The China Maritime Militia Bookshelf: Latest U.S. Gov’t Docs, SECNAV Guidance, Official Video—& More!

Andrew S. Erickson, “Tracking China’s ‘Little Blue Men’—A Comprehensive Maritime Militia Compendium,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 17 January 2024.

American & Allied knowledge of the PRC’s Third Sea Force has come a long way since my outstanding Naval War College colleague Professor Conor Kennedy & I began our focused research following his arrival in Newport in 2014. Now top U.S. officials, including the Secretary of the Navy & the Vice President, have highlighted China’s Maritime Militia in their official statements… You can read their words, other data & analysis, and findings from specialists here! A great research pioneer and public intellectual who is now an Assistant Professor at the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI), Conor has the first three citations in the latest Wikipedia entry among many other positive impacts…

This Bookshelf compilation is updated with the latest U.S. Government documents, guidance from SECNAV Carlos Del Toro, entry in Wikipedia & music video from the PAFMM’s very own Sansha Garrison! It includes everything from the very newest sources… to some of my earliest findings with colleagues at CMSI, dating back to 2009—when we uncovered PRC Militia forces’ role in mine warfare (MIW). For an overview, you can watch my best single PAFMM presentation, now available on YouTube.

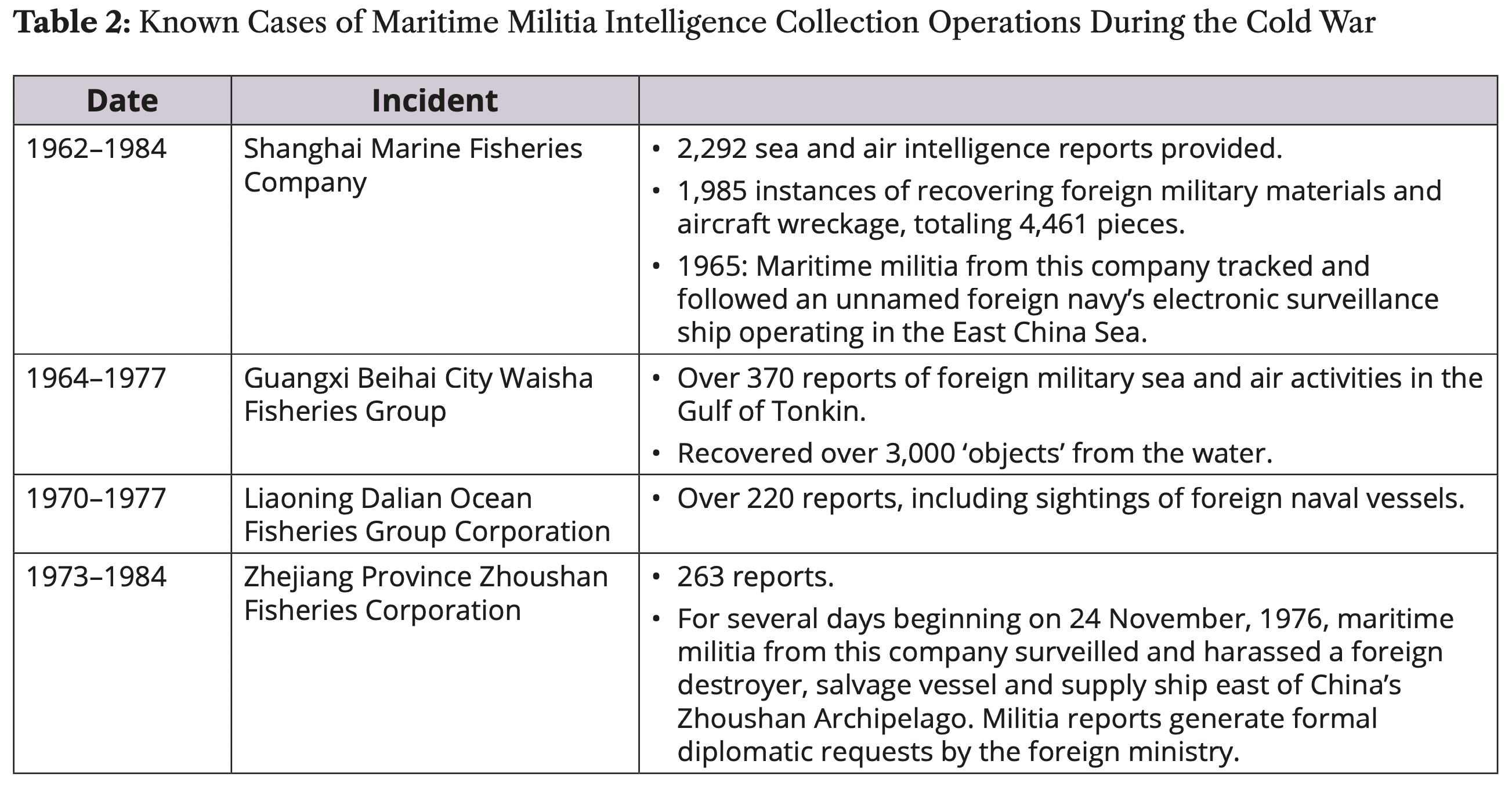

As I told the Defense Forum Foundation in 2009, “China holds exercises that involve the Maritime Militia—with civilian fishing vessels—training in the laying of mines; GPS could leverage that considerably.” Here I drew on extensive research with other CMSI colleagues, published in China Maritime Study #3 (June 2009). We included multiple sections on PRC operational concepts and training to employ Maritime Militia forces and fishing vessels in MIW. Having long noticed references to China’s Maritime Militia dating back to at least the early 2000s in the PLA Navy (PLAN)’s official newspaper, People’s Navy (人民海军), I read and cited key articles therein.

Since Beijing remains far from being fully forthcoming and transparent, I hope that governments whose nations’ ships have been involved in incidents with Maritime Militia vessels—as well as any other knowledgeable parties—will release complete information on exactly what has happened. Meanwhile, however, ample information is already available concerning China’s People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) and the important role it has played in these waters for decades. And it’s all here, in keyword-searchable format! Folks outside government looking for a way to enhance public understanding may wish to update and enhance Wikipedia’s entries on “Maritime Militia (China)” (now in English, Chinese, Japanese, and Czech)—all of which remain far from comprehensive or complete. It’s easy to become a Wikipedia editor, by the platform’s very design…

Rarely is a topic so little recognized and so little understood (even now), yet so important and so amenable to research using Chinese-language open sources. To increase awareness and understanding of this important subject, I will keep updating this compendium of major publications and other documents available on the matter. If you know of others, please kindly bring them to my attention via <http://www.andrewerickson.com/contact/>.

CHINA’S MARITIME MILITIA: DATA & ANALYSIS

“Maritime Militia (China),” Wikipedia, entry as of 16 January 2024.

Maritime Militia (China)

| China’s Maritime Militia | |

|---|---|

| 中国海上民兵 | |

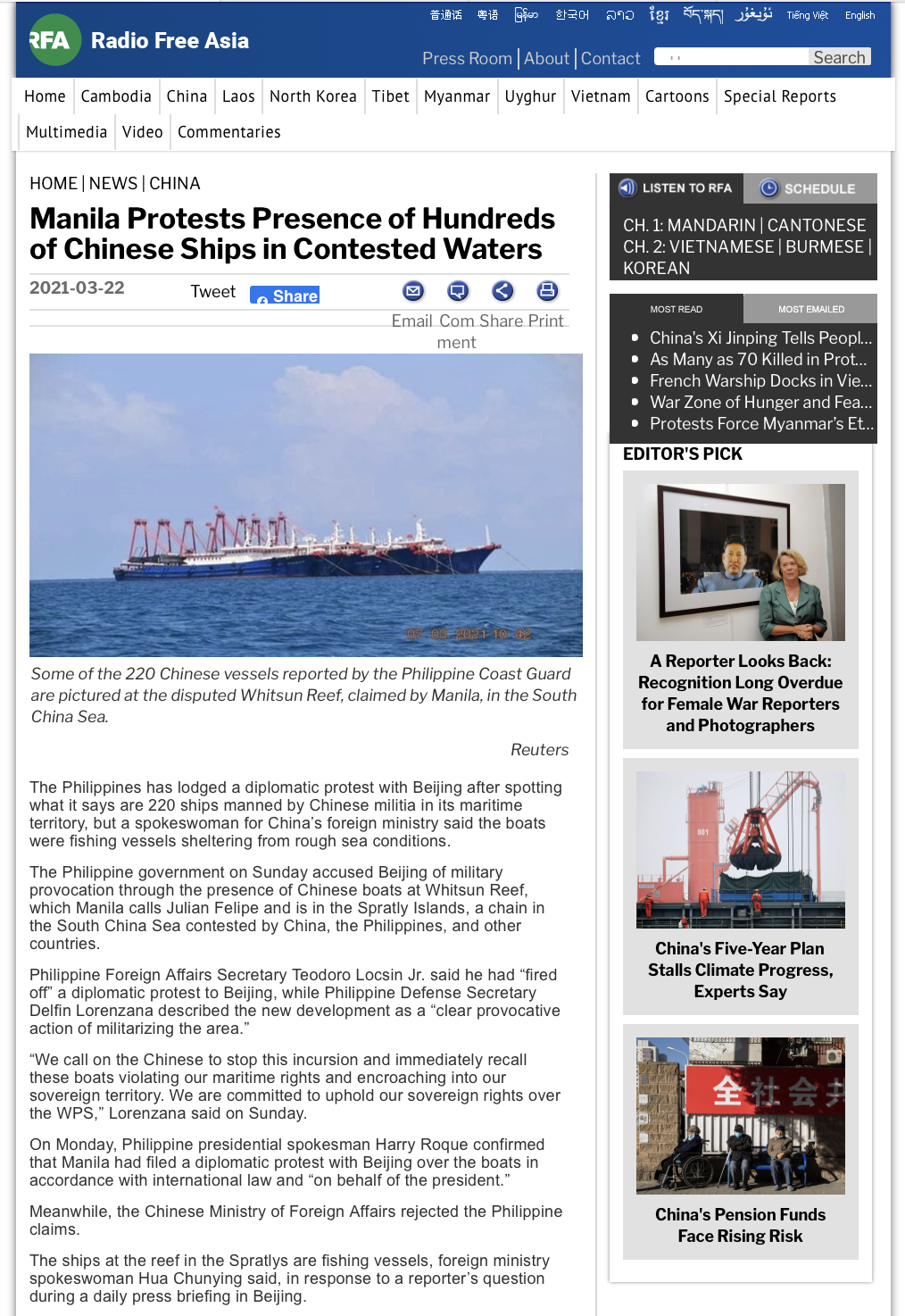

Chinese paramilitary trawler 00001 a Philippines boat resupplying Spratlys.[1]

|

|

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Maritime militia |

| Role | Naval patrols, reconnaissance, search and rescue; greyzone warfare |

| Fleet | 370,000 non-powered FVs (2015)[2] 672,000 powered FVs (2015)[2] |

| Engagements | |

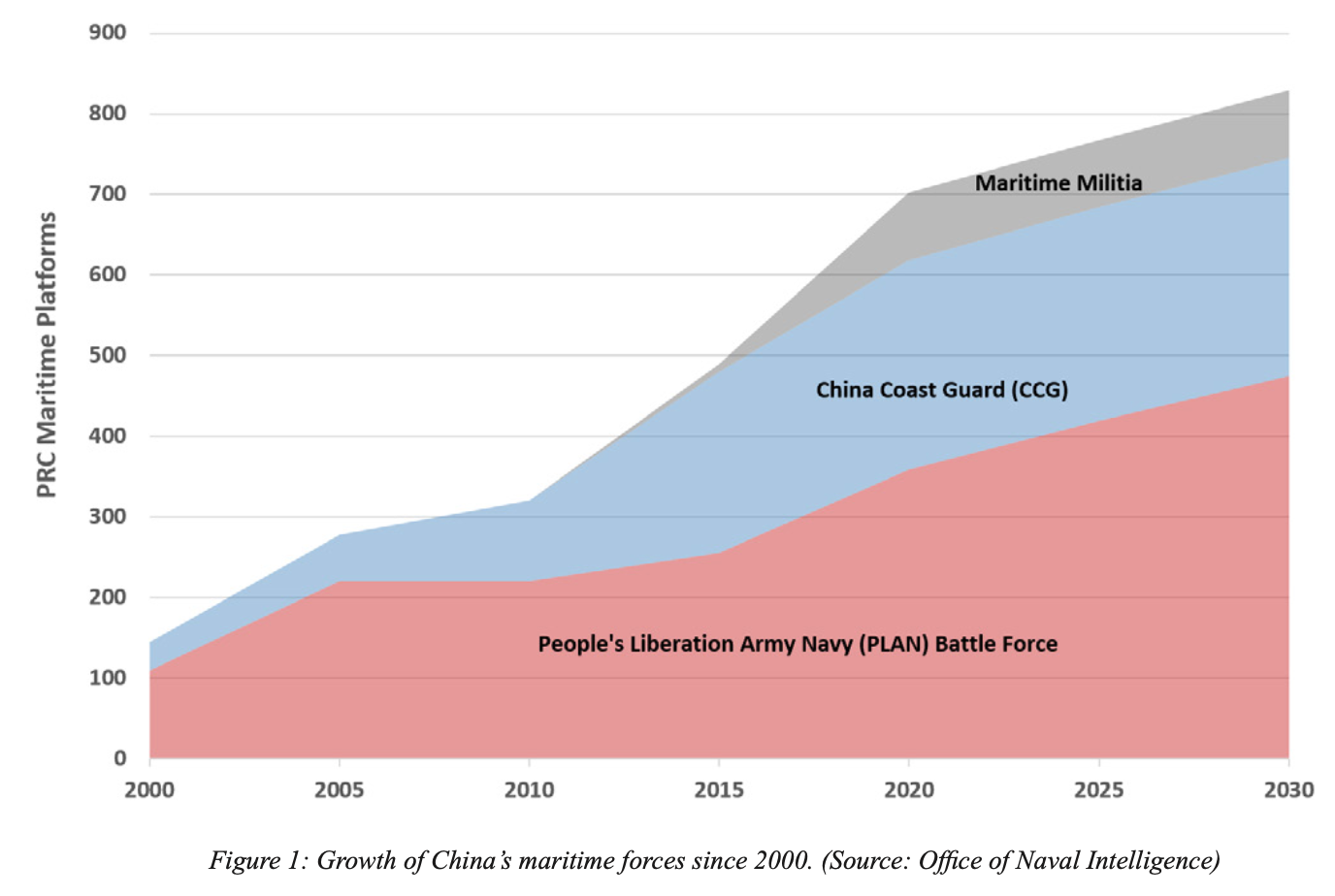

The Maritime Militia, also called the Fishing Militia (Chinese: 中国海上民兵), is one of the three forces, next to the China Coast Guard (CCG) and the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), used in maritime operations by the People’s Republic of China (PRC).[3]

As of 2022, the PRC and Vietnam were the only nations worldwide that had officially established a legal regime for their maritime militia.[4]

Name

The US Military refers to the Maritime Militia as the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM).[5]

For reportedly operating in the South China Sea without clear identification, they are sometimes referred to as the “little blue men“, a term coined by Andrew S. Erickson of the Naval War College, in reference to Russia’s “little green men” during its 2014 annexation of Crimea.[6]

History

China’s maritime militia was established after the Chinese Communist Party(CCP) won the Chinese Civil War and forced the Kuomintang (KMT) to flee the mainland to Taiwan. The newly consolidated communist government needed to augment their maritime defenses against the nationalist forces, which had retreated offshore and remained entrenched on a number of coastal islands. Therefore, the concept of people’s war was applied to the sea with fishermen and other nautical laborers being drafted into a maritime militia. The nationalists had maintained a maritime militia during their time in power, but the communist government preferred to craft theirs anew given their suspicion of organizations created by the nationalists. The CCP also instituted a national-level maritime militia command to unite the local militias, something the KMT had never done. In the early 1950s, the Bureau of Aquatic Products played a key role in institutionalizing and strengthening the maritime militia as it collectivized local fisheries. Bureau of Aquatic Products leaders were also generally former high-ranking PLAN officers which lead to close relations between the organizations. The formation of the maritime militia was influenced by the Soviet “Young School” of military theory, which emphasized coastal defense over naval power projection for nascent communist powers.[5]

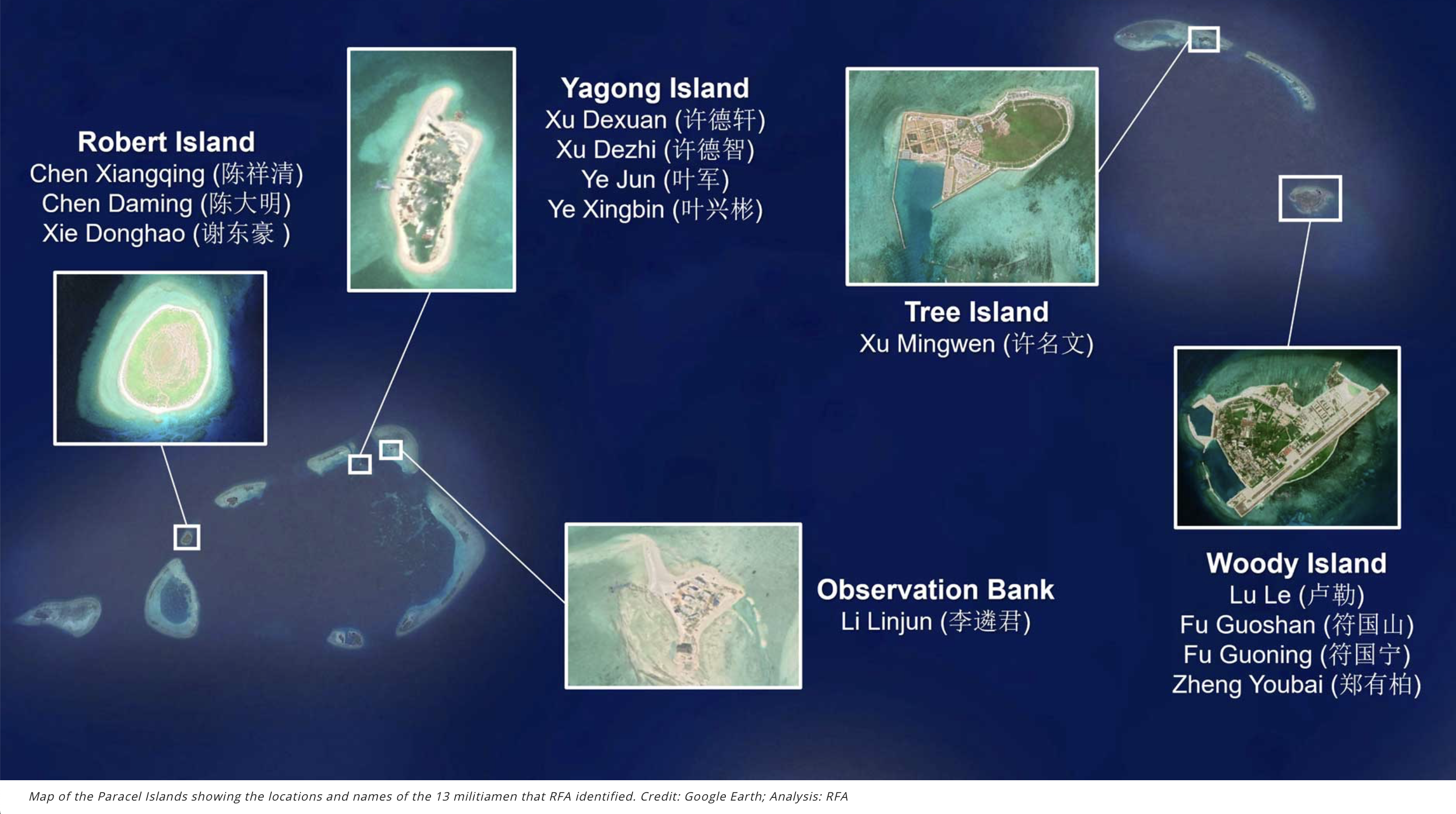

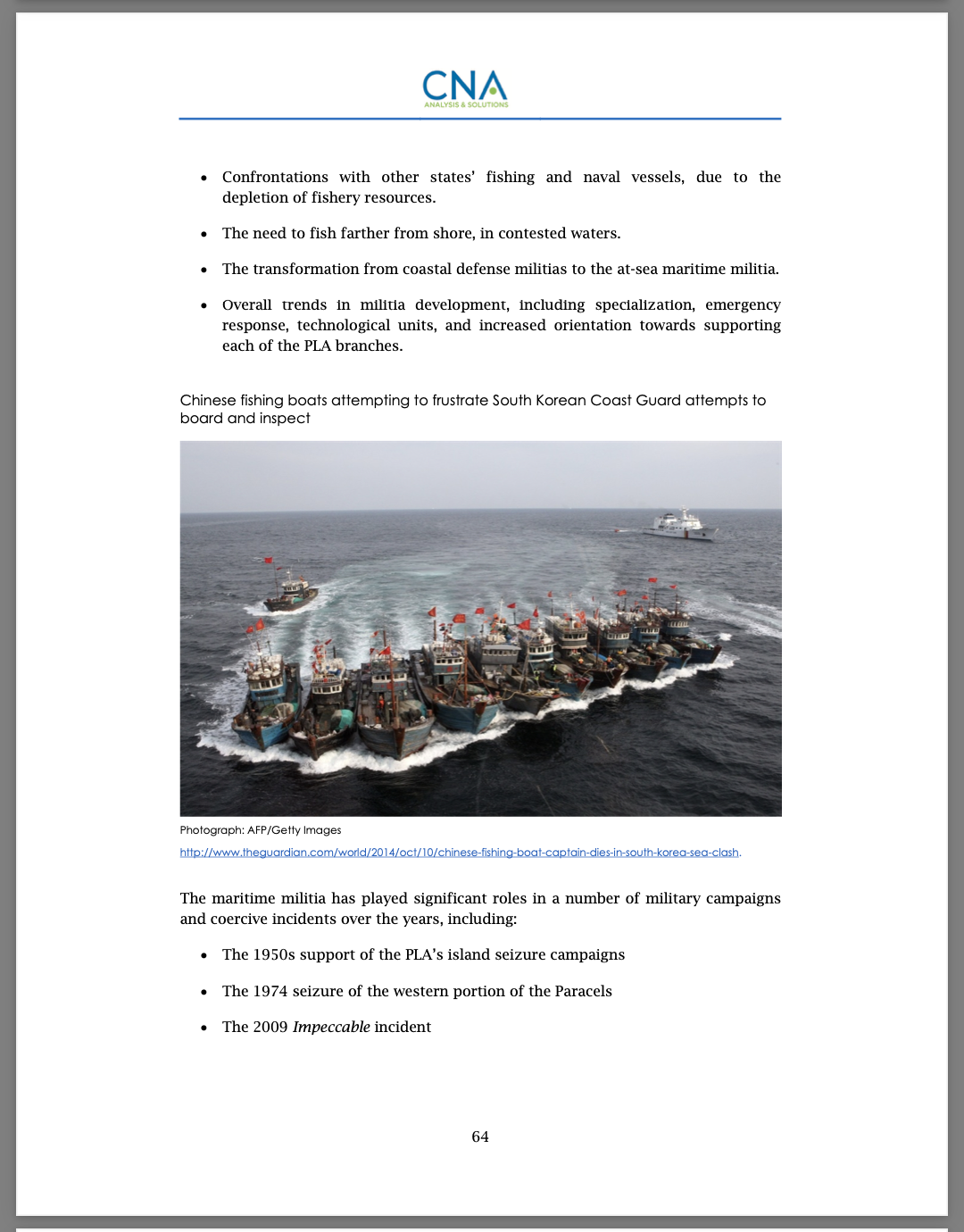

In the 1960s and 1970s, the PLAN established maritime militia schools near the three main fleet headquarters of Qingdao, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.[5] Through the first half of the 1970s, the maritime militia mostly stayed near shore and close to China. However, by the later 1970s, the maritime militia had evolved an important sovereignty support function which brought it into increasing conflict with China’s neighbors, especially in the South China Sea. The maritime militia contributed significantly to the Battle of the Paracel Islands, especially in providing amphibious lift capacity to Chinese forces.[5]

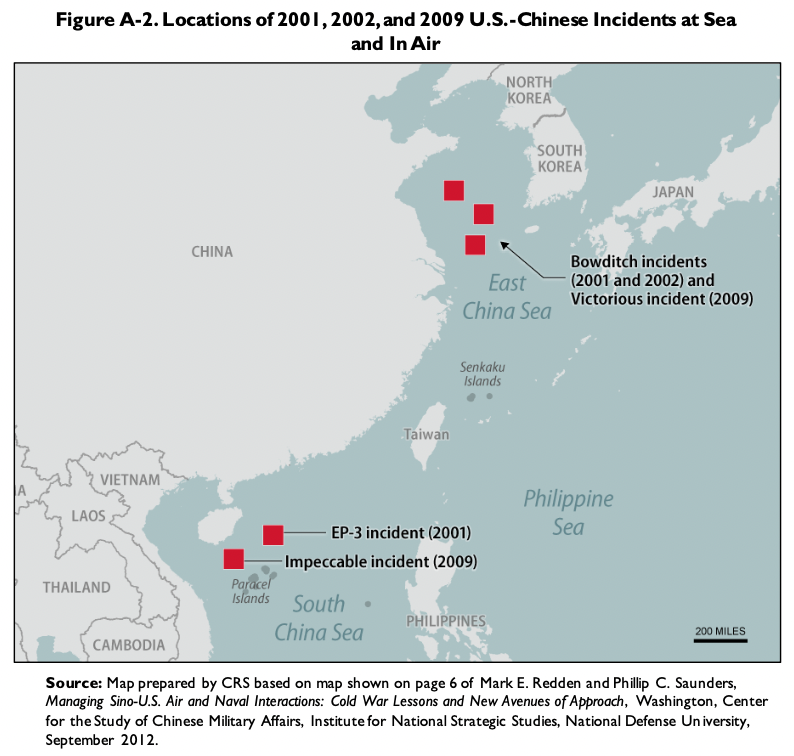

In the 2000s, the involvement of the maritime militia in more aggressive operations, namely, the physical interference with the navigation of Navy ships by the US, increased.[7]

China’s fishing fleet was being downsized until 2008, when maritime militia funding lead instead to an expansion. This expansion has led to an increase in illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.[2]

In 2019, the United States issued a warning to China over aggressive and unsafe action by their Coast Guard and maritime militia.[8]

The maritime militia is believed to be behind a number of incidents in the South China Sea where high powered lasers were pointed at the cockpits of aircraft. This includes an attack against a Royal Australian Navy helicopter.[9]

In 2022, satellite images showed that more than a hundred militia vessels operated in the South China Sea on a daily basis. The number of vessels peaked in July 2022, when around 400 militia vessels were deployed in the South China Sea. The movement and the observed behavior of the militia vessels remained consistent over the years.[10]

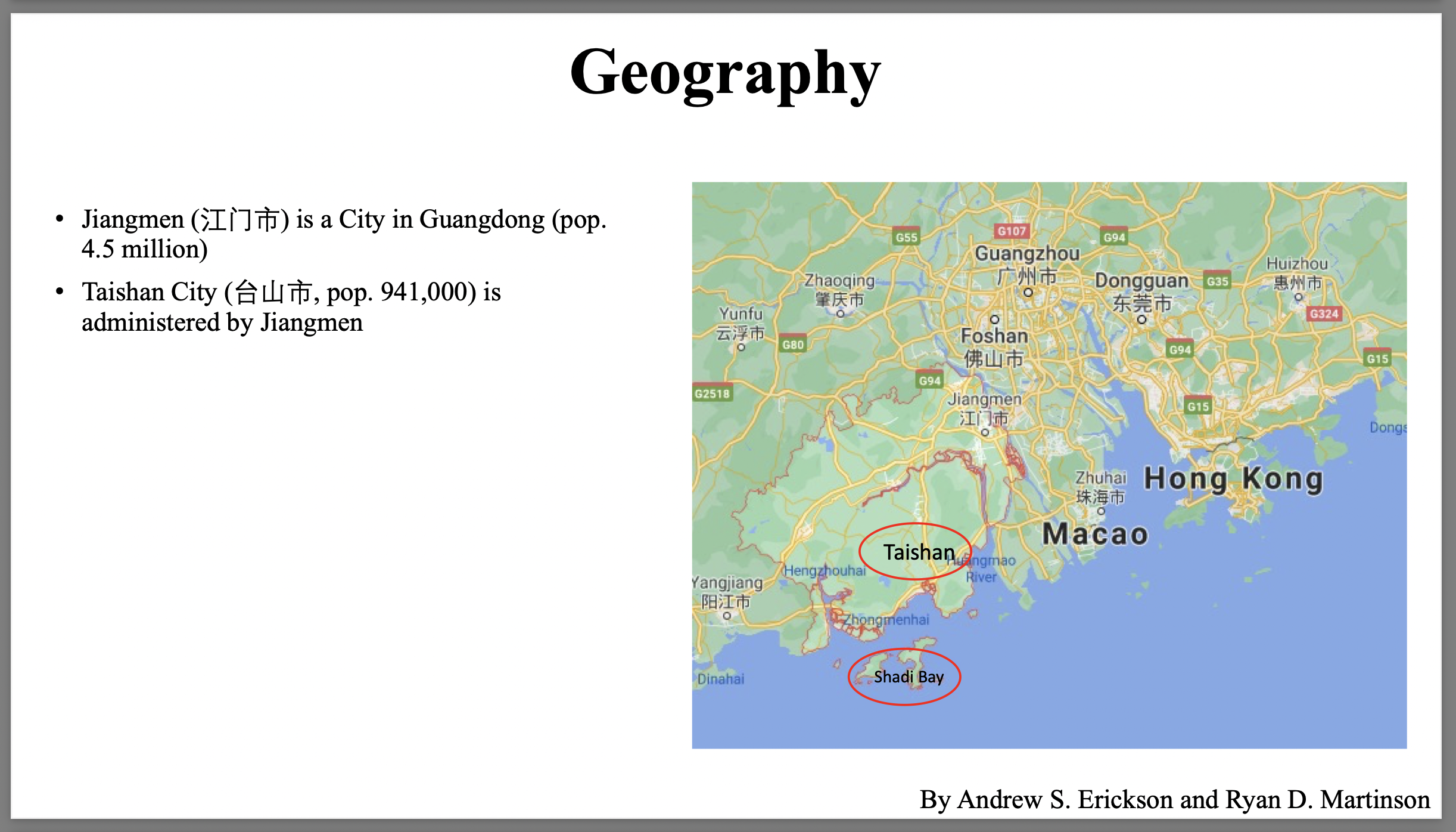

Structure and Characteristics

China’s fishing militia consists of a mixture of purpose-built maritime militia fishing vessels (MMFV) as well as normal fishing boats, called Spratly Backbone Fishing Vessels (SBFVs), which get recruited by the central government via various subsidy programs.[7]Most of the boats are between 45 and 65 meters long.[10] A vast majority of the fleet is owned by natural persons, and not the government itself.[7] This means, a large part of the armed mass organization is made up of civilians, who still maintain regular jobs in the marine economy, while being part of the militia. Although the militia is independent from the PLAN and the CCG, it is trained by both.[11] The maritime militia operates from mainly ten ports within the Guangdong and Hainan Provinces of China.[7]

Capabilities

The Maritime Militia has utilized both rented fishing vessels and purpose-built ships in its operations.[12]

Although the maritime militia is part of the armed forces of the PRC, in 2018 it was usually unarmed.[3] The violence used by the militia is mostly limited to dangerous maneuvers and, on occasion, the ramming or shouldering of other vessels. Professional militia vessels can be equipped with large water cannons.[7] Most vessels are issued with navigation and communication equipment while some are also issued small arms.[13][14] Some Maritime Militia units are equipped with naval mines and anti-aircraft weapons.[15] [16]

