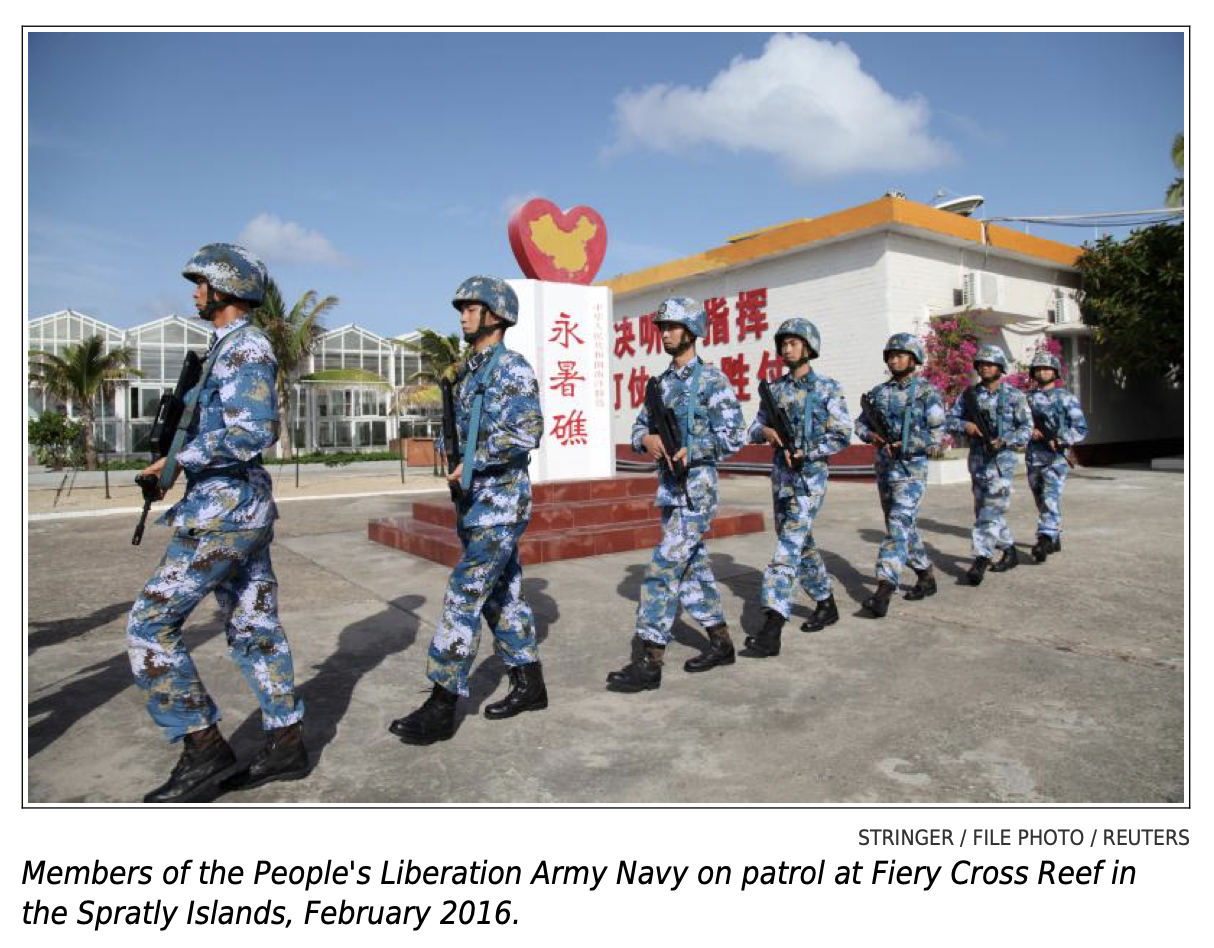

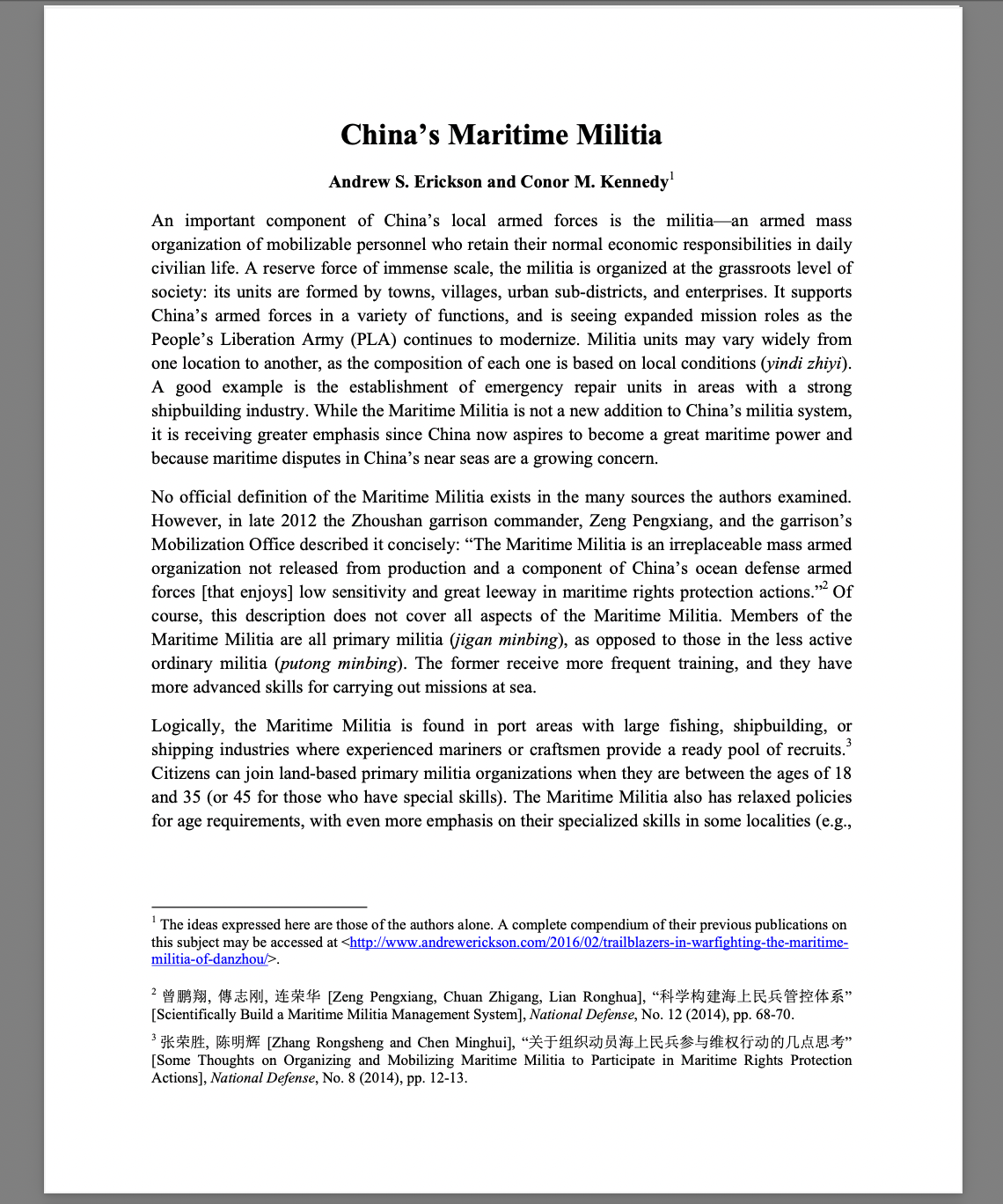

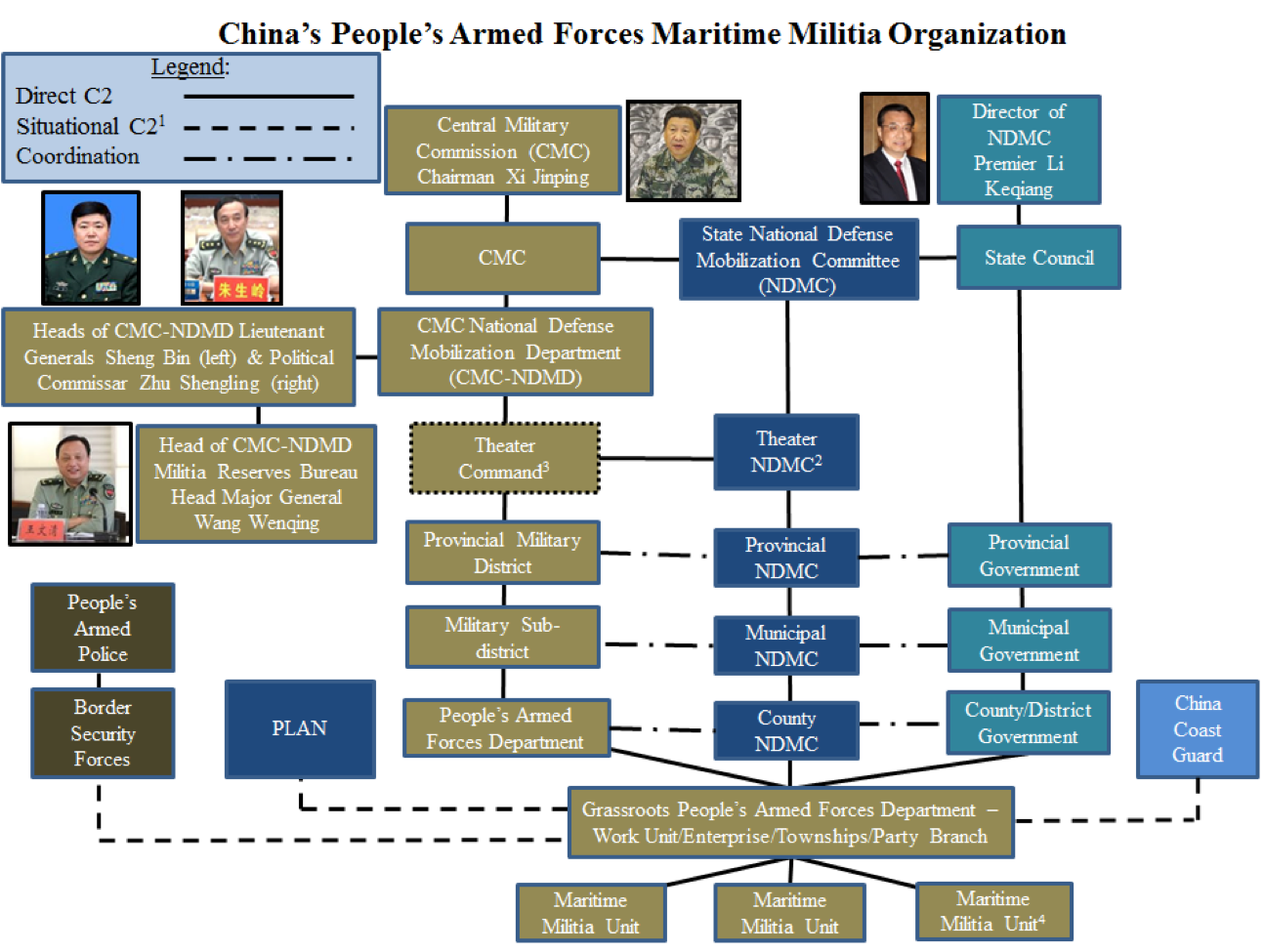

People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) is a state-organized, -developed, and -controlled force operating under a direct military chain of command to conduct Chinese state–sponsored activities.1 The PAFMM is locally organized and resourced but answers to the very top of China’s military bureaucracy: the commander in chief, Xi Jinping. While the PAFMM has been part of China’s militia system for decades, it is receiving greater emphasis today, because of its value in furthering China’s near-seas “rights and interests.”

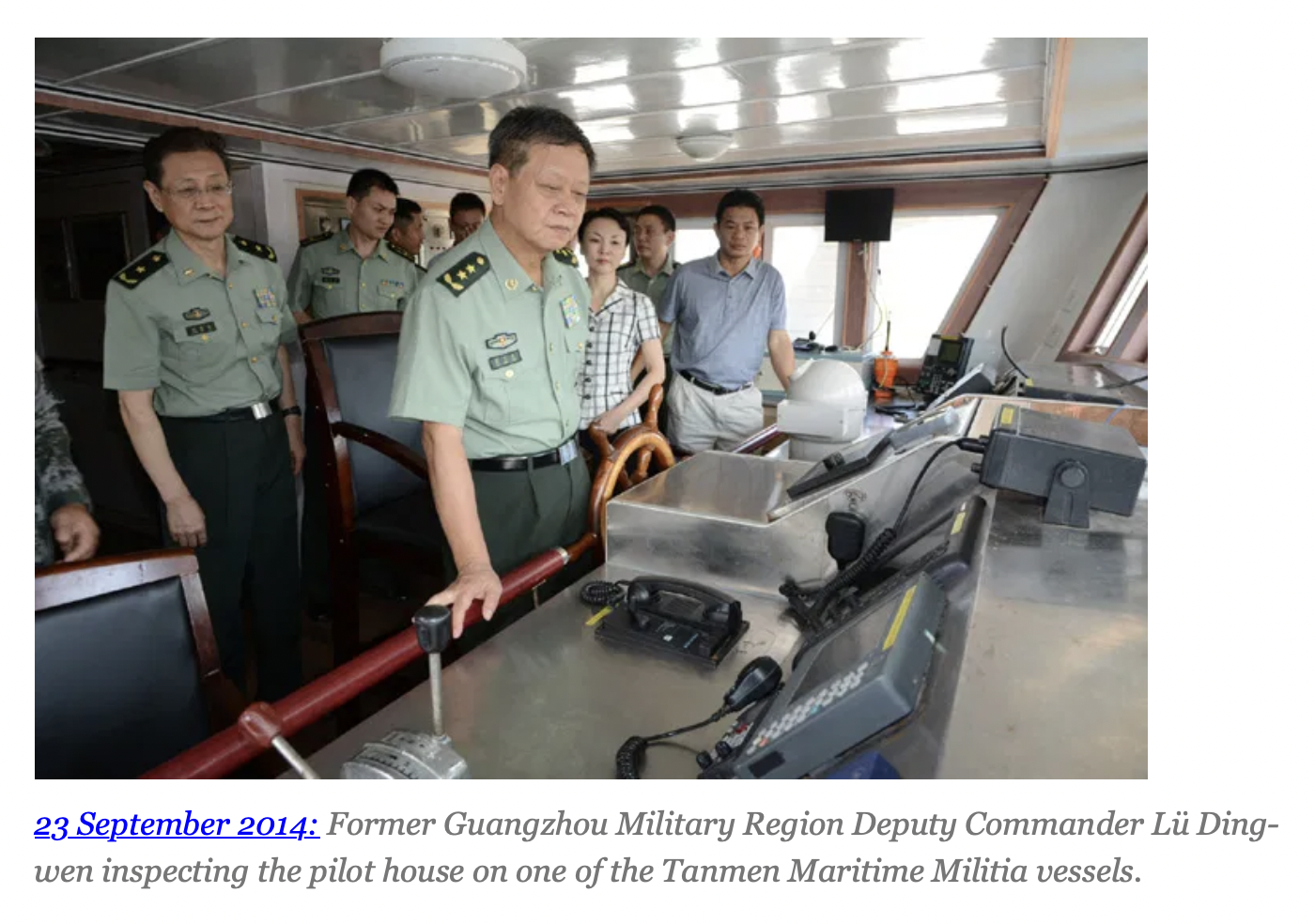

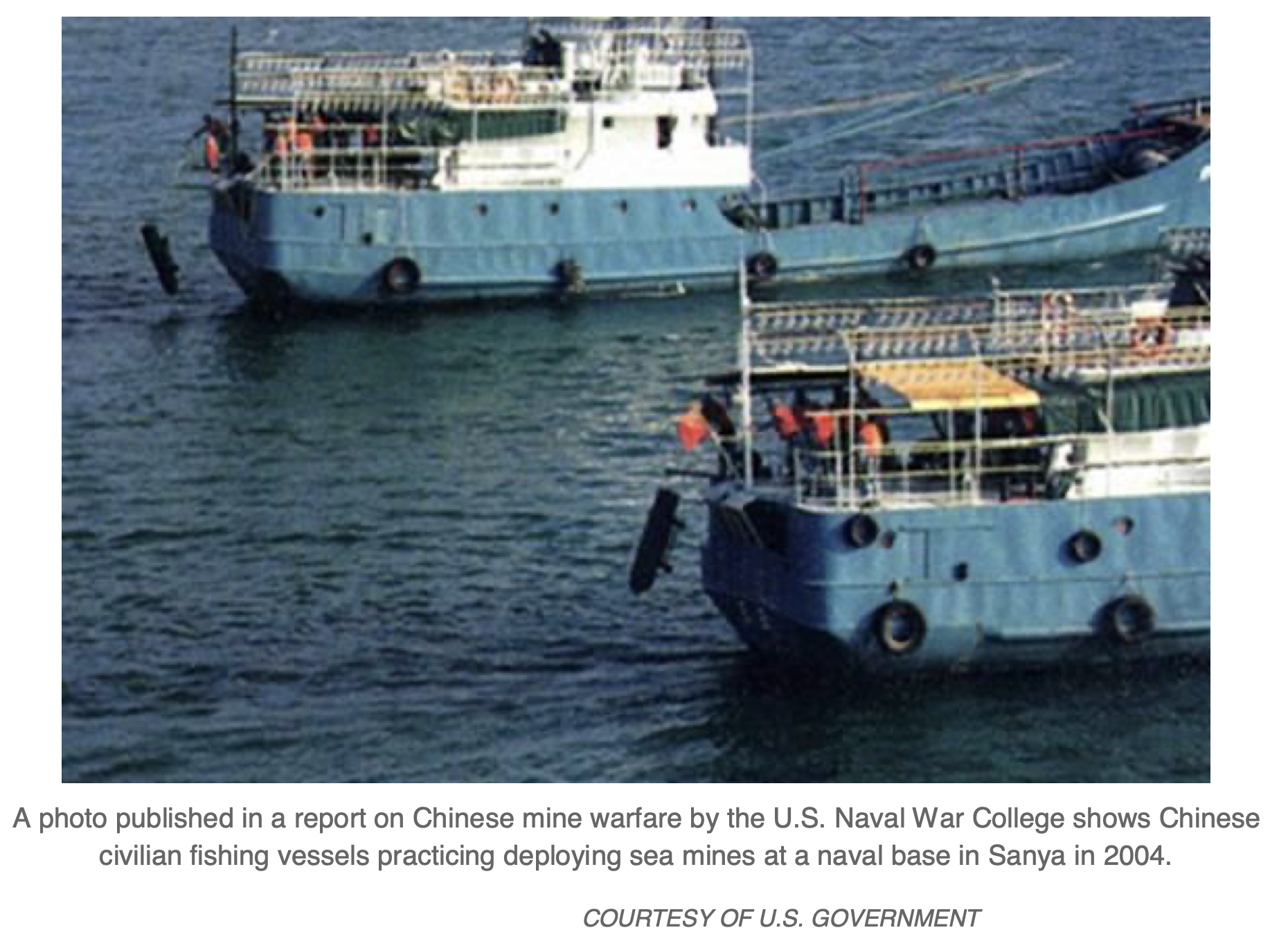

Traditionally, the PAFMM has been a military force raised from civilian marine industry workers (e.g., fishermen). Personnel keep their “day jobs” but are organized and trained in exchange for benefits and can be called up as needed. Recently, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA— in this context, the military generally) has been adding a more professionalized, militarized vanguard to the PAFMM, recruiting former servicemen (by offering them high salaries) and launching formidable purpose-built vessels. This vanguard has no apparent interest in fishing.

This chapter focuses on the current organization and employment of Chinese maritime-militia organizations. It first puts this force into historical context by surveying the PAFMM’s background and its changing role in China’s armed forces. Next, it examines the PAFMM’s current contributions toward China’s goal of becoming a great maritime power, in both old and new mission areas. The remaining sections will address specific maritime-militia modes of command and control, intelligence gathering, organization and training and will suggest possible scenarios and implications.

Decades-Long History

China’s militia system originated before the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power, but the system of recruiting numerous state- supported maritime militias from coastal populations was not fully implemented until the communists began to exercise greater control of the coastline in the 1950s. This segment of China’s population had been relatively isolated from the turmoil of the Civil War; these regions had been under either Japanese or Republic of China (ROC) control in the decades before CCP rule was established. The CCP targeted the fishing communities by creating fishing collectives and work units, enacting strict organizational and social controls, and conducting political education. Factors motivating and shaping this transformation included:

- The PLA’s early use of civilian vessels after Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party decamped to Taiwan.

- The fact that fishermen constituted the bulk of China’s experienced mariners.

- The requirement during the 1950s and 1960s to defend against Nationalist incursions along the coast.

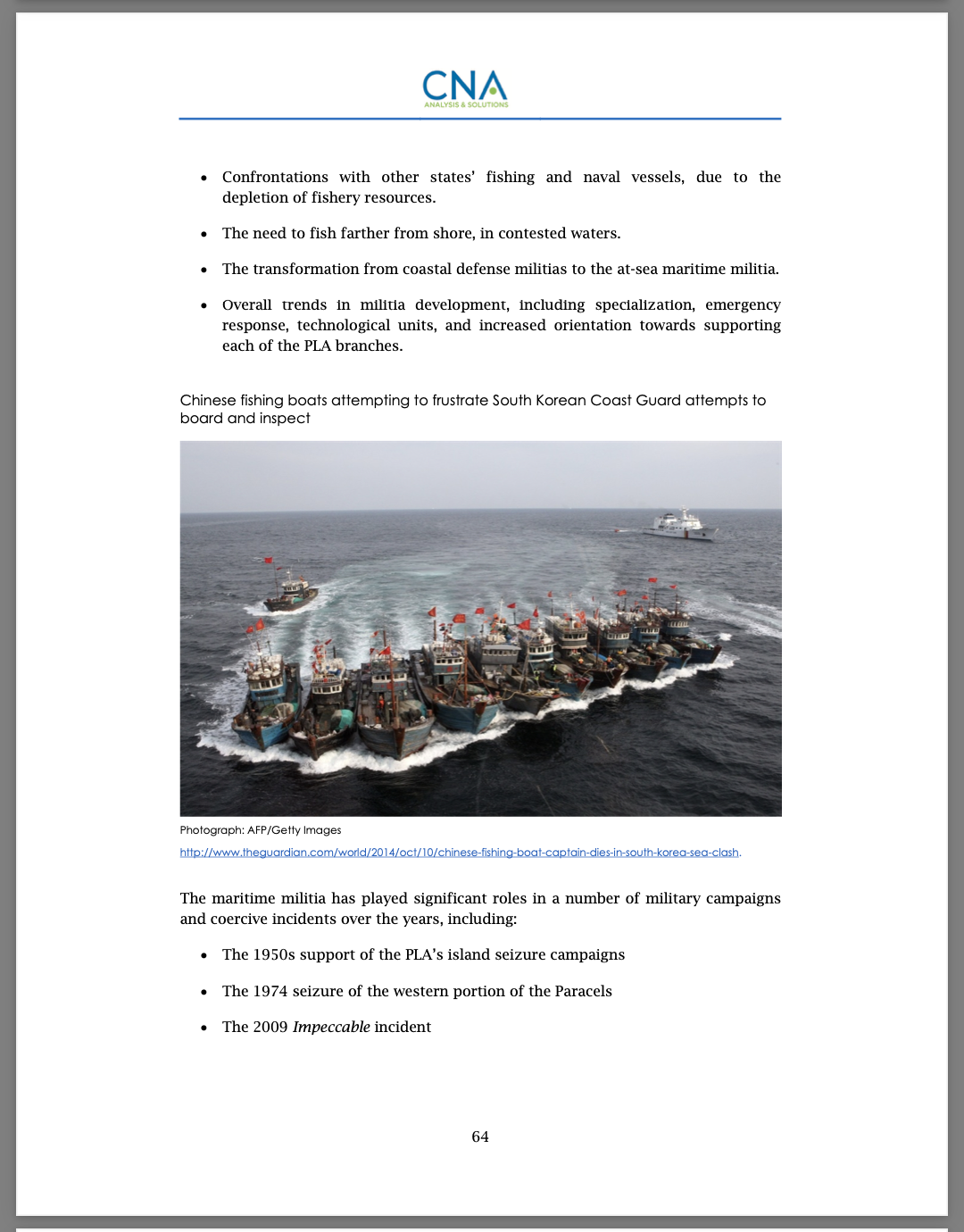

- Increasingly frequent confrontations with other states’ fishing and naval vessels as China’s fishermen gradually began to fish farther offshore.

