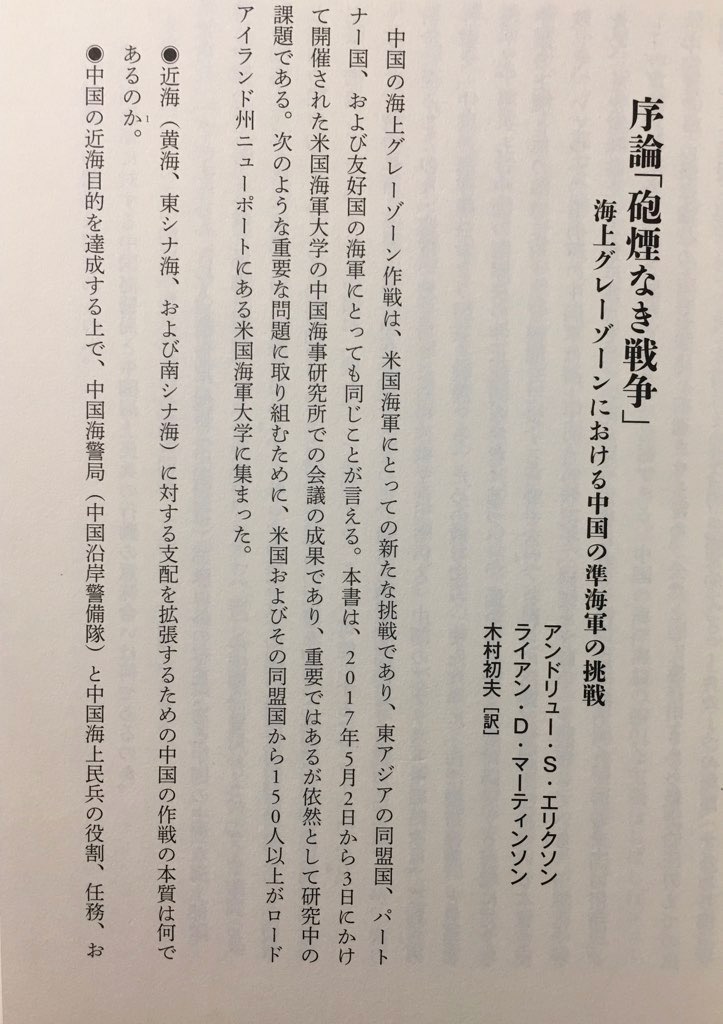

The China Maritime Militia Bookshelf: YouTube Presentation, SECNAV Guidance, Music Video—& More!

Andrew S. Erickson, “Tracking China’s ‘Little Blue Men’—A Comprehensive Maritime Militia Compendium,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 25 May 2022.

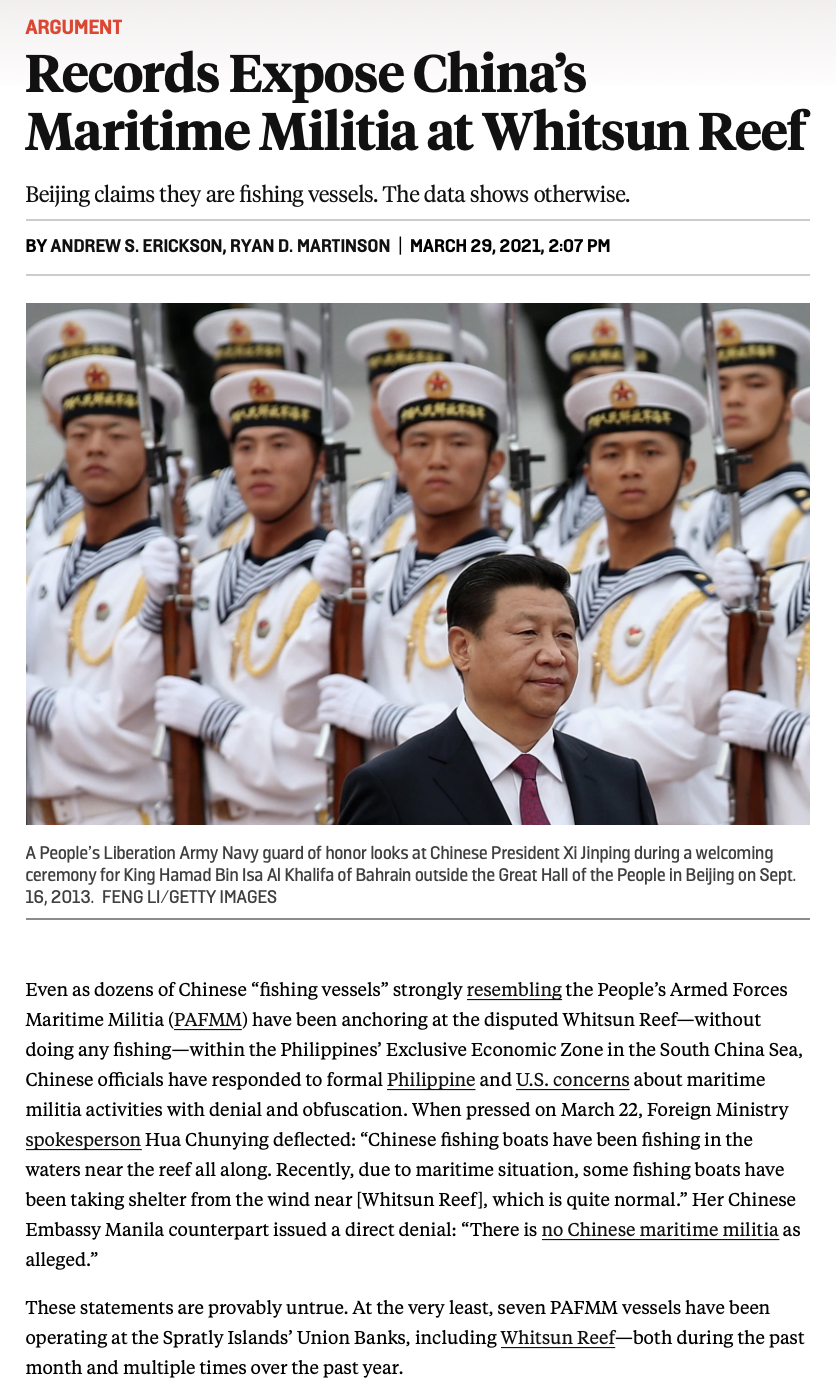

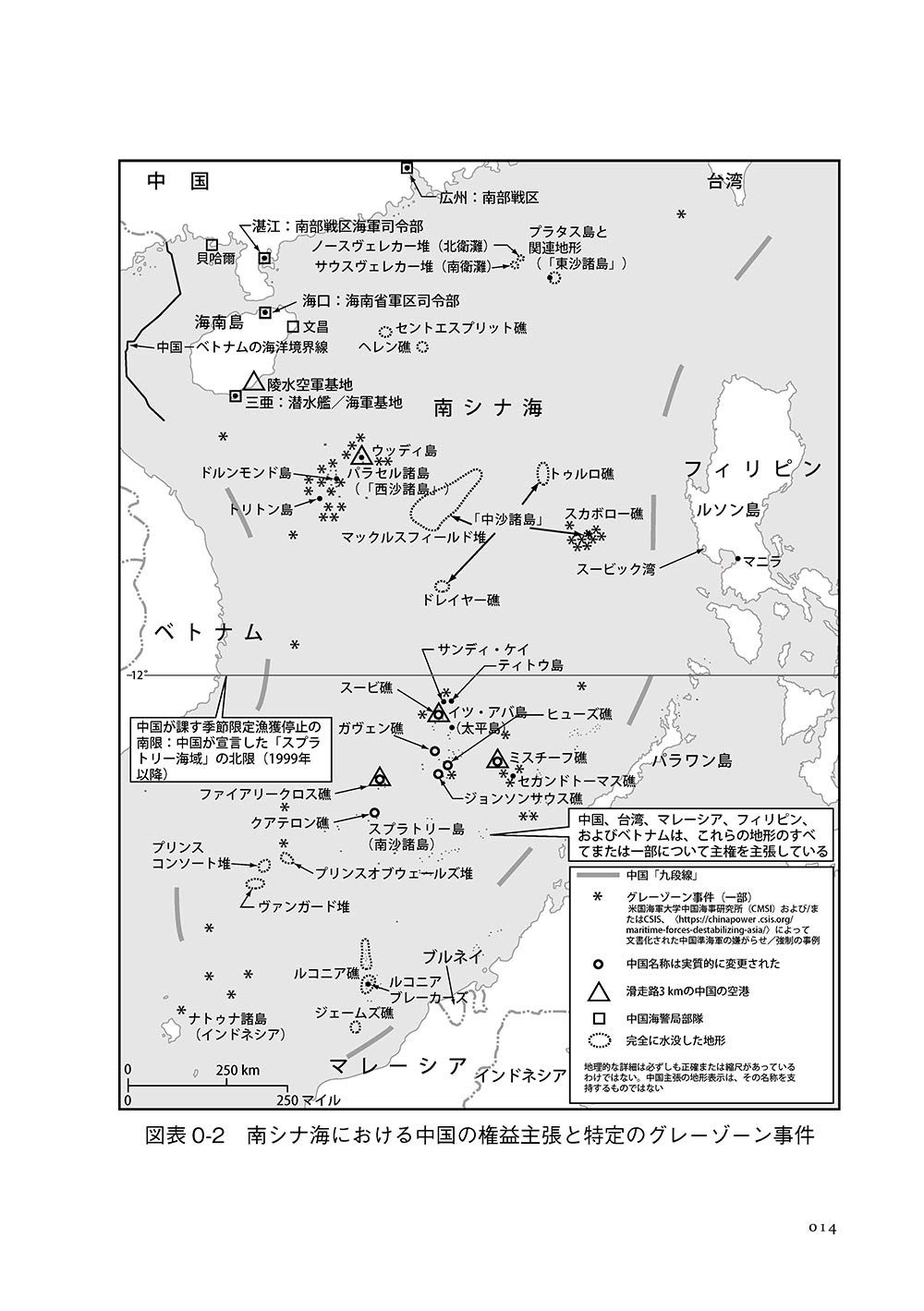

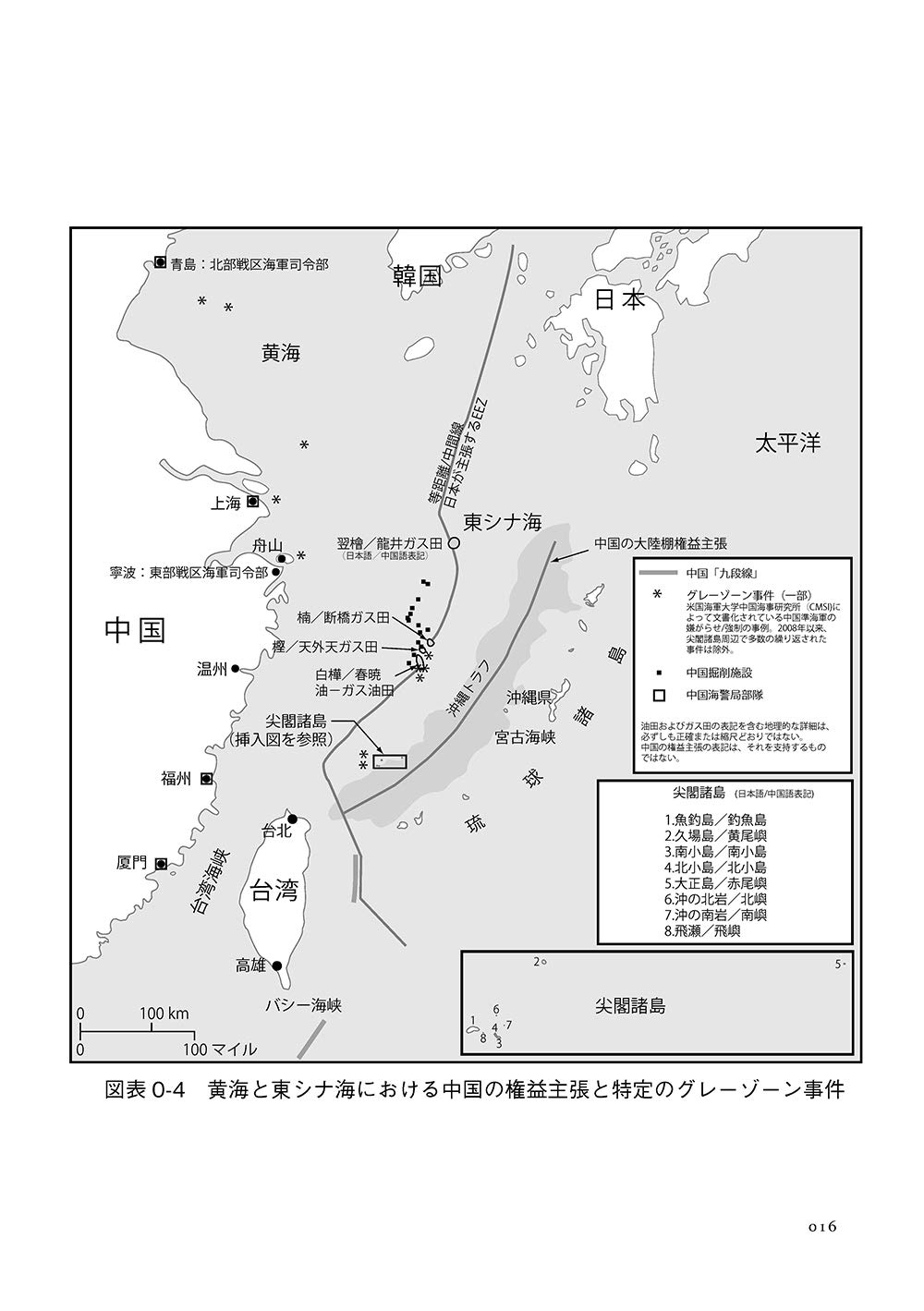

Amid wave after wave of Coronavirus variants, fishy things have been happening across the South and East China Seas, home to virtually all of China’s unresolved maritime disputes. Since Beijing remains far from being fully forthcoming and transparent, I hope that governments whose nations’ ships have been involved with these bilateral incidents with PRC vessels—as well as any other knowledgeable parties—will release complete information on exactly what has happened. Meanwhile, however, ample information is already available concerning China’s People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) and the important role it has played in these waters for decades. And it’s all here, in keyword-searchable format!

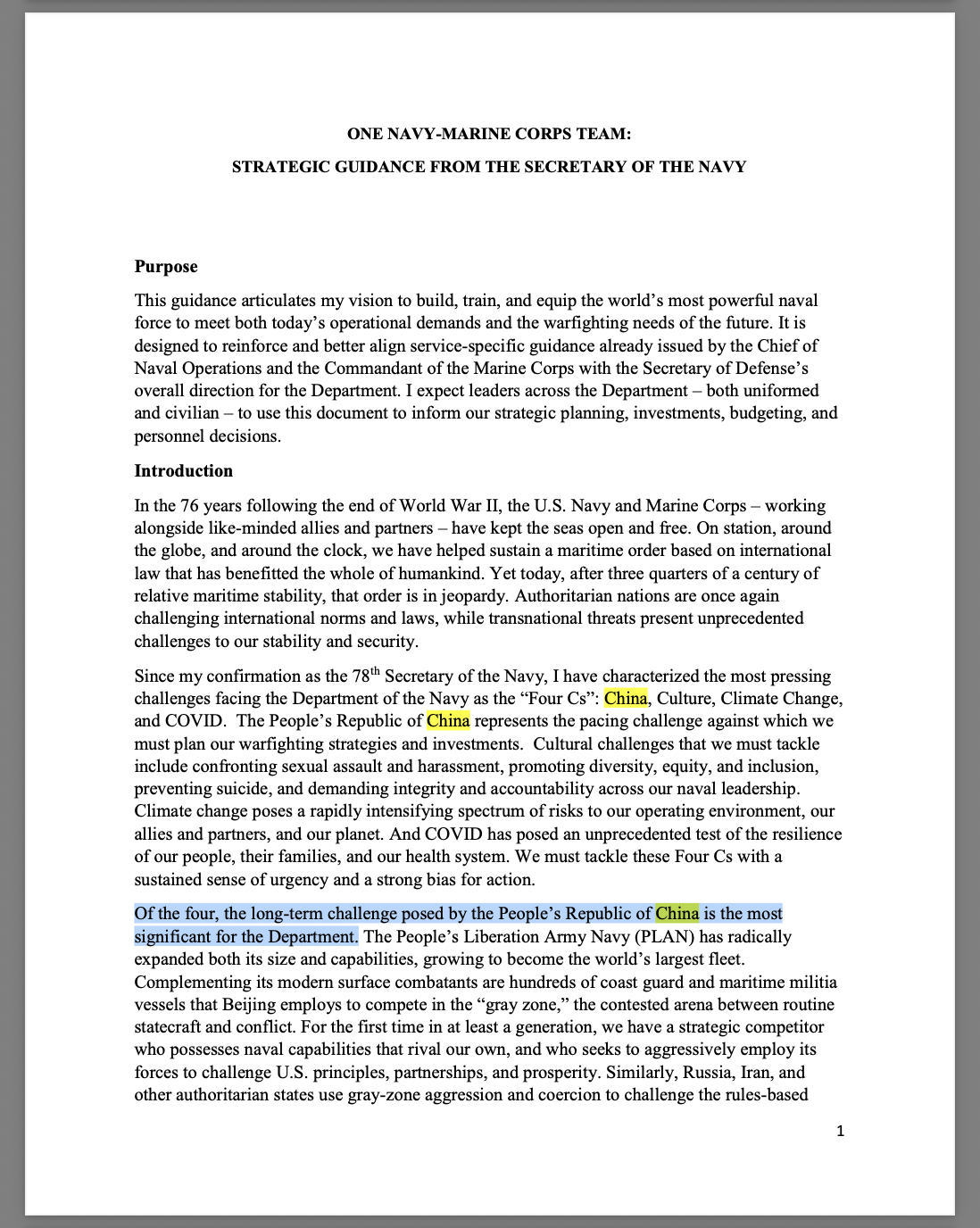

This Bookshelf compilation is updated with the latest guidance from SECNAV Carlos Del Toro, entry in Wikipedia & music video from the PAFMM’s very own Sansha Garrison! It includes everything from the very newest sources… to some of my earliest findings with colleagues at the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI), dating back to 2009—when we uncovered PRC Militia forces’ role in mine warfare (MIW). For an overview, you might watch my best single PAFMM presentation, now available on YouTube.