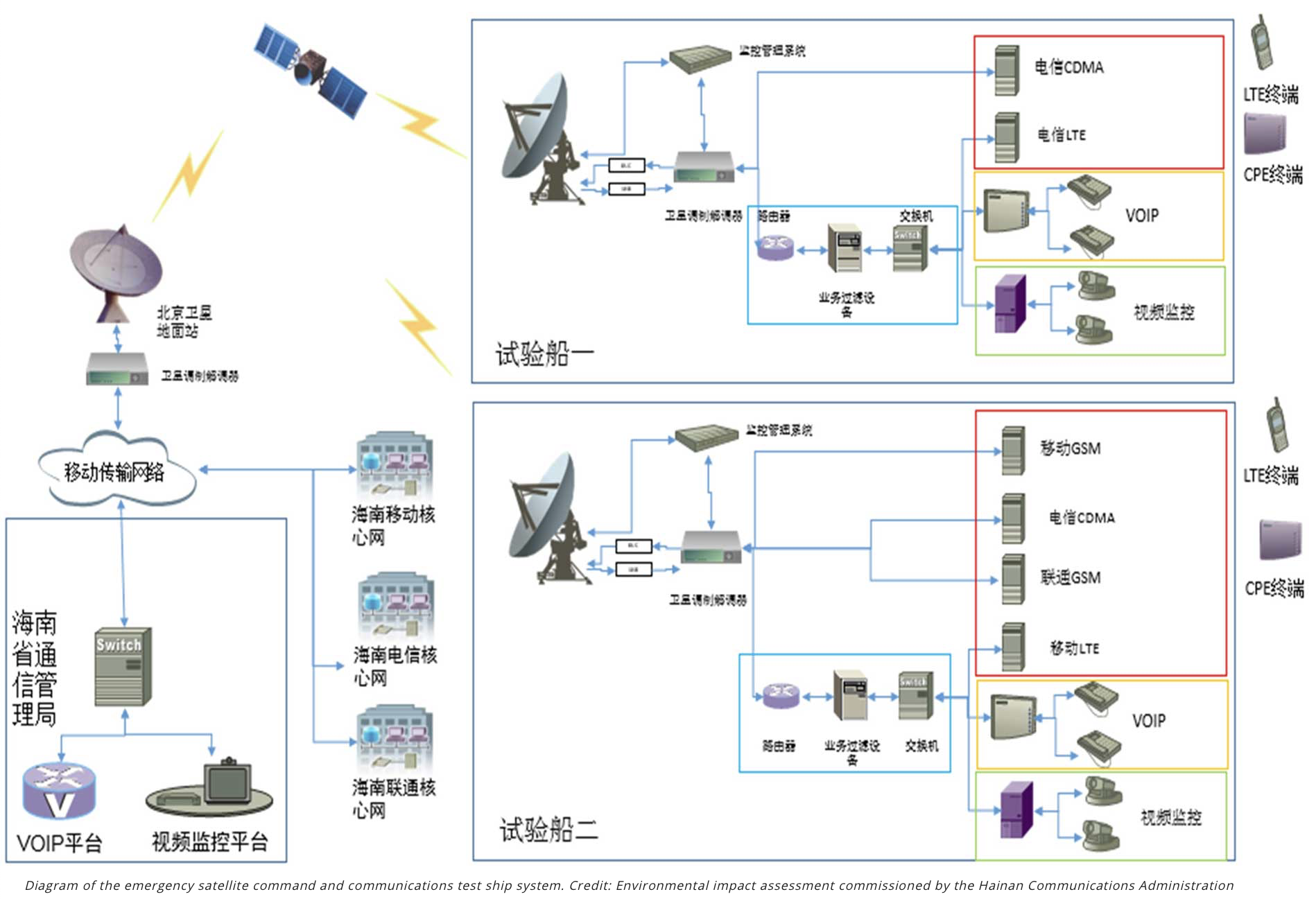

The communications systems can be used both for communication and espionage. Often, fishermen supply their own vessels. However, there are also core contingents of the maritime militia who operate vessels fitted out for militia work instead of fishing; these vessels feature reinforced bows for ramming and high-powered water cannons.[17] The increasing sophistication of militia vessels’ communication equipment is a double-edged sword for Chinese authorities. New equipment, as well as training in its use, has substantially improved command, control, and coordination of militia units. However, the vessels’ resulting professionalism and sophisticated maneuvers make them more identifiable as government-sponsored actors, dampening their ability to function as a gray-zone force. Such improvements also potentially make militia vessels more threatening during at-sea confrontations, raising the risk of unintended escalations with foreign militaries.[18]

Tasks

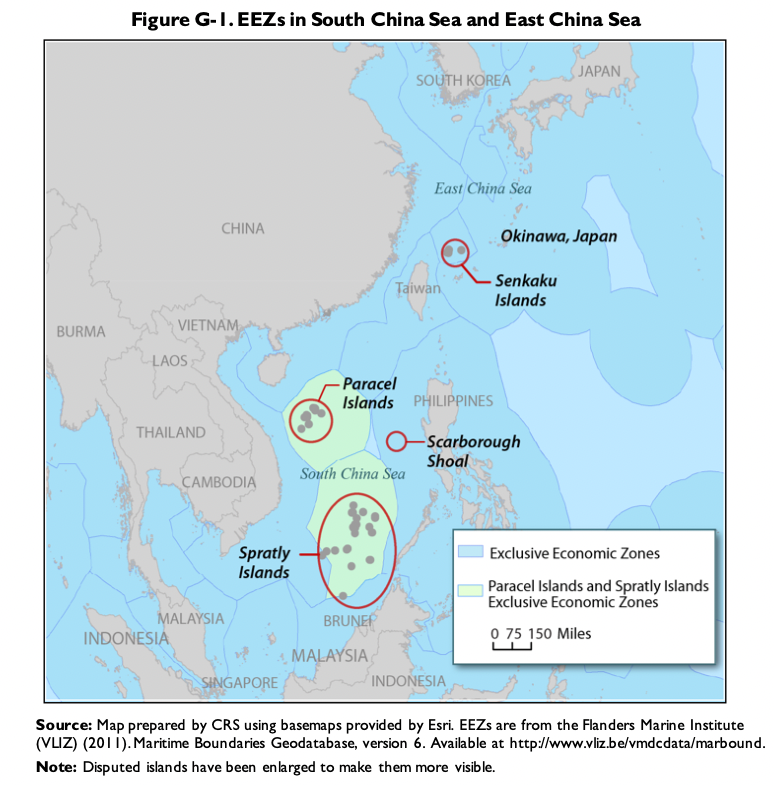

The PRC considers its large fishing fleet an essential part of its sea power, helping with the pursuit of its maritime interests in disputed waters.[19] The maritime militia carries out three different tasks in China’s dispute strategy, also referred to as maritime rights protection:[20] It is active in disputes over the territorial features as well as disputes over the extent of zones of jurisdictions, and it regulates foreign activities – especially military activities – in waters claimed by the PRC. While the first two tasks target mostly neighboring countries, such as Brunei, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam and their conflicting interests in the South China and East China Sea, the third task is primarily a response to the Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) by the US.[3]

According to a Congressional Research Service report, the Maritime Militia and coast guard are deployed more regularly than the PLAN in maritime sovereignty-assertion operations.[12]

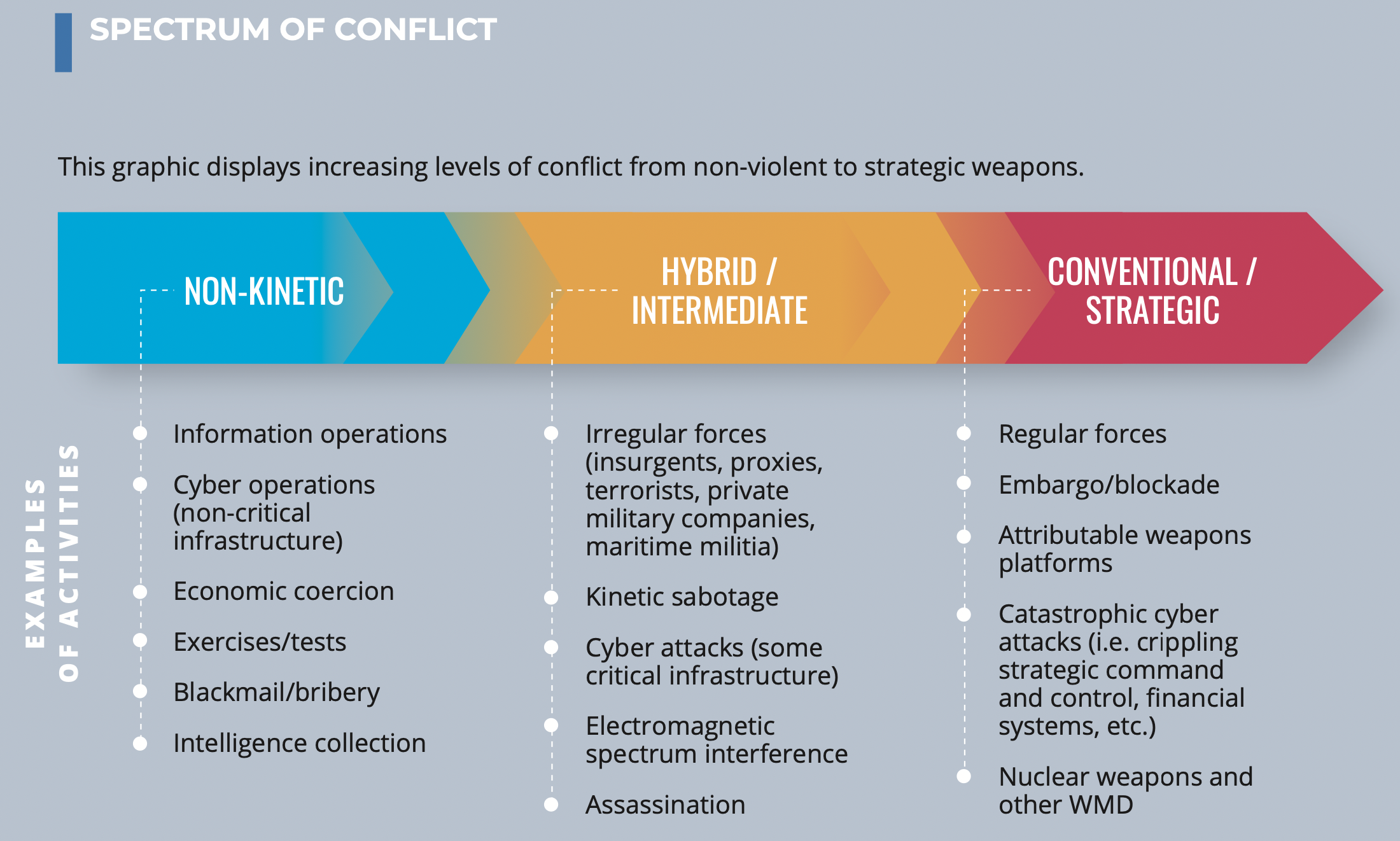

Greyzone Warfare

Various academic journals and media articles claim that the maritime militia increasingly takes part in anti-access and area denial missions in a continuously growing area of the western Pacific. By using law enforcement and fishing vessels, instead of traditional naval assets, the PRC is able to stay with its actions in a greyzone area, avoiding a military conflict while still being able to successfully pursue its maritime claims.[11] The use of the maritime militia, which consists of civilians, allows the PRC to benefit from the legal ambiguity and the diplomatic arbitrariness coming from the involvement of civilians in such maritime operations.[21]

According to research from the Taiwanese Institute for National Defense and Security Research, China’s maritime militia is part of their “grey zone” tactics, which are used to wage conflict against China’s neighbors without crossing the threshold into conventional war.[22] The maritime militia is a particularly useful gray zone force because Chinese authorities can deny or claim affiliation with its members depending on context. China can send its militia to harass foreign vessels in contested areas, but publicly assert that the vessels are independent from government control, thus avoiding escalation with other states. At the same time, if militia members are hurt during confrontations with foreign vessels, the Chinese government can claim the need to “defend” its own fishermen, mobilizing domestic nationalism to improve its bargaining position in a crisis.[18]