- The transformation of many shore-based coastal-defense militias to the at-sea maritime militia.

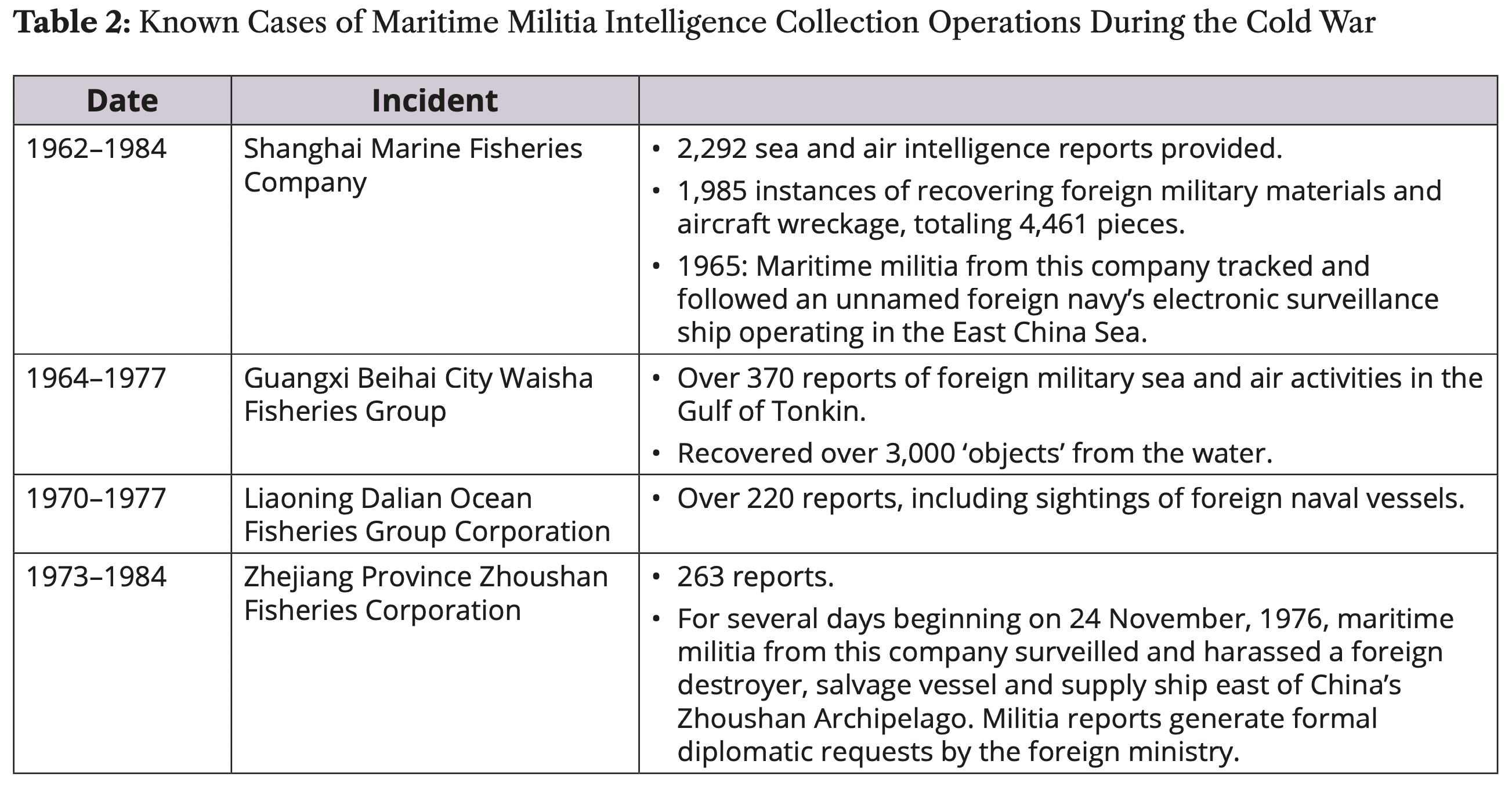

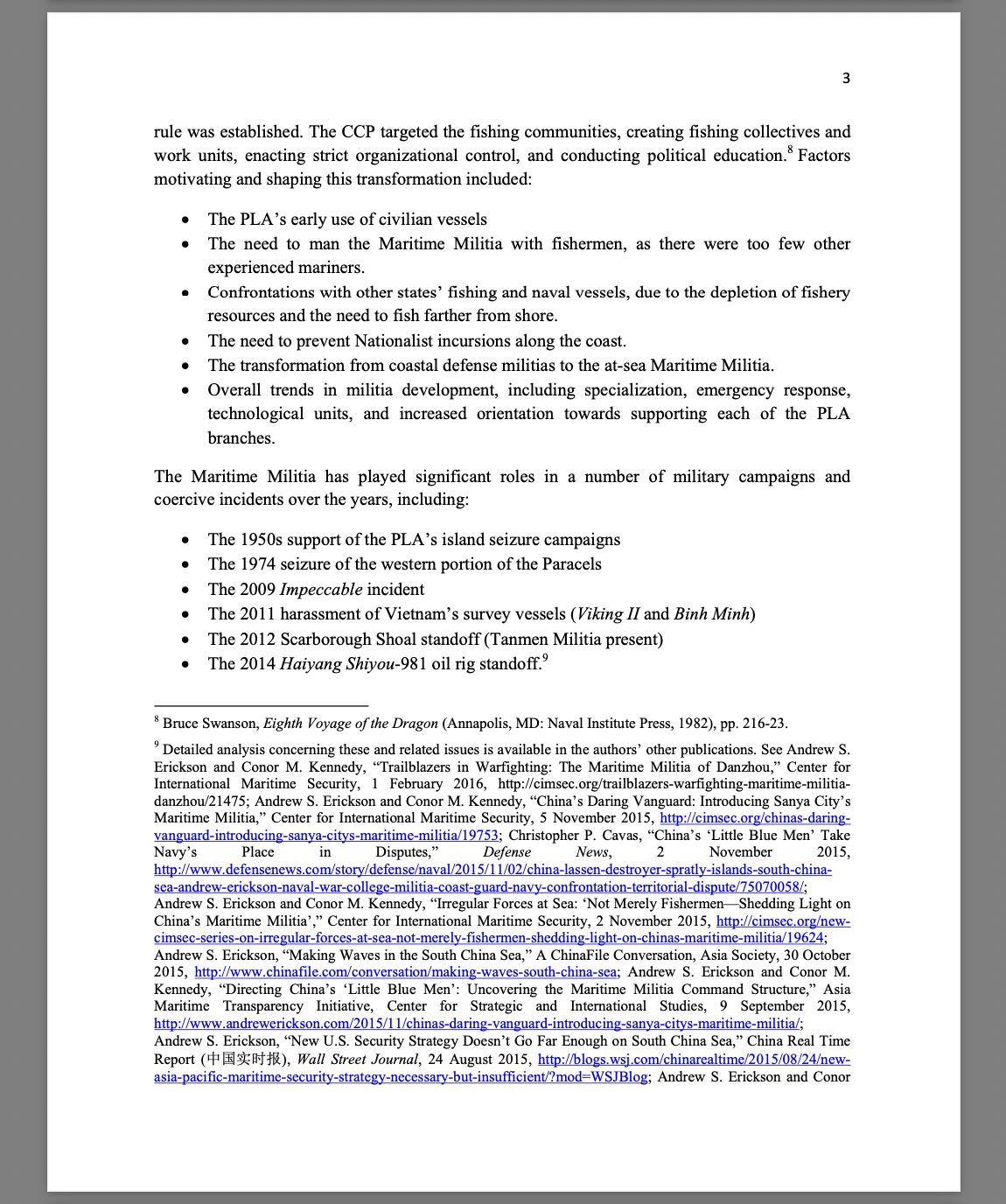

The PAFMM has played significant roles in manifold military campaigns and coercive incidents over the years:

- In the 1950s, support of the PLA’s island seizure campaigns off the mainland coast

- In the 1960s, securing of China’s coast against Nationalist infiltrations

- In 1974, seizure of the western portion of the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea from South Vietnam

- In 1976, harassment of “foreign” naval ships east of the Zhoushan Archipelago (south of Shanghai)

- In 1978, presence mission in the territorial sea of the Senkaku Islands

- In 1995, Mischief Reef encounter with the Philippines stemming from the occupation and development of that reef

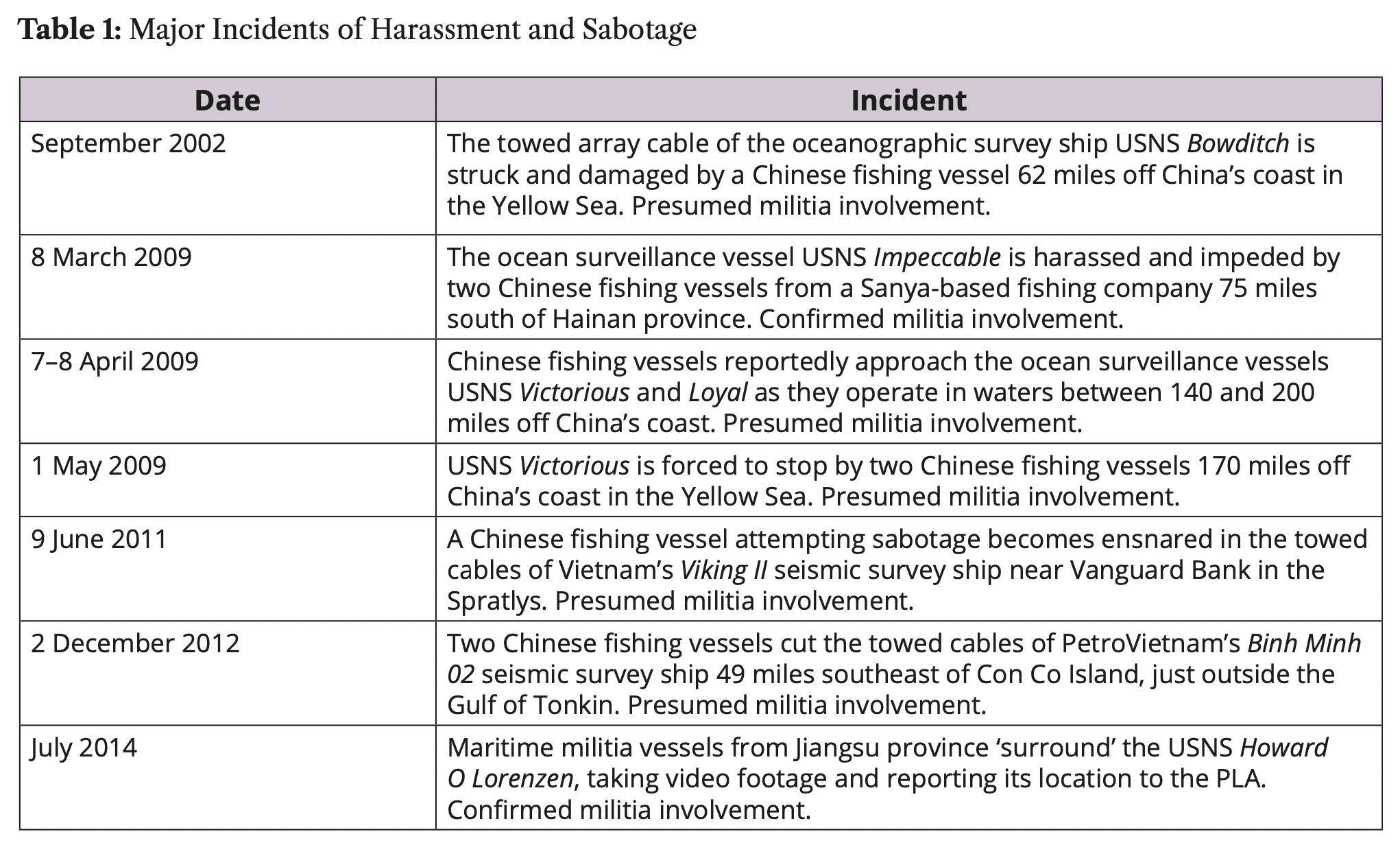

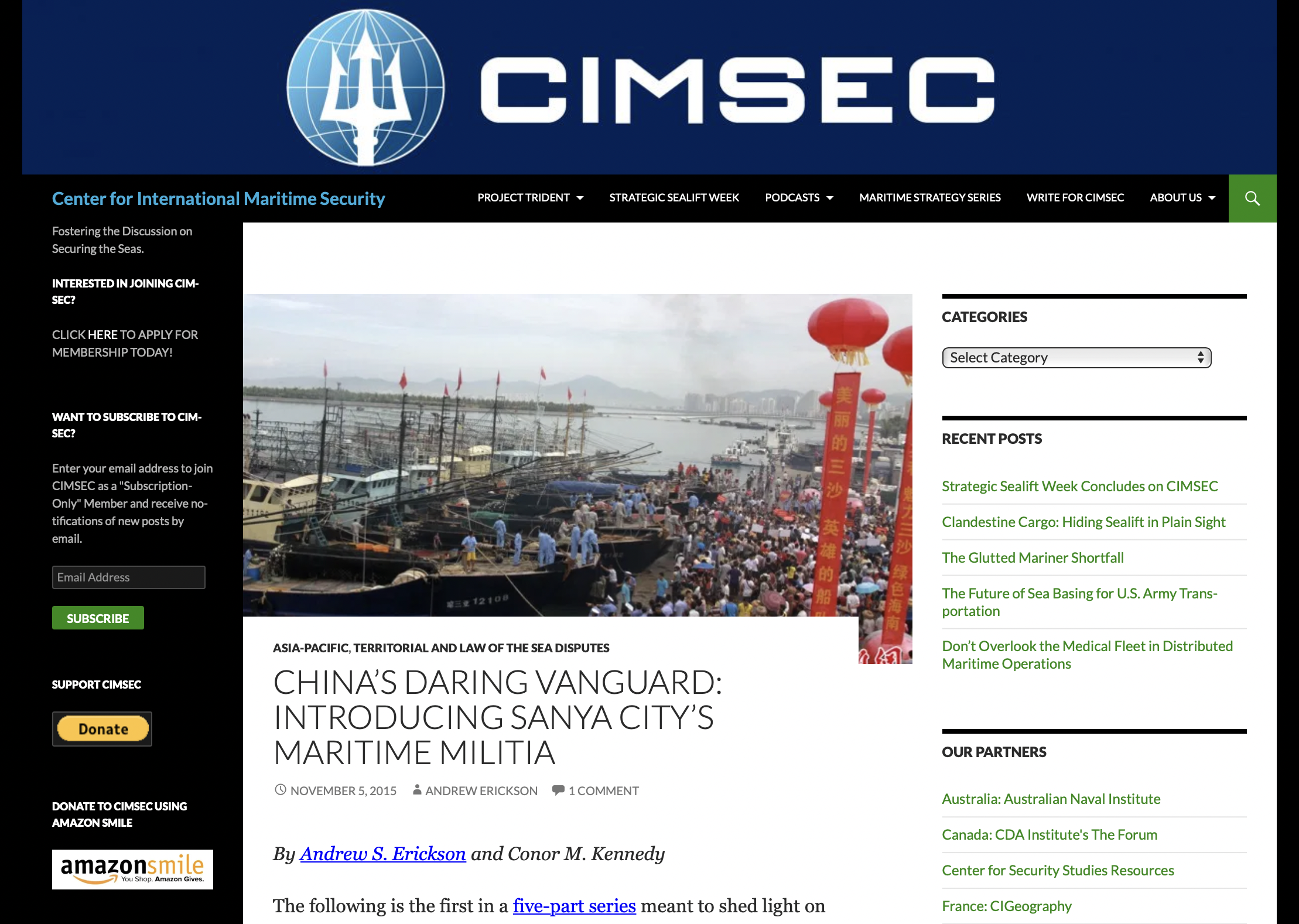

- In 2009, harassment of USNS Impeccable

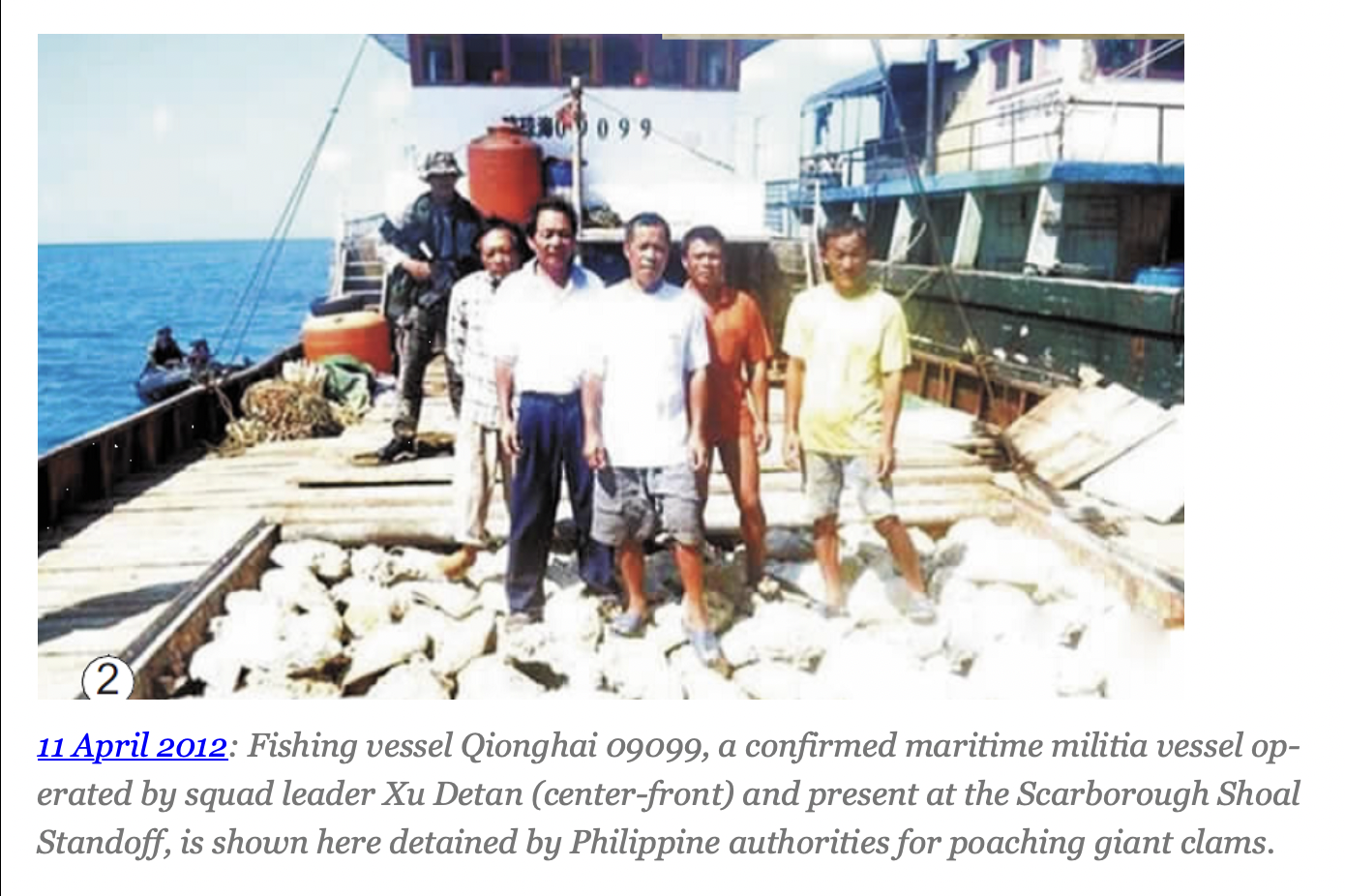

- In 2012, Scarborough Shoal stand-off with the Philippines

- In 2014, blockade of Philippine-occupied Second Thomas Shoal

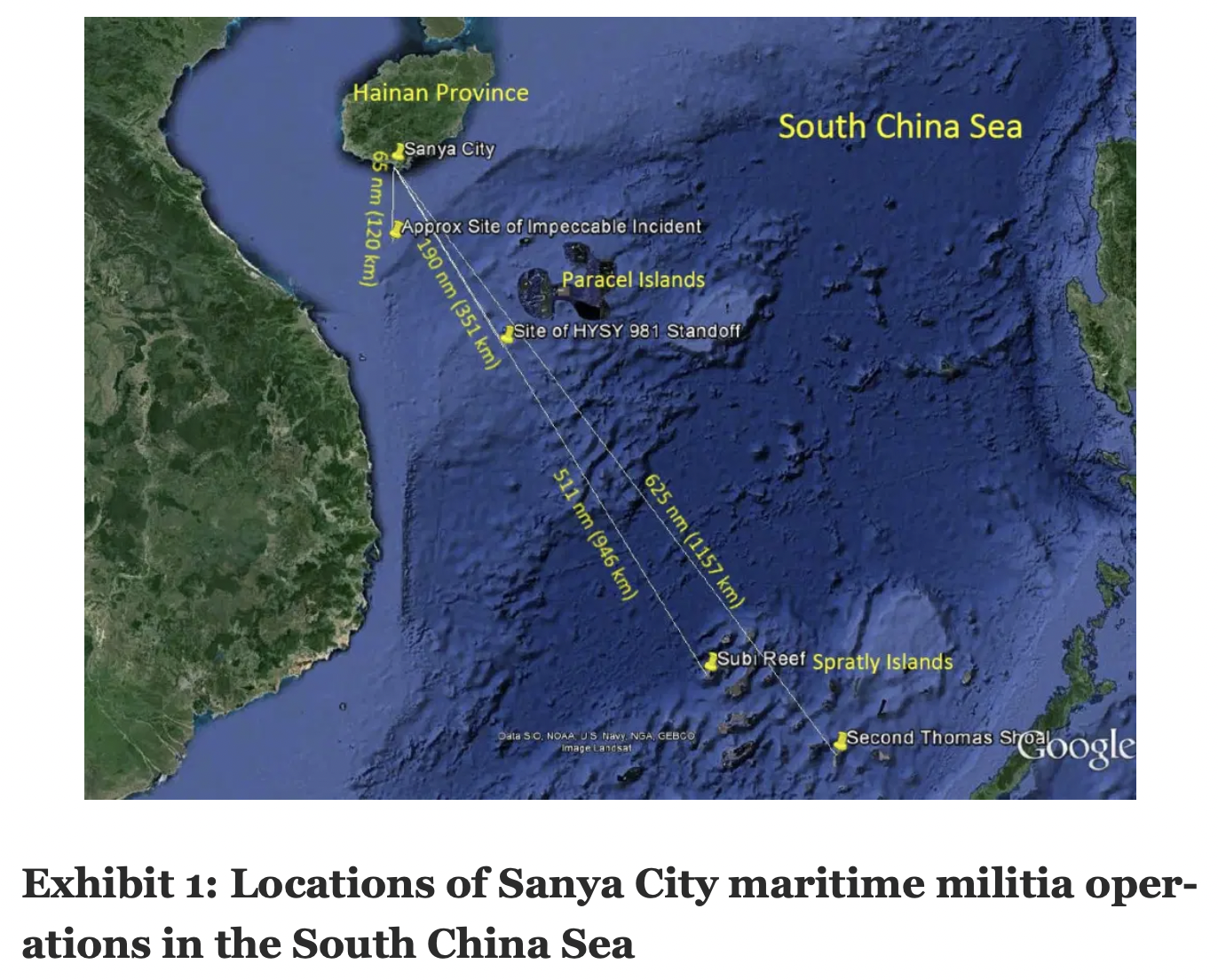

- In 2014, repulse of Vietnamese vessels from disputed waters surrounding the China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s (CNOOC’s) oil rig HYSY 981

- In 2014, harassment of USNS Howard O. Lorenzen

- In 2016, large surge of fishing craft near the Senkaku Islands

- In 2017, envelopment of Philippine-claimed Sandy Cay in the northern Spratly Islands.2 … … …

About the Author

During his 34-year Navy career, Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, USN (Ret.) had four at sea commands including an aircraft carrier battle group. He was a Pacific Ocean sailor with experience in all the waters he has written about. He began a 30-year involvement with U.S. security policy and strategy in Asia when he was assigned to the Office of Secretary of Defense in 1990 as Director and then as Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for East Asia. This professional interest continues to this day.