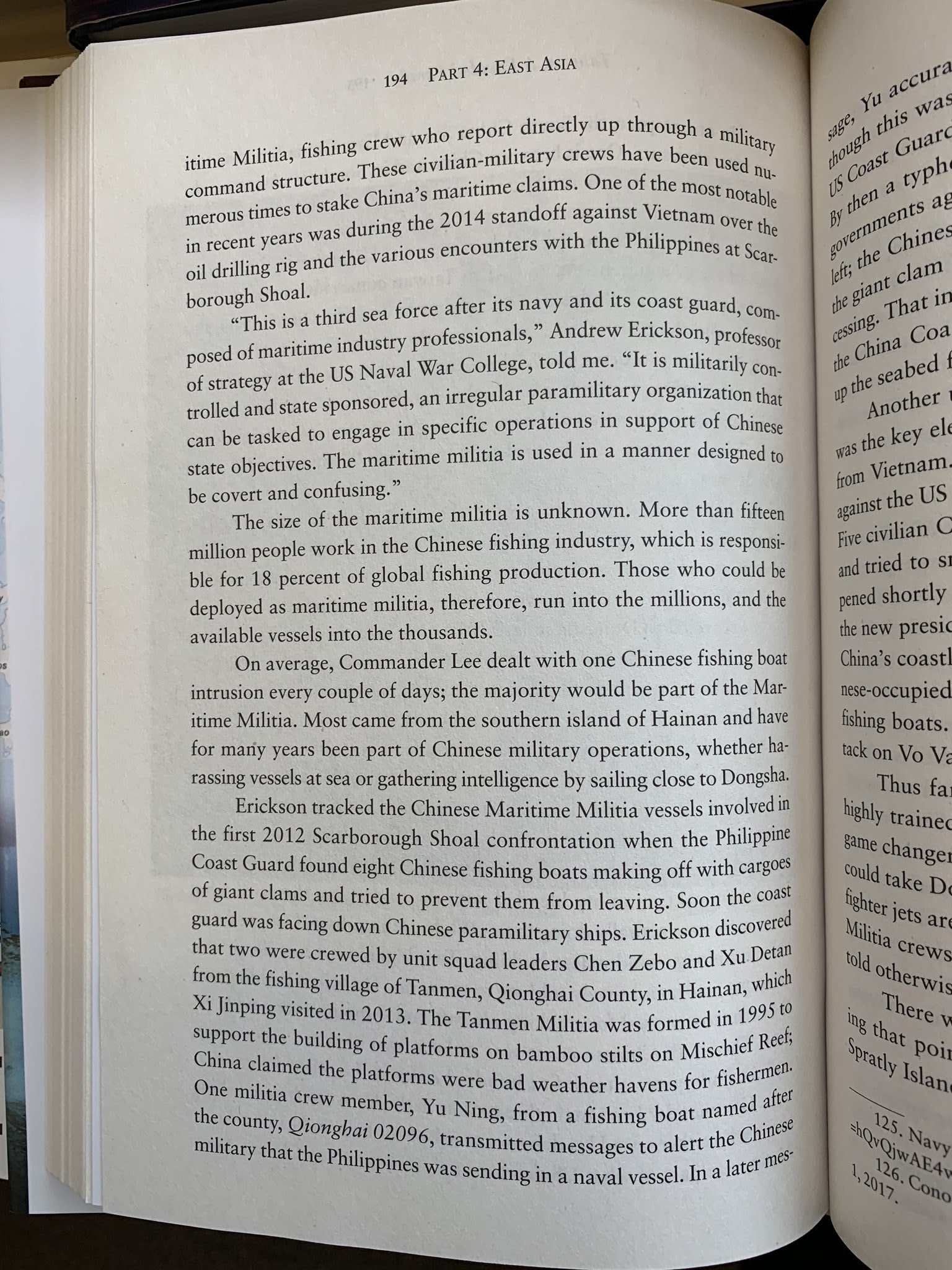

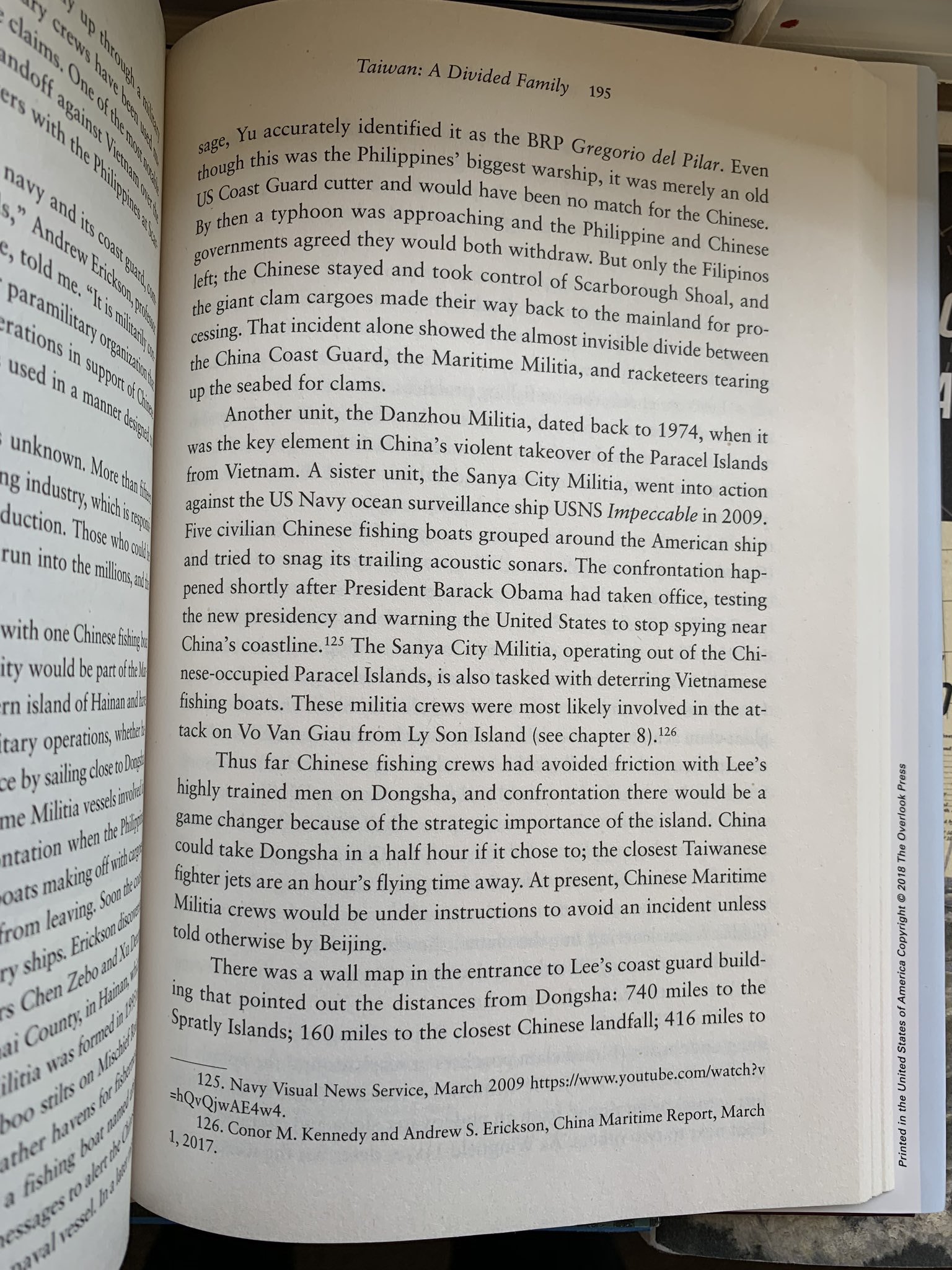

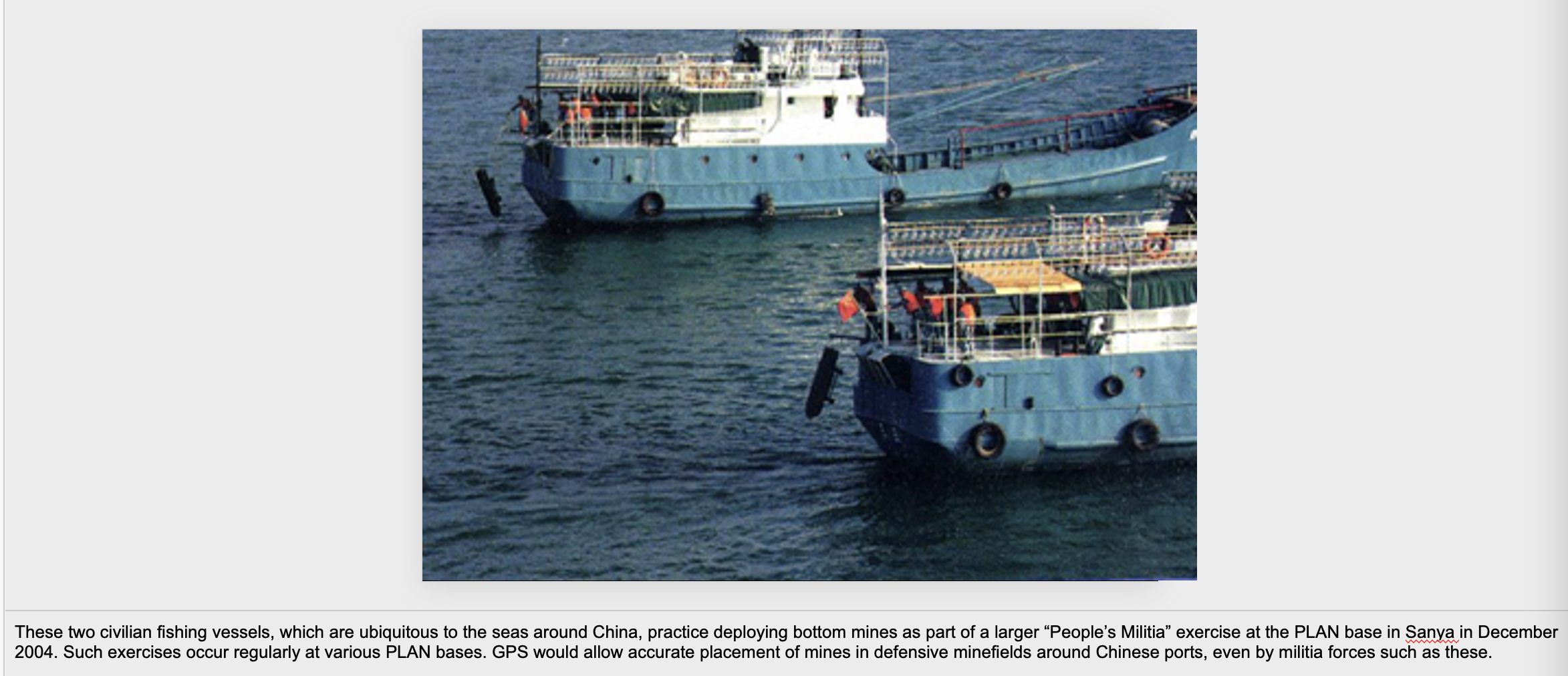

As I told the Defense Forum Foundation in 2009, “China holds exercises that involve the Maritime Militia—with civilian fishing vessels—training in the laying of mines; GPS could leverage that considerably.” Here I drew on extensive research with my CMSI colleagues, published in China Maritime Study #3 (June 2009). We included multiple sections on PRC operational concepts and training to employ Maritime Militia forces and fishing vessels in MIW. Having long noticed references to China’s Maritime Militia dating back to at least the early 2000s in the PLA Navy (PLAN)’s official newspaper, People’s Navy (人民海军), I read and cited key articles.

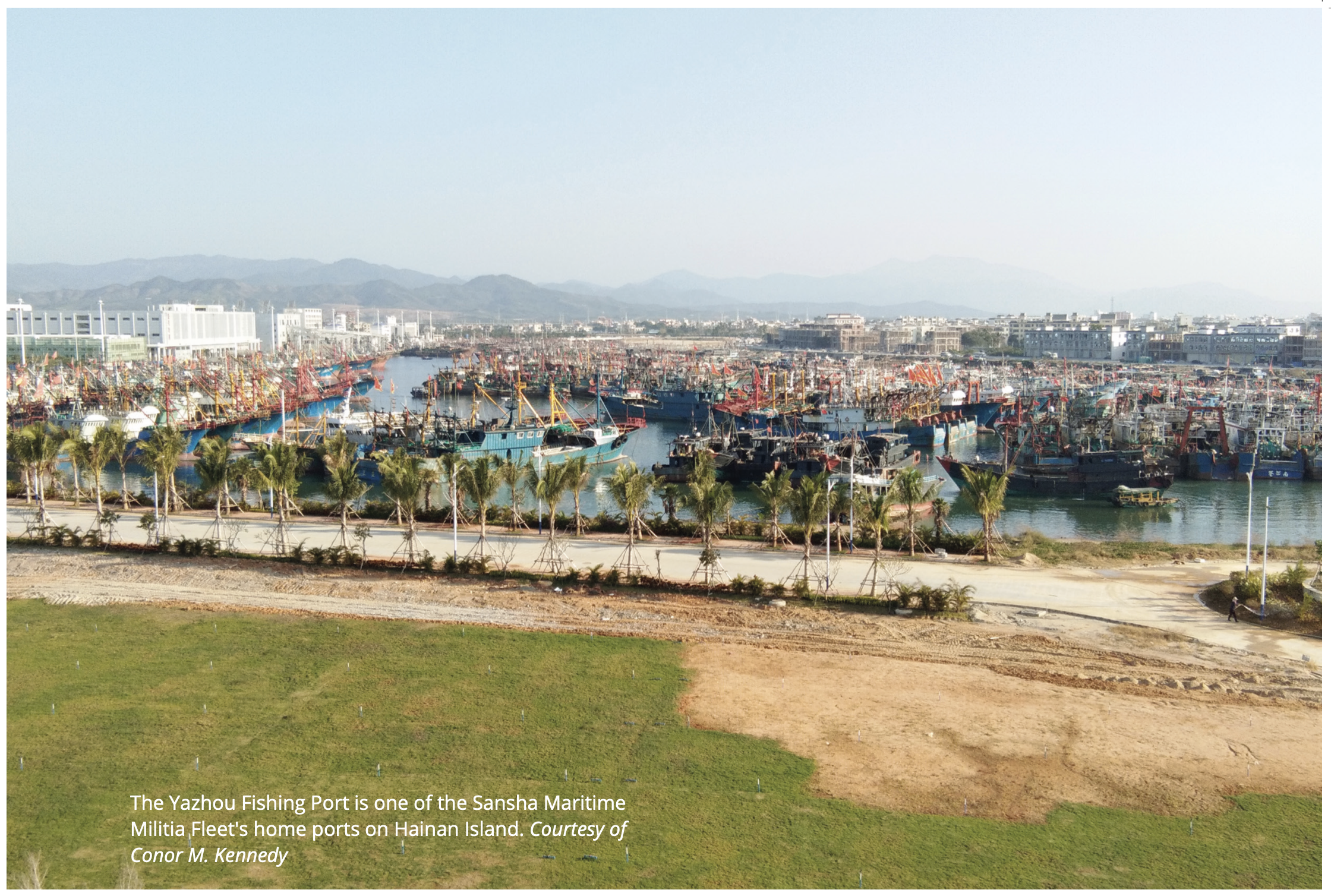

American & Allied knowledge of the PRC’s Third Sea Force has come a long way since my outstanding colleague Conor Kennedy & I began our focused research following his arrival in Newport in 2014—now top U.S. officials, including the Secretary of the Navy & the Vice President, have highlighted China’s Maritime Militia in their official statements… You can read their words, other data & analysis, and findings from specialists here!

Rarely is a topic so little recognized and so little understood (even now), yet so important and so amenable to research using Chinese-language open sources. To increase awareness and understanding of this important subject, I am maintaining this convenient compendium of major publications and other documents available on the matter thus far. If you know of others, please kindly bring them to my attention via <http://www.andrewerickson.com/contact/>.

CHINA’S MARITIME MILITIA: DATA & ANALYSIS

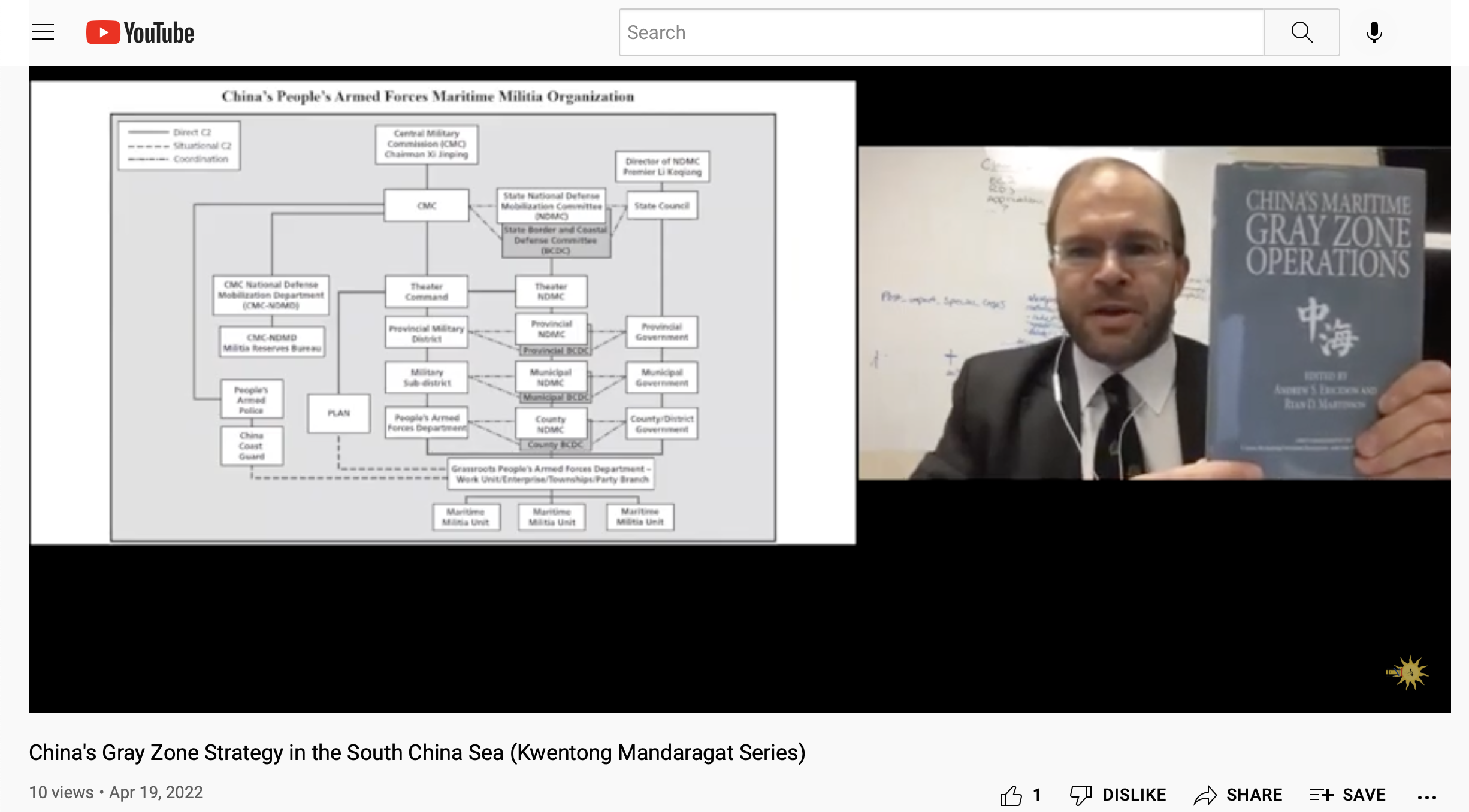

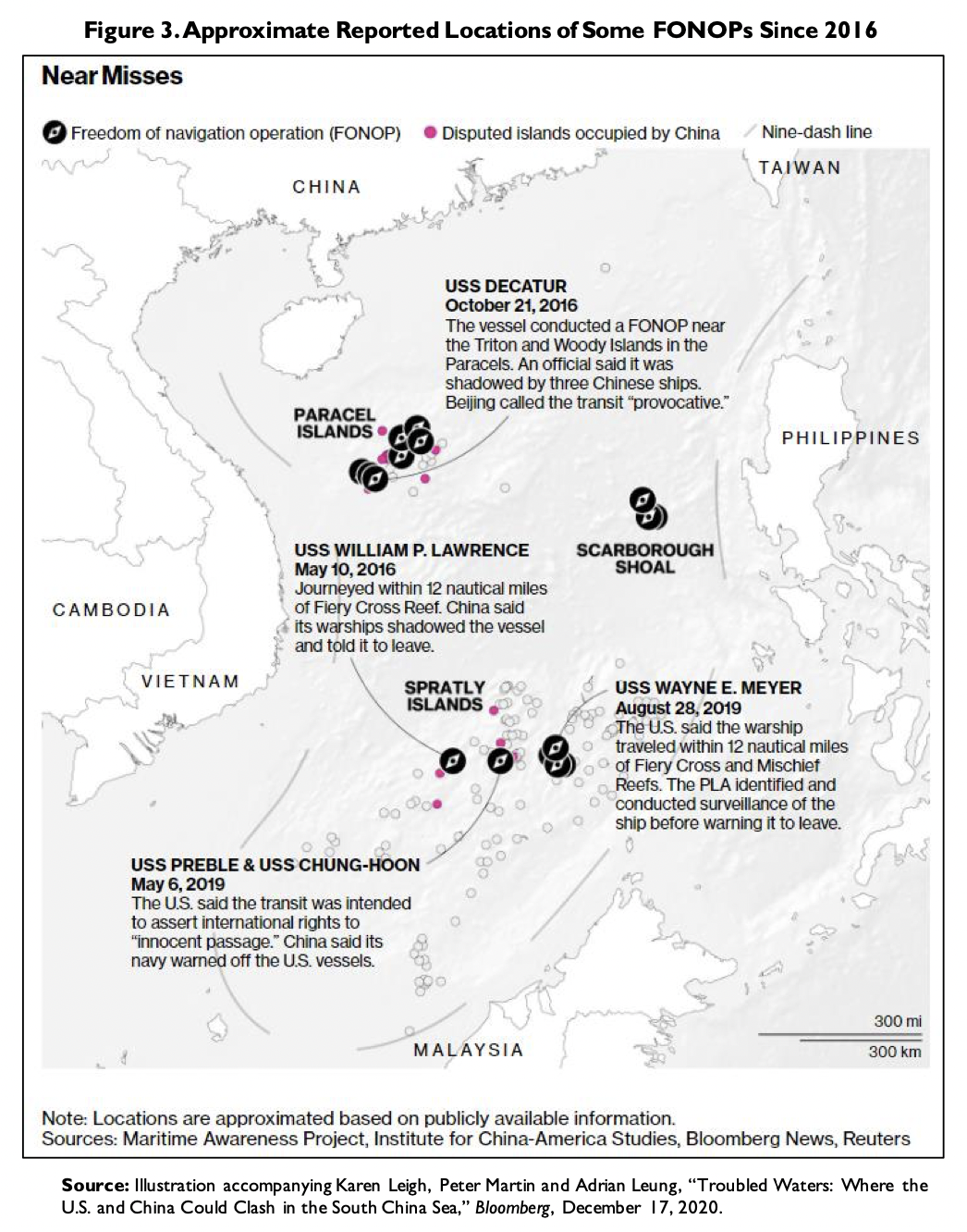

Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Gray Zone Strategy in the South China Sea: Emerging Trends and Deterrence Strategies,” Kwentong Mandaragat Lecture, Foundation for the National Interest and University of the Philippines Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea, via Zoom to Manila, 25 May 2021.

CLICK HERE TO WATCH THE PRESENTATION ON YOUTUBE.

On 25 May 2021, the Foundation for the National Interest, together with the UP Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea, with the support of the U.S. Embassy in Manila, sat down with Dr. Andrew Erickson of the U.S. Naval War College. The 8th Kwentong Mandaragat Series webinar discussed China’s gray zone strategy in the South China Sea in light of recent developments in the region. The webinar explored the finer details that reinforces China’s continuing gray zone operations such as the Chinese Maritime Militia, the militarization of civilian industries, and the patterns and strategies employed by said maritime militias. For more information on Dr. Andrew Erickson’s latest compilation of information regarding China’s maritime militia “Tracking China’s ‘Little Blue Men’ – A Comprehensive Maritime Militia Compendium,” visit his website by clicking here.

DISCLAIMERS:

1) The views expressed here by Dr. Andrew S. Erickson are his alone, in solely an individual academic capacity, and do not represent the official policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

2) The webinar is by-invitation only and the Open Forum is strictly off-the-record. The video has been modified to accommodate a public release of information contained herein.

***

Lonnie D. Henley, Civilian Shipping and Maritime Militia: The Logistics Backbone of a Taiwan Invasion, China Maritime Report 21 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, May 2022).

About the Author

Lonnie Henley retired from federal service in 2019 after more than 40 years as an intelligence officer and East Asia expert. He served 22 years as a U.S. Army China foreign area officer and military intelligence officer in Korea, at Defense Intelligence Agency, on Army Staff, and in the History Department at West Point. He retired as a Lieutenant Colonel in 2000 and joined the senior civil service, first as Defense Intelligence Officer for East Asia and later as Senior Intelligence Expert for Strategic Warning at DIA. He worked two years as a senior analyst with CENTRA Technology, Inc. before returning to government service as Deputy National Intelligence Officer for East Asia. He rejoined DIA in 2008, serving for six years as the agency’s senior China analyst, then National Intelligence Collection Officer for East Asia, and culminating with a second term as DIO for East Asia. Mr. Henley holds a bachelor’s degree in engineering and Chinese from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and master’s degrees in Chinese language from Oxford University, which he attended as a Rhodes Scholar; in Chinese history from Columbia University; and in strategic intelligence from the Defense Intelligence College (now National Intelligence University). His wife Sara Hanks is a corporate attorney and CEO specializing in early-stage capital formation. They live in Alexandria, Virginia.

This article was cleared for open publication by the Department of Defense (DoD) Office of Prepublication and Security Review, DOPSR Case 21-S-1603. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of defense or the U.S. Government. The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the DoD of the linked websites or the information, products, or services contained therein. The DoD does not exercise any editorial, security, or other control over the information you may find at these locations.

Summary

Most analysts looking at the Chinese military threat to Taiwan conclude that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is incapable of invading the island because it lacks the landing ships to transport adequate quantities of troops and equipment across the Taiwan Strait. This report challenges that conventional wisdom, arguing that the PLA intends to meet these requirements by requisitioning civilian vessels operated by members of China’s maritime militia (海上民兵). Since the early 2000s, the Chinese government and military have taken steps to strengthen the national defense mobilization system to ensure the military has ample quantities of trained militia forces to support a cross-strait invasion. Despite ongoing challenges—including poor data management, inconsistent training quality, and gaps in the regulatory system—and uncertainties associated with foreign-flagged Chinese ships, this concept of operations could prove good enough to enable a large-scale amphibious assault.

Introduction

Discussion of a potential Chinese military invasion of Taiwan almost always hinges on whether the PLA has enough lift capacity to deliver the would-be invasion forces across the Taiwan Strait and, to a lesser extent, whether it could sustain them once they are ashore on Taiwan. The argument centers on People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) amphibious landing ships and other over-the-shore amphibious assault assets, with most observers concluding that the PLAN has not built enough of these ships and therefore that the PLA cannot (yet?) carry out a full-scale invasion.

This report argues that the PLA plans to rely heavily on mobilized maritime militia forces operating requisitioned civilian shipping as the logistical backbone of a cross-strait landing operation, including both the delivery of PLA forces onto Taiwan and logistical sustainment for the PLAN fleet at sea and ground forces ashore. Moreover, the PLA does not regard civilian shipping as a stopgap measure until more PLAN amphibious shipping can be built, but as a central feature of its preferred approach.

The report will examine China’s extensive system for preparing and generating this support force, the roles it will undertake in an invasion operation, and the challenges that must be overcome if the plan is to succeed.

The Scope of the Problem

Most authors looking at the Chinese military threat to Taiwan conclude that the PLA cannot land enough forces on Taiwan to make an invasion viable, that it wil not reach that capability until it builds many more amphibious landing ships, and that doing so will take at least several years even if they accelerate their efforts.2 There has been little detailed analysis to underpin that judgment, at least not in open sources, but most observers assess that the PLA would need to land 300,000 or more troops on Taiwan in total and that the PLAN amphibious fleet can only land around one division, roughly 20,000 troops, in a single lift.3 Since these constraints seem obvious, the logical conclusion is that the PLA must judge itself not yet capable of invading Taiwan.4

The PLA’s prospects appear even worse when one considers the rest of the logistical and operational requirements for a major landing operation, beyond the formidable challenge of getting enough troops ashore quickly in the face of determined resistance. The PLAN auxiliary fleet is inadequate to sustain large-scale combat operations, even if those operations were close to China’s shores as a Taiwan conflict would be. The PLAN has enlisted hundreds of civilian vessels to perform tasks ranging from over-the-shore logistics to at-sea replenishment, emergency repair and towing, medical support, casualty evacuation, and combat search and rescue, suggesting that its own inventory of support ships falls far short of what it deems necessary for a landing campaign.5 Skeptics will argue that this is more proof that the PLA itself does not take the invasion option seriously. The contrary view presented here is that the PLA does take these requirements seriously, but that it intends to rely on maritime militia support for large-scale combat operations, and specifically for a Taiwan invasion campaign.

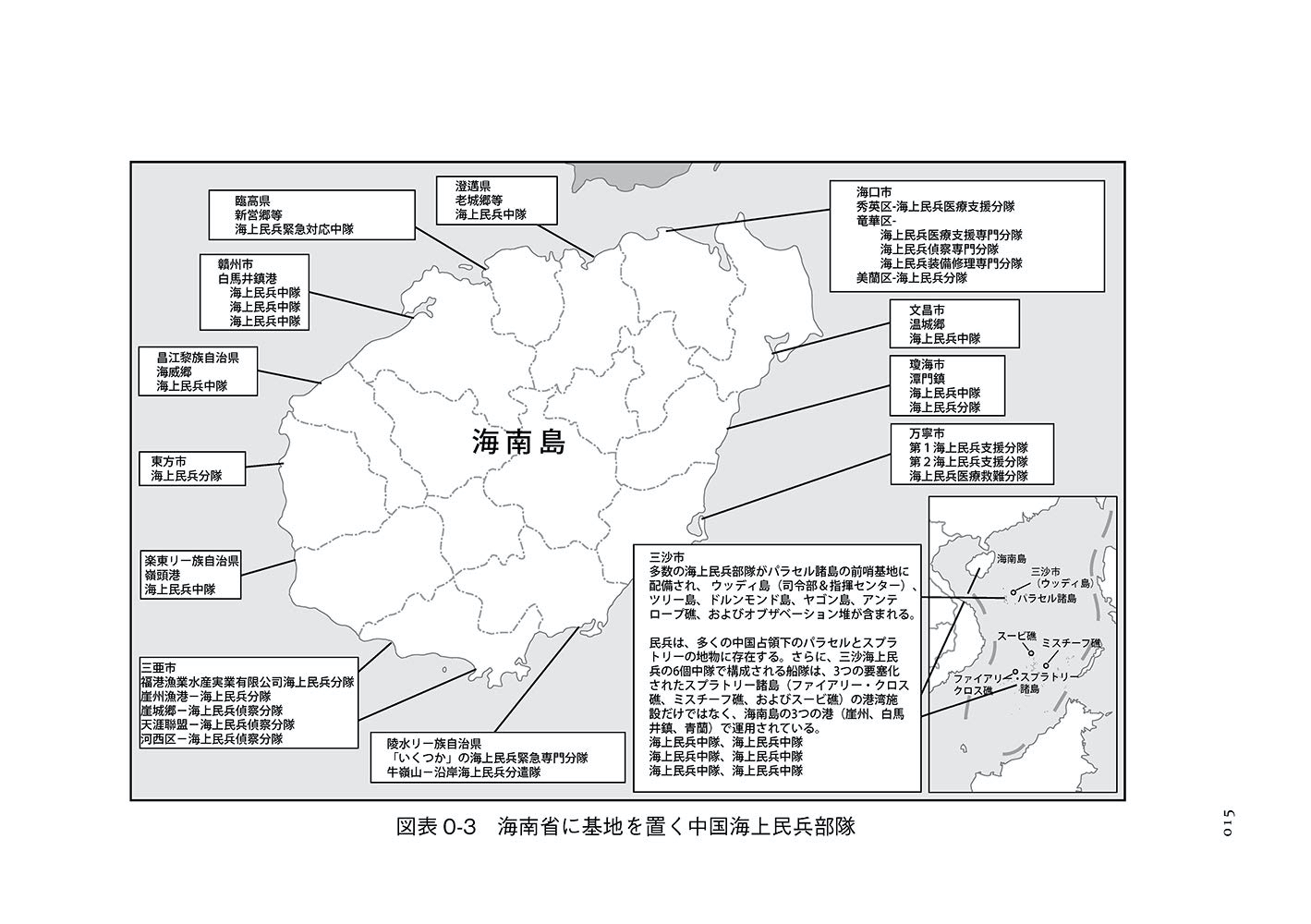

The maritime militia (海上民兵) has attracted considerable attention in the past decade, led by the efforts of Andrew Erickson and Conor Kennedy at the U.S. Naval War College, focused mainly onits role in supporting China’s claims in the South China Sea and East China Sea.6 Kevin McCauley and Conor Kennedy have also looked at the role of civilian ships in military power projection outside East Asia.7

What has received much less Western attention is the maritime militia’s role in large-scale combat operations, despite Chinese authors having written extensively on it since the PLA began serious consideration of a Taiwan invasion in the early 2000s. The Nanjing Military Region Mobilization Department director Guo Suqing observed in 2004 that a cross-strait island landing campaign would require large amounts of civilian shipping.8 He noted that there were many suitable ships available, some of which had already been retrofitted for wartime use, but warned that “the traditional form of last-minute non-rigorous civilian ship mobilization can no longer meet the needs of large-scale cross-sea landing operations.” Wang Hewen of the former General Logistics Department’s Institute of Military Transportation noted that efforts to strengthen the retrofitting of civilian vessels for military use had accelerated in 2003,9 and a 2004 article from the Shanghai Transportation War Preparedness Office outlined the retrofitting work underway there.10 In 2004, Zhou Xiaoping of the Naval Command College called for overhaul of the mobilization system, arguing that “if the traditional administrative order-style mobilization and requisition methods were still followed, it would be difficult to ensure the implementation of civilian ship preparation and mobilization.”11 The government and PLA acted on these concerns, and over the past twenty years the maritime militia has evolved into a major force multiplier for the PLAN in large-scale combat operations.