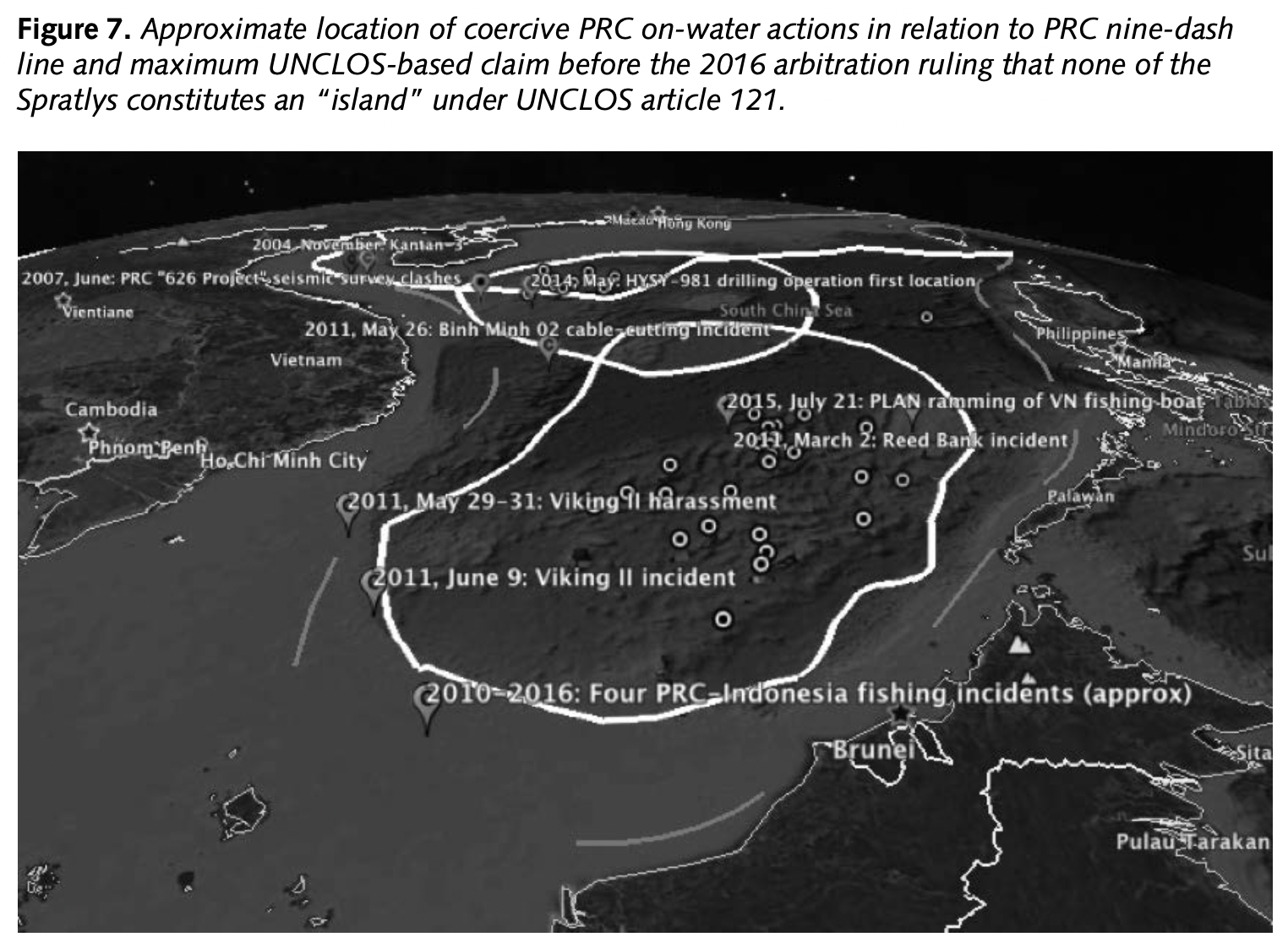

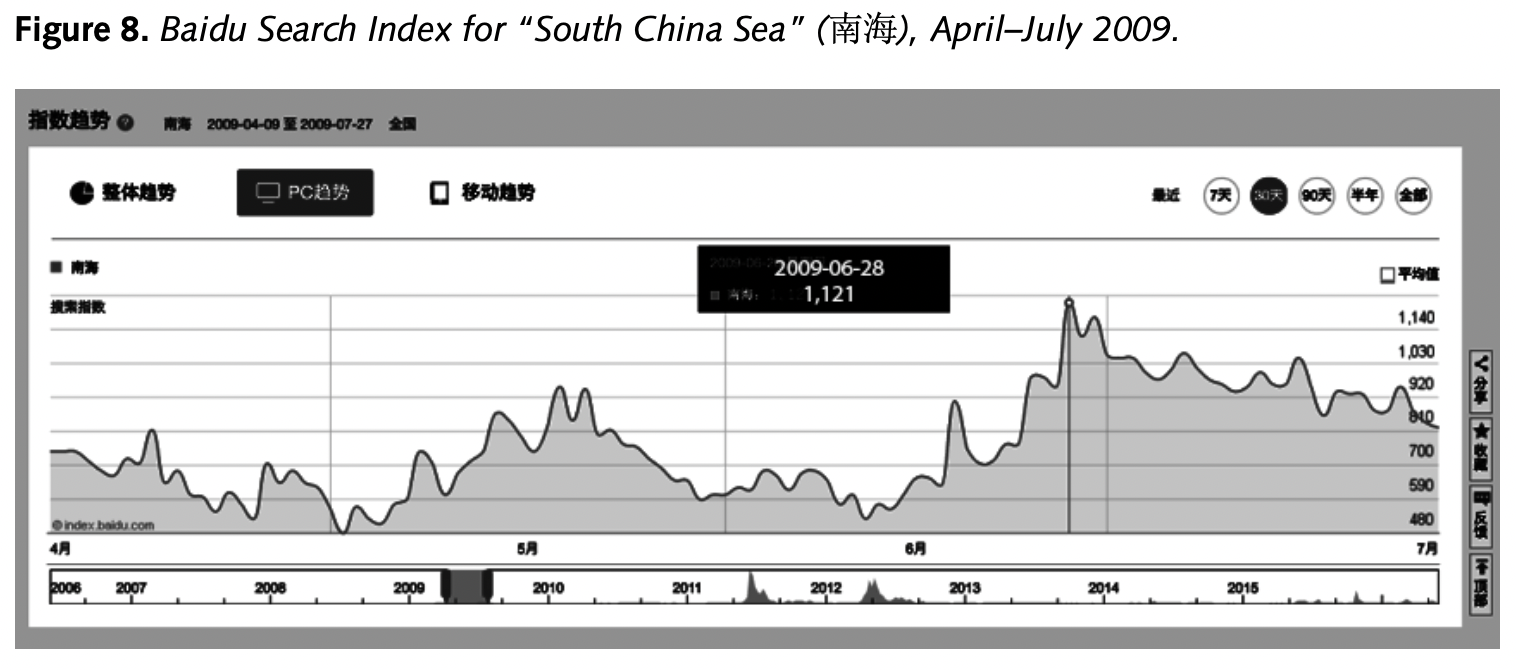

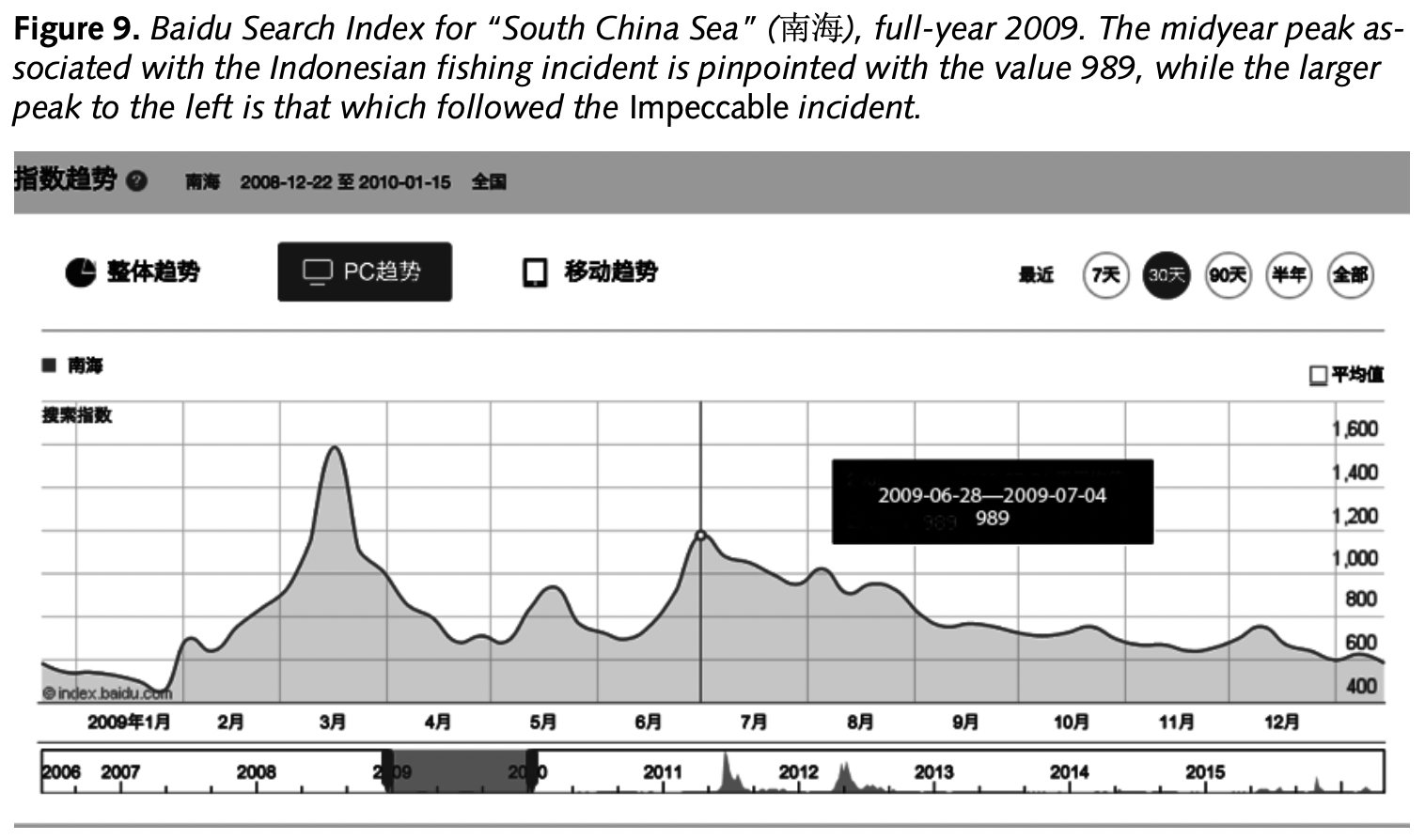

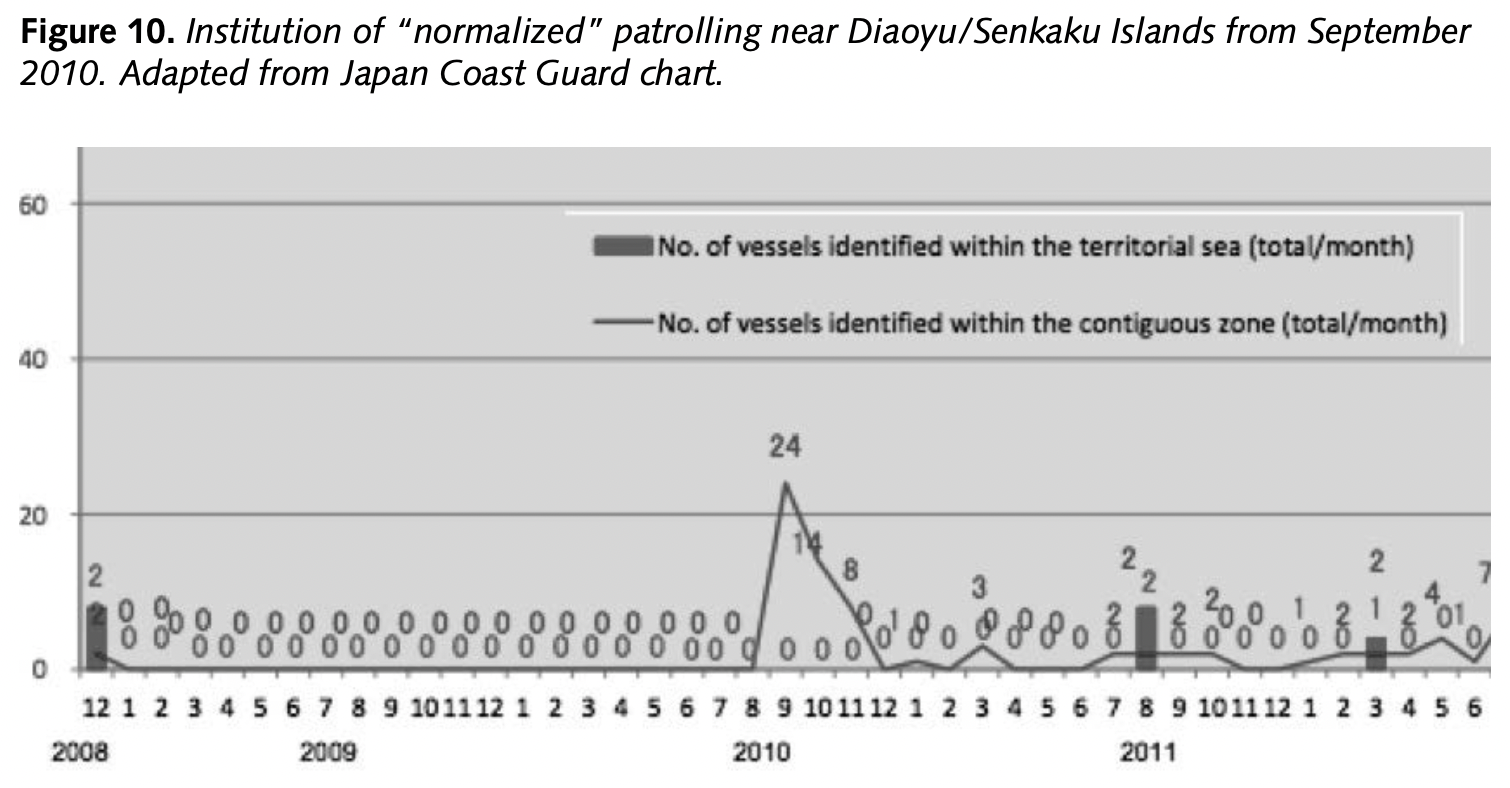

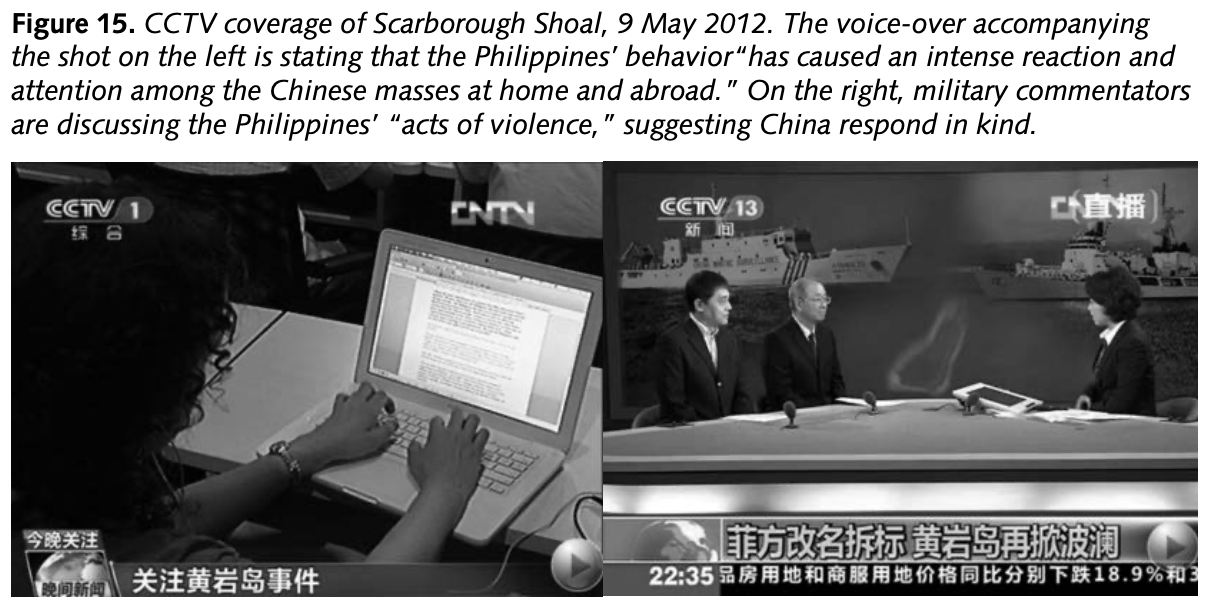

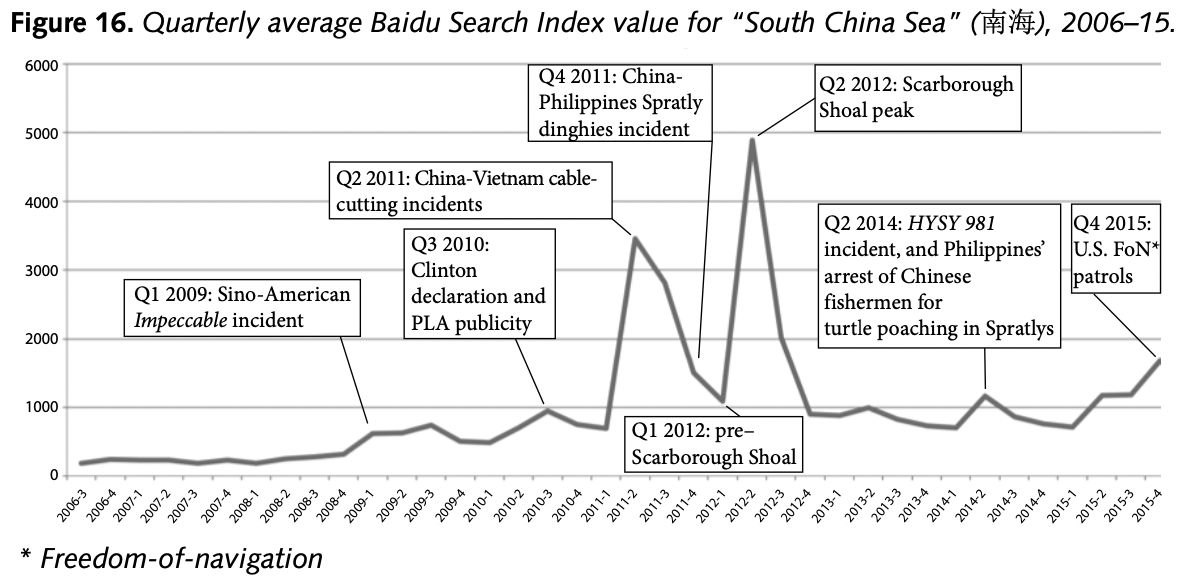

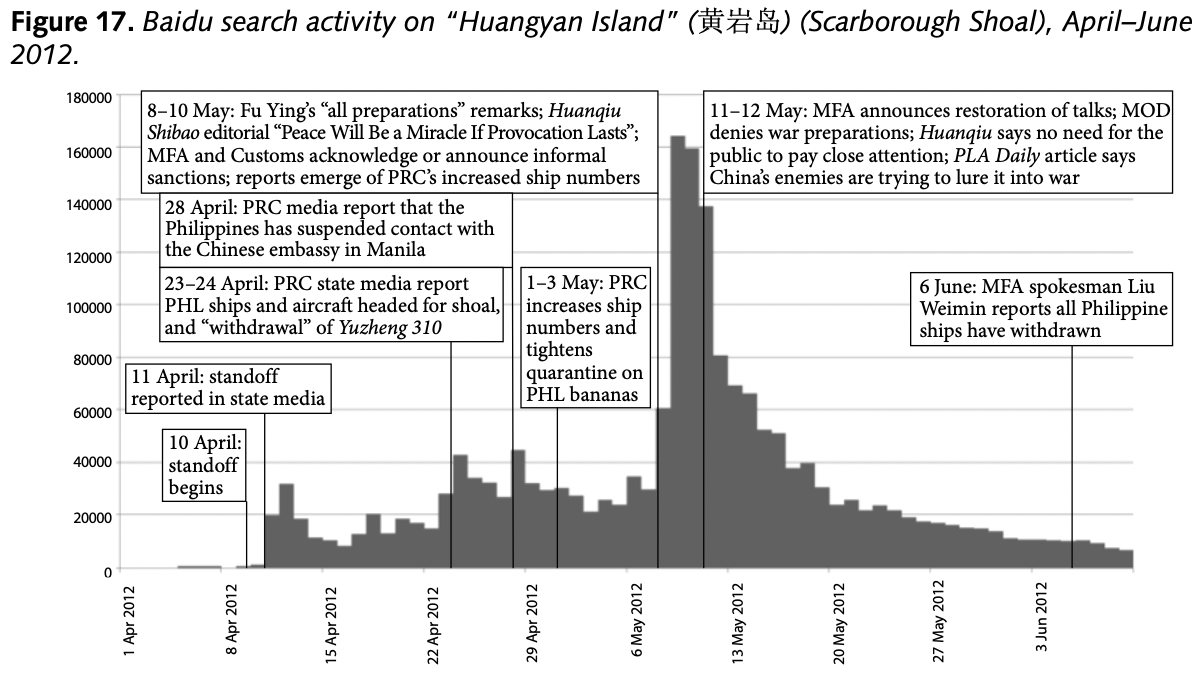

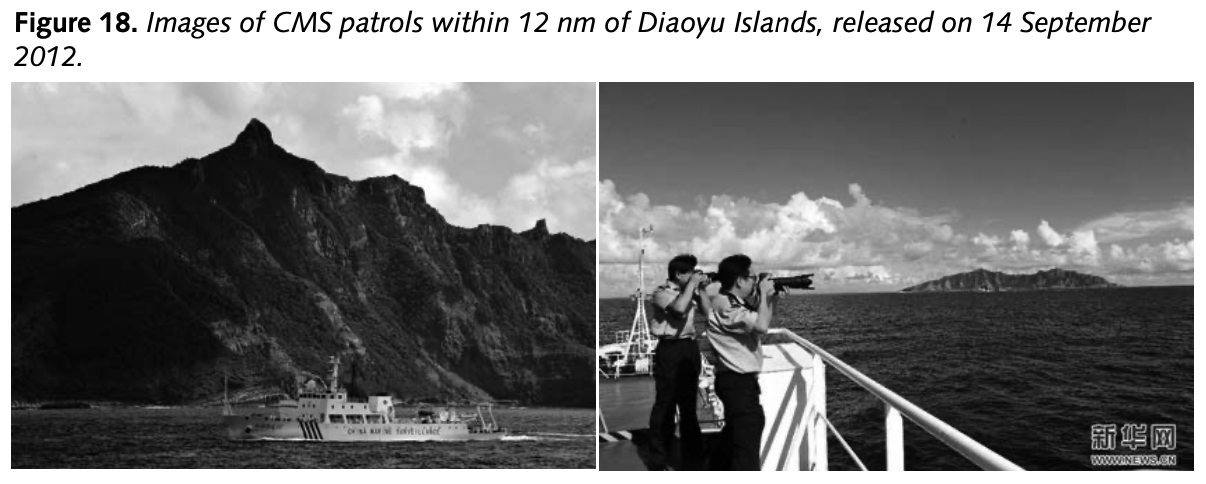

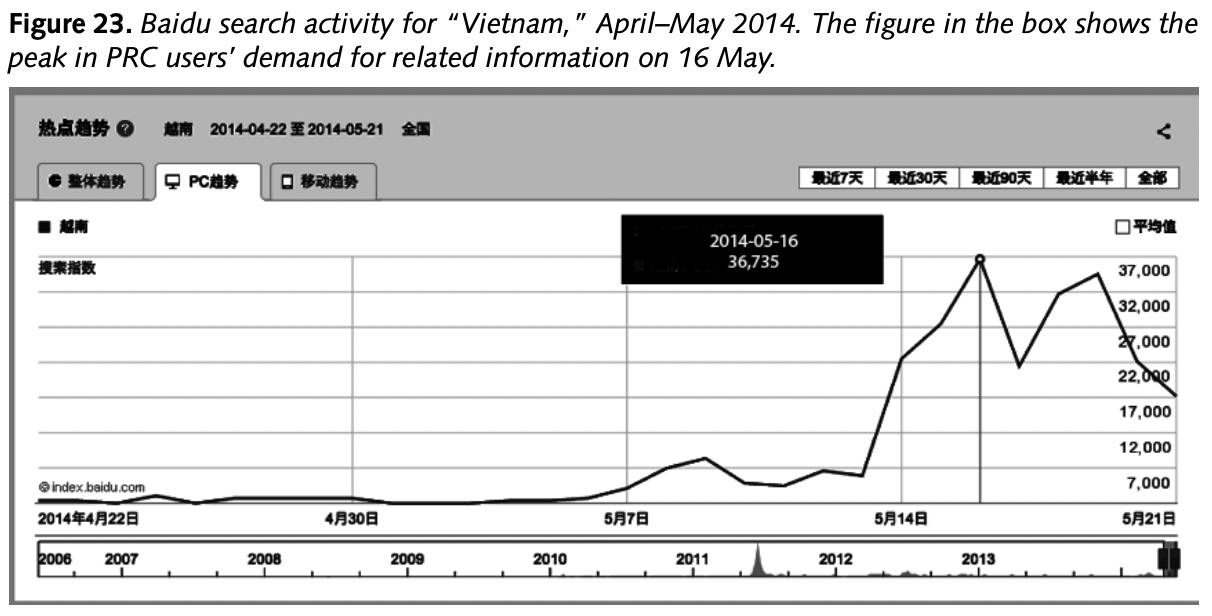

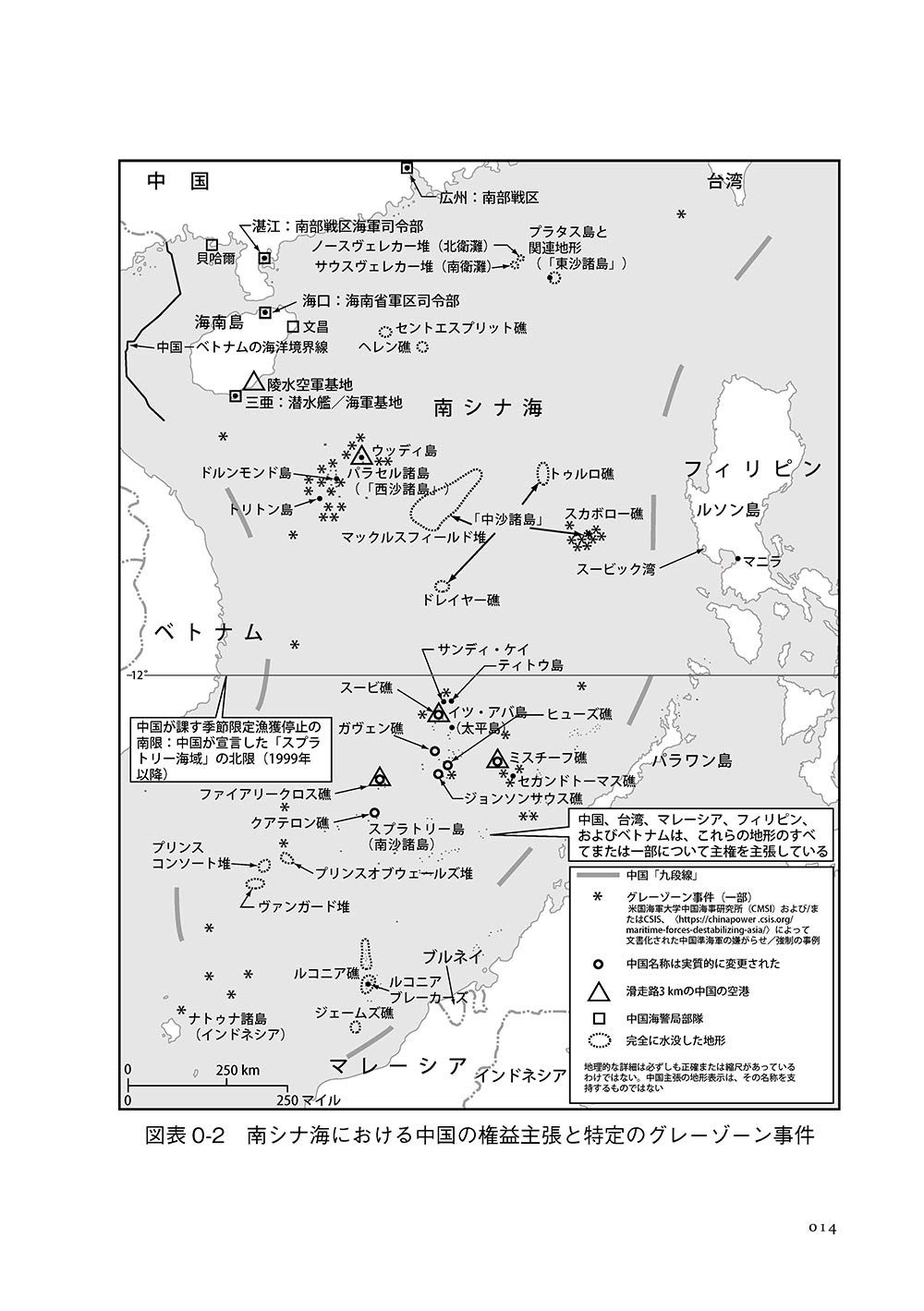

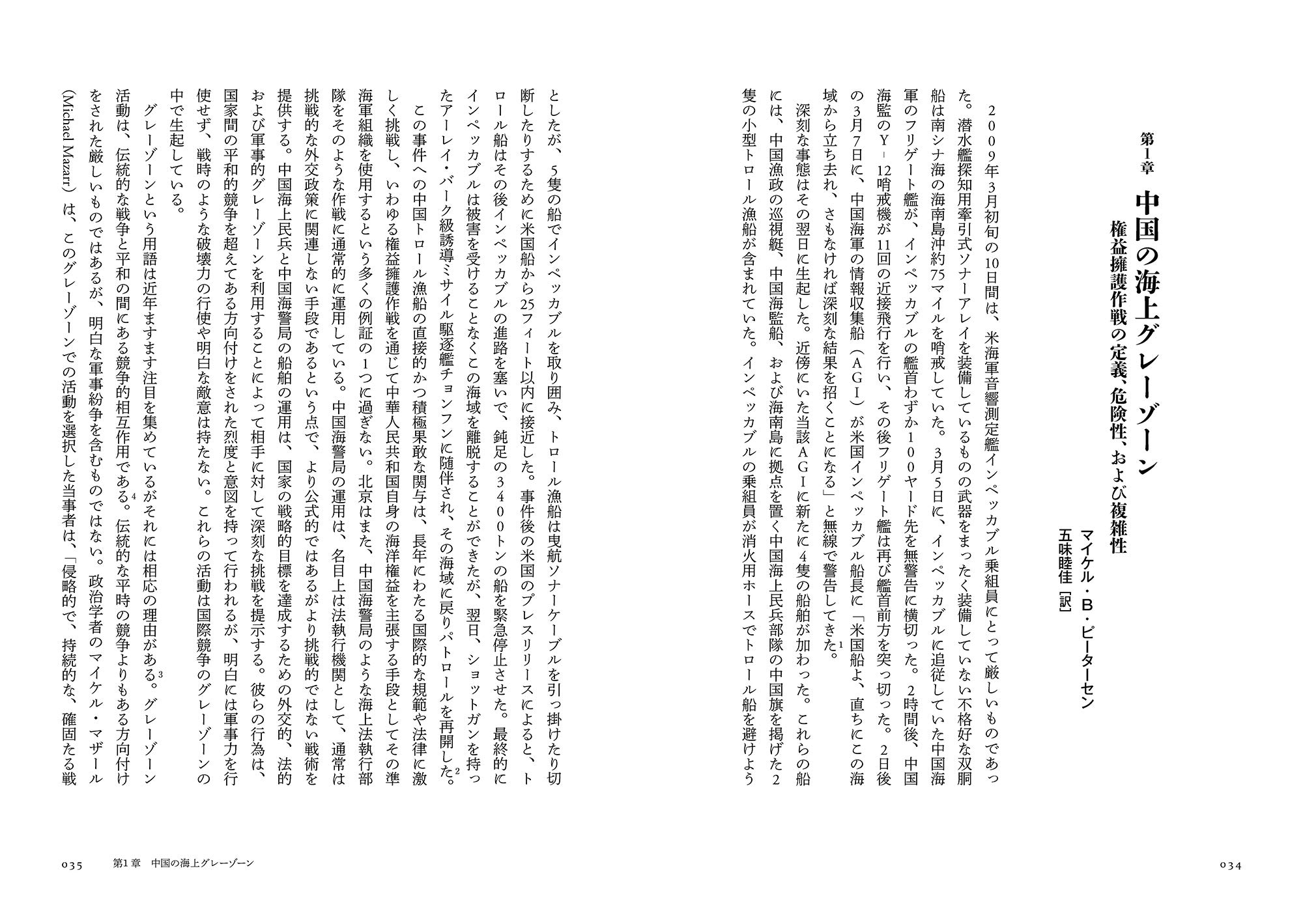

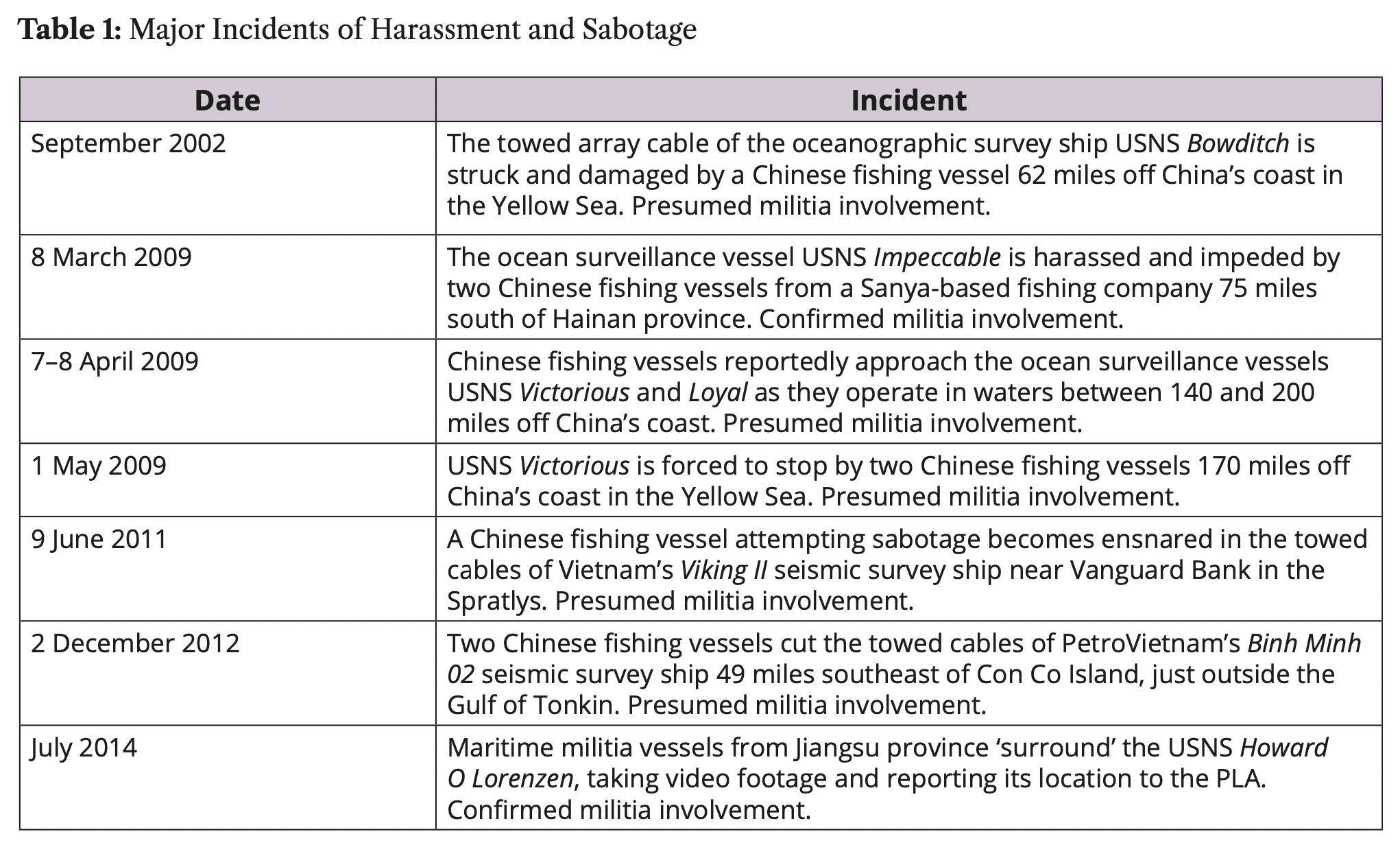

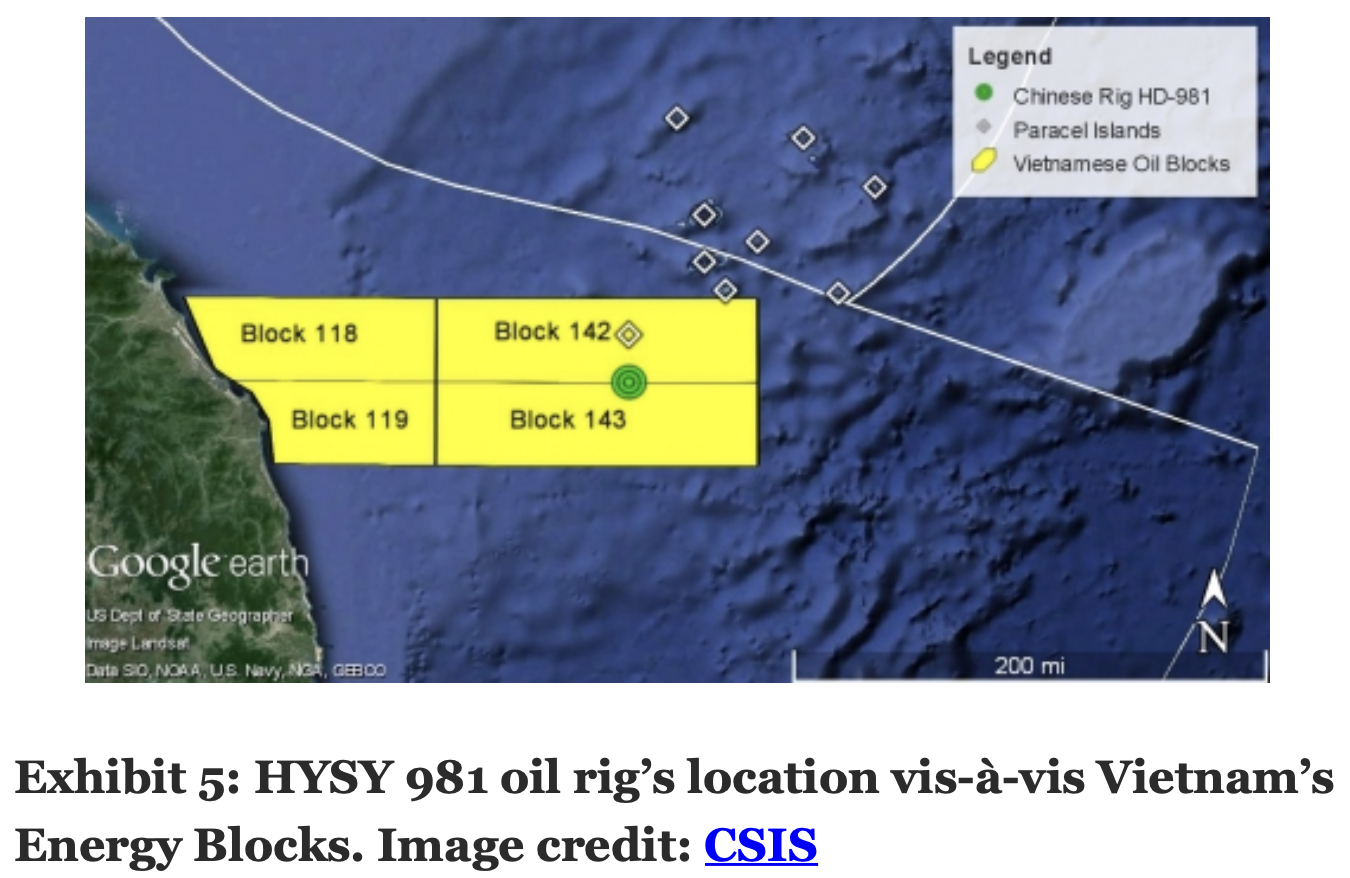

Some of the incidents, which are generally defined as greyzone operations within the academic discourse, are the harassment of the USNS Impeccable in 2009,[23] the Senkaku Island incident in 2010,[24] the Scarborough Shoal standoff in 2012, the Hai Yang Shi You 981 standoff in 2014,[19] and the Natuna Islands incident in 2016.[25]

Control

It is uncertain how much control the Chinese authorities have over the fishing vessels operating in the South China Sea. Funding problems are apparent, since fishermen earn more by fishing, than participating in militia operations. Command and coordination arrangements of the maritime militia are unclear as well and only a weak exertion of control on fishermen can be noticed.[11] Since most members of the maritime militia are simultaneously fishermen, they regularly pursue their own agendas, sometimes contradictory to what the government wants.[26] For instance, multiple fishermen went against the central government by using maritime militia policy to fish for protected and endangered species in disputed waters.[11] Moreover, factors such as food security and economic advantages influence fishermen to operate outside of China’s exclusive economic zone,[19] since the PRCs jurisdictional waters are polluted, and a depletion of China’s fishery resources can be noticed.[25] Therefore, while the maritime militia is involved in greyzone operations, it is misleading to portray it as a professional coherent body, which can be systematically used by the central government.[11]

See also

- Cabbage tactics

- Chinese salami slicing theory

- Fishing industry in China

- Territorial disputes in the South China Sea

References

- https://edition.cnn.com/2023/08/12/asia/china-maritime-militia-philippines-tensions-intl-hnk-ml/index.html

- Kraska, James. “China’s Maritime Militia Vessels May Be Military Objectives During Armed Conflict”. thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

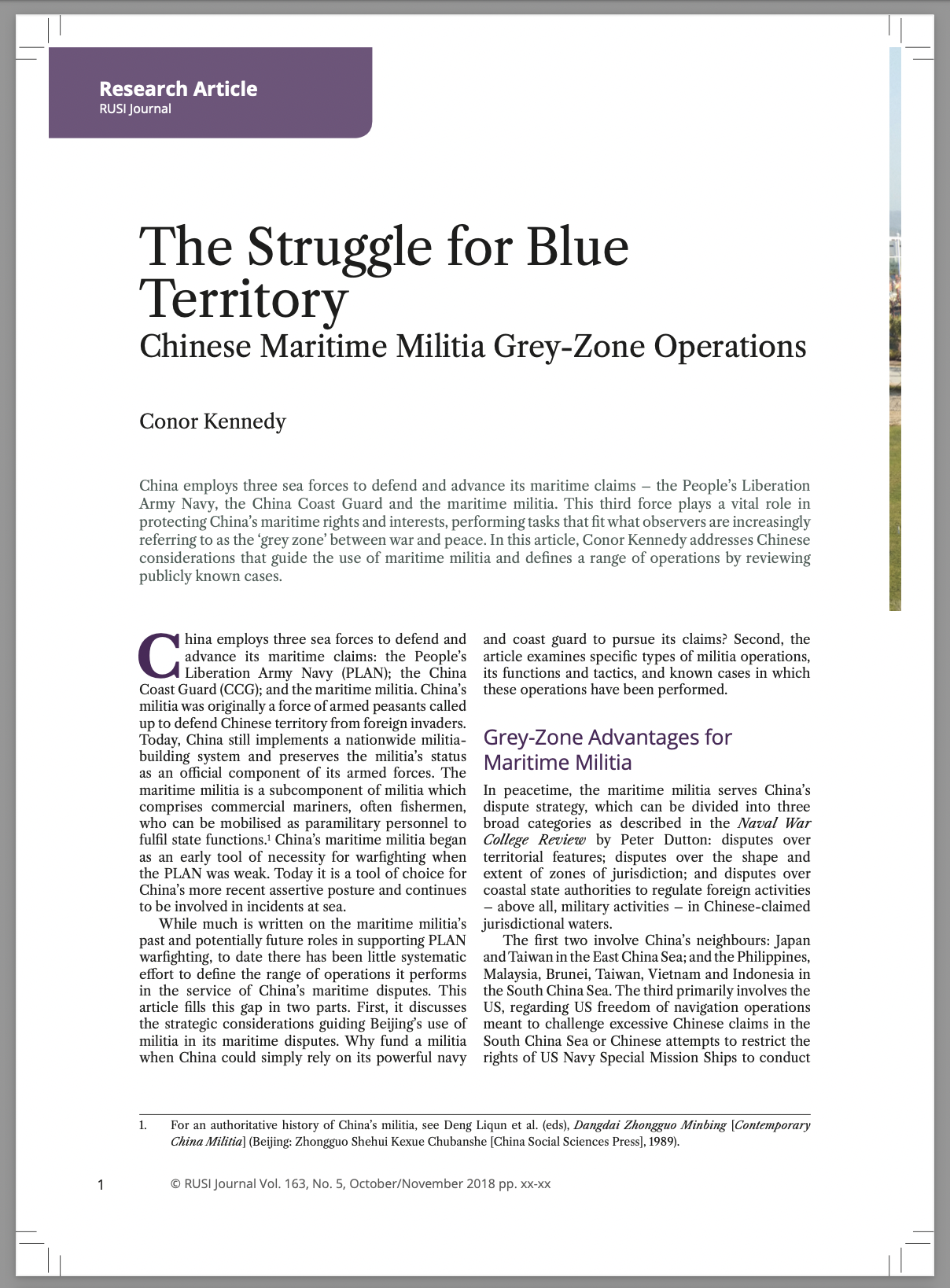

- Kennedy, Conor (2018). “The Struggle for Blue Territory. Chinese Maritime Militia Grey-Zone Operations”. RUSI Journal. 163 (5): 8 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Cui, Haoran; Shi, Yubing (2022). “A Comparative Analysis of the Legislation on Maritime Militia Between China and Vietnam”. Ocean Development & International Law. 53 (2–3): 149 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Grossman, Derek; Ma, Logan (6 April 2020). “A Short History of China’s Fishing Militia and What It May Tell Us”. rand.org. RAND Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Jakhar, Pratik (15 April 2019). “Analysis: What’s so fishy about China’s ‘maritime militia’?”. monitoring.bbc.co.uk. BBC Monitoring. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Poling, Gregory B.; Mallory, Tabitha Grace; Prétat, Harrison; The Center for Advanced Defense Studies (2021). “Pulling Back the Curtain on China’s Maritime Militia”.

- Sevastopulo, Demetri; Hille, Kathrin (28 April 2019). “US warns China on aggressive acts by fishing boats and coast guard”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Yeo, Mike (31 May 2019). “Testing the waters: China’s maritime militia challenges foreign forces at sea”. Defense News. Retrieved 9 July 2020.[dead link]

- Center for Strategic and International Studies (2022). “The Ebb and Flow of Beijing’s South China Sea Militia”.

- Luo, Shuxian; Panter, Jonathan G. (2021). “China’s Maritime Militia and Fishing Fleets. A Primer for Operational Staffs and Tactical Leaders”. Military Review: 11–15.

- “Ronald O’Rourke, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Implications for U.S. Interests—Background and Issues for Congress, R42784. Congressional Research Service. pp. 13, 76”. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- Owens, Tess (1 May 2016). “China Is Reportedly Training a ‘Maritime Militia’ to Patrol the Disputed South China Sea”. vice.com. Vice News. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Song, Andrew (2021). “Civilian at Sea: Understanding Fisheries’ Entanglement with Maritime Border Security”. Geopolitics: 10 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Chan, Eric. “Escalating Clarity without Fighting: Countering Gray Zone Warfare against Taiwan (Part 2)”. globaltaiwan.org. The Global Taiwan Institute. Retrieved 21 June2021.

- Song, Andrew (2021). “Civilian at Sea: Understanding Fisheries’ Entanglement with Maritime Border Security”. Geopolitics: 10 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Manthorpe, Jonathan (28 April 2019). “Beijing’s maritime militia, the scourge of South China Sea”. Asia Times. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 9 July2020.

- Luo, Shuxian; Panter, Jonathan (January–February 2021). “China’s Maritime Militia and Fishing Fleets: A Primer for Operational Staffs and Tactical Leaders”. Military Review. 101(1): 6–21. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Zhang, Hongzhou (2016). “Chinese fishermen in disputed waters: Not quite a “people’s war””. Marine Policy. 68: 65–68 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

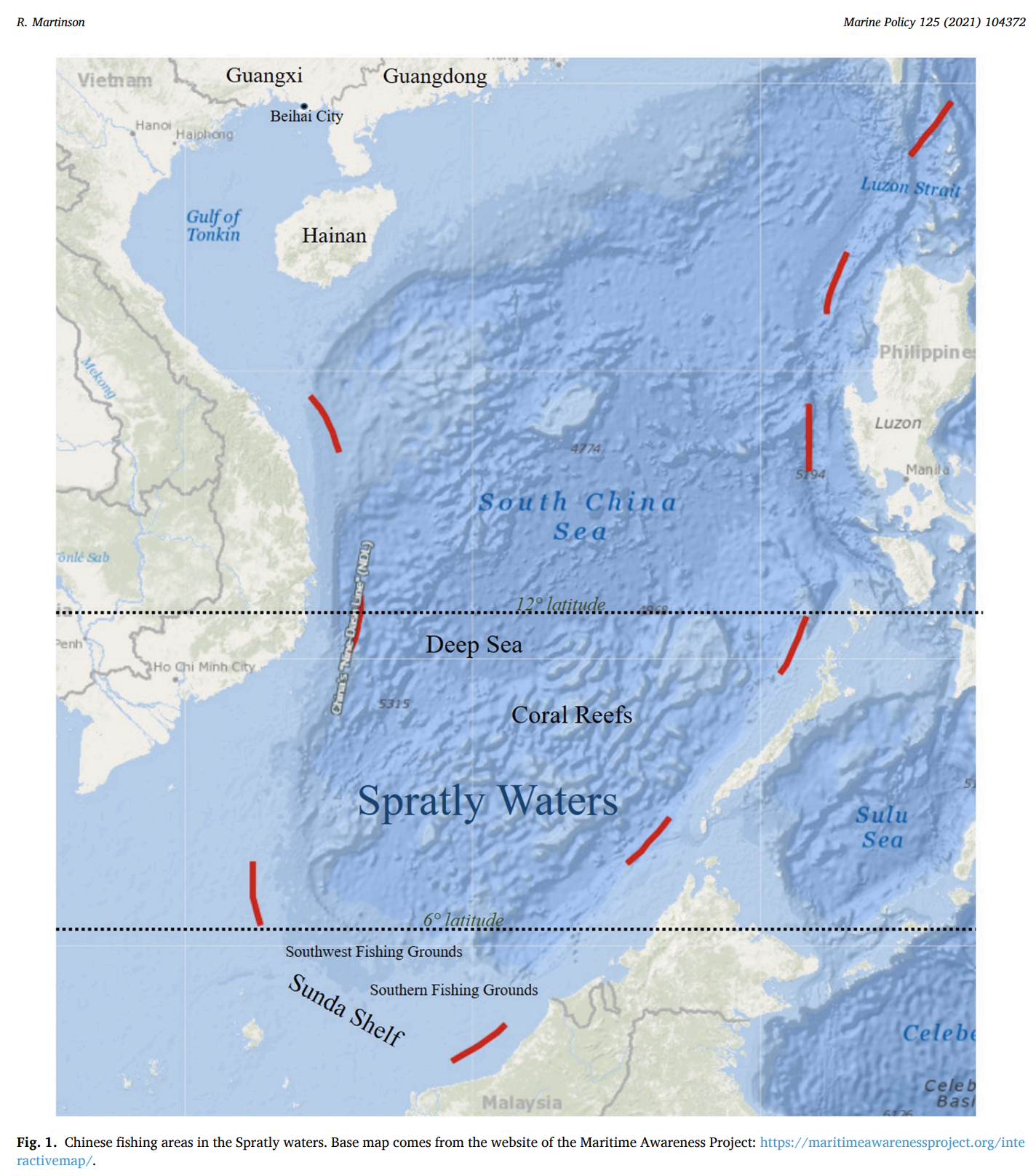

- Martinson, Ryan (2021). “Catching sovereignty fish: Chinese fishers in the southern Spratlys”. Marine Policy. 125: 8 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- Yoo, Su Jin; Koo, Min Gyo (2022). “Is China Responsible for Its Maritime Militia’s Internationally Wrongful Acts? The Attribution of the Conduct of a Parastatal Entity to the State”. Business and Politics. 24: 278 – via Cambridge University Press.

- “DIPLOMACY: Maritime militia warning issued”. Taipei Times. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Pedrozo, Raul (2009). “Close Encounters at Sea: The USNS Impeccable Incident”. Naval War College Review. 62 (3): 106 – via JSTOR.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (2023). “Japanese Territory. Trends in China Coast Guard and Other Vessels in the Waters Surrounding the Senkaku Islands, and Japan’s Response”.

- Zhang, Hongzhou; Bateman, Sam (2017). “Fishing Militia, the Securitization of Fishery and the South China Sea Dispute”. Contemporary Southeast Asia. 39 (2): 292–294 – via JSTOR.

- Roszko, Edyta (2021). “Navigating Seas, Markets, and Sovereignties: Fishers and Occupational Slippage in the South China Sea”. Anthropological Quarterly. 94 (4): 663 – via Project Muse.

External links

中国海上民兵

|

|

中华人民共和国军事

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

中國海上民兵是对中华人民共和国政府资助海上民兵的指控[1],据称以武裝漁船方式為外界所認識。

观点

“武装渔船队是中国力量投射的一部分” 有争议[1],部署渔船是为了控制有争议海上领土、海岛(包括南海、钓鱼台列屿等)。由于在南海活动时没有明确的身份标识,他们有时被[谁?]称为 「小蓝人」[註 1][2]。

注释

参考文献

- Thomas, Jason. China’s ‘fishermen’ mercenaries. The Weekend Australian. 2020-09-02 [2020-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-15).

- Jakhar, Pratik. Analysis: What’s so fishy about China’s ‘maritime militia’?. monitoring.bbc.co.uk. BBC Monitoring. 15 April 2019 [25 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-15).

参见

中国人民軍海上民兵

中国人民軍海上民兵(ちゅうごくじんみんぐんかいじょうみんぺい)は、中国の政府出資の海上民兵である[1]。南シナ海で活動していると報じられていることから、2014年のクリミア併合時のロシアの「リトル・グリーン・メン」に言及した海軍兵学校のアンドリュー・S・エリクソンの造語である「リトル・ブルー・メン」と呼ばれることもある[2]。

武装した漁船団は中国のパワープロジェクション[1]の一環であり、領土を掌握し、南シナ海全体の中国の主張に異議を唱える者を標的にするために配備されている。2016年には230隻の漁船が同じ島に群がった[1]。2020年8月には、日本の尖閣諸島に100隻以上の漁船が嫌がらせを行った[1]。

参考文献

- ^ a b c d Thomas, Jason (2020年9月2日). “China’s ‘fishermen’ mercenaries”. The Weekend Australian

- ^ Jakhar, Pratik (2019年4月15日). “Analysis: What’s so fishy about China’s ‘maritime militia’?”. monitoring.bbc.co.uk. BBC Monitoring. 2020年7月25日閲覧。

***

Andrew S. Erickson, “Xi’s Fast & Furious Nuclear Buildup & Beyond: Key Text from Pentagon’s 2023 China Military Power Report,” China Analysis from Original Sources 以第一手资料研究中国, 16 January 2024.