Summary

Xi Jinping has made his ambitions for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) perfectly clear, there is no mystery what he wants, first, that China should become a “great maritime power” and secondly, that the PLA “become a world-class armed force by 2050.” He wants this latter objective to be largely completed by 2035. China as a Twenty-First-Century Naval Power focuses on China’s navy and how it is being transformed to satisfy the “world class” goal.

Beginning with an exploration of why China is seeking to become such a major maritime power, author Michael McDevitt first explores the strategic rationale behind Xi’s two objectives: China’s reliance on foreign trade and overseas interests such as China’s Belt and Road strategy. In turn this has created concerns within the senior levels of China’s military about the vulnerability of its overseas interests and maritime life-lines: a major theme. McDevitt dubs this China’s “sea lane anxiety” and traces how this has required the PLA Navy to evolve from a “near seas”-focused navy to one that has global reach; a “blue water navy.” He details how quickly this transformation has taken place, thanks to a patient step-by-step approach and abundant funding. The more than 10 years of anti-piracy patrols in the far reaches of the Indian Ocean has acted as a learning curve accelerator to “blue water” status.

McDevitt then explores the PLA Navy’s role in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. He provides a detailed assessment of what the PLAN will be expected to do if Beijing chooses to attack Taiwan, potentially triggering combat with America’s “first responders” in East Asia, especially the U.S. Seventh Fleet and U.S. Fifth Air Force.

He conducts a close exploration of how the PLA Navy fits into China’s campaign plan aimed at keeping reinforcing U.S. forces at arm’s length (what the Pentagon calls anti-access and area denial [A2/AD]) if war has broken out over Taiwan, or because of attacks on U.S. allies and friends that live in the shadow of China. McDevitt does not know how Xi defines “world class” but the evidence from the past 15 years of building a blue water force has already made the PLA Navy the second largest globally capable navy in the world. This book concludes with a forecast of what Xi’s vision of a “world-class navy” might look like in the next fifteen years when the 2035 deadline is reached.

Reviews

“Rear Admiral Mike McDevitt delivers the definitive study on China’s ambitious quest for greatness at sea. Armed with decades of operational experience, he renders persuasive judgments about China’s nautical ascent. For those looking for an authoritative yet accessible appraisal of the Chinese navy, this is it.”

— Toshi Yoshihara, senior fellow, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, co-author of Red Star over the Pacific: China’s Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy, 2nd ed.

“In order to counter China’s willful and persistent challenges against the stabilizing PAX-AMERICANA global framework, an accurate and comprehensive understanding of China’s security and naval strategies is required. In this context, RADM Mike McDevitt’s superb book is a ‘must-read’ for naval/security specialists, as well as national leaders and thinkers.”

— Yoji Koda, Former Commander in Chief, JMSDF Fleet

“Admiral Michael McDevitt has written an important book about China as a world power. Few Americans possess his knowledge of maritime strategy and China. He has combined this knowledge with his background as a historian and a sea-going officer with more thirty years’ experience. China as a Twenty-First-Century Naval Power is a must read for military officers, China specialists, and historians.”

— Captain Bernard D. Cole, USN (Ret.), Professor Emeritus, National War College, author of China’s Quest for Great Power: Ships, Oil, and Foreign Policy

“Admiral McDevitt has written the definitive book on China’s maritime ambitions and its ability to fulfill them. His years of careful research following a career of high-level Navy and Defense Department positions are blended into a carefully detailed and documented, yet practical and sensible examination of China’s security shift from land defense to control of the seas. The discussions of Taiwan and the South China Sea are especially informative and sobering. The implications are judicious and very clear – the United States must urgently and intelligently increase its own maritime and air capability.”

— Dennis C. Blair, former Commander in Chief, US Pacific Command and former Director of National Intelligence

“Rear Admiral McDevitt has studied the Chinese navy from the decks of destroyers in the South China Sea to the corridors of leading think tanks around the world. His expertise is legendary, and this new book is a commanding analysis of the course China will steer over the coming decades in their voyage to become the leading global maritime power.”

— Adm. James Stavridis, USN (Ret.), 16th Supreme Allied Commander of NATO and author of Sailing True North: Ten Admirals and the Voyage of Character

“As he explores the rationale for China’s unprecedented accretion of maritime power and quest for a ‘world-class’ navy, McDevitt provides perceptive insights into Beijing’s obsessive pursuit of sea-lane security, regional-hegemony and, eventually, global-dominance. The vivid future-scenarios, painted by this former practitioner of seapower, could prove prophetic, and deserve our closest attention.”

— Adm. Arun Prakash (Ret.), former Indian Navy Chief and Chairman, Chiefs of Staff

Product details

Publisher : Naval Institute Press (October 15, 2020)

Subject: Fall 2020 Catalog | China and the Asia Pacific

Item Weight : 2.5 pounds/40 oz

Product Dimensions: 9 × 6 × 1 in

Hardcover : 320 pages

Illustrations: 5 maps, 7 tables, 5 b/w illustrations

ISBN-10 : 1682475352

ISBN-13 : 978-1682475355

***

Isaac B. Kardon, Conor M. Kennedy, and Peter A. Dutton, Gwadar: China’s Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan, China Maritime Report 7 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, August 2020).

China Maritime Report No. 7 offers a detailed examination of China’s infrastructure project in the port of Gwadar, Pakistan. Written by Dr. Peter Dutton, Dr. Isaac Kardon, and Mr. Conor Kennedy, this report is the second in a series of studies looking at China’s interest in Indian Ocean ports and its “strategic strongpoints” there (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms.

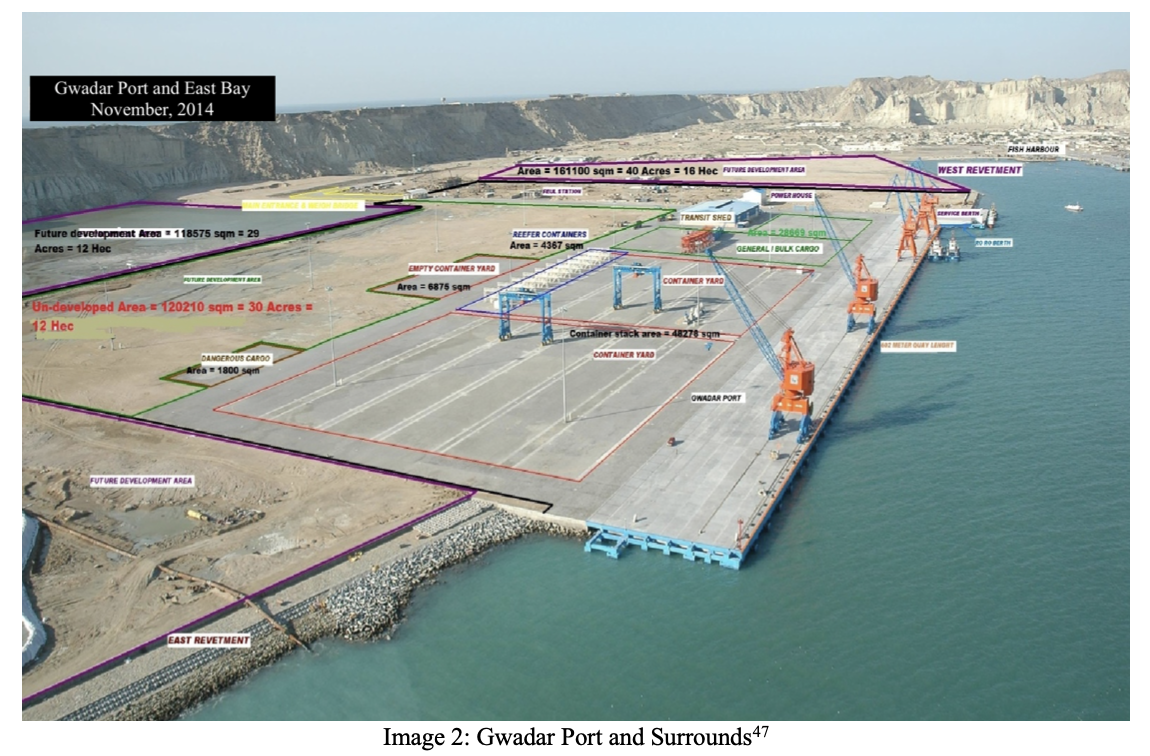

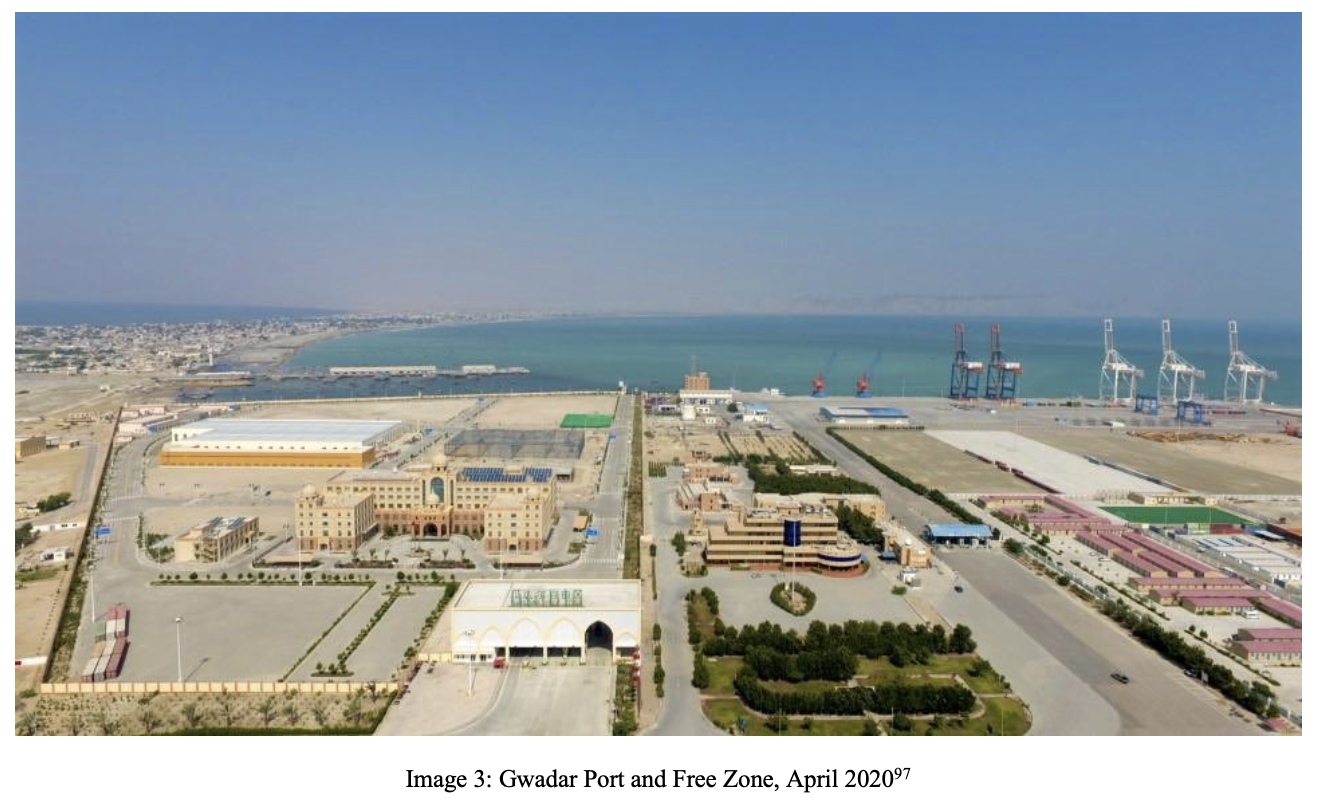

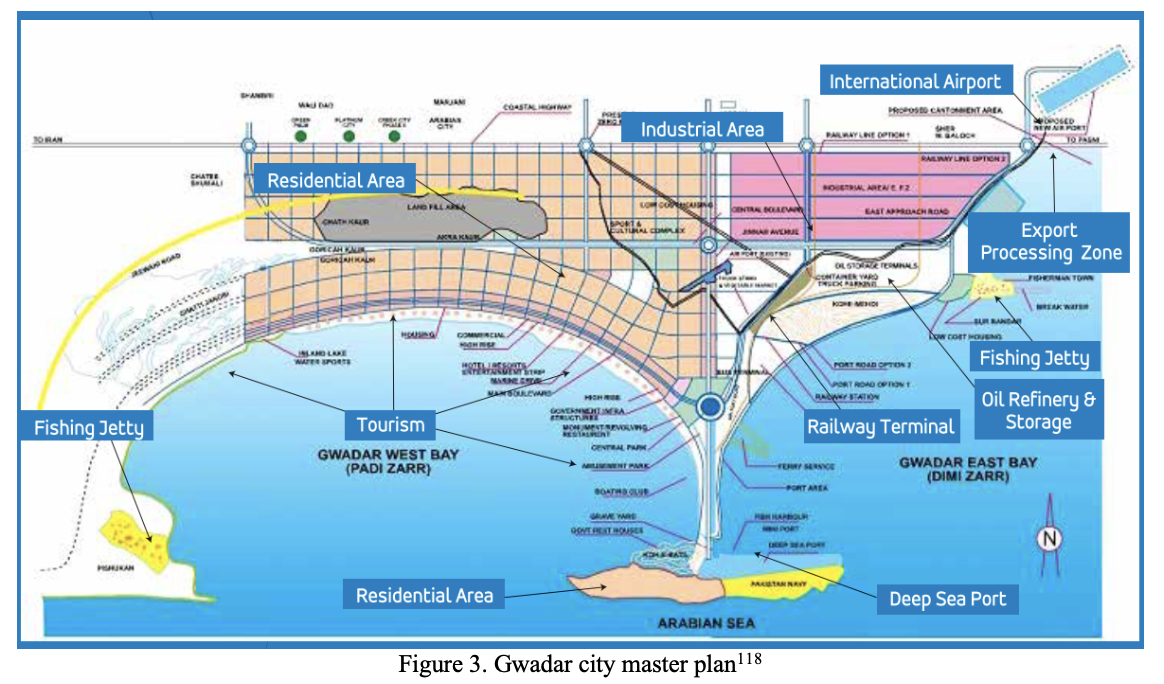

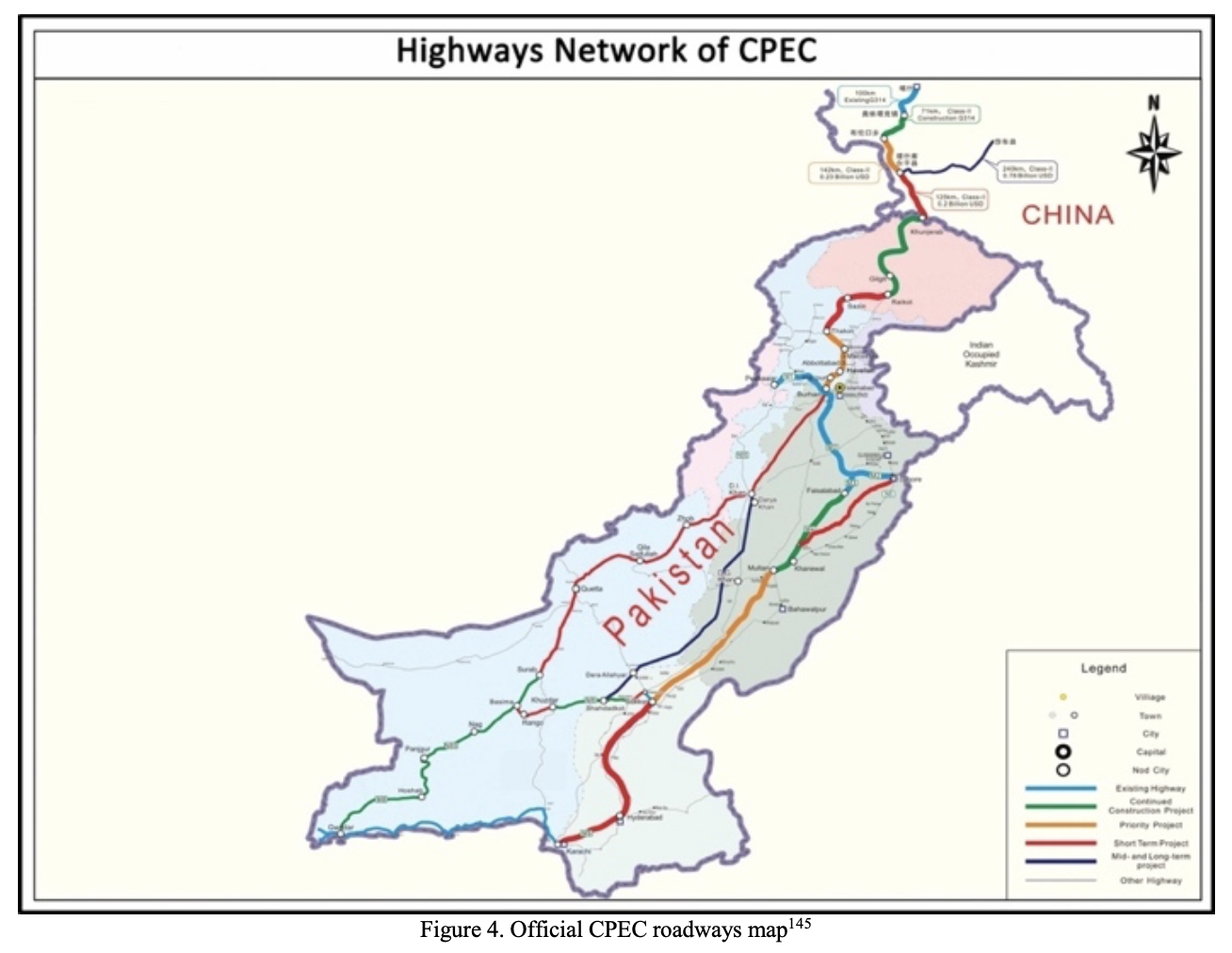

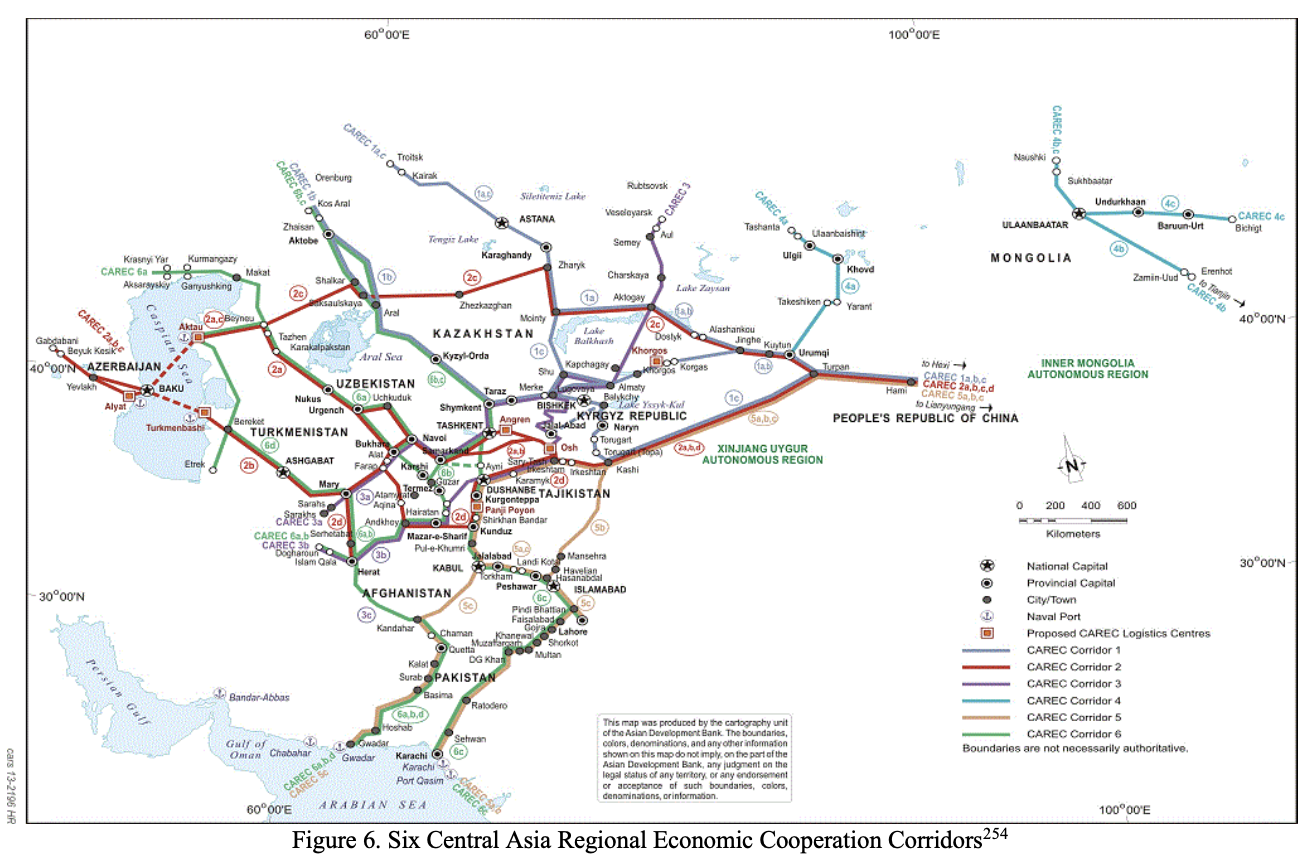

Gwadar is an inchoate “strategic strongpoint” in Pakistan that may one day serve as a major platform for China’s economic, diplomatic, and military interactions across the northern Indian Ocean region. As of August 2020, it is not a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base, but rather an underdeveloped and underutilized commercial multipurpose port built and operated by Chinese companies in service of broader PRC foreign and domestic policy objectives. Foremost among PRC objectives for Gwadar are (1) to enable direct transport between China and the Indian Ocean, and (2) to anchor an effort to stabilize western China by shoring up insecurity on its periphery. To understand these objectives, this case study first analyzes the characteristics and functions of the port, then evaluates plans for hinterland transport infrastructure connecting it to markets and resources. We then examine the linkage between development in Pakistan and security in Xinjiang. Finally, we consider the military potential of the Gwadar site, evaluating why it has not been utilized by the PLA then examining a range of uses that the port complex may provide for Chinese naval operations.

Key Findings

- Chinese analysts view Gwadar as a top choice for establishing a new overseas strategic strongpoint, owing to its prime geographic location and strong Sino-Pakistani ties. Many PLA analysts consider Gwadar to be a suitable site for naval support.

- China’s interest in Gwadar—and in Pakistan’s economic development in general—does not depend primarily on commercial returns. Instead, the Gwadar project is best understood as a mode of strategic investment in China’s internal and external security.