Operational Roles for the Maritime Militia in a Taiwan Invasion

Kennedy and Erickson have written at length on the militia’s peacetime mission to assert China’s maritime claims, centered on fishing boats that may or may not do any actual fishing. The militia forces discussed here are very different, encompassing large-capacity commercial vessels including container ships, general cargo ships, bulk carriers, tankers, roll-on-roll-off (RO-RO) ferries, barges, semisubmersibles, ocean-going tugboats, passenger ships, “engineering ships,” and others, as well as smaller vessels.13 Authors from the Army Military Transportation University noted in 2015 that the force consisted of over 5,000 ships organized into 89 militia transportation units, 53 waterway engineering units, and 143 units with other specializations.14

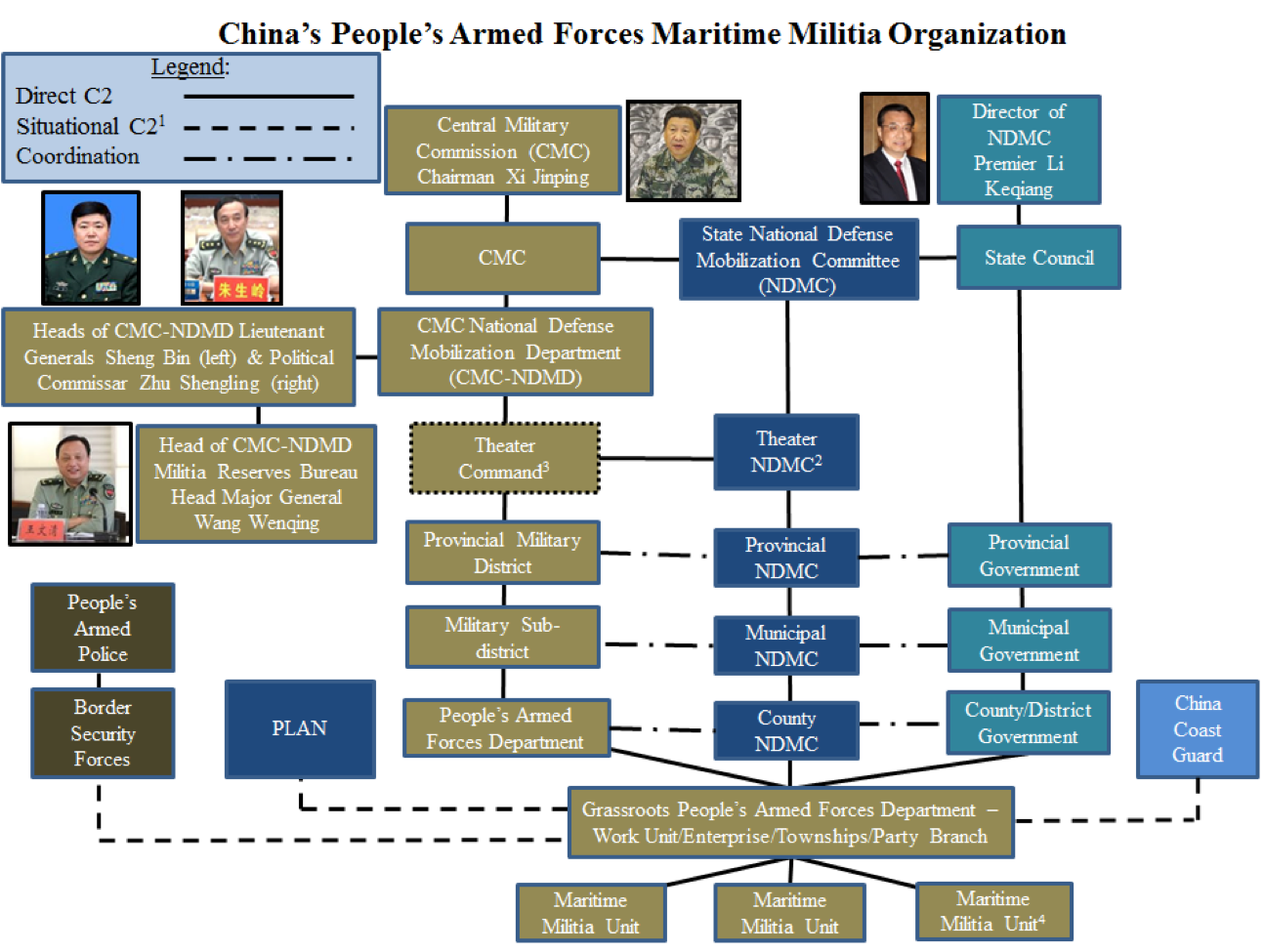

Unlike the U.S. Merchant Marine model, where government officers and crews take control of leased ships, Chinese maritime militia units are composed mostly of the regular crews of the mobilized ships, what the Central Military Commission (CMC) Militia and Reserve Bureau director called the “model of selecting militiamen according to their ship” (依船定兵模式).15 The close correlation between requisitioned ships and militia units is essential for integration into military operations. There need to be clear command relationships with the supported PLA units, and the crews need to be trained on their operational tasks, not to mention the increasingly important issue of legal rights and obligations in wartime. Local or provincial mobilization officials negotiate the requisitioning terms with the ship owners, either large shipping companies or individual owners, while the crews are inducted into militia units by a process that is not explained very clearly in the available writings. Several articles note that some militiamen are not enthusiastic about their role.16

PLA sources cite a wide range of wartime functions for the maritime militia. In a Taiwan invasion scenario, they include the following:

- Delivery of forces. The most obvious operational role for militia units is to carry forces to the battlefield, referred to as “military unit transportation and delivery” (部队运输投送). PLA sources list this as a primary role for civilian shipping, to include participating in the assault landing phase of the operation.17 There are several delivery modes contemplated, the most straightforward being through existing ports. A 2019 article on amphibious heavy combined arms brigades in cross-strait island landing operations noted that as part of the first echelon ashore, one of their most important tasks was to create the conditions for second echelon units to land through operations such as the seizure of ports and piers.18 Articles published in 2014 and 2019 on amphibious landing bases made the same point and included rapid repair of piers among the main tasks to help the second echelon get ashore.19 Other landing modes include lightering from cargo ships to shallow-draft vessels; semisubmersible vessels delivering amphibious vehicles or air-cushion landing craft;20 and RO-RO ships delivering amphibious forces to their launching point or directly to shore.21

- At-sea support. The PLAN has only a few replenishment ships, not enough to sustain the huge number of vessels that would be involved in a cross-strait invasion.22 Given the relatively short distances for a Taiwan landing, most PLAN ships would likely rely on shore-based support, but the service envisions using militia ships for at-sea replenishment as well, including fuel tankers and cargo ships fitted with equipment for alongside replenishment and helipads for vertical resupply.23 Militia ships would also provide emergency services including towing, rapid repair, firefighting, search and rescue, technical support, and even personnel augmentation to replace casualties aboard navy ships.24

- Over-the-shore logistical support. A discussion of logistical support in island landing operations noted the importance of fuel tankers laying pipelines to support forces ashore.25 The author did not specify maritime militia in this role, but given the prominence of tankers in other discussions of militia support, it seems likely they would take part in this activity as well. Requisitioned cargo ships will also play a major role in logistical support through captured ports or via lighters and barges to expedient floating docks.

- Medical support. The PLAN’s fleet of hospital ships could be overwhelmed by the casualties involved in a major landing operation. Militia would augment this force with containerized medical modules deployed on a variety of commercial ships, as well as smaller vessels providing casualty evacuation and first aid.26

- Obstacle emplacement and clearing. Several sources list emplacing and clearing mines and other obstacles among maritime militia tasks in a landing operation, without providing much further detail.27

- Engineering support. Maritime militia forces will not be passively waiting for first echelon units to open damaged ports. Tugboats, barges, salvage ships, crane ships, and dredgers will join the effort to clear obstacles, open channels, and repair docks and other facilities.28

- Reconnaissance, surveillance, and early warning. While much of this discussion has focused on large ships, the huge fleet of militia fishing boats would have a large role in a Taiwan operation as well, providing eyes and ears across the entire maritime theater.29

- Deception and concealment. One major advantage the PLAN derives from having hundreds of militia ships in the battlespace is the ability to hide its most valuable platforms among the radar clutter. Many sources list deception, camouflage, and feints among the militia’s tasks. One 2018 article explains that militia ships will “use corner reflectors, false radio signals, false heat sources, etc., to set up counterfeit ships, missiles, fighters and other targets on the sea … to cause the enemy to make wrong judgments and lure the enemy into attacking the false target.”30 Flooding the strait with false targets would severely complicate Blue efforts against the invasion fleet.

- Helicopter relay platform. The Taiwan Strait is relatively narrow, but a two-hundred-mile round trip each sortie still creates a significant strain for helicopter operations. Some militia ships will serve as “helicopter relay support platforms” (直升机中继保障平台), fitted with helipads, ammunition storage compartments, aviation fuel bladders and refueling equipment, limited repair facilities, and flight control support systems to keep the helicopters in the fight.31 … … …