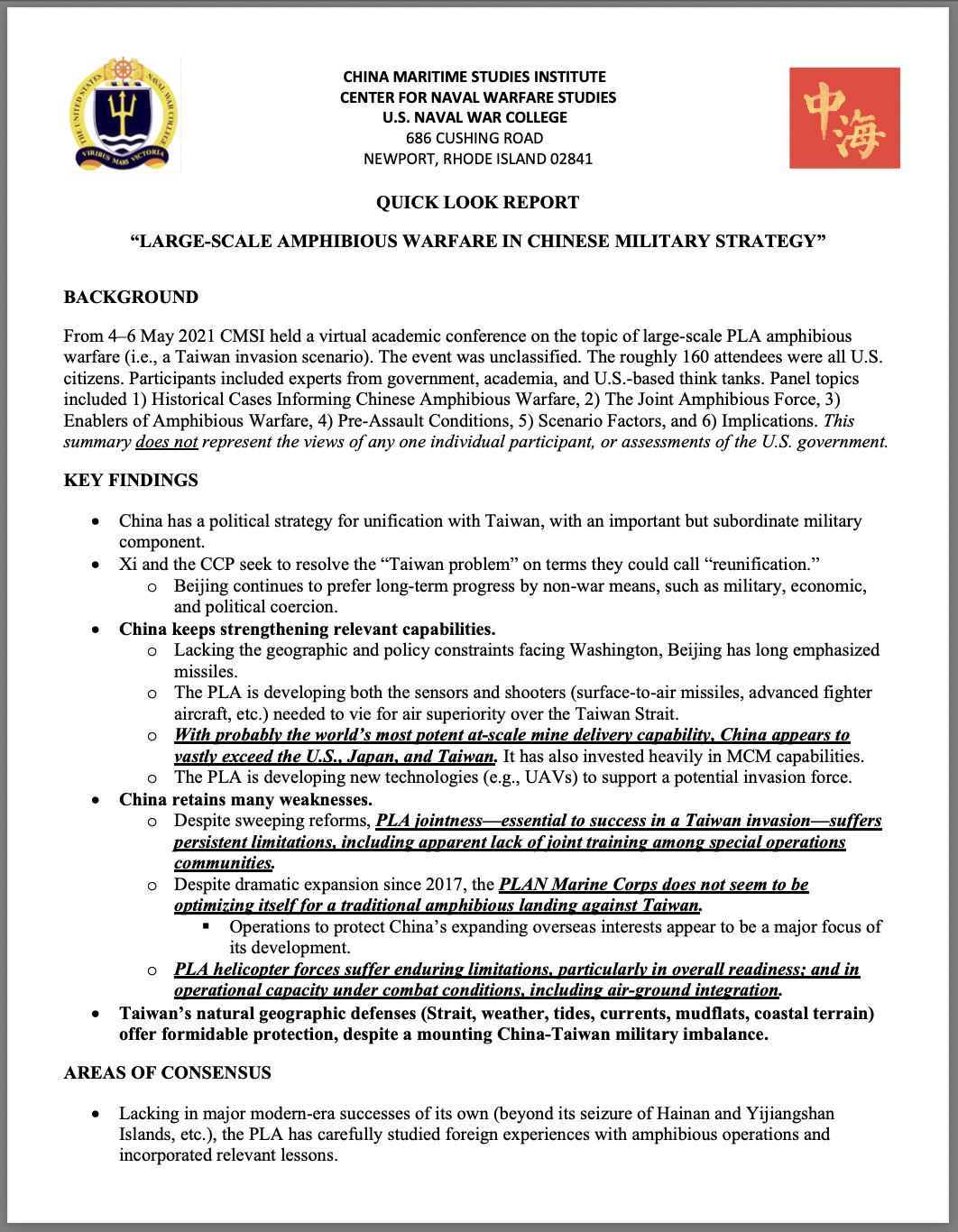

Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, October 19, 2023).

- Publication summarizing report’s China nuclear weapons-related content:

Gabriel B. Collins and Andrew S. Erickson, Reaping the Whirlwind: How China’s Coercive Annexation of Taiwan Could Trigger Nuclear Proliferation in Asia and Beyond (Houston, TX: Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University, 25 October 2023).

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD FULL-TEXT PDF.

KEY CONTENT FROM 2023 CHINA MILITARY POWER REPORT (INCLUDES SOME MARITIME MILITIA-SPECIFIC ADDITIONS NOT INCLUDED IN THE ABOVE POSTING):

[Please note: bolding, underlining, italics, annotations in brackets, etc. are from me – Andrew Erickson – and not from the original report itself. Be sure to check the report’s exact text firsthand here.]

p. 18

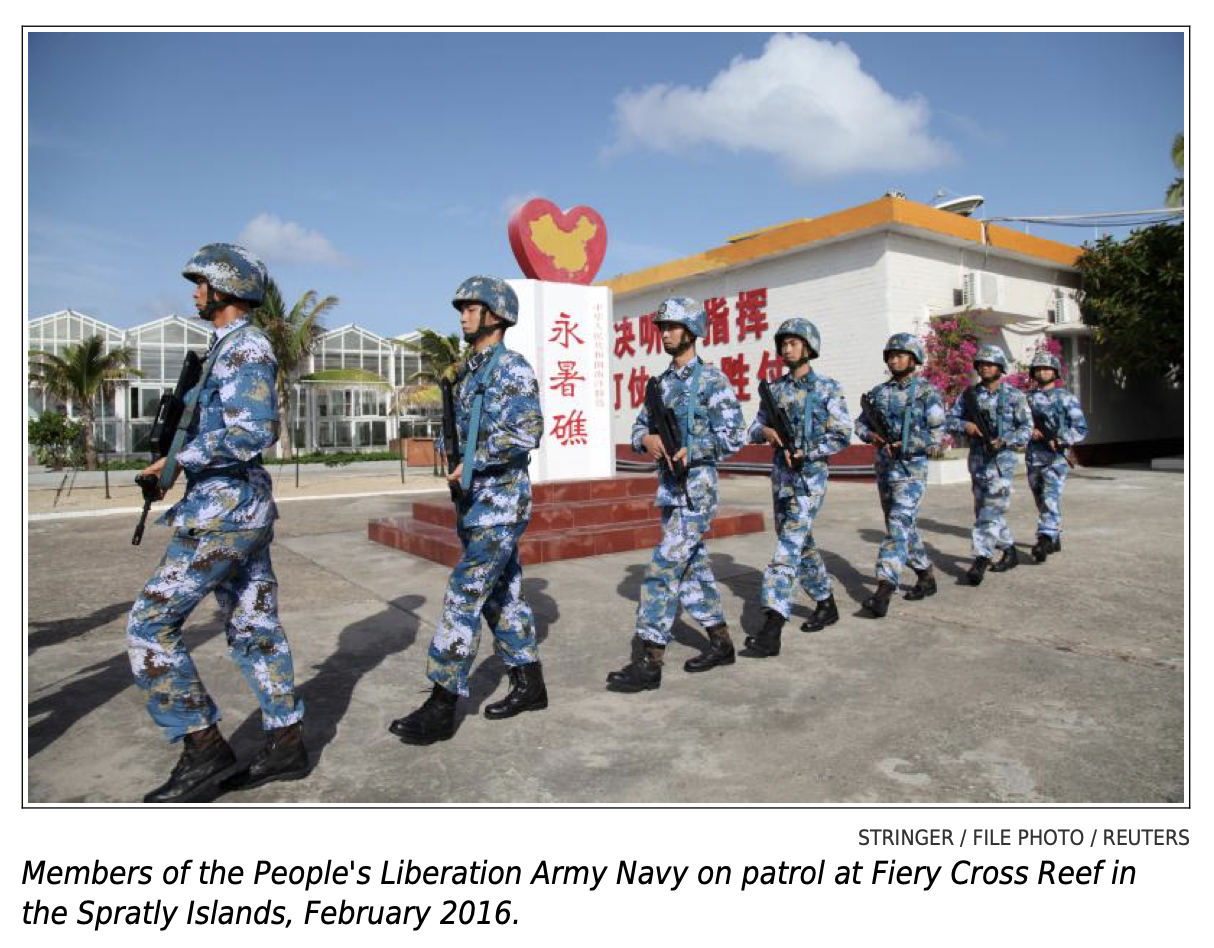

The PRC continued to employ the PLA Navy (PLAN), China Coast Guard, and maritime militia to patrol the region throughout 2022.

p. 32

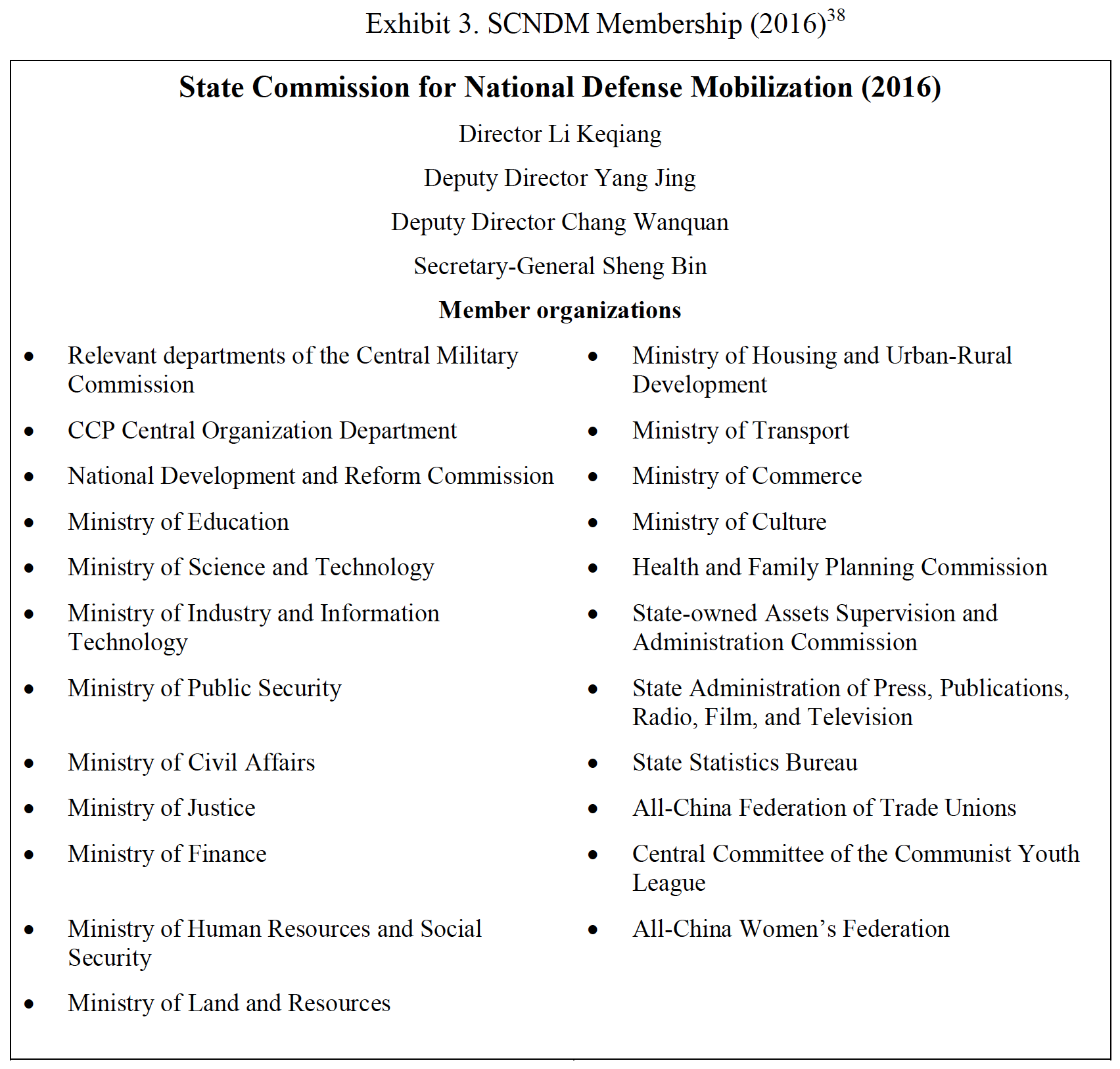

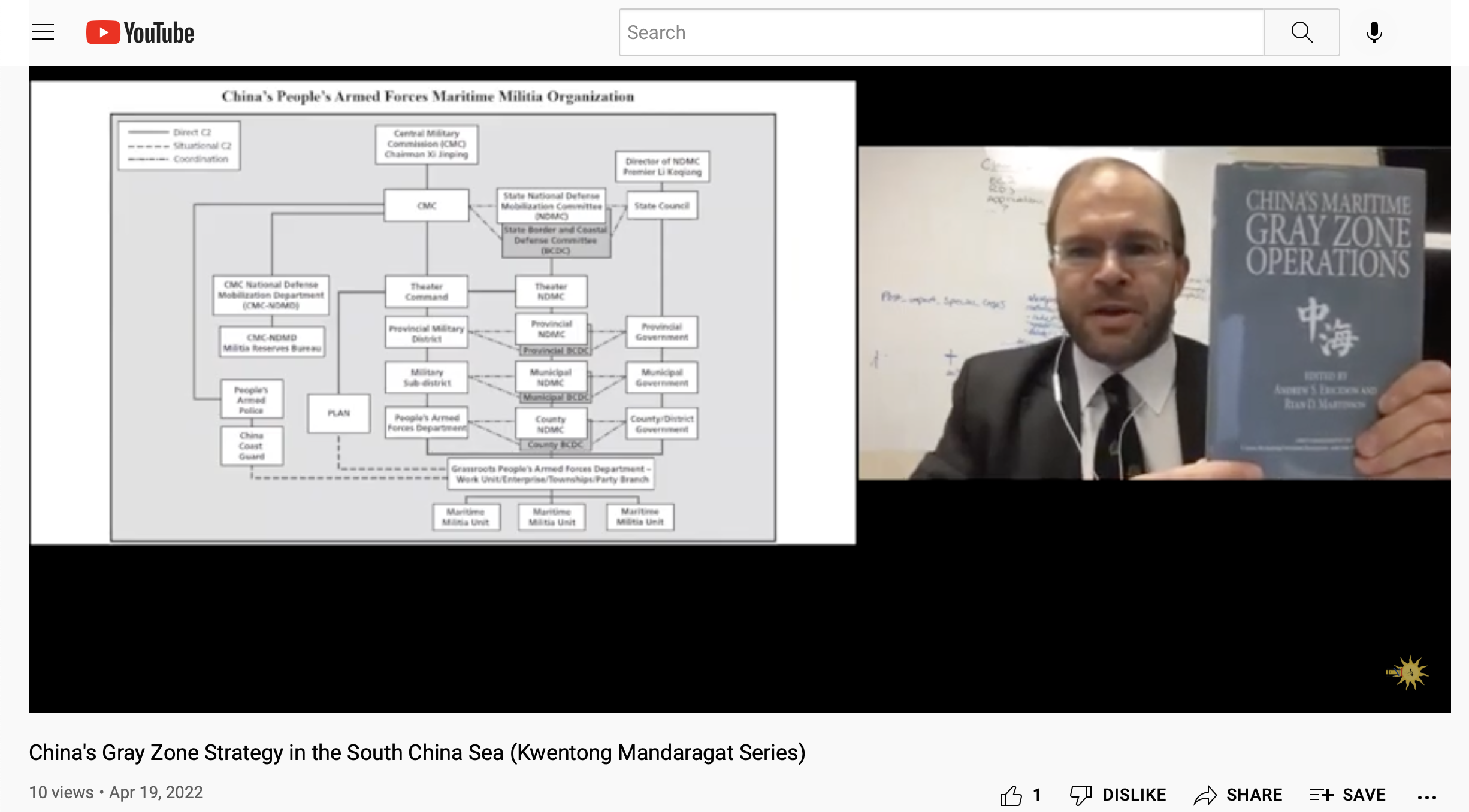

The National Defense Mobilization System. This MCF system binds the other systems as it seeks to mobilize the PRC’s military, economic, and social resources to defend or advance China’s sovereignty, security and development interests. The Party views China’s growing strength as only useful to the extent that the party-state can mobilize it. China characterizes mobilization as the ability to precisely use the instrument, capability, or resource needed, when needed, for the duration needed. Within the PLA, 2015-16 reforms elevated defense mobilization to a department called the National Defense Mobilization Department (NDMD), which reports directly to the CMC. The NDMD plays an important role in this system by organizing and overseeing the PLA’s reserve forces, militia, and provincial military districts and below. This system also seeks to integrate the state emergency management system into the national defense mobilization system in order to achieve a coordinated military-civilian response during a crisis. Consistent with the Party’s view of international competition, many MCF mobilization initiatives not only seek to reform how the PRC mobilizes for war and responds to emergencies, but how the economy and society can be leveraged to support the PRC’s strategic needs for international competition.

p. 75

PLA Reserves, Paramilitary, Militia: increasing operability, integration

PLAN, CCG, CMM

INCREASING OPERABILITY WITH PLA RESERVES, PARAMILITARY & MILITIA

Key Takeaways

● Interoperability and integration between the PLA, its reserve components, and the PRC’s paramilitary forces continue to grow in scale and sophistication, including the coordination between the PLAN, the China Coast Guard (CCG), and the China Maritime Militia (CMM).

● The PRC primarily uses paramilitary maritime organizations in maritime disputes, selectively using the PLAN to provide overwatch in case of escalation.

p. 76

Internal security: MPS, MSS, PAP, PLA, Militia

Militia force/org details

p. 77

CMM often performs tasks in conjunction/coordination with PLAN & CCG

“Local maritime militia forces…perform tasks including safeguarding maritime claims, protecting fisheries, providing logistic support, search and rescue, and surveillance and reconnaissance, often in conjunction or coordination with the PLAN and the CCG.”

p. 80

CHINA MARITIME MILITIA

- CMM train with/assist PLAN + CCG

- “CMM vessels train with and assist the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and the China Coast Guard (CCG) in tasks such as safeguarding maritime claims, surveillance and reconnaissance, fisheries protection, logistics support, and search and rescue.”

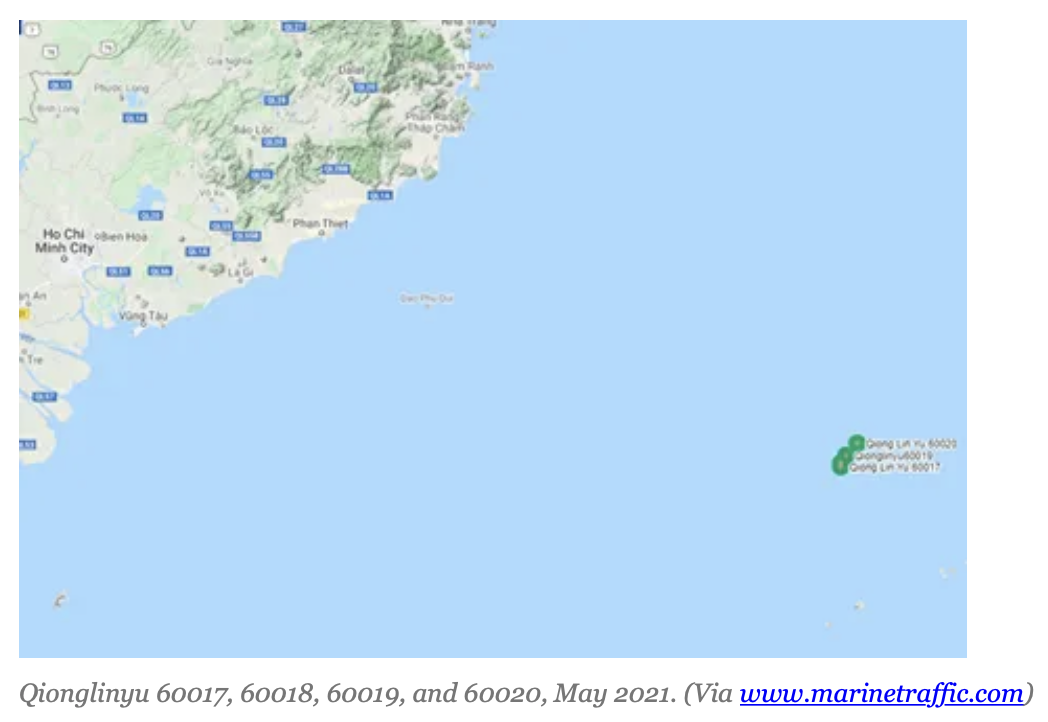

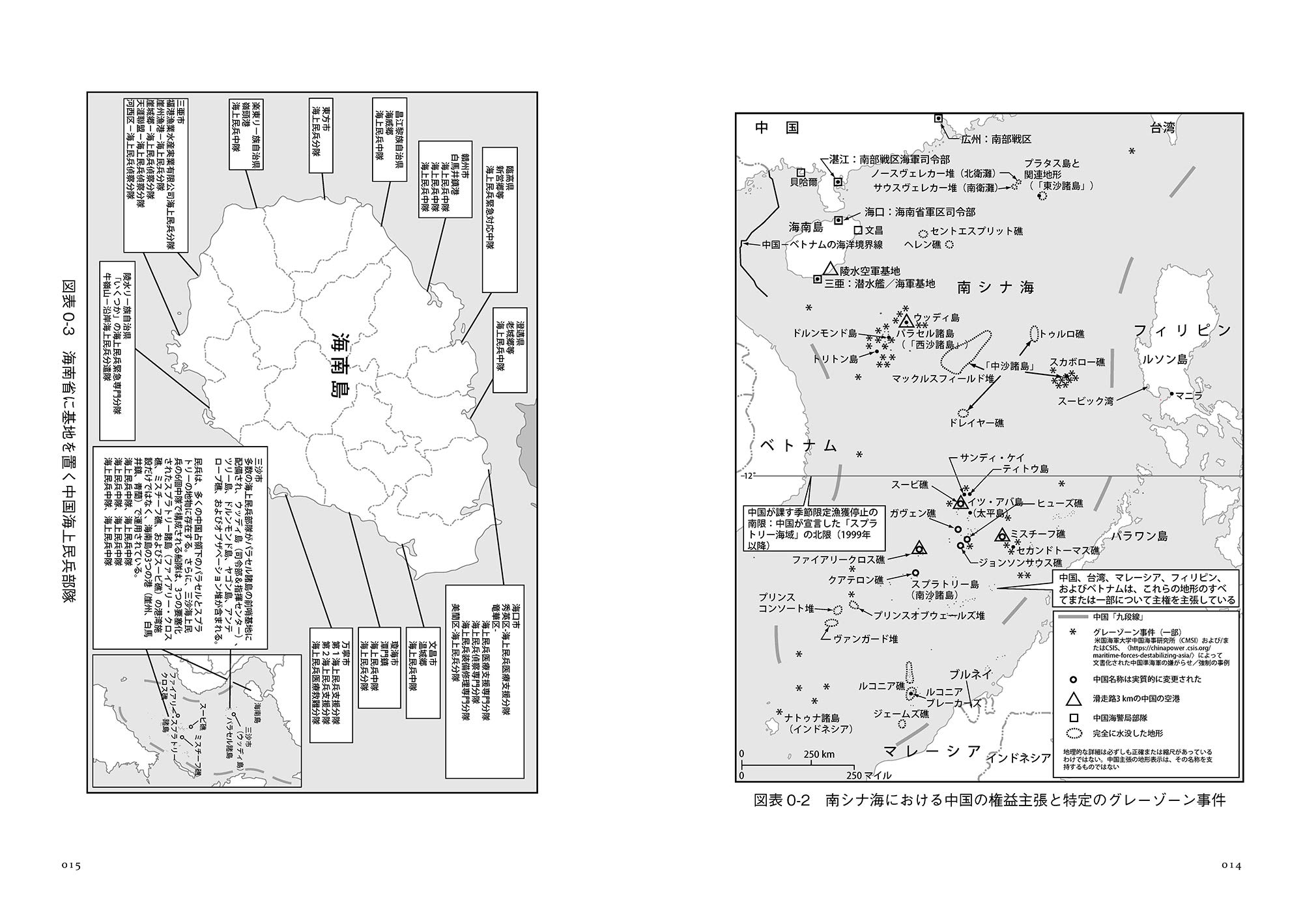

- Possible CMM near Natunas—ambition to expand ops

- “These operations traditionally take place within the FIC along China’s coast and near disputed features in the SCS such as the Second Thomas Shoal, Scarborough Reed, and Luconia Shoal. However, the presence of possible CMM vessels mixed in with Chinese fishing vessels near Indonesia’s Natuna Island outside of the “nine-dashed line” on Chinese maps indicated a possible ambition to expand CMM operations within the region.”

- Often supplement CCG cutters at forefront of incident

- 2021.09-2022.09: Iroquois Reef

- 2020 West Capella

- 1950s offshore island campaigns

- Occupation of Mischief Reef 1994

- “CMM units have been active for decades in incidents and combat operations throughout China’s [!!] near seas and in these incidents CMM vessels are often used to supplement CCG cutters at the forefront of the incident, giving the Chinese the capacity to outweigh and outlast rival claimants. From September 2021 to September 2022, maritime militia vessels were a constant presence near Iroquois Reef in the Spratly Islands within the Philippines EEZ. Other notable examples include standoffs with the Malaysia drill ship West Capella (2020), defense of China’s HYSY-981 drill rig in waters disputed with Vietnam (2014), occupation of Scarborough Reef (2012), and harassment of USNS Impeccable and Howard O. Lorenzen (2009 and 2014). Historically, the maritime militia also participated in China’s offshore island campaigns in the 1950s, the 1974 seizure of the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam, the occupation of Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands in 1994.”

CHINA’S MARITIME MILITIA

China’s Maritime Militia (CMM) is a subset of the PRC’s national militia, an armed reserve force of civilians available for mobilization that is ultimately subordinate to the CMC through the National Defense Mobilization Department. Throughout China, militia units organize around towns, villages, urban sub-districts, and enterprises and vary widely in composition and mission.

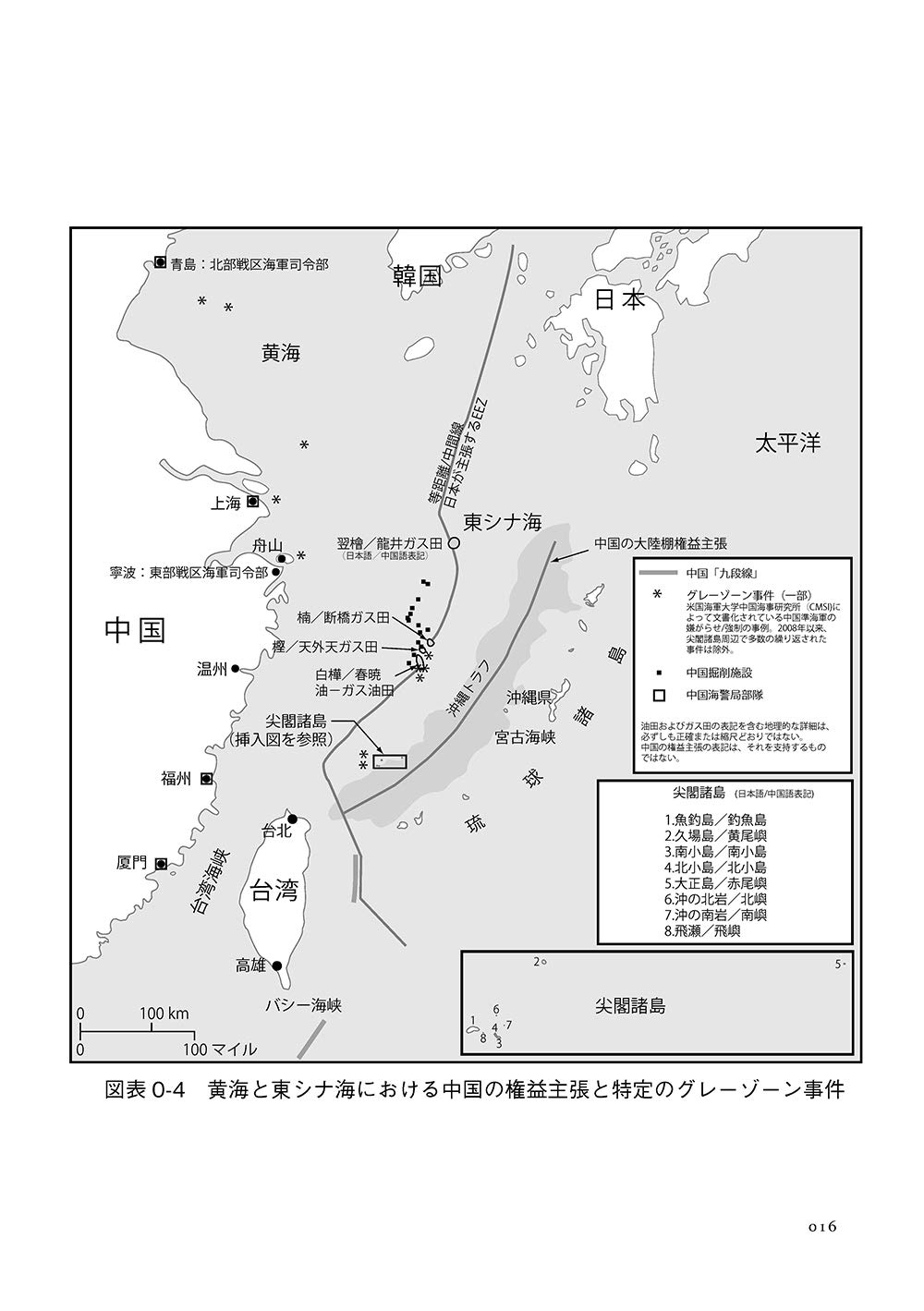

CMM vessels train with and assist the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and the China Coast Guard (CCG) in tasks such as safeguarding maritime claims, surveillance and reconnaissance, fisheries protection, logistics support, and search and rescue. These operations traditionally take place within the FIC along China’s coast and near disputed features in the SCS such as the Second Thomas Shoal, Scarborough Reed, and Luconia Shoal. However, the presence of possible CMM vessels mixed in with Chinese fishing vessels near Indonesia’s Natuna Island outside of the “nine-dashed line” on Chinese maps indicated a possible ambition to expand CMM operations within the region. The PRC employs the CMM in gray zone operations, or “low-intensity maritime rights protection struggles,” at a level designed to frustrate effective response by the other parties involved. The PRC employs CMM vessels to advance its disputed sovereignty claims, often amassing them in disputed areas throughout the SCS and ECS. In this manner, the CMM plays a major role in coercive activities to achieve the PRC’s political goals without fighting and these operations are part of broader Chinese military theory that sees confrontational operations short of war as an effective means of accomplishing strategic objectives.

CMM units have been active for decades in incidents and combat operations throughout [the] near seas and in these incidents CMM vessels are often used to supplement CCG cutters at the forefront of the incident, giving the Chinese the capacity to outweigh and outlast rival claimants. From September 2021 to September 2022, maritime militia vessels were a constant presence near Iroquois Reef in the Spratly Islands within the Philippines EEZ. Other notable examples include standoffs with the Malaysia drill ship West Capella (2020), defense of China’s HYSY-981 drill rig in waters disputed with Vietnam (2014), occupation of Scarborough Reef (2012), and harassment of USNS Impeccable and Howard O. Lorenzen (2009 and 2014). Historically, the maritime militia also participated in China’s offshore island campaigns in the 1950s, the 1974 seizure of the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam, the occupation of Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands in 1994.