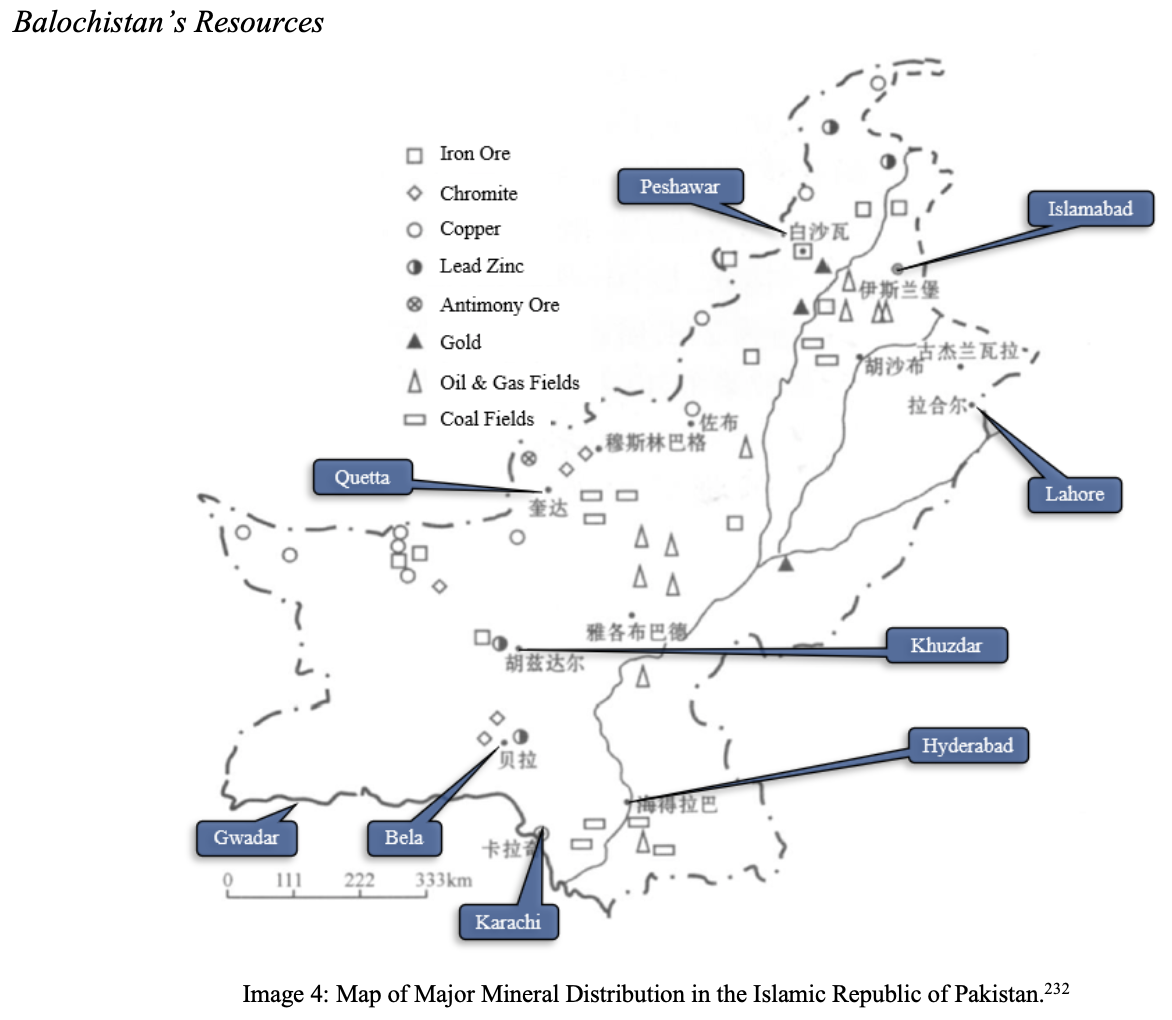

- Externally, Gwadar’s principal strategic purpose for China is to become an “exit to the ocean” (出海口)—that is, a direct route via Chinese infrastructure to secure reliable access to the strategic space and resources of the northern Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf.

- Internally, Gwadar is an extension of China’s national security and development policies. Beijing seeks to develop commercial linkages between western China, Pakistan, and Central Asia to promote economic growth and thus manage perceived risks to social stability in Xinjiang.

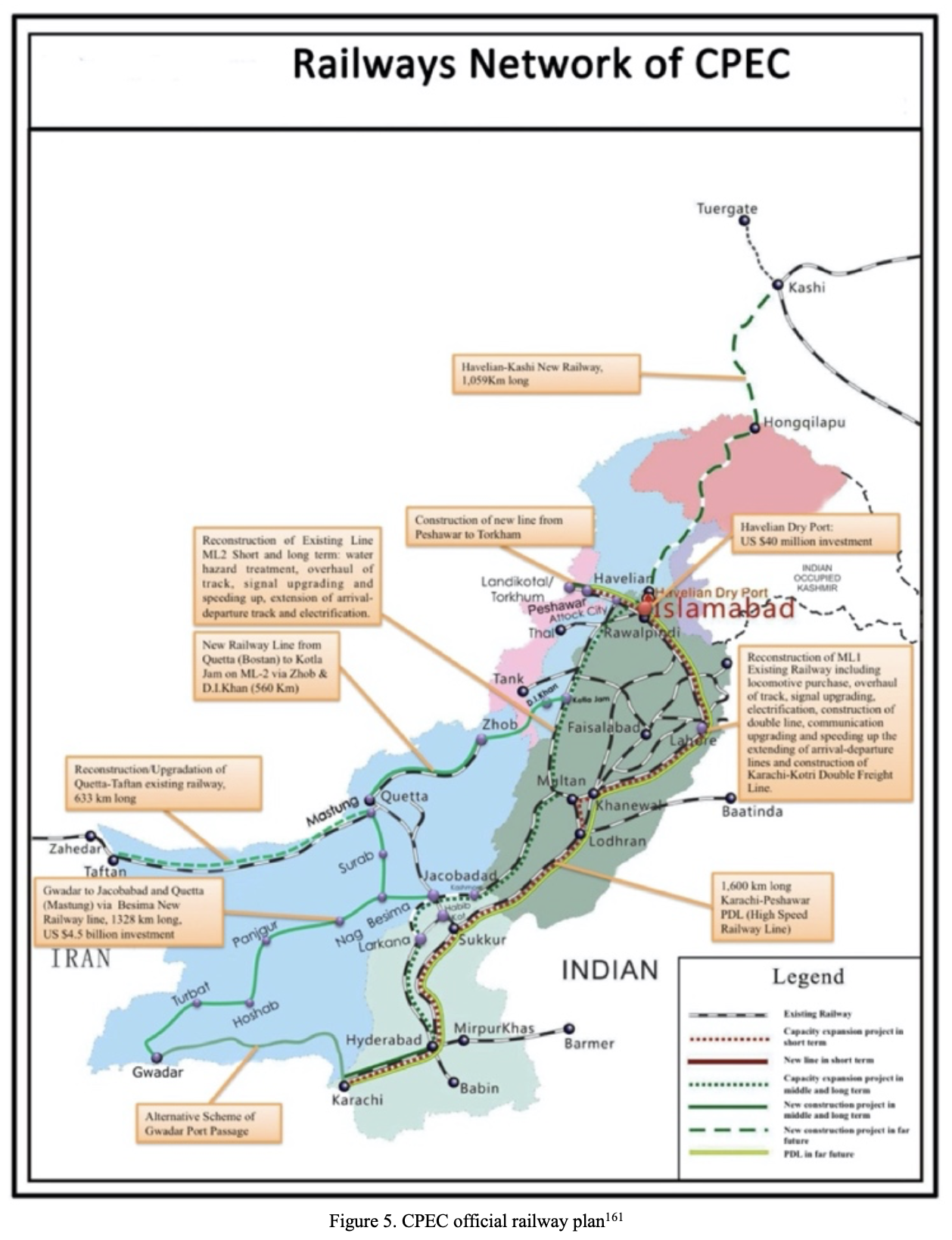

- Extensive transport infrastructure is fundamental to China’s overall plans for Pakistan. Yet while the planned transport corridor is often discussed as though it were operational, very little modern infrastructure has been built beyond a few roads and the port itself.

- The inland markets and resources of Pakistan (and Afghanistan) present some commercial prospects, but these have not yet borne fruit in part due to severe insecurity.

- Security measures may mitigate some risks to Chinese projects and personnel, but Gwadar and its hinterlands are unlikely to be secure enough to become a major commercial entrepôt.

- Gwadar is not a PLA base, but it is used extensively by the Pakistan Navy (PN). The PN operates frigates and patrol vessels bought from China and will also field Chinese-made submarines. Their facilities, parts, and technicians may be readily employed for some of the PLAN fleet.

- Gwadar’s port facilities could support the PLAN’s largest vessels. Beyond the pier, Gwadar possesses a sizeable laydown yard for marshalling military equipment and materials.

- Gwadar will not necessarily have utility as a base in a wartime scenario. The most critical factor informing this view is the apparent lack of political commitment between China and Pakistan to provide mutual military support during times of crisis or conflict.

- If the infrastructure projects mature, Gwadar could become a key peacetime replenishment or transfer point for PLA equipment and personnel. Prepositioning parts, supplies, and other materials at Gwadar would be a productive use of the port and airfield facilities.

Series Overview

This China Maritime Report on Gwadar is the second in a series of case studies on China’s Indian Ocean “strategic strongpoints” (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms. Each case study analyzes a different port on the Indian Ocean, selected to capture geographic, commercial, and strategic variation. Each employs the same analytic method, drawing on Chinese official sources, scholarship, and industry reporting to present a descriptive account of the port, its transport infrastructure, the markets and resources it accesses, and its naval and military utility.

The case studies illuminate the various functions of overseas strategic strongpoint ports in China’s Indian Ocean strategy. While the ports and associated infrastructure projects vary across key characteristics, all ports share certain distinctive qualities: (1) strategic location, positioned astride major sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and/or near vital maritime chokepoints; (2) high-level coordination among Chinese party-state officials, state-owned enterprises, and private firms; (3) comprehensive commercial scope, including Chinese-led development of associated rail, road, and pipeline infrastructure and efforts to promote trade, financing, industry, resource extraction, and inland markets; and (4) potential or actual military utilization, with dual-use functions that can enable both economic and military activities.

Ports are a key enabler for China’s economic, political, and potentially military expansion across the globe. As China’s overseas economic activity grows, so too have demands on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to secure PRC citizens, investments, and supply lines abroad. Official PLA missions now include “safeguarding the security of China’s overseas interests,” but “deficiencies in overseas operations and support” persist. Yet with the notable exception of the sole overseas PLA Navy (PLAN) base at Djibouti, all of the facilities examined in this series are ostensibly commercial. Notably, the establishment of the Djibouti base followed many years of Chinese investment at the adjacent commercial port and sustained attention into resources and markets inland.

We should not assume that Djibouti is a model for other future bases. Instead, China’s strategic strongpoint model should be understood as an evolving alternative to the familiar model of formal overseas basing. With strongpoints, trade, investment, and diplomacy with the host country remain the principal functions. However, the strongpoint creates conditions of possibility for the PLAN to establish a network of supply, logistics, and intelligence hubs. We are already observing this nascent network in operation across the Indian Ocean, and this series seeks to understand its key nodes.

***

Peter A. Dutton, Isaac B. Kardon, and Conor M. Kennedy, Djibouti: China’s First Overseas Strategic Strongpoint, China Maritime Report 6 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, April 2020).

China’s first overseas strategic strongpoint at Djibouti is a secure commercial foothold on the African continent and a military platform for expanding PLA operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

This China Maritime Report on Djibouti is the first in a series of case studies on China’s “overseas strategic strongpoints” (海外战略支点). The strategic strongpoint concept has no formal definition, but is used by People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials and analysts to describe foreign ports with special strategic and economic value that host terminals and commercial zones operated by Chinese firms.

Series Introduction

This China Maritime Report on Djibouti is the first in a series of case studies on China’s “overseas strategic strongpoints” (海外战略支点). The strategic strongpoint concept has no formal definition, but is used by People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials and analysts to describe foreign ports with special strategic and economic value that host terminals and commercial zones operated by Chinese firms. Each case study examines the characteristics and functions of port projects developed and operated by Chinese companies across the Indian Ocean region. The distinctive features of these projects are: (1) their strategic locations, positioned astride major sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and clustered near vital maritime chokepoints; (2) the comprehensive nature of Chinese investments and operations, involving coordination among state-owned enterprises and private firms to construct not only the port, but rail, road, and pipeline infrastructure, and further, to promote finance, trade, industry, and resource extraction in inland markets; and (3) their fused civilian and military functions, serving as platforms for economic, military, and diplomatic interactions.

Strategic strongpoints advance a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership objective to become a “strong maritime power” (海洋强国)—which requires, inter alia, the development of a strong marine economy and the capability to protect “Chinese rights and interests” in the maritime domain. With the notable exception of the sole overseas People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base at Djibouti, all of the facilities examined in this series are ostensibly commercial. Even the Chinese presence in Djibouti has some major commercial motivations (addressed in detail in this study). However, China’s strategic strongpoint model integrates China’s various commercial and strategic interests, facilitating Chinese trade and investment with the host country while also helping the PLA establish a network of supply, logistics, and intelligence hubs across the Indian Ocean and beyond.

Report Summary

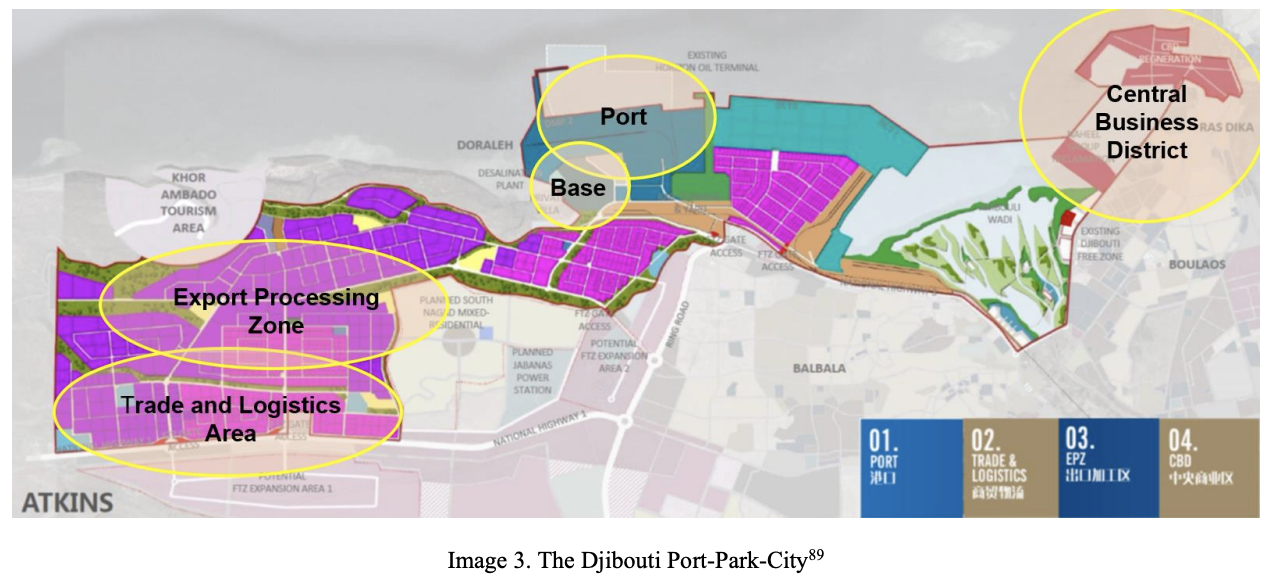

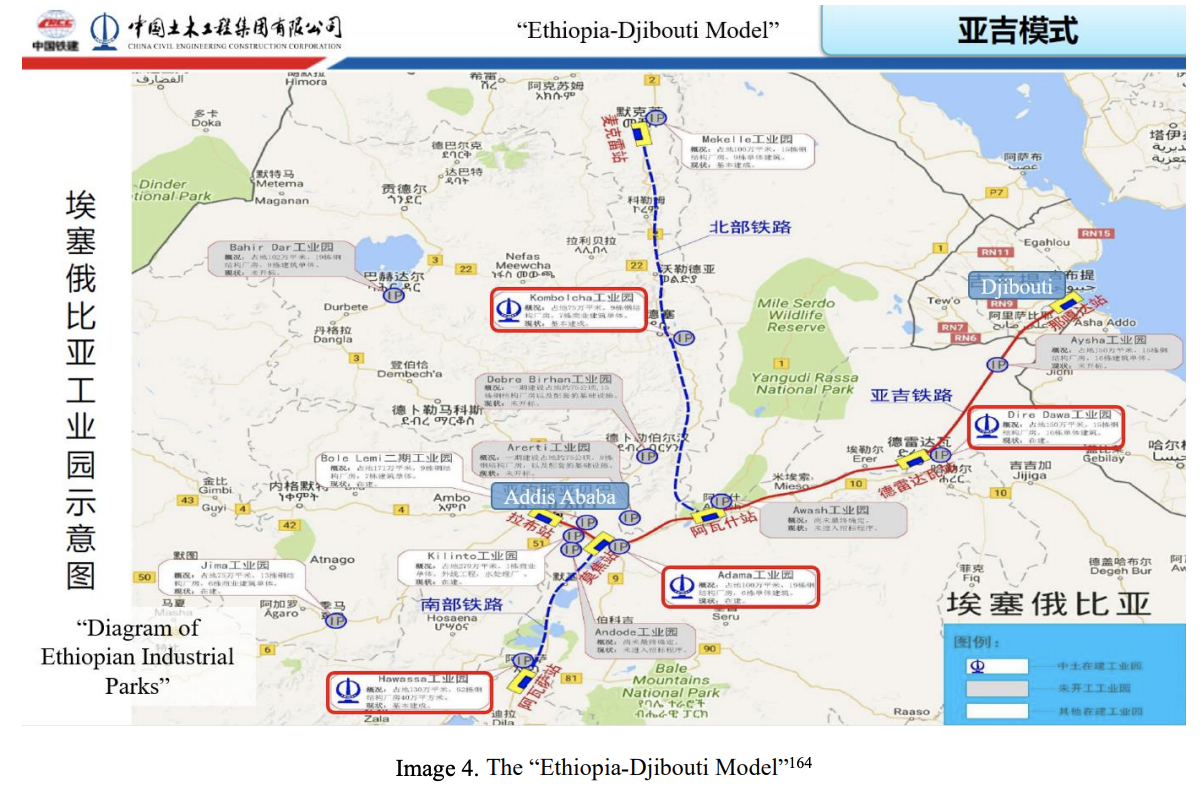

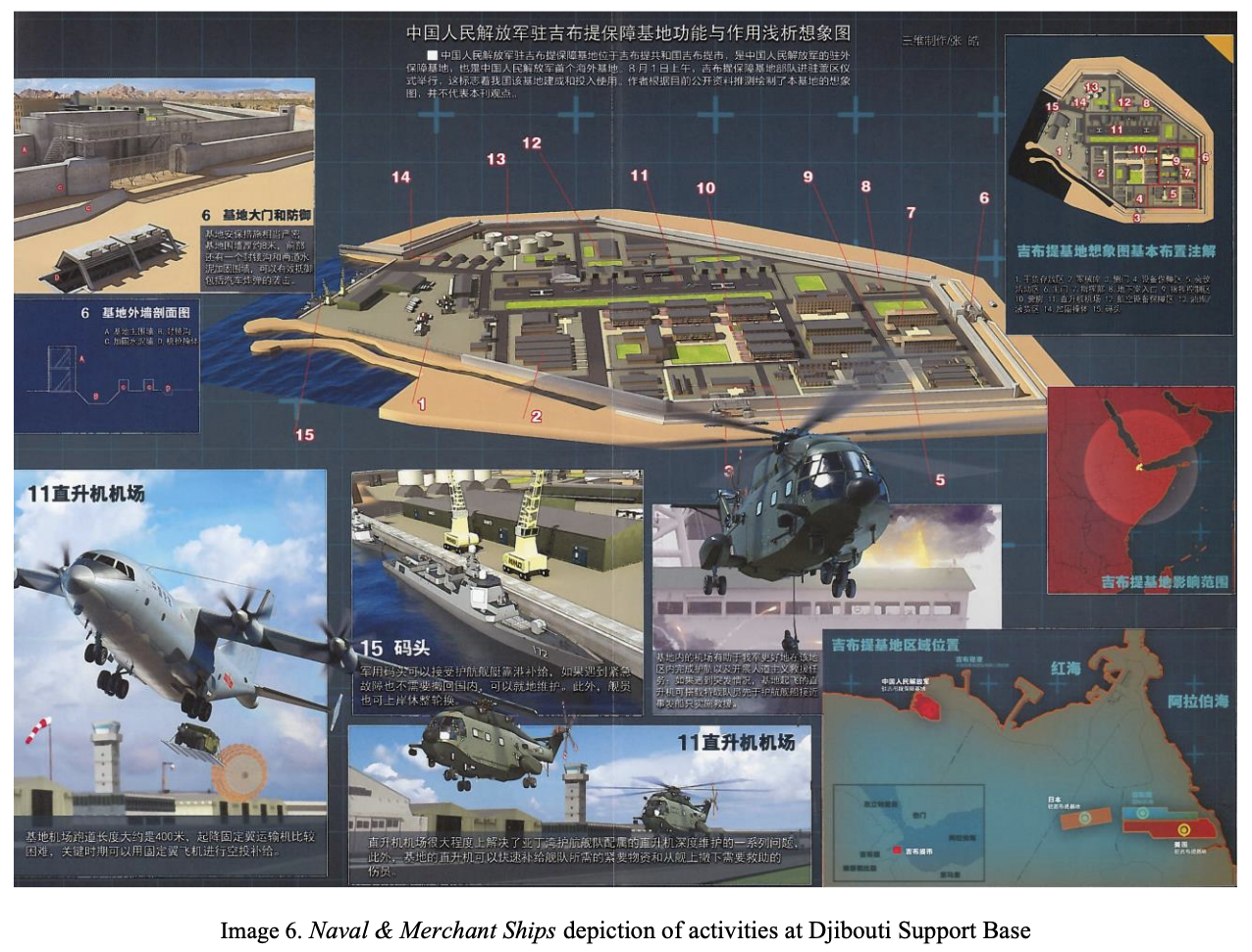

This report analyzes PRC economic and military interests and activities in Djibouti. The small, east African nation is the site of the PLA’s first overseas military base, but also serves as a major commercial hub for Chinese firms—especially in the transport and logistics industry. We explain the synthesis of China’s commercial and strategic goals in Djibouti through detailed examination of the development and operations of commercial ports and related infrastructure. Employing the “Shekou Model” of comprehensive port zone development, Chinese firms have flocked to Djibouti with the intention of transforming it into a gateway to the markets and resources of Africa—especially landlocked Ethiopia—and a transport hub for trade between Europe and Asia. With diplomatic and financial support from Beijing, PRC firms have established a China-friendly business ecosystem and a political environment that proved conducive to the establishment of a permanent military presence. The Gulf of Aden anti-piracy mission that justified the original PLA deployment in the region is now only one of several missions assigned to Chinese armed forces at Djibouti, a contingent that includes marines and special forces. The PLA is broadly responsible for the security of China’s “overseas interests,” for which Djibouti provides essential logistical support. China’s first overseas strategic strongpoint at Djibouti is a secure commercial foothold on the African continent and a military platform for expanding PLA operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

***

Conor M. Kennedy, Civil Transport in PLA Power Projection, China Maritime Report 4 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, December 2019).

Summary

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has ambitious goals for its power projection capabilities. Aside from preparing for the possibility of using force to resolve Beijing’s territorial claims in East Asia, it is also charged with protecting China’s expanding “overseas interests.” These national objectives require the PLA to be able to project significant combat power beyond China’s borders. To meet these needs, the PLA is building organic logistics support capabilities such as large naval auxiliaries and transport aircraft. But it is also turning to civilian enterprises to supply its transportation needs. Since 2012, the PLA has taken major steps to improve its ability to leverage civilian carriers as part of the strategic projection support forces in support of military operations. It has developed strategic projection support ship fleets, comprising civilian-operated roll-on/roll-off, container, tanker, and semi-submersible ships. It has also integrated civilian aviation enterprises into strategic projection support aircraft fleets. To facilitate the staging of military forces for projection beyond China’s borders, the PLA has improved its ability to use China’s modern rail networks and trucking fleet. The PLA has also developed its first strategic projection base, a specialized center of logistics expertise intended to serve PLA power projection requirements through civil-military fusion. To be sure, China’s strategic projection support forces must overcome several challenges before they can fully meet the needs of the PLA. In some cases, training is lax and national defense standards are outdated, or not fully implemented. The PLA itself, which is currently in the midst of a major reform, must also improve its ability to integrate civilian carriers into its combat and support operations. However, the PLA is already taking steps to overcome these challenges, and the PLA logistics community is energetically developing new approaches to better leverage China’s enormous civil transportation sector to meet Beijing’s current and future power projection requirements.

Introduction

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has undergone significant transformation over the past several years through reforms enacted by Chairman Xi Jinping. Accompanying major changes in senior leadership, organization, and force structure are growing efforts by the PLA to boost its power projection capabilities. Much analysis of Chinese military development tends to focus on the emblematic platforms of long-range power projection: large warships and military aircraft.1

But the PLA also relies on civilian carriers—ships, airplanes, trains, and trucks—to support its power projection needs. Since the 18th Party Congress (November 2012), the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has taken major steps to improve its ability to leverage civilian carriers to serve the Chinese military. This is an important, but understudied, aspect of China’s military development.