***

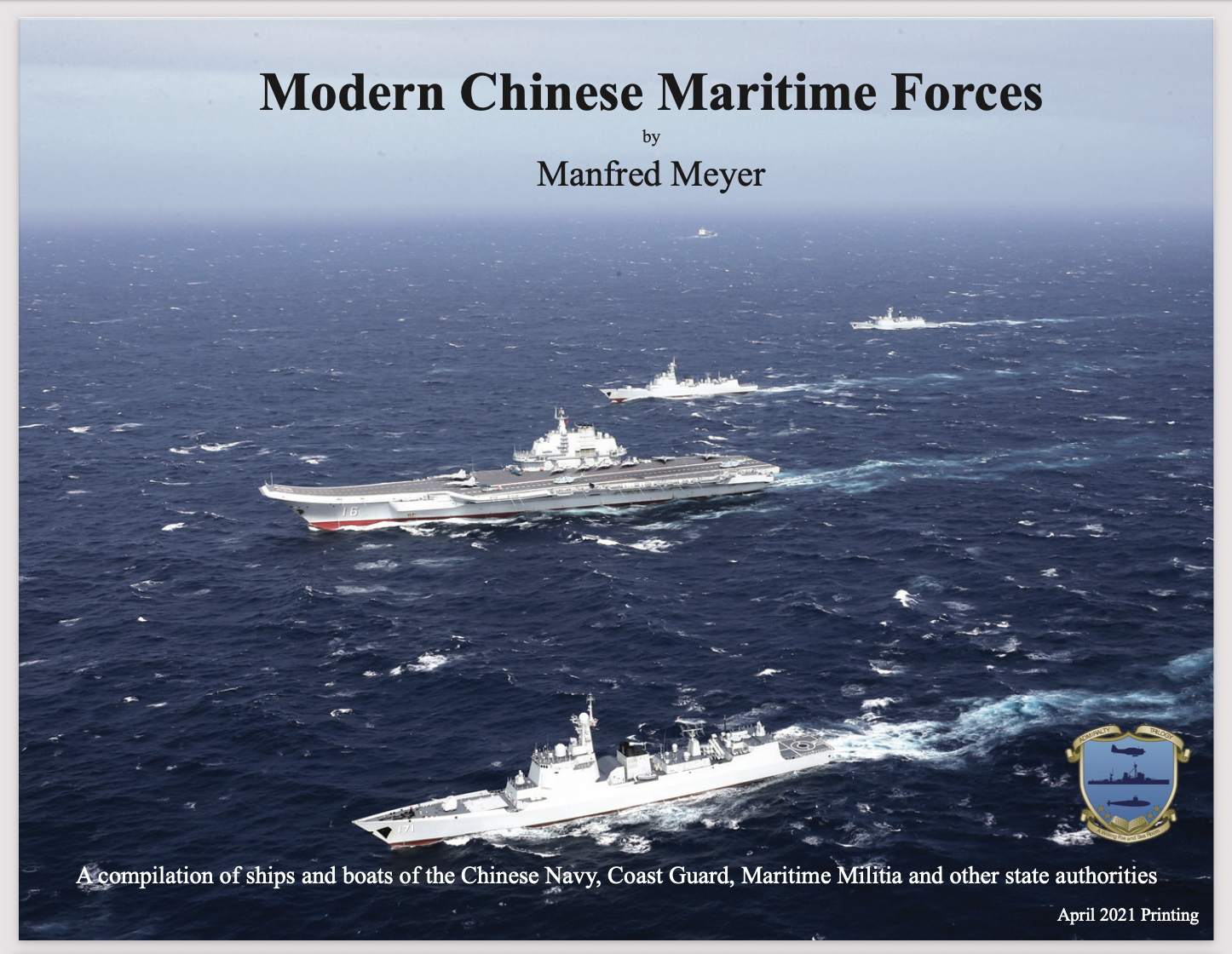

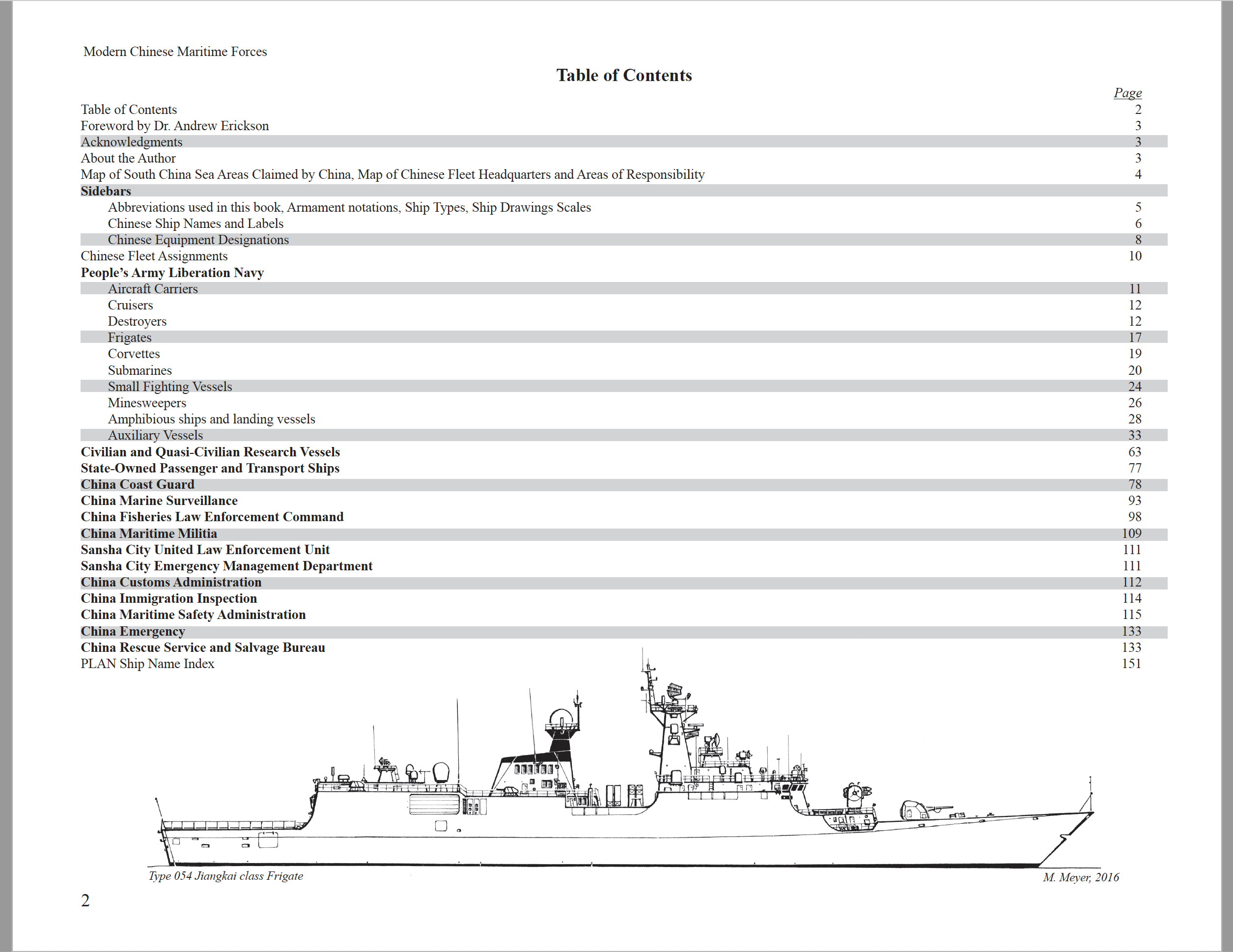

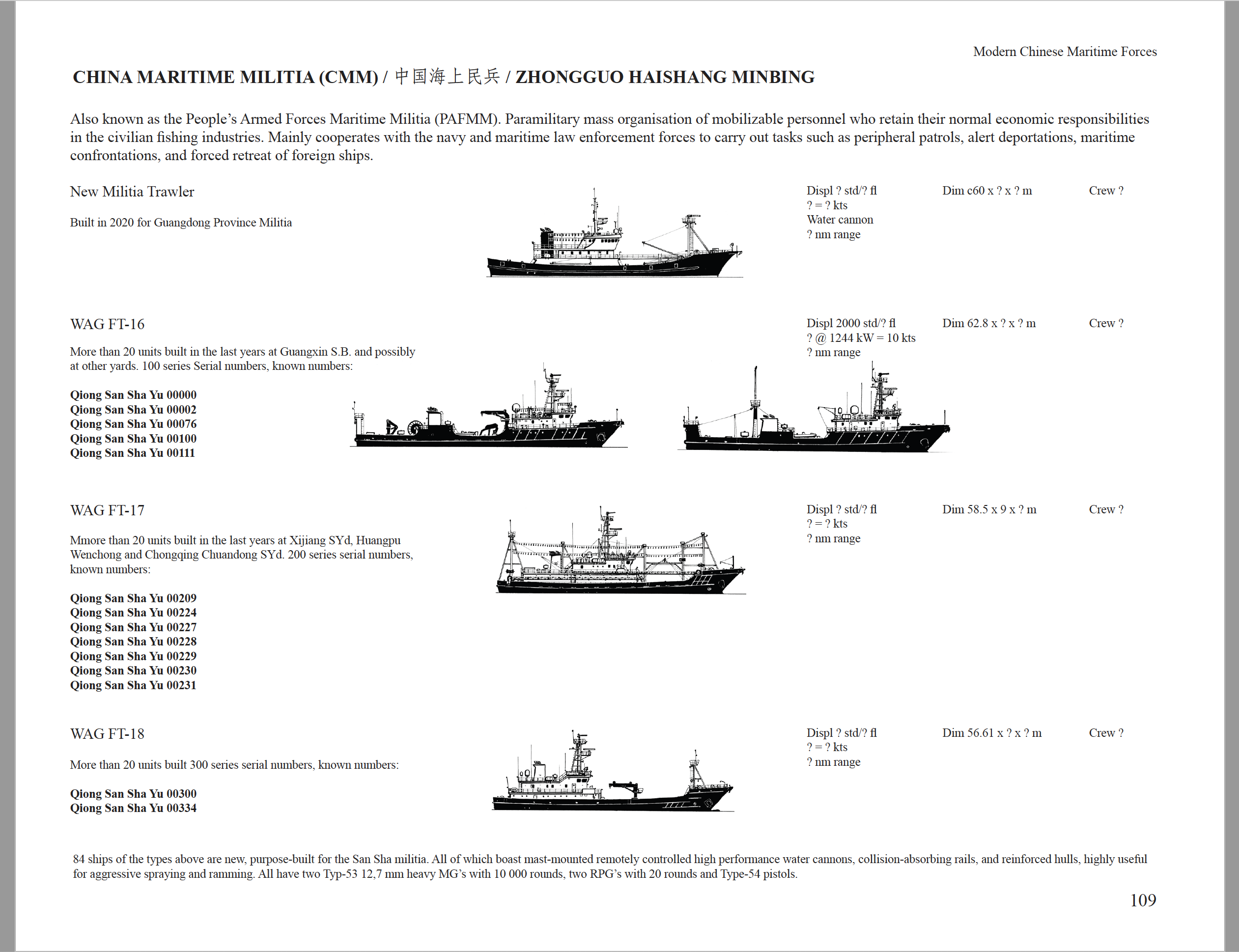

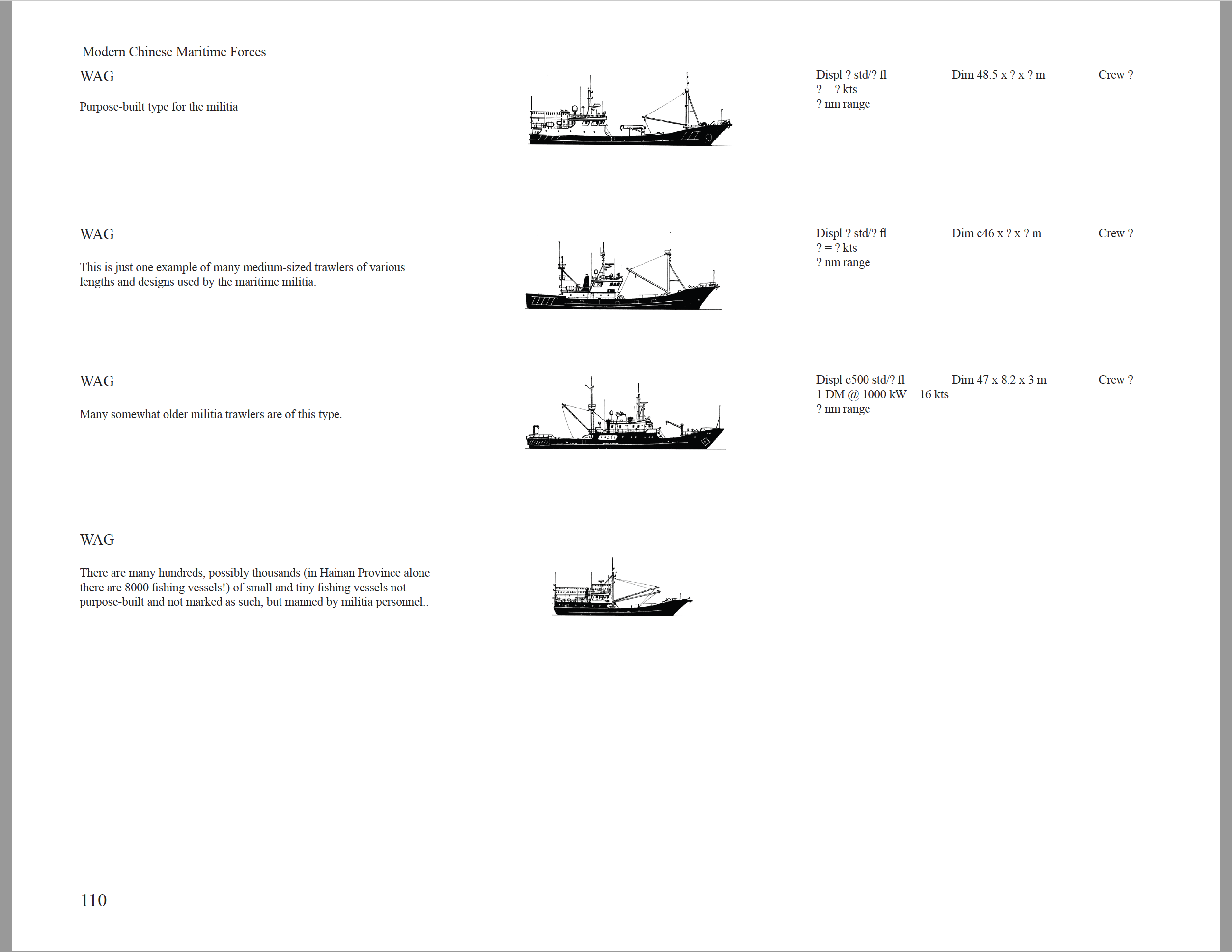

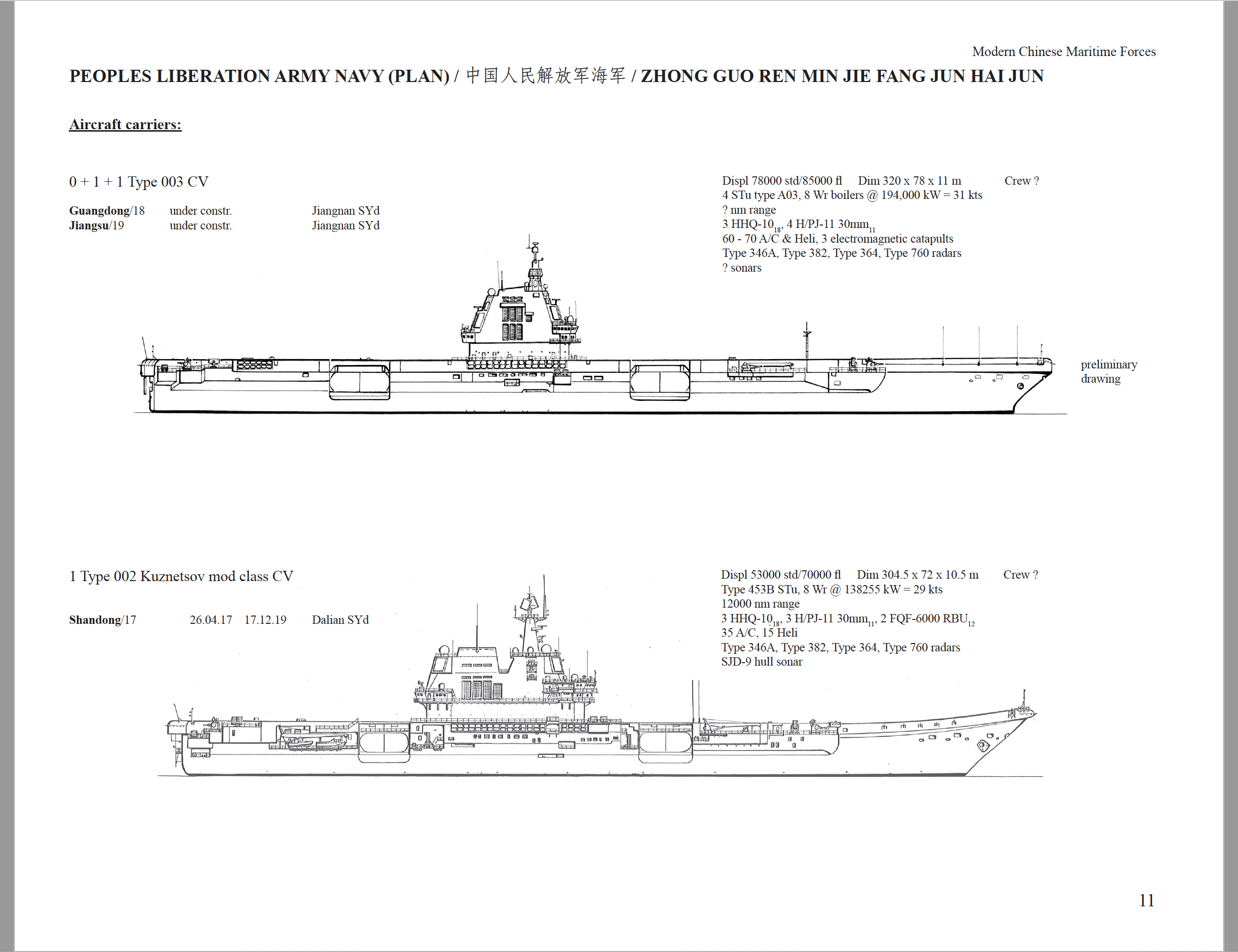

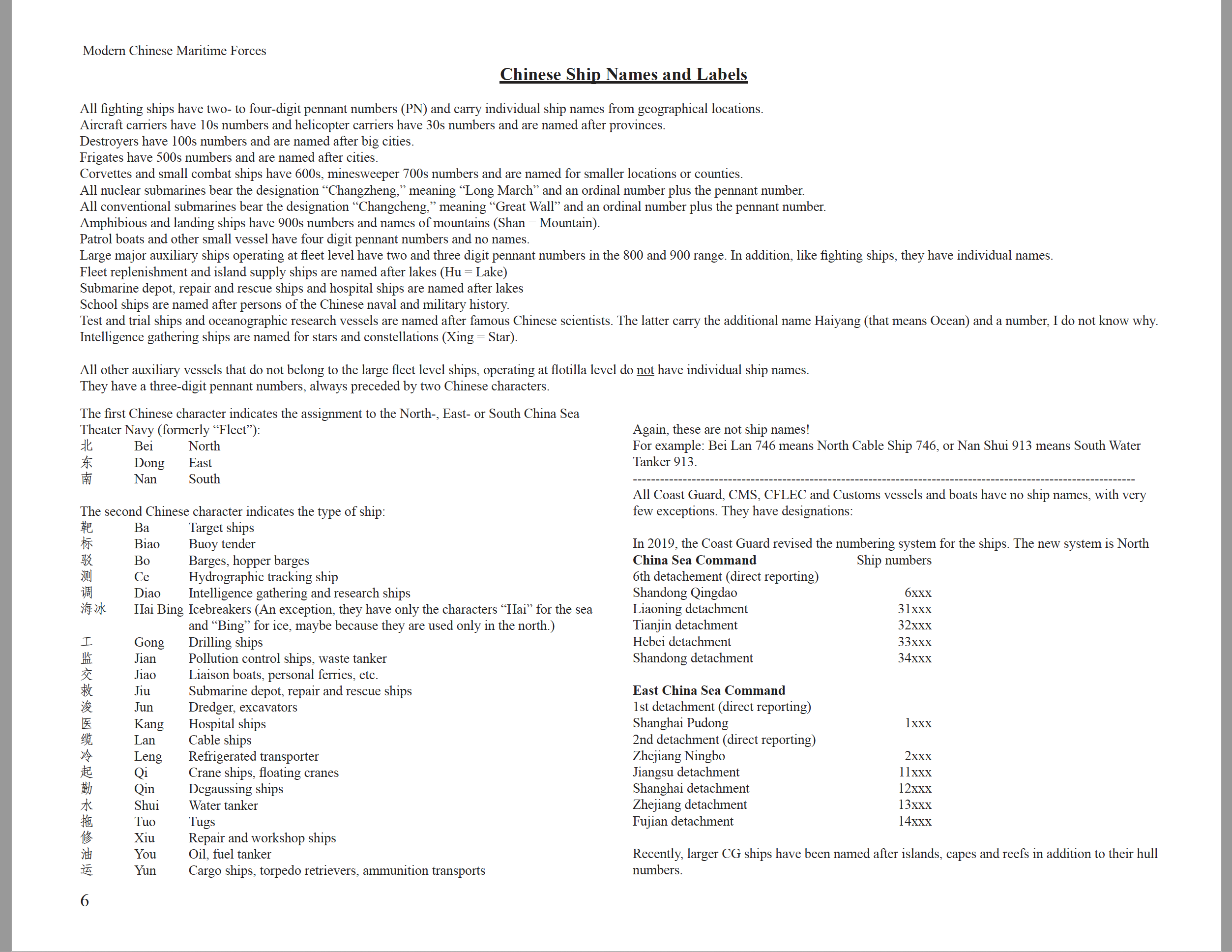

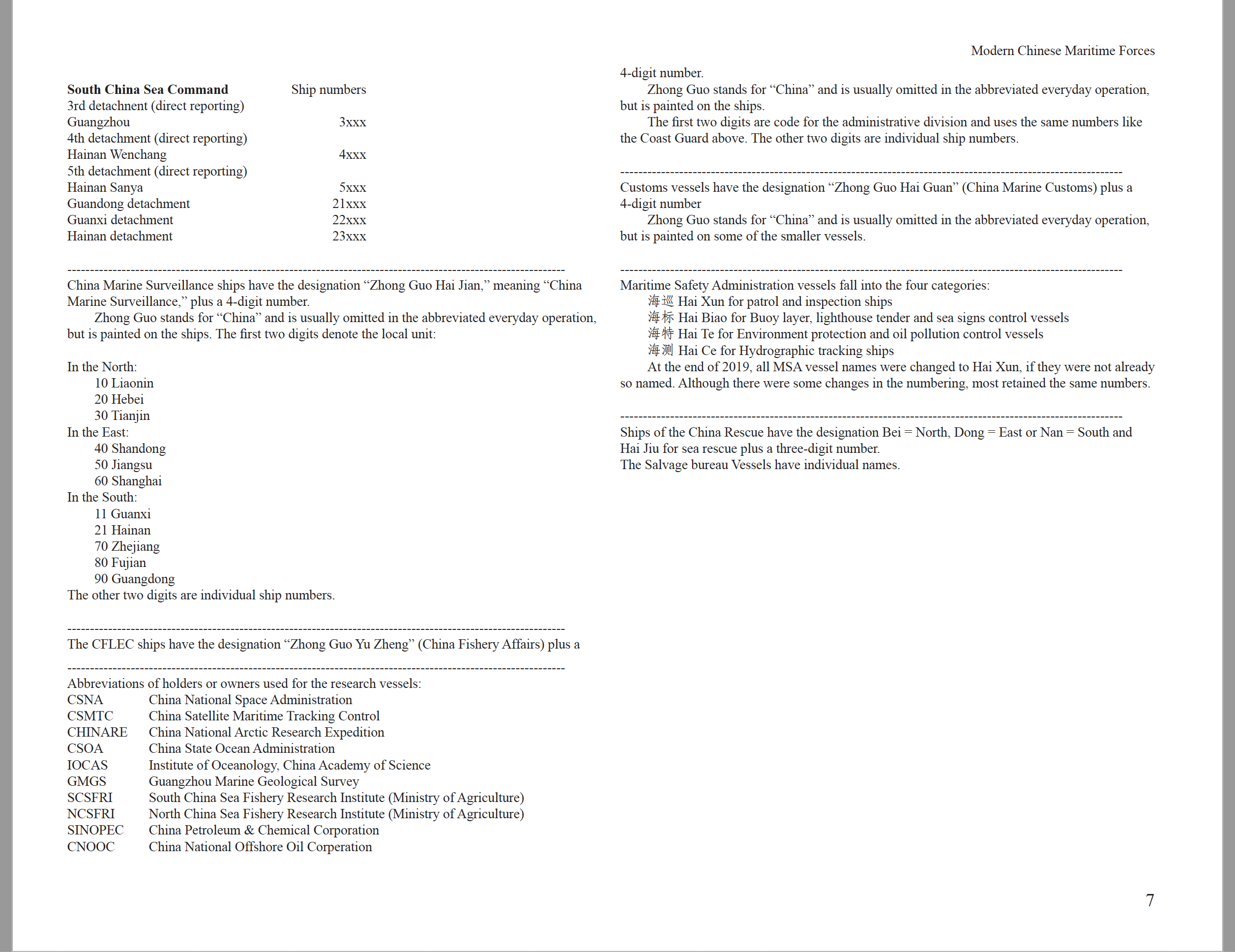

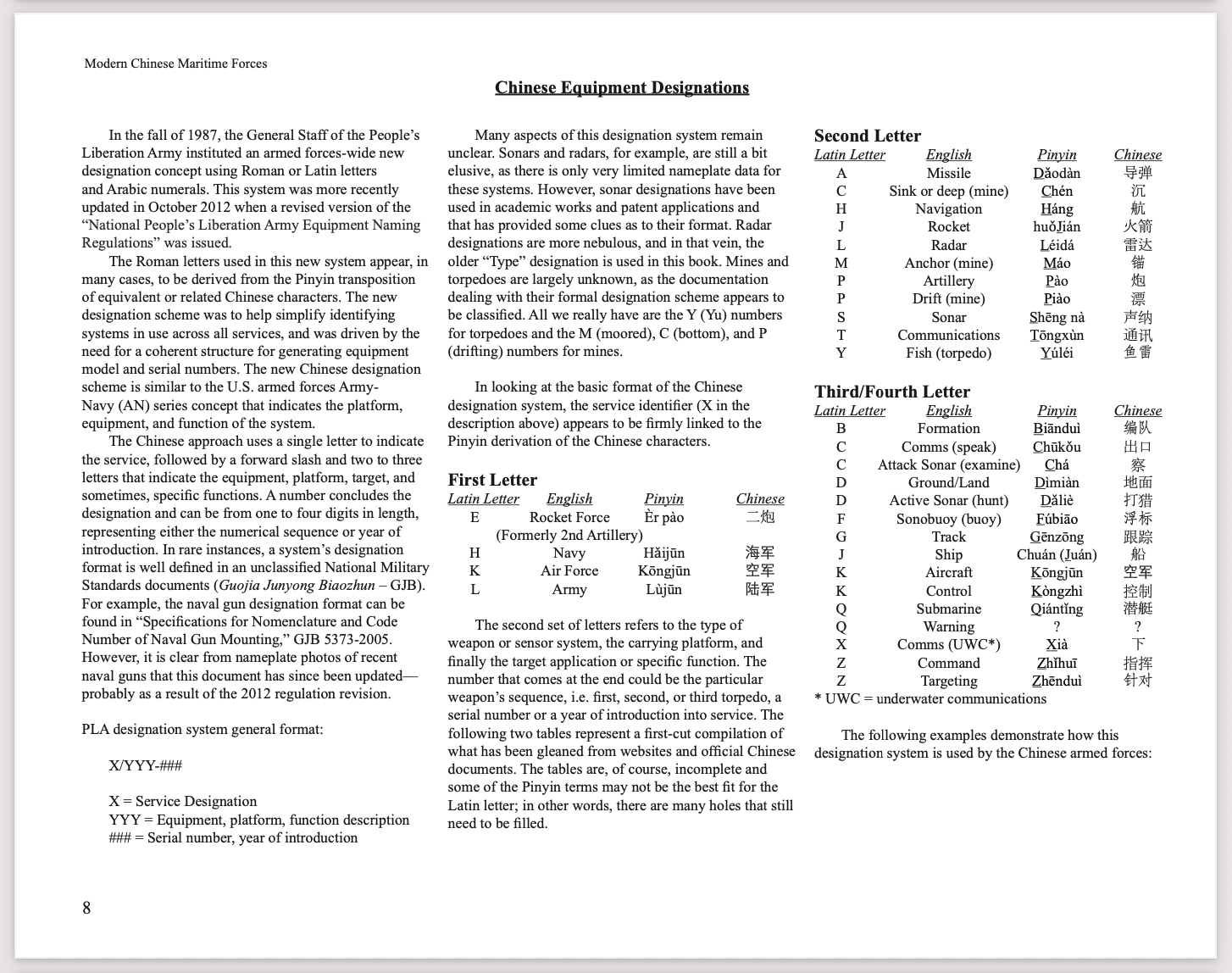

Manfred Meyer (edited by Larry Bond and Chris Carlson), Modern Chinese Maritime Forces (Admiralty Trilogy Group, 1 April 2022).

- This is the most comprehensive unclassified Chinese maritime order of battle, ship silhouettes, and data available anywhere. It tracks the world’s most-numerous Navy, Coast Guard, and Maritime Militia vessels in unrivaled detail. Even just flipping through this volume for a minute reveals the staggering scope and extent of PRC sea power across the waterfront today. I simply could not be more honored to contribute the Foreword!

- “A compilation of ships and boats of the Chinese Navy, Coast Guard, Maritime Militia and other state authorities”

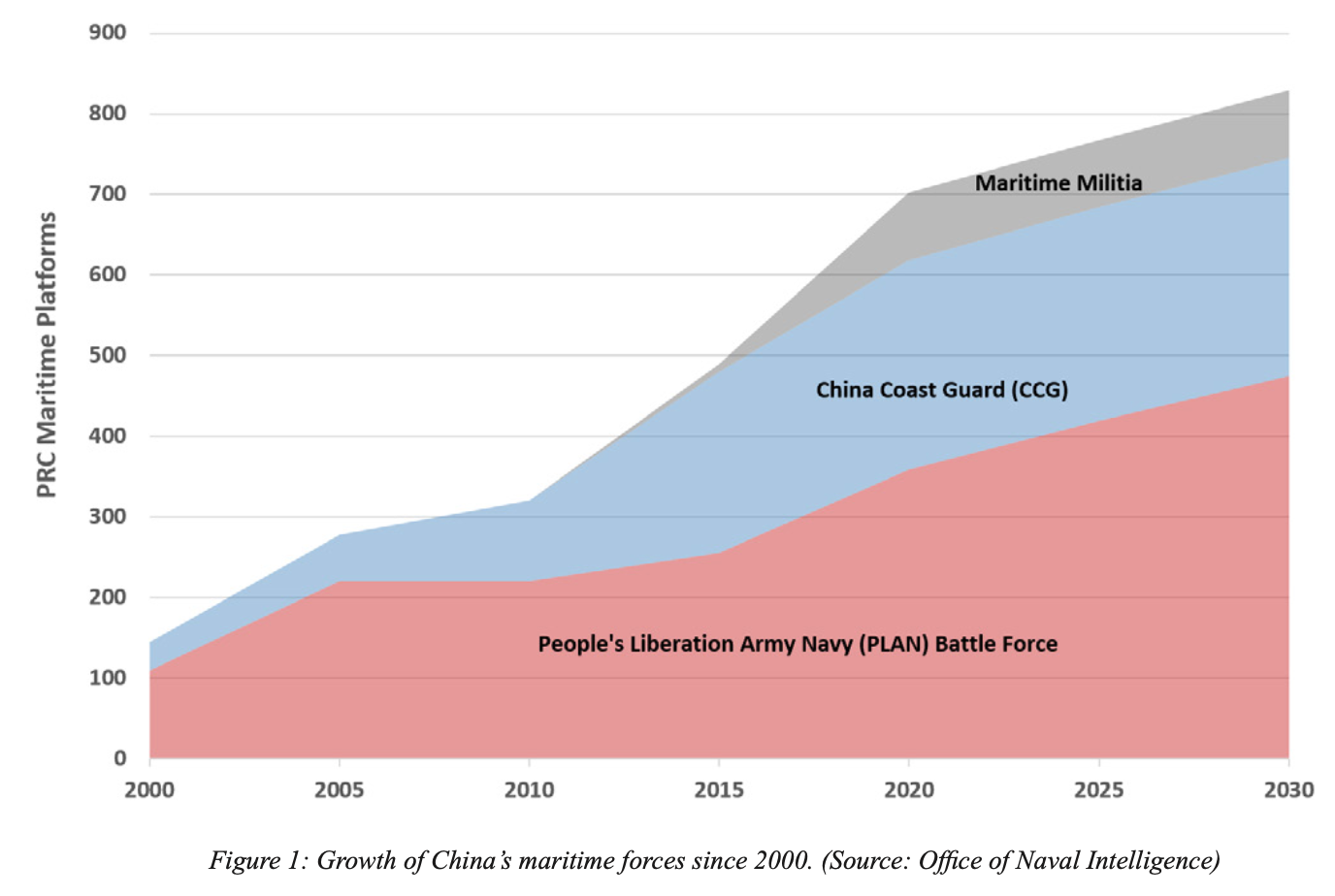

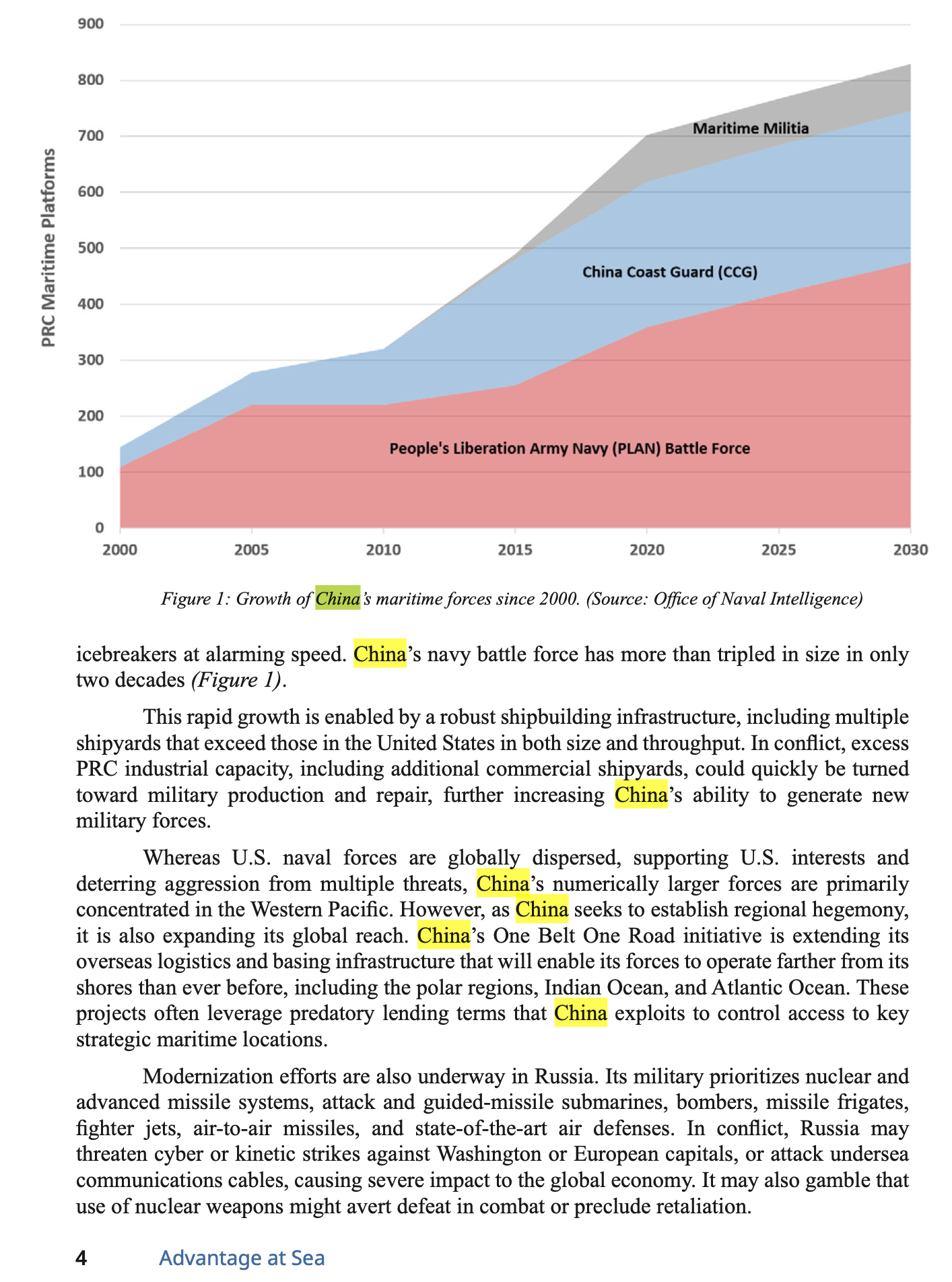

- In terms of ship numbers, each of China’s three sea forces is the world’s largest by a large margin. For the scenarios that most concern the U.S. and its regional allies, these numbers matter greatly.

- This suggests an important conclusion: China’s numerical sea force supremacy and the corresponding need for power projection and presence to counter it effectively demonstrates the need for a substantially-sized U.S. Navy. This book can help inform related deliberations and development. All the more reason to consult this handy compendium today!

- Click here to download sample content.