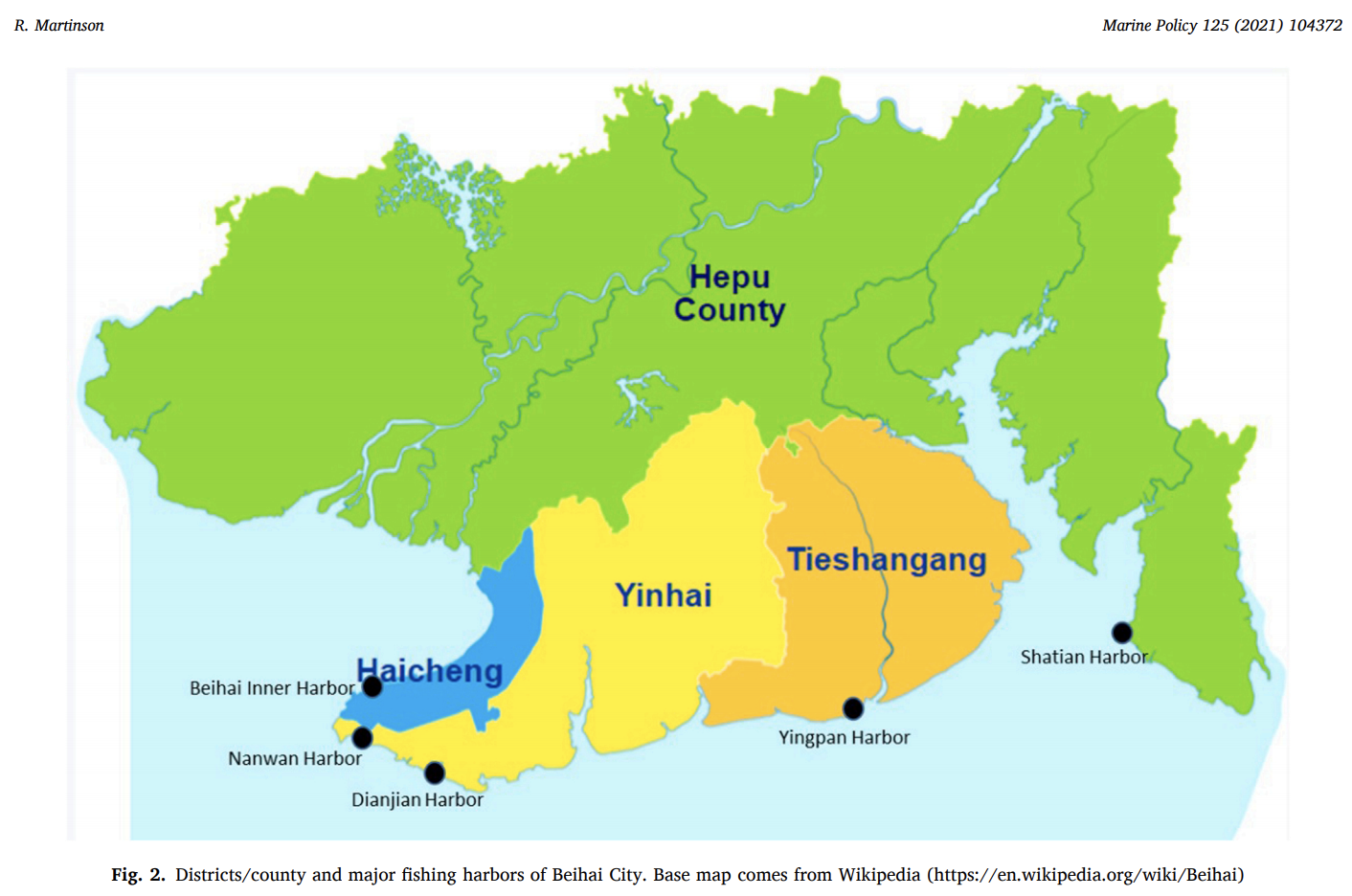

The CMM also protects and facilitates Chinese fishing vessels operating in disputed waters. From late December 2019 to mid-January 2020, a large fleet of over 50 Chinese fishing vessels operated under the escort of multiple China Coast Guard patrol ships in Indonesian claimed waters northeast of the Natuna Islands. At least a portion of the Chinese ships in this fishing fleet were affiliated with known traditional maritime militia units, including a maritime militia unit based out of Beihai City in Guangxi province. While most traditional maritime militia units operating in the SCS

[continued on next page after text box below]

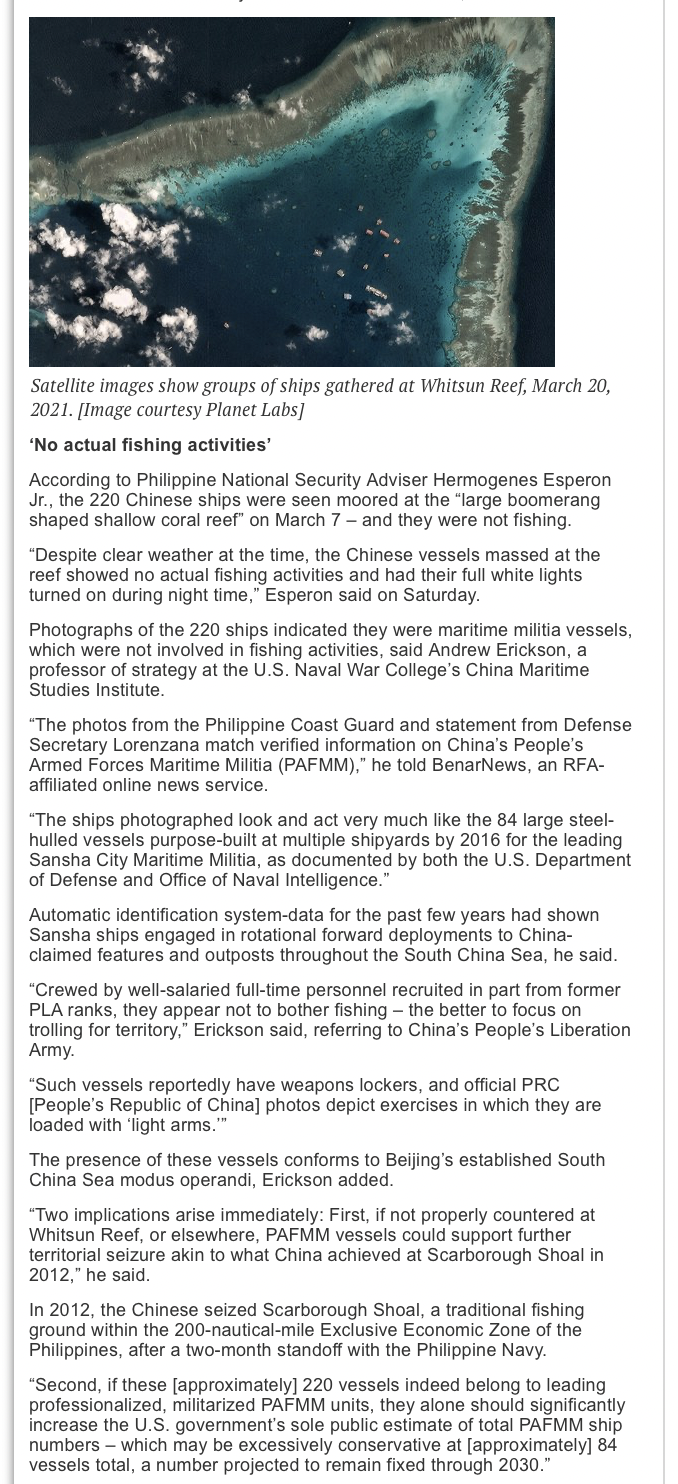

CMM AND LAND RECLAMATION IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

Since at least 2014, CMM vessels have engaged in covert small scale reclamation activity and likely caused physical changes observed at multiple unoccupied features in the Spratly Islands, including Lankiam Cay, Eldad Reef, Sandy Cay, and Whitsun Reef. Beijing likely is attempting to covertly alter these features so that it can portray them as naturally formed high tide elevations capable of supporting PRC maritime claims out to the farthest extent of the nine-dash line. In contrast to the PRC large-scale reclamation program, which was overt and where the original status of occupied features is well documented, the less well-known historical record about many of the unoccupied features makes them more susceptible to PRC efforts to shape international opinion regarding the status of the features.

p. 81

- Beihai MM: mainland based, to Spratlys/Southern SCS

- From 2014: new Spratly backbone fleet from major CMM units in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan.

- With 235 or more large steel hulls; many >50 m, >500 tons.

- Deploy to disputed Spratly waters below 12 degrees North.

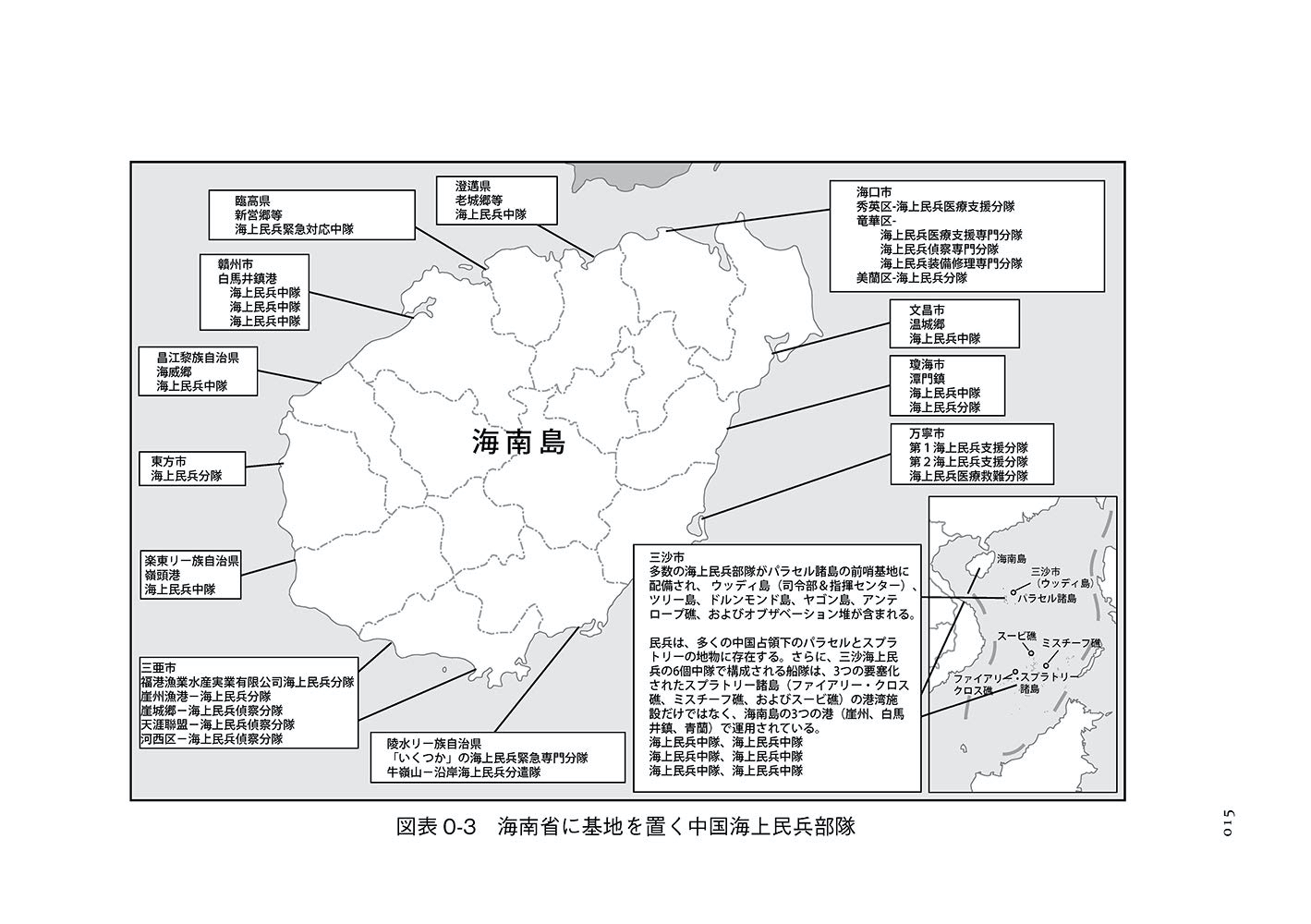

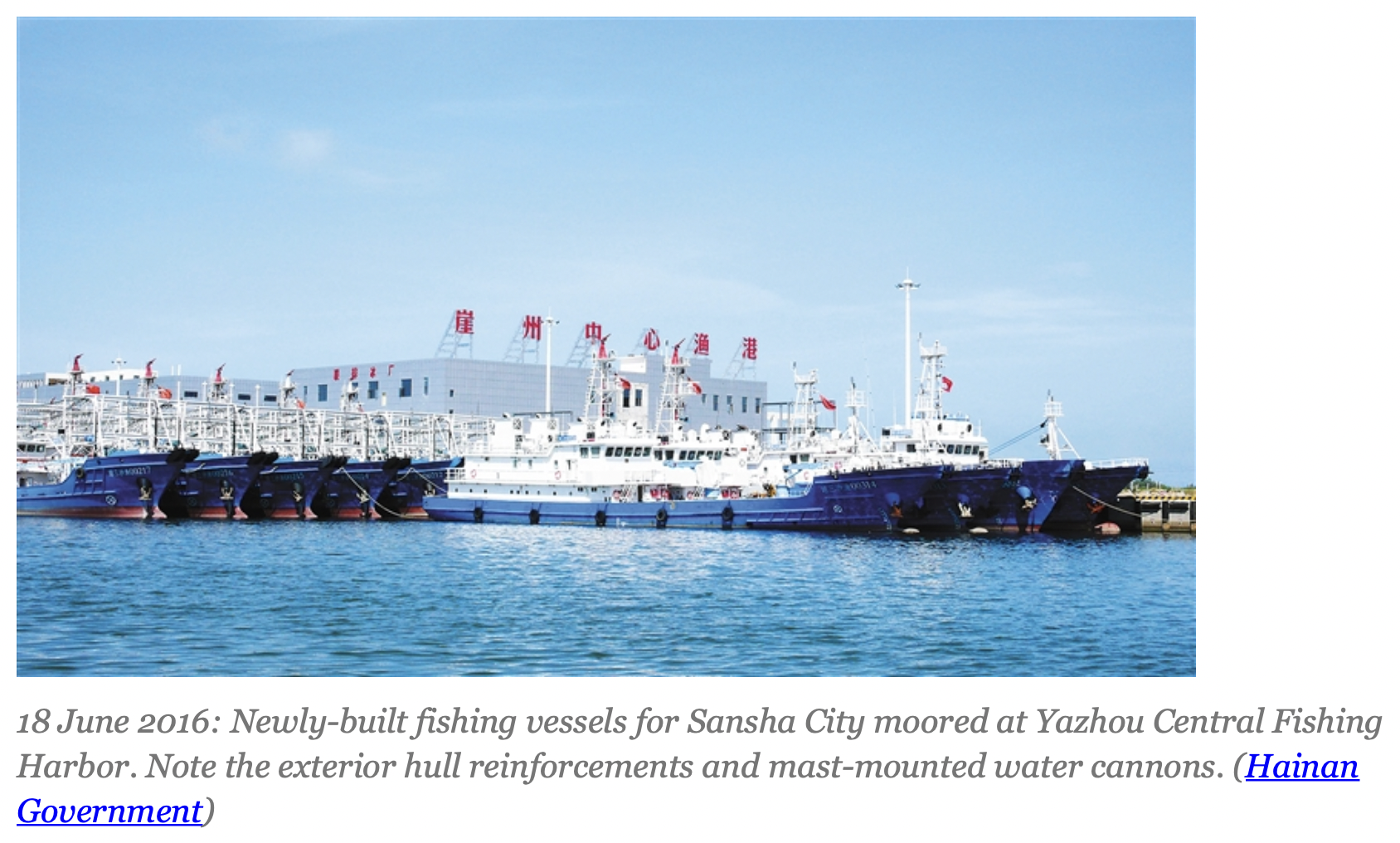

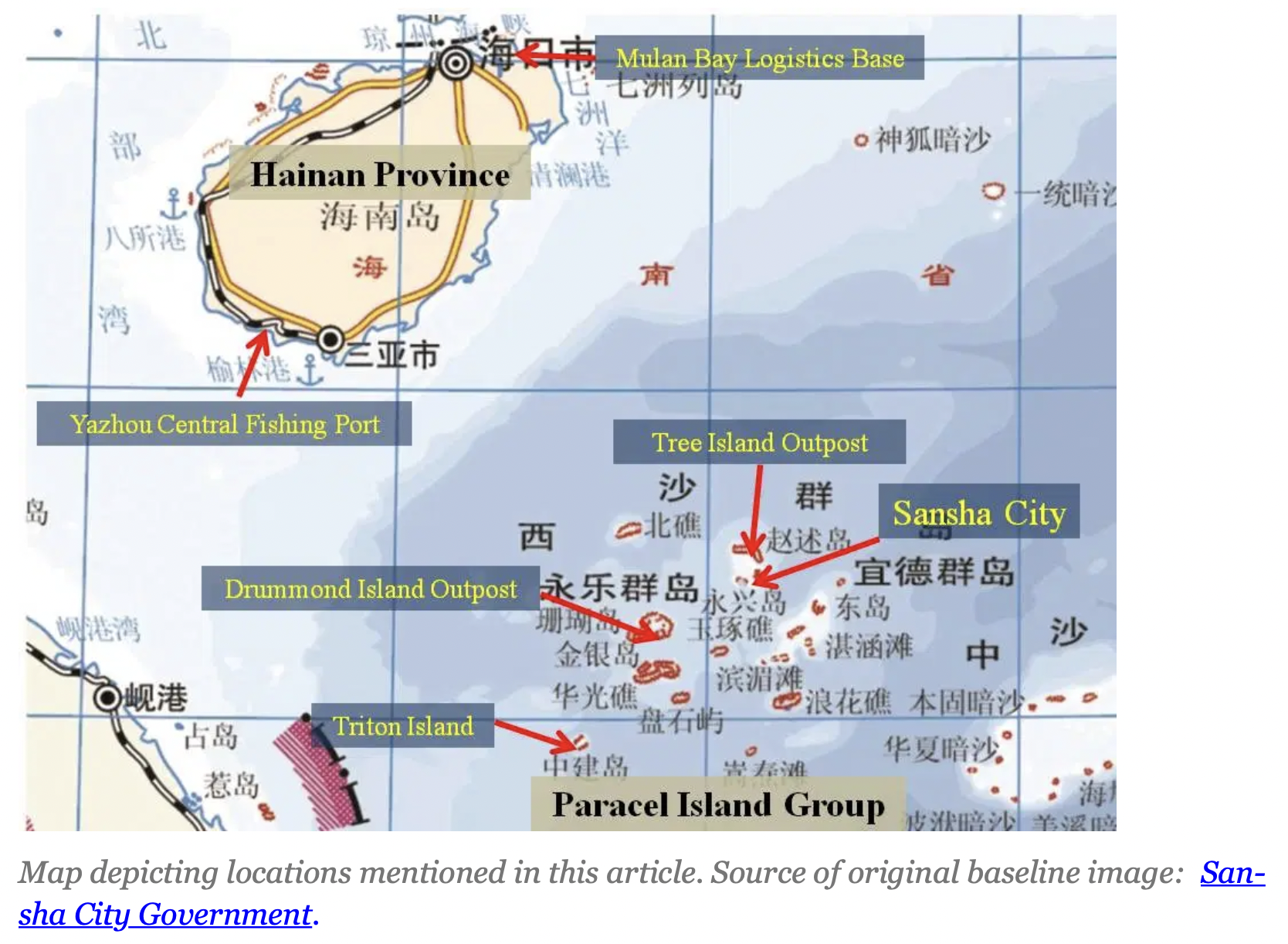

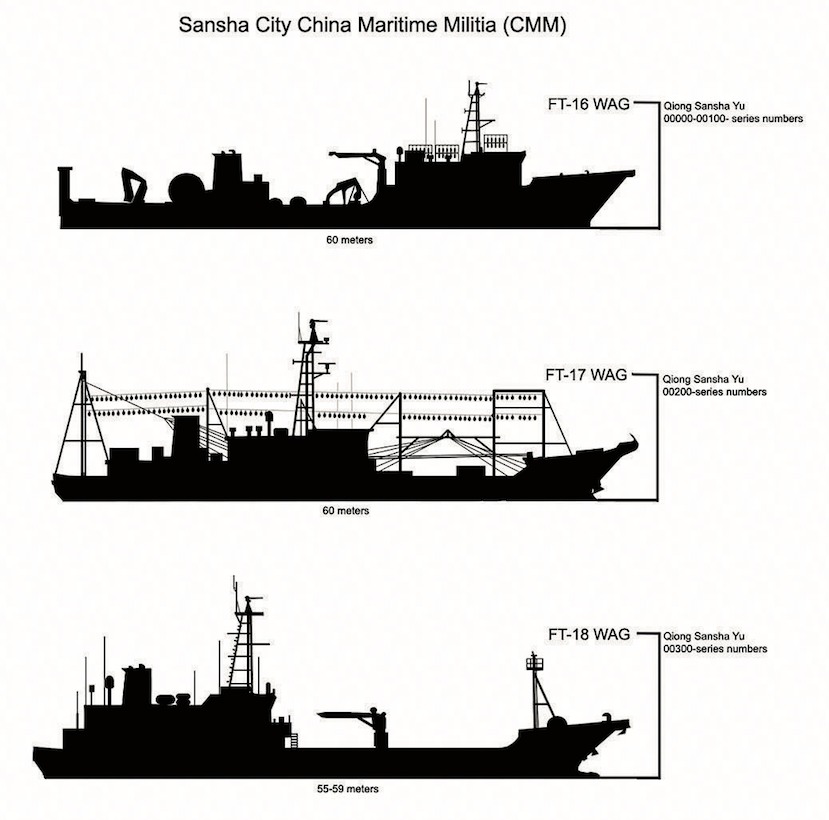

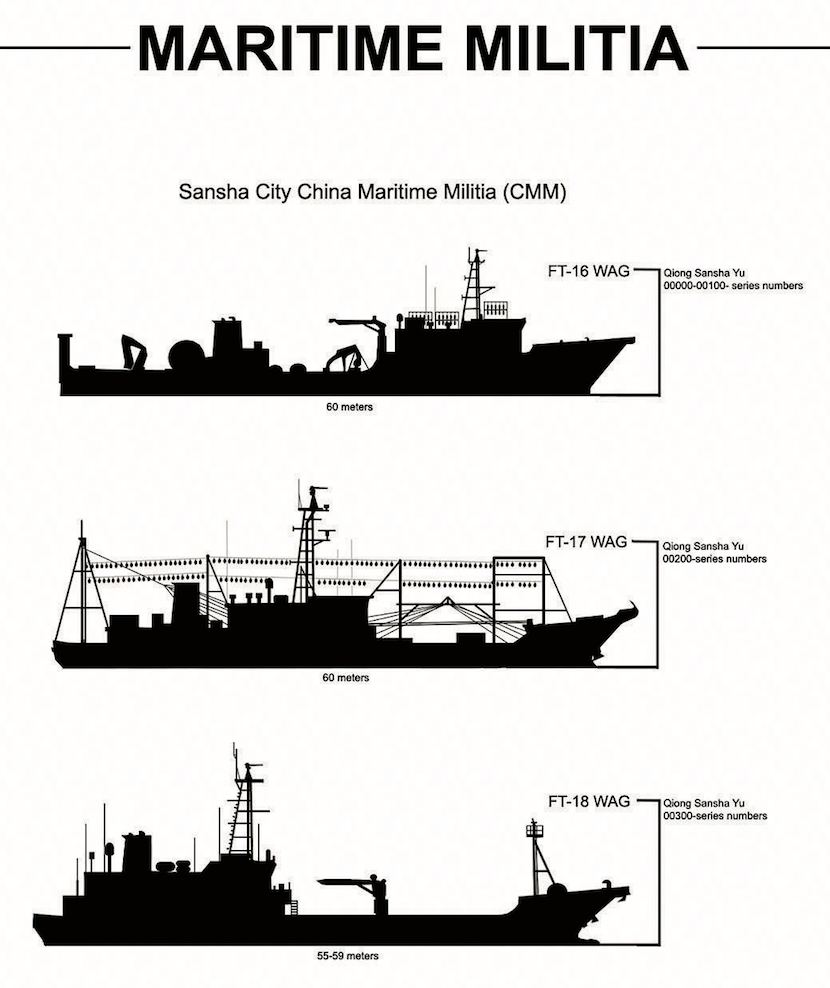

- Sansha MM—light arms

- “Starting in 2015, the Sansha City Maritime Militia in the Paracel Islands has been developed into a salaried full-time maritime militia force with its own command center and equipped with at least 84 purpose-built vessels armed with mast-mounted water cannons for spraying and reinforced steel hulls for ramming. Freed from their normal fishing responsibilities, Sansha City Maritime Militia personnel – many of whom are former PLAN and CCG sailors – train for peacetime and wartime”

continue to originate from townships and ports on Hainan Island, Beihai is one of a number of increasingly prominent maritime militia units based out of provinces in mainland China. These mainland based maritime militia units routinely operate in the Spratly Islands and in the southern SCS, and their operations in these areas are enabled by increased funding from the Chinese government to improve their maritime capabilities and grow their ranks of personnel.

Through the National Defense Mobilization Department, Beijing subsidizes various local and provincial commercial organizations to operate CMM vessels to perform “official” missions on an ad hoc basis outside of their regular civilian commercial activities. CMM units employ marine industry workers, usually fishermen, as a supplement to the PLAN and the CCG. While retaining their day jobs, these mariners are organized and trained, often by the PLAN and the CCG, and can be activated on demand.

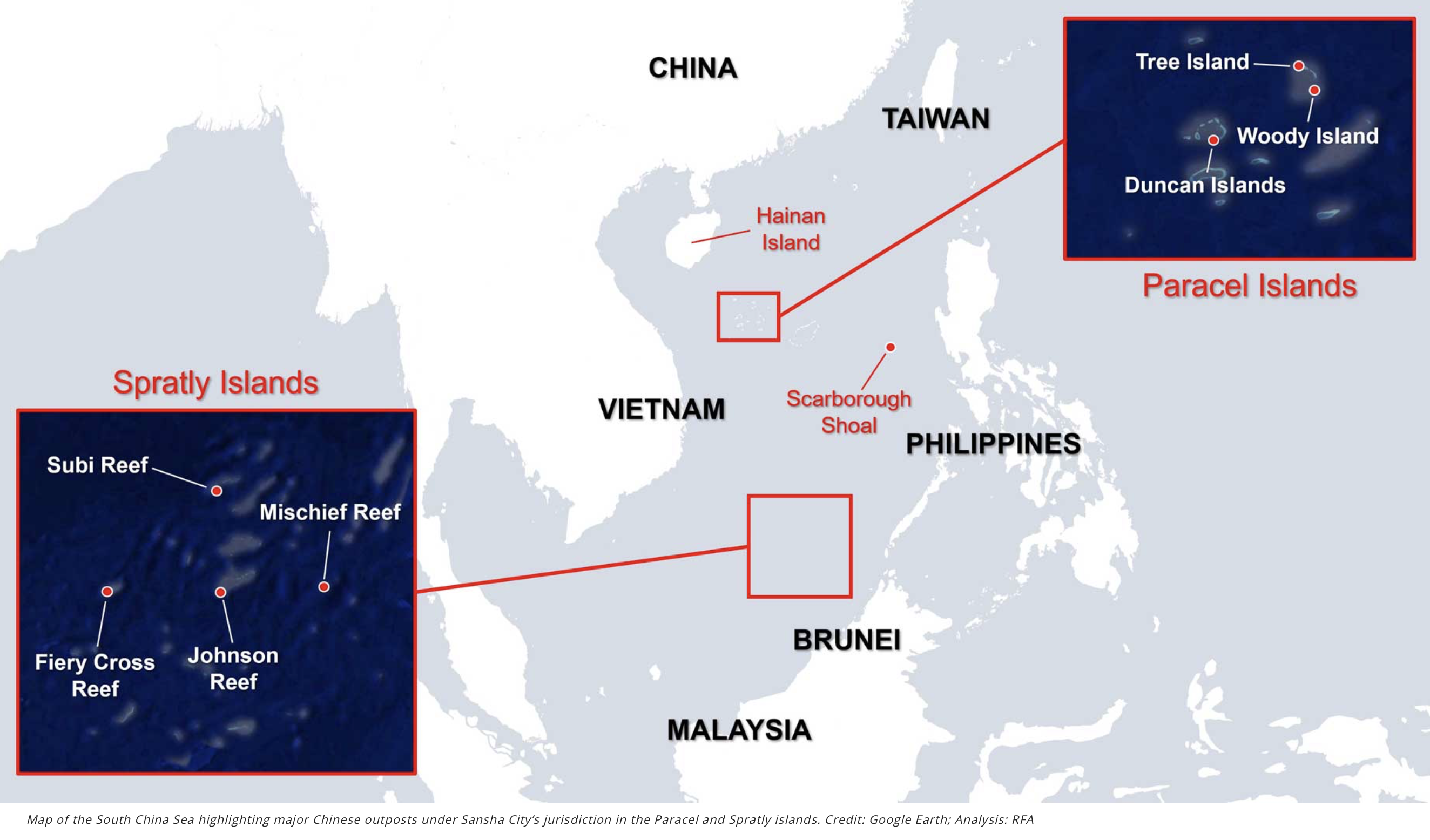

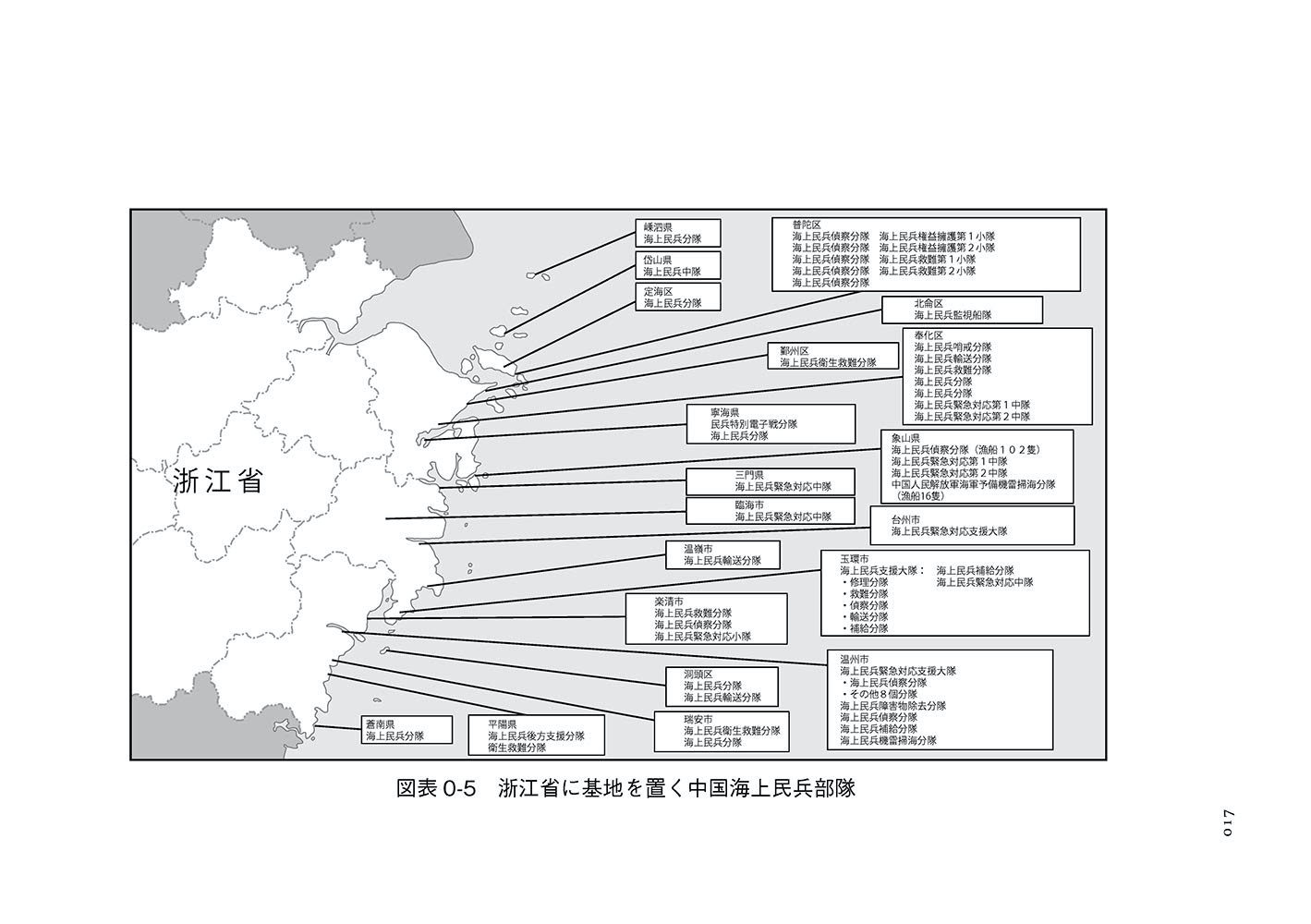

Since 2014, China has built a new Spratly backbone fleet comprising at least 235 large steel-hulled fishing vessels, many longer than 50 meters and displacing more than 500 tons. These vessels were built under central direction from the PRC government to operate in disputed areas south of 12 degrees latitude that China typically refers to as the “Spratly Waters,” including the Spratly Islands and southern SCS. Spratly backbone vessels were built for prominent CMM units in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan Provinces. For vessel owners not already affiliated with CMM units, joining the militia was a precondition for receiving government funding to build new Spratly backbone boats. As with the CCG and PLAN, new facilities in the Paracel and Spratly Islands enhance the CMM’s ability to sustain operations in the SCS.