This report seeks to help close this gap in the literature. It examines efforts by the PLA to strengthen what it calls “new-type strategic projection forces.”2 Aside from the PLA’s own organic lift capabilities, this includes civilian transport systems and platforms that could be leveraged in a crisis or conflict. Much of this effort has been aimed at improving the PLA’s ability to project power over water and across long distances—to the frontiers of Chinese-claimed territory in maritime East Asia, and to countries and oceans around the world where Chinese “overseas interests” are concentrated. These developments therefore have huge implications for the U.S. and its allies and partners in this period of growing great power competition.

This report comprises four main parts. Part 1 introduces the PLA concept of strategic projection and the drivers behind the PLA’s recent prioritization of strategic power projection force development. Part 2 outlines the legal and organizational foundations for PLA employment of civilian carriers for military purposes. Part 3—the bulk of the report—describes force development in strategic sea lift, strategic airlift, rail and road projection, and strategic projection bases, focusing heavily on support capabilities derived from civilian carriers. The report concludes with a discussion of challenges the PLA must overcome before it can fully leverage civilian carriers to achieve the power projection capabilities it desires.

China’s Strategic Power Projection Needs

The PLA defines “strategic power projection” (战略投送) as “actions to comprehensively use a variety of transportation forces to insert forces into an area of operations or crisis in order to achieve specific strategic objectives.”3 These transportation forces include organic PLA transportation supporting forces, such as PLA Air Force (PLAAF) Y-20 transport aircraft or the PLA Navy’s (PLAN) Type-071 Landing Platform Dock (LPD) vessels. They also comprise national civilian transportation resources—the focus of this report.

Strategic projection capabilities are vital to the success of any likely military scenario involving China. In East Asia, the PLA must be prepared to project power over water in order to seize and defend disputed islands, including Taiwan. To achieve these aims, the PLA could be asked to fight what it calls an “informatized limited war” (信息化局部战争—sometimes translated as “informatized local war”).4 It must also be prepared for a range of other combat operations along its periphery, including an intervention in North Korea.

But China’s interests are not confined to maritime East Asia. The need to defend China’s expanding “overseas interests” (海外利益) is often cited as a key driver behind efforts to augment the PLA’s ability to project power over long distances.5 China’s overseas interests include the security of Chinese citizens and property in foreign lands and the security of sea lines of communication.6 Indeed, experts in the PLA are increasingly advocating for the improvement of “cross-border, transoceanic long-range projection capabilities” (跨境越洋远程投送能力).7

Power projection capabilities also serve valuable strategic purposes even when they are not used. Demonstrating the ability to project power beyond China’s borders helps influence the strategic calculus of foreign decision makers. It is therefore integral to deterrence, crisis control, and war prevention, and maintenance of the initiative in almost any scenario.8

China’s strategic projection needs are not static. Indeed, they seem to be increasing on the basis of an explicit timeline. This timeline was outlined by the chief of staff of the Central Military Commission’s (CMC) Transport and Projection Bureau Liu Jiasheng in a February 2019 article.9 Liu describes three phases:

- In the short-term, the military must be ready to fight and win an informatized limited war in the maritime direction. To this end, the PLA will focus on greater development of strategic sea and air lift forces. Efforts will include implementing technological advancements in self- loading trucks, fast passenger roll-on/roll-off (RO-RO) ships, large strategic transport aircraft, unmanned platforms, and precision projection systems.

- In the medium-term, the PLA will focus on developing the ability to project power to “countries and regions along the ‘Belt and Road’ and areas crucially related to key interests around the globe.” The focus of the PLA’s preparation for military struggle will be “fighting and winning an overseas informatized limited war or controlling a major crisis.” To this end, the PLA will develop unmanned projection systems on land, sea and air, with significant focus on precision air projection capabilities.

- In the long-term, the PLA will primarily focus on “global projection.” It will rely on China’s overseas bases and air and space multi-dimensional projection systems to meet the rapid reaction requirements of transportation projection capabilities, in the event of a war anywhere around the globe. Future developments will include high-speed cargo rail, high-performance sea and air platforms, hypersonic transport aircraft, coordinated robotics and unmanned systems in automated transportation systems, and intelligent unmanned transport decision- making systems.10

To improve strategic projection capabilities, the PLA is constructing its own strategic lift forces, including heavy lift aircraft, military helicopters, large transport ships, amphibious ships, and replenishment ships.11 The PLA began developing its organic strategic lift capabilities relatively late compared to other great powers. Chinese military leaders believe the PLA has a long way to go before it can meet its strategic projection requirements.

To support strategic projection, the PLA is also striving to enhance civil-military fusion in the nation’s maturing transportation infrastructure. The role of civilian carriers in strategic projection operations has become a major area of development in the military. In large part, this is driven by a desire to compensate for shortcomings in the PLA’s own organic lift capabilities. Civilian transportation carriers organized for military transportation support are considered part of the PLA’s strategic projection support forces (战略投送支援力量). … … …

***

Conor M. Kennedy, “Strategic Strong Points and Chinese Naval Strategy,” Jamestown China Brief 19.6 (22 March 2019).

Introduction

On August 1, 2017, China opened its first overseas military base, in the East African nation of Djibouti. This was a landmark event that raised a whole host of questions for Indo-Pacific states: Is Djibouti the first of other bases to come? If so, how many? Where will China build them? How will they be used? Where do they fit into Chinese military strategy? Chinese policymakers and analysts are pondering these same questions. However, they are employing concepts unique to Chinese strategic discourse, and it is essential to grasp these concepts in order to understand how Beijing intends to project military power abroad.

For the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the term “overseas military base” (haiwai junshi jidi, 海外军事基地) carries significant historical baggage: foreign imperialists built them on the soil of other countries in order to colonize and exploit them. On the other hand, Chinese policymakers have come to recognize the value of maintaining locations overseas where the Chinese military—above all, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN)—can concentrate resources needed to support operations abroad. To distinguish Chinese actions from the predatory deeds of Western and Japanese imperialists, Chinese military thinkers have adopted a specialized term: the “strategic strong point” (zhanlüe zhidian, 战略支点). [1] A careful analysis of the Chinese use of this concept offers valuable insights into Beijing’s strategic intentions outside of East Asia.

Understanding the “Strategic Strong Point” Concept

The term “strategic strong point” has different meanings, depending on the context in which it is used. In some cases it refers to a quasi-alliance relationship; in other cases, it is used in the context of overseas ports (Journal of Strategy and Decision-Making, No. 2, 2017). The 2013 Science of Military Strategy describes them as locations that “provide support for overseas military operations or act as a forward base for deploying military forces overseas” (Military Science Publishing, December 2013). The PLAN’s new facility in Djibouti has been called China’s first “overseas strategic strong point” (World Affairs, July 26, 2017).

The term is not just applied to Chinese bases: U.S. bases in the Pacific and Indian Oceans are also sometimes described as strategic strong points, and Chinese observers have spent considerable time examining these bases in order to inform their own thinking on developing overseas strategic strong points. Between 2016 and 2017, the PLAN’s official magazine Navy Today ran a series of articles, each one discussing the features and strategic roles of individual U.S. bases. One refers to Pearl Harbor as a “strategic strong point in America’s forward defense,” without which its defensive lines would be limited to the homeland (Navy Today, June 24 2016). Two others describe the roles of Diego Garcia and Guam as strategic strong points critical to Washington’s global strategy. [2]

However, Chinese experts are quick to point out that China’s strategic strong points are fundamentally different from those of other states. They state that China’s strategic strong points offer benefits to host states and provide them with public security goods. Moreover, these sites will not be used to conduct offensive operations, as is the case with the overseas bases of other states. [3]

The Need for Strategic Strong Points

Strategic strong points will improve the Chinese military’s ability to operate overseas. Currently, the PLAN conducts the vast majority of the PRC’s military missions abroad. The PLAN serves two primary functions: protecting China’s sea lines of communication (SLOCs), and safeguarding China’s overseas interests. Both require forward presence in strategically important areas of the Indo-Pacific. According to the Science of Military Strategy, an expansion of the geographic scope of naval operations requires the establishment of replenishment points and “various forms of limited force presence” (Science of Military Strategy, December 2013).

Strategic strong points fulfill these demands. An engineer at the Academy of Military Science’s Institute of Logistics explains that overseas strategic strong points will support the military’s long-range projection capabilities by effectively shortening resupply intervals and expanding the range of support for Chinese forces operating abroad (National Defense, December 2017). However, replenishment ships alone cannot meet the Navy’s needs. As the deputy chief of the PLAN Operations Department wrote in 2010, personnel relief, equipment servicing, and the uncertainties of foreign berthing facilities were limiting factors in the long-term regularization of overseas operations. Chinese facilities in overseas ports are the next step in building an “overseas support system.” [4]

PLAN Commander Adm. Wu Shengli talked about the importance of strategic strong points in December 2016, during an event commemorating the eighth anniversary of China’s anti-piracy operation off the Horn of Africa. Wu Shengli pointed out that “overseas strategic strong point construction has provided a new support for escort operations… We must give full play to the supporting role of the overseas support system to carry out larger scale missions in broader areas and to shape the situation.” [5]

Establishing several strategic strong points near crisis regions is integral to ensuring the sustained and effective use of forces in these roles. [6] When incidents and crises erupted in the past, efforts to protect China’s overseas interests were highly reactive. Strategic strong points allow China to gradually shift its posture to stabilize and control situations before they become crises. They might even play a role in stabilizing local governments and economies, and in ensuring civil order (International Herald Tribune, October 13 2015).

Accurate and timely intelligence is vital to effective operations, and PLA thinkers believe that strategic strong points will serve intelligence support functions. [7] Two authors from the PLA Equipment Academy write about the PLAN’s development of a “sea & space battlefield versatile situation picture” that integrates various intelligence sources to provide real-time visualized information support for the PLAN’s overseas actions. This system, they state, will support the PLAN’s defensive strategy in its strategic strong points, maritime passages, and core interest areas (Journal of Equipment Academy, April 2017). … … …

***

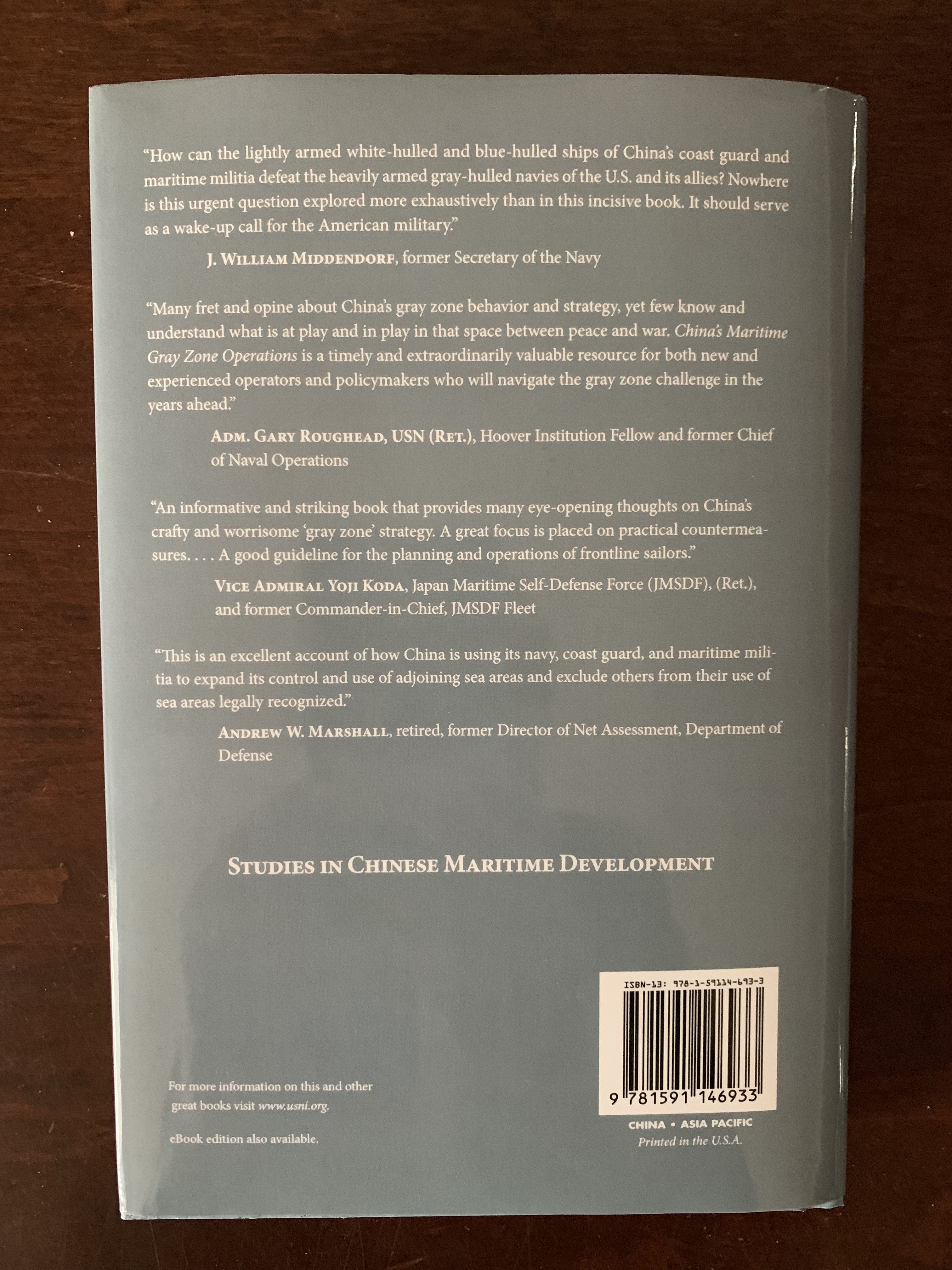

Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, eds., China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019).

As with the previous six volumes in our “Studies in Chinese Maritime Development” series, an Amazon Kindle edition is available.