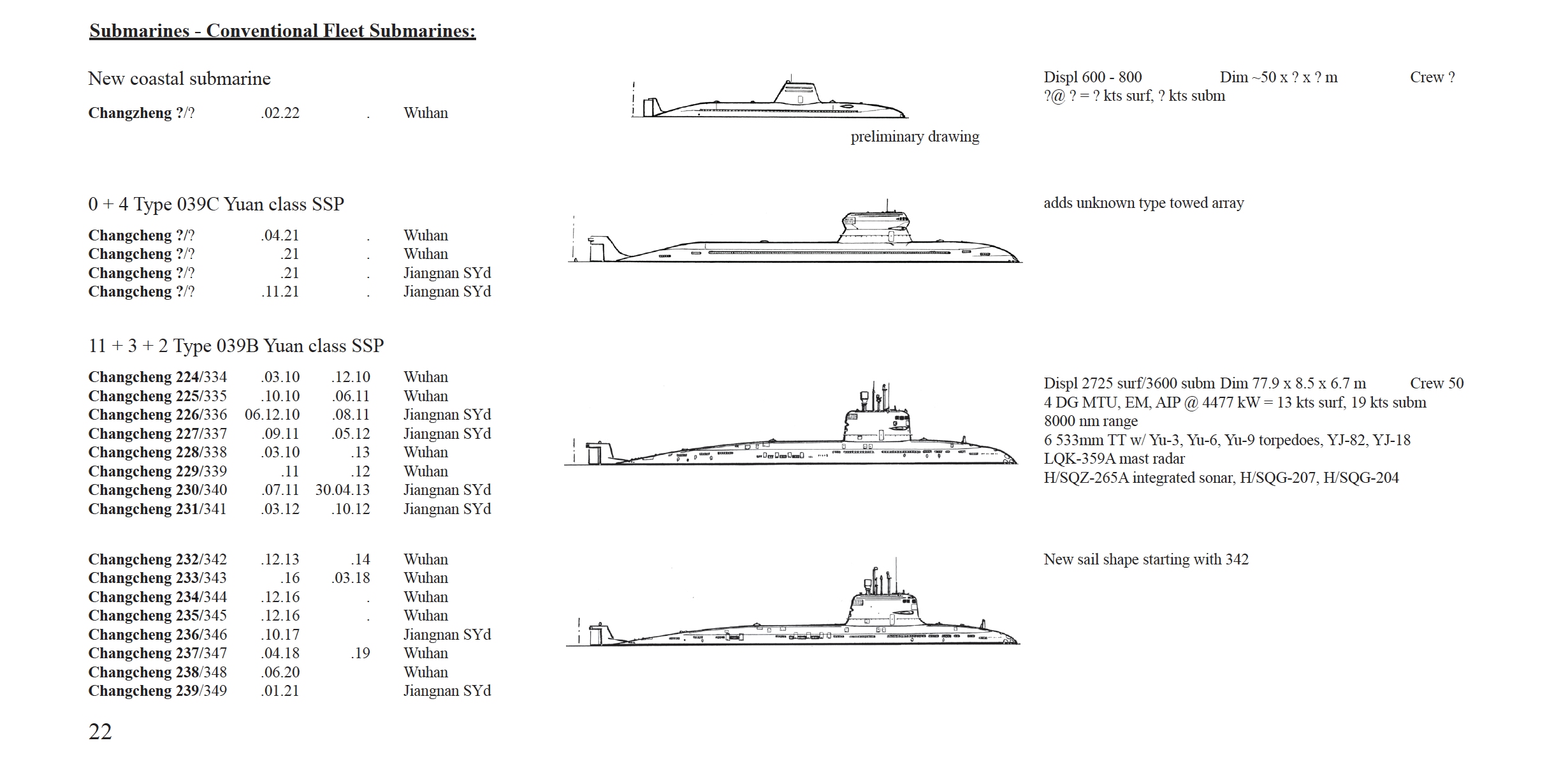

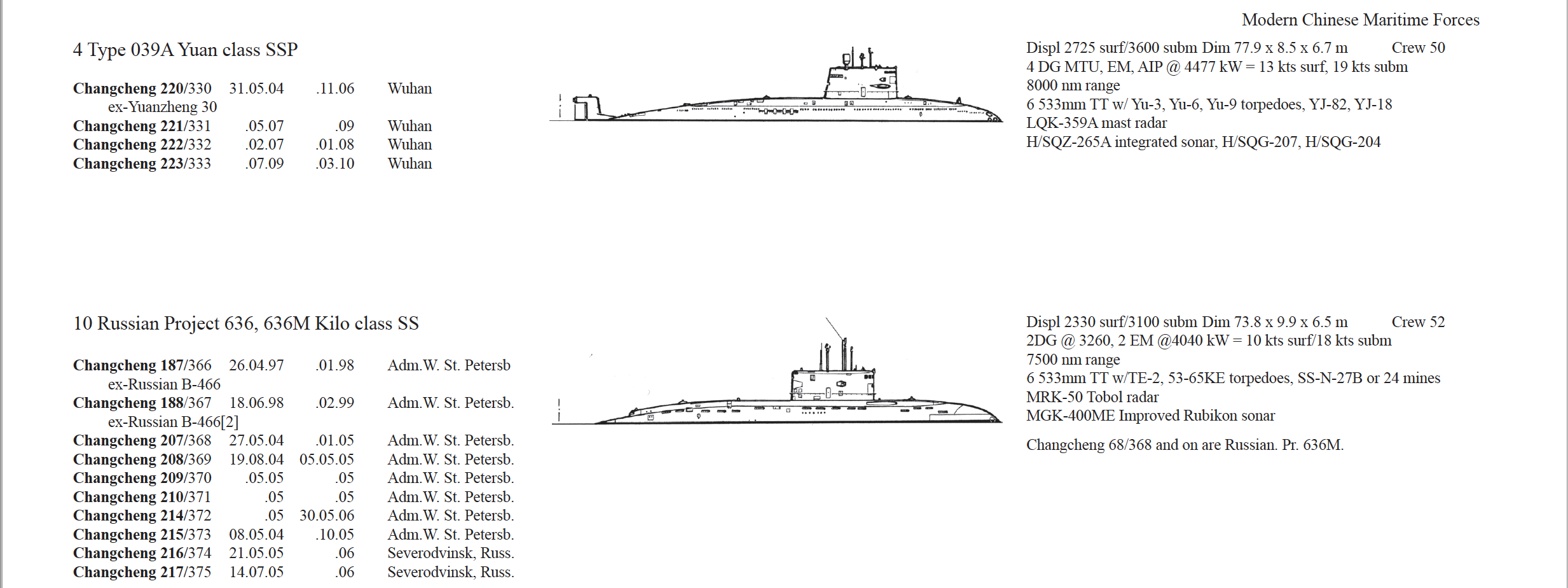

- Includes new entry on the Type 039C Yuan-class SSP (p. 22)…

- Check out the crane ship coverage on pp. 146–48!

- Unique PAFMM ship silhouettes and related information on pp. 109–10! Updated to include Guangdong Province vessels.

- You can order a copy here. Volume is updated periodically and single purchase includes access to future updates.

The Admiralty Trilogy Group (ATG) is pleased to announce that in addition to publishing games supporting its tactical naval game system, the Admiralty Trilogy, it has released its first nonfiction book. Click here to read the announcement.

Modern Chinese Maritime Forces, by Manfred Meyer, a noted artist and illustrator, provides up-to-the minute information on Chinese sea power. It lists all Chinese state vessels – not just the People’s Liberation Army Navy, but the Coast Guard, China Maritime Surveillance, China Fisheries law Enforcement Command, and many other state-sponsored agencies that carry out China’s policies at sea.

Over 570 drawings show everything from aircraft carriers to buoy tenders, accompanied by detailed information on their characteristics. Additional supporting material includes theater navy assignments for individual ships as well as descriptions of the Chinese systems for hull numbers and equipment designations. This compact book has the most complete unclassified information on Chinese state-owned vessels available anywhere.

I was honored to contribute a Foreword, in which I write: “Today, China’s maritime forces have the most ships of any nation. This pathbreaking book documents their force structure in unprecedented detail.”

Modern Chinese Naval Forces is available as either a searchable .pdf or a softcover 139-page book. Both can be bought as a bundle for a reduced price.

- Andrew S. Erickson, “Foreword,” in Manfred Meyer (edited by Larry Bond and Chris Carlson), Modern Chinese Maritime Forces (Admiralty Trilogy Group, 2022), 3.

FOREWORD

Ships are the ultimate embodiment of maritime strategy. Today, China’s maritime forces have the most ships of any nation. This pathbreaking book documents their force structure in unprecedented detail, making it an invaluable reference for all who seek to understand Beijing’s seaward surge and its manifold implications.

While remaining shackled to undeniable geostrategic realities on land, and hemmed in by “island chains” surrounding peripheral seas, China has gone to sea dramatically in both commercial and military dimensions. It is arguably the first continental power in two millennia to become a successful hybrid land-sea power and keep that sea change on course sustainably. Rather than operate freely on exterior lines like such geographically advantaged sea powers as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan, China must radiate sea power from interior lines in a way that currently prioritizes the assertion of increasing control over its disputed sovereignty claims in the Yellow, East, and South China Seas while seeking growing influence across the Indo-Pacific and nascent global access and presence.

To pursue these radiating ripples of maritime interests and activities, China draws on three sea forces, each the maritime component of one of its three armed forces: the (1) People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), (2) China Coast Guard (CCG), and (3) People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). Each Chinese sea force has the world’s most ships in its category. The volume covers in great depth China’s first and second sea forces, the PLAN and CCG, which contain the vast majority of its purpose-built government vessels. This fully-updated new edition has been revised to also include key PAFMM vessels. In doing so, it uniquely elucidates the three-pronged trident of Bejiing’s maritime force structure.

China’s ship numbers matter, greatly. First, China increasingly enjoys both quantity and quality at sea. In recent years China has overcome Cold War shipbuilding that produced crude Soviet-style hulks. The PLAN, naturally China’s most advanced sea force technologically, has most dramatically replaced backward rustbuckets with increasing numbers of sophisticated platforms. But the CCG and PAFMM are also modernizing significantly. Of China’s three sea forces, its coast guard has grown the most rapidly in numbers and enjoys the greatest global numerical superiority.

China’s shipbuilding juggernaut, powered by what until very recently was indisputably the world’s fastest-growing multi-trillion-dollar economy, has sustained rapid modernization of all three sea forces even as numbers of modern vessels grow substantially. China’s commercial shipbuilding juggernaut subsidizes overhead costs for construction of all three sea forces’ vessels, an impossibility for America’s military-focused shipbuilding industry. CCG construction is thus both economical and efficient. Commercial off-the-shelf drivetrains and electronics, together with a lack of complex combat systems and weapons, facilitate rapid assembly with multiple units constructed simultaneously.

Second, when it comes to deployment, even the most advanced ship simply cannot be in more than one place at once. Numbers matter significantly when it comes to maintaining presence and influence in vital seas. This is particularly true regarding the growing Sino-American strategic competition where the United States is playing a distant away game. U.S. Coast Guard cutters are focused near American waters, far from any international disputes, while the U.S. Navy is dispersed around the world, with many forces separated from maritime East Asia by responsibilities, geography, and time. Meanwhile, all three major Chinese sea forces remain focused first and foremost on the contested “Near Seas” (the Yellow, East, and South China Seas) and their immediate approaches, close to China’s homeland bases, land-based air and missile coverage, and supply lines.

For all these reasons, a complete unclassified order of battle for China’s Navy, Coast Guard, and Maritime Militia is long overdue. This pioneering volume finally fills that vital void. I commend it to everyone seeking to understand how China is making such great waves on the world’s oceans, and what course it may take in coming years.

Andrew S. Erickson

China Maritime Studies Institute

Newport, Rhode Island

REVIEWS

“This is a phenomenally thorough project, and I suspect it is both more complete and up to date than anything available to our armed forces at a classified or unclassified level. Herr Meyer’s meticulous research and superb drawing skills have produced a reference resource of unparalleled usefulness for anyone needing a handy reference for China’s vast naval and paranaval forces.”

– A.D. Baker III, former editor of Combat Fleets of the World

“I think it is for the first time that such a nearly complete overview of the Chinese maritime services has been made available to the public. The Chinese navy has risen in twenty years from a regional outdated navy to one of the global players which cannot be overlooked by the other world and regional powers.”

– Werner Globke, editor of Weyer’s Warships

“This is a badly-needed book: an accessible, compact guide to the ships of the Chinese navy and its related paramilitary services. All of the ships are shown in very clear scaled drawings, which give a good sense of size and configuration. No other guide of this type exists. That makes this quite possibly the only good reference to the Chinese fleets. No one concerned with current naval affairs can afford to miss it.”

– Dr. Norman Friedman, technical naval author

“I devoured this book. This is perhaps the most important and most comprehensive technical naval analysis book to appear in a generation. With the advent of Cold War II and the announced return to great power competition between the United States and the People’s Republic of China, this book should be on the bookshelf of every serious U.S. Navy officer and naval analyst. It will be the standard reference.”

– Captain Jerry Hendrix, USN (ret.), Center for a New American Security

***

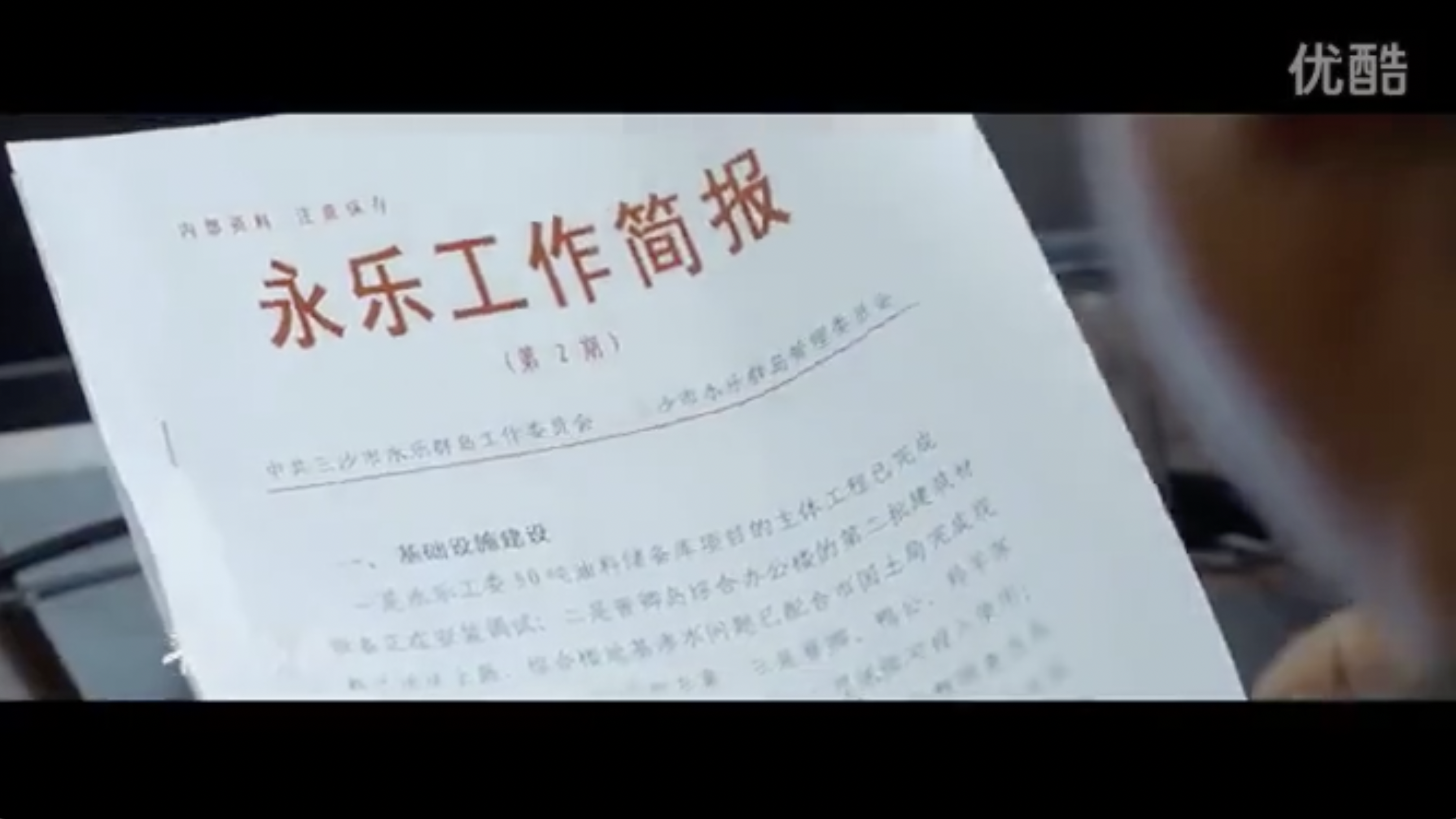

Official Music Video: 三沙海上民兵之歌 “The Song of the Sansha Maritime Militia”

Open source intelligence pro tip #1: if you’re trying to lurk in the shadows of deniability—however implausible—don’t record and release an official music video!

Zoe Haver has published a blockbuster expose on the Sansha Maritime Militia. Among many revealing details, she mentioned that this vanguard unit of China’s Armed Forces has its own music video.

Immediately below are the lyrics in Chinese, pinyin, and English. Key lines:

平时维权当先锋

Píngshí wéiquán dāng xiānfēng

In peacetime, be the vanguard of rights protection

急时参战打胜仗

Jí shí cānzhàn dǎ shèngzhàng

In times of emergency, join the battle and win the war

Be sure to watch all 2 minutes and 13 seconds for fascinating vignettes of personnel and operations. You may wish to pause and examine key frame-images such as that showing a militiaman reading the “永乐工作简报” (Yongle [Islands] Work Briefing). At the bottom of this post is a Chinese article with screenshots, associated images, and additional background.

My bottom line: the next time PRC officials appear to deny the existence of their own Maritime Militia, play them this music video! PAFMM karaoke, anyone?

Political Department of the PLA Hainan Province Sansha Garrison,

三沙海上民兵之歌 [The Song of the Sansha Maritime Militia], 12 April 2020.

三沙海上民兵之歌

Sān shā hǎishàng mínbīng zhī gē

The Song of the Sansha Maritime Militia

斗海浪 迎朝阳

Dòu hǎilàng yíng zhāoyáng

Fighting the waves, welcoming the rise of the morning sun

海上民兵英名传扬

Hǎishàng mínbīng yīngmíng chuán yáng

The Maritime Militia spreads its illustrious name

世代耕耘祖宗海

Shìdài gēngyún zǔzōng hǎi

Diligently cultivating the ancestral sea for generations

碧海丹心铸海疆

Bìhǎi dānxīn zhù hǎijiāng

Molding loyalty to the blue sea on the ocean frontier

战风云 为梦想

Zhàn fēngyún wèi mèngxiǎng

Fighting against the winds and clouds to achieve our dreams

海上民兵斗志昂扬

Hǎishàng mínbīng dòuzhì ángyáng

The Maritime Militia’s fighting spirit is soaring

不畏艰险担使命

Bù wèi jiānxiǎn dān shǐmìng

Not fearing hardship, carrying out the mission

建设三沙创辉煌

Jiànshè sān shā chuàng huīhuáng

Building Sansha to create glory

海上民兵海疆卫士

Hǎishàng mínbīng hǎijiāng wèishì

The Maritime Militia is the guardian of the ocean frontier

报效国家忠诚于党

Bàoxiào guójiā zhōngchéng yú dǎng

Serve the Country and be loyal to the Party

海上民兵海疆卫士

Hǎishàng mínbīng hǎijiāng wèishì

The Maritime Militia is the guardian of the ocean frontier

报效国家忠诚于党

Bàoxiào guójiā zhōngchéng yú dǎng

Serve the Country and be loyal to the Party

平时维权当先锋

Píngshí wéiquán dāng xiānfēng

In peacetime, be the vanguard of rights protection

急时参战打胜仗

Jí shí cānzhàn dǎ shèngzhàng

In times of emergency, join the battle and win the war

自豪吧 我们是三沙海上民兵

Zìháo ba wǒmen shì sān shā hǎishàng mínbīng

Be proud, we are the Sansha Maritime Militia

战风云 为梦想

Zhàn fēngyún wèi mèngxiǎng

Fighting against the winds and clouds to achieve our dreams

海上民兵斗志昂扬

Hǎishàng mínbīng dòuzhì ángyáng

The Maritime Militia’s fighting spirit is soaring

不畏艰险担使命

Bù wèi jiānxiǎn dān shǐmìng

Not fearing hardship, carrying out the mission

建设三沙创辉煌

Jiànshè sān shā chuàng huīhuáng

Building Sansha to create glory

海上民兵海疆卫士

Hǎishàng mínbīng hǎijiāng wèishì

The Maritime Militia is the guardian of the ocean frontier

报效国家忠诚于党

Bàoxiào guójiā zhōngchéng yú dǎng

Serve the Country and be loyal to the Party

海上民兵海疆卫士

Hǎishàng mínbīng hǎijiāng wèishì

The Maritime Militia is the guardian of the ocean frontier

报效国家忠诚于党

Bàoxiào guójiā zhōngchéng yú dǎng

Serve the Country and be loyal to the Party

平时维权当先锋

Píngshí wéiquán dāng xiānfēng

In peacetime, be the vanguard of rights protection

急时参战打胜仗

Jí shí cānzhàn dǎ shèngzhàng

In times of emergency, join the battle and win the war

自豪吧 我们是三沙海上民兵

Zìháo ba wǒmen shì sān shā hǎishàng mínbīng

Be proud, we are the Sansha Maritime Militia

前进吧 我们是三沙海上民兵

Qiánjìn ba wǒmen shì sān shā hǎishàng mínbīng

Advance forward, we are the Sansha Maritime Militia

【每周一曲】世代耕耘祖宗海的英雄们,也有豪迈的战歌!

【上期内容:登船讲话惹众怒,恶人部长把官辞,航母中招破四百,

三沙海上民兵之歌.mp300:0002:12本期【每周一曲】分享的这首歌,正好与今天的头条切题。

2012年7月24日,

斗海浪 迎朝阳

海上民兵英名传扬

世代耕耘祖宗海

碧海丹心铸海疆

战风云 为梦想

海上民兵斗志昂扬

不畏艰险担使命

建设三沙创辉煌

海上民兵海疆卫士

报效国家忠诚于党

海上民兵海疆卫士

报效国家忠诚于党

平时维权当先锋

急时参战打胜仗

自豪吧 我们是三沙海上民兵

战风云 为梦想

海上民兵斗志昂扬

不畏艰险担使命

建设三沙创辉煌

海上民兵海疆卫士

报效国家忠诚于党

海上民兵海疆卫士

报效国家忠诚于党

平时维权当先锋

急时参战打胜仗

自豪吧 我们是三沙海上民兵

前进吧 我们是三沙海上民兵

从MV中可见,在三沙民兵配发的枪械中,除了56式冲锋枪——

▲除了07作训服之外,三沙民兵也混用其他款式的迷彩服,

在曾经的国营渔业公司里,海上民兵们的渔船上架设重机枪、

▲从脚架部分来看,三沙民兵的这挺85高机成色不错

实际上,在近期海上民兵的几次实战经历中,

2015年7月21日,

银屿东北方向3海里处发现一艘外籍渔船在进行非法捕捞作业。 执法人员和民兵赶到后,这艘渔船仍然无视驱赶,继续作业。 根据上级命令,李遴君跳上对方渔船,不顾右臂被鱼叉划伤, 徒手擒住对方船长,和其他民兵一起制服了剩余船员。经过这次执法 ,李遴君“海上鲁智深”的名号不胫而走。“民兵也是兵, 也要有兵的胆气和血性。”他说。

▲已经年过六旬的李遴君,仍然战斗在保卫三沙的第一线

正如李老英雄所说,“民兵也是兵”。除了队列训练、轻武器射击、

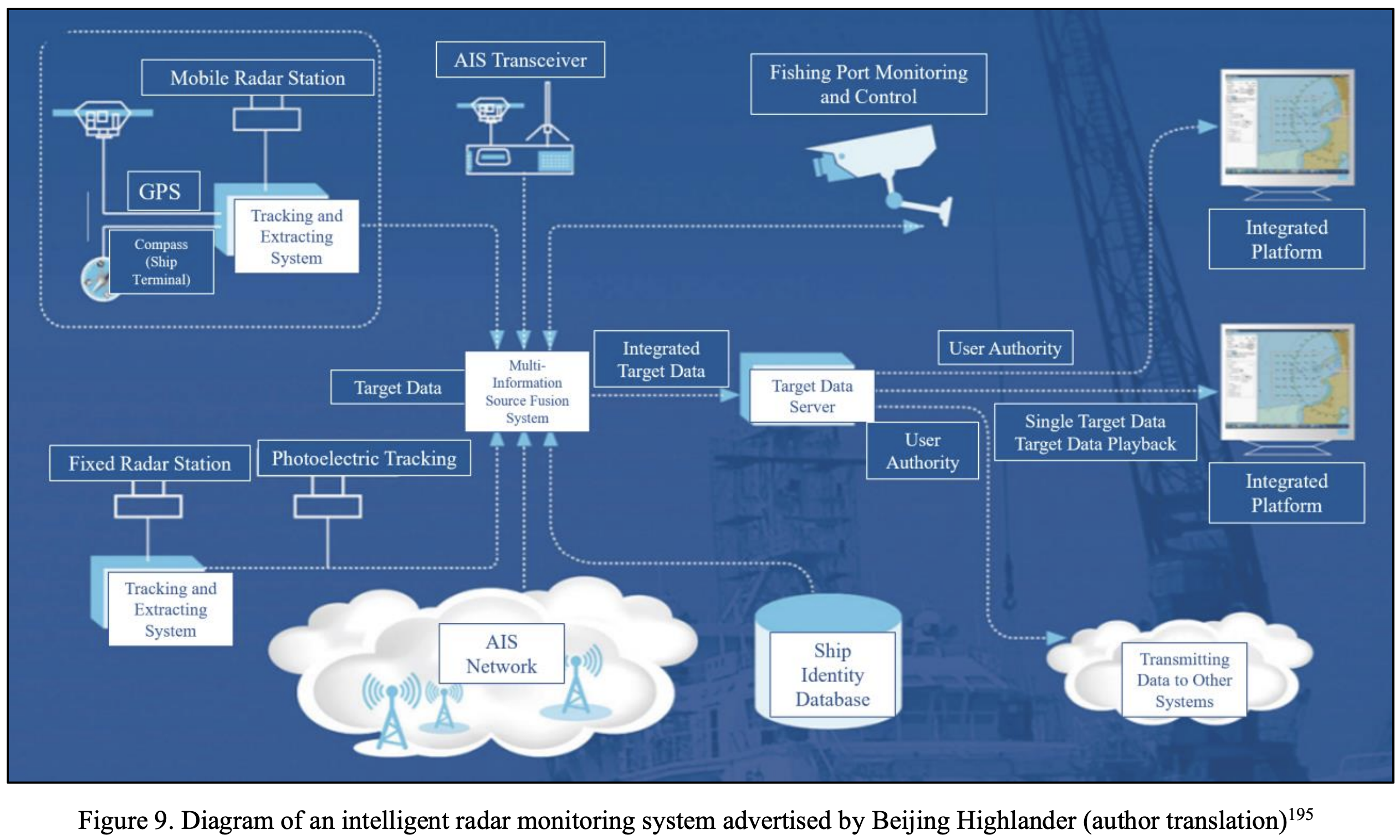

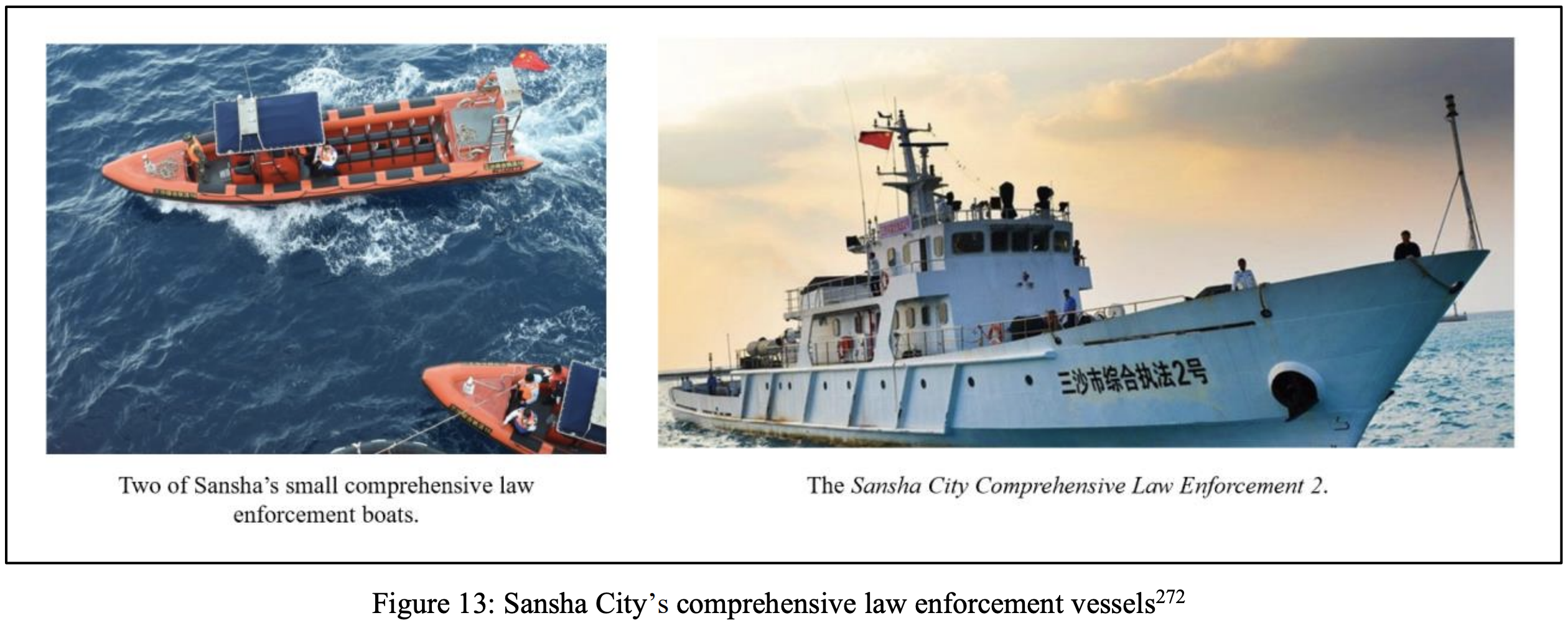

目前,各民兵哨所普遍配备了指挥系统、AIS系统、

▲这组截图反映了海上民兵从侦察上报到登船协助,

这首歌曲用词和结构上并不复杂,利于民兵学唱;