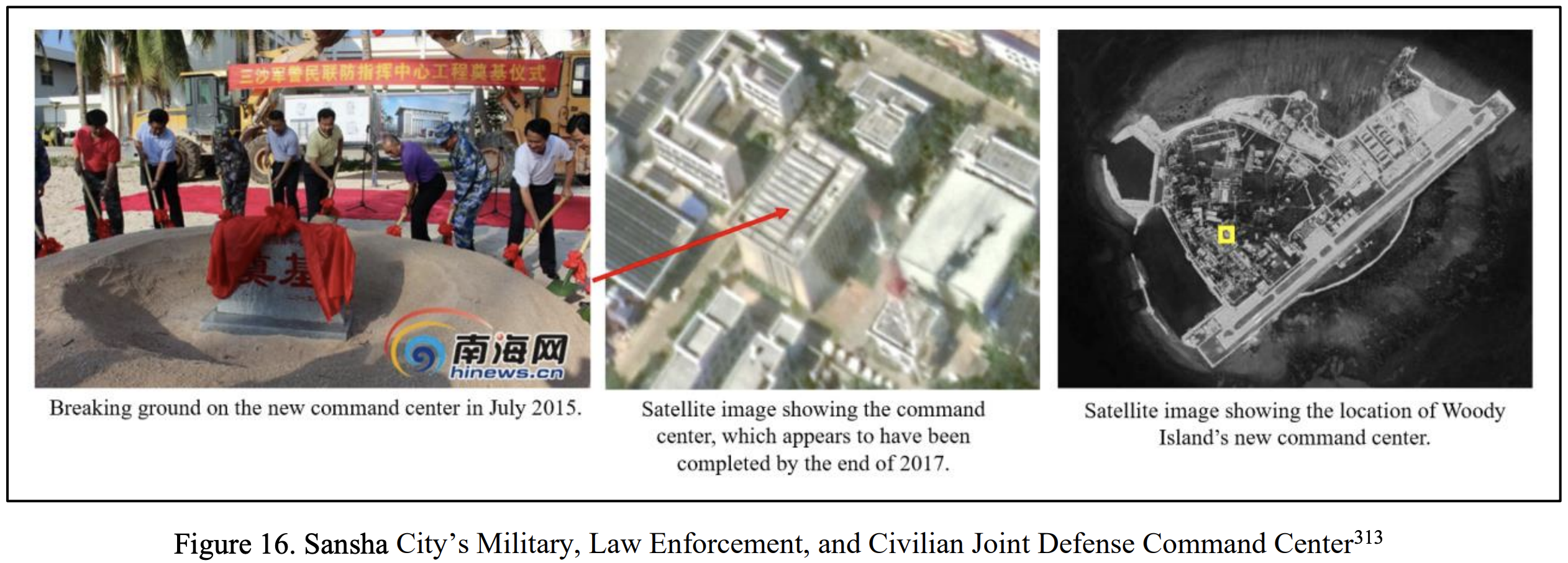

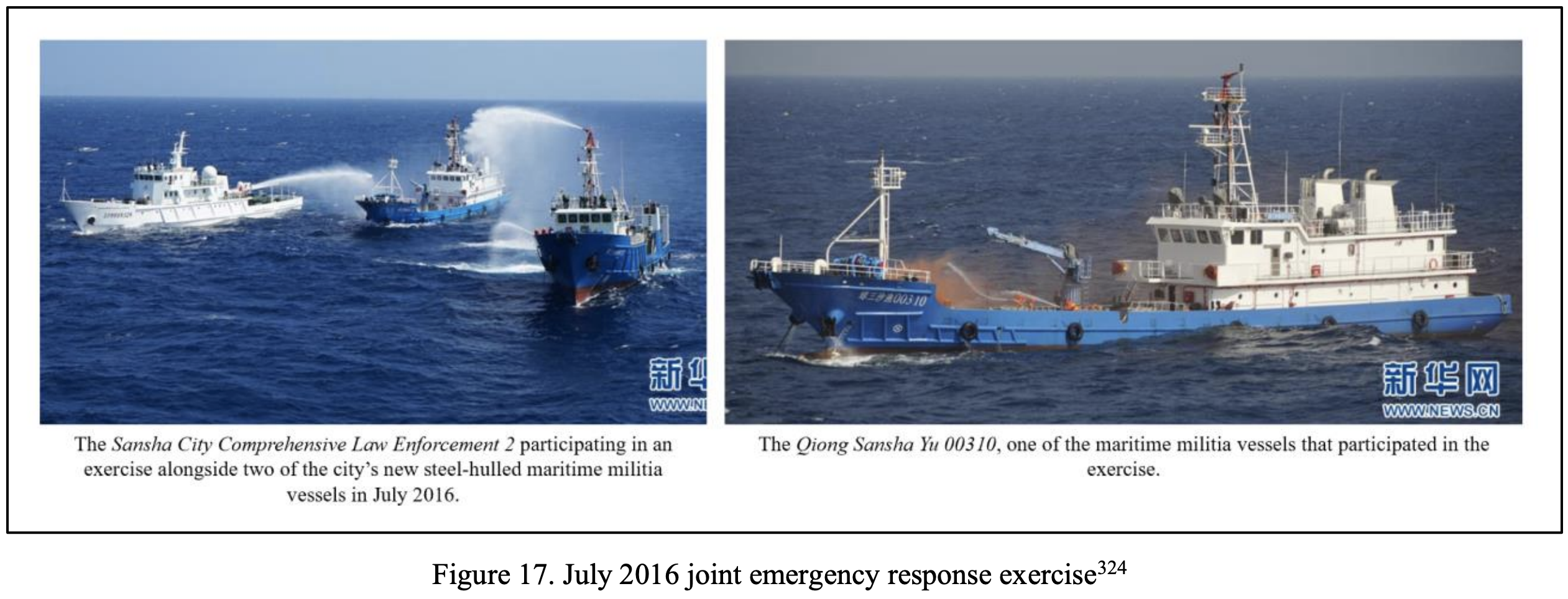

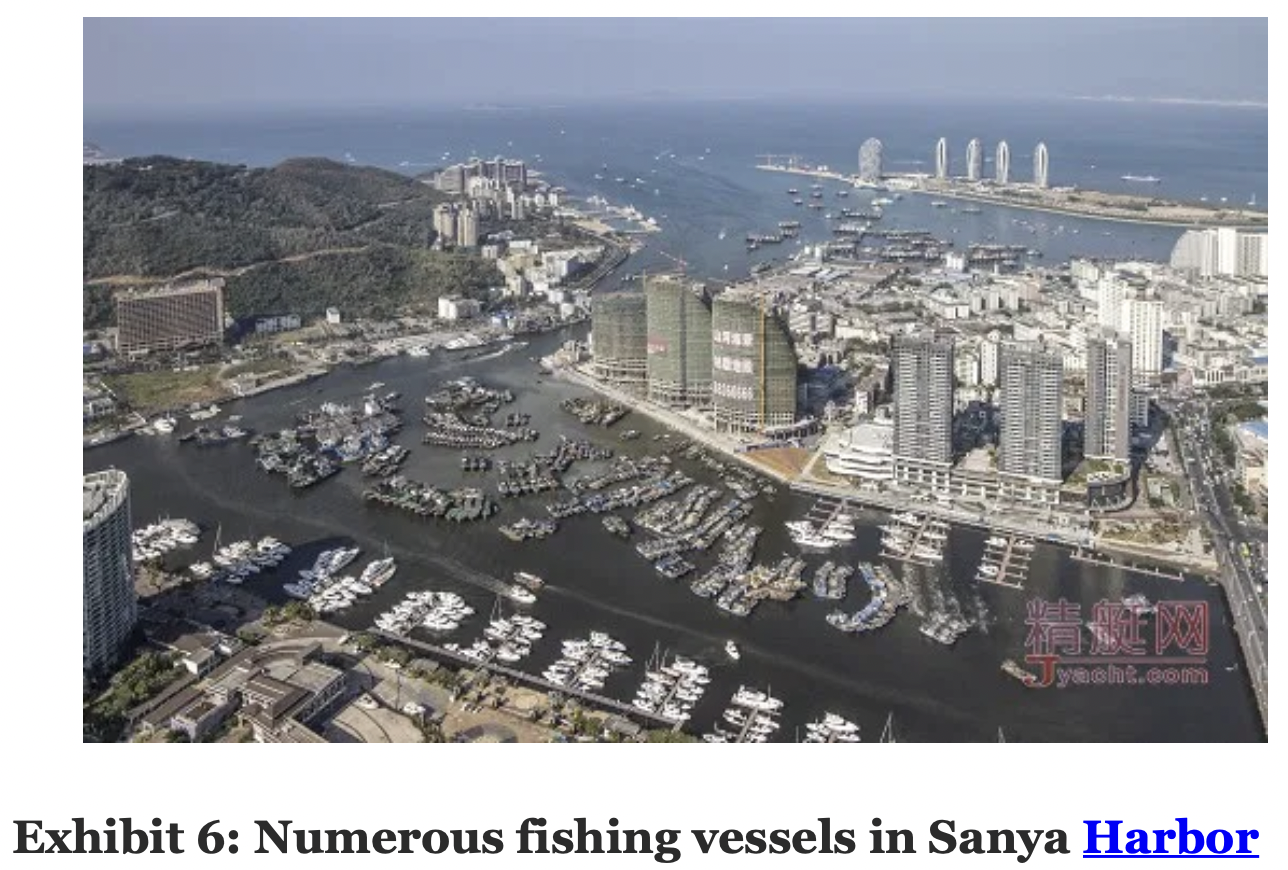

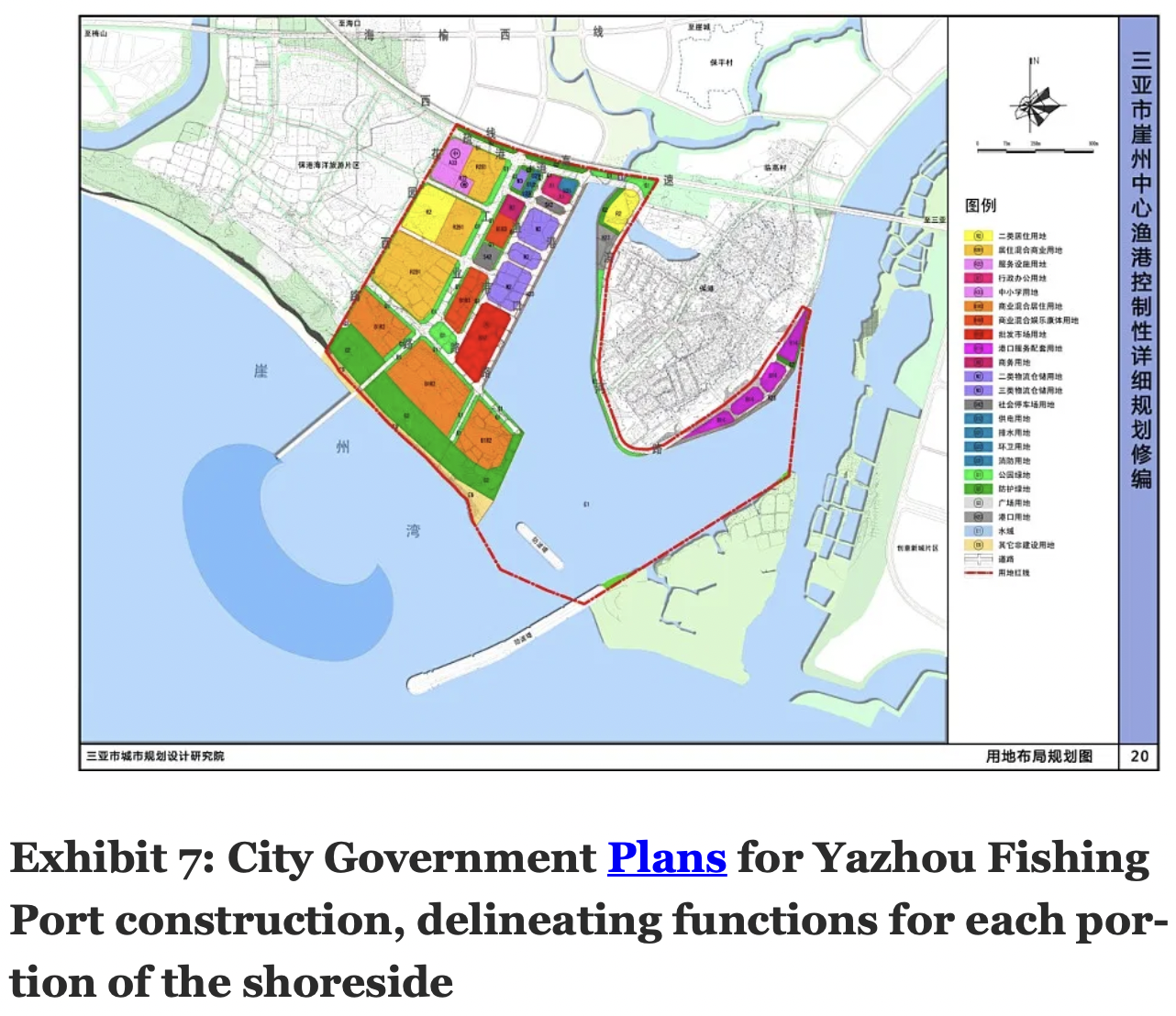

Starting in 2015, the Sansha City Maritime Militia in the Paracel Islands has been developed into a salaried full-time maritime militia force with its own command center and equipped with at least 84 purpose-built vessels armed with mast-mounted water cannons for spraying and reinforced steel hulls for ramming. Freed from their normal fishing responsibilities, Sansha City Maritime Militia personnel – many of whom are former PLAN and CCG sailors – train for peacetime and wartime

p. 82

- Sansha MM—light arms

- “contingencies, often with light arms, and patrol regularly around disputed South China Sea features even during fishing moratoriums.

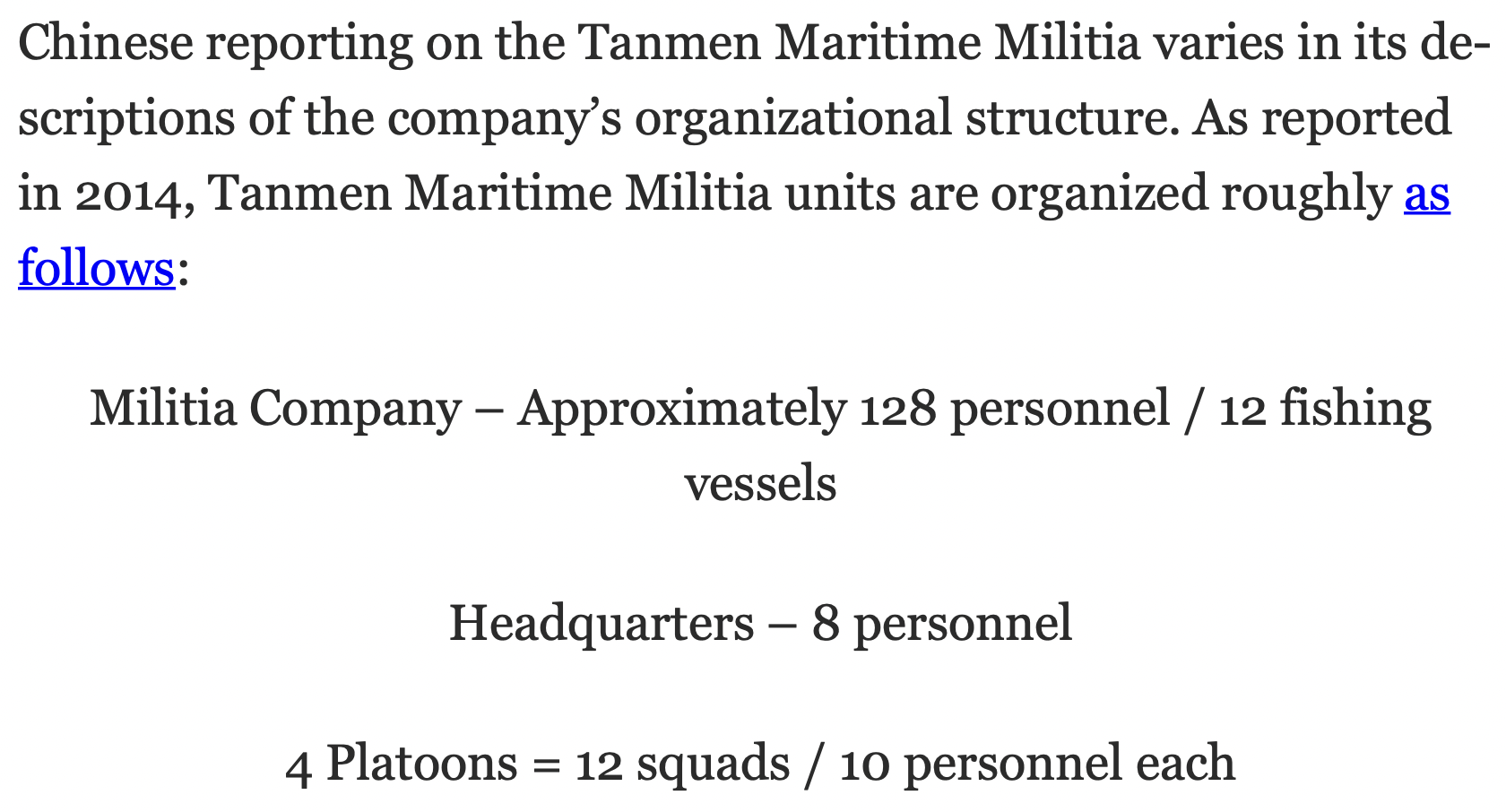

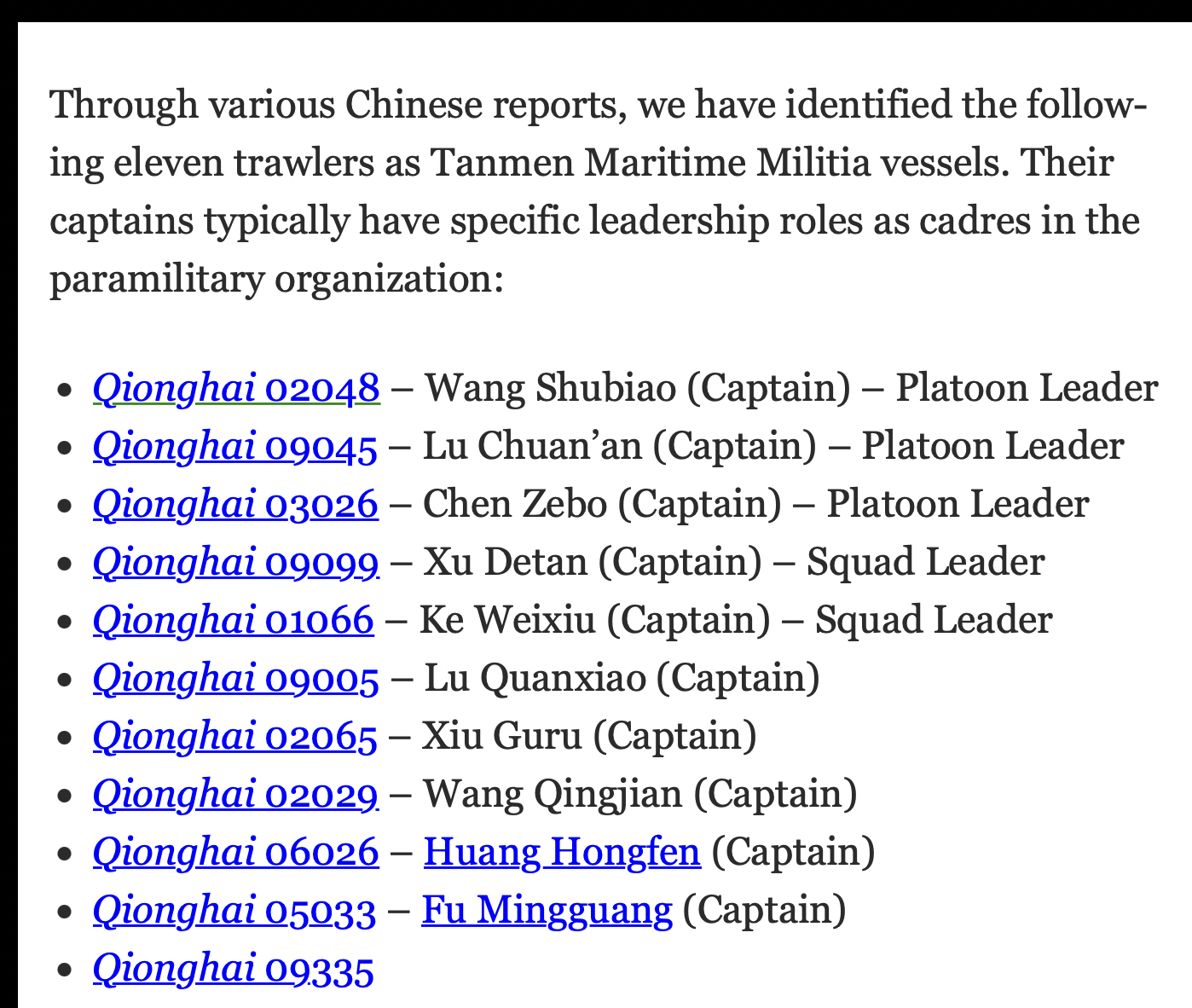

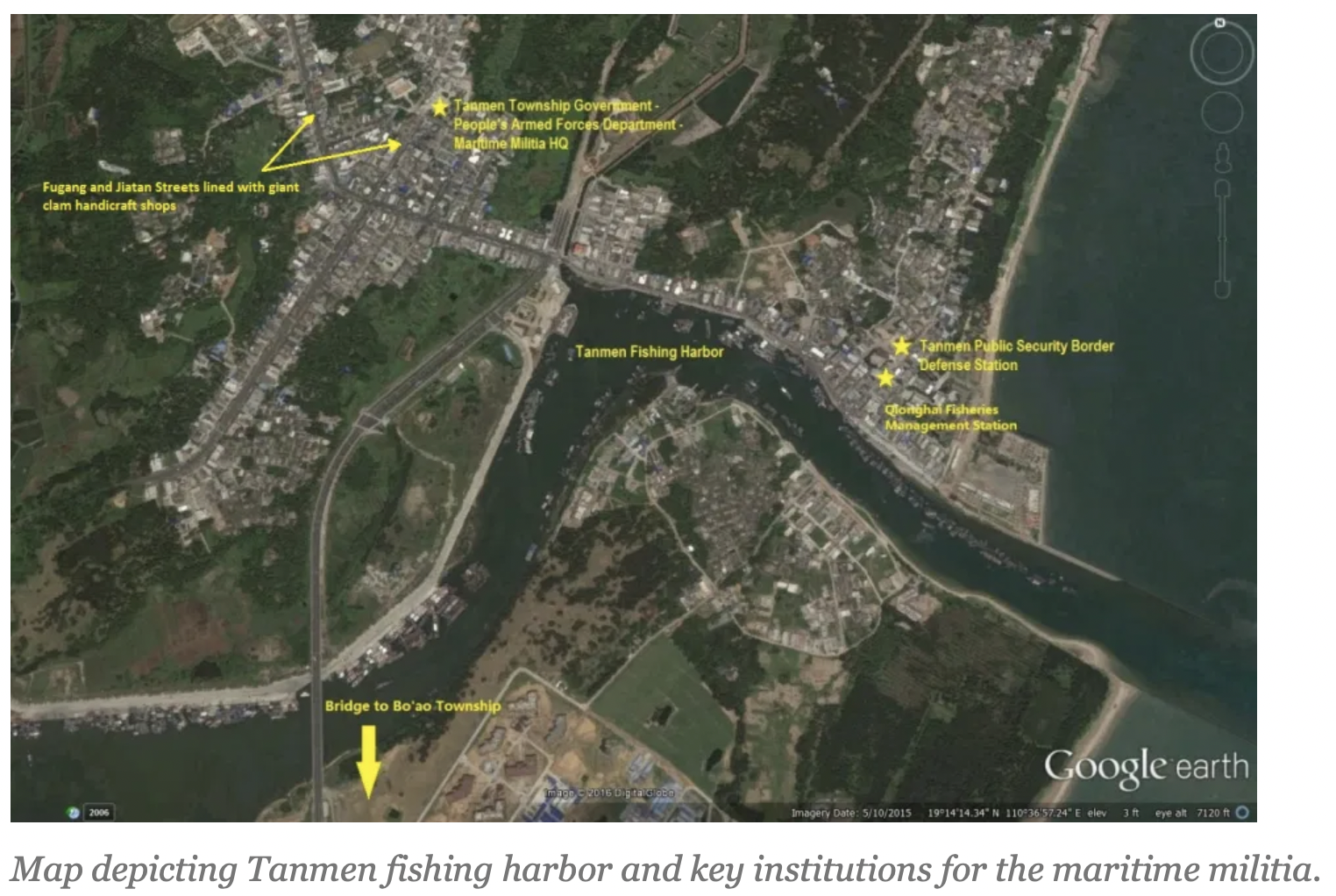

- Tanmen MM—Xi: support SCS “island and reef development”

- 1989-95 under SSF authority

- Occupation/reclamation of PRC Spratly outposts: Subi, Fiery Cross, Mischief

- “The Tanmen Maritime Militia is another prominent CMM unit. Homeported in Tanmen township on Hainan Island, the formation was described by Xi as a “model maritime militia unit” during a visit to Tanmen harbor in 2013. During the visit, Xi encouraged Tanmen to support “island and reef development” in the SCS. Between 1989 and 1995, the Tanmen Maritime Militia, under the authority of the PLAN Southern Theater Navy (then the South Sea Fleet), was involved in the occupation and reclamation of PRC outposts in the Spratly Islands, including Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, and Mischief Reef.”

contingencies, often with light arms, and patrol regularly around disputed South China Sea features even during fishing moratoriums.

The Tanmen Maritime Militia is another prominent CMM unit. Homeported in Tanmen township on Hainan Island, the formation was described by Xi as a “model maritime militia unit” during a visit to Tanmen harbor in 2013. During the visit, Xi encouraged Tanmen to support “island and reef development” in the SCS. Between 1989 and 1995, the Tanmen Maritime Militia, under the authority of the PLAN Southern Theater Navy (then the South Sea Fleet), was involved in the occupation and reclamation of PRC outposts in the Spratly Islands, including Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, and Mischief Reef.

p. 119

ETC likely commands all CCG/MM ships conducting ops re Senkakus

“The Eastern Theater Command…likely commands all CCG and maritime militia ships while they are conducting operations related to the ongoing dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands.”

p. 121

ECS

Fishing/MM vessels, CCG escorts, PLAN overwatch

“The PRC attempts to legitimize its claims in the ECS through the continuous presence of PRC fishing and Maritime Militia vessels, escorted by CCG cutters and with PLA Navy warships nearby as overwatch.”

p. 122

STC

Track/react to U.S. ships operating within Nine-Dashed Line

“The Southern Theater Command is responsible for responding to U.S. freedom of navigation operations in the SCS by regularly tracking and reacting to U.S. ships operating within the China-claimed “nine-dash line.””

Can assume command as needed over ALL CCG/CMM ships operating within 9DL

“can assume command as needed over all CCG and CMM ships conducting operations within the PRC’s claimed “nine-dash line.””

p. 125

SCS

- 2022 deployed PLAN/CCG/civilian ships:

- Presence near Scarborough, Thitu

- Respond to oil/gas exploration within 9DL

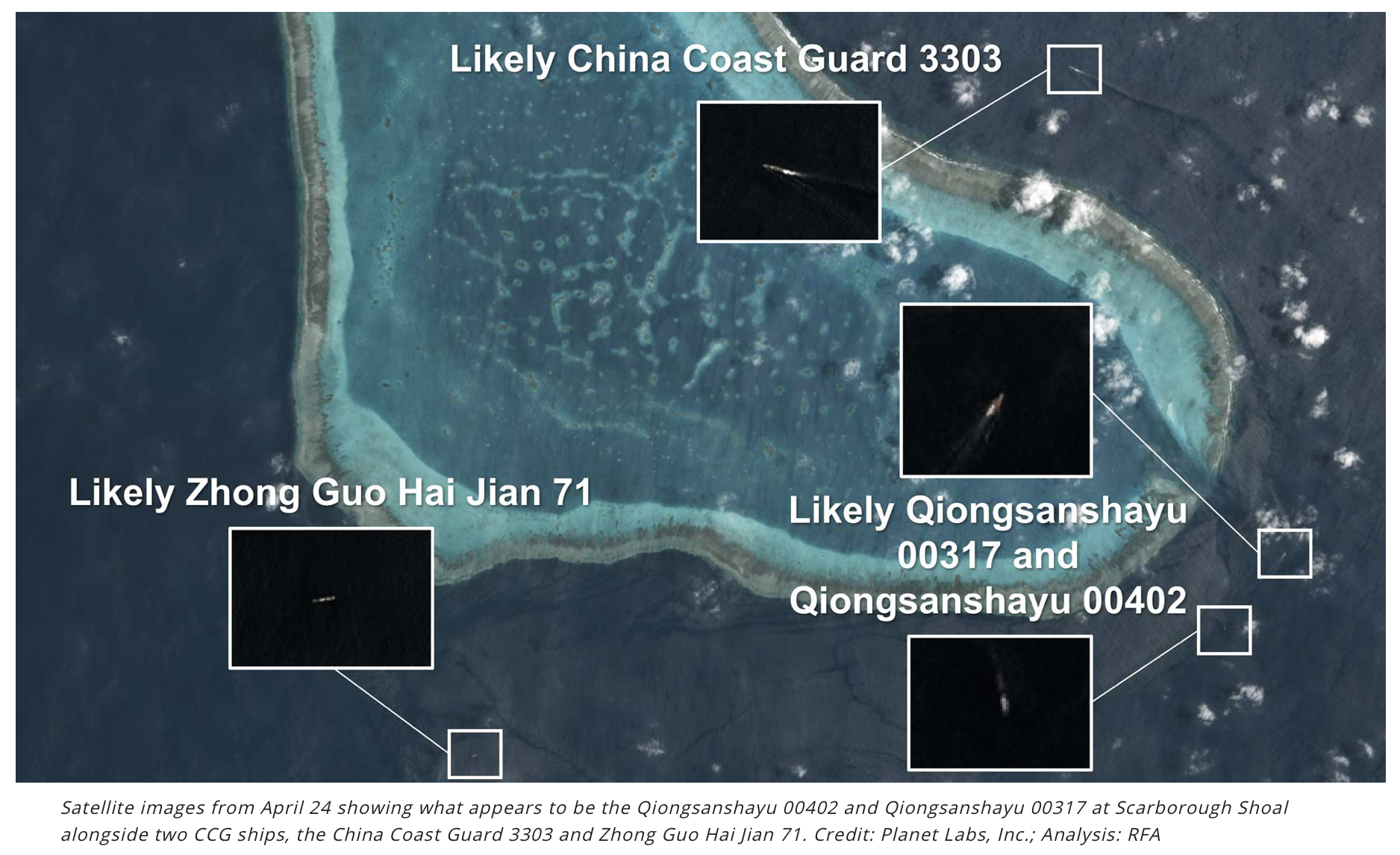

- CCG/PAFMM used nets/ropes to block Philippine supply boats

- “the CCG and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) used nets and ropes to block Philippine supply boats on their way to an atoll in the SCS and issued radio challenges and threats to Philippine ships during routine resupply missions.”

- “The PRC states that international military presence within the SCS is a challenge to its sovereignty. Throughout 2022, the PRC deployed PLAN, CCG, and civilian ships to maintain a presence in disputed areas, such as near Scarborough Reef and Thitu Island, as well as in response to oil and gas exploration operations by rival claimants within the PRC’s claimed “nine-dash line.” Separately, the CCG and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) used nets and ropes to block Philippine supply boats on their way to an atoll in the SCS and issued radio challenges and threats to Philippine ships during routine resupply missions.”

- 2022.11 CCG cut tow line of Philippine Navy vessel, seized PRC rocket debris

- “In November 2022, a CCG vessel forcibly seized apparent PRC rocket debris that had fallen near Philippine-occupied Thitu Island from the Philippines by cutting the tow line of a Philippine Navy vessel as it was towing debris back to shore. PRC insisted the debris was returned to them after a “friendly negotiation,” despite the Philippines producing video evidence of the incident and issues diplomatic notes of protest.”

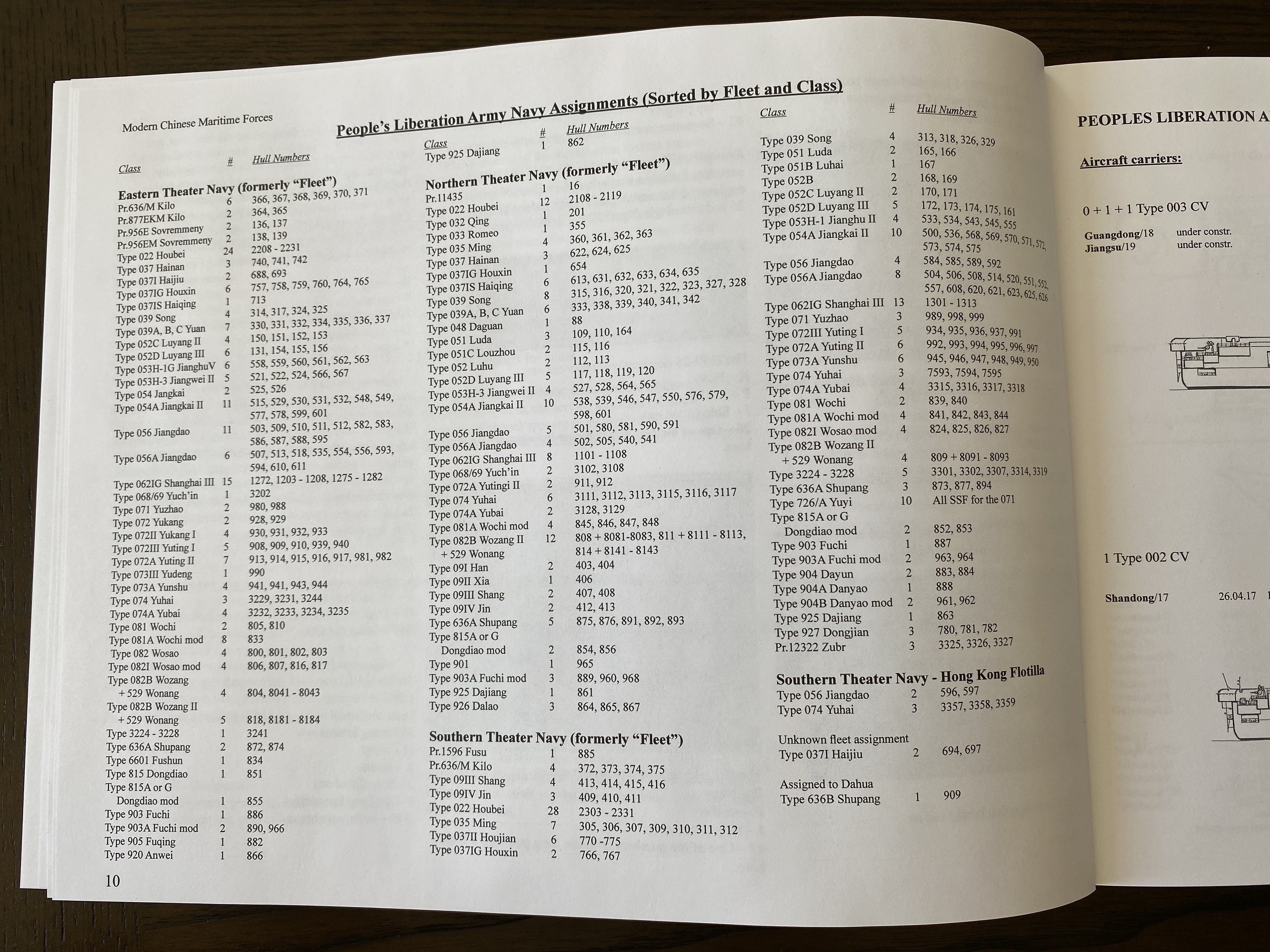

As we enter 2024, China under Xi is steaming full speed ahead, particularly at sea. Navigate today’s troubled Indo-Pacific waters by consulting the latest version of Modern Chinese Maritime Forces—released today! This most recent iteration of the second edition includes sections for PLA Army (pp. 63–75) and PLA Air Force (pp. 76–78) watercraft; the latest data updates, including regarding nuclear-powered submarines (pp. 20–22); and a variety of new drawings. It is issued in both PDF and print versions.