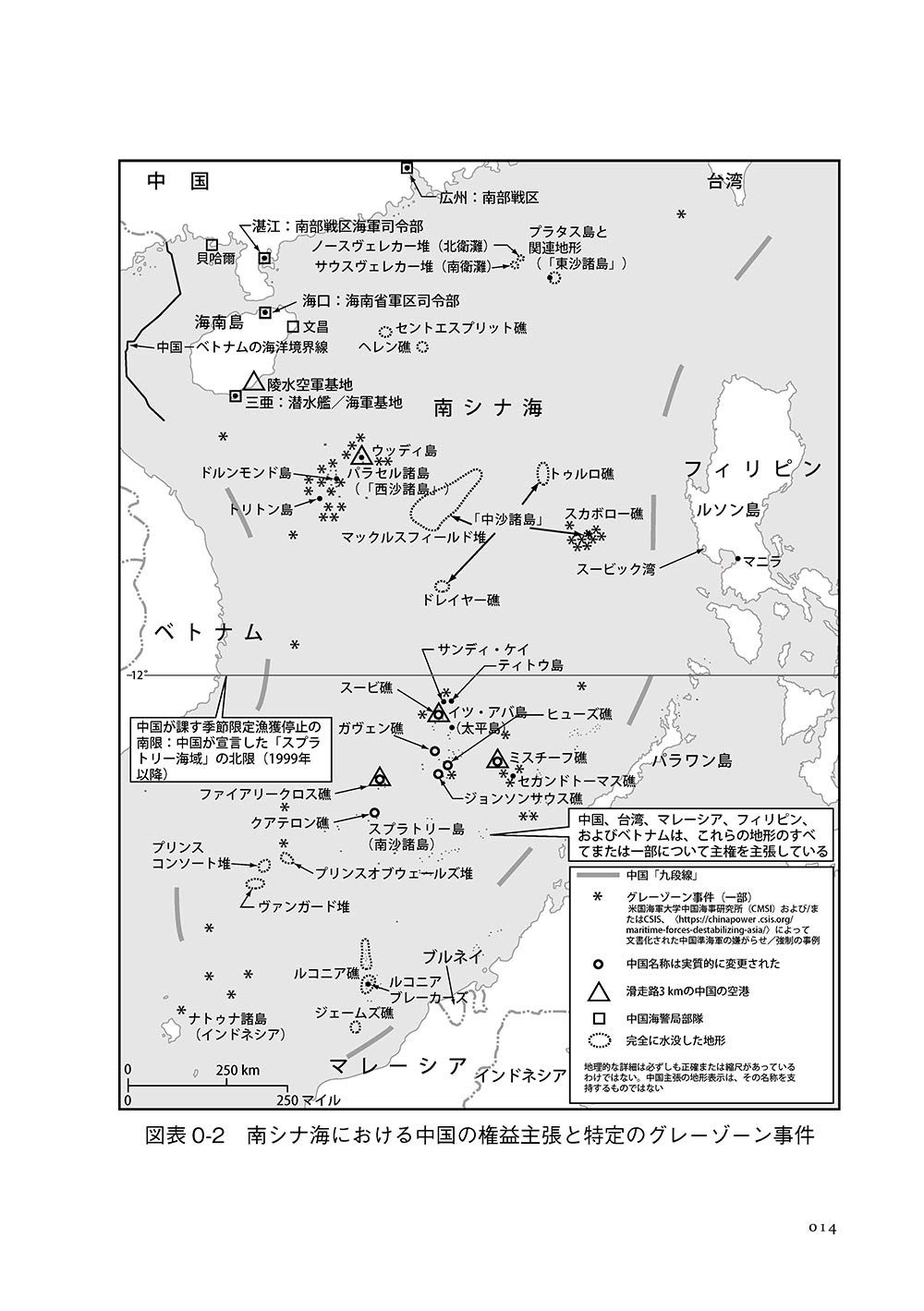

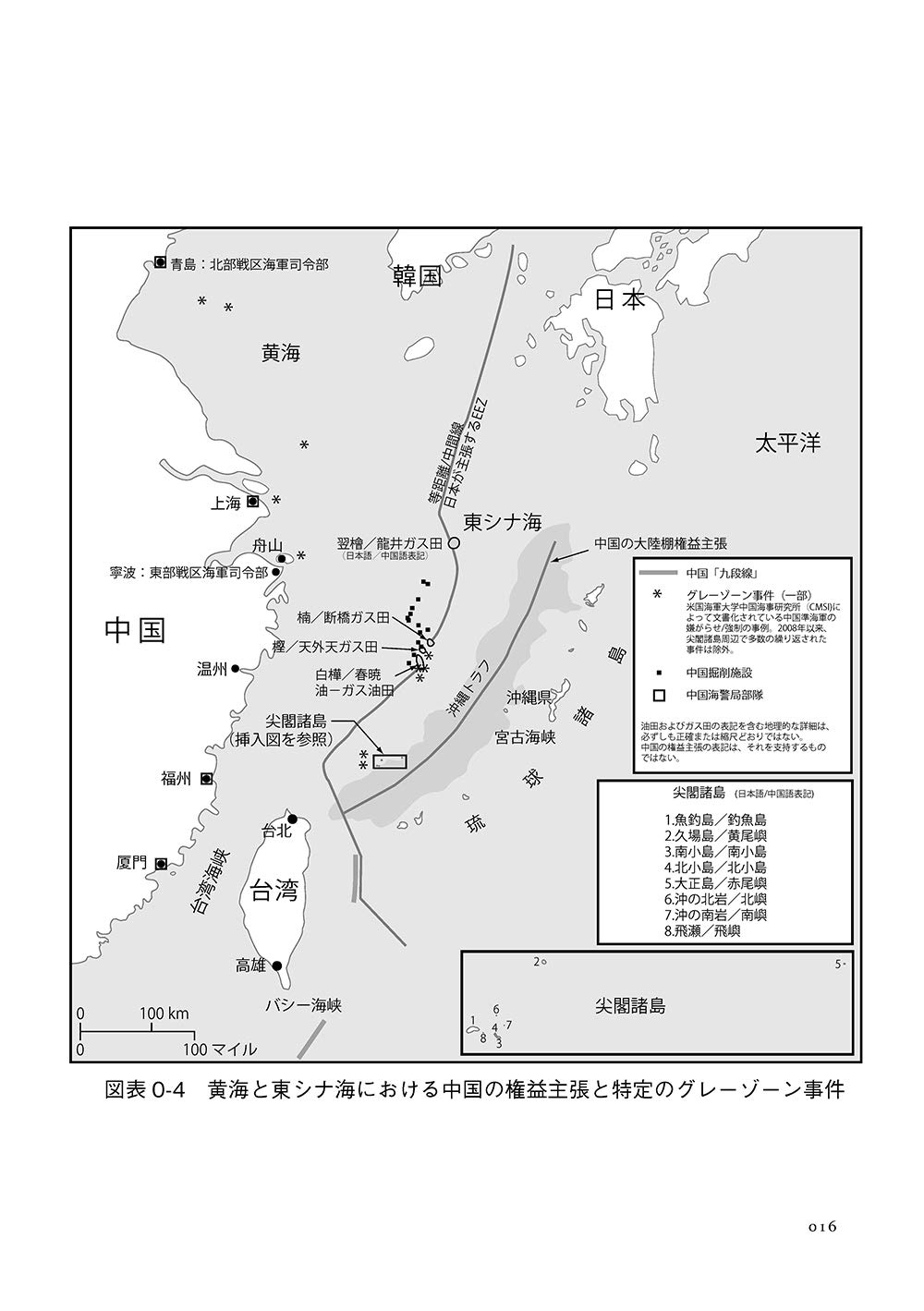

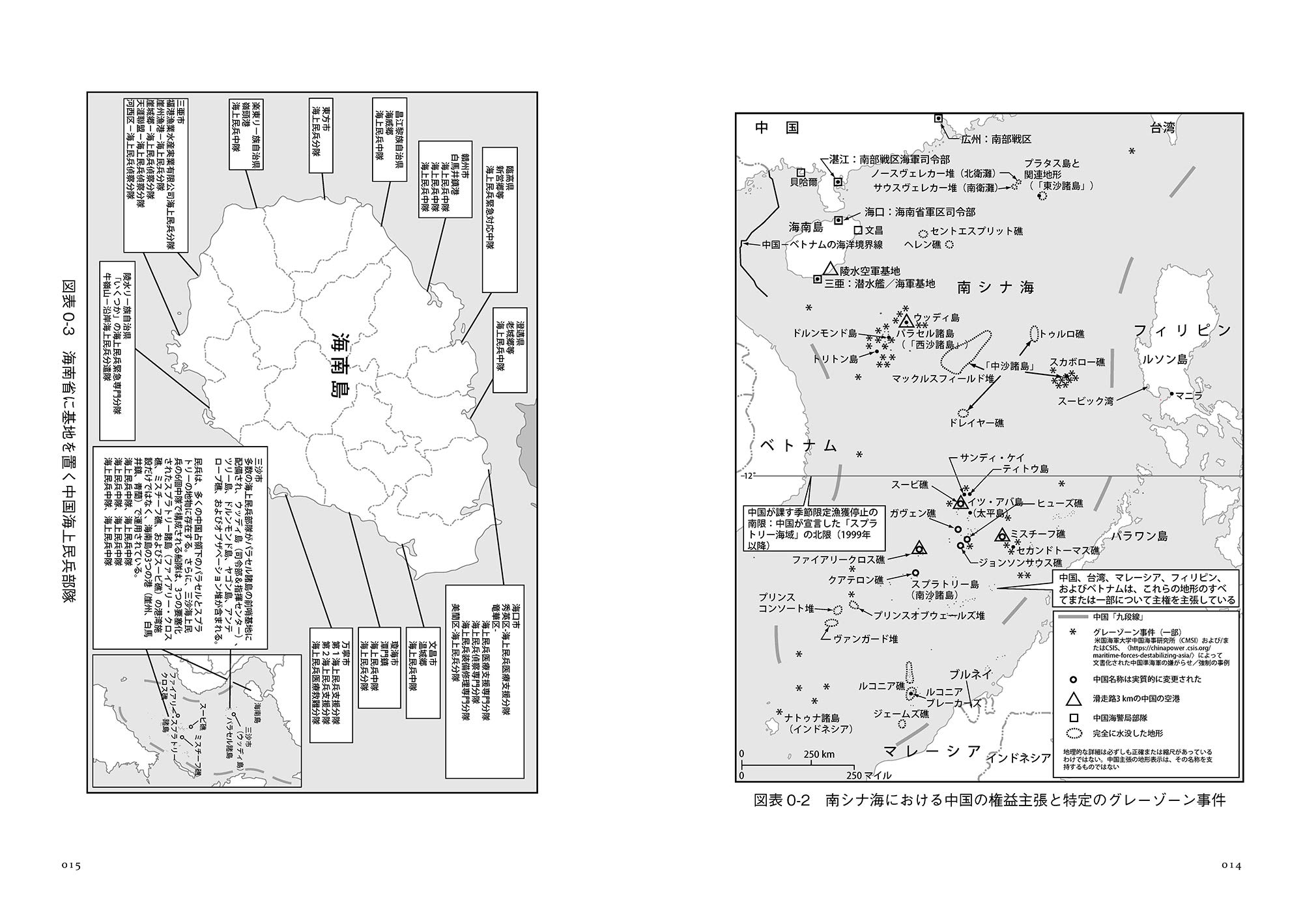

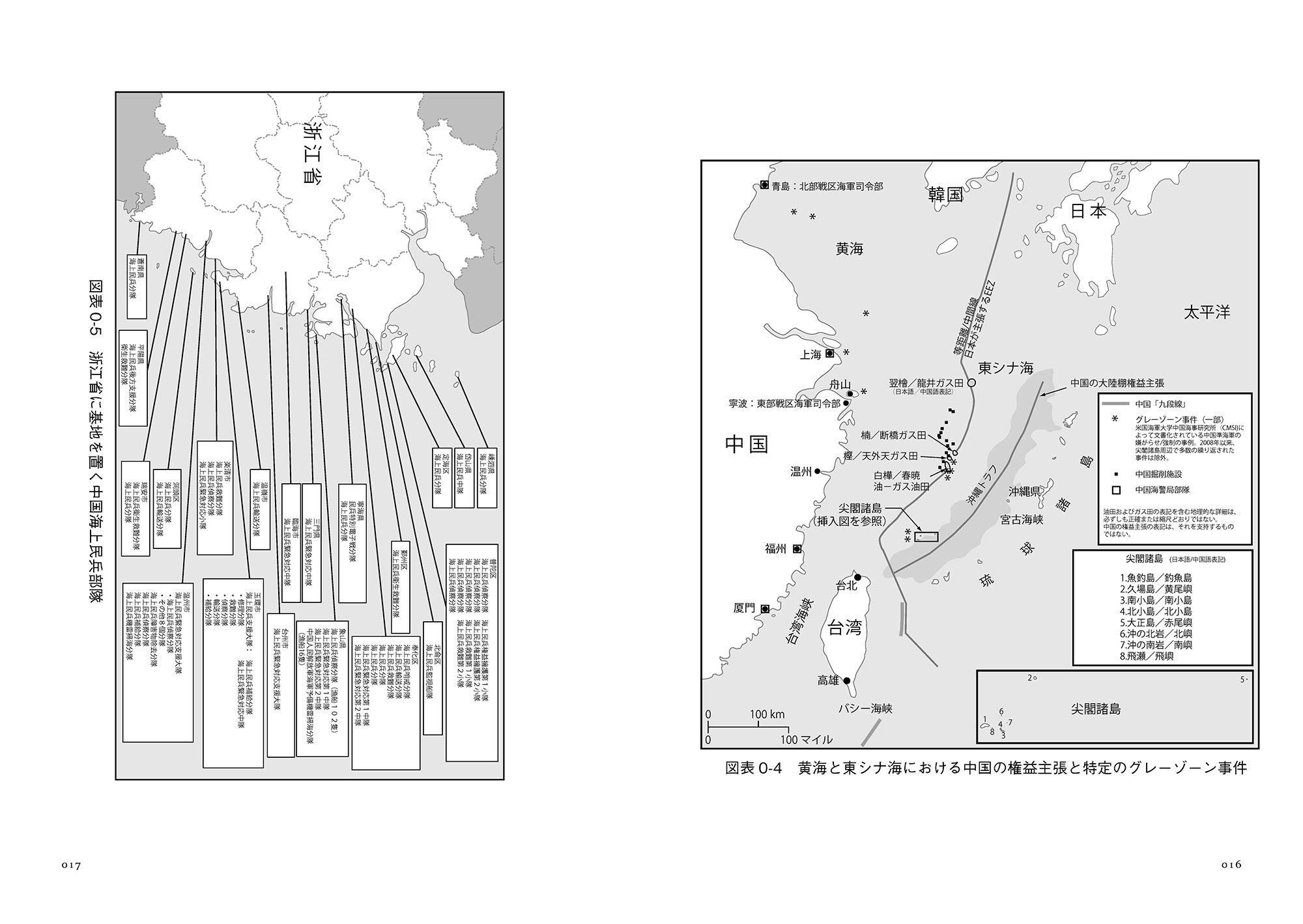

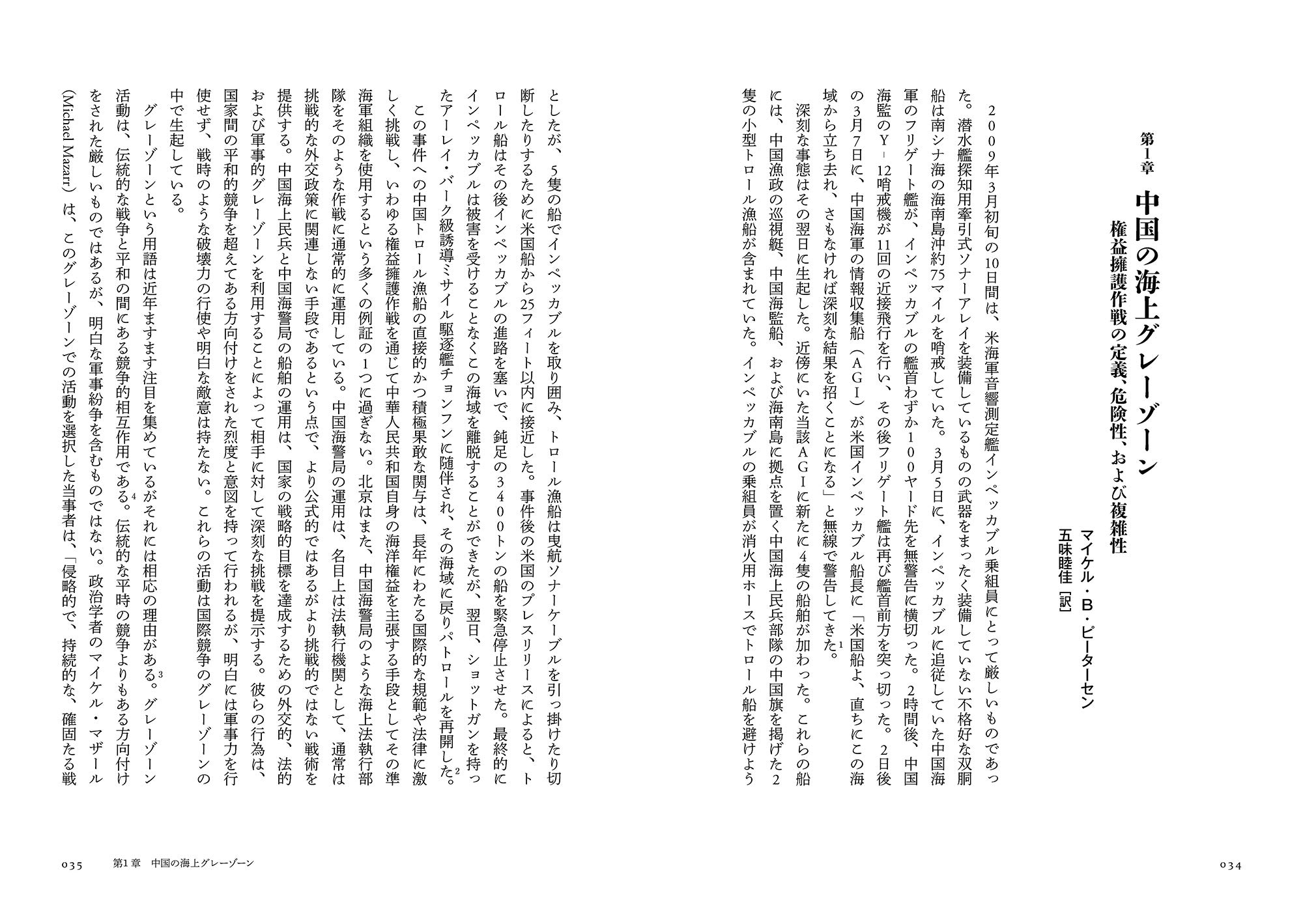

- Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Introduction: ‘War Without Gun Smoke’—China’s Paranaval Challenge in the Maritime Gray Zone,” 1-11.

- Joshua Hickey, Andrew S. Erickson, and Henry Holst, “China Maritime Law Enforcement Surface Platforms: Order of Battle, Capabilities, and Trends,” 108-132.

- Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Conclusion: Options for the Definitive Use of U.S. Sea Power in the Gray Zone,” 291-301.

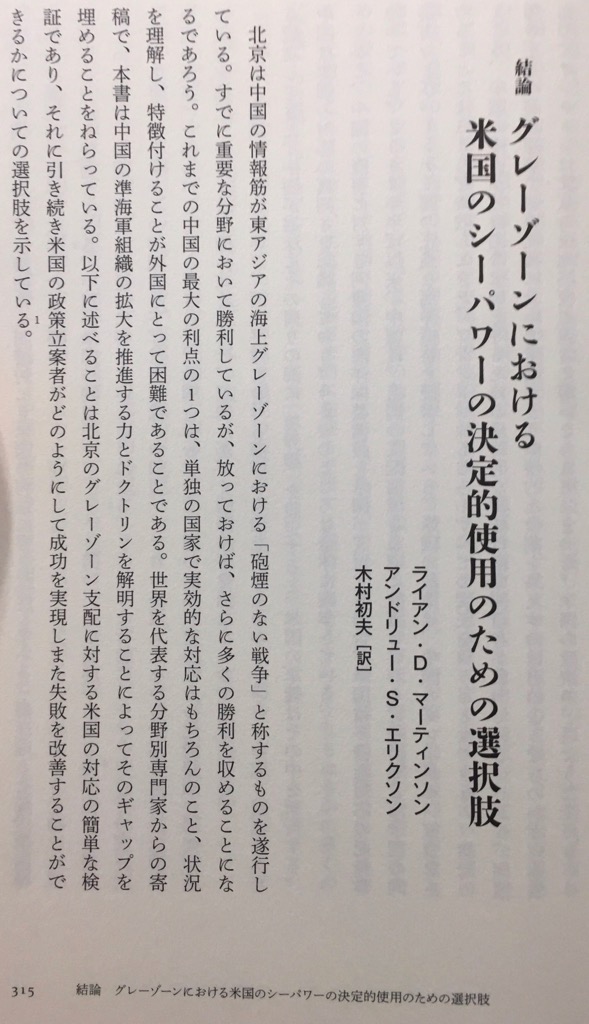

Reprinted in Japanese as: アンドリュー・S・エリクソン (編集), ライアン・D・マーティンソン (編集), 五味 睦佳 (翻訳), 大野 慶二 (翻訳), 木村 初夫 (翻訳), 五島 浩司 (翻訳), 杉本 正彦 (翻訳), 武居 智久 (翻訳), 山本 勝也 (翻訳) [Andrew S. Erickson (Editor), Ryan D. Martinson (Editor), Gumi Mutsuka (Translator), Ohno Keiji (Translator), Kimura Hatsuo (Translator), Goto Koji (Translator), Sugimoto Masahiko (Translator), Tomohisa Takei (translator), and Katsuya Yamamoto (translator)]; 中国の海洋強国戦略:グレーゾーン作戦と展開 (日本語) [China’s Maritime Power Strategy: Strategy and Deployment in Gray Zone (Japanese translation of China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations)] (Tokyo: 原書房 [Hara Shobo Press], 2020).

- アンドリュー・S・エリクソン, ライアン・D・マーティンソン [Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson], “序論 「砲煙なき戦争」” [Introduction: “War Without Gun Smoke”—China’s Paranaval Challenge in the Maritime Gray Zone], 19-32.

- ジョシュア・ヒッキー, アンドリュー・S・エリクソン, ヘンリー・ホルスト [Joshua Hickey, Andrew S. Erickson, and Henry Holst], “第7章 中国の海上法執行海上プラットフォーム” [Chapter 7: China Maritime Law Enforcement Surface Platforms: Order of Battle, Capabilities, and Trends], 128-53.

- ライアン・D・マーティンソン, アンドリュー・S・エリクソン [Ryan D. Martinson and Andrew S. Erickson], “結論 グレーゾーンにおける米国のシーパワーの決定的使用のための選択肢” [Conclusion: Options for the Definitive Use of U.S. Sea Power in the Gray Zone], 315-27.

China’s maritime “gray zone” operations represent a new challenge for the U.S. Navy and the sea services of our allies, partners, and friends in maritime East Asia. There, Beijing is waging operations conducted to alter the status quo without resorting to war, an approach that some Chinese sources term “War without Gun Smoke” (一场没有硝烟的战争). Already winning in important areas, China could gain far more if left unchecked. One of China’s greatest advantages thus far has been foreign difficulty in understanding the situation, let alone determining an effective response. With contributions from some of the world’s leading subject matter experts, this volume aims to close that gap by explaining the forces and doctrines driving China’s paranaval expansion.

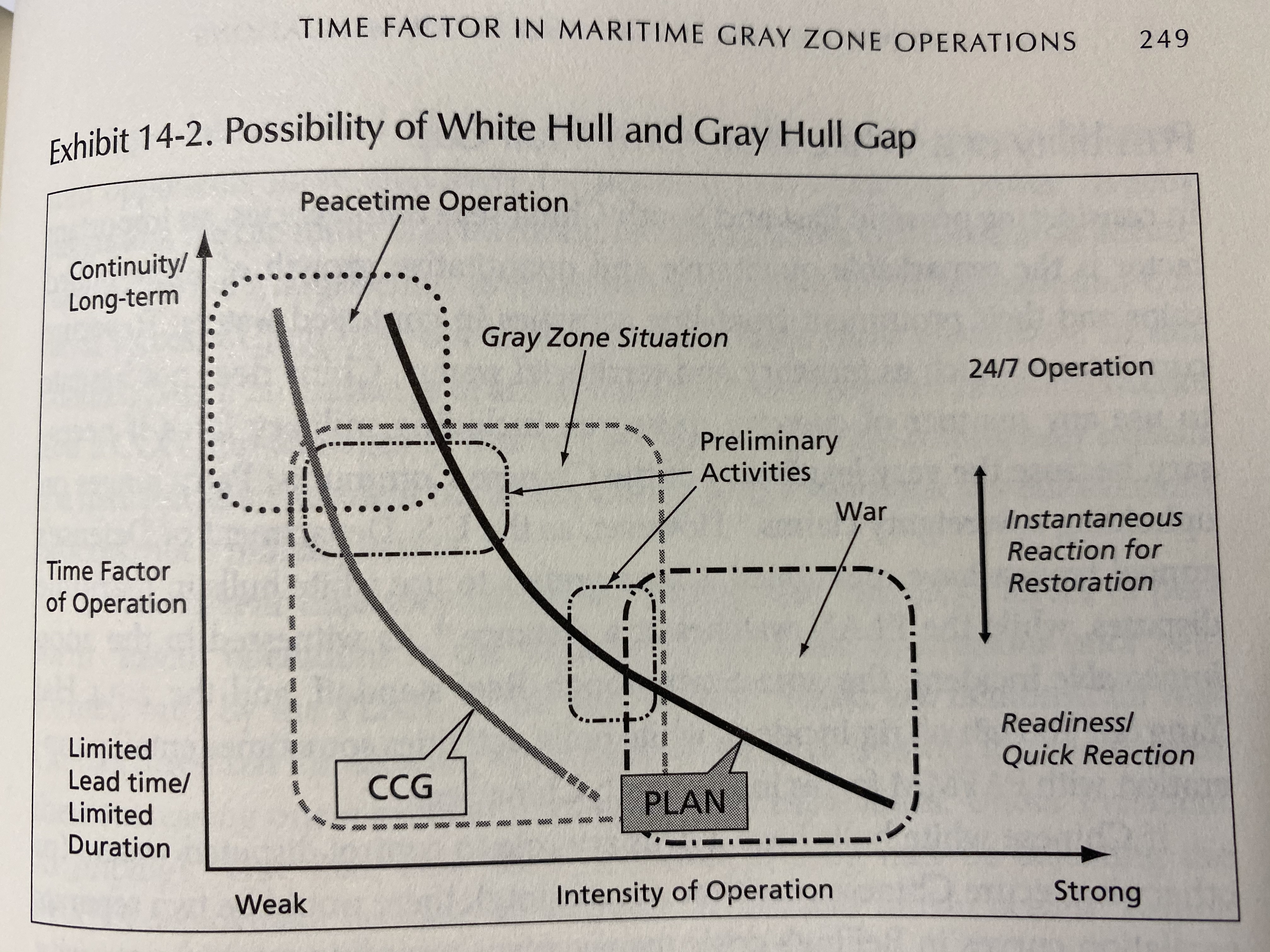

The book therefore covers in-depth China’s major maritime forces beyond core gray-hulled Navy units, with particular focus on China’s second and third sea forces: the “white-hulled” Coast Guard and “blue-hulled” Maritime Militia. Increasingly, these paranaval forces are on the frontlines of China’s seaward expansion, operating in the “gray zone” between war and peace: where the greatest action is. Beijing works constantly in peacetime (and possibly in crises short of major combat operations with the United States) to “win without fighting” and thereby to further its unresolved land feature and maritime claims in the Near Seas (Yellow, East, and South China Seas). There is an urgent need for greater understanding of this vital yet under-explored topic: this book points the way.

March 2019 | 336 pp. | 6 x 9 | China and the Asia-Pacific

Maps | Hardcover

ASIN: 1591146933

ISBN-13: 978-1591146933

BOOK DESCRIPTION

As Washington’s new National Security Strategy emphasizes, China is engaged in continuous competition with the United States–neither fully “at peace” nor “at war.” Per this national guidance, the U.S. Navy must raise its competitive game to meet that challenge, in part by addressing the potential risks to American interests and values posed by all three Chinese sea forces: the Navy, Coast Guard, and Maritime Militia. In terms of ship numbers, each is the largest of its type in the world.

China’s maritime “gray zone” operations represent a new challenge for the U.S. Navy and the sea services of our allies, partners, and friends in maritime East Asia. There, Beijing is waging what some Chinese sources term a “war without gunsmoke.” One of China’s greatest advantages thus far is the difficulty for foreign powers to understand the situation, let alone determine an effective response. With contributions from some of the world’s leading subject matter experts, this volume aims to close that gap by explaining the forces and doctrines driving China’s paranaval expansion.

This book covers China’s major maritime forces beyond core gray-hulled Navy units, with particular focus on China’s second and third sea forces: the “white-hulled” Coast Guard and “blue-hulled” Maritime Militia. Increasingly, these paranaval forces are on the frontlines of China’s seaward expansion, operating in the “gray zone” between war and peace.

Chinese behavior at sea harms U.S. interests both directly and indirectly. As a seafaring state, America demands maximal access to the world’s oceans within the constraints of international law. Actions that impede that access violate America’s maritime freedom. China harms U.S. interests indirectly when it violates the legitimate maritime freedom and maritime rights of its allies and partners. Such acts devalue Washington’s commitments to its friends and shake the foundations of our alliance system–the true source of America’s global influence. Moreover, China’s efforts to curtail and infringe upon both the maritime freedom of all nations including the United States and the maritime rights of its neighbors undermines the rules-based international order. This volume concludes by examining America’s response to Beiing’s gray zone coercion and suggests what U.S. policymakers can do to counter it.

BLURBS

“How can the lightly armed white-hulled and blue-hulled ships of China’s coast guard and maritime militia defeat the heavily armed gray-hulled navies of the U.S. and its allies? Nowhere is this urgent question explored more exhaustively than in this incisive book. It should serve as a wake-up call for the American military.”

—J. William Middendorf, former Secretary of the Navy

“Many fret and opine about China’s gray zone behavior and strategy, yet few know and understand what is at play and in play in that space between peace and war. China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations is a timely and extraordinarily valuable resource for both new and experienced operators and policymakers who will navigate the gray zone challenge in the years ahead.”

—Admiral Gary Roughead, U.S. Navy (Ret.), Hoover Institution Fellow and former Chief of Naval Operations

“Who needs the CIA? Maritime competition represents the front lines in the struggle for influence between China and the United States. Gray hulls are not the only way Beijing tries to shift the balance. China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations provides as comprehensive an assessment of the challenge as one might expect from Langley.”

—James Jay Carafano, Ph.D., The Heritage Foundation

“Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson have established themselves as two of America’s most knowledgeable analysts of the PLA Navy and China’s naval strategy. Their new work on China’s maritime gray zone operations deepens our understanding of Chinese maritime operations that are neither peace nor war but that could have a profound impact on the western Pacific, Japan, and the role of the U.S. in Asia.”

—Stephen P. Rosen, Beton Michael Kaneb Professor of National Security and Military Affairs, Harvard University

“An informative and striking book, which provides many eye-opening thoughts on China’s crafty and worrisome ‘gray zone’ strategy. A great focus is placed on practical countermeasures…. A good guideline for the planning and operations of frontline sailors.”

—Vice Admiral Yoji Koda, Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) (Ret.) and former Commander-in-Chief, JMSDF Fleet

“This is an excellent account of how China is using its navy, coast guard, and maritime militia to expand its control and use of adjoining sea areas and exclude others from their use of sea areas legally recognized.”

—Andrew W. Marshall, retired, former Director of Net Assessment, Department of Defense

REVIEWS

“a real contribution to our understanding of China’s gray zone operations… provides an excellent assessment of China’s paranaval capabilities. …the chapters in Parts 2 and 3 of the volume are strongly recommended for their clear and in-depth treatment of the history, organization, operations, and assets of the China Coast Guard and the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia. …the authors…provide sound assessments of China’s policy, institutional, and material advantages and limitations in conducting gray zone operations. …recommended to both specialists and nonspecialists.”

—Dr. John W. Tai, The Air Force Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs 3.1 (Spring 2020): 95-96.

“China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations is the seventh edited volume in the Studies in Chinese Maritime Development series published in collaboration with the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. In common with its predecessors this book has been produced to a consistently high standard. Collectively the series represents some of the leading available scholarship on China’s maritime power. This most recent volume is both focused and timely, addressing China’s strategy of coercively manipulating changes to the geopolitical status quo in East Asian waters via the employment of maritime operations in the ‘gray zone.’ … Well-conceived maps and diagrams complete the whole. …the book tells an overarching story of the success of China’s maritime gray zone operations in fulfilling its regional objectives thus far, especially in the South China Sea. This collection is without doubt the most comprehensive source available on the subject, providing a uniformly excellent quality of scholarship. Given the very recent changes outlined in the book, this is a story that will continue to unfold, but as a guide to understand the slow-burning crisis in East Asian seas so far, China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations is highly recommended.”

—Chris Rahman, Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources & Security, Marine Policy 110 (December 2019).

“During this same period of an economically rising China, the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute became a leading center for analyzing China’s naval power. Two of the Institute’s mainstays, Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson, again have contributed to our understanding by assembling and editing twenty papers prepared for a 2017 conference on what could turn out to be the most significant component of China’s modus operandi at sea: exploitation of the so-called gray zone. … The papers collected in this new work…can help us better understand this maneuvering and meet the challenges the West already faces—challenges that only will grow as China’s naval strength and presence grow.”

—Charles Horner, Naval War College Review 72.4 (2019): 176-77.

“Erickson and Martinson have further etched themselves into the community of heavy-weight strategists, working with an assortment of outstanding authors and building on their reputation as staunch intellectuals who keenly grasp the nuances of Chinese maritime strategy, particularly gray zone operations. …Erickson and Martinson have brought together a significant publication that illuminates a critically dim section in an area broadly considered as over-done. …provides the reader with a comprehensive exploration of the evolving nature of Chinese behaviour in the South China Sea and notably, the chance to do so from 22 different perspectives. …charts a fluid, logical advance from conceptualization to components, to scenarios and finishing with policy considerations. …The reviewer was left with an enduring impression of: the clarity with which the foundation of the topic is described in Part 1; the conciseness and transparency of the often misunderstood aspects of the China Coast Guard (CCG) in Part 2; the accurate identification and description of the ‘gray area’ of China’s Maritime Militia in Part 3; the specificity and application of poignant events in Part 4; and, well-considered, robust policy considerations in Part 5. …offers the reader a brilliant opportunity to traverse contemporary considerations of the South China Sea’s gray zone mechanism. … Highly recommended reading.”