▲扎根三沙的一代代人们,用一生践行着“今朝立业南沙,千秋有功

***

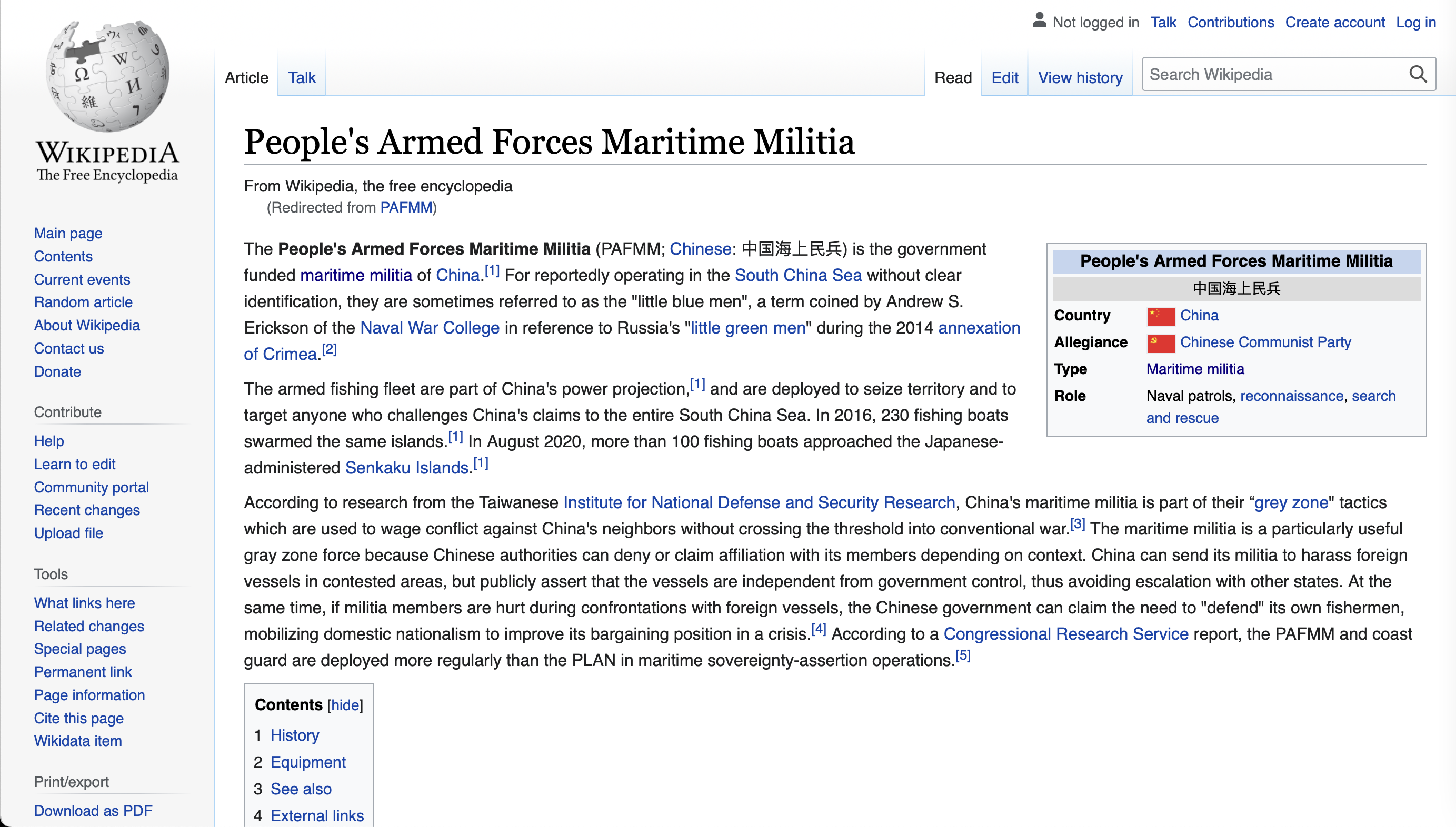

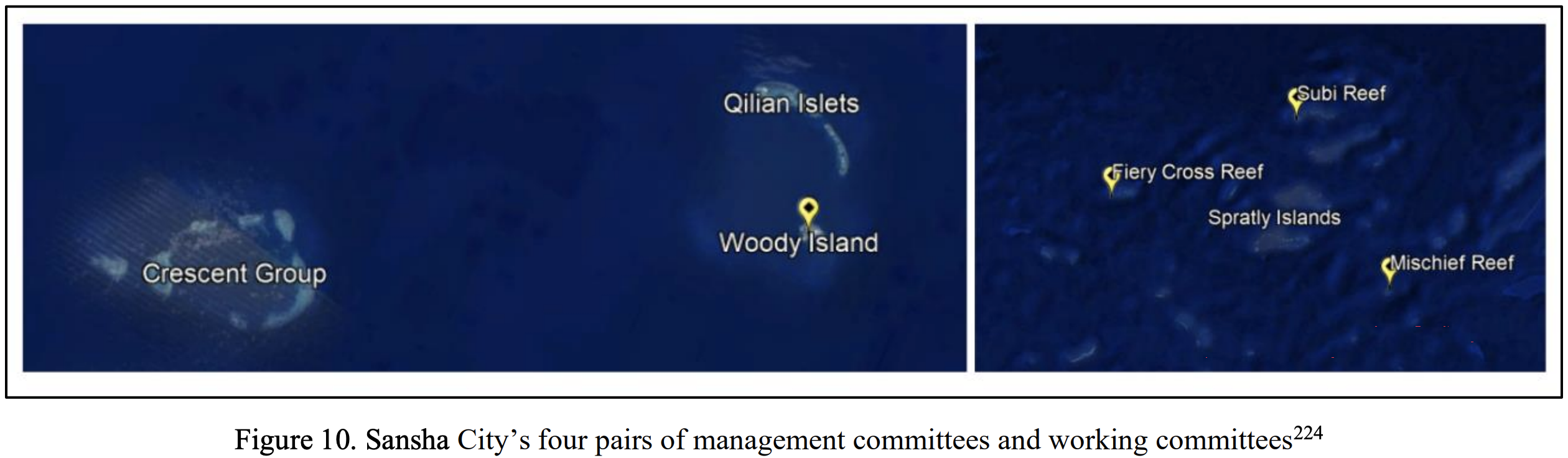

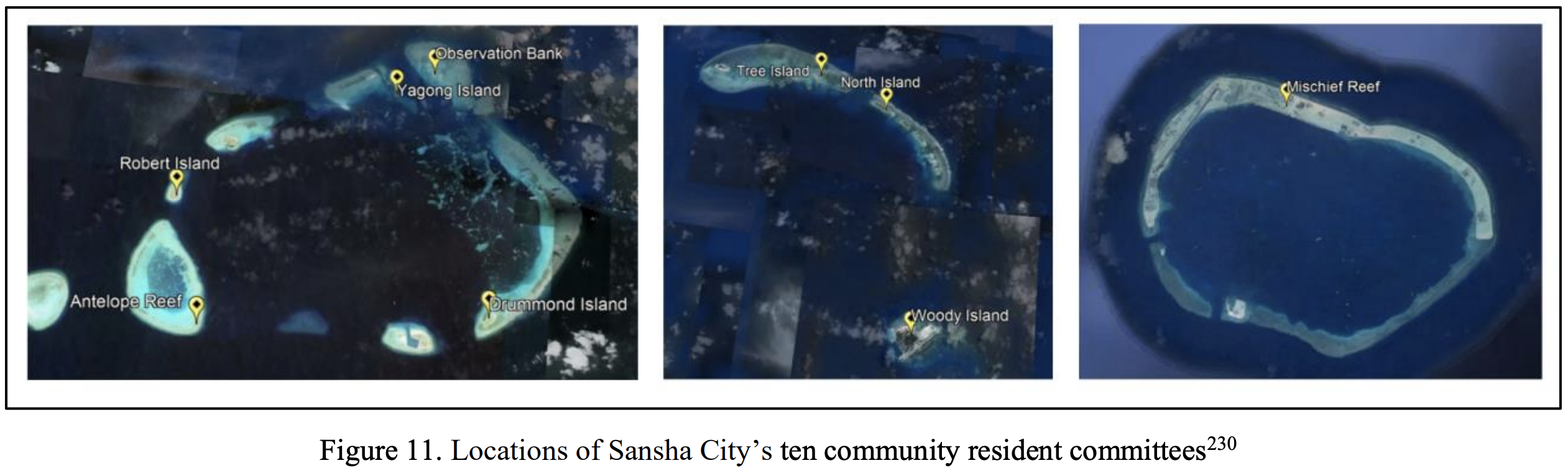

“People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia,” Wikipedia, entry as of 25 May 2022.

Jump to navigation Jump to search

|

|

The neutrality of this article is disputed. (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM; Chinese: 中国海上民兵, a.k.a. little blue men) is the government funded maritime militia of China.[1] For reportedly operating in the South China Sea without clear identification, they are sometimes referred to as the “little blue men”, a term coined by Andrew S. Erickson of the Naval War Collegein reference to Russia’s “little green men” during its 2014 annexation of Crimea.[2]

The armed fishing fleet are part of China’s power projection,[1] and are deployed to seize territory and to target anyone who challenges China’s claims to the entire South China Sea. In 2016, 230 fishing boats swarmed the same islands.[1] In August 2020, more than 100 fishing boats approached the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands.[1]

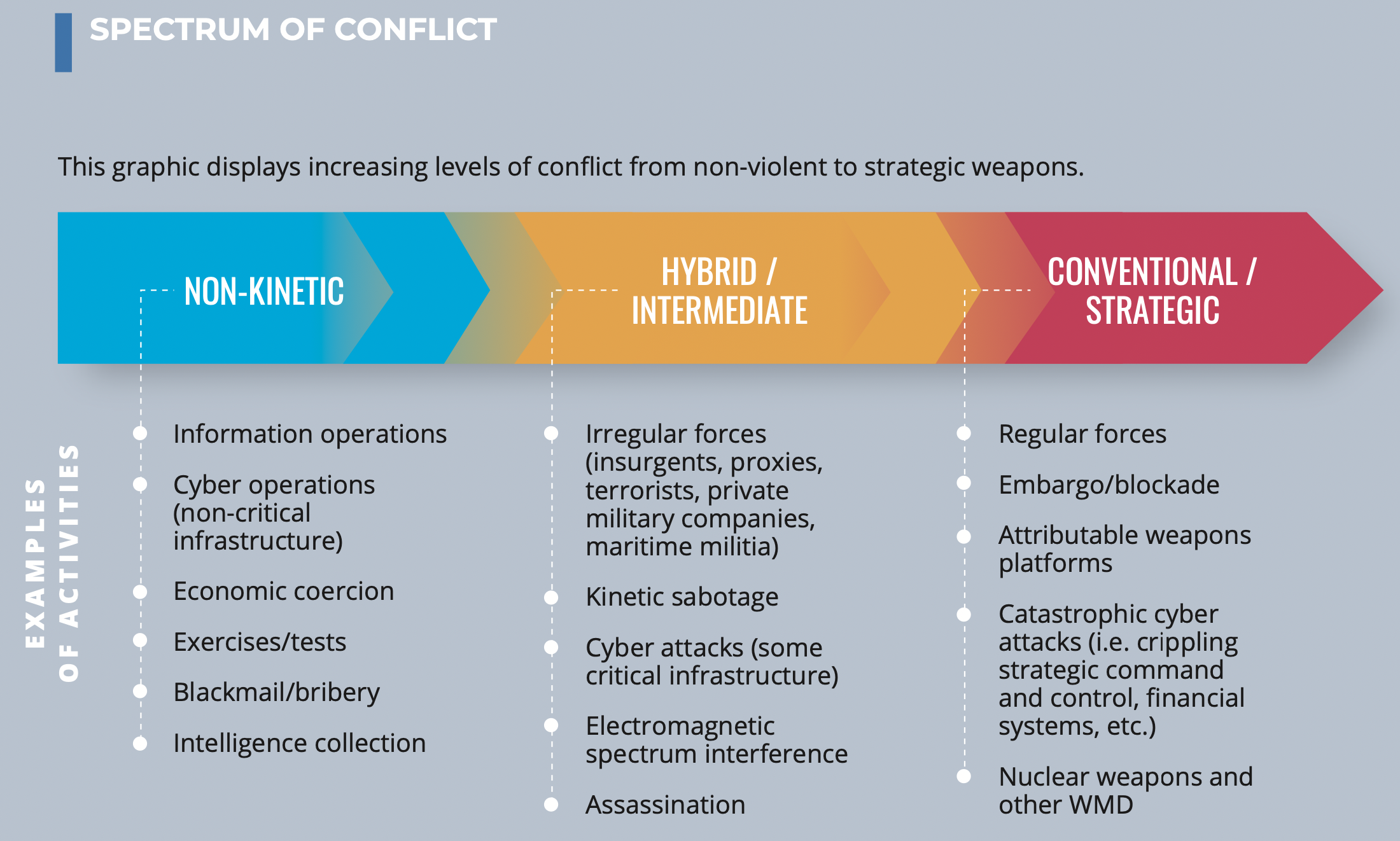

According to research from the Taiwanese Institute for National Defense and Security Research, China’s maritime militia is part of their “grey zone” tactics which are used to wage conflict against China’s neighbors without crossing the threshold into conventional war.[3] The maritime militia is a particularly useful gray zone force because Chinese authorities can deny or claim affiliation with its members depending on context. China can send its militia to harass foreign vessels in contested areas, but publicly assert that the vessels are independent from government control, thus avoiding escalation with other states. At the same time, if militia members are hurt during confrontations with foreign vessels, the Chinese government can claim the need to “defend” its own fishermen, mobilizing domestic nationalism to improve its bargaining position in a crisis.[4] According to a Congressional Research Service report, the PAFMM and coast guard are deployed more regularly than the PLAN in maritime sovereignty-assertion operations.[5]

| People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia | |

|---|---|

| 中国海上民兵 | |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Maritime militia |

| Role | Naval patrols, reconnaissance, search and rescue |

According to research from the Taiwanese Institute for National Defense and Security Research, China’s maritime militia is part of their “grey zone” tactics which are used to wage conflict against China’s neighbors without crossing the threshold into conventional war.[3] The maritime militia is a particularly useful gray zone force because Chinese authorities can deny or claim affiliation with its members depending on context. China can send its militia to harass foreign vessels in contested areas, but publicly assert that the vessels are independent from government control, thus avoiding escalation with other states. At the same time, if militia members are hurt during confrontations with foreign vessels, the Chinese government can claim the need to “defend” its own fishermen, mobilizing domestic nationalism to improve its bargaining position in a crisis.[4]According to a Congressional Research Service report, the PAFMM and coast guard are deployed more regularly than the PLAN in maritime sovereignty-assertion operations.[5]

History [edit]

The PAFMM was established after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) won the Chinese Civil War and forced the KMT to flee the mainland to Taiwan. The newly consolidated communist government needed to augment their maritime defenses against the nationalist forces, which had retreated offshore and remained entrenched on a number of coastal islands. Therefore, the concept of people’s war was applied to the sea with fishermen and other nautical laborers being drafted into a maritime militia. The nationalists had maintained a maritime militia during their time in power, but the communist government preferred to craft theirs anew given their suspicion of organizations created by the nationalists. The CCP also instituted a national level maritime militia command to unite the local militias, something the KMT had never done. In the early 1950s, the Bureau of Aquatic Products played a key role in institutionalizing and strengthening the maritime militia as it collectivized local fisheries. Bureau of Aquatic Products leaders were also generally former high ranking PLAN officers which lead to close relations between the organizations. The formation of the PAFMM was influenced by the Soviet “Young School” of military theory, which emphasized coastal defense over naval power projection for nascent communist powers.[6]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the PLAN established maritime militia schools near the three main fleet headquarters of Qingdao, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.[6] Through the first half of the 1970s, the maritime militia mostly stayed near shore and close to China. However, by the later 1970s, the maritime militia had evolved an important sovereignty support function which brought it into increasing conflict with China’s neighbors, especially in the South China Sea. The PAFMM contributed significantly to the Battle of the Paracel Islands, especially in providing amphibious lift capacity to Chinese forces. These early PAFMM successes have led to their use in nearly every maritime operation undertaken by the China Coast Guard and Navy, often harassing vessels from neighboring states.[6]

The maritime militia is believed to be behind a number of incidents in the South China Sea where high powered lasers were pointed at the cockpits of aircraft. This includes an attack against a Royal Australian Navy helicopter.[7]

In 2019, the United States issued a warning to China over aggressive and unsafe action by their Coast Guard and maritime militia.[8]

Equipment [edit]

Most vessels are issued with navigation and communication equipment while some are also issued small arms.[9] Some PLAFMM units are equipped with naval mine and anti-aircraft weapons.[10] The communications systems can be used both for communication and espionage. Often fishermen supply their own vessels, however, there are also core contingents of the maritime militia who operate vessels fitted out for militia work instead of fishing; these vessels feature reinforced bows for ramming and high powered water cannons.[11] The increasing sophistication of militia vessels’ communication equipment is a double-edged sword for Chinese authorities. New equipment, as well as training in its use, has substantially improved command, control, and coordination of militia units. However, the vessels’ resulting professionalism and sophisticated maneuvers make them more identifiable as government-sponsored actors, dampening their ability to function as a gray-zone force. Such improvements also potentially make militia vessels more threatening during at-sea confrontations, raising the risk of unintended escalations with foreign militaries.[4] The PAFMM has utilized rented fishing vessels and purpose-built ships in its operations.[5]

See also [edit]

- Cabbage tactics

- Chinese salami slicing theory

- Fishing industry in China

- Territorial disputes in the South China Sea

- Mutiny on Lurongyu 2682

- Little green men (Russo-Ukrainian War)

External links [edit]

References [edit]

- ^ Jump up to: ab c d Thomas, Jason (2 September 2020). “China’s ‘fishermen’ mercenaries”. The Weekend Australian. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^Jakhar, Pratik (15 April 2019). “Analysis: What’s so fishy about China’s ‘maritime militia’?”. monitoring.bbc.co.uk. BBC Monitoring. Archivedfrom the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^“DIPLOMACY: Maritime militia warning issued”. Taipei Times. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 8 July2020.

- ^ Jump up to: ab Luo, Shuxian; Panter, Jonathan (January–February 2021). “China’s Maritime Militia and Fishing Fleets: A Primer for Operational Staffs and Tactical Leaders”. Military Review. 101 (1): 6–21. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: ab “Ronald O’Rourke, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Implications for U.S. Interests—Background and Issues for Congress, R42784. Congressional Research Service. pp. 13, 76”. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- ^ Jump up to: ab c Grossman, Derek; Ma, Logan (6 April 2020). “A Short History of China’s Fishing Militia and What It May Tell Us”. rand.org. RAND Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 9 July2020.

- ^Yeo, Mike (31 May 2019). “Testing the waters: China’s maritime militia challenges foreign forces at sea”. Defense News. Retrieved 9 July2020.[dead link]

- ^Sevastopulo, Demetri; Hille, Kathrin (28 April 2019). “US warns China on aggressive acts by fishing boats and coast guard”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^Owens, Tess (1 May 2016). “China Is Reportedly Training a ‘Maritime Militia’ to Patrol the Disputed South China Sea”. vice.com. Vice News. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^Chan, Eric. “Escalating Clarity without Fighting: Countering Gray Zone Warfare against Taiwan (Part 2)”. globaltaiwan.org. The Global Taiwan Institute. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^Manthorpe, Jonathan (28 April 2019). “Beijing’s maritime militia, the scourge of South China Sea”. Asia Times. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

***

中国人民軍海上民兵

中国人民軍海上民兵(ちゅうごくじんみんぐんかいじょうみんぺい)は、中国の政府出資の海上民兵である[1]。南シナ海で活動していると報じられていることから、2014年のクリミア併合時のロシアの「リトル・グリーン・メン」に言及した海軍兵学校のアンドリュー・S・エリクソンの造語である「リトル・ブルー・メン」と呼ばれることもある[2]。

武装した漁船団は中国のパワープロジェクション[1]の一環であり、領土を掌握し、南シナ海全体の中国の主張に異議を唱える者を標的にするために配備されている。2016年には230隻の漁船が同じ島に群がった[1]。2020年8月には、日本が管理する尖閣諸島に100隻以上の漁船が嫌がらせを行った[1]。

参考文献[編集]

- ^ a b c d Thomas, Jason (2020年9月2日). “China’s ‘fishermen’ mercenaries”. The Weekend Australian

- ^ Jakhar, Pratik (2019年4月15日). “Analysis: What’s so fishy about China’s ‘maritime militia’?”. monitoring.bbc.co.uk. BBC Monitoring. 2020年7月25日閲覧。

最終更新 2021年12月19日 (日) 00:42 (日時は個人設定で未設定ならばUTC)。

***

中国海上民兵 [编辑]

中國海上民兵是对中华人民共和国政府资助海上民兵的指控[1],据称以武裝漁船方式為外界所認識。

观点[编辑]

武装渔船队是中国力量投射的一部分[1],部署渔船是为了控制有争议海上领土、海岛(包括南海、钓鱼台列屿等)。由于在南海活动时没有明确的身份标识,他们有时被[谁?]称为 「小蓝人」[註 1][2]。

注释[编辑]

参考文献[编辑]

- ^ 跳转至: 1.0 1.1 Thomas, Jason. China’s ‘fishermen’ mercenaries. The Weekend Australian. 2020-09-02 [2020-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-15).

- ^ Jakhar, Pratik. Analysis: What’s so fishy about China’s ‘maritime militia’?. monitoring.bbc.co.uk. BBC Monitoring. 15 April 2019 [25 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-15).

参见[编辑]

本页面最后修订于2022年2月17日 (星期四) 18:41。

***

- Now in its 139th (!) iteration, this periodically-updated Library of Congress report is indispensable for policy-makers and analysts alike!

- If you have trouble accessing the website above, please download a cached copy here.

- You can also click here to access the report via the public CRS website.