This is the most comprehensive unclassified, open source PRC sea forces order of battle, data, and ship drawings available anywhere. It tracks the world’s most-numerous Navy, Coast Guard, and Maritime Militia vessels in unrivaled detail. Even just scrolling or flipping through this volume for a minute reveals the staggering scope and extent of Beijing’s sea power across the waterfront today. I simply could not be more honored to contribute a new, improved Foreword that captures China’s latest military maritime superlatives!

Manfred Meyer (edited by Larry Bond and Chris Carlson), Modern Chinese Maritime Forces, Second Edition (Admiralty Trilogy Group, 1 January 2024).

- “A compilation of ships and boats of the Chinese Navy, Coast Guard, Maritime Militia and other state authorities”

- In terms of ship numbers, each of China’s three sea forces is the world’s largest by a large margin. For the scenarios that most concern the U.S. and its regional allies, these numbers matter greatly.

- This suggests an important conclusion: China’s numerical sea force supremacy and the corresponding need for power projection and presence to counter it effectively demonstrates the need for a substantially-sized U.S. Navy. This book can help inform related deliberations and development. All the more reason to consult this handy compendium today!

- Click here to download sample content.

- Conventionally-powered submarine coverage includes entry on the Type 039C Yuan-class SSP (p. 22) and test submarines (p. 24).

- Unique PAFMM ship silhouettes and related information on pp. 129–30! Updated to include Guangdong Province vessels.

- Check out the crane ship coverage on pp. 168–70!

- Ro-Ro ferries are featured on p. 172.

- You can order a copy here.

- The .pdf version is a living document, updated quarterly (1 January, 1 April, 1 July, 1 October of each year) with new drawings, commissionings, decommissionings, and other ship data as it becomes available.

- Single purchase includes access to future periodic updates of the volume.

RELATED PUBLICATIONS

In addition to Modern Chinese Maritime Forces, the Admiralty Trilogy Group also offers a dedicated supplement for Harpoon V regarding PLA Navy, PLA Air Force, China Coast Guard ships and aircraft as well as missiles/weapons and sensors. It is designed as a sourcebook for the game, but can also be used as an unparalleled reference (offering unrivaled coverage from 1955 to the present).

- Larry Bond, Chris Carlson, and Peter Grining, eds., China’s Navy: Ships and Aircraft of the People’s Republic of China, 1955 – 2021 (Admiralty Trilogy Group, 1 October 2021).

Admiralty Trilogy Group similarly offers dedicated sourcebooks for Harpoon V on Russia’s Navy and Military Aircraft, respectively, which likewise double as unique general references.

- Larry Bond, Chris Carlson, and Peter Grining, eds., Russia’s Navy: The Soviet and Russian Navy, 1955 – Present Day (Admiralty Trilogy Group, June 2021).

- Larry Bond, Chris Carlson, and Peter Grining, eds., Russia’s Aircraft: Russian Military Aircraft, 1955 – Present Day (Admiralty Trilogy Group, June 2021).

The Admiralty Trilogy Group (ATG) is pleased to announce that in addition to publishing games supporting its tactical naval game system, the Admiralty Trilogy, it has released its first nonfiction book. Click here to read the announcement.

Modern Chinese Maritime Forces, by Manfred Meyer, a noted artist and illustrator, provides up-to-the minute information on Chinese sea power. It lists all Chinese state vessels – not just the People’s Liberation Army Navy, but the Coast Guard, China Maritime Surveillance, China Fisheries law Enforcement Command, and many other state-sponsored agencies that carry out China’s policies at sea.

Hundreds drawings show everything from aircraft carriers to buoy tenders, accompanied by detailed information on their characteristics. Additional supporting material includes theater navy assignments for individual ships as well as descriptions of the Chinese systems for hull numbers and equipment designations. This compact book has the most complete unclassified information on Chinese state-owned vessels available anywhere.

I am honored to contribute a revised Foreword, in which I write: “Today, China’s maritime forces have the most ships of any nation. This pathbreaking book documents their force structure in unprecedented detail.”

- Andrew S. Erickson, “Foreword,” in Manfred Meyer (edited by Larry Bond and Chris Carlson), Modern Chinese Maritime Forces, Second Edition (Admiralty Trilogy Group, 1 January 2024), 3.

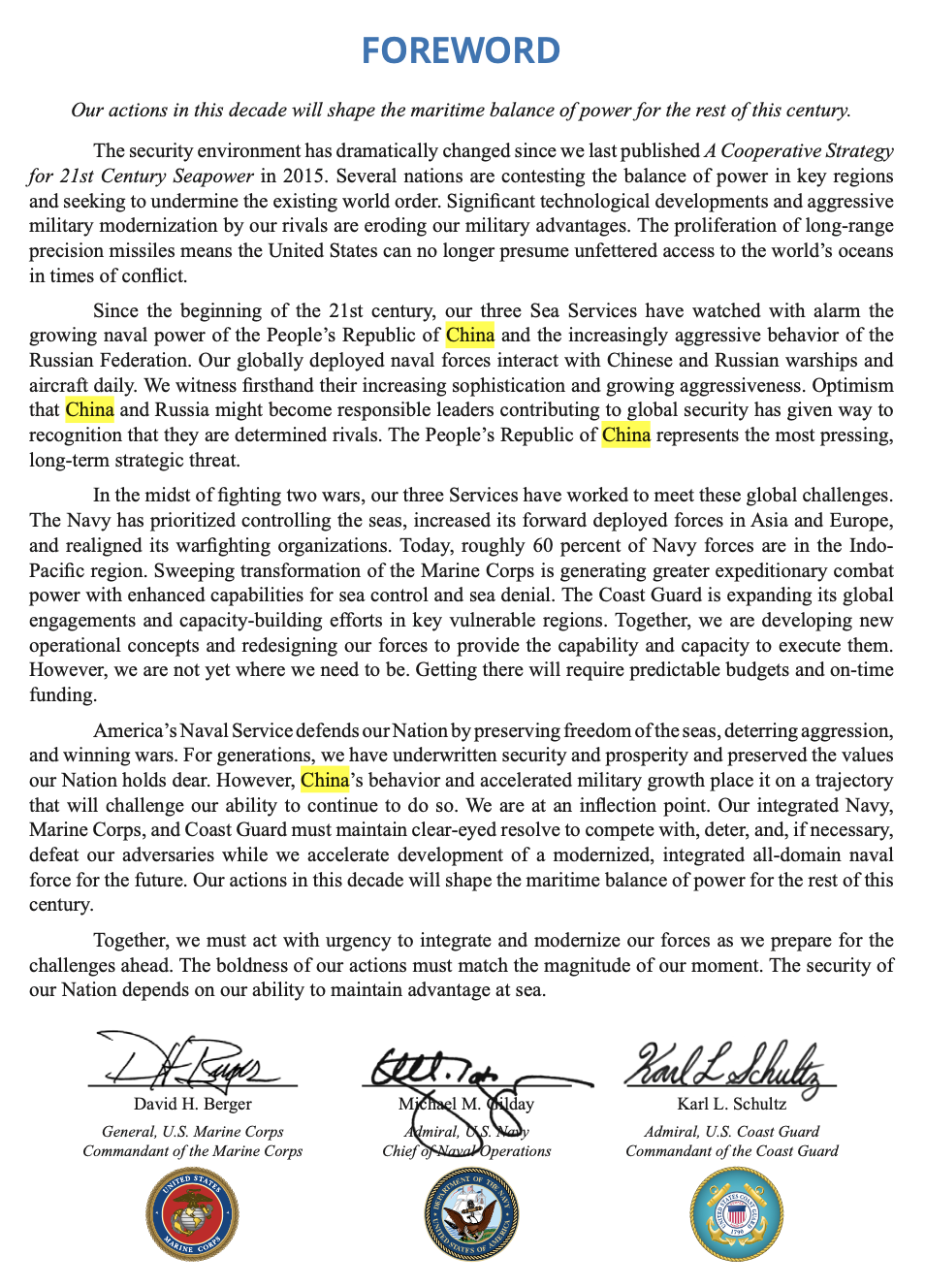

FOREWORD

Ships are the ultimate embodiment of maritime strategy. Today, the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s military maritime forces have the most ships of any nation. This pathbreaking book documents their force structure in unprecedented detail, making it an invaluable reference for all who seek to understand Beijing’s seaward surge and its manifold impacts and implications.

While remaining shackled to geostrategic realities on land and hemmed in by “island chains” surrounding peripheral seas, China has gone to sea dramatically in both commercial and military dimensions. It is arguably the first continental power in two millennia to become a successful hybrid land-sea power and keep that sea change on course. Powered by the world’s second-largest economy and defense budget, the PRC has gone to sea with scale, sophistication, and superlatives that no continental power ever before achieved in the modern era. Living out the dreams of previous generations to truly develop China’s “blue economy,” paramount leader Xi Jinping is personally guiding China’s transformation into a “great maritime power.” Amid European decline and American fiscal and strategic challenges, this historic transformation has the potential to end six centuries of largely Western dominance of the world’s oceans.

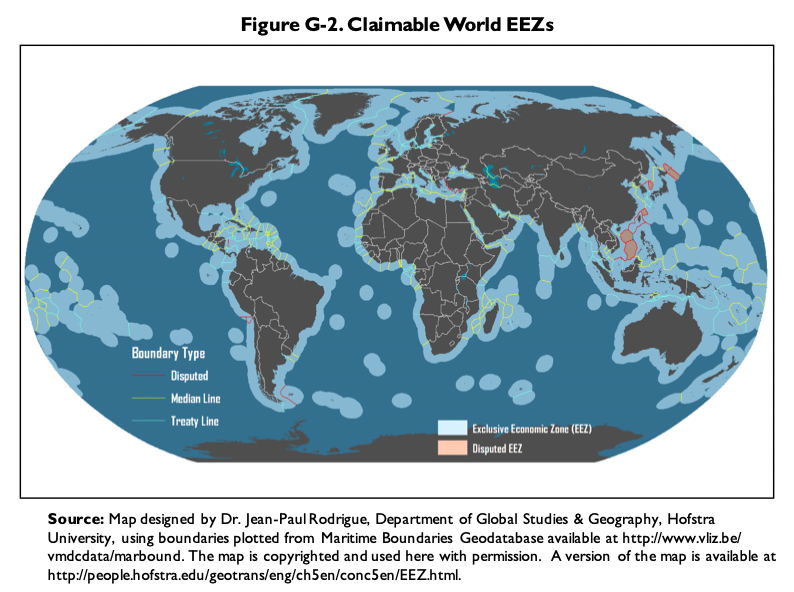

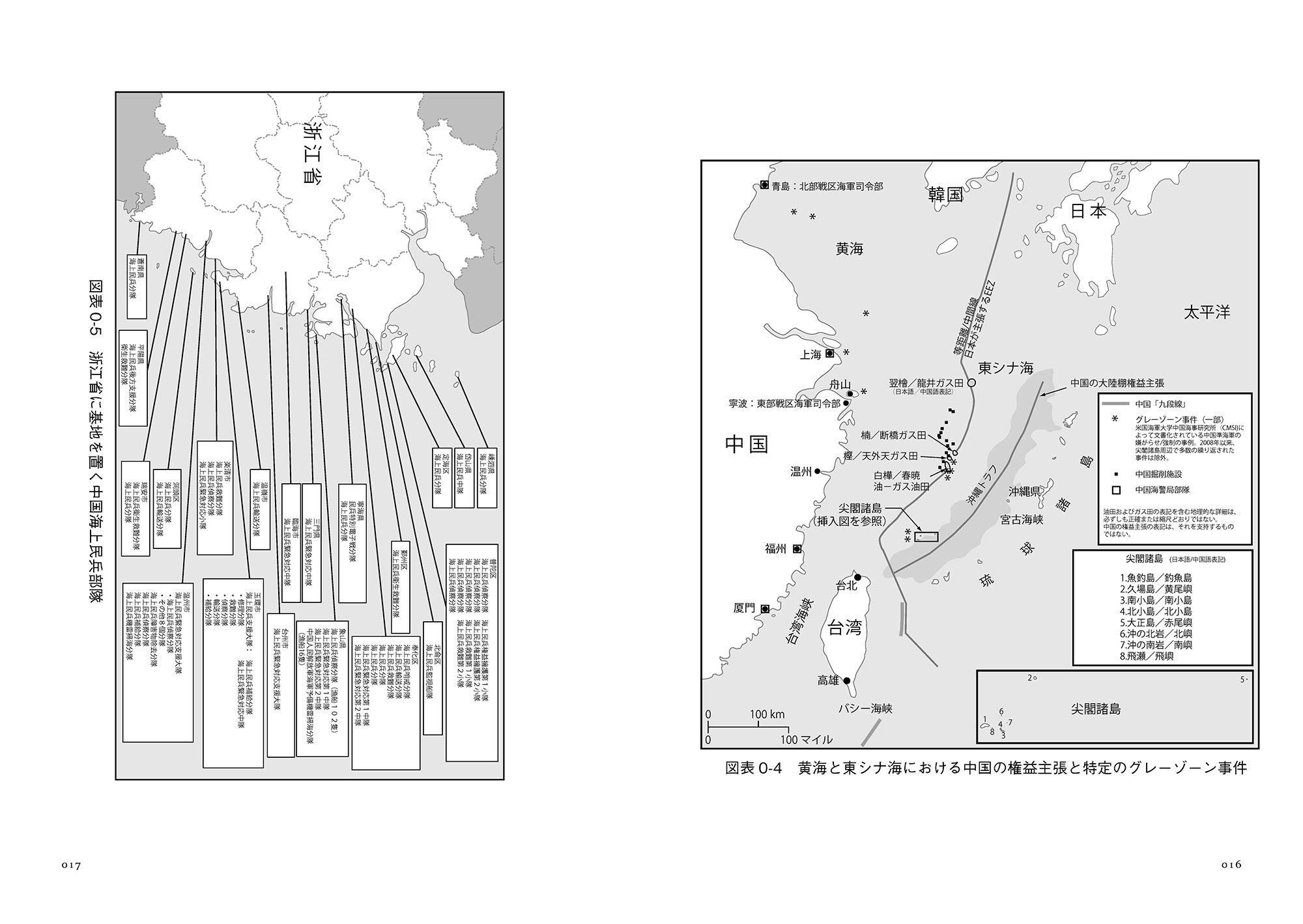

Rather than operating on exterior lines like such geographically advantaged sea powers as the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Australia, China must radiate sea power from interior lines in a way that prioritizes increasing control over its disputed sovereignty claims in the “Near Seas” (the Yellow, East, and South China Seas) while seeking growing influence across the Indo-Pacific region and nascent global presence. To pursue these radiating ripples of maritime interests and activities, Beijing draws on three sea forces, each the maritime component of one of its three armed forces: the (1) People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), (2) China Coast Guard (CCG), and (3) People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). Each PRC sea force has the world’s most ships in its category. The PLAN also includes the world’s most numerous conventional submarine force. This volume tracks all three PRC sea forces in unrivaled detail.

The PRC military has the world’s largest fleet of space event support ships and oceanographic research vessels at its call, as well as global port infrastructure networks and logistics support and emerging overseas facilities. On the civilian side, PRC sea power is supplemented by the world’s largest fishing fleet, number of fishers, aquaculture and pisciculture industries, merchant marine, and marine sector overall, as well as a large nationally flagged tanker fleet. In 2023, China achieved the world’s largest commercial fleet in terms of gross tonnage in shipping capacity.

PRC ship numbers matter. First, China increasingly enjoys both quantity and quality at sea. In recent years China has transcended Cold War shipbuilding that produced crude Soviet-style, post-World War II ship designs. The PLAN, naturally China’s most advanced sea force technologically, has most dramatically replaced backward rust buckets with increasing numbers of sophisticated platforms. But the CCG and PAFMM are also modernizing significantly. Of China’s three sea forces, its coast guard has grown the most rapidly in numbers and enjoys the greatest global numerical superiority.

China’s shipbuilding juggernaut, powered by what until very recently was indisputably the world’s largest population and fastest-growing multi-trillion-dollar economy, has sustained rapid modernization of all three sea forces even as numbers of modern vessels grow substantially. Beijing’s sea forces are supported by the world’s largest shipyard infrastructure, which has achieved the largest, fastest production-capacity expansion since World War II. This is part of the largest postwar military buildup, for which Beijing leverages the world’s largest human-organizational technology acquisition and application infrastructure. China’s commercial shipbuilding juggernaut subsidizes overhead costs for construction of all three sea forces’ vessels, an impossibility for America’s military-focused shipbuilding industry. CCG construction is particularly economical and efficient: commercial off-the-shelf drivetrains and electronics, together with a lack of complex combat systems and weapons, facilitate rapid assembly with multiple units constructed simultaneously. PAFMM vessel building is even easier and cheaper.

Numbers matter for maintaining presence and influence in vital seas. Even the most advanced ship cannot be in more than one place at a time. This is particularly true regarding the growing Sino-American strategic competition where the United States is playing an away game. U.S. Coast Guard cutters are primarily focused near American waters, far from any international disputes, while the U.S. Navy is dispersed around the world. Meanwhile, all three major PRC sea forces remain focused first and foremost on the contested Near Seas and their immediate approaches, close to China’s homeland bases, and supported by “anti-navy” land-based air and missile coverage and short, interior supply lines. In those three proximate seas, Beijing has the world’s most numerous and extensive disputed island and feature claims, with the largest number of other parties; none looms larger than Taiwan. At approximately 4.7 million sq. km in area, the Near Seas are roughly half the size of mainland China and equivalent to the areas of the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean, and North Sea combined. Within this maritime area China regularly deploys sea forces far greater numerically than the size of the entire U.S. Navy.

For all these reasons, a full accounting of China’s navy, coast guard, and maritime militia has long been needed. This pioneering volume has filled that vital void by offering the most comprehensive unclassified, open-source PRC sea forces order of battle, data, and ship drawings available anywhere. Even casually perusing its pages reveals the staggering scope and extent of Beijing’s sea power today. This second edition includes new sections for PLA Army and Air Force watercraft; the latest data updates, particularly concerning nuclear-powered submarines; and a variety of new illustrations. I commend it to everyone seeking to understand how China is making such great waves on the world’s oceans, and what course it may take in coming years.

Andrew S. Erickson

China Maritime Studies Institute

Newport, Rhode Island

Modern Chinese Maritime Forces, second edition is a naval reference book by Manfred Meyer, a noted artist and illustrator. It provides up-to-the minute information on Chinese sea power. It lists all vessels in service of the Chinese government. – not just the People’s Liberation Army Navy, but the Coast Guard, China Maritime Surveillance, China Fisheries Law Enforcement Command, the Maritime Militia, and many other state-controlled agencies that carry out China’s policy at sea. This second edition add new sections covering the ships and boats used by the PLA Ground Forces and PLA Air Force. It has grown by almost 40 pages since the first edition was published in 2018.

Over 650 drawings show everything from aircraft carriers to buoy tenders, accompanied by detailed information on their characteristics. Supporting material covers fleet assignments and descriptions of the Chinese systems for hull numbers and equipment designations.

Modern Chinese Maritime Forces has the most complete unclassified information on Chinese state-owned vessels available anywhere. Noted China specialist Dr. Andrew Erickson, in the Foreword, writes “Today, China’s maritime forces have the most ships of any nation. This pathbreaking book documents their force structure in unprecedented detail.”

Modern Chinese Maritime Forces is available as either a searchable .pdf or a softcover 174-page book. Both can be bought as a bundle for a reduced price.

Because Mr. Meyer is continuing to support the book with new drawings and information, we update the .pdf quarterly. Anyone who purchases the latest edition .pdf version (now the Second Edition) automatically receives the updated version, at no charge, via the Wargame Vault. This feature of the Wargame Vault’s service ensures that your .pdf version of Modern Chinese Maritime Forces will never be more than three months out of date.

REVIEWS

“This is a phenomenally thorough project, and I suspect it is both more complete and up to date than anything available to our armed forces at a classified or unclassified level. Herr Meyer’s meticulous research and superb drawing skills have produced a reference resource of unparalleled usefulness for anyone needing a handy reference for China’s vast naval and paranaval forces.”

– A.D. Baker III, former editor of Combat Fleets of the World

“I think it is for the first time that such a nearly complete overview of the Chinese maritime services has been made available to the public. The Chinese navy has risen in twenty years from a regional outdated navy to one of the global players which cannot be overlooked by the other world and regional powers.”

– Werner Globke, editor of Weyer’s Warships

“This is a badly-needed book: an accessible, compact guide to the ships of the Chinese navy and its related paramilitary services. All of the ships are shown in very clear scaled drawings, which give a good sense of size and configuration. No other guide of this type exists. That makes this quite possibly the only good reference to the Chinese fleets. No one concerned with current naval affairs can afford to miss it.”

– Dr. Norman Friedman, technical naval author

“I devoured this book. This is perhaps the most important and most comprehensive technical naval analysis book to appear in a generation. With the advent of Cold War II and the announced return to great power competition between the United States and the People’s Republic of China, this book should be on the bookshelf of every serious U.S. Navy officer and naval analyst. It will be the standard reference.”

– Captain Jerry Hendrix, USN (ret.), Center for a New American Security

If you have trouble accessing the website above, please download a cached copy here.

You can also click here to access the report via the public CRS website.

KEY EXCERPTS:

p. 9

… …

p. 10

“Salami-Slicing” Strategy and Gray Zone Operations

Observers frequently characterize China’s approach to the SCS and ECS as a “salami-slicing” strategy that employs a series of incremental actions, none of which by itself is a casus belli, to gradually change the status quo in China’s favor.31 Other observers have referred to China’s approach as a strategy of gray zone operations (i.e., operations that reside in a gray zone between peace and war),32 incrementalism,33 creeping annexation,34 working to gain ownership through adverse possession,35 or creeping invasion,36 or as a “talk and take” strategy, meaning a strategy in which China engages in (or draws out) negotiations while taking actions to gain control of contested areas.37 An April 10, 2021, press report, for example, states

China is trying to wear down its neighbors with relentless pressure tactics designed to push its territorial claims, employing military aircraft, militia boats and sand dredgers to dominate access to disputed areas, U.S. government officials and regional experts say.

The confrontations fall short of outright military action without shots being fired, but Beijing’s aggressive moves are gradually altering the status quo, laying the foundation for China to potentially exert control over contested territory across vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean, the officials and experts say….

The Chinese are “trying to grind them down,” said a senior U.S. Defense official….

“Beijing never really presents you with a clear deadline with a reason to use force. You just find yourselves worn down and slowly pushed back,” [Gregory Poling of the Center for Strategic and International Studies] said.38

***

31 See, for example, Julian Ryall, “As Regional Tensions Rise, China Probing Neighbors’ Defense,” Deutsche Welle (DW), October 13, 2022. Another press report refers to the process as “akin to peeling an onion, slowly and deliberately pulling back layers to reach a goal at the center.” (Brad Lendon, “China Is Relentlessly Trying to Peel away Japan’s Resolve on Disputed Islands,” CNN, July 8, 2022.)

32 See, for example, Masaaki Yatsuzuka, “How China’s Maritime Militia Takes Advantage of the Grey Zone,” Strategist, January 16, 2023.

33 See, for example, Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang, “China’s Art of Strategic Incrementalism in the South China Sea,” National Interest, August 8, 2020.

34 See, for example, Alan Dupont, “China’s Maritime Power Trip,” The Australian, May 24, 2014.

35 See Ian Ralby, “China’s Maritime Strategy: To Own the Oceans by Adverse Possession,” The Hill, March 28, 2023.

36 Jackson Diehl, “China’s ‘Creeping Invasion,” Washington Post, September 14, 2014.

37 The strategy has been called “talk and take” or “take and talk.” See, for example, Anders Corr, “China’s Take-And-Talk Strategy In The South China Sea,” Forbes, March 29, 2017. See also Namrata Goswami, “Can China Be Taken Seriously on its ‘Word’ to Negotiate Disputed Territory?” The Diplomat, August 18, 2017.

38 Dan De Luce, “China Tries to Wear Down Its Neighbors with Pressure Tactics,” NBC News, April 10, 2021. See also Dan Altman, “The Future of Conquest, Fights Over Small Places Could Spark the Next Big War,” Foreign Affairs, September 24, 2021.

[CONTINUED…]

p. 11

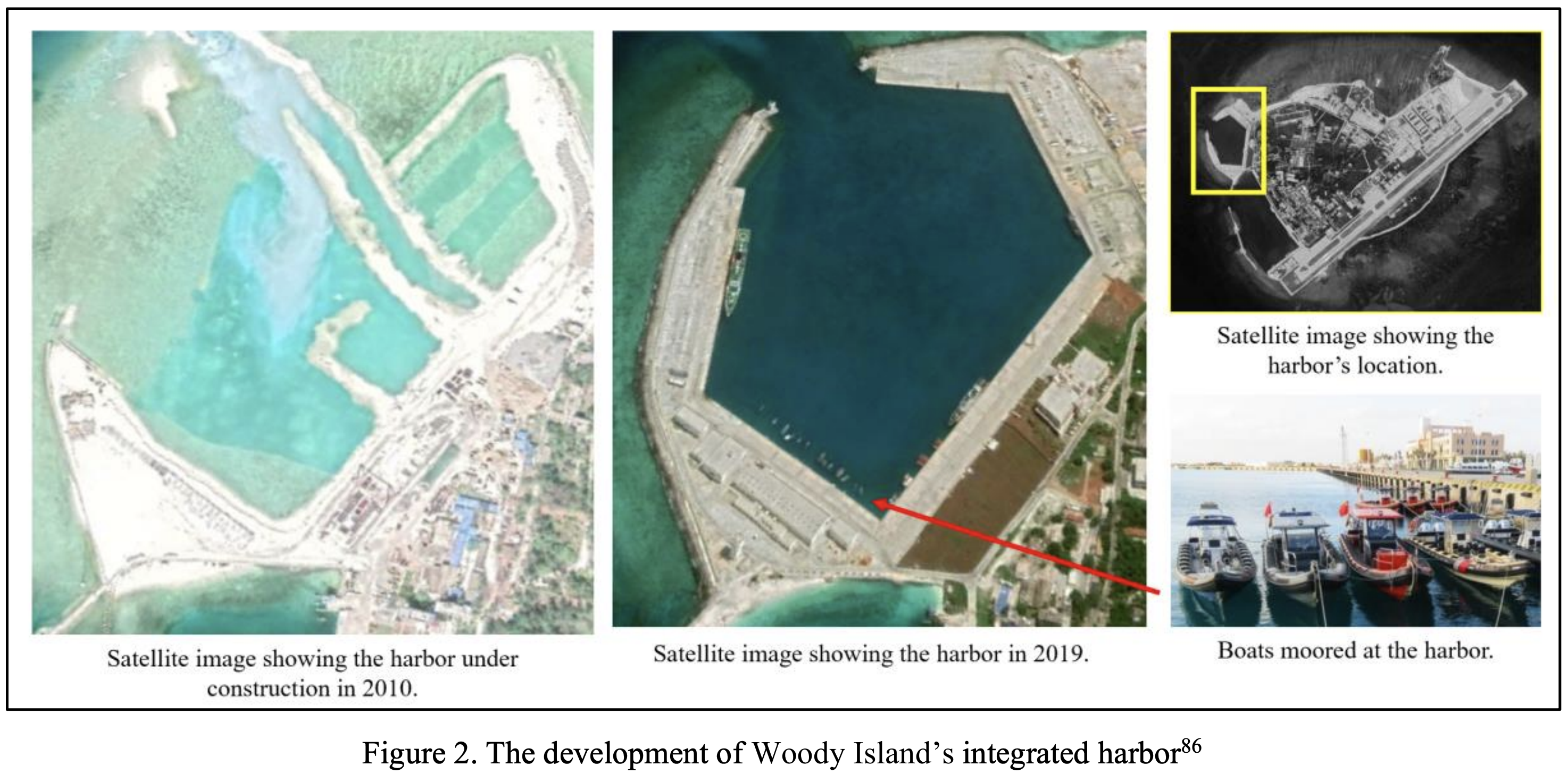

Island Building and Base Construction

Perhaps more than any other set of actions, China’s island-building (aka land-reclamation) and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Paracel Islands and Spratly Islands in the SCS have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is rapidly gaining effective control of the SCS. China’s large-scale island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS appear to have begun around December 2013, and were publicly reported starting in May 2014. Awareness of, and concern about, the activities appears to have increased substantially following the posting of a February 2015 article showing a series of “before and after” satellite photographs of islands and reefs being changed by the work.39

China occupies seven sites in the Spratly Islands. It has engaged in island-building and facilities-construction activities at most or all of these sites, and particularly at three of them—Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, and Mischief Reef, all of which now feature lengthy airfields as well as substantial numbers of buildings and other structures.