—Lt. Mitchell Vines, RAN,The Australian Naval Institute, 14 July 2019.

“An essential read for those seeking to understand and achieve the sort of asymmetric offshore counter balancing that regional powers [together] with the U.S. are likely to require if they are [to] live long and prosper alongside the Dragon’s den.”

—Navy Magazine, Navy League of Australia 81.3 (2019): 31.

“the book provides a cornerstone of what is happening now in addition to where things are likely headed. …certain to enlighten you.”

—Virtual Mirage, 6 April 2019.

“… a first rate piece of work. …the discussions of the book could be seen as a historic look at a phase of Chinese maritime power and the evolving approach to strategic engagement in the region and beyond. … I would highly recommend reading this important book and thinking through what it teaches us, or challenges us to think about in terms of the much broader spectrum of crisis management we are facing.”

—Robbin Laird, Defense Info, 26 March 2019.

ABOUT THE EDITORS

Andrew S. Erickson is professor of strategy in the Naval War College (NWC)’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) and an associate in research at Harvard’s Fairbank Center. The recipient of NWC’s inaugural Research Excellence Award, he runs the China studies website www.andrewerickson.com.

Ryan D. Martinson is an assistant professor at CMSI. He holds a master’s degree from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and a bachelor’s of science from Union College. Martinson has also studied at Fudan University, the Beijing Language and Culture University, and the Hopkins-Nanjing Center.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Morgan Clemens is a Research Analyst at SOS International LLC.

Peter A. Dutton, a retired U.S. Navy Commander and judge advocate, is Professor and Director at CMSI.

Matthew Funaiole is a fellow with the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Bonnie S. Glaser is senior adviser for Asia and director of CSIS’s China Power Project.

Joshua Hickey is a senior analyst for the Department of the Navy with over fifteen years’ subject matter experience.

Henry Holst is a junior analyst for the Department of the Navy.

Conor M. Kennedy is a research associate at CMSI.

Adam P. Liff is an assistant professor at Indiana University’s School of Global and International Studies and an associate in research at Harvard’s Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies.

Michael Mazarr is a senior political scientist and associate director of the strategy and doctrine program at the RAND Corporation’s Arroyo Center.

Barney Moreland, a retired Captain who served as the first U.S. Coast Guard Liaison Officer in Beijing, is the Senior Intelligence Analyst at U.S. Pacific Fleet Headquarters.

Lyle J. Morris is a senior policy analyst at RAND.

Cdr. Jonathan G. Odom, USN, is a judge advocate and military professor at the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies.

Michael B. Petersen is the founding director Russia Maritime Studies Institute and an associate professor in the Center for Naval Warfare Studies at NWC.

Capt. Dale C. Rielage, USN, is Director for Intelligence and Information Operations, U.S. Pacific Fleet.

Mark A. Stokes, a retired U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel, is Executive Director of the Project 2049 Institute.

Austin M. Strange is a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard University’s Government Department.

Admiral Tomohisa Takei, Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) (Ret.) concluded his thirty-seven-year naval career as the JMSDF’s 32nd Chief of Staff, and is now a professor and distinguished international fellow at NWC.

Michael Weber a foreign affairs analyst and Presidential Management Fellow at the Congressional Research Service.

Capt. Katsuya Yamamoto, JMSDF, who served as a Defense/Naval Attaché in Beijing, is a liaison officer and international military professor at NWC.

Previous Titles in the Series

China’s Future Nuclear Submarine Force

China’s Energy Strategy: The Impact on Beijing’s Maritime Policies

China Goes to Sea: Maritime Transformation in Comparative Historical Perspective

China, the United States and 21st-Century Sea Power: Defining a Maritime Security Partnership

Chinese Aerospace Power: Evolving Maritime Roles

Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: An Ambitious and Uncertain Course

アンドリュー・S・エリクソン (編集), ライアン・D・マーティンソン (編集), 五味 睦佳 (翻訳), 大野 慶二 (翻訳), 木村 初夫 (翻訳), 五島 浩司 (翻訳), 杉本 正彦 (翻訳), 武居 智久 (翻訳), 山本 勝也 (翻訳) [Andrew S. Erickson (Editor), Ryan D. Martinson (Editor), Gumi Mutsuka (Translator), Ohno Keiji (Translator), Kimura Hatsuo (Translator), Goto Koji (Translator), Sugimoto Masahiko (Translator), Tomohisa Takei (translator), and Katsuya Yamamoto (translator)]; 中国の海洋強国戦略:グレーゾーン作戦と展開 (日本語) [China’s Maritime Power Strategy: Strategy and Deployment in Gray Zone (Japanese translation of China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations)] (Tokyo: 原書房 [Hara Shobo Press], 2020).

アンドリュー・S・エリクソン (編集), ライアン・D・マーティンソン (編集), 五味 睦佳 (翻訳), 大野 慶二 (翻訳), 木村 初夫 (翻訳), 五島 浩司 (翻訳), 杉本 正彦 (翻訳), 武居 智久 (翻訳), 山本 勝也 (翻訳)

商品の説明

内容紹介

中国の沿岸警備隊に相当する海警局、そして海上民兵による軍事力や戦略・組織について、米海軍大学など世界の専門家がはじめて体系的に分析・紹介。日本にとっても注意が必要な中国の「グレーゾーン」戦略を知る最高の一書といえる。

内容(「BOOK」データベースより)

東シナ海・南シナ海に展開する準海軍「中国海警局」や「中国海上民兵」の実態と係争海域の実効支配を視野に入れた展開のすべて。米海軍大学の専門研究機関があらゆる角度から分析・詳述した決定版!

登録情報

- 単行本: 388ページ

- 出版社: 原書房 (2020/3/19)

- 言語: 日本語

- ISBN-10: 4562057459

- ISBN-13: 978-4562057450

- 発売日: 2020/3/19

- 梱包サイズ: 21.6 x 15.6 x 3 cm

- カスタマーレビュー: 評価の数 5

- Amazon 売れ筋ランキング: 本 – 13,609位 (本の売れ筋ランキングを見る)

- 69位 ─ 国際政治情勢

- 18位 ─ 中国のエリアスタディ

- 189位 ─ 政治入門

中国の沿岸警備隊に相当する海警局、そして海上民兵による軍事力や戦略・組織について、米海軍大学など世界の専門家がはじめて体系的に分析・紹介。日本にとっても注意が必要な中国の「グレーゾーン」戦略を知る最高の一書。

著者・編者紹介

【著者】

モーガン・クレメンス (Morgan Clemens)

SOS International LLCの研究アナリスト。

ピーター・A・ダットン(Peter A.Dutton)

退役米国海軍中佐および法務官、米国海軍大学中国海事研究所(CMSI)所長。

マシュー・P・フネオーレ(Matthew P.Funaiole)

戦略国際問題研究所(CSIS)チャイナ・パワー(中国実力)プレジェクト・フェロー。

ボニー・S・グレイサー(Bonnie S.Glaser)

戦略国際問題研究所アジア担当上級顧問およびチャイナ・パワープロジェクト・ディレクター。

ジョシュア・ヒッキー(Joshua Hickey)

米国海軍省上級分析官(15年以上の専門経験)。

ヘンリー・ホルスト(Henry Holst)

米国海軍省下級分析官。

コナー・M・ケネディ(Conor M.Kennedy)

米国海軍大学中国海事研究所研究員。

アダム・P・リフ(Adam P.Liff)

インディアナ大学グローバル国際問題研究校助教授兼ハーバード大学ライシャワー日本研究所研究員。

マイケル・マザール(Michael Mazarr)

ランド研究所アロヨセンター戦略・ドクトリンプログラムの上級政治学者およびアソシエイト・ディレクター。

バーナード・モアランド(Bernard Moreland)

退役米国沿岸警備隊大佐、米国沿岸警備隊の最初の元北京連絡官。米国太平洋艦隊司令部上級情報分析官。

ライル・J・モリス(Lyle J.Morris)

ランド研究所上級政策アナリスト。

ジョナサン・G・オドム(Jonathan G.Odom)

米国海軍中佐、ダニエル・K・イノウエ・アジア太平洋安全保障研究所法務官兼軍事教授。

マイケル・B・ピーターセン(Michael B.Petersen)

米国海軍大学ロシア海事研究所初代所長兼米国海軍大学海軍作戦研究センター准教授。

デール・C・リエーレ(Dale C.Rielage)

退役米国海軍大佐。米国太平洋艦隊インテリジェンス・情報作戦担当部長。

マーク・A・ストークス(Mark A.Stokes)

退役米国空軍中佐。Project 2049 Institute事務局長。

オースティン・M・ストランジ(Austin M.Strange)

ハーバード大学政治学部博士(PhD)課程。

スコット・H・スウィフト(Scott H.Swift)

退役米国海軍大将、元米国太平洋艦隊司令官(2015~2018年)。

武居智久

退役海上自衛隊海将、元第32代海上幕僚長(37年間の海上自衛隊経験)。現在、米国海軍大学教授兼米国海軍作戦部長特別インターナショナルフェロー。

マイケル・ウェーバー(Michael Weber)

米国議会調査部外交問題アナリストおよび大統領管理フェロー。

山本勝也

海上自衛隊1等海佐、元在北京日本国大使館防衛駐在官。米国海軍大学連絡官兼国際軍事教授(執筆時)。

【編者】

アンドリュー・S・エリクソン(Andrew S.Erickson)

米国海軍大学中国海事研究所戦略担当教授兼ハーバード大学ファエバンク中国研究所研究員。

ライアン・D・マーティンソン(Ryan D.Martinson)

米国海軍大学中国海事研究所助教授。

目次

序文

監訳者所感

序論 「砲煙なき戦争」

第I部 グレーゾーンの概念化

第1章 中国の海上グレーゾーン

第2章 中国の海上グレーゾーン作戦の概念化

第3章 海上民兵は海上における人民戦争(海上人民戦争)を実行しているのか

第4章 グレーゾーンが国際法の基本原則に抵触するとき

第II部 中国海警局とグレーゾーン

第5章 グレーゾーンのための組織改編

第6章 海上グレーゾーンにおける海警局作戦の軍事化

第7章 中国の海上法執行海上プラットフォーム

第III部 中国の海上民兵とグレーゾーン

第8章 権益擁護対戦闘

第9章 中国の海上民兵と偵察・攻撃作戦

第10章 ブルーテリトリー(外洋領域)におけるグレー軍

第IV部 近海グレーゾーンのシナリオ

第11章 南シナ海

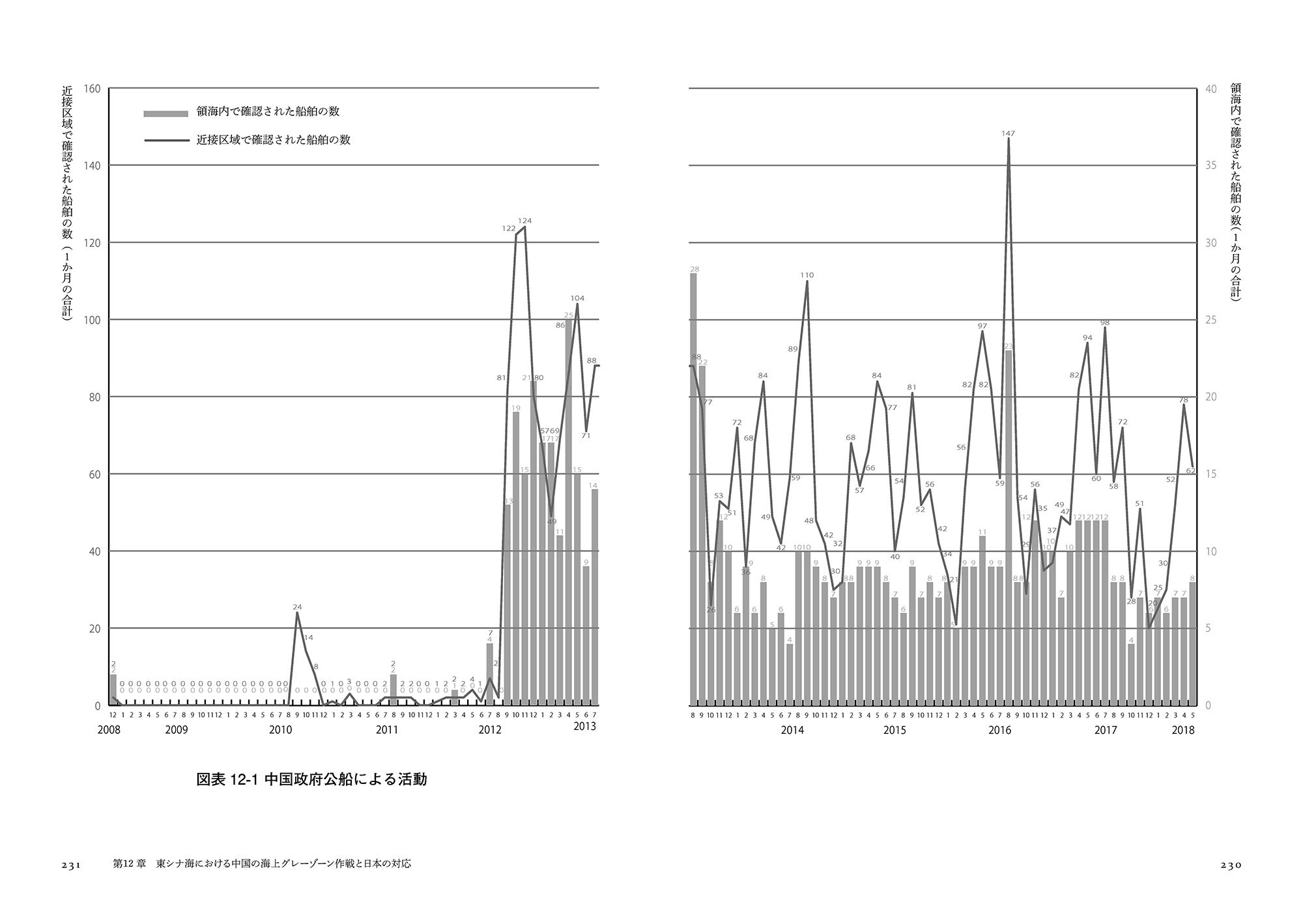

第12章 東シナ海における中国の海上グレーゾーン作戦と日本の対応

第13章 東シナ海

第V部 グレーゾーン政策の課題と提言事項

第14章 グレーゾーンの作戦における時間的要素

第15章 中国のグレーゾーン作戦行動への対応における抑止の役割

第16章 中国との紛争管理における事例研究としてのベトナムおよびフィリピン

結論 グレーゾーンにおける米国のシーパワーの決定的使用のための選択肢

謝辞

略語集

著訳者紹介

原注

カスタマーレビュー

5つ星のうち5.0

星5つ中の5

5つ星のうち5.0 日本ではほとんど知られていない中国海上民兵の実態を明らかにしている貴重な本。

2020年3月27日に日本でレビュー済み

グレーゾーン作戦は、戦争状態と平時の状態の間をうまく利用して、本格的な軍事行動を敵国にとらせないために実施されるものということらしい。中国共産党は、米国海軍と正面から戦っても勝てないことを良く理解している。戦争に至らないグレーゾーンで正規海軍が手が出せないように行動し、少しづつ権益を確保して、最終的には領土をかすめ取ろうという中国共産党のやり口が理解できた。

日本の領土である尖閣列島も、常時中国海警局の艦船が領海を脅かす活動を実施している。中国海警局と言っても組織的には人民解放軍海軍と密接につながっており、ほとんど海軍といってもいい組織である。

中国共産党は、中国海警局を諸外国には沿岸警備隊と称しているが、装備的には戦闘艦と同じである。

また、その下部組織に中国海上民兵という組織があり、彼らは、通常普通の経済活動(漁業や海運)を実施していて上から指示があれば、中国海警局と連携して行動することにはあまり知られていないことだ。お笑いともいえるのは、ベトナムへの嫌がらせ行為を行う中で、漁船の場合には迷彩服を着て威圧する、しかし海軍が出てくると漁民の作業服を着て相手を騙す手法である。

敵をうまくだまして勝とうとする戦略は、まさに孫氏の兵法にのっとったものだろう。日本も学ぶべきだ。

2人のお客様がこれが役に立ったと考えています

COMPLETE INFORMATION ON VOLUME:

RELATED READING

INTERVIEWS

Prashanth Parameswaran, “Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson on China and the Maritime Gray Zone,” The Diplomat, 14 May 2019.

How China thinks about and acts in the maritime gray zone, and what that means for the region’s future.

Over the past few years, as China has continued its expansion in the maritime domain, scholars and practitioners alike have honed in on the subject of how Beijing operates in the so-called “gray zone” between war and peace, staying below the threshold of armed conflict to secure gains while not provoking military responses by others, including the United States. Understanding the dynamics of this has important implications not only for particular maritime spaces, such as the East China Sea and the South China Sea, but also for broader issues such as the management of U.S.-China competition and wider regional peace and stability.

The Diplomat’s senior editor, Prashanth Parameswaran, recently spoke to Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson, both affiliated with the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute, about how China thinks about and acts in the maritime gray zone and what that might mean for the region’s future. The discussion was framed around the release of a new edited volume by the authors in March entitled China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations.

One of the core contributions of the book is providing a detailed and systematic understanding of how China itself thinks about the maritime gray zone – both on its own terms as well as how it related to broader Chinese foreign and defense policy – with a detailed use of Chinese sources. What are some of the key takeaways about how China thinks about the maritime gray zone in particular, in terms of how it is defined as well as the objectives and key components of China’s approach? And what would you flag as some of the areas of similarity and difference with respect to how others may think of these challenges and talk about them?

China is much more transparent in Chinese. And, particularly in native-language sources, Chinese policymakers are very clear about the fact that their long-term goal is to exercise “administrative control” over all of the 3 million square kilometers of Chinese-claimed maritime space. This includes all of the Bohai Gulf, large sections of the Yellow Sea and East China Sea, and all of the area within the nine-dash line in the South China Sea. Many Western analysts assume that China has more abstract aims, like discrediting the international legal order. This may happen anyway, as a byproduct of their actions, but the most compelling evidence suggests that Beijing sees strategic, economic, and symbolic value in controlling as much space as possible within the First Island Chain.

Chinese leaders don’t use the term “gray zone” to describe their approach to asserting control over this space. For at least a decade, they have conceived of their policy as a balancing act. On the one hand, they feel the need to defend and advance China’s claims. They call these actions “maritime rights protection.” On the other hand, they want to avoid severely harming their relations with other states. Regional stability, after all, is vital for sustaining China’s economic development — which remains the core of China’s grand strategy. Using paranaval forces like the coast guard and the militia allows them to find an optimal balance between “rights protection” and “stability maintenance.” Paranaval forces are much less provocative than gray-hulled warships. The Chinese coast guard operates on the pretext of routine law enforcement, and militia often pretend to be fishermen. Yet both forces can be used to pursue traditional military objectives of controlling space. … … …

Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 11 March 2019.

- Republished as “Interview: China’s Maritime ‘Gray Zone’ Operations,” The Maritime Executive, 2019.

On March 15th, the Naval Institute Press will publish China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations, a volume edited by professors Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson from the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. CIMSEC recently reached out to Erickson and Martinson about their latest work.

Q: What was the genesis of your book?

Erickson: In the last decade or so, China has dramatically expanded its control and influence over strategically important parts of maritime East Asia. It has done so despite opposition from regional states, including the United States, and without firing a shot. Others have examined this topic, but we found that much of the public analysis and discussion was not grounded in solid mastery of the available Chinese sources—even though China tends to be much more transparent in Chinese. We also recognized a general lack of understanding about the two organizations on the front lines of Beijing’s seaward expansion: the China Coast Guard (CCG) and the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). This volume grew out of a conference we held in Newport in May 2017 to address some of these issues. It contains contributions from world-leading subject matter experts, with a wide range of commercial, technical, government, and scholarly experience and expertise. We’re honored to receive endorsements from top leaders in sea power, strategy, and policy: former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Gary Roughead, former Secretary of the Navy J. William Middendorf, Harvard Professor Stephen Rosen, former Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Fleet Commander-in-Chief Vice Admiral Yoji Koda, Dr. James Carafano of the Heritage Foundation, and former Pentagon Director of Net Assessment Andrew Marshall.

Q: The title of your book is China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations. How does the term “gray zone” apply here?

Martinson: We usually prefer to use Chinese concepts when talking about Chinese behavior, and Chinese strategist do not generally use the term “gray zone.” But we think that the concept nicely captures the essence of the Chinese approach. We were inspired by the important work done by RAND analyst Michael Mazarr, who contributed a chapter to the volume. In his view, gray zone strategies have three primary characteristics. They seek to alter the status quo. They do so gradually. And they employ “unconventional” elements of state power. Today, a large proportion of Chinese-claimed maritime space is controlled or contested by other countries. This is the status quo that Beijing seeks to alter. Its campaign to assert control over these areas has progressed over a number of years. Clearly, then, Chinese leaders are in no rush to achieve their objectives. And while China’s Navy plays a very important role in this strategy, it is not the chief protagonist.

Q: Who, then, are the chief actors?

Martinson: The CCG and the PAFMM perform the vast majority of Chinese maritime gray zone operations. Chinese strategists and spokespeople frame their actions as righteous efforts to protect China’s “maritime rights and interests.” The CCG uses law enforcement as a pretext for activities to assert Beijing’s prerogatives in disputed maritime space. PAFMM personnel are often disguised as civilian mariners, especially fishermen. Most do fish, at least some of the time. But they can be activated to conduct rights protection operations. And a new elite subcomponent is paid handsomely to engage in sovereignty promotion missions fulltime without fishing at all. Meanwhile, the PLA Navy also plays a role in disputed waters, serving what Chinese strategists call a “backstop” function. It discourages foreign countries from pushing back too forcefully and stands ready over the horizon to come to the aid of China’s gray zone forces should the situation escalate.

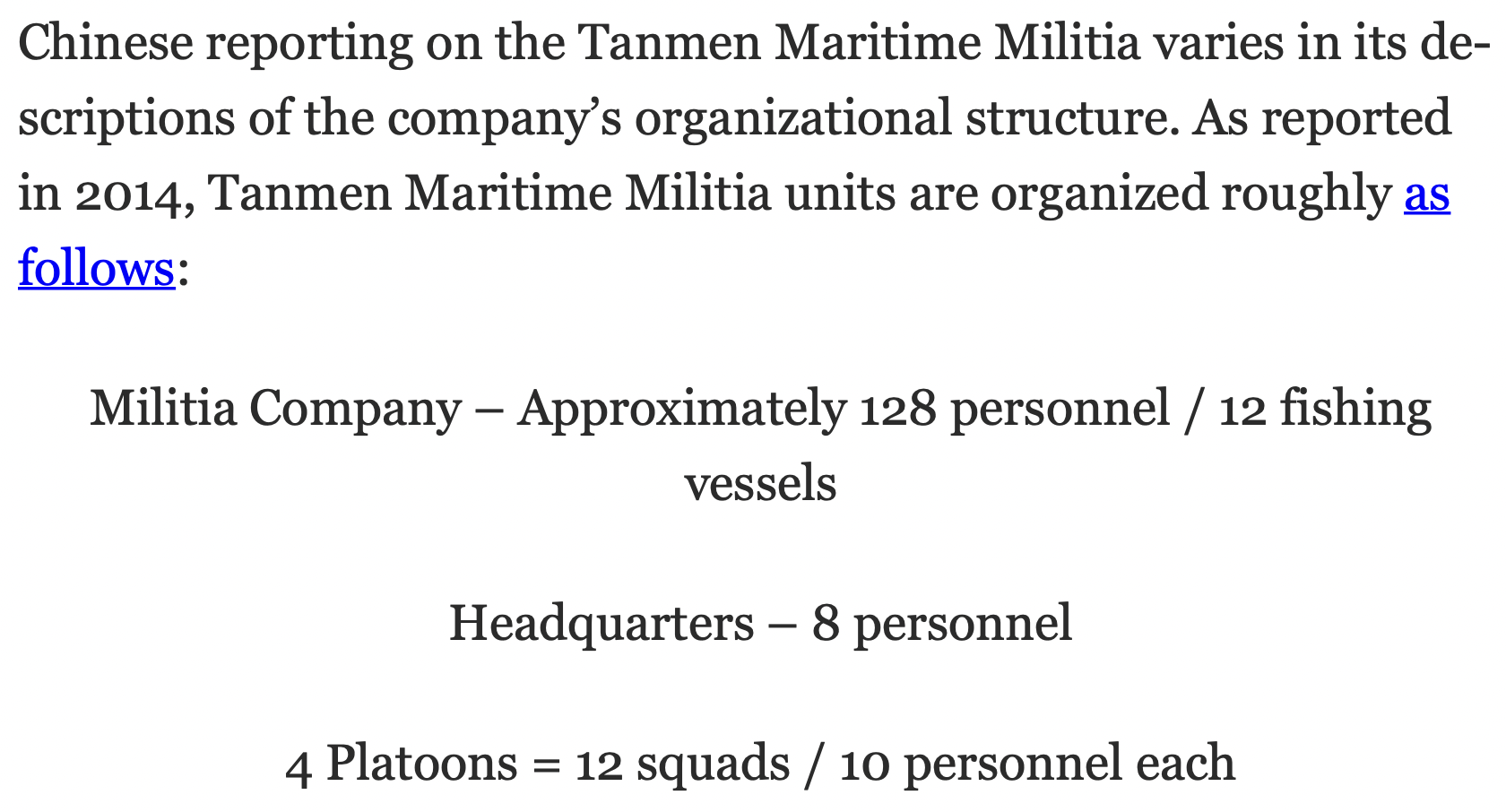

Q: Most readers will have heard about the China Coast Guard, but fewer may be familiar with the PAFMM. How is the PAFMM organized?

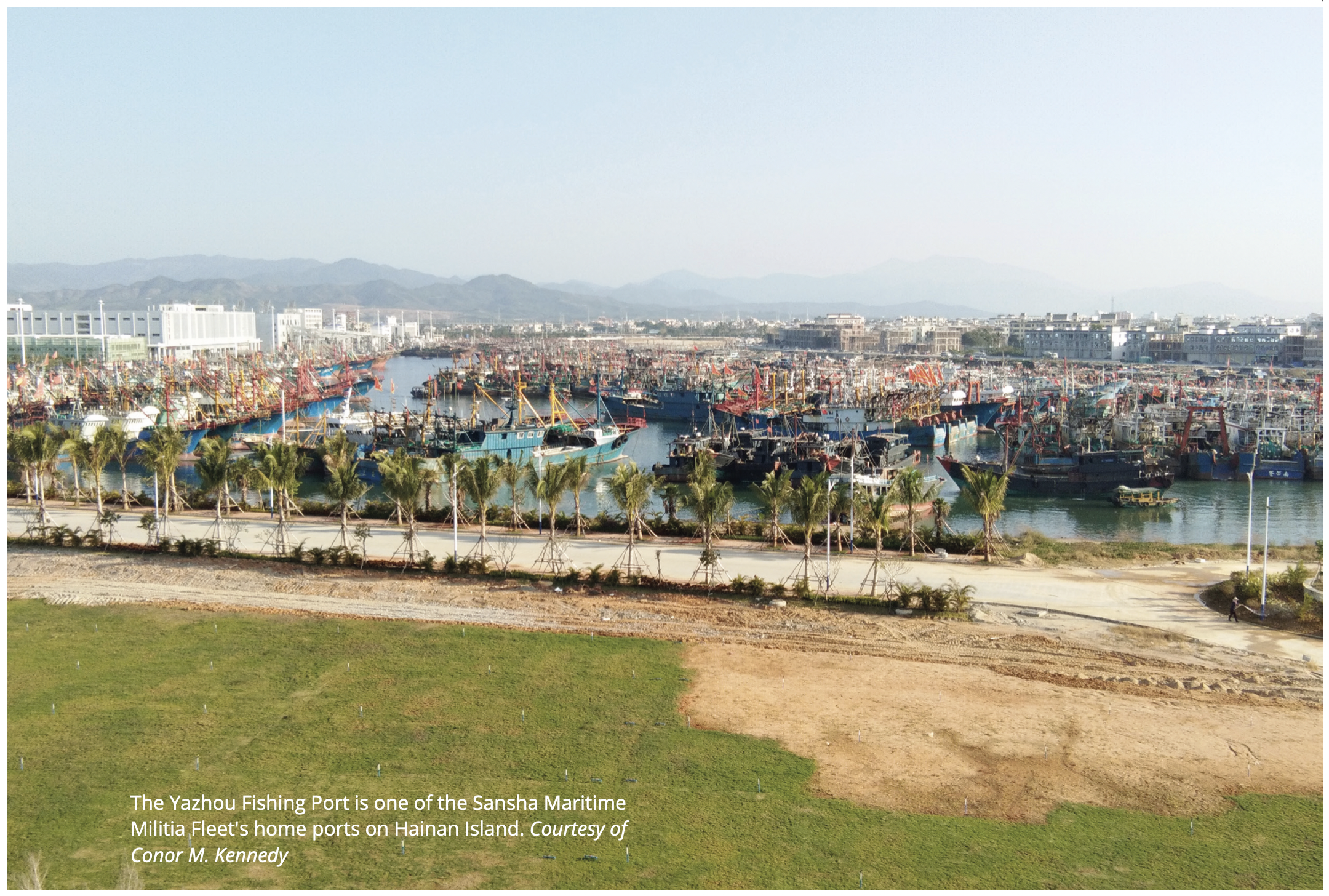

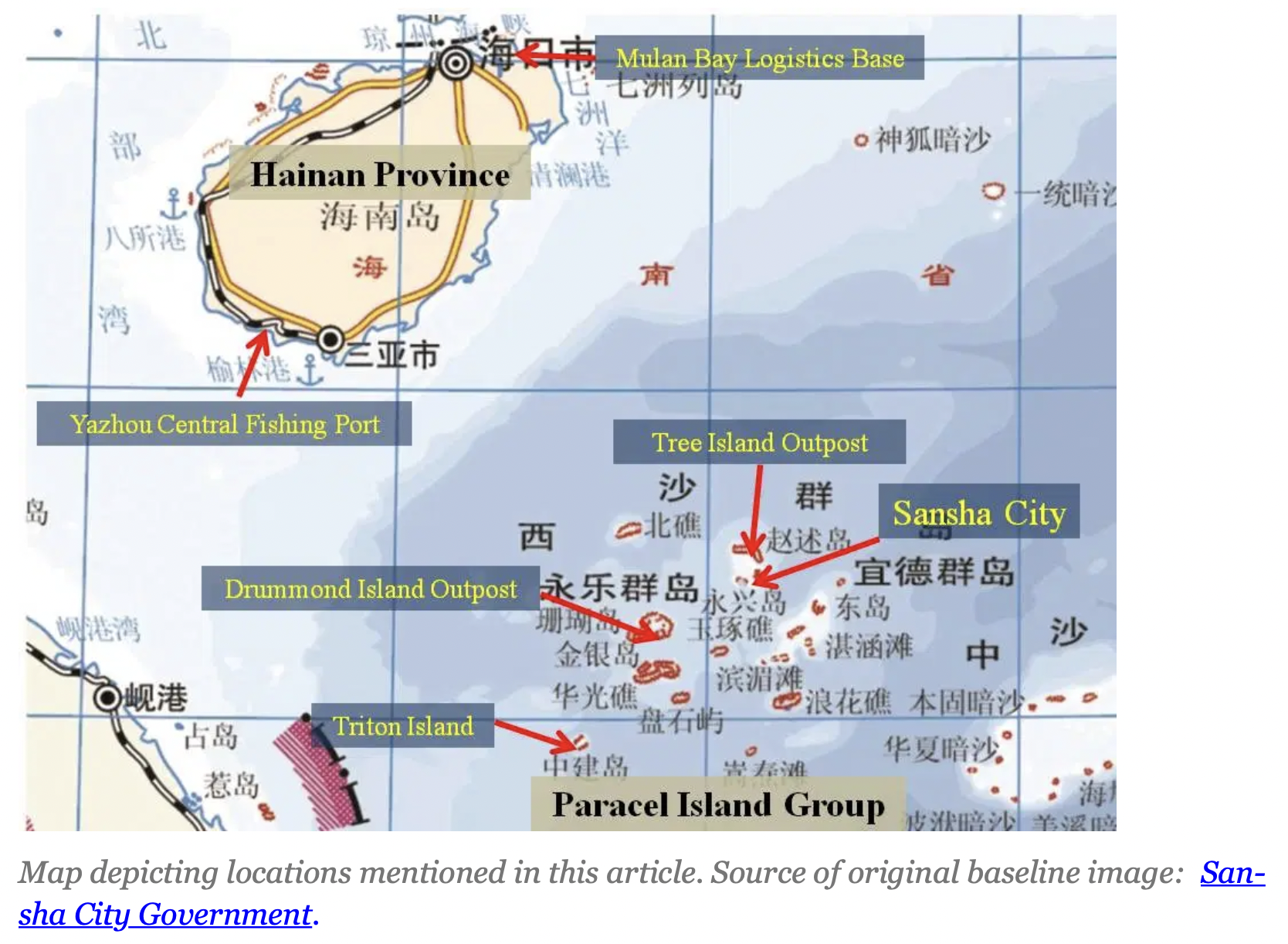

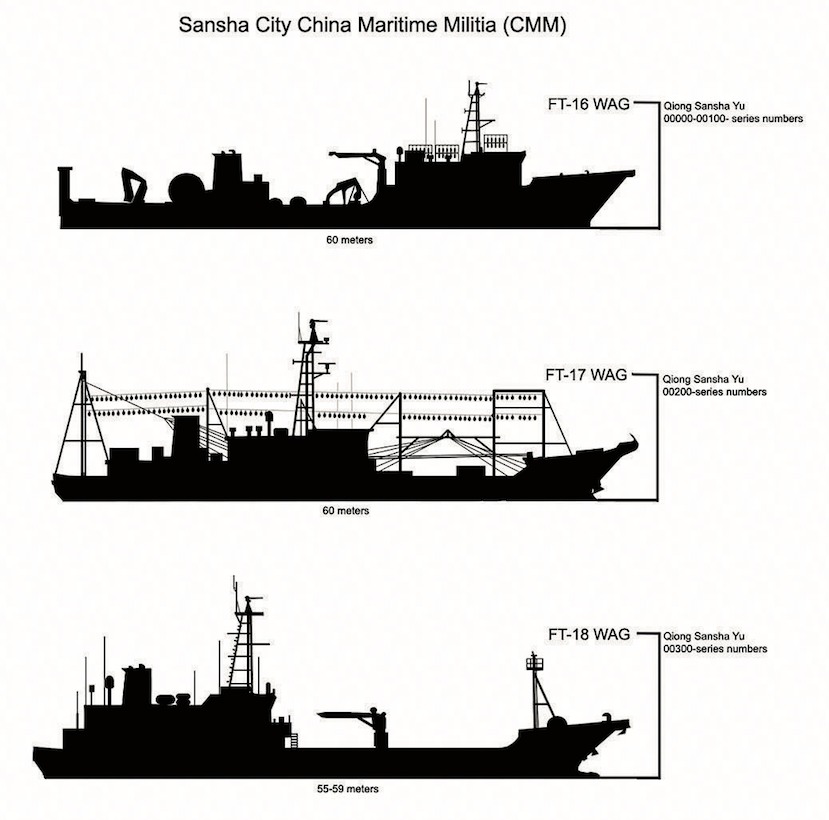

Erickson: The PAFMM is a state-organized, developed, and controlled force operating under a direct military chain of command.This component of China’s armed forces is locally supported, but answers to China’s centralized military bureaucracy, headed by Commander-in-Chief Xi Jinping himself. While most retain day jobs, militiamen are organized into military units and receive military training, sometimes from China’s Navy. In recent years, there has been a push to professionalize the PAFMM. The Sansha City Maritime Militia, headquartered on Woody Island in the Paracels, is the model for a professional militia force. It is outfitted with seven dozen large new ships that resemble fishing trawlers but are actually purpose-built for gray zone operations. Lacking fishing responsibilities, personnel train for manifold peacetime and wartime contingencies, including with light arms, and deploy regularly to disputed South China Sea areas, even during fishing moratoriums.

Three types of maritime militia vessels depicted in the Office of Naval Intelligence’s China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), Coast Guard, and Government Maritime Forces 2018 Recognition and Identification Guide. (Office of Naval Intelligence)

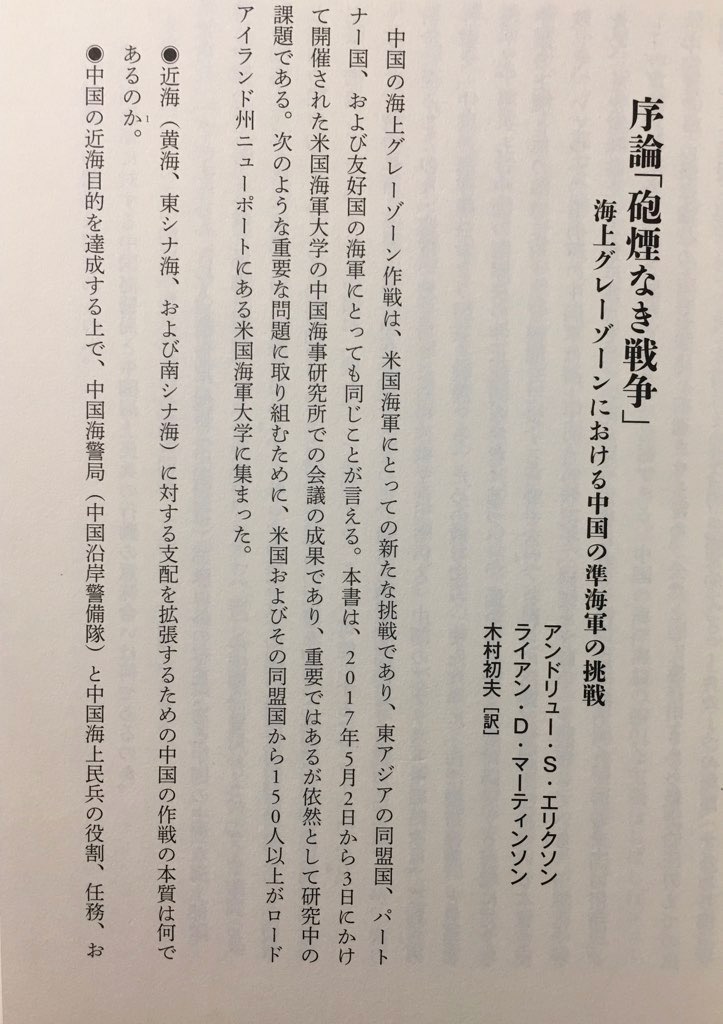

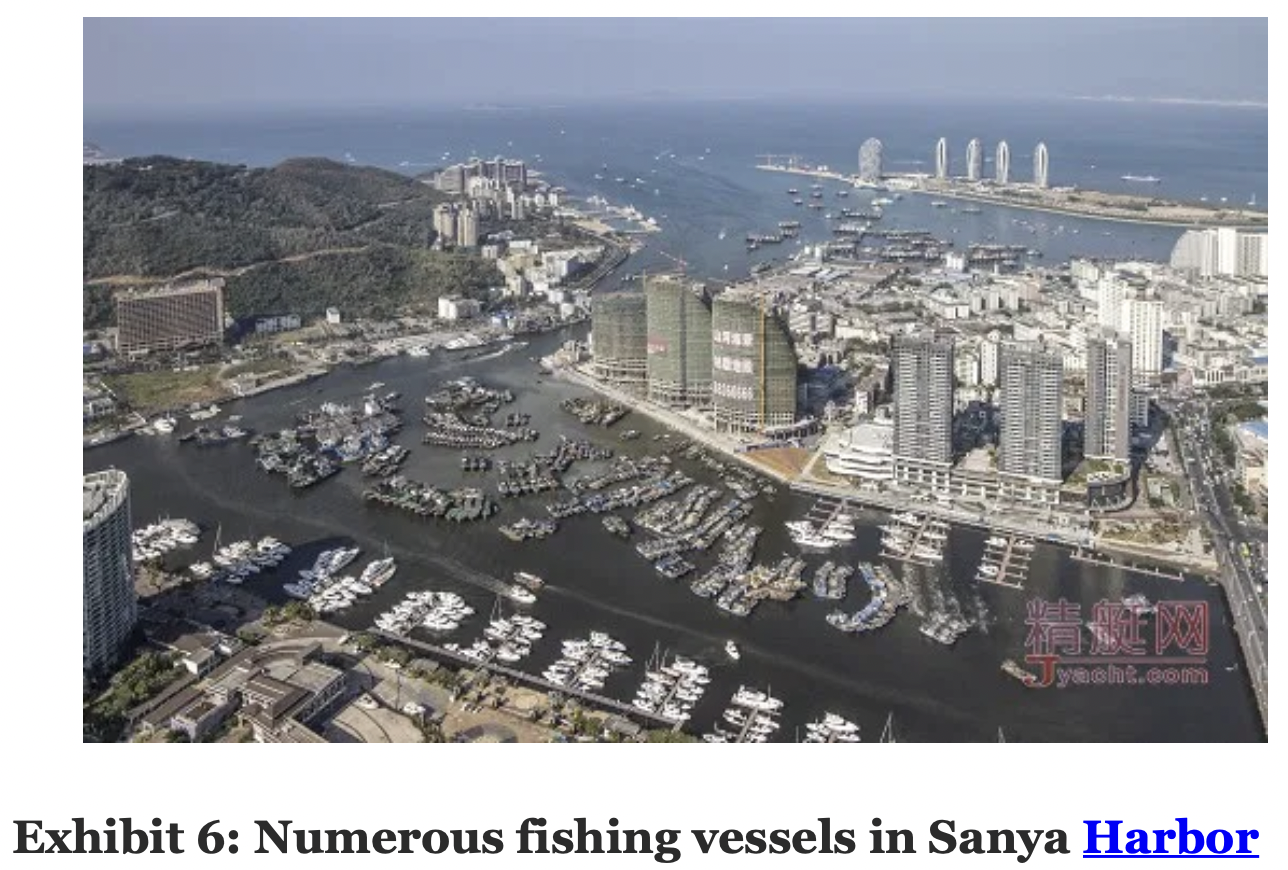

There are no solid numbers publicly available on the size of China’s maritime militia, but it is clearly the world’s largest. In fact, it is virtually the only one charged with involvement in sovereignty disputes: only Vietnam, one of the very last countries politically and bureaucratically similar to China, is known to have a similar force with a similar mission. China’s maritime militia draws on the world’s largest fishing fleet, incorporating through formal registration a portion of its thousands of fishing vessels, and the thousands of people who work aboard them as well as in other marine industries. The PAFMM thus recruits from the world’s largest fishing industry. According to China’s 2016 Fisheries Yearbook, China’s fishing industry employs 20,169,600 workers, mostly in traditional fishing practices, industry processing, and coastal aquaculture. Those who actually fish “on the water” number 1,753,618. They operate 187,200 “marine fishing vessels.” An unknown portion of these are militia boats. To give a sense of the size and distribution of PAFMM forces, our volume includes figures showing the location of leading militia units in two major maritime provinces: Hainan and Zhejiang.

Q: How is the CCG organized for gray zone operations?

Martinson: When we held the conference in 2017, the CCG was in the midst of a major organizational reform. It was only set up in 2013, the result of a decision to combine four different maritime law enforcement agencies. Before 2013, most rights protection operations were conducted by two civilian agencies: China Marine Surveillance and Fisheries Law Enforcement. They did not cooperate well with each other. Moreover, neither had any real policing powers. After the CCG was created, it became clear that Beijing intended to transform it into a military organization. In early 2018, Beijing announced a decision to transfer the CCG from the State Oceanic Administration to the People’s Armed Police. At about the same time, the People’s Armed Police was placed under the control of the Central Military Commission. So, like the PAFMM, it is now a component of China’s armed forces. Moreover, CCG officers now have the authority to detain and charge foreign mariners for criminal offenses simply for being present in disputed areas of the East China Sea and South China Sea (although they have yet to use this authority in practice).

Q: How is the CCG equipped to assert China’s maritime claims?

Martinson: When Beijing’s gray zone campaign began in earnest in 2006, China’s maritime law enforcement forces were fairly weak. They owned few oceangoing cutters, and many of those that they did own were elderly vessels handed down from the PLA Navy or the country’s oceanographic research fleet. They were not purpose-built for “rights protection” missions. In recent years, however, Beijing has invested heavily in new platforms for the CCG. Today, China has by far the world’s largest coast guard, operating more maritime law enforcement vessels than the coast guards of all its regional neighbors combined. As the chapter by Joshua Hickey, Andrew Erickson, and Henry Holst points out, the CCG owns more than 220 ships over 500 tons, far surpassing Japan (with around 80 coast guard hulls over 500 tons), the United States (with around 50), and South Korea (with around 45). At over 10,000 tons full load, the CCG’s two Zhaotou-class patrol ships are the world’s largest coast guard vessels. The authors project that in 2020 China’s coast guard could have 260 ships capable of operating offshore (i.e., larger than 500 tons). Drawing from lessons learned while operating in disputed areas in the East and South China Seas, recent classes of Chinese coast guard vessels have seen major qualitative improvements. They are larger, faster, more maneuverable, and have enhanced firepower. Many CCG vessels are now armed with 30 mm and 76 mm cannons.

Q: It appears that these gray zone forces and operations are heavily focused on sovereignty disputes such as in the East and South China Seas. Are they also pursuing other goals and lines of effort?

Erickson: That is correct. The vast majority of maritime gray zone activities involve efforts to assert Chinese control and influence over disputed maritime space in what Chinese strategists term the “Near Seas.” When conducting rights protection operations, these forces help Beijing enforce its policies regarding which kinds of activities can and cannot take place in Chinese-claimed areas. The CCG and PAFMM intimidate and harass foreign civilians attempting to use the ocean for economic purposes, such as fishing and oil/gas development. Since at least 2011, for instance, China’s coast guard and militia forces have been charged with preventing Vietnam from developing offshore hydrocarbon reserves in its own Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), part of which overlaps with China’s sweeping nine-dash line claim. China’s gray zone forces also protect Chinese civilians operating “legally” in Chinese-claimed maritime space. The 2014 defense of Chinese drilling rig HYSY-981, discussed in detail in our volume, is a classic case of this type of gray zone operation. By controlling maritime space, China’s gray zone forces can also determine who can and cannot access disputed features. Since 2012, for instance, Chinese coast guard and militia forces have upheld Chinese control over Scarborough Reef. Today, Filipino fishermen can only operate there with China’s permission.

Q: What are some of the tactics employed by China’s gray zone forces?

Erickson: Most CCG cutters are unarmed, and PAFMM vessels are minimally armed at most. They assert Chinese prerogatives through employment of a range of nonlethal tactics. In many cases, Chinese gray zone ships are themselves the weapon: they bump, ram, and physically obstruct the moments of other vessels. They also employ powerful water cannons to damage sensitive equipment aboard foreign ships and flood their power plants. Foreign states are often helpless to respond because China has the region’s most powerful navy, which gives it escalation dominance.

Q: How have regional states reacted to Chinese maritime gray zone operations? Have some had more effective responses than others?

Martinson: Regional states have not presented China with a united front. They have each handled Chinese encroachments differently. China’s strongest neighboring sea power, Japan has taken the most vigorous actions. As Adam Liff outlines in his chapter, it has bolstered its naval and coast guard forces along its southern islands. It has also taken bold steps to publicize China’s gray zone actions. Vietnam has been a model of pushback against Beijing’s maritime expansion, as Bernard Moreland recounts in his chapter. But even its resistance has limits. In July 2017, Beijing likely used gray zone forces to compel Hanoi to cancel plans to develop oil and gas in its own EEZ, in cooperation with a Spanish company. Other states have taken a much more conciliatory approach to China’s incursions in the South China Sea. The Philippines, for example, is apparently acquiescing to Beijing’s desire to jointly develop disputed parts of the South China Sea—areas that a 2016 arbitration ruling clearly place under Philippine jurisdiction. Meanwhile, China continues to push Manila in other ways. Philippine supply shipments to Second Thomas Shoal are still subject to harassment. China has recently concentrated a fleet of gray zone forces just off the coast of Philippine-occupied Thitu Island, in an apparent effort to pressure Manila to discontinue long-planned repairs and updates to its facilities there.

Chinese fishing vessels massed off Philippine-occupied Thitu Island in January 2019. (CSIS/AMTI, DigitalGlobe)