KEY EXCERPTS:

p. 9

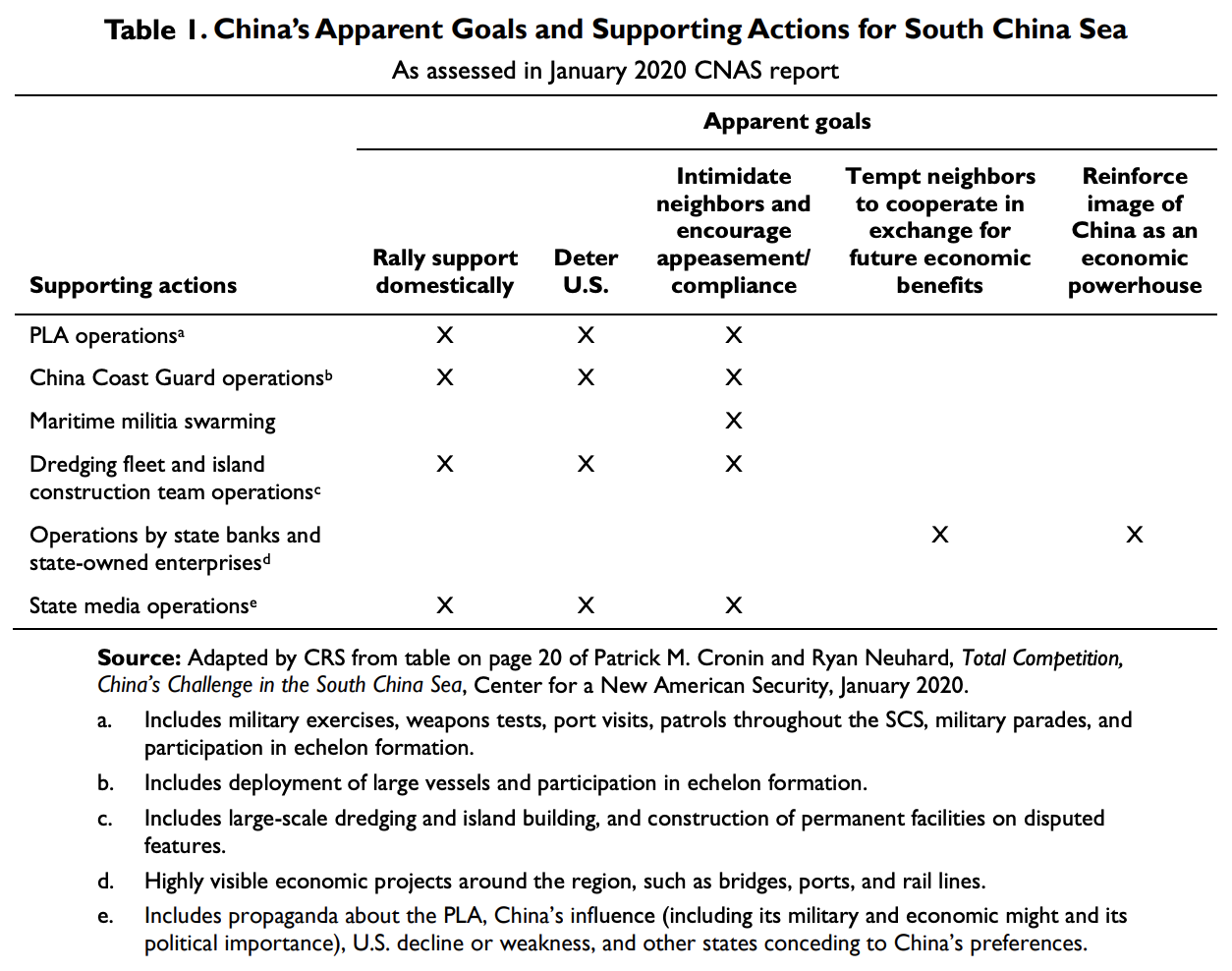

“Salami-Slicing” Strategy and Gray Zone Operations

Observers frequently characterize China’s approach to the SCS and ECS as a “salami-slicing” strategy that employs a series of incremental actions, none of which by itself is a casus belli, to gradually change the status quo in China’s favor. Other observers have referred to China’s

p. 10

approach as a strategy of gray zone operations (i.e., operations that reside in a gray zone between peace and war), of incrementalism,29 creeping annexation30 or creeping invasion,31 or as a “talk and take” strategy, meaning a strategy in which China engages in (or draws out) negotiations while taking actions to gain control of contested areas.32 An April 10, 2021, press report, for example, states

China is trying to wear down its neighbors with relentless pressure tactics designed to push its territorial claims, employing military aircraft, militia boats and sand dredgers to dominate access to disputed areas, U.S. government officials and regional experts say.

The confrontations fall short of outright military action without shots being fired, but Beijing’s aggressive moves are gradually altering the status quo, laying the foundation for China to potentially exert control over contested territory across vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean, the officials and experts say….

The Chinese are “trying to grind them down,” said a senior U.S. Defense official….

“Beijing never really presents you with a clear deadline with a reason to use force. You just find yourselves worn down and slowly pushed back,” [Gregory Poling of the Center for Strategic and International Studies] said.33

Some observers argue that China is using the period of the COVID-19 pandemic to further implement its salami-slicing strategy in the SCS while the world’s attention is focused on addressing the pandemic.34

***

29 See, for example, Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang, “China’s Art of Strategic Incrementalism in the South China Sea,” National Interest, August 8, 2020.

30 See, for example, Alan Dupont, “China’s Maritime Power Trip,” The Australian, May 24, 2014.

31 Jackson Diehl, “China’s ‘Creeping Invasion,” Washington Post, September 14, 2014.

32 The strategy has been called “talk and take” or “take and talk.” See, for example, Anders Corr, “China’s Take-And-Talk Strategy In The South China Sea,” Forbes, March 29, 2017. See also Namrata Goswami, “Can China Be Taken Seriously on its ‘Word’ to Negotiate Disputed Territory?” The Diplomat, August 18, 2017.

33 Dan De Luce, “China Tries to Wear Down Its Neighbors with Pressure Tactics,” NBC News, April 10, 2021. See also Dan Altman, “The Future of Conquest, Fights Over Small Places Could Spark the Next Big War,” Foreign Affairs, September 24, 2021.

34 See, for example, Tsukasa Hadano and Alex Fang, “China Steps Up Maritime Activity with Eye on Post-pandemic Order,” Nikkei Asian Review, May 13, 2020; Harsh Pant, “China’s Salami Slicing overdrive: It’s Flexing Military Muscles at a Time When Covid Preoccupies the Rest of the World,” Times of India, May 13, 2020; Veeramalla Anjaiah, “How To Tame Aggressive China In South China Sea Amid COVID-19 Crisis—OpEd,” Eurasia Review, May 14, 2020; Robert A. Manning and Patrick M. Cronin, “Under Cover of Pandemic, China Steps Up Brinkmanship in South China Sea,” Foreign Policy, May 14, 2020; Kathrin Hille and John Reed, “US Looks to Exploit Anger over Beijing’s South China Sea Ambitions,” Financial Times, May 3, 2020. Another observer, offering a somewhat different perspective, states

Recent developments in the South China Sea might lead one to assume that Beijing is taking advantage of the coronavirus crisis to further its ambitions in the disputed waterway. But it’s important to note that China has been following a long-term game plan in the sea for decades. While it’s possible that certain moves were made slightly earlier than planned because of the pandemic, they likely would have been made in any case, sooner or later.

(Steve Mollman, “China’s South China Sea Plan Unfolds Regardless of the Coronavirus,” Quartz, May 9, 2020.)

A May 3, 2020, press report stated

Analysts reject the idea that Beijing has embarked on a new South China Sea campaign during the pandemic. But they do believe the outbreak is having an effect on perceptions of Chinese policy.

“China is doing what it is always doing in the South China Sea, but it is a lot further along the road towards control than it was a few years ago,” said Gregory Poling, director of the Asia Maritime [CONTINUED…]

p. 11

Island Building and Base Construction

Perhaps more than any other set of actions, China’s island-building (aka land-reclamation) and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Paracel Islands and Spratly Islands in the SCS have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is rapidly gaining effective control of the SCS. China’s large-scale island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS appear to have begun around December 2013, and were publicly reported starting in May 2014. Awareness of, and concern about, the activities appears to have increased substantially following the posting of a February 2015 article showing a series of “before and after” satellite photographs of islands and reefs being changed by the work.35

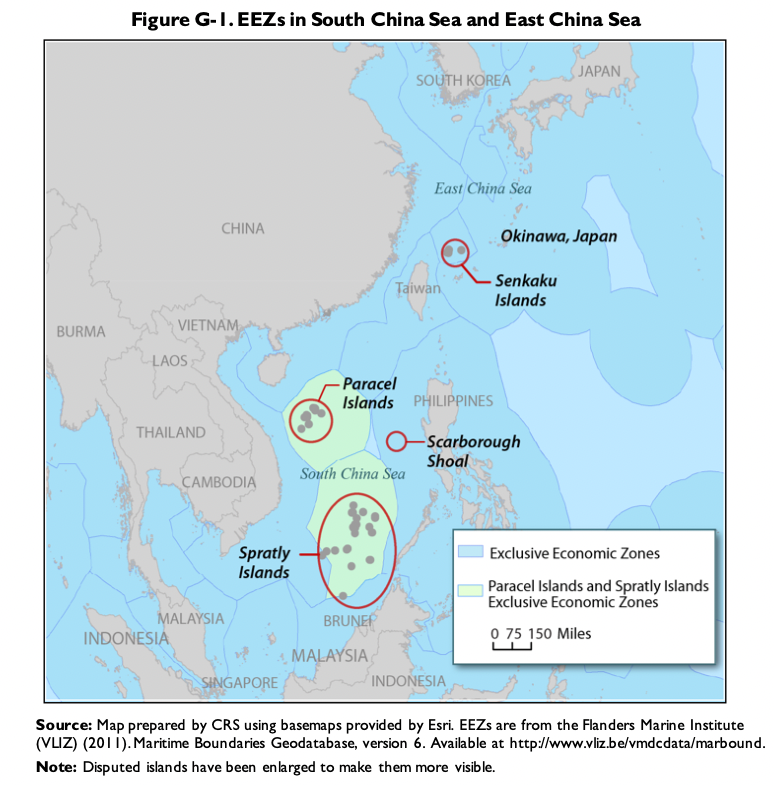

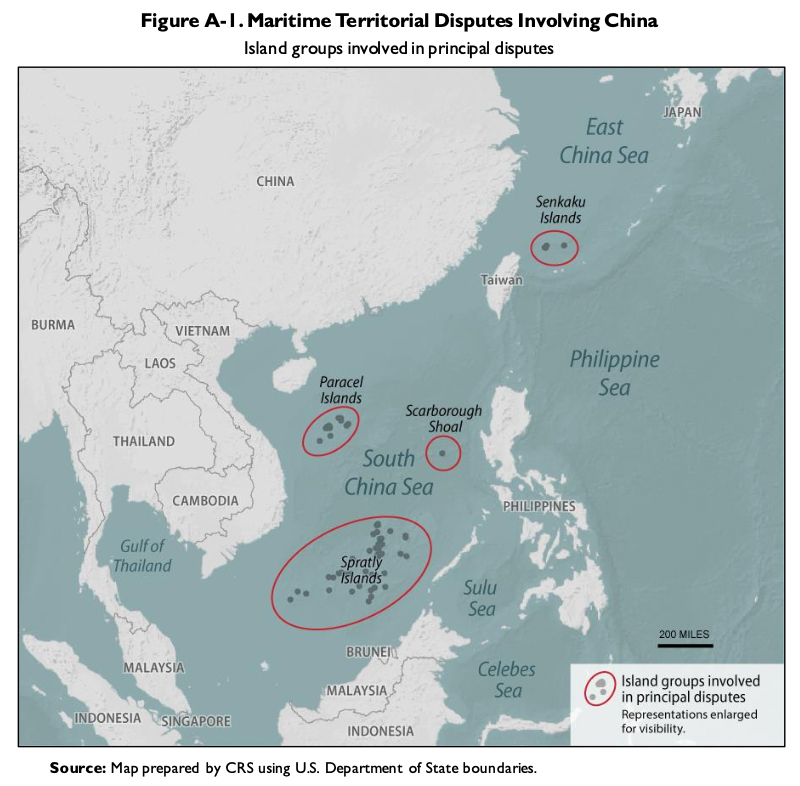

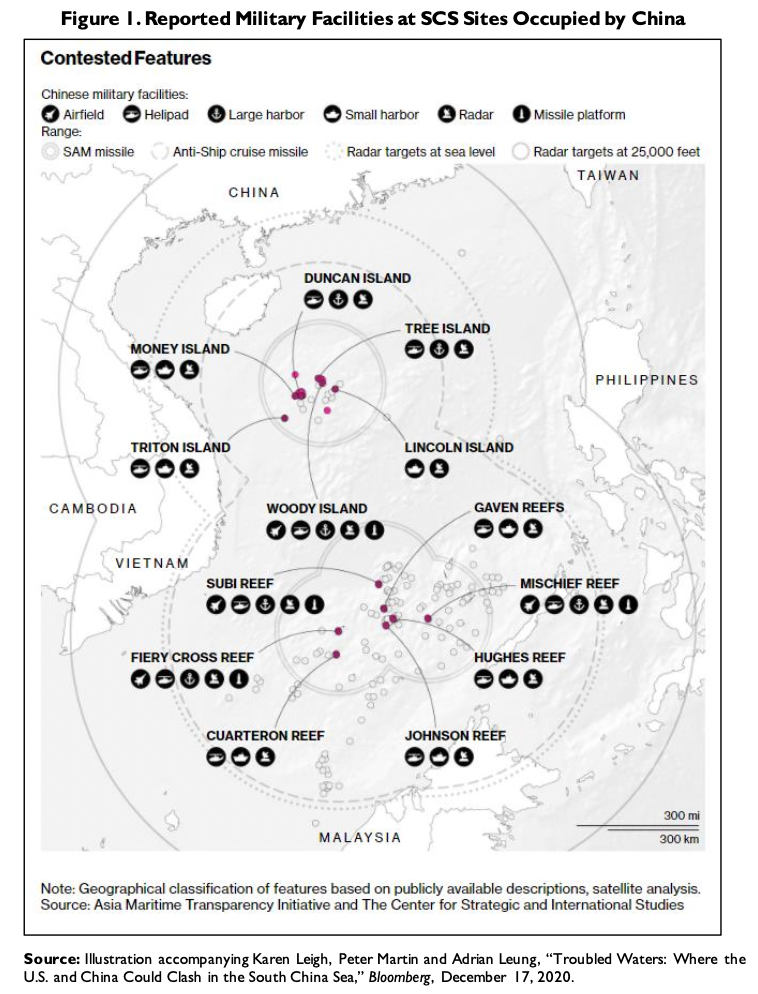

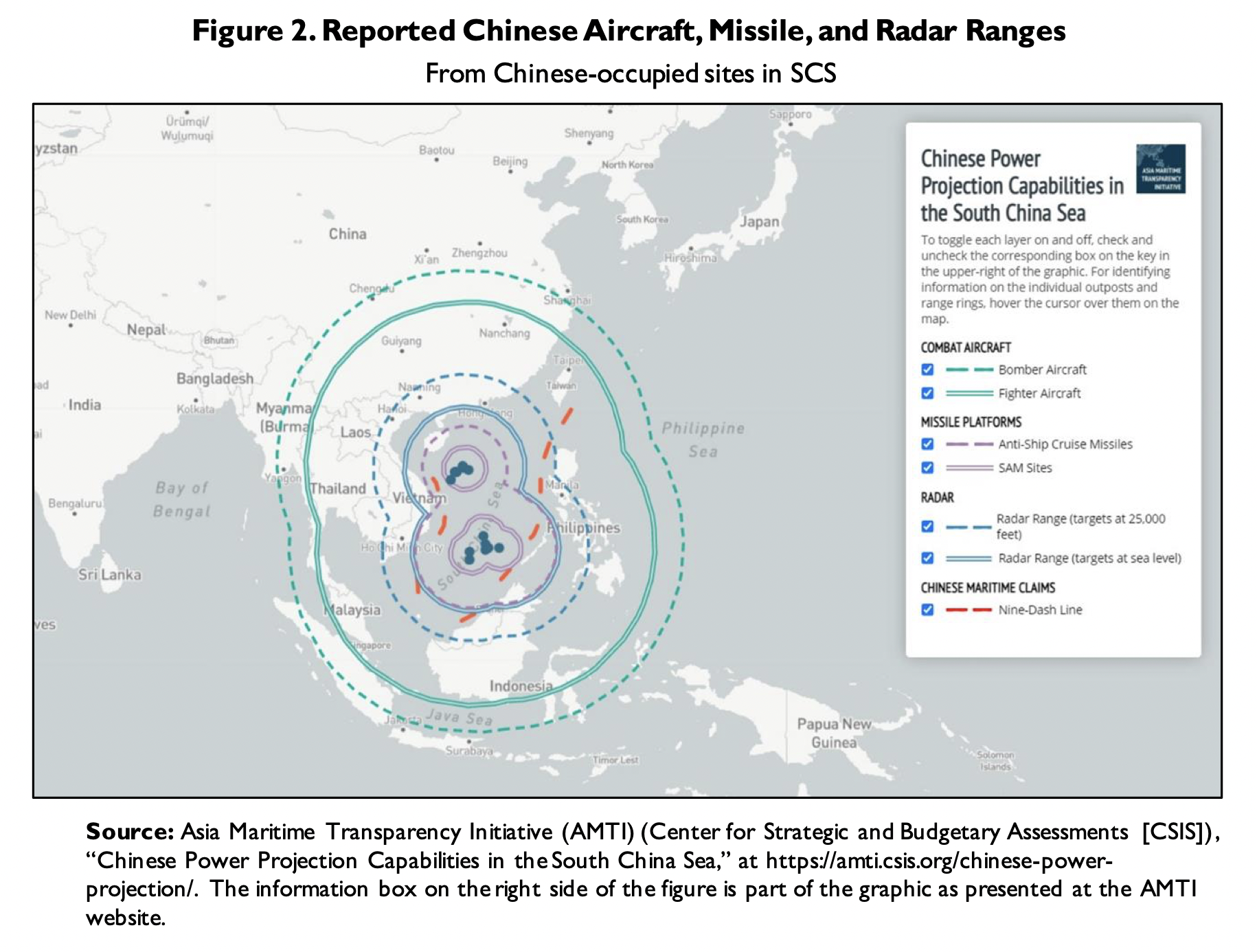

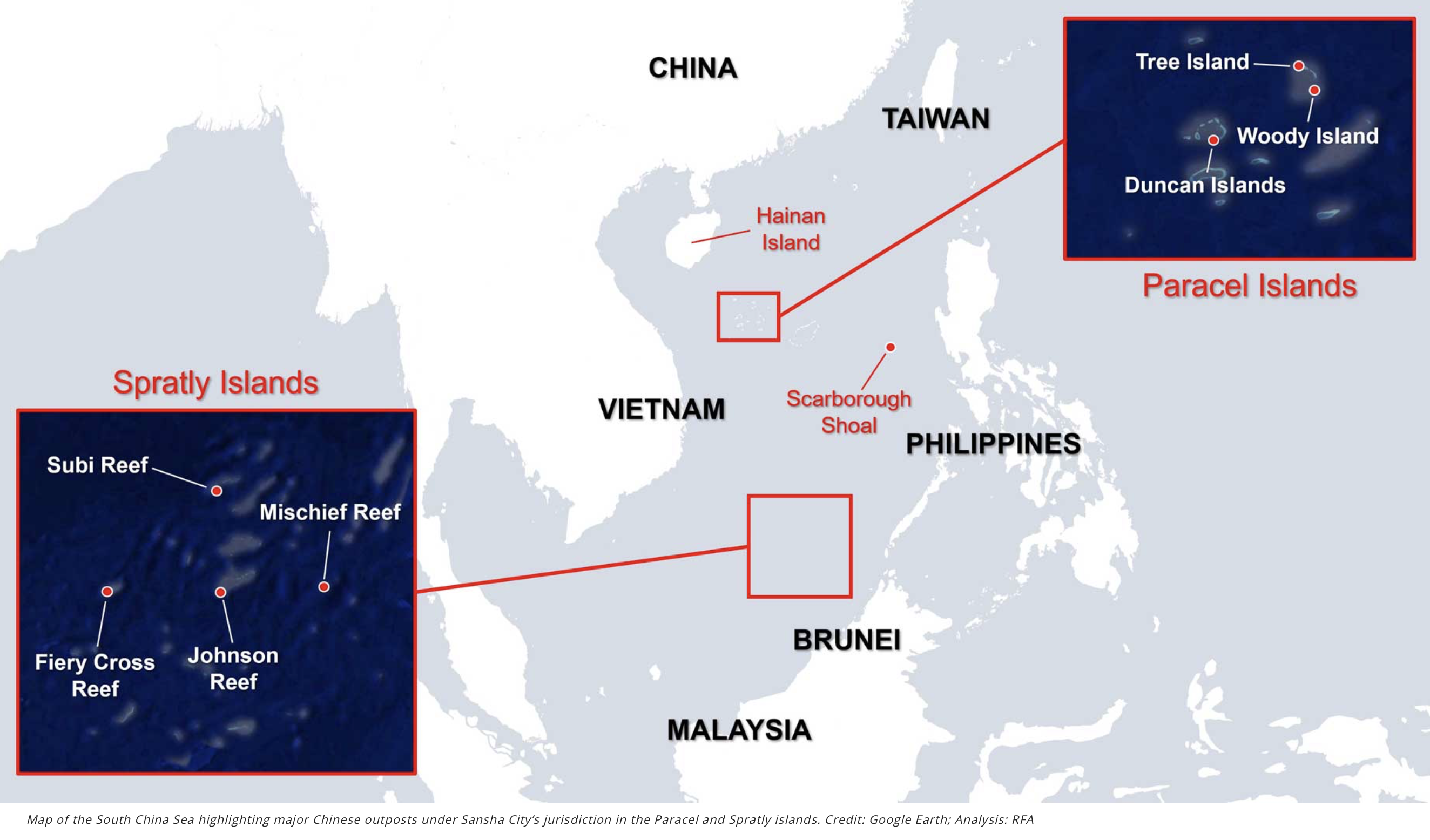

China occupies seven sites in the Spratly Islands. It has engaged in island-building and facilities-construction activities at most or all of these sites, and particularly at three of them—Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, and Mischief Reef, all of which now feature lengthy airfields as well as substantial numbers of buildings and other structures. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show reported military facilities at sites that China occupies in the SCS, and reported aircraft, missile, and radar ranges from those sites. Although other countries, such as Vietnam, have engaged in their own island-building and facilities-construction activities at sites that they occupy in the SCS, these efforts are dwarfed in size by China’s island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS.36

New Maritime Law That Went Into Effect on September 1, 2021

A new Chinese maritime law that China approved in April 2021 as an amendment to its 1983 maritime traffic safety law went into effect September 1, 2021. The law seeks to impose new notification and other requirements on foreign ships entering what China describes as “sea areas under the jurisdiction” of China.37 Some observers have stated that the new law could lead to increased tensions in the SCS, particularly if China takes actions to enforce its provisions.38 One observer—a professor of international law and the law of armed conflict at the Naval War College—states

China recently enacted amendments to its 1983 Maritime Traffic Safety Law, expanding its application from “coastal waters” to “sea areas under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China,” a term that is intentionally vague and not defined. Many of the

***

Transparency Initiative at CSIS, the Washington-based think-tank.

(Kathrin Hille and John Reed, “US Looks to Exploit Anger over Beijing’s South China Sea Ambitions,” Financial Times, May 3, 2020.)

35 Mira Rapp-Hooper, “Before and After: The South China Sea Transformed,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), February 18, 2015.

36 See, for example, “Vietnam’s Island Building: Double-Standard or Drop in the Bucket?,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), May 11, 2016. For additional details on China’s island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS, see, in addition to Appendix E, CRS Report R44072, Chinese Land Reclamation in the South China Sea: Implications and Policy Options, by Ben Dolven et al.

37 See, for example, Amber Wang, “South China Sea: China Demands Foreign Vessels Report before Entering ‘Its Territorial Waters,’” South China Morning Post, August 30, 2021.