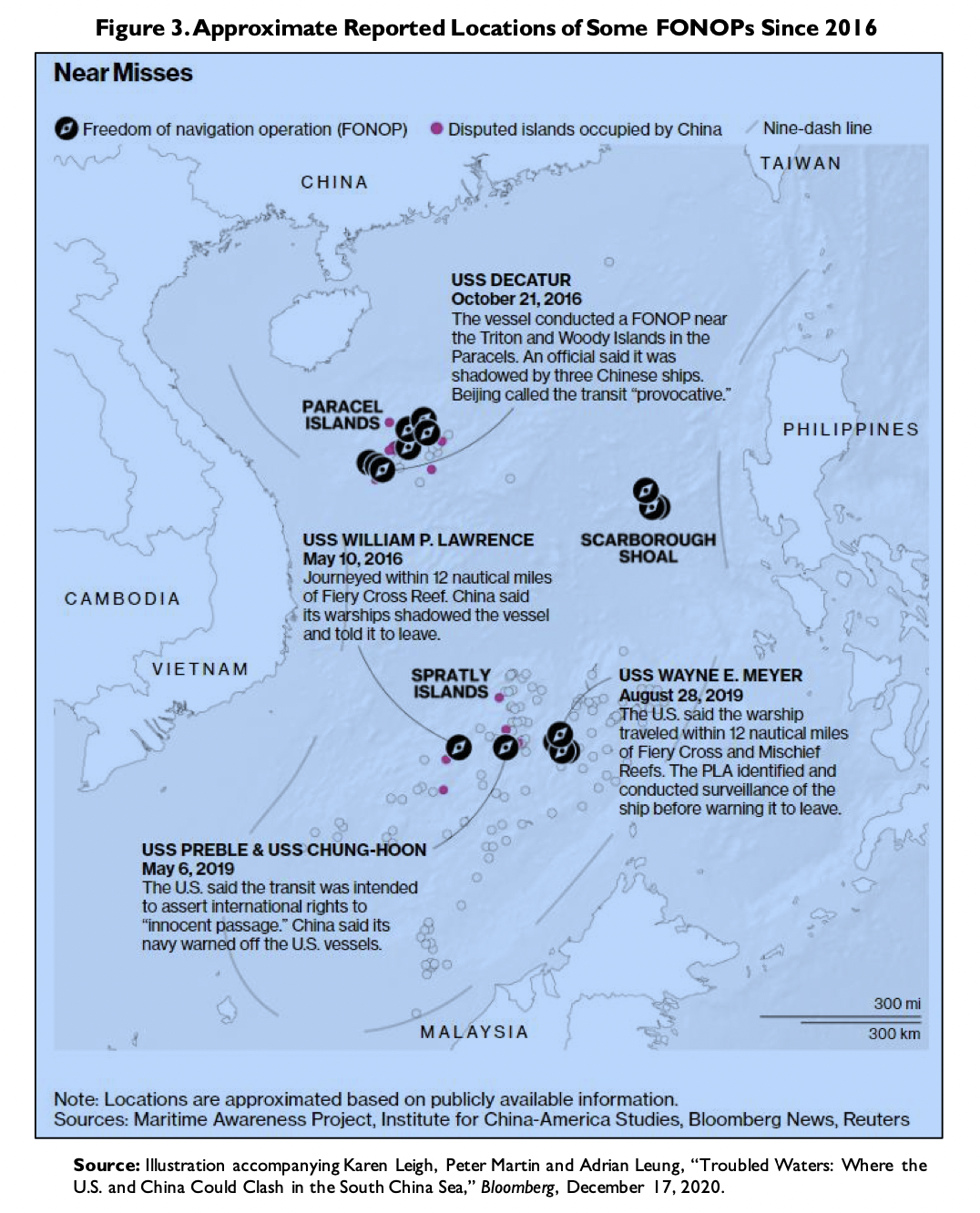

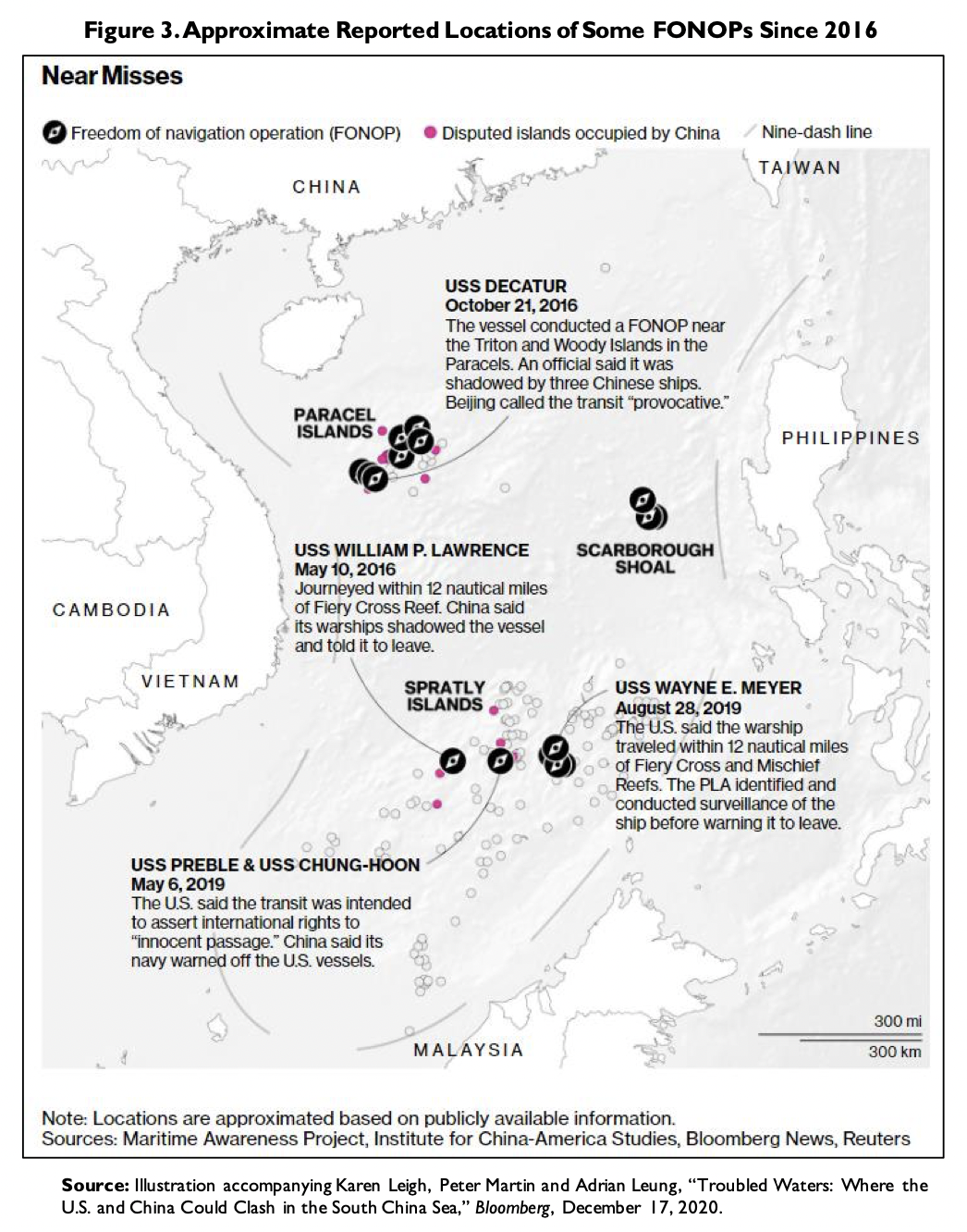

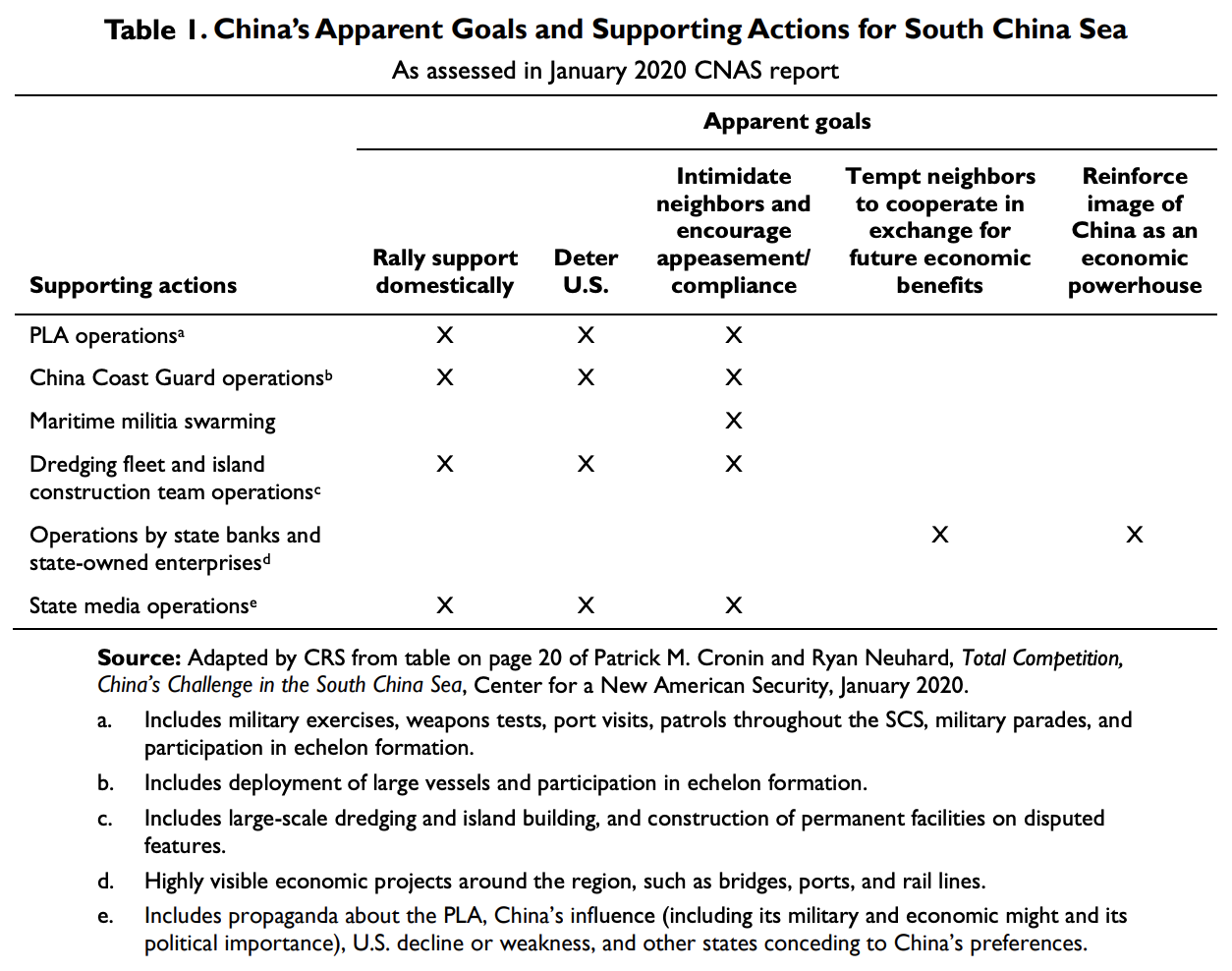

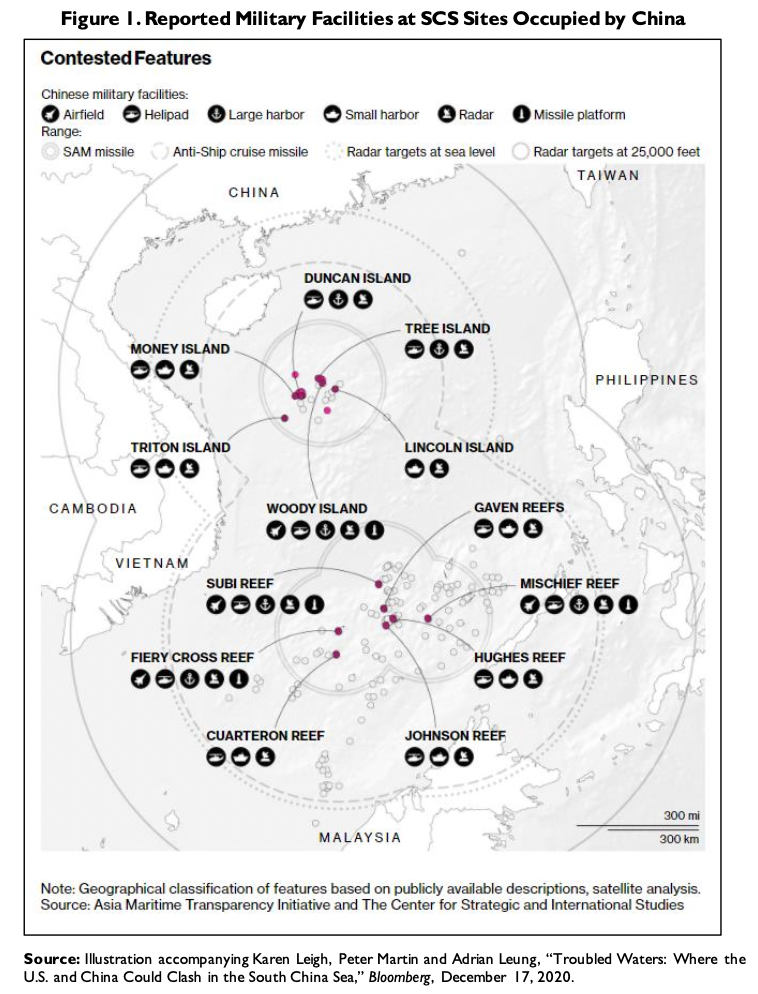

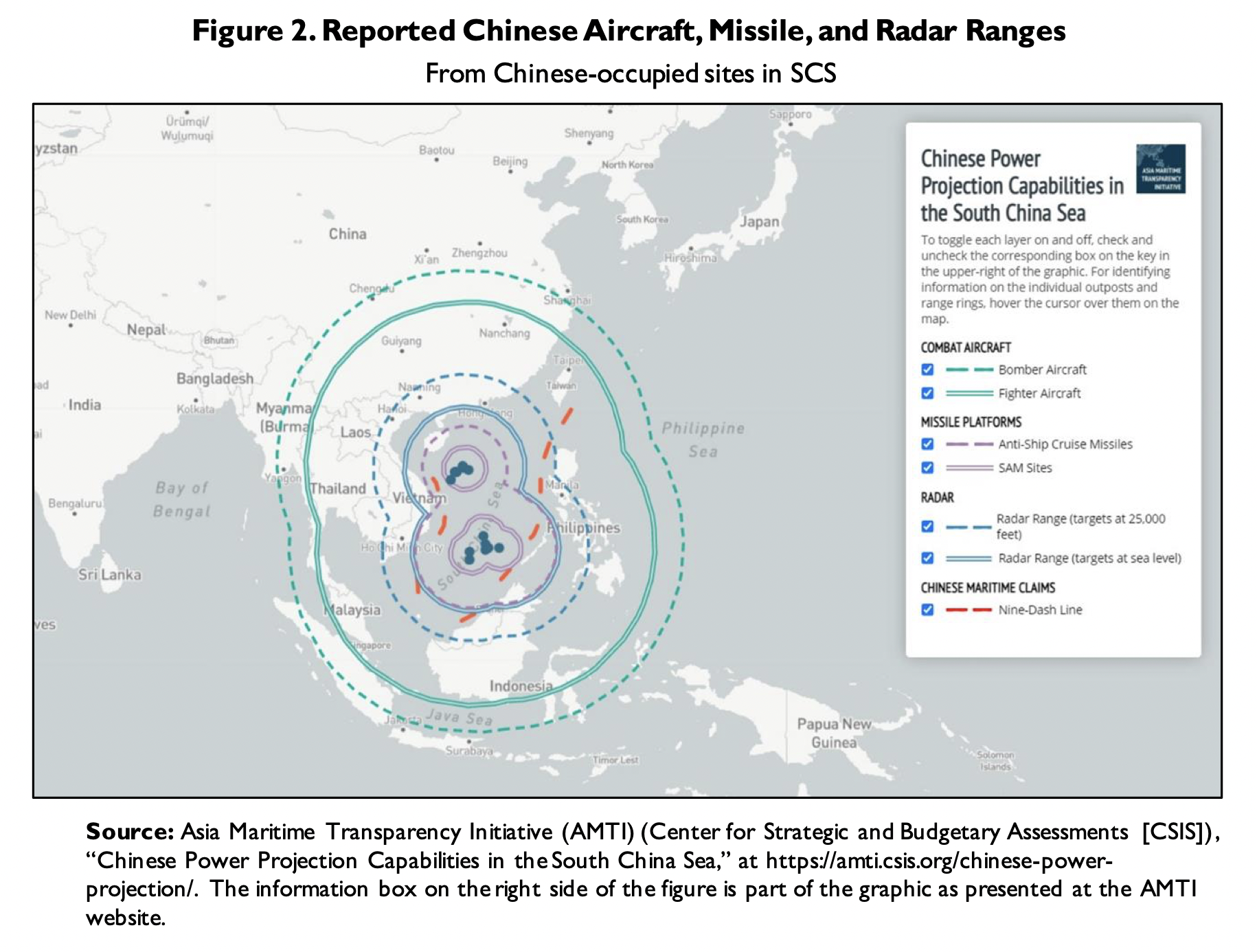

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show reported military facilities at sites that China occupies in the SCS, and reported aircraft, missile, and radar “range rings” extending from those sites. Although other countries, such as Vietnam, have engaged in their own island-building and facilities-construction activities at sites that they occupy in the SCS, these efforts are dwarfed in size by China’s island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS.40

New Maritime Law That Went Into Effect on September 1, 2021

A new Chinese maritime law that China approved in April 2021 as an amendment to its 1983 maritime traffic safety law went into effect September 1, 2021. The law seeks to impose new notification and other requirements on foreign ships entering what China describes as “sea areas under the jurisdiction” of China.41 Some observers have stated that the new law could lead to increased tensions in the SCS, particularly if China takes actions to enforce its provisions.42

***

39 Mira Rapp-Hooper, “Before and After: The South China Sea Transformed,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), February 18, 2015.

40 See, for example, “Vietnam’s Island Building: Double-Standard or Drop in the Bucket?,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), May 11, 2016. For additional details on China’s island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS, see, in addition to Appendix E, CRS Report R44072, Chinese Land Reclamation in the South China Sea: Implications and Policy Options, by Ben Dolven et al.

41 See, for example, Amber Wang, “South China Sea: China Demands Foreign Vessels Report before Entering ‘Its Territorial Waters,’” South China Morning Post, August 30, 2021.

42 See, for example, Navmi Krishna, “Explained: Why China’s New Maritime Law May Spike Tensions in South China Sea,” Indian Express, September 7, 2021; Brad Lendon and Steve George, “The Long Arm of China’s New Maritime Law Risks Causing Conflict with US and Japan,” CNN, September 3, 2021; Richard Javad Heydarian, “China’s Foreign Ship Law Stokes South China Sea Tensions,” Asia Times, September 2, 2021. See also James Holmes, “Are China And Russia Trying To Attack The Law Of The Sea?” 19FortyFive, August 31, 2021.

p. 12

p. 13

… …

p. 15

USE OF COAST GUARD SHIPS AND MARITIME MILITIA ………………………………………………………………………………………. 15

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

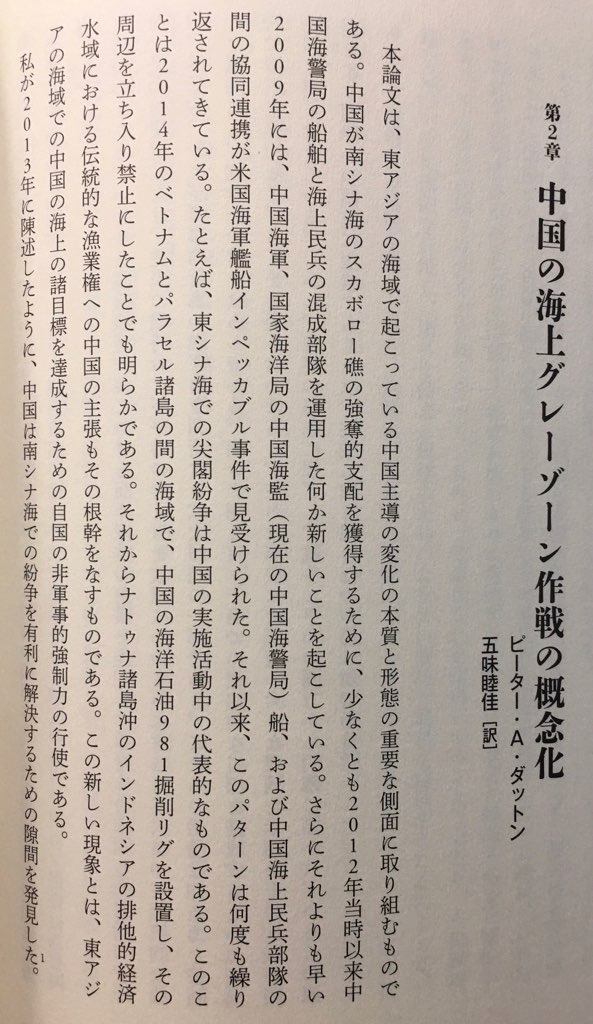

China asserts and defends its maritime claims not only with its navy, but also with its coast guard and its maritime militia. Indeed, China employs its maritime militia and its coast guard more regularly and extensively than its navy in its maritime sovereignty-assertion operations.

p. 88

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia Coast Guard Ships Overview

The China Coast Guard (CCG) is much larger than the coast guard of any other country in the region,224 and it has increased substantially in size through the addition of many newly built ships. China makes regular use of CCG ships to assert and defend its maritime claims, particularly in the ECS, with Chinese navy ships sometimes available over the horizon as backup forces. DOD states that

The CCG is subordinate to the PAP [People’s Armed Police] and is responsible for a wide range of maritime security missions, including defending the PRC’s sovereignty claims; fisheries enforcement; combating smuggling, terrorism, and environmental crimes; as well as supporting international cooperation. In 2021, the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress passed the Coast Guard Law which took effect on 1 February 2021. The legislation regulates the duties of the CCG, to include the use of force, and applies those duties to seas under the jurisdiction of the PRC. The law was meet with concern by other regional countries that may perceive the law as an implicit threat to use force, especially as territorial disputes in the region continue.

The CCG’s rapid expansion and modernization has made it the largest maritime law enforcement fleet in the world. Its newer vessels are larger and more capable than [its] older vessels, allowing them to operate further off shore and remain on station longer. A 2019 academic study published by the U.S. Naval War College estimates the CCG has over 140 regional and oceangoing patrol vessels (or more than 1,000 tons displacement). Some of the vessels are former PLAN [PLA Navy] vessels, such as corvettes, transferred to the CCG and modified CCG operations. The newer, larger vessels are equipped with helicopter facilities, high-capacity water cannons, interceptor boats, and guns ranging from 20 to 76 millimeters. In addition, the same academic study indicates the CCG operates more than 120 regional patrol combatants (500 to 999 tons), which can be used for limited offshore operations, and an additional 450 coast patrol craft (100 to 499 tons).225

In March 2018, China announced that control of the CCG would be transferred from the civilian State Oceanic Administration to the Central Military Commission.226 The transfer occurred on July 1, 2018.227

A January 30, 2023, blog post stated

***

224 See, for example, Damien Cave, “China Creates a Coast Guard Like No Other, Seeking Supremacy in Asian Seas,” New York Times, June 12 (updated September 24), 2023. For a comparison of the CCG to other coast guards in the region in terms of cumulative fleet tonnage in 2010 and 2016, see the graphic entitled “Total Coast Guard Tonnage of Selected Countries” in China Power Team, “Are Maritime Law Enforcement Forces Destabilizing Asia?” China Power (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), updated August 26, 2020, accessed May 31, 2023, at https://chinapower.csis.org/maritime-forces-destabilizing-asia/.

225 Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress [on] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022, p. 78.

226 See, for example, David Tweed, “China’s Military Handed Control of the Country’s Coast Guard,” Bloomberg, March 26, 2018.

227 See, for example, Global Times, “China’s Military to Lead Coast Guard to Better Defend Sovereignty,” People’s Daily Online, June 25, 2018. See also Economist, “A New Law Would Unshackle China’s Coastguard, Far from Its Coast,” Economist, December 5, 2020; Katsuya Yamamoto, “The China Coast Guard as a Part of the China Communist Party’s Armed Forces,” Sasakawa Peace Foundation, December 10, 2020.

p. 89

China’s coast guard presence in the South China Sea is more robust than ever. An analysis of automatic identification system (AIS) [i.e., ship transponder] data from commercial provider MarineTraffic shows that the China Coast Guard (CCG) maintained near-daily patrols at key features across the South China Sea in 2022. Together with the ubiquitous presence of its maritime militia, China’s constant coast guard patrols show Beijing’s determination to assert control over the vast maritime zone within its claimed nine-dash line….

AMTI analyzed AIS data from the year 2022 across the five features most frequented by Chinese patrols: Second Thomas Shoal, Luconia Shoals, Scarborough Shoal, Vanguard Bank, and Thitu Island. Comparison with data from 2020 shows that the number of calendar days that a CCG vessel patrolled near these features increased across the board….

The incomplete nature of AIS data means that these numbers are likely even higher. Some CCG vessels are not observable on commercial AIS platforms, either because their AIS transceivers are disabled or are not detectable by satellite AIS receivers. In other cases, CCG vessels have been observed broadcasting incomplete or erroneous AIS information….

The behavior of CCG vessels observed on patrol in 2022 was similar to that of years past. But AIS data tells only part of the story of the CCG’s influence in the Spratly Islands and its friction with Southeast Asian law enforcement, which took new forms in 2022. Oil and gas standoffs, a recurring feature of the last three years prior, were not as prominent in 2022, likely due to the success of the previous CCG harassment….

As Southeast Asian claimants continue to operate in the Spratly Islands in 2023, the constant presence of China’s coast guard and maritime militia makes future confrontations all but inevitable.228

Law Passed by China on January 22, 2021

A January 22, 2021, press report stated

China passed a law on Friday [January 22] that for the first time explicitly allows its coast guard to fire on foreign vessels, a move that could make the contested waters around China more choppy.…

China’s top legislative body, the National People’s Congress standing committee, passed the Coast Guard Law on Friday, according to state media reports.

According to draft wording in the bill published earlier, the coast guard is allowed to use “all necessary means” to stop or prevent threats from foreign vessels.

The bill specifies the circumstances under which different kind of weapons—hand-held, ship borne or airborne—can be used.

The bill allows coast guard personnel to demolish other countries’ structures built on Chinese-claimed reefs and to board and inspect foreign vessels in waters claimed by China.

The bill also empowers the coastguard to create temporary exclusion zones “as needed” to stop other vessels and personnel from entering.

Responding to concerns, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said on Friday that the law is in line with international practices.229

***

228 “Flooding the Zone: China Coast Guard Patrols in 2022,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), January 30, 2023. See also Damien Cave, “China Creates a Coast Guard Like No Other, Seeking Supremacy in Asian Seas,” New York Times, June 12 (updated June 13), 2023.

229 Yew Lun Tian, “China Authorises Coast Guard to Fire on Foreign Vessels if Needed,” Reuters, January 22, 2021. See also Wataru Okada, “China’s Coast Guard Law Challenges Rule-Based Order,” Diplomat, May 28, 2021; Nguyen

(continued…)

p. 90

On February 19, 2021, the State Department stated that

the United States joins the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan, and other countries in expressing concern with China’s recently enacted Coast Guard law, which may escalate ongoing territorial and maritime disputes.

We are specifically concerned by language in the law that expressly ties the potential use of force, including armed force by the China Coast Guard, to the enforcement of China’s claims in ongoing territorial and maritime disputes in the East and South China Seas.

Language in that law, including text allowing the coast guard to destroy other countries’ economic structures and to use force in defending China’s maritime claims in disputed areas, strongly implies this law could be used to intimidate the PRC’s maritime neighbors.

We remind the PRC and all whose force operates—whose forces operate in the South China Sea that responsible maritime forces act with professionalism and restraint in the exercise of their authorities.

We are further concerned that China may invoke this new law to assert its unlawful maritime claims in the South China Sea, which were thoroughly repudiated by the 2016 Arbitral Tribal[1] ruling. In this regard, the United States reaffirms its statement of July 13th, 2020 regarding maritime claims in the South China Sea.

The United States reminds China of its obligations under the United Nations Charter to refrain from the threat or use of force, and to conform its maritime claims to the International Law of the Sea, as reflected in the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention. We stand firm in our respective alliance commitments to Japan and the Philippines.230

***

Thanh Trung, “How China’s Coast Guard Law Has Changed the Regional Security Structure,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), April 12, 2021; Kawashima Shin, “China’s Worrying New Coast Guard Law, Japan Is Watching the Senkaku Islands Closely,” Diplomat, March 17, 2021;Editorial Board, “China’s New Coast Guard Law Appears Designed to Intimidate,” Japan Times, March 4, 2021; Ryan D. Martinson, “The Real Risks of China’s New Coastguard Law, The Use-of-Force Provisions Are Just the Beginning,” National Interest, March 3, 2021; Sumathy Permal, “Beijing Bolsters the Role of the China Coast Guard,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), March 1, 2021; Katsuya Yamamoto, “Concerns about the China Coast Guard Law—the CCG and the People’s Armed Police,” Sasakawa Peace Foundation, February 25, 2021; Asahi Shimbun, “New Chinese Law Raises Pressure on Japan around Senkaku Islands,” Asahi Shimbun, February 24, 2021; Ryan D. Martinson, “Gauging the Real Risks of China’s New Coastguard Law,” Strategist, February 23, 2021; Eli Huang, “New Law Expands Chinese Coastguard’s Jurisdiction to at Least the First Island Chain,” Strategist, February 16, 2021; Shigeki Sakamoto, “China’s New Coast Guard Law and Implications for Maritime Security in the East and South China Seas,” Lawfare, February 16, 2021; Expert Voices, “Voices: The Chinese Maritime Police Law,” Maritime Awareness Project, February 11, 2021 (includes portions with subsequent dates); Seth Robson, “China Gets More Aggressive with Its Sea Territory Claims as World Battles Coronavirus,” Stars and Stripes, February 1, 2021; Shuxian Luo, “China’s Coast Guard Law: Destabilizing or Reassuring?” Diplomat, January 29, 2021; Shigeki Sakamoto, “China’s New Coast Guard Law and Implications for Maritime Security in the East and South China Seas,” Lawfare, February 16, 2021; Michael Shoebridge, “Xi Licenses Chinese Coastguard to be ‘Wolf Warriors’ at Sea,” Strategist, February 15, 2021; “New Law Institutionalises Chinese Maritime Coercion,” Oxford Analytica Daily Brief, February 15, 2021.

230 U.S. Department of State, “Department Press Briefing—February 19, 2021,” Ned Price, Department Spokesperson, Washington, DC, February 19, 2021. During the question-and-answer portion of the briefing, the following exchange occurred:

QUESTION: I have two quick questions about the Chinese coast guard law. Have you raised concern directly with Beijing? And secondly, has the U.S. seen any examples of concerning behavior since the law was passed in either the South China Sea or the East China Sea?

MR PRICE: For that, I think, Demetri, we would want to—we might want to refer you to DOD for instances of concerning behavior—for concerning behavior there. When it comes to the coast guard law, of course, we have been in close contact with our allies and partners, and we mentioned a few of them in this context: the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan, and other countries that face the

(continued…)

p. 91

Maritime Militia

On March 16, 2021, following a U.S.-Japan “2+2” ministerial meeting that day in Tokyo between Secretary of State Blinken, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi, and Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi, the U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee released a U.S.-Japan joint statement for the press that stated in part that the minister “expressed serious concerns about recent disruptive developments in the region, such as the China Coast Guard law.231

China also uses its maritime militia—also referred to as the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM)—to defend its maritime claims. The PAFMM essentially consists of fishing-type vessels with armed crew members. In the view of some observers, the PAFMM—even more than China’s navy or coast guard—is the leading component of China’s maritime forces for asserting its maritime claims, particularly in the SCS. U.S. analysts have paid increasing attention to the role of the PAFMM as a key tool for implementing China’s salami-slicing strategy, and have urged U.S. policymakers to focus on the capabilities and actions of the PAFMM.232 DOD states the following about the PAFMM:

***

type of unacceptable PRC pressure in the South China Sea. I wouldn’t want to characterize any conversations with Beijing on this. Of course, we have emphasized that, especially at the outset of this administration, our—the first and foremost on our agenda is that coordination among our partners and allies, and we have certainly been engaged deeply in that.

See also Demetri Sevastopulo, Kathrin Hille, and Robin Harding, “US Concerned at Chinese Law Allowing Coast Guard Use of Arms,” Financial Times, February 19, 2021; Simon Lewis, Humeyra Pamuk, Daphne Psaledakis, and David Brunnstrom, “U.S. Concerned China’s New Coast Guard Law Could Escalate Maritime Disputes,” Reuters, February 19, 2021.

231 Department of State, “U.S.-Japan Joint Press Statement,” Media Note, Office of the Spokesperson, March 16, 2021. See also Ralph Jennings, “Maritime Law Expected to Give Beijing an Edge in South China Sea Legal Disputes,” VOA, March 15, 2021; Junko Horiuchi, “Japan, U.S. Express ‘Serious Concerns’ over China Coast Guard Law,” Kyodo News, March 16, 2021.

232 For additional discussions of the PAFMM, see, for example, Brad Lendon, “‘Little Blue Men’: Is a Militia Beijing Says Doesn’t Exist Causing Trouble in the South China Sea?” CNN, August 12, 2023; “The Ebb and Flow of Beijing’s South China Sea Militia,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) (Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS]), November 9, 2022; Samuel Cranny-Evans, “Analysis: How China’s Coastguard and Maritime Militia May Create Asymmetry at Sea,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, July 13, 2022; Zachary Haver, “Unmasking China’s Maritime Militia,” BenarNews, May 17, 2021; Ryan D. Martinson, “Xi Likes Big Boats (Coming Soon to a Reef Near You),” War on the Rocks, April 28, 2021; Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson, “Records Expose China’s Maritime Militia at Whitsun Reef, Beijing Claims They Are Fishing Vessels. The Data Shows Otherwise,” Foreign Policy, March 29, 2021; Zachary Haver, “China’s Civilian Fishing Fleets Are Still Weapons of Territorial Control,” Center for Advanced China Research, March 26, 2021; Chung Li-hua and Jake Chung, “Chinese Coast Guard an Auxiliary Navy: Researcher,” Taipei Times, June 29, 2020; Gregory Poling, “China’s Hidden Navy,” Foreign Policy, June 25, 2019; Mike Yeo, “Testing the Waters: China’s Maritime Militia Challenges Foreign Forces at Sea,” Defense News, May 31, 2019; Laura Zhou, “Beijing’s Blurred Lines between Military and Non-Military Shipping in South China Sea Could Raise Risk of Flashpoint,” South China Morning Post, May 5, 2019; Andrew S. Erickson, “Fact Sheet: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM),” April 29, 2019, Andrewerickson.com; Jonathan Manthorpe, “Beijing’s Maritime Militia, the Scourge of South China Sea,” Asia Times, April 27, 2019; Ryan D. Martinson, “Manila’s Images Are Revealing the Secrets of China’s Maritime Militia, Details of the Ships Haunting Disputed Rocks Sshow China’s Plans,” Foreign Policy, April 19, 2021; Brad Lendon, “Beijing Has a Navy It Doesn’t Even Admit Exists, Experts Say. And It’s Swarming Parts of the South China Sea,” CNN, April 13, 2021; Samir Puri and Greg Austin, “What the Whitsun Reef Incident Tells Us About China’s Future Operations at Sea,” International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), April 9, 2021; Drake Long, “Chinese Maritime Militia on the Move in Disputed Spratly Islands,” Radio Free Asia, March 24, 2021; Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Secretive Maritime Militia May Be Gathering at Whitsun Reef, Boats Designed to Overwhelm Civilian Foes Can Be Turned into Shields in Real Conflict,” Foreign Policy, March 22, 2021; Dmitry Filipoff, “Andrew S. Erickson and Ryan D. Martinson Discuss China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), March 11, 2019; Jamie Seidel, “China’s Latest Island Grab:

(continued…)

p. 92

Background & Missions. The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) is a subset of China’s national militia, an armed reserve force of civilians available for mobilization that is ultimately subordinate to the Central Military Commission through the National Defense Mobilization Department. Throughout China, militia units organize around towns, villages, urban sub-districts, and enterprises, and vary widely in composition and mission.