38 See, for example, Navmi Krishna, “Explained: Why China’s New Maritime Law May Spike Tensions in South China Sea,” Indian Express, September 7, 2021; Brad Lendon and Steve George, “The Long Arm of China’s New Maritime Law Risks Causing Conflict with US and Japan,” CNN, September 3, 2021; Richard Javad Heydarian, “China’s Foreign Ship Law Stokes South China Sea Tensions,” Asia Times, September 2, 2021. See also James Holmes, “Are China And Russia Trying To Attack The Law Of The Sea?” 19FortyFive, August 31, 2021.

p. 12

amendments to the law exceed international law limits on coastal State jurisdiction that would illegally restrict freedom of navigation in the South China, East China, and Yellow Seas where China is embroiled in a number of disputed territorial and maritime claims with its neighbors. The provisions regarding the unilateral application of routing and reporting systems beyond the territorial sea violate UNCLOS. Similarly, application of the mandatory pilotage provisions to certain classes of vessels beyond the territorial sea is inconsistent with UNCLOS and IMO requirements. The amendments additionally impose illegal restrictions on the right of innocent passage in China’s territorial sea and impermissibly restrict the right of the international community to conduct hydrographic and military surveys beyond the territorial sea. China will use the amended law to engage in grey zone operations to intimidate its neighbors and further erode the rule of law at sea in the Indo-Pacific region.39

***

39 Online abstract for Raul (Pete) Pedrozo, “China’s Revised Maritime Traffic Safety Law,” International Law Studies (U.S. Naval War College), Vol. 97, 2021: 956-968. The online abstract is presented at Raul (Pete) Pedrozo, “China’s Revised Maritime Traffic Safety Law,” International Law Studies, U.S. Naval War College, posted June 16, 2021, at https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ils/vol97/iss1/39/. See also Nguyen Thanh Trung and Le Ngoc Khanh Ngan, “Codifying Waters and Reshaping Orders: China’s Strategy for Dominating the South China Sea,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), September 27, 2021.

p. 15

USE OF COAST GUARD SHIPS AND MARITIME MILITIA ………………………………………………………………………………………. 15

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

China asserts and defends its maritime claims not only with its navy, but also with its coast guard and its maritime militia. Indeed, China employs its maritime militia and its coast guard more regularly and extensively than its navy in its maritime sovereignty-assertion operations. DOD states that China’s navy, coast guard, and maritime militia together “form the largest maritime force in the Indo-Pacific.”44

Apparent Narrow Definition of “Freedom of Navigation”

China regularly states that it supports freedom of navigation and has not interfered with freedom of navigation. China, however, appears to hold a narrow definition of freedom of navigation that is centered on the ability of commercial cargo ships to pass through international waters. In contrast to the broader U.S./Western definition of freedom of navigation (aka freedom of the seas), the Chinese definition does not appear to include operations conducted by military ships and aircraft. It can also be noted that China has frequently interfered with commercial fishing operations by non-Chinese fishing vessels—something that some observers regard as a form of interfering with freedom of navigation for commercial ships.

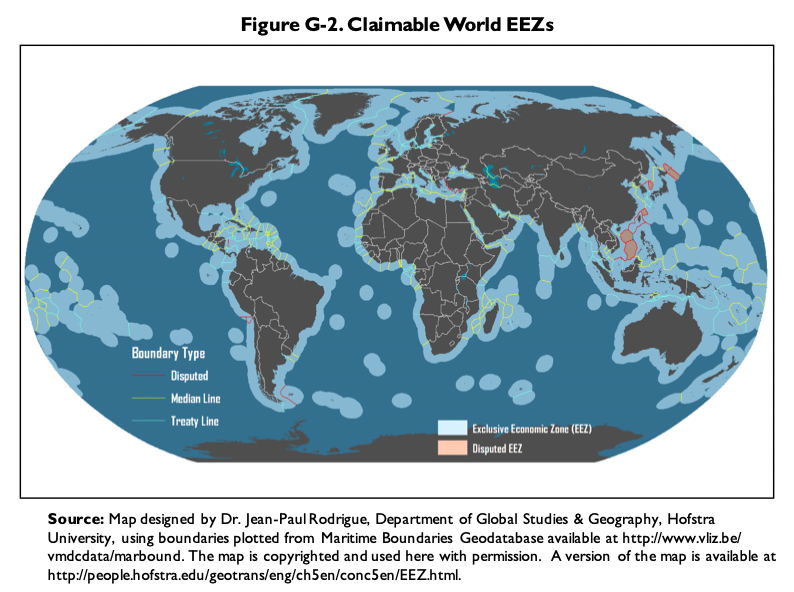

Position Regarding Regulation of Military Forces in EEZs

As mentioned earlier, the position of China and some other countries (i.e., a minority group among the world’s nations) is that UNCLOS gives coastal states the right to regulate not only economic activities, but also foreign military activities, in their EEZs.

Depiction of United States as Outsider Seeking to “Stir Up Trouble”

Along with its preference for treating territorial disputes on a bilateral rather than multilateral basis (see Appendix E for details), China resists and objects to U.S. involvement in maritime disputes in the SCS and ECS. Statements in China’s state-controlled media sometimes depict the United States as an outsider or interloper whose actions (including freedom of navigation operations) are meddling or seeking to “stir up trouble” (or words to that effect) in an otherwise peaceful regional situation. Potential or actual Japanese involvement in the SCS is sometimes depicted in China’s state-controlled media in similar terms. Depicting the United States in this manner can be viewed as consistent with goals of attempting to drive a wedge between the United States and its allies and partners in the region and of ensuring maximum leverage in bilateral (rather than multilateral) discussions with other countries in the region over maritime territorial disputes.

***

44 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2018, p. 16. See also Ryan D. Martinson, “Getting Synergized? PLAN-CCG Cooperation in the Maritime Gray Zone,” Asian Security, 2021 (posted online November 27, 2021); Andrew S. Erickson, “Maritime Numbers Game, Understanding and Responding to China’s Three Sea Forces,” Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, January 28, 2019.

p. 20

U.S. Statements in April and June 202052

An April 9, 2020, DOD statement stated

The Department of Defense is greatly concerned by reports of a China Coast Guard vessel’s collision with and sinking of a Vietnam fishing vessel in the vicinity of the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea.

The PRC’s behavior stands in contrast to the United States’ vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific region, in which all nations, large and small, are secure in their sovereignty, free from coercion, and able to pursue economic growth consistent with accepted international rules and norms. The United States will continue to support efforts by our allies and partners to ensure freedom of navigation and economic opportunity throughout the entire Indo-Pacific.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscores the importance of the rules based international order, as it sets the conditions that enable us to address this shared threat in a way that is transparent, focused, and effective. We call on all parties to refrain from actions that would

***

52 For examples of statements of the U.S. position other than those shown here, see Michael Pillsbury, ed., A Guide to the Trump Administration’s China Policy Statements, Hudson Institute, August 2020, 253 pp. Examples can be found in this publication by searching on terms such as “South China Sea,” East China Sea,” “freedom of navigation,” and “freedom of the seas.”

p. 21

destabilize the region, distract from the global response to the pandemic, or risk needlessly contributing to loss of life and property.53

In an April 22, 2020, statement, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated

Even as we fight the [COVID-19] outbreak, we must remember that the long-term threats to our shared security have not disappeared. In fact, they’ve become more prominent. Beijing has moved to take advantage of the distraction, from China’s new unilateral announcement of administrative districts over disputed islands and maritime areas in the South China Sea, its sinking of a Vietnamese fishing vessel earlier this month, and its “research stations” on Fiery Cross Reef and Subi Reef. The PRC continues to deploy maritime militia around the Spratly Islands and most recently, the PRC has dispatched a flotilla that included an energy survey vessel for the sole purpose of intimidating other claimants from engaging in offshore hydrocarbon development. It is important to highlight how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is exploiting the world’s focus on the COVID-19 crisis by continuing its provocative behavior. The CCP is exerting military pressure and coercing its neighbors in the SCS, even going so far as to sink a Vietnamese fishing vessel. The U.S. strongly opposes China’s bullying and we hope other nations will hold them to account too.54

***

53 Department of Defense, “China Coast Guard Sinking of a Vietnam Fishing Vessel,” April 9, 2020.

54 Department of State, “The United States and ASEAN are Partnering to Defeat COVID-19, Build Long-Term Resilience, and Support Economic Recovery,” Press Statement, Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State, April 22, 2020. See also A. Ananthalakshmi and Rozanna Latiff, “U.S. Says China Should Stop ‘Bullying Behaviour’ in South China Sea,” Reuters, April 18, 2020; Gordon Lubold and Dion Nissenbaum, “With Trump Facing Virus Crisis, U.S. Warns Rivals Not to Seek Advantage,” Wall Street Journal, April 20, 2020; Brad Lendon, “Coronavirus may be giving Beijing an opening in the South China Sea,” CNN, April 7, 2020; Agence France-Presse, “US Warns China Not to ‘Exploit’ Virus for Sea Disputes,” Channel News Asia, April 6, 2020.

p. 33

Specific Actions

Specific actions taken by the Trump Administration included the following, among others:

- As an apparent cost-imposing measure, DOD announced on May 23, 2018, that it was disinviting China from the 2018 RIMPAC (Rim of the Pacific) exercise.86

***

86 RIMPAC is a U.S.-led, multilateral naval exercise in the Pacific involving naval forces from more than two dozen countries that is held every two years. At DOD’s invitation, China participated in the 2014 and 2016 RIMPAC exercises. DOD had invited China to participate in the 2018 RIMPAC exercise, and China had accepted that invitation. DOD’s statement regarding the withdrawal of the invitation was reprinted in Megan Eckstein, “China Disinvited from [CONTINUED…]

p. 34

- In November 2018, national security adviser John Bolton said the U.S. would oppose any agreements between China and other claimants to the South China Sea that limit free passage to international shipping.87

- In January 2019, the then-U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral John Richardson, reportedly warned his Chinese counterpart that the U.S. Navy would treat China’s coast guard cutters and maritime militia vessels as combatants and respond to provocations by them in the same way as it would respond to provocations by Chinese navy ships.88

- On March 1, 2019, then-Secretary of State Michael Pompeo stated, “As the South China Sea is part of the Pacific, any armed attack on Philippine forces, aircraft, or public vessels in the South China Sea will trigger mutual defense obligations under Article 4 of our Mutual Defense Treaty [with the Philippines].”89 (For more on this treaty, see Appendix B.)

- As discussed earlier, on July 13, 2020, then-Secretary Pompeo issued a statement that strengthened, elaborated, and made more specific certain elements of the U.S. position regarding China’s actions in the SCS.

***

Participating in 2018 RIMPAC Exercise,” USNI News, May 23, 2018. See also Gordon Lubold and Jeremy Page, “U.S. Retracts Invitation to China to Participate in Military Exercise,” Wall Street Journal, May 23, 2018. See also Helene Cooper, “U.S. Disinvites China From Military Exercise Amid Rising Tensions,” New York Times, May 23, 2018; Missy Ryan, “Pentagon Disinvites China from Major Naval Exercise over South China Sea Buildup,” Washington Post, May 23, 2018; James Stavridis, “U.S. Was Right to Give China’s navy the Boot,” Bloomberg, August 2, 2018.

87 Jake Maxwell Watts, “Bolton Warns China Against Limiting Free Passage in South China Sea,” Wall Street Journal, November 13, 2018.

88 See Demetri Sevastopulo and Kathrin Hille, “US Warns China on Aggressive Acts by Fishing Boats and Coast Guard; Navy Chief Says Washington Will Use Military Rules of Engagement to Curb Provocative Behavior,” Financial Times, April 28, 2019. See also Shirley Tay, “US Reportedly Warns China Over Hostile Non-Naval Vessels in South China Sea,” CNBC, April 29, 2019; Ryan Pickrell, “China’s South China Sea Strategy Takes a Hit as the US Navy Threatens to Get Tough on Beijing’s Sea Forces,” Business Insider, April 29, 2019; Tyler Durden, “‘Warning Shot Across The Bow:’ US Warns China On Aggressive Acts By Maritime Militia,” Zero Hedge, April 29, 2019; Ankit Panda, “The US Navy’s Shifting View of China’s Coast Guard and ‘Maritime Militia,’” Diplomat, April 30, 2019; Ryan Pickrell, “It Looks Like the US Has Been Quietly Lowering the Threshold for Conflict in the South China Sea,” Business Insider, June 19, 2019.

89 State Department, Remarks With Philippine Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr., Remarks [by] Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State, March 1, 2019, accessed August 21, 2019 at https://www.state.gov/remarks-with-philippine-foreign-secretary-teodoro-locsin-jr/. See also James Kraska, “China’s Maritime Militia Vessels May Be Military Objectives During Armed Conflict,” Diplomat, July 7, 2020.

See also Regine Cabato and Shibani Mahtani, “Pompeo Promises Intervention If Philippines Is Attacked in South China Sea Amid Rising Chinese Militarization,” Washington Post, February 28, 2019; Claire Jiao and Nick Wadhams, “We Have Your Back in South China Sea, U.S. Assures Philippines,” Bloomberg, February 28 (updated March 1), 2019; Jake Maxwell Watts and Michael R. Gordon, “Pompeo Pledges to Defend Philippine Forces in South China Sea, Philippines Shelves Planned Review of Military Alliance After U.S. Assurances,” Wall Street Journal, March 1, 2019; Jim Gomez, “Pompeo: US to Make Sure China Can’t Blockade South China Sea,” Associated Press, March 1, 2019; Karen Lema and Neil Jerome Morales, “Pompeo Assures Philippines of U.S. Protection in Event of Sea Conflict, Reuters, March 1, 2019; Raissa Robles, “US Promises to Defend the Philippines from ‘Armed Attack’ in South China Sea, as Manila Mulls Review of Defence Treaty,” South China Morning Post, March 1, 2019; Raul Dancel, “US Will Defend Philippines in South China Sea: Pompeo,” Straits Times, March 2, 2019; Ankit Panda, “In Philippines, Pompeo Offers Major Alliance Assurance on South China Sea,” Diplomat, March 4, 2019; Mark Nevitt, “The US-Philippines Defense Treaty and the Pompeo Doctrine on South China Sea,” Just Security, March 11, 2019; Zack Cooper, “The U.S. Quietly Made a Big Splash about the South China Sea; Mike Pompeo Just Reaffirmed Washington Has Manila’s back,” Washington Post, March 19, 2019; Jim Gomez, “US Provides Missiles, Renews Pledge to Defend Philippines,” Associated Press, November 23, 2020; Karen Lema, “‘We’ve Got Your Back’—Trump Advisor Vows U.S. Support in South China Sea,” Reuters, November 23, 2020.

p. 35

- On August 26, 2020, then-Secretary Pompeo announced that the United States had begun “imposing visa restrictions on People’s Republic of China (PRC) individuals responsible for, or complicit in, either the large-scale reclamation, construction, or militarization of disputed outposts in the South China Sea, or the PRC’s use of coercion against Southeast Asian claimants to inhibit their access to offshore resources.”90

- On January 14, 2021, then-Secretary Pompeo announced additional sanctions against Chinese officials, including executives of state-owned enterprises and officials of the Chinese Communist Party and China’s navy “responsible for, or complicit in, either the large-scale reclamation, construction, or militarization of disputed outposts in the South China Sea, or the PRC’s use of coercion against Southeast Asian claimants to inhibit their access to offshore resources in the South China Sea.”91

- Also on January 14, 2021, the Commerce Department added China’s state-owned Chinese National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) to the Entity List, restricting exports to that firm, citing CNOOC’s role in “helping China intimidate neighbors in the South China Sea.”92

Biden Administration’s Strategy

Statements in 2021

A January 27, 2021, press report stated that

[President] Biden reaffirmed in a telephone call with the Japanese prime minister the U.S.’s commitment to defend uninhabited islands controlled by Japan and claimed by China that have been a persistent point of contention between the Asian powerhouses. Meanwhile, newly confirmed U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken rejected Chinese territorial claims

***

90 Department of State, “U.S. Imposes Restrictions on Certain PRC State-Owned Enterprises and Executives for Malign Activities in the South China Sea,” press statement, Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State, August 26, 2020. See also Susan Heavey, Daphne Psaledakis, and David Brunnstrom, “U.S. Targets Chinese Individuals, Companies amid South China Sea Dispute,” Reuters, August 26, 2020; Matthew Lee (Associated Press), “US Imposes Sanctions on Chinese Defense Firms over Maritime Dispute,” Defense News, August 26, 2020; Kate O’Keeffe and Chun Han Wong, “U.S. Sanctions Chinese Firms and Executives Active in Contested South China Sea,” Wall Street Journal, August 26, 2020; Ana Swanson, “U.S. Penalizes 24 Chinese Companies Over Role in South China Sea,” New York Times, August 26, 2020; Tal Axelrod, “US Restricting Travel of Individuals Over Beijing’s Moves in South China Sea,” The Hill, August 26, 2020; Jeanne Whalen, “U.S. Slaps Trade Sanctions on More Chinese Entities, This Time for South China Sea Island Building,” Washington Post, August 26, 2020; Gavin Bade, “U.S. Blacklists 24 Chinese Firms, Escalating Military and Trade Tensions,” Politico, August 26, 2020; Paul Handley, “US Blacklists Chinese Individuals, Firms For South China Sea Work,” Barron’s, August 26, 2020. See also Gregory Poling and Zack Cooper, “Washington Tries Pulling Economic Levers in the South China Sea,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), August 28, 2020; Hau Dinh and Yves Dam Van, “US to ASEAN: Reconsider Deals with Blacklisted China Firms,” Associated Press, September 10, 2020; Michael McDevitt, “Washington Takes a Stand in the South China Sea,” CNA (Arlington, VA), September 8, 2020.

91 Department of State, “Protecting and Preserving a Free and Open South China Sea,” January 14, 2021. See also Matthew Lee, “US Imposes New Sanction on Beijing over South China Sea,” Associated Press, January 14, 2021.

92 Department of Commerce, “Commerce Adds China National Offshore Oil Corporation to the Entity List and Skyrizon to the Military End-User List,” January 14, 2021. See also Ben Lefebvre, “U.S. Bans Exports to China’s State-Owned Oil Company CNOOC,” Politico Pro, January 14, 2021.

p. 36

in a call with his Philippine counterpart and emphasized U.S. alliances in talks with top Australian and Thai officials.93

A January 28, 2021, press report similarly stated

One week into the job, US President Joe Biden has sent a clear warning to Beijing against any expansionist intentions in East and Southeast Asia.

In multiple calls and statements, he and his top security officials have underscored support for allies Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines, signaling Washington’s rejection of China’s disputed territorial claims in those areas.

On Wednesday [January 27], Biden told Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga that his administration is committed to defending Japan, including the Senkaku Islands, which are claimed both by Japan and China, which calls them the Diaoyu Islands.

That stance was echoed by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, who told Japanese counterpart Nobuo Kishi on Saturday that the contested islands were covered by the US-Japan Security Treaty.

Austin affirmed that the United States “remains opposed to any unilateral attempts to change the status quo in the East China Sea,” according to a Pentagon statement on the call. expansionist intentions in East and Southeast Asia.94

Regarding the above-mentioned call between Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs Locsin, a January 27, 2021, State Department statement stated that in the call, Blinken

reaffirmed that a strong U.S.-Philippine Alliance is vital to a free and open Indo-Pacific region. Secretary Blinken stressed the importance of the Mutual Defense Treaty for the security of both nations, and its clear application to armed attacks against the Philippine armed forces, public vessels, or aircraft in the Pacific, which includes the South China Sea. Secretary Blinken also underscored that the United States rejects China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea to the extent they exceed the maritime zones that China is permitted to claim under international law as reflected in the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention. Secretary Blinken pledged to stand with Southeast Asian claimants in the face of PRC pressure.95

A January 22, 2021, press report stated

Washington’s defense treaty with Tokyo applies to the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands, the new U.S. national security adviser confirmed Thursday [January 21], in an early show of support for an ally regarding a source of regional tension.

In a 30-minute phone call that marked the first official contact between high-level officials from the two countries since U.S. President Joe Biden took office Wednesday, Jake

***

93 Isabel Reynolds, “Biden Team Slams China Claims in Swift Calls to Asia Allies,” Bloomberg, January 27 (updated January 28), 2021.

94 Sylvie Lanteaume (Agence France-Presse), “In Multiple Messages, Biden Warns Beijing over Expansionism,” Yahoo News, January 28, 2021. See also Wendy Wu and Teddy Ng, “China-US Tension: Biden Administration Pledges to Back Japan and Philippines in Maritime Disputes,” South China Morning Post, January 28, 2021.

95 Department of State, “Secretary Blinken’s Call with Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs Locsin,” January 27, 2021. See also Mohammad Zargham and Karen Lema, “U.S. Stands with SE Asian Countries Against China Pressure, Blinken Says,” Reuters, January 27 (updated January 28), 2021; Sebastian Strangio, “Biden Administration Reaches out to Southeast Asian Allies,” Diplomat, January 28, 2021; Ken Moriyasu, “US Vows to Defend Philippines, Including in South China Sea,” Nikkei Asia, January 29, 2021; Frances Mangosing, “New Pentagon Chief Commits Support for PH in South China Sea,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 10, 2021.

p. 37

Sullivan and Japanese counterpart Shigeru Kitamura reaffirmed the importance of the alliance.

Sullivan said the U.S. opposes any unilateral actions intended to harm Japan’s administration of the Senkakus—which are claimed by China as the Diaoyu—and is committed to its obligations under the treaty, according to the Japanese government’s readout. The call was requested by Tokyo.96

As noted earlier, on February 19, 2021, the State Department stated that

we reaffirm the [earlier-cited] statement of July 13th, 2020 [by then-Secretary of State Pompeo] regarding China’s unlawful and excessive maritime claims in the South China Sea. Our position on the PRC’s maritime claims remains aligned with the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal’s finding that China has no lawful claim in areas it found to be in the Philippines exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

We also reject any PRC claim to waters beyond the 12 nautical mile territorial sea from islands it claims in the Spratlys. China’s harassment in these areas of other claimants, state hydrocarbon exploration or fishing activity, or unilateral exploitation of those maritime resources is unlawful.97

A February 24, 2021, press report stated

The Pentagon has urged Beijing to stop sending government vessels into Japanese waters, following more incursions by China’s coast guard vessels near the Senkaku Islands over the weekend.

Beijing’s continued deployment of ships near the islets controlled by Japan “could lead to miscalculation”—or physical and material harm, Department of Defense spokesperson John Kirby said Tuesday [February 23]….

Nations should be “free from coercion and able to pursue economic growth consistent with accepted rules and norms,” Pentagon press secretary John Kirby told reporters during Tuesday’s off-camera briefing.

He said the Chinese government, through its actions, was undermining the rules-based international order, one in which Beijing itself has benefited.

“We would urge the Chinese to avoid actions, using their Coast Guard vessels, that could lead to miscalculation and potential physical, if not—and material harm,” Kirby said, according to a DoD read-out.98

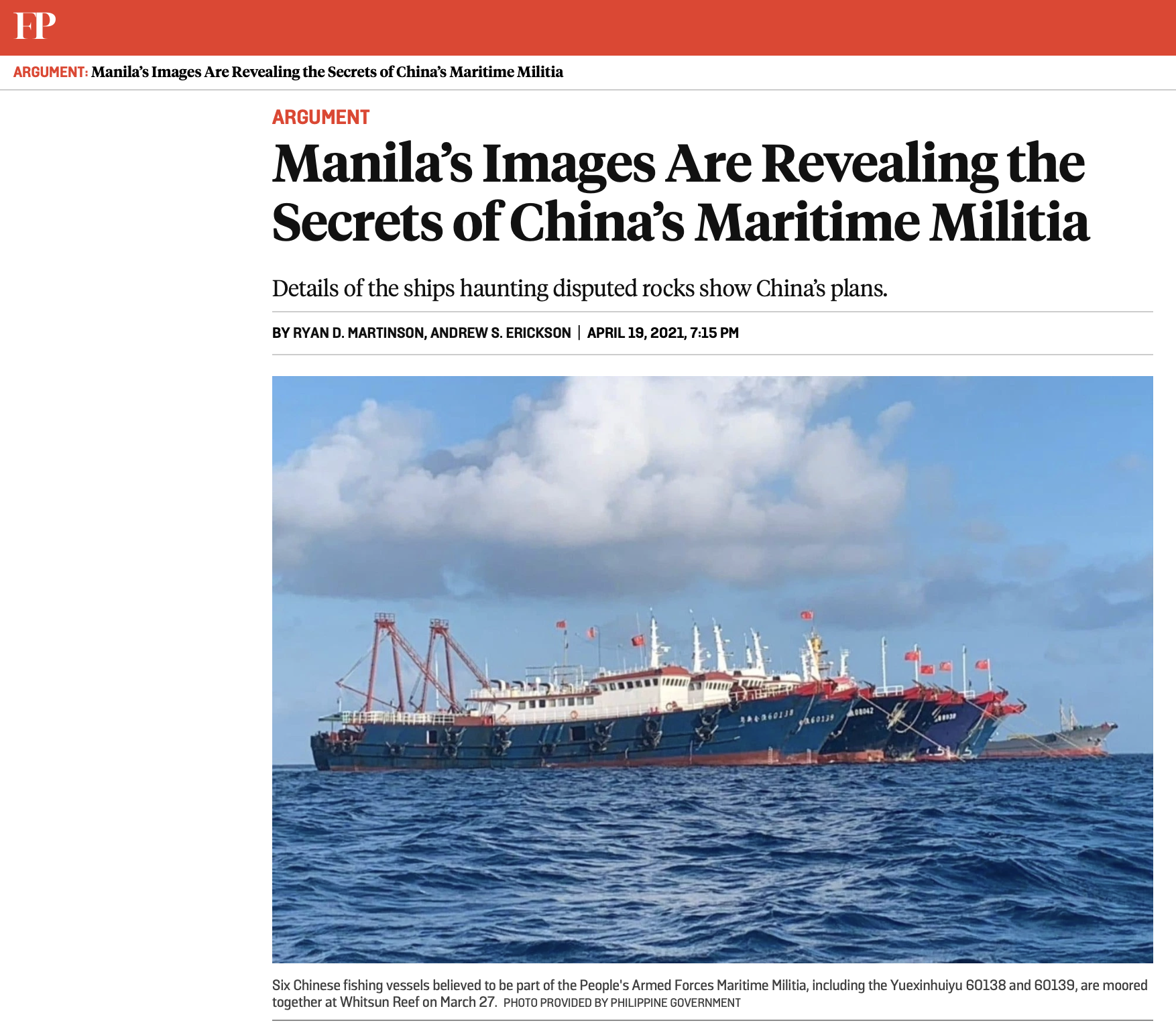

On March 16, 2021, following a U.S.-Japan “2+2” ministerial meeting that day in Tokyo between Secretary of State Blinken, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi, and Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi, the U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee released a U.S.-Japan joint statement for the press that stated in part: